Abstract

Recycling agricultural residues is a promising strategy to enhance soil organic carbon (SOC) and improve soil quality. This study investigated the effects of exogenous organic carbon (EOC) amendments—straw and hydrochar—on SOC, its labile fractions, and the carbon pool management index (CPMI, an indicator of soil carbon quality and management efficiency) under flooding (FI) and controlled irrigation (CI) in a two-year pot experiment using paddy soil under field conditions. CI improved the soil average readily oxidizable organic carbon (ROC), dissolved organic carbon (DOC), and microbial biomass carbon (MBC) by 6.37–12.19%, 18.70–26.00% (p < 0.05), and 11.95–17.97% (p < 0.05), compared to FI. Similarly, EOC addition increased average ROC, DOC, and MBC during the entire rice growth period by 12.33–22.95%, 4.50–24.35%, and 6.24–21.51%, respectively, compared to the unamended controls. Additionally, CI increased soil carbon lability (L), carbon pool activity index (LI), carbon pool index (CPI), and CPMI by 3.39–14.01%, 3.65–8.84%, 1.75–2.58%, and 6.19–16.01%, respectively, although some of these increases were not statistically significant. Notably, the combination of CI and EOC application significantly increased CPMI by 19.45–20.29% (p < 0.05), with the highest values observed in CI treatments amended with either straw or hydrochar. Hydrochar application had a smaller effect on increasing soil active OC fractions compared to straw incorporation, but demonstrated a greater potential for long-term SOC sequestration. These findings demonstrate the potential of hydrochar as a waste-derived amendment for long-term carbon sequestration and provide insights for optimizing water–carbon management strategies in sustainable rice cultivation.

1. Introduction

The sustainable management of agricultural residues is a major challenge in many crop production systems. Large amounts of crop straw are generated annually, and improper disposal (e.g., open burning or abandonment) not only wastes potential resources but also causes severe environmental problems such as air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions [1,2,3,4]. Returning straw or its derivatives (e.g., biochar and hydrochar) to farmland is increasingly recognized as an effective waste utilization strategy, contributing to circular economy goals and soil fertility improvement [5,6,7].

At the same time, soil organic carbon (SOC) is the largest terrestrial carbon pool, and its preservation is essential for maintaining soil quality and mitigating climate change [8]. Even minor changes in SOC stocks can significantly alter atmospheric CO2 concentrations [8]. However, SOC turnover is a slow process, and significant changes in SOC often take years or even decades to become detectable following management interventions [9,10]. To assess the short-term effects of management practices on soil carbon dynamics, research has increasingly focused on labile SOC fractions, i.e., microbial biomass carbon (MBC), readily oxidizable organic carbon (ROC), and dissolved organic carbon (DOC), which represent the biologically and chemically active components of SOC. MBC reflects the living microbial pool that mediates carbon transformation, while ROC and DOC indicate the easily decomposable and soluble organic substrates available for microbial metabolism. These fractions are highly sensitive to soil aeration, redox status, and substrate input, and thus respond rapidly to changes in irrigation regimes and organic amendments [11]. Additionally, the carbon pool management index (CPMI) integrates the size (carbon pool index, CPI) and activity (carbon lability index, LI) of SOC fractions to reflect overall soil carbon quality and management efficiency [12]. Therefore, the combination of SOC and its labile fractions provide a comprehensive framework for evaluating soil carbon responses to different irrigation and residue management strategies in rice systems.

Different residue management options have distinct implications for SOC dynamics [13,14,15]. Direct straw incorporation was reported to increase MBC, ROC, DOC, and CPMI [16], contributing to short-term improvements in soil fertility and productivity [17]. However, its rapid decomposition can lead to nitrogen competition [18], short-term nutrient imbalances [19], and substantial greenhouse gas emissions (CO2 and CH4), which may limit its effectiveness in long-term carbon sequestration [20]. Biochar, in contrast, is highly stable and effective for long-term carbon storage [21] but has limited short-term bioavailability and involves high production costs [22]. Given these limitations, hydrochar, a novel carbon-based material produced via hydrothermal carbonization, is gaining attention as a potential alternative to straw and biochar [23,24,25]. Compared to raw straw, hydrochar exhibits higher aromaticity and biological stability [26,27], making it a potential option for long-term SOC sequestration. Moreover, hydrochar production occurs at relatively low temperatures (180–380 °C), which reduces energy consumption and enhances its environmental sustainability compared to other thermally processed organic amendments [20,28]. Despite these potential benefits, the response of soil labile OC fractions and CPMI to hydrochar return remains unclear.

In addition to organic amendments, irrigation management also plays a crucial role in shaping SOC dynamics and stability [29,30]. The widespread adoption of water-saving irrigation techniques in paddy fields has substantially altered soil environmental conditions and microbial communities, and increased soil microbial growth rates [31,32,33]. Changes in water regimes influence microbial activity and SOC decomposition [34,35], thereby affecting labile SOC fractions and CPMI. Yet, research remains limited on how labile SOC fractions and CPMI respond to the combined effects of hydrochar application and water-saving irrigation in paddy soils.

To address this gap, a two-year pot experiment using paddy soil under field conditions was conducted to evaluate the combined impacts of hydrochar (compared with straw) and irrigation regimes (flooding vs. controlled irrigation) on SOC and its labile fractions (ROC, DOC, MBC), as well as the CPMI. We hypothesize that (i) compared with flooding irrigation, controlled irrigation (CI) would increase ROC, DOC, and MBC by improving soil aeration and promoting microbial activity, thereby enhancing short-term carbon turnover and stabilization; (ii) straw incorporation would cause a more pronounced increase in labile carbon fractions (ROC, DOC, MBC) and CPMI owing to its high biodegradability and easily decomposable components, while hydrochar would contribute more to long-term SOC accumulation due to its recalcitrant carbon structures; and (iii) the interaction between CI and organic amendments would be synergistic, where CI enhances microbial decomposition of straw and stabilization of hydrochar-derived carbon, ultimately improving overall soil carbon quality and CPMI. These hypotheses aim to clarify how water management and residue recycling pathways jointly regulate soil carbon dynamics in rice systems and to provide practical guidance for optimizing sustainable irrigation and organic waste utilization strategies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Site Description and Hydrochar

Soil was collected from Kunshan Experiment Station (31°15′46″ N, 120°58′04″ E), Jiangsu Province, China. The site is located in a subtropical humid monsoon climate, where the annual average temperature is 15.7 °C and the annual precipitation is 1094 mm, of which 50% occurs in summer. The soil type is hydragric anthrosol, with pH 6.63 (1:2.5, soil/water).

Hydrochar was produced from rice straw via microwave-assisted hydrothermal carbonization (HTC). The process was conducted in 100 mL quartz reactor vessels, each containing 3 g of rice straw and 21 mL of deionized water. The quartz reactors were securely sealed and placed inside a 35 L microwave reactor (XT-9906, Shanghai Xintuo, Shanghai, China). The temperature was ramped to 200 °C and maintained for 2 h. After the reaction, the solid hydrochar was separated using a Büchner funnel (Shanghai Glassware Co., Shanghai, China) fitted with filter paper (pore size 10 μm), followed by air drying for subsequent characterization. The properties of rice straw and straw-derived hydrochar are provided in Table 1, and the methods for determining the physicochemical properties of hydrochar and straw are shown in Text S1.

Table 1.

The properties of rice straw and straw-derived hydrochar. Values are means ± standard error (n = 3).

2.2. Experimental Design

Given that current HTC technology does not yet support large-scale field application, a pot experiment was conducted in this study. The experiment followed a 2 × 3 factorial design, with two irrigation regimes—flooding irrigation (FI) and controlled irrigation (CI)—and three exogenous organic carbon (EOC) application treatments: (i) without EOC addition (nitrogen fertilizer only, N); (ii) straw + N fertilizer (ST); and (iii) straw-derived hydrochar + N fertilizer (HC). Rice was grown in cylindrical soil columns (inner diameter: 35 cm, height: 42 cm). For the ST and HC treatments, rice straw and hydrochar were incorporated into the 0–20 cm soil layer at a rate of 6000 kg ha−1 and 3776 kg ha−1, respectively, assuming a hydrochar productivity ratio of 63%. Before incorporation, the ST was air-dried and cut into 2–3 cm pieces, while the HC, in fine powder form, was directly mixed with the soil. There were 6 treatments with 3 replicates. To better simulate the growing environment of rice with field conditions, the pots were randomly placed in the paddy field under the same water management practices.

Rice seedlings (Nanjing 46, a local prevailing japonica rice variety) were transplanted at the end of June and harvested at the end of October. The transplanting density included 2 hills per container with 3 plants per hill. In this study, 63.0 kg P2O5 ha−1, 89.3 kg K2O ha−1, and 188.0 kg urea-N ha−1 were applied before rice transplantation as basal fertilizer (BF); 69.3 kg urea-N ha−1 as tillering fertilizer (TF); and 55.4 kg urea-N ha−1 as panicle fertilizer (PF). In the FI treatments, 3–5 cm floodwater was maintained during the rice growing season, except for during the late tillering and ripening stages prior to harvest (Table S1). The irrigation regime of CI is shown in Table S1. To control weeds and pests, herbicides (herbicide) and insecticides (insecticide) were applied during the trial in accordance with conventional weed and pest management practices.

2.3. Soil Sampling and Analysis

Soil samples were collected at the tillering, jointing–booting, milk, and ripening stages during both rice seasons in 2021 and 2022. For each treatment, five composite soil cores (0–20 cm depth) were randomly collected and combined into a single sample. Each soil sample was divided into two sub-samples: one was air-dried and sieved through a 100-mesh screen to determine the SOC and ROC, while the other was immediately stored at 4 °C for the analysis of DOC and MBC.

The ROC was measured with a 333 mmol L−1 KMnO4 oxidation method [36]. SOC concentrations were determined using a TOC analyzer (Multi N/C 2100, Jena, Germany). The water-dissolvable OC fraction (DOC) was extracted from fresh soil samples using distilled water at a 1:10 soil-to-solution ratio (w/v) and shaken for 2 h at 25 °C. The suspension was centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 10 min and filtered through a 0.45 μm membrane before TOC analysis (Multi N/C 2100, Jena, Germany). SMBC was determined by the chloroform fumigation–extraction method [37]. Briefly, fumigated and non-fumigated soil samples were extracted with 0.5 M K2SO4 (1:4 w/v) and analyzed for organic C using a TOC analyzer. Microbial biomass C was calculated as the difference between fumigated and non-fumigated extracts, divided by a conversion factor (kEC = 0.45).

2.4. Carbon Pool Management Index (CPMI)

The soil carbon pool management index (CPMI, %) is calculated using the following equation:

where CPI is the soil carbon pool index; LI is the carbon lability index.

CPI is calculated as follows:

where sample SOC is the SOC content from treatments with straw or hydrochar amendment, g kg−1; reference SOC is the SOC in the control treatment (FN treatment), g kg−1.

LI is calculated as

where sample L is the lability of sample soil from each treatment with straw or hydrochar return; reference L is the lability of reference soil in the control treatment.

The carbon lability (L) is the ratio of labile carbon to non-labile carbon, which was represented by the changes in the proportion of the ROC in the soil and was calculated as follows:

2.5. Statistical Analysis

All variables in figures or tables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to analyze the differences in soil properties, labile organic carbon contents, and CPMI among treatments (p < 0.05). Duncan’s new multiple range test was used to assess the significance of differences between treatment means. Two-way ANOVA was employed to examine the effects of irrigation management (FI vs. CI) and EOC addition (control, straw and hydrochar) on soil labile organic carbon contents. The model included main effects of irrigation and EOC, as well as the irrigation × EOC interaction. Multiple comparisons among treatment means were performed using Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) test to control Type I error. Prior to ANOVA, the assumptions of normality (Shapiro–Wilk test) and homogeneity of variances (Levene’s test) were verified. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS v 24.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), and data visualization was conducted using Origin 2023 (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA). Finally, a structural equation model (SEM) was used to evaluate the direct and indirect effects of ROC, MBC, DOC, and SOC on CPMI. The model’s fitness was assessed using degrees of freedom (df), the χ2/df ratio, probability level (p), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), goodness-of-fit index (GFI), and comparative fit index (CFI). SEM analysis was conducted in the Amos 24.0 (IBM SPSS Amos Development Company, Armonk, NY, USA) environment.

3. Results

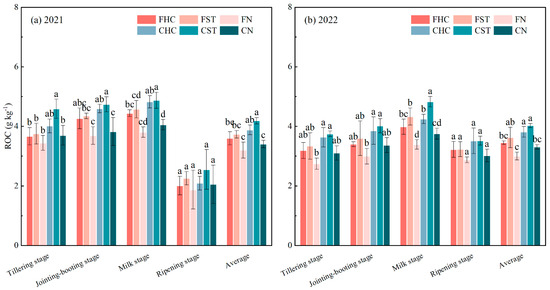

3.1. Soil ROC

ROC at different rice growth stages in 2021 and 2022 is shown in Figure 1. In 2021, ROC content ranged from 1.88 g kg−1 (FN) to 4.88 g kg−1 (CST), whereas in 2022, it varied from 2.74 g kg−1 (FN) to 4.83 g kg−1 (CST). CI increased soil ROC compared with FI. Specially, compared to FN, CN increased the average ROC content by 6.37% in 2021 and 10.34% in 2022. Treatments with hydrochar or straw application showed a greater increase in soil ROC under CI. EOC addition further increased ROC content in different growth stages of rice, with values exceeding those under CK by 1.90–24.38% in 2021 and by 12.12–28.65% in 2022. Straw incorporation resulted in higher ROC than hydrochar incorporation, with increases ranging from 1.15 to 22.06% in 2021 and 0.17 to 13.65% in 2022 at different growth stages of rice. Overall, both CI and EOC addition promoted soil ROC, with the highest levels observed in CST. Furthermore, the average ROC contents in CHC and CST treatments were 7.83% and 12.19% (p < 0.05) higher than those in FHC and FST, respectively, in 2021, and 10.50% (p < 0.05) and 11.12% higher in 2022.

Figure 1.

Soil readily organic carbon (ROC) content at different growth stages of rice in 2021 and 2022. FHC, flooding irrigation with straw-derived hydrochar; FST, flooding irrigation with rice straw input; FN, flooding irrigation with no exogenous organic carbon addition; CHC, controlled irrigation with straw-derived hydrochar; CST, controlled irrigation with rice straw input; CN, controlled irrigation with no exogenous organic carbon addition. Error bars represent standard error (n = 3). Different lowercase letters above each bar indicate significant differences among different treatments at p < 0.05.

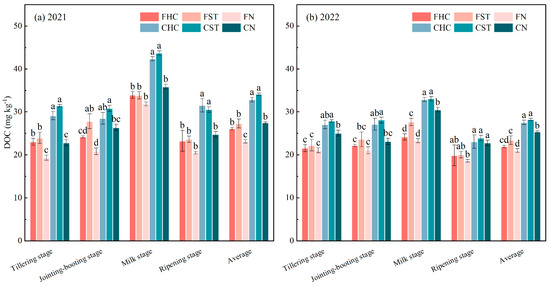

3.2. Soil DOC

Under CI treatment, DOC content was 17.88–35.68% (p < 0.05) higher in 2021 and 9.78–36.25% (p < 0.05) higher in 2022 compared to FI treatment across different growth stages (Figure 2). EOC addition increased the average DOC content across different growth stages, with increases of 6.14–37.80% in 2021 and 1.40–18.75% in 2022 compared to the unamended controls, although some data did not show statistically significant differences (Figure 2). Across all treatments, both CI and EOC addition promoted soil DOC. Under FI, hydrochar and straw amendment significantly increased the average DOC content by 12.84% and 18.03% in 2021 compared to FN (p < 0.05), while in 2022, only straw amendment significantly increased the average DOC content by 11.36% (p < 0.05). Under CI, hydrochar and straw amendment significantly increased the average DOC content by 19.78% and 24.35% in 2021 (p < 0.05) and by 8.62% and 11.36% in 2022 (p < 0.05), compared to CN. The highest soil DOC was observed in the EOC addition treatment under CI, with no significant difference between the straw return and hydrochar return treatments.

Figure 2.

Soil dissolved organic carbon (DOC) content at different growth stages of rice in 2021 and 2022. FHC, flooding irrigation with straw-derived hydrochar; FST, flooding irrigation with rice straw input; FN, flooding irrigation with no exogenous organic carbon addition; CHC, controlled irrigation with straw-derived hydrochar; CST, controlled irrigation with rice straw input; CN, controlled irrigation with no exogenous organic carbon addition. Error bars represent standard error (n = 3). Different lowercase letters above each bar indicate significant differences among different treatments at p < 0.05.

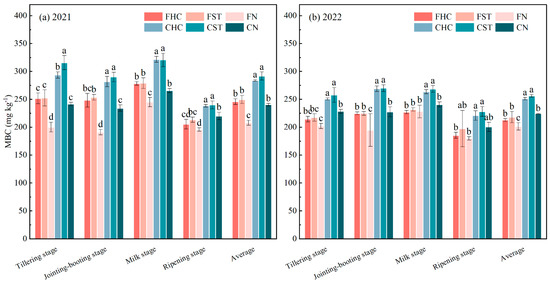

3.3. Soil MBC

Similarly to the distribution patterns of ROC and DOC, both irrigation managements and EOC addition had significant effects on soil MBC content (Figure 3). In 2021, soil MBC under CI conditions was significantly higher than under FI, with increases of 16.63–25.13%, 13.54–22.59%, and 8.47–15.58% during the tillering stage, jointing–booting stage, and milk stage (p < 0.05), respectively, while no significant difference was observed during the ripening stage. In 2022, CI significantly increased soil MBC by 12.98–18.56% and 16.91–20.12% (p < 0.05) during the tillering stage and jointing–booting stage, whereas no significant difference was observed during the milk stage (7.15–15.72% increase) or ripening stage (11.41–15.54% increase) compared to FI. CI significantly increased seasonal average soil MBC content by 15.43–17.03% in 2021 and by 11.95–17.97% in 2022 regardless of EOC addition, compared to FI (p < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Soil microbial biomass carbon (MBC) content at different growth stages of rice in 2021 and 2022. FHC, flooding irrigation with straw-derived hydrochar; FST, flooding irrigation with rice straw input; FN, flooding irrigation with no exogenous organic carbon addition; CHC, controlled irrigation with straw-derived hydrochar; CST, controlled irrigation with rice straw input; CN, controlled irrigation with no exogenous organic carbon addition. Error bars represent standard error (n = 3). Different lowercase letters above each bar indicate significant differences among different treatments at p < 0.05.

The EOC addition also significantly increased soil MBC content across different growth stages (Figure 3). Compared to the unamended controls, EOC addition increased soil MBC by 21.51–30.73% (p < 0.05), 20.37–32.75%, 13.68–21.32%, and 5.02–9.09% during the tillering stage, jointing–booting stage, milk stage, and ripening stage in 2021, and by 6.09–12.87%, 15.47–18.65%, 0.94–11.44%, and 0.05–13.91% in 2022. The seasonal average soil MBC content increased by 18.11–21.51% (p < 0.05) and 6.24–14.18% in 2021 and 2022 compared to the unamended controls. Among all treatments, the highest soil MBC was observed in the EOC addition treatment under CI, with no significant difference between the straw return and hydrochar return treatments.

3.4. SOC and CPMI

The two-way ANOVA showed that EOC addition had a significant effect on SOC (p < 0.01), whereas the irrigation regime and their interaction had no significant effects (Table 2). SOC content under CI treatments increased by 1.75–2.60% compared to FI treatments, although the difference was not statistically significant. Similarly, EOC addition increased SOC by 5.82–8.40% under FI and 5.29–7.50% under CI conditions, but these differences were also not significant. Unlike changes in soil labile organic carbon, the overall increase in SOC among treatments was relatively small. Furthermore, SOC content in the straw return treatment was 2.06–2.38% lower than that in the hydrochar return treatment, although this difference was not statistically significant. Among all treatments, the highest SOC content (14.47 g kg−1) was observed in the CI treatment with hydrochar amendment, while the lowest (13.12 g kg−1) was recorded in the FI treatment without EOC addition.

Table 2.

The distribution of carbon lability (L), carbon lability index (LI), carbon pool index (CPI), and carbon pool management index (CPMI) in the 0–20 cm soil layer in 2022. Values are means ± standard error (n = 3).

The two-way ANOVA showed that, at the rice harvest stage in 2022, EOC addition significantly affected LI, CPI, and CPMI (p < 0.05). However, the irrigation regime and its interaction with EOC addition had no significant effects on L, LI, CPI, or CPMI (Table 2). CI increased L, LI, CPI, and CPMI by 3.39–14.01%, 3.65–8.84%, 1.75–2.58%, and 6.19–16.01%, although most of these increments were not statistically significant (Table 2). Under CI, straw and hydrochar addition increased CPI by 5.29–7.50%, and CPMI by 19.45–20.29%, respectively. The highest CPMI was observed in the EOC addition treatment under CI, which was significantly higher than CPMI in the CN and FN treatments (Table 2).

4. Discussion

4.1. Irrigation Regimes as a Management Tool for Improving Carbon Retention and Resource Efficiency

Compared with FI, CI increased SOC and its labile fractions, particularly MBC and DOC. This indicates that irrigation management exerts a key influence on soil carbon turnover by altering soil aeration and microbial processes. Under CI, alternating wetting and drying cycles enhance oxygen diffusion and periodically raise the soil redox potential. These shifts stimulate oxidative enzyme activities and promote aerobic microbial metabolism, resulting in more efficient decomposition of easily degradable organic matter. Meanwhile, partial drying phases facilitate the stabilization of decomposed residues through organo-mineral associations, thereby retaining a larger portion of carbon within the soil system.

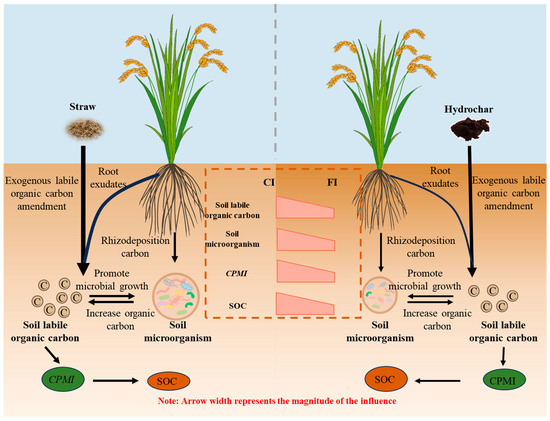

Two main factors contributed to the enhanced labile carbon pool. First, CI promoted greater root-derived carbon input through increased exudation and residue accumulation, thereby strengthening the transfer of photosynthetic carbon into the soil system [32,38]. Second, CI maintained unsaturated soil moisture levels for longer periods, which stimulated microbial activity (as shown in Figure 3 for MBC) and enzyme-mediated decomposition, leading to higher concentrations of labile SOC fractions such as MBC and DOC. Thus, CI primarily enhanced SOC and its labile fractions by increasing root-derived carbon input and stimulating microbial decomposition of organic matter (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of the mechanism of increasing soil labile organic carbon pool through irrigation management and EOC amendment.

Overall, CI not only reduces water consumption but also creates a more favorable environment for stabilizing carbon derived from recycled residues such as straw and hydrochar. This highlights the potential of integrating waste recycling practices with water-saving irrigation strategies to maximize carbon sequestration benefits, improve soil fertility, and support sustainable agricultural production.

4.2. Residue Recycling Pathways: Contrasting Effects of Straw and Hydrochar on Carbon Dynamics

The recycling of agricultural residues through direct incorporation or hydrothermal carbonization (hydrochar production) substantially increased SOC and its labile fractions, confirming the value of organic amendments for carbon management in paddy soils. However, the two residue recycling pathways showed distinct patterns in regulating labile versus stable carbon pools.

Straw incorporation led to a more pronounced increase in labile SOC fractions compared to hydrochar, particularly DOC and MBC (Figure 4). This is primarily due to its high content of easily decomposable components—such as soluble sugars, starch, and hemicellulose—which serve as immediate substrates for microbial metabolism. These compounds stimulate microbial proliferation and enzyme activity, resulting in elevated DOC and MBC levels during the early stages of decomposition. Furthermore, the rapid mineralization of straw enhances microbial turnover and increases the short-term carbon pool activity. However, this rapid decomposition also implies that much of the added carbon is quickly mineralized, limiting the potential for long-term sequestration.

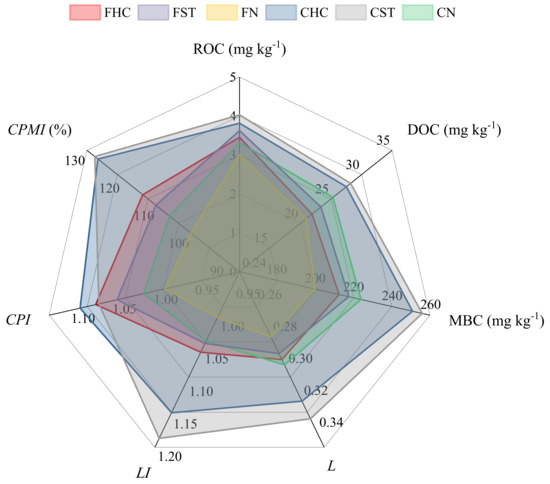

In contrast, hydrochar application exhibited a more moderate effect on labile carbon fractions but contributed more to long-term SOC accumulation (Figure 5). The hydrothermal carbonization process alters the chemical composition of straw (Table 1), producing materials with higher aromaticity, condensed carbon rings, and lower proportions of labile compounds [39,40,41]. Although the short-term changes in MBC and DOC were smaller than those observed for straw, hydrochar treatments consistently maintained higher total SOC, suggesting potential for longer-term stabilization [42,43]. Nevertheless, given the short experimental duration, these results indicate only a potential trend rather than conclusive evidence of long-term sequestration.

Figure 5.

Radar chart of soil active carbon pools in 2022. ROC: readily oxidizable organic carbon; DOC: dissolved organic carbon; MBC: microbial biomass carbon; L: C lability; LI: carbon lability index; CPI: carbon pool index; and CPMI: carbon pool management index.

Across different rice growth stages (tillering, jointing–booting, milk, and ripening), ROC, DOC, and MBC increased during the early stages and declined in the later stages. This pattern likely reflects changes in carbon availability and microbial activity: root exudates and labile carbon are abundant during early growth, stimulating microbial biomass and activity, while carbon input decreases as plants translocate nutrients to grains.

The contrasting behaviors of straw and hydrochar highlight a key trade-off in residue management: straw amendment enhances short-term carbon activation and microbial activity, while hydrochar favors long-term carbon retention. From a waste management perspective, the choice between straw and hydrochar should be aligned with management objectives—whether the priority is immediate productivity gains or building long-term soil carbon stocks. In practice, combining hydrochar with water-saving irrigation may offer a synergistic strategy, maximizing both resource efficiency and environmental sustainability.

4.3. Evaluation of Residue Recycling and Irrigation Strategies for Soil Carbon Management Using CPMI

The CPMI integrates both the size and activity of SOC, providing a sensitive indicator for assessing the effectiveness of residue recycling and water management practices for soil carbon enhancement [12,44,45]. In this study, both CI and the addition of organic carbon amendments (straw or hydrochar) significantly increased CPMI compared with their respective controls, although the magnitude and pathways of improvement differed.

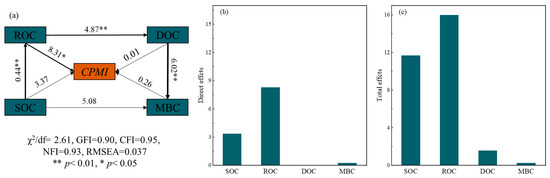

EOC addition, whether straw or hydrochar, consistently improved CPMI (Figure 4), reflecting enhanced carbon pool activity. Straw primarily stimulated labile carbon fractions (e.g., ROC) and microbial activity [46,47], leading to immediate increases in CPMI. Hydrochar, while having a more moderate effect on labile carbon, contributed indirectly through the accumulation of stabilized SOC. The structural equation model (Figure 6) confirmed that ROC had the strongest direct effect on CPMI (path coefficient = 8.31, p < 0.05), while SOC exerted a higher indirect influence through its contribution to carbon stability (path coefficient: 8.33). The comparable CPMI values between straw and hydrochar treatments therefore result from different underlying mechanisms—fast turnover versus gradual stabilization.

Figure 6.

The structural equation modeling of soil carbon pool management index (CPMI) and its influencing factors (a), and the direct effect (b) and total effect (c) of ROC, DOC, MBC, and SOC on CPMI. ROC: readily oxidizable organic carbon; DOC: dissolved organic carbon; MBC: microbial biomass carbon. df: degrees of freedom; χ2/df: Chi-square divided by degrees of freedom GFI: goodness-of-fit index; CFI: comparative fit index; NFI: normed fit index; RMSEA: root mean square error of approximation. Single arrows indicate hypothesized causal directions. Black and red arrows represent significant positive and negative correlations, respectively. Numbers on arrows indicate standardized path coefficients, and arrow width represents the magnitude of their path coefficients. * on arrows indicate significance, with * representing significance at p < 0.05 and ** representing significance at p < 0.01.

Furthermore, CI amplified the positive effects of EOC addition on CPMI. The intermittent aerobic conditions under CI enhanced microbial efficiency and enzymatic activity, accelerating the transformation of labile carbon while promoting partial stabilization of decomposed residues [48,49]. As a result, the highest CPMI values were observed in CI treatments combined with EOC, indicating synergistic benefits of integrating water and organic carbon management.

From a waste management perspective, these findings highlight that optimizing CPMI requires balancing labile and stable carbon inputs. The combined application of CI and hydrochar represents a promising strategy, offering both immediate improvements in soil quality and long-term carbon stabilization—particularly under water-constrained conditions where maximizing carbon and water use efficiency is critical for sustainable rice production.

This study was conducted under controlled pot conditions within two growing seasons. Although this design allowed precise control of irrigation and carbon inputs, it does not fully capture the spatial and temporal variability of field conditions. Moreover, the short experimental duration limits the ability to evaluate changes in more stable carbon pools and long-term sequestration potential. Future research should therefore extend to multi-year, field-scale experiments combining isotopic or spectroscopic tracing techniques to better quantify carbon stabilization pathways under coupled water and carbon management.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that both irrigation regimes and exogenous organic carbon (EOC) amendments play crucial roles in regulating soil organic carbon (SOC) dynamics and quality in paddy fields. CI primarily enhanced SOC and its labile fractions, as well as CPMI. But most of the differences between CI and FI were not statistically significant, except for some labile fractions in the condition with straw return (CST vs. FST). In most cases, EOC (straw and hydrochar) significantly increased ROC, DOC, and MBC, and consequently CPMI (p < 0.05). Straw incorporation mainly stimulated short-term labile carbon due to its easily decomposable components, whereas hydrochar contributed to greater long-term SOC accumulation owing to its higher chemical stability and resistance to microbial degradation. While these results provide evidence of distinct carbon transformation patterns between straw and hydrochar, the short experimental duration limits conclusions about long-term sequestration effects. Future research should focus on evaluating the persistence of hydrochar-derived carbon under field conditions and its interactions with irrigation management across multiple cropping seasons. From a practical perspective, integrating waste recycling with optimized water management shows potential to enhance soil quality and resource efficiency, contributing to the sustainability of rice production under water-limited conditions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agronomy15122686/s1: Text S1: Methods for determining the physicochemical properties of hydrochar and straw; Table S1: Soil moisture thresholds in different rice growth stages under controlled irrigation and flooding irrigation. Refs. [50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57] are cited in the Supplementary.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.W. and J.X.; Formal analysis, K.W.; Funding acquisition, K.W. and J.X.; Investigation, K.W., P.C. and L.L.; Methodology, K.W., J.X., L.Z. and Y.Q.; Visualization: J.Z. and J.F.; Formal analysis, P.C.; writing—original draft preparation, K.W.; writing—review and editing, J.X., L.L. and J.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Science and Technology Plan Project of Suzhou City (SNG2022030); Chinese Universities Scientific Fund (2452025045); and the Program for Jiangsu Excellent Scientific and Technological Innovation Team.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SOC | Soil organic carbon |

| MBC | Microbial biomass carbon |

| ROC | Readily oxidizable organic carbon |

| DOC | Dissolved organic carbon |

| CPMI | Carbon pool management index |

| HTC | Hydrothermal carbonization |

| FI | Flooding irrigation |

| CI | Controlled irrigation |

| EOC | Exogenous organic carbon |

| ST | Straw |

| HC | Hydrochar |

| FN | Flooding irrigation + nitrogen fertilizer only |

| CN | Controlled irrigation + nitrogen fertilizer only |

| FHC | Flooding irrigation + hydrochar + nitrogen fertilizer |

| CHC | Controlled irrigation + hydrochar + nitrogen fertilizer |

| FST | Flooding irrigation + straw + nitrogen fertilizer |

| CST | Controlled irrigation + straw + nitrogen fertilizer |

| BF | Basal fertilizer |

| TF | Tillering fertilizer |

| PF | Panicle fertilizer |

| CPI | Soil carbon pool index |

| LI | Carbon lability index |

| L | Lability of sample soil |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| df | Degrees of freedom |

| χ2/df | Chi-square divided by degrees of freedom |

| p | Probability level |

| RMSEA | Root mean square error of approximation |

| GFI | Goodness-of-fit index |

| CFI | Comparative fit index |

References

- Singh, G.; Arya, S.K. A review on management of rice straw by use of cleaner technologies: Abundant opportunities and expectations for Indian farming. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 291, 125278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, P.; Bisen, J.; Bhaduri, D.; Priyadarsini, S.; Munda, S.; Chakraborti, M.; Adak, T.; Panneerselvam, P.; Mukherjee, A.K.; Swain, S.L.; et al. Turn the wheel from waste to wealth: Economic and environmental gain of sustainable rice straw management practices over field burning in reference to India. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 775, 145896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, H.A.; Phuong, D.M.; Linh, L.T. Emission inventories of rice straw open burning in the Red River Delta of Vietnam: Evaluation of the potential of satellite data. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 260, 113972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, A.; Mathew, A.K.; Sindhu, R.; Pandey, A.; Binod, P. Potential of rice straw for bio-refining: An overview. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 215, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Liu, B.Y.; Liu, S.L.; Qi, J.Y.; Wang, X.; Pu, C.; Li, S.S.; Zhang, X.Z.; Yang, X.G.; Lal, R.; et al. Sustaining crop production in China’s cropland by crop residue retention: A meta-analysis. Land Degrad. Dev. 2020, 31, 694–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.J.; Kong, F.X.; Lv, X.B.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, Z.G.; Meng, Y.L. Responses of greenhouse gas emissions to different straw management methods with the same amount of carbon input in cotton field. Soil Tillage Res. 2021, 213, 105126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.L.; Ge, T.D.; van Groenigen, K.J.; Yang, Y.H.; Wang, P.; Cheng, K.; Zhu, Z.K.; Wang, J.K.; Li, Y.; Guggenberger, G.; et al. Rice paddy soils are a quantitatively important carbon store according to a global synthesis. Commun. Earth Environ. 2021, 2, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Soil carbon sequestration to mitigate climate change. Geoderma 2004, 123, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P. How long before a change in soil organic carbon can be detected? Glob. Change Biol. 2004, 10, 1878–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poeplau, C.; Don, A. Sensitivity of soil organic carbon stocks and fractions to different land-use changes across Europe. Geoderma 2013, 192, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anahita, K.; Zheng, H.; Liu, Q.; Hashemi, M.; Tang, Y.; Xing, B. Production and characterization of hydrochars and their application in soil improvement and environmental remediation. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 420, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diekow, J.; Mielniczuk, J.; Knicker, H.; Bayer, C.; Dick, D.P.; Kögel-Knabner, I. Carbon and nitrogen stocks in physical fractions of a subtropical Acrisol as influenced by long-term no-till cropping systems and N fertilisation. Plant Soil 2005, 268, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.U.; Guo, Z.; Jiang, F.; Peng, X. Does straw return increase crop yield in the wheat-maize cropping system in China? A meta-analysis. Field Crops Res. 2022, 279, 108447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Arlotti, D.; Huyghebaert, B.; Tebbe, C.C. Disentangling the impact of contrasting agricultural management practices on soil microbial communities—Importance of rare bacterial community members. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2022, 166, 108573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.C.; Xu, J.Z.; Chen, P.; Liao, L.X.; Fan, J.L.; Wang, H.; Sleutel, S. Balancing energy inputs and carbon outcomes in hydrochar applications: Temperature-Dependent effects on soil carbon sequestration. Biomass Bioenerg. 2026, 204, 108382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Sun, X.; Li, L.; Liu, X.; Zhang, B.; Zheng, J.; Pan, G. Change in active microbial community structure, abundance and carbon cycling in an acid rice paddy soil with the addition of biochar. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2016, 67, 857–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, R.; Wang, J.; Wang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, T.; Li, X.; Cong, R.; Lu, J. Long-term straw return enhanced crop yield by improving ecosystem multifunctionality and soil quality under triple rotation system: An evidence from a 15 years study. Field Crops Res. 2024, 312, 109395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Qiu, T.; Peñuelas, J.; Sardans, J.; Tan, W.; Wei, X.; Cui, Y.; Cui, Q.; Wu, C.; Liu, L.; et al. Crop residue return sustains global soil ecological stoichiometry balance. Glob. Change Biol. 2023, 29, 2203–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ninkuu, V.; Liu, Z.; Qin, A.; Xie, Y.; Song, X.; Sun, X. Impact of straw returning on soil ecology and crop yield: A review. Heliyon 2025, 11, e41651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.C.; Xu, J.Z.; Guo, H.; Min, Z.H.; Wei, Q.; Chen, P.; Sleutel, S. Reuse of straw in the form of hydrochar: Balancing the carbon budget and rice production under different irrigation management. Waste Manag. 2024, 189, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Pang, J.; Zhang, M.; Tian, Z.; Wei, T.; Jia, Z.; Ren, X.; Zhang, P. Is adding biochar be better than crop straw for improving soil aggregates stability and organic carbon contents in film mulched fields in semiarid regions? –Evidence of 5-year field experiment. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 338, 117711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, R.; Shao, C.; Li, D.; Bai, S.; Hou, N.; Zhao, X. Biochar and Hydrochar from Agricultural Residues for Soil Conditioning: Life Cycle Assessment and Microbially Mediated C and N Cycles. Acs Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 3574–3583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entwistle, J.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, H.Y.; Tapia-Ruiz, N. 5.09—Materials Synthesis for Na-Ion Batteries, in Comprehensive Inorganic Chemistry III, 3rd ed.; Reedi, J., Poeppelmeier, K.R., Seshadri, R., Cussen, S., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2023; pp. 199–215. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.; Xie, W.; Yao, R.; Feng, Y.; Wang, X.; Xie, H.; Feng, Y.; Yang, J. Biochar and hydrochar application influence soil ammonia volatilization and the dissolved organic matter in salt-affected soils. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 926, 171845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.J.; Zhang, X.; Suo, F.Y.; You, X.W.; Yuan, Y.; Cheng, Y.D.; Zhang, C.S.; Li, Y.Q. Effect of biochar and hydrochar from cow manure and reed straw on lettuce growth in an acidified soil. Chemosphere 2022, 298, 134191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.D.; Liu, Y.C.; Qian, F.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, S.C.; Chen, J.M. Role of Hydrochar Properties on the Porosity of Hydrochar-based Porous Carbon for Their Sustainable Application. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2015, 3, 833–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garlapalli, R.K.; Wirth, B.; Reza, M.T. Pyrolysis of hydrochar from digestate: Effect of hydrothermal carbonization and pyrolysis temperatures on pyrochar formation. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 220, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kambo, H.S.; Dutta, A. A comparative review of biochar and hydrochar in terms of production, physico-chemical properties and applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 45, 359–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, K.R.; Malik, A.A.; Muscarella, C.; Blankinship, J.C. Irrigation alters biogeochemical processes to increase both inorganic and organic carbon in arid-calcic cropland soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2023, 187, 109189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Xu, J.Z.; Zhang, Z.X.; Wang, K.C.; Li, T.C.; Wei, Q.; Li, Y.W. Carbon pathways in aggregates and density fractions in Mollisols under water and straw management: Evidence from C-13 natural abundance. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2022, 169, 108684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Xu, J.; Wang, K.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, X.; Wei, Q.; Nie, T.; Zhou, Z.; Meng, Q.; Lei, C. Biochar-or straw-mediated alteration in rice paddy microbial community structure and its urea-C utilization are depended on irrigation regimes. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2024, 203, 105608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishfaq, M.; Farooq, M.; Zulfiqar, U.; Hussain, S.; Akbar, N.; Nawaz, A.; Anjum, S.A. Alternate wetting and drying: A water-saving and ecofriendly rice production system. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 241, 106363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Xu, J.Z.; Wang, K.C.; Zhang, Z.X.; Zhou, Z.Q.; Li, Y.W.; Li, T.C.; Nie, T.Z.; Wei, Q.; Liao, L.X. Straw return combined with water-saving irrigation increases microbial necromass accumulation by accelerating microbial growth-turnover in Mollisols of paddy fields. Geoderma 2025, 454, 117211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Deng, S.; Wu, Y.; Yi, W.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, X.; Xing, P.; Gu, Q.; Qi, J.; Tang, X. A rapid increase of soil organic carbon in paddy fields after applying organic fertilizer with reduced inorganic fertilizer and water-saving irrigation is linked with alterations in the structure and function of soil bacteria. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2025, 379, 109353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Deng, S.; Yi, W.; Wu, Y.; Cui, B.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, X.; Zhang, X.; Yang, H.; Tang, X. Modulation of greenhouse gas emissions and soil organic carbon in rice paddies through various crop rotation systems combined with water-saving irrigation: Insights into soil bacterial composition and functional alterations. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2025, 394, 109897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, G.; Lefroy, R.; Lisle, L. Soil carbon fractions based on their degree of oxidation, and the development of a carbon management index for agricultural systems. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 1995, 46, 1459–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookes, P.C.; Landman, A.; Pruden, G.; Jenkinson, D.S. Chloroform fumigation and the release of soil nitrogen: A rapid direct extraction method to measure microbial biomass nitrogen in soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1985, 17, 837–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wen, Y.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Yang, X.; Lin, Z.; Song, Z.; Cooper, J.M.; Zhao, B. Soil labile organic carbon fractions and soil organic carbon stocks as affected by long-term organic and mineral fertilization regimes in the North China Plain. Soil Tillage Res. 2018, 175, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soroush, S.; Ronsse, F.; Park, J.; Ghysels, S.; Wu, D.; Kim, K.-W.; Heynderickx, P.M. Microwave assisted and conventional hydrothermal treatment of waste seaweed: Comparison of hydrochar properties and energy efficiency. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 878, 163193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Funke, A.; Ziegler, F. Hydrothermal carbonization of biomass: A summary and discussion of chemical mechanisms for process engineering. Biofuels Bioprod. Biorefining 2010, 4, 160–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, M.; Dutta, A.; Acharya, B.; Mahmud, S. A review of the current knowledge and challenges of hydrothermal carbonization for biomass conversion. J. Energy Inst. 2019, 92, 1779–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.L.; Han, L.J.; Huang, G.Q. Effect of water-washing of wheat straw and hydrothermal temperature on its hydrochar evolution and combustion properties. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 269, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raheem, A.; He, Q.; Ding, L.; Dastyar, W.; Yu, G. Evaluating performance of pyrolysis and gasification processes of agriculture residues-derived hydrochar: Effect of hydrothermal carbonization. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 338, 130578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Hu, N.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, J.; Tao, B.; Meng, Y. Short-term responses of soil organic carbon and carbon pool management index to different annual straw return rates in a rice–wheat cropping system. CATENA 2015, 135, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Xu, D.; Rong, J.; Ai, X.; Ai, S.; Su, X.; Sheng, M.; Yang, S.; Zhang, J.; Ai, Y. Landslide and aspect effects on artificial soil organic carbon fractions and the carbon pool management index on road-cut slopes in an alpine region. CATENA 2021, 199, 105094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siedt, M.; Schäffer, A.; Smith, K.E.C.; Nabel, M.; Roß-Nickoll, M.; van Dongen, J.T. Comparing straw, compost, and biochar regarding their suitability as agricultural soil amendments to affect soil structure, nutrient leaching, microbial communities, and the fate of pesticides. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 751, 141607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, P.; Fu, Q.; Li, T.; Liu, D.; Hou, R.; Li, Q.; Li, M.; Meng, F. Effects of biochar and straw application on the soil structure and water-holding and gas transport capacities in seasonally frozen soil areas. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 301, 113943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, N.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, S.; Sun, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zheng, X.; Li, S.; Zhang, J.; Lv, W. Long-term effects of straw return and straw-derived biochar amendment on bacterial communities in soil aggregates. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 7891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Song, Y.; Wu, Z.; Yan, X.; Gunina, A.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Xiong, Z. Effects of six-year biochar amendment on soil aggregation, crop growth, and nitrogen and phosphorus use efficiencies in a rice-wheat rotation. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 242, 118435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakemore, L.C.; Searle, P.L.; Daly, B.K. Methods for Chemical Analysis of Soils; NZ Soil Bureau, Department of Scientific and Industrial Research: Wellington, New Zealand, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, F.; Zhao, L.; Gao, B.; Xu, X.Y.; Cao, X.D. The Interfacial Behavior between Biochar and Soil Minerals and Its Effect on Biochar Stability. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 2264–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helrich, K. Association of official analytical chemists. In Official Methods of Analysis of the Association of Official Analytical Chemists, 15th ed.; Association of Official Analytical Chemist: Washington, DC, USA, 1990; Volume 12. [Google Scholar]

- Van Soest, P.J.; Robertson, J.B.; Lewis, B.A. Methods for Dietary Fiber, Neutral Detergent Fiber, and Nonstarch Polysaccharides in Relation to Animal Nutrition. J. Dairy Sci. 1991, 74, 3583–3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L.; Orthofer, R.; Lamuela-Raventos, R.M. Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. In Oxidants and Antioxidants; Packer, L., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999; pp. 152–178. [Google Scholar]

- Dreywood, R. Qualitative Test for Carbohydrate Material. Ind. Eng. Chem. Anal. Ed. 1946, 18, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galvão, M.; Arruda, A.; Bezerra, I.; Ferreira, M.; Soares, L. Evaluation of the Folin-Ciocalteu Method and Quantification of Total Tannins in Stem Barks and Pods from Libidibia ferrea (Mart. ex Tul) L. P. Queiroz. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2018, 61, e18170586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).