Estimating Winter Wheat Leaf Water Content by Combining UAV Spectral and Texture Features with Stacking Ensemble Learning

Abstract

1. Introduction

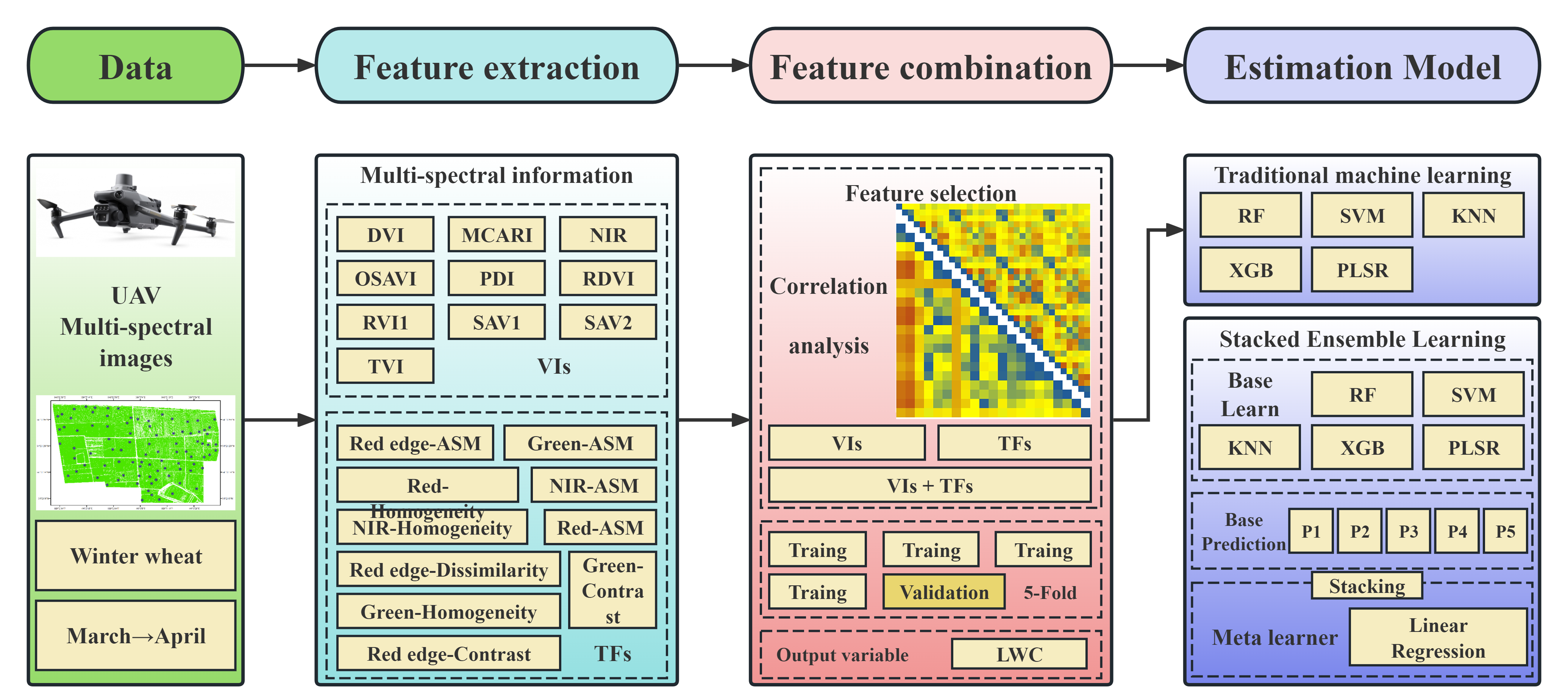

2. Materials and Methods

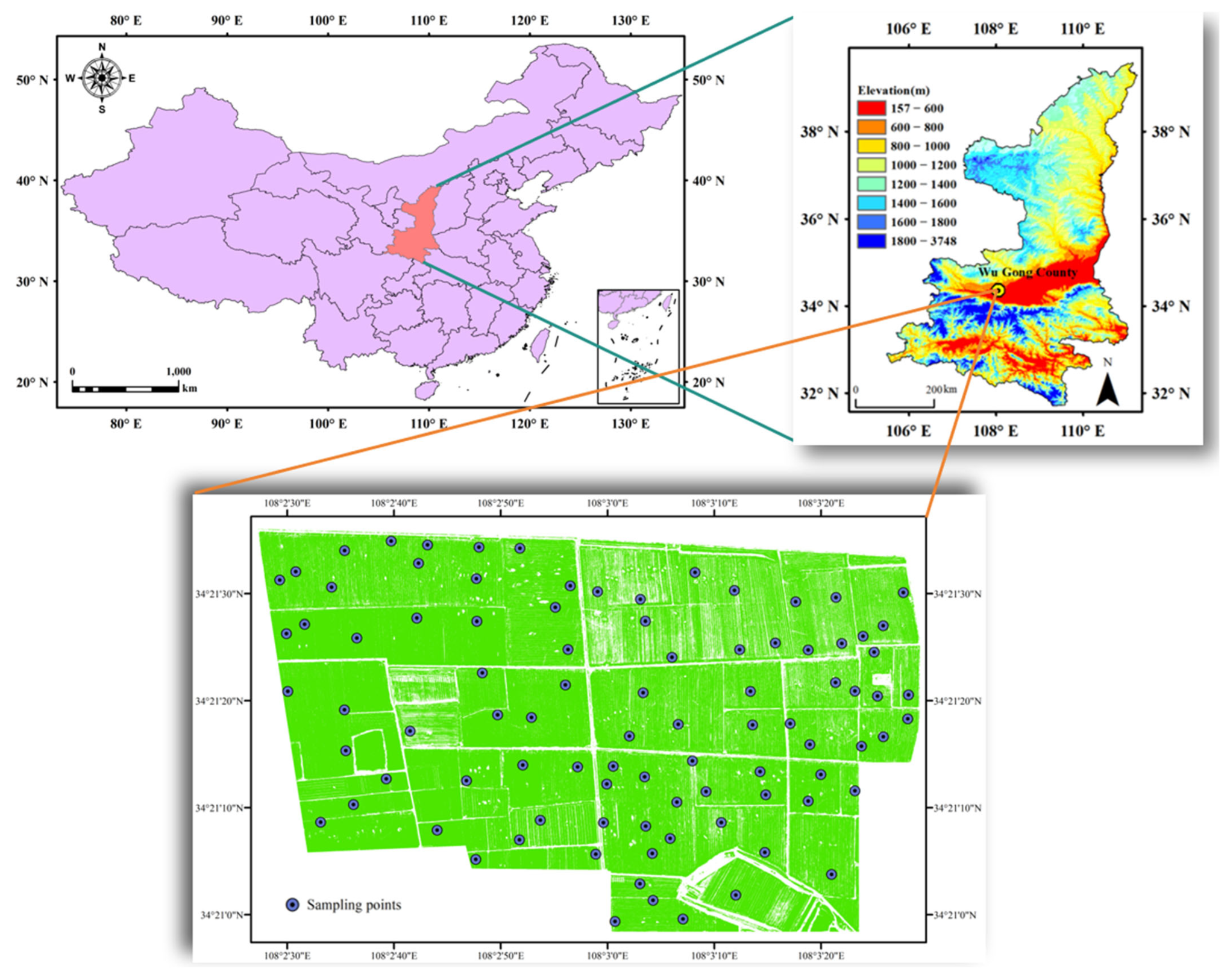

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Collection and Preprocessing

2.2.1. Ground Data Acquisition and Analysis

2.2.2. Spectral Data Acquisition and Processing

2.3. Vegetation Indices

2.4. Texture Features

2.5. Data Analysis

2.5.1. Statistical Analysis

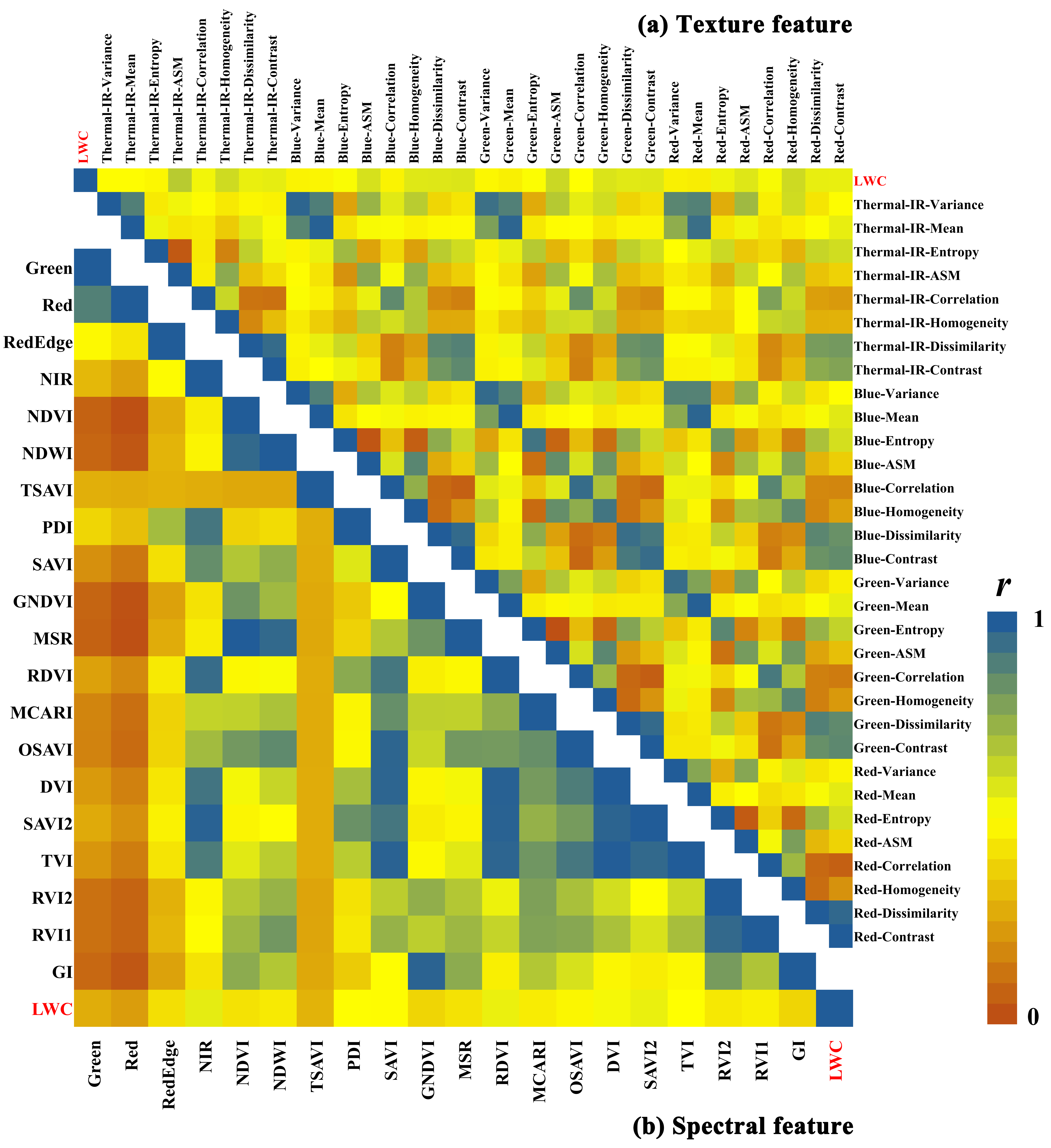

2.5.2. Correlation Analysis

2.6. Stacking Integration Model Construction

2.7. Feature Importance

2.8. Model Evaluation

3. Results

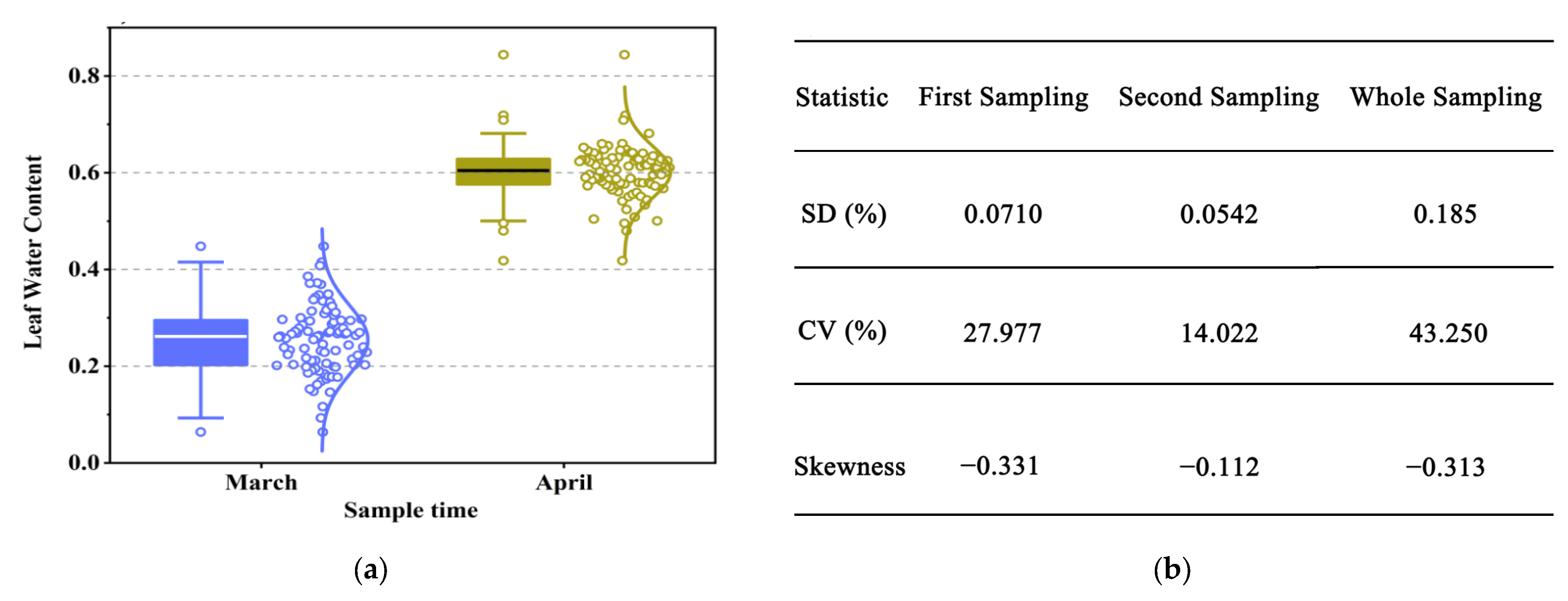

3.1. Statistical Analysis of Leaf Moisture Content

3.2. Feature Selection

3.3. LWC Estimation Based on a Single Feature

3.4. Combined Estimation of LWC Based on Spectral Vegetation Indices and Texture Features

3.5. Spatial Distribution of LWC

4. Discussion

4.1. The Input Feature Importance

4.2. Advantages of Multi-Feature Fusion

4.3. Advantages and Applicability of Stacked Ensemble Learning

4.4. Discussion on Opportunities for Enhancing LWC Estimation

4.5. Limitations and Outlook

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shiferaw, B.; Smale, M.; Braun, H.J.; Duveiller, E.; Reynolds, M.; Muricho, G. Crops that feed the world 10. Past successes and future challenges to the role played by wheat in global food security. Food Secur. 2013, 5, 291–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trifilò, P.; Abate, E.; Petruzzellis, F.; Azzarà, M.; Nardini, A. Critical water contents at leaf, stem and root level leading to irreversible drought-induced damage in two woody and one herbaceous species. Plant Cell Environ. 2023, 46, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, M.; Ebrahimi, E.; Naseh, S.; Mohajerpour, M. A new 1.4-GHz soil moisture sensor. Measurement 2012, 45, 1723–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Gu, H.N.; Yang, L.; Lyu, H.; Cheng, Y.; Pan, L.; Fu, Z.; Cui, L.; Zhang, L. A method of electrical conductivity compensation in a low-cost soil moisture sensing measurement based on capacitance. Measurement 2020, 150, 107052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bending, J.; Yu, K.; Aasen, H.; Bolten, A.; Bennertz, S.; Broscheit, J.; Gnyp, M.L.; Bareth, G. Combining UAV-based plant height from crop surface models, visible, and near infrared vegetation indices for biomass monitoring in barley. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2015, 39, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Mao, Z.H.; Li, X.J.; Hu, Z.; Duan, F.; Yan, Y. UAV-based multispectral remote sensing for precision agriculture: A comparison between different cameras. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2018, 146, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, P.; Xu, X.; Li, Z.; Yang, G.; Li, Z.; Feng, H.; Chen, G.; Fan, L.; Wang, Y.; Liu, S. Remote sensing estimation of nitrogen content in summer maize leaves based on multispectral images of UAV. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2019, 35, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, W.P.; Huang, W.J.; Ma, L.L.; Tang, L.; Li, C.; Zhou, X.; Casa, R. Estimating Vertical Distribution of Leaf Water Content within Wheat Canopies after Head Emergence. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza, C.Z.; Khot, L.R.; Sankaran, S.; Jacoby, P.W. High resolution multispectral and thermal remote sensing-based water stress assessment in subsurface irrigated grapevines. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, B.; Sahoo, R.N.; Pargal, S.; Krishna, G.; Verma, R.; Chinnusamy, V.; Sehgal, V.K.; Gupta, V.K. Comparison of different uni- and multi-variate techniques for monitoring leaf water status as an indicator of water-deficit stress in wheat through spectroscopy. Biosyst. Eng. 2017, 160, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsayed, S.; Elhoweity, M.; Ibrahim, H.H.; Dewir, Y.H.; Migdadi, H.M.; Schmidhalter, U. Thermal imaging and passive reflectance sensing to estimate the water status and grain yield of wheat under different irrigation regimes. Agric. Water Manag. 2017, 189, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, G.; Sahoo, R.N.; Singh, P.; Bajpai, V.; Patra, H.; Kumar, S.; Dandapani, R.; Gupta, V.K.; Viswanathan, C.; Ahmad, T.; et al. Comparison of various modeling approaches for water deficit stress monitoring in rice crop through hyperspectral remote sensing. Agric. Water Manag. 2019, 213, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, G.A. Ratios of leaf reflectances in narrow wavebands as indicators of plant stress. Int. J. Remote Sens. 1994, 15, 697–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filella, I.; Peñuelas, J. The red edge position and shape as indicators of plant chlorophyll content, biomass and hydric status. Int. J. Remote Sens. 1994, 15, 1459–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñuelas, J.; Piñol, J.; Ogaya, R.; Filella, I. Estimation of plant water concentration by the reflectance water index WI (R900/R970). Int. J. Remote Sens. 1997, 18, 2869–2875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, M.T.; Hunt, E.R.; Jackson, T.J. Remote sensing of vegetation water content from equivalent water thickness using satellite imagery. Remote Sens. Environ. 2008, 112, 2514–2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhyay, K.K.; Pradhan, S.; Sahoo, R.N.; Singh, R.; Gupta, V.; Joshi, D.; Sutradhar, A. Characterization of water stress and prediction of yield of wheat using spectral indices under varied water and nitrogen management practices. Agric. Water Manag. 2014, 146, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baluja, J.; Diago, M.P.; Balda, P.; Zorer, R.; Meggio, F.; Morales, F.; Tardaguila, J. Assessment of vineyard water status variability by thermal and multispectral imagery using an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV). Irrig. Sci. 2012, 30, 511–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Jin, Y.; Alsina, M.M.; McElrone, A.J.; Bambach, N.; Kustas, W.P. Vine water status mapping with multispectral UAV imagery and machine learning. Irrig. Sci. 2022, 40, 715–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.C.; Wang, J.L.; Li, J.Y.; Wang, J.; Xu, H.; Liu, T.; Wang, J. Estimating Maize Leaf Water Content Using Machine Learning with Diverse Multispectral Image Features. Plants 2025, 14, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterday, K.; Kislik, C.; Dawson, T.E.; Hogan, S.; Kelly, M. Remotely Sensed Water Limitation in Vegetation: Insights from an Experiment with Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs). Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fariñas, M.D.; Jimenez-Carretero, D.; Sancho-Knapik, D.; Peguero-Pina, J.J.; Gil-Pelegrín, E.; Álvarez-Arenas, T.G. Instantaneous and non-destructive relative water content estimation from deep learning applied to resonant ultrasonic spectra of plant leaves. Plant Methods 2019, 15, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ndlovu, H.S.; Odindi, J.; Sibanda, M.; Mutanga, O.; Clulow, A.; Chimonyo, V.G.P.; Mabhaudhi, T. A Comparative Estimation of Maize Leaf Water Content Using Machine Learning Techniques and Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV)-Based Proximal and Remotely Sensed Data. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Honkavaara, E.; Hayden, M.; Kant, S. UAV remote sensing phenotyping of wheat collection for response to water stress and yield prediction using machine learning. Plant Stress 2024, 12, 100464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.L.; Li, Z.j.; Chen, G.F.; Cui, S.; Wu, Y.; Liu, X.; Meng, W.; Liu, Y.; He, J.; Liu, D.; et al. Soybean (Glycine max L.) Leaf Moisture Estimation Based on Multisource Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Image Feature Fusion. Plants 2024, 13, 1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Li, Z.J.; Tang, Z.J.; Zhang, W.; Li, W.; Liu, Z.; Wu, J.; Liu, S.; Xiang, Y.; Zhang, F. Estimating Soil Moisture Content in Winter Wheat in Southern Xinjiang by Fusing UAV Texture Feature with Novel Three-Dimensional Texture Indexes. Plants 2025, 14, 2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, R.Q.; Lu, J.S.; Xiang, Y.Z.; Zhang, F.; Chen, J.; Tang, Z.; Shi, H.; Wang, X.; Li, W. Estimation of winter canola growth parameter from UAV multi-angular spectral-texture information using stacking-based ensemble learning model. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 222, 109704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, W.G.; Li, C.C.; Cheng, Q.; Ding, F.; Chen, Z. Exploring Multisource Feature Fusion and Stacking Ensemble Learning for Accurate Estimation of Maize Chlorophyll Content Using Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Remote Sensing. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Zhang, J.X.; Bai, Y.; Liang, Z.; Guo, X.; Zhao, Y.; Feng, M.; Xiao, L.; Song, X.; Zhang, M.; et al. Ensemble Learning-Driven and UAV Multispectral Analysis for Estimating the Leaf Nitrogen Content in Winter Wheat. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maimaitijiang, M.; Ghulam, A.; Sidike, P.; Hartling, S.; Maimaitiyiming, M.; Peterson, K.; Shavers, E.; Fishman, J.; Peterson, J.; Kadam, S.; et al. Unmanned Aerial System (UAS)-based phenotyping of soybean using multi-sensor data fusion and extreme learning machine. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2017, 134, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.S.; Liu, R.; Xiao, Y.G.; Cui, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zong, X.; Yang, T. Faba bean above-ground biomass and bean yield estimation based on consumer-grade unmanned aerial vehicle rgb images and ensemble learning. Precis. Agric. 2023, 24, 1439–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Guan, H.D.; Bo, L.Y.; Xu, Z.; Mao, X. Hyperspectral proximal sensing of leaf chlorophyll content of spring maize based on a hybrid of physically based modelling and ensemble stacking. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 208, 107745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Wang, J.J.; Guo, J.L.; Hui, X.; Wang, Y.; Cai, D.; Yan, H. Detecting Water Stress in Winter Wheat Based on Multifeature Fusion from UAV Remote Sensing and Stacking Ensemble Learning Method. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Yin, Q.; Zhang, C.; Shao, L.; Ran, D.; Wang, W.; Zhang, B.; Hu, X. Cross-scale soil moisture content monitoring of winter wheat by integrating UAV and sentinel-1/2 data. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 320, 109831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Yang, G.; Xu, X.; Yang, H.; Feng, H.; Li, Z.; Shen, J.; Lan, Y.; Zhao, C. Combined Multi-Temporal Optical and Radar Parameters for Estimating LAI and Biomass in Winter Wheat Using HJ and RADARSAR-2 Data. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 13251–13272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 11465:1993; Soil Quality—Determination of Dry Matter and Water Content on a Mass Basis—Gravimetric Method. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1993.

- Sun, H.; Feng, M.; Xiao, L.J.; Yang, W.; Ding, G.; Wang, C.; Jia, X.; Wu, G.; Zhang, S. Potential of multivariate statistical technique based on the effective spectra bands to estimate the plant water content of wheat under different irrigation regimes. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 631573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.L.; Nie, C.W.; Su, T.; Xu, X.; Song, Y.; Yin, D.; Liu, S.; Liu, Y.; Bai, Y.; Jia, X.; et al. Evaluating the Canopy Chlorophyll Density of Maize at the Whole Growth Stage Based on Multi-Scale UAV Image Feature Fusion and Machine Learning Methods. Agriculture 2023, 13, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Niu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Han, W.; Li, G.; Tang, J.; Peng, X. Maize canopy temperature extracted from UAV thermal and RGB imagery and its application in water stress monitoring. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Chen, H.; Wang, Z.; Ma, Y. Inversion of soil salinity according to different salinization grades using multi-source remote sensing. Geocarto Int. 2020, 35, 1274–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Han, W.T.; Zhang, H.W.; Cui, J.; Ma, W.; Zhang, L.; Li, G. Estimating soil salinity under sunflower cover in the Hetao Irrigation District based on unmanned aerial vehicle remote sensing. Land Degrad. Dev. 2022, 34, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.Z.; Liu, Z.Y.; Li, S.Q.; Jin, M.; Tang, Z.; Sun, T.; Liu, X.; Li, Z.; Zhang, F.; Xiang, Y. Monitoring Soybean Soil Moisture Content Based on UAV Multispectral and Thermal-Infrared Remote-Sensing Information Fusion. Plants 2024, 13, 2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.Q.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, C.; Vapnik, V. Support-Vector Networks. Mach. Learn. 1995, 20, 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitney, A.W. A Direct Method of Nonparametric Measurement Selection. IEEE Trans. Comput. 1971, 20, 1100–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staiger, D.; Stock, J.H. Instrumental Variables Regression with Weak Instruments. Econometrica 1997, 65, 557–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menze, B.H.; Kelm, B.M.; Masuch, R.; Himmelreich, U.; Bachert, P.; Petrich, W.; Hamprecht, F.A. A comparison of random forest and its Gini importance with standard chemometric methods for the feature selection and classification of spectral data. BMC Bioinform. 2009, 10, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Jin, S.G.; Savi, P.; Gao, Y.; Tang, J.; Chen, Y.; Li, W. GNSS-R Soil Moisture Retrieval Based on a XGboost Machine Learning Aided Method: Performance and Validation. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, L.; Wu, L.F.; Zhang, Z.T.; Fan, J.; Yu, X.; Liu, X.; Yang, Q.; Cui, Y. A gap filling method for daily evapotranspiration of global flux data sets based on deep learning. J. Hydrol. 2024, 641, 131787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoben, W.J.M.; Freer, J.E.; Woods, R.A. Technical note: Inherent benchmark or not? Comparing Nash–Sutcliffe and Kling–Gupta efficiency scores. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2019, 23, 4323–4331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, L.; Zhang, Z.T.; Wu, L.F.; Fan, S.; Yu, X.; Liu, X.; Ba, Y.; Ma, H.; Wang, Y. High uncertainty of evapotranspiration products under extreme climatic conditions. J. Hydrol. 2023, 626, 130332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Zhang, Z.T.; Zhang, J.R.; Yang, X.; Liu, H.; Chen, J.; Ning, J.; Sun, S.; Shi, L. Accurate estimation of winter-wheat leaf water content using continuous wavelet transform-based hyperspectral combined with thermal infrared on a UAV platform. Eur. J. Agron. 2025, 168, 127624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.L.; Yuan, S.Q.; Zhu, J.J.; Tang, Y.; Tang, L. Estimation of Wheat Leaf Water Content Based on UAV Hyper-Spectral Remote Sensing and Machine Learning. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Chen, J.Y.; Bian, J.; Li, Z.; Zhang, W.; Yang, N.; Du, R.; Qian, L.; Geng, H.; Chen, Y.; et al. Enhancing field-scale soil moisture content monitoring using UAV hyperspectral-derived multi-dimensional spectral response indices of crop comprehensive phenotypic traits. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 235, 110399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Vanhard, E.; Corpetti, T.; Houet, T. UAV & satellite synergies for optical remote sensing applications: A literature review. Sci. Remote Sens. 2021, 3, 100019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Zhang, Z.T.; Ding, B.B.; Wang, T.; Zhang, J.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Q.; Zuo, X.; Chen, J.; Cui, N.; et al. Evaluation of winter-wheat water stress with UAV-based multispectral data and ensemble learning method. Plant Soil 2024, 497, 647–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, U.; Alvino, A.; Marino, S. A review of crop water stress assessment using remote sensing. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, K.; Liu, Y.; Fu, M.D.; Li, C.; Zhou, Z.; Meng, H.; Xing, E.; Ren, Y. Combining spectral and texture feature of UAV image with plant height to improve LAI estimation of winter wheat at jointing stage. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1272049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhao, W.W.; Wang, G.; Pereira, P. Afforestation changes the trade-off between soil moisture and plant species diversity in different vegetation zones on the Loess Plateau. Catena 2022, 219, 106583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.N.; Wu, Y.J.; Li, R.P.; Wang, X. Remote sensing-based retrieval of soil moisture content using stacking ensemble learning models. Land Degrad. Dev. 2023, 34, 911–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Zhang, S.W.; Zhang, Y.H.; Hu, R.; Lawi, A.S. Construction of a Winter Wheat Comprehensive Growth Monitoring Index Based on a Fuzzy Degree Comprehensive Evaluation Model of Multispectral UAV Data. Sensors 2023, 23, 8089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, J.; Yang, H.; Yang, G.; Fu, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhou, C. Estimating vertically growing crop above-ground biomass based on UAV remote sensing. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 205, 107627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Han, W.T.; Zhang, H.H.; Niu, X.; Shao, G. Evaluating soil moisture content under maize coverage using UAV multimodal data by machine learning algorithms. J. Hydrol. 2024, 617, 129086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.Y.; Wang, A.C.; Zhang, H.Y.; Zhu, Q.; Zhang, H.; Sun, W.; Niu, Y. Estimating Leaf Chlorophyll Content of Winter Wheat from UAV Multispectral Images Using Machine Learning Algorithms under Different Species, Growth Stages, and Nitrogen Stress Conditions. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, S.; Skidmore, A.K.; Ramoelo, A.; Groen, T.A.; Naeem, M.; Ali, A. Retrieval of leaf water content spanning the visible to thermal infrared spectra. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2014, 93, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.K.; Zhang, S.H.; Wu, K.; Li, Y.; Feng, Z.; Zhang, H.; He, L.; Duan, J.; Wang, Y.; Guo, B.; et al. Comparison of multi-model fusion and transfer strategies for wheat yield comprehensive estimation under lodging stress from lodging parameters and multi-source remote sensing data. J. Integr. Agric. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.J.; Cui, N.B.; Zhang, W.J.; Yang, Y.; Gong, D.; Liu, Q.; Zhao, L.; Xing, L.; He, Q.; Zhu, S.; et al. Estimation of soil moisture in drip-irrigated citrus orchards using multi-modal UAV remote sensing. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 302, 108972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.F.; Li, C.C.; Cheng, Q.; Duan, F.; Zhai, W.; Li, Z.; Mao, B.; Ding, F.; Kuang, X.; Chen, Z. Estimating Maize Crop Height and Aboveground Biomass Using Multi-Source Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Remote Sensing and Optuna-Optimized Ensemble Learning Algorithms. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.H.; Jiao, X.Y.; Liu, Y.D.; Shao, M.; Yu, X.; Bai, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, S.; Tuohuti, N.; Liu, S.; et al. Estimation of soil moisture content under high maize canopy coverage from UAV multimodal data and machine learning. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 264, 107530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Q.; Yu, X.J.; Li, Z.L.; Du, Y.; Ai, Z.; Qian, L.; Huo, X.; Fan, K.; Wang, W.; Hu, X. Estimating Summer Maize Biomass by Integrating UAV Multispectral Imagery with Crop Physiological Parameters. Plants 2024, 13, 3070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt-Walter, P.; Richter, F.; Herbst, M.; Schuldt, B.; Lamersdorf, N.P. Transpiration and water use strategies of a young and a full-grown short rotation coppice differing in canopy cover and leaf area. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2014, 195–196, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.Y.; Li, P.G.; Xie, Y.; Shao, W.; Tian, X. Classification of Paddy Rice Planting Area Through Feature Selection Method Using Sentinel-1/2 Time Series Images. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 8747–8762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.H.; Wei, X.; Zhang, J.N.; Chen, Z.L.; Jin, J. Spatial-spectral feature mining in hyperspectral corn leaf venation structure and its application in nitrogen content estimation. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 227, 109495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| VIs | Formula |

|---|---|

| NDVI | (NIR − R)/(NIR + R) |

| NDWI | (NIR − G)/(NIR + G) |

| TSAVI | (1.2(NIR − 1.2R − 0.05))/((1.2NIR) + Red + 1.2 × 0.05) |

| PDI | (NIR+Red)/1.414 |

| SAVI | 1.5(NIR − R)/(NIR + R + 0.5) |

| GNDVI | (NIR − Green)/(NIR + Green) |

| MSR | ((NIR/R) − 1)/sqrt((NIR/R) + 1) |

| RDVI | (NIR − R)/sqrt(NIR + R) |

| MCARI | ((Red edge − R) − 0.2(Red edge-G)) × (Red edge/R) |

| OSAVI | 1.16(NIR − R)/(NIR + R + 0.16) |

| DVI | NIR − R |

| SAVI2 | 1.5(NIR − R)/(NIR + R + 0.5) |

| TVI | 0.5(120(NIR − G)-200(R − G)) |

| RVI1 | NIR/G |

| RVI2 | NIR/R |

| GI | (G − R)/(G + R) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yu, X.; Qian, L.; Chen, K.; Ye, S.; Yin, Q.; Shao, L.; Ran, D.; Wang, W.; Zhang, B.; Hu, X. Estimating Winter Wheat Leaf Water Content by Combining UAV Spectral and Texture Features with Stacking Ensemble Learning. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2610. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112610

Yu X, Qian L, Chen K, Ye S, Yin Q, Shao L, Ran D, Wang W, Zhang B, Hu X. Estimating Winter Wheat Leaf Water Content by Combining UAV Spectral and Texture Features with Stacking Ensemble Learning. Agronomy. 2025; 15(11):2610. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112610

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Xingjiao, Long Qian, Kainan Chen, Sumeng Ye, Qi Yin, Lingjia Shao, Danjie Ran, Wen’e Wang, Baozhong Zhang, and Xiaotao Hu. 2025. "Estimating Winter Wheat Leaf Water Content by Combining UAV Spectral and Texture Features with Stacking Ensemble Learning" Agronomy 15, no. 11: 2610. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112610

APA StyleYu, X., Qian, L., Chen, K., Ye, S., Yin, Q., Shao, L., Ran, D., Wang, W., Zhang, B., & Hu, X. (2025). Estimating Winter Wheat Leaf Water Content by Combining UAV Spectral and Texture Features with Stacking Ensemble Learning. Agronomy, 15(11), 2610. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112610