Study on the Tensile Properties and Waterproofing Mechanism of Bamboo Fibers Treated by Different Methods

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Material Properties and Selection Criteria for Natural Bamboo Fibers

2.2. Materials and Treatments

- (a)

- Sodium hydroxide (NaOH) solution treatment

- (b)

- Vegetable oil treatment

- (c)

- XSBR treatment

- (d)

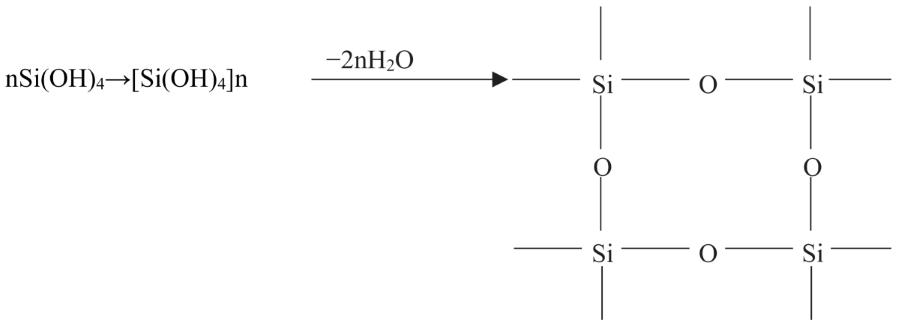

- Sodium silicate solution treatment

3. Testing

3.1. Water Immersion Softening Test

3.2. Direct Tensile Test

3.3. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) Analysis

3.4. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) Analysis

4. Results and Analysis

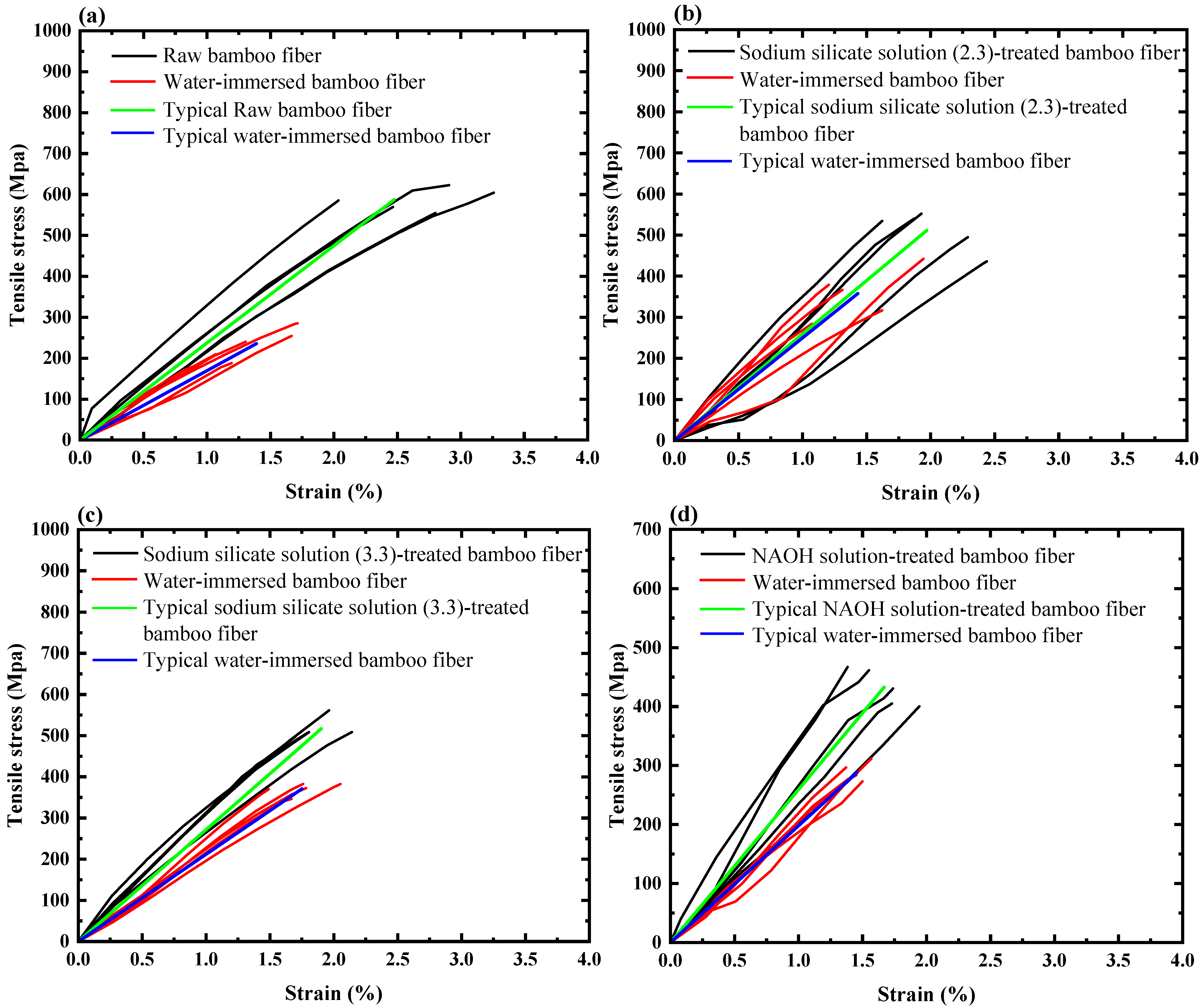

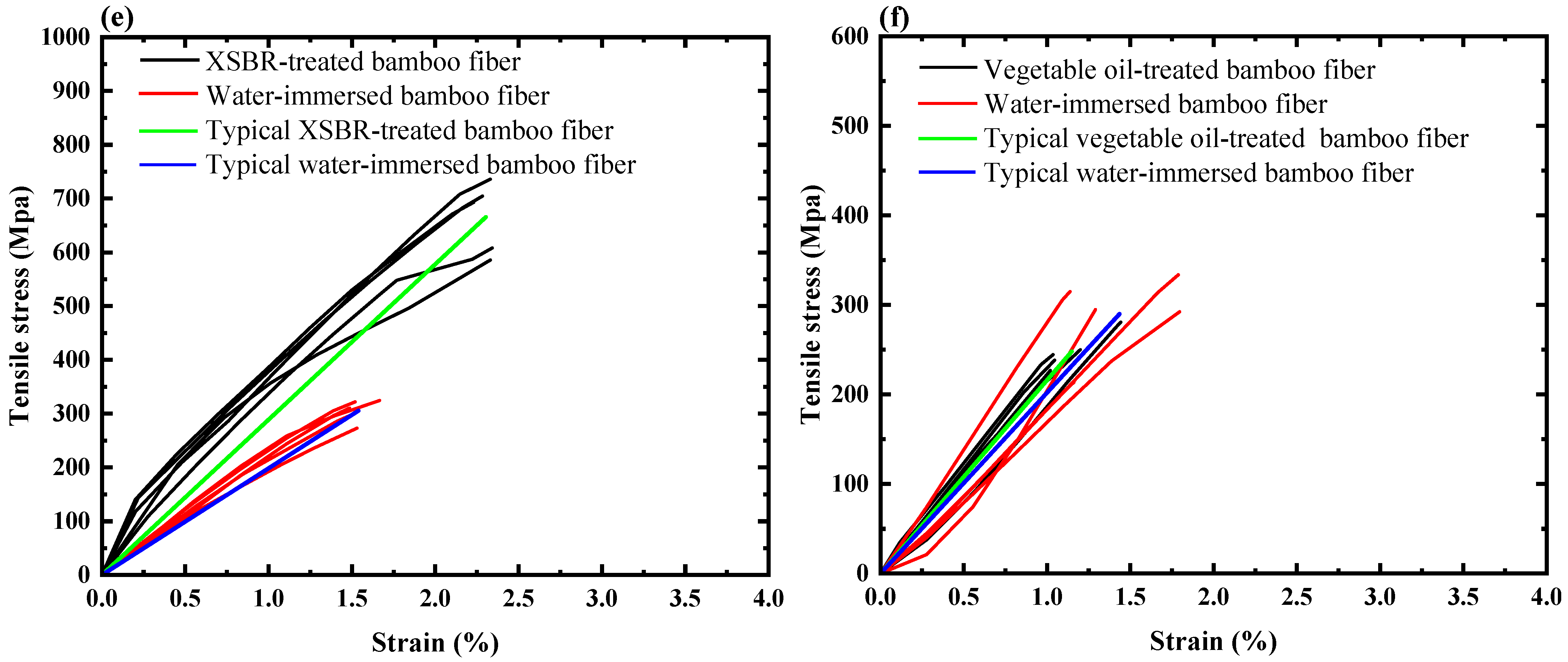

4.1. Tensile Strength Analysis

4.2. Chemical Composition Analysis

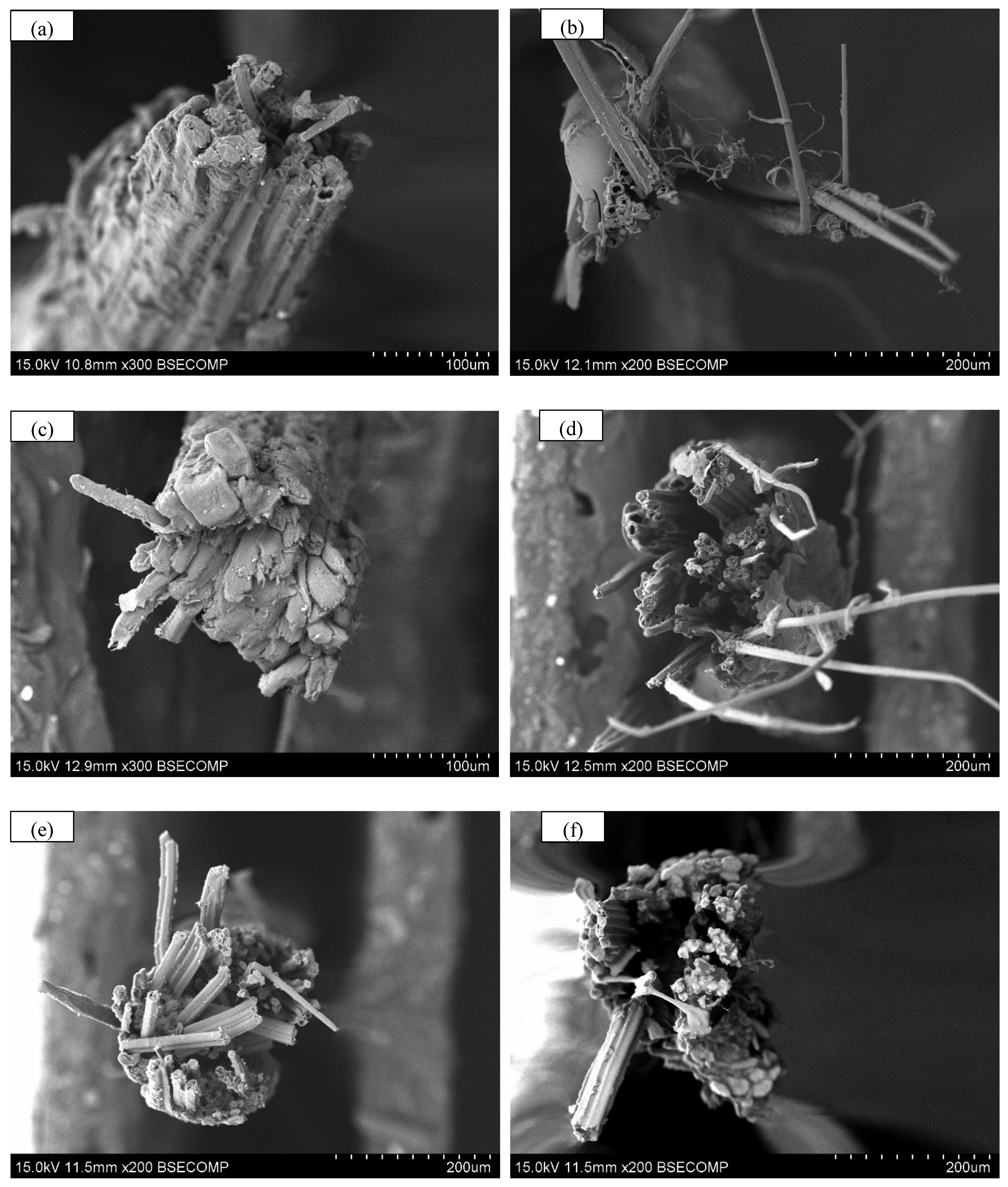

4.3. Microstructural Characterization

4.3.1. Surface Morphological Characteristics of Bamboo Fibers

4.3.2. Morphological Characteristics of Mechanically Cut and Tensile-Fractured Surfaces

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- Direct tensile tests indicate that XSBR-treated bamboo fibers exhibit the most favorable mechanical properties before water immersion, compared with raw bamboo fibers, with a 13.3% and 21.7% increment in tensile strength and Young’s modulus, respectively. After water immersion, mechanical indicators of raw bamboo fibers before water immersion are adopted as a benchmark; all treatment methods result in reduced tensile strength due to water absorption. Bamboo fibers treated with sodium silicate solution (modulus = 3.3) show the smallest reduction in tensile strength, with a value of 36.8%. For Young’s modulus, only the sodium silicate solution (modulus = 2.3) treatment maintains an increment of 4.5%, while all other methods result in a decrement. From the perspective of cost, environmental performance, and mechanical properties, sodium silicate solution is the most promising treatment method for bamboo fibers.

- Among the treatment methods, sodium silicate solution forms Si-O bonds during thermal curing, resulting in a densely crosslinked Si-O-Si solidified layer on the bamboo fiber surface. Based on the results of the tensile strength reduction rate, the solidified sodium silicate layer exhibits superior waterproofing performance compared to the XSBR gel layer.

- The tensile fracture surface of raw bamboo fibers is relatively smooth without an evident necking phenomenon. In contrast, the tensile fracture surface of the treated bamboo fibers shows different lengths of fiber bundles and presents an umbrella-shaped explosive morphology. Mechanically, this is reflected in lower strain values of the treated bamboo fibers compared to the raw bamboo fibers.

- In practical engineering applications, bamboo fiber exhibits considerable potential as a sustainable construction material, with applications including soil reinforcement to improve shear strength, concrete toughening additives, and reinforcement in geopolymer composites. However, the application of bamboo fiber is consistently hindered by high water absorption capacity, which leads to bamboo fiber softening and then significantly affects the mechanical performance and long-term durability of composite materials. This study offers a feasible solution for the application of bamboo fibers in construction engineering.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kumarasamy, K.; Shyamala, G.; Gebreyowhanse, H.; Kumarasamy. Strength properties of bamboo fiber reinforced concrete. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 981, 032063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, L.D.; Zulkornain, A.S. Influence of bamboo in concrete and beam applications. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1349, 012127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.A.; Alomayri, T.; Ali, B.; Sultan, T.; Yosri, A. Influence of hybrid coir-steel fibres on the mechanical behaviour of high-performance concrete: Step towards a novel and eco-friendly hybrid-fibre reinforced concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 389, 131728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, W.; Farooq, S.H.; Usman, M.; Khan, M.; Ahmad, A.; Aslam, F.; Al Yousef, R.; Al Abduljabbar, H.; Sufian, M. Effect of coconut fiber length and content on properties of high strength concrete. Materials 2020, 13, 1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.; Ali, M. Improvement in concrete behavior with fly ash, silica-fume and coconut fibres. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 203, 174–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiñones-Bolaños, E.; Gómez-Oviedo, M.; Mouthon-Bello, J.; Sierra-Vitola, L.; Berardi, U.; Bustillo-Lecompte, C. Potential use of coconut fibre modified mortars to enhance thermal comfort in low-income housing. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 277, 111503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.S.; Ahmed, S.J.U. Influence of jute fiber on concrete properties. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 189, 768–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, M.; Ahmed, M.; Hoque, M.M.; Islam, S. Scope of using jute fiber for the reinforcement of concrete material. Text. Cloth. Sustain. 2017, 2, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yin, Y.; Shi, L.; Bian, H.; Shi, W. Experimental investigation on mechanical behavior of sands treated by enzyme-induced calcium carbonate precipitation with assistance of sisal-fiber nucleation. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 10, 992474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.A.; Gowthaman, S.; Nakashima, K.; Kawasaki, S. The influence of the addition of plant-based natural fibers (Jute) on biocemented sand using MICP method. Materials 2020, 13, 4198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, S.; Sheng, Y.; Wang, Z.; Jia, H.; Qiu, W.; Temitope, A.A.; Xu, Z. Effect of the fiber surface treatment on the mechanical performance of bamboo fiber modified asphalt binder. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 347, 128453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadivar, M.; Gauss, C.; Ghavami, K.; Savastano, H. Densification of bamboo: State of the art. Materials 2020, 13, 4346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muhammad, A.; Rahman, M.R.; Hamdan, S.; Sanaullah, K. Recent developments in bamboo fiber-based composites: A review. Polym. Bull. 2019, 76, 2655–2682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rassiah, K.; Ahmad, M. A review on mechanical properties of bamboo fiber reinforced polymer composite. Aust. J. Basic. Appl. Sci. 2013, 7, 247–253. [Google Scholar]

- Chou, T.N.; Young, W.B. Strength of untreated and alkali-treated bamboo fibers and reinforcing effects for short fiber composites. J. Aeronaut. Astronaut. Aviat. 2018, 50, 237–246. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, H.H.; Young, W.B. The longitudinal and transverse tensile properties of unidirectional and bidirectional bamboo fiber reinforced composites. Fiber. Polym. 2020, 21, 2938–2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.H.; Wu, K.J.; Young, W.B. The effect of densification on bamboo fiber and bamboo fiber composites. Cellulose 2023, 30, 4575–4585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Shi, S.Q.; Wang, J.; Yu, Y.; Cao, S.; Cheng, H. Tensile properties of four types of individual cellulosic fibers. Wood Fiber Sci. 2011, 43, 353–364. [Google Scholar]

- Terai, M.; Minami, K. Fracture behavior and mechanical properties of bamboo fiber reinforced concrete. Key Eng. Mater. 2012, 488, 214–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaswamy, H.S.; Ahuja, B.M.; Krishnamoorthy, S. Behaviour of concrete reinforced with jute, coir and bamboo fibres. Int. J. Cem. Compos. Light. Concr. 1983, 5, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, S.C.; Moh, J.N.S.; Doh, S.I.; Yahaya, F.M.; Gimbun, J. Strengthening of reinforced concrete beams using bamboo fiber/epoxy composite plates in flexure. Key Eng. Mater. 2019, 821, 465–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinyemi, A.B.; Omoniyi, E.T.; Onuzulike, G. Effect of microwave assisted alkali pretreatment and other pretreatment methods on some properties of bamboo fibre reinforced cement composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 245, 118405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Echeverri, L.A.; Ganjian, E.; Medina-Perilla, J.A.; Quintana, G.; Sanchez-Toro, J.; Tyrer, M. Mechanical refining combined with chemical treatment for the processing of Bamboo fibres to produce efficient cement composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 269, 121232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Sun, Y.; Musso, F. Hygrothermal performance of natural bamboo fiber and bamboo charcoal as local construction infills in building envelope. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 177, 342–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, Z.; Yu, Z.; Yu, Y. Isolating nanocellulose fibrills from bamboo parenchymal cells with high intensity ultrasonication. Holzforschung 2016, 70, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehra, S.R.; Uppal, H.L.; Chadda, L.R. Some preliminary investigations in the use of bamboo for reinforcing concrete. Indian Concr. J. 1951, 25, 20–21. [Google Scholar]

- Subrahmanyam, B.V. Bamboo Reinforcement for Cement Matrices in New Reinforced Concrete; Surrey University Press: Guildford, UK, 1984; pp. 141–194. [Google Scholar]

- Bui, Q.B.; Grillet, A.C.; Tran, H.D. A bamboo treatment procedure: Effects on the durability and mechanical performance. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Wei, J.; Bao, M.; Yu, Y.; Yu, W. Durability evaluation of outdoor scrimbers fabricated from superheated steam-treated bamboo fibrous mats. Polymers 2022, 15, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Wang, G.; Ma, X.X.; Chen, M.-L.; Fang, C.-H.; Fei, B.-H. The effect of graded fibrous structure of bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis) on its water vapor sorption isotherms. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2020, 151, 112467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathiravan, N.S.; Manojkumar, R.; Jayakumar, P.; Kumaraguru, J.; Jayanthi, V. State of art of review on bamboo reinforced concrete. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 45, 1063–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noori, A.; Lu, Y.; Saffari, P.; Liu, J.; Ke, J. The effect of mercerization on thermal and mechanical properties of bamboo fibers as a biocomposite material: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 279, 122519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Yu, Y.; Zhong, T.; Wu, Y.; Li, Y.; Wu, Z.; Fei, B. Effect of alkali treatment on microstructure and mechanical properties of individual bamboo fibers. Cellulose 2017, 24, 333–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Su, X.; Zheng, M.; Lin, J.; Tan, K.B. Enhanced properties of chitosan/hydroxypropyl methylcellulose/polyvinyl alcohol green bacteriostatic film composited with bamboo fiber and silane-modified bamboo fiber. Polym. Compos. 2022, 43, 2440–2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geremew, A.; De Winne, P.; Demissie, T.A.; De Backer, H. Surface modification of bamboo fibers through alkaline treatment: Morphological and physical characterization for composite reinforcement. J. Eng. Fibers Fabr. 2024, 19, 15589250241248764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, M.J.; Wang, S.Y. Effects of peeling and steam-heating treatment on mechanical properties and dimensional stability of oriented Phyllostachys makinoi and Phyllostachys pubescens scrimber boards. J. Wood Sci. 2018, 64, 625–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S.R.; Neto, A.R.S.; de Andrade Silva, F.; de Souza, F.G.; Filho, R.D.T. The influence of carboxylated styrene butadiene rubber coating on the mechanical performance of vegetable fibers and on their interface with a cement matrix. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 262, 120770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarov, I.; Vinogradov, M.; Palchikova, E.; Kulanchikov, Y.; Levin, I.; Procko, A.; Sinyaev, K.; Ermakov, S.; Kulichikhin, V.; Fedorova, E.; et al. The influence of conditioning baths on the structure and properties of fibers spun from cellulose with low alpha content. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 370, 124472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Z.; Xue, X.; Li, Y.; Yang, J.; He, Z.; Shen, S.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, W.; Xu, L.; Zhang, H.; et al. Experimental exploration of the waterproofing mechanism of inorganic sodium silicate-based concrete sealers. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 104, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Zhang, Y.; Zuo, Y.; Lu, J.; Yuan, G.; Wu, Y. Preparation and characterization of sodium silicate impregnated Chinese fir wood with high strength, water resistance, flame retardant and smoke suppression. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 1043–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Shukla, K.S.; Dev, T.; Dobriyal, P.B. Bamboo Preservation Techniques: A Review; INBAR: Beijing, China; ICFRE: Dehra Dun, India, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Tomak, E.D.; Topaloglu, E.; Gumuskaya, E.; Yildiz, U.C.; Ay, N. An FT-IR study of the changes in chemical composition of bamboo degraded by brown-rot fungi. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2013, 85, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C1557-20; Standard Test Method for Tensile Strength and Young’s Modulus of Fibers. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- Wang, B.; Yan, L.; Kasal, B. A review of coir fibre and coir fibre reinforced cement-based composite materials (2000–2021). J. Clean Prod. 2022, 338, 130676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, H.; Sebaibi, N.; Boutouil, M.; Levacher, D. Determination and review of physical and mechanical properties of raw and treated coconut fibers for their recycling in construction materials. Fibers 2020, 8, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M.; Chakraborty, D. Influence of alkali treatment on the fine structure and morphology of bamboo fibers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2006, 102, 5050–5056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwaikambo, L.Y.; Ansell, M.P. The effect of chemical treatment on the properties of hemp, sisal, jute and kapok for composite reinforcement. Angew. Makromol. Chem. 1999, 272, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhir, D.K.; Rashidi, A.; Bogyo, G.; Ryde, R.; Pakpour, S.; S. Milani, A. Environmental durability enhancement of natural fibres using plastination: A feasibility investigation on bamboo. Molecules 2020, 25, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calarnou, L.; Traïkia, M.; Leremboure, M.; Therias, S.; Gardette, J.-L.; Bussière, P.-O.; Malosse, L.; Dronet, S.; Besse-Hoggan, P.; Eyheraguibel, B. Study of sequential abiotic and biotic degradation of styrene butadiene rubber. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 926, 171928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, H.J.; Goyal, A.; Alhassan, S.M. Surface properties of alkylsilane treated date palm fiber. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 9760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomak, E.D.; Topaloglu, E.; Ermeydan, M.A.; Pesman, E. Testing the durability of copper based preservative treated bamboos in ground-contact for six years. Cellulose 2022, 29, 6925–6940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, M.D.F.; Medeiros, E.S.; Malmonge, J.A.; Gregorski, K.; Wood, D.; Mattoso, L.; Glenn, G.; Orts, W.; Imam, S. Cellulose nanowhiskers from coconut husk fibers: Effect of preparation conditions on their thermal and morphological behavior. Carbohydr. Polym. 2010, 81, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Cheng, X.; Cao, W.; Gong, L.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, H. Fabrication of adiabatic foam by sodium silicate with glass fiber as supporting body. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 112, 933–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adel Salih, A.; Zulkifli, R.; Azhari, C.H. Tensile properties and microstructure of single-cellulosic bamboo fiber strips after alkali treatment. Fibers 2020, 8, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Troedec, M.; Sedan, D.; Peyratout, C.; Bonnet, J.P.; Smith, A.; Guinebretiere, R.; Gloaguen, V.; Krausz, P. Influence of various chemical treatments on the composition and structure of hemp fibres. Compos. Part A 2008, 39, 514–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Composition | Cellulose (%) | Hemicellulose (%) | Lignin (%) | Acetil Groups (%) | Other Composition (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Values | 45.5–51.7 | 20.6–24.1 | 25.8–29.3 | 2.1–3.5 | <1.0 |

| Raw Bamboo Fiber | NaOH Solution | Vegetable Oil | XSBR | Sodium Silicate (Modulus = 2.3) | Sodium Silicate (Modulus = 3.3) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BI | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| AI | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| total number | 120 | |||||

| Treatment Method | State | Tensile stress (MPa) | Strain (%) | Young’s Modulus (GPa) | Tensile Strength Reduction Rate (%) | Young’s Modulus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reduction Rate (%) | ||||||

| Raw bamboo | BI | 587 ± 35.46 | 2.47 ± 0.66 | 23.74 ± 6.51 | 0 | 0 |

| AI | 235 ± 49.74 | 1.39 ± 0.32 | 16.95 ± 3.09 | 60 | 28.6 | |

| Sodium silicate solution (2.3) | BI | 511 ± 75.39 | 1.97 ± 0.40 | 25.94 ± 10.11 | 12.95 | −9.27 |

| AI | 358 ± 84.57 | 1.43 ± 0.51 | 25.02 ± 6.51 | 39.01 | −4.51 | |

| Sodium silicate solution (3.3) | BI | 517 ± 44.70 | 1.90 ± 0.24 | 27.17 ± 4.27 | 11.93 | −14.45 |

| AI | 371 ± 24.65 | 1.75 ± 0.30 | 21.19 ± 3.90 | 36.8 | 10.74 | |

| NaOH solution | BI | 433 ± 34.08 | 1.70 ± 0.28 | 25.31 ± 6.65 | 26.24 | −6.61 |

| AI | 288 ± 23.05 | 1.46 ± 0.11 | 19.70 ± 3.17 | 50.94 | 17.02 | |

| XSBR | BI | 665 ± 79.65 | 2.30 ± 0.07 | 28.90 ± 5.57 | −13.29 | −21.74 |

| AI | 305 ± 32.48 | 1.54 ± 0.13 | 19.85 ± 2.69 | 48.04 | 16.39 | |

| Vegetable oil | BI | 248 ± 32.58 | 1.15 ± 0.29 | 21.59 ± 2.03 | 57.75 | 9.06 |

| AI | 280 ± 76.49 | 1.43 ± 0.36 | 19.58 ± 5.06 | 52.3 | 17.52 |

| Treatment Method | Environmental Friendliness | Cost | Tensile Strength Before Water Immersion | Tensile Strength After Water Immersion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sodium silicate solution (2.3) | favorable | low | relatively high | relatively high |

| Sodium silicate solution (3.3) | favorable | low | relatively high | the highest |

| NaOH solution | moderate | low | relatively low | relatively low |

| XSBR | unfavorable | high | the highest | relatively low |

| Vegetable oil | favorable | moderate | the lowest | the lowest |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, C.; Cao, H.; Zhang, E.; Liu, J. Study on the Tensile Properties and Waterproofing Mechanism of Bamboo Fibers Treated by Different Methods. Polymers 2025, 17, 3146. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233146

Sun C, Cao H, Zhang E, Liu J. Study on the Tensile Properties and Waterproofing Mechanism of Bamboo Fibers Treated by Different Methods. Polymers. 2025; 17(23):3146. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233146

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Chuncheng, Haiying Cao, Enhua Zhang, and Jiefeng Liu. 2025. "Study on the Tensile Properties and Waterproofing Mechanism of Bamboo Fibers Treated by Different Methods" Polymers 17, no. 23: 3146. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233146

APA StyleSun, C., Cao, H., Zhang, E., & Liu, J. (2025). Study on the Tensile Properties and Waterproofing Mechanism of Bamboo Fibers Treated by Different Methods. Polymers, 17(23), 3146. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233146