Effect of Selected Factors on the Prediction Accuracy of Plant-Available Phosphorus and Potassium: A Global Meta-Analysis for Infrared Spectroscopy Protocol

Abstract

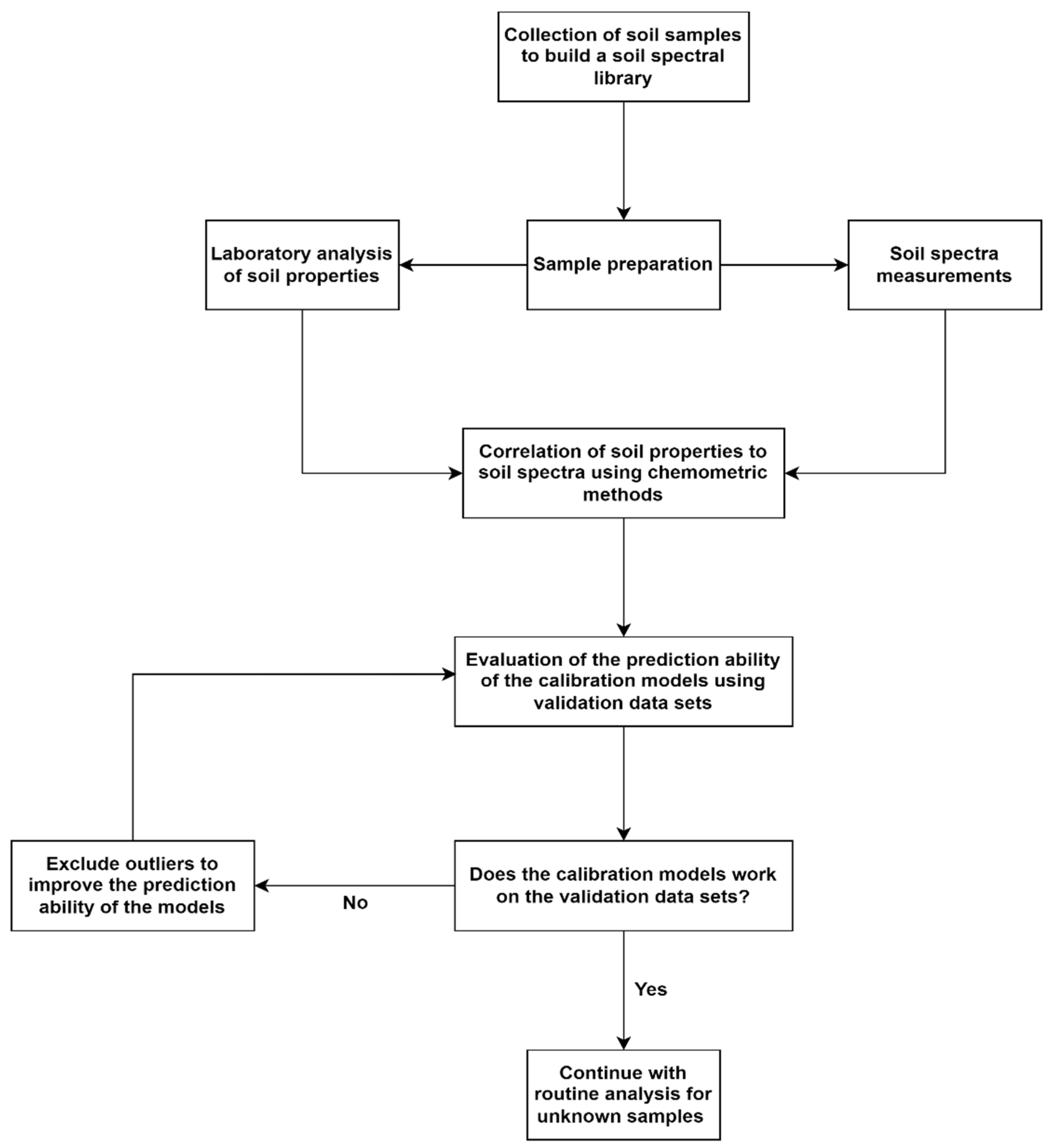

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Meta-Analysis

2.2. Literature Search Strategy

- Infrared spectroscopy and soil nutrients;

- Spectroscopy and soil fertility;

- Prediction of soil properties;

- Visible near-infrared, near-infrared, mid-infrared and soil P and K;

- Calibration models and prediction of soil properties.

2.3. Selection Criteria

- Used infrared spectroscopy to predict soil properties in the laboratory;

- Reported reference chemical methods and soil analysis results;

- Reported validation prediction statistics (r2, RMSE, and RDP);

- Predicted plant-available phosphorus and potassium;

- Provided soil sample sizes;

- Conducted experimental research.

2.4. Data Extraction

- Author names, year of publication, place of research (country);

- Treatment means for P and K measured using chemical methods;

- Soil sample size;

- Validation statistics (r2, RMSE, and RPD) for either P or K;

- Type and name of instruments;

- Chemical methods;

- Infrared regions;

- Regression models.

2.5. Data Sorting

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Meta-Data

3.2. Effect of Soil Sample Size and Concentration on the Prediction Accuracy of P and K

3.2.1. Soil Sample Size

3.2.2. Soil Nutrient Concentration

3.3. Accuracy of the Infrared Spectroscopy Protocol

3.3.1. Phosphorus

3.3.2. Potassium

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| NO. | Year of Publication | Study Reference |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | 2001 | [16] |

| 2. | 2003 | [4] |

| 3. | 2003 | [40] |

| 4. | 2003 | [41] |

| 5. | 2005 | [38] |

| 6. | 2006 | [9] |

| 7. | 2007 | [27] |

| 8. | 2007 | [11] |

| 9. | 2007 | [7] |

| 10. | 2008 | [42] |

| 11. | 2008 | [26] |

| 12. | 2009 | [12] |

| 13. | 2009 | [43] |

| 14. | 2010 | [44] |

| 15. | 2010 | [45] |

| 16. | 2012 | [18] |

| 17. | 2012 | [19] |

| 18. | 2012 | [46] |

| 19. | 2013 | [47] |

| 20. | 2014 | [48] |

| 21. | 2014 | [49] |

| 22. | 2014 | [50] |

| 23. | 2015 | [28] |

| 24. | 2015 | [51] |

| 25. | 2016 | [52] |

| 26. | 2017 | [53] |

| 27. | 2018 | [14] |

| 28. | 2018 | [54] |

| 29. | 2019 | [15] |

| 30. | 2019 | [55] |

| 31. | 2020 | [25] |

| 32. | 2020 | [21] |

| 33. | 2020 | [22] |

| 34. | 2020 | [56] |

| 35. | 2021 | [57] |

| 36. | 2021 | [58] |

| 37. | 2021 | [59] |

| 38. | 2022 | [60] |

| 39. | 2022 | [61] |

| 40. | 2023 | [62] |

| 41. | 2023 | [63] |

| 42. | 2024 | [64] |

| 43. | 2024 | [65] |

| 44. | 2024 | [66] |

| 45. | 2024 | [67] |

References

- Goswami, B.; Pariyar, B.; Pariyar, A. Precision Nutrient Management in Organic Cabbage Cultivation. Ecol. Environ. Conserv. 2025, 31, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, A.L.; Ramphisa-Nghondzweni, P.D.; Van Zijl, G. Development of soil spectroscopy models for the Western Highveld region, South Africa: Why do we need local data? Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2024, 75, e70014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nduwamungu, C.; Ziadi, N.; Parent, L.É.; Tremblay, G.F.; Thuriès, L. Opportunities for, and limitations of, near infrared reflectance spectroscopy applications in soil analysis: A review. Can. J. Soil Sci. 2009, 89, 531–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, K.; Singh, B.; McBratney, A. Simultaneous estimation of several soil properties by ultra-violet, visible, and near-infrared reflectance spectroscopy. Soil Res. 2003, 41, 1101–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, A. Changes in soil organic carbon at regional scales: Strategies to cope with spatial variability. Ph.D. Dissertation, Universite Catholique de Louvain, Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Malley, D.F.; Martin, P.D.; Ben-Dor, E. Application in analysis of soils. Near-Infr. Spec. Agric. 2004, 44, 729–784. [Google Scholar]

- Mouazen, A.M.; Maleki, M.R.; De Baerdemaeker, J.; Ramon, H. On-line measurement of some selected soil properties using a VIS–NIR sensor. Soil Tillage Res. 2007, 93, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hati, K.M.; Sinha, N.K.; Mohanty, M.; Jha, P.; Londhe, S.; Sila, A.; Towett, E.; Chaudhary, R.S.; Jayaraman, S.; Vassanda Coumar, M.; et al. Mid-infrared reflectance spectroscopy for estimation of soil properties of Alfisols from eastern India. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossel, R.V.; Walvoort, D.J.J.; McBratney, A.B.; Janik, L.J.; Skjemstad, J.O. Visible, near infrared, mid infrared or combined diffuse reflectance spectroscopy for simultaneous assessment of various soil properties. Geoderma 2006, 131, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M.; Mylavarapu, R.S.; Bogrekci, I.; Lee, W.S.; Clark, M.W. Reflectance spectroscopy for routine agronomic soil analyses. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2007, 172, 469–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morón, A.; Cozzolino, D. Measurement of phosphorus in soils by near infrared reflectance spectroscopy: Effect of reference method on calibration. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2007, 38, 1965–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minasny, B.; Tranter, G.; McBratney, A.B.; Brough, D.M.; Murphy, B.W. Regional transferability of mid-infrared diffuse reflectance spectroscopic prediction for soil chemical properties. Geoderma 2009, 153, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, B.; Mouazen, A.M. Calibration of visible and near infrared spectroscopy for soil analysis at the field scale on three European farms. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2011, 62, 629–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijewardane, N.K.; Ge, Y.; Wills, S.; Libohova, Z. Predicting physical and chemical properties of US soils with a mid-infrared reflectance spectral library. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2018, 82, 722–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.M.; Vandamme, E.; Senthilkumar, K.; Sila, A.; Shepherd, K.D.; Saito, K. Near-infrared, mid-infrared or combined diffuse reflectance spectroscopy for assessing soil fertility in rice fields in sub-Saharan Africa. Geoderma 2019, 354, 113840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.W.; Laird, D.A.; Mausbach, M.J.; Hurburgh, C.R. Near-infrared reflectance spectroscopy–principal components regression analyses of soil properties. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2001, 65, 480–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarty, G.W.; Reeves, J.B. Comparison of near infrared and mid infrared diffuse reflectance spectroscopy for field-scale measurement of soil fertility parameters. Soil Sci. 2006, 171, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, D.; Tremblay, G.F.; Ziadi, N.; Bélanger, G.; Parent, L.É. Predicting soil phosphorus-related properties using near-infrared reflectance spectroscopy. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2012, 76, 2318–2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinoshita, R.; Moebius-Clune, B.N.; van Es, H.M.; Hively, W.D.; Bilgili, A.V. Strategies for soil quality assessment using visible and near-infrared reflectance spectroscopy in a Western Kenya chronosequence. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2012, 76, 1776–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debaene, G.; Niedźwiecki, J.; Pecio, A.; Żurek, A. Effect of the number of calibration samples on the prediction of several soil properties at the farm-scale. Geoderma 2014, 214, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takele, C.; Iticha, B. Use of infrared spectroscopy and geospatial techniques for measurement and spatial prediction of soil properties. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsakiridis, N.L.; Keramaris, K.D.; Theocharis, J.B.; Zalidis, G.C. Simultaneous prediction of soil properties from VNIR-SWIR spectra using a localized multi-channel 1-D convolutional neural network. Geoderma 2020, 367, 114258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocita, M.; Stevens, A.; van Wesemael, B.; Aitkenhead, M.; Bachmann, M.; Barthès, B.; Ben-Dor, E.; Brown, D.J.; Clairotte, M.; Csorba, A.; et al. Soil spectroscopy: An alternative to wet chemistry for soil monitoring. Adv. Agron. 2015, 132, 139–159. [Google Scholar]

- Iznaga, A.C.; Orozco, M.R.; Alcantara, E.A.; Pairol, M.C.; Sicilia, Y.E.D.; De Baerdemaeker, J.; Saeys, W. Vis/NIR spectroscopic measurement of selected soil fertility parameters of Cuban agricultural Cambisols. Biosyst. Eng. 2014, 125, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reda, R.; Saffaj, T.; Itqiq, S.E.; Bouzida, I.; Saidi, O.; Yaakoubi, K.; Lakssir, B.; El Mernissi, N.; El Hadrami, E.M. Predicting soil phosphorus and studying the effect of texture on the prediction accuracy using machine learning combined with near-infrared spectroscopy. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2020, 242, 118715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zornoza, R.; Guerrero, C.; Mataix-Solera, J.; Scow, K.M.; Arcenegui, V.; Mataix-Beneyto, J. Near infrared spectroscopy for determination of various physical, chemical and biochemical properties in Mediterranean soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2008, 40, 1923–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Huang, M.; García, A.; Hernández, A.; Song, H. Prediction of soil macronutrients content using near-infrared spectroscopy. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2007, 58, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonett, J.P.; Camacho-Tamayo, J.H.; Ramírez-López, L. Mid-infrared spectroscopy for the estimation of some soil properties. Agron. Colomb. 2015, 33, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Q.; Hong, H.; Zhao, L.; Kukolich, S.; Yin, K.; Wang, C. Visible and near-infrared reflectance spectroscopy for investigating soil mineralogy: A review. J. Spectrosc. 2018, 2018, 3168974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Sudduth, K.A.; He, D.; Myers, D.B.; Nathan, M.V. Soil phosphorus and potassium estimation by reflectance spectroscopy. Trans. ASABE 2016, 59, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennard, R.W.; Stone, L.A. Computer aided design of experiments. Technometrics 1969, 11, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Watts, D.B.; Van Santen, E.; Cao, G. Influence of poultry litter on crop productivity under different field conditions: A meta-analysis. Agron. J. 2018, 110, 807–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theophile, T. Infrared spectroscopy: Materials science, engineering and technology. In BoD–Books on Demand; Theophile, T., Ed.; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Paz-Kagan, T.; Shachak, M.; Zaady, E.; Karnieli, A. A spectral soil quality index (SSQI) for characterizing soil function in areas of changed land use. Geoderma 2014, 230, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelby, L.B.; Vaske, J.J. Understanding meta-analysis: A review of the methodological literature. Leis. Sci. 2008, 30, 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, K.D.; Walsh, M.G. Development of reflectance spectral libraries for characterization of soil properties. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2002, 66, 988–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Dor, E.; Irons, J.R.; Epema, G.F. Soil reflectance. Remote Sens. Earth Sci. Man. Remote Sens. 1999, 3, 111–188. [Google Scholar]

- Bogrekci, I.; Lee, W.S. Spectral phosphorus mapping using diffuse reflectance of soils and grass. Biosyst. Eng. 2005, 91, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.S.; Lee, D.H.; Sudduth, K.A.; Chung, S.O.; Kitchen, N.R.; Drummond, S.T. Wavelength identification and diffuse reflectance estimation for surface and profile soil properties. Trans. ASABE 2009, 52, 683–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozzolino, D.; Moron, A. The potential of near-infrared reflectance spectroscopy to analyse soil chemical and physical characteristics. J. Agric. Sci. 2003, 140, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.S.; Sanchez, J.F.; Mylavarapu, R.S.; Choe, J.S. Estimating chemical properties of Florida soils using spectral reflectance. Trans. ASAE 2003, 46, 1443–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossel, R.V.; Jeon, Y.S.; Odeh, I.O.A.; McBratney, A.B. Using a legacy soil sample to develop a mid-IR spectral library. Soil Res. 2008, 46, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janik, L.J.; Forrester, S.T.; Rawson, A. The prediction of soil chemical and physical properties from mid-infrared spectroscopy and combined partial least-squares regression and neural networks (PLS-NN) analysis. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2009, 97, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgili, A.V.; Van Es, H.M.; Akbas, F.; Durak, A.; Hively, W.D. Visible-near infrared reflectance spectroscopy for assessment of soil properties in a semi-arid area of Turkey. J. Arid Environ. 2010, 74, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djuuna, I.A.F.; Abbott, L.; Russell, C. Determination and prediction of some soil properties using partial least square (PLS) calibration and mid-infrared (MIR) spectroscopy analysis. J. Trop. Soils 2013, 16, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudduth, K.A.; Kremer, R.J.; Kitchen, N.R.; Myers, D.B. Estimating soil quality indicators with diffuse reflectance spectroscopy. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Precision Agriculture, Denver, CO, USA, 22–25 July 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, G.; Sudduth, K.A.; Myers, D.B.; He, D.; Nathan, M.V. Factors Affecting Soil Phosphorus and Potassium Estimation by Reflectance Spectroscopy. In Proceedings of the 2013 ASABE Annual International Meeting, Kansas City, MO, USA, 21–24 July 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Vašát, R.; Kodešová, R.; Borůvka, L.; Klement, A.; Jakšík, O.; Gholizadeh, A. Consideration of peak parameters derived from continuum-removed spectra to predict extractable nutrients in soils with visible and near-infrared diffuse reflectance spectroscopy (VNIR-DRS). Geoderma 2014, 232, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenjun, J.; Zhou, S.; Jingyi, H.; Shuo, L. In situ measurement of some soil properties in paddy soil using visible and near-infrared spectroscopy. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e105708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, S.; Yang, X.; Zhang, J.; Li, G. Quantitative analysis of soil nitrogen, organic carbon, available phosphorous, and available potassium using near-infrared spectroscopy combined with variable selection. Soil Sci. 2014, 179, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, S.R.; Söderström, M.; Eriksson, J.; Isendahl, C.; Stenborg, P.; Demattê, J.M. Determining soil properties in Amazonian Dark Earths by reflectance spectroscopy. Geoderma 2015, 237, 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, W.; Adamchuk, V.I.; Biswas, A.; Dhawale, N.M.; Sudarsan, B.; Zhang, Y.; Rossel, R.A.V.; Shi, Z. Assessment of soil properties in situ using a prototype portable MIR spectrometer in two agricultural fields. Biosyst. Eng. 2016, 152, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sila, A.; Pokhariyal, G.; Shepherd, K. Evaluating regression-kriging for mid-infrared spectroscopy prediction of soil properties in western Kenya. Geoderma Reg. 2017, 10, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vibhute, A.D.; Kale, K.V.; Mehrotra, S.C.; Dhumal, R.K.; Nagne, A.D. Determination of soil physicochemical attributes in farming sites through visible, near-infrared diffuse reflectance spectroscopy and PLSR modeling. Ecol. Process. 2018, 7, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, F.; Du, C.W.; Zhou, J.M.; Shen, Y.Z. Investigation of soil properties using different techniques of mid-infrared spectroscopy. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2019, 70, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanderman, J.; Savage, K.; Dangal, S.R. Mid-infrared spectroscopy for prediction of soil health indicators in the United States. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2020, 84, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamura, K.; Nishigaki, T.; Andriamananjara, A.; Rakotonindrina, H.; Tsujimoto, Y.; Moritsuka, N.; Rabenarivo, M.; Razafimbelo, T. Using a one-dimensional convolutional neural network on visible and near-infrared spectroscopy to improve soil phosphorus prediction in Madagascar. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghi, R.K.; Pérez-Fernández, E.; Robertson, A.H.J. Prediction of various soil properties for a national spatial dataset of Scottish soils based on four different chemometric approaches: A comparison of near infrared and mid-infrared spectroscopy. Geoderma 2021, 396, 115073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pérez, J.R.; Marcelo, V.; Pereira-Obaya, D.; García-Fernández, M.; Sanz-Ablanedo, E. Estimating soil properties and nutrients by visible and infrared diffuse reflectance spectroscopy to characterize vineyards. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelago, A.; Bibiso, M. Performance of mid infrared spectroscopy to predict nutrients for agricultural soils in selected areas of Ethiopia. Heliyon 2022, 8, e08733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, W.; Minasny, B.; Jones, E.; McBratney, A. To spike or to localize? Strategies to improve the prediction of local soil properties using regional spectral library. Geoderma 2022, 406, 115508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singha, C.; Swain, K.C.; Sahoo, S.; Govind, A. Prediction of soil nutrients through PLSR and SVMR models by VIs-NIR reflectance spectroscopy. Egypt. J. Remote Sens. Space Sci. 2023, 26, 901–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Yan, C.; Yuan, J.; Ding, N.; Chen, Z. Prediction of soil properties based on characteristic wavelengths with optimal spectral resolution by using Vis-NIR spectroscopy. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2023, 293, 122452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, S.H.; Jang, H.J.; Ng, W.; Minasny, B.; Kim, S.H.; Shim, J.H.; Roh, A.; Kwon, S.I.; Yun, J.J. Predicting soil properties for fertiliser recommendation in South Korea using MIR spectroscopy. Geoderma Reg. 2024, 39, e00871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammadov, E.; Denk, M.; Mamedov, A.I.; Glaesser, C. Predicting Soil Properties for Agricultural Land in the Caucasus Mountains Using Mid-Infrared Spectroscopy. Land 2024, 13, 1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitu, S.M.; Smith, C.; Sanderman, J.; Ferguson, R.R.; Shepherd, K.; Ge, Y. Evaluating consistency across multiple NeoSpectra (compact Fourier transform near-infrared) spectrometers for estimating common soil properties. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2024, 88, 1324–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, K.; Li, Y.; Huan, W.; Weng, X.; Wu, B.; Chen, Z.; Liang, H.; Feng, H. A novel near infrared spectroscopy analytical strategy for soil nutrients detection based on the DBO-SVR method. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2024, 315, 124259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

. The diamond

. The diamond  denotes the overall effect (r) of the sample size on the prediction accuracy.

denotes the overall effect (r) of the sample size on the prediction accuracy.

. The diamond

. The diamond  denotes the overall effect (r) of the sample size on the prediction accuracy.

denotes the overall effect (r) of the sample size on the prediction accuracy.

. The diamond

. The diamond  denotes the overall effect (r) of the sample size on the prediction accuracy.

denotes the overall effect (r) of the sample size on the prediction accuracy.

. The diamond

. The diamond  denotes the overall effect (r) of the sample size on the prediction accuracy.

denotes the overall effect (r) of the sample size on the prediction accuracy.

. The diamond

. The diamond  denotes the overall effect (r) of concentration on the prediction accuracy.

denotes the overall effect (r) of concentration on the prediction accuracy.

. The diamond

. The diamond  denotes the overall effect (r) of concentration on the prediction accuracy.

denotes the overall effect (r) of concentration on the prediction accuracy.

. The diamond

. The diamond  denotes the overall effect (r) of concentration on the prediction accuracy.

denotes the overall effect (r) of concentration on the prediction accuracy.

. The diamond

. The diamond  denotes the overall effect (r) of concentration on the prediction accuracy.

denotes the overall effect (r) of concentration on the prediction accuracy.

| Infrared Region | P (%) | K (%) | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visible near-infrared | 20.5 | 17.9 | 38.4 |

| Near-infrared | 10.3 | 13.7 | 24 |

| Mid-infrared | 18.8 | 18.8 | 37.6 |

| Spectrometer | |||

| Carry 500 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 3.4 |

| NIRS 6500 | 4.3 | 3.4 | 7.8 |

| FT-IR-Spectrometer | 19.8 | 21.6 | 41.4 |

| ASD Field Spec | 12.9 | 12.1 | 25.0 |

| NIR portable spectrometer | 1.7 | 0.0 | 1.7 |

| XDS rapid content analyzer | 4.3 | 4.3 | 8.6 |

| Foss NIRS 5000 | 0.9 | 3.4 | 4.3 |

| Neo spectra | 2.6 | 3.4 | 6.0 |

| NIR-M-R2 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1.7 |

| Regression Model | |||

| Principal component regression | 0.9 | 2.2 | 3.1 |

| Partial least squares | 34.2 | 32.5 | 66.7 |

| Multiple linear regression | 5.1 | 2.1 | 7.2 |

| Convolutional neural network | 2.6 | 3.4 | 6 |

| Cubist | 3.4 | 1.7 | 5.1 |

| Artificial neural networks | 1.7 | 1.7 | 3.4 |

| Support vector regression | 3.4 | 2.6 | 6.0 |

| Multivariate adaptive regression splines | 0.0 | 0.9 | 0.9 |

| Chemical method | |||

| Mehlich 1 | 5.8 | 1.2 | 7.0 |

| Mehlich 3 | 19.8 | 15.1 | 34.9 |

| Ammonium fluoride | 1.2 | 0.0 | 1.2 |

| Ammonium acetate | 1.2 | 15.1 | 16.3 |

| Ammonium oxalate | 2.3 | 0.0 | 2.3 |

| Calcium acetate | 0.0 | 2.3 | 2.3 |

| Ammonium chloride | 0.0 | 3.5 | 3.5 |

| Bray-P | 8.1 | 0.0 | 8.1 |

| Olsen-P | 12.8 | 0.0 | 12.8 |

| Resins | 2.3 | 0.0 | 2.3 |

| Silver-thiourea | 0.0 | 2.3 | 2.3 |

| Water extraction | 1.2 | 0.0 | 1.2 |

| Bicarbonate extractable | 3.5 | 1.2 | 4.7 |

| Lancaster method | 1.2 | 0.0 | 1.2 |

| Statistics | Sample Size | Concentration (mg/kg Soil) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | K | Average | P | K | Average | |

| r | 75% | 68% | 72% | 62% | 64% | 63% |

| Z | 7.48 | 10.8 | 9.14 | 6.06 | 9.84 | 6.45 |

| Heterogeneity (p-value) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| RE model (p-value) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fakude, S.B.; Soundy, P.; Sosibo, N.Z. Effect of Selected Factors on the Prediction Accuracy of Plant-Available Phosphorus and Potassium: A Global Meta-Analysis for Infrared Spectroscopy Protocol. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2771. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122771

Fakude SB, Soundy P, Sosibo NZ. Effect of Selected Factors on the Prediction Accuracy of Plant-Available Phosphorus and Potassium: A Global Meta-Analysis for Infrared Spectroscopy Protocol. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2771. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122771

Chicago/Turabian StyleFakude, Sithembiso Bethwell, Puffy Soundy, and Nondumiso Zanele Sosibo. 2025. "Effect of Selected Factors on the Prediction Accuracy of Plant-Available Phosphorus and Potassium: A Global Meta-Analysis for Infrared Spectroscopy Protocol" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2771. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122771

APA StyleFakude, S. B., Soundy, P., & Sosibo, N. Z. (2025). Effect of Selected Factors on the Prediction Accuracy of Plant-Available Phosphorus and Potassium: A Global Meta-Analysis for Infrared Spectroscopy Protocol. Agronomy, 15(12), 2771. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122771