Progress and Prospects of Research on the Role of Phosphatidic Acid in Response to Adverse Stress in Plants

Abstract

1. Introduction

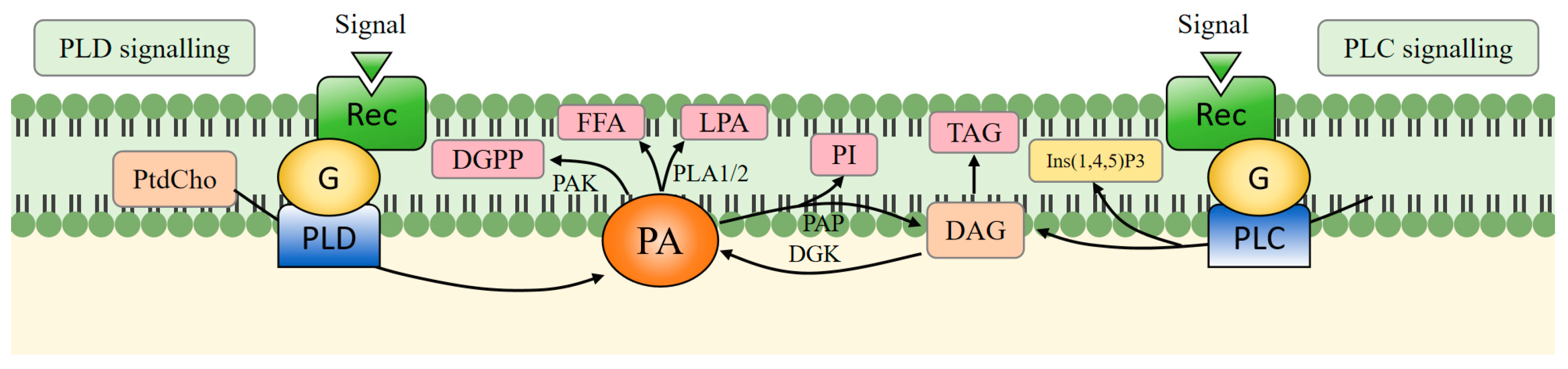

2. PA Biosynthesis, Metabolic Pathway

2.1. Synthesis Pathway

2.2. Metabolic Pathway

2.3. Cross-Talk Between Different Pathways Involved in PA Synthesis and Metabolism

3. Effects of PA on Plant Membrane Systems

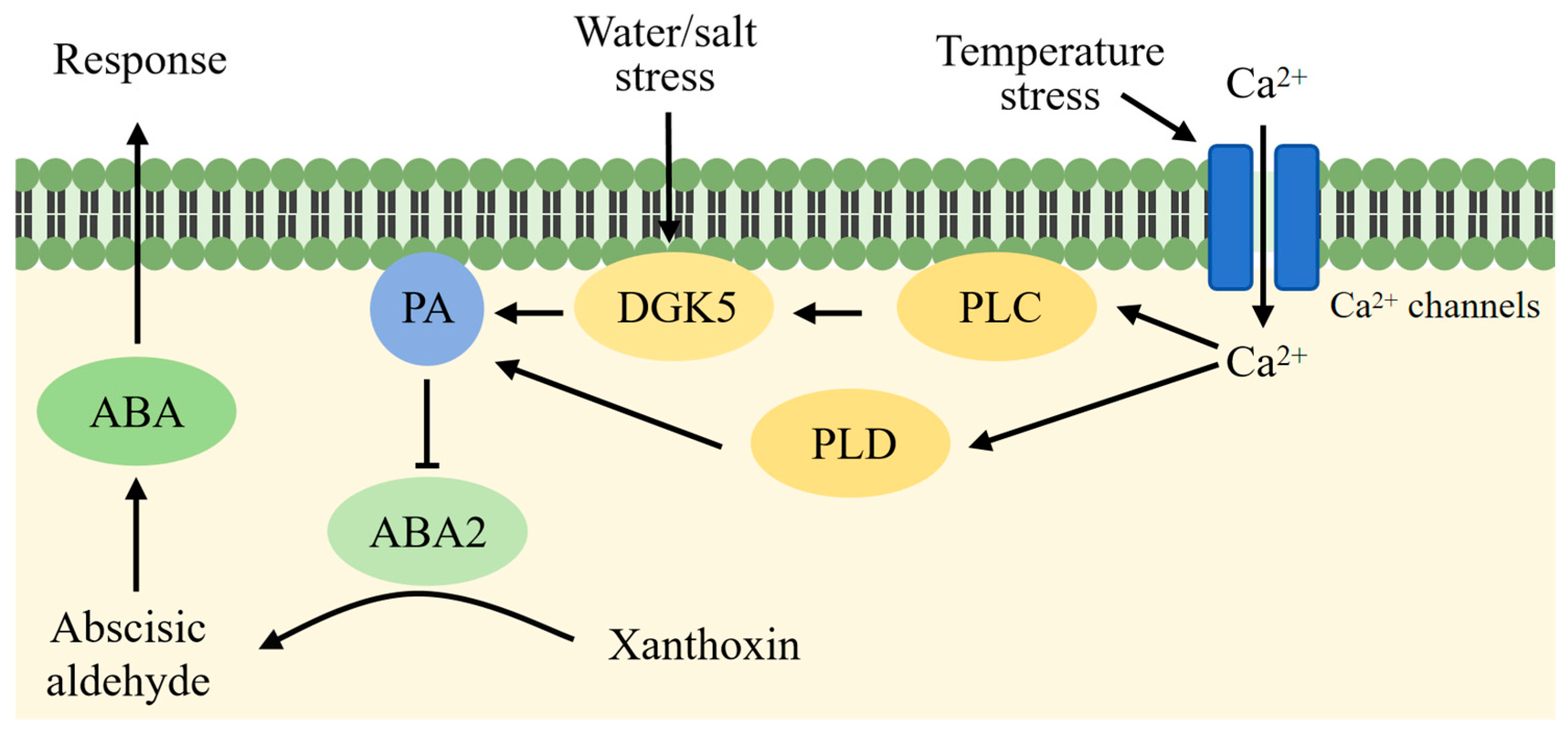

4. Role of PA in Abiotic Stresses

4.1. PA Is Involved in the Regulation of Drought Stress in Plants

4.2. PA Is Involved in the Regulation of Plant Cold Stress

4.3. PA Is Involved in the Regulation of Salt Stress in Plants

5. Role of PA in Biotic Stresses

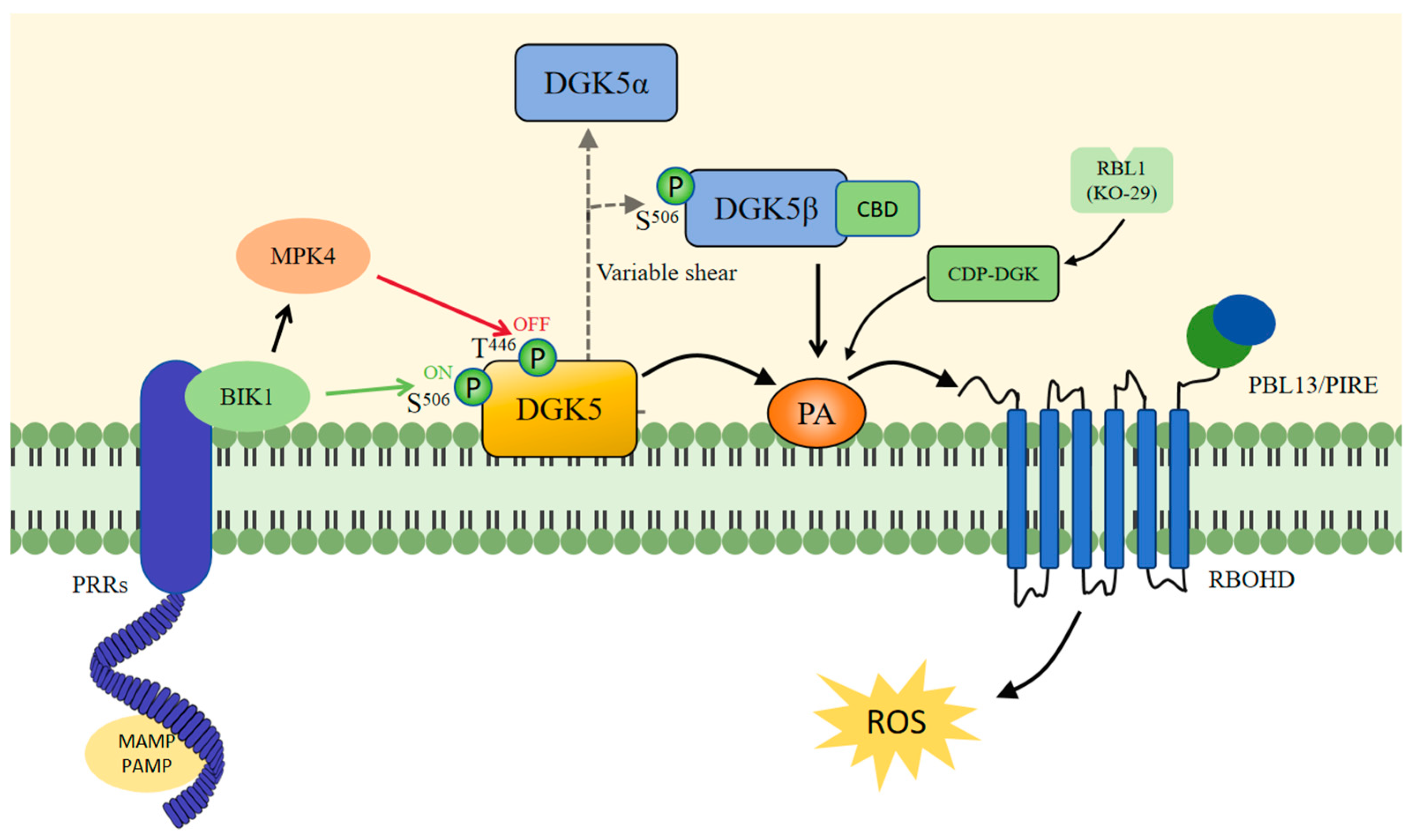

5.1. DGK5 Regulates PA to Influence Plant Immunity

5.2. RBL1-Mediated Reprogramming of Lipid Metabolism Enhances Rice Immune Response by Regulating PA Accumulation

5.3. PLD, PLA and PA Responses in Plant Biotic Stresses

5.4. PA and Actin Remodeling in Biotic Stress Response

6. Role of PA in the Regulation of Phytohormones

6.1. PA in Regulation of ABA

6.2. PA in Regulation of Auxin (IAA)

6.3. PA in Regulation of Salicylic Acid (SA)

6.4. PA in Regulation of Other Plant Hormones

7. Outlook on the Future Research Direction of PA

7.1. Application and Limitations of Traditional Research Methods

7.2. The Development and Breakthrough of New Modern Technologies

7.3. Future Research Directions and Challenges

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABA | Abscisic acid |

| ABA2 | ABA-DEFICIENT 2 |

| Bgh | Blumeria graminis f. sp. Hordei |

| BIK1 | Botrytis cinerea-inducible kinase 1 |

| BR | Oleoresin lactones |

| CaM | Calmodulin |

| CBD | Calmodulin-binding domain |

| CDP-DAG | Cytidine diphosphate-diacylglycerol |

| CP | Capping protein |

| CTR1 | Con-insensitive 1 |

| DAG | Diacylglycerol |

| DGK | Diacylglycerol kinase |

| DGPP | Diglycerol pyrophosphate |

| ET | Ethylene |

| FFAs | Free fatty acids |

| GAPDH | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| HT | High temperature |

| IAA | Auxin |

| JA | Jasmonic acid |

| LMM | Lesion-mimicking mutant |

| LPA | Lysophosphatidic acid |

| LPP | Lipid phosphatase |

| LT | Low temperature |

| MAMP | Microbe-associated molecular patterns |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MPK4 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase 4 |

| NADPH | nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate |

| NLR | Nucleotide-binding leucine-rich repeat receptor |

| NO | nitric oxide |

| OE | Ectopic overexpression |

| OsBIDK1 | Rice diacylglycerol kinase |

| PA | Phosphatidic acid |

| PAK | Phosphatidic acid kinase |

| PAMP | Pathogen-associated molecular patterns |

| PAP | Phosphodiesterase |

| PC | Phosphatidylcholine |

| PE | Phosphatidylethanolamine |

| PG | Phosphatidylglycerol |

| PI | Phosphatidylinositol |

| PLA | Phospholipase A |

| PLC | Phospholipase C |

| PLD | Phospholipase D |

| PRRs | Pattern recognition receptors |

| PTI | Pattern-triggered immunity |

| PVY | Potato virus Y |

| RBL1 | Blast1 resistance |

| RBOHD | Respiratory burst oxidase homolog D |

| RGS1 | Regulatory G protein signaling protein |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SA | Salicylic acid |

| WT | Wild-type |

References

- Dai, Y.J.; Luo, X.F.; Zhou, W.G.; Chen, F.; Shuai, H.W.; Yang, W.Y.; Wang, J.; Shu, K. Plant systemic signaling under biotic and abiotic stresses conditions. Chin. Bull. Bot. 2019, 54, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhukovsky, M.A.; Filograna, A.; Luini, A.; Corda, D.; Valente, C. Phosphatidic acid in membrane rearrangements. FEBS Lett. 2019, 593, 2428–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noack, L.C.; Jaillais, Y. Functions of anionic lipids in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2020, 71, 71–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munnik, T.; Mongrand, S.; Zársky, V.; Blatt, M. Dynamic membranes–the indispensable platform for plant growth, signaling, and development. Plant Physiol. 2021, 185, 547–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colin, L.A.; Jaillais, Y. Phospholipids across scales: Lipid patterns and plant development. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2020, 53, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokotylo, I.; Kravets, V.; Martinec, J.; Ruelland, E. The phosphatidic acid paradox: Too many actions for one molecule class? Lessons from plants. Prog. Lipid Res. 2018, 71, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furt, F.; Simon-Plas, F.; Mongrand, S. Lipids of the plant plasma membrane. In The Plant Plasma Membrane; Murphy, A.S., Schulz, B., Peer, W., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; Volume 9, pp. 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin, Y.; Wakao, S.; Fan, J.L.; Benning, C. Loss of plastidic lysophosphatidic acid acyltransferase causes embryo-lethality in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2004, 45, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Testerink, C.; Munnik, T. Molecular, cellular, and physiological responses to phosphatidic acid formation in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 62, 2349–2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testerink, C.; Munnik, T. Phosphatidic acid: A multifunctional stress signaling lipid in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2005, 10, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arisz, S.A.; Munnik, T. Distinguishing phosphatidic acid pools from de novo synthesis, PLD, and DGK. Methods Mol. Biol. 2013, 1009, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welti, R.; Li, W.; Li, M.; Sang, Y.; Biesiada, H.; Zhou, H.E.; Rajashekar, C.B.; Williams, T.D.; Wang, X. Profiling membrane lipids in plant stress responses: Role of phospholipase Dα in freezing-induced lipid changes in Arabidopsis. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 31994–32002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altúzar-Molina, A.R.; Muñoz-Sánchez, J.A.; Vázquez-Flota, F.; Monforte-González, M.; Racagni-Di Palma, G.; Hernández-Sotomayor, S.M.T. Phospholipidic signaling and vanillin production in response to salicylic acid and methyl jasmonate in Capsicum chinense J. cells. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2011, 49, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.M.; Devalah, S.P.; Zhang, W.H.; Welti, R. Signaling functions of phosphatidic acid. Prog. Lipid Res. 2006, 45, 250–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Schooten, B.; Testerink, C.; Munnik, T. Signalling diacylglycerol pyrophosphate, a new phosphatidic acid metabolite. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2006, 1761, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yu, Y.; Wang, S.; Yang, J.; Ai, X.; Zhang, N.; Zhao, X.; Liu, X.; Zhong, C.; Yu, H. Genome-wide characterization of phospholipase D family genes in allotetraploid peanut and its diploid progenitors revealed their crucial roles in growth and abiotic stress responses. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1102200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. Regulatory functions of phospholipase D and phosphatidic acid in plant growth, development, and stress responses. Plant Physiol. 2005, 139, 566–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drabik, D.; Czogalla, A. Simple does not Mean Trivial: Behavior of phosphatidic acid in lipid mono- and bilayers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolesnikov, Y.; Kretynin, S.; Bukhonska, Y.; Pokotylo, I.; Ruelland, E.; Martinec, J.; Kravets, V. Phosphatidic acid in plant hormonal signaling: From target proteins to membrane conformations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S. Heterotrimeric G-protein regulatory circuits in plants: Conserved and novel mechanisms. Plant Signal Behav. 2017, 12, e1325983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.M. Lipid signaling. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2004, 7, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J. Phospholipase D and phosphatidic acid in plant defence response: From protein-protein and lipid-protein interactions to hormone signalling. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 1721–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.Y.; Devaiah, S.P.; Pan, X.; Isaac, G.; Welti, R.; Wang, X. AtPLAI is an acyl hydrolase involved in basal jasmonic acid production and Arabidopsis resistance to Botrytis cinerea. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 18116–18128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Caldo, K.M.P.; Pal-Nath, D.; Ozga, J.; Lemieux, M.J.; Weselake, R.J.; Chen, G. Properties and biotechnological applications of acyl-coa: Diacylglycerol acyltransferase and phospholipid: Diacylglycerol acyltransferase from terrestrial plants and microalgae. Lipids 2018, 53, 663–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waghule, T.; Saha, R.N.; Alexander, A.; Singhvi, G. Tailoring the multi-functional properties of phospholipids for simple to complex self-assemblies. J. Control. Release 2022, 349, 460–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Huo, Y.; Yang, N.; Wei, T. Phosphatidic acid: From biophysical properties to diverse functions. FEBS J. 2024, 291, 1870–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulga, Y.V.; Topham, M.K.; Epand, R.M. Regulation and functions of diacylglycerol kinases. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 6186–6208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Ma, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Yang, Y.; Yin, P.; Wan, X.; Ma, S.; Shang, D. DGKs in lipid signaling and disease intervention: Structural basis, pathological mechanisms, and emerging therapeutic strategies. Cell Discov. 2025, 30, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naor, Z. Signaling by G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR): Studies on the GnRH receptor. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2009, 30, 10–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hisatsune, C.; Nakamura, K.; Kuroda, Y.; Nakamura, T.; Mikoshiba, K. Amplification of Ca²⁺ signaling by diacylglycerol-mediated inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate production. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 11723–11730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Xu, H.; Yi, H.; Yang, L.; Kong, Z.; Zhang, L.; Xue, S.; Jia, H.; Ma, Z. Resistance to hemi-biotrophic F. graminearum infection is associated with coordinated and ordered expression of diverse defense signaling pathways. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e19008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amokrane, L.; Pokotylo, I.; Acket, S.; Ducloy, A.; Troncoso-Ponce, A.; Cacas, J.-L.; Ruelland, E. Phospholipid signaling in crop plants: A field to explore. Plants 2024, 13, 1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraschin, F.; Kulcheski, F.R.; Segatto, A.; Trenz, T.S.; Barrientos-Diaz, O.; Margis-Pinheiro, M.; Margis, R.; Turchetto-Zolet, A.C. Enzymes of glycerol-3-phosphate pathway in triacylglycerol synthesis in plants: Function, biotechnological application and evolution. Prog. Lipid Res. 2019, 73, 46–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooijman, E.E.; Chupin, V.; de Kruijff, B.; Burger, K.N.J. Spontaneous curvature of phosphatidic acid and lysophosphatidic acid. Biochemistry 2005, 44, 2097–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, B.P.; Loewen, C.J.R. Putting the pH into phosphatidic acid signaling. BMC Biol. 2010, 8, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, R.; Nagao, K.; Taniuchi, K.; Tsuchiya, M.; Kato, U.; Hara, Y.; Inaba, T.; Kobayashi, T.; Sasaki, Y.; Akiyoshi, K.; et al. Development of a novel tetravalent synthetic peptide that binds to phosphatidic acid. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0131668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, B.P.; Shin, J.J.; Orij, R.; Chao, J.T.; Li, S.C.; Guan, X.L.; Khong, A.; Jan, E.; Wenk, M.R.; Prinz, W.A.; et al. Phosphatidic acid is a pH biosensor that links membrane biogenesis to metabolism. Science 2010, 329, 1085–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichmann, T.O.; Lass, A. DAG tales: The multiple faces of diacylglycerol-stereochemistry, metabolism, and signaling. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2015, 72, 3931–3952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.Y.; Zhao, J.; Guo, L.; Kim, S.C.; Deng, X.J.; Wang, G.L.; Li, M.; Wang, X. Plant phospholipases D and C and their diverse functions in stress responses. Prog. Lipid Res. 2016, 62, 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.Y.; Wang, P.P.; Song, H.D.; Jing, W.; Shen, L.K.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, W. Corrigendum to: Phosphatidic acid binds to and regulates guanine nucleotide exchange factor 8 (GEF8) activity in Arabidopsis. Funct. Plant Biol. 2021, 48, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, S.R.; Pandey, S. Phosphatidic acid binding inhibits RGS1 activity to affect specific signaling pathways in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2017, 90, 466–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, F.; Li, J.; Ai, Y.; Shangguan, K.; Li, P.; Lin, F.; Wang, Y. DGK5β-derived phosphatidic acid regulates ROS production in plant immunity by stabilizing NADPH oxidase. Cell Host Microbe 2024, 32, 425–440.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepler, P.K. Calcium: A central regulator of plant growth and development. Plant Cell 2005, 17, 2142–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.Y.; Hong, Y.Y.; Wang, X.M. Phospholipase D- and phosphatidic acid-mediated signaling in plants. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2009, 1791, 927–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taj, G.; Giri, P.; Tasleem, M.; Kumar, A. Approaches to plant stress and their management. In Plant Biology and Biotechnology; Bahadur, B., Venkat Rajam, M., Sahijram, L., Krishnamurthy, K.V., Eds.; Springer: New Delhi, India, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Jiang, X.; Yuan, Z. Plant responses and adaptations to salt stress: A review. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maryam, A.; Khan, R.I.; Abbas, M.; Hussain, K.; Muhammad, S.; Sabir, M.A.; Ahmed, T.; Khalid, M.F. Beyond the membrane: The pivotal role of lipids in plants abiotic stress adaptation. Plant Growth Regul. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasulla, F.; Vom Dorp, K.; Dombrink, I.; Zähringer, U.; Gisch, N.; Dörmann, P.; Bartels, D. The role of lipid metabolism in the acquisition of desiccation tolerance in Craterostigma plantagineum: A comparative approach. Plant J. 2013, 75, 726–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Lin, C.; Peng, X.Y.; Zhang, M.S.; Wu, J.M.; Meng, C.M.; Ge, S.C.; Liu, Y.F.; Su, Y. R3-MYB proteins OsTCL1 and OsTCL2 modulate seed germination via dual pathways in rice. Crop J. 2023, 11, 1752–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.Y.; Zhu, H.Y.; Zhang, Q.; Li, M.Y.; Yan, M.; Wang, R.; Wnag, L.L.; Welti, R.; Zhang, W.; Wang, X. Phospholipase Dα1 and phosphatidic acid regulate NADPH oxidase activity and production of reactive oxygen species in ABA-mediated stomatal closure in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2009, 21, 2357–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, L.K.; Yuan, K.L.; Huang, X.S.; Zhang, S.L. Genome-wide identification of the Phospholipase D (PLD) gene family in Chinese white pear (Pyrus bretschneideri) and the role of PbrPLD2 in drought resistance. Plant Sci. 2025, 350, 112286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Wang, W.L.; Fang, Z.F.; Wu, S.M.; Chen, L.L.; Chen, J.; Zhang, W.; Wang, F.; Sun, T.; Xiang, L.; et al. Genome-wide analysis of the phospholipase Ds in perennial ryegrass highlights LpABFs-LpPLDδ3 cascade modulated osmotic and heat stress responses. Plant Cell Environ. 2025, 48, 1115–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Devaiah, S.P.; Narasimhan, R.; Pan, X.Q.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Zhang, W.H.; Wang, X.M. Cytosolic glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenases interact with phospholipase Dδ to transduce hydrogen peroxide signals in the Arabidopsis response to stress. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 2200–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.W.; Yao, S.B.; Kim, S.C.; Wang, X.M. Lipid phosphorylation by a diacylglycerol kinase suppresses ABA biosynthesis to regulate plant stress responses. Mol. Plant 2024, 17, 342–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, P.; Bleuler, S.; Laule, O.; Martin, F.; Ivanov, N.V.; Campanoni, P.; Oishi, K.; Lugon-Moulin, N.; Wyss, M.; Hruz, T.; et al. ExpressionData-A public resource of high quality curated datasets representing gene expression across anatomy, development and experimental conditions. Biodata Min. 2014, 7, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Li, Z.; Kong, X.; Khan, A.; Ullah, N.; Zhang, X. Plant coping with cold stress: Molecular and physiological adaptive mechanisms with future perspectives. Cells 2025, 14, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinière, A.; Shvedunova, M.; Thomson, A.J.W.; Evans, N.H.; Penfield, S.; Runions, J.; McWatters, H.G. Homeostasis of plasma membrane viscosity in fluctuating temperatures. New Phytol. 2011, 192, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.Q.; Li, M.Y.; Zhang, W.H.; Welti, R.; Wang, X.M. The plasma membrane-bound phospholipase Dδ enhances freezing tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat. Biotechnol. 2004, 22, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritonga, F.N.; Chen, S. Physiological and molecular mechanism involved in cold stress tolerance in plants. Plants 2020, 9, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.J.; Wang, Z.H.; Wang, J.J.; Mao, X.J.; He, W.Y.; Hu, W.T.; Tang, M.; Chen, H. Mycorrhizal and non-mycorrhizal perennial ryegrass roots exhibit differential regulation of lipid and Ca2+ signaling pathways in response to low and high temperature stresses. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 216, 109099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Margutti, M.P.; Vilchez, A.C.; Sosa-Alderete, L.; Agostini, E.; Villasuso, A.L. Lipid signaling and proline catabolism are activated in barley roots (Hordeum vulgare L.) during recovery from cold stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 206, 108208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, L.M.; Schumaker, K.S.; Zhu, J.K. Cell signaling during cold, drought, and salt stress. Plant Cell 2002, 14, S165–S183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruelland, E.; Cantrel, C.; Gawer, M.; Kader, J.C.; Zachowski, A. Activation of phospholipases C and D is an early response to a cold exposure in Arabidopsis suspension cells. Plant Physiol. 2002, 130, 999–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, Z.H.; Niu, L.Y.; Yue, G.D.; Yang, A.F.; Zhang, J.R. Cloning and expression analysis of some genes involved in the phosphoinositide and phospholipid signaling pathways from maize (Zea mays L.). Gene 2008, 426, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.J.; Yang, Y.C.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, L.P.; Xu, L.; Chen, Q.F.; Yu, L.J.; Xiao, S. Diacylglycerol acyltransferase and diacylglycerol kinase modulate triacylglycerol and phosphatidic acid production in the plant response to freezing stress. Plant Physiol. 2018, 177, 1303–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Khan, S.A.; Abbas, A.; Hussain, S.; Rehman, A.; Iqbal, J.; Ahmad, F. Drought and salinity effects on plant growth: A comprehensive review. SABRAO J. Breed. Genet. 2024, 56, 2331–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julkowska, M.M.; Testerink, C. Tuning plant signaling and growth to survive salt. Trends Plant Sci. 2015, 20, 586–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Song, T.; Wallrad, L.; Kudla, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, W. Tissue-specific accumulation of pH-sensing phosphatidic acid determines plant stress tolerance. Nat. Plants 2019, 5, 1012–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwish, E.; Testerink, C.; Khalil, M.; El-Shihy, O.; Munnik, T. Phospholipid signaling responses in salt-stressed rice leaves. Plant Cell Physiol. 2009, 50, 986–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Kim, S.C.; Deng, X.J.; Hong, Y.Y.; Wang, X.M. Diacylglycerol kinase and associated lipid mediators modulate rice root architecture. New Phytol. 2019, 223, 261–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLoughlin, F.; Testerink, C. Phosphatidic acid, a versatile water-stress signal in roots. Front. Plant Sci. 2013, 4, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLoughlin, F.; Arisz, S.A.; Dekker, H.L.; Kramer, G.; de Koster, C.G.; Haring, M.A.; Munnik, T.; Testerink, C. Identification of novel candidate phosphatidic acid-binding proteins involved in the salt-stress response of Arabidopsis thaliana roots. Biochem. J. 2013, 450, 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.C.; Guo, L.; Wang, X.M. Phosphatidic acid binds to cytosolic glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase and promotes its cleavage in Arabidopsis. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 11834–11844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudsocq, M.; Barbier-Brygoo, H.; Laurière, C. Identification of nine sucrose nonfermenting 1-related protein kinases 2 activated by hyperosmotic and saline stresses in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 41758–41766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Merino, F.C.; Arana-Ceballos, F.A.; Trejo-Téllez, L.I.; Skirycz, A.; Brearley, C.A.; Dörmann, P.; Mueller-Roeber, B. Arabidopsis AtDGK7, the smallest member of plant diacylglycerol kinases (DGKs), displays unique biochemical features and saturates at low substrate concentration: The DGK inhibitor R59022 differentially affects AtDGK2 and AtDGK7 activity in vitro and alters plant growth and development. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 34888–34899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Z.Y.; Liu, Z.; Yao, J.; Yin, K.X.; Yan, C.X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, J.; Zhao, N.; et al. Populus euphratica PeNADP-ME interacts with PePLD δ to mediate sodium and ROS homeostasis under salinity stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 210, 108600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, Y.; Zhou, C.; Feng, N.; Zheng, D.; Shen, X.; Rao, G.; Huang, Y.; Cai, W.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, R. Transcriptomic and lipidomic analysis reveals complex regulation mechanisms underlying rice roots’ response to salt stress. Metabolites 2024, 14, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, M.X.; Liu, X.L.; Gao, H.F.; Zhang, B.B.; Peng, F.T.; Xiao, Y.S.; Wu, X. Phosphatidylcholine enhances homeostasis in peach seedling cell membrane and increases its salt stress tolerance by phosphatidic acid. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.X.; Liu, X.L.; Zhang, B.B.; Yu, W.; Xiao, Y.S.; Peng, F.T.; Li, H.; Zhang, X. Lipid metabolomic and transcriptomic analyses reveal that phosphatidylcholine enhanced the resistance of peach seedlings to salt stress through phosphatidic acid. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 8846–8858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, S. Cellwall signaling in plant development and defense. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2022, 73, 323–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhang, Y. Plant immunity: Danger perception and signaling. Cell 2020, 181, 978–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngou, B.P.M.; Jones, J.D.G.; Ding, P.T. Plant immune networks. Trend. Plant Sci. 2022, 27, 255–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlot, A.C.; Sales, J.H.; Lenk, M.; Bauer, K.; Brambilla, A.; Sommer, A.; Chen, Y.; Wenig, M.; Nayem, S. Systemic propagation of immunity in plants. New Phytol. 2021, 229, 1234–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagi, M.; Fluhr, R. Production of reactive oxygen species by plant NADPH oxidases. Plant Physiol. 2006, 141, 336–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFalco, T.A.; Zipfel, C. Molecular mechanisms of early plant pattern-triggered immune signaling. Mol. Cell 2021, 81, 3449–3467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalachova, T.; Skrabálková, E.; Pateyron, S.; Soubigou-Taconnat, L.; Djafi, N.; Collin, S.; Sekereš, J.; Burketová, L.; Potocký, M.; Pejchar, P.; et al. Diacylglucerol kinase 5 participates in flagellin-induced signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2022, 190, 1978–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, C.F.; Laxalt, A.M.; Bargmann, B.O.R.; De Wit, P.; Joosten, M.; Munnik, T. Phosphatidic acid accumulation is an early response in the Cf-4/Avr4 interaction. Plant J. 2004, 39, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.D.; Chen, J.; Zhang, H.J.; Song, F.M. Overexpression of a rice diacylglycerol kinase gene OsBIDK1 enhances disease resistance in transgenic tobacco. Mol. Cells 2008, 26, 258–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laxalt, A.M.; Munnik, T. Phospholipid signalling in plant defence. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2002, 5, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Ma, X.; Zhang, C.; Kim, S.I.; Li, B.; Xie, Y.; Yeo, I.; Thapa, H.; Chen, S.; Devarenne, T.P.; et al. Dual phosphorylation of DGK5-mediated PA burst regulates ROS in plant immunity. Cell 2024, 187, 609–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sha, G.; Sun, P.; Kong, X.J.; Han, X.Y.; Sun, Q.P.; Fouillen, L.; Zhao, J.; Li, Y.; Yang, L.; Wang, Y.; et al. Genome editing of a rice CDP-DAG synthase confers multipathogen resistance. Nature 2023, 618, 1017–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Waters, D.L.E.; Rose, T.J.; Bao, J.S.; King, G.J. Phospholipids in rice: Significance in grain quality and health benefits: A review. Food Chem. 2013, 139, 1133–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, T.L.; Betsuyaku, S.; Inada, N.; Ebine, K.; Fujimoto, M.; Uemura, T.; Takano, Y.; Fukuda, H.; Nakano, A.; Ueda, T. Enrichment of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate in the extra-invasive hyphal membrane promotes colletotrichum infection of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2019, 60, 1514–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Q.W.; Yao, S.B.; Wang, X.M.; Li, G.T. Fine-tuning phosphatidic acid production for optimal plant stress responses. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2024, 49, 663–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorrain, S.; Vailleau, F.; Balaqué, C.; Roby, D. Lesion mimic mutants: Keys for deciphering cell death and defense pathways in plants? Trends Plant Sci. 2003, 8, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinosa, F.; Buhot, N.; Kwaaitaal, M.; Fahlberg, P.; Thordal-Christensen, H.; Ellerström, M.; Andersson, M.X. Arabidopsis phospholipase Dδ is involved in basal defense and nonhost resistance to powdery mildew fungi. Plant Physiol. 2013, 163, 896–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.Y.; Zhao, J.P.; Du, L.L.; Wang, P.K.; Sun, B.J.; Zhang, C.; Shi, Y.; Li, H.; Sun, H. Activation of MAPK-mediated immunity by phosphatidic acid in response to positive-strand RNA viruses. Plant Commun. 2024, 5, 100659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Berkey, R.; Blakeslee, J.J.; Lin, J.S.; Ma, X.F.; King, H.; Liddle, A.; Guo, L.; Munnik, T.; Wang, X.; et al. Arabidopsis phospholipase Dα1 and Dδ oppositely modulate EDS1-and SA-independent basal resistance against adapted powdery mildew. J. Exp. Bot. 2018, 69, 3675–3688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maduka, C.V.; Alhaj, M.; Ural, E.; Habeeb, O.M.; Kuhnert, M.M.; Smith, K.; Makela, A.V.; Pope, H.; Chen, S.; Hix, J.M.; et al. Polylactide degradation activates immune cells by metabolic reprogramming. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, e2304632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pleskot, R.; Potocky, M.; Pejchar, P.; Linek, J.; Bezvoda, R.; Martinec, J.; Valentová, O.; Novotná, Z.; Žárský, V. Mutual regulation of plant phospholipase D and the actin cytoskeleton. Plant J. 2010, 62, 494–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, M.X.; Guo, M.M.; Zhou, Z.Y.; Wang, B.X.; Pan, Q.; Li, J.J.; Zhou, J.; Li, J. MPK3-and MPK6-mediated VLN3 phosphorylation regulates actin dynamics during stomatal immunity in Arabidopsis. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, S.M.; Panstruga, R. Cytoskeleton functions in plant-microbe interactions. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2007, 71, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Qin, L.; Liu, G.S.; Peremyslov, V.V.; Dolja, V.V.; Wei, Y.D. Myosins XI modulate host cellular responses and penetration resistance to fungal pathogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 13996–14001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Staiger, C.J. Understanding cytoskeletal dynamics during the plant immune response. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2018, 56, 513–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henty-Ridilla, J.L.; Shimono, M.; Li, J.J.; Chang, J.H.; Day, B.; Staiger, C.J. The plant actin cytoskeleton responds to signals from microbe-associated molecular patterns. PLoS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.J.; Blanchoin, L.; Kovar, D.R.; Staiger, C.J. Arabidopsis capping protein (AtCP) is a heterodimer that regulates assembly at the barbed ends of actin filaments. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 44832–44842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pleskot, R.; Li, J.J.; Zársky, V.; Potocky, M.; Staiger, C.J. Regulation of cytoskeletal dynamics by phospholipase D and phosphatidic acid. Trends Plant Sci. 2013, 18, 496–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munné-Bosch, S. Phytohormones revisited: What makes a compound a hormone in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajguz, A.; Piotrowska-Niczyporuk, A. Biosynthetic pathways of hormones in plants. Metabolites 2023, 13, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, J.K.; Ye, M.L.; Li, B.; Noel, J.P. Co-evolution of hormone metabolism and signaling networks expands plant adaptive plasticity. Cell 2016, 166, 881–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janda, M.; Planchais, S.; Djafi, N.; Martinec, J.; Burketova, L.; Valentova, O.; Zachowski, A.; Ruelland, E. Phosphoglycerolipids are master players in plant hormone signal transduction. Plant Cell Rep. 2013, 32, 839–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.C.; Hwang, S.G.; Endo, A.; Okamoto, M.; Koshiba, T.; Cheng, W.H. Ectopic expression of abscisic acid 2/glucose insensitive 1 in Arabidopsis promotes seed dormancy and stress tolerance. Plant Physiol. 2007, 143, 745–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, B.; Munemasa, S.; Wang, C.; Nguyen, D.; Yong, T.M.; Yang, P.G.; Poretsky, E.; Belknap, T.F.; Waadt, R.; Alemán, F.; et al. Calcium specificity signaling mechanisms in abscisic acid signal transduction in Arabidopsis guard cells. Elife 2015, 4, e03599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Guzmán, M.; Apostolova, N.; Bellés, J.M.; Barrero, J.M.; Piqueras, P.; Ponce, M.R.; Micol, J.L.; Serrano, R.; Rodríguez, P.L. The short-chain alcohol dehydrogenase ABA2 catalyzes the conversion of xanthoxin to abscisic aldehyde. Plant Cell 2002, 14, 1833–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katagiri, T.; Ishiyama, K.; Kato, T.; Tabata, S.; Kobayashi, M.; Shinozaki, K. An important role of phosphatidic acid in ABA signaling during germination in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2005, 43, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Lin, F.; Xue, H.W. Genome-wide analysis of the phospholipase D family in Oryza sativa and functional characterization of PLDβ1 in seed germination. Cell Res. 2007, 17, 881–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleine-Vehn, J.; Friml, J. Polar targeting and endocytic recycling in auxin-dependent plant development. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2008, 24, 447–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Ganguly, A.; Baik, S.; Cho, H.T. Calcium-dependent protein kinase 29 modulates PIN-formed polarity and Arabidopsis development via its own phosphorylation code. Plant Cell 2021, 33, 3513–3531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Shen, L.; Guo, J.; Jing, W.; Qu, Y.; Li, W.; Bi, R.; Xuan, W.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, W. Phosphatidic acid directly regulates PINOID-dependent phosphorylation and activation of the PIN-formed2 auxin efflux transporter in response to salt stress. Plant Cell 2019, 31, 250–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, L.; Xu, B.; Zhao, S.; Lu, P.; He, Y.; Ye, T.; Feng, Y.; Wu, Y. Phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C2 functions in auxin-modulated root development. Plant Cell Environ. 2019, 42, 1441–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanteri, M.L.; Laxalt, A.M.; Lamattina, L. Nitric oxide triggers phosphatidic acid accumulation via phospholipase D during auxin-induced adventitious root formation in cucumber. Plant Physiol. 2008, 147, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, S.T.; Zhang, X.X.; Kong, W.; Yang, X.L.; Molnár, G.; Vondráková, Z.; Filepová, R.; Petrášek, T.; Friml, J.; Xue, H.-W. The lipid code-dependent phosphoswitch PDK1-D6PK activates PIN-mediated auxin efflux in Arabidopsis. Nat. Plants 2020, 6, 556–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Xue, H. Arabidopsis PLDζ2 regulates vesicle trafficking and is required for auxin response. Plant Cell 2007, 19, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Yang, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y. Salicylic acid: Biosynthesis and signaling. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2021, 72, 761–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, D.W.; Yang, L. Regeneration and defense: Unveiling the molecular interplay in plants. New Phytol. 2025, 246, 2484–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Xu, L.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y. Salicylic acid: The roles in plant immunity and crosstalk with other hormones. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2024, 67, 773–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruelland, E.; Pokotylo, I.; Djafi, N.; Cantrel, C.; Repellin, A.; Zachowski, A. Corrigendum: Salicylic acid modulates levels of phosphoinositide dependent-phospholipase C substrates and products to remodel the Arabidopsis suspension cell transcriptorne. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalachova, T.; Puga-Freitas, R.; Kravets, V.; Soubigou-Taconnat, L.; Repellin, A.; Balzergue, S.; Zachowski, A.; Ruelland, D. The inhibition of basal phosphoinositide-dependent phospholipase C activity in Arabidopsis suspension cells by abscisic or salicylic acid acts as a signalling hub accounting for an important overlap in transcriptome remodelling induced by these hormones. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2016, 123, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Butselaar, T.; Van Den Ackerveken, G. Salicylic acid steers the growth-immunity tradeoff. Trends Plant Sci. 2020, 25, 566–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagale, S.; Divi, U.K.; Krochko, J.E.; Keller, W.A.; Krishna, P. Brassinosteroid confers tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana and Brassica napus to a range of abiotic stresses. Planta 2007, 225, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, I.; Kaur, N.; Pati, P.K. Brassinosteroids: A promising option in deciphering remedial strategies for abiotic stress tolerance in rice. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Yang, R.; Sun, J. Regulation of crop agronomic traits and abiotic stress responses by brassinosteroids: A review. Sheng Wu Gong Cheng Xue Bao 2022, 38, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartman, S.; Liu, Z.G.; Van Veen, H.; Vicente, J.; Reinen, E.; Martopawiro, S.; Zhang, H.; Dongen, N.; Bosman, F.; Bassel, G.W.; et al. Ethylene-mediated nitric oxide depletion pre-adapts plants to hypoxia stress. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartman, S.; Sasidharan, R.; Voesenek, L. The role of ethylene in metabolic acclimations to low oxygen. New Phytol. 2021, 229, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooijman, E.E.; Tieleman, D.P.; Testerink, C.; Munnik, T.; Rijkers, D.T.S.; Burger, K.N.J.; Kruijff, B.D. An electrostatic/hydrogen bond switch as the basis for the specific interaction of phosphatidic acid with proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 11356–11364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, L.J.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Q.F.; Xiao, S. New insights into the role of lipids in plant hypoxia responses. Prog. Lipid Res. 2021, 81, 101072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, M.X.; Hamberg, M.; Kourtchenko, O.; Brunnström, A.; McPhail, K.L.; Gerwick, W.H.; Göbel, C.; Feussner, I.; Ellerström, M. Oxylipin profiling of the hypersensitive response in Arabidopsis thaliana: Formation of a novel oxo-phytodienoic acid-containing galactolipid, arabidopside E. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 31528–31537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, H.S.; Tamura, P.; Galeva, N.A.; Chaturvedi, R.; Roth, M.R.; Williams, T.D.; Wang, X.; Shah, J.; Shah, J.; Welti, R. Direct infusion mass spectrometry of oxylipin-containing Arabidopsis membrane lipids reveals varied patterns in different stress responses. Plant Physiol. 2012, 158, 324–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Shen, Q.; Qi, Y.; Yan, H.; Nie, H.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, T.; Katagiri, F.; Tang, D. BR-signaling kinase1 physically associates with flagellin sensing2 and regulates plant innate immunity in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2013, 25, 1143–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bou Khalil, M.; Hou, W.; Zhou, H.; Elisma, F.; Swayne, L.A.; Blanchard, A.P.; Yao, Z.; Bennett, S.A.L.; Figeys, D. Lipidomics era: Accomplishments and challenges. Mass. Spectrom. Rev. 2010, 29, 877–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Wang, Q.; Ding, W. Recent progress in the imaging detection of enzyme activities in vivo. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 25285–25302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarazona, P.; Feussner, K.; Feussner, I. An enhanced plant lipidomics method based on multiplexed liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry reveals additional insights into cold- and drought-induced membrane remodeling. Plant J. 2015, 84, 621–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okazaki, Y.; Kamide, Y.; Hirai, M.Y.; Saito, K. Plant lipidomics based on hydrophilic interaction chromatography coupled to ion trap time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Metabolomics 2013, 9, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Y.; Liang, Y.; Shi, H.; Cui, J.; Prakash, S.; Zhang, J.; Anaokar, S.; Chai, J.; Schwender, J.; Lu, C. Creating yellow seed Camelina sativa with enhanced oil accumulation by CRISPR-mediated disruption of Transparent Testa 8. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2024, 22, 2773–2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.; Jiao, R.; Cheng, H.; Cai, S.; Liu, J.; Hu, Q.; Liu, L.; Li, B.; Wang, T.; Li, M.; et al. Targeted mutations of BnPAP2 lead to a yellow seed coat in Brassica napus L. J. Integr. Agric. 2020, 23, 724–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zewe, J.P.; Hammond, G.R.V. Click chemistry and optogenetic approaches to visualize and perturb phosphatidic acid signaling. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2022, 298, 101810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xie, S.; Zhao, Y.; Tao, M.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, Z.; Yang, B. Progress and Prospects of Research on the Role of Phosphatidic Acid in Response to Adverse Stress in Plants. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2758. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122758

Xie S, Zhao Y, Tao M, Zhang Y, Guo Z, Yang B. Progress and Prospects of Research on the Role of Phosphatidic Acid in Response to Adverse Stress in Plants. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2758. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122758

Chicago/Turabian StyleXie, Siqi, Yao Zhao, Menghuan Tao, Yarong Zhang, Zhenfei Guo, and Bo Yang. 2025. "Progress and Prospects of Research on the Role of Phosphatidic Acid in Response to Adverse Stress in Plants" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2758. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122758

APA StyleXie, S., Zhao, Y., Tao, M., Zhang, Y., Guo, Z., & Yang, B. (2025). Progress and Prospects of Research on the Role of Phosphatidic Acid in Response to Adverse Stress in Plants. Agronomy, 15(12), 2758. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122758