A Self-Reliant Tea Economy Offering Inclusive Growth: A Case of Tripureswari Tea, India

Abstract

:1. Introduction: Growth Trajectory of the Tea Industry in Tripura

2. Materials and Methods

- Brand Identity

- Distribution Logistics

- Demand Fulfillment

- Selling Activities

- Convergence with other development sectors

3. Results

3.1. Status of Tea Industry in Tripura

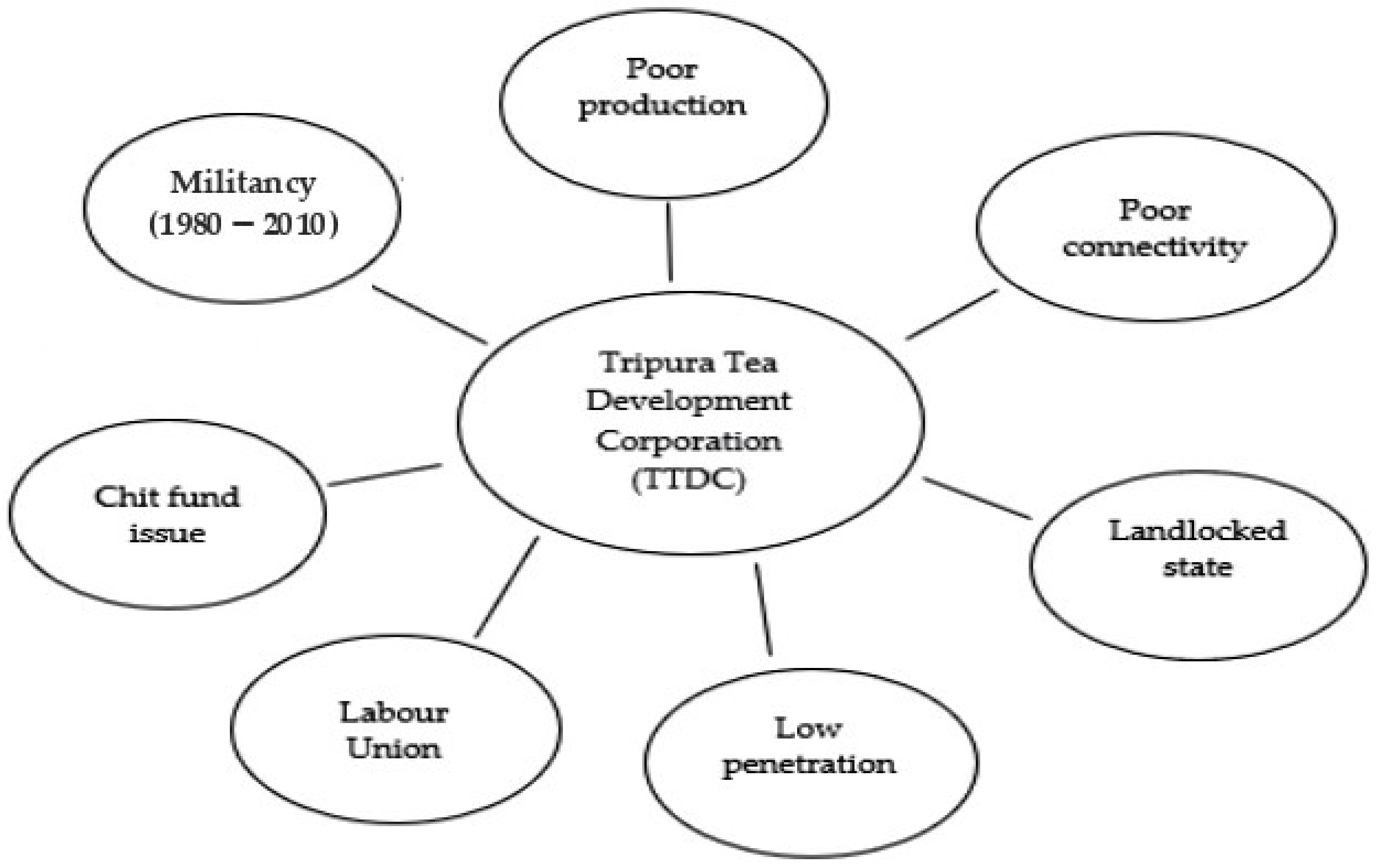

3.2. Tripura Tea Industry in Flux: The Pertinent Problem

3.2.1. The System Dynamics

- Natural and Environmental Risk

- Climate Change

- b.

- Extreme Rainfall Patterns

- 2

- Market Risks

- Lack of Auction Center

- b.

- Law, Policy and Regulation

- c.

- Community Development

3.2.2. The Economics of Production

3.3. The Turnaround Strategy

3.3.1. Brand Identification for Tripura Tea

3.3.2. Distribution Strategy and Demand Fulfillment

3.3.3. Selling Activities

3.3.4. Tea in Convergence with MGNREGS

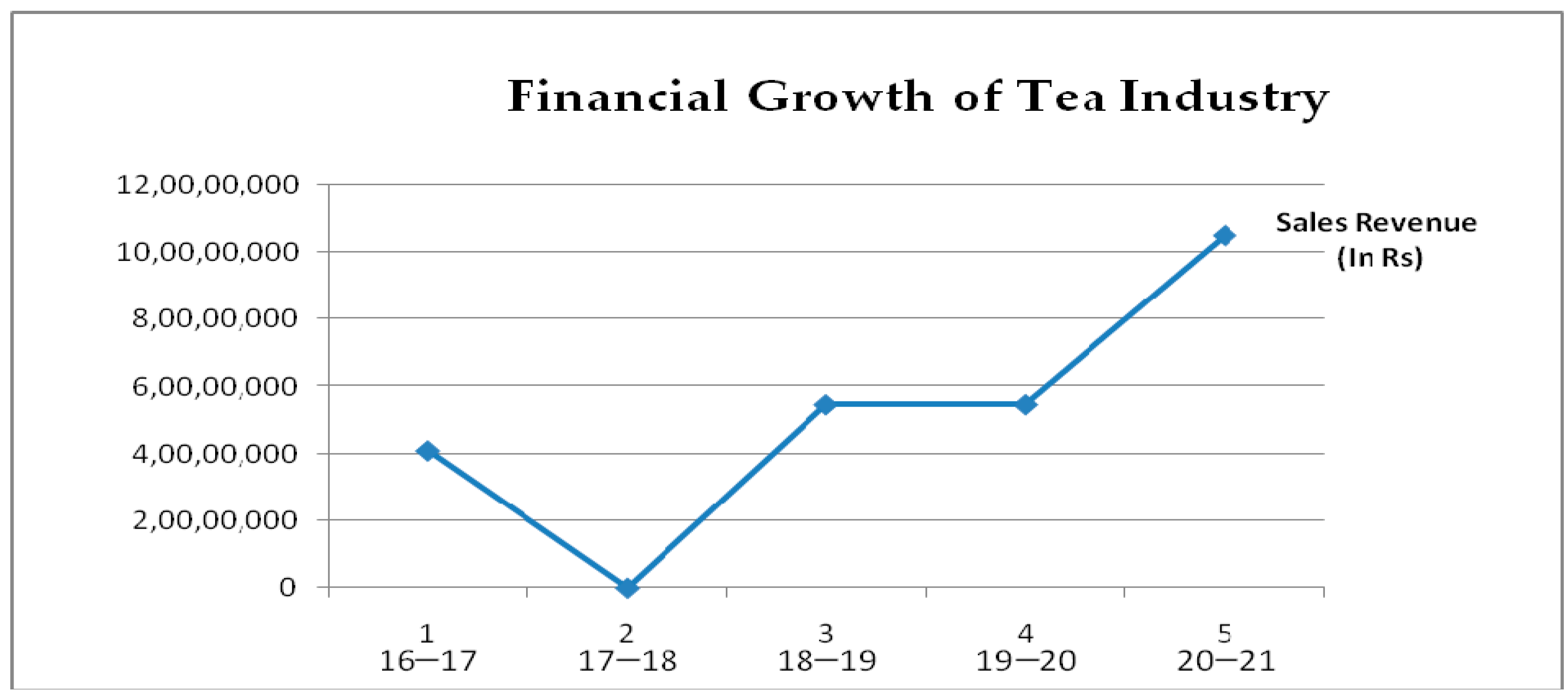

3.3.5. Financial Growth from Tea by the Tripura Tea Development Corporation Ltd.

4. Findings and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cingano, F. Trends in Income Inequality and its Impact on Economic Growth. In Social, Employment and Migration Working Paper; No. 163.2014; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economic Review of Tripura, Directorate of Economics & Statistics Planning (Statistics) Department, Government of Tripura. 2019–2020, 21. Available online: https://ecostat.tripura.gov.in/eco-review-2019-20.pdf (accessed on 29 March 2022).

- Wernerfelt, B. A resource-based view of the firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 1984, 5, 171–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, B. Evolution of tea industry in Tripura: Socio Primary economic and political factors. Int. Res. J. 2020, 9, 30–36. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, B. Ethnicity and Insurgency in Tripura. Sociol. Bull. 2003, 52, 221–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariyawardana, A.; Bailey, W.C. The Relationship between Core Resources and Strategies of Firms: The Case of Sri Lankan Value-Added Tea Producers. Sri Lankan J. Agric. Econ. 2002, 4, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanrar, B.; Kundu, S.; Khan, P.; Jain, V. Elemental Profiling for Discrimination of Geographical Origin of Tea (Camellia sinensis) in north-east region of India by ICP-MS coupled with Chemometric techniques. Food Chem. Adv. 2022, 1, 100073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://indianexpress.com/article/north-east-india/tripura/tea-plantation-durgabari-supply-ration-pds-system-assam-6271108/ (accessed on 27 August 2022).

- Baxter, P.; Jack, S. Qualitative Case Study Methodology: Study Design and Implementation for Novice Researchers. Qual. Rep. 2008, 13, 544–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widdowson, M. Case study research methodology. Int. J. Trans. Anal. Res. 2011, 2, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage Publications Inc.: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Grässel, E.; Schirmer, B. The use of volunteers to support family carers of dementia patients: Results of a prospective longitudinal study investigatingexpectations towards and experience with training and professional support. Z. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2006, 39, 217–226. [Google Scholar]

- Gulseçen, S.; Kubat, A. Teaching ICT to teacher candidates using PBL: A qualitative and quantitative evaluation. J. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2006, 9, 96–106. [Google Scholar]

- Rocklin, M.S.; Kashper, A.; Varvaloucas, G.C. Capacity Expansion/Contraction of a Facility with Demand Augmentation Dynamics. Oper. Res. 1984, 32, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayatri, P.; Arjunan, R. Livelihood Security of Tea Plantation Workers. Int. J. Res. Anal. Rev. 2018, 5, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Bhagat, R.M.; Baruah, R.D.; Safique, S. Climate and tea production with special reference to North Eastern India: A Review. J. Environ. Res. Dev. 2010, 4, 1017–1028. [Google Scholar]

- Dey, A.; Moyez, A.B.; Mandal, M.K.; Roy, S. Fabrication of solar cell using extracted bio-molecules from tea leaves and hybrid perovskites. Mater. Today Proc. 2016, 3, 3498–3504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ETP, 2016a: Ethical Tea Partnership. Where we Stand on… Wages & The Tea Industry. 2016. Available online: https://www.ethicalteapartnership.org/wp-content/uploads/Position-statementWages-Sept-2016_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- IANS. Tata Beverages to Study Impact of Climate Change on Assam Tea Production. The Times of India. 11 April 2016. Available online: http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/home/environment/flora-fauna/Tata-Beveragesto-study-impact-of-climate-change-on-Assamteaproduction/articleshow/51783980.cms (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Moitra, S. Respiratory Morbidity among Indian Tea Industry Workers. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2016, 7, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Idicheria, C.; Neelakantan, A.; Agrawal, A. Risk and Resilience In Assam’s Tea Industry: Mercy Corps & Okapi. Assam Rep. 2017, 25–26. Available online: www.okapia.co (accessed on 29 March 2022).

- PLA, 1951: Plantations Labor Act, 1951. Chapter I. Section 1(3)(a). Available online: http://www.teaboard.gov.in/pdf/policy/Plantations%20Labor%20Act_amended.pdf (accessed on 29 March 2022).

- Purohit, U. Plantations Labor Act 1951. Workers Rights. Hind Mazdoor Sabha. Available online: http://www.doccentre.org/docsweb/LABOURLAWS/bare-acts/plantation_act.htm (accessed on 29 March 2022).

- Debnath, S.; Debnath, P. Socio-Economic Condition of Tea Garden Workers of West Tripura District with Special Reference to Meghlipara Tea Estate. Int. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Stud. IJHSSS 2017, 4, 248–261. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharjee, P.N.; Singh, R.G. Tea Plantation and the Tribes of Tripura. In Tripura State Tribal Cultural Research Institute & Museum; Govt. of Tripura: Agartala, India, 1995; pp. 23–26. [Google Scholar]

- Sharon, A.A.; Lowell, W.B. The entrepreneurship of resource-based theory. J. Manag. 2001, 27, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stakeholders Theory of Business Ethics. Available online: https://philosophia.uncg.edu/phi361-matteson/module-1-why-does-business-need-ethics/freemans-stakeholder-theory/ (accessed on 24 August 2022).

- Arya, N. Indian Tea Scenario. Int. J. Sci. Res. Publ. 2013, 3, 2250–3153. [Google Scholar]

- Suchiradipta, B.; Saravanan, R. Agricultural Extension Systems in Tripura. Working Paper 1, MANAGE Centre for Agricultural Extension Innovations, Re-forms and Agripreneurship, National Institute for Agricultural Extension Management (MANAGE), Rajendranagar, Hyder-abad, India. 2017. Available online: https://www.manage.gov.in/publications/working%20papers/tripura-1.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- Swaminathan, M. Tripura Human Development Report, Govt of Tripura. 2007. Available online: https://niti.gov.in/planningcommission.gov.in/docs/plans/stateplan/sdr_pdf/tripura%20hdr.pdf (accessed on 24 August 2022).

- Bhattarai, R.; Mishra, N.; Bantilan, C.; Viswanathan, P.K. Employment Guarantee Programme and Dynamics of Rural Transformation in India: Challenges and Opportunities; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; ISBN 978-981-10-6262-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nath, S.K.; Dutta, A.M.; Datta, S.; Chattopadhyay, S.; Das, A.S. Hepatic Functional Status of the Tea Garden Workers of West Tripura District, Tripura, India. Int. J. Res. Anal. Rev. 2019, 6, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Soni, P.R.; Katoch, M.; Kumar, A.; Ladohiya, R.; Verma, P. Tea: Production, Composition, Consumption and its Potential an Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Agent. Int. J. Food Ferment Technol. 2015, 5, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: http://www.theshillongtimes.com/2013/09/02/tripurato-export-tea-to-middle-east-and-europe/ (accessed on 30 March 2022).

- Saha, J.K.; Adnan, K.M.; Sarker, S.A.; Bunerjee, S. Analysis of growth trends in area, production and yield of tea in Bangladesh. J. Agric. Food Res. 2021, 4, 100136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

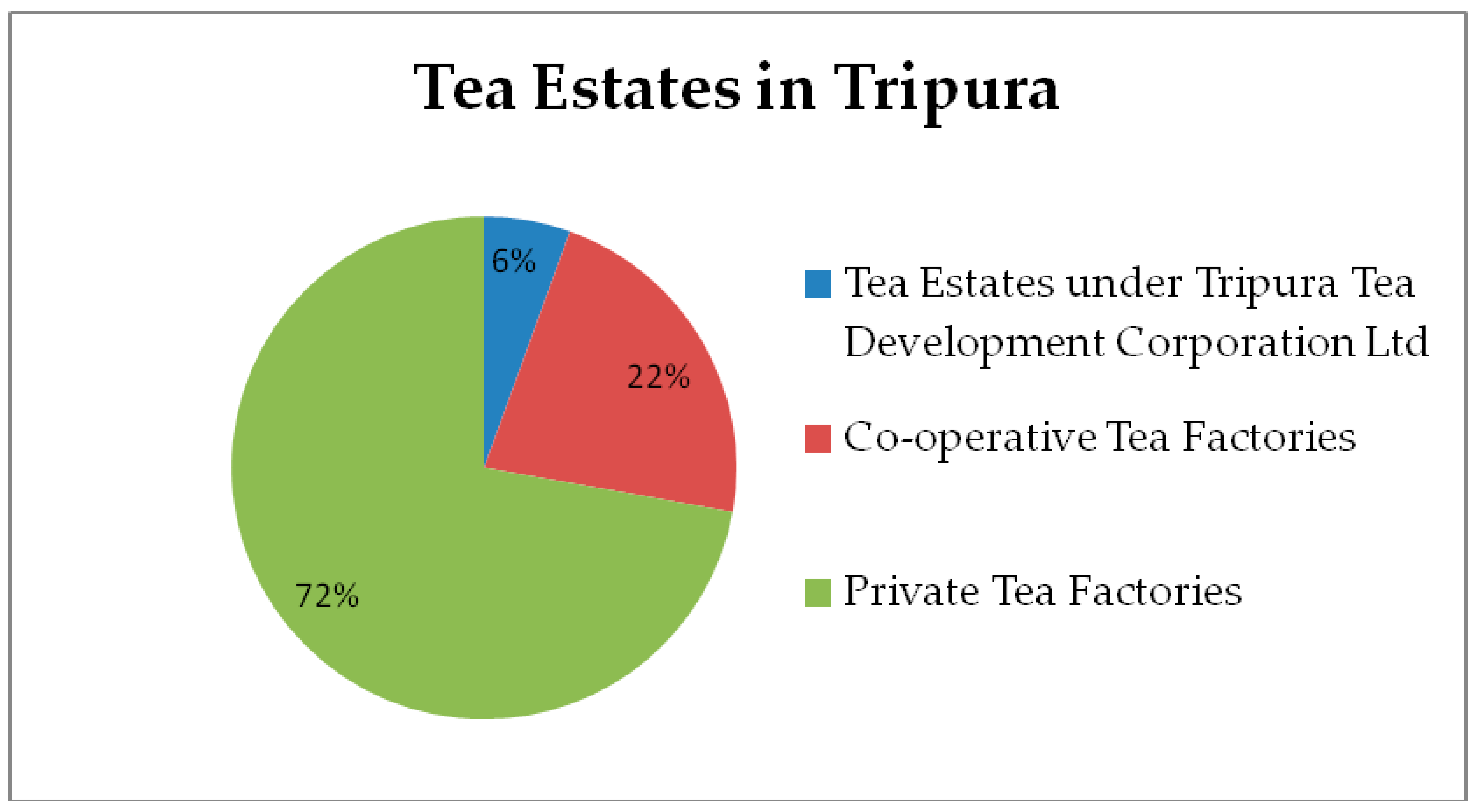

| Sl. No. | Estates | Number |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tea Estates under Tripura Tea Development Corporation Ltd. | 3 |

| 2 | Co-operative Tea Factories | 12 |

| 3 | Private Tea Factories | 39 |

| Total | 54 |

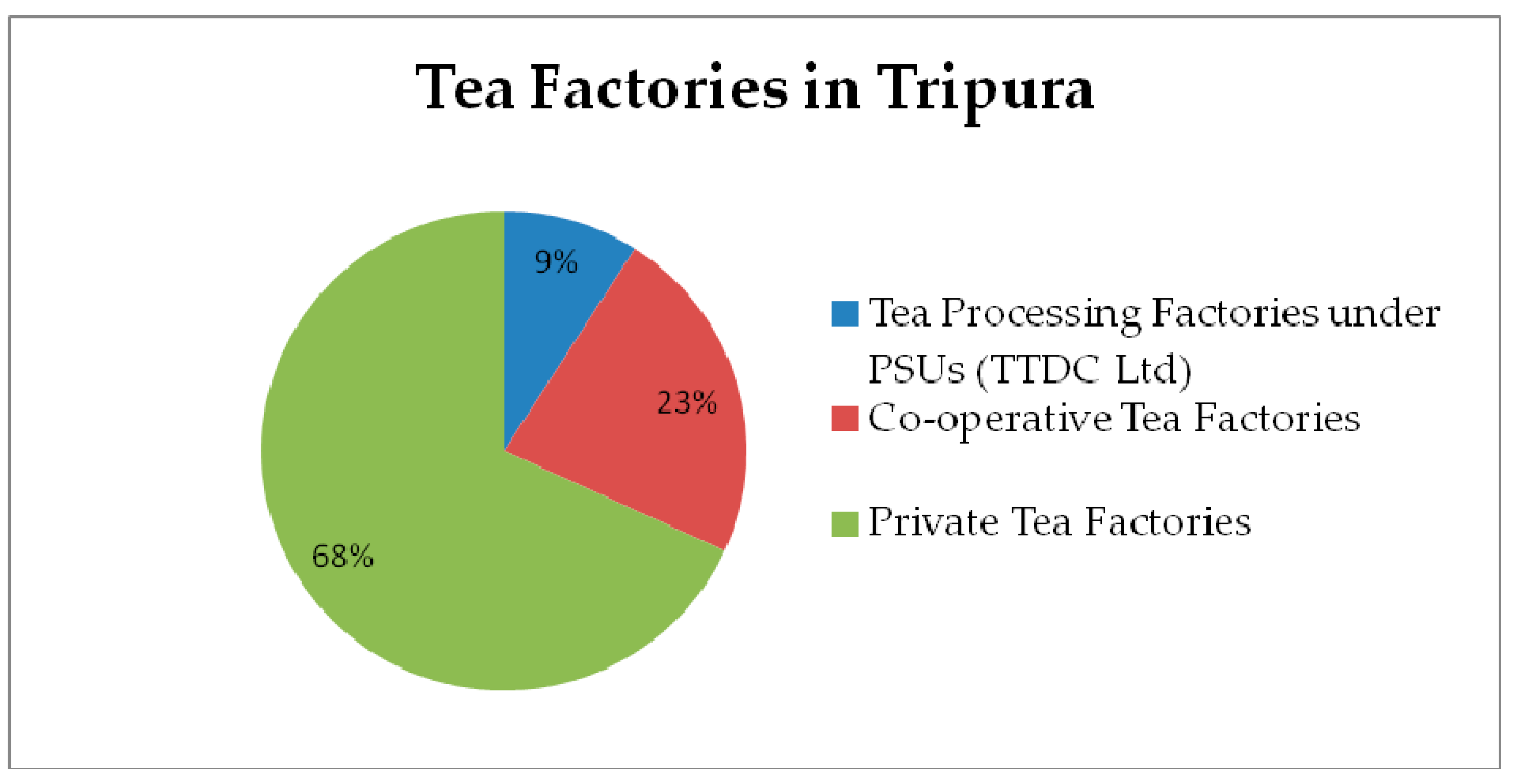

| Sl. No. | Factories | Number |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tea Processing Factories under PSUs (TTDCLtd) | 2 |

| 2 | Co-operative Tea Factories | 5 |

| 3 | Private Tea Factories | 15 |

| Total | 22 |

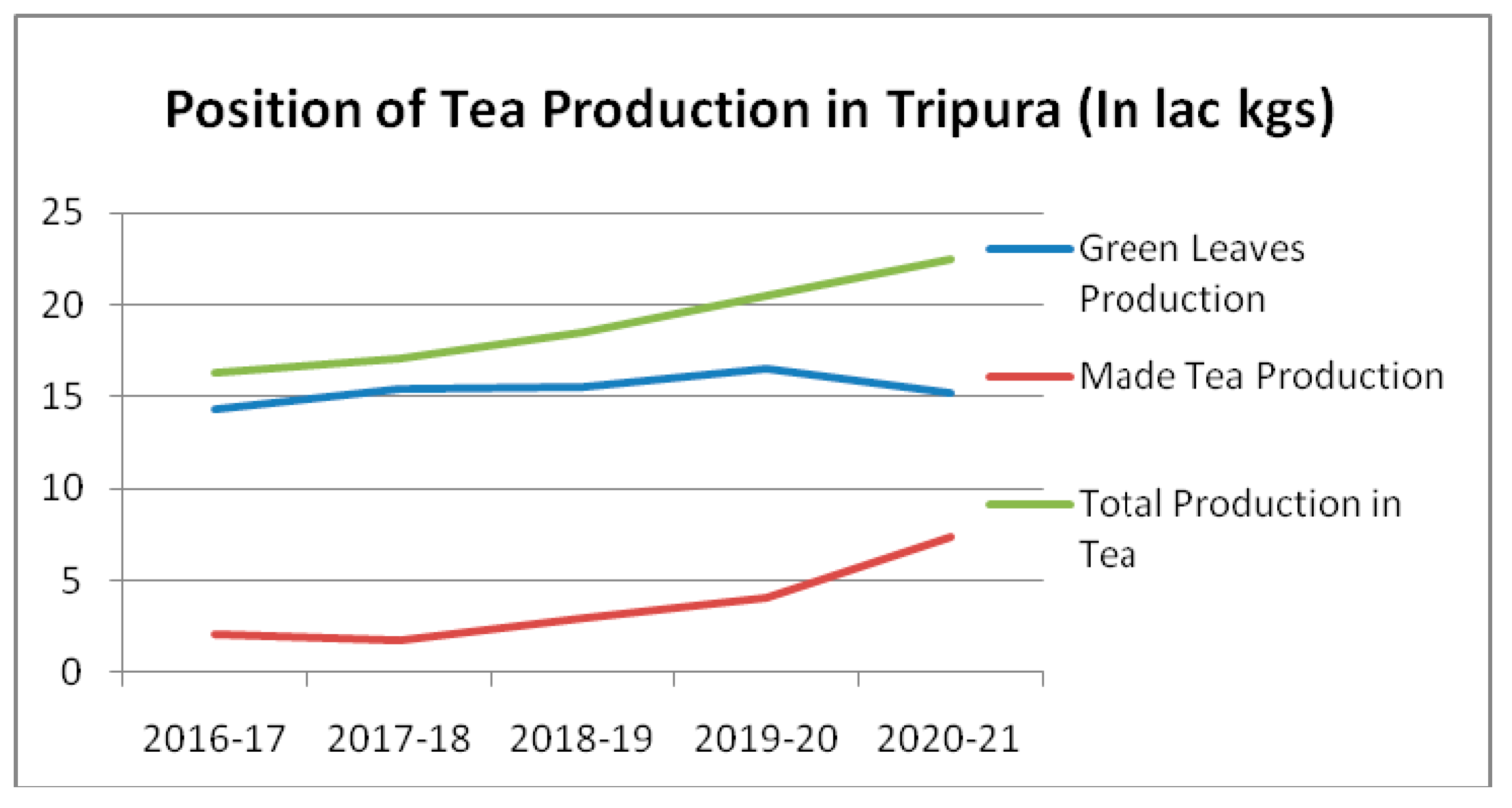

| Year | 2016–2017 | 2017–2018 | 2018–2019 | 2019–2020 | 2020–2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green Leaves Production | 14.31 | 15.40 | 15.56 | 16.50 | 15.19 |

| Made Tea Production | 2.00 | 1.72 | 2.98 | 4.04 | 7.35 |

| Total Production in Tea | 16.31 | 17.12 | 18.54 | 20.54 | 22.54 |

| Total Domestic consumption | 0.7% of total production | ||||

| Year | Sales Revenue (In INR) |

|---|---|

| 2016–2017 | 4 Crore 09 lakh 61 thousand |

| 2017–2018 | 3 Crore 64 lakh 87 thousand |

| 2018–2019 | 5 Crore 46 lakh 38 thousand |

| 2019–2020 | 5 Crore 46 lakh 73 thousand |

| 2020–2021 | 10 Crore 50 lakh 75 thousand |

| Financial Year | Revenue | Expenditure | Profit/Loss |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016–2017 | 58,687,141 | 79,484,176 | 20,797,035 (L) |

| 2017–2018 | 65,259,868 | 83,529,614 | 18,269,746 (L) |

| 2018–2019 | 85,847,698 | 68,297,698 | 17,550,000 |

| 2019–2020 | 54,673,000 | 35,648,000 | 19,025,000 |

| 2020–2021 | 105,075,000 | 84,010,000 | 21,065,000 |

| Year | Operational Profit |

|---|---|

| 2018–2019 | 1 Crore 75 lakh 50 thousand |

| 2019–2020 | 1 Crore 90 lakh 25 thousand |

| 2020–2021 | 2 Crore 10 lakh 65 thousand |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Islam, M.; Mukherjee, D.; Chatterjee, R.; Mitra, S. A Self-Reliant Tea Economy Offering Inclusive Growth: A Case of Tripureswari Tea, India. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2935. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy12122935

Islam M, Mukherjee D, Chatterjee R, Mitra S. A Self-Reliant Tea Economy Offering Inclusive Growth: A Case of Tripureswari Tea, India. Agronomy. 2022; 12(12):2935. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy12122935

Chicago/Turabian StyleIslam, Maidul, Debarshi Mukherjee, Rajesh Chatterjee, and Sudakhina Mitra. 2022. "A Self-Reliant Tea Economy Offering Inclusive Growth: A Case of Tripureswari Tea, India" Agronomy 12, no. 12: 2935. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy12122935

APA StyleIslam, M., Mukherjee, D., Chatterjee, R., & Mitra, S. (2022). A Self-Reliant Tea Economy Offering Inclusive Growth: A Case of Tripureswari Tea, India. Agronomy, 12(12), 2935. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy12122935