Soil Phosphorus Fraction Characteristics in Different Alpine Grassland Types of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

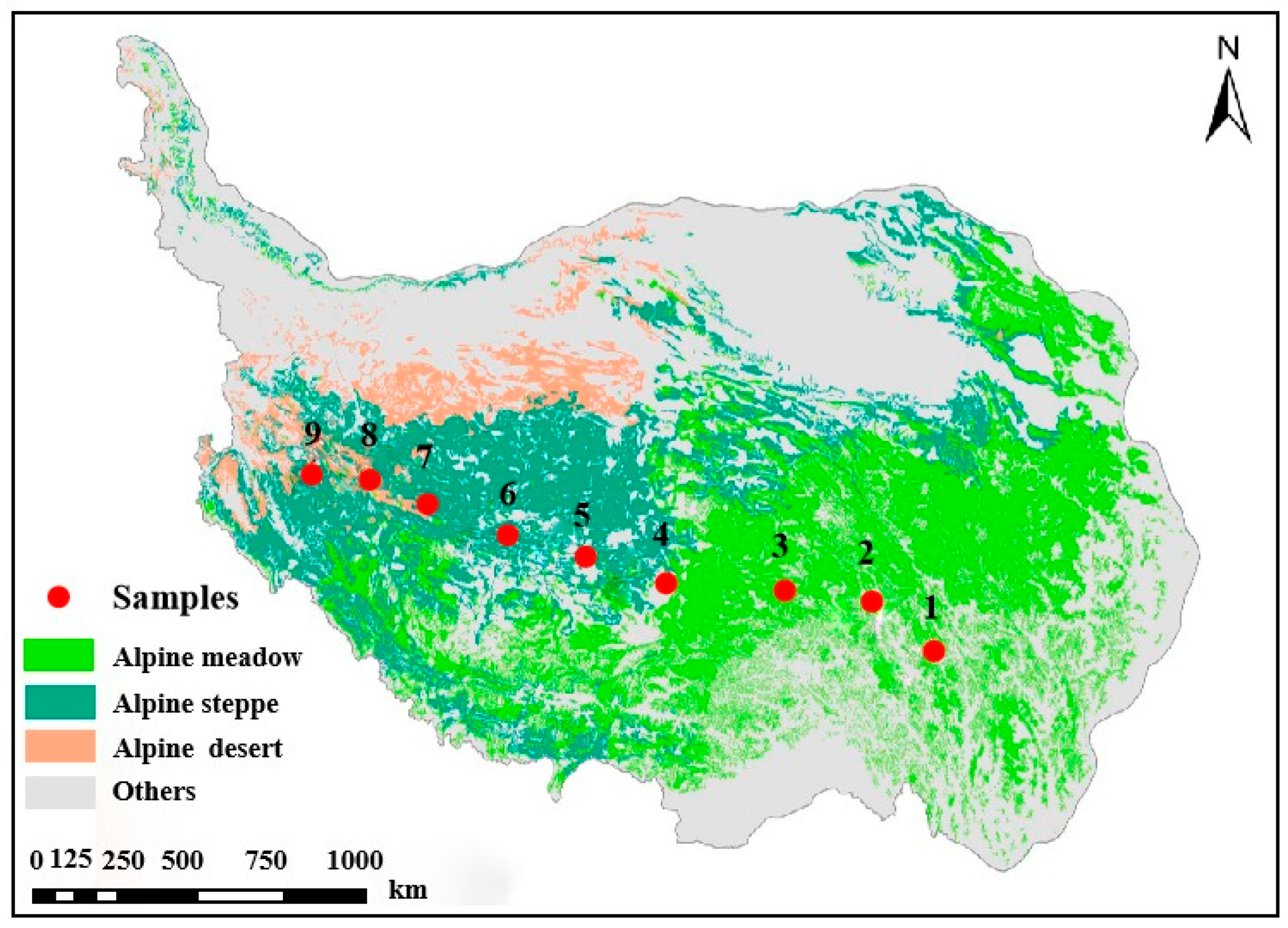

2.1. Study Sites and Sample Collection

2.2. Determination of Total P, Available P, and Inorganic and Organic P Concentrations in Soil Samples

2.3. Sequential Fractionation

2.4. Solution 31P NMR Spectroscopy

2.5. Determination of Phosphatase Activity

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

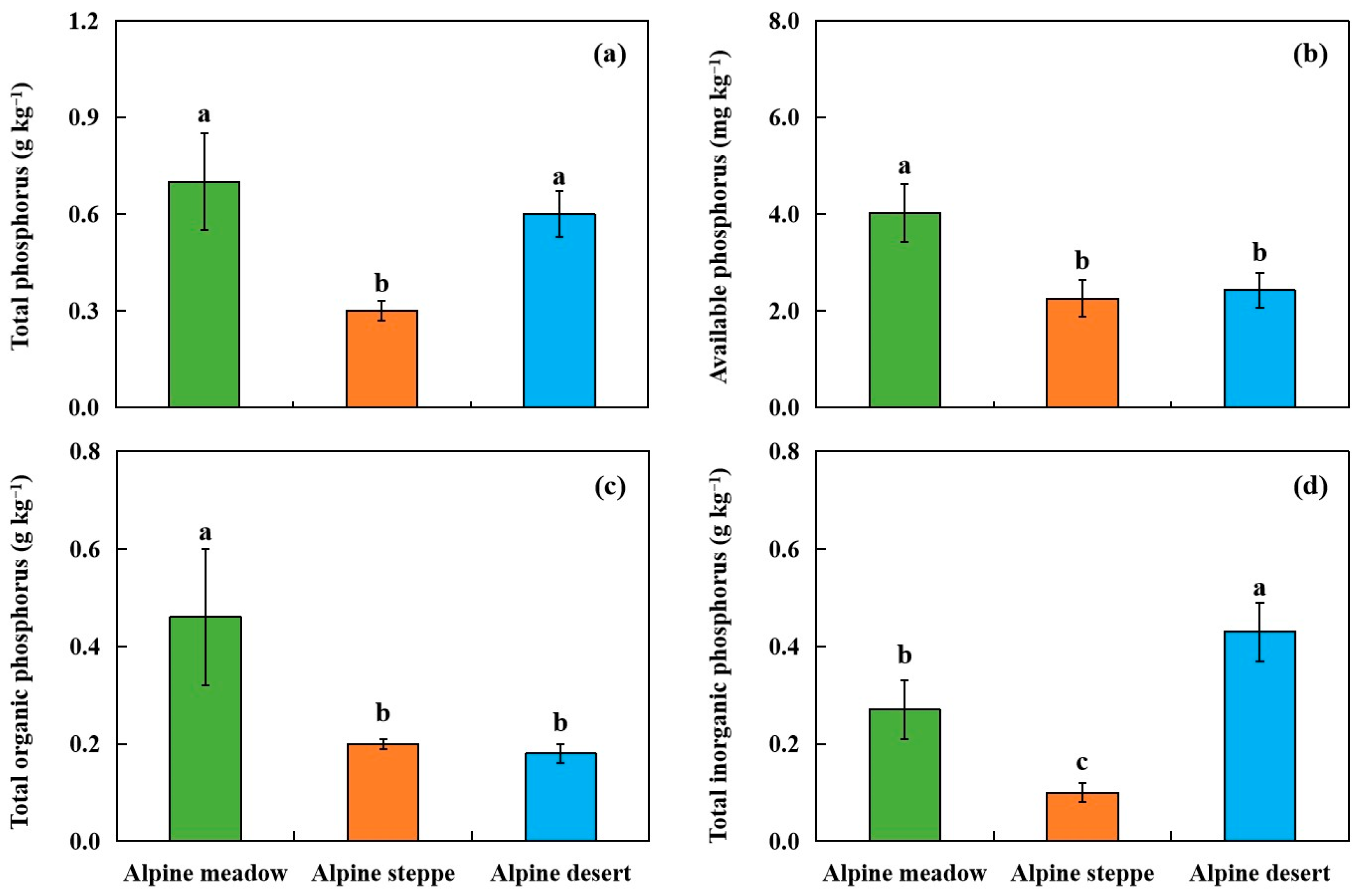

3.1. Total Soil P, Available P, and Po Concentrations in Soil Samples

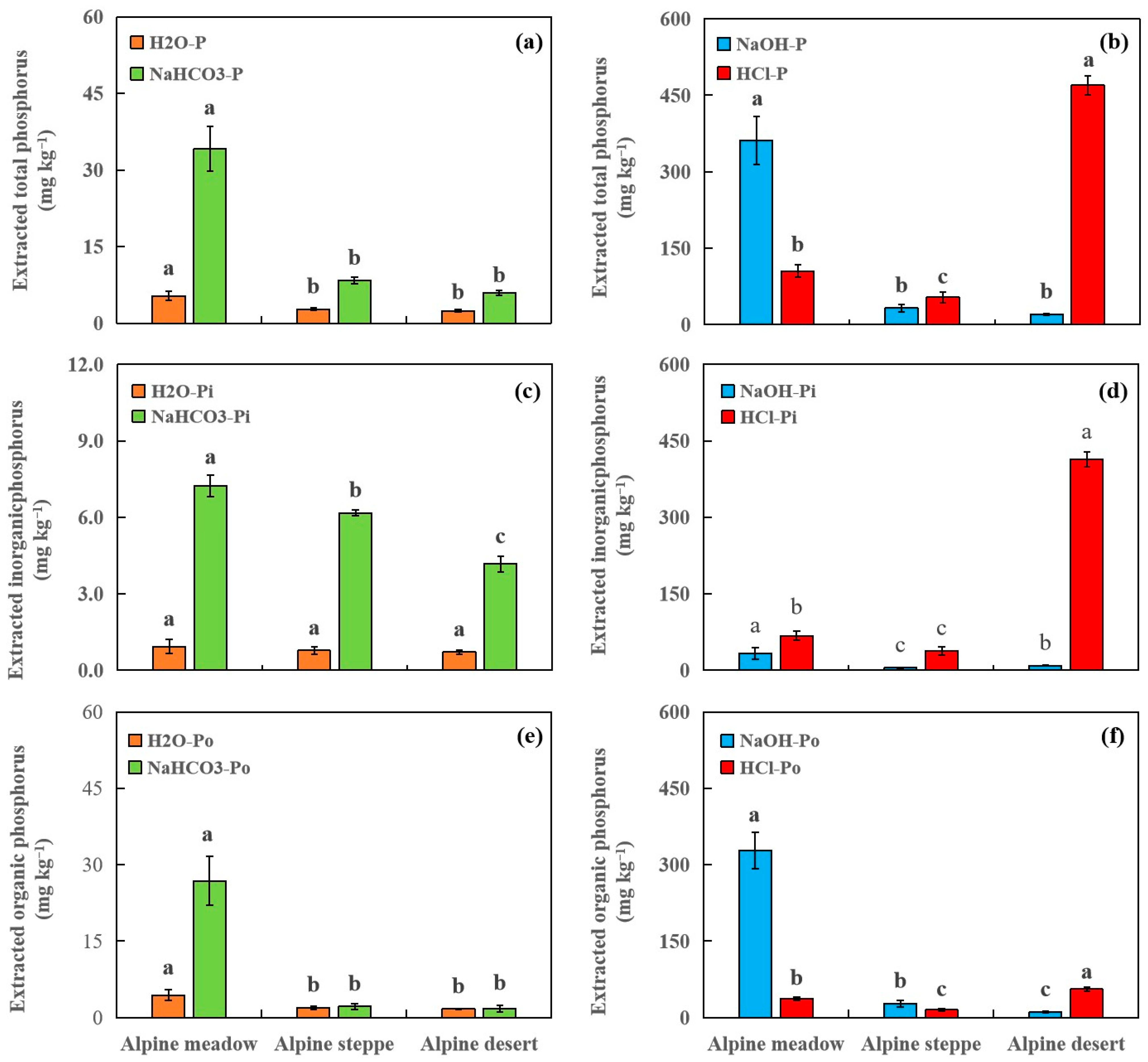

3.2. Soil P Forms Determined by Sequential Chemical Fractionation

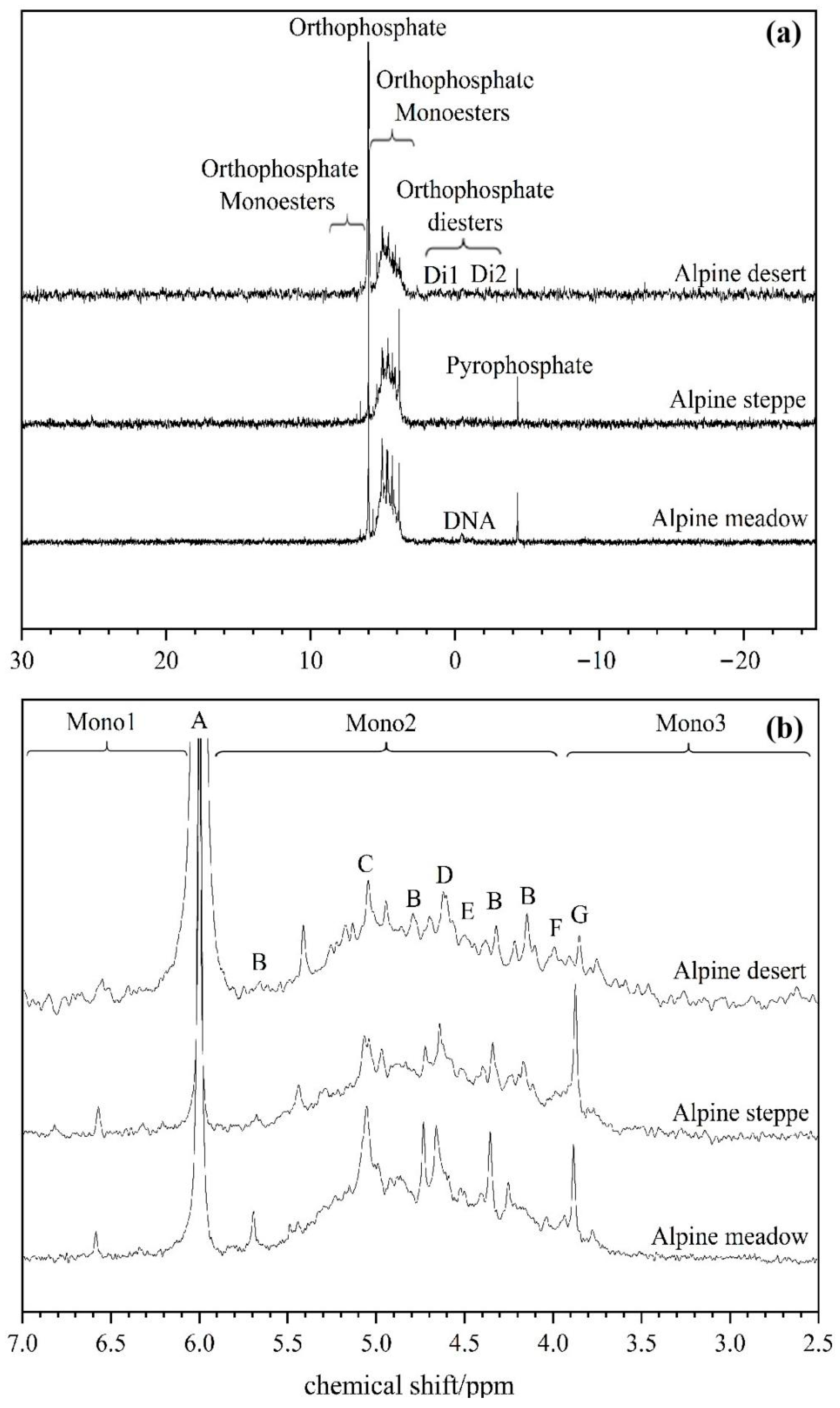

3.3. Soil P Forms Measured by 31P NMR Spectroscopy

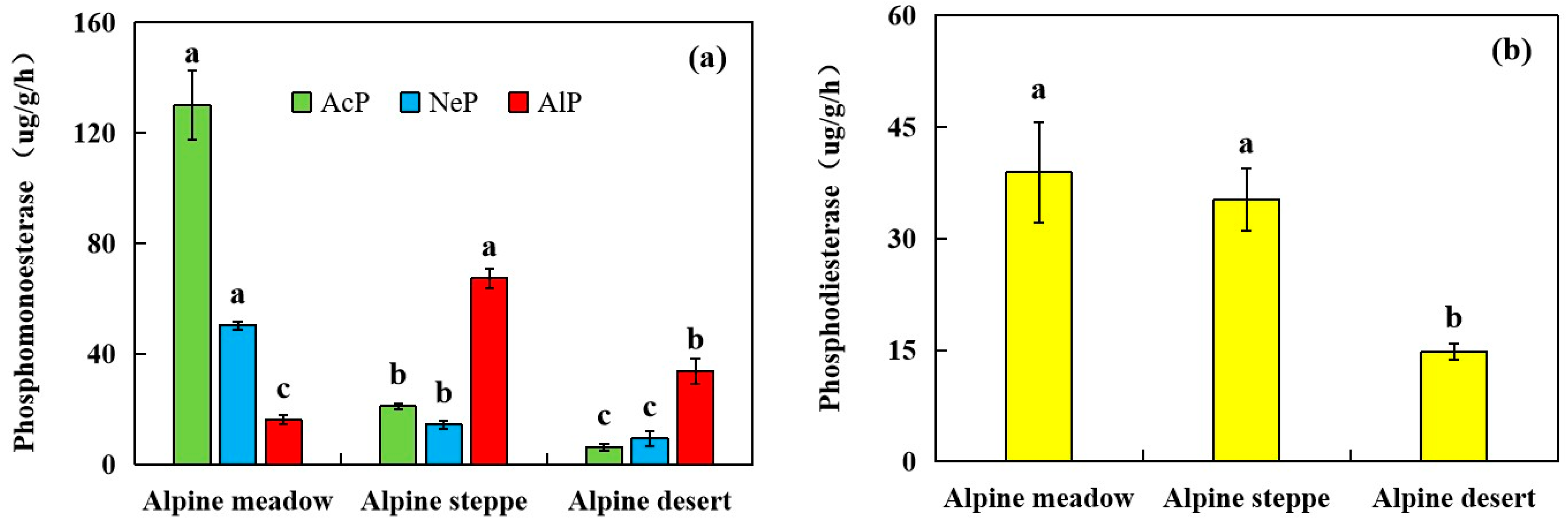

3.4. Phosphatase Activity

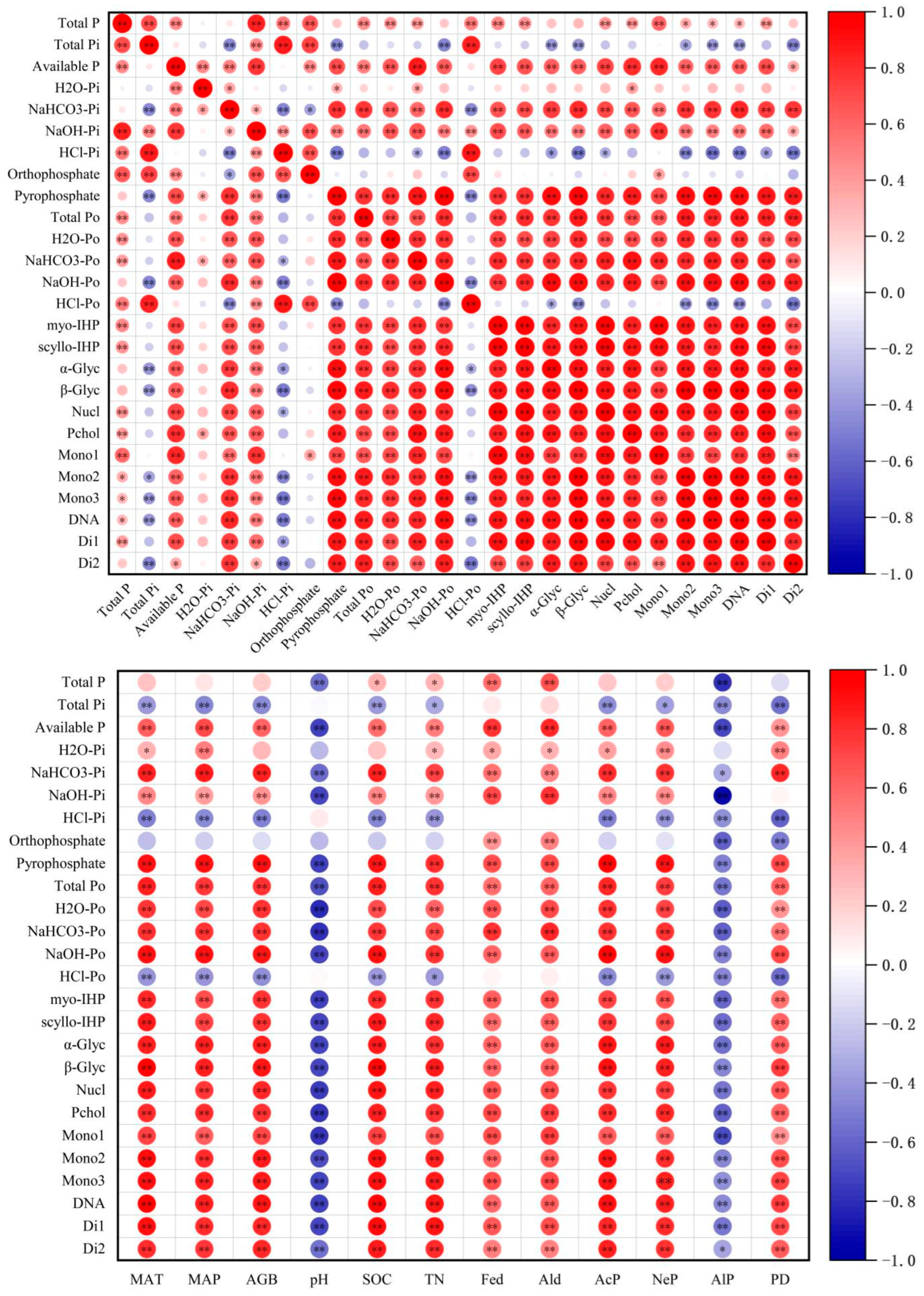

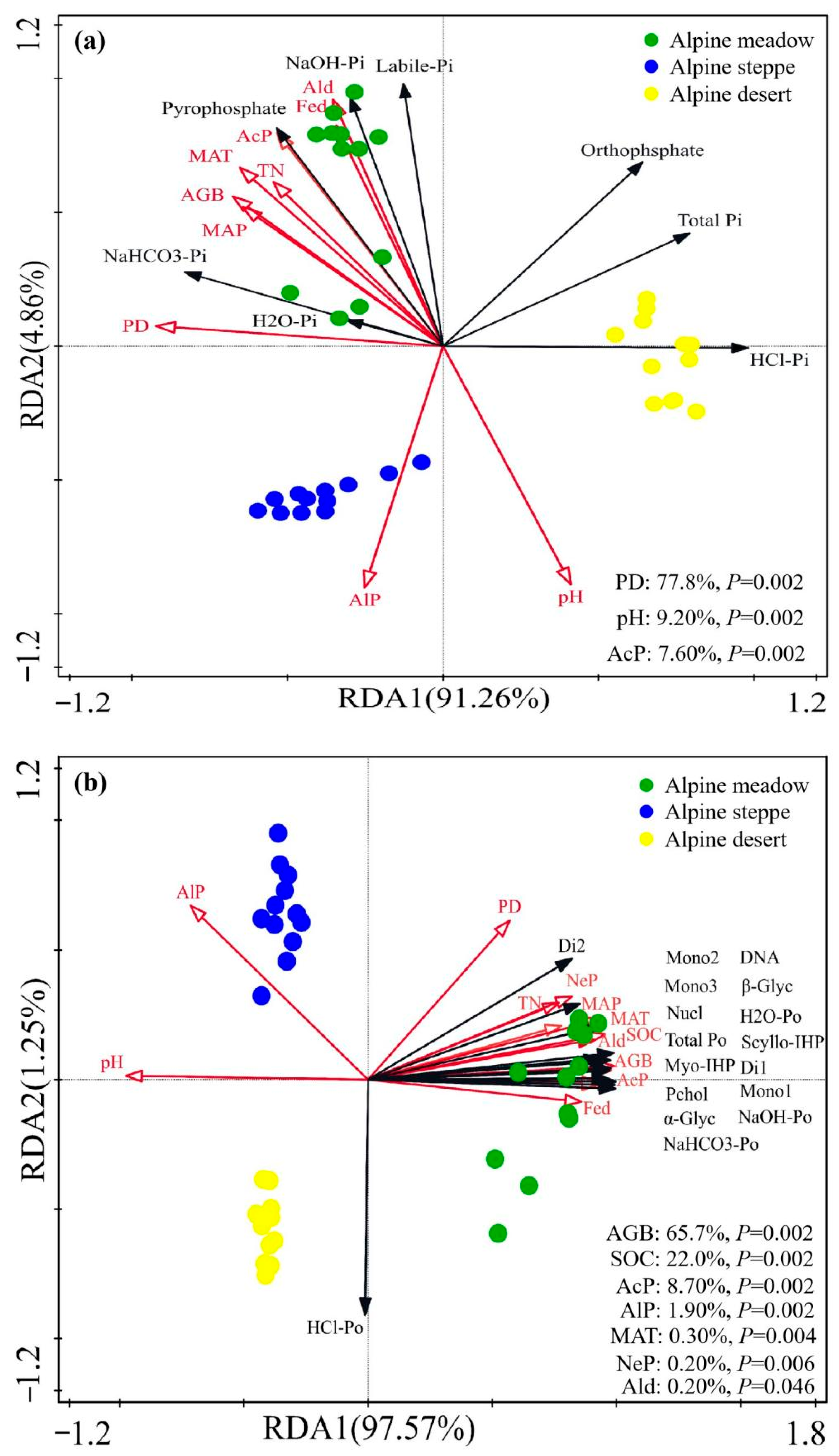

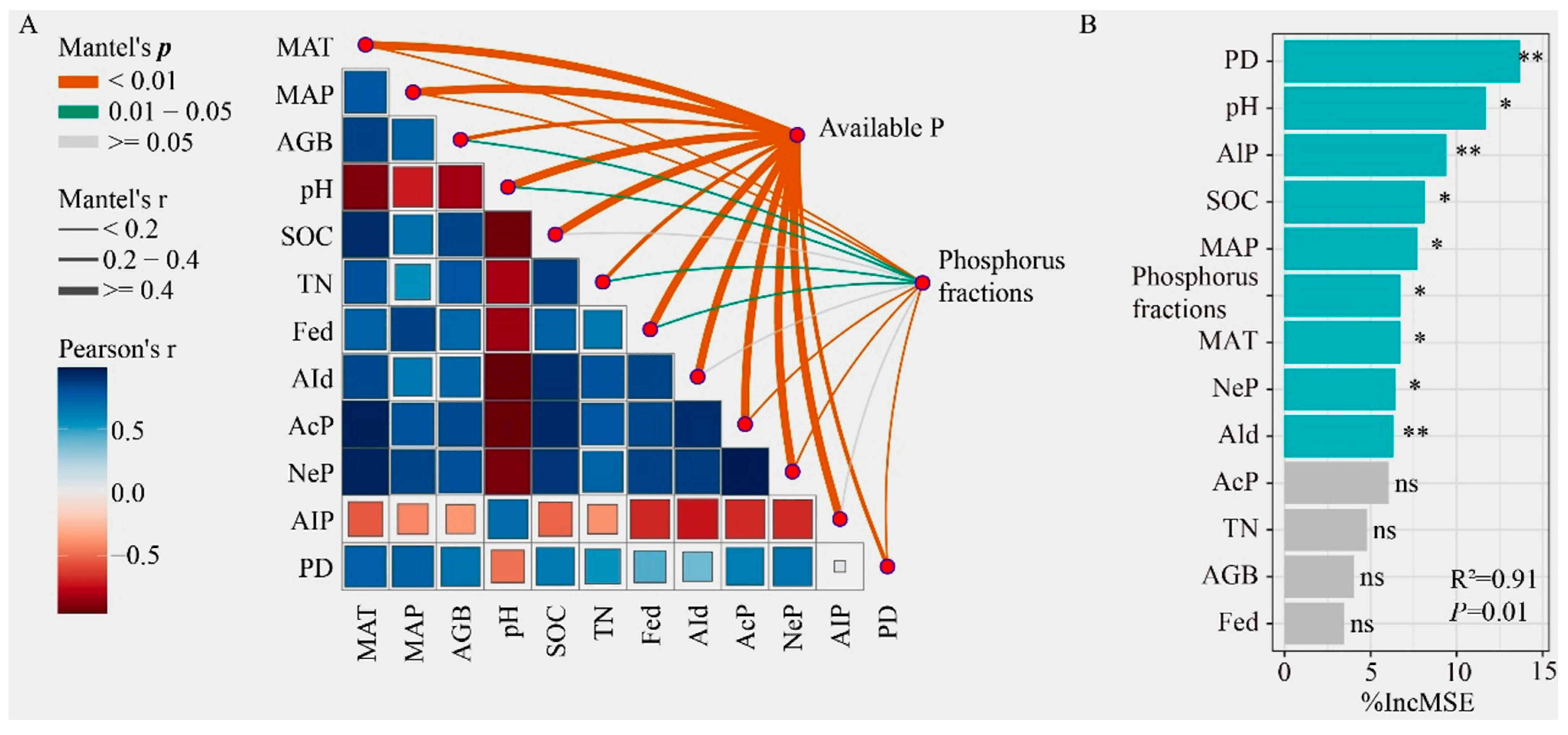

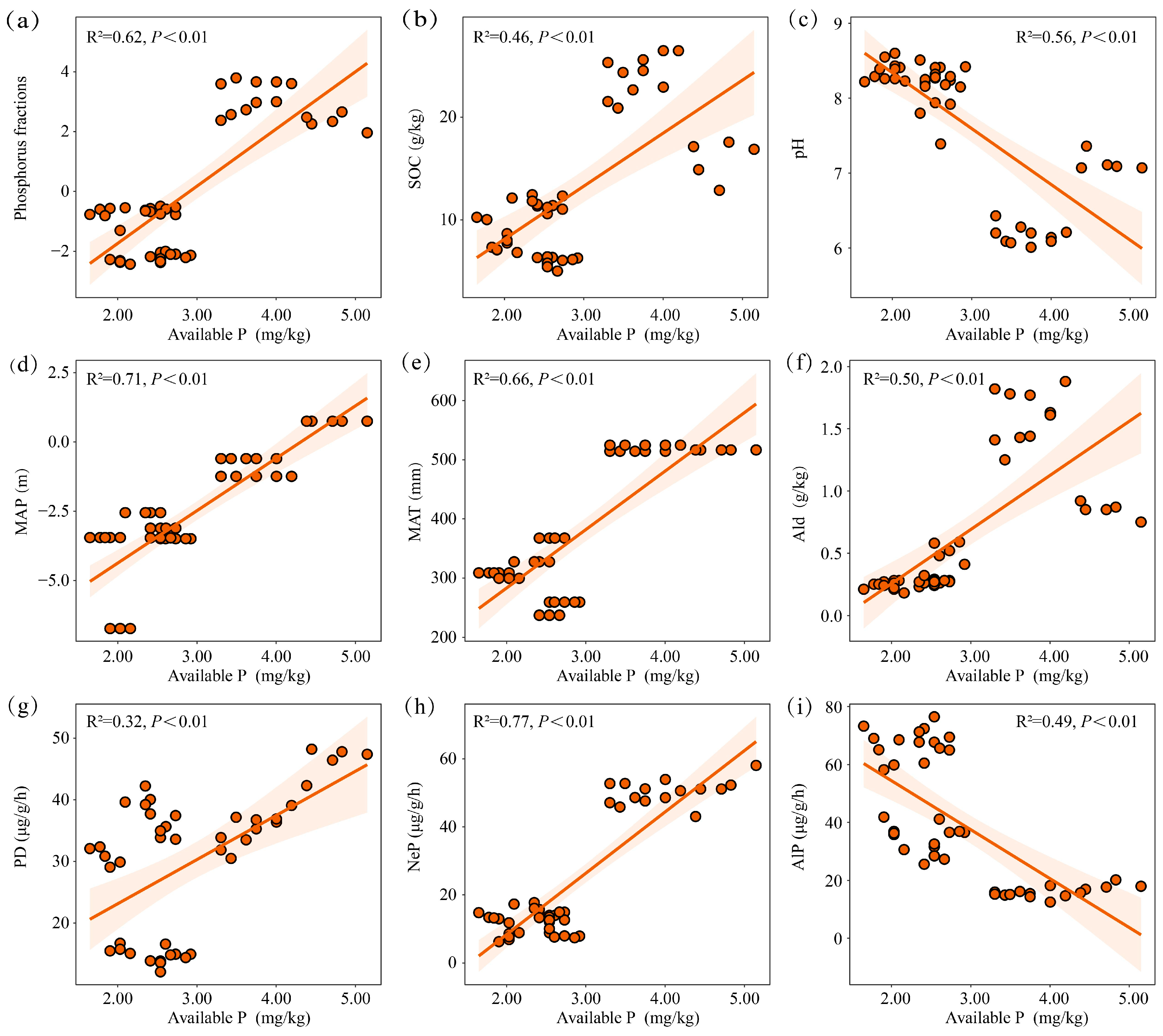

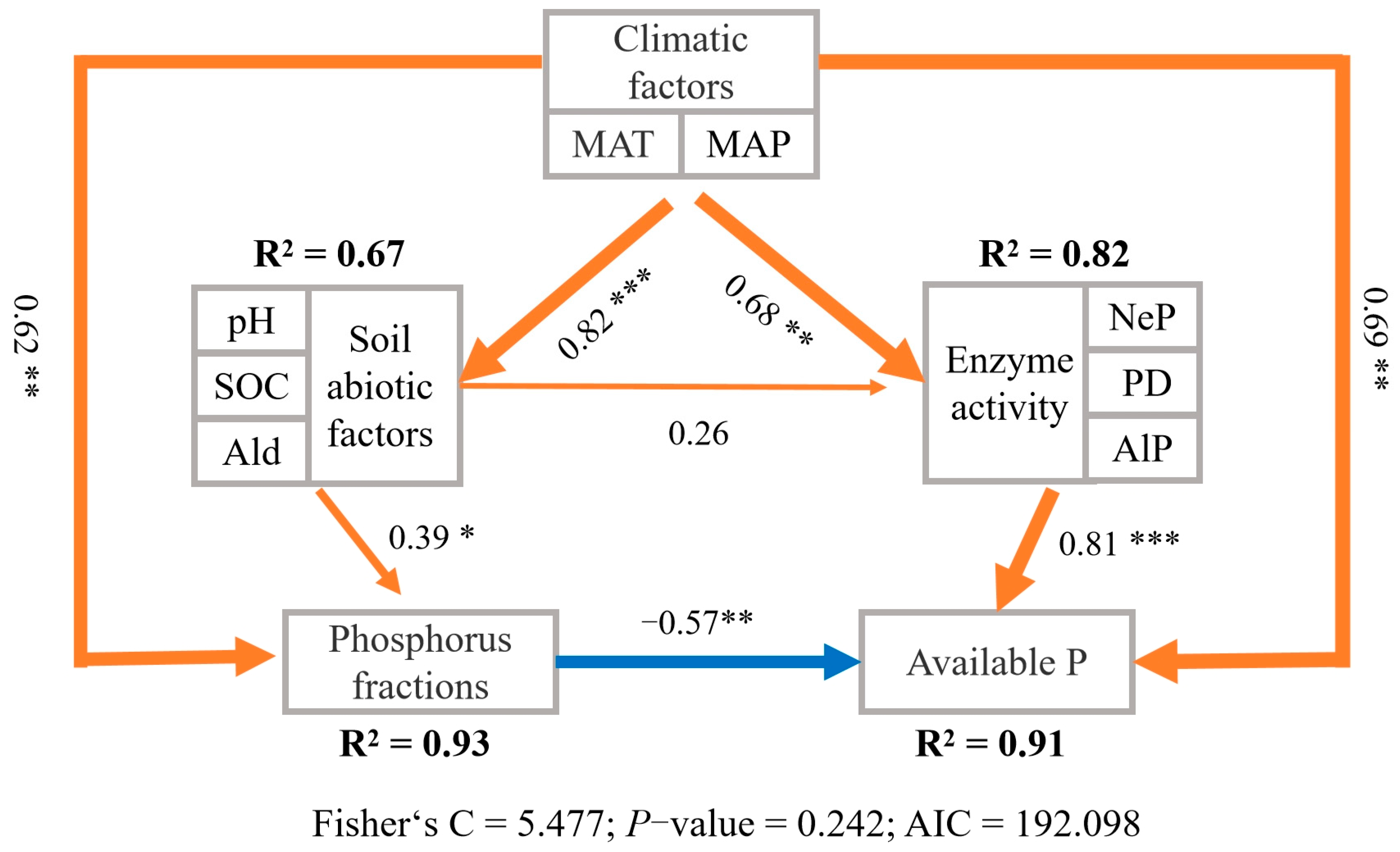

3.5. Relationship Between P Forms and Environmental Factors

4. Discussion

4.1. Spatial Variability of Soil Total P and Influencing Factors

4.2. Spatial Variability of Soil Pi Forms and Influencing Factors

4.3. Spatial Variability of Soil Po Forms and Influencing Factors

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhu, J.D.; Wu, A.; Zhou, G.Y. Spatial distribution patterns of soil total phosphorus influenced by climatic factors in China’s forest ecosystems. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 5357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.X.; Xu, D.H.; Yang, Y.T.; Huang, B.Y.; Fang, X.W.; Yao, G.Q.; Zhou, W.H.; Wu, Y.G. Response of Soil Phosphorus Fractions and Available Phosphorus to Phosphorus Plus Silicon Addition in Alpine Meadows. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2025, 25, 8075–8088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.T.; Luo, R.Y.; Liu, Q.H.; Qiang, W.; Liang, J.; Hou, E.Q.; Zhao, C.Z.; Pang, X.Y. Linking soil phosphorus fractions to abiotic factors and the microbial community during subalpine secondary succession: Implications for soil phosphorus availability. Catena 2023, 12, 107501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stutter, M.I.; Shand, C.A.; George, T.S.; Blackwell, M.; Haygarth, P.M. Recovering Phosphorus from Soil: A Root Solution? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 1977–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, D.G.; Wu, X.N.; Duan, C.Q.; Chadwick, D.R.; Jones, D.L. Response of soil phosphorus fractions and fluxes to different vegetation restoration types in a subtropical mountain ecosystem. Catena 2020, 193, 104663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.K.; Huang, B.C.; Liu, Z.Y.; Wang, Y.; Teng, J.; Tian, X.S.; Ai, X.Y.; Sheng, M.H.; Ai, Y.W. The distribution, effectiveness and environmental threshold of soil aggregate phosphorus fractions in the sub-alpine region of Southwest China. Land Degrad. Dev. 2023, 34, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.L.; Daryanto, S.; Xin, Z.M.; Liu, Z.M.; Liu, M.H.; Cui, X.; Wang, L.X. Soil phosphorus budget in global grasslands and implications for management. J. Arid Environ. 2017, 144, 224–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Yang, J.Y.; Guan, W.H.; Liu, Z.G.; He, G.X.; Zhang, D.G.; Liu, X.N. Soil fertility evaluation and spatial distribution of grasslands in Qilian Mountains Nature Reserve of eastern Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. PeerJ 2021, 23, e10986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Turner, B.L.; Lü, X.; Chen, Z.H.; Wei, K.; Tian, J.H.; Wang, C.; Luo, W.; Chen, L.J. Phosphorus transformations along a large-scale climosequence in arid and semiarid grasslands of northern China. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2016, 30, 1264–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.L.; Li, X.G.; Zhao, L.; Kuzyakov, Y. Regulation of soil phosphorus cycling in grasslands by shrubs. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2019, 133, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, J.J.; He, N.P. Soil organic carbon contents, aggregate stability, and humic acid composition in different alpine grasslands in Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. J. Mt. Sci. 2016, 13, 2015–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Qin, F.; Cui, Q.Y.; Li, Q.; Cui, Y.F.; Birks, H.J.B.; Liang, C.; Zhao, W.W.; Li, H.; Ren, W.H.; et al. Three-and-a-half million years of Tibetan Plateau vegetation dynamics in response to climate change. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2025, 9, 1153–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, C.Q.; Zhang, Y.J.; Holzapfel, C.; Zeng, R.; Zhang, X.Z.; Wang, J.S. Ecological and environmental issues faced by a developing Tibet. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 1979–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.J.; Zhang, Y.; Han, W.X.; Tang, A.H.; Shen, J.L.; Cui, Z.L.; Vitousek, P.; Erisman, J.W.; Goulding, K.; Christie, P.; et al. Enhanced nitrogen deposition over China. Nature 2013, 494, 459–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, B.; Zhang, D.Y.; Voigt, C.; Zhou, W.; Bai, Y.C.; Zheng, Z.H.; Xie, Y.H.; Zhao, C.B.; Wang, F.Q.; Huang, L.Y.; et al. Progressive decline in soil nitrogen stocks with warming in a Tibetan permafrost ecosystem. Nat. Geosci. 2025, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.D.; Wu, X.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Su, X.K.; Li, Y.Y.; Wang, X.X.; Liu, S.L.; Dong, S.K.; Tang, T. The relationship between soil physical properties and alpine plant diversity on Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Eurasian J. Soil Sci. 2015, 4, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fu, G.; Shen, Z.X. Response of alpine soils to nitrogen addition on the Tibetan Plateau: A meta-analysis. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2017, 114, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.M.; Zhao, L.; Wu, X.D.; Hu, G.J.; Fang, H.B.; Zhao, Y.H.; Sheng, Y.; Chen, J.; Wu, J.C.; Li, W.P.; et al. Variations in soil nutrient availability across Tibetan grassland from the 1980s to 2010s. Geoderma 2019, 338, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.T.; Pang, B.; Zhao, L.R.; Shu, S.M.; Feng, P.Y.; Liu, F.; Du, Z.Y.; Wang, X.D. Soil phosphorus crisis in the Tibetan alpine permafrost region. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 6204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, S.R.; Sommers, L.E. Phosphorus. In Methods of Soil Analysis. Part 2. Chemical and Microbiological Properties; Page, A.L., Miller, R.H., Keeney, D.R., Eds.; American Society of Agronomy: Madison, WI, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, S.R.; Cole, C.V.; Watanabe, F.S.; Dean, L.A. Estimation of Available Phosphorus in Soils by Extraction with Sodium Bicarbonate; US Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 1954.

- Walker, T.W.; Adams, A.F.R. Studies on Soil Organic Matter: I. Influence of phosphorus content of parent materials on accumulations of carbon, nitrogen, sulfur, and organic phosphorus in Grassland Soils. Soil Sci. 1958, 85, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achat, D.L.; Bakker, M.R.; Zeller, B.; Pellerin, S.; Bienaimé, S.; Morel, C. Long-term organic phosphorus mineralization in Spodosols under forests and its relation to carbon and nitrogen mineralization. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2010, 42, 1479–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, J.; Riley, J.P. A modified single solution method for the determination of phosphate in natural waters. Anal. Chim. Acta 1962, 27, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedley, M.J.; Stewart, J.W.B.; Chauhan, B.S. Changes in inorganic and organic soil phosphorus fractions induced by cultivation practices and by laboratory incubations. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1982, 46, 970–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiessen, H.; Moir, J.O. Characterization of available P by sequential extraction. In Soil Sampling and Methods of Analysis, 2nd ed.; Carter, M.R., Gregorich, E.G., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.Y.; Zhao, X.R.; Lin, Q.M.; Alamus; Wang, H.; Liu, H.L.; Wei, W.X.; Sun, X.C.; Li, Y.T.; Li, G.T. Distribution characteristics of soil organic phosphorus fractions in the Inner Mongolia steppe. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2020, 20, 2394–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, M.; Ahmed, W.; Ayyoub, A.; Elrys, A.S.; Mustafa, A.; Li, W.D.; Xu, Z.W. Impacts of land use change on soil carbon storage and phosphorus fractions in tropics. Catena 2024, 247, 108550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, K.; Chen, Z.H.; Zhu, A.N.; Zhang, J.B.; Chen, L.J. Application of 31P NMR spectroscopy in determining phosphatase activities and P composition in soil aggregates influenced by tillage and residue management practices. Soil Tillage Res. 2014, 138, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cade-Menun, B.; Barbara, J. Improved peak identification in 31P-NMR spectra of environmental samples with a standardized method and peak library. Geoderma 2015, 257–258, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.J.; Sun, Y.H.; Tang, J.Y.; Li, C.L.; Zhu, M.; Zhu, P. Influences of Long-Term Fertilization on Phosphorus Forms and Availability Within Particle-Size Fractions in a Mollisol. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2024, 25, 6740–6755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yang, J.J.; Cade-Menun, B.J.; Liang, X.Q.; Hu, Y.F.; Liu, C.W.; Zhao, Y.; Li, L.; Shi, J.Y. Complementary phosphorus speciation in agricultural soils by sequential fractionation, solution 31P nuclear magnetic resonance, and phosphorus K-edge X-ray absorption near-edge structure spectroscopy. J. Environ. Qual. 2013, 42, 1763–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doolette, A.L.; Smernik, R.J.; Dougherty, W.J. Spiking Improved solution phosphorus-31 Nuclear magnetic resonance identification of soil phosphorus compounds. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2009, 73, 919–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcdowell, R.W.; Cade-Menun, B.; Stewart, I. Organic phosphorus speciation and pedogenesis: Analysis by solution 31P nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2007, 58, 1348–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.J.; Sun, Y.H.; Cao, Z.Y.; Li, C.L.; Zhu, M.; Zhu, P. Long-term fertilization impacts on soil phosphorus forms using XANES and NMR spectroscopy. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2023, 69, 1266–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabatabai, M. Methods of Soil Analysis, Part 2—Microbiological and Biochemical Properties; Soil Enzymes; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1994; pp. 775–833. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.J.; Augusto, L.; Goll, D.S.; Ringeval, B.; Wang, Y.P.; Helfenstein, J.L.; Huang, Y.Y.; Yu, K.L.; Wang, Z.Q.; Yang, Y.C.; et al. Global patterns and drivers of soil total phosphorus concentration. Earth Syst. Sci. 2021, 13, 5831–5846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.B.; Wu, Y.H.; Zhu, H.; Zhou, J.; Luo, C.Y.; Bing, H.J. Soil phosphorus fractions dynamics along a 22-ka chronosequence of landslides, western Sichuan, China. Catena 2024, 235, 107674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.Y.; Wu, Y.T.; Guo, L.L.; Yang, L.; Wang, B.; Wang, X.; Liu, W.X.; Su, Y.J.; Wu, J.; Liu, L.L. Foliar nutrient resorption stoichiometry and microbial phosphatase catalytic efficiency together alleviate the relative phosphorus limitation in forest ecosystems. New Phytol. 2023, 238, 1033–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.X.; Guo, M.M.; Liu, X.; Wang, L.X.; Chen, Q.; Qi, J.R.; Shen, Q.S.; Zhang, X.Y. Gully transforms the loss pattern of runoff, sediment, nitrogen, and phosphorus in agricultural catchment of Northeast China. J. Hydrol. 2025, 660, 133503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutor, F.W.; Roy, E.D.; Schroth, A.W.; Michaud, A.B.; Emerson, D.; Herndon, E.M.; Kinsman-Costello, L.; Hurley, S.E.; Bowden, W.B. Geochemical phosphorus sequestration in tundra soils impedes delivery of bioavailable phosphorus to the Kuparuk River, Alaska, USA: Implications for the broader Arctic region. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2025, 130, e2025JG008803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, A.E.; George, T.S.; Hens, M.; Delhaize, E.; Ryan, P.R.; Simpson, R.J.; Hocking, P.J. Organic anions facilitate the mobilization of soil organic phosphorus and its subsequent lability to phosphatases. Plant Soil 2022, 476, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, B.A.; Kopittke, P.M.; Bell, M.J.; Lombi, E.; Klysubun, W.; McLaren, T.I.; Doolette, C.L.; Meyer, G. Phosphorus availability and speciation in the fertosphere of three soils over 12 months. Geoderma 2024, 447, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.X.; Wang, C.Y.; Li, C.L.; Li, J.Y.; Xu, L.; Zhang, J.Y.; Zhang, J.J.; He, N.P. The distribution and influencing factors of soil phosphorus in different types of grasslands on the Qinghai Tibet Plateau in Chinese. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2022, 5, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, X.Z.; Guo, C.H.; He, X.J.; Helfenstein, J.L.; Lambers, H.; Ren, Q.Q.; Ibrahim, M.M.; Li, Z.M.; Lin, H.Y.; Chang, Z.F.; et al. Global Distribution and Influencing Factors of Plant-Available Phosphorus in (Semi-)Natural Soils. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2025, 39, e2025GB008513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Bing, H.J.; Wu, Y.H.; Yang, Z.J.; Wang, J.P.; Sun, H.Y.; Luo, J.; Liang, J.H. Rapid weathering processes of a 120-year-old chronosequence in the Hailuogou Glacier foreland, Mt. Gongga, SW China. Geoderma 2016, 267, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.H.; Zhou, J.; Bing, H.J.; Sun, H.Y.; Wang, J.P. Rapid loss of phosphorus during early pedogenesis along a glacier retreat choronosequence, Gongga Mountain (SW China). PeerJ 2015, 3, e1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.M.; Zhang, C.C.; Pan, G.X.; Zhang, X.H. Availability of soil nitrogen and phosphorus under elevated [CO2] and temperature in the Taihu Lake region, China. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2014, 177, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.Y.; He, M.Z.; Xin, C.M.; Zhang, Z.H. Phosphorus sorption-desorption changes phosphorus fraction dynamic in a desert revegetation chronosequence. Land Degrad. Dev. 2024, 35, 3422–3433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, A.N.; Cleveland, C.C. The effects of temperature on soil phosphorus availability and phosphatase enzyme activities: A cross-ecosystem study from the tropics to the Arctic. Biogeochemistry 2020, 151, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.Y.; Wu, Y.H.; Bing, H.J.; Luo, C.Y.; Zhu, H.; He, J.B. Microorganisms Promote Soil Phosphorus Bioavailability at the Beginning of Pedogenesis. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2025, 31, e70419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.C.; Ren, C.Q.; Cheng, H.T.; Zou, Y.K.; Bughio, M.A.; Li, Q.F. Conversion of rainforest into agroforestry and monoculture plantation in China: Consequences for soil phosphorus forms and microbial community. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 595, 769–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.Y.; Chen, X.W.; Guo, E.; Yang, X.T. Path analysis of phosphorus activation capacity as induced by low-molecular-weight organic acids in a black soil of Northeast China. J. Soils Sediments 2019, 19, 840–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.L.; Xu, C.Z. Citric acid enhances the mobilization of organic phosphorus in subtropical and tropical forest soils. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2010, 46, 765–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Zhao, Y.H.; Wang, W.K.; He, Y.H. Elevated temperature altered photosynthetic products in wheat seedlings and organic compounds and biological activity in rhizopshere soil under cadmium stress. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 14426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penn, C.J.; Camberato, J.J. A critical review on soil chemical processes that control how soil pH affects phosphorus availability to plants. Agriculture 2019, 9, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Wu, Y.H.; Prietzel, J.; Bing, H.J.; Yu, D.; Sun, S.Q.; Luo, J.; Sun, H.Y. Changes of soil phosphorus speciation along a 120-year soil chronosequence in the Hailuogou Glacier retreat area (Gongga Mountain, SW China). Geoderma 2013, 195, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.L.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, J.J.; Zhu, P.; Wang, L.C. Forms, transformations and availability of phosphorus after 32 years of manure and mineral fertilization in a Mollisol under continuous maize cropping. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2021, 67, 1256–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrow, N.J.; Hartemink, A.E.E. The effects of pH on nutrient availability depend on both soils and plants. Plant Soil 2023, 487, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.Y.; Huang, Y.J.; Li, Y.G.; Han, Z.L.; Zhang, S.J.; Zhang, Q.; Ma, X.X.; Jing, C.Q.; Gao, Y.Z.; Zhou, X.B.; et al. Patch size indirectly influences the distribution characteristics of phosphorus fractions in temperate desert moss crust soils. Catena 2025, 251, 108821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, E.E.A.Z. Chemical Properties of Some Alkaline Sandy Soils and Their Effects on Phosphorus Dynamics with Bone Char Application as a Renewable Resource of Phosphate Fertilizer. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2023, 23, 1589–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, A.G.; Sundqvist, M.K.; Wardle, D.A.; Giesler, R. Bioavailable soil phosphorus decreases with increasing elevation in a subarctic tundra landscape. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e92942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, X.B.; Liu, D.W.; Wu, H.H.; Lü, X.; Fang, Y.T.; Cheng, W.; Luo, W.; Jiang, P.; Shi, J.; et al. Aridity threshold in controlling ecosystem nitrogen cycling in arid and semi-arid grasslands. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Maestre, F.T.; Gallardo, A.; Bowker, M.A.; Wallenstein, M.D.; Quero, J.L.; Ochoa, V.; Gozalo, B. Decoupling of soil nutrient cycles as a function of aridity in global drylands. Nature 2013, 502, 672–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Zeng, D.; Fan, Z.; Yu, Z.Y.; Hu, Y.L.; Zhang, J.W. Seasonal variations in phosphorus fractions in semiarid sandy soils under different vegetation types. For. Ecol. Manag. 2009, 258, 1376–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.L.; Zhou, J.; Wu, Y.H.; Bing, H.J.; Sun, H.Y.; Wang, J.P. Leaching disturbed the altitudinal distribution of soil organic phosphorus in subalpine coniferous forests on Mt. Gongga, SW China. Geoderma 2018, 326, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, Y.C.; Wang, Y.F.; Chen, C.R.; Zhou, X.Q.; Wang, S.P.; Xu, Z.H.; Duan, J.C.; Kang, X.M.; Lu, S.B.; Luo, C.Y. Warming and grazing increase mineralization of organic P in an alpine meadow ecosystem of Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, China. Plant Soil 2012, 357, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.Y.; Xu, L.; Zong, N.; Zhang, J.J.; He, N.P. Impacts of climate warming on soil phosphorus forms and transformation in a Tibetan Alpine Meadow. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2022, 22, 2545–2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.; Ranjha, R.; Sharma, S.K.; Kaistha, P.; Parmar, V. Soil Phosphorus Fractions and Balance in Response to Integrated Phosphorus Management in an Acid Alfisol of North West Himalayas. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2025, 25, 5272–5282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.H.; Wei, K.; Condron, L.; Chen, Z.H.; Xu, Z.W.; Chen, L.J. Impact of land use and nutrient addition on phosphatase activities and their relationships with organic phosphorus turnover in semi-arid grassland soils. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2016, 52, 675–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, E.G.; Chen, C.G.; Luo, Y.Q.; Zhou, G.Y.; Kuang, Y.W.; Zhang, Y.G.; Heenan, M.; Lu, X.K.; Wen, D.Z. Effects of climate on soil phosphorus cycle and availability in natural terrestrial ecosystems. Glob. Change Biol. 2018, 24, 3344–3356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, B.L.; Engelbrecht, B.M.J. Soil organic phosphorus in lowland tropical rain forests. Biogeochemistry 2011, 103, 297–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, X.L.; Zhang, X.F.; Chu, W.Y.; Mao, J.D.; Yang, W.L.; Zhu, A.N.; Zhang, J.B.; Zhong, X.Y. Characterization of fluvo-aquic soil phosphorus affected by long-term fertilization using solution 31P NMR spectroscopy. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 692, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, D.S.; Menezes-Blackburn, D.; Turner, B.L.; Wearing, C.; Haygarth, P.M.; Rosolem, C.A. Urochloa ruziziensis cover crop increases the cycling of soil inositol phosphates. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2018, 54, 935–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Sui, P.; Cade-Menun, B.J.; Hu, Y.F.; Yang, J.J.; Huang, S.M.; Ma, Y.B. Molecular-level understanding of phosphorus transformation with long-term phosphorus addition and depletion in an alkaline soil. Geoderma 2019, 353, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Longitude | Latitude | Elevation (m) | MAP (mm) | MAT (°C) | Soil Type | Soil Texture | Grassland Type | Dominant Plant Species | AGB (g m−2) | pH | SOC (g kg−1) | TN (g kg−1) | Fed (g kg−1) | Ald (g kg−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 97°12′ | 30°24′ | 4207 | 516.6 | 0.75 | Subalpine meadow soil | Sand loam | Alpine meadow | K. pygmaea, K. humilis | 115.7 ± 39.5 | 7.15 ± 0.14 | 16.61 ± 1.18 | 1.47 ± 0.27 | 4.35 ± 0.09 | 0.85 ± 0.07 |

| 2 | 96°26′ | 31°24′ | 3931 | 514.4 | −0.60 | Subalpine meadow soil | Sand loam | Alpine meadow | K. pygmaea, K. humilis | 177.7 ± 44.5 | 6.16 ± 0.05 | 22.46 ± 1.62 | 2.43 ± 0.63 | 4.54 ± 0.06 | 1.43 ± 0.16 |

| 3 | 95°36′ | 31°36′ | 4618 | 524.7 | −1.24 | Subalpine meadow soil | Sand loam | Alpine meadow | K. pygmaea, K. humilis | 129.1 ± 44.9 | 6.20 ± 0.17 | 25.65 ± 1.02 | 2.59 ± 0.51 | 4.39 ± 0.11 | 1.77 ± 0.12 |

| 4 | 89°42′ | 31°32′ | 4578 | 367.5 | −3.11 | Alpine steppe soil | Sand loam | Alpine steppe | S. purpurea, S. pinnate | 86.2 ± 22.4 | 8.25 ± 0.04 | 11.33 ± 0.73 | 1.32 ± 0.17 | 3.34 ± 0.08 | 0.26 ± 0.02 |

| 5 | 87°50′ | 31°52′ | 4527 | 327.4 | −2.55 | Alpine steppe soil | Sand loam | Alpine steppe | S. purpurea, S. pinnate | 75.4 ± 43.4 | 8.36 ± 0.12 | 11.83 ± 0.56 | 1.67 ± 0.28 | 3.72 ± 0.11 | 0.27 ± 0.03 |

| 6 | 85°50′ | 31°55′ | 4907 | 308.7 | −3.45 | Alpine steppe soil | Sand loam | Alpine steppe | S. purpurea, S. pinnate | 64.1 ± 56.5 | 8.34 ± 0.17 | 8.78 ± 1.60 | 1.08 ± 0.15 | 3.47 ± 0.12 | 0.25 ± 0.03 |

| 7 | 83°20′ | 32°24′ | 4517 | 259.2 | −3.49 | Alpine desert soil | Sand | Alpine desert | S. glareosa, O. thoroldii | 31.8 ± 17.5 | 8.23 ± 0.23 | 6.12 ± 0.29 | 1.06 ± 0.10 | 3.96 ± 0.09 | 0.52 ± 0.09 |

| 8 | 82°36′ | 32°30′ | 4370 | 299.5 | −6.72 | Alpine desert soil | Sand | Alpine desert | S. glareosa, O. thoroldii | 24.2 ± 10.0 | 8.38 ± 0.13 | 7.66 ± 0.84 | 1.15 ± 0.15 | 3.11 ± 0.07 | 0.22 ± 0.04 |

| 9 | 81°14′ | 32°17′ | 4527 | 237.3 | −3.46 | Alpine desert soil | Sand | Alpine desert | S. glareosa, O. thoroldii | 30.2 ± 18.7 | 8.26 ± 0.11 | 5.80 ± 0.68 | 0.56 ± 0.03 | 3.67 ± 0.12 | 0.28 ± 0.03 |

| Treatment | EPt | Pi | Po | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ortho | Pyro | Monoesters | Diesters | ||||||||||||

| myo-IHP | scyllo-IHP | α-Glyc | β-Glyc | Nucl | Pchol | Mono1 | Mono2 | Mono3 | DNA | Di1 | Di2 | ||||

| Proportions (%) | |||||||||||||||

| Alpine meadow | 57.4 ± 4.33 a | 16.3 ± 2.88 b | 1.69 ± 0.26 a | 19.53 ± 2.22 a | 4.56 ± 0.43 a | 11.4 ± 1.55 a | 8.61 ± 0.85 a | 2.67 ± 0.24 b | 4.16 ± 0.19 a | 2.34 ± 0.24 a | 18.6 ± 1.23 b | 3.78 ± 0.89 b | 1.74 ± 0.16 a | 2.88 ± 0.40 a | 1.01 ± 0.08 b |

| Alpine steppe | 39.1 ± 9.76 b | 14.1 ± 0.57 b | 1.43 ± 0.07 a | 12.97 ± 1.75 b | 3.62 ± 0.57 a | 3.23 ± 0.11 b | 5.53 ± 0.14 b | 4.40 ± 0.97 a | 3.43 ± 0.99 a | 1.55 ± 0.77 a b | 36.2 ± 3.54 a | 7.44 ± 0.90 a | 1.62 ± 0.12 a | 2.64 ± 0.43 a | 2.46 ± 0.56 a |

| Alpine desert | 25.7 ± 3.42 c | 42.2 ± 7.83 a | 0.58 ± 0.13 b | 7.79 ± 1.98 c | 2.30 ± 0.68 b | 1.97 ± 0.52 b | 2.24 ± 0.39 c | 2.58 ± 0.88 b | 2.17 ± 0.24 b | 1.19 ± 0.26 b | 20.1 ± 3.14 b | 3.38 ± 0.17 b | 0.64 ± 0.13 b | 1.55 ± 0.23 b | 0.69 ± 0.18 b |

| Contents (mg kg–1) | |||||||||||||||

| Alpine meadow | 421.2 ± 100.2 a | 80.8 ± 18.7 a | 6.95 ± 0.82 a | 83.4 ± 26.6 a | 19.4 ± 5.88 a | 47.0 ± 6.34 a | 36.8 ± 11.7 a | 11.4 ± 3.34 a | 17.7 ± 4.88 a | 9.97 ± 3.02 a | 78.3 ± 18.8 a | 16.3 ± 6.78 a | 7.25 ± 1.39 a | 12.4 ± 4.35 a | 4.29 ± 1.29 a |

| Alpine steppe | 116.1 ± 17.1 b | 16.4 ± 2.39 b | 1.65 ± 0.20 b | 15.3 ± 4.37 b | 4.27 ± 1.30 b | 3.74 ± 0.45 b | 6.44 ± 1.08 b | 5.19 ± 1.67 b | 4.05 ± 1.51 b | 1.89 ± 1.21 b | 41.6 ± 2.67 b | 8.54 ± 0.58 a b | 1.89 ± 0.35 b | 3.06 ± 0.60 b | 2.79 ± 0.28 a |

| Alpine desert | 154.0 ± 20.7 b | 66.8 ± 5.86 a | 0.88 ± 0.20 b | 12.0 ± 3.05 b | 3.48 ± 0.74 b | 2.96 ± 0.46 b | 3.41 ± 0.36 b | 3.97 ± 1.41 b | 3.32 ± 0.14 b | 1.86 ± 0.62 b | 30.7 ± 4.18 c | 5.21 ± 0.85 b | 0.98 ± 0.14 b | 2.36 ± 0.25 b | 1.04 ± 0.16 b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, X.; Liu, Z.; Li, C.; Zong, N.; He, N.; Cao, Z.; Zhang, J. Soil Phosphorus Fraction Characteristics in Different Alpine Grassland Types of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2689. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122689

Li X, Liu Z, Li C, Zong N, He N, Cao Z, Zhang J. Soil Phosphorus Fraction Characteristics in Different Alpine Grassland Types of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2689. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122689

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Xueting, Zhan Liu, Cuilan Li, Ning Zong, Nianpeng He, Zhiyuan Cao, and Jinjing Zhang. 2025. "Soil Phosphorus Fraction Characteristics in Different Alpine Grassland Types of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2689. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122689

APA StyleLi, X., Liu, Z., Li, C., Zong, N., He, N., Cao, Z., & Zhang, J. (2025). Soil Phosphorus Fraction Characteristics in Different Alpine Grassland Types of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau. Agronomy, 15(12), 2689. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122689