Dynamic Mechanical Analysis, Morphology, Physico-Mechanical, and Performance Properties of EPDM/NBR Rubber Blends Containing Chlorosulfonated Polyethylene as a Compatibilizer

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of Rubber Blends

2.3. Preparation of the Samples

2.4. Methods

2.4.1. Viscosity Measurement

2.4.2. Curing Characteristics

2.4.3. Determination of the Crosslink Density

2.4.4. Dynamic Mechanical Properties

2.4.5. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

2.4.6. Physico-Mechanical Properties

2.4.7. Performance Properties

3. Results and Discussions

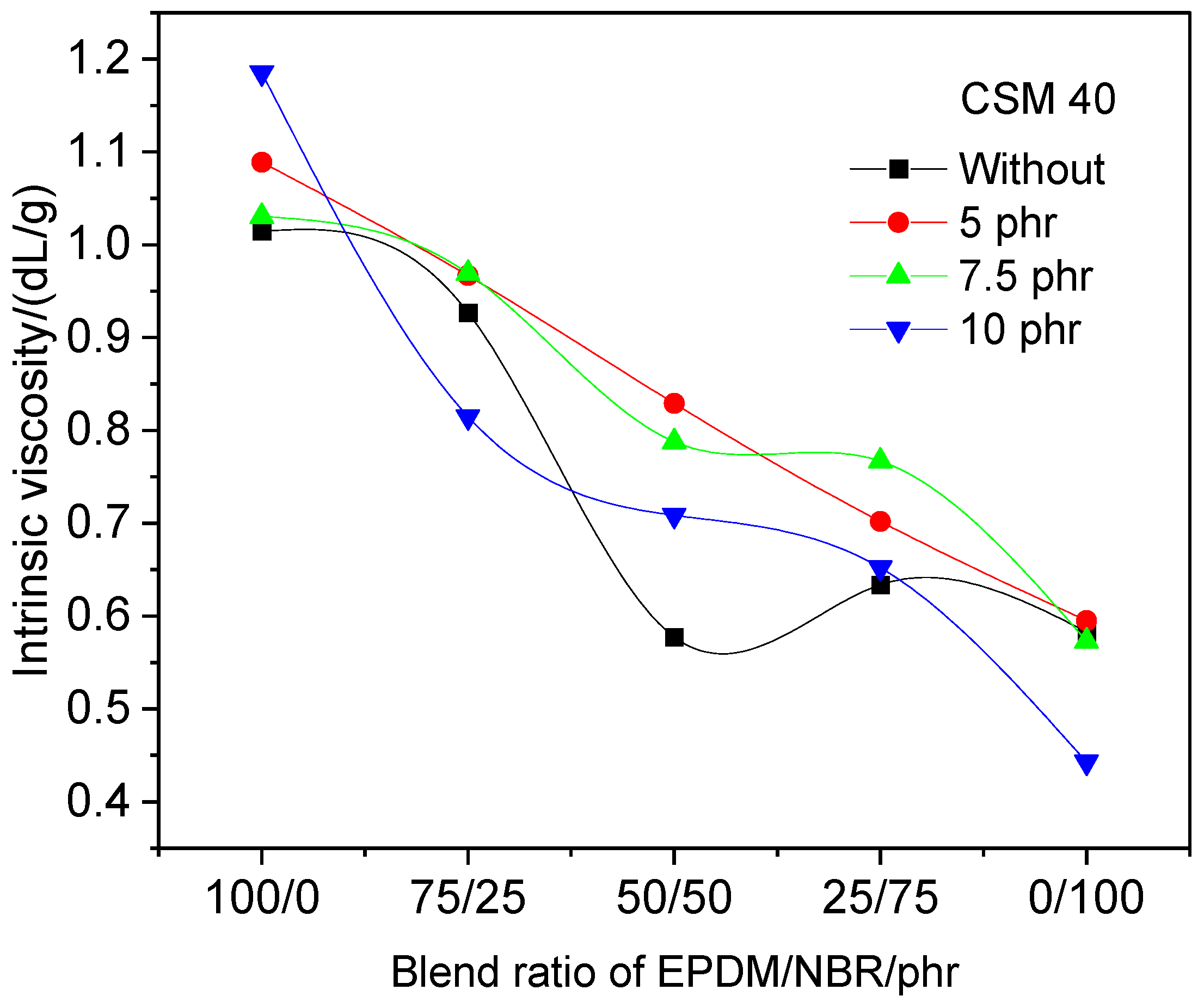

3.1. Determining the Optimal Amount of Compatibilizer and Rubber Compound Options

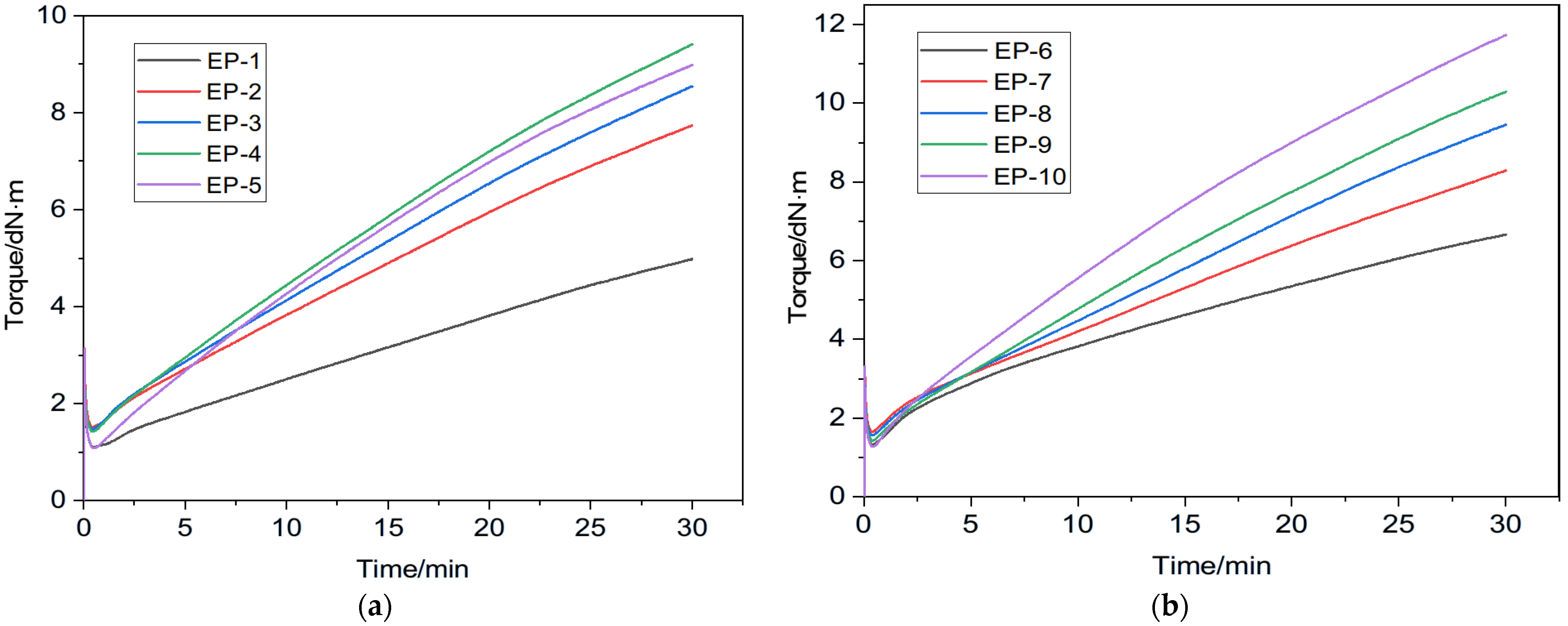

3.2. Curing (Rheometric) Properties and Crosslinking Density

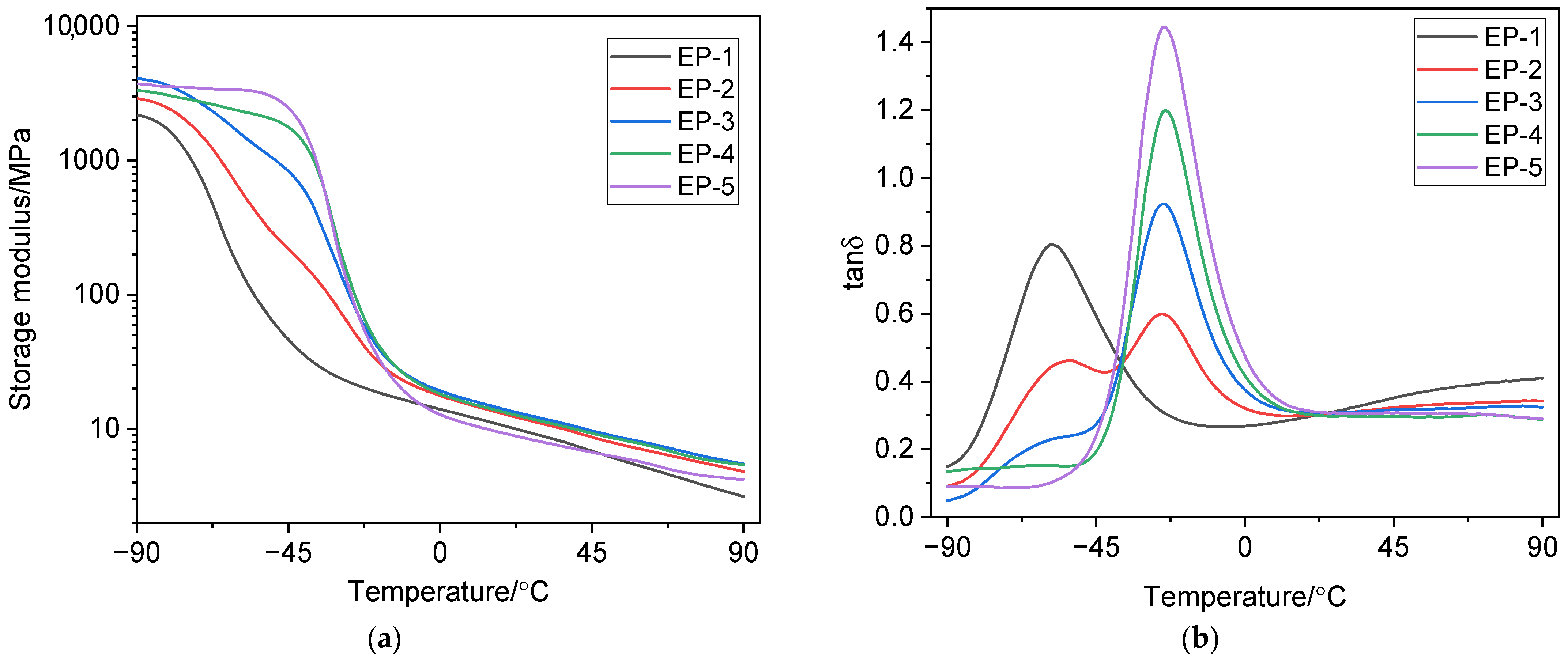

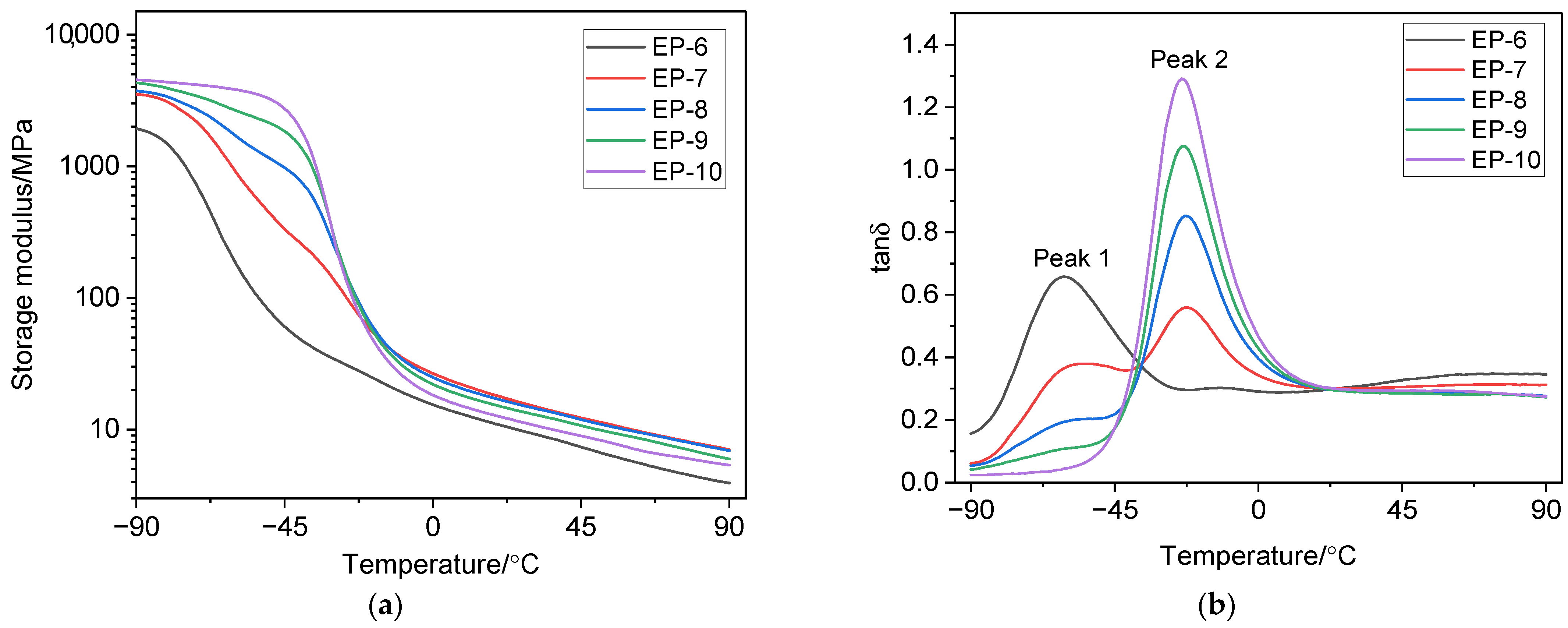

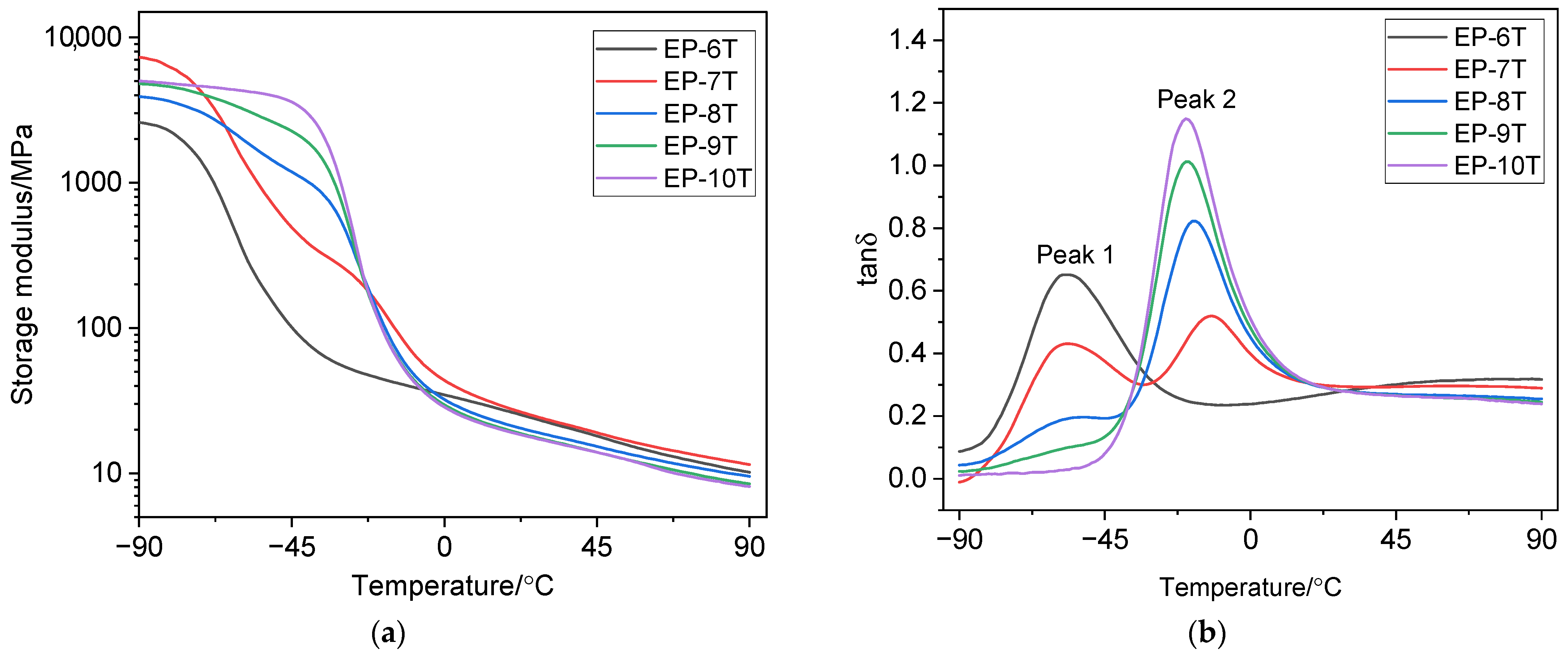

3.3. Dynamic Mechanical Properties

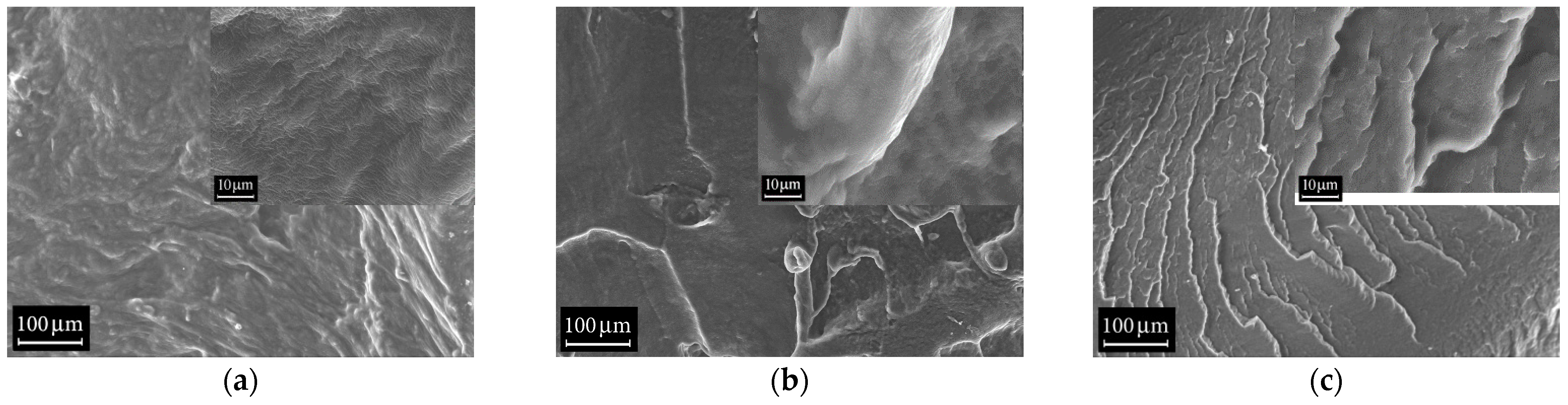

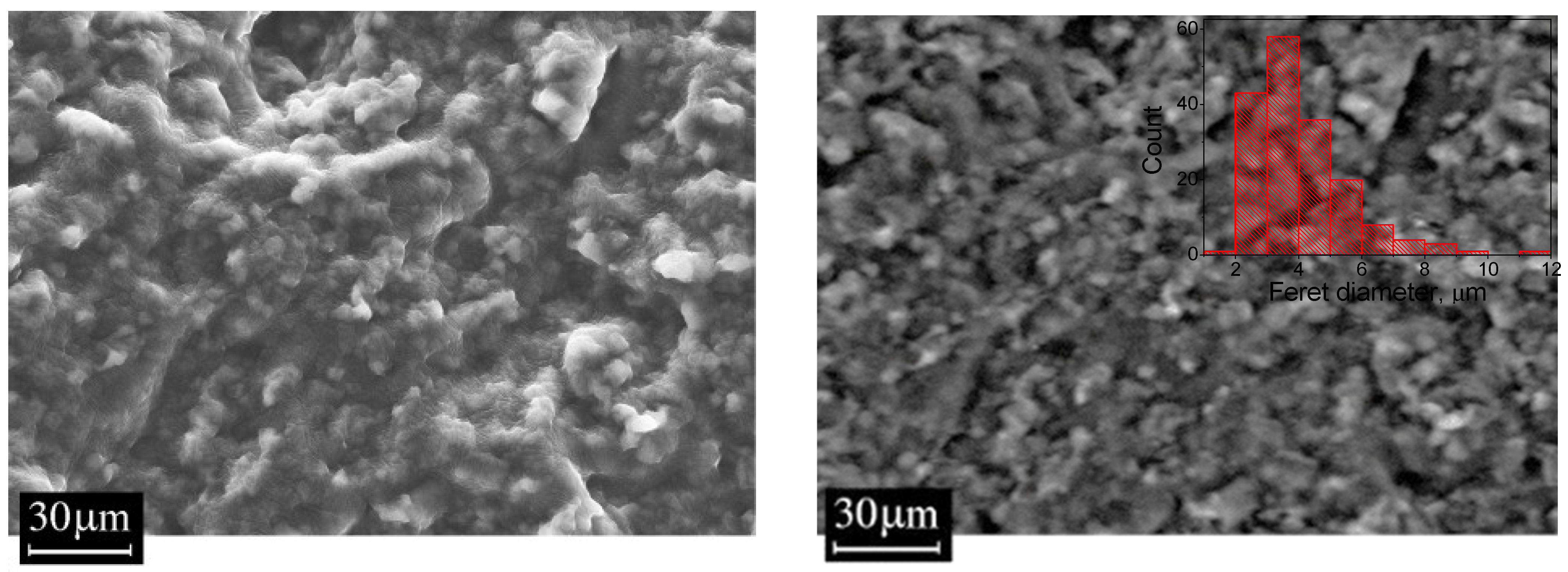

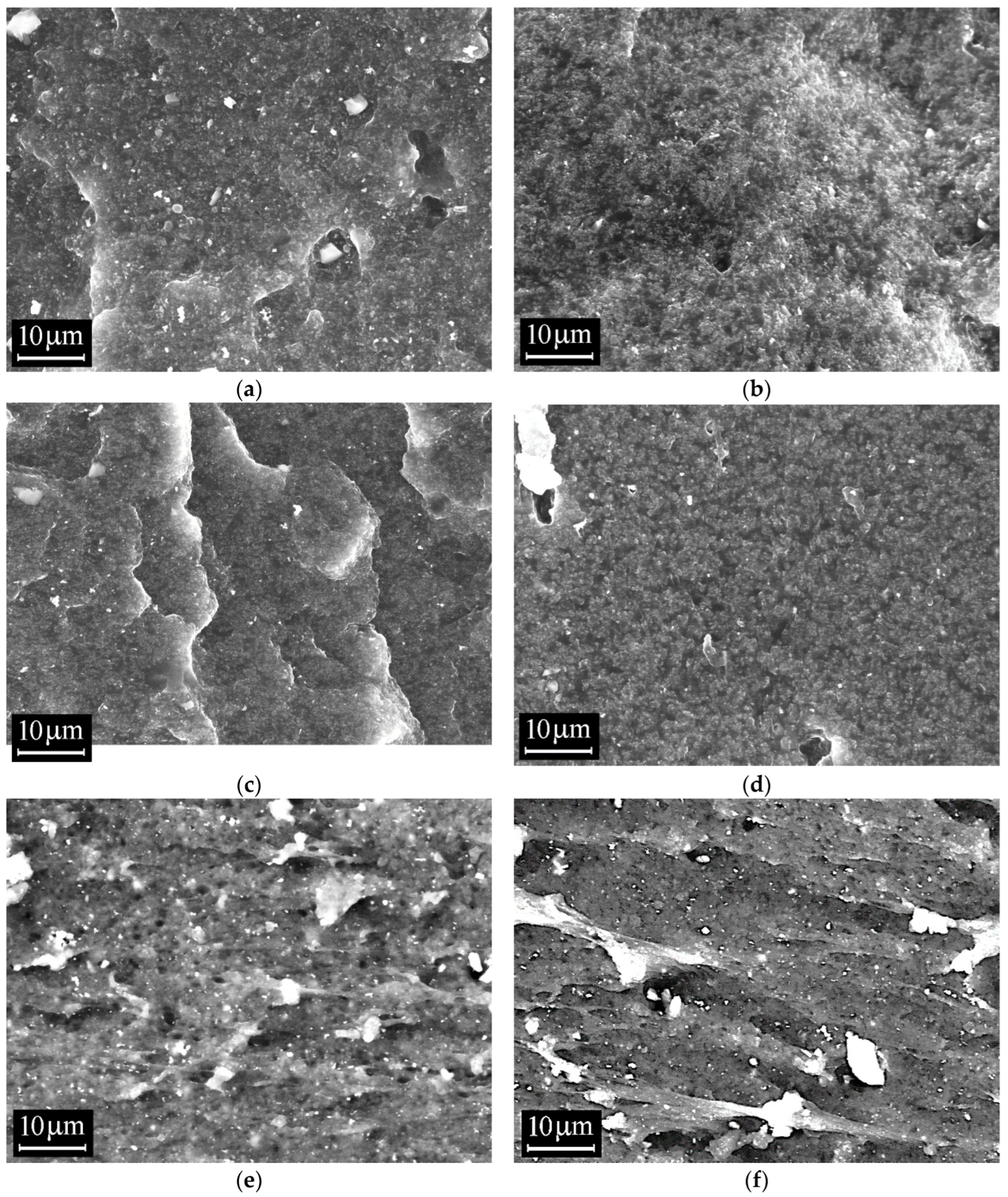

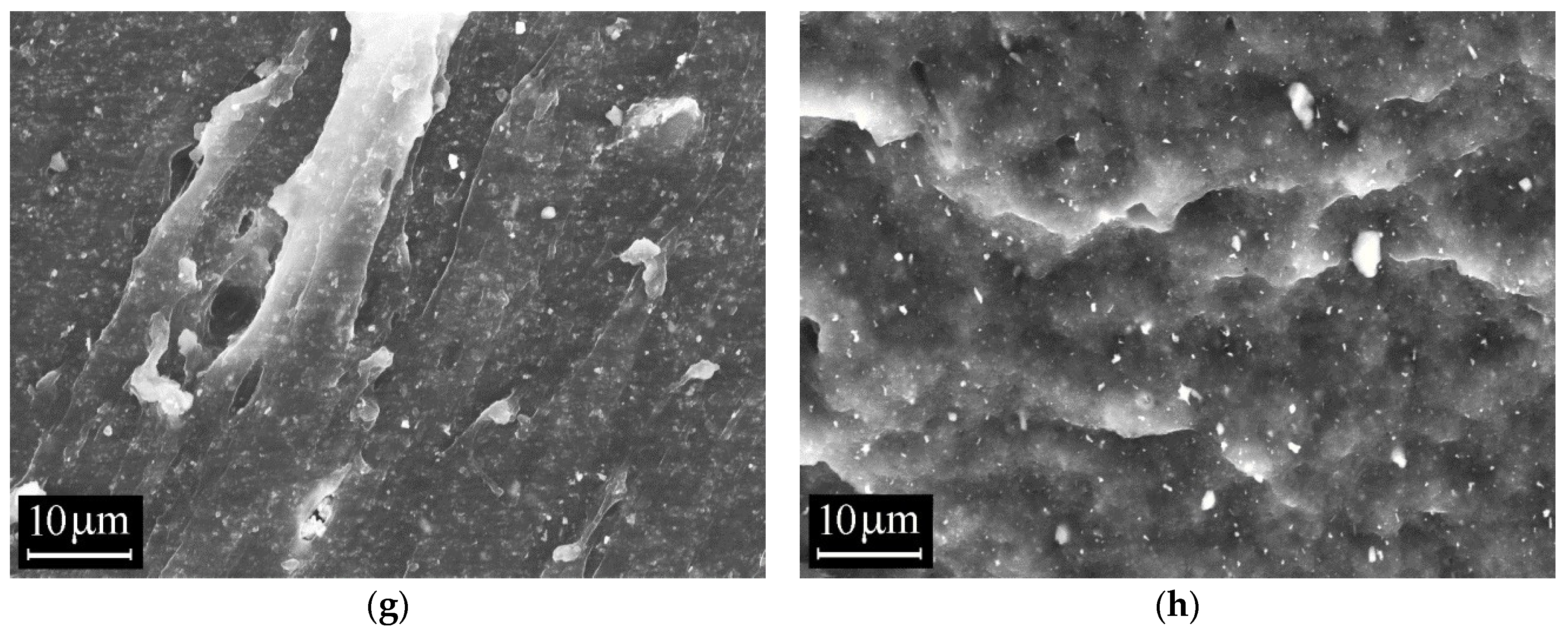

3.4. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

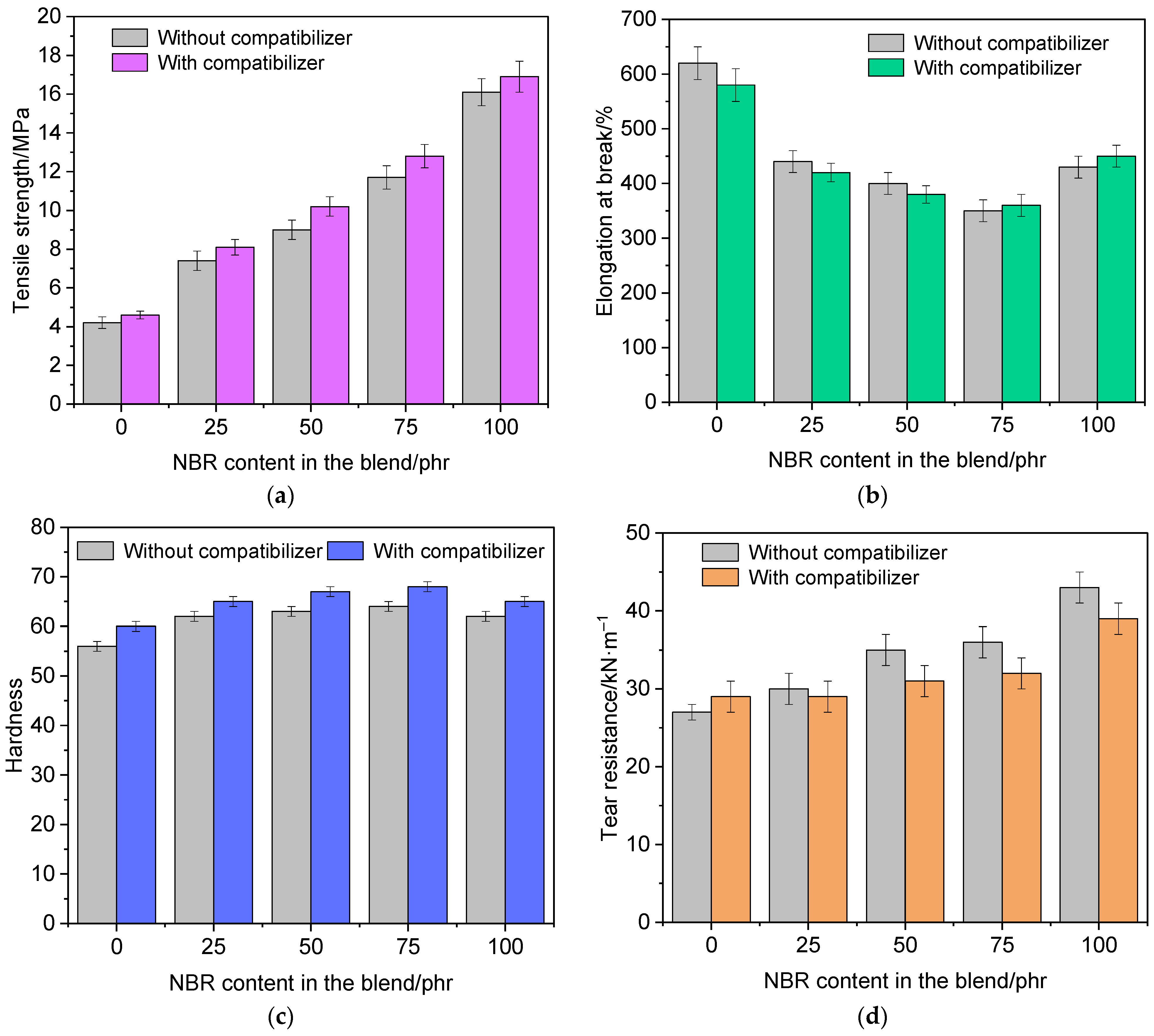

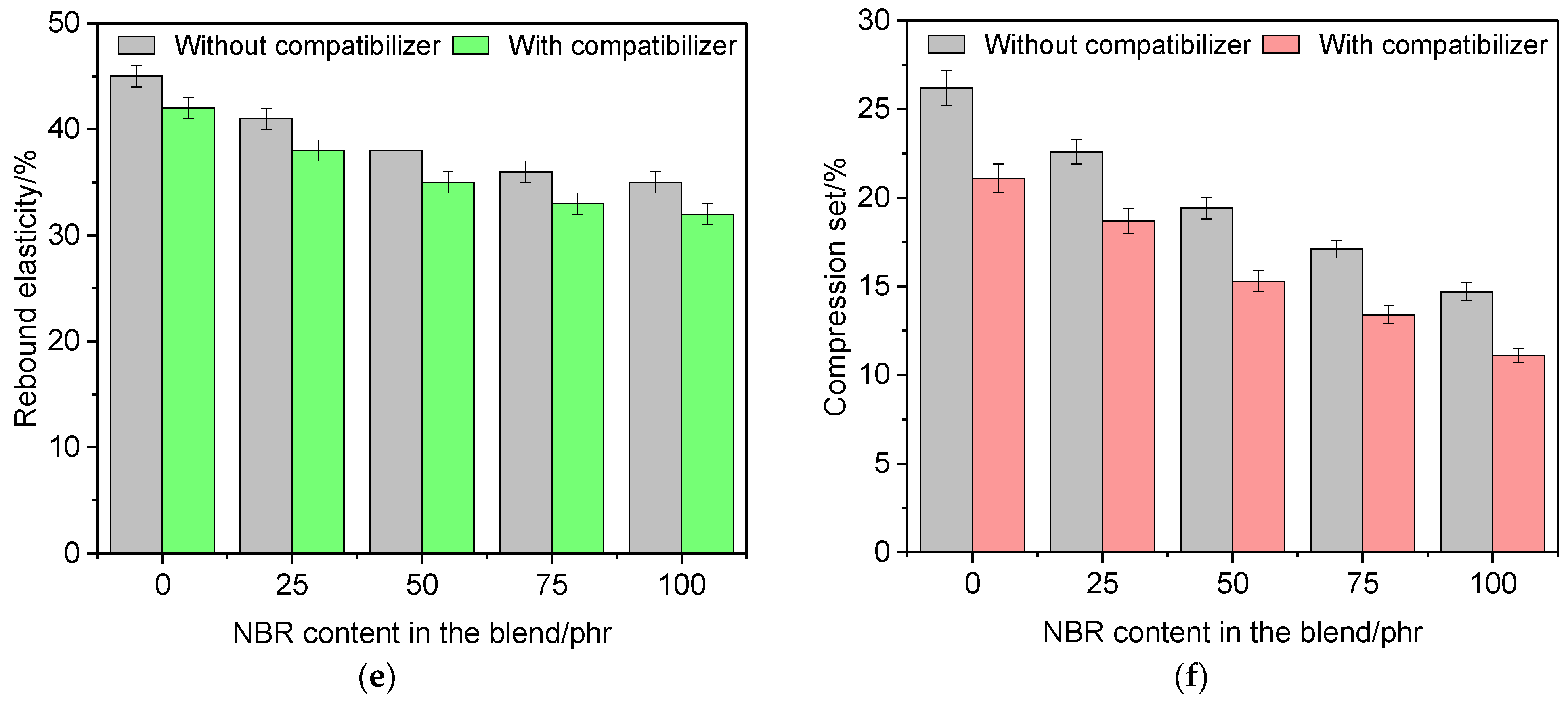

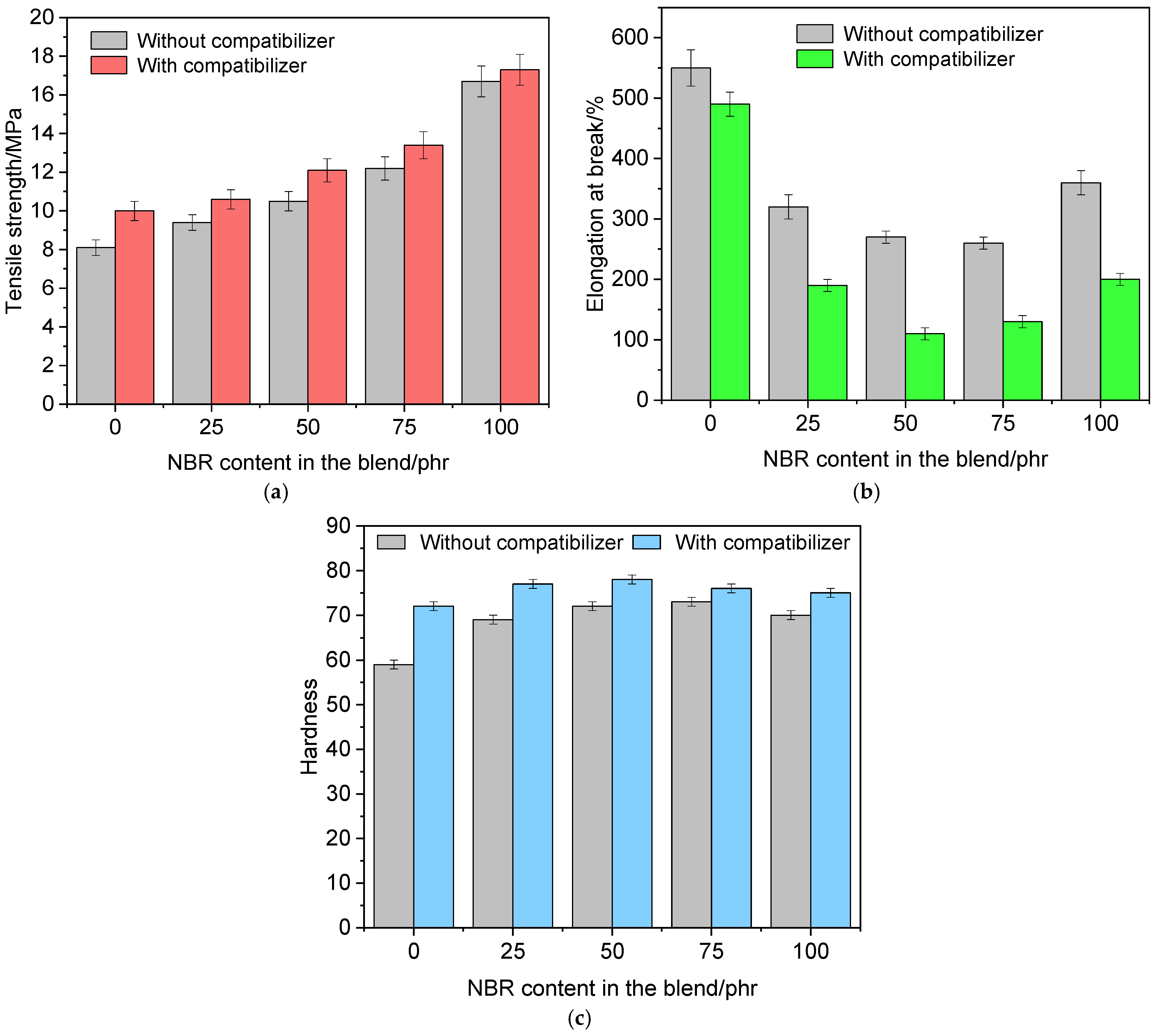

3.5. Physico-Mechanical Properties

3.6. Performance Properties

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eslami, Z.; Mirzapour, M. Compatibilizing Effect and Reinforcing Efficiency of Nanosilica on Ethylene-propylene Diene Monomer/Chloroprene Rubber Blends. Polym. Compos. 2021, 42, 1809–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surya, I.; Muniyadi, M.; Ismail, H. A Review on Clay-reinforced Ethylene Propylene Diene Terpolymer Composites. Polym. Compos. 2021, 42, 1698–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, N.L.; Hiranobe, C.T.; Cardim, H.P.; Dognani, G.; Sanchez, J.C.; Carvalho, J.A.J.; Torres, G.B.; Paim, L.L.; Pinto, L.F.; Cardim, G.P.; et al. A Review of EPDM (Ethylene Propylene Diene Monomer) Rubber-Based Nanocomposites: Properties and Progress. Polymers 2024, 16, 1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athawale, A.A.; Joshi, A.M. Electronic Applications of Ethylene Propylene Diene Monomer Rubber and Its Composites. In Flexible and Stretchable Electronic Composites; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 305–333. [Google Scholar]

- Samaržija-Jovanović, S.; Jovanović, V.; Marković, G.; Marinović-Cincović, M.; Budinski-Simendić, J.; Janković, B. Ethylene–Propylene–Diene Rubber-Based Nanoblends: Preparation, Characterization and Applications. In Rubber Nano Blends; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 281–349. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Ding, Y.; Zhao, S. Effects of Co-Agents on the Properties of Peroxide-Cured Ethylene-Propylene Diene Rubber (EPDM). J. Macromol. Sci. Part B 2016, 55, 433–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, G.; Zanchin, G.; Di Girolamo, R.; De Stefano, F.; Lorber, C.; De Rosa, C.; Ricci, G.; Bertini, F. Semibatch Terpolymerization of Ethylene, Propylene, and 5-Ethylidene-2-Norbornene: Heterogeneous High-Ethylene EPDM Thermoplastic Elastomers. Macromolecules 2020, 53, 5881–5894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, T.; Lu, Y.; Tang, Y.; Qiao, J.; Tian, M. The Morphology and Property of Ultra-fine Full-vulcanized Acrylonitrile Butadiene Rubber Particles/EPDM Blends. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2006, 100, 3673–3679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.P.; Prabhakaran, G.; Vishvanathperumal, S. Influence of Modified Nanosilica on the Performance of NR/EPDM Blends: Cure Characteristics, Mechanical Properties and Swelling Resistance. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2024, 34, 3420–3442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, T.M.; Kumaran, M.G.; Unnikrishnan, G.; Kunchandy, S. Ageing Studies of Ethylene Propylene Diene Monomer Rubber/Styrene Butadiene Rubber Blends: Effects of Heat, Ozone, Gamma Radiation, and Water. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2008, 107, 2923–2929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizhani, H.; Katbab, A.A.; Lopez-Hernandez, E.; Miranda, J.M.; Lopez-Manchado, M.A.; Verdejo, R. Preparation and Characterization of Highly Elastic Foams with Enhanced Electromagnetic Wave Absorption Based on Ethylene-Propylene-Diene-Monomer Rubber Filled with Barium Titanate/Multiwall Carbon Nanotube Hybrid. Polymers 2020, 12, 2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; He, J.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, T. A Nitrile Functionalized Graphene Filled Ethylene Propylene Diene Terpolymer Rubber Composites with Improved Heat Resistance. Compos. Part B Eng. 2018, 134, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, Z.; Ye, L. Construction of Sacrificial Bonds and Hybrid Networks in EPDM Rubber towards Mechanical Performance Enhancement. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 484, 616–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoreishi, A.; Koosha, M.; Nasirizadeh, N. Modification of Bitumen by EPDM Blended with Hybrid Nanoparticles: Physical, Thermal, and Rheological Properties. J. Thermoplast. Compos. Mater. 2020, 33, 343–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, A.; Roy, D. Study on Abrasive Wear Pattern of Ethylene Propylene Dyne Monomer (EPDM) Rubber Compound. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 78, 476–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spalding, M.A.; Chatterjee, A.M. (Eds.) Handbook of Industrial Polyethylene and Technology; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; ISBN 9781119159766. [Google Scholar]

- Movahed, S.O.; Ansarifar, A.; Mirzaie, F. Effect of Various Efficient Vulcanization Cure Systems on the Compression Set of a Nitrile Rubber Filled with Different Fillers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2015, 132, 41512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Su, D.; Cai, W.; Pehlken, A.; Zhang, G.; Wang, A.; Xiao, J. Influence of Material Selection and Product Design on Automotive Vehicle Recyclability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Movahed, S.O.; Ansarifar, A.; Estagy, S. Review of the reclaiming of rubber waste and recent work on the recycling of ethylene–propylene–diene rubber waste. Rubber Chem. Technol. 2016, 89, 54–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.; Sahu, P.; Oh, J.S. Physical Properties of Slide-Ring Material Reinforced Ethylene Propylene Diene Rubber Composites. Polymers 2022, 14, 2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Toksha, B.; Patel, B.; Rushiya, Y.; Das, P.; Rahaman, M. Recent Developments and Research Avenues for Polymers in Electric Vehicles. Chem. Rec. 2022, 22, e202200186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, J.; Sahoo, S.; Mohanty, S.; Nayak, S.K. Progress of Novel Techniques for Lightweight Automobile Applications through Innovative Eco-Friendly Composite Materials: A Review. J. Thermoplast. Compos. Mater. 2020, 33, 978–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, K.; Debnath, S.C.; Pongwisuthiruchte, A.; Potiyaraj, P. Recent Advances of Natural Fibers Based Green Rubber Composites: Properties, Current Status, and Future Perspectives. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2021, 138, 50866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulewicz, M.; Pietrzak, A. Properties and Structure of Concretes Doped with Production Waste of Thermoplastic Elastomers from the Production of Car Floor Mats. Materials 2021, 14, 872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohd Makhtar, N.S.; Hamdan, N.; Rodhi, M.N.M.; Musa, M.; Ku Hamid, K.H. The Potential Use of Tacca Leontopetaloides as Green Material in Manufacturing Automotive Part. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2014, 575, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Chen, Z.; Pang, C.; He, S.; Lin, J. Study on Thermal-Oxidative Aging Properties of Ethylene-Propylene-Diene Monomer Composites Filled with Silica and Carbon Nanotubes. Polymers 2022, 14, 1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rana, A.S.; Vamshi, M.K.; Naresh, K.; Velmurugan, R.; Sarathi, R. Mechanical, Thermal, Electrical and Crystallographic Behaviour of EPDM Rubber/Clay Nanocomposites for out-Door Insulation Applications. Adv. Mater. Process. Technol. 2020, 6, 54–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y. Electrical Breakdown Mechanism of ENB-EPDM Cable Insulation Based on Density Functional Theory. Polymers 2023, 15, 1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, M.T.; Butt, F.T.; Phung, B.T.; Yeoh, G.H.; Yasin, G.; Akram, S.; Bhutta, M.S.; Hussain, S.; Nguyen, T.A. Simulation and Experimental Investigation on Carbonized Tracking Failure of EPDM/BN-Based Electrical Insulation. Polymers 2020, 12, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, A.B.; Chatterjee, T.; Naskar, K. Automotive Applications of Thermoplastic Vulcanizates. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2020, 137, 49181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Chen, Q.; Song, P.; Gong, X.; Chen, J.; Zhao, Y. Performance of Thermal-Oxidative Aging on the Structure and Properties of Ethylene Propylene Diene Monomer (EPDM) Vulcanizates. Polymers 2023, 15, 2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosa, M.; Gobara, M.; Kotb, M.M.; Fouda, H.; Elbasuney, S. Nano-Hydroxyapatite Filled EPDM Nanocomposite: Towards Green Elastomeric Thermal Insulating Coating with Superior Mechanical, Thermal, and Ablation Properties. J. Energ. Mater. 2025, 43, 693–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Guchhait, P.K.; Singha, N.K.; Chaki, T.K. Carbon nanofiber composite with EPDM and polyimide for high-temperature insulation. Rubber Chem. Technol. 2014, 87, 593–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Chen, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, T.; Jiang, Y. Sound Absorption Behavior of Polyurethane Foam Composites with Different Ethylene Propylene Diene Monomer Particles. Arch. Acoust. 2018, 43, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyssa, H.M.; Afifi, M.; Moustafa, H. Improvement of the Acoustic and Mechanical Properties of Sponge Ethylene Propylene Diene Rubber/Carbon Nanotube Composites Crosslinked by Subsequent Sulfur and Electron Beam Irradiation. Polym. Int. 2023, 72, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.-N.; Shen, S.-L.; Zhou, A.-N.; Xu, Y.-S. Experimental Evaluation of Aging Characteristics of EPDM as a Sealant for Undersea Shield Tunnels. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2020, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamsaengsung, W.; Sombatsompop, N. Use of Expanded-EPDM as Protecting Layer for Moderation of Photo-degradation in Wood/NR Composite for Roofing Applications. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2010, 117, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragaglia, M.; Paleari, L.; Nanni, F. Ground Tire Rubber and Coffee Silverskin as Sustainable Fillers in EPDM Compounds for Rubber-to-steel Bonded Systems in Roofing Applications. Polym. Compos. 2024, 45, 8861–8875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiridonov, I.S.; Ushmarin, N.F.; Egorov, E.N.; Sandalov, S.I.; Kol’tsov, N.I. Influence technological additives on properties of rubber based on butadiene-nitrile caoutchuc. Izv. Vyss. Uchebnykh Zaved. Khimiya Khimicheskaya Tekhnologiya 2017, 60, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.Y.; Zhang, W.F. Environmental Factors on Aging of Nitrile Butadiene Rubber (NBR)—A Review. Adv. Mater. Res. 2014, 1033–1034, 987–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, C.; He, A. Accelerated Aging Behavior and Degradation Mechanism of Nitrile Rubber in Thermal Air and Hydraulic Oil Environments. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2023, 63, 2218–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.Y.; Kim, G.H.; Nam, G.M.; Kang, D.G.; Seo, K.H. Oil Resistance and Low-temperature Characteristics of Plasticized Nitrile Butadiene Rubber Compounds. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2019, 136, 47851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, S.; Li, T.; Chen, S.; Huang, X.; Cai, S.; He, X. Effect of Multi-Modified Layered Double Hydroxide on Aging Resistance of Nitrile-Butadiene Rubber. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2020, 195, 108193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beknazarov, K.; Tokpayev, R.; Nakyp, A.; Karaseva, Y.; Cherezova, E.; El Fray, M.; Volfson, S.; Nauryzbayev, M. Influence of Kazakhstan’s Shungites on the Physical–Mechanical Properties of Nitrile Butadiene Rubber Composites. Polymers 2024, 16, 3370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherezova, E.; Karaseva, Y.; Nakyp, A.; Nuriev, A.; Islambekuly, B.; Akylbekov, N. Influence of Partially Carboxylated Powdered Lignocellulose from Oat Straw on Technological and Strength Properties of Water-Swelling Rubber. Polymers 2024, 16, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamad Aini, N.A.; Othman, N.; Hussin, M.H.; Sahakaro, K.; Hayeemasae, N. Efficiency of Interaction between Hybrid Fillers Carbon Black/Lignin with Various Rubber-Based Compatibilizer, Epoxidized Natural Rubber, and Liquid Butadiene Rubber in NR/BR Composites: Mechanical, Flexibility and Dynamical Properties. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 185, 115167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lu, Y.; Jin, Z.; Zhang, L. Influence of Interfacial Compatibilizer, Silane Modification, and Filler Hybrid on the Performance of NR/NBR Blends. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2019, 136, 47421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moolsin, S.; Saksayamkul, N.; Na Wichien, A. Natural Rubber Grafted Poly(Methyl Methacrylate) as Compatibilizer in 50/50 Natural Rubber/Nitrile Rubber Blend. J. Elastomers Plast. 2017, 49, 422–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serenko, O.A.; Pryakhina, T.A.; Vasil’ev, V.G.; Buzin, M.I.; Volkov, I.O.; Kotov, V.M.; Muzafarov, A.M. Effect of Reactionary Capable Siloxane Compatibilizer on the Properties of Blends of Ethylene Propylene Diene and Siloxane Rubbers. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2021, 70, 960–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelsalam, A.A.; El-Sabbagh, S.H.; Mohamed, W.S.; Khozami, M.A. Studies on Swelling Behavior, Mechanical and Thermal Properties of Ternary Rubber Blend Composites in the Presence of Compatibilizers. Pigment. Resin. Technol. 2023, 52, 614–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jana, R.N.; Nando, G.B. Compatibilized Blends of Low Density Polyethylene and Poly Dimethyl Siloxane Rubber: Part I: Acid and Alkali Resistance Properties. J. Elastomers Plast. 2002, 34, 349–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, B.; Halasa, A. Compounding and Processing of Rubber/Rubber Blends. In Encyclopedia of Polymer Blends; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 163–206. [Google Scholar]

- Saad, A.L.G.; El-Sabbagh, S. Compatibility Studies on Some Polymer Blend Systems by Electrical and Mechanical Techniques. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2001, 79, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasiadis, S.H. Interfacial Tension in Binary Polymer Blends and the Effects of Copolymers as Emulsifying Agents. In Polymer Thermodynamics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 179–269. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.-H.; Park, S.-Y.; Chung, K.-H.; Jang, K.-S. Phlogopite-Reinforced Natural Rubber (NR)/Ethylene-Propylene-Diene Monomer Rubber (EPDM) Composites with Aminosilane Compatibilizer. Polymers 2021, 13, 2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, K.N.; Setua, D.K.; Mathur, G.N. Determination of the Compatibility of NBR-EPDM Blends by an Ultrasonic Technique, Modulated DSC, Dynamic Mechanical Analysis, and Atomic Force Microscopy. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2005, 45, 1265–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizli, M.J.; Khonakdar, H.A.; Mokhtary, M.; Goodarzi, V. Investigating the Effect of Organoclay Montmorillonite and Rubber Ratio Composition on the Enhancement Compatibility and Properties of Carboxylated Acrylonitrile-Butadiene Rubber/Ethylene-Propylene-Diene Monomer Hybrid Elastomer Nanocomposites. J. Polym. Res. 2019, 26, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botros, S.H.; Tawfic, M.L. Synthesis and Characteristics of MAH-g-EPDM Compatibilized EPDM/NBR Rubber Blends. J. Elastomers Plast. 2006, 38, 349–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobing, S.D. Co-Curing of NR/EPDM Rubber Blends. US4931508A, 5 June 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Flory, P.J.; Rehner, J. Statistical Mechanics of Cross-Linked Polymer Networks I. Rubberlike Elasticity. J. Chem. Phys. 1943, 11, 512–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.Y.; Park, J.W.; Lee, D.Y.; Seo, K.H. Correlation between the Crosslink Characteristics and Mechanical Properties of Natural Rubber Compound via Accelerators and Reinforcement. Polymers 2020, 12, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad Aini, N.; Othman, N.; Hussin, M.; Sahakaro, K.; Hayeemasae, N. Hydroxymethylation-Modified Lignin and Its Effectiveness as a Filler in Rubber Composites. Processes 2019, 7, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongdong, W.; Nakason, C.; Kummerlöwe, C.; Vennemann, N. Influence of Filler from a Renewable Resource and Silane Coupling Agent on the Properties of Epoxidized Natural Rubber Vulcanizates. J. Chem. 2015, 2015, 796459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Vahidifar, A.; Yu, S.; Mekonnen, T.H. Optimization of Silane Modification and Moisture Curing for EPDM toward Improved Physicomechanical Properties. React. Funct. Polym. 2023, 182, 105467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirityi, D.Z.; Pölöskei, K. Thermomechanical Devulcanisation of Ethylene Propylene Diene Monomer (EPDM) Rubber and Its Subsequent Reintegration into Virgin Rubber. Polymers 2021, 13, 1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egorov, E.N.; Salomatina, E.V.; Vassilyev, V.R.; Bannov, A.G.; Sandalov, S.I. Effect of Polynorbornene on Physico-Mechanical, Dynamic, and Dielectric Properties of Vulcanizates Based on Isoprene, α-Methylstyrene-Butadiene, and Nitrile-Butadiene Rubbers for Rail Fasteners Pads. J. Compos. Sci. 2023, 7, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanda, M.; Tripathy, D.K. Physico-Mechanical and Electrical Properties of Conductive Carbon Black Reinforced Chlorosulfonated Polyethylene Vulcanizates. Express Polym. Lett. 2008, 2, 855–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi Ghari, H.; Shakouri, Z. Testing and Evaluation of Microstructure of Organoclay in Chlorosulfunated Polyethylene Nanocomposites by Emphasis on Solvent Transport Properties. J. Vinyl Addit. Technol. 2017, 23, E40–E50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabaei, T.A.; Bagheri, R.; Hesami, M. Comparison of Cure Characteristics and Mechanical Properties of Nano and Micro Silica-filled CSM Elastomers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2015, 132, 42668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzocca, A.J.; Rodríguez Garraza, A.L.; Mansilla, M.A. Evaluation of the Polymer–Solvent Interaction Parameter χ for the System Cured Polybutadiene Rubber and Toluene. Polym. Test. 2010, 29, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botros, S.H.; Tawfic, M.L. Preparation and Characteristics of EPDM/NBR Rubber Blends with BIIR as Compatibilizer. Polym. Plast. Technol. Eng. 2005, 44, 209–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sabbagh, S. Compatibility Study of Natural Rubber and Ethylene–Propylene Diene Rubber Blends. Polym. Test. 2003, 22, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansilla, M.A.; Marzocca, A.J.; Macchi, C.; Somoza, A. Influence of Vulcanization Temperature on the Cure Kinetics and on the Microstructural Properties in Natural Rubber/Styrene-Butadiene Rubber Blends Prepared by Solution Mixing. Eur. Polym. J. 2015, 69, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egorov, E.N.; Sandalov, S.I.; Koltsov, N.I. Investigation of the influence of polyisobutylenes on the properties of seawater-resistant rubber. Chem. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 33, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egorov, E.N.; Sandalov, S.I.; Kol’tsov, N.I. Influence of basalt fibres on the physical-mechanical, performance and dynamic properties of rubber for rail pads. Chem. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 31, 10–2023479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egorov, E.N.; Ushmarin, N.F.; Salomatina, E.V.; Matyunin, A.N. The effect of polyisobutylene on physical-mechanical, operational, dielectric and dynamic properties of rubber for laying rail fasteners. ChemChemTech 2022, 65, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egorov, E.N.; Ushmarin, N.F.; Sandalov, S.I.; Kol’tsov, N.I. Studying the Effect of Trans-Polynorbornene on the Properties of a Rubber Mixture for Rail Fastener Pads. Inorg. Mater. Appl. Res. 2022, 13, 1019–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ushmarin, N.F.; Egorov, E.N.; Sandalov, S.I.; Kol’tsov, N.I. Influence of Polymeric Microspheres on Rubber Properties for Coating Metal Surfaces. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2023, 93, 734–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ushmarin, N.F.; Egorov, E.N.; Grigor’ev, V.S.; Sandalov, S.I.; Kol’tsov, N.I. Influence of Chlorobutyl Caoutchouc on the Dynamic Properties of a Rubber Based on General-Purpose Caoutchoucs. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2022, 92, 1862–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, T.M.; Kumaran, M.G.; Unnikrishnan, G.; Pillai, V.B. Dynamic Mechanical Analysis of Ethylene–Propylene–Diene Monomer Rubber and Styrene–Butadiene Rubber Blends. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2009, 112, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livanova, N.M.; Popov, A.A. The Role of Defective Structures of Butadiene-Nitrile Elastomers in Interphase Interactions in Mixtures with Ethylene-Propylene-Diene Rubbers. Russ. J. Phys. Chem. B 2017, 11, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livanova, N.M.; Popov, A.A. Intra- and Interphase Crosslinking in Composites of Nitrile-Butadiene Rubber with Polyvinyl Chloride and Their Ozone Resistance. Russ. J. Phys. Chem. B 2019, 13, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korovina, Y.V.; Shcherbina, E.I.; Dolinskaya, R.M.; Leizeronok, M.E. Peroxide Vulcanisation of Hydrogenated Butadiene–Acrylonitrile Rubber. Int. Polym. Sci. Technol. 2008, 35, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Rubbers and Ingredients | Rubber Compound Options (phr *) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EP-1 | EP-2 | EP-3 | EP-4 | EP-5 | EP-6 | EP-7 | EP-8 | EP-9 | EP-10 | |

| EPDM S 501A | 100.0 | 75.0 | 50.0 | 25.0 | 0 | 100.0 | 75.0 | 50.0 | 25.0 | 0 |

| NBR 2645 | 0 | 25.0 | 50.0 | 75.0 | 100.0 | 0 | 25.0 | 50.0 | 75.0 | 100.0 |

| CSM 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 |

| Luperox F 40P E | 6.0 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 6.0 |

| Triallyl cyanurate TAC 70 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| ZnO | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 |

| Stearic acid | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Antioxidant 445 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| Nickel dibutyldithiocarbamate | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Wax ZV-P | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Carbon black P 324 | 30.0 | 30.0 | 30.0 | 30.0 | 30.0 | 30.0 | 30.0 | 30.0 | 30.0 | 30.0 |

| Carbon black P 514 | 15.0 | 15.0 | 15.0 | 15.0 | 15.0 | 15.0 | 15.0 | 15.0 | 15.0 | 15.0 |

| Naphthenic oil NMR-12 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 |

| Total weight | 168.5 | 168.5 | 168.5 | 168.5 | 168.5 | 173.5 | 173.5 | 173.5 | 173.5 | 173.5 |

| Characteristics | Samples | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EP-1 | EP-2 | EP-3 | EP-4 | EP-5 | EP-6 | EP-7 | EP-8 | EP-9 | EP-10 | |

| ML, dN·m | 1.54 | 1.90 | 1.81 | 1.72 | 1.35 | 1.82 | 2.08 | 1.92 | 1.72 | 1.59 |

| MH, dN·m | 5.16 | 7.85 | 8.64 | 9.47 | 9.03 | 6.84 | 8.42 | 9.53 | 10.34 | 11.78 |

| ∆M, dN·m | 3.62 | 5.95 | 6.83 | 7.75 | 7.68 | 5.02 | 6.34 | 7.61 | 8.62 | 10.19 |

| ts2, min | 14.55 | 8.54 | 7.34 | 6.53 | 6.21 | 7.05 | 7.39 | 6.49 | 5.80 | 4.27 |

| t90, min | 26.32 | 26.19 | 26.17 | 26.08 | 25.59 | 25.41 | 26.40 | 26.18 | 26.14 | 25.91 |

| Characteristics | Samples | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EP-1 | EP-2 | EP-3 | EP-4 | EP-5 | EP-6 | EP-7 | EP-8 | EP-9 | EP-10 | |

| , g/cm3 | 0.860 | 0.885 | 0.910 | 0.935 | 0.960 | 0.872 | 0.896 | 0.920 | 0.944 | 0.968 |

| χ | 0.496 | 0.476 | 0.455 | 0.435 | 0.414 | 0.491 | 0.472 | 0.452 | 0.433 | 0.413 |

| νr | 0.190 ± 0.001 | 0.289 ± 0.001 | 0.308 ± 0.001 | 0.318 ± 0.001 | 0.313 ± 0.001 | 0.215 ± 0.002 | 0.310 ± 0.001 | 0.330 ± 0.001 | 0.340 ± 0.001 | 0.339 ± 0.002 |

| Mc × 10−3, g/mol | 27.632 ± 0.463 | 3.942 ± 0.040 | 2.965 ± 0.027 | 2.509 ± 0.022 | 2.438 ± 0.021 | 10.415 ± 0.281 | 3.164 ± 0.030 | 2.420 ± 0.021 | 2.080 ± 0.017 | 1.972 ± 0.032 |

| νc × 104, mol/cm3 | 0.181 ± 0.003 | 1.268 ± 0.013 | 1.686 ± 0.015 | 1.993 ± 0.017 | 2.051 ± 0.018 | 0.480 ± 0.013 | 1.580 ± 0.015 | 2.066 ± 0.018 | 2.404 ± 0.020 | 2.535 ± 0.040 |

| Samples | Peak 1 | Peak 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tg, °C | tanδmax | Tg, °C | tanδmax | |

| EP-1 | −58.0 | 0.803 | – | – |

| EP-2 | −53.0 | 0.462 | −25.0 | 0.599 |

| EP-3 | shoulder | −25.0 | 0.924 | |

| EP-4 | – | – | −24.0 | 1.200 |

| EP-5 | – | – | −24.0 | 1.445 |

| EP-6 | −61.0 | 0.658 | – | – |

| EP-7 | −55.0 | 0.380 | −23.0 | 0.559 |

| EP-8 | shoulder | −23.0 | 0.853 | |

| EP-9 | – | – | −24.0 | 1.075 |

| EP-10 | – | – | −24.0 | 1.291 |

| Samples * | Peak 1 | Peak 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tg, °C | tanδmax | Tg, °C | tanδmax | |

| EP-6T | −57.0 | 0.652 | – | – |

| EP-7T | −56.0 | 0.431 | −12.0 | 0.520 |

| EP-8T | shoulder | −18.0 | 0.822 | |

| EP-9T | – | – | −20.0 | 1.012 |

| EP-10T | – | – | −20.0 | 1.149 |

| Characteristics | Samples | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EP-1 | EP-2 | EP-3 | EP-4 | EP-5 | EP-6 | EP-7 | EP-8 | EP-9 | EP-10 | |

| Changes in the properties of vulcanizates after aging in air at 100 °C for 24 h | ||||||||||

| Δfp, % | + (14.1 ± 0.7) | + (13.2 ± 0.6) | + (12.8 ± 0.6) | + (12.1 ± 0.6) | + (11.7 ± 0.5) | + (17.2 ± 0.9) | + (16.1 ± 0.8) | + (11.6 ± 0.6) | + (10.0 ± 0.5) | + (10.8 ± 0.5) |

| Δεp, % | + (16.1 ± 0.8) | + (15.0 ± 0.7) | + (12.5 ± 0.6) | − (11.4 ± 0.6) | − (15.3 ± 0.7) | + (14.3 ± 0.7) | + 13.9 ± 0.7 | + (12.7 ± 0.6) | - (8.3 ± 0.4) | − (12.2 ± 0.6) |

| ΔH, Shore A units | −(2 ± 1) | +(1 ± 1) | +(1 ± 1) | −(1 ± 1) | −(1 ± 1) | +(3 ± 1) | +(3 ± 1) | +(3 ± 1) | +(1 ± 1) | +(2 ± 1) |

| Change in the mass of vulcanizates after exposure to aggressive environments at 23 °C for 24 h | ||||||||||

| Δm (oil I-20A), % | 32.04 ± 0.34 | 17.33 ± 0.31 | 9.65 ± 0.23 | 2.55 ± 0.12 | 0.18 ± 0.01 | 26.83 ± 0.59 | 16.42 ± 0.61 | 9.47 ± 0.13 | 2.48 ± 0.11 | 0.14 ± 0.01 |

| Δm (SZhR-1), % | 8.75 ± 0.33 | 5.96 ± 0.11 | 3.41 ± 0.12 | 0.72 ± 0.03 | −(0.06 ± 0.01) | 8.46 ± 0.19 | 5.68 ± 0.09 | 3.32 ± 0.10 | 0.65 ± 0.02 | −(0.04 ± 0.01) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Egorov, E.; Turmanov, R.; Zhapparbergenov, R.; Oryngaliyev, A.; Akylbekov, N.; Appazov, N.; Loshachenko, A.; Glukhoedov, N.; Nakyp, A.; Semenova, N. Dynamic Mechanical Analysis, Morphology, Physico-Mechanical, and Performance Properties of EPDM/NBR Rubber Blends Containing Chlorosulfonated Polyethylene as a Compatibilizer. Polymers 2026, 18, 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010103

Egorov E, Turmanov R, Zhapparbergenov R, Oryngaliyev A, Akylbekov N, Appazov N, Loshachenko A, Glukhoedov N, Nakyp A, Semenova N. Dynamic Mechanical Analysis, Morphology, Physico-Mechanical, and Performance Properties of EPDM/NBR Rubber Blends Containing Chlorosulfonated Polyethylene as a Compatibilizer. Polymers. 2026; 18(1):103. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010103

Chicago/Turabian StyleEgorov, Evgeniy, Rakhymzhan Turmanov, Rakhmetulla Zhapparbergenov, Aslan Oryngaliyev, Nurgali Akylbekov, Nurbol Appazov, Anton Loshachenko, Nikita Glukhoedov, Abdirakym Nakyp, and Nadezhda Semenova. 2026. "Dynamic Mechanical Analysis, Morphology, Physico-Mechanical, and Performance Properties of EPDM/NBR Rubber Blends Containing Chlorosulfonated Polyethylene as a Compatibilizer" Polymers 18, no. 1: 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010103

APA StyleEgorov, E., Turmanov, R., Zhapparbergenov, R., Oryngaliyev, A., Akylbekov, N., Appazov, N., Loshachenko, A., Glukhoedov, N., Nakyp, A., & Semenova, N. (2026). Dynamic Mechanical Analysis, Morphology, Physico-Mechanical, and Performance Properties of EPDM/NBR Rubber Blends Containing Chlorosulfonated Polyethylene as a Compatibilizer. Polymers, 18(1), 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010103