Elastic Composites Containing Carbonous Fillers Functionalized by Ionic Liquid: Viscoelastic Properties

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

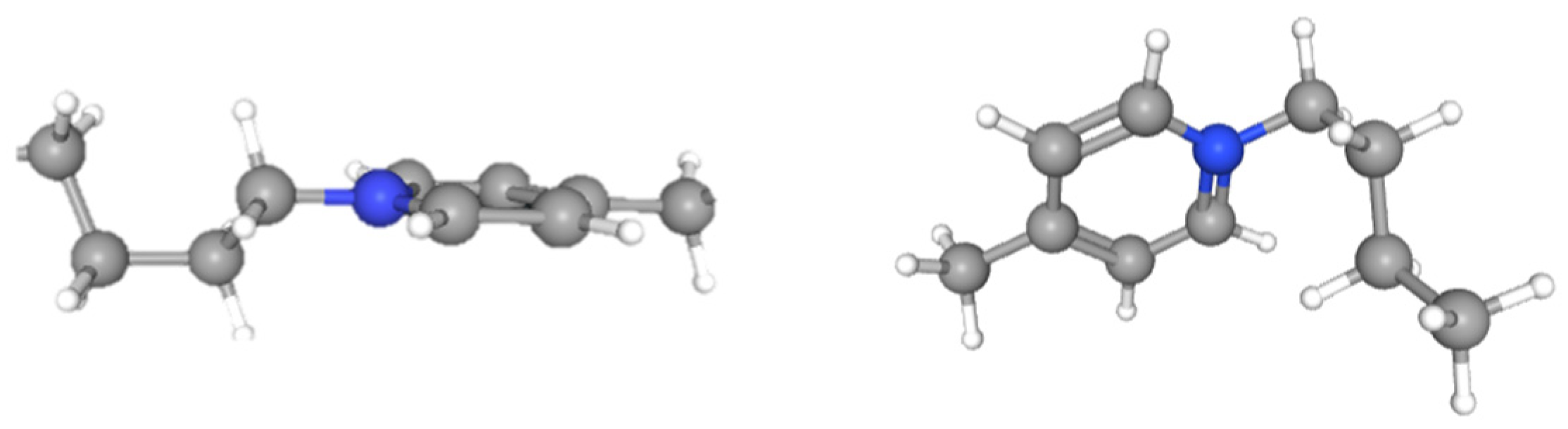

2.1. Materials

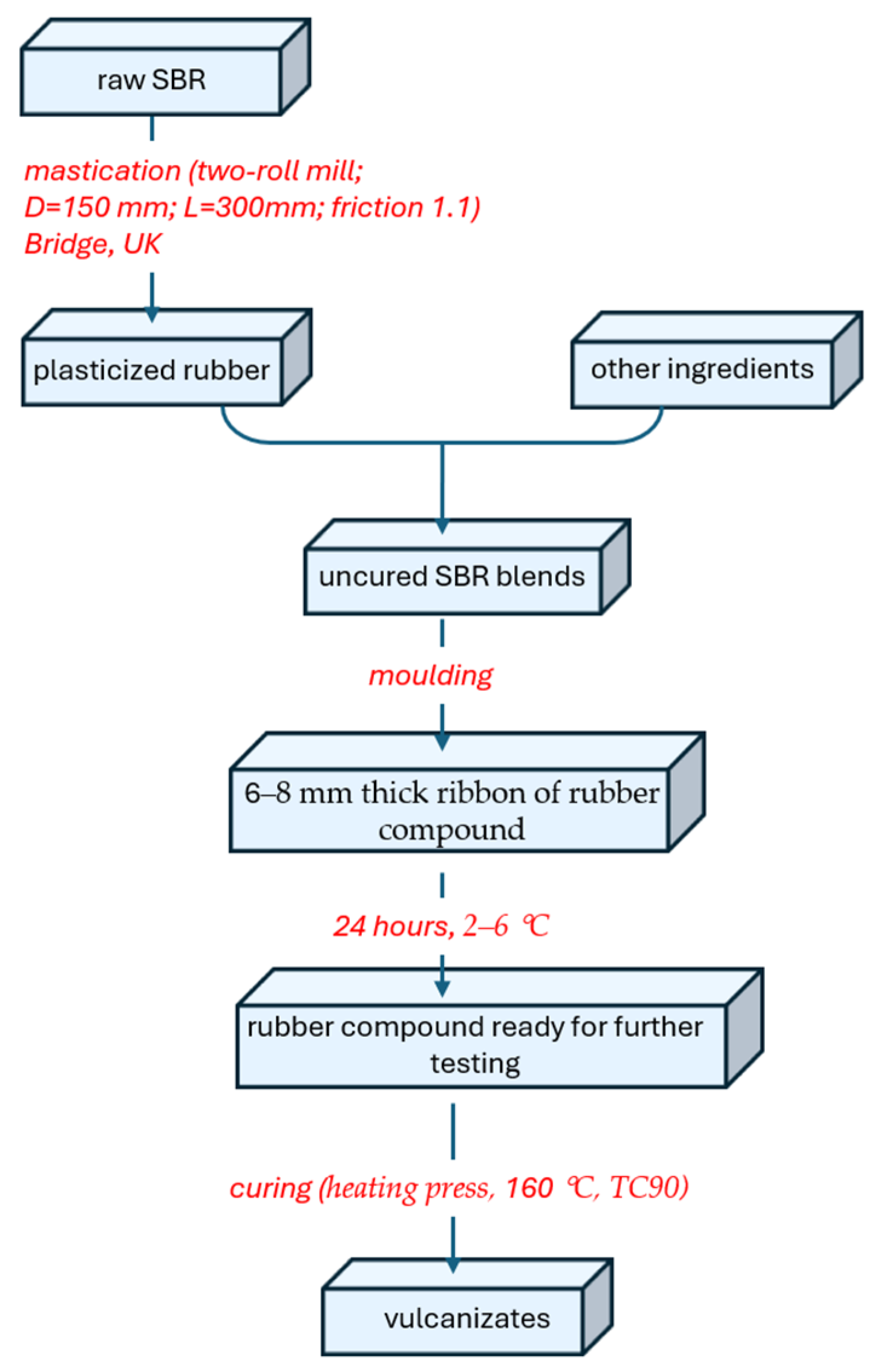

2.2. Preparation of Rubber Mixes and Vulcanizates

2.3. Methods of Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Properties of CB and GnPs

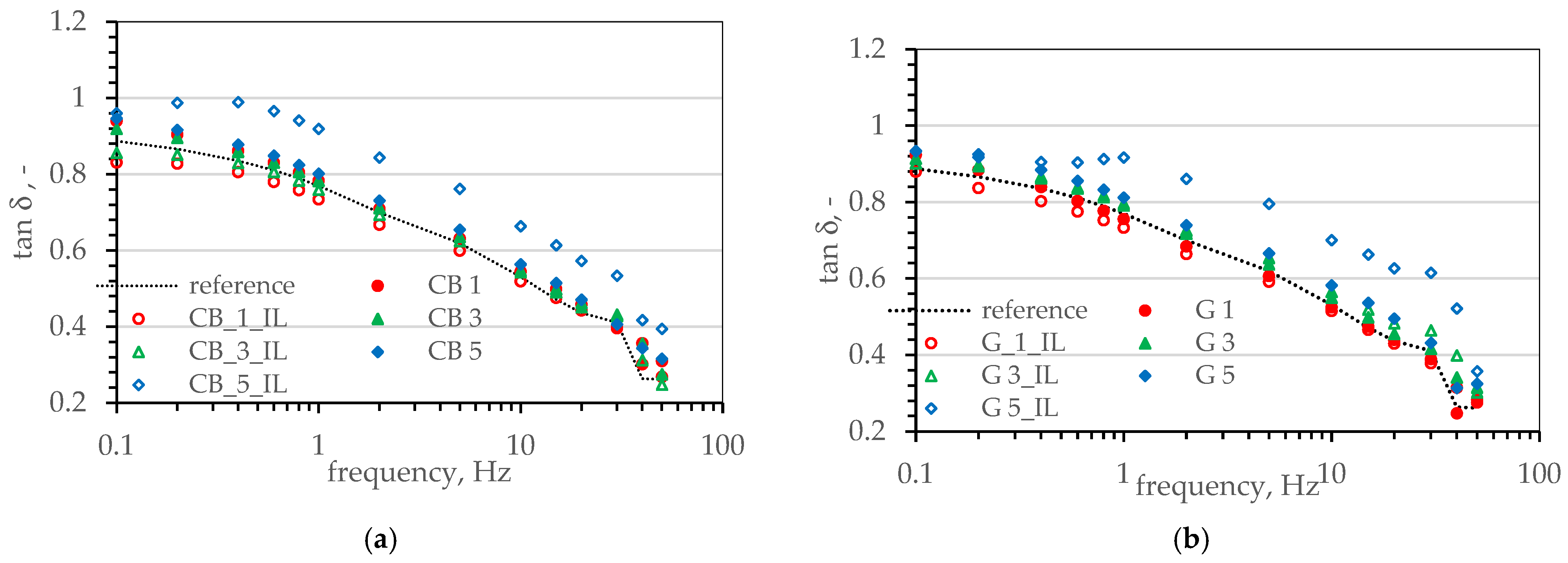

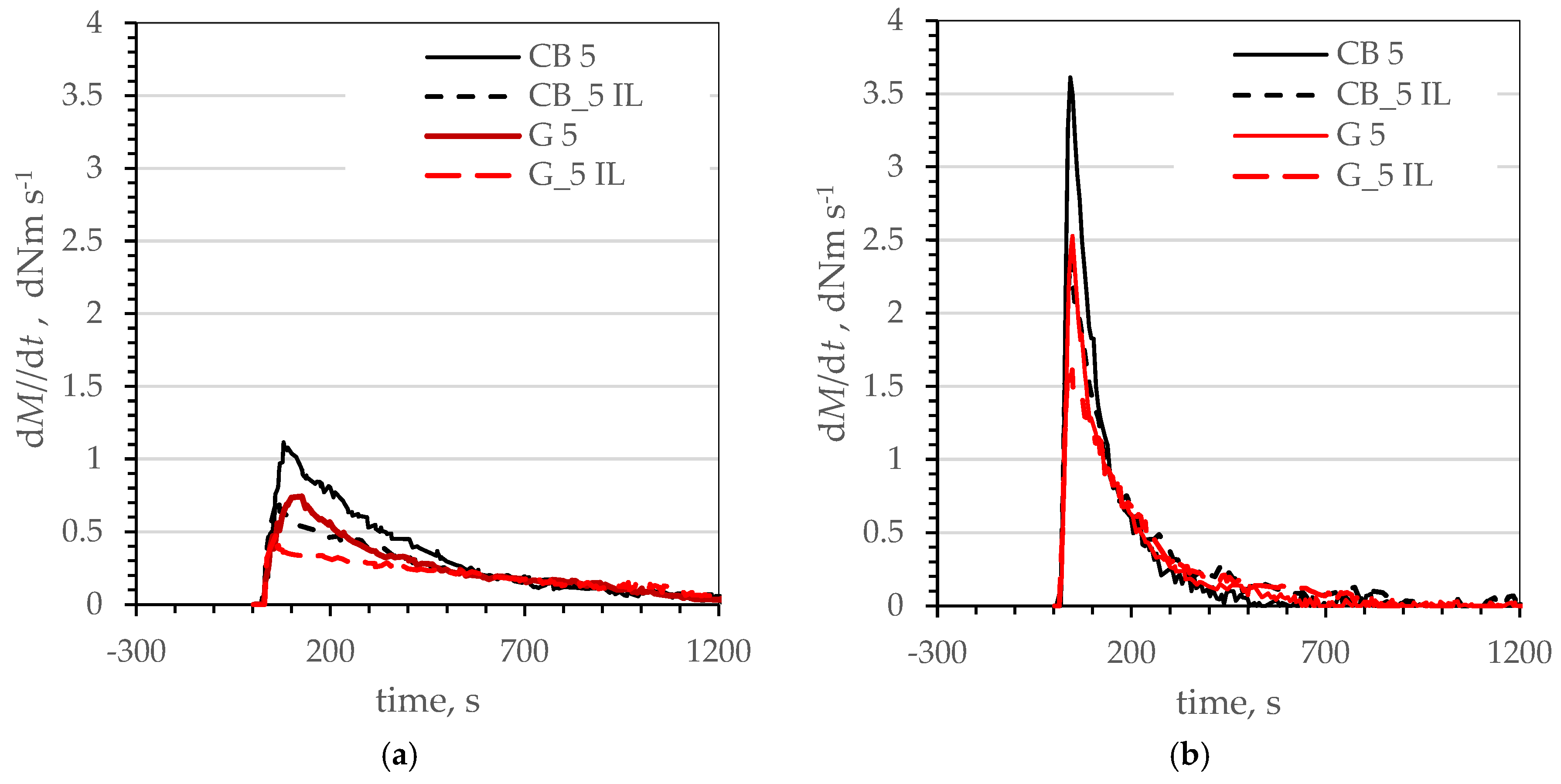

3.2. Viscoelastic Properties and Viscosity of Uncured Rubber Compounds

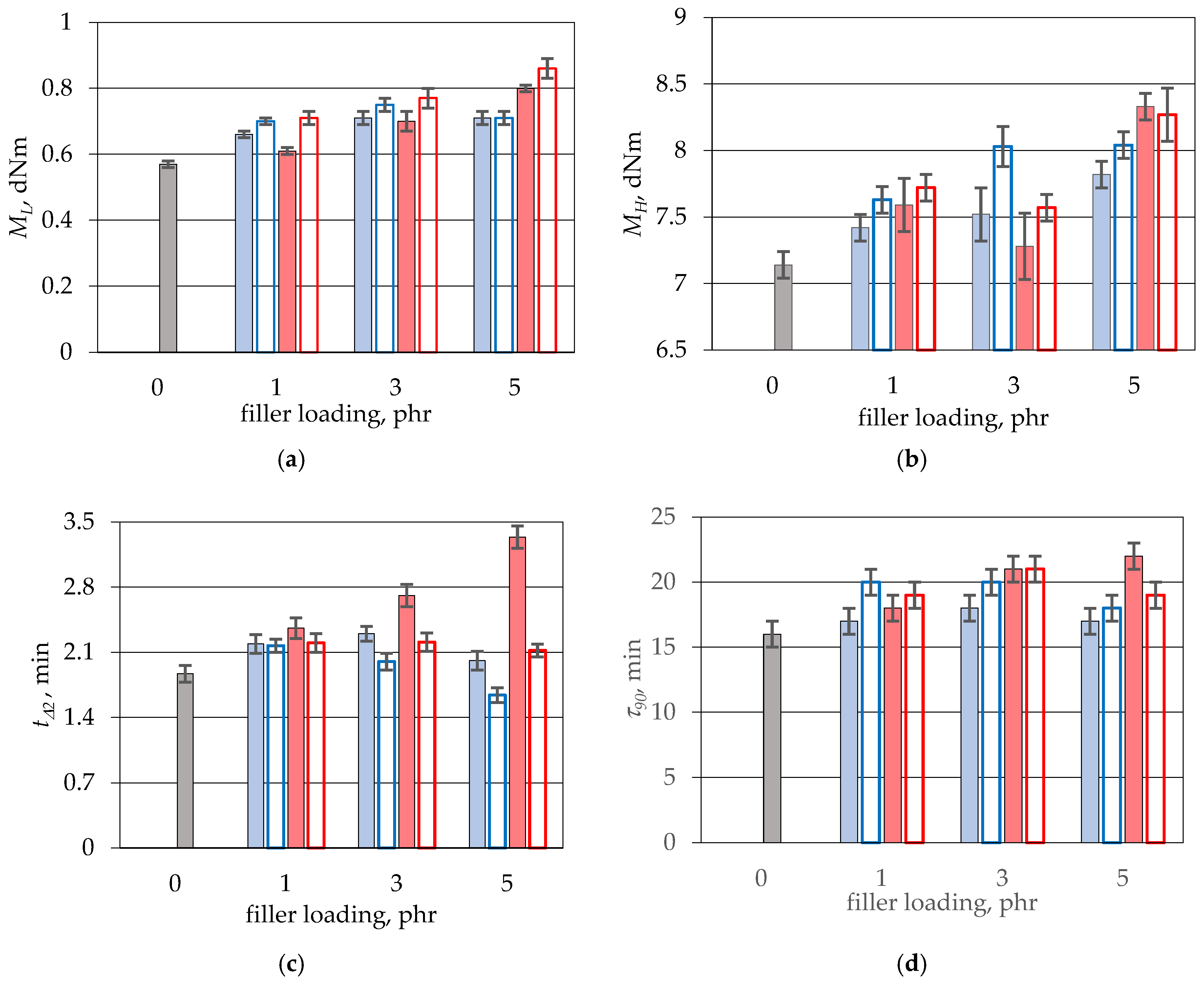

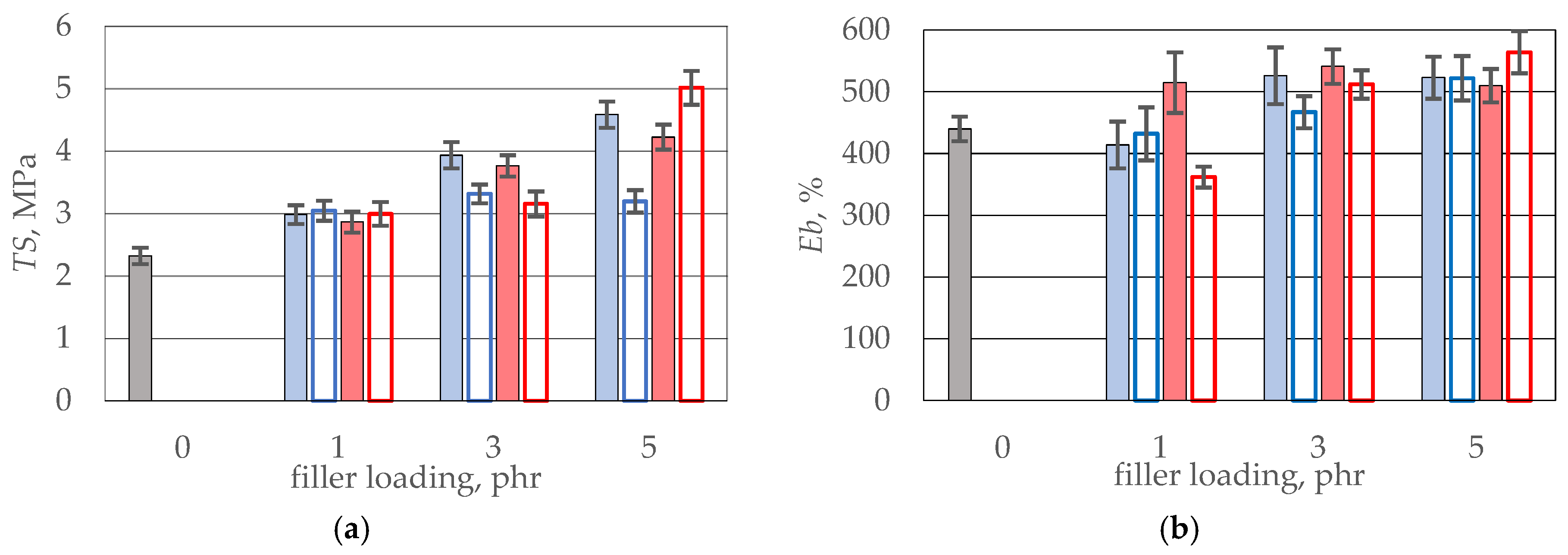

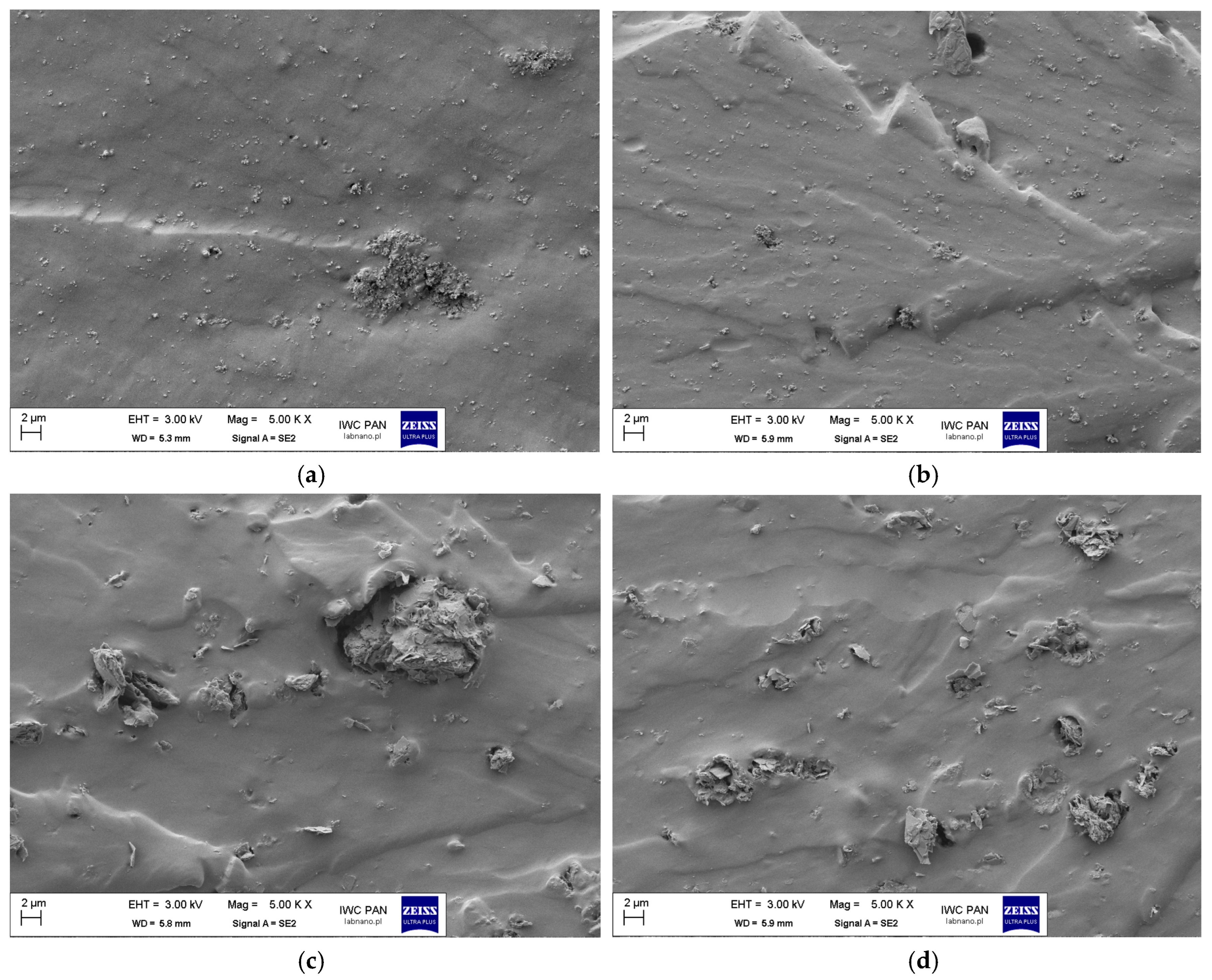

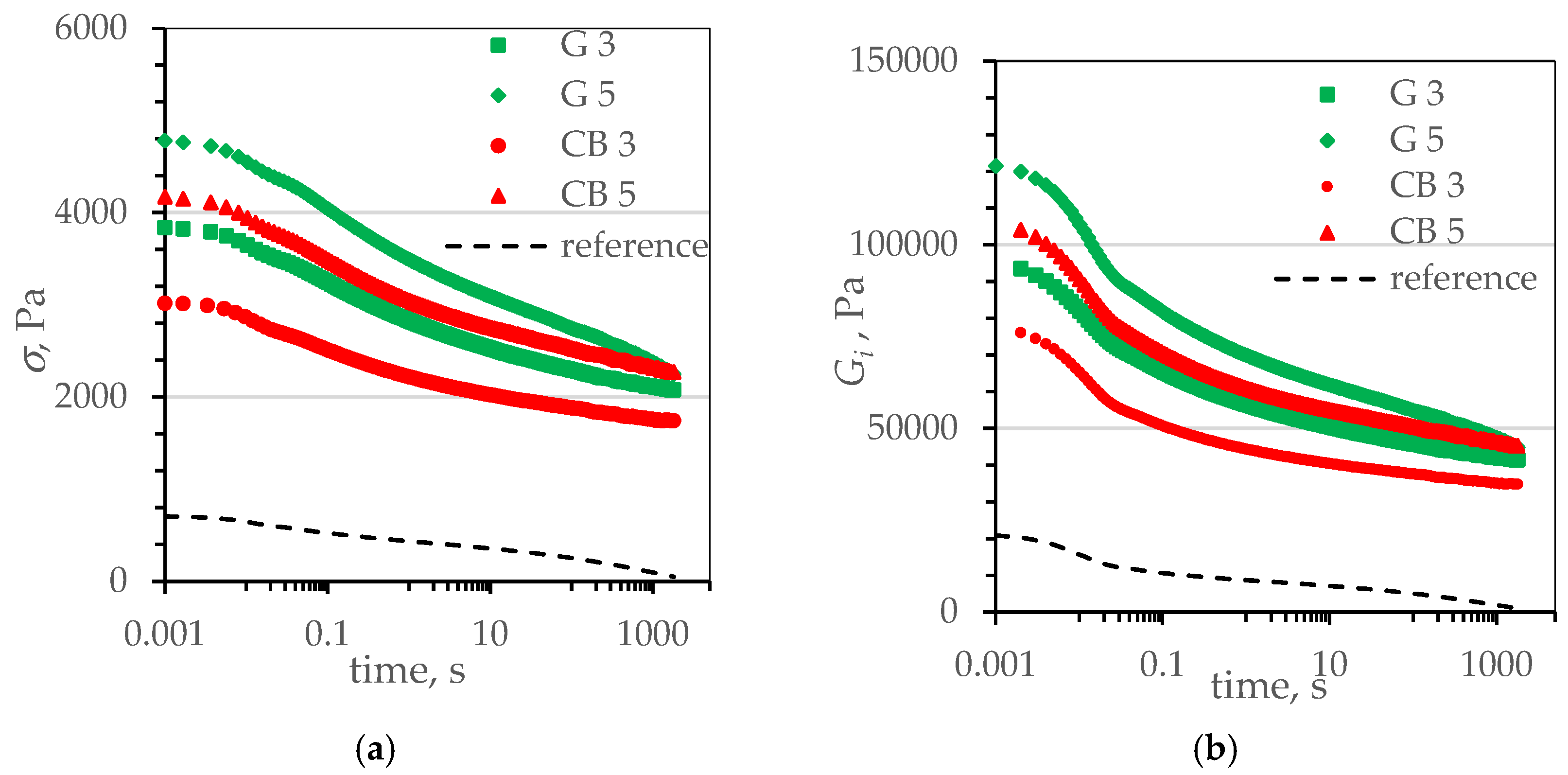

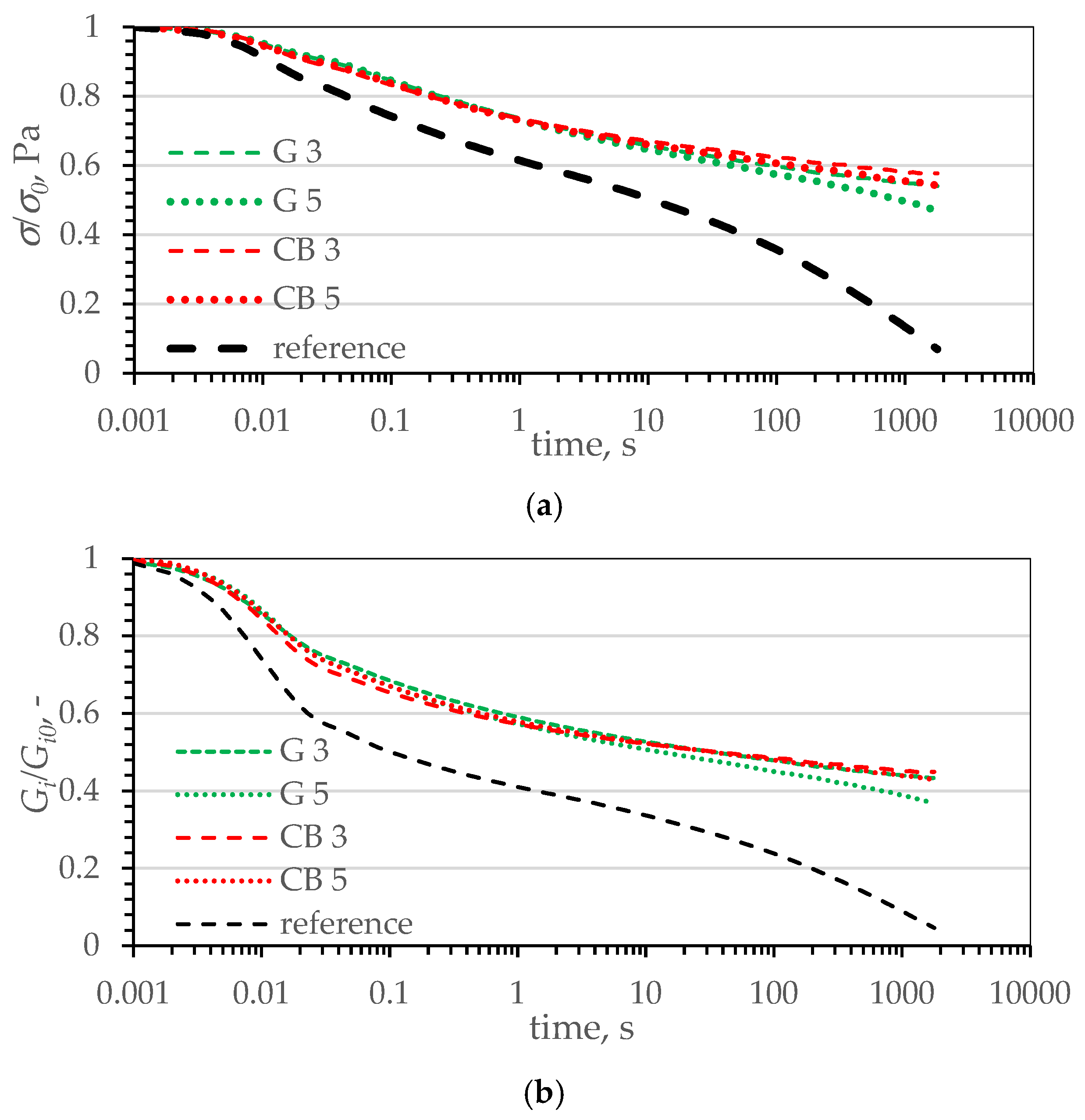

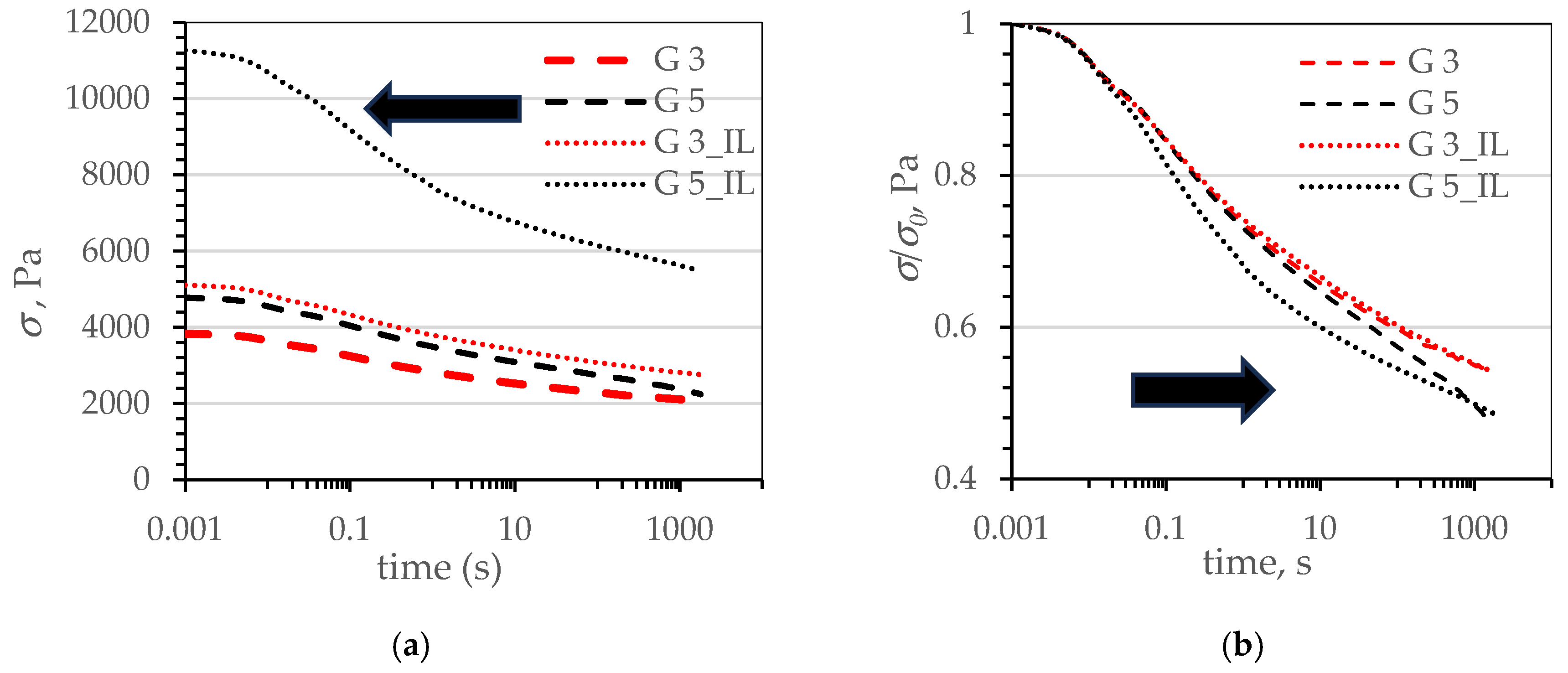

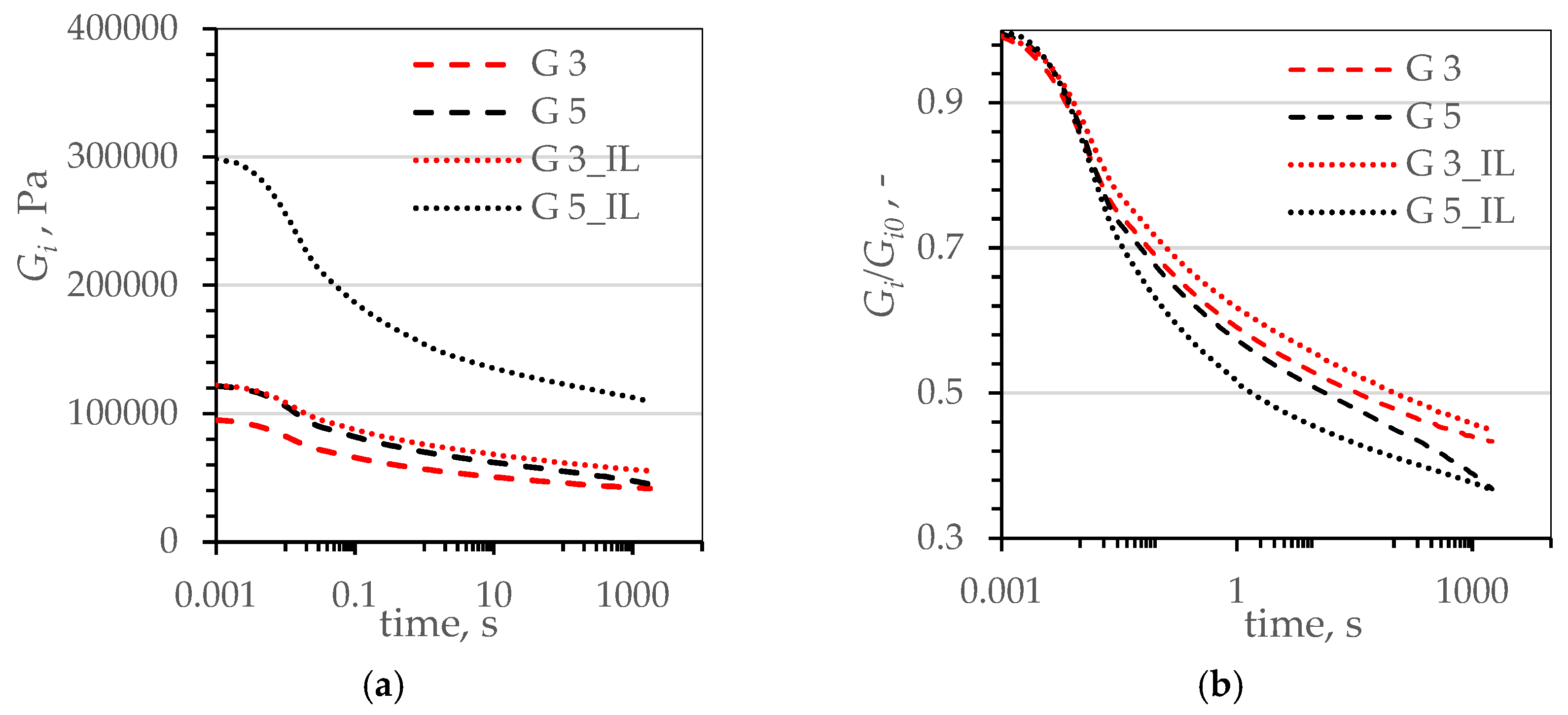

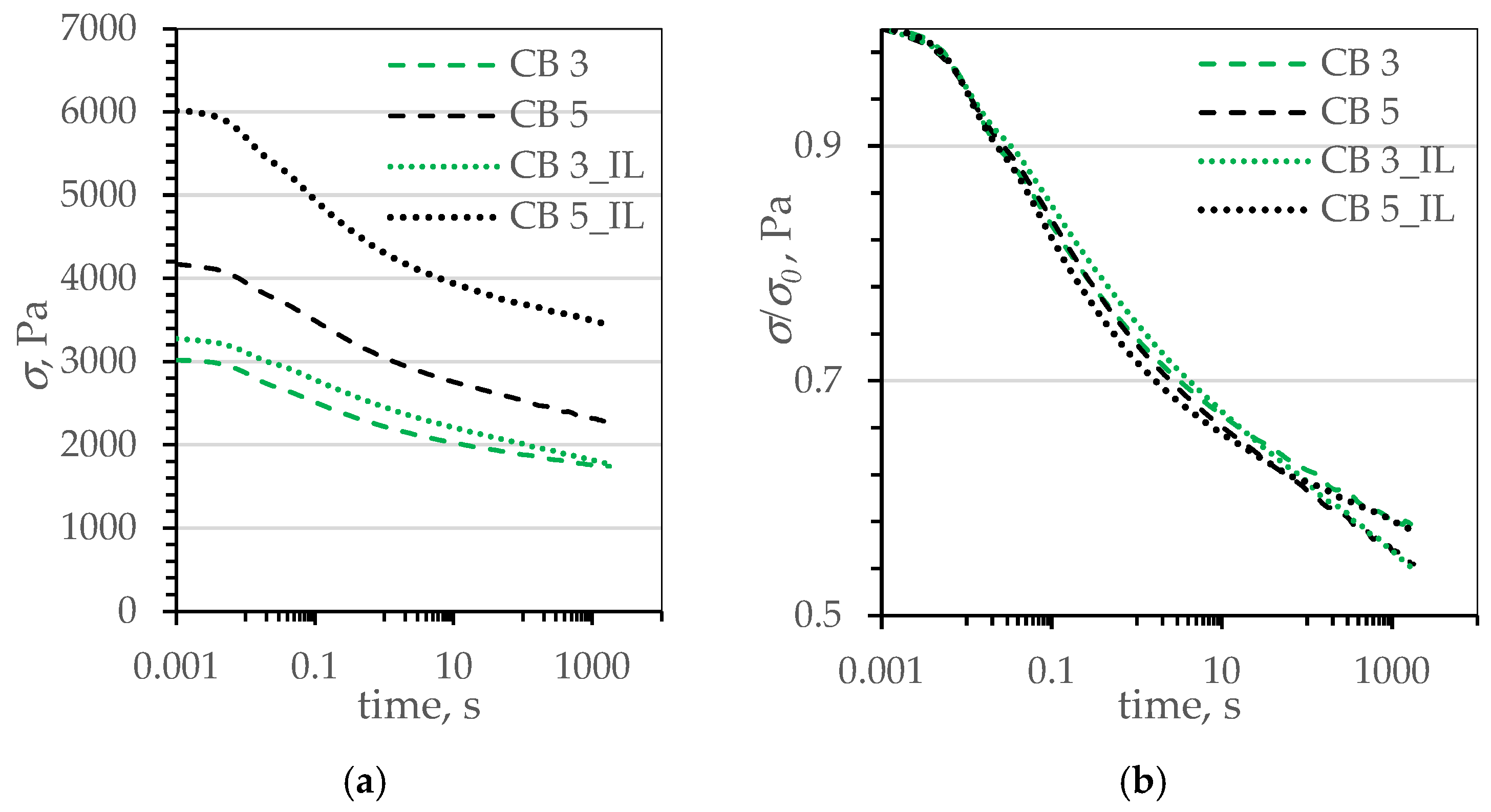

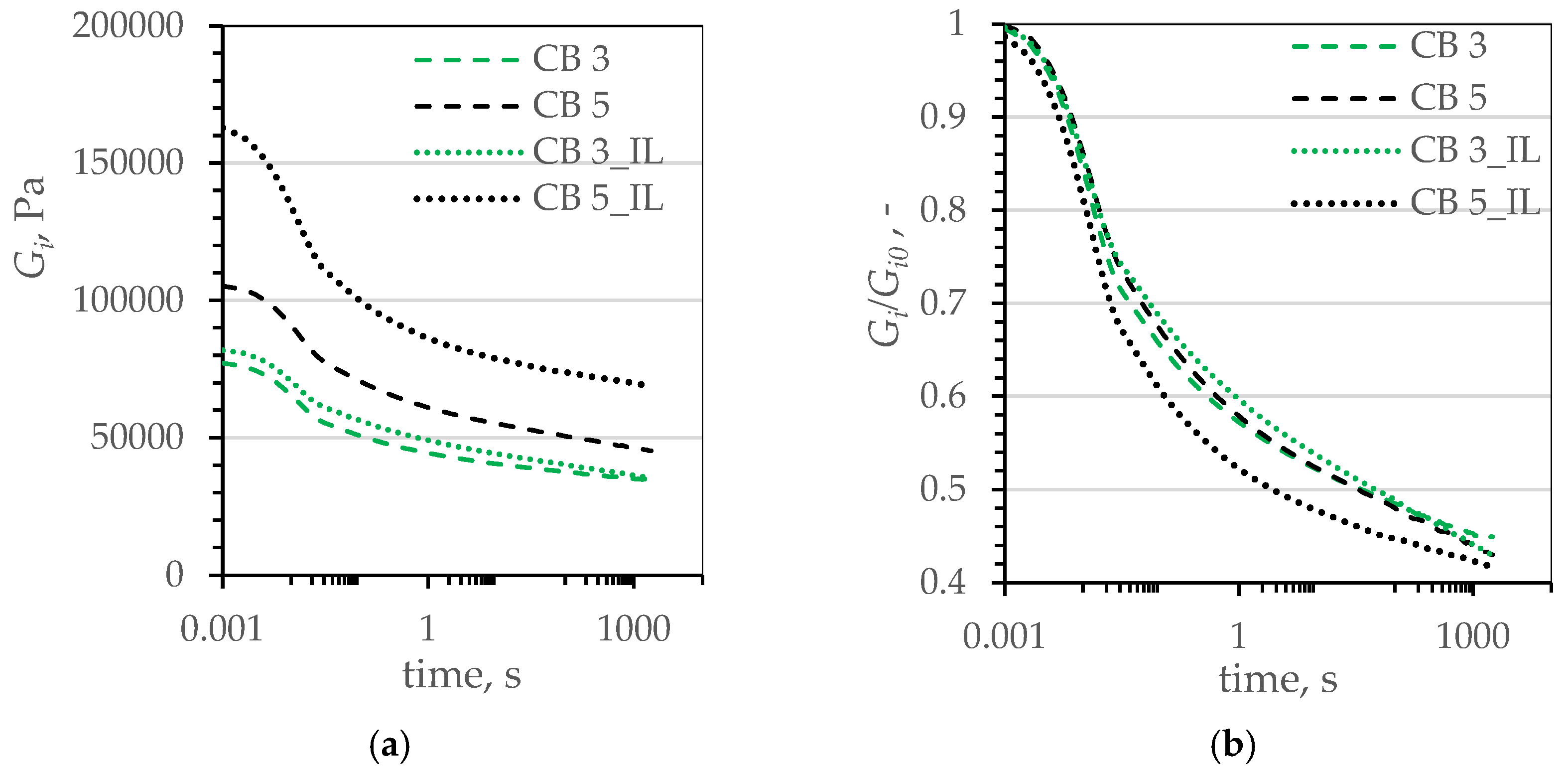

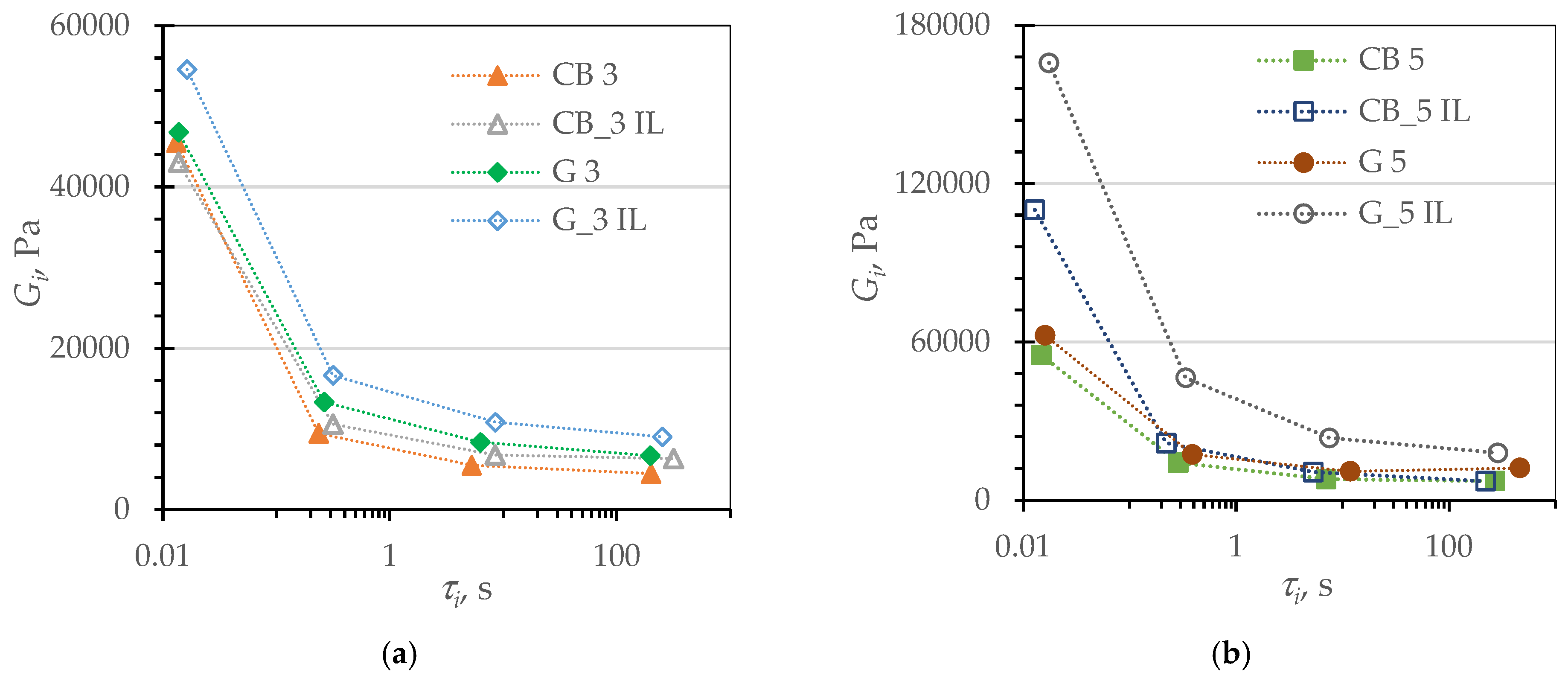

3.3. Properties of SBR Composites

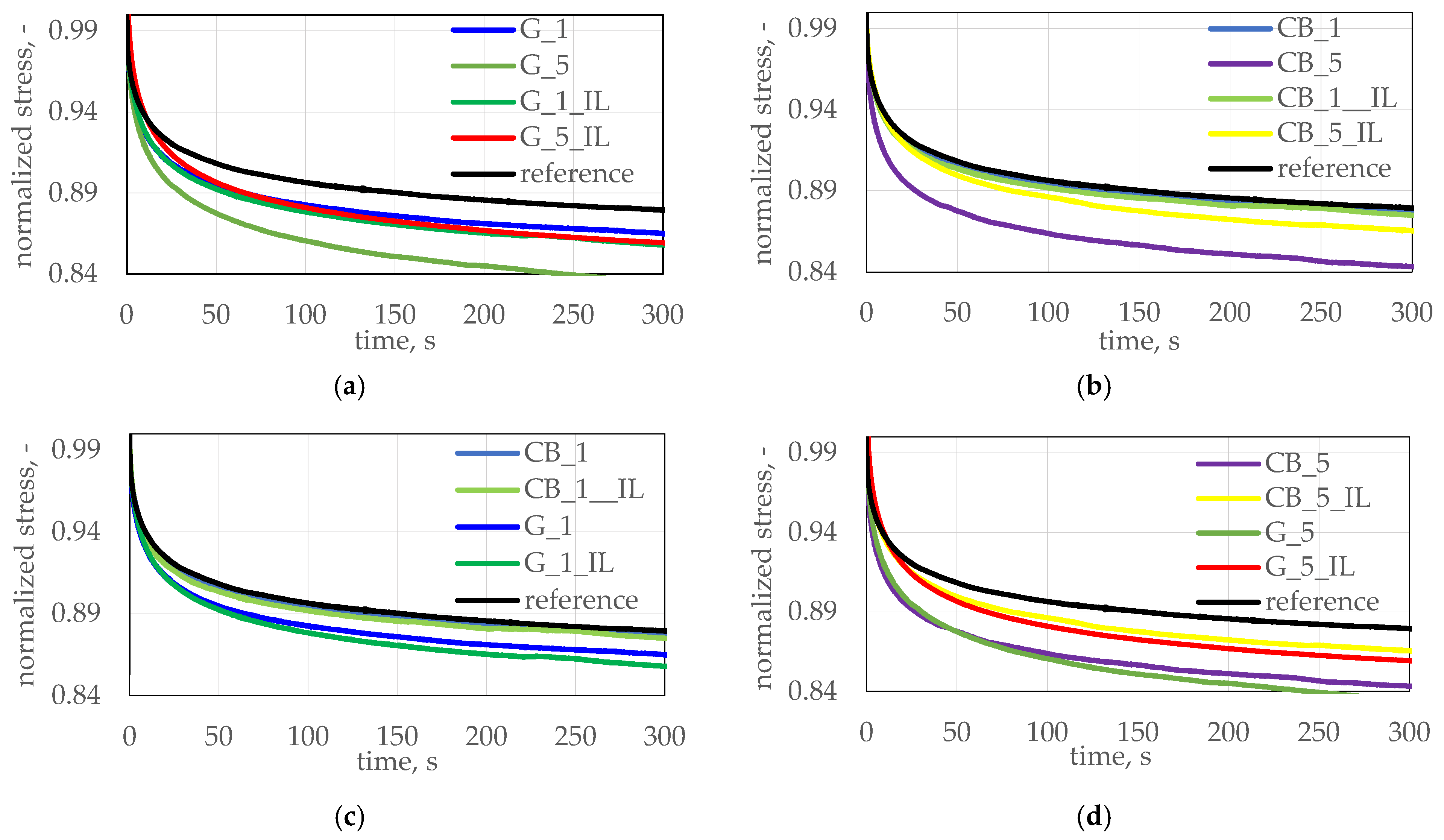

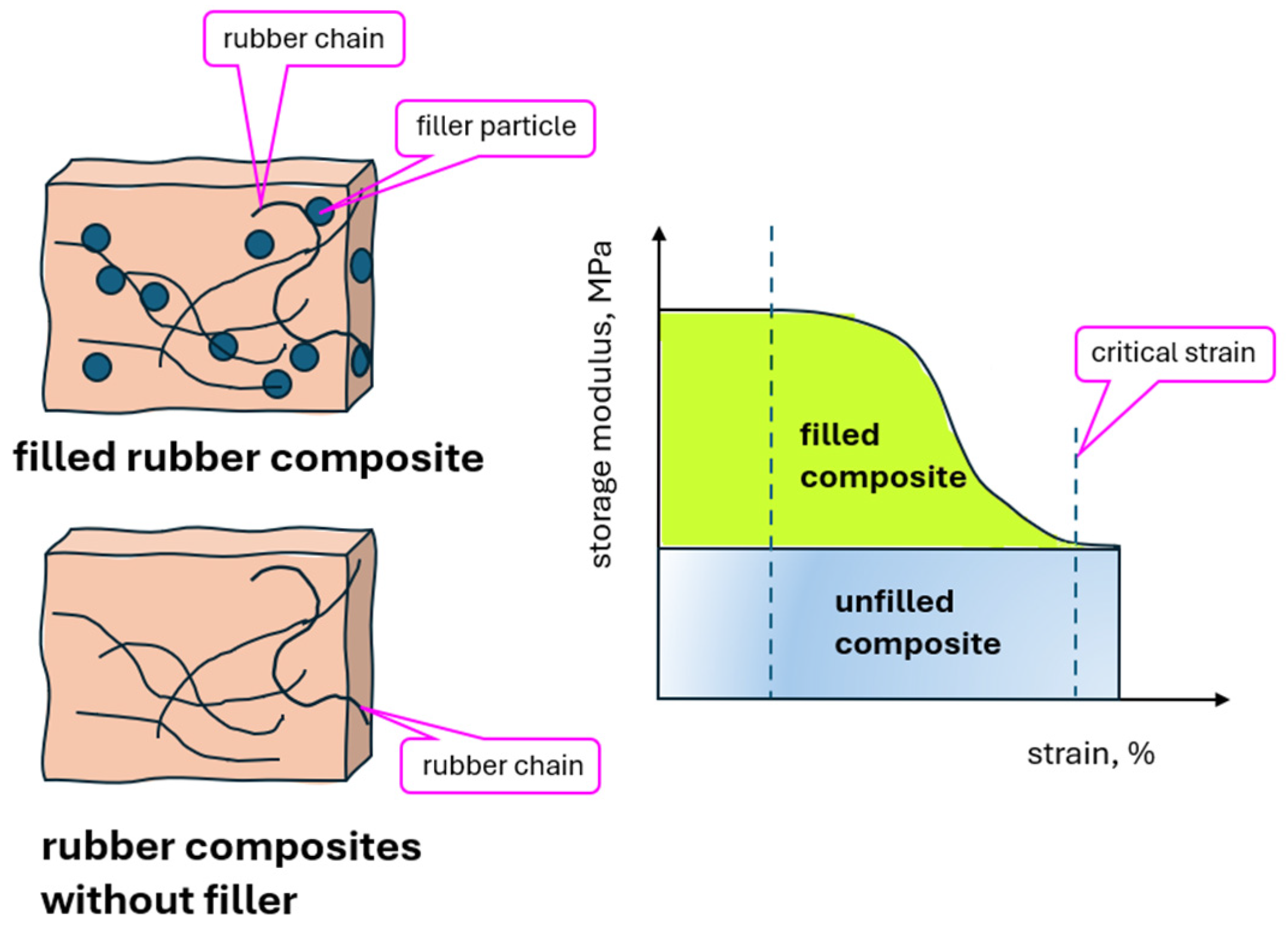

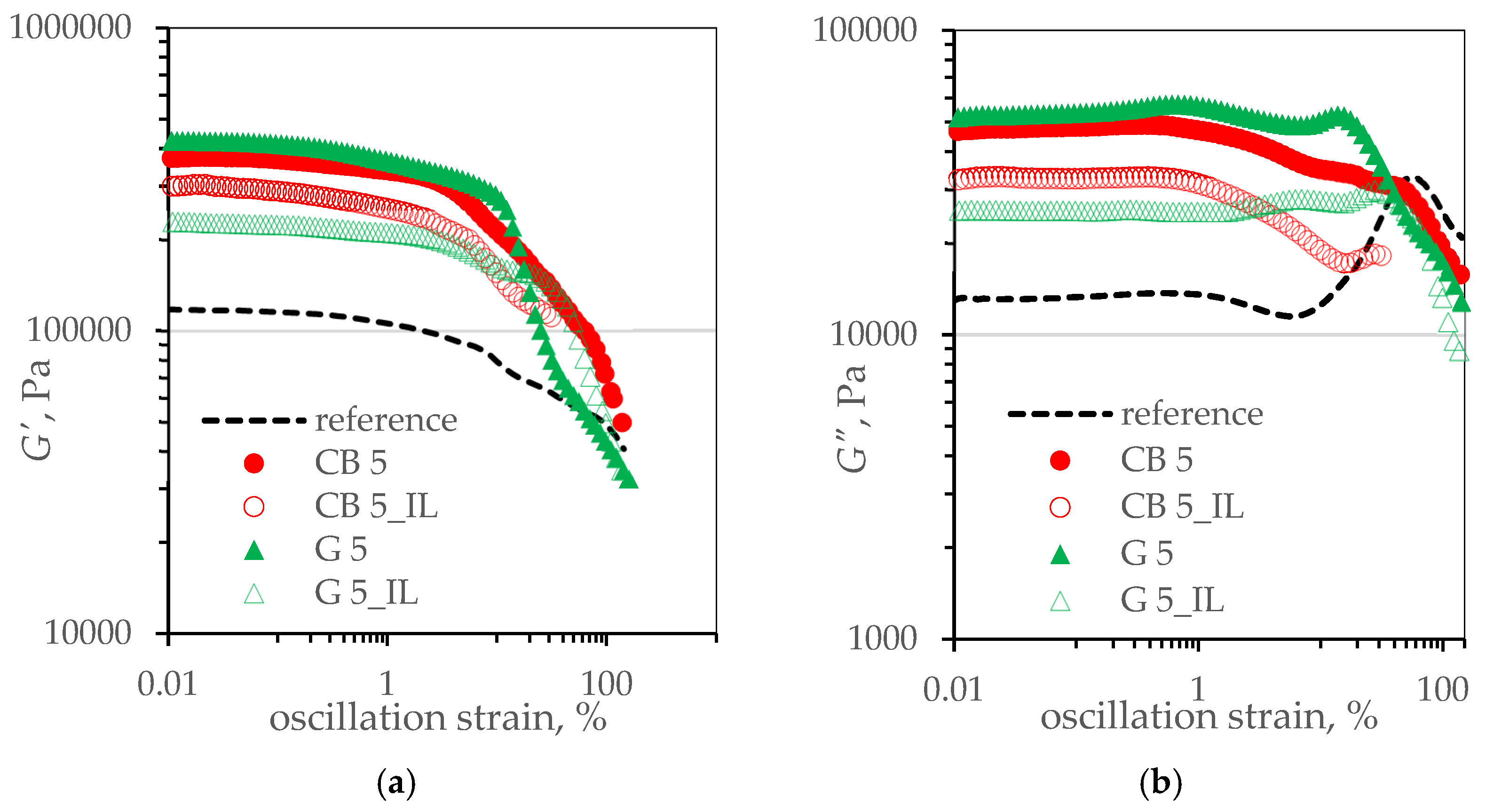

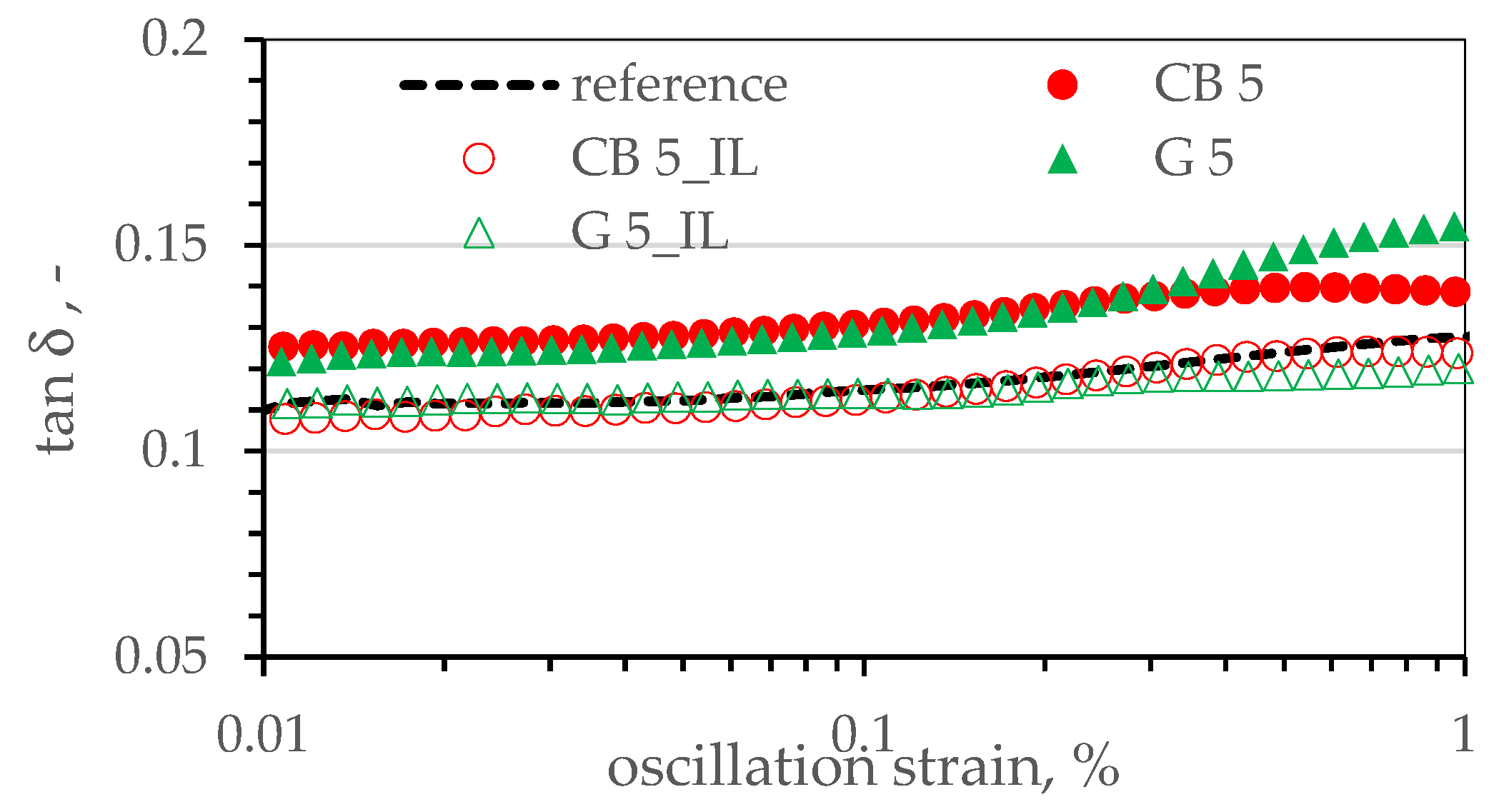

3.4. Viscoelastic Properties of SBR Composites. Payne’s Effect

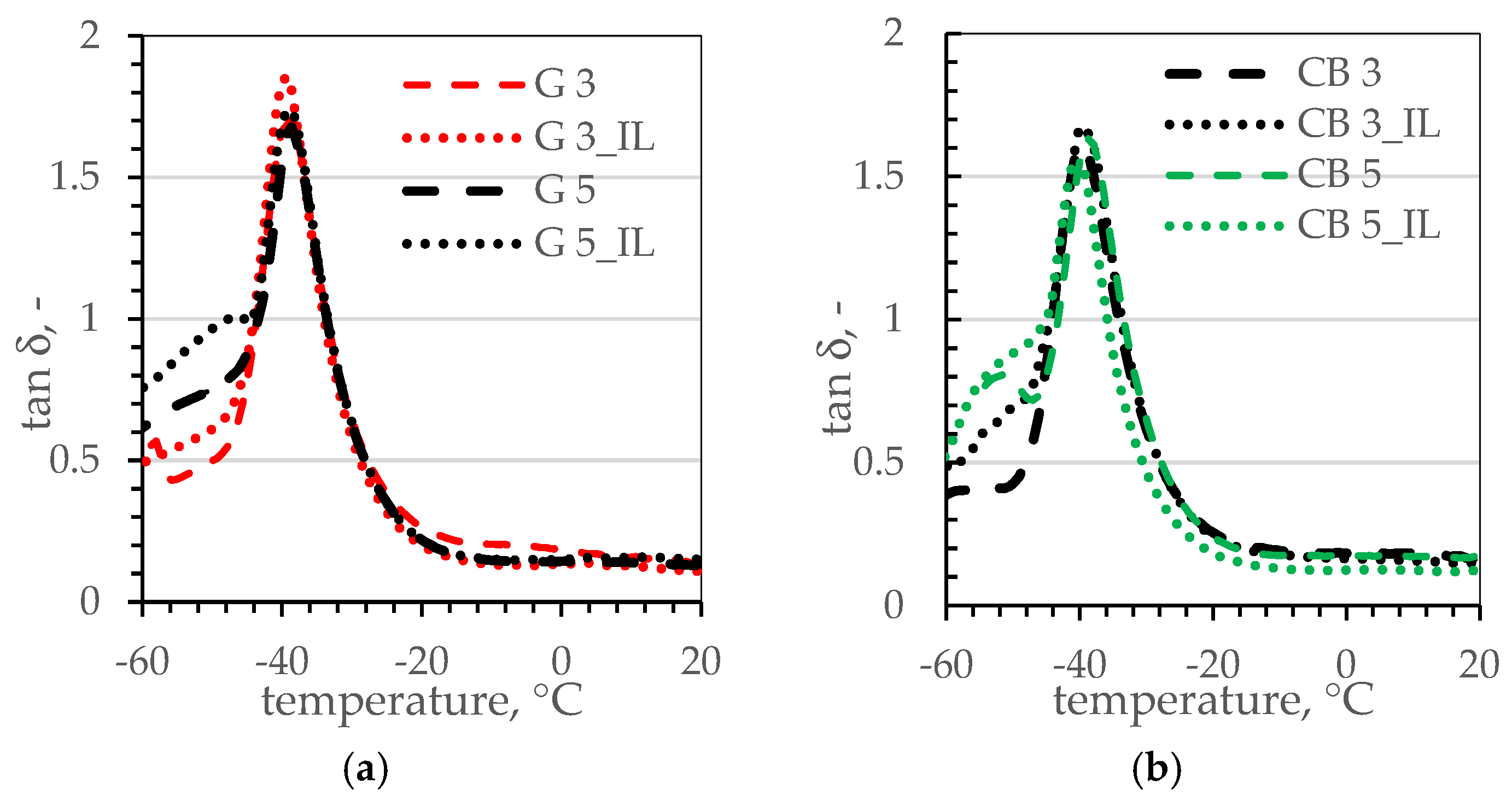

3.5. Thermal Properties of SBR Composites

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lim, K.; Kim, Y.A.; Ryu, M.S.; Jung, J.; Kim, D.; Li, Z.; Park, J.H.; Bang, J. Advanced silica networks in rubber composites for optimizing energy efficiency and performance in electric vehicle tires. ACS App. Polym. Mat. 2025, 7, 2731–2742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schouw, C.; Bernal-Ortega, P.; Anyszka, R.; Bijl, A.; Gucho, E.; Blume, A. Toward eco-friendly rubber utilizing paper waste-derived calcium carbonate to replace carbon Black in natural rubber composites. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damircheli, M.; MajidiRad, A.; Asmatulu, R. Calcium carbonate nanoparticle-reinforced rubber: Enhancing dynamic mechanical performance and thermal properties. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 36, 326–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boháč, P.; Nógellová, Z.; Šlouf, M.; Kronek, J.; Jankovič, Ľ.; Peidayesh, H.; Madejová, J.; Chodák, I. Nanocomposites of natural rubber containing montmorillonite modified by poly(2-oxazolines). Materials 2024, 17, 4017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Shemmari, F.; Rabah, A.; Al-Mulla, E.; Alrahman, N. Preparation and characterization of natural rubber latex/modified montmorillonite clay nano-composite. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2013, 39, 4293–4301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ding, X.; Wu, X.; Zhang, L. An efficient method to prepare high grafting montmorillonite with silane coupling agent and its improvements for styrene butadiene rubber composites. Polym. Compos. 2024, 45, 13127–13137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakar, M.; Przybyłek, M.; Białkowska, A.; Żurowski, W.; Hanulikova, B.; Stocek, R. Effect of mixing conditions and montmorillonite content on the mechanical properties of a chloroprene rubber. Mech. Compos. Mater. 2021, 57, 387–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, K.; Pongwisuthiruchte, A.; Debnath, S.A.; Potiyaraj, P. Application of cellulose as green filler for the development of sustainable rubber technology. Curr. Res. Green Sustain. Chem. 2021, 4, 100140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syuhada, D.N.; Azura, A.R. Waste natural polymers as potential fillers for biodegradable latex-based composites: A review. Polymers 2021, 13, 3600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurmu, D.N.; Gebrelibanos, H.M.; Tefera, C.A.; Sirahbizu, B. Experimental investigation the effect of bamboo micro filler on performance of bamboo-sisal-E-glass fiber-reinforced epoxy matrix hybrid composites. Heliyon 2024, 10, e40176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patidar, R.; Thakur, V.K.; Chaturvedi, R.; Khan, A.; Mallick, T.; Gupta, M.K.; Pappu, A. Production of natural straw-derived sustainable polymer composites for a circular agro-economy. ACS Sustain. Resour. Manag. 2024, 1, 1729–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeligbayeva, G.; Al Azzam, K.M.; Irmukhametova, G.; Bekbayeva, L.; Kairatuly, O.Z.; Iskalieva, A.; Negim, E.S.; Nadia, B. The effect of calcium carbonate, rice, and wheat straw on the biodegradability of polyethylene/starch films. Polymer Crystall. 2024, 2024, 8674988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masłowski, M.; Miedzianowska, J.; Strzelec, K. Natural rubber biocomposites containing corn, barley and wheat straw. Polym. Test. 2017, 63, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aprianti, N.; Kismanto, A.; Supriatna, N.K.; Yarsono, S.; Nainggolan, L.M.T.; Purawiardi, R.I.; Fariza, O.; Ermada, F.J.; Zuldian, P.; Raksodewanto, A.A.; et al. Prospect and challenges of producing carbon black from oil palm biomass: A review. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2023, 23, 101587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilke, L.A.; Robertson, C.G.; Karsten, D.A.; Hardman, N.J. Detailed understanding of the carbon black–polymer interface in filled rubber composites. Carbon 2023, 201, 520–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.H.; Zhang, J.; Chen, S.J. Effects of carbon blacks with various structures on vulcanization and reinforcement of filled ethylene-propylene-diene rubber. Express Polym. Lett. 2008, 2, 695–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tareen, M.H.K.; Hussain, F.; Zubair, Z.; Aslam, S.; Saleem, T.; Awais, M.; Farooq, A.; Goda, I. Effects of carbon black on epoxidized natural rubber composites: Rheological, abrasion, and mechanical study. J. Compos. Mater. 2022, 56, 4473–4485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chollakup, R.; Suethao, S.; Suwanruji, P.; Boonyarit, J.; Smitthipong, W. Mechanical properties and dissipation energy of carbon black/rubber composites. Compos. Adv. Mater. 2021, 30, 26349833211005476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, A.; Ikeda, Y.; Tsushi, R.; Kokubo, Y. A new approach to visualizing the CB/natural rubber interaction layer in CB-filled natural rubber vulcanizates and to elucidating the dependence of mechanical properties on quantitative parameters. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2013, 291, 2101–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongsorat, W.; Suppakarn, N.; Jarukumjorn, K. Influence of Filler Types on Mechanical Properties and Cure Characteristics of Natural Rubber Composites. Adv. Mater. Res. 2011, 264–265, 646–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaca, M.; Vaulot, C.; Maciejewska, M.; Lipińska, M. Preparation and properties of SBR composites containing graphene nanoplatelets modified with pyridinium derivative. Materials 2020, 13, 5407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaca, M.; Vaulot, C. Effect of fillers modification with ILs on fillers textural properties: Thermal properties of SBR composites. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakošová, A.; Bakošová, D.; Dubcová, P.; Klimek, L.; Dedinský, M.; Lokšíková, S. Effect of thermal aging on the mechanical properties of rubber composites reinforced with carbon nanotubes. Polymers 2025, 17, 896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakošová, D.; Bakošová, A. Testing of rubber composites reinforced with carbon nanotubes. Polymers 2022, 14, 3039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esmaeili, A.; Masters, I.; Hossain, M. A novel carbon nanotubes doped natural rubber nanocomposite with balanced dynamic shear properties and energy dissipation for wave energy applications. Results Mater. 2023, 17, 100358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnet, J.-B.; Custodéro, E.; Wang, T.K.; Hennebert, G. Energy site distribution of carbon black surfaces by inverse gas chromatography at finite concentration conditions. Carbon 2002, 40, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stöckelhuber, K.W.; Svitskov, A.S.; Pelevin, A.G.; Heinrich, G. Impact of filler surface modification on large scale mechanics of styrene butadiene/silica rubber composites. Macromolecules 2011, 44, 4366–4381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pont, K.D.; Gerard, J.-F.; Espuche, E. Microstructure and properties of styrene-butadiene rubber based nanocomposites prepared from an aminosilane modified synthetic lamellar nanofiller. J. Polym. Sci. 2013, 51, 1051–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.N.; Kumar, V.; Potiyaraj, P.; Lee, D.-J.; Choi, J. Mutual dispersion of graphite–silica binary fillers and its effects on curing, mechanical, and aging properties of natural rubber composites. Polym. Bull. 2022, 79, 2707–2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Chattopadhyay, S.; Dhanania, S.; Bhowmick, A.K. Improved dispersion and physico-mechanical properties of rubber/silica composites through new silane grafting. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2020, 60, 3115–3134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokobza, L. Elastomer nanocomposites: Effect of filler–matrix and filler–filler interactions. Polymers 2023, 15, 2900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijay, R.; Menon, A.R.R. Reinforcing effect of organo-modified fillers in rubber composites as evidenced from DMA studies. J. Mat. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 12, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Wang, L.; Cui, Z.; Liu, Y.; Du, A. Multifunctional application of ionic liquids in polymer materials: A brief review. Molecules 2023, 28, 3836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gholinejad, M.; Zareh, F.; Sheibani, H.; Nájera, C.; Yus, M. Magnetic ionic liquids as catalysts in organic reactions. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 367, 120935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Savoy, A.W. Ionic liquids synthesis and applications: An overview. J. Mol. Liq. 2020, 297, 112038–1122060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, J.; Sisanth, K.S.; Zachariah, A.K.; Mariya, H.J.; George, S.C.; Kalarikkal, N.; Thomas, S. Transport and solvent sensing characteristics of styrene butadiene rubber nanocomposites containing imidazolium ionic liquid modified carbon nanotubes. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2020, 137, 49429–49438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldas, C.M.; Soares, B.G.; Indrusiak, T.; Barra, G.M.O. Ionic liquids as dispersing agents of graphene nanoplatelets in poly(methyl methacrylate) composites with microwave absorbing properties. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2020, 138, 49814–49831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.K.L.; Soares, B.G.; Duchet-Rumeau, J.; Livi, S. Dual functions of ILs in the core-shell particle reinforced epoxy networks: Curing agent vs. dispersion aids. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2017, 140, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, L.; Kan, M.; Jerrams, S.; Zhang, R.; Xu, Z.; Liu, L.; Wen, S.; Zhang, L. Constructing chemical interface layers by using ionic liquid in graphene oxide/rubber composites to achieve high-wear resistance in environmental-friendly green tires. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 5995–6004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utrera-Barrios, S.; Perera, R.; León, N.; Hernández Santana, M.; Martínez, N. Reinforcement of natural rubber using a novel combination of conventional and in situ generated fillers. Composites C 2021, 5, 100133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, J.M.; Carswell, W.D.; García-Sakai, V.; Frick, B.; Boothroyd, S.C.; Hutchings, L.R.; Clarke, N.; Thompson, R.L. Structural and dynamic origins of Payne effect reduction by steric stabilization in silica reinforced poly(butadiene) nanocomposites. Polym. Compos. 2025, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipińska, M.; Gaca, M.; Zaborski, M. Curing kinetics and ionic interactions in layered double hydroxides–nitrile rubber Mg–Al-LDHs–XNBR composites. Polym. Bull. 2021, 78, 3199–3226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaca, M.; Slouf, M.; Vaulot, C.; Mrlik, M.; Ilcikova, M.; Sloufova, I.; Pietrasik, J. Enhancement of interactions in styrene−butadiene rubber composites filled with GnPs through styrene content and presence of ionic liquid: Impact on photo−actuator performance. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2025, 396, 117189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaca, M.; Ilcikova, M.; Mrlik, M.; Cvek, M.; Vaulot, C.; Urbanek, P.; Pietrasik, R.; Krupa, I.; Pietrasik, J. Impact of ionic liquids on the processing and photo—Actuations behavior of SBR composites containing graphene nanoplatelets. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2021, 329, 129195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirityi, D.Z.; Bárány, T.; Pölöskei, K. Hybrid reinforcement of styrene-butadiene rubber nanocomposites with carbon black, silica, and graphene. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2022, 139, e52766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Library of MedicineNational Center for Biotechnology Information. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/1-Butyl-4-methylpyridinium-bromide#section=3D-Conformer (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- National Library of MedicineNational Center for Biotechnology Information. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/1-Butyl-4-methylpyridinium-bromide (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Wu, S.; Brzozowski, K.J. Surface free energy and polarity of organic pigments. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1971, 37, 686–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaelble, D.H. Dispersion-polar surface tension properties of organic solids. J. Adhes. 1970, 2, 66–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 6502-3:2018; Rubber—Measurement of Vulcanization Characteristics Using Curemeters—Part 3: Rotorless Rheometer. International Organization for Standarization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Sengupta, S.; Esseghir, M.; Cogen, J.M. Effect of formulation variables on cure kinetics, mechanical, and electrical properties of filled peroxide cured ethylene-propylene-diene monomer compounds. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2011, 120, 2191–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isayev, A.I.; Deng, J.S. Non-isotermal vulcanization of rubber compounds. Rubb. Chem. Technol. 1988, 61, 340–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D6204 (Part A and B); Standard Test Method for Rubber—Measurement of Unvulcanized Rheological Properties Using Rotorless Shear Rheometers. ASTM International Headquarters: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019.

- Müllner, H.W.; Jäger, A.; Aigner, E.G.; Eberhardsteiner, J. Experimental identification of viscoelastic properties of rubber compounds by means of torsional rheometry. Meccanica 2008, 43, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flory, P.J.; Rehner, J. Statistical mechanics of cross-linked polymer networks. II. Swelling. J. Chem. Phys. 1943, 11, 521–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaca, M.; Zaborski, M. The properties of elastomers obtained with the use of carboxylated acrylonitrile-butadiene rubber and new crosslinking substances. Polimery 2016, 65, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 37:2017; Rubber, Vulcanized or Thermoplastic—Determination of Tensile Stress-Strain Properties. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Kohjiya, S.; Ikeda, Y. Reinforcement of general purpose grade rubbers by silica generated in situ. Rub. Chem. Technol. 2000, 73, 534–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, C.G.; Hardman, N.J. Nature of carbon black reinforcement of rubber: Perspective on the original polymer nanocomposite. Polymers 2021, 13, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tapia-Romero, M.A.; Dehonor-Gómez, M.; Lugo-Uribe, L.E. Prony series calculation for viscoelastic behavior modeling of structural adhesives from DMA data. Ingeneria Investig. Tecnol. 2020, 21, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslan, G.; Aktürk, N. Experimental and theoretical analysis of frequency- and temperature-dependent characteristics in viscoelastic materials using Prony series. Appl. Mechan. 2024, 5, 786–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, A.R. The dynamic properties of carbon black loaded natural rubber vulcanizates Part I. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1962, 6, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick, J.S. Compound processing characteristics and testing. In Rubber Technology Compounding and Testing for Performance; Hanser Publishers: Münich, Germany, 2009; pp. 17–45. [Google Scholar]

- Lipińska, M.; Soszka, K. Viscoelastic behavior, curing and reinforcement mechanism of various silica and POSS filled methyl-vinyl polysiloxane MVQ rubber. Silicon 2019, 11, 2293–2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matchawet, S.; Kaesaman, A.; Vennemann, N.; Kumerlöwe, C.; Nakason, C. Effects of imidazolium ionic liquid on cure characteristics, electrical conductivity and other related properties of epoxidized natural rubber vulcanizates. Eur. Polym. J. 2017, 87, 344–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, H.H.; Hamann, E.; Ilisch, S.; Heinrich, G.; Radusch, H.-J. Selective wetting and dispersion of filler in rubber composites under influence of processing and curing additives. Polymer 2014, 55, 1560–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare, Y. Study of nanoparticles aggregation/agglomeration in polymer particulate nanocomposites by mechanical properties. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2016, 84, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, B.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Wen, Y.; Jia, H.; Ji, Q.; Ding, L. Ionic liquid functionalized graphene oxide for enhancement of styrene-butadiene rubber nanocomposites. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2017, 28, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinasankarapillai, V.S.; Sundararajan, A.; Easwaran, E.C.; Pourmadadi, M.; Aslani, A.; Dhanusuraman, R.; Rahdar, A.; Kyzas, G.Z. Application of ionic liquids in rubber elastomers: Perspectives and chellenges. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 382, 121846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Niu, F.; Liu, J.; Yin, H. Research progress of natural rubber wet mixing technology. Polymers 2024, 16, 1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shashok, Z.S.; Prokopchuk, N.R.; Uss, E.P.; Zhdanok, S.A. Elastomeric compounds with fine-grained carbonic additives. J. Eng. Phys. Thermophys. 2020, 93, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Hu, M.; Li, Y.; Li, R.; Qing, L. Significant influence of bound rubber thickness on the rubber reinforcement effect. Polymers 2023, 15, 2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derham, C.J. Creep and stress relaxation of rubbers-the effect of stress history and temperature changes. J. Mat. Sci. 1973, 8, 1023–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maria, H.J.; Lyczko, N.; Nzihou, A.; Joseph, K.; Mathew, C.; Thomas, S. Stress relaxation behavior of organically modified montmorillonite filled natural rubber/nitrile rubber nanocomposites. Appl. Clay Sci. 2014, 87, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innes, J.R.; Young, R.J.; Papageorgiou, D.G. Graphene nanoplatelets as a replacement for carbon black in rubber compounds. Polymers 2022, 14, 1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrburger-Dolle, F.; Blay, F.; Geissler, E.; Livet, F.; Morfin, I.; Rochas, C. Filler networks in elastomers. Macromol. Symp. 2003, 200, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wan, H.; Zhou, H.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, L.; Lyulin, A.V. Formation mechanism of bound rubber in elastomer nanocomposites: A molecular dynamics simulation study. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 13008–13017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niedermeier, W.; Fröhlich, J.; Luginsland, H.-D. Reinforcement mechanism in the rubber matrix by active fillers. Kautsch. Gummi Kunstst. 2002, 55, 256–366. [Google Scholar]

| Name | Reference | CB | CB_IL | G | G_IL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ingredients | ||||||

| Rubber | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

| Sulfur | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| MBTS | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | |

| DPG | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | |

| Carbon black | - | 1–5 | 1–5 | - | - | |

| GnPs | - | - | - | 1–5 | 1–5 | |

| Ionic liquid | - | - | 0.23–1.15 | - | 0.23–1.15 | |

| Filler | γs mN m−1 | γd mN m−1 | γp mN m−1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| G | 20.7 | 20.6 | 0.1 |

| G_IL | 30.2 | 24.6 | 5.6 |

| CB | 29.1 | 27.9 | 1.2 |

| CB_IL | 35.4 | 24.8 | 10.7 |

| Sample’s Name | η*max, kPa·s | η′max, kPa·s | Δη*, kPa·s | Δη′, kPa·s | η*2 min, kPa·s | η′2 min, kPa·s |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| reference | 27.91 | 16.92 | 1.55 | 1.09 | 26.36 ± 0.64 | 15.83 ± 0.25 |

| G 1 | 32.40 | 19.74 | 4.33 | 3.09 | 28.07 ± 0.59 | 16.65 ± 0.35 |

| G 1_IL | 31.47 | 20.21 | 1.93 | 3.43 | 29.54 ± 0.45 | 16.78 ± 0.08 |

| G 3 | 34.16 | 20.91 | 3.5 | 3.17 | 30.66 ± 0.57 | 17.74 ± 0.29 |

| G 3_IL | 37.44 | 23.22 | 5.13 | 4.41 | 32.31 ± 0.52 | 18.81 ± 0.59 |

| G 5 | 36.03 | 21.10 | 3.58 | 2.12 | 32.45 ± 0.62 | 18.98 ± 0.25 |

| G 5_IL | 37.45 | 22.19 | 3.67 | 3.28 | 33.78 ± 0.51 | 18.91 ± 0.08 |

| CB 1 | 30.95 | 18.32 | 3.46 | 1.89 | 27.49 ± 0.69 | 16.43 ± 0.12 |

| CB 1_IL | 32.23 | 18.49 | 4.09 | 2.21 | 28.14 ± 0.67 | 16.28 ± 0.25 |

| CB 3 | 34.01 | 21.83 | 4.42 | 4.43 | 29.59 ± 0.62 | 17.40 ± 0.42 |

| CB 3_IL | 34.23 | 19.04 | 4.48 | 2.43 | 29.75 ± 0.41 | 16.61 ± 0.06 |

| CB 5 | 34.49 | 21.63 | 3.75 | 3.39 | 30.74 ± 0.73 | 18.24 ± 0.37 |

| CB 5_IL | 34.11 | 20.47 | 3.75 | 3.08 | 30.36 ± 0.69 | 17.39 ± 0.27 |

| Sample’s Name | K, kPas | n, - | r2 | η* at 300 s−1, Pas |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| reference | 53.61 | −0.736 | 0.992 | 646.3 |

| G 1 | 56.83 | −0.739 | 0.998 | 656.0 |

| G 1_IL | 59.02 | −0.748 | 0.991 | 654.9 |

| G 3 | 58.49 | −0.745 | 0.992 | 654.3 |

| G 3_IL | 59.39 | −0.752 | 0.993 | 644.0 |

| G 5 | 63.90 | −0.753 | 0.993 | 687.1 |

| G 5_IL | 56.40 | −0.763 | 0.997 | 576.2 |

| CB 1 | 54.53 | −0.738 | 0.990 | 641.9 |

| CB 1_IL | 61.09 | −0.751 | 0.994 | 667.1 |

| CB 3 | 57.85 | −0.745 | 0.992 | 662.4 |

| CB 3_IL | 58.23 | −0.748 | 0.993 | 626.7 |

| CB 5 | 59.09 | −0.745 | 0.991 | 665.0 |

| CB 5_IL | 50.00 | −0.730 | 0.998 | 588.9 |

| Sample’s Name | G′LVR, kPa | G′„ LVR, kPa | tanδ LVR, kPa |

|---|---|---|---|

| reference | 66.13 ± 2.21 | 49.83 ± 0.93 | 0.75 ± 0.03 |

| G 1 | 70.97 ± 1.97 | 52.32 ± 1.10 | 0.74 ± 0.02 |

| G 1_IL | 76.37 ± 1.56 | 52.70 ± 0.26 | 0.69 ± 0.01 |

| G 3 | 78.56 ± 1.73 | 55.74 ± 0.90 | 0.71 ± 0.01 |

| G 3_IL | 82.49 ± 1.66 | 59.09 ± 1.85 | 0.72 ± 0.03 |

| G 5 | 82.67 ± 2.21 | 59.63 ± 0.80 | 0.72 ± 0.02 |

| G 5_IL | 87.94 ± 1.78 | 59.39 ± 0.26 | 0.68 ± 0.01 |

| CB 1 | 68.87 ± 2.28 | 52.10 ± 0.91 | 0.76 ± 0.03 |

| CB 1_IL | 72.08 ± 2.38 | 51.14 ± 0.79 | 0.71 ± 0.02 |

| CB 3 | 75.16 ± 1.94 | 54.68 ± 1.33 | 0.73 ± 0.02 |

| CB 3_IL | 77.54 ± 1.58 | 52.17 ± 0.18 | 0.67 ± 0.01 |

| CB 5 | 77.73 ± 2.45 | 57.29 ± 1.15 | 0.74 ± 0.02 |

| CB 5_IL | 78.19 ± 2.24 | 54.63 ± 0.85 | 0.70 ± 0.02 |

| T. °C | CB 5 | CB 5_IL | ||||||||||

| CRmax | t, s | K × 10−4 | n | r2 | Ea kJ Mole−1 | CRmax | t, s | K × 10−4 | n | r2 | Ea kJ Mole−1 | |

| 160 | 1.115 | 31.2 | 0.384 | 1.78 | 0.9901 | 75.78 | 0.72 | 26.4 | 0.798 | 1.58 | 0.9973 | 169.08 |

| 165 | 1.555 | 26.4 | 0.517 | 1.82 | 0.9913 | 1.07 | 22.8 | 1.676 | 1.52 | 0.9988 | ||

| 170 | 2.048 | 26.9 | 0.679 | 1.87 | 0.9905 | 1.43 | 23.4 | 3.187 | 1.49 | 0.9998 | ||

| 175 | 2.836 | 22.8 | 0.753 | 1.96 | 0.9923 | 1.80 | 20.4 | 4.568 | 1.49 | 0.9998 | ||

| 180 | 3.613 | 19.8 | 1.016 | 2.03 | 0.9958 | 2.39 | 17.4 | 6.418 | 1.50 | 0.9995 | ||

| T. °C | G 5 | G 5_IL | ||||||||||

| CRmax | t. s | K × 10−4 | n | r2 | Ea. kJ Mole−1 | CRmax | t. s | K × 10−4 | n | r2 | Ea. kJ Mole−1 | |

| 160 | 0.743 | 27.6 | 0.890 | 1.58 | 0.9970 | 128.61 | 0.479 | 30.5 | 0.188 | 1.75 | 0.9942 | 212.95 |

| 165 | 0.981 | 27.0 | 1.131 | 1.58 | 0.9977 | 0.635 | 28.0 | 0.236 | 1.81 | 0.9993 | ||

| 170 | 1.404 | 24.0 | 1.907 | 1.59 | 0.9989 | 0.917 | 25.2 | 0.747 | 1.67 | 0.9962 | ||

| 175 | 1.860 | 23.9 | 2.581 | 1.61 | 0.9995 | 1.181 | 21.6 | 1.134 | 1.66 | 0.9974 | ||

| 180 | 2.539 | 18.6 | 4.239 | 1.61 | 0.9997 | 1.622 | 18.5 | 2.248 | 1.63 | 0.9940 | ||

| Sample’s Name | SE300/SE100, - | RITS, % | Sample’s Name | SE300/SE100, - | RITS, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CB 1 | 2.23 | 1.3 | G 1 | 1.97 | 1.2 |

| CB 1_IL | 2.05 | 1.3 | G1_IL | 2.45 | 1.3 |

| CB 3 | 2.11 | 5.1 | G 3 | 1.97 | 4.9 |

| CB 3_IL | 2.10 | 4.3 | G 3_IL | 1.90 | 4.1 |

| CB 5 | 2.30 | 9.9 | G 5 | 2.20 | 9.1 |

| CB 5_IL | 1.84 | 6.9 | G 5_IL | 2.22 | 10.8 |

| SBR Composites | G 5 | G 5_IL | CB 5 | CB 5_IL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X, μm | %Number | %Number | %Number | %Number | |

| <1 | 96.4 | 95.7 | 96.7 | 97.6 | |

| 1 < x < 1.5 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 0.7 | |

| 1.5 < x < 2 | 0.6 | 0.59 | 0.7 | 0.5 | |

| x > 2 | 2.5 | 2.9 | 1.4 | 1.1 | |

| LA | 13.4 | 5.8 | 9.1 | 3.2 | |

| Sample’s Name | RB % | Sample’s Name | RB % |

|---|---|---|---|

| CB 1 | 3.09 | G 1 | 5.44 |

| CB 1_IL | 3.66 | G1_IL | 5.92 |

| CB 3 | 3.98 | G 3 | 2.90 |

| CB 3_IL | 2.85 | G 3_IL | 3.46 |

| CB 5 | 4.15 | G 5 | 3.65 |

| CB 5_IL | 1.06 | G 5_IL | 4.17 |

| Sample’s Name | G′LVR, kPa | G′„LVR, kPa | G* LVR, kPa | RIG*, - |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| reference | 116.99 ± 0.53 | 13.14 ± 0.07 | 117.73 ± 0.52 | n.a |

| CB 1 | 165.08 ± 1.18 | 17.67 ± 0.07 | 166.02 ± 1.17 | 0.014 |

| CB 1_IL | 148.91 ± 1.71 | 16.39 ± 0.16 | 149.81 ± 1.72 | 0.013 |

| CB 3 | 149.70 ± 2.20 | 16.59 ± 0.16 | 150.61 ± 2.20 | 0.038 |

| CB 3_IL | 142.78 ± 1.74 | 16.32 ± 0.07 | 143.71 ± 1.73 | 0.037 |

| CB 5 | 372.86 ± 1.80 | 47.54 ± 0.38 | 375.87 ± 1.78 | 0.160 |

| CB 5_IL | 297.57 ± 4.27 | 32.71 ± 0.19 | 299.36 ± 4.25 | 0.127 |

| Sample’s Name | G′LVR, kPa | G′„LVR, kPa | G* LVR, kPa | RIG*, - |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| reference | 116.99 ± 0.53 | 13.14 ± 0.07 | 117.73 ± 0.52 | n.a. |

| G 1 | 153.62 ± 1.95 | 18.86 ± 0.09 | 154.78 ± 1.94 | 0.013 |

| G 1_IL | 127.15 ± 1.09 | 12.81 ± 0.18 | 127.79 ± 1.07 | 0.011 |

| G 3 | 161.99 ± 0.28 | 17.76 ± 0.14 | 162.96 ± 0.28 | 0.042 |

| G 3_IL | 195.90 ± 1.63 | 23.26 ± 0.08 | 197.28 ± 1.62 | 0.050 |

| G 5 | 420.60 ± 2.74 | 52.66 ± 0.40 | 423.89 ± 2.67 | 0.180 |

| G 5_IL | 226.48 ± 1.53 | 25.57 ± 0.04 | 227.92 ± 1.53 | 0.097 |

| Sample’s Name | ΔG*5%, kPa | ΔG*20%, kPa | ΔG*50%, kPa | ΔG*LVR, kPa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| reference | 25.95 | 47.85 | 52.54 | 6.10 |

| CB 1 | 27.24 | 53.18 | 96.42 | 42.91 |

| CB 1_IL | 25.02 | 55.77 | 64.62 | 49.38 |

| CB 3 | 19.74 | 46.85 | 67.38 | 32.92 |

| CB 3_IL | 47.82 | 88.29 | 107.44 | 44.96 |

| CB 5 | 95.8 | 205.07 | 262.26 | 283.15 |

| CB 5_IL | 93.28 | 175.1 | 205.49 | 195.23 |

| Sample’s Name | ΔG*5%, kPa | ΔG*20%, kPa | ΔG*50%, kPa | ΔG*LVR, kPa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| reference | 25.95 | 47.85 | 52.54 | 6.10 |

| G 1 | 53.17 | 84.19 | 114.46 | 50.41 |

| G 1_IL | 60.19 | 76.40 | 94.50 | 14.89 |

| G 3 | 7.54 | 31.46 | 59.86 | 107.06 |

| G 3_IL | 37.69 | 68.49 | 108.33 | 97.91 |

| G 5 | 104.80 | 281.12 | 357.81 | 239.01 |

| G 5_IL | 39.14 | 70.39 | 117.85 | 127.04 |

| Sample’s Name | Tg, °C | tanδTg, - |

|---|---|---|

| reference | −39.8 | 1.77 |

| CB 3 | −39.3 | 1.61 |

| CB 3_IL | −39.4 | 1.68 |

| CB 5 | −38.9 | 1.64 |

| CB 5_IL | −41.2 | 1.53 |

| G 3 | −38.6 | 1.70 |

| G 3_IL | −39.4 | 1.86 |

| G 5 | −38.6 | 1.68 |

| G 5_IL | −38.3 | 1.72 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gaca, M.; Lipińska, M. Elastic Composites Containing Carbonous Fillers Functionalized by Ionic Liquid: Viscoelastic Properties. Polymers 2025, 17, 3271. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243271

Gaca M, Lipińska M. Elastic Composites Containing Carbonous Fillers Functionalized by Ionic Liquid: Viscoelastic Properties. Polymers. 2025; 17(24):3271. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243271

Chicago/Turabian StyleGaca, Magdalena, and Magdalena Lipińska. 2025. "Elastic Composites Containing Carbonous Fillers Functionalized by Ionic Liquid: Viscoelastic Properties" Polymers 17, no. 24: 3271. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243271

APA StyleGaca, M., & Lipińska, M. (2025). Elastic Composites Containing Carbonous Fillers Functionalized by Ionic Liquid: Viscoelastic Properties. Polymers, 17(24), 3271. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243271