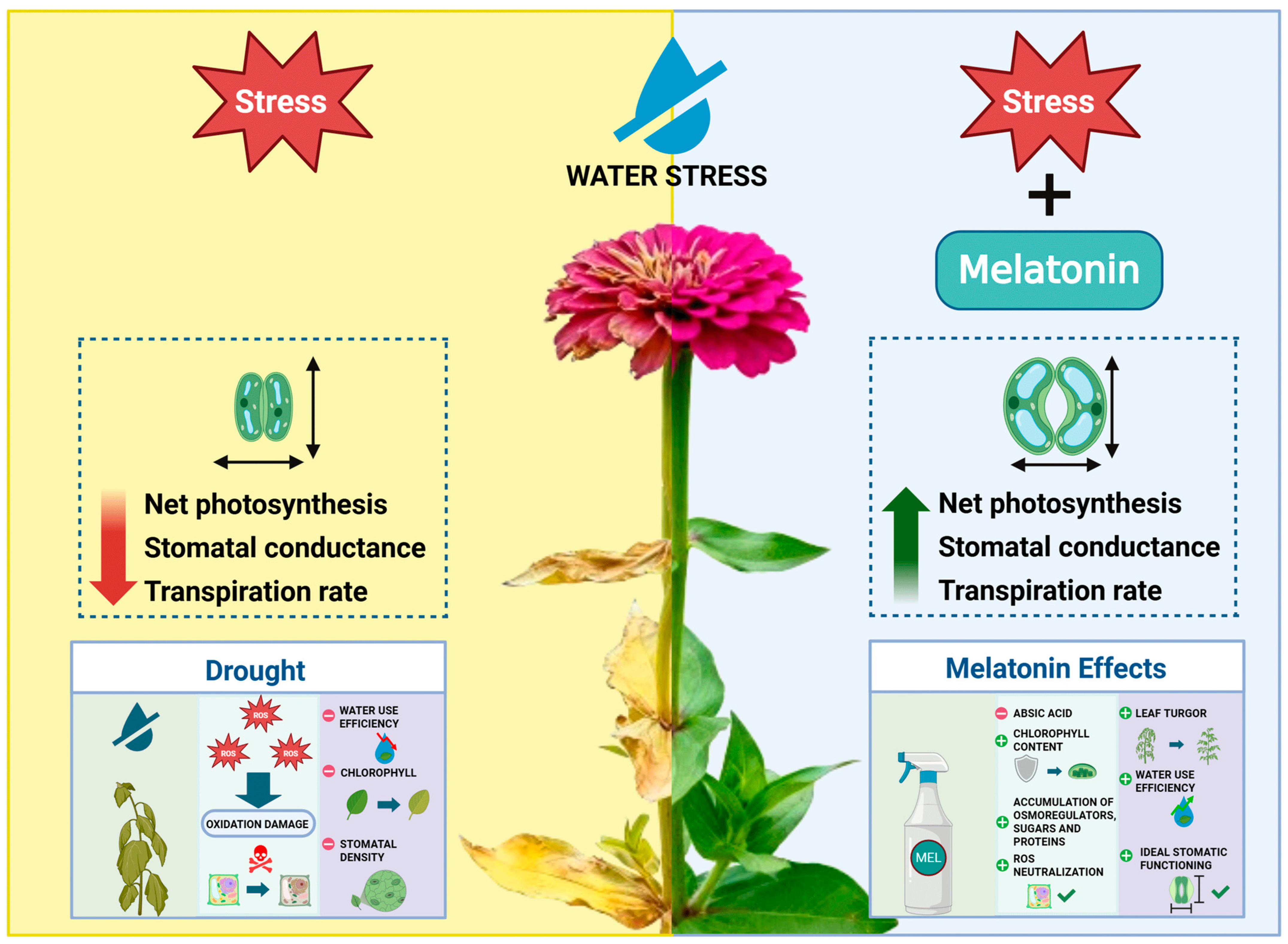

Melatonin Improves Drought Tolerance in Zinnia elegans Through Osmotic Adjustment and Stomatal Regulation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

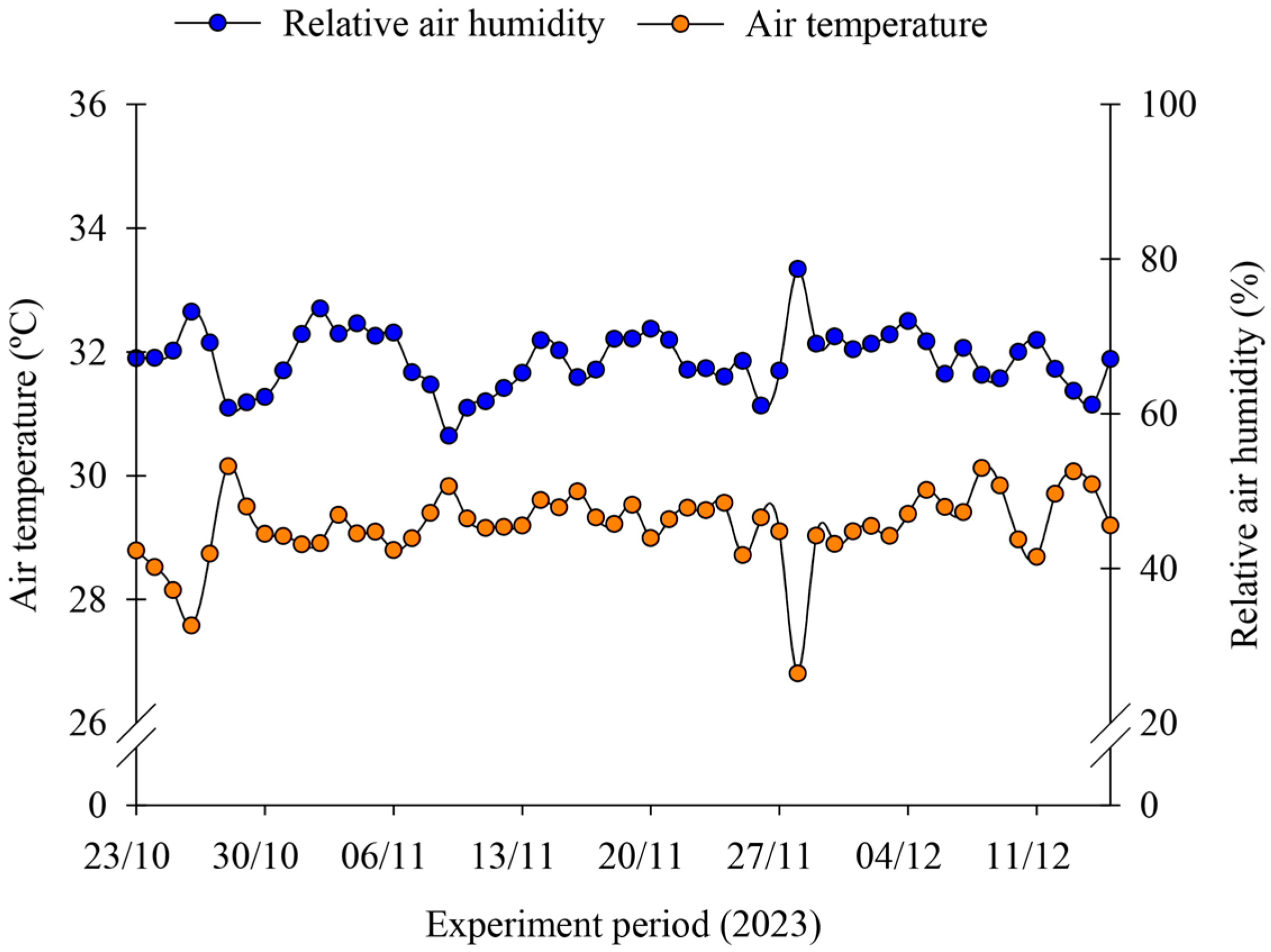

2.1. Experiment Site and Climatic Conditions

2.2. Plant Material and Design

2.3. Variables Analyzed

2.3.1. Gas Exchange

2.3.2. Photosynthetic Pigments

2.3.3. Chlorophyll a Fluorescence

2.3.4. Morphofunctional Attributes and Relative Water Content

2.3.5. Electrolyte Leakage

2.3.6. Stomatal Traits

2.3.7. Biochemical Traits

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

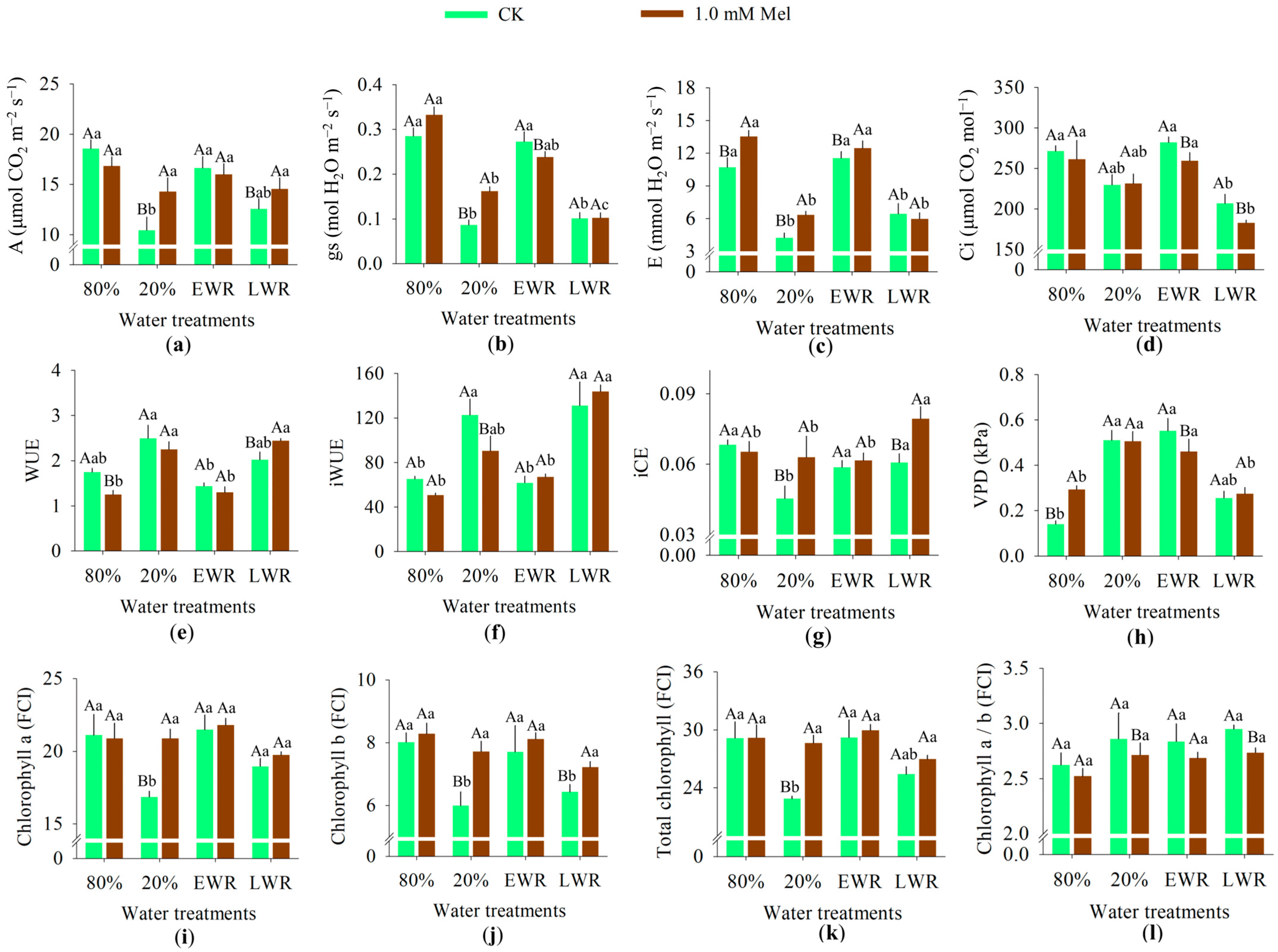

3.1. Gas Exchange

3.2. Photosynthetic Pigments

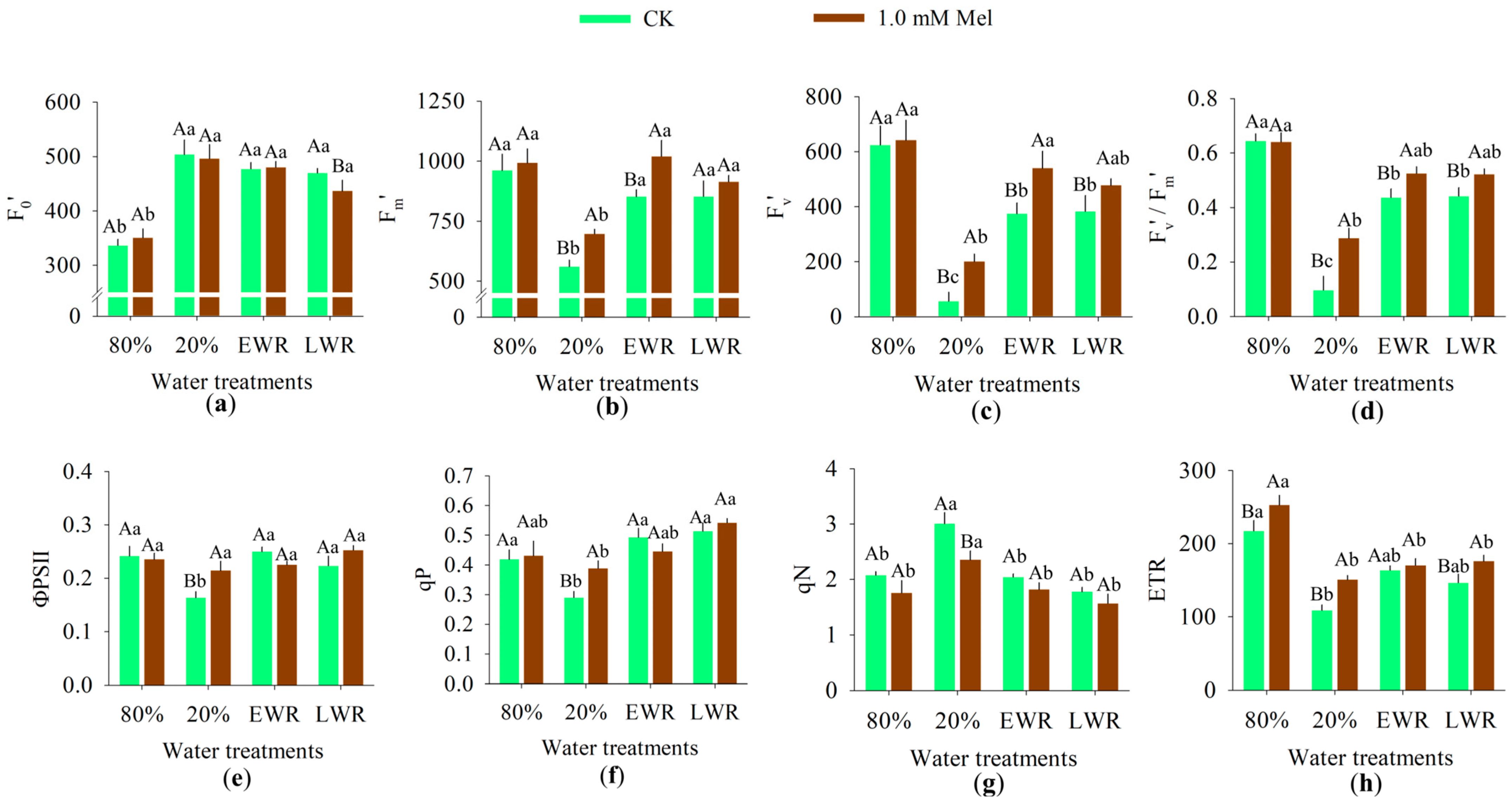

3.3. Chlorophyll a Fluorescence

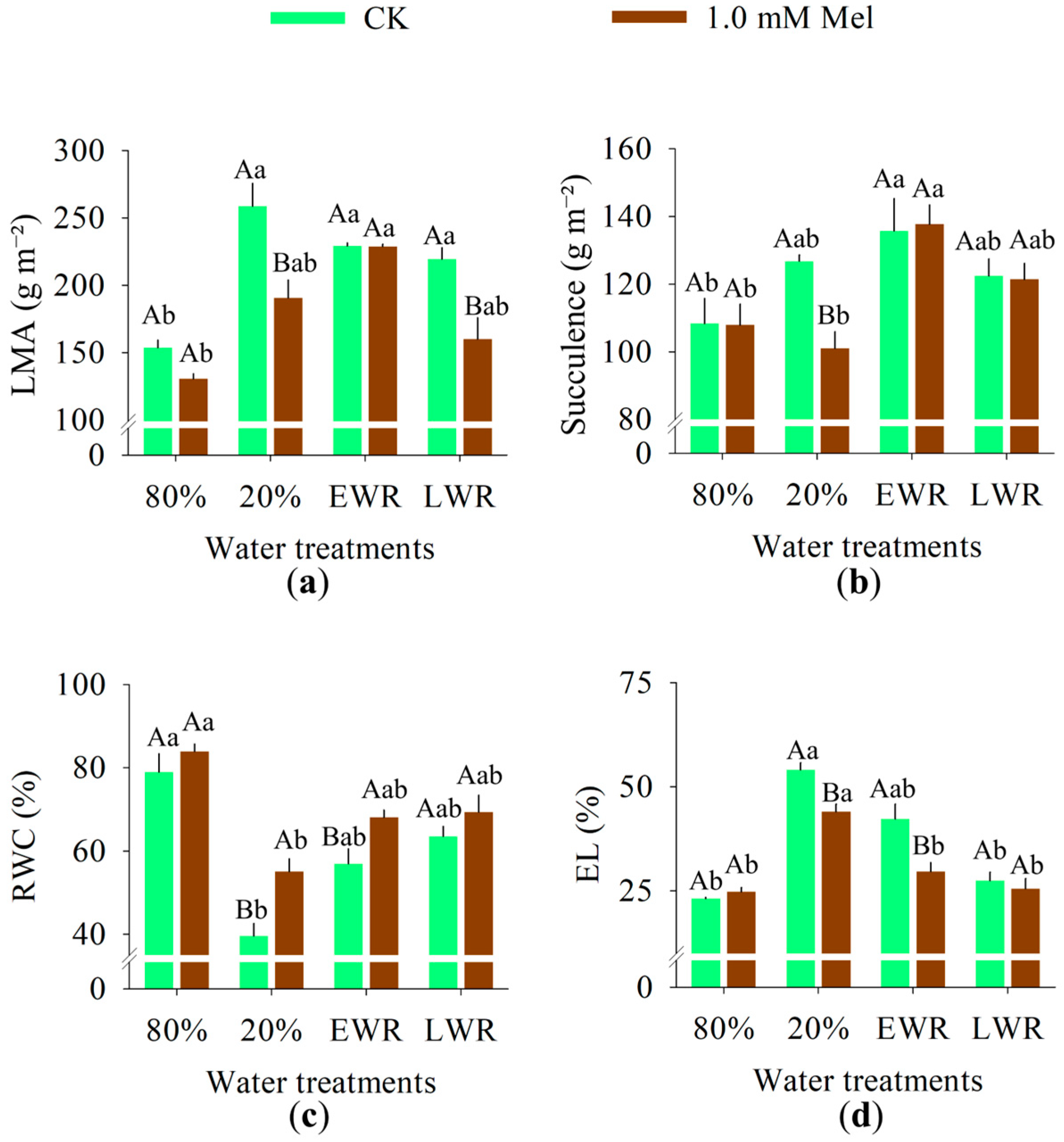

3.4. Morphofunctional Aspects, Water Responses and Membrane Integrity

3.5. Stomatal Traits

3.6. Biochemical Traits

3.7. Principal Component Analysis and Pearson Correlation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Raihan, A. A review of the global climate change impacts, adaptation strategies, and mitigation options in the socio-economic and environmental sectors. J. Environ. Sci. Econ. 2023, 2, 36–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsisi, M.; Elshiekh, M.; Sabry, N.; Aziz, M.; Attia, K.; Islam, F.; Chen, J.; Abdelrahman, M. The genetic orchestra of salicylic acid in plant resilience to climate change induced abiotic stress: Critical review. Stress Biol. 2024, 4, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Li, X.; Zhao, W.; Hou, X.; Dong, S. Current views of drought research: Experimental methods, adaptation mechanisms and regulatory strategies. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1371895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cataldo, E.; Fucile, M.; Manzi, D.; Masini, C.M.; Doni, S.; Mattii, G.B. Sustainable soil management: Effects of clinoptilolite and organic compost soil application on eco-physiology, quercitin, and hydroxylated, methoxylated anthocyanins on Vitis vinifera. Plants 2023, 12, 708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezende, L.F.; Alves, L.; Barbosa, A.A.; Sales, A.T.; Pedra, G.U.; Menezes, R.S.C.; Arcoverde, G.F.; Ometto, J.P. Greening and Water Use Efficiency during a period of high frequency of droughts in the Brazilian semi-arid. Front. Water 2023, 5, 1295286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marengo, J.A.; Galdos, M.V.; Challinor, A.; Cunha, A.P.; Marin, F.R.; Vianna, M.d.S.; Alvala, R.C.S.; Alves, L.M.; Moraes, O.L.; Bender, F. Drought in Northeast Brazil: A review of agricultural and policy adaptation options for food security. Clim. Resil. Sustain. 2022, 1, e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, H.A. Understanding the rapid increase in drought stress and its connections with climate desertification since the early 1990s over the Brazilian semi-arid region. J. Arid Environ. 2024, 222, 105142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wang, J.; Hui, W.; Zhao, F.; Wang, P.; Su, C.; Gong, W. Physiology of plant responses to water stress and related genes: A review. Forests 2022, 13, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, C.; Chen, H.Y.H.; Ruan, H. Response of plants to water stress: A meta-analysis. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.-J.; Sun, Y.; Kopp, K.; Oki, L.; Jones, S.B.; Hipps, L. Effects of water availability on leaf trichome density and plant growth and development of Shepherdia× utahensis. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 855858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caine, R.S.; Yin, X.; Sloan, J.; Harrison, E.L.; Mohammed, U.; Fulton, T.; Biswal, A.K.; Dionora, J.; Chater, C.C.; Coe, R.A. Rice with reduced stomatal density conserves water and has improved drought tolerance under future climate conditions. New Phytol. 2019, 221, 371–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitaloka, M.K.; Caine, R.S.; Hepworth, C.; Harrison, E.L.; Sloan, J.; Chutteang, C.; Phunthong, C.; Nongngok, R.; Toojinda, T.; Ruengphayak, S. Induced genetic variations in stomatal density and size of rice strongly affects water use efficiency and responses to drought stresses. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 801706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolino, L.T.; Caine, R.S.; Gray, J.E. Impact of stomatal density and morphology on water-use efficiency in a changing world. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cataldo, E.C.; Salvi, L.S.; Paoli, F.P.; Fucile, M.F.; Masciandaro, G.M.; Manzi, D.M.; Masini, C.M.M.; Mattii, G.B.M. Effects of natural clinoptilolite on physiology, water stress, sugar, and anthocyanin content in Sanforte (Vitis vinifera L.) young vineyard. J. Agric. Sci. 2021, 159, 488–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, F.; Kuromori, T.; Urano, K.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K.; Shinozaki, K. Drought stress responses and resistance in plants: From cellular responses to long-distance intercellular communication. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 556972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asargew, M.F.; Masutomi, Y.; Kobayashi, K.; Aono, M. Water stress changes the relationship between photosynthesis and stomatal conductance. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 907, 167886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.J.; Bi, M.H.; Nie, Z.F.; Jiang, H.; Liu, X.D.; Fang, X.W.; Brodribb, T.J. Evolution of stomatal closure to optimize water-use efficiency in response to dehydration in ferns and seed plants. New Phytol. 2021, 230, 2001–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seleiman, M.F.; Al-Suhaibani, N.; Ali, N.; Akmal, M.; Alotaibi, M.; Refay, Y.; Dindaroglu, T.; Abdul-Wajid, H.H.; Battaglia, M.L. Drought stress impacts on plants and different approaches to alleviate its adverse effects. Plants 2021, 10, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilyas, M.; Nisar, M.; Khan, N.; Hazrat, A.; Khan, A.H.; Hayat, K.; Fahad, S.; Khan, A.; Ullah, A. Drought tolerance strategies in plants: A mechanistic approach. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2021, 40, 926–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Lu, M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Chen, S. Response mechanism of plants to drought stress. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mircea, D.-M.; Boscaiu, M.; Sestras, R.E.; Sestras, A.F.; Vicente, O. Abiotic stress tolerance and invasive potential of ornamental plants in the Mediterranean area: Implications for sustainable landscaping. Agronomy 2024, 15, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toscano, S.; Ferrante, A.; Romano, D. Response of Mediterranean ornamental plants to drought stress. Horticulturae 2019, 5, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Liu, X.; Xu, M.; Ying, M.; Fu, J.; Zhang, C. Germplasm resource and genetic breeding of Zinnia: A review. Ornam. Plant Res. 2025, 5, e015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, H.; Sun, Y.; Müller, R.; Liu, F. Effects of soil water deficits on three genotypes of potted Campanula medium plants during bud formation stage. Sci. Hortic. 2014, 166, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caser, M.; Lovisolo, C.; Scariot, V. The influence of water stress on growth, ecophysiology and ornamental quality of potted Primula vulgaris ‘Heidy’plants. New insights to increase water use efficiency in plant production. Plant Growth Regul. 2017, 83, 361–373. [Google Scholar]

- Toscano, S.; Ferrante, A.; Tribulato, A.; Romano, D. Leaf physiological and anatomical responses of Lantana and Ligustrum species under different water availability. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 127, 380–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, P.U.; Lima, L.K.S.; Soares, T.L.; de Jesus, O.N.; Coelho Filho, M.A.; Girardi, E.A. Biometric, physiological and anatomical responses of Passiflora spp. to controlled water deficit. Sci. Hortic. 2018, 229, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, M.; Petropoulos, S.A.; Cirillo, C.; Rouphael, Y. Biochemical, physiological, and molecular aspects of ornamental plants adaptation to deficit irrigation. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qayyum, M.M.; Hussain, I.; Ali, H.; Saeed, T.; Umar, M.; Imtiaz, A.; Noor, S.; Ali, I.; Naz, R.M.M.; Ali, K. Effect of compost on the growth, flowering attributes, and vase life of different varieties of zinnia (Zinnia elegans). J. Appl. Res. Plant Sci. 2024, 5, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, R.; Pêgo, R.G.; da Cruz, E.S.; Bueno, M.M.; de Carvalho, D.F. Postharvest quality of cut zinnia flowers cultivated under different irrigation levels and growing seasons. J. Agric. Stud. 2021, 9, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, R.d.C.F.; Pêgo, R.G.; Cruz, E.S.d.; Abreu, J.F.G.; Carvalho, D.F.d. Production and quality of zinnia under different growing seasons and irrigation levels. Ciência E Agrotecnologia 2021, 45, e033720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toscano, S.; Romano, D. Morphological, physiological, and biochemical responses of zinnia to drought stress. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, M.; Younis, A.; Raheel, M.; Khalid, I.; Abbas, H.T.; Ashraf, W.; Mihoub, A.; Radicetti, E.; Saeed, M.F.; Ali, S. Morpho-physiological and enzymatic responses of zinnia (Zinnia elegans L.) to different metal hoarded wastewaters. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2024, 24, 2910–2923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hada, W. Expression of Genes Involved in Phenolics and Lignin Biosynthesis in Zinnia elegans under Saline Stress. J. Sib. Fed. Univ.-Biol. 2023, 16, 193–205. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, M.U.; Mahmood, A.; Awan, M.I.; Maqbool, R.; Aamer, M.; Alhaithloul, H.A.S.; Huang, G.; Skalicky, M.; Brestic, M.; Pandey, S. Melatonin-induced protection against plant abiotic stress: Mechanisms and prospects. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 902694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, M.; Younis, A.; Jamal, A.; Alshaharni, M.O.; Algopishi, U.B.; Al-Andal, A.; Sajid, M.; Naeem, M.; Khan, J.A.; Radicetti, E. Melatonin induces drought stress tolerance by regulating the physiological mechanisms, antioxidant enzymes, and leaf structural modifications in Rosa centifolia L. Heliyon 2025, 11, e41236. Heliyon 2025, 11, e41236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdoli, M.; Amerian, M.R.; Heidari, M.; Ebrahimi, A. Synergistic effects of melatonin and 24-epibrassinolide on chickpea water deficit tolerance. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustafa-Farag, M.; Elkelish, A.; Dafea, M.; Khan, M.; Arnao, M.B.; Abdelhamid, M.T.; El-Ezz, A.A.; Almoneafy, A.; Mahmoud, A.; Awad, M. Role of melatonin in plant tolerance to soil stressors: Salinity, pH and heavy metals. Molecules 2020, 25, 5359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvares, C.A.; Stape, J.L.; Sentelhas, P.C.; Gonçalves, J.L.d.M.; Sparovek, G. Köppen’s climate classification map for Brazil. Meteorol. Z. 2013, 22, 711–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, P.H.d.A.; Sá, S.A.d.; Ribeiro, J.E.d.S.; da Silva, J.P.P.; Lima, F.F.d.; Silva, I.; Silveira, L.M.d.; Barros Júnior, A.P. Exogenous application of melatonin mitigates salt stress in soybean. Rev. Caatinga 2025, 38, e12698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, P.H.d.A.; Lima, F.F.d.; Silva, J.P.P.d.; Silva, I.B.M.; Silva, T.I.d.; Silveira, L.M.d.; Barros, A.P.; Ribeiro, J.E.d.S. Growth and water status of cowpea under salt stress and exogenous melatonin application. Rev. Bras. De Eng. Agrícola E Ambient. 2025, 29, e293009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coêlho, E.d.S.; Ribeiro, J.E.d.S.; Oliveira, P.H.d.A.; da Silva, E.F.; da Silva, A.G.C.; de Oliveira, A.K.S.; dos Santos, G.L.; da Silva, T.I.; Rodriguez, R.M.; Bezerra, A.L. Application of Biostimulants Modulates Photosynthesis Responses, and Chlorophyll Fluorescence Under Salt Stress in Radish. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2025, 44, 5063–5078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, J.E.d.S.; da Silva, A.G.C.; Coêlho, E.d.S.; Oliveira, P.H.d.A.; Silva, E.F.d.; de Oliveira, A.K.S.; Santos, G.L.d.; Lima, J.V.L.; Silva, T.I.d.; Silveira, L.M.d. Melatonin mitigates salt stress effects on the growth and production aspects of radish. Rev. Bras. De Eng. Agrícola E Ambient. 2024, 28, e279006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girardi, L.B.; Peiter, M.X.; Bellé, R.A.; Robaina, A.D.; Torres, R.R.; Kirchner, J.H.; Ben, L.H.B. Evapotranspiration and crop coefficients of potted Alstroemeria × hybrida grown in greenhouse. IRRIGA 2016, 24, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witkowski, E.T.F.; Lamont, B.B. Leaf specific mass confounds leaf density and thickness. Oecologia 1991, 88, 486–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantovani, A. A method to improve leaf succulence quantification. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 1999, 41, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrs, H.D.; Weatherley, P.E. A re-examination of the relative turgidity technique for estimating water deficits in leaves. Aust. J. Biol. Sci. 1962, 15, 413–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajji, M.; Kinet, J.-M.; Lutts, S. The use of the electrolyte leakage method for assessing cell membrane stability as a water stress tolerance test in durum wheat. Plant Growth Regul. 2002, 36, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yemm, E.W.; Willis, A.J. The estimation of carbohydrates in plant extracts by anthrone. Biochem. J. 1954, 57, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.L. Use of dinitrosalicylic acid reagent for determination of reducing sugar. Anal. Chem. 1959, 31, 426–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, L.S.; Waldren, R.P.A.; Teare, I.D. Rapid determination of free proline for water-stress studies. Plant Soil 1973, 39, 205–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R Development Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Franceschi, E.; Moser-Reischl, A.; Honold, M.; Rahman, M.A.; Pretzsch, H.; Pauleit, S.; Rötzer, T. Urban environment, drought events and climate change strongly affect the growth of common urban tree species in a temperate city. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 88, 128083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detti, C.; Gori, A.; Azzini, L.; Nicese, F.P.; Alderotti, F.; Piccolo, E.L.; Stella, C.; Ferrini, F.; Brunetti, C. Drought tolerance and recovery capacity of two ornamental shrubs: Combining physiological and biochemical analyses with online leaf water status monitoring for the application in urban settings. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 216, 109208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Zhao, Y.; Qin, X.; Ding, C.; Chen, Y.; Tang, Z.; Huang, Y.; Reiter, R.J.; Yuan, S.; Yuan, M. New insights into the role of melatonin in photosynthesis. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 5918–5927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chachar, S.; Ahmed, N.; Hu, X. Drought-induced aesthetic decline and ecological impacts on ornamentals: Mechanisms of damage and innovative strategies for mitigation. Plant Biol. 2025, 27, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Li, C.; Gao, T.; Zhang, Z.; Liang, B.; Lv, Z.; Zou, Y.; Ma, F. Melatonin increases the performance of Malus hupehensis after UV-B exposure. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2019, 139, 630–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; Li, J.; Harmens, H.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, C. Melatonin enhances drought resistance by regulating leaf stomatal behaviour, root growth and catalase activity in two contrasting rapeseed (Brassica napus L.) genotypes. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 149, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, M.H.; Alamri, S.; Khan, M.N.; Corpas, F.J.; Al-Amri, A.A.; Alsubaie, Q.D.; Ali, H.M.; Kalaji, H.M.; Ahmad, P. Melatonin and calcium function synergistically to promote the resilience through ROS metabolism under arsenic-induced stress. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 398, 122882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.N.; Zhang, J.; Luo, T.; Liu, J.; Rizwan, M.; Fahad, S.; Xu, Z.; Hu, L. Seed priming with melatonin coping drought stress in rapeseed by regulating reactive oxygen species detoxification: Antioxidant defense system, osmotic adjustment, stomatal traits and chloroplast ultrastructure perseveration. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 140, 111597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leghari, S.J.; Wahocho, N.A.; Laghari, G.M.; HafeezLaghari, A.; MustafaBhabhan, G.; HussainTalpur, K.; Bhutto, T.A.; Wahocho, S.A.; Lashari, A.A. Role of nitrogen for plant growth and development: A review. Adv. Environ. Biol. 2016, 10, 209–219. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.J.; Zhang, N.A.; Yang, R.C.; Wang, L.; Sun, Q.Q.; Li, D.B.; Cao, Y.Y.; Weeda, S.; Zhao, B.; Ren, S. Melatonin promotes seed germination under high salinity by regulating antioxidant systems, ABA and GA 4 interaction in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.). J. Pineal Res. 2014, 57, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajora, N.; Vats, S.; Raturi, G.; Thakral, V.; Kaur, S.; Rachappanavar, V.; Kumar, M.; Kesarwani, A.K.; Sonah, H.; Sharma, T.R. Seed priming with melatonin: A promising approach to combat abiotic stress in plants. Plant Stress 2022, 4, 100071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahan, E.; Sharwood, R.E.; Tissue, D.T. Effects of leaf age during drought and recovery on photosynthesis, mesophyll conductance and leaf anatomy in wheat leaves. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1091418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Li, Y.; Hu, L.; Zhang, J.; Yue, H.; Yang, S.; Liu, Y.; Gong, X.; Ma, F. Overexpression of MdASMT9, an N-acetylserotonin methyltransferase gene, increases melatonin biosynthesis and improves water-use efficiency in transgenic apple. Tree Physiol. 2022, 42, 1114–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, E.L.; Arce Cubas, L.; Gray, J.E.; Hepworth, C. The influence of stomatal morphology and distribution on photosynthetic gas exchange. Plant J. 2020, 101, 768–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Li, P.; Liang, Y.; Si, Z.; Ma, S.; Gao, Y. Effects of exogenous melatonin on wheat quality under drought stress and rehydration. Plant Growth Regul. 2024, 103, 471–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, M.; Shojaeiyan, A.; Mokhtassi-Bidgoli, A.; Tamadoni-Saray, M. Melatonin Enhances Drought Tolerance and Recovery Capability in Two Contrasting Fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum L.) Landraces Through Improved Photosynthetic Apparatus Protection and Carboxylation Efficiency. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2024, 43, 4588–4607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Hu, T.; Huo, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, L.; Yan, R. Effects of exogenous melatonin on chrysanthemum physiological characteristics and photosynthesis under drought stress. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Gong, X.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, J.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y. Exogenous melatonin improves physiological characteristics and promotes growth of strawberry seedlings under cadmium stress. Hortic. Plant J. 2021, 7, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnao, M.B.; Hernández-Ruiz, J. Melatonin in flowering, fruit set and fruit ripening. Plant Reprod. 2020, 33, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Guo, Y.; Lan, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Ahammed, G.J.; Chang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, C.; Zhang, X. Melatonin antagonizes ABA action to promote seed germination by regulating Ca2+ efflux and H2O2 accumulation. Plant Sci. 2021, 303, 110761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cirillo, C.; Rouphael, Y.; Caputo, R.; Raimondi, G.; De Pascale, S. The influence of deficit irrigation on growth, ornamental quality, and water use efficiency of three potted Bougainvillea genotypes grown in two shapes. HortScience 2014, 49, 1284–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Gong, L.; Liu, X.; Hu, J.; Lu, X.; Xu, J. Genome-Wide Profiling of the Genes Related to Leaf Discoloration in Zelkova schneideriana. Forests 2024, 15, 1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Zhou, G.; He, Q.; Zhou, H. Stomatal limitations to photosynthesis and their critical water conditions in different growth stages of maize under water stress. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 241, 106330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-E.; Cui, J.-M.; Su, Y.-Q.; Zhang, C.-M.; Ma, J.; Zhang, Z.-W.; Yuan, M.; Liu, W.-J.; Zhang, H.-Y.; Yuan, S. Comparison of phosphorylation and assembly of photosystem complexes and redox homeostasis in two wheat cultivars with different drought resistance. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 12718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Song, X.-F.; Mao, H.-T.; Li, S.-Q.; Gan, J.-Y.; Yuan, M.; Zhang, Z.-W.; Yuan, S.; Zhang, H.-Y.; Su, Y.-Q. Exogenous melatonin improved photosynthetic efficiency of photosystem II by reversible phosphorylation of thylakoid proteins in wheat under osmotic stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 966181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Feng, Y.; Jing, T.; Liu, X.; Ai, X.; Bi, H. Melatonin promotes the chilling tolerance of cucumber seedlings by regulating antioxidant system and relieving photoinhibition. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 789617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zhao, H.; Cao, K.; Hu, L.; Du, T.; Baluška, F.; Zou, Z. Beneficial roles of melatonin on redox regulation of photosynthetic electron transport and synthesis of D1 protein in tomato seedlings under salt stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, I.R.; Rocha, G.H.d.; Pereira, E.G. Photosynthetic adjustments and proline concentration are probably linked to stress memory in soybean exposed to recurrent drought. Ciência E Agrotecnologia 2023, 47, e015322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Chen, Y.-E.; Zhao, Y.-Q.; Ding, C.-B.; Liao, J.-Q.; Hu, C.; Zhou, L.-J.; Zhang, Z.-W.; Yuan, S.; Yuan, M. Exogenous melatonin alleviates oxidative damages and protects photosystem II in maize seedlings under drought stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jardim, A.M.d.R.F.; Santos, H.R.B.; Alves, H.K.M.N.; Ferreira-Silva, S.L.; de Souza, L.S.B.; Júnior, G.d.N.A.; de Sá Souza, M.; de Araújo, G.G.L.; de Souza, C.A.A.; da Silva, T.G.F. Genotypic differences relative photochemical activity, inorganic and organic solutes and yield performance in clones of the forage cactus under semi-arid environment. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 162, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.E.; Mao, J.J.; Sun, L.Q.; Huang, B.; Ding, C.B.; Gu, Y.; Liao, J.Q.; Hu, C.; Zhang, Z.W.; Yuan, S. Exogenous melatonin enhances salt stress tolerance in maize seedlings by improving antioxidant and photosynthetic capacity. Physiol. Plant. 2018, 164, 349–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guizani, A.; Askri, H.; Amenta, M.L.; Defez, R.; Babay, E.; Bianco, C.; Rapaná, N.; Finetti-Sialer, M.; Gharbi, F. Drought responsiveness in six wheat genotypes: Identification of stress resistance indicators. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1232583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Forn, D.; Peguero-Pina, J.J.; Ferrio, J.P.; García-Plazaola, J.I.; Martín-Sánchez, R.; Niinemets, Ü.; Sancho-Knapik, D.; Gil-Pelegrín, E. Cell-level anatomy explains leaf age-dependent declines in mesophyll conductance and photosynthetic capacity in the evergreen Mediterranean oak Quercus ilex subsp. rotundifolia. Tree Physiol. 2022, 42, 1988–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, M.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, G.; Xiong, Z.; Peng, S.; Li, Y. High leaf mass per area Oryza genotypes invest more leaf mass to cell wall and show a low mesophyll conductance. AoB Plants 2020, 12, plaa028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, T.; Xu, H.; Wei, Q.; Zeng, H.; Ni, H.; Li, S. Multiple functions of exogenous melatonin in cucumber seed germination, seedling establishment, and alkali stress resistance. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moustafa-Farag, M.; Mahmoud, A.; Arnao, M.B.; Sheteiwy, M.S.; Dafea, M.; Soltan, M.; Elkelish, A.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Ai, S. Melatonin-induced water stress tolerance in plants: Recent advances. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.; Chattopadhyay, A.; Bandyopadhyay, D. Melatonin and biological membrane bilayers: A never ending amity. Melatonin Res. 2021, 4, 232–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmir, M.; Naderi Noreini, S.; Ghafarizadeh, A.; Faraji, T.; Asali, Z. Ameliorative effect of melatonin on apoptosis, DNA fragmentation, membrane integrity and lipid peroxidation of spermatozoa in the idiopathic asthenoteratospermic men: In vitro. Andrologia 2021, 53, e13944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Li, C.; Kong, D.; Guo, F.; Wei, H. Light-mediated signaling and metabolic changes coordinate stomatal opening and closure. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 601478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badigannavar, A.; Teme, N.; de Oliveira, A.C.; Li, G.; Vaksmann, M.; Viana, V.E.; Ganapathi, T.R.; Sarsu, F. Physiological, genetic and molecular basis of drought resilience in sorghum [Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench]. Indian J. Plant Physiol. 2018, 23, 670–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargunam, S.; Roy, R.; Amisha, S.H.; Shetty, D.; Babu, V.S. Deciphering regulatory role of melatonin in foliar nastic movements of Portulaca oleracea: Visual insights from histology and anatomy. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2025, 44, 2058–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, O.A.; Labulo, A.H.; Adejayan, M.T.; Adeleke, E.A.; Adeniyi, I.M.; Terna, A.D. Anatomical adaptation of water-stressed Eugenia uniflora using green synthesized silver nanoparticles and melatonin. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2023, 86, 648–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J.W.; Harris, B.J.; Hetherington, A.J.; Hurtado-Castano, N.; Brench, R.A.; Casson, S.; Williams, T.A.; Gray, J.E.; Hetherington, A.M. The origin and evolution of stomata. Curr. Biol. 2022, 32, R539–R553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hõrak, H.; Kollist, H.; Merilo, E. Fern stomatal responses to ABA and CO2 depend on species and growth conditions. Plant Physiol. 2017, 174, 672–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plackett, A.R.G.; Emms, D.M.; Kelly, S.; Hetherington, A.M.; Langdale, J.A. Conditional stomatal closure in a fern shares molecular features with flowering plant active stomatal responses. Curr. Biol. 2021, 31, 4560–4570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driesen, E.; De Proft, M.; Saeys, W. Drought stress triggers alterations of adaxial and abaxial stomatal development in basil leaves increasing water-use efficiency. Hortic. Res. 2023, 10, uhad075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, T.A.; Saleem, M.; Fariduddin, Q. Melatonin influences stomatal behavior, root morphology, cell viability, photosynthetic responses, fruit yield, and fruit quality of tomato plants exposed to salt stress. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2023, 42, 2408–2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.F.; Xu, T.F.; Wang, Z.Z.; Fang, Y.L.; Xi, Z.M.; Zhang, Z.W. The ameliorative effects of exogenous melatonin on grape cuttings under water-deficient stress: Antioxidant metabolites, leaf anatomy, and chloroplast morphology. J. Pineal Res. 2014, 57, 200–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Li, D.X.; Zhang, J.R.; Shan, C.; Rengel, Z.; Song, Z.B.; Chen, Q. Phytomelatonin receptor PMTR 1-mediated signaling regulates stomatal closure in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Pineal Res. 2018, 65, e12500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shomali, A.; Aliniaeifard, S.; Didaran, F.; Lotfi, M.; Mohammadian, M.; Seif, M.; Strobel, W.R.; Sierka, E.; Kalaji, H.M. Synergistic effects of melatonin and gamma-aminobutyric acid on protection of photosynthesis system in response to multiple abiotic stressors. Cells 2021, 10, 1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, S.; Muhammad, I.; Wang, G.Y.; Zeeshan, M.; Yang, L.; Ali, I.; Zhou, X.B. Ameliorative effect of melatonin improves drought tolerance by regulating growth, photosynthetic traits and leaf ultrastructure of maize seedlings. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumithrakamatchi, A.K.; Alagarswamy, S.; Anitha, K.; Djanaguiraman, M.; Kalarani, M.K.; Swarnapriya, R.; Marimuthu, S.; Vellaikumar, S.; Kanagarajan, S. Melatonin imparts tolerance to combined drought and high-temperature stresses in tomato through osmotic adjustment and ABA accumulation. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1382914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.; Zeng, J.; Lu, D.; Yue, L.; Zhong, M.; Kang, Y.; Guo, J.; Yang, X. Melatonin maintains postharvest quality by modulating the metabolisms of cell wall and sugar in flowering Chinese cabbage. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 5396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobylińska, A.; Borek, S.; Posmyk, M.M. Melatonin redirects carbohydrates metabolism during sugar starvation in plant cells. J. Pineal Res. 2018, 64, e12466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sher, A.; Hassan, M.U.; Sattar, A.; Ul-Allah, S.; Ijaz, M.; Hayyat, Z.; Bibi, Y.; Hussain, M.; Qayyum, A. Exogenous application of melatonin alleviates the drought stress by regulating the antioxidant systems and sugar contents in sorghum seedlings. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2023, 107, 104620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Feng, Y.; Chen, S.; Pan, Y.; Xu, J.; Yu, W.; Li, C. Revealing the significance of melatonin in postharvest quality of tomato fruit, especially in sugar metabolism and transport. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2026, 231, 113909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.-F.; Zhao, B.; Huang, C.-C.; Chen, Z.-W.; Zhao, T.; Liu, H.-R.; Hu, G.-J.; Shangguan, X.-X.; Shan, C.-M.; Wang, L.-J. The miR319-targeted GhTCP4 promotes the transition from cell elongation to wall thickening in cotton fiber. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 1063–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Min, W.; Akhtar, M.; Lu, X.; Bai, X.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, L.; Li, P. Melatonin enhances drought tolerance in rice seedlings by modulating antioxidant systems, osmoregulation, and corresponding gene expression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, G.; Sun, F.; Gao, X.; Xie, K.; Zhang, C.; Liu, S.; Xi, Y. Proteomic analysis of melatonin-mediated osmotic tolerance by improving energy metabolism and autophagy in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Planta 2018, 248, 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Coêlho, E.d.S.; Ribeiro, J.E.d.S.; Silva, E.F.d.; Lima, J.V.L.; Gomes, I.J.; Oliveira, P.H.d.A.; Silva, A.G.C.d.; Fernandes, B.C.C.; Rodrigues, A.P.; Silveira, L.M.d.; et al. Melatonin Improves Drought Tolerance in Zinnia elegans Through Osmotic Adjustment and Stomatal Regulation. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2571. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112571

Coêlho EdS, Ribeiro JEdS, Silva EFd, Lima JVL, Gomes IJ, Oliveira PHdA, Silva AGCd, Fernandes BCC, Rodrigues AP, Silveira LMd, et al. Melatonin Improves Drought Tolerance in Zinnia elegans Through Osmotic Adjustment and Stomatal Regulation. Agronomy. 2025; 15(11):2571. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112571

Chicago/Turabian StyleCoêlho, Ester dos Santos, João Everthon da Silva Ribeiro, Elania Freire da Silva, John Victor Lucas Lima, Ingrid Justino Gomes, Pablo Henrique de Almeida Oliveira, Antonio Gideilson Correia da Silva, Bruno Caio Chaves Fernandes, Ana Paula Rodrigues, Lindomar Maria da Silveira, and et al. 2025. "Melatonin Improves Drought Tolerance in Zinnia elegans Through Osmotic Adjustment and Stomatal Regulation" Agronomy 15, no. 11: 2571. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112571

APA StyleCoêlho, E. d. S., Ribeiro, J. E. d. S., Silva, E. F. d., Lima, J. V. L., Gomes, I. J., Oliveira, P. H. d. A., Silva, A. G. C. d., Fernandes, B. C. C., Rodrigues, A. P., Silveira, L. M. d., & Barros Júnior, A. P. (2025). Melatonin Improves Drought Tolerance in Zinnia elegans Through Osmotic Adjustment and Stomatal Regulation. Agronomy, 15(11), 2571. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112571