Impact of Extrusion on Biofunctional, Rheological, Thermal, and Structural Properties of Corn Starch/Whey Protein Isolate Blends During In Vitro Gastrointestinal Digestion

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Extrusion Process

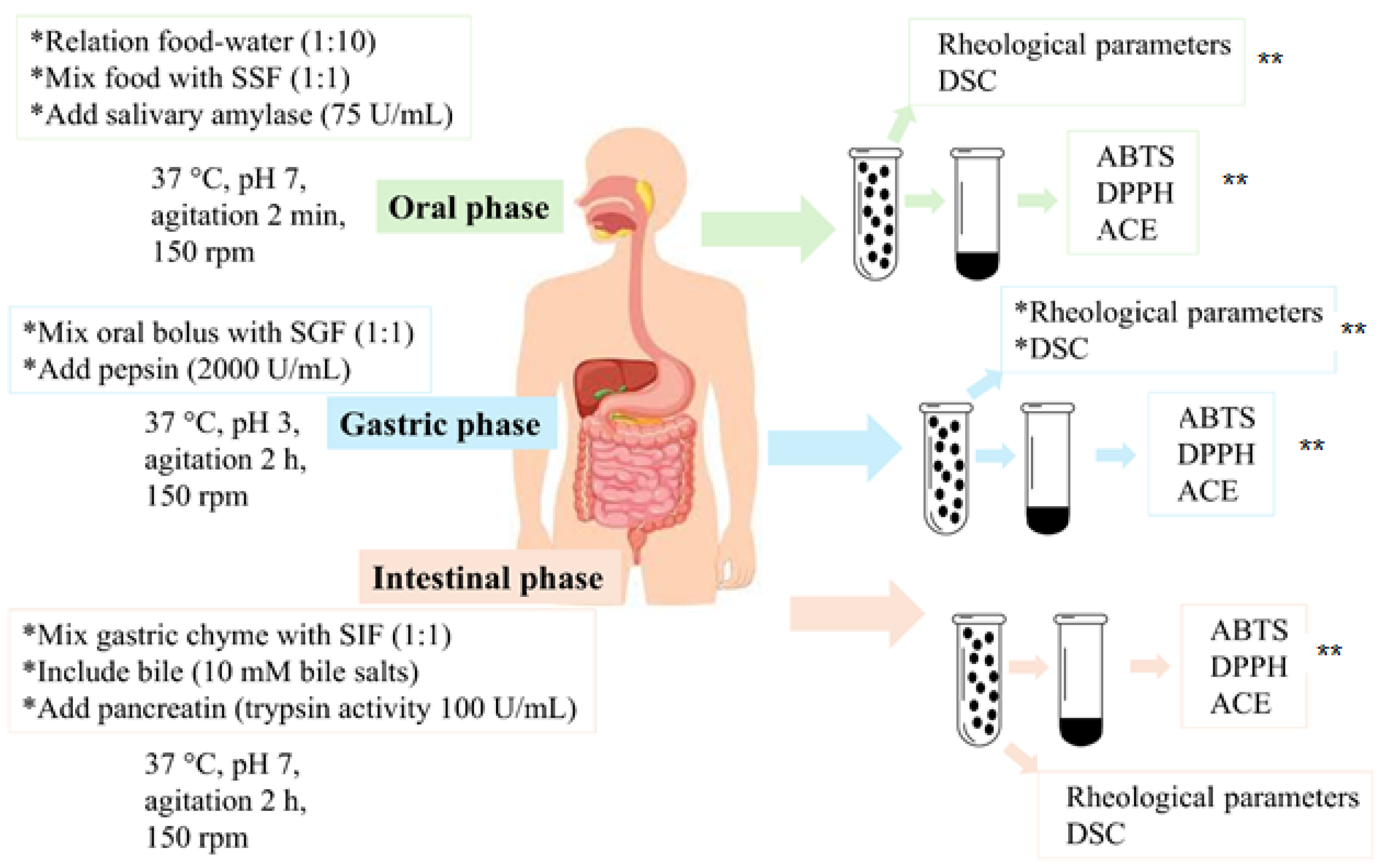

2.3. In Vitro Gastrointestinal Digestion by INFOGEST

2.4. Rheological Parameters

2.5. Antioxidant Activity by ABTS (2,2′-Azino-Bis (3-Ethylbenzothiazoline-6-Sulfonic Acid) Diammonium Salt)

2.6. Antioxidant Activity by DPPH (2,2-Diphenyl-1-Picrylhydrazyl)

2.7. ACE-I Activity Inhibition

2.8. Thermal Properties by DSC

2.9. Concentration of Secondary Proteins in WPI and the Degree of Order and Double Helix in the Fingerprint of Corn Starch by FTIR

2.10. Determination of Resistant, Digestible, and Total Starch

2.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Rheological Parameters

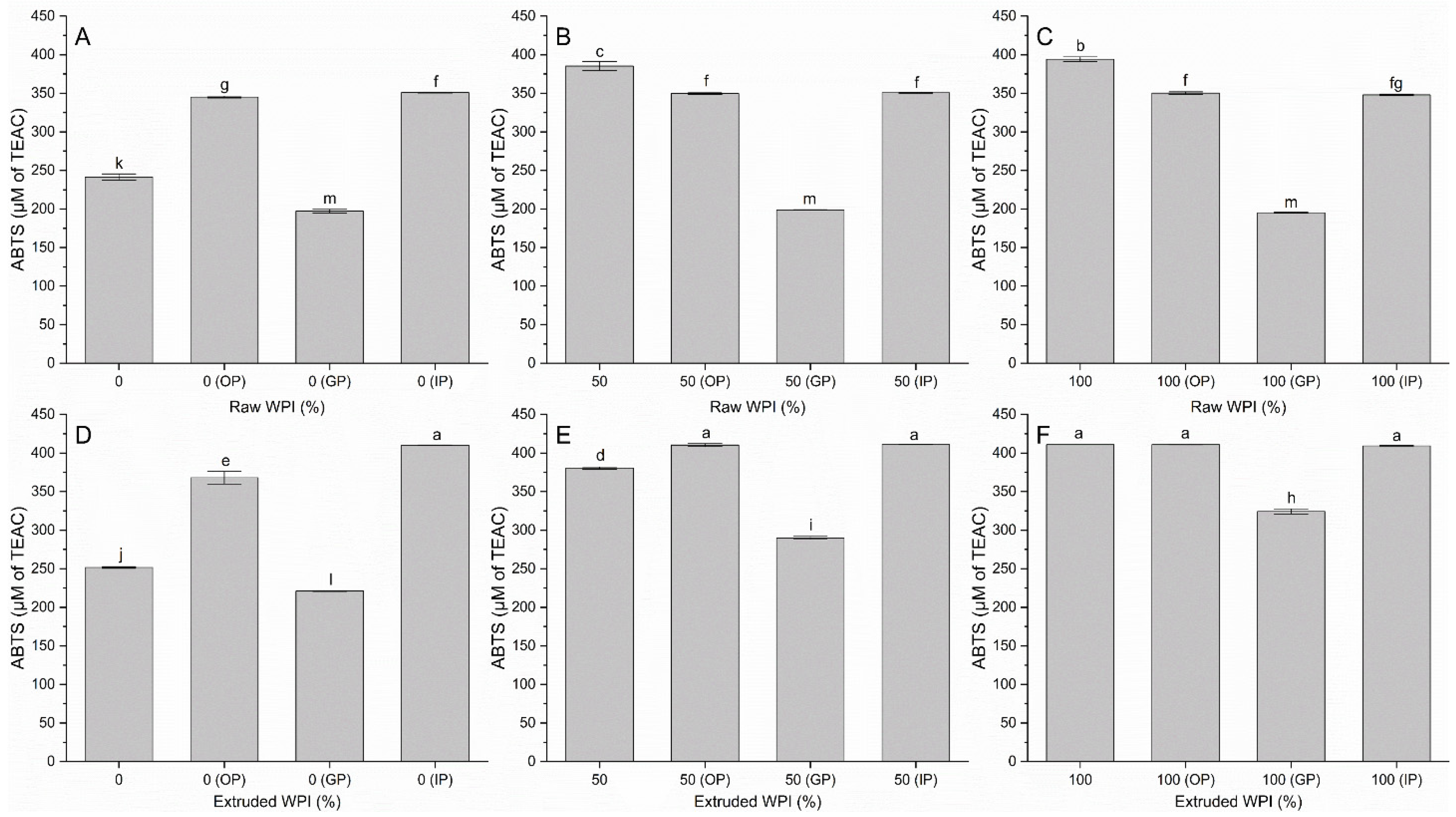

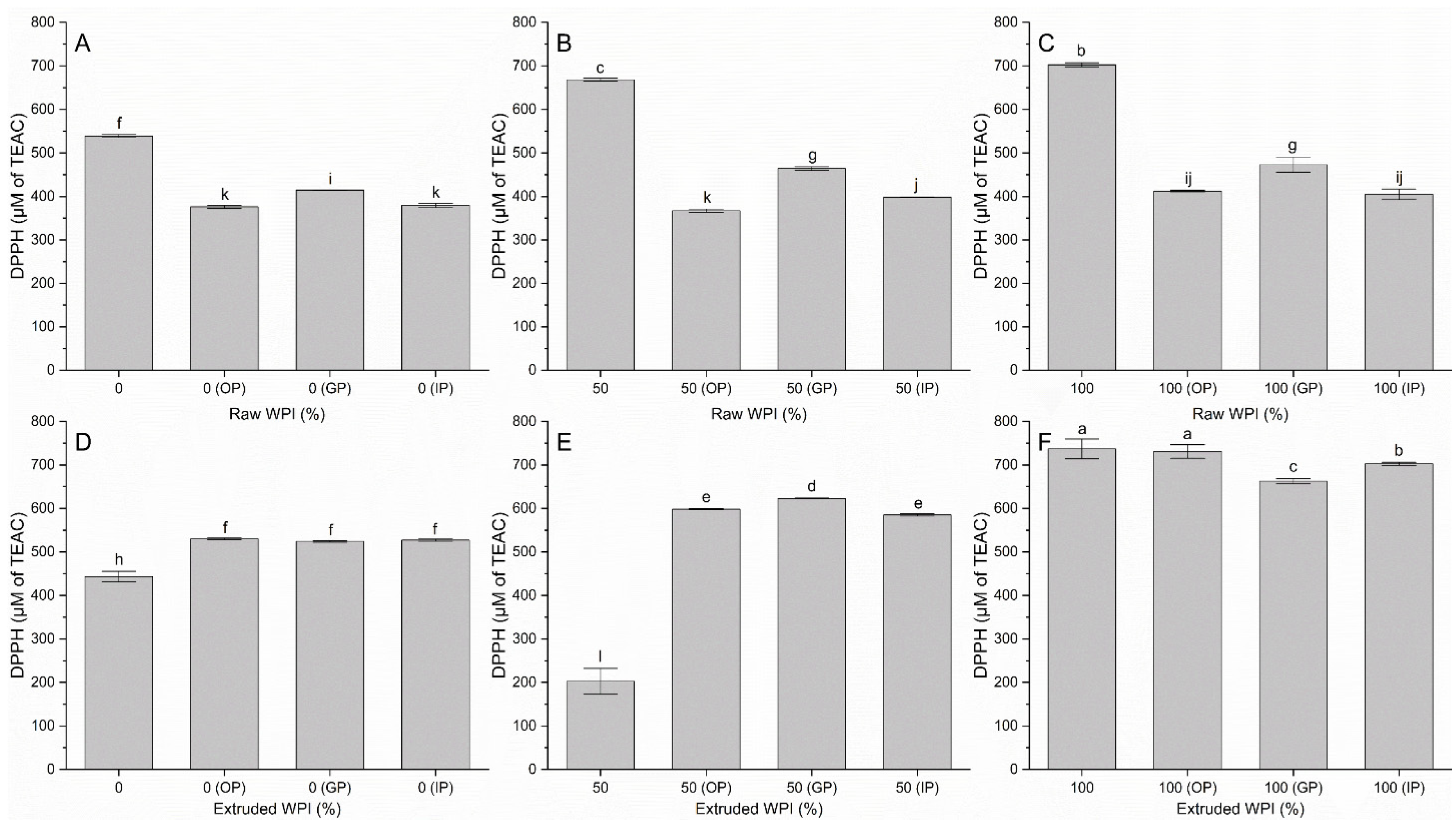

3.2. Antioxidant Activity by ABTS and DPPH

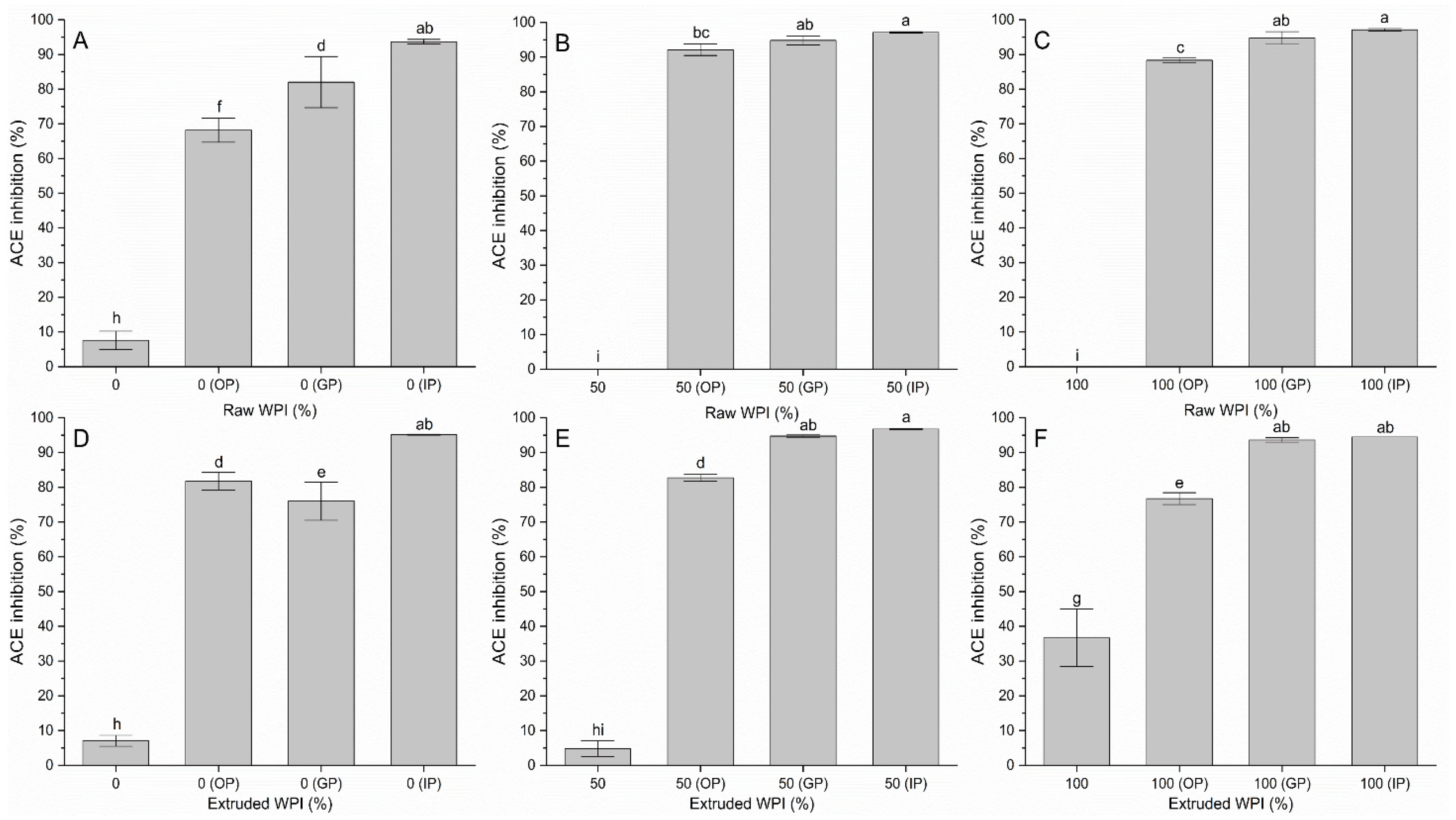

3.3. ACE-1 Activity Inhibition

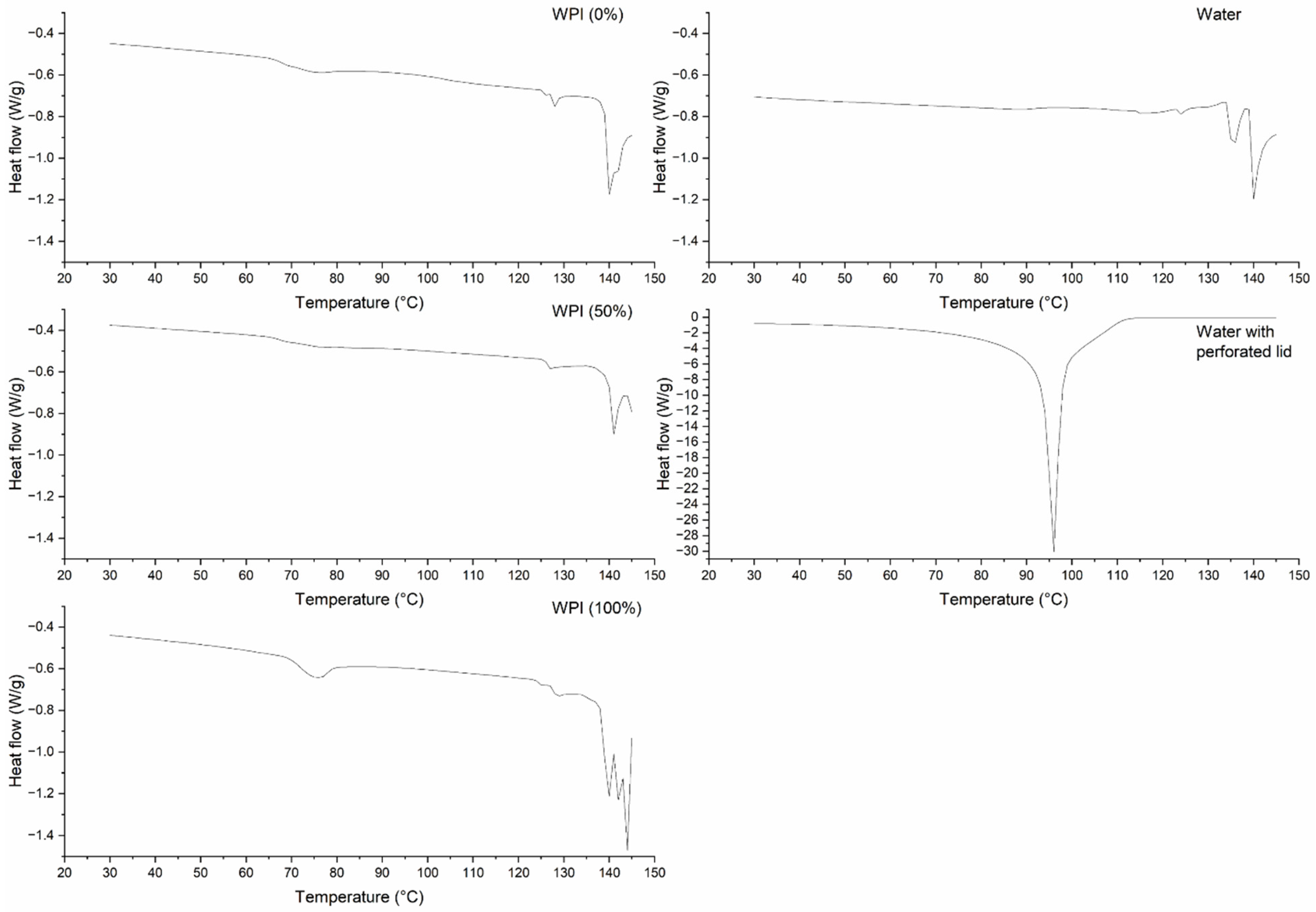

3.4. Thermal Properties by DSC

3.5. FTIR Analysis

3.6. Resistant, Digestible, and Total Starch

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brodkorb, A.; Egger, L.; Alminger, M.; Alvito, P.; Assunção, R.; Ballance, S.; Bohn, T.; Bourlieu, C.; Carrière, F.; Clemente, A.; et al. INFOGEST static in vitro simulation of gastrointestinal food digestion. Nat. Protoc. 2019, 14, 991–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dávila León, R.; González-Vázquez, M.; Lima-Villegas, K.E.; Mora-Escobedo, R.; Calderón-Domínguez, G. In vitro gastrointestinal digestion methods of carbohydrate-rich foods. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 12, 722–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czelej, M.; Garbacz, K.; Czernecki, T.; Rachwał, K.; Wawrzykowski, J.; Waśko, A. Whey protein enzymatic breakdown: Synthesis, analysis, and discovery of new biologically active peptides in papain-derived hydrolysates. Molecules 2025, 30, 1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, J.; Rao, P.; Zheng, S.; Li, G.; Han, H.; Shi, H.; Xiang, L. Mechanistic insights into the interaction of Lycium barbarum polysaccharide with whey protein isolate: Functional and structural characterization. Food Chem. 2025, 463, 141080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Ovando, B.; Calderón-Domínguez, G.; García-Garibay, M.; Jiménez-Guzmán, J.; Jardón-Valadez, E.; León-Espinosa, E.B.; Cruz-Monterrosa, R.G.; Cortés-Sánchez, A.J.; Ruíz-Hernández, R.; Díaz-Ramírez, M. β-lactoglobulin peptides obtained by chymotrypsin hydrolysis. Agro Prod. 2021, 14, 2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmiento-Torres, L.F.; Murrillo-Franco, S.L.; Galvis-Nieto, J.D.; Rodríguez, L.J.; Igual, M.; García-Segovia, P.; Orrego, C.E. Physicochemical and functional properties and in vitro digestibility of green banana flour-based snacks enriched with mango and passion fruit pulps by extrusion cooking. Int. J. Food Sci. 2025, 2025, 5204346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Téllez-Morales, J.A.; Rodríguez-Miranda, J. Improved extrusion cooking technology: A mini review of starch modification. J. Culin. Sci. Technol. 2025, 23, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Téllez-Morales, J.A.; Rodríguez-Miranda, J.; Serrano-Villa, F.S.; Calderón-Domínguez, G. Extrusion cooking analysis of corn starch and WPI mixture as a model system on the microstructure and thermodynamic parameters. LWT 2025, 192, 117963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Téllez-Morales, J.A.; Hernández-Santos, B.; Gómez-Aldapa, C.A.; Rodríguez-Miranda, J. Impact of extrusion on swelling power and foam stability in mixtures of corn starch and whey protein isolate as a model system. Emir. J. Food Agric. 2022, 34, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Téllez-Morales, J.A.; Hernández-Santos, B.; Juárez-Barrientos, J.M.; Lerdo-Reyes, A.A.; Rodríguez-Miranda, J. The use of tubers in the development of extruded snacks: A review. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2022, 46, e16693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Bao, H.; Wang, Y.; Jiao, A.; Jin, Z. Mechanisms of rice protein hydrolysate regulating the in vitro digestibility of rice starch under extrusion treatment in terms of structure, physicochemical properties and interactions. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 253, 127315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Boer, J.; Capuano, E.; Kers, J.G.; van der Goot, A.J. High-moisture extrusion enhances soy protein quality based on in vitro protein digestibility and amino acid scores. Food Res. Int. 2025, 191, 116353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Téllez-Morales, J.A.; Gómez-Aldapa, C.A.; Herman-Lara, E.; Carmona-García, R.; Rodríguez-Miranda, J. Effect of the concentrations of corn starch and whey protein isolate on the processing parameters and the physicochemical characteristics of the extrudates. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2021, 45, e15395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomás Pozo, T. Implementation and Validation of a Herschel-Bulkley PFEM Model in Kratos Multiphysics. Master’s Thesis, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, Barcelona, Spain, 2022. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/2117/365860 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Leite, A.V.; Malta, L.G.; Riccio, M.F.; Eberlin, M.N.; Pastore, G.M.; Marostica Junior, M.R. Antioxidant potential of rat plasma by administration of freeze-dried jaboticaba peel (Myrciaria jaboticaba Vell Berg). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 2277–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobo-García, G.; Davidov-Pardo, G.; Arroqui, C.; Vírseda, P.; Marín-Arroyo, M.R.; Navarro, M. Intra-laboratory validation of microplate methods for total phenolic content and antioxidant activity on polyphenolic extracts, and comparison with conventional spectrophotometric methods. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2015, 95, 204–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Miranda, M.; Ribotta, P.D.; Silva-González, A.Z.Z.; Salgado-Cruz, M.D.L.P.; Andraca-Adame, J.A.; Chanona-Pérez, J.J.; Calderón-Domínguez, G. Morphometric and crystallinity changes on jicama starch (Pachyrizus erosus) during gelatinization and their relation with in vitro glycemic index. Starch-Stärke 2017, 69, 1600281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Liang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Hao, S.; Han, H.; Du, P.; Liu, T.; Liu, L. Ultrasonic modification of whey protein isolate: Implications for the structural and functional properties. LWT 2021, 152, 112272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Xing, J.J.; An, N.N.; Li, D.; Wang, L.J.; Wang, Y. Succeeded high-temperature acid hydrolysis of granular maize starch by introducing heat-moisture pre-treatment. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 222, 2868–2877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darby, R.; Chhabra, R.P. Chemical Engineering Fluid Mechanics, 3rd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, L.; Brennan, M.; Zheng, H.; Brennan, C. The effects of dairy ingredients on the pasting, textural, rheological, freeze-thaw properties and swelling behaviour of oat starch. Food Chem. 2018, 245, 518–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, L.; Huang, J.; Zhao, L.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Wei, C. Effect of granule size on the properties of lotus rhizome C-type starch. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 134, 448–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasprzak, K.; Oniszczuk, T.; Wojtowicz, A.; Waksmundzka-Hajnos, M.; Olech, M.; Nowak, R.; Gadzalska, R.; Żygo, G.; Oniszczuk, A. Phenolic acid content and antioxidant properties of extruded corn snacks enriched with kale. J. Anal. Methods Chem. 2018, 2018, 7830546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, X.; Sun, X.; Zhang, J.; Mi, Y.; Li, Q.; Guo, Z. Synthesis and antioxidant activity of cationic 1,2,3-Triazole functionalized starch derivatives. Polymers 2020, 12, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.Y.; Gao, J.H.; Shi, Y.L.; Lan, Y.F.; Liu, H.M.; Zhu, W.X.; Wang, X.D. Characterization of structure and antioxidant activity of polysaccharides from sesame seed hull. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 928972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P.; Gujral, H.S.; Singh, B. Antioxidant activity of barley as affected by extrusion cooking. Food Chem. 2012, 131, 1406–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baah, R.O.; Duodu, K.G.; Emmambux, M.N. Cooking quality, nutritional and antioxidant properties of gluten-free maize–Orange-fleshed sweet potato pasta produced by extrusion. LWT 2022, 162, 113415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, E.; Wu, Z.; Pan, X.; Long, J.; Wang, F.; Xu, X.; Jin, Z.; Jiao, A. Effect of enzymatic (thermostable α-amylase) treatment on the physicochemical and antioxidant properties of extruded rice incorporated with soybean flour. Food Chem. 2016, 197, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleixandre, A.; Miguel, M.; Muguerza, B. Peptides with antihypertensive activity from milk and egg proteins. Nutr. Hosp. 2008, 23, 313–318. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Hernández, G.; Rentería-Monterrubio, A.L.; Rodríguez-Figueroa, J.C.; Chávez-Martínez, A. Bioactive peptides in milk and their derivatives: Functionality and health benefits. Ecosist. Recur. Agropecu. 2014, 1, 281–294. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.; Zhong, F.; Goff, H.D.; Li, Y. Study on starch-protein interactions and their effects on physicochemical and digestible properties of the blends. Food Chem. 2019, 280, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Zhu, W.; Yi, J.; Liu, N.; Cao, Y.; Lu, J.; Cui, Y.; McClements, D.J. Effects of sonication on the physicochemical and functional properties of walnut protein isolate. Food Res. Int. 2018, 106, 853–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Jia, J.; Yang, Y.; Ge, S.; Song, X.; Yu, J.; Wu, Q. Structural change and functional improvement of wheat germ protein promoted by extrusion. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 137, 108389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; Ren, X.; Qu, W.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, Y.; Ma, H. The impact of ultrasound duration on the structure of β-lactoglobulin. J. Food Eng. 2021, 292, 110365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marta, H.; Hasya, H.N.L.; Lestari, Z.I.; Cahyana, Y.; Arifin, H.R.; Nurhasanah, S. Study of changes in crystallinity and functional properties of modified sago starch (Metroxylon sp.) using physical and chemical treatment. Polymers 2022, 14, 4845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, Q.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, S.; Jin, Z.; Zhu, K.; Zhang, M.; Jiao, A. Effects of whey protein on the in vitro digestibility and physicochemical properties of potato starch. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 193, 1744–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kembabazi, S.; Mutambuka, M.; Zawawi, N.; Mugampoza, E.; Shukri, R.; Muranga, F.I. Optimizing extrusion for maximum resistant starch: Unlocking the potential of banana flour. Meas. Food 2025, 9, 100238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Raw WPI 0% | Extruded WPI 0% | Raw WPI 50% | Extruded WPI 50% | Raw WPI 100% | Extruded WPI 100% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| σy (Mpa) | 1.32 × 10−9 ± 6.79 × 10−10 | 2.13 × 10−4 ± 3.88 × 10−4 | 1.03 × 10−9 ± 3.19 × 10−9 | 4.15 × 10−6 ± 2.36 × 10−6 | 4.09 × 10−9 ± 3.17 × 10−9 | 1.11 × 10−5 ± 1.64 × 10−5 |

| k (Pa.s) | 5.011 × 10−4 ± 2.31 × 10−4 | 2.48 × 102 ± 3.61 × 102 | 3.27 × 10−3 ± 4.50 × 10−3 | 1.04 × 10−1 ± 9.26 × 10−2 | 9.09 × 10−4 ± 3.89 × 10−4 | 1.69 × 10 ± 2.37 × 10 |

| n | 1.12 ± 0.14 | 0.59 ± 0.81 | 0.89 ± 0.35 | 1.21 ± 0.68 | 1.11 ± 0.10 | 1.12 ± 0.09 |

| R2 | 0.999 ± 0.001 | 0.928 ± 0.042 | 0.989 ± 0.017 | 0.940 ± 0.090 | 0.998 ± 0.002 | 0.465 ± 0.512 |

| Oral phase | ||||||

| σy (Mpa) | 2.89 × 10−10 ± 8.08 × 10−10 | 3.17 × 10−7 ± 5.77 × 10−7 | 1.56 × 10−9 ± 5.32 × 10−10 | 8.79 × 10−10 ± 3.24 × 10−9 | 2.21 × 10−9 ± 2.95 × 10−9 | 4.93 × 10−9 ± 1.09 × 10−8 |

| k (Pa.s) | 9.64 × 10−4 ± 5.95 × 10−4 | 3.00 × 10−1 ± 5.04 × 10−1 | 8.49 × 10−4 ± 4.86 × 10−4 | 5.83 × 10−3 ± 1.76 × 10−3 | 7.28 × 10−4 ± 3.01 × 10−4 | 3.52 × 10−3 ± 1.99 × 10−3 |

| n | 1.00 ± 0.14 | 0.57 ± 0.48 | 1.00 ± 0.11 | 0.72 ± 0.06 | 1.03 ± 0.11 | 0.76 ± 0.15 |

| R2 | 0.998 ± 0.001 | 0.983 ± 0.016 | 0.998 ± 0.001 | 0.999 ± 0.001 | 0.997 ± 0.002 | 0.993 ± 0.009 |

| Gastric phase | ||||||

| σy (Mpa) | 2.38 × 10−9 ± 2.27 × 10−9 | 1.57 × 10−7 ± 1.15 × 10−6 | 2.09 × 10−9 ± 1.31 × 10−9 | 2.81 × 10−8 ± 5.72 × 10−8 | 6.59 × 10−10 ± 3.47 × 10−10 | 3.81 × 10−8 ± 6.52 × 10−8 |

| k (Pa.s) | 2.27 × 10−3 ± 1.57 × 10−3 | 4.31 × 10−1 ± 6.05 × 10−1 | 7.63 × 10−4 ± 3.14 × 10−4 | 3.87 × 10−3 ± 5.33 × 10−3 | 1.10 × 10−3 ± 2.67 × 10−4 | 4.22 × 10−2 ± 5.44 × 10−2 |

| n | 0.80 ± 0.18 | 0.85 ± 0.89 | 0.97 ± 0.12 | 2.61 ± 3.26 | 0.89 ± 0.04 | 0.43 ± 0.38 |

| R2 | 0.997 ± 0.001 | 0.837 ± 0.117 | 0.996 ± 0.005 | 0.961 ± 0.062 | 0.998 ± 0.003 | 0.959 ± 0.026 |

| Intestinal phase | ||||||

| σy (Mpa) | 1.38 × 10−9 ± 1.09 × 10−9 | 6.51 × 10−10 ± 1.25 × 10−9 | 9.03 × 10−10 ± 7.38 × 10−10 | 1.22 × 10−9 ± 9.33 × 10−10 | 9.48 × 10−5 ± 1.64 × 10−4 | 1.45 × 10−10 ± 3.31 × 10−10 |

| k (Pa.s) | 6.80 × 10−4 ± 1.06 × 10−4 | 1.26 × 10−3 ± 3.68 × 10−4 | 5.27 × 10−4 ± 1.10 × 10−4 | 6.96 × 10−4 ± 2.10 × 10−4 | 9.48 × 10 ± 1.64 × 102 | 7.40 × 10−4 ± 9.58 × 10−5 |

| n | 1.02 ± 0.04 | 0.88 ± 0.06 | 1.09 ± 0.05 | 1.04 ± 0.08 | 0.23 ± 0.20 | 0.99 ± 0.03 |

| R2 | 0.996 ± 0.003 | 0.998 ± 0.002 | 0.999 ± 0.001 | 0.997 ± 0.001 | 0.998 ± 0.002 | 0.999 ± 0.002 |

| Parameters | Raw WPI 0% | Extruded WPI 0% | Raw WPI 50% | Extruded WPI 50% | Raw WPI 100% | Extruded WPI 100% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral phase | ||||||

| To (°C) | 65.55 ± 0.322 a | -- | 66.87 ± 1.421 a | -- | -- | -- |

| Tp (°C) | 72.03 ± 0.146 a | -- | 72.99 ± 1.110 a | -- | -- | -- |

| Tc (°C) | 88.29 ± 0.580 a | -- | 84.49 ± 1.598 b | -- | -- | -- |

| ∆H (J/g) | 0.42 ± 0.094 a | -- | 0.12 ± 0.039 b | -- | -- | -- |

| Gelatinization (%) | 100 ± 0.000 a | -- | 100 ± 0.000 a | -- | -- | -- |

| Gastric phase | ||||||

| To (°C) | 69.09 ± 0.159 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Tp (°C) | 75.17 ± 0.160 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Tc (°C) | 86.55 ± 0.634 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| ∆H (J/g) | 0.30 ± 0.045 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Gelatinization (%) | 100 ± 0.000 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Parameters (For WPI) | Raw WPI 50% | Extruded WPI 50% | Area Reduction (%) | Raw WPI 100% | Extruded WPI 100% | Area Reduction (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-sheet (%) (1610–1640 cm−1) | 38.72 | 38.33 | 19.14 | 31.91 | 35.48 | 44.37 |

| Random coil (%) (1640–1650 cm−1) | 11.52 | 10.37 | 26.50 | 8.10 | 13.09 | 19.15 |

| α-helix (%) (1650–1664 cm−1) | 23.57 | 23.57 | 18.35 | 22.67 | 21.74 | 52.02 |

| β-turn (%) (1664–1695 cm−1) | 26.19 | 27.73 | 13.52 | 37.32 | 29.70 | 60.18 |

| Parameters (For CS) | Raw WPI 0% | Extruded WPI 0% | Raw WPI 50% | Extruded WPI 50% | ||

| Double helix degree (995/1022 cm−1) | 1.22 | 1.14 | 1.17 | 1.04 | ||

| Degree of order (1047/1022 cm−1) | 0.65 | 0.62 | 0.70 | 0.61 |

| Parameters (g/100 g dwb) | Raw WPI 0% | Extruded WPI 0% | Raw WPI 50% | Extruded WPI 50% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resistant starch | 0.08 ± 0.018 c | 0.49 ± 0.098 a | 0.26 ± 0.073 b | 0.25 ± 0.076 b |

| Digestible starch | 98.67 ± 2.496 a | 92.12 ± 1.612 b | 42.51 ± 0.588 d | 45.95 ± 2.656 c |

| Total starch | 98.75 ± 2.504 a | 92.60 ± 1.673 b | 42.77 ± 0.623 d | 46.20 ± 2.689 c |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Téllez-Morales, J.A.; Rodríguez-Miranda, J.; Serrano-Villa, F.S.; Gutiérrez-López, G.F.; Farrera-Rebollo, R.R.; Calderón-Domínguez, G. Impact of Extrusion on Biofunctional, Rheological, Thermal, and Structural Properties of Corn Starch/Whey Protein Isolate Blends During In Vitro Gastrointestinal Digestion. Polymers 2025, 17, 3211. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233211

Téllez-Morales JA, Rodríguez-Miranda J, Serrano-Villa FS, Gutiérrez-López GF, Farrera-Rebollo RR, Calderón-Domínguez G. Impact of Extrusion on Biofunctional, Rheological, Thermal, and Structural Properties of Corn Starch/Whey Protein Isolate Blends During In Vitro Gastrointestinal Digestion. Polymers. 2025; 17(23):3211. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233211

Chicago/Turabian StyleTéllez-Morales, José A., Jesús Rodríguez-Miranda, Fátima S. Serrano-Villa, Gustavo F. Gutiérrez-López, Reynold R. Farrera-Rebollo, and Georgina Calderón-Domínguez. 2025. "Impact of Extrusion on Biofunctional, Rheological, Thermal, and Structural Properties of Corn Starch/Whey Protein Isolate Blends During In Vitro Gastrointestinal Digestion" Polymers 17, no. 23: 3211. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233211

APA StyleTéllez-Morales, J. A., Rodríguez-Miranda, J., Serrano-Villa, F. S., Gutiérrez-López, G. F., Farrera-Rebollo, R. R., & Calderón-Domínguez, G. (2025). Impact of Extrusion on Biofunctional, Rheological, Thermal, and Structural Properties of Corn Starch/Whey Protein Isolate Blends During In Vitro Gastrointestinal Digestion. Polymers, 17(23), 3211. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233211