Harvesting Light: The Interrelation of Spectrum, Plant Density, Secondary Metabolites, and Cannabis sativa L. Yield

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

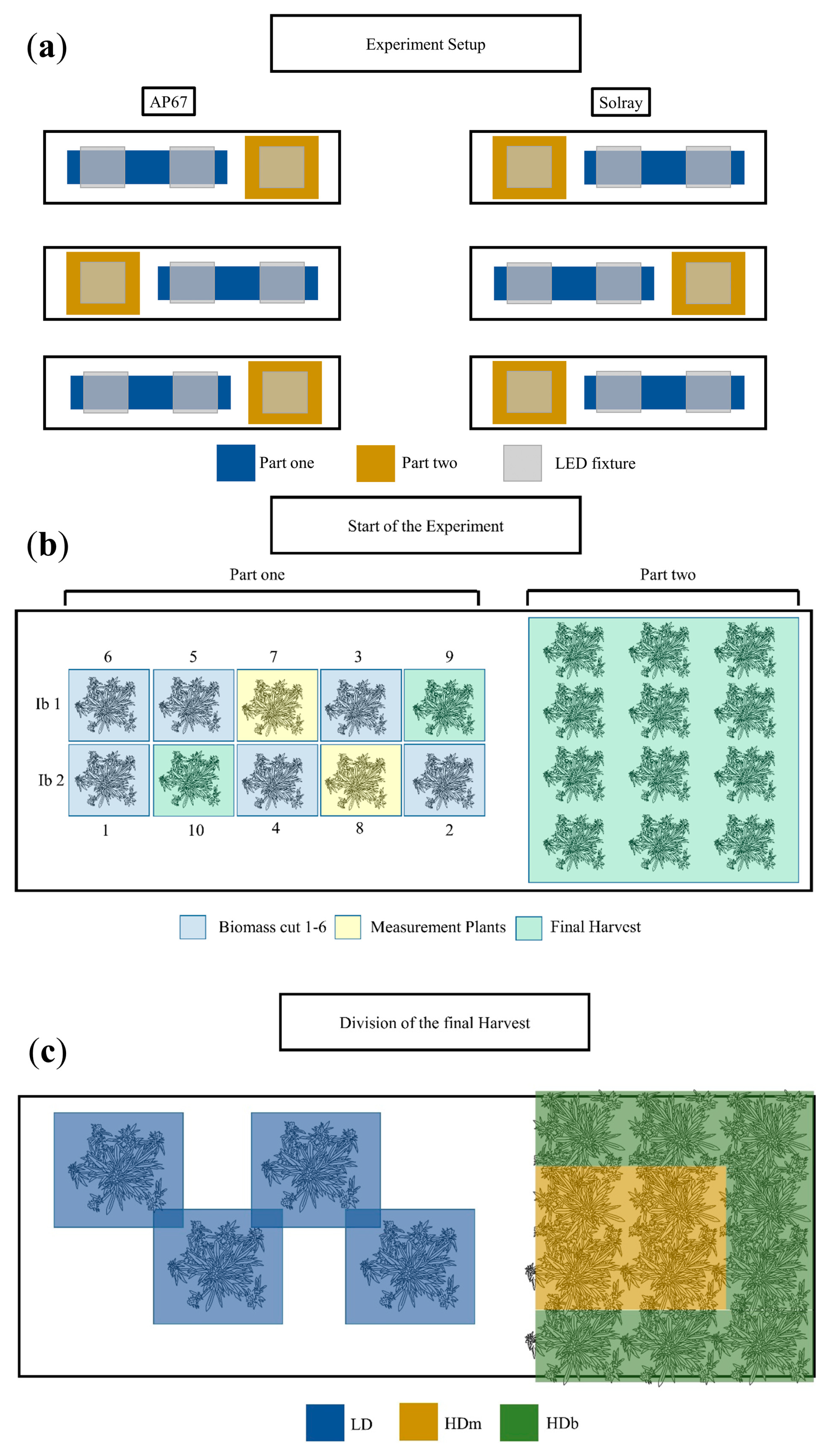

2.1. Experimental Setup

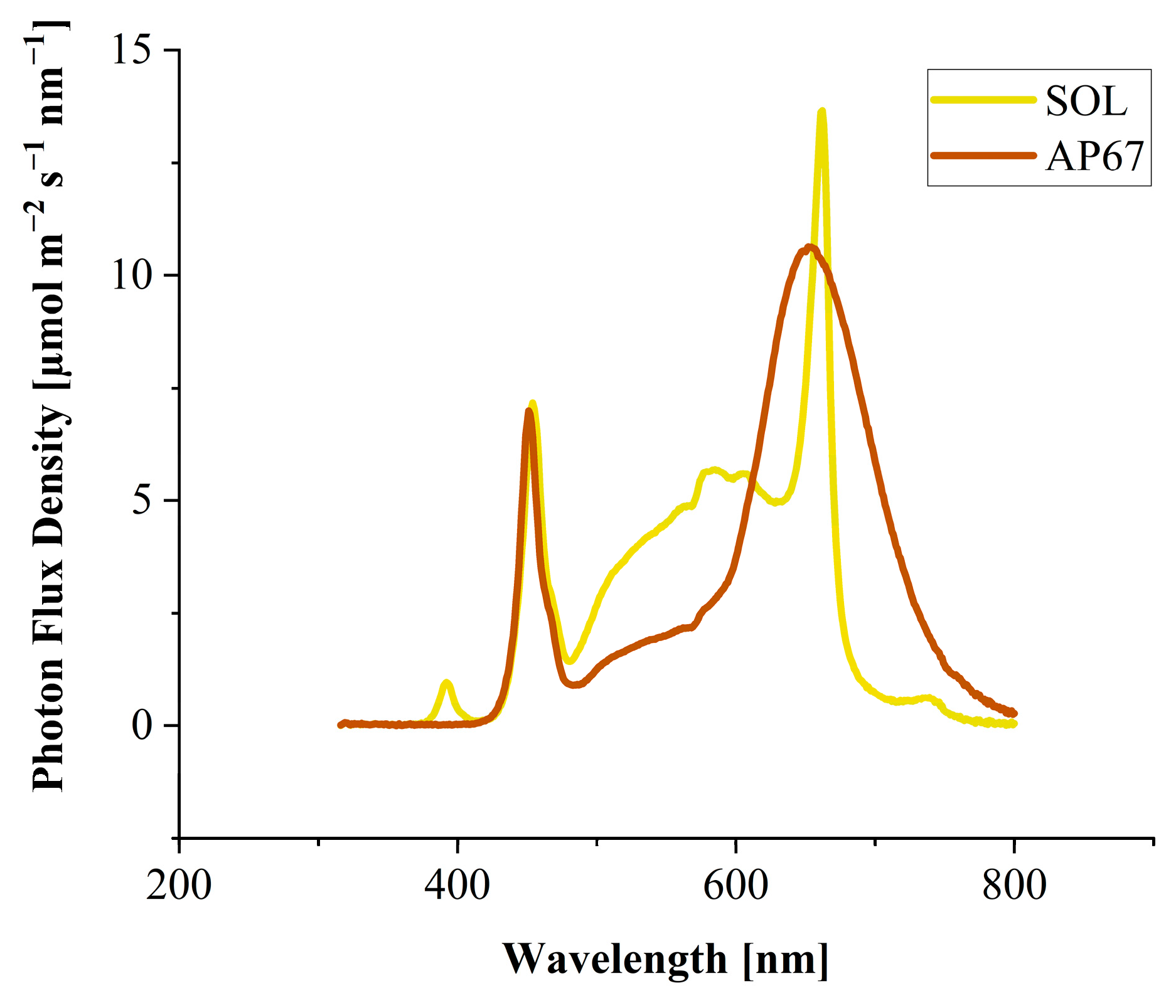

2.2. Light Treatments

2.3. Growing Conditions

2.4. Data Acquisition

2.4.1. Destructive Sampling

2.4.2. Non-Destructive Measurements

2.5. Cannabinoid and Terpene Analysis

2.5.1. Terpene Analysis

2.5.2. Cannabinoid Analysis

2.6. Data Analysis

2.6.1. Photon Conversion Efficacy

2.6.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

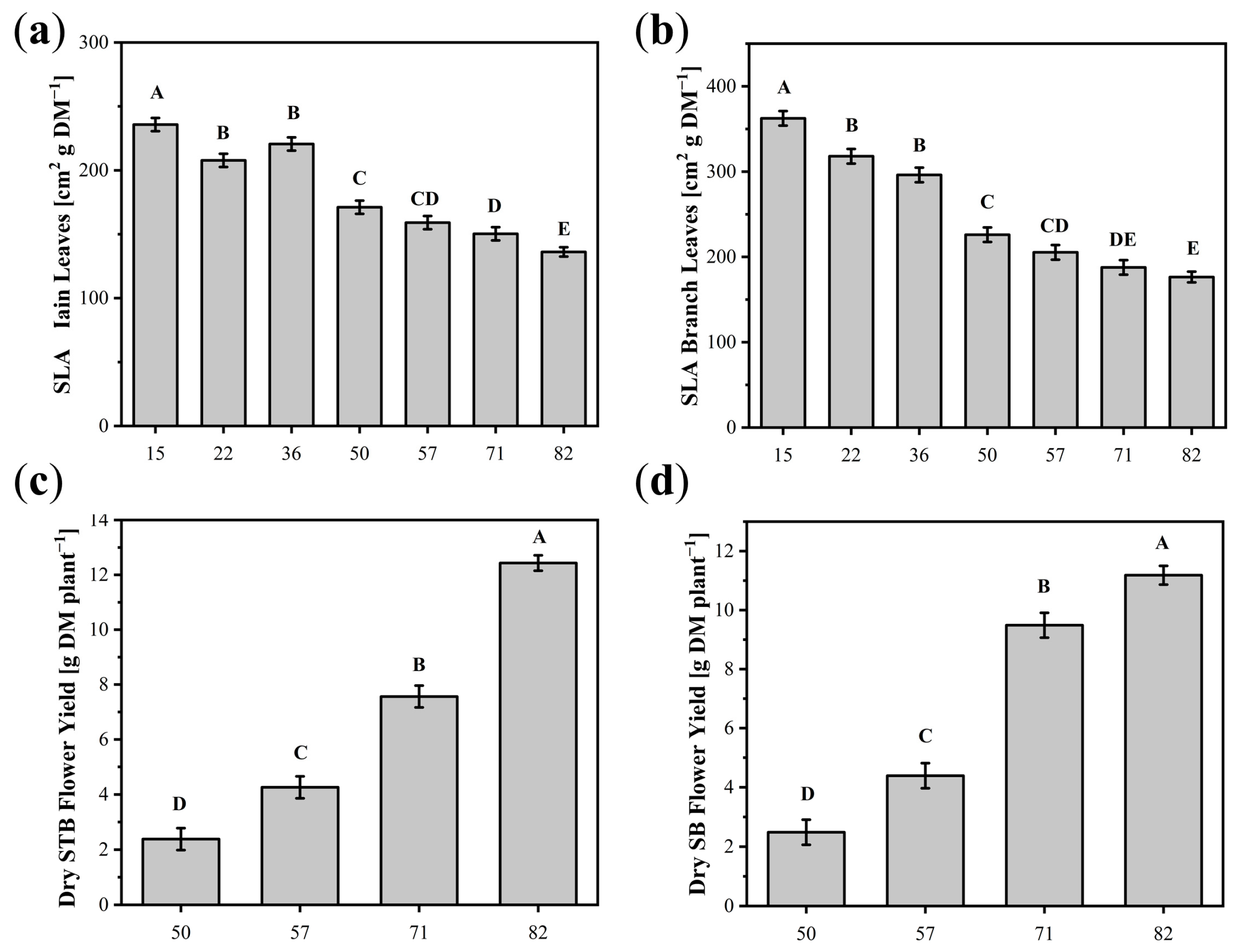

3.1. Morphology and Growth

3.1.1. Influence of DAP

3.1.2. Influence of Light Spectrum

3.2. Plant Density

3.2.1. Dry Flower Yield

3.2.2. CBD and CBDA

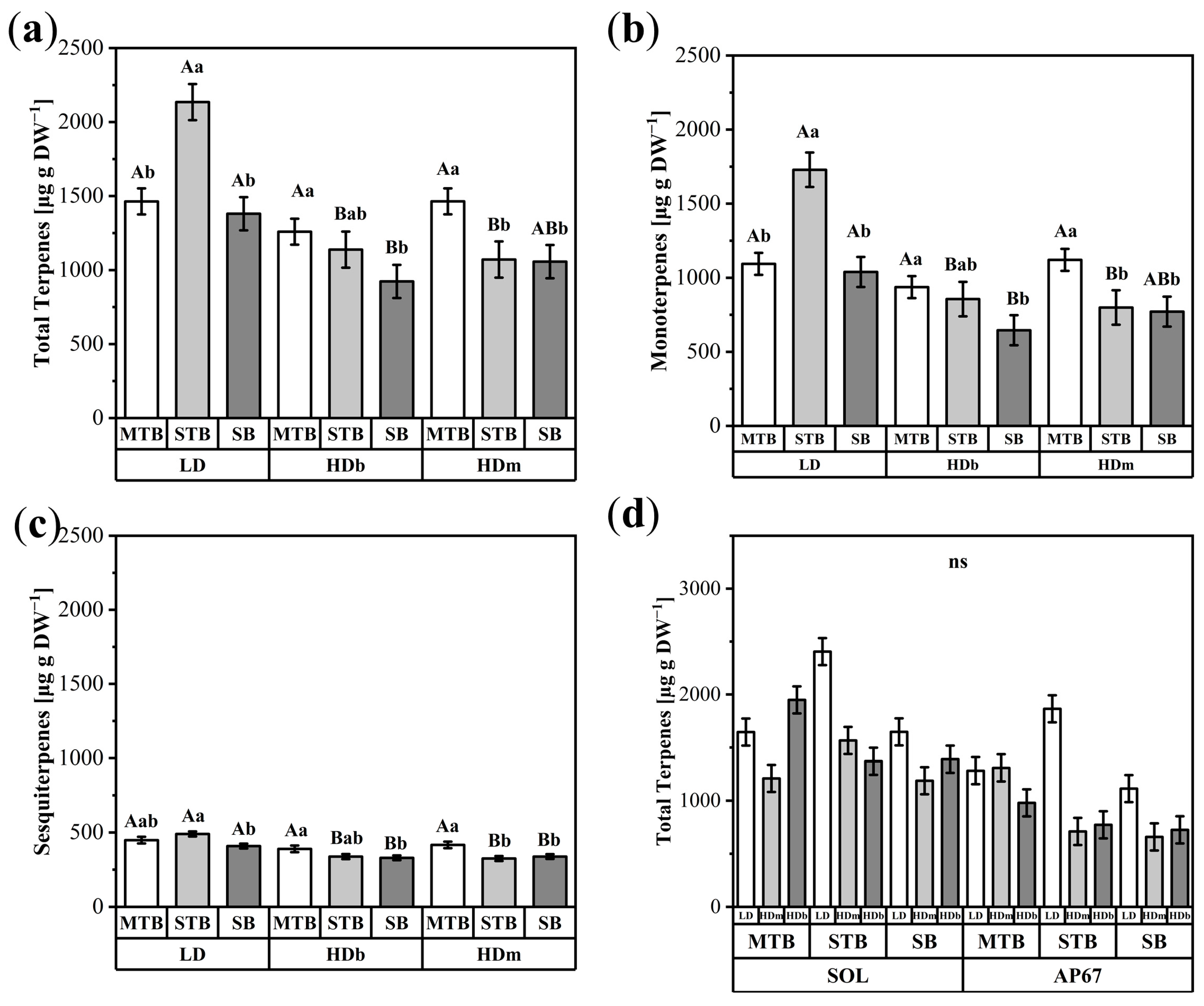

3.2.3. Terpene Flower Position and Density

3.3. Light Distribution in the Square Meter

4. Discussion

4.1. Influence of Light

4.2. Interaction Between Light and Plant Density

4.3. Practical Application

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Eichhorn Bilodeau, S.; Wu, B.-S.; Rufyikiri, A.-S.; MacPherson, S.; Lefsrud, M. An Update on Plant Photobiology and Implications for Cannabis Production. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aliferis, K.A.; Bernard-Perron, D. Cannabinomics: Application of Metabolomics in Cannabis (Cannabis sativa L.) Research and Development. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desaulniers Brousseau, V.; Wu, B.-S.; MacPherson, S.; Morello, V.; Lefsrud, M. Cannabinoids and Terpenes: How Production of Photo-Protectants Can Be Manipulated to Enhance Cannabis sativa L. Phytochemistry. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 620021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danziger, N.; Bernstein, N. Light matters: Effect of light spectra on cannabinoid profile and plant development of medical cannabis (Cannabis sativa L.). Ind. Crop. Prod. 2021, 164, 113351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akvilė, V.; Margit, O.; Pavelas, D. LED Lighting in Horticulture. In Light Emitting Diodes for Agriculture; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 113–147. [Google Scholar]

- Livingston, S.J.; Quilichini, T.D.; Booth, J.K.; Wong, D.C.J.; Rensing, K.H.; Laflamme-Yonkman, J.; Castellarin, S.D.; Bohlmann, J.; Page, J.E.; Samuels, A.L. Cannabis glandular trichomes alter morphology and metabolite content during flower maturation. Plant J. 2020, 101, 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellermeier, M.; Zenk, M.H. Prenylation of olivetolate by a hemp transferase yields cannabigerolic acid, the precursor of tetrahydrocannabinol. FEBS Lett. 1998, 427, 283–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Tholl, D.; Bohlmann, J.; Pichersky, E. The family of terpene synthases in plants: A mid-size family of genes for specialized metabolism that is highly diversified throughout the kingdom. Plant J. 2011, 66, 212–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunanithi, P.S.; Zerbe, P. Terpene Synthases as Metabolic Gatekeepers in the Evolution of Plant Terpenoid Chemical Diversity. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Morrison, V.; Llewellyn, D.; Zheng, Y. Cannabis Yield, Potency, and Leaf Photosynthesis Respond Differently to Increasing Light Levels in an Indoor Environment. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 646020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawoosa, T.; Singh, H.; Kumar, A.; Sharma, S.K.; Devi, K.; Dutt, S.; Vats, S.K.; Sharma, M.; Ahuja, P.S.; Kumar, S. Light and temperature regulated terpene biosynthesis: Hepatoprotective monoterpene picroside accumulation in Picrorhiza kurrooa. Funct. Integr. Genom. 2010, 10, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saloner, A.; Bernstein, N. Nitrogen supply affects cannabinoid and terpenoid profile in medical cannabis (Cannabis sativa L.). Ind. Crop. Prod. 2021, 167, 113516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klepzig, K.D.; Kruger, E.L.; Smalley, E.B.; Raffa, K.F. Effects of biotic and abiotic stress on induced accumulation of terpenes and phenolics in red pines inoculated with bark beetle-vectored fungus. J. Chem. Ecol. 1995, 21, 601–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Fedrizzi, B.; Kilmartin, P.A.; Quek, S.Y. Development of volatile organic compounds and their glycosylated precursors in tamarillo (Solanum betaceum Cav.) during fruit ripening: A prediction of biochemical pathway. Food Chem. 2021, 339, 128046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gershenzon, J. Metabolic costs of terpenoid accumulation in higher plants. J. Chem. Evol. 1994, 20, 1281–1328. Available online: https://docksci.com/metabolic-costs-of-terpenoid-accumulation-in-higher-plants_5cec1aebd64ab23b6f2b7a79.html (accessed on 23 August 2022). [CrossRef]

- Barcaccia, G.; Palumbo, F.; Scariolo, F.; Vannozzi, A.; Borin, M.; Bona, S. Potentials and Challenges of Genomics for Breeding Cannabis Cultivars. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 573299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillig, K.W. Genetic evidence for speciation in Cannabis (Cannabaceae). Genet. Resour. Crop. Evol. 2005, 52, 161–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, E. Evolution and Classification of Cannabis sativa (Marijuana, Hemp) in Relation to Human Utilization. Bot. Rev. 2015, 81, 189–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, P.; Peris, A.; Vergara, K.; Matus, J.T. Comprehending and improving cannabis specialized metabolism in the systems biology era. Plant Sci. 2020, 298, 110571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saloner, A.; Bernstein, N. Nitrogen Source Matters: High NH4/NO3 Ratio Reduces Cannabinoids, Terpenoids, and Yield in Medical Cannabis. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 830224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saloner, A.; Bernstein, N. Response of Medical Cannabis (Cannabis sativa L.) to Nitrogen Supply Under Long Photoperiod. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 572293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danziger, N.; Bernstein, N. Plant architecture manipulation increases cannabinoid standardization in ‘drug-type’ medical cannabis. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2021, 167, 113528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crispim Massuela, D.; Hartung, J.; Munz, S.; Erpenbach, F.; Graeff-Hönninger, S. Impact of Harvest Time and Pruning Technique on Total CBD Concentration and Yield of Medicinal Cannabis. Plants 2022, 11, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morello, V.; Brousseau, V.D.; Wu, N.; Wu, B.-S.; MacPherson, S.; Lefsrud, M. Light Quality Impacts Vertical Growth Rate, Phytochemical Yield and Cannabinoid Production Efficiency in Cannabis sativa. Plants 2022, 11, 2982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casal, J.J. Photoreceptor Signaling Networks in Plant Responses to Shade. Annual Review of Plant Biology. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2013, 64, 403–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reichel, P.; Munz, S.; Hartung, J.; Kotiranta, S.; Graeff-Hönninger, S. Impacts of Different Light Spectra on CBD, CBDA and Terpene Concentrations in Relation to the Flower Positions of Different Cannabis sativa L. Strains. Plants 2022, 11, 2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichel, P.; Munz, S.; Hartung, J.; Präger, A.; Kotiranta, S.; Burgel, L.; Schober, T.; Graeff-Hönninger, S. Impact of Three Different Light Spectra on the Yield, Morphology and Growth Trajectory of Three Different Cannabis sativa L. Strains. Plants 2021, 10, 1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danziger, N.; Bernstein, N. Too Dense or Not Too Dense: Higher Planting Density Reduces Cannabinoid Uniformity but Increases Yield/Area in Drug-Type Medical Cannabis. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 713481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, E.L.; Arce Cubas, L.; Gray, J.E.; Hepworth, C. The influence of stomatal morphology and distribution on photosynthetic gas exchange. Plant J. 2020, 101, 768–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugbee, B. Toward an optimal spectral quality for plant growth and development: The importance of radiation capture. In Proceedings of the ISHS Acta Horticulturae 1134: VIII International Symposium on Light in Horticulture, East Lansing, MI, USA, 22–26 May 2016; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inada, K. Action spectra for photosynthesis in higher plants. Plant Cell Physiol. 1976, 17, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCree, K.J. The action spectrum, absorptance and quantum yield of photosynthesis in crop plants. Agricultural Meteorology. Agric. Meteorol. 1971, 9, 191–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundegårdh, H. Action Spectra and the Role of Carotenoids in Photosynthesis. Physiol. Plant. 1966, 19, 754–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magagnini, G.; Grassi, G.; Kotiranta, S. The Effect of Light Spectrum on the Morphology and Cannabinoid Content of Cannabis sativa L. Med. Cannabis Cannabinoids 2018, 1, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westmoreland, F.M.; Kusuma, P.; Bugbee, B. Cannabis lighting: Decreasing blue photon fraction increases yield but efficacy is more important for cost effective production of cannabinoids. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Namdar, D.; Charuvi, D.; Ajjampura, V.; Mazuz, M.; Ion, A.; Kamara, I.; Koltai, H. LED lighting affects the composition and biological activity of Cannabis sativa secondary metabolites. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2019, 132, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Wang, R.; Liu, X.; Zhou, L.; Dong, M.; Rehman, M.; Fahad, S.; Liu, L.; Deng, G. Effects of Light Spectra on Morphology, Gaseous Exchange, and Antioxidant Capacity of Industrial Hemp. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 937436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llewellyn, D.; Golem, S.; Foley, E.; Dinka, S.; Jones, A.M.P.; Zheng, Y. Indoor grown cannabis yield increased proportionally with light intensity, but ultraviolet radiation did not affect yield or cannabinoid content. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 974018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinomura, T.; Uchida, K.; Furuya, M. Elementary processes of photoperception by phytochrome A for high-irradiance response of hypocotyl elongation in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2000, 122, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casal, J.J. Shade avoidance. Arab. Book 2012, 10, e0157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorente, B.; D’Andrea, L.; Ruiz-Sola, M.A.; Botterweg, E.; Pulido, P.; Andilla, J.; Loza-Alvarez, P.; Rodriguez-Concepcion, M. Tomato fruit carotenoid biosynthesis is adjusted to actual ripening progression by a light-dependent mechanism. Plant J. 2016, 85, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, M.; Tanigawa, Y.; Murakami, T.; Araki, T.; Nagatani, A. PHYTOCHROME-DEPENDENT LATE-FLOWERING accelerates flowering through physical interactions with phytochrome B and CONSTANS. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 18017–18022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leivar, P.; Monte, E. PIFs: Systems integrators in plant development. Plant Cell 2014, 26, 56–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chenge-Espinosa, M.; Cordoba, E.; Romero-Guido, C.; Toledo-Ortiz, G.; León, P. Shedding light on the methylerythritol phosphate (MEP)-pathway: Long hypocotyl 5 (HY5)/phytochrome-interacting factors (PIFs) transcription factors modulating key limiting steps. Plant J. 2018, 96, 828–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Kubota, C. Effects of supplemental light quality on growth and phytochemicals of baby leaf lettuce. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2009, 67, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alokam, S.; Chinnappa, C.C.; Reid, D.M. Red/far-red light mediated stem elongation and anthocyanin accumulation in Stellaria longipes: Differential response of alpine and prairie ecotypes. Can. J. Bot. 2002, 80, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battle, M.W.; Jones, M.A. Cryptochromes integrate green light signals into the circadian system. Plant Cell Environ. 2020, 43, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.L.; McAusland, L.; Murchie, E.H. Don’t ignore the green light: Exploring diverse roles in plant processes. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 68, 2099–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folta, K.M.; Maruhnich, S.A. Green light: A signal to slow down or stop. J. Exp. Bot. 2007, 58, 3099–3111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talbott, L.D.; Hammad, J.W.; Harn, L.C.; Nguyen, V.H.; Patel, J.; Zeiger, E. Reversal by green light of blue light-stimulated stomatal opening in intact, attached leaves of Arabidopsis operates only in the potassium-dependent, morning phase of movement. Plant Cell Physiol. 2006, 47, 332–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talbott, L.D.; Nikolova, G.; Ortiz, A.; Shmayevich, I.; Zeiger, E. Green light reversal of blue-light-stimulated stomatal opening is found in a diversity of plant species. Am. J. Bot. 2002, 89, 366–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frechilla, S.; Talbott, L.D.; Bogomolni, R.A.; Zeiger, E. Reversal of blue light-stimulated stomatal opening by green light. Plant Cell Physiol. 2000, 41, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawley, D.; Graham, T.; Stasiak, M.; Dixon, M. Improving Cannabis Bud Quality and Yield with Subcanopy Lighting. HortScience 2018, 53, 1593–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terashima, I.; Fujita, T.; Inoue, T.; Chow, W.S.; Oguchi, R. Green light drives leaf photosynthesis more efficiently than red light in strong white light: Revisiting the enigmatic question of why leaves are green. Plant Cell Physiol. 2009, 50, 684–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johkan, M.; Shoji, K.; Goto, F.; Hahida, S.; Yoshihara, T. Effect of green light wavelength and intensity on photomorphogenesis and photosynthesis in Lactuca sativa. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2012, 75, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; van Iersel, M.W. Photosynthetic Physiology of Blue, Green, and Red Light: Light Intensity Effects and Underlying Mechanisms. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 619987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brodersen, C.R.; Vogelmann, T.C. Do changes in light direction affect absorption profiles in leaves? Funct. Plant Biol. 2010, 37, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-H.; Goins, G.D.; Wheeler, R.M.; Sager, J.C. Green-light Supplementation for Enhanced Lettuce Growth under Red- and Blue-light-emitting Diodes. HortScience 2004, 39, 1617–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanoue, J.; Little, C.; Hawley, D.; Hao, X. Addition of green light improves fruit weight and dry matter content in sweet pepper due to greater light penetration within the canopy. Sci. Hortic. 2022, 304, 111350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, B.; Lv, X.; Chen, Z.; Xu, K. Supplementing green light under strong sunlight improves growth and functional ingredients of ginger (Zingiber officinale Rosc.) in summer. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2021, 167, 113527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.J.; Ryu, B.R.; Azad, M.O.K.; Rahman, M.H.; Rana, M.S.; Kang, C.-W.; Lim, J.-D.; Lim, Y.-S. Comparative Growth, Photosynthetic Pigments, and Osmolytes Analysis of Hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) Seedlings under an Aeroponics System with Different LED Light Sources. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Fu, Y.; Wang, M. Green light enhances growth, photosynthetic pigments and CO2 assimilation efficiency of lettuce as revealed by ‘knock out’ of the 480–560 nm spectral waveband. Photosynthetica 2017, 55, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandmann, G. Antioxidant Protection from UV- and Light-Stress Related to Carotenoid Structures. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orlando, M.; Trivellini, A.; Incrocci, L.; Ferrante, A.; Mensuali, A. The Inclusion of Green Light in a Red and Blue Light Background Impact the Growth and Functional Quality of Vegetable and Flower Microgreen Species. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backer, R.; Schwinghamer, T.; Rosenbaum, P.; McCarty, V.; Eichhorn Bilodeau, S.; Lyu, D.; Ahmed, M.B.; Robinson, G.; Lefsrud, M.; Wilkins, O.; et al. Closing the Yield Gap for Cannabis: A Meta-Analysis of Factors Determining Cannabis Yield. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sellaro, R.; Crepy, M.; Trupkin, S.A.; Karayekov, E.; Buchovsky, A.S.; Rossi, C.; Casal, J.J. Cryptochrome as a sensor of the blue/green ratio of natural radiation in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2010, 154, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sager, J.C.; Smith, W.O.; Edwards, J.L.; Cyr, K.L. Photosynthetic Efficiency and Phytochrome Photoequilibria Determination Using Spectral Data. Trans. ASAE 1988, 31, 1882–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honnold, R.; Kubas, R.; Macherone, A. Analysis of Terpenes in Cannabis Using the Agilent 7697A/7890B/5977B Headspace GC-MSD System; Agilent Application Notes; Agilent Technologies, Inc.: Santa Clara, CA, USA, 2017; p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, D.; Dai, K.; Xie, Z.; Chen, J. Secondary Metabolites Profiled in Cannabis Inflorescences, Leaves, Stem Barks, and Roots for Medicinal Purposes. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 3309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgel, L.; Hartung, J.; Pflugfelder, A.; Graeff-Hönninger, S. Impact of Growth Stage and Biomass Fractions on Cannabinoid Content and Yield of Different Hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) Genotypes. Agronomy 2020, 10, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piepho, H.P.; Buchse, A.; Emrich, K. A Hitchhiker’s Guide to Mixed Models for Randomized Experiments. J. Agron. Crop. Sci. 2003, 189, 310–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliday, K.; Koornneef, M.; Whitelam, G. Phytochrome B and at Least One Other Phytochrome Mediate the Accelerated Flowering Response of Arabidopsis thaliana L. to Low Red/Far-Red Ratio. Plant Physiol. 1994, 104, 1311–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H. Sensing the light environment: The functions of the phytochrome family. In Photomorphogenesis in Plants, 2nd ed.; Kendrick, R.E., Kronenberg, G.H.M., Eds.; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1998; pp. 377–416. ISBN 978-0-7923-2551-2. [Google Scholar]

- Kotiranta, S.; Pihlava, J.-M.; Kotilainen, T.; Palonen, P. The morphology, inflorescence yield, and secondary metabolite accumulation in hemp type Cannabis sativa can be influenced by the R:FR ratio or the amount of short wavelength radiation in a spectrum. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2024, 208, 117772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libenson, S.; Rodriguez, V.; Pereira, M.L.; Sánchez, R.A.; Casal, J.J. Low Red to Far-Red Ratios Reaching the Stem Reduce Grain Yield in Sunflower. Crop. Sci. 2002, 42, 1180–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, K.; Hu, H.; Chang, M.; Sun, C.; Ullah, A.; Yu, J.; Dong, C.; Gao, Q.; Jiang, D.; Cao, W.; et al. A low red/far-red ratio restricts nitrogen assimilation by inhibiting nitrate reductase associated with downregulated TaNR1.2 and upregulated TaPIL5 in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 206, 107850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongélard, G.; Seemann, M.; Boisson, A.-M.; Rohmer, M.; Bligny, R.; Rivasseau, C. Measurement of carbon flux through the MEP pathway for isoprenoid synthesis by (31)P-NMR spectroscopy after specific inhibition of 2-C-methyl-d-erythritol 2,4-cyclodiphosphate reductase. Effect of light and temperature. Plant Cell Environ. 2011, 34, 1241–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinath, M.; Shailaja, A.; Bindu, B.B.V.; Giri, C.C. Comparative analysis of biomass, ethrel elicitation, light induced differential MVA/MEP pathway gene expression and andrographolide production in adventitious root cultures of Andrographis paniculata (Burm. F.) Nees. Plant Cell Tiss. Organ Cult. 2022, 149, 335–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vranová, E.; Coman, D.; Gruissem, W. Network analysis of the MVA and MEP pathways for isoprenoid synthesis. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2013, 64, 665–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, D.J.; Duncombe, P. The effect of electrical lighting power and irradiance on indoor-grown cannabis potency and yield. J. Forensic Sci. 2012, 57, 618–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holweg, M.M.; Kaiser, E.; Kappers, I.F.; Heuvelink, E.; Marcelis, L.F.M. The role of red and white light in optimizing growth and accumulation of plant specialized metabolites at two light intensities in medical cannabis (Cannabis sativa L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1393803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawley, D. The Influence of Spectral Quality of Light on Plant Secondary Metabolism and Photosynthetic Acclimation to Light Quality. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Guelph, Guelph, ON, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Behnke, K.; Kaiser, A.; Zimmer, I.; Brüggemann, N.; Janz, D.; Polle, A.; Hampp, R.; Hänsch, R.; Popko, J.; Schmitt-Kopplin, P.; et al. RNAi-mediated suppression of isoprene emission in poplar transiently impacts phenolic metabolism under high temperature and high light intensities: A transcriptomic and metabolomic analysis. Plant Mol. Biol. 2010, 74, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhove, W.; van Damme, P.; Meert, N. Factors determining yield and quality of illicit indoor cannabis (Cannabis spp.) production. Forensic Sci. Int. 2011, 212, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- André, A.; Leupin, M.; Kneubühl, M.; Pedan, V.; Chetschik, I. Evolution of the Polyphenol and Terpene Content, Antioxidant Activity and Plant Morphology of Eight Different Fiber-Type Cultivars of Cannabis sativa L. Cultivated at Three Sowing Densities. Plants 2020, 9, 1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

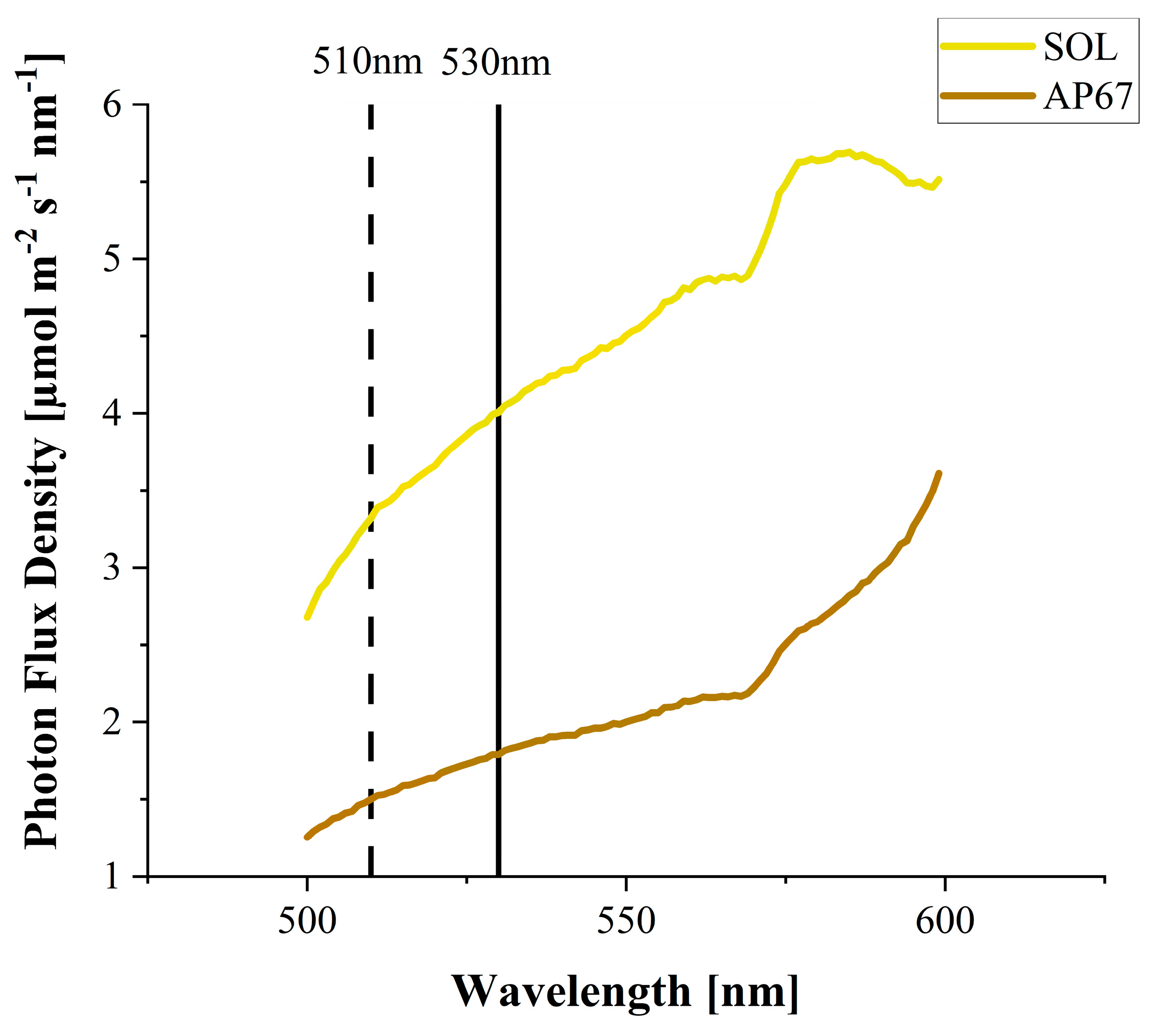

| SOL | AP67 | |

|---|---|---|

| % UV (<400 nm) | 2 | 0 |

| % Blue (400–500 nm) | 17 | 12 |

| % Green (501–600 nm) | 36 | 16 |

| % Red (601–700 nm) | 40 | 57 |

| % Far Red (701–750 nm) | 3 | 15 |

| rYPF (400–700 nm) | 0.88 | 0.87 |

| R:FR ratio (650–670 nm/720–750 nm) | 12.9 | 3.7 |

| B:G ratio | 0.5 | 0.8 |

| B:R ratio | 0.47 | 0.21 |

| N | NO3-N | NH4-N | % NH4 | P | K | Mg | Ca | S | Fe | Zn | Cu | B | Mo | Mn |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 200.0 | 160.4 | 39.6 | 19.82 | 47.0 | 134.1 | 40.0 | 155.5 | 36.5 | 1.50 | 0.054 | 0.215 | 0.108 | 0.054 | 0.269 |

| DAP | 15 | 22 | 36 | 50 | 57 | 71 | 82 (FH) |

| GDD | 237 | 351 | 573 | 799 | 915 | 1146 | 1339 |

| DAP | 9 | 14 | 21 | 28 | 35 | 42 | 49 | 56 | 63 | 78 |

| GDD | 137 | 220 | 335 | 447 | 558 | 670 | 782 | 898 | 1015 | 1267 |

| Factor | CBDA | CBD + CBDA | CBD + CBDA Yield | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [%] | mg m−2 | |||

| Flower position | MTB | 6.80 a | 7.13 a | 2248 c |

| STB | 6.57 a | 6.89 a | 9207 a | |

| SB | 5.61 b | 5.88 b | 7051 b | |

| LD | 6.14 ns | 6.42 b | ||

| Density | HDb | 6.40 ns | 6.71 a | |

| HDm | 6.44 ns | 6.77 a | ||

| Flower position | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.003 | |

| p | Light spectra | 0.354 | 0.090 | 0.828 |

| Density | 0.145 | 0.011 | ||

| position | 0.274 | 0.337 | 0.661 | |

| density | 0.904 | 0.927 | ||

| density | 0.408 | 0.323 | ||

| position | 0.257 | 0.482 | ||

| Factor | Total Terpenes | Monoterpenes | Sesquiterpenes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ug g DW−1 | ||||

| Light spectrum | SOL | 1596 a | 1271 a | 390 ns |

| AP67 | 1045 b | 726 b | 383 ns | |

| p | Flower position | 0.057 | 0.069 | 0.044 |

| Light spectra | 0.004 | 0.009 | 0.693 | |

| Density | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

| position | 0.528 | 0.612 | 0.175 | |

| density | 0.066 | 0.098 | 0.150 | |

| density | 0.011 | 0.019 | 0.005 | |

| position | 0.075 | 0.088 | 0.538 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Reichel, P.; Munz, S.; Hartung, J.; Graeff-Hönninger, S. Harvesting Light: The Interrelation of Spectrum, Plant Density, Secondary Metabolites, and Cannabis sativa L. Yield. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2565. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy14112565

Reichel P, Munz S, Hartung J, Graeff-Hönninger S. Harvesting Light: The Interrelation of Spectrum, Plant Density, Secondary Metabolites, and Cannabis sativa L. Yield. Agronomy. 2024; 14(11):2565. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy14112565

Chicago/Turabian StyleReichel, Philipp, Sebastian Munz, Jens Hartung, and Simone Graeff-Hönninger. 2024. "Harvesting Light: The Interrelation of Spectrum, Plant Density, Secondary Metabolites, and Cannabis sativa L. Yield" Agronomy 14, no. 11: 2565. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy14112565

APA StyleReichel, P., Munz, S., Hartung, J., & Graeff-Hönninger, S. (2024). Harvesting Light: The Interrelation of Spectrum, Plant Density, Secondary Metabolites, and Cannabis sativa L. Yield. Agronomy, 14(11), 2565. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy14112565