Improved Polymer Membrane for Textile Zinc-Ion Capacitor

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material

2.2. Fabrication of Polyester Cotton Textile with Improved Polymer Membrane

2.3. Fabrication Process of Cathode and Anode

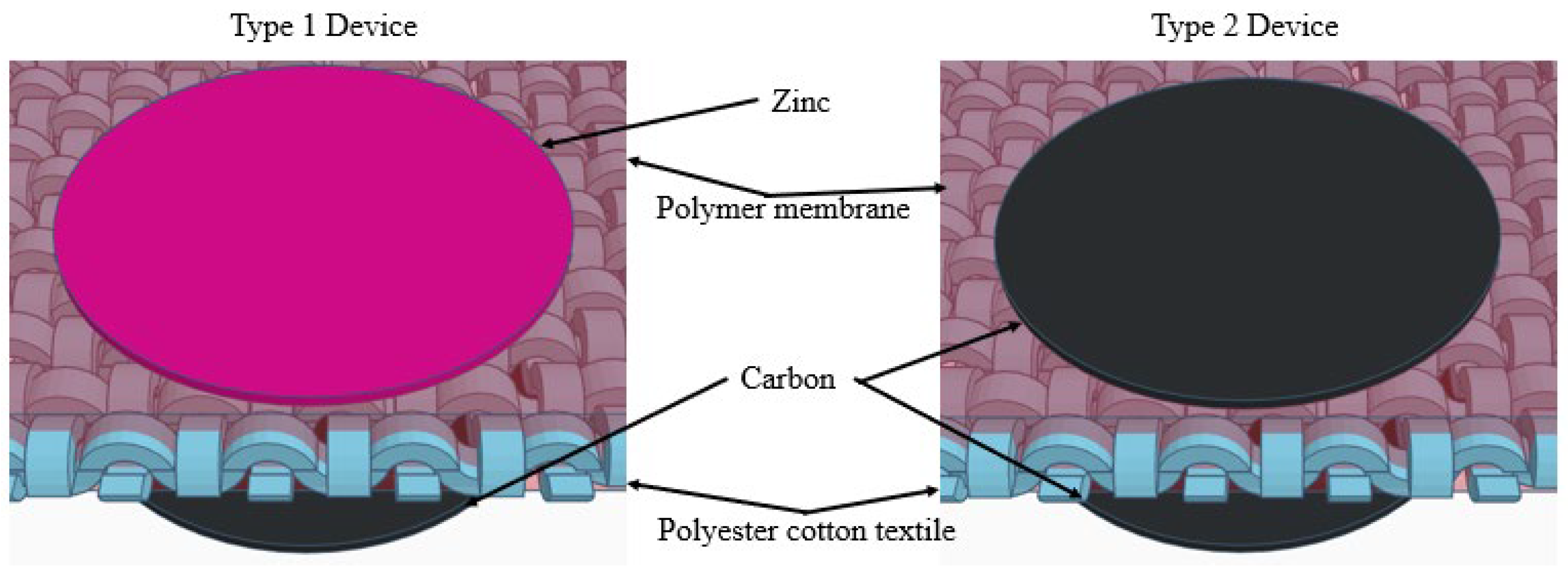

2.4. Textile ZHSC Assembly and Testing

2.5. Characterisation and Electrochemical Testing of the Membrane Textile and ZHSC

3. Results

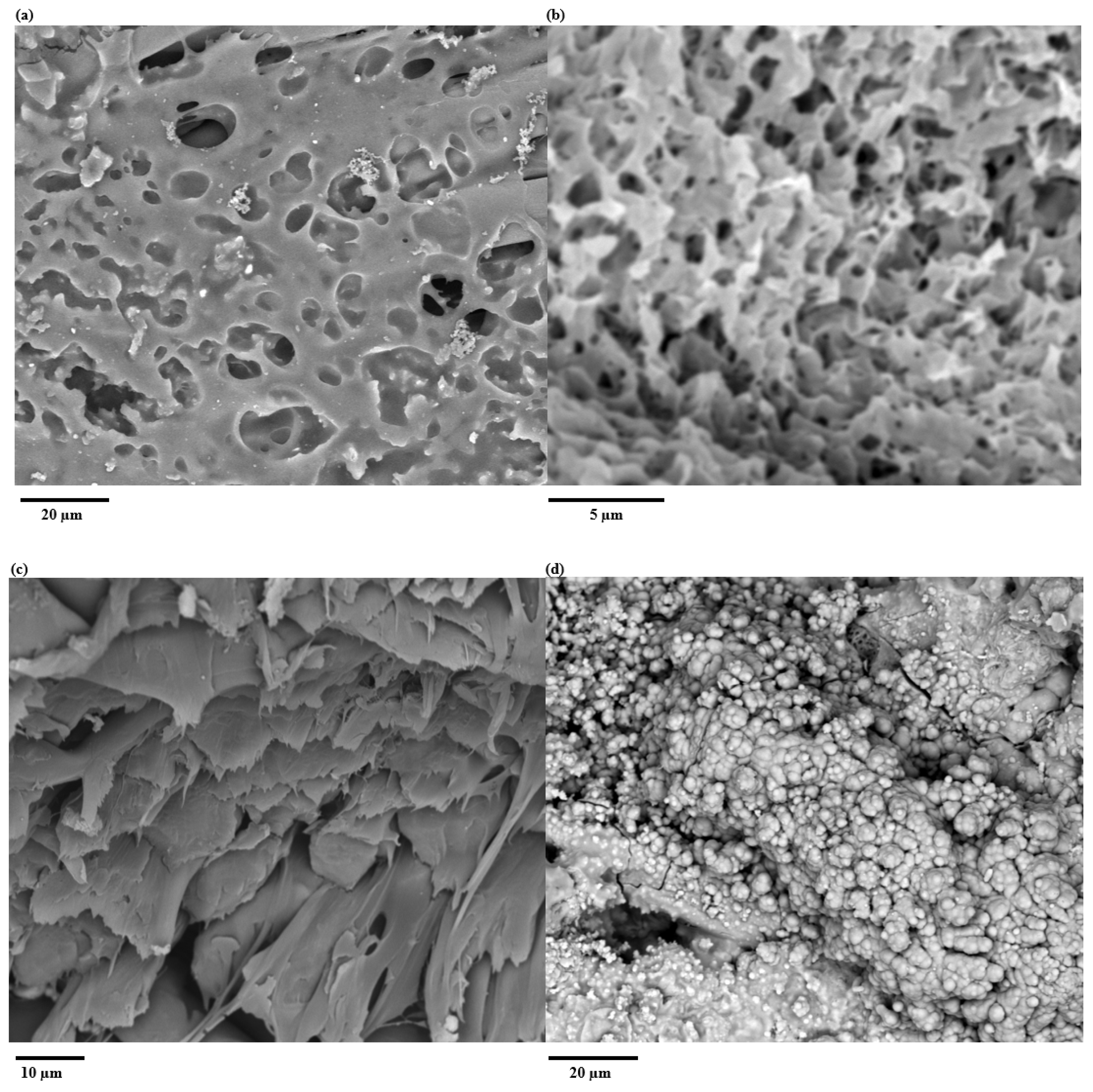

3.1. SEM Imaging

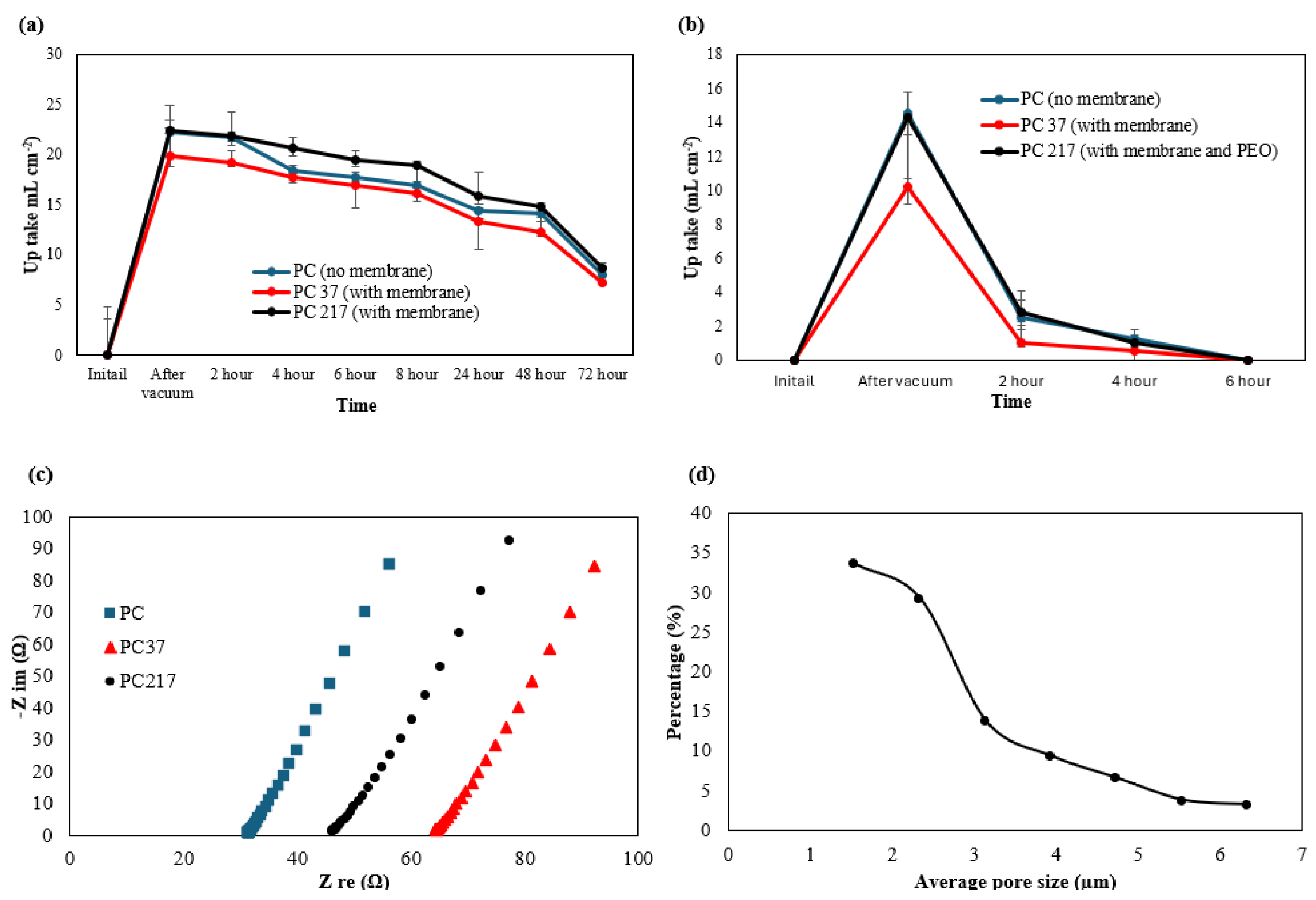

3.2. Porosity, Electrolyte Uptake and Ageing Test

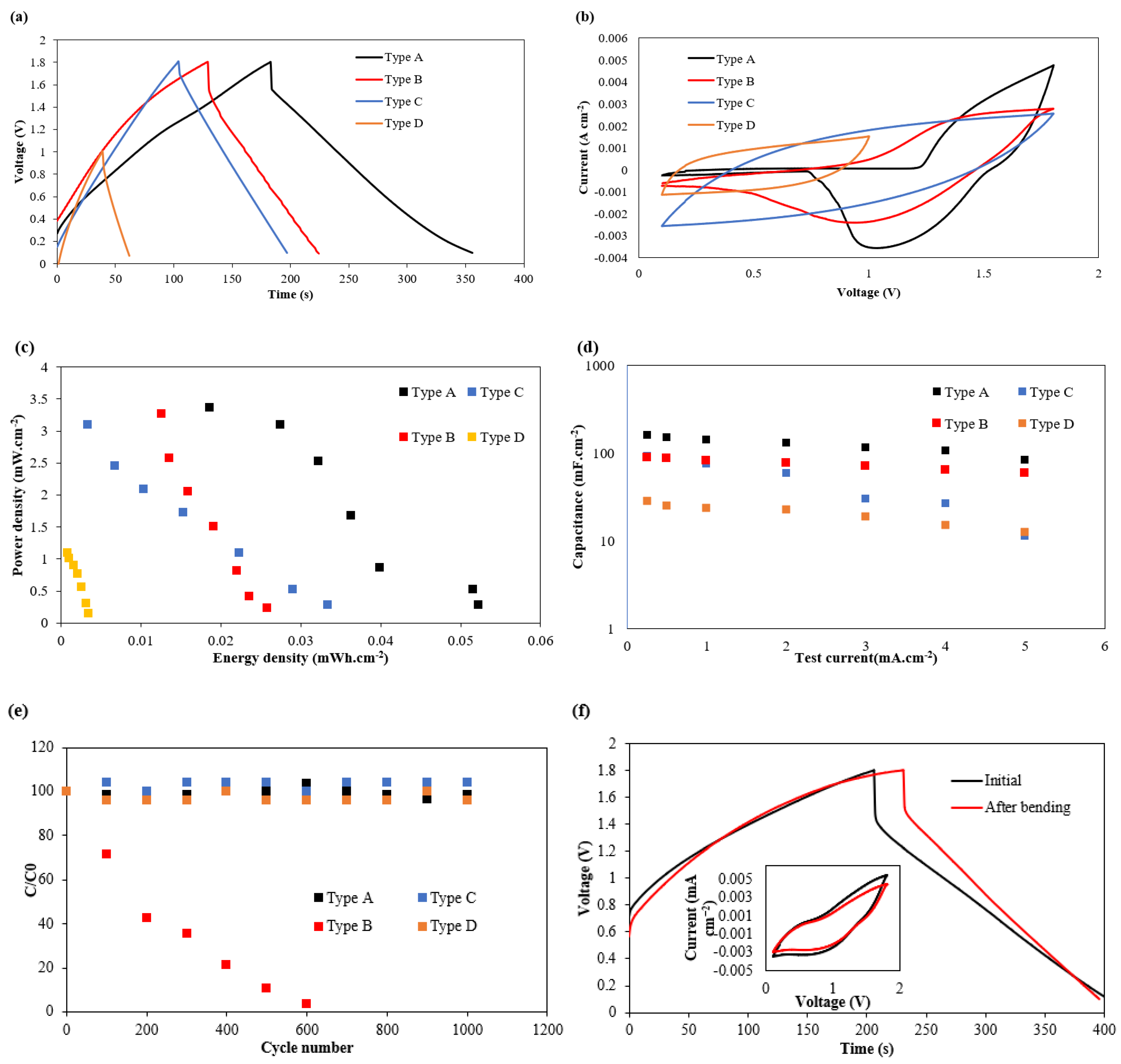

3.3. Electrochemical Results

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Du, K.; Lin, R.Z.; Yin, L.; Ho, J.S.; Wang, J.; Lim, C.T. Electronic textiles for energy, sensing, and communication. IScience 2022, 25, 104174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, S.L.; Karahan, H.E.; Wei, L.; Qian, Q.H.; Harris, A.T.; Minett, A.I.; Ramakrishna, S.; Ng, A.K.; Chen, Y. Textile energy storage: Structural design concepts, material selection and future perspectives. Energy Storage Mater. 2016, 3, 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Peng, M.K.; Chen, J.R.; Tang, X.N.; Li, L.B.; Hu, T.; Yuan, K.; Chen, Y.W. High Energy and Power Zinc Ion Capacitors: A Dual-Ion Adsorption and Reversible Chemical Adsorption Coupling Mechanism. ACS Nano 2022, 16, 2877–2888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukatskaya, M.R.; Dunn, B.; Gogotsi, Y. Multidimensional materials and device architectures for future hybrid energy storage. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tie, D.; Huang, S.F.; Wang, J.; Ma, J.M.; Zhang, J.J.; Zhao, Y.F. Hybrid energy storage devices: Advanced electrode materials and matching principles. Energy Storage Mater. 2019, 21, 22–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.W.; Hu, M.X.; Huang, Z.H.; Kang, F.Y.; Lv, R.T. Sodium-ion capacitors with superior energy-power performance by using carbon-based materials in both electrodes. Prog. Nat. Sci.-Mater. 2020, 30, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.Z.; Yao, W.J.; Song, X.H.; Zhang, G.; Chen, B.J.; Yang, J.H.; Tang, Y.B. A Calcium-Ion Hybrid Energy Storage Device with High Capacity and Long Cycling Life under Room Temperature. Adv. Energy Mater. 2019, 9, 1803865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.X.; Liu, Z.C.; Yuan, X.H.; Mo, J.; Li, C.Y.; Fu, L.J.; Zhu, Y.S.; Wu, X.W.; Wu, Y.P. A quasi-solid-state Li-ion capacitor with high energy density based on LiVO/carbon nanofibers and electrochemically-exfoliated graphene sheets. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 14922–14929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.I.; Kim, B.; Baek, J.; Kim, J.H.; Yoo, J. Hybrid Aluminum-Ion Capacitor with High Energy Density and Long-Term Durability. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2022, 169, 120521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, S.; Wei, W.L.; Beeby, S.P. Full Screen-Printed Zinc-Ion Supercapacitor on Textile for Wearable Electronics. In Proceedings of the 2023 22nd International Conference on Micro and Nanotechnology for Power Generation and Energy Conversion Applications (PowerMEMS), Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 11–14 December 2023; pp. 266–269. [Google Scholar]

- Chojnacka, A.; Beguin, F. Recent progress in the realization of metal-ion capacitors with alloying anodic hosts: A mini review. Electrochem. Commun. 2022, 139, 107305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanwinckel, H.; Mathis, J.S.; Waelkens, C. Evidence from Zinc Abundances for Dust Fractionation in Chemically Peculiar Stars. Nature 1992, 356, 500–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumur, F.; Beouch, L.; Tehfe, M.A.; Contal, E.; Lepeltier, M.; Wantz, G.; Graff, B.; Goubard, F.; Mayer, C.R.; Lalevée, J.; et al. Low-cost zinc complexes for white organic light-emitting devices. Thin Solid Films 2014, 564, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.N.; Yuan, L.B.; Zhu, Y.L.; Bai, X.W.; Ye, C.; Jiao, Y.; Qiao, S.Z. Low-cost and Non-flammable Eutectic Electrolytes for Advanced Zn-I Batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 2023, 62, e202310284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.X.; Ma, R.J.; Wang, X.L. Ultrafast, long-life, high-loading, and wide-temperature zinc ion supercapacitors. Energy Storage Mater. 2022, 46, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.W.; Han, T.L.; Lin, X.R.; Zhu, Y.J.; Ding, Y.Y.; Liu, J.Y.; Zhang, H.G. An integrated flexible self-healing Zn-ion battery using dendrite-suppressible hydrogel electrolyte and free-standing electrodes for wearable electronics. Nano Res. 2023, 16, 11000–11011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Khan, M.; Sheikh, T.M.M.; Mumtaz, M.Z.; Chohan, T.A.; Shamim, S.; Liu, Y.H. Zinc essentiality, toxicity, and its bacterial bioremediation: A comprehensive insight. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 900740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.J.; Chodankar, N.R.; Hwang, S.K.; Raju, G.S.R.; Ranjith, K.S.; Huh, Y.S.; Han, Y.K. Ultra-stable flexible Zn-ion capacitor with pseudocapacitive 2D layered niobium oxyphosphides. Energy Storage Mater. 2022, 45, 1040–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.D.; Zhang, H.; Gao, Y.; Liu, J.H.; Cao, X.H.; Zhan, C.C.; Wang, S.T.; Wang, J.Z.; Dou, S.X.; Cao, D.P. Zinc-ion hybrid supercapacitors: Design strategies, challenges, and perspectives. Carbon Neutralizat. 2022, 1, 159–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Bissett, M.A.; Dryfe, R.A.W. Investigation of Voltage Range and Self-Discharge in Aqueous Zinc-Ion Hybrid Supercapacitors. ChemSusChem 2021, 14, 1700–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.M.; Wang, Y.; Kulaots, I.; Zhu, H.L.; Sheldon, B.W. Water-in-Salt Battery Electrolyte for High-Voltage Supercapacitors: A Fundamental Study on Biomass and Carbon Fiber Electrodes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2024, 171, 110526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.F.; Wang, P.; Dong, X.Y.; Jiang, H.M.; Cui, M.; Meng, C.G. Flexible quasi-solid-state zinc-ion hybrid supercapacitor based on carbon cloths displays ultrahigh areal capacitance. Fund Res. 2023, 3, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.W.; Hao, H.L.; Liang, J.Y.; Zhao, B.W.; Guo, Z.F.; Liu, G.Z.; Li, W.Y. High energy density flexible Zn-ion hybrid supercapacitors with conductive cotton fabric constructed by rGO/CNT/PPy nanocomposite. Nanotechnology 2024, 35, 015404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.H.; Khanam, Z.; Ahmed, S.; Wang, T.; Wang, H.T.; Song, S.H. Flexible Antifreeze Zn-Ion Hybrid Supercapacitor Based on Gel Electrolyte with Graphene Electrodes. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 2021, 13, 16454–16468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Fan, L.S.; Shuai, Y.; Zhang, N.Q. Ultrathin and super-tough membrane for anti-dendrite separator in aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2022, 3, 100824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeboonruan, N.; Lohitkarn, J.; Poochai, C.; Tuantranont, A.; Limthongkul, P.; Sriprachuabwong, C. Dendrite-free anodes enabled by MOF-808 and ZIF-8 modified glass microfiber separator for ultralong-life zinc-ion hybrid capacitors. J. Energy Storage 2024, 85, 111063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dmitrenko, M.; Kuzminova, A.; Zolotarev, A.; Selyutin, A.; Ermakov, S.; Penkova, A. Nanofiltration Mixed Matrix Membranes from Cellulose Modified with Zn-Based Metal-Organic Frameworks for the Enhanced Water Treatment from Heavy Metal Ions. Polymers 2023, 15, 1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.D.; Wan, C.; Xu, M.W.; Huang, J.; Chen, K.; Xu, Q.Q.; Li, S.Z.; Zhang, F.Z.; Guo, Y.L.; You, Y.; et al. An extremely safe and flexible zinc-ion hybrid supercapacitor based on a scalable, thin and high-performance hierarchical structured gel electrolyte. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 470, 144339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plonka, R.; Mäder, E.; Gao, S.L.; Bellmann, C.; Dutschk, V.; Zhandarov, S. Adhesion of epoxy/glass fibre composites influenced by aging effects on sizings. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2004, 35, 1207–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Lin, X.H.; Yang, B.; Gao, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Li, L.; Zhang, H.; Li, L.; Zheng, Z.; Wang, J.Z.; et al. Cellulose Separators for Rechargeable Batteries with High Safety: Advantages, Strategies, and Perspectives. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2409368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, S.; Hillier, N.; Beeby, S.P. Phase-Inverted Copolymer Membrane for the Enhancement of Textile Supercapacitors. Polymers 2022, 14, 3399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Ma, X.T.; Shi, J.L.; Yao, Z.K.; Zhu, B.K.; Zhu, L.P. Preparation and properties of poly(ethylene oxide) gel filled polypropylene separators and their corresponding gel polymer electrolytes for Li-ion batteries. Electrochim. Acta 2011, 56, 2641–2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.R.; Li, L.B.; Yang, X.Y.; You, J.; Xu, Y.P.; Wang, H.; Ma, Y.; Gao, G.X. Influence of additives in a PVDF-based solid polymer electrolyte on conductivity and Li-ion battery performance. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2018, 2, 492–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Yi, Z.H.; Li, H.L.; Lv, W.S.; Hu, N.; Zhang, X.Y.; Chen, W.J.; Wei, Z.W.; Shen, F.; He, H.B. Separator Design Strategies to Advance Rechargeable Aqueous Zinc Ion Batteries. Chem. Eur. J. 2024, 30, e202303461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, D.M.; Teng, G.H.; Heng, Y.Q.; Chen, Z.Z.; Hu, D.Y. Eco-friendly and thermally stable cellulose film prepared by phase inversion as supercapacitor separator. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2020, 249, 122979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuraray. Kuraray Activated Carbon Powder YP-80F, High Power Grade. Available online: https://www.cam-energy.com/shop/ku-yp-80-kuraray-activated-carbon-powder-yp-80f-high-power-grade-1801 (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Merck. GF51714772 Zinc. Available online: https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/GB/en/product/aldrich/gf51714772 (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Li, Z.; Huo, J.; Zhao, W.; Fan, L.; Zheng, M.; Guo, S. Waste cotton fabrics-derived oxygen-rich porous carbon cathode for high-performance zinc-ion capacitors. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 49, 113969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.L.; Koripally, N.; Shin, C.; Mu, A.; Chen, Z.; Wang, K.P.; Ng, T.N. Engineering electro-crystallization orientation and surface activation in wide-temperature zinc ion supercapacitors. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.R.; Afroj, S.; Tan, S.; Eichhorn, S.J.; Novoselov, K.S.; Karim, N. Inkjet-Printed Metal-Organic Frameworks for Smart E-Textile Supercapacitors. EcoMat 2025, 7, e70020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.R.; Afroj, S.; Karim, N. Scalable Production of 2D Material Heterostructure Textiles for High-Performance Wearable Supercapacitors. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 18481–18493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Device Type | Textile Electrode Type | Electrolyte Type |

|---|---|---|

| A | ZHSC | OPE |

| B | ZHSC | AE |

| C | CC | OPE |

| D | CC | AE |

| Ref | Cathode/Anode | Electrolyte | Capacitance (mF cm−2) | Energy Density (µWh cm−2) | Power Density (mW cm−2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| This work | Activated carbon/zinc coating on PC 217 | OPE | 159.2 | 52.3 | 0.27 |

| [38] | Carbonised cotton/zinc metal | 2 M Aqueous zinc sulfate | 588.8 | 206.4 | 0.126 |

| [39] | Activated carbon on carbon cloth/zinc metal | 12 M Aqueous zinc sulfate | 525.4 | 241.9 | 1.76 |

| [22] | Activated carbon on carbon cloth/zinc metal | Aqueous zinc sulfate | 2437 | 1354 | 1 |

| [31] | Activated carbon coating on PC 217 | 1M TEABF4 in DMSO | 38.2 | 27.9 | 0.32 |

| [40] | Cobalt–zinc metal-organic framework textile | Aqueous sulfuric acid | 354 | 196 | 54.4 |

| [41] | Graphene molybdenum disulfide-coated textile | Aqueous sulfuric acid | 1054 | 58.4 | 1.604 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yong, S.; Arumugam, S.; Beeby, S.P. Improved Polymer Membrane for Textile Zinc-Ion Capacitor. Polymers 2025, 17, 2995. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17222995

Yong S, Arumugam S, Beeby SP. Improved Polymer Membrane for Textile Zinc-Ion Capacitor. Polymers. 2025; 17(22):2995. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17222995

Chicago/Turabian StyleYong, Sheng, Sasikumar Arumugam, and Stephen Paul Beeby. 2025. "Improved Polymer Membrane for Textile Zinc-Ion Capacitor" Polymers 17, no. 22: 2995. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17222995

APA StyleYong, S., Arumugam, S., & Beeby, S. P. (2025). Improved Polymer Membrane for Textile Zinc-Ion Capacitor. Polymers, 17(22), 2995. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17222995