Can Comparable Vine and Grape Quality Be Achieved between Organic and Integrated Management in a Warm-Temperate Area?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Site Description and Experimental Design

2.2. Nutrient Concentrations and Organic Matter in Soil

2.3. Extractable Nitrate in Soil

2.4. Nutrients in Vine Leaves

2.5. Vegetative and Yield Parameters

2.6. Must Quality

2.7. Disease Surveys

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Soil Organic Matter and Nutrient Availabity

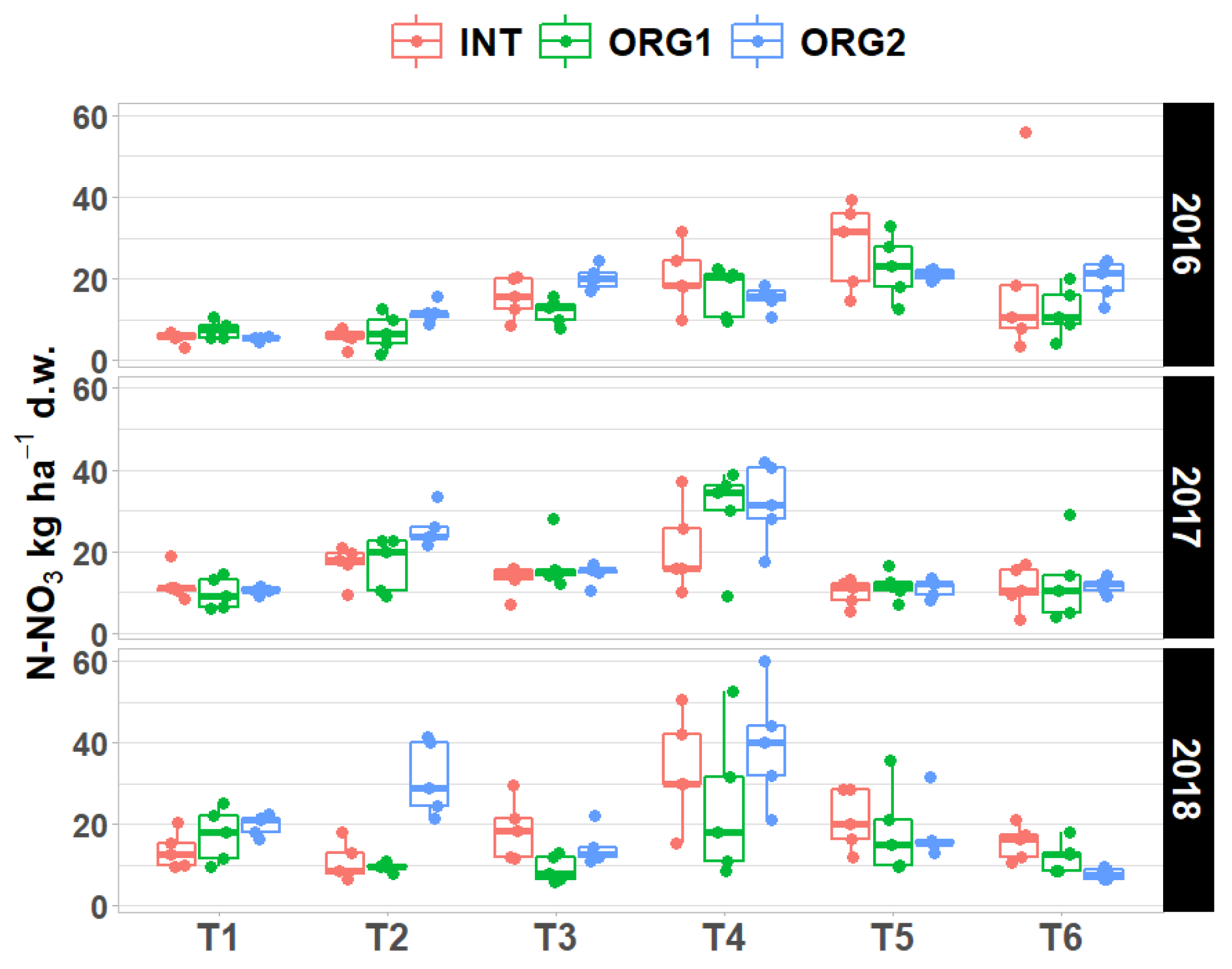

3.2. Dynamics of Mineral Nitrogen in Soil

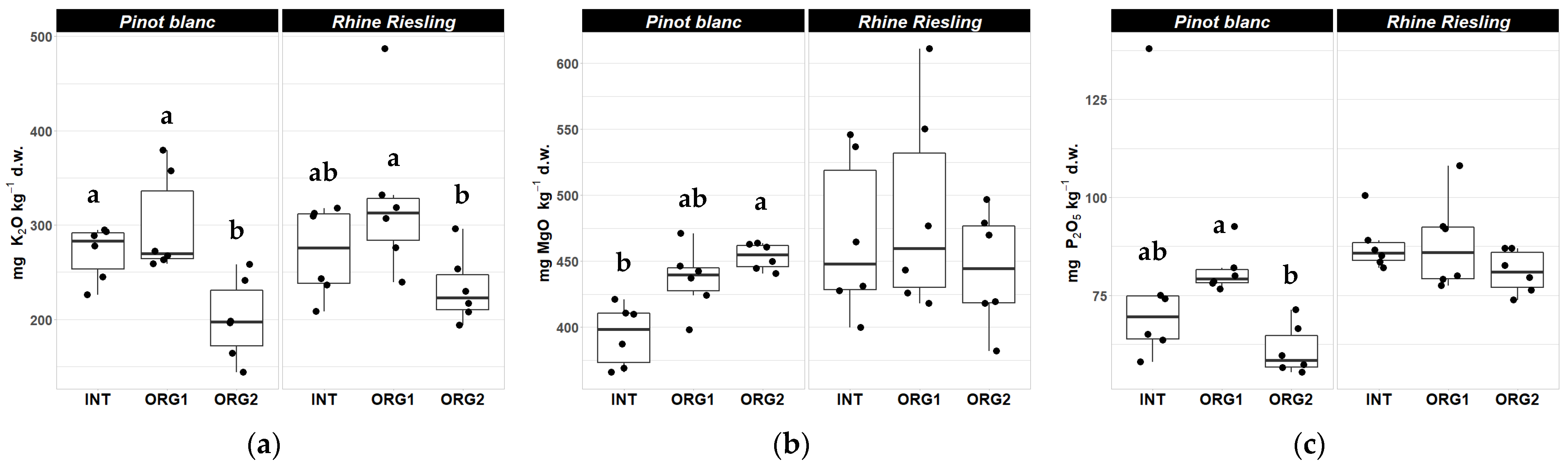

3.3. Nutrients in Leaves

3.4. Vegetative and Yield Variables

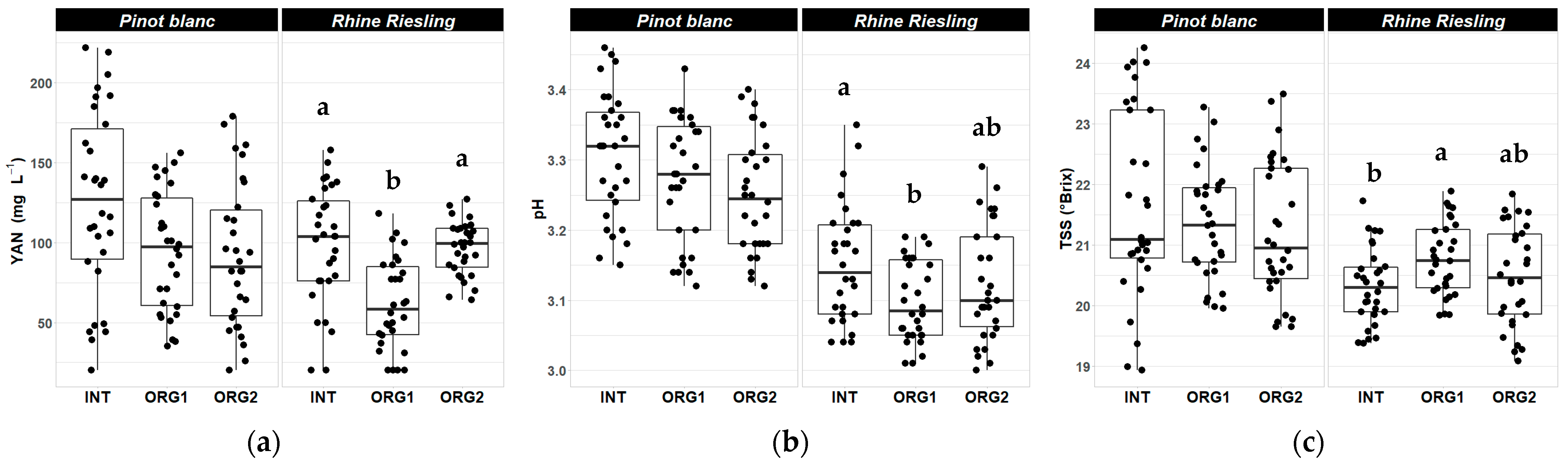

3.5. Must Quality

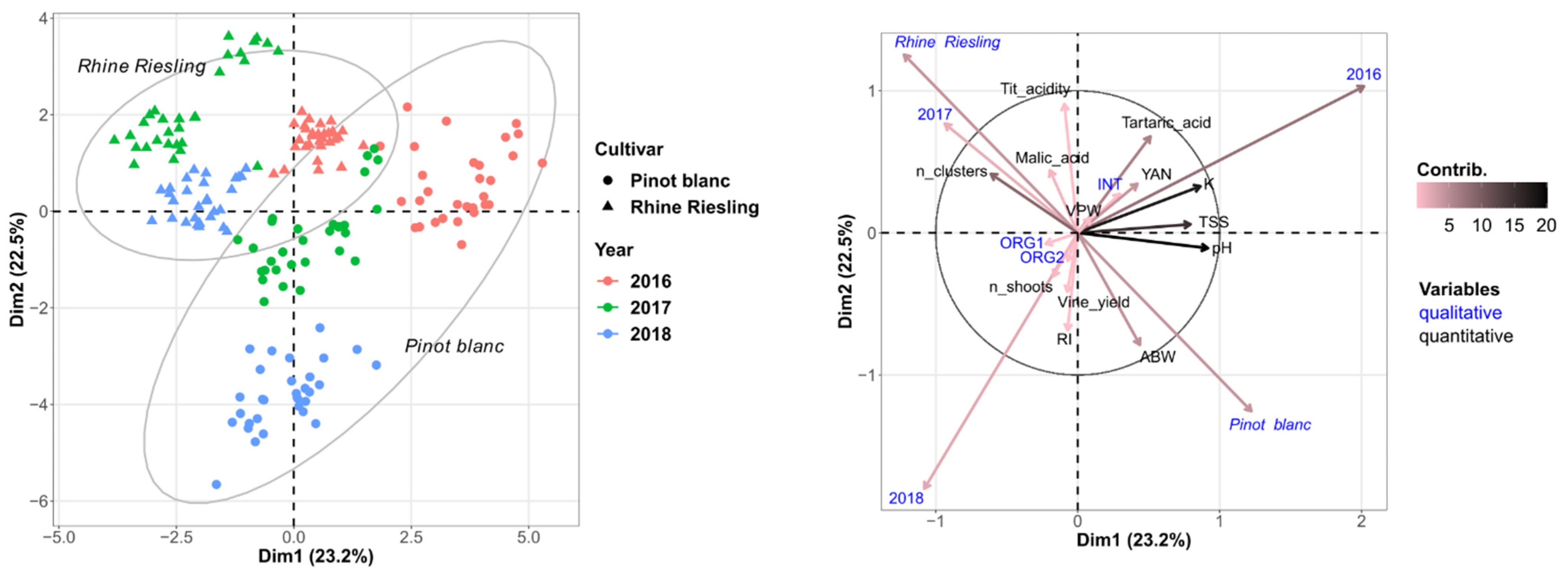

3.6. Multivariate Analysis of Vine and Grape Parameters

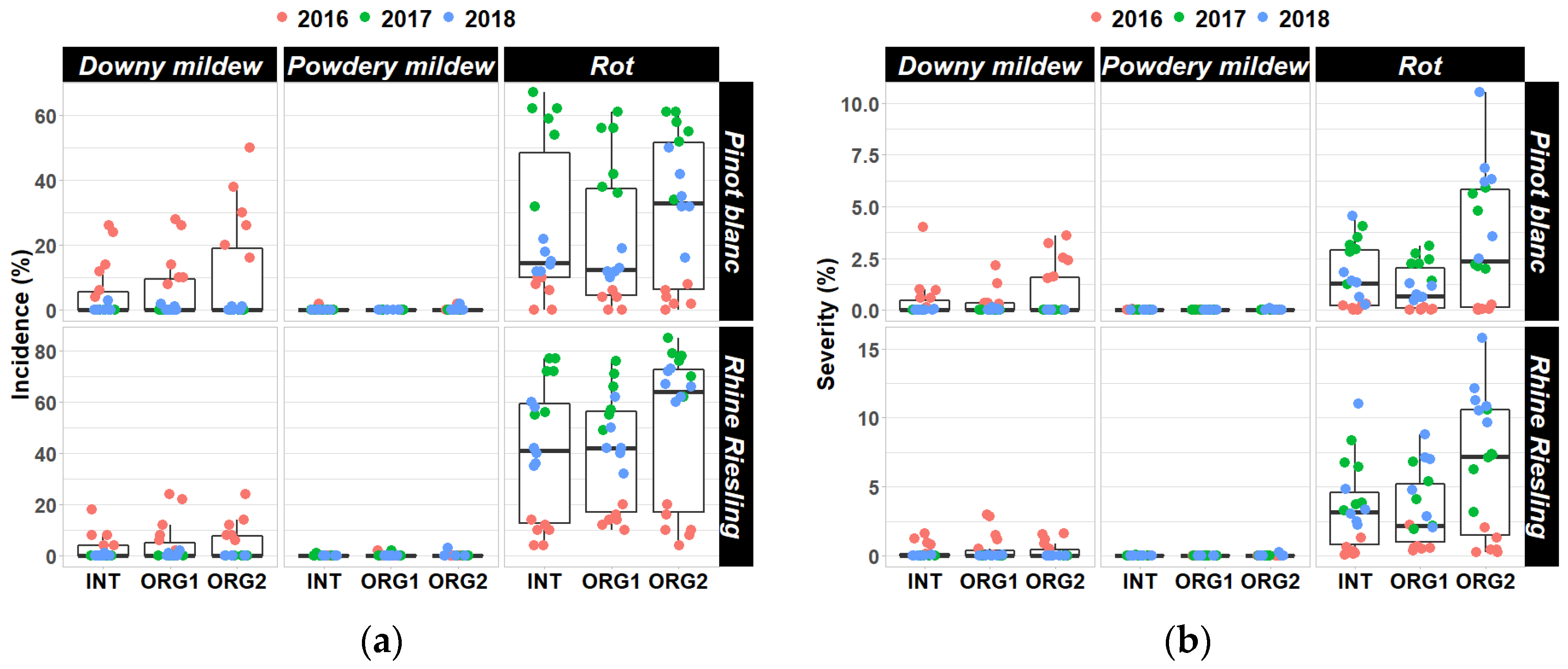

3.7. Disease Surveys

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Willer, H.; Lernoud, J.; Schlatter, B. Organic agriculture worldwide: Current statistics. In The World of Organic Agriculture Statistics and Emerging Trends 2014; FIBL & IFOAM: Frick, Switzerland; Bonn, Germany, 2014; pp. 33–124. [Google Scholar]

- International Organisation of Vine and Wine. State of the World Vitivinicultural Sector in 2020; International Organisation of Vine and Wine: Paris, France, 2021.

- Aubertot, J.N.; Barbier, J.M.; Carpentier, A.; Gril, J.J.; Guichard, L.; Lucas, P.; Savary, S.; Voltz, M.; Savini, I. Pesticides, agriculture et environnement: Réduire l’utilisation des pesticides et en limiter les impacts environnementaux. In INRA/Cemagref Report; Sabbagh, C., de Menthière, N., Eds.; INRAE: Paris, France, 2005; p. 68. [Google Scholar]

- Vos, R.J.; Zabadal, T.J.; Hanson, E.J. Effect of nitrogen application timing on N uptake by Vitis labrusca in a short-season region. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2004, 55, 246–252. [Google Scholar]

- Sachs, J.; Remans, R.; Smukler, S.; Winowiecki, L.; Andelman, S.J.; Cassman, K.G.; Castle, D.; DeFries, R.; Denning, G.; Fanzo, J.; et al. Monitoring the world’s agriculture. Nature 2010, 466, 558–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaller, J.G.; Winter, S.; Strauss, P.; Querner, P. BiodivERsA project VineDivers: Analysing interlinkages between soil biota and biodiversity-based ecosystem services in vineyards across Europe. In Proceedings of the Geophysical Research, EGU General Assembly Conference, Vienna, Austria, 12–17 April 2015; Volume 17, p. 7272. [Google Scholar]

- Reay, D.S.; Davidson, E.A.; Smith, K.A.; Smith, P.; Melillo, J.M.; Dentener, F.; Crutzen, P.J. Global agriculture and nitrous oxide emissions. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2012, 2, 410–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions; The European Green Deal; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Del Bello, D. Il contesto internazionale. In La Filiera Vitivinicola Biologica—Quaderno Tematico 5; Crescenzi, F., Perrone, M., Meo, R., Trinchera, A., Verrastro, V., Giordano, S., Santucci, F.M., Eds.; 2021; pp. 14–17. Available online: https://www.sinab.it/sites/default/files/LA%20FILIERA%20VITIVINICOLA%20BIOLOGICA.pdf (accessed on 27 July 2022).

- Keesstra, S.; Nunes, J.; Novara, A.; Finger, D.; Avelar, D.; Kalantari, Z.; Cerdà, A. The superior effect of nature based solutions in land management for enhancing ecosystem services. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 610–611, 997–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Merot, A.; Smits, N. Does Conversion to Organic Farming Impact Vineyards Yield? A Diachronic Study in Southeastern France. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seufert, V.; Ramankutty, N.; Foley, J.A. Comparing the yields of organic and conventional agriculture. Nature 2021, 485, 229–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo-Opazo, C.; Ortega-Farias, S.; Fuentes, S. Effects of grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) water status on water consumption, vegetative growth and grape quality: An irrigation scheduling application to achieve regulated deficit irrigation. Agric. Water Manag. 2010, 97, 956–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santesteban, L.G.; Miranda, C.; Royo, J.B. Regulated deficit irrigation effects on growth, yield, grape quality and individual anthocyanin composition in Vitis vinifera L. cv. ‘Tempranillo’. Agric. Water Manag. 2011, 98, 1171–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raupp, J. Manure fertilization for soil organic matter maintenance and its effects upon crops and the environment, evaluated in a long-term trial. In Sustainable Management of Soil Organic Matter; Rees, R.M., Ball, B.C., Campbell, C.D., Watson, C.A., Eds.; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2001; pp. 301–308. [Google Scholar]

- Ndambi, O.A.; Pelster, D.E.; Owino, J.O.; de Buisonjé, F.; Vellinga, T. Manure Management Practices and Policies in Sub-Saharan Africa: Implications on Manure Quality as a Fertilizer. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2019, 3, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Raupp, J.; Oltmanns, M. Soil properties, crop yield and quality with farmyard manure with and without biodynamic preparations and with inorganic fertilizers. In Long-Term Field Experiments in Organic Farming; Raupp, J., Pekrun, C., Oltmanns, M., Köpke, U., Eds.; ISOFAR Scientific Series; Verlag Dr. Köster: Berlin, Germany, 2006; pp. 135–155. [Google Scholar]

- Rotaru, L.; Stoleru, V.; Mustea, M. Fertilization with green manure on Chasselas Dore grape vine as an alternative for sustainable viticulture. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2011, 9, 236–243. [Google Scholar]

- Ingels, C.A.; Scow, K.M.; Whisson, D.A.; Drenovsky, R.E. Effects of cover crops on grapevines, yield, juice composition, soil microbial ecology, and gopher activity. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2005, 56, 19–29. [Google Scholar]

- Pou, A.; Gulías, J.; Moreno, M.; Tomàs, M.; Medrano, H.; Cifre, J. Cover cropping in Vitis vinifera L. cv. Manto Negro vineyards under Mediterranean conditions: Effects on plant vigour, yield and grape quality. OENO One 2011, 45, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pisciotta, A.; Di Lorenzo, R.; Novara, A.; Laudicina, V.A.; Barone, E.; Santoro, A.; Gristina, L.; Barbagallo, M.G. Cover crop and pruning residue management to reduce nitrogen mineral fertilization in mediterranean vineyards. Agronomy 2021, 11, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irvin, N.A.; Pinckard, T.R.; Perring, T.M.; Hoddle, M.S. Evaluating the potential of buckwheat and cahaba vetch as nectar producing cover crops for enhancing biological control of Homalodisca vitripennis in California vineyards. Biol. Control 2014, 76, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendgen, M.; Döring, J.; Stöhrer, V.; Schulze, F.; Lehnart, R.; Kauer, R. Spatial Differentiation of Physical and Chemical Soil Parameters under Integrated, Organic, and Biodynamic Viticulture. Plants 2020, 9, 1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abad, J.; de Mendoza, I.H.; Marín, D.; Orcaray, L.; Santesteban, L.G. Cover crops in viticulture. A systematic review (1): Implications on soil characteristics and biodiversity in vineyard. OENO One 2021, 1, 295–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, J.; Athmann, M.; Meissner, G.; Kauer, R.; Geier, U.; Bornhütter, R.; Schultz, H. Quality assessment of grape juice from integrated, organic and biodynamic viticulture using image forming methods. OENO One 2020, 54, 373–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meissner, G.; Athmann, M.E.; Fritz, J.; Kauer, R.; Stoll, M.; Schultz, H.R. Conversion to organic and biodynamic viticultural practices: Impact on soil, grapevine development and grape quality. OENO One 2019, 4, 639–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gattullo, C.E.; Mezzapesa, G.N.; Stellacci, A.M.; Ferrara, G.; Occhiogrosso, G.; Petrelli, G.; Castellini, M.; Spagnuolo, M. Cover Crop for a Sustainable Viticulture: Effects on Soil Properties and Table Grape Production. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, D.H.; Eichhorn, K.W.; Bleiholder, H.; Klose, R.; Meier, U.; Weber, E. Phänologische Entwicklungsstadien der Weinrebe (Vitis vinifera L. ssp. vinifera). Vitic. Enol. Sci. 1994, 49, 66–70. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation Internationale de la Vigne et du Vin. Compendium of International Methods of Analysis; OIV: Paris, France, 2021.

- Giandon, P.; Bortolami, P. L’interpretazione Delle Analisi del Terreno. Strumento per la Sostenibilità Ambiental; Carta, M., Ed.; ARPAV: Padova, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Barbafieri, M.; Lubrano, L.; Petruzzelli, G. Characterization of heavy metal pollution in soil. Ann. Chim. 1996, 86, 635–652. [Google Scholar]

- Morlat, R.; Chaussod, R. Long-term additions of organic amendments in a Loire valley vineyard. I. Effects on properties of a calcareous sandy soil. AJEV 2008, 59, 353–363. [Google Scholar]

- Porro, D.; Dorigatti, C.; Zatelli, A.; Ramponi, M.; Stefanini, M.; Policarpo, M. Partitioning of dry matter in grapevines during a season: Estimation of nutrient requirements. Progrès Agric. Vitic. 2009, 126, 184–188. [Google Scholar]

- Hodges, S.C. Soil Fertility Basics. In Soil Science Extension; North Carolina State University: Raleigh, NC, USA, 2010; pp. 1–75. [Google Scholar]

- Ripoche, A.; Metay, A.; Celette, F.; Gary, C. Changing the soil surface management in vineyards: Immediate and delayed effects on the growth and yield of grapevine. Plant Soil 2011, 339, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, J.; Müller, C.; Cai, Z. Temperature sensitivity of gross N transformation rates in an alpine meadow on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. J. Soils Sediments 2017, 17, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zheng, Q.; Noll, L.; Hu, Y.; Wanek, W. Environmental effects on soil microbial nitrogen use efficiency are controlled by allocation of organic nitrogen to microbial growth and regulate gross N mineralization. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2019, 135, 304–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peoples, M.B.; Brockwell, J.; Herridge, D.F.; Rochester, I.J.; Alves, B.J.R.; Urquiaga, S.; Boddey, R.M.; Dakora, F.D.; Bhattarai, S.; Maskey, S.L.; et al. The contributions of nitrogen-fixing crop legumes to the productivity of agricultural systems. Symbiosis 2009, 48, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Álvarez, E.P.; Garde-Cerdán, T.; Santamaría, P.; García-Escudero, E.; Peregrina, F. Influence of two different cover crops on soil N availability, N nutritional status, and grape yeast-assimilable N (YAN) in a cv. Tempranillo vineyard. Plant Soil 2015, 390, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löhnertz, O. Untersuchungen zum Zeitlichen Verlauf der Nährstoffaufnahme bei Vitis Vinifera cv Riesling; Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Forschungsanstalt Geisenheim: Geisenheim, Germany, 1988; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Conradie, W.J. Seasonal Uptake of Nutrients by Chenin blanc in Sand Culture: I. Nitrogen. S. Afr. J. Enol. Vitic. 1980, 1, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzapfel, B.P. Seasonal vine nutrient dynamics and distribution of Shiraz grapevines. OENO One 2019, 53, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zapata, C.; Deléens, E.; Chaillou, S.; Magné, C. Partitioning and mobilization of starch and N reserves in grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.). J. Plant Physiol. 2004, 161, 1031–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morelli, R.; Bertoldi, D.; Baldantoni, D.; Zanzotti, R. Labile, recalcitrant and stable soil organic carbon: Comparison of agronomic management in a vineyard of Trentino (Italy). BIO Web Conf. 2022, 44, 02007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porro, D.; Stringari, G.; Failla, O.; Scienza, A. Thirteen years of leaf analysis applied to italian viticulture, olive and fruit growing. Acta Hortic. 2001, 564, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döring, J.; Collins, C.; Frisch, M.; Kauer, R. Organic and biodynamic viticulture affect biodiversity and vine and wine properties: A systematic quantitative review. AJEV 2019, 70, 221–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evers, D.; Molitor, D.; Rothmeier, M.; Behr, M.; Fischer, S.; Hoffmann, L. Efficiency of different strategies for the control of grey mold on grapes including gibberellic acid (Gibb3), leaf removal and/or botrycide treatments. J. Int. Sci. Vigne Vin 2010, 44, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smart, R.E. Sunlight into Wine; Winetitles: Adelaide, Australia, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, S.-J.; Henschke, P.A. Implications of nitrogen nutrition for grapes, fermentation and wine. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2005, 11, 242–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habran, A.; Commisso, M.; Helwi, P.; Hilbert, G.; Negri, S.; Ollat, N.; Gomès, E.; van Leeuwen, C.; Guzzo, F.; Delrot, S. Roostocks/Scion/Nitrogen Interactions Affect Secondary Metabolism in the Grape Berry. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hannam, K.D.; Neilsen, G.H.; Neilsen, D.; Midwood, A.J.; Millard, P.; Zhang, Z.; Thornton, B.; Steinke, D. Amino Acid Composition of Grape (Vitis vinifera L.) Juice in Response to Applications of Urea to the Soil or Foliage. AJEV 2015, 67, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garde-Cerdán, T.; Lorenzo, C.; Lara, J.F.; Pardo, F.; Ancín-Azpilicueta, C.; Salinas, M.R. Study of the Evolution of Nitrogen Compounds during Grape Ripening. Application to Differentiate Grape Varieties and Cultivated Systems. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 2410–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribereau-Gayon, J.; Peynaud, E. Trattato di Enologia Vol. I. Maturazione dell’uva Fermentazione Alcoolica Vinificazione; Edagricole: Bologna, Italia, 1971; p. 131. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, J.A.; Fraga, H.; Malheiro, A.C.; Moutinho-Pereira, J.; Dinis, L.-T.; Correia, C.; Moriondo, M.; Leolini, L.; DiBari, C.; Costafreda-Aumedes, S.; et al. A Review of the Potential Climate Change Impacts and Adaptation Options for European Viticulture. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mania, E.; Petrella, F.; Giovannozzi, M.; Piazzi, M.; Wilson, A.; Guidoni, S. Managing Vineyard Topography and Seasonal Variability to Improve Grape Quality and Vineyard Sustainability. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Soil Physical and Chemical Parameters | Pinot Blanc | Rhine Riesling |

|---|---|---|

| Sand (g kg−1 d.w.) | 440 ± 43 | 463 ± 18 |

| Silt (g kg−1 d.w.) | 456 ± 32 | 438 ± 26 |

| Clay (g kg−1 d.w.) | 104 ± 19 | 99 ± 12 |

| pH | 7.9 ± 0.1 | 7.8 ± 0.1 |

| Total carbonates (g CaCO3 kg−1 d.w.) | 408 ± 49 | 545 ± 1 |

| Active carbonates (g CaCO3 kg−1 d.w.) | 11 ± 2 | 11 ± 1 |

| SOM (g kg−1 d.w.) | 32 ± 5 | 38 ± 6 |

| Total N (g kg−1 d.w.) | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 1.7 ± 0.3 |

| C/N | 13 ± 1 | 13 ± 1 |

| CEC (cmol+ kg−1 d.w.) | 13 ± 2 | 14 ± 2 |

| Agronomic Practices | INT | ORG1 | ORG2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical weed control (row) | x | ||

| Mechanical weed control (row) | x | x | |

| Mechanical weed control (inter-row) | x | x | x |

| Mineral fertilization (NPK 12:12:17) | x | ||

| Organic manure (every two years) | x | ||

| Green manure (alternate inter-row) | x | ||

| Biodynamic preparations (500 and 501) | x | ||

| Synthetic pesticides | x | ||

| Pesticides allowed in organic farming | x | x | x |

| Pneumatic leaf removing at flowering | x | x | |

| Manual sprouts removal | x | ||

| Mechanical topping | x | ||

| Shoot rolling | x | x | |

| Chemical bunch thinning | x | ||

| Mating disruption technique (Lobesia botrana + Eupoecilia ambiguella) | x | x | x |

| Timing | Month | BBCH Scale | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | ||

| T1 | May | 16–17 6–7 leaves unfolded | 53 Inflorescences clearly visible | 16–17 6–7 leaves unfolded |

| T2 | June | 69 End of flowering | 72 Fruit set: young fruits begin to swell | 73 Berries groat-sized, bunches begin to hang |

| T3 | July | 77 Berries beginning to touch | 79 Majority of berries touching | 79 Majority of berries touching |

| T4 | August | 83 Berries developing color | 83 Berries developing color | 83 Berries developing color |

| T5 | September | 89 Berries ripe for harvest | 89 Berries ripe for harvest | 89 Berries ripe for harvest |

| T6 | October | 93 Beginning of leaf-fall | 93 Beginning of leaf-fall | 95 50% of leaves fallen |

| Cultivar | Variable | Thesis | Median | Min–Max | Q1–Q3 | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pinot blanc | N (%) | INT | 2.36 | 2.15–2.58 | 2.29–2.45 | n.s. |

| ORG1 | 2.24 | 2.08–2.56 | 2.22–2.27 | |||

| ORG2 | 2.21 | 2.13–2.45 | 2.14–2.29 | |||

| P (%) | INT | 0.21 | 0.17–0.23 | 0.19–0.23 | n.s. | |

| ORG1 | 0.20 | 0.16–0.26 | 0.17–0.24 | |||

| ORG2 | 0.18 | 0.17–0.18 | 0.17–0.18 | |||

| K (%) | INT | 1.25 | 0.92–1.54 | 1.00–1.33 | n.s. | |

| ORG1 | 1.02 | 0.83–1.29 | 0.93–1.09 | |||

| ORG2 | 1.00 | 0.72–1.19 | 0.75–1.01 | |||

| Ca (%) | INT | 3.17 | 2.63–3.87 | 2.93–3.48 | n.s. | |

| ORG1 | 3.19 | 2.86–3.86 | 3.07–3.77 | |||

| ORG2 | 3.3 | 2.92–4.07 | 2.92–3.72 | |||

| Mg (%) | INT | 0.35 | 0.28–0.40 | 0.32–0.38 | n.s. | |

| ORG1 | 0.35 | 0.30–0.41 | 0.33–0.40 | |||

| ORG2 | 0.35 | 0.29–0.44 | 0.32–0.38 | |||

| B (mg kg−1) | INT | 28 | 25–33 | 25–30 | n.s. | |

| ORG1 | 30 | 25–36 | 26–33 | |||

| ORG2 | 30 | 26–36 | 28–33 | |||

| Fe (mg kg−1) | INT | 71 | 63–81 | 64–77 | n.s. | |

| ORG1 | 69 | 63–75 | 64–72 | |||

| ORG2 | 77 | 68–78 | 72–78 | |||

| Mn (mg kg−1) | INT | 73 | 52–110 | 53–107 | n.s. | |

| ORG1 | 74 | 41–84 | 60–81 | |||

| ORG2 | 58 | 41–68 | 52–68 | |||

| Zn (mg kg−1) | INT | 16 | 13–20 | 13–17 | n.s. | |

| ORG1 | 17 | 15–22 | 16–18 | |||

| ORG2 | 15 | 12–21 | 13–19 | |||

| Rhine Riesling | N (%) | INT | 2.14 | 2.09–2.30 | 2.13–2.17 | n.s. |

| ORG1 | 2.06 | 1.92–2.19 | 1.97–2.11 | |||

| ORG2 | 2.12 | 2.01–2.23 | 2.03–2.20 | |||

| P (%) | INT | 0.17 | 0.14–0.18 | 0.15–0.18 | ab | |

| ORG1 | 0.18 | 0.16–0.19 | 0.16–0.18 | a | ||

| ORG2 | 0.15 | 0.13–0.15 | 0.14–0.15 | b | ||

| K (%) | INT | 1.28 | 0.95–1.47 | 0.97–1.37 | n.s. | |

| ORG1 | 1.08 | 0.97–1.42 | 1.00–1.23 | |||

| ORG2 | 0.95 | 0.83–1.22 | 0.86–1.13 | |||

| Ca (%) | INT | 2.78 | 2.41–3.33 | 2.57–3.32 | n.s. | |

| ORG1 | 2.76 | 2.56–3.35 | 2.63–3.18 | |||

| ORG2 | 2.97 | 2.49–3.75 | 2.66–3.73 | |||

| Mg (%) | INT | 0.41 | 0.31–0.48 | 0.37–0.47 | a | |

| ORG1 | 0.31 | 0.28–0.37 | 0.30–0.34 | b | ||

| ORG2 | 0.36 | 0.28–0.40 | 0.32–0.38 | ab | ||

| B (mg kg−1) | INT | 34 | 27–39 | 29–38 | n.s. | |

| ORG1 | 36 | 34–39 | 34–38 | |||

| ORG2 | 34 | 31–36 | 32–34 | |||

| Fe (mg kg−1) | INT | 69 | 61–73 | 62–72 | n.s. | |

| ORG1 | 63 | 59–71 | 61–65 | |||

| ORG2 | 66 | 61–77 | 64–67 | |||

| Mn (mg kg−1) | INT | 102 | 71–126 | 92–116 | n.s. | |

| ORG1 | 100 | 67–116 | 85–101 | |||

| ORG2 | 106 | 78–115 | 81–112 | |||

| Zn (mg kg−1) | INT | 20 | 19–26 | 19–23 | n.s. | |

| ORG1 | 21 | 16–25 | 18–25 | |||

| ORG2 | 23 | 20–30 | 20–28 |

| Cultivar | Variable | Thesis | Median | Min–Max | Q1–Q3 | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pinot blanc | n_shoots | INT | 13 | 6–31 | 11–16 | a ab b |

| ORG1 | 12 | 6–21 | 10–15 | |||

| ORG2 | 11 | 5–21 | 9–13 | |||

| n_clusters | INT | 15 | 4–31 | 12–19 | n.s. | |

| ORG1 | 14 | 5–32 | 12–18 | |||

| ORG2 | 14 | 4–31 | 11–18 | |||

| ABW (g) | INT | 153 | 89–263 | 134–175 | n.s. | |

| ORG1 | 167 | 66–288 | 138–194 | |||

| ORG2 | 170 | 30–357 | 146–197 | |||

| Vine_yield (kg) | INT | 2.28 | 0.55–5.66 | 1.72–2.95 | n.s. | |

| ORG1 | 2.47 | 0.64–5.40 | 1.75–3.01 | |||

| ORG2 | 2.39 | 0.24–5.63 | 1.82–3.01 | |||

| VPW (kg) | INT | 0.32 | 0.05–1.03 | 0.18–0.48 | n.s. | |

| ORG1 | 0.39 | 0.09–1.50 | 0.28–0.53 | |||

| ORG2 | 0.33 | 0.09–1.15 | 0.23–0.46 | |||

| RI | INT | 7.6 | 0.9–24.5 | 4.2–12.0 | n.s. | |

| ORG1 | 6.5 | 1.1–18.6 | 4.4–8.4 | |||

| ORG2 | 7.1 | 0.8–22.3 | 5.1–9.8 | |||

| Rhine Riesling | n_shoots | INT | 12 | 5–20 | 10–14 | a ab b |

| ORG1 | 11 | 4–18 | 9–13 | |||

| ORG2 | 10 | 6–15 | 8–12 | |||

| n_clusters | INT | 21 | 8–42 | 17–25 | n.s. | |

| ORG1 | 22 | 5–40 | 18–26 | |||

| ORG2 | 21 | 9–37 | 16–24 | |||

| ABW (g) | INT | 102 | 52–193 | 85–119 | n.s. | |

| ORG1 | 104 | 56–215 | 86–126 | |||

| ORG2 | 112 | 61–219 | 97–129 | |||

| Vine_yield (kg) | INT | 2.06 | 0.67–4.10 | 1.70–2.51 | n.s. | |

| ORG1 | 2.16 | 0.49–4.43 | 1.67–2.95 | |||

| ORG2 | 2.24 | 0.96–4.20 | 1.80–2.76 | |||

| VPW (kg) | INT | 0.39 | 0.10–1.08 | 0.28–0.51 | n.s. | |

| ORG1 | 0.39 | 0.12–1.48 | 0.30–0.49 | |||

| ORG2 | 0.39 | 0.08–0.85 | 0.30–0.52 | |||

| RI | INT | 6.2 | 0.9–18.4 | 3.9–8.0 | n.s. | |

| ORG1 | 6.0 | 1.6–15.9 | 4.7–7.4 | |||

| ORG2 | 5.8 | 2.3–18.8 | 4.4–7.6 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Morelli, R.; Roman, T.; Bertoldi, D.; Zanzotti, R. Can Comparable Vine and Grape Quality Be Achieved between Organic and Integrated Management in a Warm-Temperate Area? Agronomy 2022, 12, 1789. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy12081789

Morelli R, Roman T, Bertoldi D, Zanzotti R. Can Comparable Vine and Grape Quality Be Achieved between Organic and Integrated Management in a Warm-Temperate Area? Agronomy. 2022; 12(8):1789. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy12081789

Chicago/Turabian StyleMorelli, Raffaella, Tomas Roman, Daniela Bertoldi, and Roberto Zanzotti. 2022. "Can Comparable Vine and Grape Quality Be Achieved between Organic and Integrated Management in a Warm-Temperate Area?" Agronomy 12, no. 8: 1789. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy12081789

APA StyleMorelli, R., Roman, T., Bertoldi, D., & Zanzotti, R. (2022). Can Comparable Vine and Grape Quality Be Achieved between Organic and Integrated Management in a Warm-Temperate Area? Agronomy, 12(8), 1789. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy12081789