Hydrothermal Treatment with Different Solvents for Composite Recycling and Valorization Under Subcritical and Supercritical Conditions

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Manufacturing of CFs and Composites

1.2. Carbon Fiber Composites Recycling

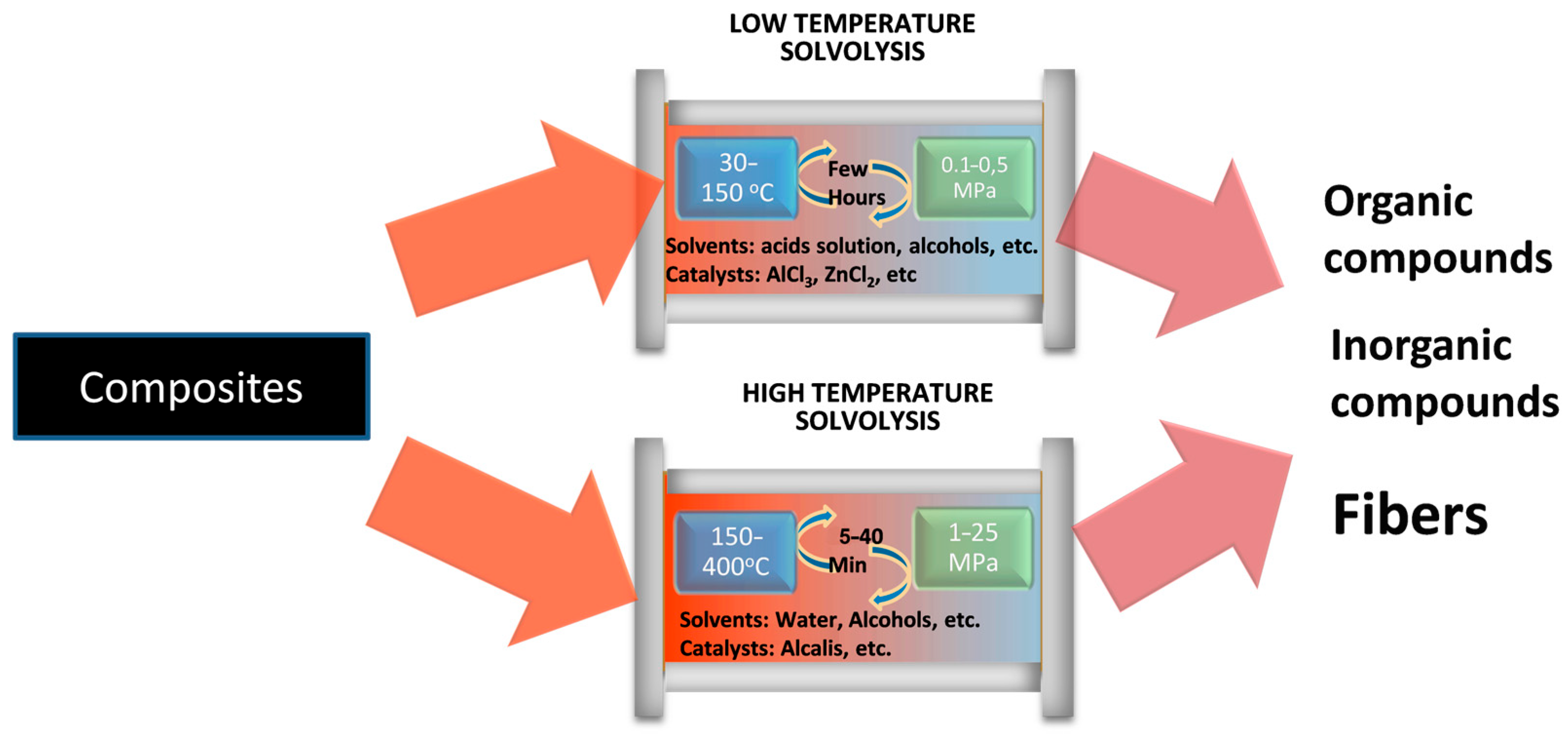

1.2.1. Low-Temperature Solvolysis

1.2.2. High-Temperature Solvolysis

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Composite Off-Cuts Specimens, Solvents, and Catalyzers

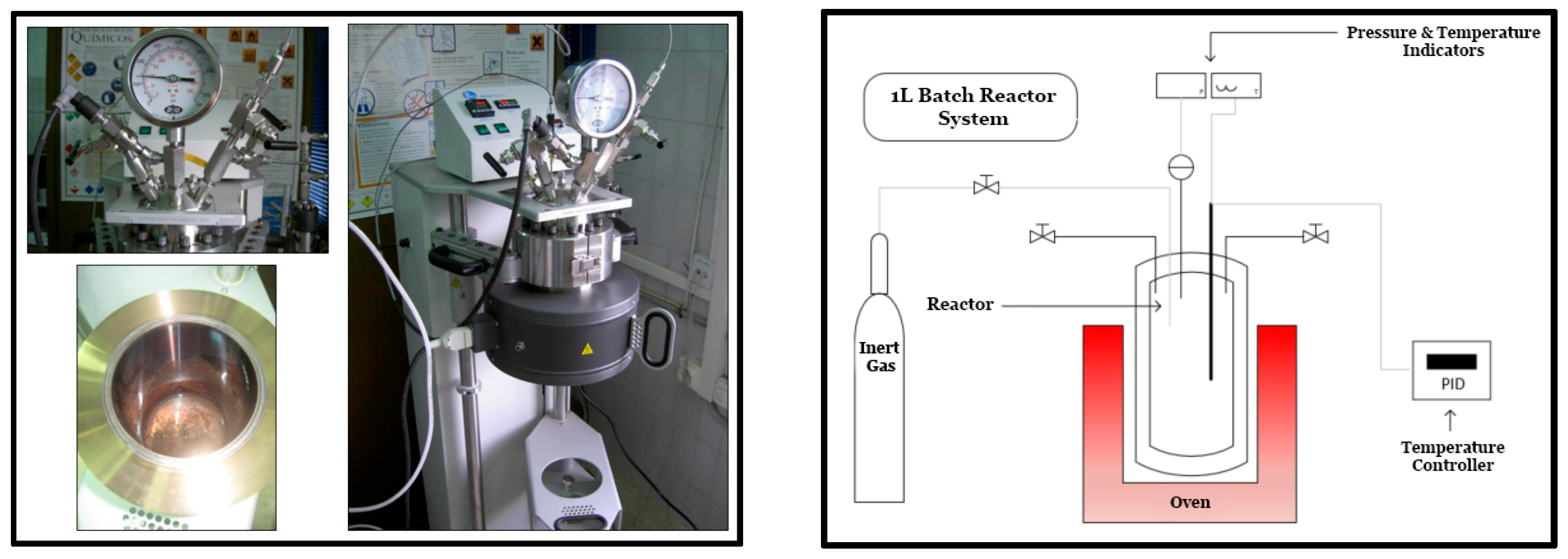

2.2. System and Procedure

2.3. Analytical Methods

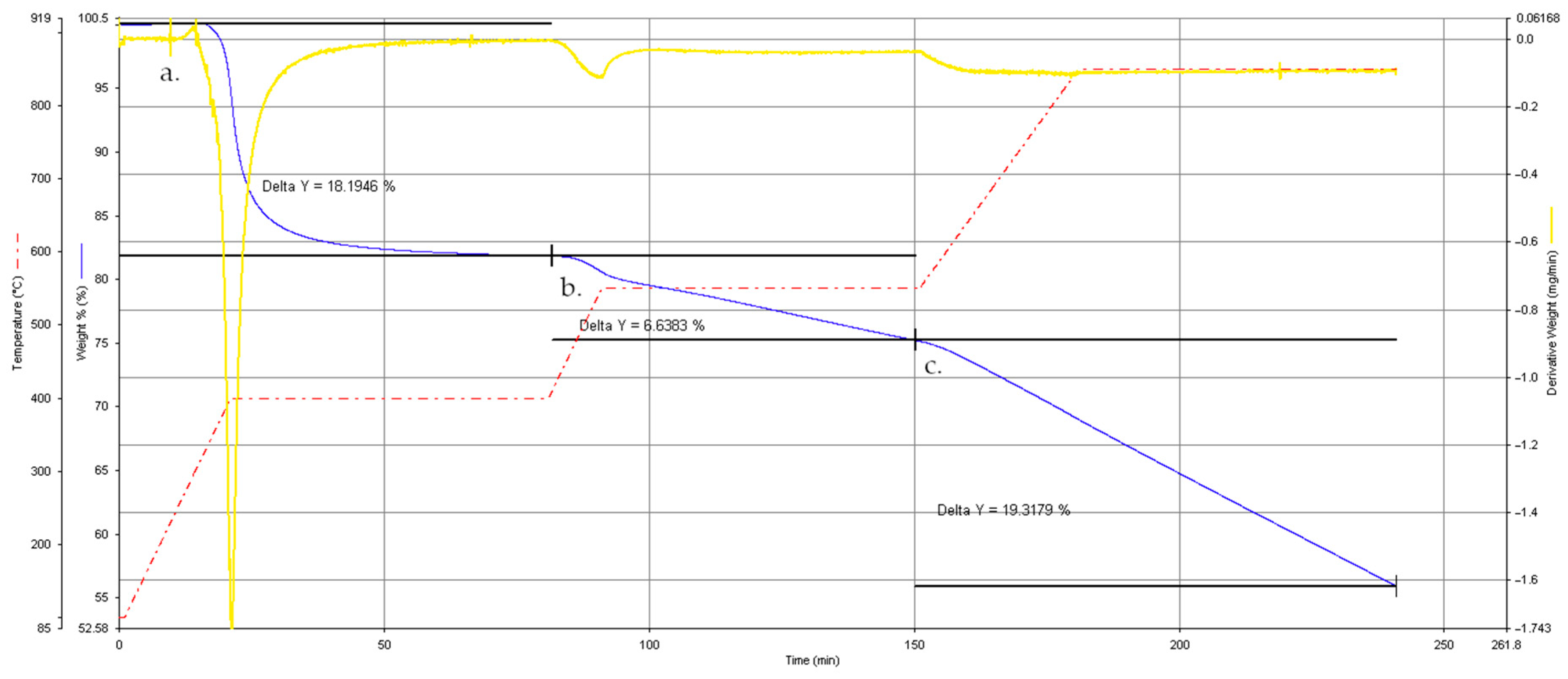

2.3.1. Thermogravimetric Analysis

2.3.2. Decomposition Rate

2.3.3. Scanning Electron Microscopy

2.3.4. Single-Fiber Tensile Tests

2.3.5. Gaseous Effluent Analysis

2.3.6. Liquid Effluent Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Thermogravimetric Behavior of the Original Composite Specimen (SpA)

3.2. Experimental Results Overview

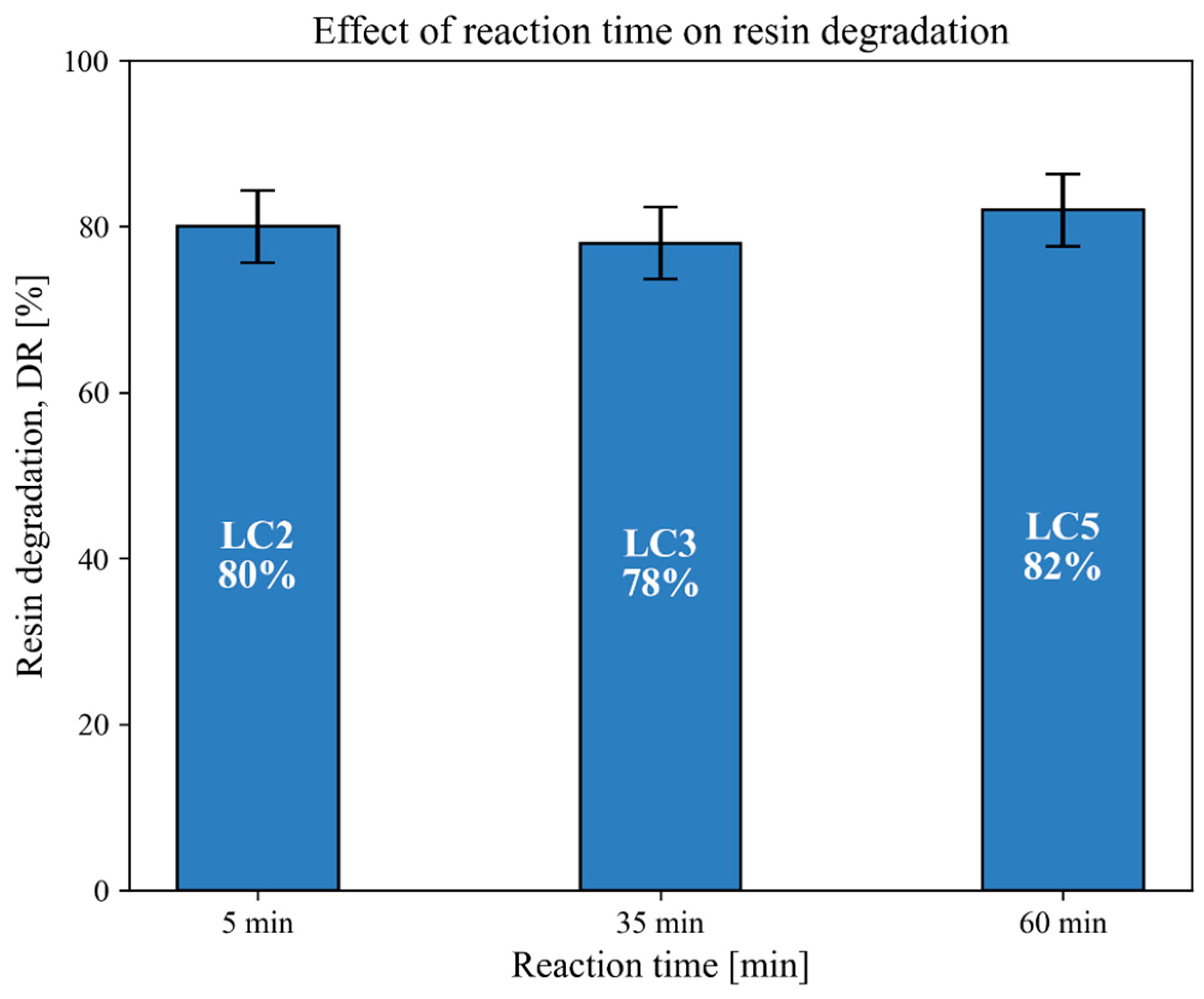

3.3. Effect of Reaction Time on Resin Degradation

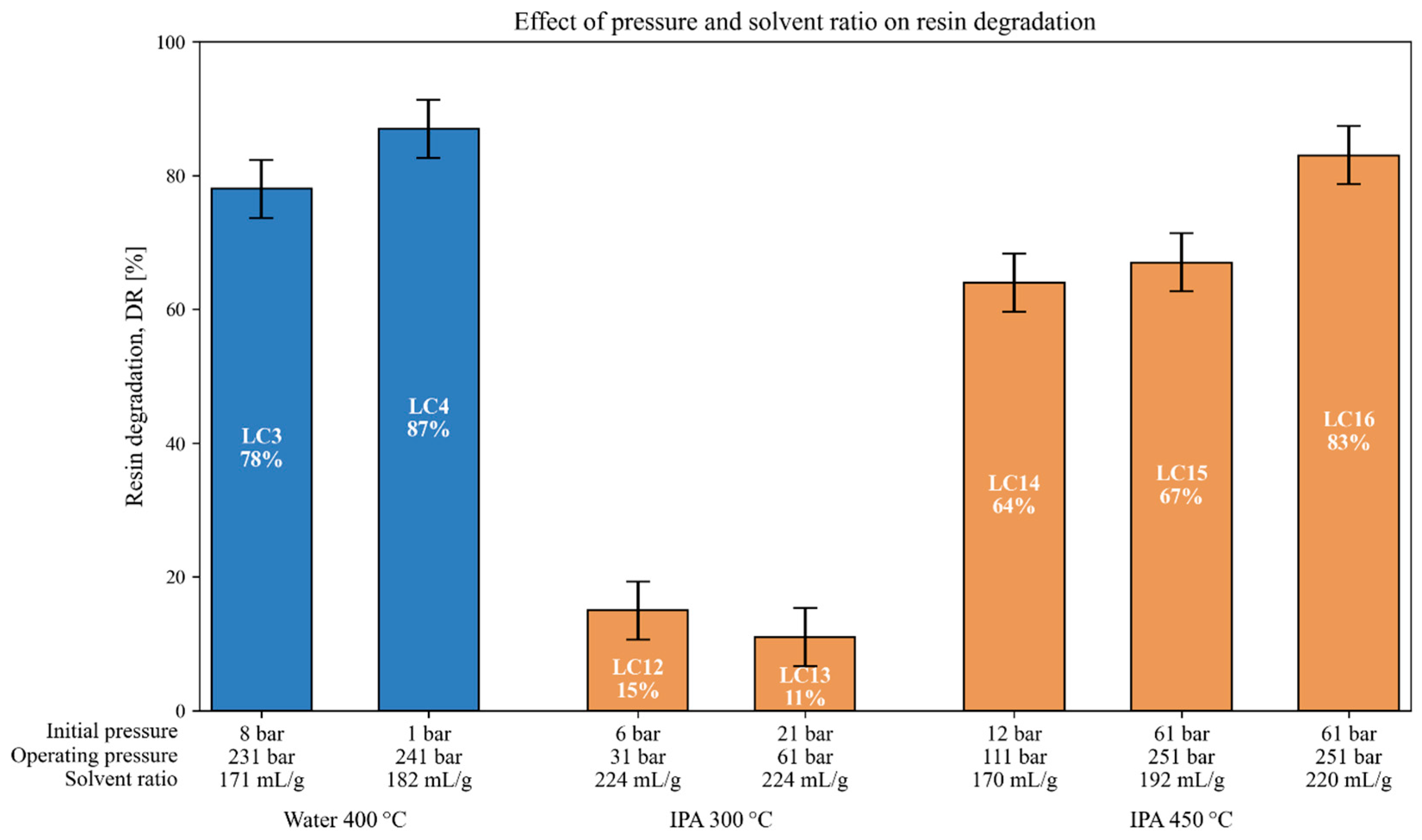

3.4. Interrelated Effects of Pressure and Solvent Ratio on Resin Degradation

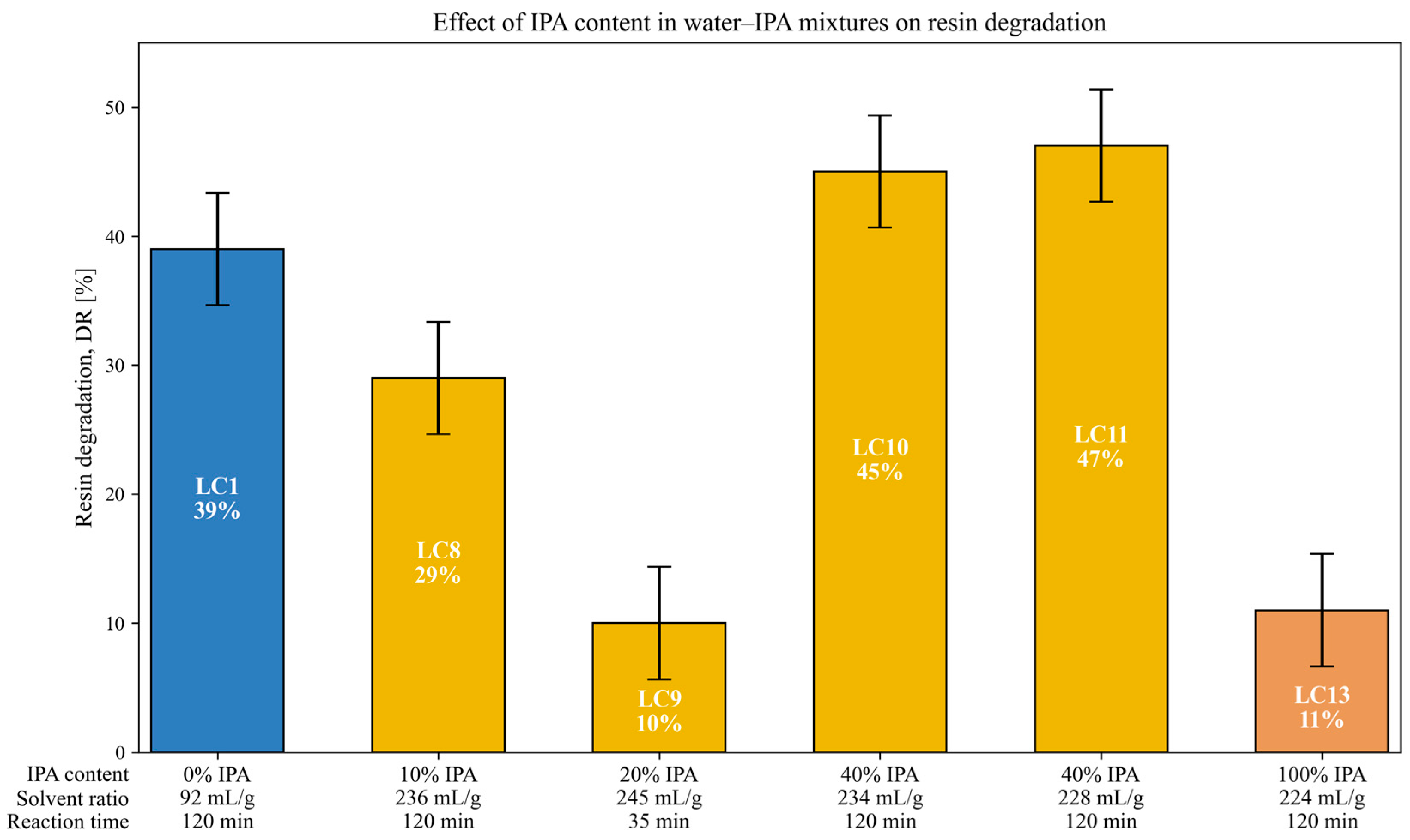

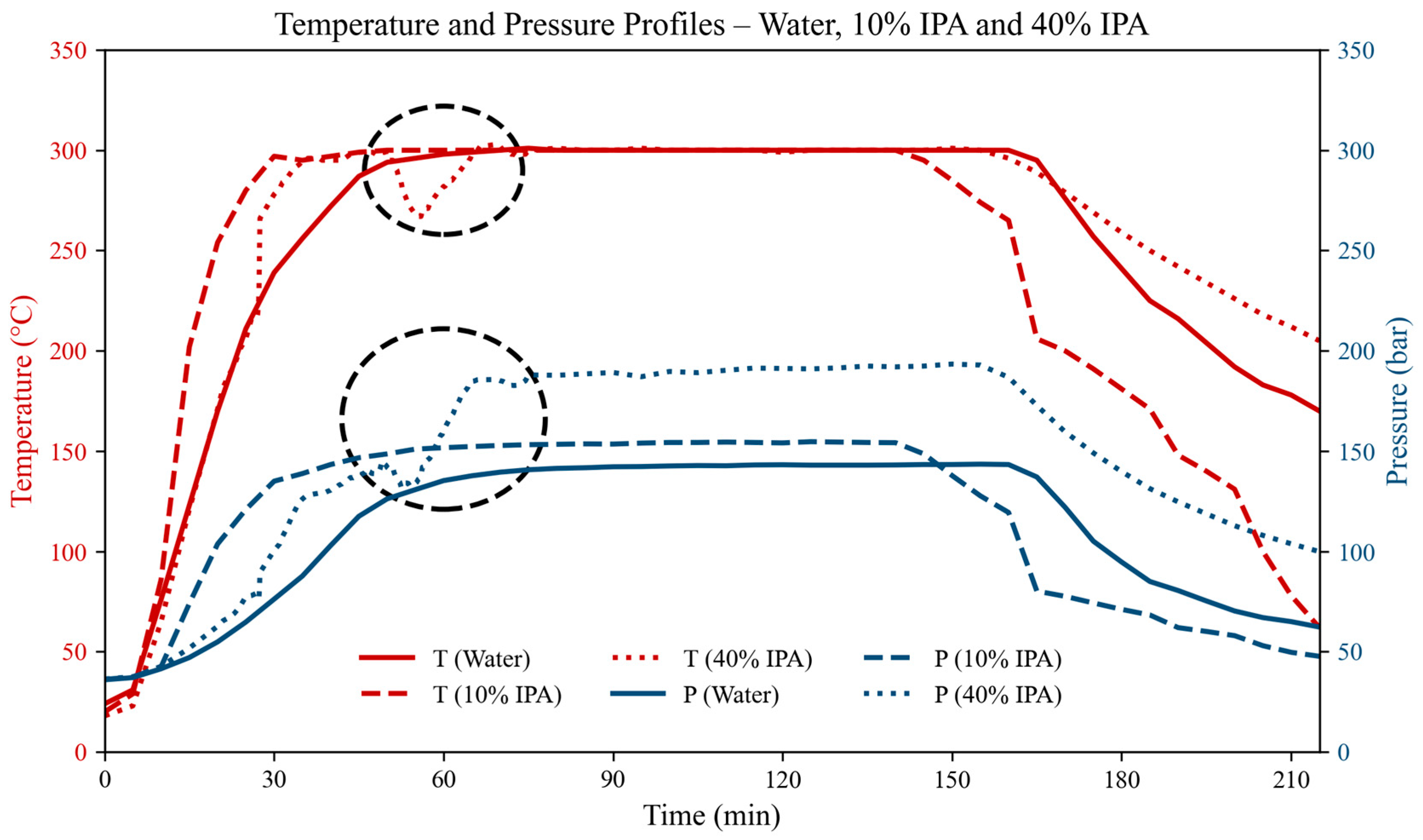

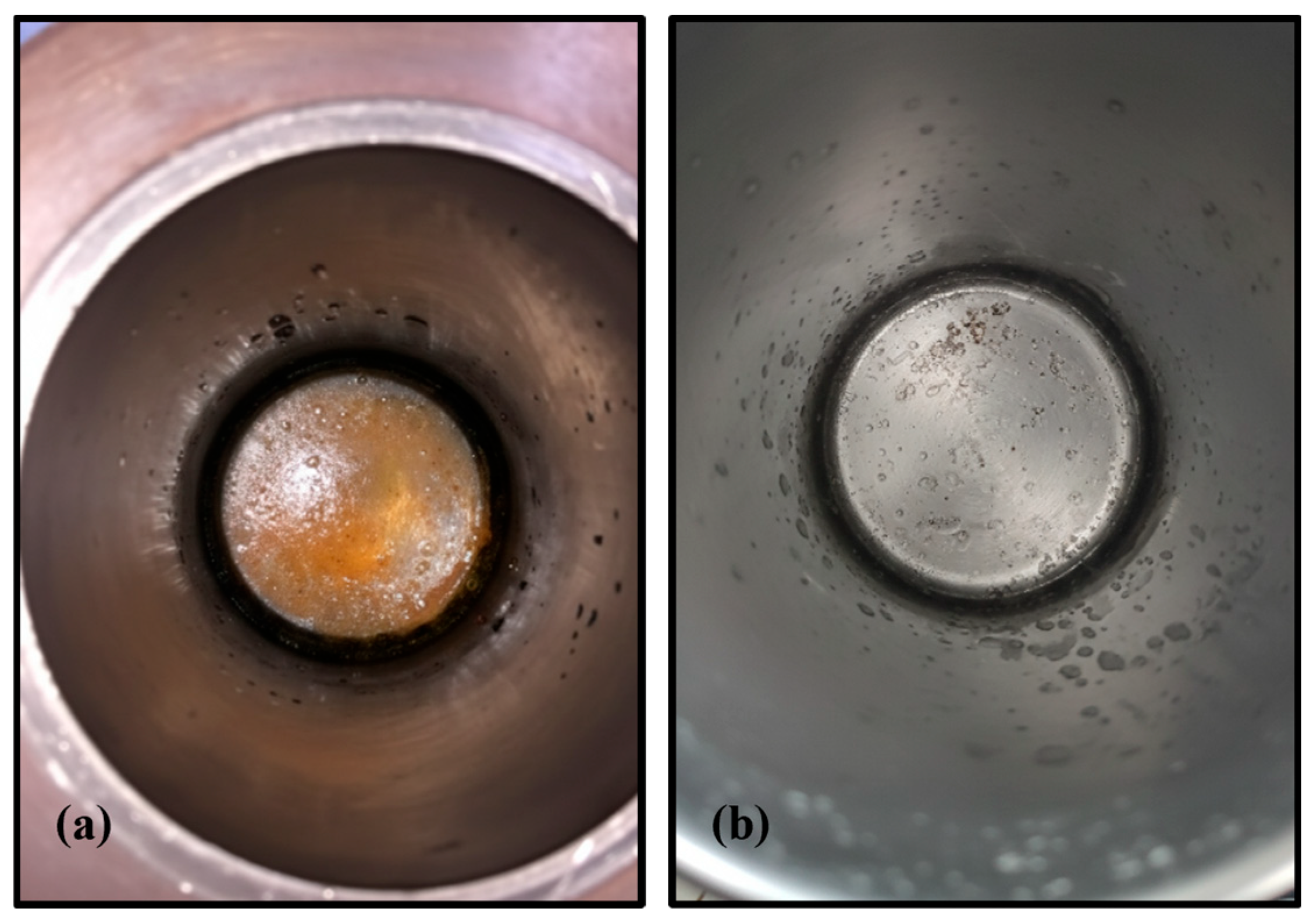

3.5. Effect of IPA Content in Solvent Mixture on Resin Degradation

3.6. Effect of Temperature, Operating Regime, and Catalyst on Resin Degradation

3.7. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

3.8. Tensile Strength Assays

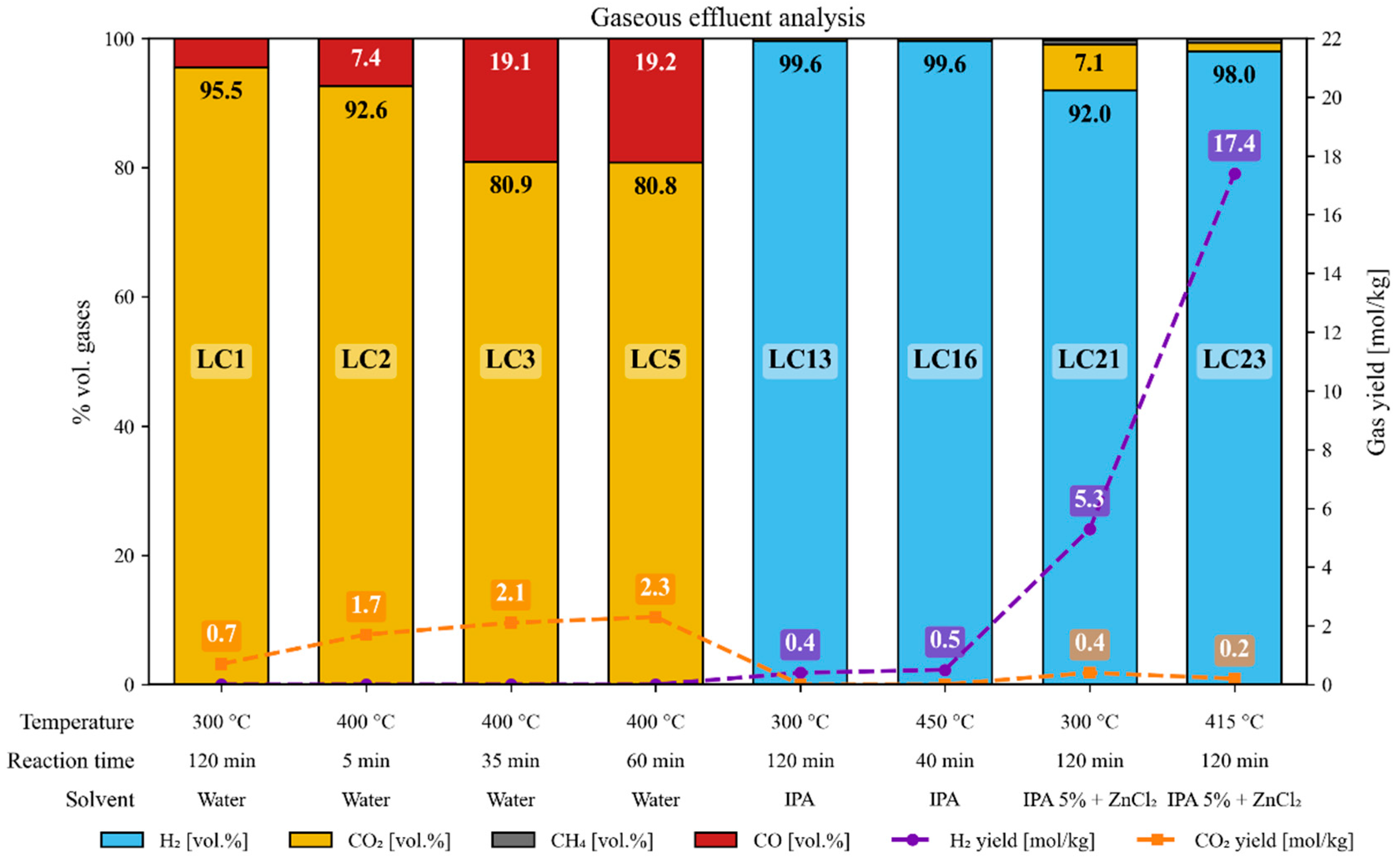

3.9. Gaseous Effluent

3.10. Liquid Effluent

4. Conclusions and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rybicka, J.; Tiwari, A.; Alvarez Del Campo, P.; Howarth, J. Capturing Composites Manufacturing Waste Flows through Process Mapping. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 91, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, R.M.; Martinho, A.; Oliveira, J.P. Recycling of Reinforced Glass Fibers Waste: Current Status. Materials 2022, 15, 1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, M. Recycled Carbon Fiber Composites Become a Reality. Reinf. Plast. 2018, 62, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauklis, A.E.; Karl, C.W.; Gagani, A.I.; Jørgensen, J.K. Composite Material Recycling Technology—State-of-the-Art and Sustainable Development for the 2020s. J. Compos. Sci. 2021, 5, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, C.; Loppinet-Serani, A.; Cansell, F.; Aymonier, C. Near- and Supercritical Solvolysis of Carbon Fibre Reinforced Polymers (CFRPs) for Recycling Carbon Fibers as a Valuable Resource: State of the Art. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2012, 66, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahaman, M.S.A.; Ismail, A.F.; Mustafa, A. A Review of Heat Treatment on Polyacrylonitrile Fiber. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2007, 92, 1421–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, B.; Wang, Y.; Gong, H.; Su, M. Recycling, Remanufacturing and Applications of Semi-Long and Long Carbon Fibre from Waste Composites: A Review. Appl. Compos. Mater. 2025, 32, 1237–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbon Fiber Market Size to Hit USD 6.77 Billion by 2034. Available online: https://www.precedenceresearch.com/carbon-fiber-market (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Carbon Fiber Market Size & Forecast [Latest]. Available online: https://www.marketsandmarkets.com/Market-Reports/carbon-fiber-396.html (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Recycled Carbon Fiber Market Size & Share Report 2032. Available online: https://datahorizzonresearch.com/recycled-carbon-fiber-market-2649 (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Giorgini, L.; Benelli, T.; Brancolini, G.; Mazzocchetti, L. Recycling of Carbon Fiber Reinforced Composite Waste to Close Their Life Cycle in a Cradle-to-Cradle Approach. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2020, 26, 100368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chevali, V.S.; Wang, H.; Wang, C.-H. Current Status of Carbon Fibre and Carbon Fibre Composites Recycling. Compos. Part B Eng. 2020, 193, 108053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borjan, D.; Knez, Ž.; Knez, M. Recycling of Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Composites—Difficulties and Future Perspectives. Materials 2021, 14, 4191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branfoot, C.; Folkvord, H.; Keith, M.; Leeke, G.A. Recovery of Chemical Recyclates from Fibre-Reinforced Composites: A Review of Progress. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2023, 215, 110447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, R.; Tölli, H.; Valkjärvi, M. Towards a Sustainable Future: Exploring Methods, Technologies, and Applications for Thermoset Composite Recycling; Centria University of Applied Sciences: Kokkola, Finland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Meng, L.; Huang, Y.; Du, J. Recycling of Carbon/Epoxy Composites. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2004, 94, 1912–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-H.; Choi, H.-O.; Kim, J.-S.; Lee, C.-K.; Kim, Y.-K.; Ju, C.-S. Circulating Flow Reactor for Recycling of Carbon Fiber from Carbon Fiber Reinforced Epoxy Composite. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2011, 28, 449–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xu, P.-L.; Zhu, Y.-K.; Ding, J.-P.; Xue, L.-X.; Wang, Y.-Z. A Promising Strategy for Chemical Recycling of Carbon Fiber/Thermoset Composites: Self-Accelerating Decomposition in a Mild Oxidative System. Green Chem. 2012, 14, 3260–3263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Li, J.; Ding, J. Chemical Recycling of Carbon Fibre/Epoxy Composites in a Mixed Solution of Peroxide Hydrogen and N,N-Dimethylformamide. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2013, 82, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cui, X.; Ge, H.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Li, J.; Deng, T.; Qin, Z.; Hou, X. Chemical Recycling of Carbon Fiber Reinforced Epoxy Resin Composites via Selective Cleavage of the Carbon–Nitrogen Bond. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2015, 3, 3332–3337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, J.N.; Nutt, S.R.; Williams, T.J. Recycling Benzoxazine-Epoxy Composites via Catalytic Oxidation. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 7227–7231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Gao, X.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Nguyen, T.T.; Guo, M. Recycling Carbon Fiber from Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Polymer and Its Reuse in Photocatalysis: A Review. Polymers 2023, 15, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogiantzi, C.; Tserpes, K. A Preliminary Investigation on a Water- and Acetone-Based Solvolysis Recycling Process for CFRPs. Materials 2024, 17, 1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protsenko, A.E. Recycling of Carbon Fiber Reinforced Plastic with Supercritical Ethanol in the Presence of Sn, Cu, Co Salts. In Proceedings of 2023 the 6th International Conference on Mechanical Engineering and Applied Composite Materials; Yue, X., Yuan, K., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 191–199. [Google Scholar]

- Okajima, I.; Hiramatsu, M.; Shimamura, Y.; Awaya, T.; Sako, T. Chemical Recycling of Carbon Fiber Reinforced Plastic Using Supercritical Methanol. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2014, 91, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okajima, I.; Sako, T. Recycling of Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Plastic Using Supercritical and Subcritical Fluids. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2017, 19, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, J.R.; Lester, E.; Kingman, S.; Pickering, S.; Wong, K.H. Supercritical Propanol, a Possible Route to Composite Carbon Fibre Recovery: A Viability Study. Compos. Part Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2006, 37, 2171–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piñero-Hernanz, R.; García-Serna, J.; Dodds, C.; Hyde, J.; Poliakoff, M.; Cocero, M.J.; Kingman, S.; Pickering, S.; Lester, E. Chemical Recycling of Carbon Fibre Composites Using Alcohols under Subcritical and Supercritical Conditions. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2008, 46, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; Pickering, S.J.; Lester, E.H.; Turner, T.A.; Wong, K.H.; Warrior, N.A. Characterisation of Carbon Fibres Recycled from Carbon Fibre/Epoxy Resin Composites Using Supercritical n-Propanol. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2009, 69, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Lu, C.; Jing, D.; Chang, C.; Liu, N.; Hou, X. Recycling of Carbon Fibers in Epoxy Resin Composites Using Supercritical 1-Propanol. New Carbon Mater. 2016, 31, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Deng, Z.; Dong, C.; Fan, J.; Ren, Y. A Closed-Loop Recycling Process for Carbon Fiber Reinforced Vinyl Ester Resin Composite. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 446, 137254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokoli, H.U.; Beauson, J.; Simonsen, M.E.; Fraisse, A.; Brøndsted, P.; Søgaard, E.G. Optimized Process for Recovery of Glass- and Carbon Fibers with Retained Mechanical Properties by Means of near- and Supercritical Fluids. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2017, 124, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okajima, I.; Sako, T. Recycling Fiber-Reinforced Plastic Using Supercritical Acetone. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2019, 163, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okajima, I.; Yamada, K.; Sugeta, T.; Sako, T. Decomposition of epoxy resin and recycling of CFRP with sub- and supercritical water. Kagaku Kogaku Ronbunshu 2002, 28, 553–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piñero-Hernanz, R.; Dodds, C.; Hyde, J.; García-Serna, J.; Poliakoff, M.; Lester, E.; Cocero, M.J.; Kingman, S.; Pickering, S.; Wong, K.H. Chemical Recycling of Carbon Fibre Reinforced Composites in Nearcritical and Supercritical Water. Compos. Part Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2008, 39, 454–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Wang, Z.; Feng, L. Chemical Recycling of Carbon Fibers Reinforced Epoxy Resin Composites in Oxygen in Supercritical Water. Mater. Des. 2010, 31, 999–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.N.; Kim, Y.-O.; Kim, S.Y.; Park, M.; Yang, B.; Kim, J.; Jung, Y.C. Application of Supercritical Water for Green Recycling of Epoxy-Based Carbon Fiber Reinforced Plastic. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2019, 173, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, M.J.; Leeke, G.A.; Khan, P.; Ingram, A. Catalytic Degradation of a Carbon Fibre Reinforced Polymer for Recycling Applications. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2019, 166, 188–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, C.C.; Zeng, C.; Zhang, C.; Wang, B. Recycling of Woven Carbon-Fibre-Reinforced Polymer Composites Using Supercritical Water. Environ. Technol. 2012, 33, 639–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Jiang, Z.; Tang, T. Chemical Recycling of Carbon Fibre Reinforced Epoxy Resin Composites in Subcritical Water: Synergistic Effect of Phenol and KOH on the Decomposition Efficiency. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2012, 97, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, K.; Ma, L.; Tang, T. Insight into the Role of Potassium Hydroxide for Accelerating the Degradation of Anhydride-Cured Epoxy Resin in Subcritical Methanol. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2016, 107, 605–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Fernández, J.M.; Abelleira-Pereira, J.M.; García-Jarana, B.; Cardozo-Filho, L.; Sánchez-Oneto, J.; Portela-Miguélez, J.R. Catalytic Hydrothermal Treatment for the Recycling of Composite Materials from the Aeronautics Industry. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Den, W.; Ko, F.-H.; Huang, T.-Y. Treatment of Organic Wastewater Discharged from Semiconductor Manufacturing Process by Ultraviolet/Hydrogen Peroxide and Biodegradation. IEEE Trans. Semicond. Manuf. 2002, 15, 540–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodes, M.; Marrone, P.A.; Hong, G.T.; Smith, K.A.; Tester, J.W. Salt Precipitation and Scale Control in Supercritical Water Oxidation—Part A: Fundamentals and Research. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2004, 29, 265–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales Ibarra, R.; Sasaki, M.; Goto, M.; Quitain, A.T.; García Montes, S.M.; Aguilar-Garib, J.A. Carbon Fiber Recovery Using Water and Benzyl Alcohol in Subcritical and Supercritical Conditions for Chemical Recycling of Thermoset Composite Materials. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2015, 17, 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 11566:1996; Carbon Fibre—Determination of the Tensile Properties of Single-Filament Specimens. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1996.

- Xu, D.; Liu, L.; Wei, N.; Guo, Y.; Wang, S.; Wu, Z.; Duan, P. Catalytic Supercritical Water Gasification of Aqueous Phase Directly Derived from Microalgae Hydrothermal Liquefaction. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 26181–26192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, E.W.; Baird, R.B.; Eaton, A.D. (Eds.) Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, 23rd ed.; American Water Works Association (AWWA, WEF and APHA): Denver, CO, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Giżyński, M.; Romelczyk-Baishya, B. Investigation of Carbon Fiber–Reinforced Thermoplastic Polymers Using Thermogravimetric Analysis. J. Thermoplast. Compos. Mater. 2021, 34, 126–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, P.; Glinz, J.; Stadlbauer, W.; Burgstaller, C.; Archodoulaki, V.-M. The Effect of Thermally Desized Carbon Fibre Reinforcement on the Flexural and Impact Properties of PA6, PPS and PEEK Composite Laminates: A Comparative Study. Compos. Part B Eng. 2021, 215, 108844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuyan, L.; Guohua, S.; Linghui, M. Recycling of Carbon Fibre Reinforced Composites Using Water in Subcritical Conditions. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2009, 520, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anikeev, V.I.; Yermakova, A.; Manion, J.; Huie, R. Kinetics and Thermodynamics of 2-Propanol Dehydration in Supercritical Water. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2004, 32, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelman. Sizing for Glass, Carbon and Natural Fibers. Available online: https://www.michelman.com/markets/reinforced-plastic-composites/fiber-sizing/ (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Morgan, P. Carbon Fibers and Their Composites; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2005; ISBN 978-0-429-11682-7. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzer, E.; Frohs, W.; Heine, M. Optimization of Stabilization and Carbonization Treatment of PAN Fibres and Structural Characterization of the Resulting Carbon Fibres. Carbon 1986, 24, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, M.; Kong, H.; Ding, X.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, L.; Cao, Y.; Yu, M. Effect of Different Pressures of Supercritical Carbon Dioxide on the Microstructure of PAN Fibers during the Hot-Drawing Process. Polymers 2019, 11, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Composite Type | SpA | SpB |

|---|---|---|

| Curing temperature (°C) | 180 | 120 |

| Dimensions (mm) | 25 × 11 × 2 | 25 × 11 × 2 |

| Weight (g) | 0.5–1.0 | 0.5–1.0 |

| Fiber type | AS4 | T800S |

| Fiber diameter (µm) | 7.1 | 5 |

| Resin content (wt.%) | 34 ± 2% | 34 ± 2% |

| Exp. | T [°C] | P [bar(a)] | tr [min] | Solvent [wt.%] | Catalyst | P0 [bar(a)] | Ratio [mL/g] | Composite Type | SC | DR [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LC1 | 300 | 141 | 120 | Water | - | 37 | 92 | SpA | N ** | 39 |

| LC2 | 400 | 231 | 5 | Water | - | 11 | 164 | SpA | Y ** | 80 |

| LC3 | 400 | 231 | 35 | Water | - | 8 | 171 | SpA | Y | 78 |

| LC4 | 400 | 241 | 35 | Water | - | 1 | 182 | SpA | Y | 87 |

| LC5 | 400 | 231 | 60 | Water | - | 11 | 174 | SpA | Y | 82 |

| LC6 | 425 | 251 | 35 | Water | - | 11 | 176 | SpA | Y | 78 |

| LC7 | 550 | 231 | 40 | IPA * 5% | - | 1 | 159 | SpB | Y | 79 |

| LC8 | 300 | 151 | 120 | IPA 10% | - | 37 | 236 | SpA | N | 29 |

| LC9 | 300 | 156 | 35 | IPA 20% | - | 37 | 245 | SpA | N | 10 |

| LC10 | 300 | 196 | 120 | IPA 40% | - | 37 | 234 | SpA | Y | 45 |

| LC11 | 300 | 196 | 120 | IPA 40% | - | 37 | 228 | SpA | Y | 47 |

| LC12 | 300 | 31 | 120 | IPA | - | 6 | 224 | SpA | N | 15 |

| LC13 | 300 | 61 | 120 | IPA | - | 21 | 224 | SpA | Y | 11 |

| LC14 | 450 | 111 | 40 | IPA | - | 12 | 170 | SpA | Y | 64 |

| LC15 | 450 | 251 | 40 | IPA | - | 61 | 192 | SpA | Y | 67 |

| LC16 | 450 | 251 | 40 | IPA | - | 61 | 220 | SpA | Y | 83 |

| LC17 | 450 | 251 | 40 | IPA | - | 61 | 221 | SpB | Y | 80 |

| LC18 | 300 | 141 | 120 | Acet. 10% | - | 38 | 233 | SpA | N | 33 |

| LC19 | 420 | 251 | 40 | Acet. 80% | - | 66 | 176 | SpA | Y | 57 |

| LC20 | 200 | 17 | 120 | IPA 5% | ZnCl2 0.1 M | 1 | 192 | SpB | N | 2 |

| LC21 | 300 | 88 | 120 | IPA 5% | ZnCl2 0.1 M | 1 | 192 | SpB | N | 45 |

| LC22 | 400 | 193 | 120 | IPA 5% | ZnCl2 0.1 M | 1 | 193 | SpB | N | 78 |

| LC23 | 415 | 233 | 120 | IPA 5% | ZnCl2 0.1 M | 1 | 192 | SpB | Y | 92 |

| Test | Original SpA | LC4 | Original SpB | LC23 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average measured diameter (μm) | 7.58 ± 0.2 | 7.36 ± 0.13 | 5.89 ± 0.04 | 5.94 ± 0.05 |

| Average sizing thickness (μm) | 0.25 ± 0.1 | 0.13 ± 0.07 | 0.45 ± 0.02 | 0.47 ± 0.03 |

| Exp. | COD0 (mg O2/L) | CODf (mg O2/L) | COD Removal (%) | TOC0 (mg C/L) | TOCf (mg C/L) | TOC Removal (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LC2 | 0 | 1716 | - | 0 | 465 | - |

| LC4 | 0 | 23,709 | - | 0 | 730 | - |

| LC5 | 0 | 1898 | - | 0 | 508 | - |

| LC7 | 102,947 | 31,570 | 69 | 26,915 | 9005 | 67 |

| LC13 | 1,793,514 | 1,755,993 | 2 | 210,274 | 205,726 | 2 |

| LC16 | 1,792,651 | 1,729,640 | 4 | 210,349 | 202,800 | 4 |

| LC21 | 115,557 | 87,286 | 24 | 30,845 | 21,880 | 29 |

| LC22 | 112,093 | 9875 | 91 | 29,430 | 2167 | 93 |

| LC23 | 85,651 | 13,253 | 85 | 21,005 | 2937 | 86 |

| Exp. | pH0 | pHf | Conductivity0 (μS/cm) | Conductivityf (μS/cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LC2 | 5.7 | 5.8 | 9 | 142 |

| LC4 | 5.7 | 6.1 | 8 | 89 |

| LC5 | 5.7 | 6.0 | 15 | 177 |

| LC7 | 5.4 | 4.3 | 2 | 1019 |

| LC21 | 5.8 | 5.7 | 15 | 17 |

| LC22 | 6.0 | 5.5 | 15 | 21 |

| LC23 | 5.9 | 4.7 | 17 | 22 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Vázquez-Fernández, J.M.; García-Jarana, B.; Ramírez-del Solar, M.; Cardozo-Filho, L.; Portela-Miguélez, J.R.; Abelleira-Pereira, J.M. Hydrothermal Treatment with Different Solvents for Composite Recycling and Valorization Under Subcritical and Supercritical Conditions. Polymers 2026, 18, 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010089

Vázquez-Fernández JM, García-Jarana B, Ramírez-del Solar M, Cardozo-Filho L, Portela-Miguélez JR, Abelleira-Pereira JM. Hydrothermal Treatment with Different Solvents for Composite Recycling and Valorization Under Subcritical and Supercritical Conditions. Polymers. 2026; 18(1):89. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010089

Chicago/Turabian StyleVázquez-Fernández, José M., Belén García-Jarana, Milagrosa Ramírez-del Solar, Lucio Cardozo-Filho, Juan R. Portela-Miguélez, and José M. Abelleira-Pereira. 2026. "Hydrothermal Treatment with Different Solvents for Composite Recycling and Valorization Under Subcritical and Supercritical Conditions" Polymers 18, no. 1: 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010089

APA StyleVázquez-Fernández, J. M., García-Jarana, B., Ramírez-del Solar, M., Cardozo-Filho, L., Portela-Miguélez, J. R., & Abelleira-Pereira, J. M. (2026). Hydrothermal Treatment with Different Solvents for Composite Recycling and Valorization Under Subcritical and Supercritical Conditions. Polymers, 18(1), 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010089