Effects of Allelic Variation in Storage Protein Genes on Seed Composition and Agronomic Traits of Soybean in the Omsk Oblast of Western Siberia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Soy Collection

2.2. Field Observations and Analysis of Seed Composition

2.3. Soybean DNA Extraction and Collection Genotyping

2.4. Statistical Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Phenotyping

3.2. Genotyping and Phenotypic Expression of the Studied Loci

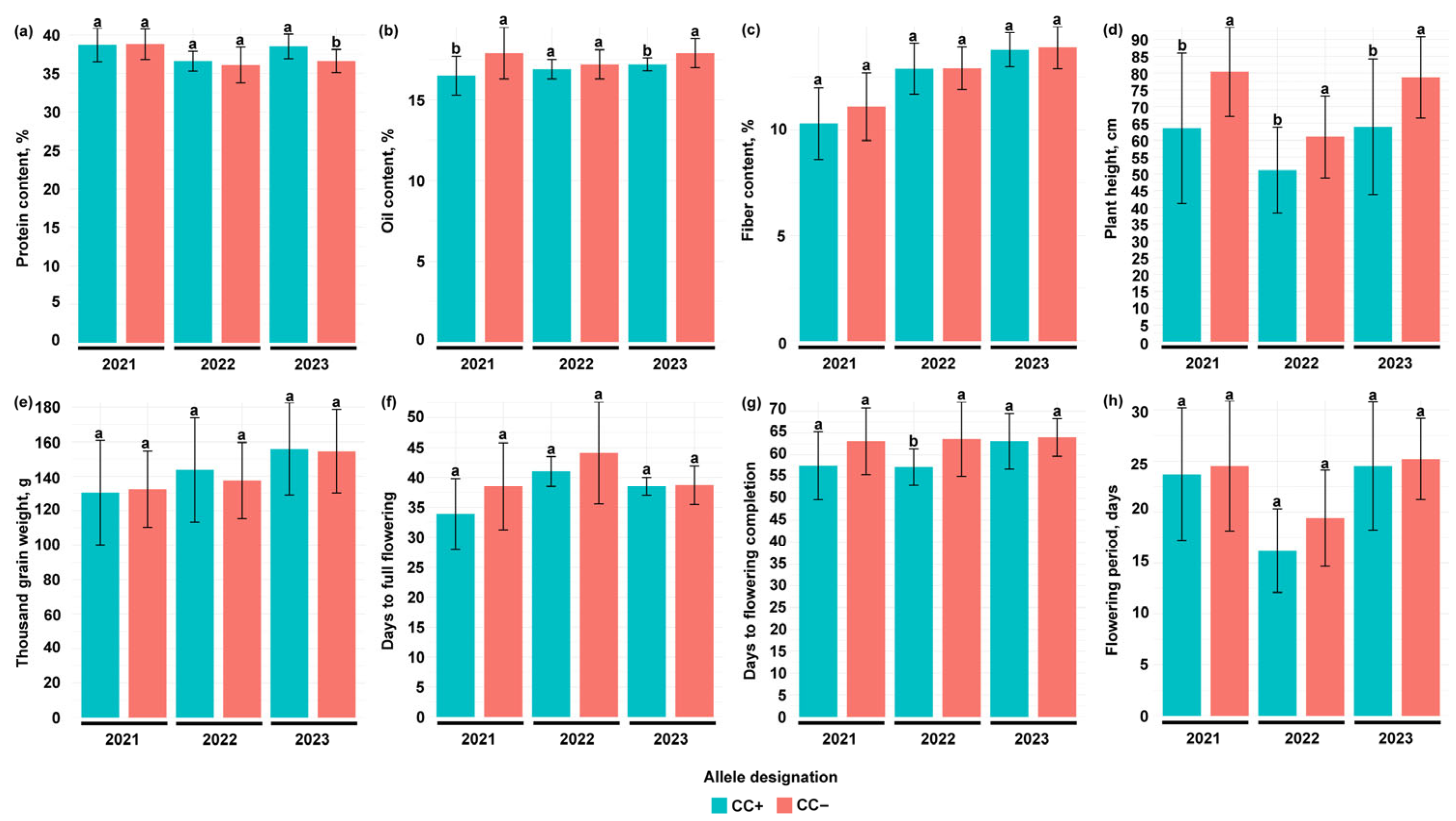

3.2.1. GmSWEET39

3.2.2. Glyma.17G074400

3.2.3. Glyma.14G119000

3.2.4. Glyma.03G219900

3.2.5. POWR1

4. Discussion

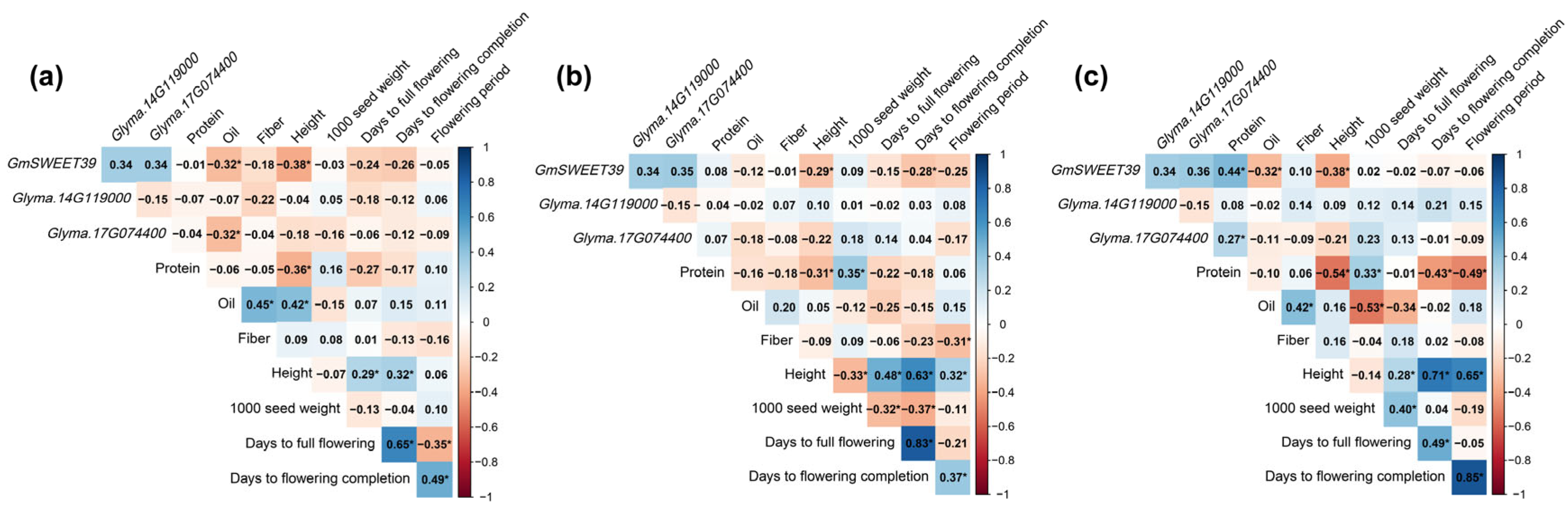

4.1. Correlations Between the Studied Traits

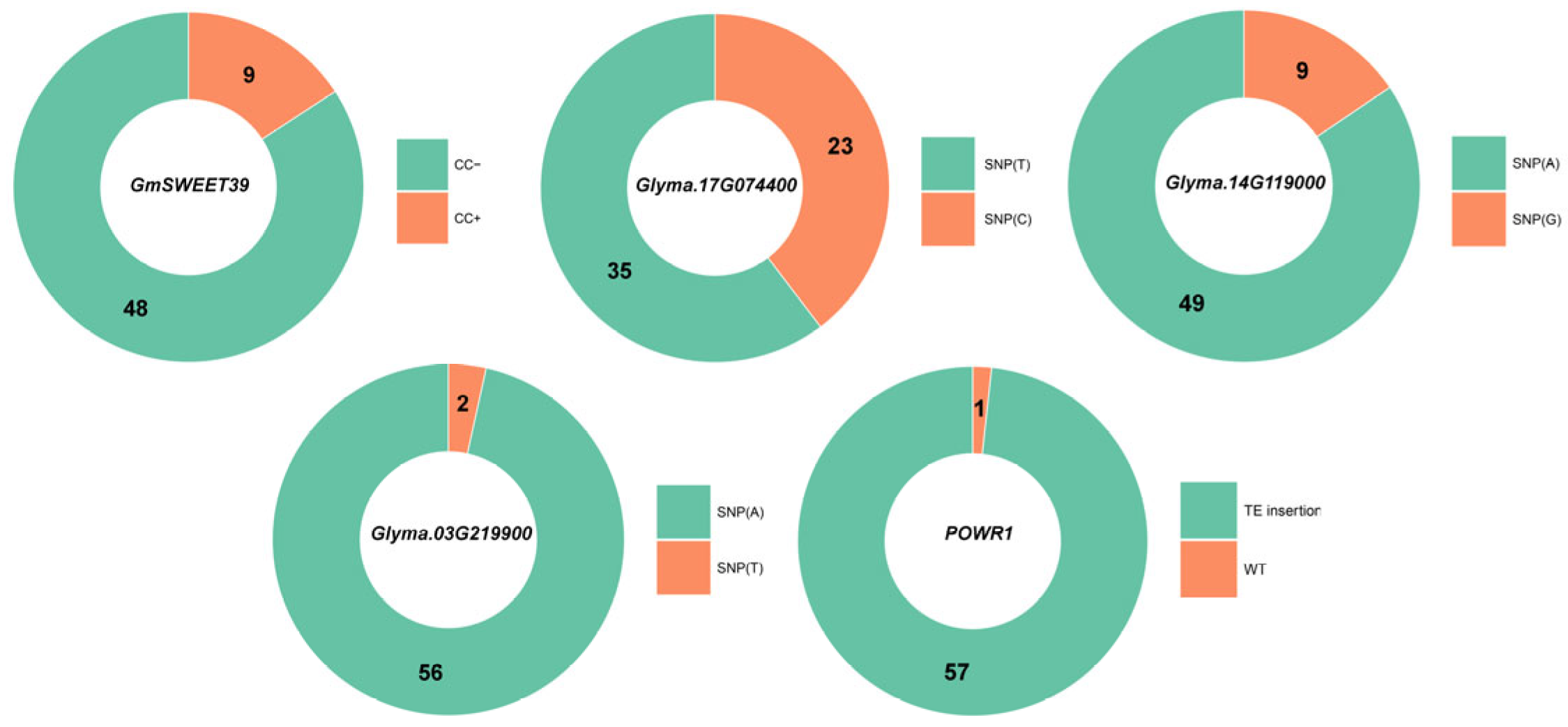

4.2. Genotypic Structure of the Collection

4.3. Effect of Allelic Variation in GmSWEET39, Glyma.14G119000 and Glyma.17G074400 Genes on Agronomic and Quality Traits in Soybean

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Qiao, Y.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Sun, Y.; Feng, Z. Fermented soybean foods: A review of their functional components, mechanism of action and factors influencing their health benefits. Food Res. Int. 2022, 158, 111575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, P.; Wang, T.; Luo, Y. A review on plant-based proteins from soybean: Health benefits and soy product development. J. Agric. Food Res. 2022, 7, 100265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modgil, R.; Tanwar, B.; Goyal, A.; Kumar, V. Soybean (Glycine max). In Oilseeds: Health Attributes and Food Applications; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Duarte, M.E.; Jang, K.B.; Kim, S.W. Soy protein concentrate replacing animal protein supplements and its impacts on intestinal immune status, intestinal oxidative stress status, nutrient digestibility, mucosa-associated microbiota, and growth performance of nursery pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 2022, 100, skac255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toomer, O.T.; Oviedo, E.O.; Ali, M.; Patino, D.; Joseph, M.; Frinsko, M.; Mian, R. Current agronomic practices, harvest & post-harvest processing of soybeans (Glycine max)—A review. Agronomy 2023, 13, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Xu, M.; Lu, J.; Cai, G. Simultaneous microbial fermentation and enzymolysis: A biotechnology strategy to improve the nutritional and functional quality of soybean meal. Food Rev. Int. 2024, 40, 1296–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witkowski, M.; Grajeta, H.; Gomułka, K. Hypersensitivity reactions to food additives—Preservatives, antioxidants, flavor enhancers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdo, E.M.; Shaltout, O.E.; Mansour, H.M. Natural antioxidants from agro-wastes enhanced the oxidative stability of soybean oil during deep-frying. LWT 2023, 173, 114321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinegovskaya, V.T. Scientific provision of an effective development of soybean breeding and seed production in the Russian Far East. Vavilov J. Genet. Breed. 2021, 4, 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zotikov, V.I.; Vilyunov, S.D. Present-day breeding of legumes and groat crops in Russia. Vavilov J. Genet. Breed. 2021, 4, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishnyakova, M.A.; Seferova, I.V.; Samsonova, M.G. Genetic sources required for soybean breeding in the context of new biotechnologies. Sel’skokhozyaistvennaya Biol. 2017, 5, 905–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, C.C.; Chen, P. The numbers game of soybean breeding in the United States. Crop Breed. Appl. Biotechnol. 2021, 21, e387521S10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosaz, L.B.; Gerde, J.A.; Borrás, L.; Cipriotti, P.A.; Ascheri, L.; Campos, M.; Gallo, S.; Rotundo, J.L. Management and environmental factors explaining soybean seed protein variability in central Argentina. Field Crops Res. 2019, 240, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelaya Arce, M.S.; Lago Tagliapietra, E.L.; Minussi Winck, J.E.; Ferigolo Alves, A.; Schmidt Dalla Porta, F.; Broilo Facco, T.; Streck, N.A.; Fornalski Soares, M.; Da Encarnação Ferrão, G.; Debona, D.; et al. Assessing genetics, biophysical, and management factors related to soybean seed protein variation in Brazil. Eur. J. Agron. 2025, 165, 127541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Yang, X.; Sun, S.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; Jia, H.; Man, W.; Fu, L.; Song, W.; Wu, C.; et al. Temporal–Spatial Characterization of Seed Proteins and Oil in Widely Grown Soybean Cultivars across a Century of Breeding in China. Crop Sci. 2017, 2, 748–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilawari, R.; Kaur, N.; Priyadarshi, N.; Prakash, I.; Patra, A.; Mehta, S.; Singh, B.; Jain, P.; Islam, M.A. Soybean: A Key Player for Global Food Security. In Soybean Improvement: Physiological, Molecular and Genetic Perspectives; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdala, L.J.; Otegui, M.E.; Di Mauro, G. On-farm soybean genetic progress and yield stability during the early 21st century: A case study of a commercial breeding program in Argentina and Brazil. Field Crops Res. 2024, 308, 109277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesz Junior, V.J. Soybean production in Paraguay: Agribusiness, economic change and agrarian transformations. J. Agrar. Change 2022, 22, 317–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, A.; Kumar, V. Soybean Breeding. In Fundamentals of Field Crop Breeding; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 907–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoosefzadeh-Najafabadi, M.; Rajcan, I. Six decades of soybean breeding in Ontario, Canada: A tradition of innovation. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2023, 4, 333–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, R.W.; Grainger, C.M.; Ficht, A.; Eskandari, M.; Rajcan, I. Trends in Soybean Trait Improvement over Generations of Selective Breeding. Crop Sci. 2019, 5, 1870–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Available online: https://www.fao.org/land-water/databases-and-software/crop-information/soybean/en/ (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Klychova, G.S.; Tsypin, A.P.; Valiev, A.R. Prospects for the soybean market development and its importance for the Russian economy. J. Kazan State Agrar. Univ. 2021, 3, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unified Interdepartmental Information and Statistical System (Russia). Available online: https://www.fedstat.ru/ (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Potapova, N.A.; Zlobin, A.S.; Perfil’ev, R.N.; Vasiliev, G.V.; Salina, E.A.; Tsepilov, Y.A. Population Structure and Genetic Diversity of the 175 Soybean Breeding Lines and Varieties Cultivated in West Siberia and Other Regions of Russia. Plants 2023, 19, 3490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroupin, P.Y.; Omel’yAnuk, L.V.; Samarina, M.A.; Arkhipov, A.V.; Asanov, A.M.; Ulyanov, D.S.; Bursakov, S.A.; Zlobnova, N.V.; Karlov, G.I.; Mukhordova, M.E.; et al. Analysis of the Allelic Structure of Photoperiodism Genes E1–E4 in Soybean Collections and Its Impact on the Timing and Duration of Flowering under the Growing Conditions of the Omsk Oblast. Nanobiotechnol. Rep. 2024, 5, 781–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staniak, M.; Szpunar-Krok, E.; Kocira, A. Responses of Soybean to Selected Abiotic Stresses—Photoperiod, Temperature and Water. Agriculture 2023, 13, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perfil’ev, R.; Shcherban, A.; Potapov, D.; Maksimenko, K.; Kiryukhin, S.; Gurinovich, S.; Panarina, V.; Polyudina, R.; Salina, E. Impact of Allelic Variation in Maturity Genes E1–E4 on Soybean Adaptation to Central and West Siberian Regions of Russia. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee Tian, H.; Yin, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, Z.; Feng, S.; Jin, S.; Han, X.; Yang, M.; Xu, C.; Hu, L.; et al. Identification of HSSP1 as a regulator of soybean protein content through QTL analysis and Soy—SPCC network. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2025, 23, 2673–2688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Pan, X.; Wang, F.; Liu, C.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Q. Novel QTL and Meta-QTL Mapping for Major Quality Traits in Soybean. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 12, 774270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Mao, L.; Zeng, Z.; Yu, X.; Lian, J.; Feng, J.; Yang, W.; An, J.; Wu, H.; Zhang, M.; et al. Genetic mapping high protein content QTL from soybean ‘Nanxiadou 25’ and candidate gene analysis. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 21, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Zhou, L.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Chen, Z.; Li, X.; Qian, Q.; Kong, F.; Li, Y.; Liu, X.; et al. The gibberellin signaling negative regulator RGA-LIKE3 promotes seed storage protein accumulation. Plant Physiol. 2021, 185, 1697–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Derynck, M.R.; Li, X.; Telmer, P.; Marsolais, F.; Dhaubhadel, S. A single-repeat MYB transcription factor, GmMYB176, regulates CHS8 gene expression and affects isoflavonoid biosynthesis in soybean. Plant J. 2010, 62, 1019–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Yu, J.; Yan, W.; Zhang, J.; Yang, D.; Yao, G.; Liu, Z.; Wu, Y.; Hou, X. Integrative iTRAQ-based proteomic and transcriptomic analysis reveals the accumulation patterns of key metabolites associated with oil quality during seed ripening of Camellia oleifera. Hortic. Res. 2021, 8, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Fu, D.Q.; El-Habbak, M.; Navarre, D.; Ghabrial, S.; Kachroo, A. Silencing genes encoding omega-3 fatty acid desaturase alters seed size and accumulation of bean pod mottle virus in soybean. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2011, 24, 506–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshino, T.; Watanabe, S.; Takagi, Y.; Anai, T. A novel GmFAD3-2a mutant allele developed through TILLING reduces alphalinolenic acid content in soybean seed oil. Breed. Sci. 2014, 64, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Guo, C.; Feng, X.; Wang, J.; Pan, W.; Xu, C.; Wei, S.; Han, X.; Yang, M.; Chen, Q.; et al. Development and Validation of Kompetitive Allele-Specific Polymerase Chain Reaction Markers for Seed Protein Content in Soybean. Plants 2024, 13, 3485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Goettel, W.; Song, Q.; Jiang, H.; Hu, Z.; Wang, M.L.; An, Y.Q.C. Selection of GmSWEET39 for oil and protein improvement in soybean. PLoS Genet. 2020, 16, e1009114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, L.; Yang, S.; Zhang, K.; He, J.; Wu, C.; Ren, Y.; Gai, J.; Li, Y. Natural variation and selection in GmSWEET39 affect soybean seed oil content. New Phytol. 2020, 225, 1651–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Liu, S.; Wang, J.; Yokosho, K.; Zhou, B.; Yu, Y.C.; Tian, Z. Simultaneous changes in seed size, oil content and protein content driven by selection of SWEET homologues during soybean domestication. Nat. Sci. Rev. 2020, 7, 1776–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiwari, S.B.; Shen, Y.; Chang, H.C.; Hou, Y.; Harris, A.; Ma, S.F.; Ratcliffe, O.J. The flowering time regulator CONSTANS is recruited to the FLOWERING LOCUS T promoter via a unique cis-element. New Phytol. 2010, 187, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goettel, W.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Qiao, Z.; Jiang, H.; Hou, D.; Song, Q.; Pantalone, V.R.; Song, B.H.; Yu, D.; et al. POWR1 is a domestication gene pleiotropically regulating seed quality and yield in soybean. Nat. Com. 2022, 13, 3051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, Y.; Yao, S.; Crawford, G.W.; Fang, H.; Lang, J.; Fan, J.; Jiang, H. Selection for oil content during soybean domestication revealed by X-ray tomography of ancient beans. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 43595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.A.; Crawford, G.W.; Liu, L.; Sasaki, Y.; Chen, X. Archaeological soybean (Glycine max) in East Asia: Does size matter? PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e26720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, J.W.; Offler, C.E. Compartmentation of transport and transfer events in developing seeds. J. Exp. Bot. 2001, 52, 551–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobko, O.; Zikeli, S.; Claupein, W.; Gruber, S. Seed yield, seed protein, oil content, and agronomic characteristics of soybean (Glycine max L. Merrill) depending on different seeding systems and cultivars in Germany. Agronomy 2022, 7, 1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremner, J.M. Determination of nitrogen in soil by the Kjeldahl method. J. Agric. Sci. 1960, 55, 11–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancheno Cárdenas, M.X.; Cajamarca Rivadeneira, X.J.; Brito López, P.G. Analysis of Steam Explosion as a Pretreatment Strategy in the Extraction of Soybean Seed Oil (Glycine max L.). In Systems, Smart Technologies, and Innovation for Society; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Volume 1331, pp. 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GOST 31675-2012 Feed. Methods for Determination of Crude Fiber. Available online: https://internet-law.ru/gosts/gost/52702/?ysclid=mfuz1lnlfx86481027 (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Rogers, S.O.; Bendich, A.J. Extraction of DNA from milligram amounts of fresh, herbarium and mummified plant tissues. Plant Mol. Biol. 1985, 5, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashrafi-Dehkordi, E.; Mazloomi, S.M.; Hemmati, F. A comparison of DNA extraction methods and PCR-based detection of GMO in textured soy protein. J. Consum. Prot. Food Saf. 2021, 16, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pwr: Basic Functions for Power Analysis in R. Available online: https://github.com/heliosdrm/pwr (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Package Car. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/car/index.html (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Package Factoextra. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/factoextra/index.html (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Package Corrplot. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/corrplot/ (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Package Ggplot2. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/ggplot2/index.html (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- STATISTICA v.8. Available online: https://docs.tibco.com/products/tibco-statistica-14-0-1 (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Chandrawat, K.S.; Baig, K.S.; Sarang, D.H.; KiihneDumai, P.H.; Dhone, P.U.; Kumar, A. Association analysis for yield contributing and quality parameters in soybean. Int. J. Envion. Sci. 2015, 2, 113–118. [Google Scholar]

- Haghi, Y.; Boroomandan, P.; Moradin, M.; Hassankhali, M.; Farhadi, P.; Farsaei, F.; Dabiri, S. Correlation and path analysis for yield, oil and protein content of Soybean (Glycine max L.) genotypes under different levels of nitrogen starter and plant density. Biharean Biol. 2012, 1, 32–37. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, M.F.A.; Ashraf, M.; Qureshi, A.S.; Ghafoor, A. Assessment of genetic variability, correlation and path analyses for yield and its components in soybean. Pakistan J. Bot. 2007, 2, 405. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, A.M.; Wilcox, J.R. Genetic and phenotypic associations of agronomic characteristics in four high protein soybean populations 1. Crop Sci. 1983, 6, 1077–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carciochi, W.D.; Schwalbert, R.; Andrade, F.H.; Corassa, G.M.; Carter, P.; Gaspar, A.P.; Schmidt, J.; Ciampitti, I.A. Soybean Seed Yield Response to Plant Density by Yield Environment in North America. Agron. J. 2019, 4, 1923–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State Register of Breeding Achievements of the Russian Federation. Available online: https://gossortrf.ru (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Nekrasov, A.Y. Soybean: Sources from the VIR collection of genetic resources. Proc. Appl. Bot. Genet. Breed. 2022, 181, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belyshkina, M.; Zagoruiko, M.; Mironov, D.; Bashmakov, I.; Rybalkin, D.; Romanovskaya, A. The Study of Possible Soybean Introduction into New Cultivation Regions Based on the Climate Change Analysis and the Agro-Ecological Testing of the Varieties. Agronomy 2023, 13, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Regenstein, J.M.; Zhou, L.; Wang, Z. Soy protein isolates: A review of their composition, aggregation, and gelation. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 2, 1940–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.S.; Du, M.; Zhang, Q.Y.; Wang, G.H.; Hashemi, M.; Liu, X.B. Greater differences exist in seedprotein, oil, total soluble sugar and sucrosecontentof vegetable soybean genotypes [‘Glycine max’(L.) Merrill] in Northeast China. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 2012, 6, 1681–1686. [Google Scholar]

- Straková, E.; Suchý, P.; Večerek, V.; Šerman, V.; Mas, N.; Jůzl, M. Nutritional composition of seeds of the genus Lupinus. Acta Vet. Brno 2006, 4, 489–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhungana, S.K.; Kulkarni, K.P.; Kim, M.; Ha, B.-K.; Kang, S.; Song, J.T.; Shin, D.-H.; Lee, J.-D. Environmental Stability and Correlation of Soybean Seed Starch with Protein and Oil Contents. Plant Breed. Biotechnol. 2017, 4, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Song, Q.; Cregan, P.B.; Nelson, R.L.; Wang, X.; Wu, J.; Jiang, G.-L. Genome-wide association study for flowering time, maturity dates and plant height in early maturing soybean (Glycine max) germplasm. BMC Genom. 2016, 16, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosso, M.L.; Zhang, B.; Williams, M.M.; Fu, X.; Ross, J. Editorial: Everything edamame: Biology, production, nutrition, sensory and economics, volume II. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1488772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phokas, A.; Coates, J.C. Evolution of DELLA function and signaling in land plants. Evol. Dev. 2021, 23, 137–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribera, L.M.; Aires, E.S.; Neves, C.S.; Fernandes, G.D.C.; Bonfim, F.P.G.; Rockenbach, R.I.; Rodrigues, J.D.; Ono, E.O. Assessment of the Physiological Response and Productive Performance of Vegetable vs. Conventional Soybean Cultivars for Edamame Production. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Sun, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, N.; Li, T.; Dong, H.; Yang, M.; Xu, C.; Hu, L.; Liu, C.; et al. Soybean Oil and Protein: Biosynthesis, Regulation and Strategies for Genetic Improvement. Plant Cell Environ. 2024; Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Yu, Y.; Wang, S.; Lian, Y.; Wang, T.; Wei, Y.; Gong, P.; Liu, X.; Fang, X.; Zhang, M. QTL Mapping of Isoflavone, Oil and Protein Contents in Soybean (Glycine max L. Merr.). Agric. Sci. China 2010, 8, 1108–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyary, J.; Kuroda, Y.; Kaga, A.; Tomooka, N.; Yano, H.; Takada, Y.; Kato, S.; Vaughan, D. QTL affecting fitness of hybrids between wild and cultivated soybeans in experimental fields. Ecol. Evol. 2013, 7, 2150–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, F.; Kamal, G.M.; Nadeem, F.; Shabir, G. Variations of quality characteristics among oils of different soybean varieties. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2016, 4, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assefa, Y.; Purcell, L.C.; Salmeron, M.; Naeve, S.; Casteel, S.N.; Kovács, P.; Archontoulis, S.; Licht, M.; Below, F.; Kandel, H.; et al. Assessing Variation in US Soybean Seed Composition (Protein and Oil). Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO Soils Portal. Available online: https://www.fao.org/soils-portal/en/ (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- WMO (World Meteorological Organization). Available online: https://wmo.int/ (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- FAO GAUL (Global Administrative Unit Layers). Available online: https://www.fao.org/agroinformatics/news/news-detail/now-available--the-global-administrative-unit-layers-(gaul)-dataset---2024-edition/en (accessed on 22 September 2025).

| Target Locus and Detectable Alleles | Primers | Original Article of Marker/Gene Reference Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| GmSWEET39: CC−/CC+ | FAM: CATCCACTTCCTCTGCGATTGA HEX: CATCCACTTCCTCTGCGATTGG Common: ACATTGTTGTTGTGAACCCCTTG | [38] * |

| Glyma.03G219900: SNP(T/A) | FAM: AAGGCCTGATTGCATGGAGA HEX: AAGGCCTGATTGCATGGAGT Common: GGTTCACCAAGGAGGGTGAG | [37] |

| Glyma.14G119000: SNP(A/G) | FAM: AAAGGAACTTCTTTTTGTCCACTA HEX: AAAGGAACTTCTTTTTGTCCACTG Common: CTTCTTCGTCAGTGCAAGTGC | [37] |

| Glyma.17G074400: SNP(T/C) | FAM: CCCTGGTATCTTCTTCCTCTGGT HEX: CCCTGGTATCTTCTTCCTCTGGC Common: GTGTCGTCACTAAGAAATAATGATAAGG | [37] |

| POWR1: indel TE (1228 bp PCR product)/WT (907 bp PCR product) | F: CACTTCAAGGGTGGCAGTGTT R: CGGGATGGGAAAAGTGTCCTA | [42] |

| Loci | Allele | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Content, % | Oil Content, % | ||||||

| GmSWEET39 | CC+ | 38.7 a ± 2.2 | 36.6 a ± 1.3 | 38.5 a ± 1.6 | 16.5 b ±1.21 | 16.9 a ± 0.6 | 17.2 b ±0.4 |

| N | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | |

| CC− | 38.8 a ± 2 | 36.1 a ± 2.3 | 36.6 b ± 1.5 | 17.9 a ±1.6 | 17.2 a ± 0.9 | 17.9 a ±0.9 | |

| N | 48 | 48 | 46 | 46 | 46 | 44 | |

| CC+ vs. CC− | −0.1 pp | 0.5 pp | 1.9 pp | −1.4 pp | −0.3 pp | −0.7 pp | |

| r (CC+) | −0.01 | 0.08 | 0.44 * | −0.32 * | −0.12 | −0.32 * | |

| N | 57 | 57 | 55 | 55 | 55 | 53 | |

| Glyma.17G074400 | SNP(T) | 38.9 a ± 2.1 | 36.1 a ± 2.4 | 36.5 b ± 1.6 | 18.1 a ± 1.5 | 17.3 a ± 0.8 | 17.9 a ± 0.9 |

| N | 35 | 35 | 34 | 35 | 35 | 34 | |

| SNP(C) | 38.7 a ± 1.9 | 36.4 a ± 1.9 | 37.5 a ± 1.7 | 17.0 b ± 1.6 | 16.9 a ± 0.9 | 17.7 a ± 0.8 | |

| N | 23 | 23 | 22 | 21 | 21 | 20 | |

| SNP(T) vs. SNP(C) | 0.2 pp | −0.3 pp | −1.0 pp | 1.1 pp | 0.4 pp | 0.2 pp | |

| r (SNP(T)) | 0.04 | −0.07 | −0.27 * | 0.32 * | 0.18 | 0.11 | |

| N | 58 | 58 | 56 | 56 | 56 | 54 | |

| Fiber content, % | Plant height, cm | ||||||

| GmSWEET39 | CC+ | 10.3 a ± 1.7 | 12.90 a ± 1.2 | 13.8 a ± 0.8 | 63.6 b ± 22.4 | 51.1 b ± 12.8 | 64.0 b ± 20.2 |

| N | 48 | 48 | 46 | 9 | 9 | 9 | |

| CC− | 11.1 a ± 1.6 | 12.92 a ± 1.0 | 13.9 a ± 1.0 | 80.4 a ± 13.3 | 61.0 a ± 12.2 | 78.7 a ± 12.1 | |

| N | 44 | 48 | 48 | 48 | 48 | 46 | |

| CC+ vs. CC− | −0.8 pp | −0.02 pp | −0.1 pp | −16.8 (−23.3%) | −9.9 (−17.7%) | −14.7 (−20.6%) | |

| r (CC+) | −0.18 | −0.01 | −0.1 | −0.38 * | −0.29 * | −0.38 * | |

| N | 57 | 57 | 55 | 57 | 57 | 55 | |

| Glyma.17G074400 | SNP(T) | 11.1 a ± 1.5 | 13.0 a ± 1.1 | 13.9 a ± 0.9 | 80.2 a ± 12.7 | 61.6 a ± 11.8 | 79.0 a ± 12.3 |

| N | 35 | 34 | 34 | 35 | 35 | 34 | |

| SNP(C) | 10.9 a ± 1.8 | 12.8 a ± 1 | 13.8 a ± 1.1 | 74.4 a ± 19.9 | 56.4 a ± 13.4 | 72.8 a ± 17.2 | |

| N | 23 | 23 | 22 | 23 | 23 | 22 | |

| SNP(T) vs. SNP(C) | 0.2 pp | 0.2 pp | 0.1 pp | 5.8 (7.5%) | 5.2 (8.8%) | 6.2 (8.2%) | |

| r (SNP(T)) | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.18 | 0.20 | 0.21 | |

| N | 58 | 58 | 56 | 58 | 58 | 56 | |

| 1000 grain weight, g | Days to full flowering, days | ||||||

| GmSWEET39 | CC+ | 130.4 a ± 30.3 | 143.6 a ± 30.3 | 155.8 a ± 26.8 | 33.9 a ± 5.9 | 41.0 a ± 2.5 | 38.5 a ± 1.5 |

| N | 8 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 9 | |

| CC− | 132.4 a ± 22.2 | 137.5 a ± 22.1 | 154.4 a ± 24.2 | 38.5 a ± 7.3 | 44.1 a ± 8.5 | 38.7 a ± 3.2 | |

| N | 48 | 48 | 46 | 47 | 48 | 48 | |

| CC+ vs. CC− | −2.0 (−1.5%) | 6.1 (4.3%). | 1.4 (0.9%) | −4.6 (−12.7%) | −3.1 (−7.0%) | −0.2 (−0.5%) | |

| r (CC+) | −0.03 | 0.09 | 0.02 | −0.24 | −0.15 | −0.02 | |

| N | 56 | 56 | 54 | 56 | 57 | 57 | |

| Glyma.17G074400 | SNP(T) | 134.5 a ± 20.4 | 135.1 a ± 22.6 | 150.1 a ± 19.1 | 38.3 a ± 8 | 42.8 a ± 8.4 | 38.4 a ± 3.38 |

| N | 35 | 35 | 34 | 34 | 35 | 35 | |

| SNP(C) | 127.2 a ± 27 | 143.7 a ± 23.2 | 161.7 a ± 28.7 | 37.5 a ± 6.4 | 45.0 a ± 6.8 | 39.1 a ± 2.1 | |

| N | 22 | 22 | 21 | 23 | 23 | 23 | |

| SNP(T) vs. SNP(C) | 7.3 (5.7%) | −8.6 (−6.2%) | −11.6 (−7.4%) | 0.8 (−2.1%) | −2.2 (5%) | −0.7 (1.8%) | |

| r (SNP(T)) | 0.16 | −0.18 | −0.23 | 0.06 | −0.14 | −0.13 | |

| N | 57 | 57 | 55 | 57 | 58 | 58 | |

| Days to flowering completion, days | Flowering period, days | ||||||

| GmSWEET39 | CC+ | 57.5 a ± 7.8 | 57.2 b ± 4.2 | 63.1 a ± 6.4 | 23.7 a ± 6.5 | 16.2 a ± 4.1 | 24.5 a ± 6.3 |

| N | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | |

| CC− | 63.1 a ± 7.6 | 63.6 a ± 8.5 | 64.0 a ± 4.3 | 24.5 a ± 6.4 | 19.4 a ± 4.7 | 25.2 a ± 4 | |

| N | 47 | 48 | 48 | 47 | 48 | 48 | |

| CC+ vs. CC− | −5.6 (−9.3%) | −6.4 (−10.6%) | −0.9 (−1.4%) | −0.8 (−3.3%) | −3.2 (−18%) | −0.7 (−2.8%) | |

| r (CC+) | −0.26 | −0.28 * | −0.07 | −0.05 | −0.25 | −0.06 | |

| N | 56 | 57 | 57 | 56 | 57 | 57 | |

| Glyma.17G074400 | SNP(T) | 63.3 a ± 7.9 | 62.3 a ± 8.8 | 63.9 a ± 5.1 | 25.0 a ± 6.2 | 19.5 a ± 5.1 | 25.5 a ± 4.8 |

| N | 34 | 35 | 34 | 34 | 35 | 34 | |

| SNP(C) | 61.3 a ± 8.5 | 62.9 a ± 7.5 | 63.8 a ± 3.8 | 23.9 a ± 6.8 | 17.9 a ± 3.9 | 24.6 a ± 3.5 | |

| N | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 | |

| SNP(T) vs. SNP(C) | 2.0 (3.2%) | −0.6 (−1.0%) | 0.1 (0.2%) | 1.1 (−4.5%) | 1.6 (8.6%) | 0.9 (3.6%) | |

| r (SNP(T)) | 0.12 | −0.04 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.17 | 0.09 | |

| N | 57 | 58 | 58 | 57 | 58 | 58 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Strembovskiy, I.V.; Kroupin, P.Y.; Omel’yanuk, L.V.; Arkhipov, A.V.; Meglitskaya, Y.S.; Bazhenov, M.S.; Asanov, A.M.; Mukhordova, M.E.; Yusova, O.A.; Yaschenko, Y.I.; et al. Effects of Allelic Variation in Storage Protein Genes on Seed Composition and Agronomic Traits of Soybean in the Omsk Oblast of Western Siberia. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2533. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112533

Strembovskiy IV, Kroupin PY, Omel’yanuk LV, Arkhipov AV, Meglitskaya YS, Bazhenov MS, Asanov AM, Mukhordova ME, Yusova OA, Yaschenko YI, et al. Effects of Allelic Variation in Storage Protein Genes on Seed Composition and Agronomic Traits of Soybean in the Omsk Oblast of Western Siberia. Agronomy. 2025; 15(11):2533. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112533

Chicago/Turabian StyleStrembovskiy, Ilya V., Pavel Yu. Kroupin, Lyudmila V. Omel’yanuk, Andrey V. Arkhipov, Yana S. Meglitskaya, Mikhail S. Bazhenov, Akimbek M. Asanov, Mariya E. Mukhordova, Oksana A. Yusova, Yuliya I. Yaschenko, and et al. 2025. "Effects of Allelic Variation in Storage Protein Genes on Seed Composition and Agronomic Traits of Soybean in the Omsk Oblast of Western Siberia" Agronomy 15, no. 11: 2533. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112533

APA StyleStrembovskiy, I. V., Kroupin, P. Y., Omel’yanuk, L. V., Arkhipov, A. V., Meglitskaya, Y. S., Bazhenov, M. S., Asanov, A. M., Mukhordova, M. E., Yusova, O. A., Yaschenko, Y. I., Karlov, G. I., & Divashuk, M. G. (2025). Effects of Allelic Variation in Storage Protein Genes on Seed Composition and Agronomic Traits of Soybean in the Omsk Oblast of Western Siberia. Agronomy, 15(11), 2533. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112533