Towards Fire-Safe Polymer Electrolytes for Lithium-Ion Batteries: Strategies for Electrolyte Design and Structural Design

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Thermal Runaway in Lithium-Ion Cells: Mechanisms and Implications for Polymer Electrolytes

3. Safety Assessment of Polymer Electrolytes

3.1. Flammability Tests

3.1.1. Self-Extinguishing Time (SET)

3.1.2. Limiting Oxygen Index

3.1.3. Cone Calorimetry

3.1.4. Thermogravimetric Analysis

3.2. Battery Abuse Testing

3.2.1. Electrical Abuse Tests

3.2.2. Thermal Abuse Tests

3.2.3. Mechanical Abuse Tests

4. Safety by Design: Strategies for Fire-Safe Polymer Electrolytes

4.1. Inorganic Fillers

4.1.1. Mineral Fillers

4.1.2. Ceramic Families as In Situ Flame Skeletons

Garnet Fillers

NASICON

4.1.3. MXenes

4.2. Crystalline Porous Frameworks (MOFs and COFs)

4.2.1. Metal–Organic Frameworks (MOFs)

4.2.2. Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs)

4.3. Phosphorus-Based Additives

4.3.1. Cyclophosphazenes

4.3.2. Organophosphates

4.3.3. Metal Phosphinates

4.4. Halogen-Based Additives for Flame Suppression in Solid Polymer Electrolytes

4.4.1. Fluorine (F) Additives

4.4.2. Bromine (Br) Additives

4.5. Silicon-Based Additives

4.5.1. Inorganic Silicon Additives

4.5.2. Silicon-Containing Polymers

4.5.3. Polyhedral Oligomeric Silsesquioxanes (POSSs)

4.5.4. Synergistic Si–P Systems

4.6. Bio-Based Additives

4.7. Ionic Liquids

4.7.1. IL-Confined Composites

4.7.2. Poly(Ionic Liquid)

4.8. Matrix-Engineered Fire-Safe Polymer Electrolytes

4.8.1. Sandwich Polymer Electrolytes

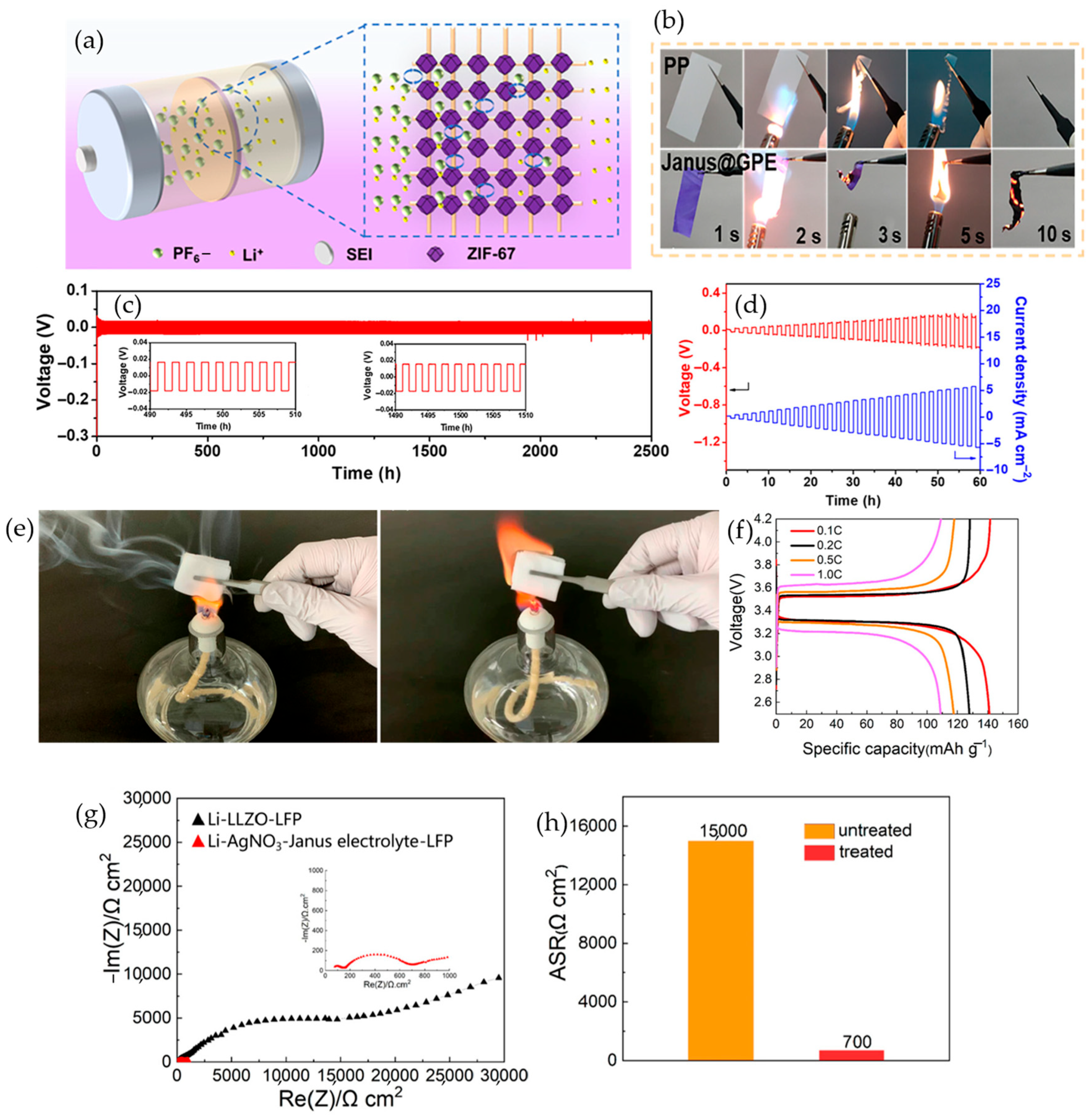

4.8.2. Janus/Gradient Gel Polymer Electrolytes

5. Conclusions and Outlook

5.1. Summary of Mechanistic Design Principles and Architectures

5.2. From Blueprint to Practice: Cost, Scalability, Sustainability, and Next-Generation Compatibility

5.3. Green Outlook and Research Priorities

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gao, J.; Xuan, X.; Tang, Y.; Xie, Y.; Bi, Z.; Zou, J.; Li, L.; Yang, C. Thermal Stability of MXene: Current Status and Future Perspectives. Small 2025, 21, e05881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Xie, Y.; Tang, Y.; Wang, T.; Wang, Z.; Yang, C. Unraveling the Role of Metal Vacancy Sites and Doped Nitrogen in Enhancing Pseudocapacitance Performance of Defective MXene. Small 2024, 20, 2307408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Tang, Y.; Tian, Y.; Luo, Y.; Faraz Ud Din, M.; Yin, X.; Que, W. Flexible Nitrogen-Doped 2D Titanium Carbides (MXene) Films Constructed by an Ex Situ Solvothermal Method with Extraordinary Volumetric Capacitance. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8, 1802087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Chen, G.; Tang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, J.; Bi, Z.; Xuan, X.; Zou, J.; Zhang, A.; Yang, C. Unraveling the Ionic Storage Mechanism of Flexible Nitrogen-Doped MXene Films for High-Performance Aqueous Hybrid Supercapacitors. Small 2024, 20, 2405817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, X.; Xie, Y.; Tang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Bi, Z.; Zou, J.; Lei, Y.; Gao, J.; Li, L.; Zhang, A.; et al. Revealing the Ionic Storage Mechanisms of Mo2VC2Tz (MXene) in Multiple Aqueous Electrolytes for High-Performance Supercapacitors. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 519, 165537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Chang, N.; Tang, Y.; Xie, Y.; Xuan, X.; Bi, Z.; Zou, J.; Li, L.; Liu, M.; Yang, C. Uncovering the Strengthening Mechanisms of Metal Vacancies in the Structure and Capacitance Performance of Defect-Controlled Mo2−□CTz MXene. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 519, 165391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. Global EV Outlook 2025—Analysis. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2025 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Goodenough, J.B.; Park, K.S. The Li-Ion Rechargeable Battery: A Perspective. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 1167–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armand, M.; Tarascon, J.M. Building Better Batteries. Nature 2008, 451, 652–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, X.; Ouyang, M.; Liu, X.; Lu, L.; Xia, Y.; He, X. Thermal Runaway Mechanism of Lithium Ion Battery for Electric Vehicles: A Review. Energy Storage Mater. 2018, 10, 246–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, F.; Andersson, P.; Blomqvist, P.; Lorén, A.; Mellander, B.E. Characteristics of Lithium-Ion Batteries during Fire Tests. J. Power Sources 2014, 271, 414–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Hase, W.; Ozaki, Y.; Konno, Y.; Inatsuki, M.; Nishimura, K.; Hashimoto, N.; Fujita, O. Experimental Study on Flammability Limits of Electrolyte Solvents in Lithium-Ion Batteries Using a Wick Combustion Method. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 2019, 109, 109858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Department of Transportation. DOT Bans All Samsung Galaxy Note7 Phones from Airplanes. Available online: https://www.transportation.gov/briefing-room/dot-bans-all-samsung-galaxy-note7-phones-airplanes (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- City of New York. FDNY Commissioner Announces Significant Progress in the Battle Against Lithium-Ion Battery Fires. Available online: https://www.nyc.gov/site/fdny/news/03-25/fdny-commissioner-robert-s-tucker-significant-progress-the-battle-against-lithium-ion#/0 (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Finegan, D.P.; Billman, J.; Darst, J.; Hughes, P.; Trillo, J.; Sharp, M.; Benson, A.; Pham, M.; Kesuma, I.; Buckwell, M.; et al. The Battery Failure Databank: Insights from an Open-Access Database of Thermal Runaway Behaviors of Li-Ion Cells and a Resource for Benchmarking Risks. J. Power Sources 2024, 597, 234106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Chen, F.; Martinez-Ibañez, M.; Feng, W.; Forsyth, M.; Zhou, Z.; Armand, M.; Zhang, H. A Reflection on Polymer Electrolytes for Solid-State Lithium Metal Batteries. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, P.; Yu, H.; Ding, Z.; Liu, Y.; Lu, J.; Lavorgna, M.; Wu, J.; Liu, X. Review on Polymer-Based Composite Electrolytes for Lithium Batteries. Front. Chem. 2019, 7, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, J.; Pathak, T.S.; Santos, D.M.F. Applications of Polymer Electrolytes in Lithium-Ion Batteries: A Review. Polymers 2023, 15, 3907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Wang, L.; Chen, Z.; Kan, Y.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, H.; He, X. Incombustible Polymer Electrolyte Boosting Safety of Solid-State Lithium Batteries: A Review. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2300892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Han, S.; Liu, S.; Zhao, J.; Xie, W. Fire-Safe Polymer Electrolyte Strategies for Lithium Batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 2024, 66, 103174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Mao, B.; Stoliarov, S.I.; Sun, J. A Review of Lithium Ion Battery Failure Mechanisms and Fire Prevention Strategies. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2019, 73, 95–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Liu, Y.; Lin, D.; Pei, A.; Cui, Y. Materials for Lithium-Ion Battery Safety. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaas9820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumai, K.; Miyashiro, H.; Kobayashi, Y.; Takei, K.; Ishikawa, R. Gas Generation Mechanism Due to Electrolyte Decomposition in Commercial Lithium-Ion Cell. J. Power Sources 1999, 81–82, 715–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lux, S.F.; Lucas, I.T.; Pollak, E.; Passerini, S.; Winter, M.; Kostecki, R. The Mechanism of HF Formation in LiPF6 Based Organic Carbonate Electrolytes. Electrochem. Commun. 2012, 14, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spotte-Smith, E.W.C.; Petrocelli, T.B.; Patel, H.D.; Blau, S.M.; Persson, K.A. Elementary Decomposition Mechanisms of Lithium Hexafluorophosphate in Battery Electrolytes and Interphases. ACS Energy Lett. 2022, 8, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orendorff, C.J. The Role of Separators in Lithium-Ion Cell Safety. Electrochem. Soc. Interface 2012, 21, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Pu, H.; Wei, Y. Polypropylene/Polyethylene Multilayer Separators with Enhanced Thermal Stability for Lithium-Ion Battery via Multilayer Coextrusion. Electrochim. Acta 2018, 264, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golubkov, A.W.; Fuchs, D.; Wagner, J.; Wiltsche, H.; Stangl, C.; Fauler, G.; Voitic, G.; Thaler, A.; Hacker, V. Thermal-Runaway Experiments on Consumer Li-Ion Batteries with Metal-Oxide and Olivin-Type Cathodes. RSC Adv. 2013, 4, 3633–3642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi-Asl, S.; Lu, J.; Amine, K.; Shahbazian-Yassar, R. Oxygen Release Degradation in Li-Ion Battery Cathode Materials: Mechanisms and Mitigating Approaches. Adv. Energy Mater. 2019, 9, 1900551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Feng, X.; Wang, L.; Liu, X.; Ohma, A.; Lu, L.; Ren, D.; Huang, W.; Li, Y.; Yi, M.; et al. Unlocking the Self-Supported Thermal Runaway of High-Energy Lithium-Ion Batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 2021, 39, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugryniec, P.J.; Resendiz, E.G.; Nwophoke, S.M.; Khanna, S.; James, C.; Brown, S.F. Review of Gas Emissions from Lithium-Ion Battery Thermal Runaway Failure—Considering Toxic and Flammable Compounds. J. Energy Storage 2024, 87, 111288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Rao, Z.; Yang, X.; Wang, C.; Sun, X.; Li, X. Safety Concerns in Solid-State Lithium Batteries: From Materials to Devices. Energy Environ. Sci. 2024, 17, 7543–7565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charbonnel, J.; Dubourg, S.; Testard, E.; Broche, L.; Magnier, C.; Rochard, T.; Marteau, D.; Thivel, P.X.; Vincent, R. Preliminary Study of All-Solid-State Batteries: Evaluation of Blast Formation during the Thermal Runaway. iScience 2023, 26, 108078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.; Yang, C.; Xie, K.; Xin, S.; Xiong, Z.; Li, K.; Guo, Y.G.; You, Y. Benchmarking the Safety Performance of Organic Electrolytes for Rechargeable Lithium Batteries: A Thermochemical Perspective. ACS Energy Lett. 2023, 8, 836–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Duan, Q.; Zhao, C.; Huang, Z.; Wang, Q. Experimental Investigation on the Thermal Runaway and Its Propagation in the Large Format Battery Module with Li(Ni1/3Co1/3Mn1/3)O2 as Cathode. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 375, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigłowska, M.; Kurc, B.; Galiński, M.; Fuć, P.; Kamińska, M.; Szymlet, N.; Daszkiewicz, P. Challenges for Safe Electrolytes Applied in Lithium-Ion Cells—A Review. Materials 2021, 14, 6783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, S.; Wohlfahrt-Mehrens, M.; Wachtler, M. Flammability of Li-Ion Battery Electrolytes: Flash Point and Self-Extinguishing Time Measurements. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2015, 162, A3084–A3097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combustion (Fire) Tests for Plastics. Available online: https://www.ul.com/services/combustion-fire-tests-plastics (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Xu, K.; Ding, M.S.; Zhang, S.; Allen, J.L.; Jow, T.R. An Attempt to Formulate Nonflammable Lithium Ion Electrolytes with Alkyl Phosphates and Phosphazenes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2002, 149, A622–A626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D2863; Standard Test Method for Measuring the Minimum Oxygen Concentration to Support Candle–Like Combustion of Plastics (Oxygen Index). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023.

- Kim, Y.; Lee, S.; Yoon, H. Fire-Safe Polymer Composites: Flame-Retardant Effect of Nanofillers. Polymers 2021, 13, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parcheta-Szwindowska, P.; Habaj, J.; Krzemińska, I.; Datta, J. A Comprehensive Review of Reactive Flame Retardants for Polyurethane Materials: Current Development and Future Opportunities in an Environmentally Friendly Direction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, K.; Rendén, G.; Mensah, R.A.; Kim, N.K.; Jiang, L.; Xu, Q.; Restás, Á.; Neisiany, R.E.; Hedenqvist, M.S.; Försth, M.; et al. A Review on the Flammability Properties of Carbon-Based Polymeric Composites: State-of-the-Art and Future Trends. Polymers 2020, 12, 1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Tanchak, R.N.; Wang, Q. A Review on Cone Calorimeter for Assessment of Flame-Retarded Polymer Composites. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2022, 147, 10209–10234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Li, X.; Han, P.; Li, Y.; Liu, C.; Chen, Q.; Li, Q. Research on the Fire Behaviors of Polymeric Separator Materials PI, PPESK, and PVDF. Fire 2023, 6, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyazovkin, S.; Chrissafis, K.; Di Lorenzo, M.L.; Koga, N.; Pijolat, M.; Roduit, B.; Sbirrazzuoli, N.; Suñol, J.J. ICTAC Kinetics Committee Recommendations for Collecting Experimental Thermal Analysis Data for Kinetic Computations. Thermochim. Acta 2014, 590, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyazovkin, S.; Burnham, A.K.; Criado, J.M.; Pérez-Maqueda, L.A.; Popescu, C.; Sbirrazzuoli, N. ICTAC Kinetics Committee Recommendations for Performing Kinetic Computations on Thermal Analysis Data. Thermochim. Acta 2011, 520, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadatkhah, N.; Carillo Garcia, A.; Ackermann, S.; Leclerc, P.; Latifi, M.; Samih, S.; Patience, G.S.; Chaouki, J. Experimental Methods in Chemical Engineering: Thermogravimetric Analysis—TGA. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2020, 98, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalinde, I.; Berrueta, A.; Arza, J.; Sanchis, P.; Ursúa, A. On the Characterization of Lithium-Ion Batteries under Overtemperature and Overcharge Conditions: Identification of Abuse Areas and Experimental Validation. Appl. Energy 2024, 354, 122205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spotnitz, R.; Franklin, J. Abuse Behavior of High-Power, Lithium-Ion Cells. J. Power Sources 2003, 113, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, S.; Zhu, J.; Gao, Y. A Critical Review of Thermal Runaway Prediction and Early-Warning Methods for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Energy Mater. Adv. 2023, 4, 0008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, D.; Chen, M.; Weng, J.; Wang, K.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z. Exploring the Thermal Stability of Lithium-Ion Cells via Accelerating Rate Calorimetry: A Review. J. Energy Chem. 2023, 81, 543–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, J.; Orendorff, C.J. Evaluation of Mechanical Abuse Techniques in Lithium Ion Batteries. J. Power Sources 2014, 247, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoshima, T.; Mukoyama, D.; Maeda, F.; Osaka, T.; Takazawa, K.; Egusa, S.; Naoi, S.; Ishikura, S.; Yamamoto, K. Direct Observation of Internal State of Thermal Runaway in Lithium Ion Battery during Nail-Penetration Test. J. Power Sources 2018, 393, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabow, J.; Klink, J.; Orazov, N.; Benger, R.; Hauer, I.; Beck, H.P. Triggering and Characterisation of Realistic Internal Short Circuits in Lithium-Ion Pouch Cells—A New Approach Using Precise Needle Penetration. Batteries 2023, 9, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Han, T.; Jeong, J.; Lee, H.; Ryou, M.H.; Lee, Y.M. A Flame-Retardant Composite Polymer Electrolyte for Lithium-Ion Polymer Batteries. Electrochim. Acta 2017, 241, 553–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Woo, M.H.; Omkar, S.; Javid, A.; Chang, D.R.; Park, C.J. Advanced PVDF-HFP-Based Composite Quasi-Solid Polymer Electrolyte for High-Energy Lithium-Ion Batteries with Enhanced Safety and Durability. J. Power Sources 2025, 640, 236716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, W.K.; Cho, J.; Kannan, A.G.; Lee, Y.S.; Kim, D.W. Cross-Linked Composite Gel Polymer Electrolyte Using Mesoporous Methacrylate-Functionalized SiO2 Nanoparticles for Lithium-Ion Polymer Batteries. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 26332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamitha, C.; Janakiraman, S.; Ghosh, S.; Venimadhav, A.; Prabhu, K.N.; Anandhan, S. Synthesis and Evaluation of a New Gel Polymer Electrolyte for High-Performance Li-Ion Batteries from Electrospun Nanocomposite of PVDF/Ca–Al-Layered Double Hydroxide. J. Mater. Res. 2022, 37, 3942–3954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, H.; Park, D.U.; Lee, Y.J.; Moon, J.; Lee, S.; Choi, T.M.; Lee, T.; Lee, G.; Oh, J.M.; Shin, W.H.; et al. The Structural Effect of a Composite Solid Electrolyte on Electrochemical Performance and Fire Safety. Materials 2025, 18, 1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Huang, K.; Zhao, J.; Tian, S.; Dou, H.; Zhang, X. Dual-Filler Reinforced PVDF-HFP Based Polymer Electrolyte Enabling High-Safety Design of Lithium Metal Batteries. Nano Res. 2024, 17, 5251–5260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Su, J.; Jin, J.; Sun, C.; Ruan, Y.; Chen, C.; Wen, Z. In Situ Generated Fireproof Gel Polymer Electrolyte with Li6.4Ga0.2La3Zr2O12 As Initiator and Ion-Conductive Filler. Adv. Energy Mater. 2019, 9, 1900611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Gai, Q.; Deng, X.; Ma, J.; Gao, H. A New Type of LATP Doped PVDF-HFP Based Electrolyte Membrane with Flame Retardancy and Long Cycle Stability for Solid State Batteries. J. Energy Storage 2023, 73, 108576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Wei, Z. Flame-Retardant Gel Electrolytes Reinforced by PVDF-HFP/Ceramic Nanofiber Mat for Lithium Metal Batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 22841–22849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Q.; Zheng, Y.; Kota, S.; Huang, W.; Wang, S.; Qi, H.; Kim, S.; Tu, Y.; Barsoum, M.W.; Li, C.Y. 2D MXene-Containing Polymer Electrolytes for All-Solid-State Lithium Metal Batteries. Nanoscale Adv. 2019, 1, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.F.; Xiong, Y.; Wu, L.; Xiong, X.; Me, T.; Wang, X. A Solid-State Lithium Battery with PVDF-HFP-Modified Fireproof Ionogel Polymer Electrolyte. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2023, 6, 4016–4026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Ning, M.; Sun, M.; Li, B.; Liang, Y.; Li, Z. Research Progress of Functional MXene in Inhibiting Lithium/Zinc Metal Battery Dendrites. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 26837–26856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, R.; Anne, M.; Das, S.; Chavva, T.; Shelke, M.V.; Pol, V.G. Glory of Fire Retardants in Li-Ion Batteries: Could They Be Intrinsically Safer? Adv. Sustain. Syst. 2024, 8, 2400273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Xiang, Y.; Yao, W.; Yan, F.; Zhang, Y.; Gerlach, D.; Pei, Y.; Rudolf, P.; Portale, G. MXene Surface Engineering Enabling High-Performance Solid-State Lithium Metal Batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2416040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gropp, C.; Canossa, S.; Wuttke, S.; Gándara, F.; Li, Q.; Gagliardi, L.; Yaghi, O.M. Standard Practices of Reticular Chemistry. ACS Cent. Sci. 2020, 6, 1255–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaghi, O.M. Reticular Chemistry in All Dimensions. ACS Cent. Sci. 2019, 5, 1295–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Xu, X.; Luo, X.; Ji, S.; Zhao, J.; Liu, J.; Huo, Y. Recent Progress in Flame-Retardant Polymer Electrolytes for Solid-State Lithium Metal Batteries. Batteries 2023, 9, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Meng, X.; Hu, X.; Tang, A.; Ruan, Z.; Kang, Q.; Yan, L.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, N.; Liu, B.; et al. Defective Cerium-Based Metal-Organic Framework Nanorod-Reinforcing Polymer Electrolytes for Lithium Metal Batteries. J. Power Sources 2025, 628, 235914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.C.; Yusuf, A.; Li, S.W.; Qi, X.L.; Ma, Y.; Wang, D.Y. Metal Organic Frameworks Enabled Rational Design of Multifunctional PEO-Based Solid Polymer Electrolytes. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 414, 128702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Zhu, M.; Tang, C.; Quan, K.; Tong, Q.; Cao, H.; Jiang, J.; Yang, H.; Zhang, J. ZIF-8@MXene-Reinforced Flame-Retardant and Highly Conductive Polymer Composite Electrolyte for Dendrite-Free Lithium Metal Batteries. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 620, 478–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Pan, H.; Yin, G.; Xiang, Y.; Lin, X.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Hui, Q.; Zhang, X.; Xu, M. Achieving Multifunctional MOF/Polymer-Based Quasi-Solid Electrolytes via Functional Molecule Encapsulation in MOFs. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2025, 12, 4438–4448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Wu, J.; Chen, J.; Wang, X.; Yang, Z. 3D Flame-Retardant Skeleton Reinforced Polymer Electrolyte for Solid-State Dendrite-Free Lithium Metal Batteries. J. Energy Chem. 2022, 71, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Yan, D.; Liu, J.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Q.; Cheng, P.; Zaworotko, M.J.; Zhang, Z. Thermally Rearranged Covalent Organic Framework with Flame-Retardancy as a High Safety Li-Ion Solid Electrolyte. eScience 2022, 2, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, D.; Liang, W.; Wang, X.; Yue, L.; Wang, B.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, Y.; Li, Y. Lewis-Basic Nitrogen-Rich Covalent Organic Frameworks Enable Flexible and Stretchable Solid-State Electrolytes with Stable Lithium-Metal Batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 2024, 72, 103709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, A.; Iqbal, R.; Majeed, M.K.; Hussain, A.; Akbar, A.R.; Hussain, Z.; Jabar, B.; Rauf, S.; Shaw, L.L. Boosting Lithium-Ion Conductivity of Polymer Electrolyte by Selective Introduction of Covalent Organic Frameworks for Safe Lithium Metal Batteries. Nano Energy 2024, 128, 109848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hao, Q.; Lv, Q.; Shang, X.; Wu, M.; Li, Z. The Research Progress on COF Solid-State Electrolytes for Lithium Batteries. Chem. Commun. 2024, 60, 10046–10063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christy, M.; Ul, Z.; Awan, H.; Polczyk, T.; Nagai, A. Covalent Organic Framework-Based Electrolytes for Lithium Solid-State Batteries—Recent Progress. Batteries 2023, 9, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharte, B. Phosphorus-Based Flame Retardancy Mechanisms—Old Hat or a Starting Point for Future Development? Materials 2010, 3, 4710–4745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabe, S.; Chuenban, Y.; Schartel, B. Exploring the Modes of Action of Phosphorus-Based Flame Retardants in Polymeric Systems. Materials 2017, 10, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korobeinichev, O.; Shmakov, A.; Paletsky, A.; Trubachev, S.; Shaklein, A.; Karpov, A.; Sosnin, E.; Kostritsa, S.; Kumar, A.; Shvartsberg, V. Mechanisms of the Action of Fire-Retardants on Reducing the Flammability of Certain Classes of Polymers and Glass-Reinforced Plastics Based on the Study of Their Combustion. Polymers 2022, 14, 4523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Yang, M.; Zuo, C.; Chen, G.; He, D.; Zhou, X.; Liu, C.; Xie, X.; Xue, Z. Flexible, Self-Healing, and Fire-Resistant Polymer Electrolytes Fabricated via Photopolymerization for All-Solid-State Lithium Metal Batteries. ACS Macro Lett. 2020, 9, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, C.; Yang, M.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, K.; Li, S.; Luo, W.; He, D.; Liu, C.; Xie, X.; Xue, Z. Cyclophosphazene-Based Hybrid Polymer Electrolytes Obtained via Epoxy–Amine Reaction for High-Performance All-Solid-State Lithium-Ion Batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 18871–18879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Li, C.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, S.; Liu, J.; Wang, M.; Wang, L. Building Flame-Retardant Polymer Electrolytes via Microcapsule Technology for Stable Lithium Batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 27470–27480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, C.J.; Yang, T.C.; Chen, X.H.; Zhou, J.F.; Lee, C.C.; Teng, H.; Jan, J.S. In-Situ Formed, Nonflammable and Electrochemical Stable Gel Polymer Electrolytes Based on a Phosphazene Derivative for Improving Safety in Lithium-Ion Batteries. J. Power Sources 2025, 656, 238099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmedo-Martínez, J.L.; Meabe, L.; Riva, R.; Guzmán-González, G.; Porcarelli, L.; Forsyth, M.; Mugica, A.; Calafel, I.; Müller, A.J.; Lecomte, P.; et al. Flame Retardant Polyphosphoester Copolymers as Solid Polymer Electrolyte for Lithium Batteries. Polym. Chem. 2021, 12, 3441–3450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, P.; Xie, S.; Sun, Q.; Chen, X.; He, Y. Flame-Retardant Solid Polymer Electrolyte Based on Phosphorus-Containing Polyurethane Acrylate/Succinonitrile for Lithium-Ion Batteries. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2022, 5, 7199–7209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, C.; Gao, S.; Cai, S.; Wang, Q.; Liu, J.; Liu, Z. A Novel Polyphosphonate Flame-Retardant Additive towards Safety-Reinforced All-Solid-State Polymer Electrolyte. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2020, 239, 122014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Liao, C.; Mu, X.; Wu, N.; Xu, Z.; Wang, J.; Song, L.; Kan, Y.; Hu, Y. Flame-Retardant ADP/PEO Solid Polymer Electrolyte for Dendrite-Free and Long-Life Lithium Battery by Generating Al, P-Rich SEI Layer. Nano Lett. 2021, 21, 4447–4453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Liu, J.; Zhang, S.; Wang, M.; Lv, Q.; Li, C.; Wang, L. Nonflammable Solid-State Polymer Electrolyte for High-Safety and Ultra-Stable Lithium-Ion Batteries. Batter. Supercaps 2024, 7, e202400069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmeia, K.A.; Fage, J.; Liang, S.; Gaan, S. An Overview of Mode of Action and Analytical Methods for Evaluation of Gas Phase Activities of Flame Retardants. Polymers 2015, 7, 504–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 31485; Electric vehicles −Safety requirements and test methods for traction battery. Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2015.

- Yang, B.; Pan, Y.; Li, T.; Hu, A.; Li, K.; Li, B.; Yang, L.; Long, J. High-Safety Lithium Metal Pouch Cells for Extreme Abuse Conditions by Implementing Flame-Retardant Perfluorinated Gel Polymer Electrolytes. Energy Storage Mater. 2024, 65, 103124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Lai, C.; Chen, K.; Wu, Q.; Gu, Y.; Wu, C.; Li, C. Dual Fluorination of Polymer Electrolyte and Conversion-Type Cathode for High-Capacity All-Solid-State Lithium Metal Batteries. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 7914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Li, R.J.; Chen, P.; Fu, Y.; Ma, X.Y.; Shen, T.; Zhou, B.; Chen, K.; Fu, J.J.; Bao, X.; et al. Highly Stretchable, Non-Flammable and Notch-Insensitive Intrinsic Self-Healing Solid-State Polymer Electrolyte for Stable and Safe Flexible Lithium Batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9, 4758–4769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhong, J.; Guo, Y.; Han, Q.; Liu, H.; Du, J.; Tian, J.; Tang, S.; Cao, Y. Fluorinated Nonflammable In Situ Gel Polymer Electrolyte for High-Voltage Lithium Metal Batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 39265–39275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Wan, J.; Ye, Y.; Liu, K.; Chou, L.Y.; Cui, Y. A Fireproof, Lightweight, Polymer-Polymer Solid-State Electrolyte for Safe Lithium Batteries. Nano Lett. 2020, 20, 1686–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.Y.; Yan, S.S.; Li, J.; Dong, H.; Zhou, P.; Wan, L.; Chen, X.X.; Zhang, W.L.; Xia, Y.C.; Wang, P.C.; et al. Lithium Bromide-Induced Organic-Rich Cathode/Electrolyte Interphase for High-Voltage and Flame-Retardant All-Solid-State Lithium Batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 24469–24479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Pei, F.; Cheng, D.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, H.; Huang, K.; Yuan, L.; Li, Z.; Xu, H.; Huang, Y. Flame-Retardant Polyurethane-Based Solid-State Polymer Electrolytes Enabled by Covalent Bonding for Lithium Metal Batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2310084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongsuk, P.; Pumchusak, J. Effect of Ultrasonication on the Morphology, Mechanical Property, Ionic Conductivity, and Flame Retardancy of PEO-LiCF3SO3-Halloysite Nanotube Composites for Use as Solid Polymer Electrolyte. Polymers 2022, 14, 3710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Li, F.; Li, D.; Cheng, D.; Wang, Z.; Liu, X.; Wang, H.; Zeng, X.; Huang, Y.; Xu, H. Negatively Charged Laponite Sheets Enhanced Solid Polymer Electrolytes for Long-Cycling Lithium-Metal Batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 4044–4052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Li, W.; Guo, C.; Song, Y.; Zhou, M.; Shi, Y.; Xu, J.; Li, L.; Shi, B.; Ouyang, Q.; et al. Two-Dimensional Silica Enhanced Solid Polymer Electrolyte for Lithium Metal Batteries. Particuology 2024, 85, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yang, T.; Zhang, W.; Huang, H.; Gan, Y.; Xia, Y.; He, X.; Zhang, J. Hydrogen Bonding Enhanced SiO2/PEO Composite Electrolytes for Solid-State Lithium Batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 2022, 10, 3400–3408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ling, C.; Long, K.; Liu, X.; Xiao, P.; Yu, Y.Z.; Wei, W.; Ji, X.; Tang, W.; Kuang, G.C.; et al. A Siloxane-Based Self-Healing Gel Electrolyte with Deep Eutectic Solvents for Safe Quasi-Solid-State Lithium Metal Batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 488, 150888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalybekkyzy, S.; Kopzhassar, A.F.; Kahraman, M.V.; Mentbayeva, A.; Bakenov, Z. Fabrication of UV-Crosslinked Flexible Solid Polymer Electrolyte with PDMS for Li-Ion Batteries. Polymers 2020, 13, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liang, L.; Hu, W.; Liao, H.; Zhang, Y. POSS Hybrid Poly(Ionic Liquid) Ionogel Solid Electrolyte for Flexible Lithium Batteries. J. Power Sources 2022, 542, 231766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Jia, L.; Liu, X.; Zhang, C. A Novel Silicon/Phosphorus Co-Flame Retardant Polymer Electrolyte for High-Safety All-Solid-State Lithium Ion Batteries. Polymers 2020, 12, 2937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Ran, H.; Fu, Y.; Huang, W.; Tian, Q.; Yan, W. Fabrication of Aluminum Phosphate–Coated Silica: Effect on Mechanical Properties, Flame Retardancy, and Ionic Conductivity of PEO Composite Electrolytes. J. Polym. Res. 2025, 32, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Gomes, M.B.; Yusuf, A.; Yin, G.Z.; Sun, C.C.; Wang, D.Y. Flame-Retardant Reinforced Halloysite Nanotubes as Multi-Functional Fillers for PEO-Based Polymer Electrolytes. Eur. Polym. J. 2024, 215, 113246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varan, N.; Merghes, P.; Plesu, N.; Macarie, L.; Ilia, G.; Simulescu, V. Phosphorus-Containing Polymer Electrolytes for Li Batteries. Batteries 2024, 10, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Wang, J.; Zhong, L.; Qi, G.; Liu, F.; Pan, Y.; Yang, F.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; Li, L.; et al. Recent Advances on Cellulose-Based Solid Polymer Electrolytes. Ind. Chem. Mater. 2025, 3, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Tan, J.; Liu, Z.; Bao, C.; Li, A.; Liu, Q.; Li, B. Incombustible Solid Polymer Electrolytes: A Critical Review and Perspective. J. Energy Chem. 2024, 93, 264–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, D.; Yuan, H.; Zhang, H.; Tan, Y. A Flame Retarded Polymer-Based Composite Solid Electrolyte Improved by Natural Polysaccharides. Compos. Commun. 2021, 26, 100774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fang, T.; Wang, S.; Wang, C.; Li, D.; Xia, Y. Alginate Fiber-Grafted Polyetheramine-Driven High Ion-Conductive and Flame-Retardant Separator and Solid Polymer Electrolyte for Lithium Metal Batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 56780–56789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Ghosh, A.; Tang, W.; Yin, G.Z.; Fernández-Blázquez, J.P.; Zhang, M.; Wang, D.Y. Alpha-Cyclodextrin-Based Polyrotaxane Combining Phytate Lithium Salt as a Novel Bio-Based Flame-Retardant Solid Polymer Electrolyte for All-Solid-State Lithium Metal Batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 512, 162376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xu, H.; Ming, H.; Zhao, P.; Shang, S.; Liu, S. High-Performance Alginate-Poly(Ethylene Oxide)-Based Solid Polymer Electrolyte. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 14073–14084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziam, H.; Ouarga, A.; Ettalibi, O.; Shanmukaraj, D.; Noukrati, H.; Sehaqui, H.; Saadoune, I.; Barroug, A.; Youcef, H.B. Phosphorylated Cellulose Nanofiber as Sustainable Organic Filler and Potential Flame-Retardant for All-Solid-State Lithium Batteries. J. Energy Storage 2023, 62, 106838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Yu, J.; Hu, Y.; Texter, J.; Yan, F. Ionic Liquid/Poly(Ionic Liquid)-Based Electrolytes for Lithium Batteries. Ind. Chem. Mater. 2023, 1, 39–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, N.; Bharti, N.; Singh, S. Recent Advances in Non-Flammable Electrolytes for Safer Lithium-Ion Batteries. Batteries 2019, 5, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, P.L.; Tsao, C.H.; Hsu, C.H.; Chen, S.T.; Hsu, H.M. A New Strategy for Preparing Oligomeric Ionic Liquid Gel Polymer Electrolytes for High-Performance and Nonflammable Lithium Ion Batteries. J. Membr. Sci. 2016, 499, 462–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Han, Y.; Wang, H.; Xiong, S.; Sun, W.; Zheng, C.; Xie, K. Flame Retardant and Stable Li1.5Al0.5Ge1.5(PO4)3-Supported Ionic Liquid Gel Polymer Electrolytes for High Safety Rechargeable Solid-State Lithium Metal Batteries. J. Phys. Chem. C 2018, 122, 10334–10342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, H.T.H.; Umair, M.; Yang, J.; Luo, J.; Yu, S.; Wei, J. PVDF-HFP-Modified Ionic Liquid-Based Gel Polymer Electrolytes for Enhanced Conductivity and Long-Term Interfacial Stability in Lithium-Ion Batteries. Appl. Mater. Today 2025, 46, 102910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, F.; Tang, H.; Li, J.; Jiao, S.; Qiu, J.; Peng, J.; Chen, X.; et al. In-Situ Radiation-Synthesized UiO-66/Poly(Ionic Liquid) Gel Electrolyte with High Conductivity, Wide Electrochemical Window and Flame Retardancy for High Performance Lithium Metal Batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 2025, 82, 104551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Chen, E.; Wang, D.; Qin, W.; Fang, S.; Xu, T.; Liu, J.; Tang, M.; Wang, Z. A Fiber-Reinforced Poly(Ionic Liquid) Solid Electrolyte with Low Flammability and High Conductivity for High-Performance Lithium–Metal Batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 19682–19691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Chen, X.; Yuan, W.; Chen, H.; Liao, H.; Zhang, Y. Highly Conductive, Flexible, and Nonflammable Double-Network Poly(Ionic Liquid)-Based Ionogel Electrolyte for Flexible Lithium-Ion Batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 25410–25420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Chen, J.; Guo, Y.; Zhu, J.; Qu, X.; Niu, W.; Liu, X. Fire-Resistant, High-Performance Gel Polymer Electrolytes Derived from Poly(Ionic Liquid)/P(VDF-HFP) Composite Membranes for Lithium Ion Batteries. J. Membr. Sci. 2020, 599, 117827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, B.; Chen, S.; Chen, Y.; Liu, L. Self-Shutdown Function Induced by Sandwich-like Gel Polymer Electrolytes for High Safety Lithium Metal Batteries. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 14036–14046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Liao, C.; Liu, Y.; Yu, H.; Zhang, S.; Zhu, Y.; Li, Z.; Li, X.; Kan, Y.; Hu, Y. Non-Flammable Sandwich-Structured TPU Gel Polymer Electrolyte without Flame Retardant Addition for High Performance Lithium Ion Batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 2022, 52, 562–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Guo, J.; Bi, C.; Hao, Z.; Li, C.; Wang, Q.; Han, X. Sandwich-like Polyimide Nanofiber Membrane of PEO-Based Solid-State Electrolytes to Promote Mechanical Properties and Security for Lithium Metal Batteries. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2025, 109, 1266–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Xu, S.; Song, Z.; Jiang, W.; Zhang, S.; Jian, X.; Hu, F. Promoting Uniform Lithium Deposition with Janus Gel Polymer Electrolytes Enabling Stable Lithium Metal Batteries. InfoMat 2024, 6, e12551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Liu, G.; Wang, K.; Dong, W.; Han, J.; Yu, Y.; Min, Z.; Yang, C.; Lu, Z. Electrochemically-Matched and Nonflammable Janus Solid Electrolyte for Lithium-Metal Batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 39271–39281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, H.; Deng, N.; Gao, L.; Cheng, B.; Kang, W. Janus Nanofibers with Multiple Li+ Transport Channels and Outstanding Thermal Stability for All-Solid-State Composite Polymer Electrolytes. J. Mater. Chem. A 2024, 12, 16022–16033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, C.D.; Slater, P.R.; Hare, S.D.; Simmons, M.J.H.; Kendrick, E. A Review of Metrology in Lithium-Ion Electrode Coating Processes. Mater. Des. 2021, 209, 109971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Nelson, P.A.; Gallagher, K.G.; Dees, D.W. Energy Impact of Cathode Drying and Solvent Recovery during Lithium-Ion Battery Manufacturing. J. Power Sources 2016, 322, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehm, R.; Kumberg, J.; Dörrer, C.; Müller, M.; Bauer, W.; Scharfer, P.; Schabel, W. In Situ Investigations of Simultaneous Two-Layer Slot Die Coating of Component-Graded Anodes for Improved High-Energy Li-Ion Batteries. Energy Technol. 2020, 8, 1901251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Deng, L.; Li, X.; Wu, T.; Zhang, W.; Cui, H.; Yang, H. Metal–Organic Frameworks for Solid-State Electrolytes: A Mini Review. Electrochem. Commun. 2023, 150, 107491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Liang, W.; Su, S.; Jiang, X.; Bando, Y.; Zhang, B.; Ma, Z.; Wang, X. Advances of Solid Polymer Electrolytes with High-Voltage Stability. Next Mater. 2025, 7, 100364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrero, G.A.; Åvall, G.; Janßen, K.; Son, Y.; Kravets, Y.; Sun, Y.; Adelhelm, P. Solvent Co-Intercalation Reactions for Batteries and Beyond. Chem. Rev. 2025, 125, 3401–3439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, J.; Oh, J.; Jeong, H.; Kang, W.; Jo, C. A Review of Functional Separators for Lithium Metal Battery Applications. Materials 2020, 13, 4625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Wang, H.; Yang, F.; Zou, R.; Hou, C.C.; Xu, Q. Recent Progress on Metal–Organic Framework-Based Separators for Lithium–Sulfur Batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 2025, 13, 6124–6151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, W.J.; Park, J.B.; Jung, H.G.; Sun, Y.K. Controversial Topics on Lithium Superoxide in Li–O2 Batteries. ACS Energy Lett. 2017, 2, 2756–2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| System | Advantages | Disadvantages | Trade-Offs | Design Levers | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mineral fillers |

|

|

|

| [56,57,58,59] |

| NASICON |

|

|

|

| [60,61,62,63,64] |

| MXene |

|

|

|

| [65,66,67,69] |

| System | Advantages | Disadvantages | Trade-Offs | Design Levers | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOF |

|

|

|

| [71,74,75,76,77] |

| System | Advantages | Disadvantages | Trade-Offs | Design Levers | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COF |

|

|

|

| [71,78,79,80,81,82] |

| System | Advantages | Disadvantages | Trade-Offs | Design Levers | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphorous-based additives |

|

|

|

| [83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94] |

| System | Advantages | Disadvantages | Trade-Offs | Design Levers | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorine-based additives |

|

|

|

| [97,98,99,100] |

| Bromine-based additives |

|

|

|

| [101,102,103] |

| System | Advantages | Disadvantages | Trade-Offs | Design Levers | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silicon-based additive |

|

|

|

| [104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113] |

| System | Advantages | Disadvantages | Trade-Offs | Design Levers | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bio-based |

|

|

|

| [114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121] |

| System | Advantages | Disadvantages | Trade-Offs | Design Levers | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Il-based |

|

|

|

| [122,123,124,125,126] |

| PIL-based |

|

|

|

| [122,127,128,129,130] |

| System | Advantages | Disadvantages | Trade-Off | Design Levers | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sandwich-structured |

|

|

|

| [131,132,133] |

| System | Advantages | Disadvantages | Trade-Off | Design Levers | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Janus-structured |

|

|

|

| [134,135,136] |

| System | Primary Mechanisms | Practical Loading | Targets | Processing Priorities | Effectiveness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphorus-based | Char formation, acid catalysis, PO radical quench, P-rich interphase | Low–moderate | Self-extinguished, stable cycling | Tether or crosslink, in situ delivery, moisture control, interface passivation |

|

| Fluorine-based | Gas-phase quench, intrinsically nonflammable gels, wider oxidative window | Low–moderate | High-voltage, abuse tolerance, flexible formats | In situ gelation, crosslink tuning, CEI control, EHS management |

|

| Bromine- based | Strong gas-phase quench, bromide-enabled CEI | Low | Maximum suppression under abuse | Tethering, limited dose, passivation, gas handling |

|

| Mineral fillers | Heat sink and barrier, crystallinity reduction, reinforcement | Moderate | Self-extinguish trend, dimensional stability | Surface functionalization, good dispersion |

|

| NASICON | Fast Li pathways, thermal stability, barrier | Moderate | Safety with transport retention, dendrite moderation | Surface treatment, porous hosts, dual fillers |

|

| MXene | Crystallinity control, interfacial stabilization, guided Li nucleation | Low | Plating uniformity with safety kept | Surface terminations, oxidation control, hybrids |

|

| MOF | Ordered pores, anion management, FR hosting | Low–moderate | Selective transport with FR gain | Nanoscale MOFs, encapsulation, grafting |

|

| COF | Ordered channels, N-rich sites, thermal stability | Low–moderate | Thermal safety with selectivity, channel alignment, wall functionalization | Gentle compatibilization, morphology control, dry handling |

|

| Silicon-based | Porous or H-bond surfaces, rigid Si barrier, Si–P synergy | Moderate | Safety and stiffness with RT transport | Surface coating, dispersion, network tuning |

|

| Bio-based | Polar sites, fibrillar or porous networks, inherent char | Moderate | Safer cycling, greener profile | Gentle compatibilization, morphology control, dry handling |

|

| IL-based | Nonflammable, wide window, high RT conductivity, good wetting | Optimized high IL | High-voltage, abuse tolerance | In situ gelation, scaffold support, CEI/SEI design |

|

| PIL-based | Immobilized anions, shape-stable, low flammability | Moderate PIL | Safety with higher Li+ selectivity | Crosslink tuning, double networks, fiber or ceramic reinforcement |

|

| Sandwich architecture | Reinforcing or nonflammable core, self-shutdown | Set by core | Abuse tolerance without large polarization | Low-resistance bonding, in situ locking |

|

| Janus architecture | Face-specific chemistry for anode and cathode | Modest per face | Interface control with bulk transport kept | Correct orientation, graded porosity, in situ adhesion |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Truong, K.L.; Bae, J. Towards Fire-Safe Polymer Electrolytes for Lithium-Ion Batteries: Strategies for Electrolyte Design and Structural Design. Polymers 2025, 17, 2828. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17212828

Truong KL, Bae J. Towards Fire-Safe Polymer Electrolytes for Lithium-Ion Batteries: Strategies for Electrolyte Design and Structural Design. Polymers. 2025; 17(21):2828. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17212828

Chicago/Turabian StyleTruong, Khang Le, and Joonho Bae. 2025. "Towards Fire-Safe Polymer Electrolytes for Lithium-Ion Batteries: Strategies for Electrolyte Design and Structural Design" Polymers 17, no. 21: 2828. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17212828

APA StyleTruong, K. L., & Bae, J. (2025). Towards Fire-Safe Polymer Electrolytes for Lithium-Ion Batteries: Strategies for Electrolyte Design and Structural Design. Polymers, 17(21), 2828. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17212828