Microbial Inoculation Differentially Affected the Performance of Field-Grown Young Monastrell Grapevines Under Semiarid Conditions, Depending on the Rootstock

Abstract

1. Introduction

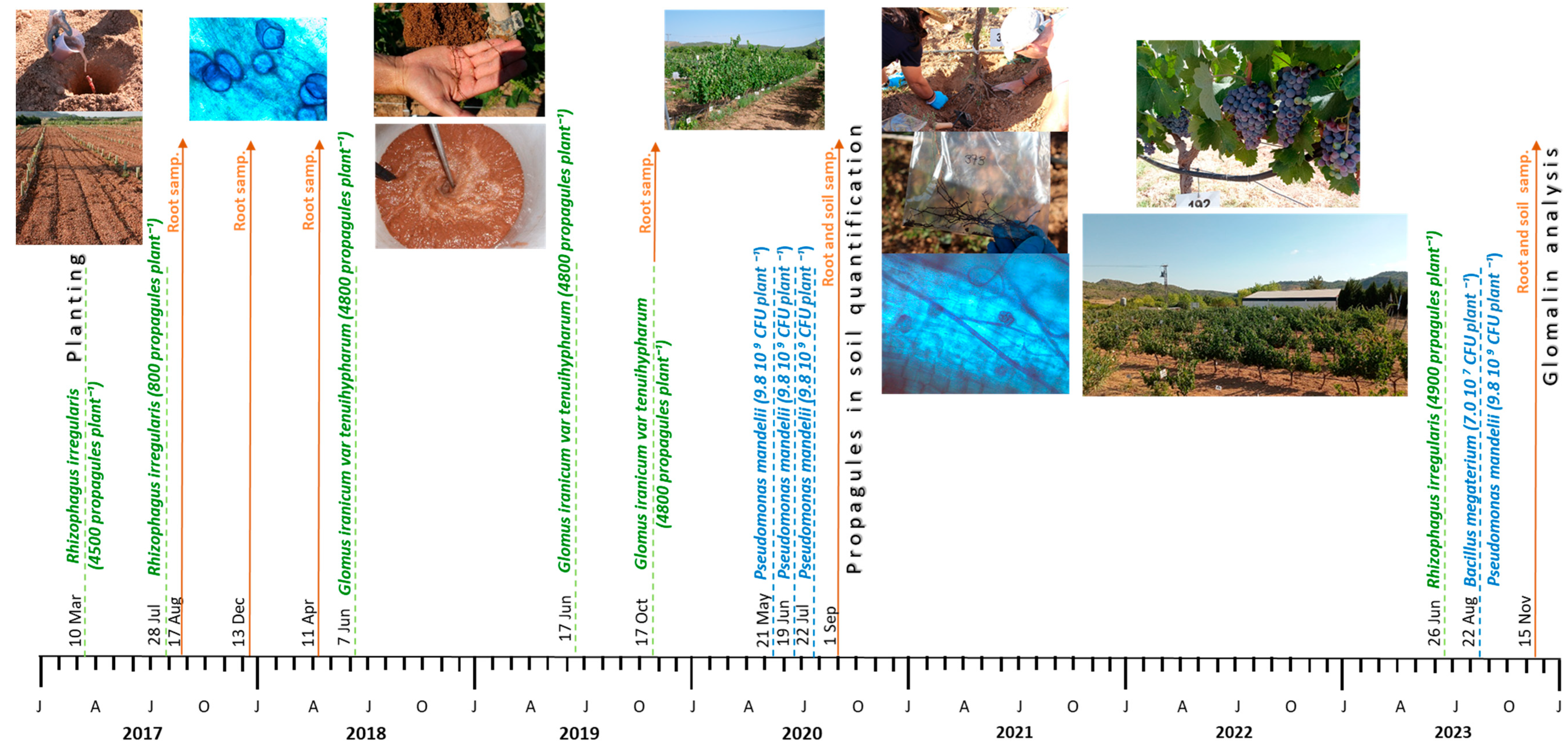

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Field Conditions, Plant Materials, Irrigation, and Soil Treatments

2.2. Experimental Design and Microbial Inoculation Treatments

2.3. Extraction and Quantification of Arbuscular Fungal Propagules in Soil

2.4. Glomalin Concentration in Soil

2.5. Organic Matter Decomposition

2.6. Soil Gas Exchange and Oxygen Diffusion Measurements

2.7. Vine Water Status and Leaf Gas Exchange

2.8. Leaf Mineral Analysis

2.9. Vegetative and Reproductive Development

2.10. Berry and Must Quality

2.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

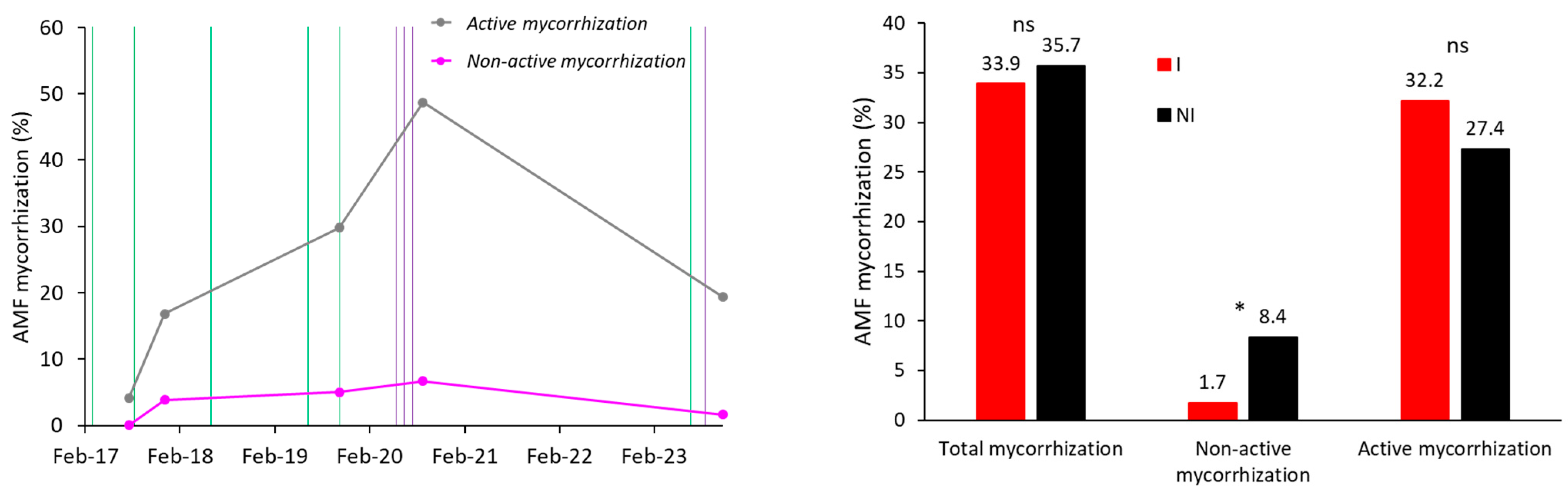

3.1. Effect of Microbial Inoculation on Mycorrhization

3.2. Effect of the Rootstock

3.2.1. Soil Respiration and Organic Matter Cycling

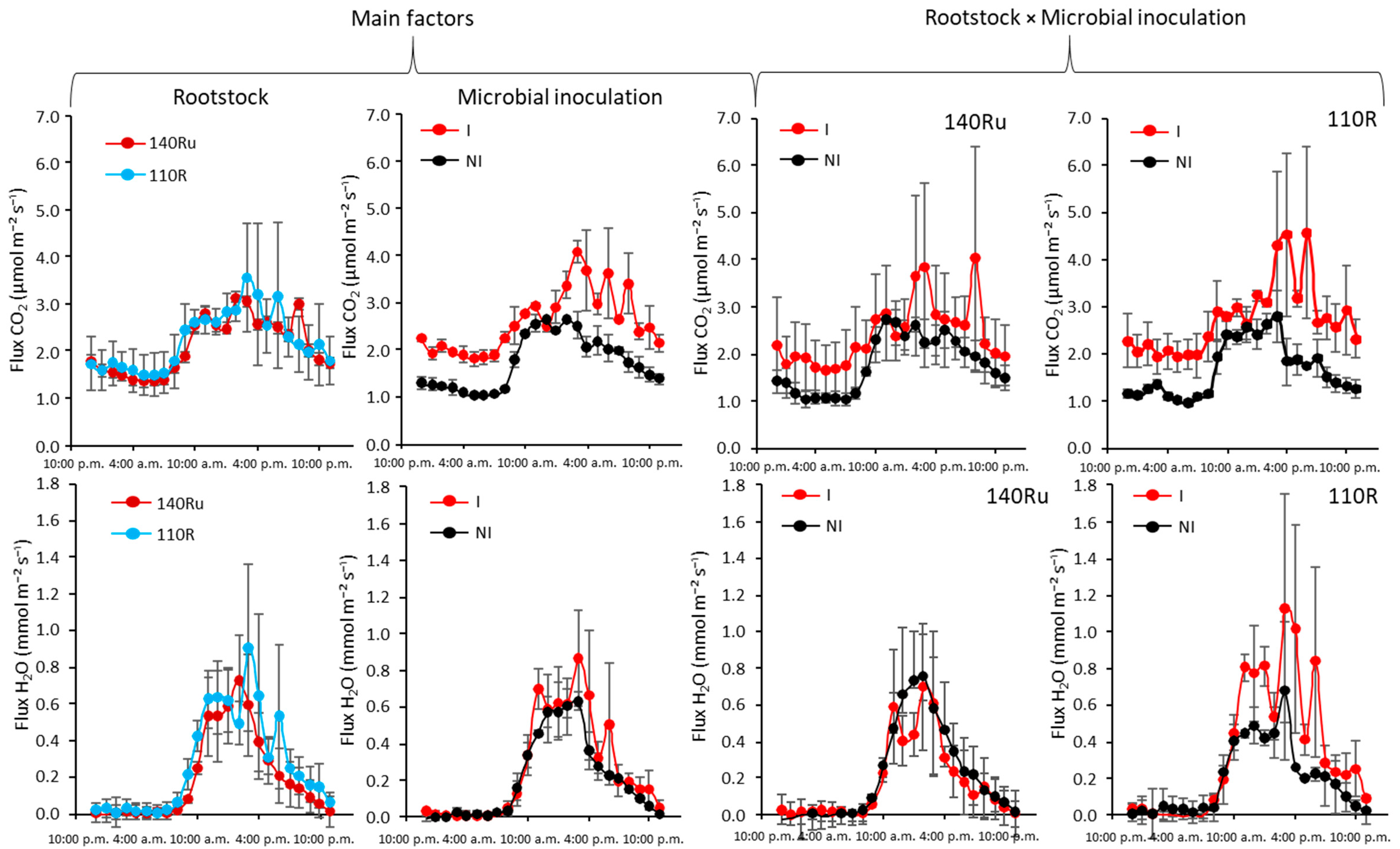

3.2.2. Soil-Plant Water Relations and Leaf Gas Exchange

3.2.3. Leaf Mineral Nutrition

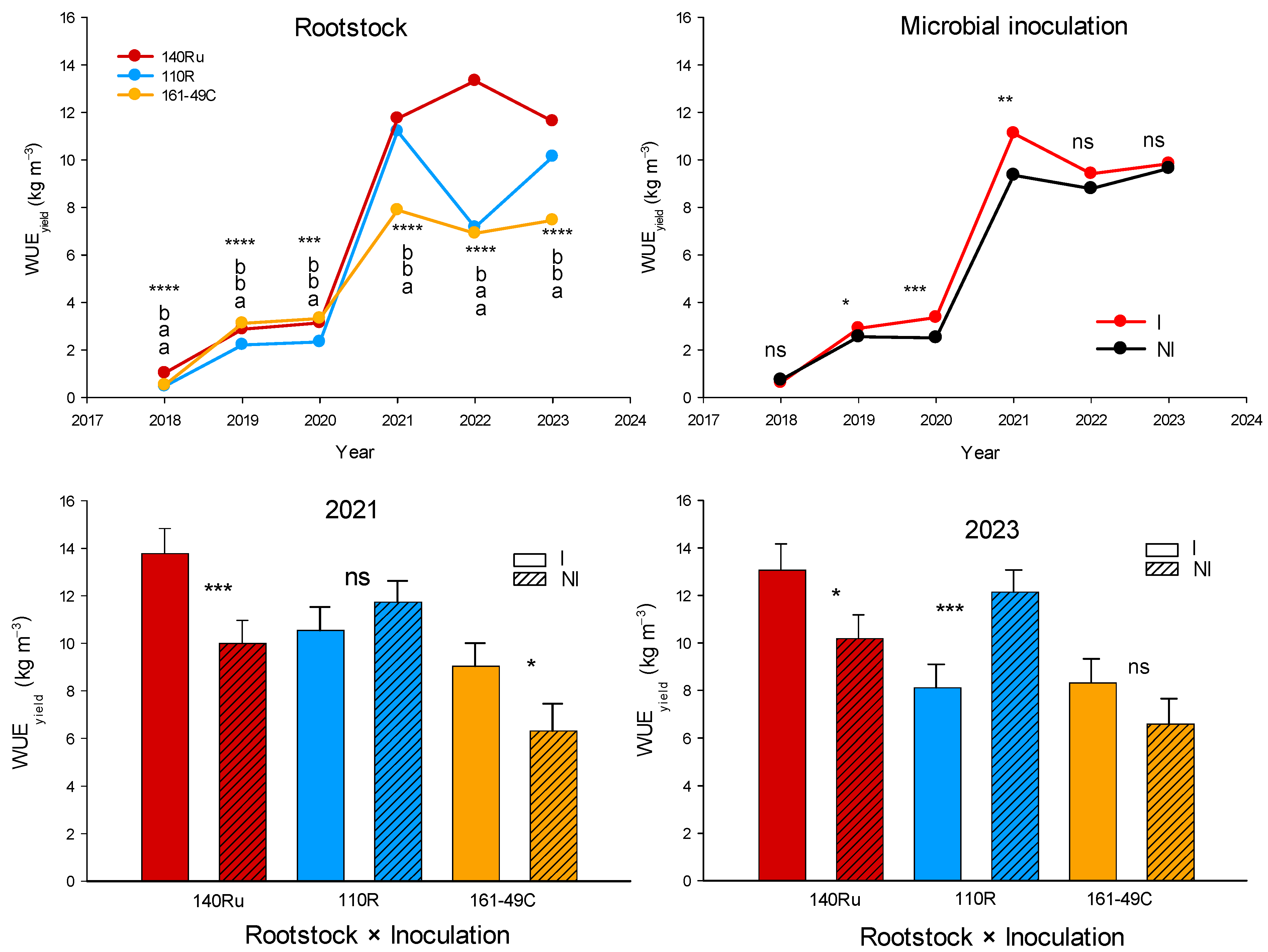

3.2.4. Vegetative and Reproductive Development

3.2.5. Berry Quality Response

3.3. Effect of Microbial Inoculation and Its Interaction with the Rootstock

3.3.1. Soil Respiration and Organic Matter Cycling

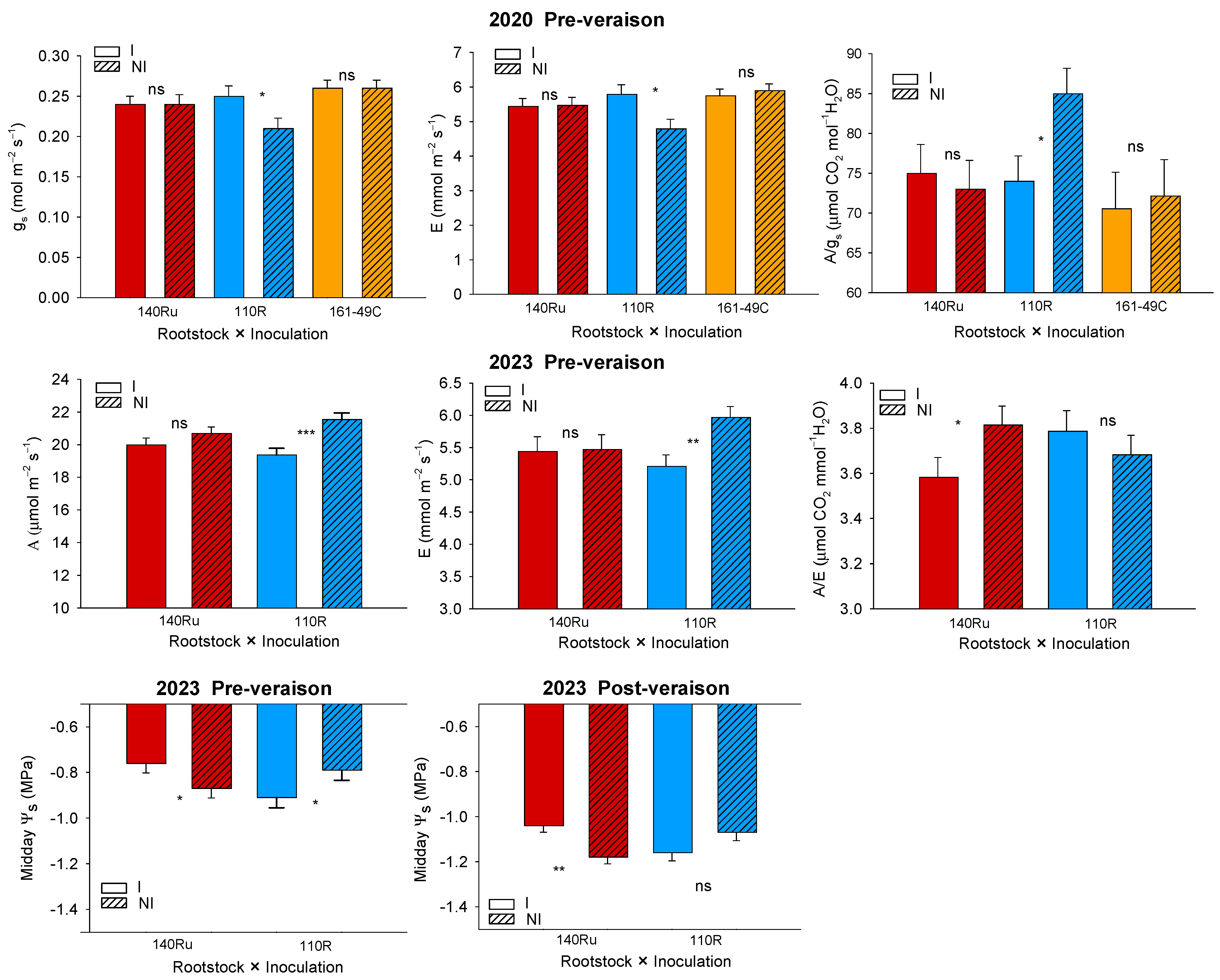

3.3.2. Soil-Plant Water Relations and Leaf Gas Exchange

3.3.3. Leaf Mineral Nutrition

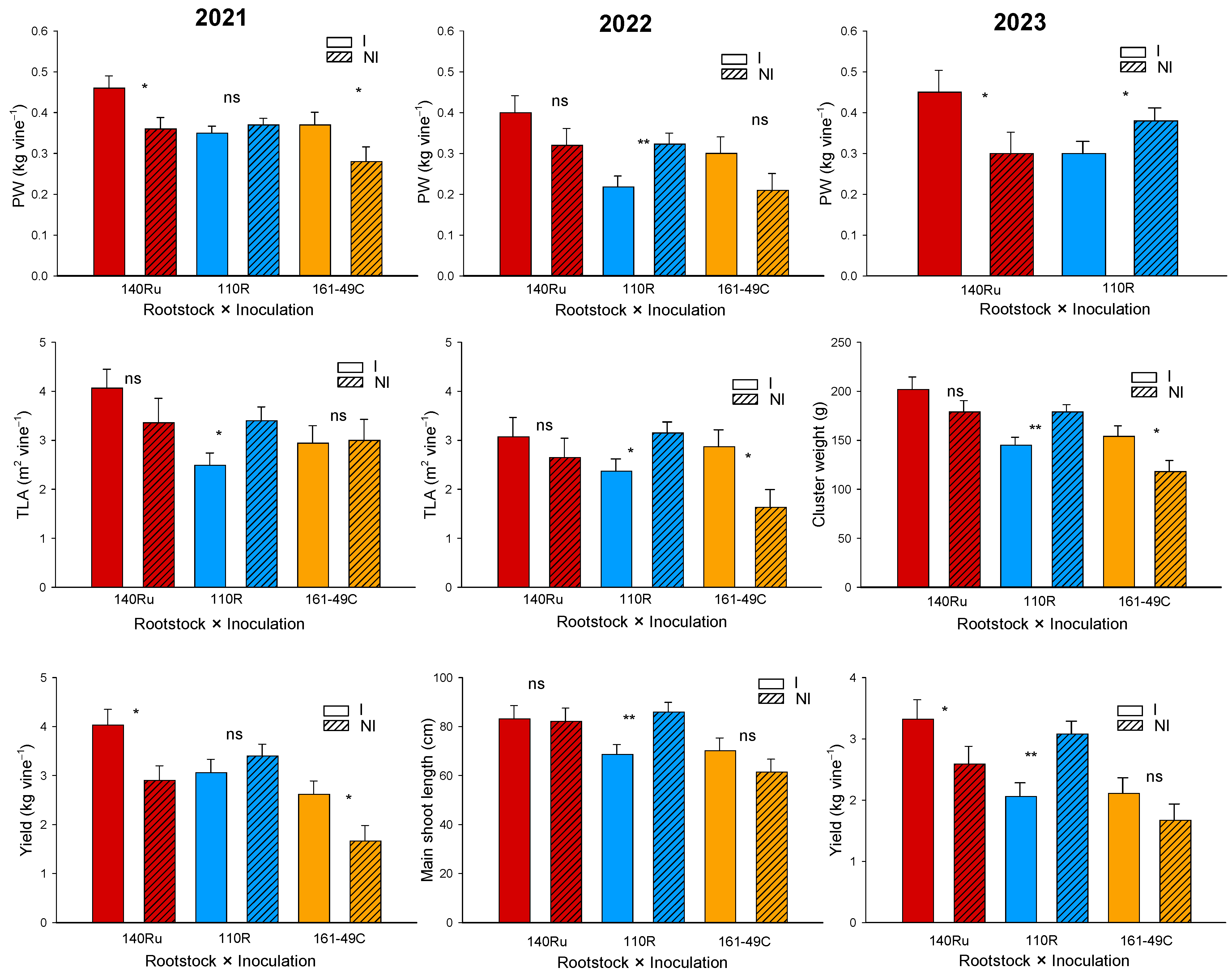

3.3.4. Vegetative and Reproductive Development

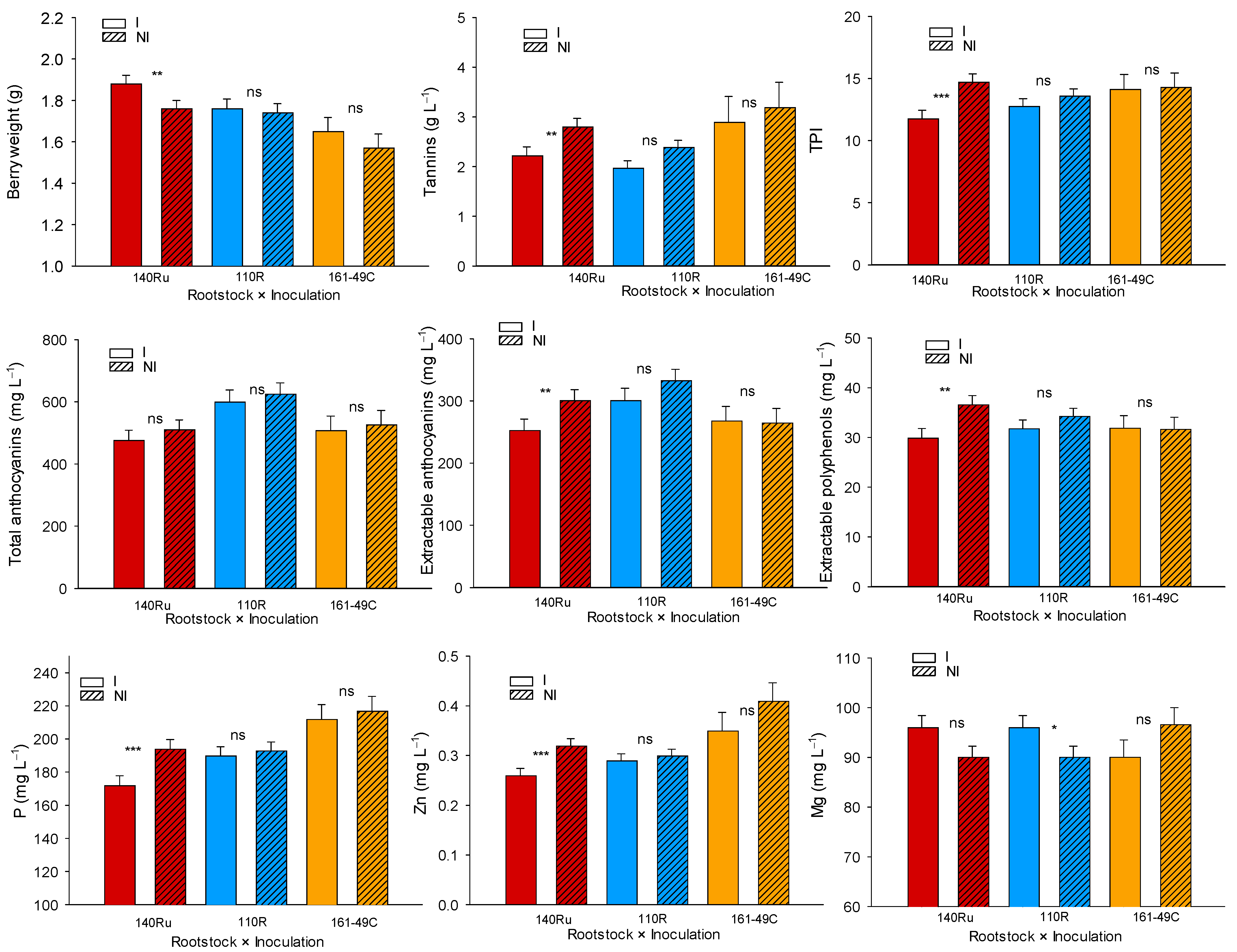

3.3.5. Berry Quality Response

4. Discussion

4.1. Effect of the Rootstock on the Performance of a Young Vineyard

4.2. Effect of Microbial Inoculation and Its Interaction with the Rootstock in the Soil Environment

4.3. Effect of the Microbial Inoculation and Its Interaction with the Rootstock on Young Vine Performance

5. Conclusions and Future Remarks

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| I | inoculated |

| NI | non-inoculated |

| AMF | arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi |

| MHB | mycorrhizal helper bacteria |

| PGPR | plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria |

| PGPB | plant growth-promoting bacteria |

| DI | deficit irrigation |

| ODR | oxygen diffusion rate |

| TBI | Tea Bag Index |

| S | stabilization factor |

| k | decomposition rate constant |

| TG | total glomalin |

| Ψs | midday stem water potential |

| A | net photosynthesis rate |

| gs | stomatal conductance rate |

| E | transpiration rate |

| A/gs | intrinsic leaf water use efficiency |

| A/E | instantaneous leaf water use efficiency |

| WUEyield | productive water use efficiency |

| VPD | vapor pressure deficit |

| TLA | total leaf area |

| PW | winter pruning weight |

| SL | shoot length |

| PW | pruning weight |

| MI | maturity index |

| TA | titratable acidity |

| A520 | absorbance at 520 nm |

| CI | color index |

| SMI | seed maturity index |

| AEI | anthocyanin extractability index |

| TSS | total soluble solid |

| TPI | total polyphenol index |

References

- De Souza, R.; Ambrosini, A.; Passaglia, L.M.P. Plant growth-promoting bacteria as inoculants in agricultural soils. Genet. Mol. Bio. 2015, 38, 401–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balestrini, R.; Sillo, F.; Boussageon, R.; Wipf, D.; Courty, P.E. The hidden side of interaction: Microbes and roots get together to improve plant resilience. J. Plant Interact. 2024, 19, 2323991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trouvelot, S.; Bonneau, L.; Redecker, D.; van Tuinen, D.; Adrian, M.; Wipf, D. Arbuscular mycorrhiza symbiosis in viticulture: A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 35, 1449–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, N.; Goicoechea, N.; Morales, F.; Antolín, M.C. Berry quality and antioxidant properties in Vitis vinifera cv. Tempranillo as affected by clonal variability, mycorrhizal inoculation and temperature. Crop Pasture Sci. 2016, 67, 961–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, N.; Antolín, M.C.; Goicoechea, N. Arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis as a promising resource for improving berry quality in grapevines under changing environments. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velaz, M.; Santesteban, L.G.; Torres, N. Mycorrhizae and grapevines: The known unknowns of their interaction for wine growers’ challenges. J. Exp. Bot. 2025, 76, 3001–3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nerva, L.; Balestrini, R.; Chitarra, W. From plant nursery to field: Persistence of mycorrhizal symbiosis balancing effects on growth-defence tradeoffs mediated by rootstock. Agronomy 2023, 13, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Corato, U. Soil microbiota manipulation and its role in suppressing soil-borne plant pathogens in organic farming systems under the light of microbiome-assisted strategies. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2020, 7, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nerva, L.; Giudice, G.; Quiroga, G.; Belfiore, N.; Lovat, L.; Perria, R.; Volpe, M.G.; Moffa, L.; Sandrini, M.; Gaiotti, F.; et al. Mycorrhizal symbiosis balances rootstock-mediated growth-defence tradeoffs. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2021, 58, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fall, A.F.; Nakabonge, G.; Ssekandi, J.; Founoune-Mboup, H.; Apori, S.O.; Ndiaye, A.; Badji, A.; Ngom, K. Roles of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on soil fertility: Contribution in the improvement of physical, chemical, and biological properties of the soil. Front. Fungal Biol. 2022, 3, 723892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozikova, D.; Pascual, I.; Goicoechea, N. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi improve the performance of Tempranillo and Cabernet Sauvignon facing water deficit under current and future climatic conditions. Plants 2024, 13, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarnizo, A.L.; Navarro-Ródenas, A.; Calvo-Polanco, M.; Marqués-Gálvez, J.E.; Morte, A. A mycorrhizal helper bacterium alleviates drought stress in mycorrhizal Helianthemum almeriense plants by regulating water relations and plant hormones. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2023, 207, 105228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolli, E.; Marasco, R.; Saderi, S.; Corretto, E.; Mapelli, F.; Cherif, A.; Borin, S.; Valenti, L.; Sorlini, C.; Daffonchio, D. Root-associated bacteria promote grapevine growth: From the laboratory to the field. Plant Soil 2017, 410, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khabbaz, S.E.; Ladhalakshmi, D.; Babu, M.; Kandan, A.; Ramamoorthy, V.; Saravanakumar, D.; Al-Mughrabi, T.; Kandasamy, S. Plant growth promoting bacteria (PGPB)—A versatile tool for plant health management. Can. J. Pestic. Pest Manag. 2019, 1, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangwan, S.; Prasanna, R. Mycorrhizae helper bacteria: Unlocking their potential as bioenhancers of plant-arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal associations. Microb. Ecol. 2022, 84, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camprubí, A.; Estaún, V.; Nogales, A.; García-Figueres, F.; Pitet, M.; Calvet, C. Response of the grapevine rootstock Richter 110 to inoculation with native and selected arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and growth performance in a replant vineyard. Mycorrhiza 2008, 18, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolli, E.; Marasco, R.; Vigani, G.; Ettoumi, B.; Mapelli, F.; Deangelis, M.L.; Gandolfi, C.; Casati, E.; Previtali, F.; Gerbino, R.; et al. Improved plant resistance to drought is promoted by the root-associated microbiome as a water stress-dependent trait. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 17, 316–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Shen, Y.; Li, Q.; Xiao, W.; Song, X. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal colonization and soil pH induced by nitrogen and phosphorus additions affects leaf C:N:P stoichiometry in Chinese fir (Cunninghamia lanceolata) forests. Plant Soil 2021, 461, 421–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahab, A.; Muhammad, M.; Munir, A.; Abdi, G.; Zaman, W.; Ayaz, A.; Khizar, C.; Reddy, S.P.P. Role of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in regulating growth, enhancing productivity, and potentially influencing ecosystems under abiotic and biotic stresses. Plants 2023, 12, 3102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiner, R.P.; Moyer, M.M.; East, K.E.; Zasada, I.A. Managing arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in arid Columbia Basin vineyards of the Pacific Northwest United States. Am. J. Enol. Viticult. 2023, 74, 0740020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, T.C.; Bowen, P.; Bogdanoff, C.; Hart, M.M. How distinct are arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal communities associating with grapevines? Biol. Fertil. Soils 2014, 50, 667–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, N.; Yu, R.; Kurtural, S.K. Arbuscular mycrorrhizal fungi inoculation and applied water amounts modulate the response of young grapevines to mild water stress in a hyper-arid season. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 11, 622209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovannini, L.; Pagliarani, C.; Moine, A.; Giannetti, G.; Carra, A.; Nerva, L.; Chitarra, W.; Gambino, G.; Sbrana, C.; Balestrini, R. The impact of the symbiont genotype on the effect of arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis on grapevine growth and physiology. Plant Biosyst. 2025, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darriaut, R.; Antonielli, L.; Martins, G.; Ballestra, P.; Vivin, P.; Marguerit, E.; Mitter, B.; Masneuf-Pomarède, I.; Compant, S.; Ollat, N.; et al. Soil composition and rootstock genotype drive the root associated microbial communities in young grapevines. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1031064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niem, J.M.; Billones-Baaijens, R.; Stodart, B.; Savocchia, S. Diversity profiling of grapevine microbial endosphere and antag-onistic potential of endophytic pseudomonas against grapevine trunk diseases. Front Microbiol. 2020, 11, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit, E.; Gubler, W.D. Influence of Glomus intraradices on Black foot disease caused by Cylindrocarpon macrodidymum on Vitis rupestris under controlled conditions. Plant Dis. 2006, 90, 1481–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.Y.; Yang, G.D.; Shu, H.R.; Yang, Y.T.; Ye, B.X.; Nishida, I.; Zheng, C.C. Colonization by the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus Glomus versiforme induces a defense response against the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita in the grapevine (Vitis amurensis Rupr.), which includes transcriptional activation of the class III chitinase gene VCH3. Plant Cell Physiol. 2006, 47, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lailheugue, V.; Darriaut, R.; Tran, J.; Morel, M.; Marguerit, E.; Lauvergeat, V. Both the scion and rootstock of grafted grapevines influence the rhizosphere and root endophyte microbiomes, but rootstocks have a greater impact. Environ. Microbiome. 2024, 19, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandian, K.; Samiyappan, K.; Rangasamy, A.; Raju, I.; Chitraputhirapillai, S.; Bose, J. Bacillus megaterium-embedded organo biochar phosphorous fertilizer improves soil microbiome and nutrient availability to enhance black gram (Vigna mungo L.) growth and yield. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2024, 24, 2048–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, M.; Yang, W.; Di, H.J.; Ma, L.; Liu, W.; Li, B. Effects of microbial inoculants on phosphorus and potassium availability, bacterial community composition, and chili pepper growth in a calcareous soil: A greenhouse study. J. Soils Sediments 2019, 19, 3597–3607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Ródenas, A.; Berná, L.M.; Lozano-Carrillo, C.; Andrino, A.; Morte, A. Beneficial native bacteria improve survival and mycorrhization of desert truffle mycorrhizal plants in nursery conditions. Mycorrhiza 2016, 26, 769–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, J.M.; Hayman, D.S. Improved procedures for clearing roots and staining parasitic and vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi for rapid assessment of infection. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 1970, 55, 158–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGonigle, T.P.; Miller, M.H.; Evans, D.G.; Fairchild, G.L.; Swan, J.A. A new method which gives an objective measure of colonization of roots by vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. New Phytol. 1990, 115, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Xu, C.; Wang, Y.; Huang, D.; Fan, Q.; Xin, G.; Müller, C. Dynamics of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in relation to root colonization, spore density, and soil properties among different spreading stages of the exotic plant three flower beggarweed (Desmodium triflorum) in a Zoysia tenuifolia lawn. Weed Sci. 2019, 67, 730–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.; Singh, M.; Srivastava, D.K.; Singh, P.K. Exploring the diversity, root colonization, and morphology of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in Lamiaceae. J. Basic Microbiol. 2025, 65, e2400379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerdemann, J.W.; Nicolson, T.H. Spores of mycorrhizal Endogone species extracted from soil by wet sieving and decanting. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 1963, 46, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, S.F.; Upadhayaya, A. A survey of soils for aggregate stability and glomalin, a glycoprotein produced by hyphae of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Plant Soil. 1998, 198, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keuskamp, J.A.; Dingemans, B.J.J.; Lehtinen, T.; Sameel, J.M.; Hefting, M.M. Tea Bag Index: A novel approach to collect uniform decomposition data across ecosystems. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2013, 4, 1070–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, P.; Botía, P.; Navarro, J.M. Selecting rootstocks to improve vine performance and vineyard sustainability in deficit irrigated Monastrell grapevines under semiarid conditions. Agric. Water Manag. 2018, 209, 73–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, P.; Gil-Muñoz, R.; del Amor, F.; Valdés, E.; Fernández-Fernández, J.I.; Martínez-Cutillas, A. Regulated deficit irrigation based upon optimum water status improves phenolic composition in Monastrell grapes and wines. Agric. Water Manag. 2013, 121, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saint-Cricq, N.; Vivas, N.; Glories, Y. Maturité phénolique: Définition et contrôle. Rev. Fr. d’Oenolog. 1998, 173, 22–25. [Google Scholar]

- Ribéreau-Gayon, P.; Glories, Y.; Maujean, A.; Dubourdied, D. Handbook of Enology Volume 2: The Chemistry of Wine and Stabilization and Treatments, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2006; p. 456. [Google Scholar]

- Wooldridge, J.; Louw, P.J.E.; Conradie, W.J. Effects of rootstock on grapevine performance, petiole and must composition, and overall wine score of Vitis vinifera cv. Chardonnay and Pinot noir. S. Afr. J. Enol. Vitic. 2010, 31, 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santesteban, L.G.; Rekarte, I.; Torres, N.; Galar, M.; Villa-Llop, A.; Visconti, F.; Intrigliolo, D.S.; Escalona, J.M.; Herralde, F.; Miranda, C. The role of rootstocks for grape growing adaptation to climate change. Meta-analysis of the research conducted in Spanish viticulture. OENO One 2023, 57, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, P.; Botía, P.; Morote, E.; Navarro, J.M. Optimizing deficit irrigation in Monastrell vines grafted on rootstocks of different vigour under semiarid conditions. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 292, 108669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovisolo, C.; Lavoie-Lamoureux, A.; Tramontini, S.; Ferrandino, A. Grapevine adaptations to water stress: New perspectives about soil/plant interactions. Theor. Exp. Plant Physiol. 2016, 28, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tramontini, S.; van Leeuwen, C.; Domec, J.C.; Destrac-irvine, A.; Basteau, C.; Vitali, M.; Mosbach-Schulz, O.; Lovisolo, C. Impact of soil texture and water availability on the hydraulic control of plant and grape-berry development. Plant Soil 2013, 368, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pou, A.; Rivacoba, L.; Portu, J.; Mairata, A.; Labarga, D.; García-Escudero, E.; Martín, I. How rootstocks impact the scion vigour and vine performance of Vitis vinifera L. cv. Tempranillo. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2022, 2022, 9871347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, J.M.; Botía, P.; Romero, P. Changes in berry tissues in Monastrell grapevines grafted on different rootstocks and their relationship with berry and wine phenolic content. Plants 2021, 10, 2585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spilmont, A.S.; Sereno, C.; El khoti, N.; Torregrosa, L. The decline of the young vines grafted onto 161-49C. Acta Hortic. 2016, 1136, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdeja, M.P.; Reynolds, N.K.; Pawlowska, T.; Vanden Heuvel, J.E. Commercial bioinoculants improve colonization but do not alter the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal community of greenhouse-grown grapevine roots. Environ. Microbiome 2025, 20, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Mallik, A.; Zhang, J.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, L. Effects of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on inoculated seedling growth and rhizosphere soil aggregates. Soil Tillage Res. 2019, 194, 104340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolás, E.; Maestre-Valero, J.F.; Alarcón, J.J.; Pedrero, F.; Vicente-Sánchez, J.; Bernabé, A.; Gómez-Montiel, J.A.; Hernández, J.A.; Fernández, F. Effectiveness and persistence of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on the physiology, nutrient uptake and yield of Crimson seedless grapevine. J. Agric. Sci. 2015, 153, 1084–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.-Y.; Liu, C.-Y.; Hao, Y. Differential effects of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on rooting and physiology of ‘Summer Black’ grape cuttings. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rillig, M.C.; Mummey, D.L. Mycorrhizas and soil structure. New Phytol. 2006, 171, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leifheit, E.F.; Veresoglou, S.D.; Lehmann, A.; Morris, E.K.; Rillig, M.C. Multiple factors influence the role of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in soil aggregation—A meta-analysis. Plant Soil 2014, 374, 523–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitterlich, M.; Sandmann, M.; Graefe, J. Arbuscular mycorrhiza improves substrate hydraulic conductivity in tomato by altering pore connectivity. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.; Cui, B.; Liu, B.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, C. Effects of biochar and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on winter wheat growth and soil N2O emissions in different phosphorus environments. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1069627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganugi, P.; Soverini, M.; Di Lorenzo, M.; Fiorini, A.; Tittarelli, A. A 3-year application of different mycorrhiza-based plant biostimulants distinctively modulates photosynthetic performance, leaf metabolism, and fruit quality in grapes (Vitis vinifera L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1236199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, P.; Barra, P.J.; Pollak, B.; Varela, S. Application of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in vineyards: Water and biotic stress under a climate change scenario. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 826571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacDonald, E.; Martin, E.; Brummell, M.E.; Bieniada, A.; Elliott, J.; Engering, A.; Tasha-Leigh, G.; Saraswati, S.; Touchette, S.; Turmel-Courchesne, L.; et al. Using the Tea Bag Index to characterize decomposition rates in restored peatlands. Boreal Environ. Res. 2018, 23, 221–235. [Google Scholar]

- Moukarzel, R.; Ridgway, H.J.; Waller, L.; Guerin-Laguette, A.; Cripps-Guazzone, N.; Jones, E.E. Soil arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal communities differentially affect growth and nutrient uptake by grapevine rootstocks. Microb. Ecol. 2023, 86, 1035–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antolín, M.C.; Izurdiaga, D.; Urmeneta, L.; Pascual, I.; Irigoyen, J.J.; Goicoechea, N. Dissimilar responses of ancient grapevines recovered in Navarra (Spain) to arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis in terms of berry quality. Agronomy 2020, 10, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdeja, M.P.; Ye, Q.; Bauerle, T.L.; Vanden Heuvel, J.E. Commercial bioinoculants increase root length colonization and improve petiole nutrient concentration of field-grown grapevines. HortTechnology 2023, 33, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogales, A.; Santos, E.S.; Abreu, M.M.; Arán, D.; Victorino, G.; Pereira, H.S.; Lopez, C.M.; Viegas, W. Mycorrhizal inoculation differentially affects grapevine’s performance in copper contaminated and non-contaminated soils. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 9, 1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balestrini, R.; Salvioli, A.; Dal Molin, A.; Novero, M.; Gabelli, G.; Paparelli, E.; Marroni, F.; Bonfante, P. Impact of an arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus versus a mixed microbial inoculum on the transcriptome reprogramming of grapevine roots. Mycorrhiza 2017, 27, 417–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruisson, S.; Maillot, P.; Schellenbaum, P.; Walter, B.; Gindro, K.; DeglèneBenbrahim, L. Arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis stimulates key genes of the phenylpropanoid biosynthesis and stilbenoid production in grapevine leaves in response to downy mildew and grey mould infection. Phytochemistry 2016, 131, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moukarzel, R.; Ridgway, H.J.; Gurein-Laguette, A.; Jones, E.E. Grapevine rootstocks drive the community structure of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in New Zealand vineyards. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2021, 131, 2941–2956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marastoni, L.; Lucini, L.; Miras-Moreno, B.; Marco Trevisan, M.; Sega, D.; Zamboni, A.; Varanini, Z. Changes in physiological activities and root exudation profile of two grapevine rootstocks reveal common and specific strategies for Fe acquisition. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 18839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, P.; Acosta, J.M.N.; Pérez-Pérez, J.G.; Dodd, I.C.; Antolinos, V.; Marín, J.L.; del Amor Saavedra, F.; Molina, E.M.; Ordaz, P.B. The rootstock imparts different drought tolerance strategies in long-term field-grown deficit irrigated grapevines. Sci. Hortic. 2025, 346, 114167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Irrigation (mm Year−1) | ETo (mm Year−1) | VPD (kPa) | Rainfall (mm Year−1) | Tmax (°C) | Tmean (°C) | Tmin (°C) | RHmean (%) | Solar Rad. (W m−2) | Daily Sunshine (h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High irrigation conditions | ||||||||||

| 2018 | 274.4 | 1162 | 0.92 | 392 | 22.46 | 14.98 | 7.59 | 61.79 | 200.07 | 9.43 |

| 2019 | 283.1 | 1173 | 0.98 | 427 | 23.03 | 15.08 | 6.99 | 60.24 | 206.30 | 9.49 |

| 2020 | 304.0 | 1106 | 0.97 | 393 | 23.34 | 15.28 | 8.07 | 63.26 | 202.14 | 9.42 |

| Deficit irrigation conditions | ||||||||||

| 2021 | 103.5 | 1100 | 0.93 | 321 | 23.10 | 15.36 | 7.57 | 63.66 | 197.32 | 9.32 |

| 2022 | 89.4 | 1200 | 1.09 | 300 | 25.03 | 16.13 | 7.33 | 61.80 | 191.80 | 9.45 |

| 2023 | 90.6 | 1105 | 1.09 | 162 | 24.55 | 15.81 | 7.04 | 57.25 | 203.98 | 9.43 |

| Rootstock (R) | TG (μg g−1 Soil DW) | ODR (μg m−2 s−1) | k | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 140Ru | 2267 | 48.5 | 0.019 | |

| 110R | 2194 | 44.5 | 0.019 | |

| 161-49C | - | 44.7 | - | |

| Microbial inoculation (MI) | ||||

| I | 2378 | 46.9 | 0.023 | |

| NI | 2083 | 45.0 | 0.016 | |

| R × MI | ||||

| 140Ru | I | 2580 b | 49.6 b | 0.024 |

| NI | 1953 a | 47.5 ab | 0.015 | |

| 110R | I | 2176 ab | 41.6 ab | 0.021 |

| NI | 2212 ab | 47.5 ab | 0.017 | |

| 161-49C | I | - | 49.6 b | - |

| NI | - | 39.9 a | - | |

| ANOVA | ||||

| R | ns | ns | ns | |

| MI | ns | ns | *** | |

| R × MI | * | * | ns | |

| Pre-Veraison | Post-Veraison | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | gs | E | A/gs | A/E | Ψs | A | gs | E | A/gs | A/E | Ψs | |

| Rootstock (R) | 2018 | |||||||||||

| 140Ru | 18.8 | 0.160 | 4.6 | 140 | 4.7 | −0.69 | 17.0 a | 0.239 a | 5.8 | 78 | 3.0 | −0.75 |

| 110R | 18.4 | 0.156 | 4.6 | 136 | 4.5 | −0.68 | 18.3 b | 0.279 b | 6.3 | 70 | 3.0 | −0.75 |

| 161-49C | 17.9 | 0.137 | 4.1 | 152 | 4.9 | −0.68 | 17.7 ab | 0.268 ab | 6.3 | 70 | 2.9 | −0.75 |

| Microbial inoculation(MI) | ||||||||||||

| I | 18.7 | 0.158 | 4.6 | 139 | 4.6 | −0.69 | 18.1 | 0.270 | 6.4 | 72 | 2.9 | −0.76 |

| NI | 18.0 | 0.144 | 4.2 | 146 | 4.9 | −0.67 | 17.2 | 0.254 | 5.8 | 73 | 3.1 | −0.74 |

| ANOVA | ||||||||||||

| R | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | * | * | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| MI | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | * | ns | * | ns | ** | ns |

| R × MI | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Rootstock (R) | 2020 | |||||||||||

| 140Ru | 17.2 | 0.241 | 5.5 ab | 74.2 | 3.2 a | - | 14.4 | 0.168 ab | 4.5 a | 91.9 ab | 3.4 | - |

| 110R | 18.0 | 0.231 | 5.3 a | 79.4 | 3.5 b | - | 13.7 | 0.156 a | 4.3 a | 94.6 b | 3.4 | - |

| 161-49C | 17.8 | 0.256 | 5.8 b | 71.4 | 3.1 a | - | 15.3 | 0.210 b | 5.3 b | 78.5 a | 3.0 | - |

| Microbial inoculation (MI) | ||||||||||||

| I | 17.8 | 0.250 | 5.7 | 73.1 | 3.2 | - | 14.7 | 0.181 | 4.8 | 85.9 | 3.2 | - |

| NI | 17.5 | 0.235 | 5.4 | 76.8 | 3.4 | - | 14.3 | 0.175 | 4.6 | 90.8 | 3.3 | - |

| ANOVA | ||||||||||||

| R | ns | ns | * | ns | *** | - | ns | ** | ** | * | ns | - |

| MI | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | - | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | - |

| R × MI | ns | ns | ** | ns | ** | - | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | - |

| Rootstock (R) | 2021 | |||||||||||

| 140Ru | 15.0 | 0.164 | 4.0 | 95.4 | 3.8 | −0.97 | 12.5 | 0.117 | 2.9 | 117.7 | 4.6 | −1.28 b |

| 110R | 14.8 | 0.168 | 4.0 | 93.2 | 3.7 | −1.02 | 12.6 | 0.119 | 2.9 | 115.2 | 4.5 | −1.24 b |

| 161-49C | 15.0 | 0.156 | 3.9 | 97.1 | 3.9 | −1.07 | 11.4 | 0.115 | 2.8 | 113.3 | 4.3 | −1.39 a |

| Microbial inoculation (MI) | ||||||||||||

| I | 14.8 | 0.159 | 3.9 | 97.3 | 3.8 | −1.04 | 11.7 | 0.114 | 2.8 | 113.5 | 4.3 | −1.30 |

| NI | 14.9 | 0.166 | 4.0 | 93.1 | 3.8 | −1.00 | 12.7 | 0.120 | 2.9 | 117.4 | 4.6 | −1.30 |

| ANOVA | ||||||||||||

| R | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | * |

| MI | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ** | ns |

| R × MI | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Rootstock (R) | 2023 | |||||||||||

| 140Ru | 20.3 | - | 5.6 | - | 3.7 | −0.81 | 14.0 | 0.148 | 3.9 | 103.0 | 3.8 | −1.11 |

| 110R | 20.5 | - | 5.6 | - | 3.7 | −0.85 | 13.9 | 0.138 | 4.0 | 105.3 | 3.7 | −1.12 |

| 161-49C | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Microbial inoculation (MI) | ||||||||||||

| I | 19.7 | - | 5.4 | - | 3.7 | −0.83 | 13.5 | 0.129 | 3.6 | 107.7 | 3.9 | −1.10 |

| NI | 21.1 | - | 5.8 | - | 3.8 | −0.83 | 14.5 | 0.157 | 4.3 | 100.5 | 3.6 | −1.12 |

| ANOVA | ||||||||||||

| R | ns | - | ns | - | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| MI | *** | - | ** | - | ns | ns | * | ** | ** | * | ns | ns |

| R × MI | * | - | ** | - | * | ** | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ** |

| N | P | K | Ca | Mg | Na | Fe | Zn | Mn | Cu | B | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rootstock (R) | 2018 | |||||||||||

| 140Ru | 3.0 a | 0.158 a | 0.62 a | 2.15 | 0.45 b | 0.044 a | 75.6 | 19.1 | 147 | 11.1 | 38.3 | |

| 110R | 3.2 b | 0.179 b | 0.73 b | 1.94 | 0.36 a | 0.047 a | 76.5 | 18.3 | 133 | 11.5 | 49.1 | |

| 161-49C | 3.2 b | 0.178 b | 0.75 b | 2.08 | 0.35 a | 0.059 b | 68.1 | 19.2 | 153 | 12.3 | 43.3 | |

| Microbial inoculation (MI) | ||||||||||||

| I | 3.2 | 0.175 | 0.72 | 2.03 | 0.39 | 0.047 | 70.5 | 18.7 | 146 | 11.6 | 42.8 | |

| NI | 3.1 | 0.169 | 0.67 | 2.08 | 0.38 | 0.053 | 76.4 | 19.1 | 143 | 11.6 | 44.3 | |

| ANOVA | ||||||||||||

| R | ** | ** | ** | ns | **** | ** | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | |

| MI | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | |

| R × MI | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ** | ns | ns | ns | |

| Rootstock (R) | 2021 | |||||||||||

| 140Ru | 2.52 | 0.142 | 0.65 | 1.64 | 0.33 b | 0.053 b | 84.7 | 33.8 | 133 ab | 14.4 | 27.7 a | |

| 110R | 2.47 | 0.139 | 0.65 | 1.62 | 0.28 a | 0.040 a | 83.7 | 32.9 | 125 a | 13.1 | 31.5 b | |

| 161-49C | 2.43 | 0.138 | 0.69 | 1.67 | 0.26 a | 0.037 a | 82.5 | 35.3 | 145 b | 13.9 | 25.6 a | |

| Microbial inoculation (MI) | ||||||||||||

| I | 2.48 | 0.140 | 0.68 | 1.67 | 0.30 | 0.033 | 80.6 | 36.6 | 136 | 13.7 | 27.8 | |

| NI | 2.47 | 0.139 | 0.65 | 1.62 | 0.29 | 0.054 | 86.7 | 31.4 | 132 | 13.9 | 28.7 | |

| R × MI | ||||||||||||

| 140Ru | I | 2.51 | 0.144 | 0.69 | 1.74 bc | 0.34 d | 0.032 a | 80.7 | 35.7 | 135 bc | 14.5 bc | 27.9 |

| NI | 2.53 | 0.139 | 0.62 | 1.54 a | 0.32 cd | 0.075 c | 88.6 | 31.9 | 131 ab | 14.4 bc | 27.4 | |

| 110R | I | 2.41 | 0.139 | 0.64 | 1.68 abc | 0.31 cd | 0.033 a | 79.3 | 36.0 | 135 bc | 13.9 abc | 31.6 |

| NI | 2.53 | 0.139 | 0.65 | 1.57 a | 0.26 ab | 0.047 b | 88.2 | 29.8 | 115 a | 12.2 a | 31.3 | |

| 161-49C | I | 2.52 | 0.137 | 0.70 | 1.59 ab | 0.24 a | 0.033 a | 81.8 | 38.0 | 139 bc | 12.6 ab | 23.9 |

| NI | 2.35 | 0.139 | 0.67 | 1.76 c | 0.29 bc | 0.040 ab | 83.3 | 32.5 | 151 c | 15.2 c | 27.3 | |

| ANOVA | ||||||||||||

| R | ns | ns | ns | ns | *** | *** | ns | ns | *** | ns | *** | |

| MI | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | *** | ** | *** | ns | ns | ns | |

| R × MI | ns | ns | ns | *** | *** | *** | ns | ns | ** | *** | ns | |

| Rootstock (R) | 2023 | |||||||||||

| 140Ru | 2.27 | 0.111 | 0.64 | 1.63 | 0.35 | 0.017 | 65.2 | 28.3 | 133 | 18.3 | 48.9 | |

| 110R | 2.25 | 0.111 | 0.62 | 1.60 | 0.29 | 0.016 | 63.4 | 28.0 | 119 | 20.2 | 48.2 | |

| Microbial inoculation (MI) | ||||||||||||

| I | 2.26 | 0.116 | 0.68 | 1.63 | 0.34 | 0.016 | 66.0 | 28.7 | 134 | 23.4 | 52.9 | |

| NI | 2.26 | 0.108 | 0.58 | 1.59 | 0.30 | 0.018 | 62.5 | 27.6 | 119 | 15.2 | 44.1 | |

| R × MI | ||||||||||||

| 140Ru | I | 2.27 | 0.116 | 0.66 | 1.72 b | 0.38 b | 0.016 | 65.5 | 26.9 a | 141 | 19.3 a | 57.3 |

| NI | 2.27 | 0.107 | 0.62 | 1.53 a | 0.32 a | 0.019 | 64.8 | 29.7 ab | 126 | 17.4 a | 40.4 | |

| 110R | I | 2.26 | 0.115 | 0.71 | 1.54 a | 0.29 a | 0.015 | 66.6 | 30.4 b | 127 | 27.4 b | 48.6 |

| NI | 2.25 | 0.109 | 0.54 | 1.65 ab | 0.29 a | 0.017 | 60.2 | 25.5 a | 111 | 13.0 a | 47.8 | |

| ANOVA | ||||||||||||

| R | ns | ns | ns | ns | *** | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | |

| MI | ns | *** | ** | ns | ** | ns | ns | ns | ns | *** | ns | |

| R × MI | ns | ns | ns | * | * | ns | ns | *** | ns | ** | ns | |

| Main Shoot Length (cm) | TLA (m2 Vine−1) | PW (kg Vine−1) | Yield (kg Vine−1) | Number of Clusters Vine−1 | Cluster Weight (g) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rootstock (R) | 2018 | |||||

| 140Ru | 101 b | 1.42 b | 0.24 | 0.79 b | 4.4 b | 184 |

| 110R | 78 a | 1.11 a | 0.22 | 0.35 a | 2.4 a | 147 |

| 161-49C | 77 a | 1.15 a | 0.25 | 0.32 a | 2.1 a | 129 |

| Microbial inoculation (MI) | ||||||

| I | 88 | 1.20 | 0.28 | 0.47 | 2.9 | 153 |

| NI | 82 | 1.26 | 0.19 | 0.50 | 3.0 | 154 |

| ANOVA | ||||||

| R | ** | *** | ns | *** | *** | ns |

| MI | ns | ns | *** | ns | ns | ns |

| R × MI | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Rootstock | 2019 | |||||

| 140Ru | 68 | 1.75 | 0.19 b | 2.27 b | 17.4 | 131 ab |

| 110R | 67 | 1.61 | 0.15 a | 1.75 a | 15.1 | 118 a |

| 161-49C | 78 | 2.08 | 0.17 ab | 2.42 b | 16.4 | 146 b |

| Microbial inoculation (MI) | ||||||

| I | 76 | 2.00 | 0.18 | 2.33 | 16.4 | 144 |

| NI | 66 | 1.62 | 0.16 | 1.96 | 16.1 | 119 |

| ANOVA | ||||||

| R | ns | ns | ** | *** | ns | *** |

| MI | * | ns | ns | * | ns | *** |

| R × MI | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Rootstock (R) | 2020 | |||||

| 140Ru | 94 b | 2.88 b | 0.41 | 2.68 b | 11.3 b | 212 b |

| 110R | 83 a | 2.37 a | 0.40 | 2.02 a | 9.8 a | 188 a |

| 161-49C | 95 b | 2.97 b | 0.45 | 2.81 b | 11.6 b | 221 b |

| Microbial inoculation (MI) | ||||||

| I | 96 | 3.02 | 0.44 | 2.87 | 12.0 | 219 |

| NI | 85 | 2.46 | 0.40 | 2.14 | 9.7 | 195 |

| ANOVA | ||||||

| R | *** | *** | ns | *** | * | *** |

| MI | *** | *** | ns | *** | *** | *** |

| R × MI | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Rootstock (R) | 2021 | |||||

| 140Ru | 113 b | 3.72 b | 0.41 b | 3.37 b | 17.8 b | 178 b |

| 110R | 95 a | 2.95 a | 0.36 ab | 3.17 b | 18.5 b | 161 b |

| 161-49C | 91 a | 2.98 a | 0.33 a | 2.09 a | 15.9 a | 115 a |

| Microbial inoculation (MI) | ||||||

| I | 103 | 3.17 | 0.39 | 3.10 | 17.7 | 159 |

| NI | 97 | 3.26 | 0.34 | 2.67 | 17.2 | 144 |

| ANOVA | ||||||

| R | *** | * | *** | *** | ** | *** |

| MI | ns | ns | ** | ** | ns | ** |

| R × MI | ns | * | ** | ** | ns | ns |

| Rootstock (R) | 2022 | |||||

| 140Ru | 83 b | 2.86 | 0.38 b | 3.35 b | 16.0 b | 188 |

| 110R | 77 | 2.76 | 0.27 a | 1.77 a | 11.4 a | 297 |

| 161-49C | 66 a | 2.42 | 0.26 a | 1.71 a | 10.5 a | 142 |

| Microbial inoculation (MI) | ||||||

| I | 74 | 2.77 | 0.31 | 2.36 | 13.0 | 263 |

| NI | 77 | 2.59 | 0.29 | 2.20 | 12.3 | 155 |

| ANOVA | ||||||

| R | *** | ns | *** | *** | *** | ns |

| MI | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| R × MI | ** | ** | ** | ns | ns | ns |

| Rootstock (R) | 2023 | |||||

| 140Ru | 99 | 2.66 | 0.37 | 2.95 b | 13.7 b | 191 c |

| 110R | 73 | 1.84 | 0.30 | 2.57 b | 14.2 b | 162 b |

| 161-49C | - | - | - | 1.96 a | 11.7 a | 140 a |

| Microbial inoculation (MI) | ||||||

| I | 86 | 2.48 | 0.33 | 2.52 | 12.7 | 169 |

| NI | 87 | 2.02 | 0.34 | 2.47 | 13.7 | 160 |

| ANOVA | ||||||

| R | *** | * | * | *** | ** | *** |

| MI | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| R × MI | ns | ns | * | *** | ** | *** |

| Rootstock (R) | Berry Weight | CI | TSS | TA | MI | pH | Malic Acid | Tartaric Acid | Glucose | Fructose | Anthocyanins/TSS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 140Ru | 1.88 b | 3.99 a | 21.83 a | 3.60 b | 70 a | 4.20 b | 2.00 b | 3.26 | 146 ab | 156 ab | 19.1 a |

| 110R | 1.84 b | 4.66 b | 22.65 b | 3.43 a | 77 b | 4.21 b | 1.64 a | 3.37 | 160 b | 168 b | 23.6 b |

| 161-49C | 1.68 a | 4.38 b | 21.59 a | 3.52 ab | 71 a | 4.09 a | 1.54 a | 3.27 | 137 a | 144 a | 26.2 b |

| Microbial inoculation (MI) | |||||||||||

| I | 1.84 | 4.33 | 22.09 | 3.47 | 73 | 4.17 | 1.71 | 3.30 | 151 | 159 | 22.1 |

| NI | 1.77 | 4.36 | 21.97 | 3.56 | 72 | 4.16 | 1.74 | 3.31 | 144 | 153 | 23.8 |

| Year | |||||||||||

| 2018 | 1.87 bc | 4.64 b | 22.70 c | 4.23 c | 54 a | 4.17 ab | 3.03 d | 3.89 c | - | - | 11.1 a |

| 2020 | 1.92 bc | 4.16 b | 24.98 d | 4.27 c | 58 a | 4.18 ab | 1.74 c | 3.64 c | - | - | 16.2 a |

| 2021 | 1.47 a | 4.25 b | 19.10 a | 3.89 b | 54 a | 4.06 a | 1.59 bc | 3.06 b | 165 b | 182 b | 35.7 b |

| 2022 | 1.96 c | 3.56 a | 23.13 c | 2.64 a | 114 c | 4.16 ab | 0.85 a | 1.27 a | 143 a | 146 a | 16.1 a |

| 2023 | 1.79 b | 5.12 c | 20.92 b | 2.54 a | 83 b | 4.26 b | 1.43 b | 4.65 d | 135 a | 139 a | 35.8 b |

| ANOVA | |||||||||||

| R | *** | *** | *** | ** | *** | * | *** | ns | * | * | *** |

| MI | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Year | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| R × MI | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| Rootstock (R) | TPI | Extractable Polyphenols | Extractable Anthocyanins | Total Tannins | K | Mg | P | Zn |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 140Ru | 13.6 a | 30.9 a | 230 a | 2.28 a | 2167 c | 101.9 b | 185 a | 0.28 a |

| 110R | 13.9 ab | 31.4 a | 270 b | 1.93 a | 2045 b | 98.8 ab | 187 a | 0.29 a |

| 161-49C | 15.4 b | 42.3 b | 284 b | 2.80 b | 1943 a | 94.8 a | 209 b | 0.35 b |

| Microbial inoculation (MI) | ||||||||

| I | 13.5 | 32.1 | 250 | 2.11 | 2056 | 99.0 | 189 | 0.29 |

| NI | 15.1 | 37.7 | 273 | 2.56 | 2048 | 98.0 | 198 | 0.32 |

| Year | ||||||||

| 2018 | 19.9 d | 39.8 b | 137 a | 2.06 ab | 2804 e | 113.6 c | 223 b | 0.31 b |

| 2020 | 12.2 b | 24.4 a | 193 b | 1.53 a | 2259 d | 105.8 b | 250 c | 0.44 d |

| 2021 | 13.5 b | 43.1 b | 335 c | 3.30 c | 1350 a | 85.8 a | 159 a | 0.28 b |

| 2022 | 9.8 a | 24.1 a | 207 b | 2.36 b | 2014 c | 104.3 b | 175 a | 0.39 c |

| 2023 | 16.1 c | 42.9 b | 436 d | 2.43 b | 1831 b | 82.9 a | 161 a | 0.099 a |

| ANOVA | ||||||||

| R | * | * | ** | ** | *** | ** | *** | ** |

| MI | * | * | * | * | ns | ns | * | * |

| Year | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| R × MI | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | * | ns | ns |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Romero, P.; Botía, P.; Morote, E.I.; Morte, A.; Navarro, J.M. Microbial Inoculation Differentially Affected the Performance of Field-Grown Young Monastrell Grapevines Under Semiarid Conditions, Depending on the Rootstock. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2570. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112570

Romero P, Botía P, Morote EI, Morte A, Navarro JM. Microbial Inoculation Differentially Affected the Performance of Field-Grown Young Monastrell Grapevines Under Semiarid Conditions, Depending on the Rootstock. Agronomy. 2025; 15(11):2570. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112570

Chicago/Turabian StyleRomero, Pascual, Pablo Botía, Elisa I. Morote, Asunción Morte, and Josefa M. Navarro. 2025. "Microbial Inoculation Differentially Affected the Performance of Field-Grown Young Monastrell Grapevines Under Semiarid Conditions, Depending on the Rootstock" Agronomy 15, no. 11: 2570. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112570

APA StyleRomero, P., Botía, P., Morote, E. I., Morte, A., & Navarro, J. M. (2025). Microbial Inoculation Differentially Affected the Performance of Field-Grown Young Monastrell Grapevines Under Semiarid Conditions, Depending on the Rootstock. Agronomy, 15(11), 2570. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112570