Agroecological Soil Management of an Organic Apple Orchard: Impact of Flowering Living Mulches on Soil Nutrients and Bacterial Activity Indices

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Site and Management Practices

2.2. Living Mulches

2.3. Soil Sample Collection

2.4. Soil Chemical Analysis

2.5. Soil Microbial Biodiversity and Activity Assessment

2.6. DNA Extraction and Sequencing

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Effect on Soil Nutrient Content

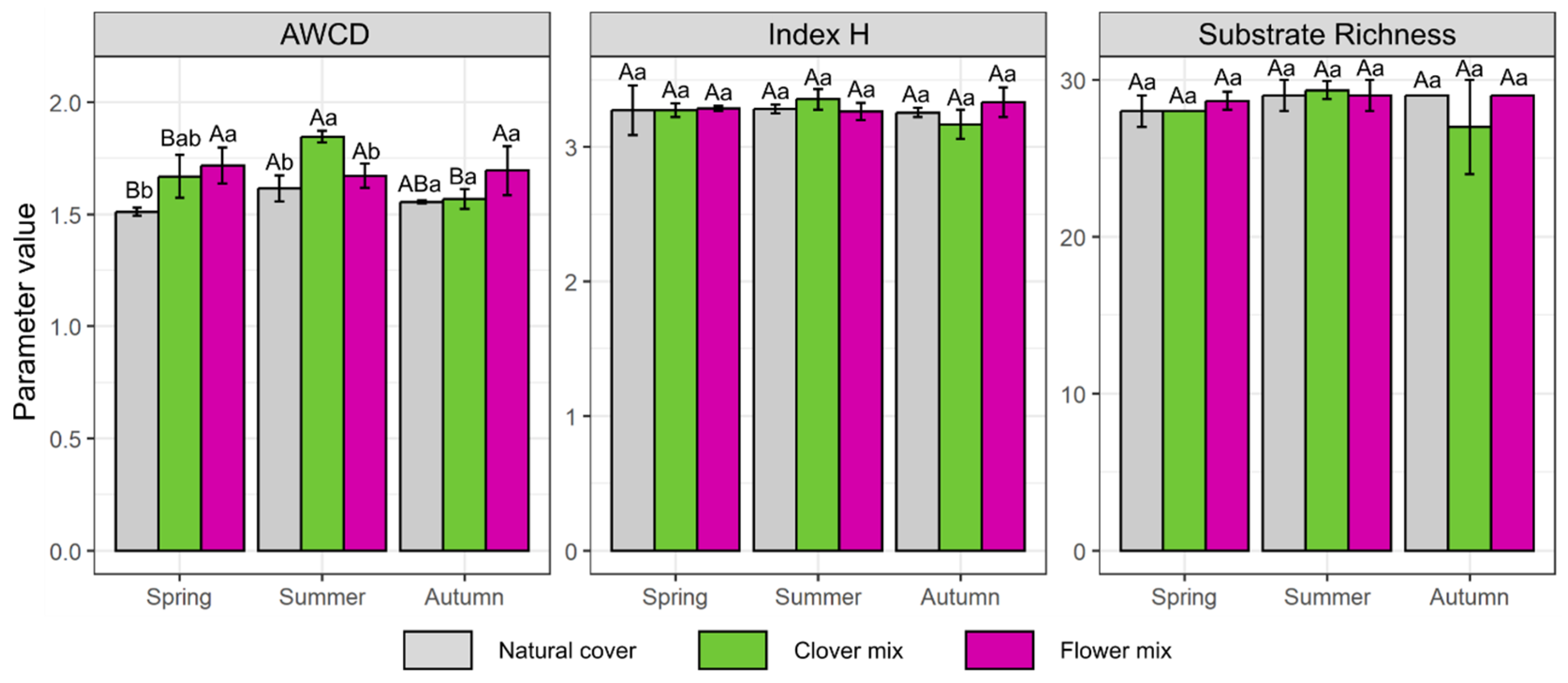

3.2. Effect on Soil Bacterial Activity and Biodiversity

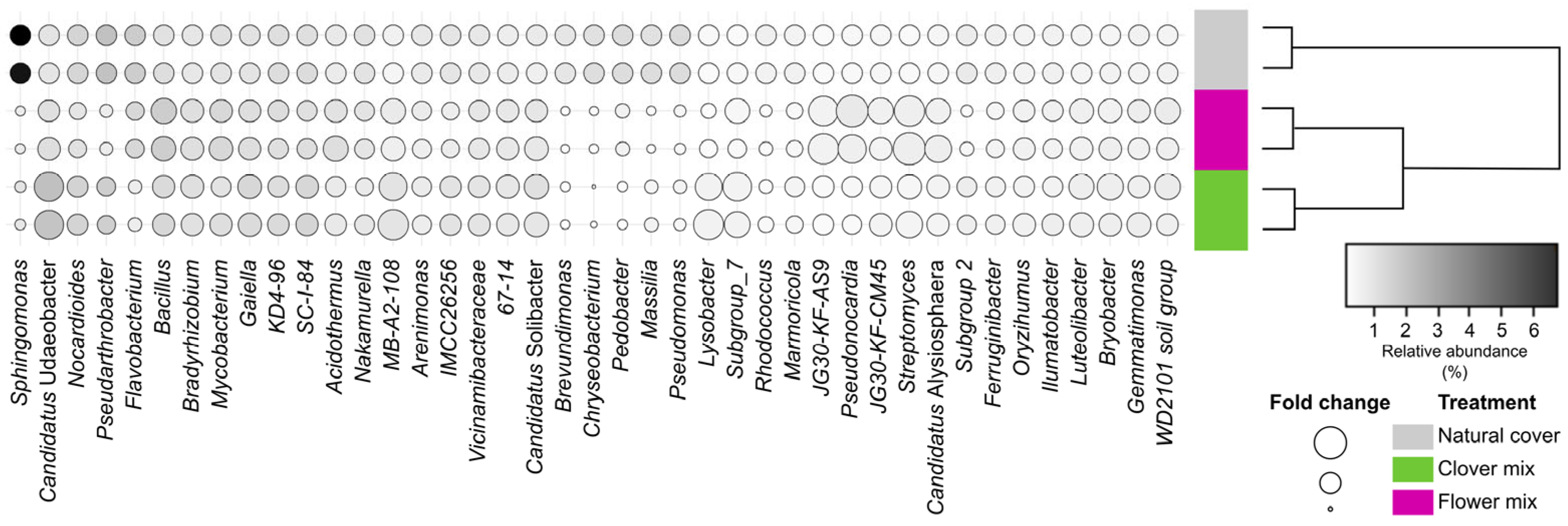

3.3. Soil Bacterial Microbiome Associated with Living Mulch Mixtures

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030—Bringing Nature Back into Our Lives; COM2020380 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, T.B.; Alford, A.M.; Bilbo, T.R.; Boyle, S.C.; Doughty, H.B.; Kuhar, T.P.; Lopez, L.; McIntyre, K.C.; Stawara, A.K.; Walgenbach, J.F.; et al. Living Mulches Reduce Natural Enemies When Combined with Frequent Pesticide Applications. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2023, 357, 108680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalska, J.; Antkowiak, M.; Sienkiewicz, P. Flower Strips and Their Ecological Multifunctionality in Agricultural Fields. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Las Casas, G.; Ciaccia, C.; Iovino, V.; Ferlito, F.; Torrisi, B.; Lodolini, E.M.; Giuffrida, A.; Catania, R.; Nicolosi, E.; Bella, S. Effects of Different Inter-Row Soil Management and Intra-Row Living Mulch on Spontaneous Flora, Beneficial Insects, and Growth of Young Olive Trees in Southern Italy. Plants 2022, 11, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merwin, I.A.; Ray, J.A.; Curtis, P.D. Orchard Groundcover Management Systems Affect Meadow Vole Populations and Damage to Apple Trees. HortScience 1999, 34, 271–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granatstein, D.; Mullinix, K. Mulching Options for Northwest Organic and Conventional Orchards. HortScience 2008, 43, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, G.S.; Cresswell, A.; Jones, S.; Allen, D.K. The Nitrogen Handling Characteristics of White Clover (Trifolium repens L.) Cultivars and a Perennial Ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.) Cultivar. J. Exp. Bot. 2000, 51, 1879–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, T.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Li, H. Intercropped Relationship Change the Developmental Pattern of Apple and White Clover. Bioengineered 2019, 10, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.; Gu, J.; Pan, H.; Zhang, K.; Sun, W.; Wang, X.; Gao, H. Effects of Living Mulches on the Soil Nutrient Contents, Enzyme Activities, and Bacterial Community Diversities of Apple Orchard Soils. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2015, 70, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednar, Z.; Vaupel, A.; Blümel, S.; Herwig, N.; Hommel, B.; Haberlah-Korr, V.; Beule, L. Earthworm and Soil Microbial Communities in Flower Strip Mixtures. Plant Soil 2023, 492, 209–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, M.; Kleijn, D.; Williams, N.M.; Tschumi, M.; Blaauw, B.R.; Bommarco, R.; Campbell, A.J.; Dainese, M.; Drummond, F.A.; Entling, M.H.; et al. The Effectiveness of Flower Strips and Hedgerows on Pest Control, Pollination Services and Crop Yield: A Quantitative Synthesis. Ecol. Lett. 2020, 23, 1488–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sechi, V.; De Goede, R.G.M.; Rutgers, M.; Brussaard, L.; Mulder, C. A Community Trait-Based Approach to Ecosystem Functioning in Soil. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2017, 239, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Acunto, L.; Semmartin, M.; Ghersa, C.M. Uncultivated Margins Are Source of Soil Microbial Diversity in an Agricultural Landscape. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2016, 220, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincze, É.-B.; Becze, A.; Laslo, É.; Mara, G. Beneficial Soil Microbiomes and Their Potential Role in Plant Growth and Soil Fertility. Agriculture 2024, 14, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Song, Y.; An, Y.; Lu, Y.; Zhong, G. Soil Microorganisms: Their Role in Enhancing Crop Nutrition and Health. Diversity 2024, 16, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, T.; Qadir, M.F.; Khan, K.S.; Eash, N.S.; Yousuf, M.; Chatterjee, S.; Manzoor, R.; Rehman, S.U.; Oetting, J.N. Unraveling the Potential of Microbes in Decomposition of Organic Matter and Release of Carbon in the Ecosystem. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 344, 118529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, P.; Sharma, N.; Tapwal, A.; Kumar, A.; Verma, G.S.; Meena, M.; Seth, C.S.; Swapnil, P. Soil Microbiome: Diversity, Benefits and Interactions with Plants. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koza, N.A.; Adedayo, A.A.; Babalola, O.O.; Kappo, A.P. Microorganisms in Plant Growth and Development: Roles in Abiotic Stress Tolerance and Secondary Metabolites Secretion. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, M.; Poonam; Ahmad, S.; Singh, R.P. Plant Growth Promoting Microbes: Diverse Roles for Sustainable and Ecofriendly Agriculture. Energy Nexus 2022, 7, 100133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoyo, G. How Plants Recruit Their Microbiome? New Insights into Beneficial Interactions. J. Adv. Res. 2022, 40, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wassermann, B.; Müller, H.; Berg, G. An Apple a Day: Which Bacteria Do We Eat with Organic and Conventional Apples? Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 475179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicaksono, W.A.; Buko, A.; Kusstatscher, P.; Cernava, T.; Sinkkonen, A.; Laitinen, O.H.; Virtanen, S.M.; Hyöty, H.; Berg, G. Impact of Cultivation and Origin on the Fruit Microbiome of Apples and Blueberries and Implications for the Exposome. Microb. Ecol. 2023, 86, 973–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangeot-Peter, L.; Tschaplinski, T.J.; Engle, N.L.; Veneault-Fourrey, C.; Martin, F.; Deveau, A. Impacts of Soil Microbiome Variations on Root Colonization by Fungi and Bacteria and on the Metabolome of Populus tremula × alba. Phytobiomes J. 2020, 4, 142–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, S.R.; Wisniewski, M.E.; Droby, S.; Abdelfattah, A.; Freilich, S.; Mazzola, M. The Apple Microbiome: Structure, Function, and Manipulation for Improved Plant Health. In The Apple Genome; Korban, S.S., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 341–382. ISBN 978-3-030-74682-7. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. European Union Regulation (EU) 2018/848 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 2018 on Organ-Ic Production and Labelling of Organic Products and Repealing Council Regulation (EC) No 834/2007. J. Eur. Union 2018, L150/1, 1–92. [Google Scholar]

- Babik, J.; Kowalczyk, W. Determination of the Optimal Nitrogen Content in a Fertigation Medium for the Greenhouse Cucumber Grown on Slabs of Compressed Straw. J. Fruit Ornam. Plant Res. 2009, 71, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, E.; Ferreras, L.; Toresani, S. Soil Bacterial Functional Diversity as Influenced by Organic Amendment Application. Bioresour. Technol. 2006, 97, 1484–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zak, J.C.; Willig, M.R.; Moorhead, D.L.; Wildman, H.G. Functional Diversity of Microbial Communities: A Quantitative Approach. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1994, 26, 1101–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- De Mendiburu, F. Agricolae: Statistical Procedures for Agricultural Research. 2023. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=agricolae (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Warnes, G.R.; Bolker, B.; Bonebakker, L.; Gentleman, R.; Huber, W.; Liaw, A.; Lumley, T.; Maechler, M.; Magnusson, A.; Moeller, S.; et al. Gplots: Various R Programming Tools for Plotting Data. 2024. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=gplots (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Wickham, H. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis (Use R!), 2nd ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; ISBN 978-3-319-24275-0. [Google Scholar]

- Egan, L.M.; Hofmann, R.W.; Ghamkhar, K.; Hoyos-Villegas, V. Prospects for Trifolium Improvement Through Germplasm Characterisation and Pre-Breeding in New Zealand and Beyond. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 653191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furmanczyk, E.M.; Malusà, E. In-Depth Insight into the Short-Term Effect of Floor Management Practice on Young Apple Orchard Wellness and Soil Microbial Biodiversity and Activity. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0329979. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Han, X.; Yan, W.; Cheng, L.; Dang, X.; Liu, W. Apple Trees Can Extract Soil Water from Both Deep Layers and Neighboring Cropland in the Tableland Region of Chinese Loess Plateau. CATENA 2023, 232, 107396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furmanczyk, E.M.; Malusà, E.; Kozacki, D.; Tartanus, M. Insights into the Belowground Biodiversity and Soil Nutrient Status of an Organic Apple Orchard as Affected by Living Mulches. Agriculture 2024, 14, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, S.L.; Reardon, C.L.; Mazzola, M. The Response of Ammonia-Oxidizer Activity and Community Structure to Fertilizer Amendment of Orchard Soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2014, 68, 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bougnom, B.P.; Greber, B.; Franke-Whittle, I.H.; Casera, C.; Insam, H. Soil Microbial Dynamics in Organic (Biodynamic) and Integrated Apple Orchards. Org. Agric. 2012, 2, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A.E.; Zeglin, L.H.; Wanzek, T.A.; Myrold, D.D.; Bottomley, P.J. Dynamics of Ammonia-Oxidizing Archaea and Bacteria Populations and Contributions to Soil Nitrification Potentials. ISME J. 2012, 6, 2024–2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gentile, R.M.; Boldingh, H.L.; Campbell, R.E.; Gee, M.; Gould, N.; Lo, P.; McNally, S.; Park, K.C.; Richardson, A.C.; Stringer, L.D.; et al. System Nutrient Dynamics in Orchards: A Research Roadmap for Nutrient Management in Apple and Kiwifruit. A Review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 42, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abril, A.; Zurdo-Piñeiro, J.L.; Peix, A.; Rivas, R.; Velázquez, E. Solubilization of Phosphate by a Strain of Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. trifolii Isolated from Phaseolus vulgaris in El Chaco Arido Soil (Argentina). In Develpoments in Plant and Soil Sciences, Proceedings of the First International Meeting on Microbial Phosphate Solubilization, Salamanca, Spain, 16–19 July 2002; Velázquez, E., Rodríguez-Barrueco, C., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 135–138. [Google Scholar]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Bhuyan, M.H.M.B.; Nahar, K.; Hossain, M.S.; Mahmud, J.A.; Hossen, M.S.; Masud, A.A.C.; Moumita; Fujita, M. Potassium: A Vital Regulator of Plant Responses and Tolerance to Abiotic Stresses. Agronomy 2018, 8, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollerton, J.; Lack, A. Relationships between Flowering Phenology, Plant Size and Reproductive Success in Shape Lotus corniculatus (Fabaceae). Plant Ecol. 1998, 139, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atucha, A.; Merwin, I.A.; Purohit, C.K.; Brown, M.G. Nitrogen Dynamics and Nutrient Budgets in Four Orchard Groundcover Management Systems. HortScience 2011, 46, 1184–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pregitzer, K.S.; King, J.S. Effects of Soil Temperature on Nutrient Uptake. In Nutrient Acquisition by Plants: An Ecological Perspective; BassiriRad, H., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 277–310. ISBN 978-3-540-27675-3. [Google Scholar]

- Glass, A.D. Homeostatic Processes for the Optimization of Nutrient Absorption: Physiology and Molecular Biology. In Nutrient Acquisition by Plants: An Ecological Perspective; BassiriRad, H., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 117–145. ISBN 978-3-540-27675-3. [Google Scholar]

- Allison, V.J.; Miller, R.M.; Jastrow, J.D.; Matamala, R.; Zak, D.R. Changes in Soil Microbial Community Structure in a Tallgrass Prairie Chronosequence. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2005, 69, 1412–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badri, D.V.; Vivanco, J.M. Regulation and Function of Root Exudates. Plant Cell Environ. 2009, 32, 666–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinauer, K.; Chatzinotas, A.; Eisenhauer, N. Root Exudate Cocktails: The Link between Plant Diversity and Soil Microorganisms? Ecol. Evol. 2016, 6, 7387–7396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altieri, M.A.; Nicholls, C.I.; Dinelli, G.; Negri, L. Towards an Agroecological Approach to Crop Health: Reducing Pest Incidence through Synergies between Plant Diversity and Soil Microbial Ecology. npj Sustain. Agric. 2024, 2, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vives-Peris, V.; de Ollas, C.; Gómez-Cadenas, A.; Pérez-Clemente, R.M. Root Exudates: From Plant to Rhizosphere and Beyond. Plant Cell Rep. 2020, 39, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birkhofer, K.; Bezemer, T.M.; Bloem, J.; Bonkowski, M.; Christensen, S.; Dubois, D.; Ekelund, F.; Fließbach, A.; Gunst, L.; Hedlund, K.; et al. Long-Term Organic Farming Fosters below and Aboveground Biota: Implications for Soil Quality, Biological Control and Productivity. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2008, 40, 2297–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, M.; Eisenhauer, N.; Sierra, C.A.; Bessler, H.; Engels, C.; Griffiths, R.I.; Mellado-Vázquez, P.G.; Malik, A.A.; Roy, J.; Scheu, S.; et al. Plant Diversity Increases Soil Microbial Activity and Soil Carbon Storage. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhauer, N. Plant Diversity Effects on Soil Microorganisms: Spatial and Temporal Heterogeneity of Plant Inputs Increase Soil Biodiversity. Pedobiologia 2016, 59, 175–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lori, M.; Symnaczik, S.; Mäder, P.; Deyn, G.D.; Gattinger, A. Organic Farming Enhances Soil Microbial Abundance and Activity—A Meta-Analysis and Meta-Regression. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0180442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Y.; Reeve, J.R.; Norton, J.M. Soil Enzyme Activities and Abundance of Microbial Functional Genes Involved in Nitrogen Transformations in an Organic Farming System. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2018, 54, 437–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.; Gu, J.; Sun, W.; Li, Y.-D.; Fu, Q.-X.; Wang, X.-J.; Gao, H. Changes in the Soil Nutrient Levels, Enzyme Activities, Microbial Community Function, and Structure during Apple Orchard Maturation. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2014, 77, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, R.; Huang, Q.; Li, H. Long-Term Cover Cropping Seasonally Affects Soil Microbial Carbon Metabolism in an Apple Orchard. Bioengineered 2019, 10, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuermann, D.; Döll, S.; Schweneker, D.; Feuerstein, U.; Gentsch, N.; von Wirén, N. Distinct Metabolite Classes in Root Exudates Are Indicative for Field- or Hydroponically-Grown Cover Crops. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1122285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, B.-J.; Adriano, D.C.; Bolan, N.S.; Barton, C.D. Root Exudates and Microorganisms. In Encyclopedia of Soils in the Environment; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 421–428. ISBN 978-0-12-348530-4. [Google Scholar]

- Paynel, F.; Murray, P.J.; Bernard Cliquet, J. Root Exudates: A Pathway for Short-Term N Transfer from Clover and Ryegrass. Plant Soil 2001, 229, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.; Langridge, H.; Straathof, A.L.; Muhamadali, H.; Hollywood, K.A.; Goodacre, R.; de Vries, F.T. Root Functional Traits Explain Root Exudation Rate and Composition across a Range of Grassland Species. J. Ecol. 2022, 110, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer, D.; Malique, F.; Alfarraj, S.; Albasher, G.; Horn, M.A.; Butterbach-Bahl, K.; Dannenmann, M.; Rennenberg, H. Interactive Regulation of Root Exudation and Rhizosphere Denitrification by Plant Metabolite Content and Soil Properties. Plant Soil 2021, 467, 107–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Wang, H.; Yang, F.; Dai, X.; Meng, S.; Hu, M.; Kou, L.; Fu, X. Relationships between Root Exudation and Root Morphological and Architectural Traits Vary with Growing Season. Tree Physiol. 2024, 44, tpad118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, K.R.; Kaštovská, E.; Borovec, J.; Šantrucková, H.; Picek, T. Species Effects and Seasonal Trends on Plant Efflux Quantity and Quality in a Spruce Swamp Forest. Plant Soil 2018, 426, 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janusz, G.; Pawlik, A.; Sulej, J.; Świderska-Burek, U.; Jarosz-Wilkołazka, A.; Paszczyński, A. Lignin Degradation: Microorganisms, Enzymes Involved, Genomes Analysis and Evolution. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2017, 41, 941–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spohn, M.; Kuzyakov, Y. Distribution of Microbial- and Root-Derived Phosphatase Activities in the Rhizosphere Depending on P Availability and C Allocation—Coupling Soil Zymography with 14C Imaging. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2013, 67, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, C.; Wang, C.; Cai, A.; Zhou, Z. Global Magnitude of Rhizosphere Effects on Soil Microbial Communities and Carbon Cycling in Natural Terrestrial Ecosystems. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 856, 158961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Haas, B.; Dhooghe, E.; Geelen, D. Root Exudates in Soilless Culture Conditions. Plants 2025, 14, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, S.; Zhalnina, K.; Kosina, S.; Northen, T.R.; Sasse, J. The Core Metabolome and Root Exudation Dynamics of Three Phylogenetically Distinct Plant Species. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chu, Y.; Jia, Y.; Yue, H.; Han, Z.; Wang, Y. Changes to Bacterial Communities and Soil Metabolites in an Apple Orchard as a Legacy Effect of Different Intercropping Plants and Soil Management Practices. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 956840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Wang, R.; Kang, F.; Yan, X.; Sun, L.; Wang, N.; Gong, Y.; Gao, X.; Huang, L. Microbial Diversity Composition of Apple Tree Roots and Resistance of Apple Valsa Canker with Different Grafting Rootstock Types. BMC Microbiol. 2022, 22, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mia, M.J.; Furmanczyk, E.M.; Golian, J.; Kwiatkowska, J.; Malusá, E.; Neri, D. Living Mulch with Selected Herbs for Soil Management in Organic Apple Orchard. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukicevich, E.; Lowery, T.; Bowen, P.; Úrbez-Torres, J.R.; Hart, M. Cover Crops to Increase Soil Microbial Diversity and Mitigate Decline in Perennial Agriculture. A Review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 36, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blagodatskaya, E.; Kuzyakov, Y. Active Microorganisms in Soil: Critical Review of Estimation Criteria and Approaches. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2013, 67, 192–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piechulla, B.; Lemfack, M.C.; Kai, M. Effects of Discrete Bioactive Microbial Volatiles on Plants and Fungi. Plant Cell Environ. 2017, 40, 2042–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Mondéjar, R.; Tláskal, V.; Větrovský, T.; Štursová, M.; Toscan, R.; Nunes da Rocha, U.; Baldrian, P. Metagenomics and Stable Isotope Probing Reveal the Complementary Contribution of Fungal and Bacterial Communities in the Recycling of Dead Biomass in Forest Soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2020, 148, 107875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furmanczyk, E.M.; Kaminski, M.A.; Lipinski, L.; Dziembowski, A.; Sobczak, A. Pseudomonas laurylsulfatovorans sp. Nov., Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate Degrading Bacteria, Isolated from the Peaty Soil of a Wastewater Treatment Plant. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2018, 41, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, S.S.; David, M. Biodegradation of Flubendiamide by a Newly Isolated Chryseobacterium sp. Strain SSJ1. 3 Biotech 2016, 6, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ravintheran, S.K.; Sivaprakasam, S.; Loke, S.; Lee, S.Y.; Manickam, R.; Yahya, A.; Croft, L.; Millard, A.; Parimannan, S.; Rajandas, H. Complete Genome Sequence of Sphingomonas paucimobilis AIMST S2, a Xenobiotic-Degrading Bacterium. Sci. Data 2019, 6, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaim, S.; Bekkar, A.A. Advances in Research on the Use of Brevundimonas Spp. to Improve Crop and Soil Fertility and for Soil Bioremediation. Alger. J. Biosci. 2023, 4, 045–051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, R.; Ambrosini, A.; Passaglia, L.M.P. Plant Growth-Promoting Bacteria as Inoculants in Agricultural Soils. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2015, 38, 401–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Gera, R. Isolation of a Multi-Trait Plant Growth Promoting Brevundimonas sp. and Its Effect on the Growth of Bt-Cotton. 3 Biotech 2014, 4, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Specie Name (Percentage of the Mix-%) | |

|---|---|

| Plantago media (0.3%) | Medicago lupulina (1.5%) |

| Scorzoneroides autumnalis (0.4%) | Thymus pulegioides (0.2%) |

| Leontodon hipidus (0.4%) | Saponaria officinalis (0.4%) |

| Centaurea cynaus (2.0%) | Crepis capillaris (0.2%) |

| Centaurea jacea (1.2%) | Hypochaeris radicata (0.3%) |

| Campanula rapunculoides (0.2%) | Galium album (1.2%) |

| Campanula rotundifolia (0.1%) | Galium verum (0.5%) |

| Viola arvensis (0.2%) | Reseda lutea (0.2%) |

| Prunella vulgaris (0.5%) | Malva moschata (0.5%) |

| Dianthus deltoides (0.2%) | Malva neglecta (1.0%) |

| Hieracium pilosella (0.2%) | Leucanthemum vulgare (1.8%) |

| Lotus corniculatus (1.0%) | Cynosurus cristatus (4.0%) |

| Trifolium dubium (0.3%) | Festuca rubra (12.0%) |

| Trifolium pratense (0.5%) | Festuca ovina (17.0%) |

| Achillea millefolium (1.2%) | Agrostis capillaris (3.0%) |

| Sanguisorba minor (1.5%) | Bromus secalinus (20.0%) |

| Origanum vulgare (0.2%) | Anthoxanthum odoratum (5.0%) |

| Silene noctiflora (0.4%) | Poa angustifolia (5.0%) |

| Silene vulgaris (1.2%) | Poa compressa (4.0%) |

| Linaria vulgaris (0.2%) | Lolium perenne (10.0%) |

| Treatment | N | P | K |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural cover | 1.59 ± 0.13 a | 0.18 ± 0.01 b | 1.73 ± 0.06 a |

| Clover mix | 1.74 ± 0.08 a | 0.22 ± 0.01 a | 1.70 ± 0.07 a |

| Flower mix | 1.87 ± 0.14 a | 0.20 ± 0.00 a | 1.61 ± 0.11 a |

| p-value | 0.074 | 0.033 | 0.235 |

| F-value or Χ-value | 4.141 | 6.830 | 1.859 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Furmanczyk, E.M.; Malusà, E. Agroecological Soil Management of an Organic Apple Orchard: Impact of Flowering Living Mulches on Soil Nutrients and Bacterial Activity Indices. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2612. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112612

Furmanczyk EM, Malusà E. Agroecological Soil Management of an Organic Apple Orchard: Impact of Flowering Living Mulches on Soil Nutrients and Bacterial Activity Indices. Agronomy. 2025; 15(11):2612. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112612

Chicago/Turabian StyleFurmanczyk, Ewa Maria, and Eligio Malusà. 2025. "Agroecological Soil Management of an Organic Apple Orchard: Impact of Flowering Living Mulches on Soil Nutrients and Bacterial Activity Indices" Agronomy 15, no. 11: 2612. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112612

APA StyleFurmanczyk, E. M., & Malusà, E. (2025). Agroecological Soil Management of an Organic Apple Orchard: Impact of Flowering Living Mulches on Soil Nutrients and Bacterial Activity Indices. Agronomy, 15(11), 2612. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112612