Orientation and Influence of Anisotropic Nanoparticles in Electroconductive Thermoplastic Composites: A Micromechanical Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material

2.2. Material Extrusion and Filament Production

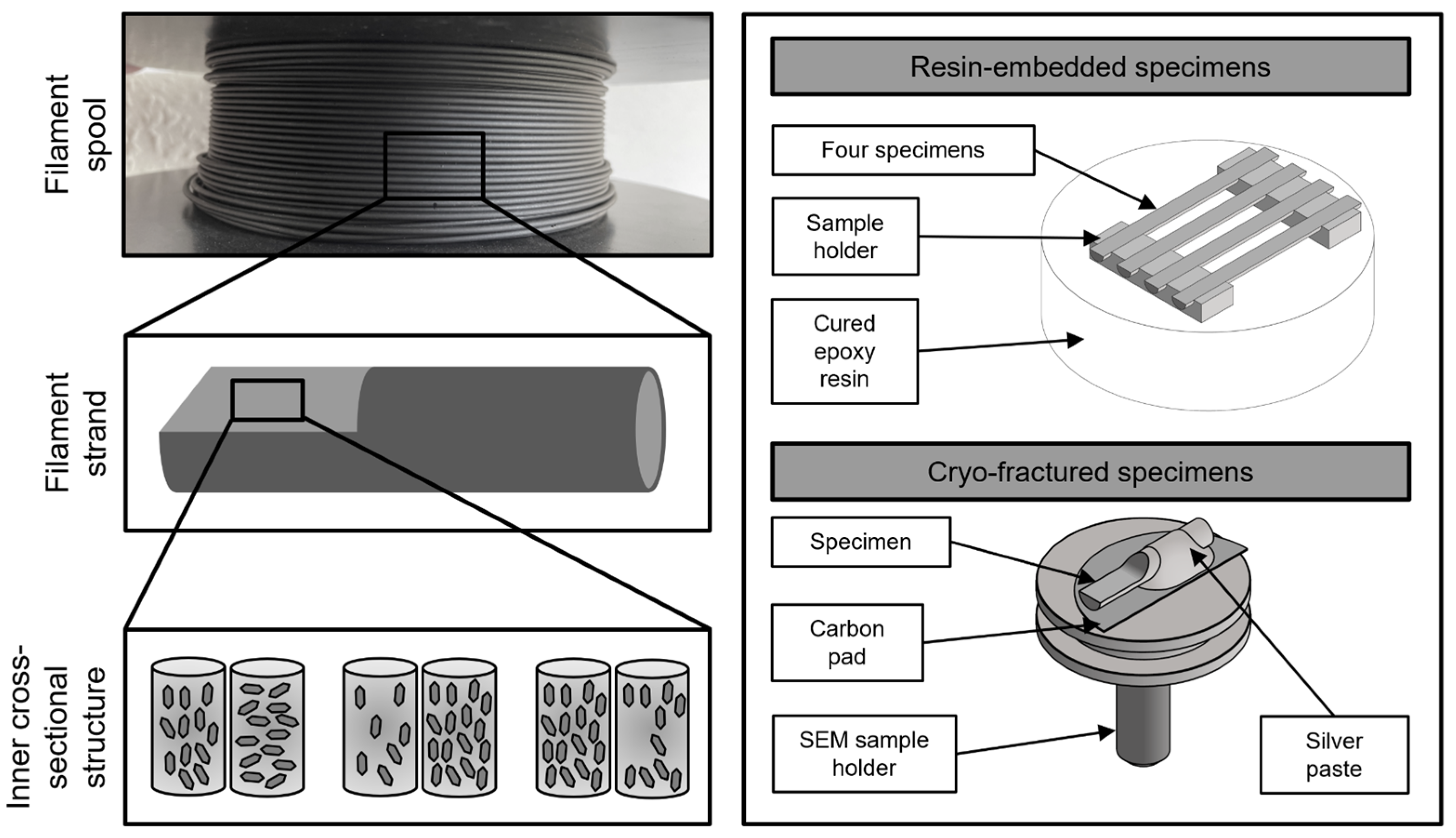

2.3. Sample Preparation

2.4. FT-IR and TGA

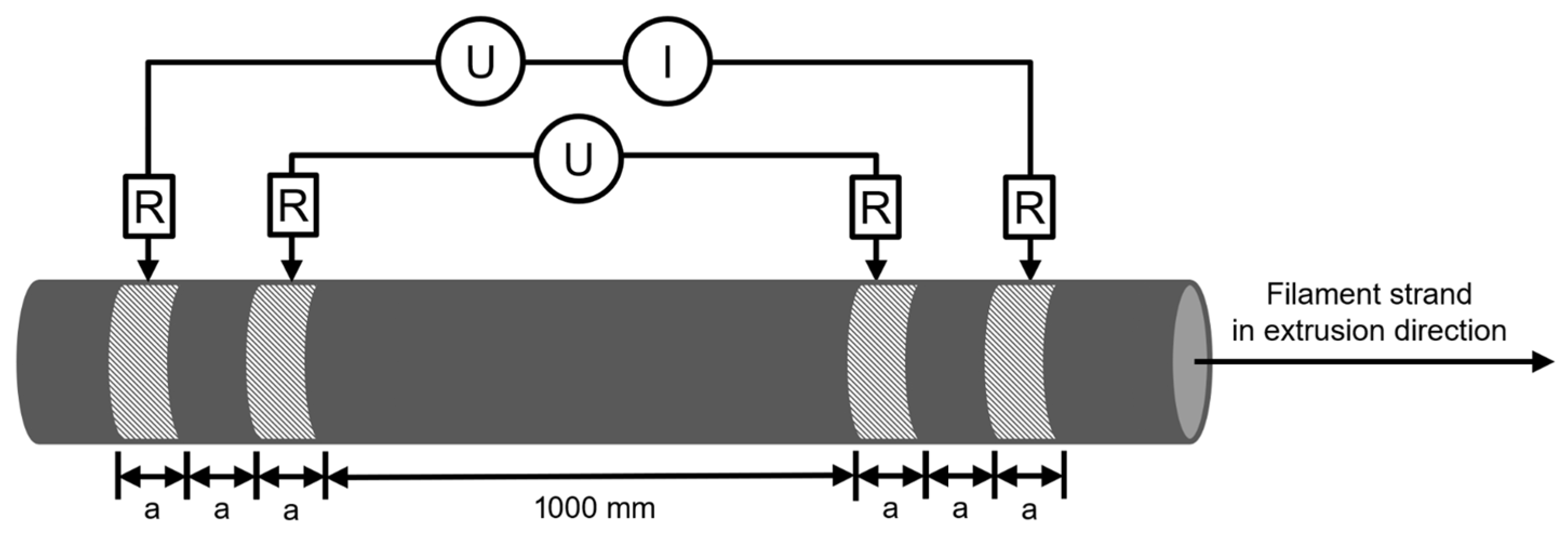

2.5. Electrical Resistivity of Filament Specimens

2.6. Microstructural Analysis: Methodological Approach to Reveal Particle Orientation and Distribution in the Composite

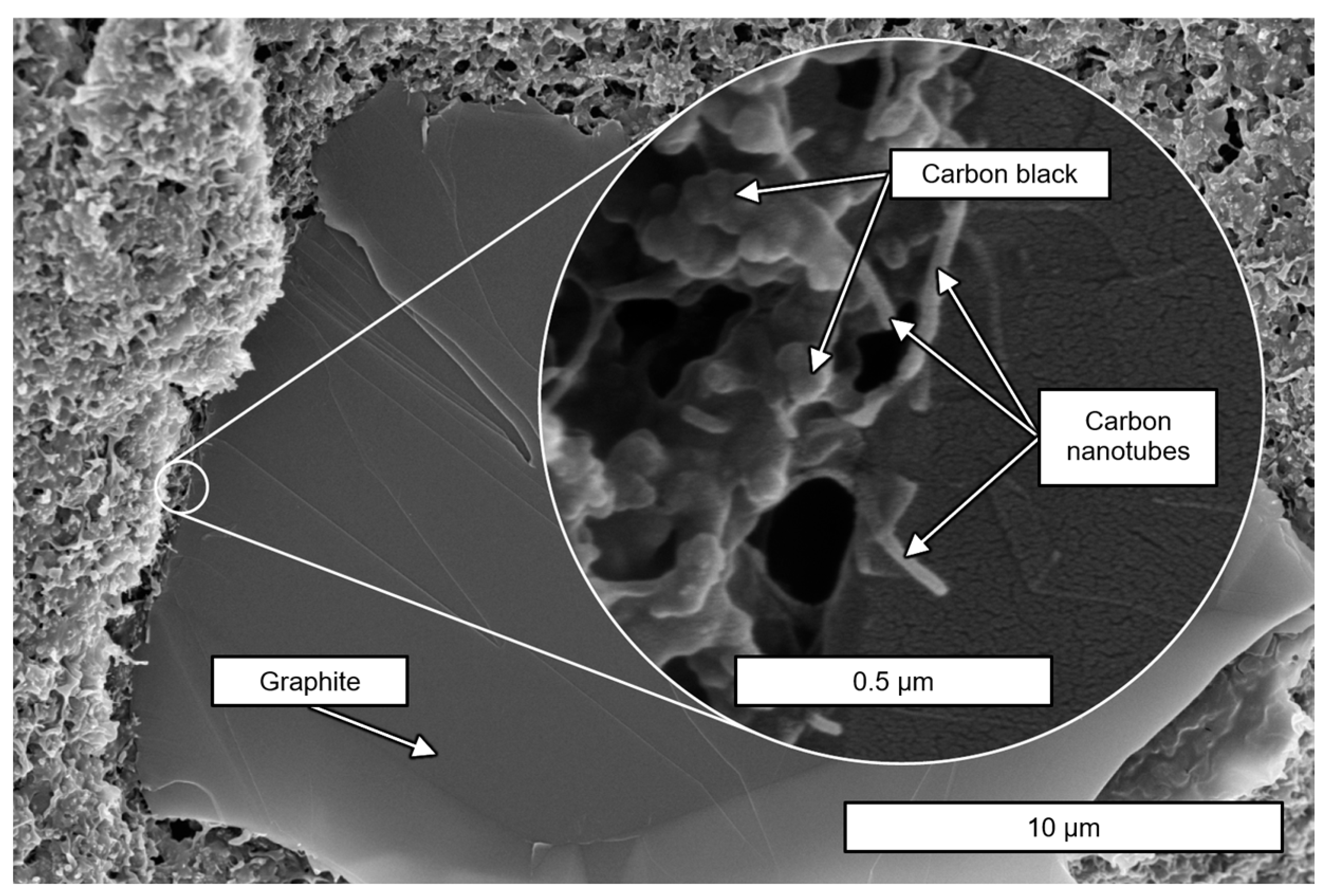

2.6.1. Imaging Methods

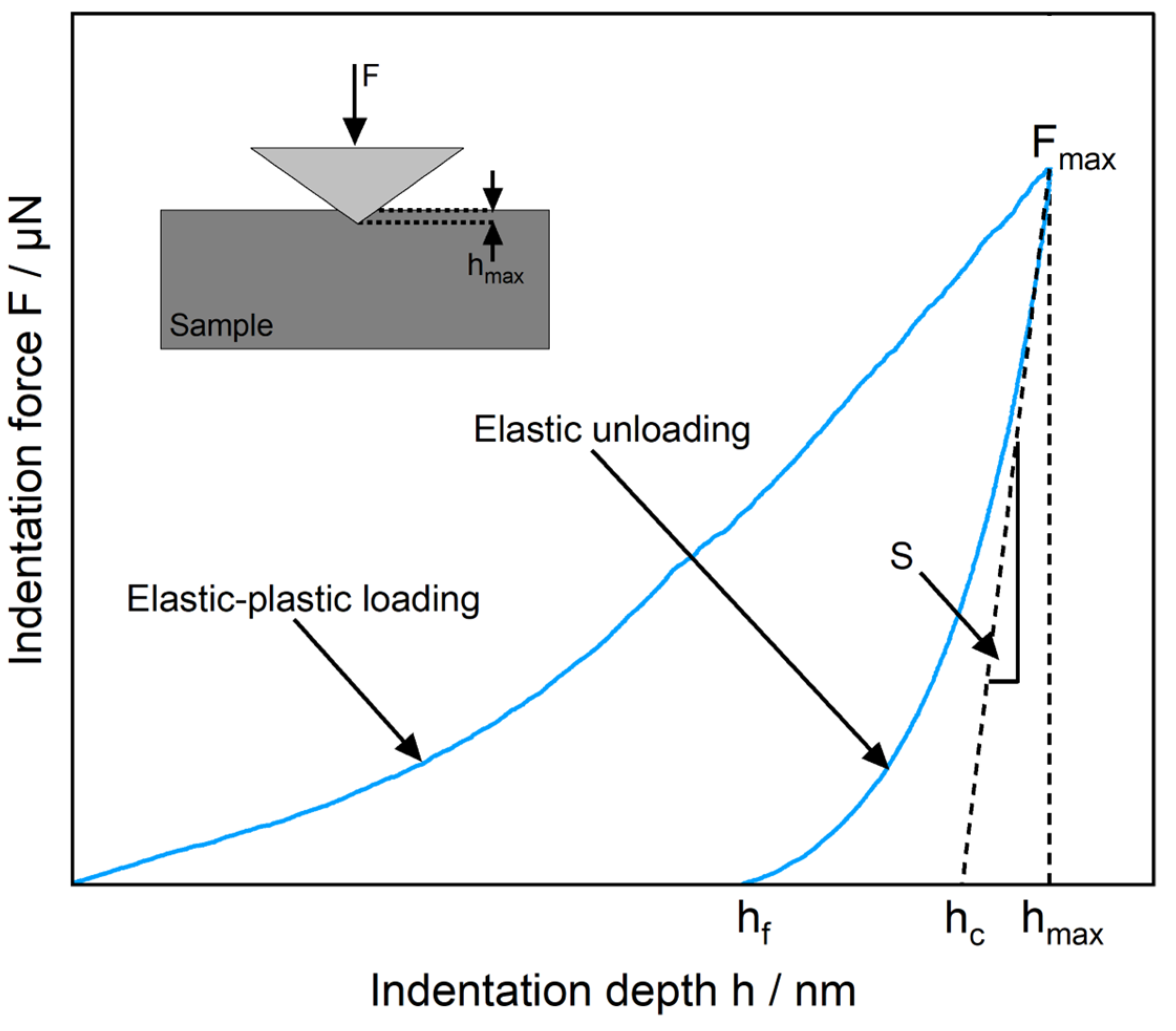

2.6.2. Micromechanical Surface Properties

3. Results and Discussion

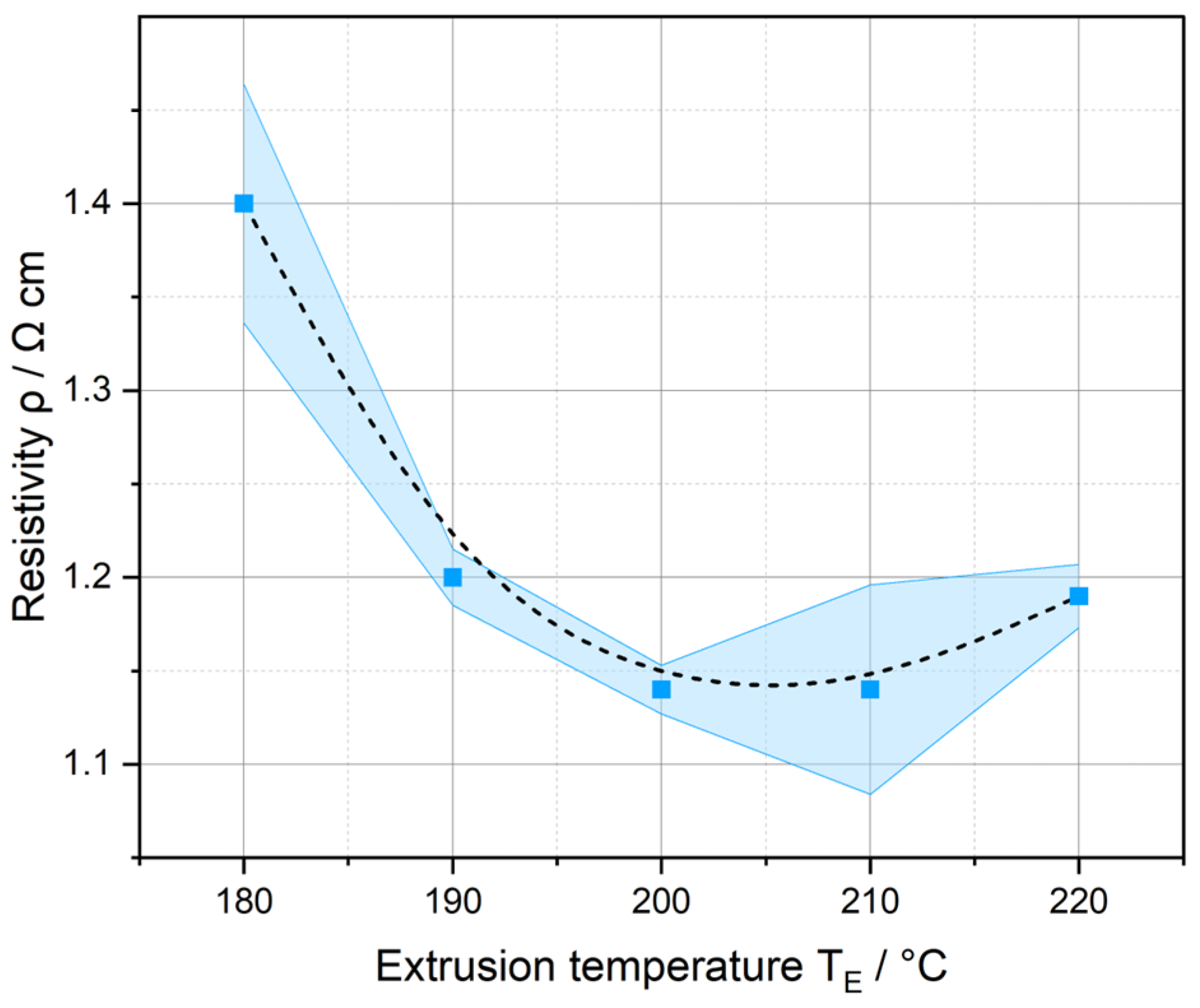

3.1. Influence of the Extrusion Temperature Profile on the Electrical Resistivity

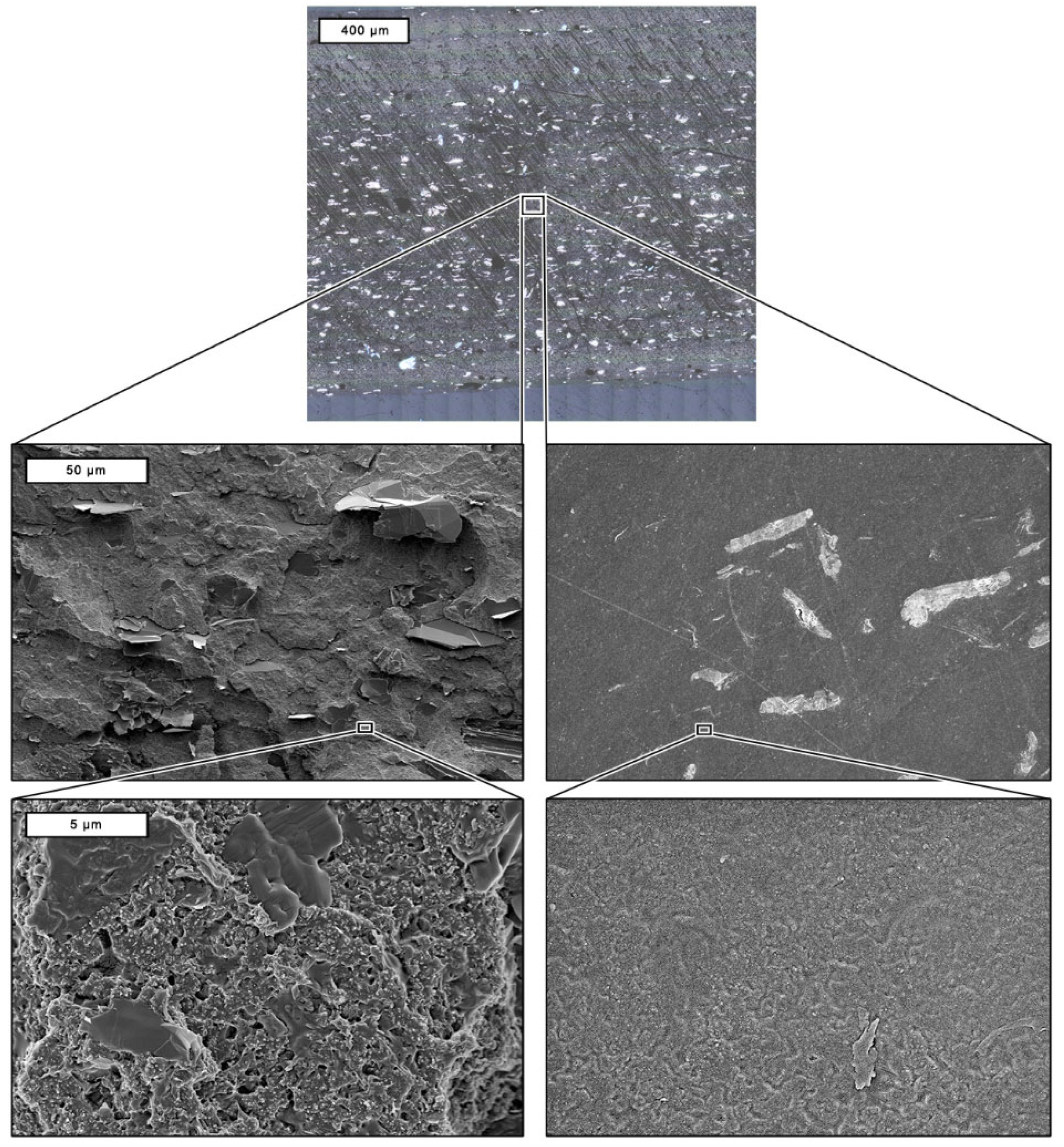

3.2. Microscopic Investigation of the Internal Composite Structure

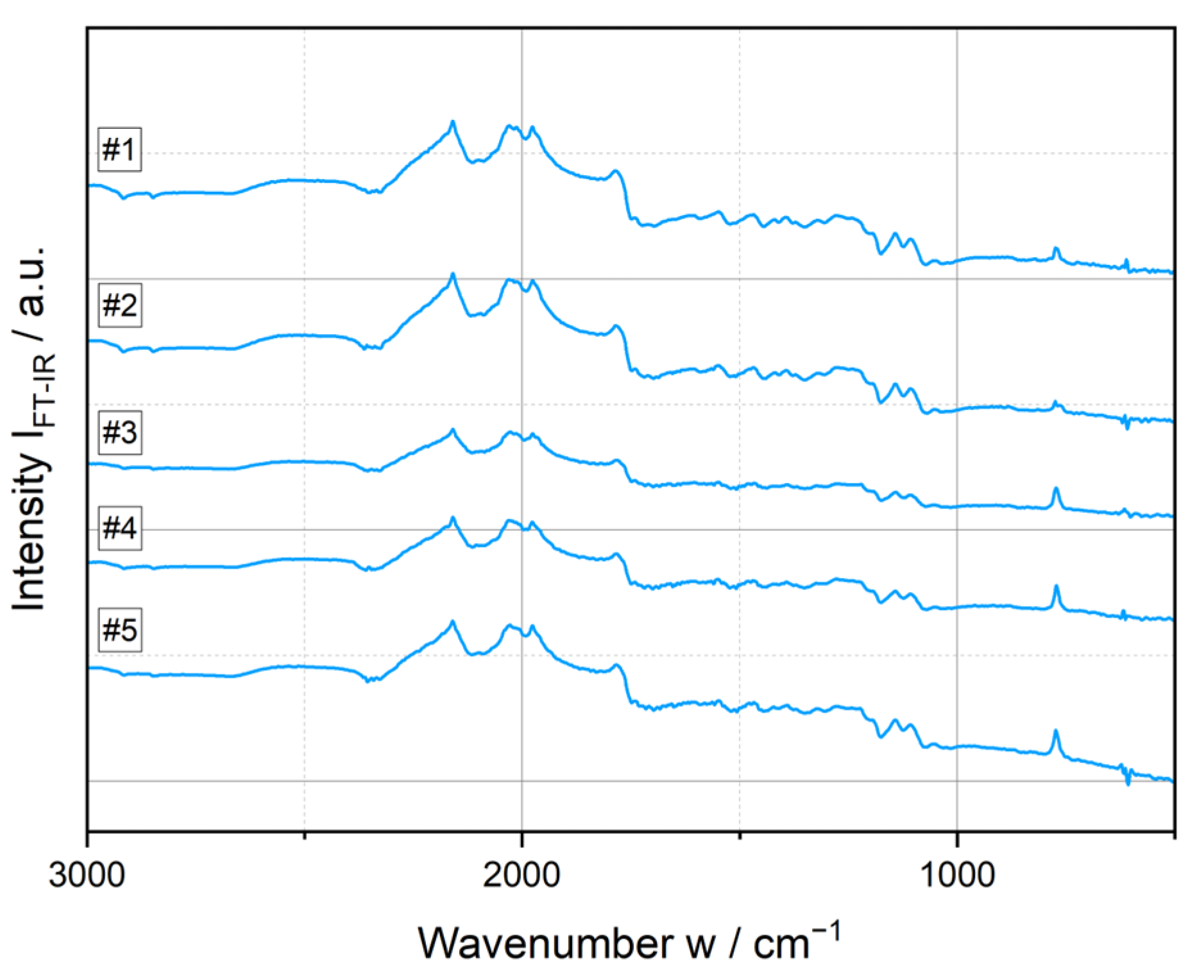

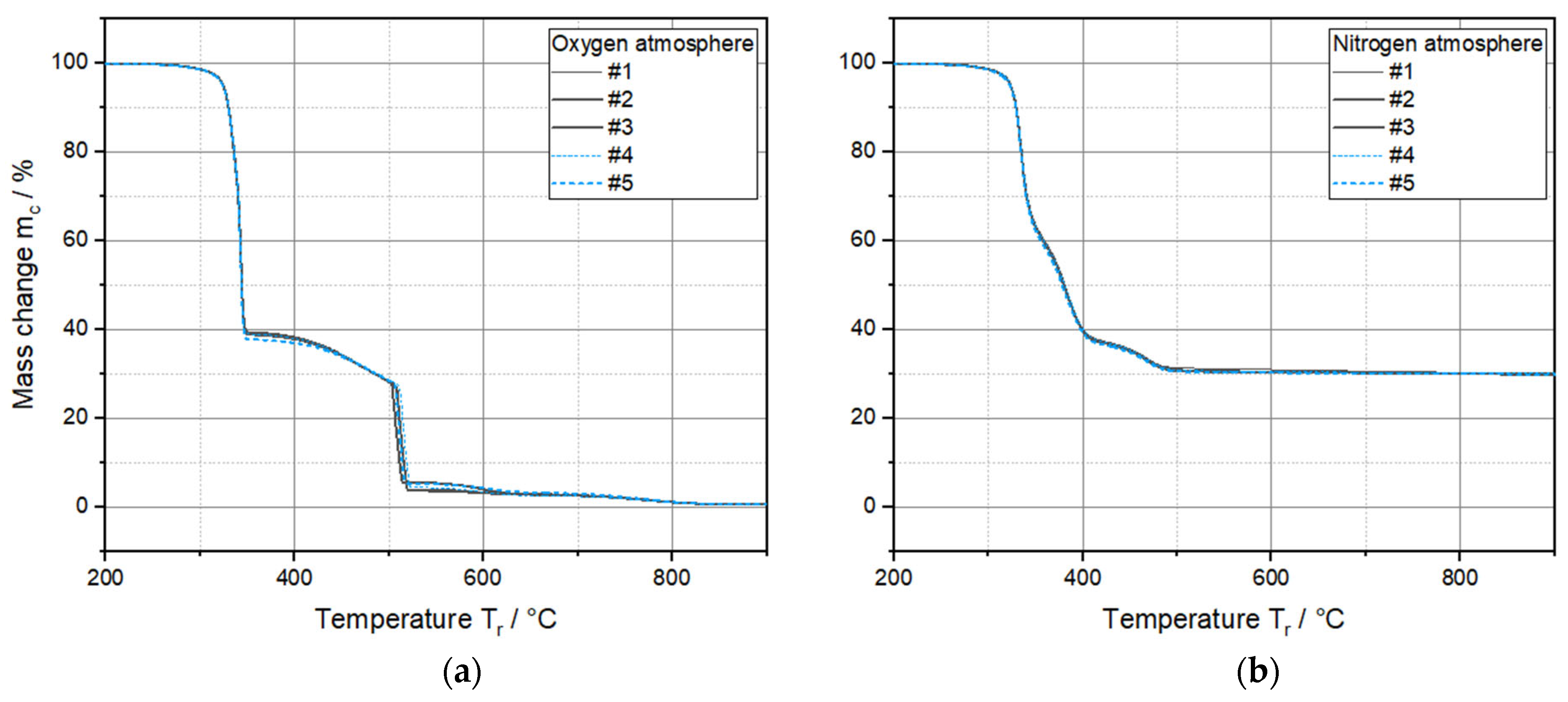

3.3. Chemical Composition and Thermal Stability

3.4. Nanomechanical Investigation of the Internal Composite Structure

3.4.1. Methodical Approach of Nanoindentation Mapping and Influence of Particulate Content

3.4.2. Influence of the Extrusion Temperature

3.4.3. Structural Composition Inside the Filament as a Result of the Hot Melt Extrusion Process

4. Conclusions and Outlook

- established a high-resolution micromechanical mapping method for anisotropic polymer composites;

- demonstrated that even small changes in extrusion temperature significantly affect filler orientation and dispersion;

- revealed local structural gradients and edge effects that are not accessible via global measurements such as electrical resistivity;

- showed that combining nanoindentation with microscopy enables a robust framework for analyzing process-structure-property relationships in conductive polymer systems.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABS | Acrylonitrile butadiene styrene | |

| AM | Additive manufacturing | |

| CB | Carbon black | |

| CCVD | Catalytic chemical vapor deposition | |

| CNC | Cationic cellulose nanocrystals | |

| CNT | Carbon nanotube | |

| FEM | Finite Element Method | |

| FFF | Fused Filament Fabrication | |

| FGF | Fused Granulate Fabrication | |

| FT-IR | Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy | |

| GNP | Graphene nanoplatelet | |

| GO | Graphene oxide | |

| Gr | Graphite | |

| HME | Hot Melt Extrusion | |

| MEX | Material Extrusion | |

| NIR | Near-Infrared | |

| PEEK | Polyetheretherketone | |

| PLA | Poly(lactic acid) | |

| PVDF | Polyvinylidene fluoride | |

| SD | Standard deviation | |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy | |

| SSE | Single screw extrusion | |

| TGA | Thermogravimetric analysis | |

| US | Ultrasonic | |

| Symbols | ||

| A | Projected contact area | µm2 |

| a | Contact distance | mm |

| d | Indentation spacing | µm |

| Er | Reduced elastic modulus | GPa |

| P | Indentation force | µN |

| H | Hardness | GPa |

| h | Indentation depth | nm |

| hf | Remaining indentation depth | nm |

| hmax | Maximum indentation depth | nm |

| I | Current | A |

| IFT-IR | Intensity | - |

| mc | Mass change | % |

| P | Indentation load | µN |

| Pmax | Peak indentation load | µN |

| R | Resistance | Ω |

| S | Contact stiffness | N mm−1 |

| ß | Geometric constant | - |

| TE | Extrusion temperature | °C |

| Tr | Actual temperature | °C |

| U | Voltage | V |

| w | Wavenumber | cm−1 |

| ρ | Resistivity | Ωcm |

References

- Huang, P.; Xia, Z.; Cui, S. 3D printing of carbon fiber-filled conductive silicon rubber. Mater. Des. 2018, 142, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Luan, C.; Liao, G.; Yao, X.; Fu, J. Mechanical and self-monitoring behaviors of 3D printing smart continuous carbon fiber-thermoplastic lattice truss sandwich structure. Compos. Part B Eng. 2019, 176, 107215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watschke, H.; Hilbig, K.; Vietor, T. Design and characterization of electrically conductive structures additively manufactured by material extrusion. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goutier, M.; Hilbig, K.; Vietor, T.; Böl, M. Process Parameters and Geometry Effects on Piezoresistivity in Additively Manufactured Polymer Sensors. Polymers 2023, 15, 2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heitkamp, T.; Goutier, M.; Hilbig, K.; Girnth, S.; Waldt, N.; Klawitter, G.; Vietor, T. Parametric study of piezoresistive structures in continuous fiber reinforced additive manufacturing. Compos. Part C Open Access 2024, 13, 100431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.; Howard, D.; Zhang, F.; Leng, J.; Wang, C.H. Direct 3D Printing of Highly Anisotropic, Flexible, Constriction-Resistive Sensors for Multidirectional Proprioception in Soft Robots. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 15631–15643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgeneidy, K.; Neumann, G.; Jackson, M.; Lohse, N. Directly Printable Flexible Strain Sensors for Bending and Contact Feedback of Soft Actuators. Front. Robot. AI 2018, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christ, J.F.; Aliheidari, N.; Pötschke, P.; Ameli, A. Bidirectional and Stretchable Piezoresistive Sensors Enabled by Multimaterial 3D Printing of Carbon Nanotube/Thermoplastic Polyurethane Nanocomposites. Polymers 2019, 11, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohimer, C.J.; Petrossian, G.; Ameli, A.; Mo, C.; Pötschke, P. 3D printed conductive thermoplastic polyurethane/carbon nanotube composites for capacitive and piezoresistive sensing in soft pneumatic actuators. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 34, 101281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, S.W.; Goh, K.H.; Tan, Z.D.; Tan, S.T.; Tjiu, W.W.; Soh, J.Y.; Ng, Z.J.; Chan, Y.Z.; Hui, H.K.; Goh, K.E. Electrically conductive filament for 3D-printed circuits and sensors. Appl. Mater. Today 2017, 9, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sam-Daliri, O.; Kelly, C.; Walls, M.; Flanagan, T.; Finnegan, W.; Harrison, N.M.; Ghabezi, P. Carbon nanotubes–Elium nanocomposite sensor for structural health monitoring of unidirectional glass fibre reinforced epoxy composite. Compos. Commun. 2025, 58, 102503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilbig, K.; Nowka, M.; Redeker, J.; Watschke, H.; Friesen, V.; Duden, A.; Vietor, T. Data-driven design support for additively manufactured heating elements. Proc. Des. Soc. 2022, 2, 1391–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Lee, S. Characterization of electrical heating of graphene/PLA honeycomb structure composite manufactured by CFDM 3D printer. Fash. Text. 2020, 7, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowka, M.; Hilbig, K.; Schulze, L.; Jung, E.; Vietor, T. Influence of process parameters in material extrusion on product properties using the example of the electrical resistivity of conductive polymer composites. Polymers 2023, 15, 4452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, E.; Salas, R.; Espalin, D.; Perez, M.; Aguilera, E.; Muse, D.; Wicker, R.B. 3D Printing for the Rapid Prototyping of Structural Electronics. IEEE Access 2014, 2, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, J.M.; Sauti, G.; Kim, J.-W.; Cano, R.J.; Wincheski, R.A.; Stelter, C.J.; Grimsley, B.W.; Working, D.C.; Siochi, E.J. 3-D printing of multifunctional carbon nanotube yarn reinforced components. Addit. Manuf. 2016, 12, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yang, B.; Fu, F.; You, F.; Dong, X.; Dai, M. Resistivity and its anisotropy characterization of 3D-printed acrylonitrile butadiene styrene copolymer (abs)/carbon black (CB) composites. Appl. Sci. 2017, 7, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flowers, P.F.; Reyes, C.; Ye, S.; Kim, M.J.; Wiley, B.J. 3D printing electronic components and circuits with conductive thermoplastic filament. Addit. Manuf. 2017, 18, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampel, B.; Monshausen, S.; Schilling, M. Properties and applications of electrically conductive thermoplastics for additive manufacturing of sensors. Tm-Tech. Mess. 2017, 84, 593–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassar, H.; Dahiya, R. Fused deposition modeling-based 3d-printed electrical interconnects and Circuits. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2021, 3, 2100102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.-Y.; Yang, C.; Hsu, W.; Lin, L. RF wireless lc tank sensors fabricated by 3D additive manufacturing. In Proceedings of the 2015 Transducers—2015 18th International Conference on Solid-State Sensors, Actuators and Microsystems (TRANSDUCERS), Anchorage, AK, USA, 21–25 June 2015; pp. 2208–2211. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, N.; Bedair, S.S. Creating 3D printed sensor systems with conductive composites. Smart Mater. Struct. 2020, 30, 15020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankevich, S.; Sevcenko, J.; Bulderberga, O.; Dutovs, A.; Erts, D.; Piskunovs, M.; Ivanovs, V.; Ivanov, V.; Aniskevich, A. Electrical Resistivity of 3D-Printed Polymer Elements. Polymers 2023, 15, 2988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aloqalaa, Z. Electrically Conductive Fused Deposition Modeling Filaments: Current Status and Medical Applications. Crystals 2022, 12, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsiadły, B.; Skalski, A.; Wałpuski, B.; Słoma, M. Heterophase materials for fused filament fabrication of structural electronics. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2018, 30, 1236–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Jain, P.K.; Tandon, P.; Pandey, P.M. Additive manufacturing of flexible electrically conductive polymer composites via CNC-assisted fused layer modeling process. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2018, 40, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajpai, A.; Jain, P.K. Investigation on 3Dprinting of graphene multi-walled carbon nanotube mixed flexible electrically conductive parts using fused filament fabrication. J. Mater. Eng Perform 2022, 32, 6319–6328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinelli, G.; Kotsilkova, R.; Ivanov, E.; Petrova-Doycheva, I.; Menseidov, D.; Georgiev, V.; Di Maio, R.; Silvestre, C. Effects of filament extrusion, 3D printing and hot-pressing on electrical and tensile properties of poly(lactic) acid composites filled with carbon nanotubes and graphene. Nanomaterials 2019, 10, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembek, K.; Podsiadły, B.; Słoma, M. Influence of process parameters on the resistivity of 3D printed electrically conductive structures. Micromachines 2022, 13, 1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truman, L.; Whitwam, E.; Nelson-Cheeseman, B.B.; Koerner, L.J. Conductive 3Dprinting: Resistivity dependence upon infill pattern application to EMIshielding. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2020, 31, 14108–14117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Meisel, N.A. Exploring the Manufacturability and Resistivity of Conductive Filament Used in Material Extrusion Additive Manufacturing; University of Texas at Austin: Austin, TX, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Glogowsky, A.; Korger, M.; Rabe, M. Influence of print settings on conductivity of 3D printed elastomers with carbon-based fillers. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 9, 791–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanatgar, R.H.; Cayla, A.; Campagne, C.; Nierstrasz, V. Morphological and electrical characterization of conductive polylactic acid based nanocomposite before and after FDM 3D printing. Inc. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2019, 136, 47040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunz, K.; Krause, B.; Kretzschmar, B.; Juhasz, L.; Kobsch, O.; Jenschke, W.; Ullrich, M.; Pötschke, P. Direction Dependent Electrical Conductivity of Polymer/Carbon Filler Composites. Polymers 2019, 11, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez, O.U.; Besharatloo, H.; Yus, J.; Sanchez-Herencia, A.J.; Ferrari, B. Material thermal extrusion of conductive 3D electrodes using highly loaded graphene and graphite colloidal feedstock. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 72, 103643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galos, J.; Hu, Y.; Ravindran, A.R.; Ladani, R.B.; Mouritz, A.P. Electrical properties of 3D printed continuous carbon fibre composites made using the FDM process. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2021, 151, 106661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patanwala, H.; Hong, D.; Vora, S.; Bognet, B.; Ma, A. The microstructure and mechanical properties of 3D printed carbon nanotube-polylactic acid composites. Polym. Compos. 2017, 39, 1060–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, A.; Hamzah, H.H.; Keattch, O.; Covill, D.; Patel, B.A. Augmentation of conductive pathways in carbon black/PLA 3D-printed electrodes achieved through varying printing parameters. Electrochim. Acta 2020, 354, 136618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolterink, G.; Sanders, R.; Krijnen, G. Thin, Flexible, Capacitive Force Sensors Based on Anisotropy in 3D-Printed Structures. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE SENSORS, New Delhi, India, 28–31 October 2018; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves, J.; Lima, P.; Krause, B.; Pötschke, P.; Lafont, U.; Gomes, J.R.; Abreu, C.S.; Paiva, M.C.; Covas, J.A. Electrically Conductive Polyetheretherketone Nanocomposite Filaments: From Production to Fused Deposition Modeling. Polymers 2018, 10, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz, R.; Moriche, R.; Monzón, M.; García, J. Influence of manufacturing parameters and post processing on the electrical conductivity of extrusion-based 3D printed nanocomposite parts. Polymers 2020, 12, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shante, V.K.; Kirkpatrick, S. An introduction to percolation theory. Adv. Phys. 1971, 20, 325–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaynan, O.; Yıldız, A.; Bozkurt, Y.E.; Yenigun, E.O.; Cebeci, H. Electrically conductive high-performance thermoplastic filaments for fused filament fabrication. Compos. Struct. 2020, 237, 111930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wockel, S.; Arndt, H.; Steinmann, U.; Auge, J.; Dietl, K.; Schober, G.; Kugler, C.; Hochrein, T. Statistical ultrasonic characterization of particulate filler in polymer compounds. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium (IUS), Tours, France, 18–21 September 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Alig, I.; Fischer, D.; Lellinger, D.; Steinhoff, B. Combination of NIR, Raman, Ultrasonic and Dielectric Spectroscopy for In-Line Monitoring of the Extrusion Process. Macromol. Symp. 2005, 230, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alig, I.; Steinhoff, B.; Lellinger, D. Monitoring of polymer melt processing. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2010, 21, 62001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbie, E.K.; Migler, K.B.; Han, C.C.; Amis, E.J. Light scattering and optical microscopy as in-line probes of polymer blend extrusion. Adv. Polym. Technol. 1998, 17, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, D.; Yoon, H.N.; Seo, J.; Park, S.; Kil, T.; Lee, H.K. Improved electric heating characteristics of CNT-embedded polymeric composites with an addition of silica aerogel. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2021, 212, 108866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.-X.; Zhao, M.-L.; Zhang, G.-Z.; Song, J.; Qu, J.-P. Controlled localizing multi-wall carbon nanotubes in polyvinylidene fluoride/acrylonitrile butadiene styrene blends to achieve balanced dielectric constant and dielectric loss. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2021, 212, 108874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Ketterle, L.; Järvinen, T.; Lorite, G.S.; Hong, S.; Liimatainen, H. Self-assembly of graphene oxide and cellulose nanocrystals into continuous filament via interfacial nanoparticle complexation. Mater. Des. 2020, 193, 108791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bories, M.; Huneault, M.A.; Lafleur, P.G. Effect of Twin-Screw Extruder Design Process Conditions on Ultrafine CaCO3 Dispersion into PP. Int. Polym. Process. 1999, 14, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatibouët, J.; Huneault, M.A. In-line Ultrasonic Monitoring of Filler Dispersion during Extrusion. Int. Polym. Process. 2002, 17, 49–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krumbholz, N.; Hochrein, T.; Vieweg, N.; Radovanovic, I.; Pupeza, I.; Schubert, M.; Kretschmer, K.; Koch, M. Degree of dispersion of polymeric compounds determined with terahertz time-domain spectroscopy. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2011, 51, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, F.; Nairn, J.; Muszyński, L. An experimental method for measurement of strain distribution between wood the flour particles and polymer matrix on micro-mechanical level. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2011, 528, 6072–6078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justo, J.; Távara, L.; García-Guzmán, L.; París, F. Characterization of 3D printed long fibre reinforced composites. Compos. Struct. 2018, 185, 537–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Smith, D.E. Anisotropic mechanical properties of oriented carbon fiber filled polymer composites produced with fused filament fabrication. Addit. Manuf. 2017, 18, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koumoulos, E.P.; Tofail, S.; Silien, C.; de Felicis, D.; Moscatelli, R.; Dragatogiannis, D.A.; Bemporad, E.; Sebastiani, M.; Charitidis, C.A. Metrology and nano-mechanical tests for nano-manufacturing and nano-bio interface: Challenges & future perspectives. Mater. Des. 2018, 137, 446–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, N.X.; Vandamme, M.; Ulm, F.-J. Nanoindentation analysis as a two-dimensional tool for mapping the mechanical properties of complex surfaces. J. Mater. Res. 2009, 24, 679–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastiani, M.; Moscatelli, R.; Ridi, F.; Baglioni, P.; Carassiti, F. High-resolution high-speed nanoindentation mapping of cement pastes: Unravelling the effect of microstructure on the mechanical properties of hydrated phases. Mater. Des. 2016, 97, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hintsala, E.D.; Hangen, U.; Stauffer, D.D. High-Throughput Nanoindentation for Statistical and Spatial Property Determination. JOM 2018, 70, 494–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Naranjo, J.E.; Perez-Gonzalez, V.H.; Mata-Gómez, M.A.; Aguilar, O. 3D-printed hybrid-carbon-based electrodes for electroanalytical sensing applications. Electrochem. Commun. 2021, 130, 107098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arfsten, J.; Kampen, I.; Kwade, A. Mechanical testing of single yeast cells in liquid environment: Effect of the extracellular osmotic conditions on the failure behavior. Int. J. Mater. Res. 2009, 100, 978–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, N.; Schilde, C.; Kwade, A. Influence of Particle Size Distribution on Micromechanical Properties of thin Nanoparticulate Coatings. Phys. Procedia 2013, 40, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Testing, I.I.; Kuhn, H.; Medlin, D. Mechanical Testing and Evaluation; ASM International: Almere, The Netherlands, 2000; pp. 232–243. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, W.C.; Pharr, G.M. An improved technique for determining hardness elastic modulus using load displacement sensing indentation experiments. J. Mater. Res. 1992, 7, 1564–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, W.C.; Pharr, G.M. Measurement of hardness elastic modulus by instrumented indentation: Advances in understanding refinements to methodology. J. Mater. Res. 2004, 19, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenouillot, F.; Cassagnau, P.; Majesté, J.-C. Uneven distribution of nanoparticles in immiscible fluids: Morphology development in polymer blends. Polymer 2009, 50, 1333–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, R.H. Conductive Rubbers and Plastics: Their Production, Application and Test Methods; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Blümel, C.; Schmidt, J.; Dielesen, A.; Sachs, M.; Winzer, B.; Peukert, W.; Wirth, K.-E. Dry Particle Coating of Polymer Particles for Tailor-Made Product Properties; American Institute of Physics: Nuremberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 248–252. [Google Scholar]

- Düsenberg, B.; Tischer, F.; Seidel, A.M.; Kopp, S.-P.; Schmidt, J.; Roth, S.; Peukert, W.; Bück, A. Production and analysis of electrically conductive polymer—Carbon-black composites for powder based Additive Manufacturing. Procedia CIRP 2022, 111, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Signori, F.; Coltelli, M.-B.; Bronco, S. Thermal degradation of poly (lactic acid) (PLA) and poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) (PBAT) and their blends upon melt processing. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2009, 94, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Mantia, F.P.; Morreale, M.; Botta, L.; Mistretta, M.C.; Ceraulo, M.; Scaffaro, R. Degradation of polymer blends: A brief review. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2017, 145, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paci, M.; La Mantia, F. Influence of small amounts of polyvinylchloride on the recycling of polyethyleneterephthalate. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 1999, 63, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kister, G.; Cassanas, G.; Vert, M. Effects of morphology, conformation and configuration on the IR and Raman spectra of various poly (lactic acid) s. Polymer 1998, 39, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, S.; Feng, L.; Bian, X.; Li, G.; Chen, X. Evaluation of PLAcontent in PLA/PBATblends using TGA. Polym. Test. 2020, 81, 106211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omura, M.; Tsukegi, T.; Shirai, Y.; Nishida, H.; Endo, T. Thermal Degradation Behavior of Poly (Lactic Acid) in a Blend with Polyethylene. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2006, 45, 2949–2953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, K.P.; Thomas, S.P.; Gopanna, A.; Al-Ghamdi, A.; Chavali, M. Rheology, mechanical properties and thermal degradation kinetics of polypropylene (PP) and polylactic acid (PLA) blends. Mater. Res. Express 2018, 5, 85304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shtein, M.; Pri-Bar, I.; Varenik, M.; Regev, O. Characterization of graphene-nanoplatelets structure via thermogravimetry. Anal. Chem. 2015, 87, 4076–4080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuels, L.E.; Mulhearn, T.O. An experimental investigation of the deformed zone associated with indentation hardness impressions. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 1957, 5, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phani, P.S.; Oliver, W.C. A critical assessment of the effect of indentation spacing on the measurement of hardness and modulus using instrumented indentation testing. Mater. Des. 2019, 164, 107563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokrieh, M.M.; Hosseinkhani, M.R.; Naimi-Jamal, M.R.; Tourani, H. Nanoindentation and nanoscratch investigations on graphene-based nanocomposites. Polym. Test. 2013, 32, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasyap, S.S.; Senetakis, K. Application of Nanoindentation in the Characterization of a Porous Material with a Clastic Texture. Materials 2021, 14, 4579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadri, A.A.; Martín-Alfonso, J.E. Thermal, thermo-oxidative and thermomechanical degradation of PLA: A comparative study based on rheological, chemical and thermal properties. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2018, 150, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaitanelis, D.; Chanteli, A.; Worrall, C.; Weaver, P.M.; Kazilas, M. A multi-technique and multi-scale analysis of the thermal degradation of PEEK in laser heating. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2023, 211, 110282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, I.; Cicala, G.; Recca, G.; Tosto, C. Specific Heat Capacity and Thermal Conductivity Measurements of PLA-Based 3D-Printed Parts with Milled Carbon Fiber Reinforcement. Entropy 2022, 24, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Yuan, N.; Wang, X.; Ning, X.; Chen, C.; Lin, D. Thermal-induced Phase Transition Hydrogel Revealed with Photonic Crystal. ES Energy Environ. 2023, 19, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadler, M.; Mahrholz, T.; Riedel, U.; Schilde, C.; Kwade, A. Preparation of colloidal carbon nanotube dispersions and their characterisation using a disc centrifuge. Carbon 2008, 46, 1384–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.M.; Jeong, S.J.; Park, S.J. Flake Orientation in Injection Molding of Pigmented Thermoplastics. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. 2012, 134, 014501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintana, J.L.C.; Heckner, T.; Chrupala, A.; Pollock, J.; Goris, S.; Osswald, T. Experimental study of particle migration in polymer processing. Polym. Compos. 2019, 40, 2165–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Specimen Number | Extrusion Temperature TE/°C | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zone 4 (Nozzle) | Zone 3 | Zone 2 | Zone 1 | Zone 0 (Feed) | |

| #1 | 180 | 135 | 90 | 45 | 22 |

| #2 | 190 | 142.5 | 95 | 47.5 | |

| #3 | 200 | 150 | 100 | 50 | |

| #4 | 210 | 157.5 | 105 | 52.5 | |

| #5 | 220 | 165 | 110 | 55 | |

| Analytical Method | Filament Strand | Cryo-Fractured | Resin-Embedded | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical | FT-IR | x | ||

| TGA | x | |||

| Electrical | Electrical resistivity | x | ||

| Optical | SEM | x | x |

| Specimen Number | Er/GPa | H/GPa |

|---|---|---|

| #1 | 2.99 ± 1.07 | 0.13 ± 0.05 |

| #2 | 2.84 ± 0.90 | 0.14 ± 0.04 |

| #3 | 3.66 ± 1.79 | 0.17 ± 0.16 |

| #4 | 3.69 ± 0.95 | 0.19 ± 0.04 |

| #5 | 3.73 ± 1.05 | 0.17 ± 0.05 |

| Specimen Number | Reduced E-modulus Er/GPa Location on Filament Cross-Section | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Center | Middle Center | Middle Edge | Edge | |

| #1 | 2.99 ± 1.07 | 3.78 ± 0.98 | 3.73 ± 0.94 | 4.30 ± 0.28 |

| #3 | 3.73 ± 0.92 | 3.88 ± 1.00 | 3.98 ± 1.76 | 3.71 ± 1.09 |

| #5 | 3.79 ± 0.51 | 3.73 ± 1.05 | 3.79 ± 1.36 | 3.74 ± 0.66 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Windisch, L.; Düsenberg, B.; Nowka, M.; Hilbig, K.; Vietor, T.; Schilde, C. Orientation and Influence of Anisotropic Nanoparticles in Electroconductive Thermoplastic Composites: A Micromechanical Approach. Polymers 2025, 17, 3273. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243273

Windisch L, Düsenberg B, Nowka M, Hilbig K, Vietor T, Schilde C. Orientation and Influence of Anisotropic Nanoparticles in Electroconductive Thermoplastic Composites: A Micromechanical Approach. Polymers. 2025; 17(24):3273. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243273

Chicago/Turabian StyleWindisch, Lisa, Björn Düsenberg, Maximilian Nowka, Karl Hilbig, Thomas Vietor, and Carsten Schilde. 2025. "Orientation and Influence of Anisotropic Nanoparticles in Electroconductive Thermoplastic Composites: A Micromechanical Approach" Polymers 17, no. 24: 3273. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243273

APA StyleWindisch, L., Düsenberg, B., Nowka, M., Hilbig, K., Vietor, T., & Schilde, C. (2025). Orientation and Influence of Anisotropic Nanoparticles in Electroconductive Thermoplastic Composites: A Micromechanical Approach. Polymers, 17(24), 3273. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243273