Self-Powered Strain Sensing System: A Cutting-Edge Review Paving the Way for Autonomous Wearable Electronics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Strain Sensors

2.1. Working Mechanisms

2.1.1. Piezoresistive Sensors

2.1.2. Capacitive Sensors

2.1.3. Piezoelectric Sensors

2.1.4. Comparison of Sensing Mechanisms

2.2. Key Performance Parameters

2.2.1. Sensitivity (GF)

2.2.2. Sensing Range

2.2.3. Response/Recovery Time

2.2.4. Cyclic Stability

2.2.5. Mechanical Properties

3. Self-Powered Strain Sensing System with Integrated Energy Storage Device

3.1. Integrated Supercapacitor

3.2. Integrated Micro Battery

3.2.1. Material Systems and Flexibility Strategies

3.2.2. Integration Challenges and Technological Breakthroughs

4. Self-Powered Strain Sensing System Based on Nanogenerators

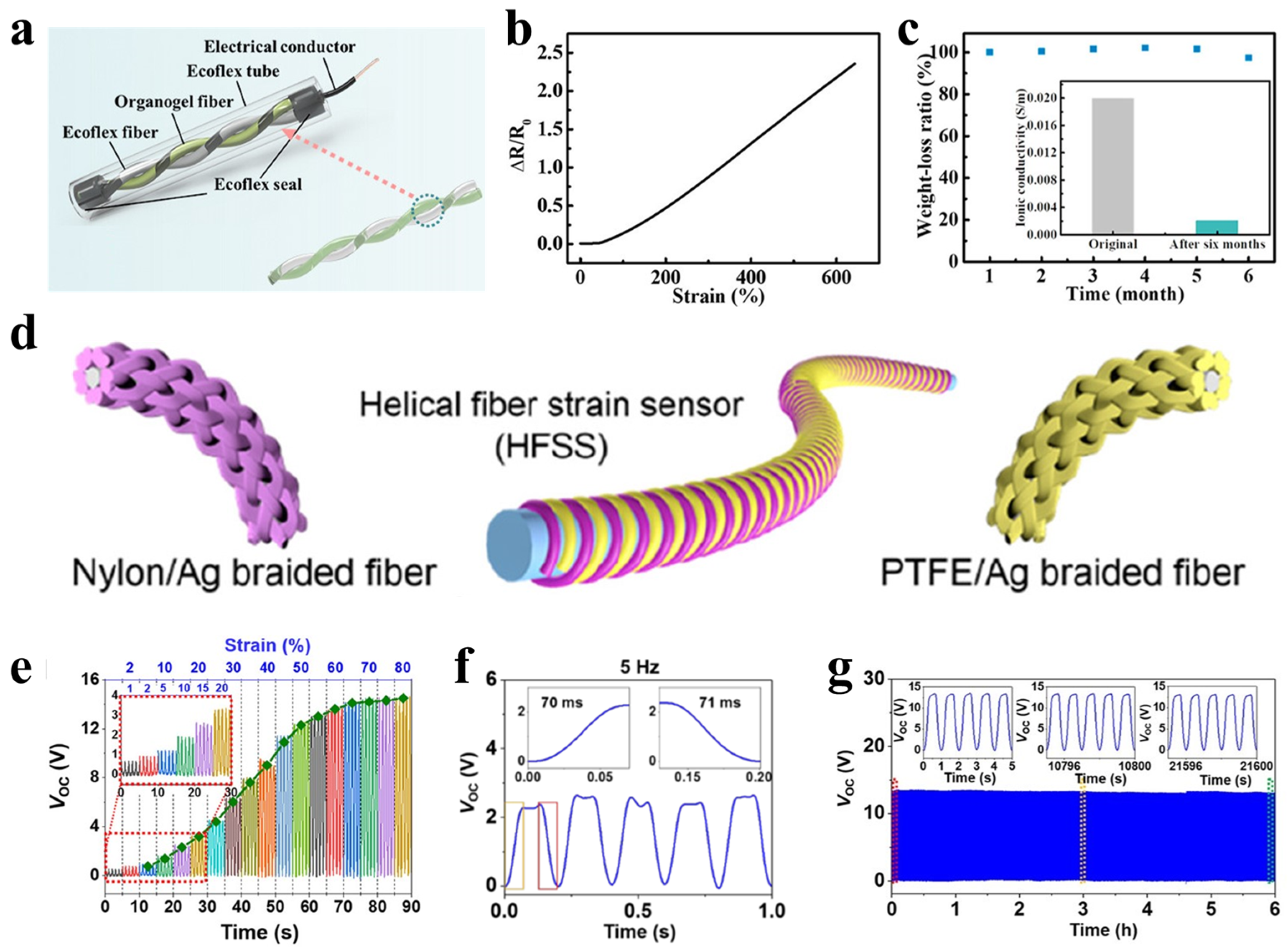

4.1. Integrated Triboelectric Nanogenerator

4.2. Integrated Piezoelectric Nanogenerator

5. Integrated Self-Powered Energy Management System

5.1. System Architecture and Energy Management Strategy

5.2. Innovative Integrated Designs and Technological Breakthroughs

5.2.1. Shared Electrodes and Material Design

5.2.2. Multifunctional Integrated Devices

5.2.3. Intelligent Energy Management Technology

| Self-Powered Strain Sensing System | Sensitivity (GF) | Sensing Range | Response/Recovery Time (ms) | Cyclic Stability | Fracture Stress (MPa)/Tensile Elongation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEDOT:PSS/CNT/WPU composite film [141] | - | 0–100% | 300/700 | 300 (at 20% strain) | -/400 |

| CQDs/MWCNT strain sensor [142] | 94.1 | 0–80° | -/- | 5000 (at 60°) | -/- |

| PVAA-MXene hydrogel [143] | 1.10 (0–400%) 1.76 (400–800%) 2.99 (800–1400%) | 0–1400% | 240/- | 5000 (at 100% strain) | 1.2/1700 |

| CIGS sensor [144] | 10.34 | 0–2% | 0.03/0.02 | 120 (at 1.2% strain) | -/- |

| RGO-PY@HI [145] | 5.05 | 0–180° | -/- | 200 (at 90°) | -/- |

| PAM-BTO/NaCl hydrogel [146] | 1.52 (0–400%) 2.12 (400–600%) | 0–600% | -/- | 50 (at 20% strain) | -/- |

| PVA/PAMAA/Gly/NaCl organohydrogel [147] | 1.817 (0–200%) 3.436 (200–500%) 8.303 (500–1000%) | 1–1000% | 160/- | 600 (at 15% strain) | 0.345/1002 |

| TEC-based sensor [148] | 1.03 (≤50%) | 0–50% 0–9.5 kPa | -/- | 1200 | 0.26/167 |

| Mechano-electrochemical harvesting (MECH) fiber [149] | - | 0–100% | -/- | 1000 (at 100% strain) | 2/>100 |

| PcNA/MXene sensor [150] | 1.86 (0–180%) 1.1 (180–300%) | 0–300% | 290/342 | 2000 (at 50% strain) | -/930 |

| CCNC-C3N4- PAM hydrogel [151] | 5.6 (0–1.6%) | 0–2800% | -/- | - | 0.135/2800 |

| Piezoionic sensor [152] | - | - | 100/80 | >20,000 | 23.42/1200 |

| Porous graphene foam-based material [153] | 109.8 (0–30%) 1401.5 (30–45%) | 0–45% | -/- | - | -/≥45 |

| SnSe2/graphene heterojunction [154] | 450 | - | -/- | 10,000 (at 0.4–0.5% strain) | -/- |

| MP@PU fiber sensor [155] | 1.33 × 102 (30%) 3.31 × 102 (30–50%) 5.83 × 102 (50–80%) 6.23 × 103 (80–110%) 9.95 × 105 (110–120%) | 0–290% | 400/300 | 2000 | -/290 |

| ZIF-8@PAm/PVP hydrogel sensor [156] | 2.34 (0–200%) 4.76 (200–600%) 6.38 (600–900%) | 0–900% | 140/140 | 500 (at 200% strain) | 0.328/944.2 |

6. Challenges and Prospects

6.1. Current Main Challenges

6.2. Future Development Directions

7. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, Y.; Gao, W.; Dai, K.; Wang, S.; Yuan, Z.; Li, J.; Zhai, W.; Zheng, G.; Pan, C.; Liu, C.; et al. Bioinspired Multifunctional Photonic-Electronic Smart Skin for Ultrasensitive Health Monitoring, for Visual and Self-Powered Sensing. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2102332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Zhu, G.; Zhang, F.; Tang, W.-L.; Jianping, S.; Yang, J.-Q.; Zhu, L.-Y. A review of flexible force sensors for human health monitoring. J. Adv. Res. 2020, 26, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Feng, J.; Huang, B.; Duan, W.; Chen, Z.; Huang, J.; Li, B.; Zhou, Z.; Zeng, Z.; Gui, X. Multi-directional strain sensor based on carbon nanotube array for human motion monitoring and gesture recognition. Carbon 2024, 226, 119201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Ma, Z.; Hu, Z.; Long, Y.; Wu, F.; Huang, X.; Nisa, F.U.; Liang, H.; Dong, Y.; Wang, J.; et al. Synergistic Enhancement of Hole–Bridge Structure and Molecular-Crowding Effect in Multifunctional Eutectic Hydrogel Strain/Pressure Sensor for Personal Rehabilitation Training. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2502844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Fan, H.; Lai, X.; Zeng, Z.; Lan, X.; Lin, P.; Tang, L.; Wang, W.; Chen, Y.; Tang, Y. Flexible liquid metal-based microfluidic strain sensors with fractal-designed microchannels for monitoring human motion and physiological signals. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2024, 246, 115905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Yang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, K.; Zhai, W.; Zheng, G.; Dai, K.; Liu, C.; Shen, C. Multilayer Bionic Tunable Strain Sensor with Mutually Non-Interfering Conductive Networks for Machine Learning-Assisted Gesture Recognition. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2416911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, W.; He, J.; Lu, Y.; Wu, Q.; Xing, M. Fabrication Techniques and Sensing Mechanisms of Textile-Based Strain Sensors: From Spatial 1D and 2D Perspectives. Adv. Fiber Mater. 2024, 6, 36–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, P.; Bao, Y.; Zhang, W.; Gao, L.; Zhu, X.; Xu, J.; Ma, J. Synergy of ZnO Nanowire Arrays and Electrospun Membrane Gradient Wrinkles in Piezoresistive Materials for Wide-Sensing Range and High-Sensitivity Flexible Pressure Sensor. Adv. Fiber Mater. 2024, 6, 414–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, M.; Dong, Y.; Liu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Feng, P.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, R.; Sun, C.-L.; He, J. Piezoresistive Sensor Based on Porous Sponge with Superhydrophobic and Flame Retardant Properties for Motion Monitoring and Fire Alarm. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 2105–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.-S.; Yang, F.; Xu, J.; Kong, Y.; Zheng, H.; Chen, L.; Chen, Y.; Wu, M.X.; Yang, B.-R.; Luo, Y.; et al. Ultrasonically Patterning Silver Nanowire–Acrylate Composite for Highly Sensitive and Transparent Strain Sensors Based on Parallel Cracks. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 47729–47738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Wu, W.; Chang, Y.; Chen, W.; Liu, Y.; He, Z.; Pu, Y.; Babichuk, I.S.; Ye, T.T.; Gao, Z.; et al. Flexible strain sensors based on silver nanowires and UV-curable acrylate elastomers for wrist movement monitoring. RSC Appl. Interfaces 2024, 1, 684–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, G.; Xue, Y.; Duan, Q.; Liang, X.; Lin, T.; Wu, Z.; Tan, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Zheng, W.; et al. Fatigue-Resistant Conducting Polymer Hydrogels as Strain Sensor for Underwater Robotics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2305705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.-Z.; Guo, W.-T.; Chen, H.; Yin, Z.-X.; Tang, X.-G.; Sun, Q.-J. Recent Progress on Flexible Self-Powered Tactile Sensing Platforms for Health Monitoring and Robotics. Small 2024, 20, 2405520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, C.; Cheng, R.; Jiang, Y.; Sheng, F.; Yi, J.; Shen, S.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, X.; Dong, K.; Wang, Z.L. Helical Fiber Strain Sensors Based on Triboelectric Nanogenerators for Self-Powered Human Respiratory Monitoring. ACS Nano 2022, 16, 2811–2821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhan, Y.; Poisson, J.; Meng, X.; Wang, Z.; Chen, L.; Wu, T.-H.; Koehler, R.; Zhang, K. Electrospun Lignin/ZnO Nanofibrous Membranes for Self-Powered Ultrasensitive Flexible Airflow Sensor and Wearable Device. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, 2502211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Gbadam, G.S.; Niu, S.; Ryu, H.; Lee, J.-H. Manufacturing strategies for highly sensitive and self-powered piezoelectric and triboelectric tactile sensors. Int. J. Extrem. Manuf. 2025, 7, 012006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Xia, Y.; Zhi, J.; Ma, J.; Chen, J.; Chu, Z.; Gao, W.; Liu, S.; Qin, Y. Impedance decoupling strategy to enhance the real-time powering performance of TENG for multi-mode sensing. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 6001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, Y.; Wei, L.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Lan, L.; Tang, L.; Wang, F.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, L.; et al. Strain-Insensitive Supercapacitors for Self-Powered Sensing Textiles. ACS Nano 2025, 19, 6357–6370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Lv, H.; Shi, X.-L.; Liu, Z.; Chen, G.; Chen, Z.-G.; Sun, G. A flexible quasi-solid-state thermoelectrochemical cell with high stretchability as an energy-autonomous strain sensor. Mater. Horiz. 2021, 8, 2750–2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, K.; Lu, J.; Xu, L.; Wu, J.; Li, J.; Liu, S.; Xuan, W.; Chen, J.; Jin, H.; et al. A triboelectric nanogenerator-based self-powered long-distance wireless sensing platform for industries and environment monitoring. Nano Res. 2024, 17, 9704–9711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Wu, X.; Qi, L.; Dai, X.; Wang, J.; Jiang, T.; Hong, Z. CaTiO3/ZnO-PVDF Composite-Based Triboelectric Nanogenerators for Self-Powered Gait Sensing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, e07124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, R.; Wei, L.; Xu, N.; Xiong, Y.; Sun, Q.; Wang, Z.L. Machine Learning Enhanced Self-Charging Power Sources. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2505719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Sun, Q.; Wang, Z.L. Self-Powered Sensing in Wearable Electronics—A Paradigm Shift Technology. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 12105–12134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Pan, J.; Peng, H. Stretchable lithium-air batteries for wearable electronics. J. Mater. Chem. A 2016, 4, 13419–13424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Liao, Y.; Wang, Y.C.; Zhang, S.; Yang, W.; Pan, X.; Wang, Z.L. Cellulose II Aerogel-Based Triboelectric Nanogenerator. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 2001763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, X.; Hu, Q.; Li, Z.; Wang, Z.L.; Li, L. Flexible and highly piezoelectric nanofibers with organic–inorganic coaxial structure for self-powered physiological multimodal sensing. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 451, 139077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Sun, Y.; Zhu, J.; Xu, J.; Zhang, C.; Liu, T. Hydrogen-bonded network enables polyelectrolyte complex hydrogels with high stretchability, excellent fatigue resistance and self-healability for human motion detection. Compos. Part B-Eng. 2021, 217, 108901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Liu, L.; Lin, Y.H.; Feng, R.; Shen, Y.; Chang, Y.; Zhao, H. High-stretchability and low-hysteresis strain sensors using origami-inspired 3D mesostructures. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadh9799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, G.; Zhang, Y.; Chao, Y.; Huang, F.; Li, M.; Liu, M.; Huang, W. Tunable sensitivity of strain sensor by coupling piezotronic and tunneling effects. Nano Energy 2025, 145, 111440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, Y.; Tan, S.; Ma, J. Flame-Retardant PEDOT:PSS/LDHs/Leather Flexible Strain Sensor for Human Motion Detection. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2022, 43, 2100873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Shi, L.; Cao, Z.; Wang, R.; Sun, J. Strain Sensors with a High Sensitivity and a Wide Sensing Range Based on a Ti3C2Tx (MXene) Nanoparticle–Nanosheet Hybrid Network. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1807882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, L.; Yang, Z.; Chen, L.; Wu, Z.; Ye, C. Compressible AgNWs/Ti3C2Tx MXene aerogel-based highly sensitive piezoresistive pressure sensor as versatile electronic skins. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 20030–20036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, F.; Luo, J.; Pan, R.; Wu, J.; Guo, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, M.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, D.; et al. Vanadium Dioxide Nanosheets Supported on Carbonized Cotton Fabric as Bifunctional Textiles for Flexible Pressure Sensors and Zinc-Ion Batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 41577–41587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, R.; Yang, F.; Zhang, J.; Wu, X. Bioinspired Potentiometric and Passive Strain Sensing Based on Mechanical Regulation of Ionically Conductive Percolating Networks. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2024, 9, 2400144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, H.; Han, W.; Lin, H.; Li, R.; Zhu, J.; Huang, W. 3D Printed Flexible Strain Sensors: From Printing to Devices and Signals. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2004782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Q.; Wang, C.; Wu, H.; Luo, X.; Li, J.; Ma, G.; Li, Y.; Luo, C.; Guo, F.; Long, Y. 3D Printing of Capacitive Pressure Sensors with Tuned Wide Detection Range and High Sensitivity Inspired by Bio-Inspired Kapok Structures. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2024, 45, 2300668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Ning, H.; Tian, Y.; Xiang, C.; Zhao, H.; Liu, Y.; Lee, A.; Gong, X.; Hu, N.; et al. Dual-Dielectric-Layer-Based Iontronic Pressure Sensor Coupling Ultrahigh Sensitivity and Wide-Range Detection for Temperature/Pressure Dual-Mode Sensing. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, e03926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Chen, X.; Li, X.; Wang, C.; Tian, H.; Chen, X.; Nie, B.; Shao, J. Flexible, Equipment-Wearable Piezoelectric Sensor with Piezoelectricity Calibration Enabled by In-Situ Temperature Self-Sensing. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2022, 69, 6381–6390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaszczyńska, A.; Zabielski, K.; Gradys, A.; Kowalczyk, T.; Sajkiewicz, P. Piezoelectric Scaffolds as Smart Materials for Bone Tissue Engineering. Polymers 2024, 16, 2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Lai, K.; Li, M.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y. An oxide thin-film transistor-based micro-newton force sensor with piezoelectric ZnO nanorods as back-channel strain-gate. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1040, 183401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Zou, H.; Jiang, B.; Li, M.; Yuan, Q. Incorporation of ZnO encapsulated MoS2 to fabricate flexible piezoelectric nanogenerator and sensor. Nano Energy 2022, 102, 107635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajala, S.; Siponkoski, T.; Sarlin, E.; Mettänen, M.; Vuoriluoto, M.; Pammo, A.; Juuti, J.; Rojas, O.J.; Franssila, S.; Tuukkanen, S. Cellulose Nanofibril Film as a Piezoelectric Sensor Material. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 15607–15614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chorsi, M.T.; Curry, E.J.; Chorsi, H.T.; Das, R.; Baroody, J.; Purohit, P.K.; Ilies, H.; Nguyen, T.D. Piezoelectric Biomaterials for Sensors and Actuators. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1802084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Guan, Y.; Liu, M.; Kang, X.; Tian, Y.; Deng, W.; Yu, P.; Ning, C.; Zhou, L.; Fu, R.; et al. Tough, Antifreezing, and Piezoelectric Organohydrogel as a Flexible Wearable Sensor for Human–Machine Interaction. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 3720–3732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; Guo, X.; Han, C.; Liu, L.; Wang, Z.; Thomsen, L.; Chen, P.; Shao, Z.; Wang, X.; Xie, F.; et al. Creation of Piezoelectricity in Quadruple Perovskite Oxides by Harnessing Cation Defects and Their Application in Piezo-Photocatalysis. ACS Nano 2025, 19, 3818–3829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roshandel, N.; Soleymanzadeh, D.; Ghafarirad, H.; Sadri Koupaei, A.M. A modified sensorless position estimation approach for piezoelectric bending actuators. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2021, 149, 107231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yu, J.; Cui, Y.; Li, W. Research progress of flexible wearable pressure sensors. Sens. Actuators A-Phys. 2021, 330, 112838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.-S.; Chung, M.-K.; Yoo, J.-Y.; Kim, M.-U.; Kim, B.-J.; Jo, M.-S.; Kim, S.-H.; Yoon, J.-B. Interference-free nanogap pressure sensor array with high spatial resolution for wireless human-machine interfaces applications. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Jang, M.; Jeong, G.; Yu, S.; Park, J.; Lee, Y.; Cho, S.; Yeom, J.; Lee, Y.; Choe, A.; et al. MXene-Enhanced β-Phase Crystallization in Ferroelectric Porous Composites for Highly-Sensitive Dynamic Force Sensors. Nano Energy 2021, 89, 106409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Zhao, J.; Li, R.; Zhou, Z.; Gui, Y.; Sun, R.; Wu, D.; Wang, X. Construction of laser-induced graphene/silver nanowire composite structures for low-strain, high-sensitivity flexible wearable strain sensors. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2024, 67, 3524–3534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Yan, Y.; Wang, W.; Wu, J.; Yu, K.; Wu, X.; Wang, Z. Synergistic ionic and electronic transport pathways enabled strain sensors with ultra-high and modulable sensitivity within wide working range. Nano Res. 2025, 18, 94908146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.; Rong, C.; Zhang, B.; Xuan, F.-Z. High-sensitivity omnidirectional recognition strain sensor based on two-dimensional materials. Nano Res. 2025, 18, 94907411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.; Wang, C.; Du, X.; Bai, X.; Tong, Y.; Chen, H.; Sun, X.; Yang, J.; Matsuhisa, N.; Peng, H.; et al. In-situ forming ultra-mechanically sensitive materials for high-sensitivity stretchable fiber strain sensors. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2024, 11, nwae158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Wu, X.; Yin, M.; Yin, L.; Qu, S.; Zhang, F.; Li, K.; Huang, Y. Flexible Strain Sensors with Ultra-High Sensitivity and Wide Range Enabled by Crack-Modulated Electrical Pathways. Nano-Micro Lett. 2024, 17, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhai, W.; Zhao, X.; Dai, K.; Liu, C.; Shen, C. Highly aligned electrospun film with wave-like structure for multidirectional strain and visual sensing. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 485, 149952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Y.; Liu, L.; Huang, J.; Li, S.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, W.; Lai, Y. Rational designed microstructure pressure sensors with highly sensitive and wide detection range performance. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2022, 130, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, C.; Li, W.; Dong, E.; Xu, M.; Huang, H.; Yang, Y.; Li, L.; Zheng, L.; et al. Breaking the Saturation of Sensitivity for Ultrawide Range Flexible Pressure Sensors by Soft-Strain Effect. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2405405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, F.; Peng, Q.; Ding, R.; Li, P.; Zhao, X.; Zheng, H.; Xu, L.; Tang, Z.; Zhang, X.; He, X. Ultra-sensitive, highly linear, and hysteresis-free strain sensors enabled by gradient stiffness sliding strategy. npj Flex. Electron. 2024, 8, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Liao, S.; Chu, Y.; Cai, Y.; Wei, Q.; Chen, K.; Wang, Q. Highly Durable and Fast Response Fabric Strain Sensor for Movement Monitoring Under Extreme Conditions. Adv. Fiber Mater. 2023, 5, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Chai, S.; Zhu, L.; Li, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Li, P.; Fu, Y.; Ma, L.; Yun, C.; Chen, F.; et al. Wearable fiber-based visual strain sensors with high sensitivity and excellent cyclic stability for health monitoring and thermal management. Nano Energy 2024, 131, 110300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.-S.; Ryu, H.; Khan, U.; Wu, C.; Jung, J.-H.; Wu, J.; Wang, Z.; Kim, S.-W. Piezoionic-powered graphene strain sensor based on solid polymer electrolyte. Nano Energy 2021, 81, 105610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yao, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z.; Liu, L.; Yang, X.; Zhang, J.; Niu, S.; Han, Z.; Ren, L. Bionic multifunctional ultra-linear strain sensor, achieving underwater motion monitoring and weather condition monitoring. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 464, 142539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Guo, C.; Xu, S.; Song, H. Stretchable ionic conductive gels for wearable human-activity detection. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 489, 151231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhou, R.; Li, D.; Zhang, L.; Ren, G.; Wang, L.; Liu, J.; Wang, D.; Tang, Z.; Lu, G.; et al. High-Performance Foam-Shaped Strain Sensor Based on Carbon Nanotubes and Ti3C2Tx MXene for the Monitoring of Human Activities. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 9690–9700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Park, J.; Root, S.E.; Bao, Z. Skin-inspired soft bioelectronic materials, devices and systems. Nat. Rev. Bioeng. 2024, 2, 671–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herren, B.; Saha, M.C.; Altan, M.C.; Liu, Y. Development of ultrastretchable and skin attachable nanocomposites for human motion monitoring via embedded 3D printing. Compos. Part B-Eng. 2020, 200, 108224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, D.; Wang, C.; Hao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Bao, P.; Wu, H. 3D Extruded Graphene Thermoelectric Threads for Self-Powered Oral Health Monitoring. Small 2023, 19, 2300908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, M.; Bhatt, D.; Bhatt, R.C.; Bohra, B.S.; Tatrari, G.; Rana, S.; Arya, M.C.; Sahoo, N.G. High Energy Density Supercapacitors: An Overview of Efficient Electrode Materials, Electrolytes, Design, and Fabrication. Chem. Rec. 2024, 24, e202300236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Cheng, M.; Huang, H.; Pang, J.; Liu, S.; Xu, Y.; Bu, X.-H. Metal-organic frameworks for advanced aqueous ion batteries and supercapacitors. EnergyChem 2022, 4, 100090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Jia, Y.; Guo, S.; Mi, Y.; Yin, Y.; Wang, B.; Du, P. Hierarchical graphene-quinone-amine polymer nanocomposites with redox activity for high-performance flexible supercapacitors. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1044, 184301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Li, R.; Zheng, B.; Song, S.; Shu, H.; Gao, D.; Li, T.; Ma, Y. High-performance MXene/reduced graphene oxide/carbon nanofibers@MoS2 composite films for flexible asymmetric supercapacitors. Electrochim. Acta 2025, 542, 147468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Xie, S.; Cai, H.; Colli, A.N.; Monnens, W.; Zhang, Q.; Guo, W.; Zhang, W.; Han, N.; Pan, H.; et al. A synchronous-twisting method to realize radial scalability in fibrous energy storage devices. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eado7826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, L.; Xu, C.; Pan, Z.; Zhou, Q.; Zhou, W.; Wang, J.; Gu, L.; Liu, H. Electrochemically Exfoliated Chlorine-Doped Graphene for Flexible All-Solid-State Micro-Supercapacitors with High Volumetric Energy Density. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2106309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, S.; Li, Z.; Su, Z.; Jin, Y.; Song, H.; Zheng, H.; Song, J.; Hu, L.; Yin, X.; Xu, Z.; et al. Highly Stable Supercapacitors Enabled by a New Conducting Polymer Complex PEDOT:CF3SO2(x)PSS(1-x). ChemSusChem 2023, 16, e202202208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Man, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, G.; Lu, W.; Chen, W. High-Performance Stretchable Supercapacitors Based on Centrifugal Electrospinning-Directed Hetero-structured Graphene–Polyaniline Hierarchical Fabric. Adv. Fiber Mater. 2023, 5, 1759–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, H.; Pei, D.; Wan, S.; Fan, Z.; Yu, M.; Lu, H. Refinement of structural characteristics and supercapacitor performance of MnO2 nanosheets via CTAB-assisted electrodeposition. Prog. Nat. Sci.-Mater. 2023, 33, 881–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pameté, E.; Köps, L.; Kreth, F.A.; Pohlmann, S.; Varzi, A.; Brousse, T.; Balducci, A.; Presser, V. The Many Deaths of Supercapacitors: Degradation, Aging, and Performance Fading. Adv. Energy Mater. 2023, 13, 2301008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, L.; Wu, T.; Chen, M.; Yang, L.; Yang, J.; Wang, Z.; Kornyshev, A.A.; Jiang, H.; Bi, S.; Feng, G. Conductive Metal–Organic Frameworks for Supercapacitors. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2200999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, L.; Xue, Y.; Lei, I.M.; Chen, X.; Zhang, P.; Cai, C.; Liang, X.; Lu, Y.; Liu, J. Engineering Electrodes with Robust Conducting Hydrogel Coating for Neural Recording and Modulation. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2209324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wei, X.; Jiang, F.; Wang, Y.; Xie, M.; Peng, J.; Yi, C.; Li, J.; Zhai, M. An Ultrastretchable and Highly Conductive Hydrogel Electrolyte for All-in-One Flexible Supercapacitor with Extreme Tensile Resistance. Energy Environ. Mater. 2025, 8, e12820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, P.; Ding, Y.; Zhu, P.; Liu, Y.; Wang, C.; Gao, C. Multifunctional Nano-Conductive Hydrogels with High Mechanical Strength, Toughness and Fatigue Resistance as Self-Powered Wearable Sensors and Deep Learning-Assisted Recognition System. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2409081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Han, S.; Zhu, J.; Wu, Q.; Chen, H.; Chen, A.; Zhang, J.; Huang, B.; Yang, X.; Guan, L. Mechanically Stable All Flexible Supercapacitors with Fracture and Fatigue Resistance under Harsh Temperatures. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2205708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Chen, C.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Xu, L.; Wu, D.-D.; Gao, B.; Song, A.; Wen, L.; Cheng, Y.; et al. Flexible Monolithic 3D-Integrated Self-Powered Tactile Sensing Array Based on Holey MXene Paste. Nano-Micro Lett. 2025, 18, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Xu, L.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, A.; Zhang, J. Self-Powered Integrated Sensing System with In-Plane Micro-Supercapacitors for Wearable Electronics. Small 2023, 19, 2207723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, G.; Ju, J.; Li, M.; Wu, H.; Jian, Y.; Sun, W.; Wang, W.; Li, C.M.; Qiao, Y.; Lu, Z. Weavable yarn-shaped supercapacitor in sweat-activated self-charging power textile for wireless sweat biosensing. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2023, 235, 115389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, F.-L.; Meng, F.-C.; Li, Y.-Q.; Huang, P.; Hu, N.; Liao, K.; Fu, S.-Y. Highly stretchable CNT Fiber/PAAm hydrogel composite simultaneously serving as strain sensor and supercapacitor. Compos. Part B-Eng. 2020, 198, 108246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Gong, Q.; Han, L.; Liu, X.; Yang, Y.; Chen, C.; Qian, C.; Han, Q. Carboxymethyl cellulose assisted polyaniline in conductive hydrogels for high-performance self-powered strain sensors. Carbohyd. Polym. 2022, 298, 120060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, S.; Ramirez, J.; Shewan, H.M.; Lyu, M.; Gentle, I.; Wang, L.; Knibbe, R. Ink to Power: An Organic-based Polymer Electrolyte for Ambient Printing of Flexible Zinc Batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2402050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Jiang, H.; Cheng, X.; He, J.; Long, Y.; Chang, Y.; Gong, X.; Zhang, K.; Li, J.; Zhu, Z.; et al. High-performance fibre battery with polymer gel electrolyte. Nature 2024, 629, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhong, L.; Chen, Z.; Zhuo, H.; Zhao, X.; Lai, H.; Li, T.; Yang, W.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, H.; et al. Reconstructed Wood Carbon Aerogel with Single-Atom Sites for Flexible Zn–Air Batteries. ACS Nano 2025, 19, 23859–23868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikhe, A.B.; Park, W.B.; Han, S.C.; Seo, J.Y.; Han, S.; Sohn, K.-S.; Pyo, M. Li+-intercalated carbon cloth for anode-free Li-ion batteries with unprecedented cyclability. J. Mater. Chem. A 2022, 10, 21456–21464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Yang, J.; Tan, R.; Shu, W.; Low, C.J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Li, C.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; et al. Large-scale current collectors for regulating heat transfer and enhancing battery safety. Nat. Chem. Eng. 2024, 1, 542–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Tian, C.; Li, X.; Li, T.; Fang, Y.; Pan, K.; Zhou, Z. Designing PEO-Based Electrolytes via Entropy-Enthalpy Engineering for High-Voltage Solid-State Lithium Metal Batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, e16074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Chen, Z.; Jin, J.; Yang, S.; Zhang, J.; Li, G. Interconnected Hollow Porous Polyacrylonitrile-Based Electrolyte Membrane for a Quasi-Solid-State Flexible Zinc–Air Battery with Ultralong Lifetime. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 31792–31802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsov, O.A.; Mohanty, S.; Pigos, E.; Chen, G.; Cai, W.; Harutyunyan, A.R. High energy density flexible and ecofriendly lithium-ion smart battery. Energy Storage Mater. 2023, 54, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Lou, Z.; Jiang, K.; Shen, G. Device Configurations and Future Prospects of Flexible/Stretchable Lithium-Ion Batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1805596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.C.; Lee, S.; Ma, B.S.; Kim, J.; Song, M.; Kim, S.Y.; Kim, D.W.; Kim, T.-S.; Park, S. Geometrically engineered rigid island array for stretchable electronics capable of withstanding various deformation modes. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabn3863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Z.; Ma, T.; Tang, R.; Cheng, Q.; Wang, X.; Krishnaraju, D.; Panat, R.; Chan, C.K.; Yu, H.; Jiang, H. Origami lithium-ion batteries. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Wang, X.; Lv, C.; An, Y.; Liang, M.; Ma, T.; He, D.; Zheng, Y.-J.; Huang, S.-Q.; Yu, H.; et al. Kirigami-based stretchable lithium-ion batteries. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 10988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Guo, X.; Yang, S.; Liang, G.; Li, Q.; Chen, Z.; Huang, Z.; Yang, Q.; Han, C.; Zhi, C. Human joint-inspired structural design for a bendable/foldable/stretchable/twistable battery: Achieving multiple deformabilities. Energy Environ. Sci. 2021, 14, 3599–3608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, J.; Dong, S.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, B.; Jiang, F.; Cui, Z.; Zhang, H.; Du, X.; Lu, T.; et al. Leakage-Proof Electrolyte Chemistry for a High-Performance Lithium–Sulfur Battery. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 16487–16491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, J.; Li, C.; Li, D.; Song, X.; Chen, S.; Xu, F. Self-gelated flexible lignin-based ionohydrogels for efficient self-powered strain sensors. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 507, 160750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askari, H.; Khajepour, A.; Khamesee, M.B.; Saadatnia, Z.; Wang, Z.L. Piezoelectric and triboelectric nanogenerators: Trends and impacts. Nano Today 2018, 22, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Zhan, L.; Lee, J.P.; Lee, P.S. Triboelectric Nanogenerators Based on Fluid Medium: From Fundamental Mechanisms toward Multifunctional Applications. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2308197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Jin, H.; Dong, S.; Huang, S.; Kuang, H.; Xu, H.; Chen, J.; Xuan, W.; Zhang, S.; Li, S.; et al. High-performance triboelectric nanogenerator based on electrospun PVDF-graphene nanosheet composite nanofibers for energy harvesting. Nano Energy 2021, 80, 105599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, H.; Peng, L.; Yang, Q.; Wang, Z.L.; Cao, X. Triboelectric nanogenerator for high-entropy energy, self-powered sensors, and popular education. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eads2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.L. Triboelectric nanogenerators as new energy technology and self-powered sensors—Principles, problems and perspectives. Faraday Discuss. 2014, 176, 447–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, L.; Liu, W.; Wang, Z.; He, W.; Li, G.; Tang, Q.; Guo, H.; Pu, X.; Liu, Y.; Hu, C. High performance floating self-excited sliding triboelectric nanogenerator for micro mechanical energy harvesting. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Zhang, X.; Jia, T.; Wu, Q.; Dong, Y.; Wang, D. Triboelectric nanogenerator with a seesaw structure for harvesting ocean energy. Nano Energy 2022, 102, 107622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yan, W.; Han, J.; Chen, B.; Wang, Z.L. Aerodynamics-Based Triboelectric Nanogenerator for Enhancing Multi-Operating Robustness via Mode Automatic Switching. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2202964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiswarya, K.; Navaneeth, M.; Bochu, L.; Kodali, P.; Kumar, R.R.; Reddy, S.K. Wrinkled PDMS/MXene composites: A pathway to high-efficiency triboelectric nanogenerators. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2025, 198, 109739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, F.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Cheng, R.; Wei, C.; Ning, C.; Dong, K.; Wang, Z.L. Ultrastretchable Organogel/Silicone Fiber-Helical Sensors for Self-Powered Implantable Ligament Strain Monitoring. ACS Nano 2022, 16, 10958–10967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Teng, L.; Wang, X.; Lu, T.; Leng, W.; Wu, X.; Li, D.; Zhong, Y.; Sun, X.; Zhu, S.; et al. Efficient multi-physical crosslinked nanocomposite hydrogel for a conformal strain and self-powered tactile sensor. Nano Energy 2025, 135, 110669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Chen, J.; Li, X.; Zhou, Z.; Meng, K.; Wei, W.; Yang, J.; Wang, Z.L. Triboelectric Nanogenerator Enabled Body Sensor Network for Self-Powered Human Heart-Rate Monitoring. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 8830–8837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Gao, Y.; Zhou, L.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.L. Recent advances in high-performance triboelectric nanogenerators. Nano Res. 2023, 16, 11698–11717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Su, P.; Lin, Z.; Li, X.; Chen, K.; Ye, T.; Li, Y.; Zou, Y.; Wang, W. A Tribo/Piezoelectric Nanogenerator Based on Bio-MOFs for Energy Harvesting and Antibacterial Wearable Device. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, 2418207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, X.; Jia, W.; Qian, S.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, J.; Hou, X.; Mu, J.; Geng, W.; Cho, J.; He, J.; et al. High-Performance PZT-Based Stretchable Piezoelectric Nanogenerator. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 979–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Liu, J.; Zou, J.; Xu, S.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, W.; Li, D. Electrospun PAN/BaTiO3/MXene nanofibrous membrane with significantly improved piezoelectric property for self-powered wearable sensor. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 489, 151495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Song, Y.; Su, Z.; Chen, H.; Cheng, X.; Zhang, J.; Han, M.; Zhang, H. Flexible fiber-based hybrid nanogenerator for biomechanical energy harvesting and physiological monitoring. Nano Energy 2017, 38, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Ding, W.; Liu, J.; Yang, B. Flexible PVDF based piezoelectric nanogenerators. Nano Energy 2020, 78, 105251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Qian, Y.; Lee, B.S.; Zhang, F.; Rasheed, A.; Jung, J.-E.; Kang, D.J. Ultrahigh Output Piezoelectric and Triboelectric Hybrid Nanogenerators Based on ZnO Nanoflakes/Polydimethylsiloxane Composite Films. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 44415–44420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jean, F.; Khan, M.U.; Alazzam, A.; Mohammad, B. Advancement in piezoelectric nanogenerators for acoustic energy harvesting. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2024, 10, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Li, L.; Wang, F.; Kim, S.-W.; Sun, H. Mitigating the Negative Piezoelectricity in Organic/Inorganic Hybrid Materials for High-performance Piezoelectric Nanogenerators. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 34733–34741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Mao, J.; Cao, L.; Zheng, X.; Meng, Q.; Zhao, S.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, D.; Zheng, H. Intelligent cardiovascular disease diagnosis system combined piezoelectric nanogenerator based on 2D Bi2O2Se with deep learning technique. Nano Energy 2024, 128, 109878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Bai, M.; Wang, Q.; Liu, L.; Yu, S.; Kong, B.; Lv, F.; Guo, M.; Liu, G.; Li, L.; et al. A self-powered wearable piezoelectric nanogenerator for physiological monitoring based on lead zirconate titanate/microfibrillated cellulose@polyvinyl alcohol (PZT/MFC@PVA) composition. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 460, 141598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.A.M.; Wang, Y.; Bowen, C.R.; Yang, Y. 2D Nanomaterials for Effective Energy Scavenging. Nano-Micro Lett. 2021, 13, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Z.; Deng, S.; Shao, J.; Si, Y.; Zhou, C.; Luo, J.; Wang, T.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Liu, H.; et al. Ultrahigh-power-density flexible piezoelectric energy harvester based on freestanding ferroelectric oxide thin films. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.; Cao, X.; Zou, J.; Ma, Y.; Wu, X.; Sun, C.; Li, M.; Wang, N.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, L. Triboelectric Nanogenerator Boosts Smart Green Tires. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1806331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, G.; Rehman, A.; Gautam, J.; Ikram, M.; Hussain, S.; Aftab, S.; Heo, K.; Lee, S.-Y.; Park, S.-J. Advancements in flexible Perovskite solar cells and their integration into self-powered wearable optoelectronic systems. Adv. Powder Mater. 2025, 4, 100304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Qu, K.; You, Y.; Huang, Z.; Liu, S.; Li, J.; Hu, Q.; Guo, Z. Overview of cellulose-based flexible materials for supercapacitors. J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9, 7278–7300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Yang, J.; Chen, P.; Wang, M.; He, S.; Wang, L.; Qiu, J. Flexible Electrodes for Aqueous Hybrid Supercapacitors: Recent Advances and Future Prospects. Electrochem. Energy Rev. 2024, 7, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Li, C.; Liu, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, D.; Du, J.; Zhang, Q.; Yao, Y. Flexible Quasi-Solid-State Aqueous Zinc-Ion Batteries: Design Principles, Functionalization Strategies, and Applications. Adv. Energy Mater. 2023, 13, 2300250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, D.; Nishio, Y.; Wu, C.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, W.; Yuan, Y.; Yao, Y.; Tok, J.B.H.; Bao, Z. Design Considerations and Fabrication Protocols of High-Performance Intrinsically Stretchable Transistors and Integrated Circuits. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 33011–33031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Li, H.; Shi, B.; Fan, Y.; Wang, Z.L.; Li, Z. Wearable and Implantable Triboelectric Nanogenerators. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1808820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-H.; Kim, M.-G.; Kang, W.; Park, H.-M.; Cho, Y.; Hong, J.; Kim, T.-H.; Kim, S.-H.; Cho, S.-K.; Kang, D.; et al. Pulse-Charging Energy Storage for Triboelectric Nanogenerator Based on Frequency Modulation. Nano-Micro Lett. 2025, 17, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Lin, S.; Gong, W.; Lin, R.; Jiang, C.; Yang, X.; Hu, Y.; Wang, J.; Xiao, X.; Li, K.; et al. Single body-coupled fiber enables chipless textile electronics. Science 2024, 384, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Xu, Z.; Cao, R.; Li, X.; Yu, H.; Shen, Z.; Yang, W.; Li, F.; Liu, Y.; Li, H.; et al. Multipurpose Smart Textile with Integration of Efficient Energy Harvesting, All-Season Switchable Thermal Management and Self-Powered Sensing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, e09281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Hu, Q.; Wang, S.; Liu, Z.; Tang, C.; Li, L. Versatile hydrogel towards coupling of energy harvesting and storage for self-powered round-the-clock sensing. J. Mater. Chem. A 2025, 13, 2642–2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandiyan, A.; Vengudusamy, R.; Veeramuthu, L.; Muthuraman, A.; Babu, S.; Jawaharlal, H.; Chen, H.-Y.; Chen, P.-H.; Wang, Y.-C.; Kao, C.R.; et al. High-performance dual-strategy reinforced spontaneously polarized nanofibers with tailored MXene interfaces for sustainable multifunctional intelligent textiles. Compos. Part B-Eng. 2026, 309, 113089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zi, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Li, S.; Wen, Z.; Guo, H.; Wang, Z.L. Effective energy storage from a triboelectric nanogenerator. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Hao, Y.; He, M.; Qin, X.; Wang, L.; Yu, J. Stretchable Thermoelectric-Based Self-Powered Dual-Parameter Sensors with Decoupled Temperature and Strain Sensing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 60498–60507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Dong, G.; Jiang, F.; Wang, X.; Diao, B.; Li, X.; Joo, S.W.; Zhang, L.; Kim, S.H.; Cong, C.; et al. Carbon Quantum Dot/Multiwalled Carbon Nanotube-Based Self-Powered Strain Sensors for Remote Human Motion Detection. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2024, 7, 27706–27716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, A.; Han, S.; Wu, Q.; Chen, Y.; Huang, J.; Guan, L. Self-Powered Integrated System with a Flexible Strain Sensor and a Zinc–Air Battery. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 45260–45269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Yang, L.; Huang, Q.; Li, D.; Huang, W.; Guo, X.; Zhang, C. Ultrafast self-powered strain sensor utilizing a flexible solar cell. Nano Energy 2025, 139, 110920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Li, L.; Zhang, D.; Tian, W. An editable yarn-based flexible supercapacitor and integrated self-powered sensor. Sci. China Mater. 2025, 68, 1117–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, G.-T.; Chen, N.; Lu, B.; Xu, J.-L.; Rodriguez, R.D.; Sheremet, E.; Hu, Y.-D.; Chen, J.-J. Flexible solid-state Zn-Co MOFs@MXene supercapacitors and organic ion hydrogel sensors for self-powered smart sensing applications. Nano Energy 2023, 118, 108936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Peng, S.; Gu, J.; Chen, G.; Gao, J.; Zhang, J.; Hou, L.; Yang, X.; Jiang, X.; Guan, L. Self-powered integrated system of a strain sensor and flexible all-solid-state supercapacitor by using a high performance ionic organohydrogel. Mater. Horiz. 2020, 7, 2085–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chen, S.; Han, Z.; Qu, X.; Jin, M.; Deng, L.; Liang, Q.; Jia, Y.; Wang, H. High Performance Bacterial Cellulose Organogel-Based Thermoelectrochemical Cells by Organic Solvent-Driven Crystallization for Body Heat Harvest and Self-Powered Wearable Strain Sensors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2306509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, H.J.; Choi, C. Microbuckled Mechano-electrochemical Harvesting Fiber for Self-Powered Organ Motion Sensors. Nano Lett. 2022, 22, 8695–8703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Deng, H.; Li, G.; Li, X.; Pan, J.; Liu, T.; Gong, T. High-sensitivity wearable multi-signal sensor based on self-powered MXene hydrogels. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 489, 151221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Dai, L.; Hunter, L.A.; Zhang, L.; Yang, G.; Chen, J.; Zhang, X.; He, Z.; Ni, Y. A multifunctional nanocellulose-based hydrogel for strain sensing and self-powering applications. Carbohyd. Polym. 2021, 268, 118210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Zhang, X.; Lu, C. Skin-Inspired and Self-Powered Piezoionic Sensors for Smart Wearable Applications. Small 2025, 21, 2410594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Chen, X.; Dutta, A.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Z.; Xin, M.; Du, S.; Xu, G.; Cheng, H. Thermoelectric porous laser-induced graphene-based strain-temperature decoupling and self-powered sensing. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.-Y.; Chen, D.-R.; Wu, J.-K.; Wang, T.-H.; Chuang, C.; Huang, S.-Y.; Hsieh, W.-P.; Hofmann, M.; Chang, Y.-H.; Hsieh, Y.-P. Two-Dimensional Mechano-thermoelectric Heterojunctions for Self-Powered Strain Sensors. Nano Lett. 2021, 21, 6990–6997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; He, Y.; Hao, C.; Li, X.; Li, L.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, W. Versatile core-shell MnO2@PANI nanocomposites: Bridging photo-assisted zinc-ion batteries and wearable strain sensors for self-powered systems. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 696, 137860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Liang, J.; Zheng, J.; Lu, F.; Ma, Y.; Yu, H.; Zhao, W.; Wang, R.; Liu, Z. Zeolitic imidazolate framework-enhanced conductive nanocomposite hydrogels with high stretchability and low hysteresis for self-powered multifunctional sensors. J. Mater. Chem. A 2025, 13, 12256–12265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Song, H. Self-Powered Strain Sensing System: A Cutting-Edge Review Paving the Way for Autonomous Wearable Electronics. Polymers 2025, 17, 3256. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243256

Song H. Self-Powered Strain Sensing System: A Cutting-Edge Review Paving the Way for Autonomous Wearable Electronics. Polymers. 2025; 17(24):3256. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243256

Chicago/Turabian StyleSong, Hui. 2025. "Self-Powered Strain Sensing System: A Cutting-Edge Review Paving the Way for Autonomous Wearable Electronics" Polymers 17, no. 24: 3256. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243256

APA StyleSong, H. (2025). Self-Powered Strain Sensing System: A Cutting-Edge Review Paving the Way for Autonomous Wearable Electronics. Polymers, 17(24), 3256. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243256