Amphiphilic Diblock Copolymers of Poly(N-vinyl pyrrolidone) and Poly(vinyl esters) Bearing N-Alkyl Side Chains for the Encapsulation of Curcumin and Indomethacin

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis of Diblock Copolymers PNVP-b-PVBu, PNVP-b-PVDc and PNVP-b-PVSt

2.2. Dynamic and Static Light Scattering (DLS and SLS) Techniques

2.2.1. Preparation of Stock Solutions for the DLS and SLS Measurements

2.2.2. Instrumentation and Methods for the DLS and SLS Measurements

2.3. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) Measurements

2.4. Encapsulation of Curcumin and Indomethacin

2.4.1. Preparation of Stock Solutions for Drug Encapsulation

2.4.2. Drug Loading Capacity and Efficiency (%DLC and %DLE) Calculation

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Self-Assembly Behavior of the Amphiphilic Diblock Copolymers in Aqueous Solutions

3.1.1. DLS Results for the PNVP-b-PVBu Samples

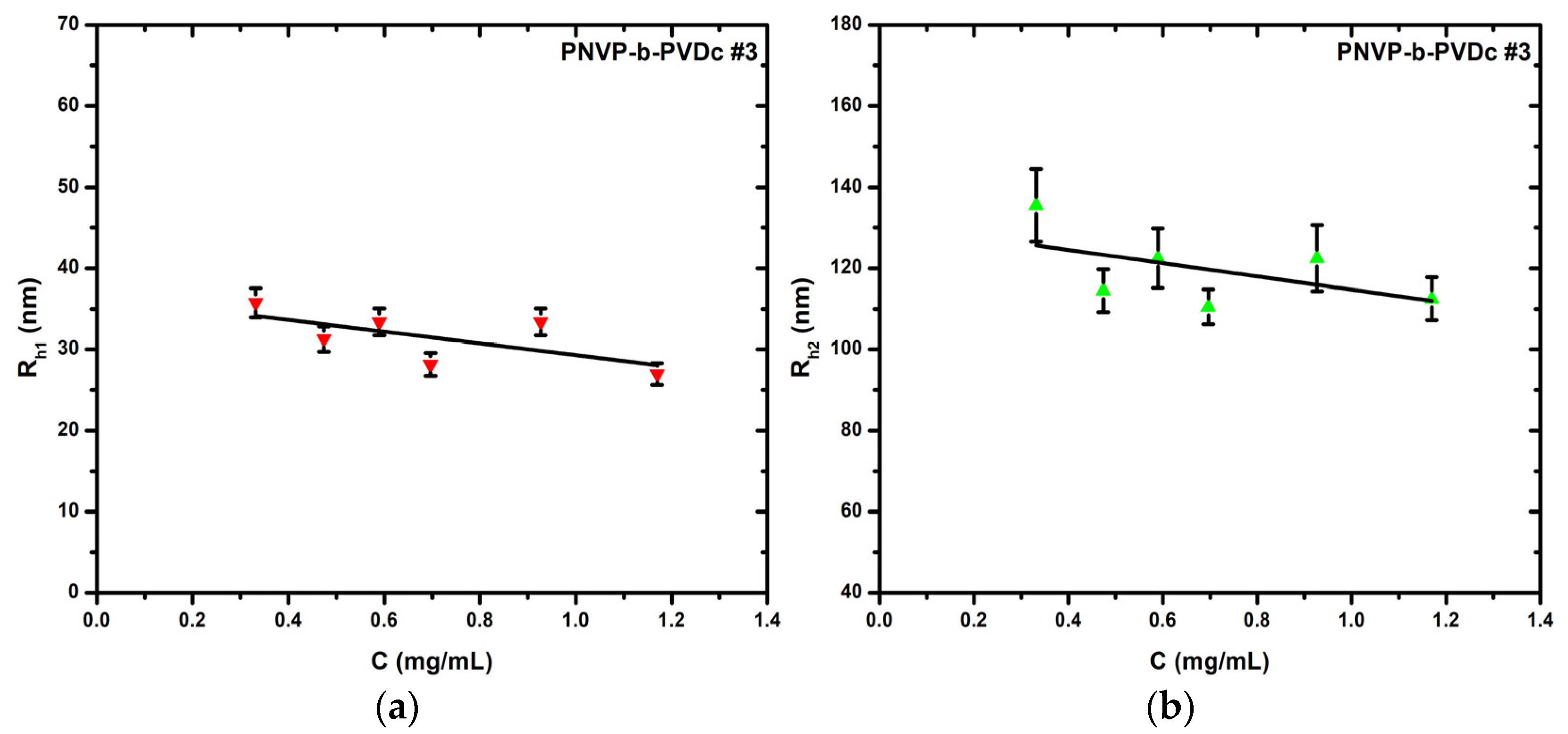

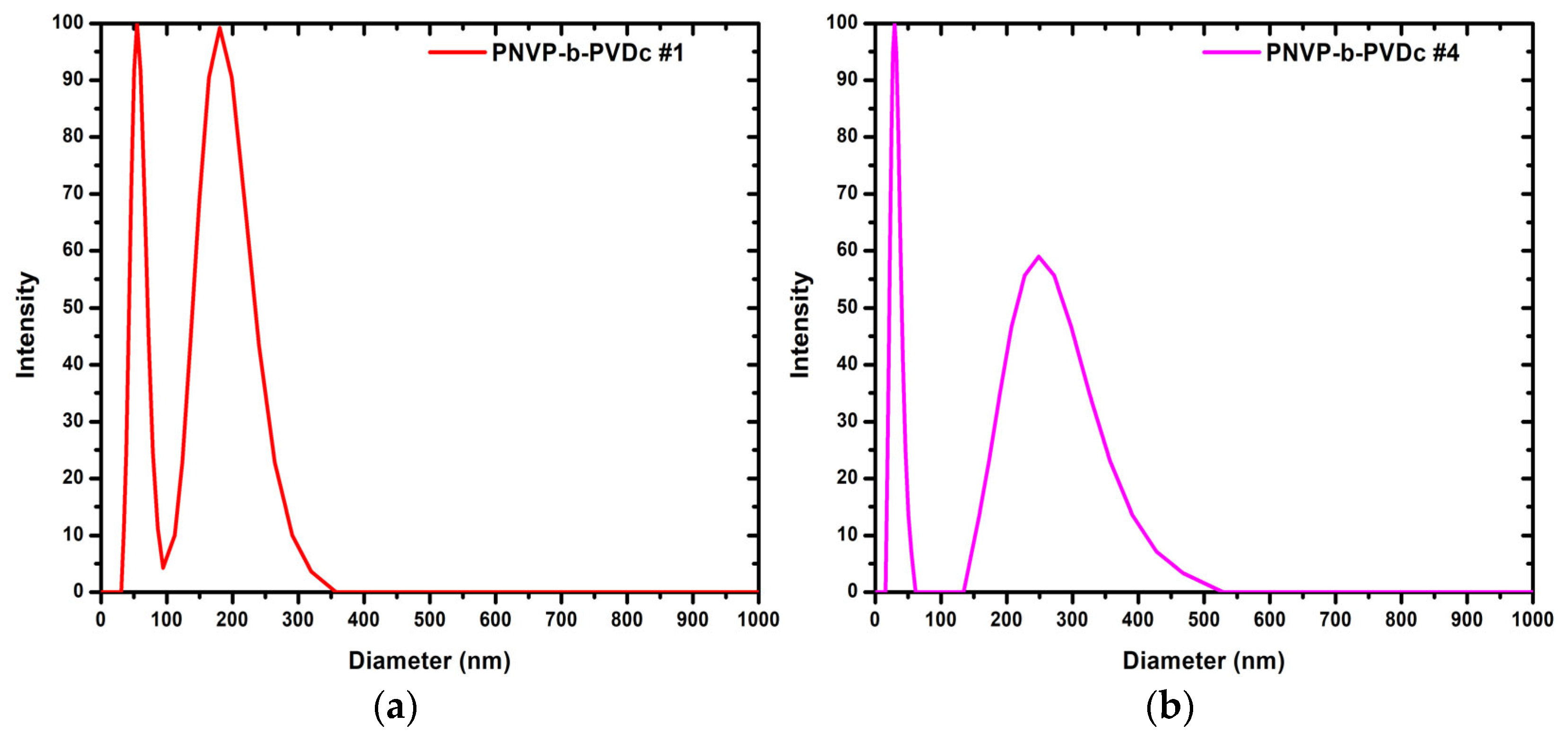

3.1.2. DLS Results for the PNVP-b-PVDc Samples

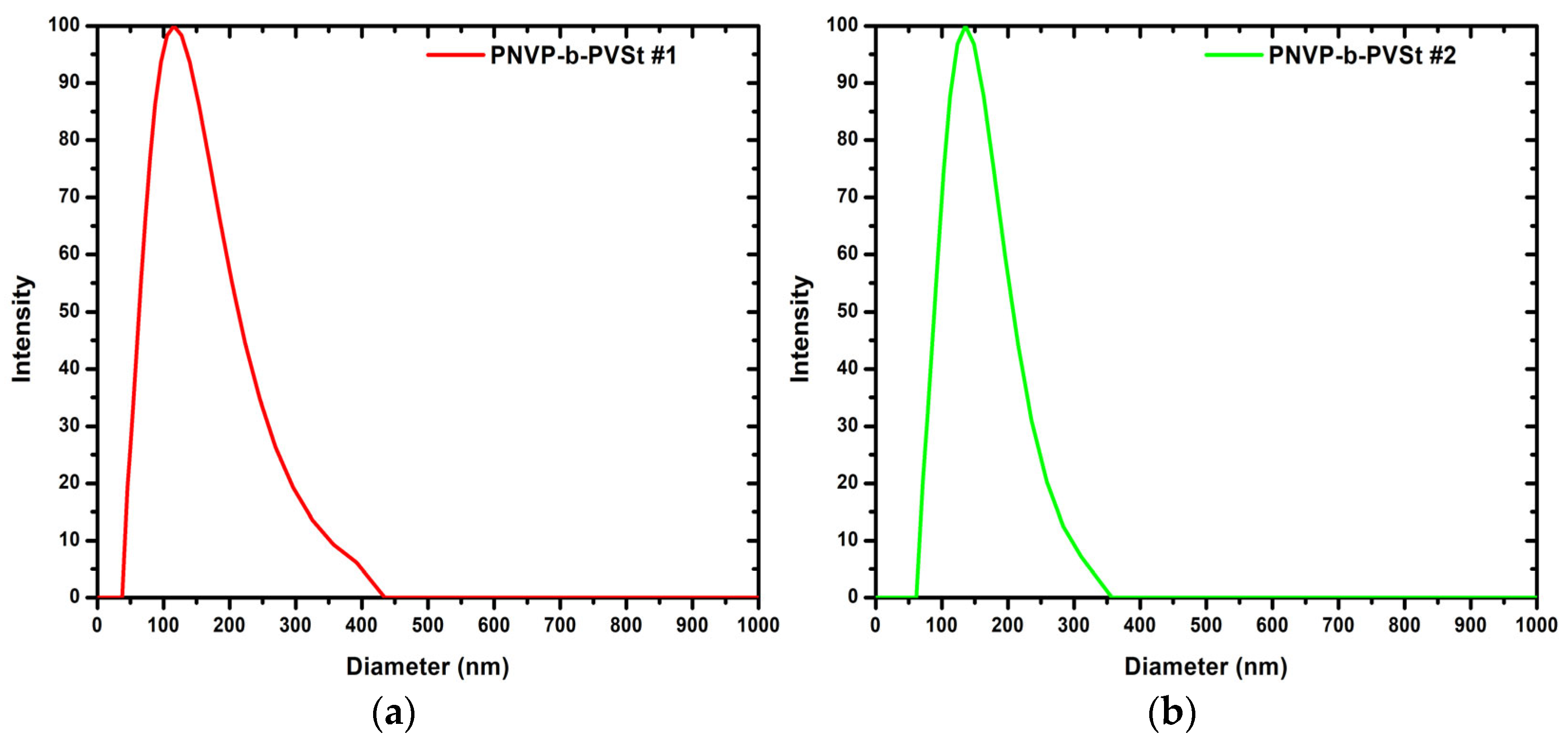

3.1.3. DLS and SLS Results for the PNVP-b-PVSt Samples

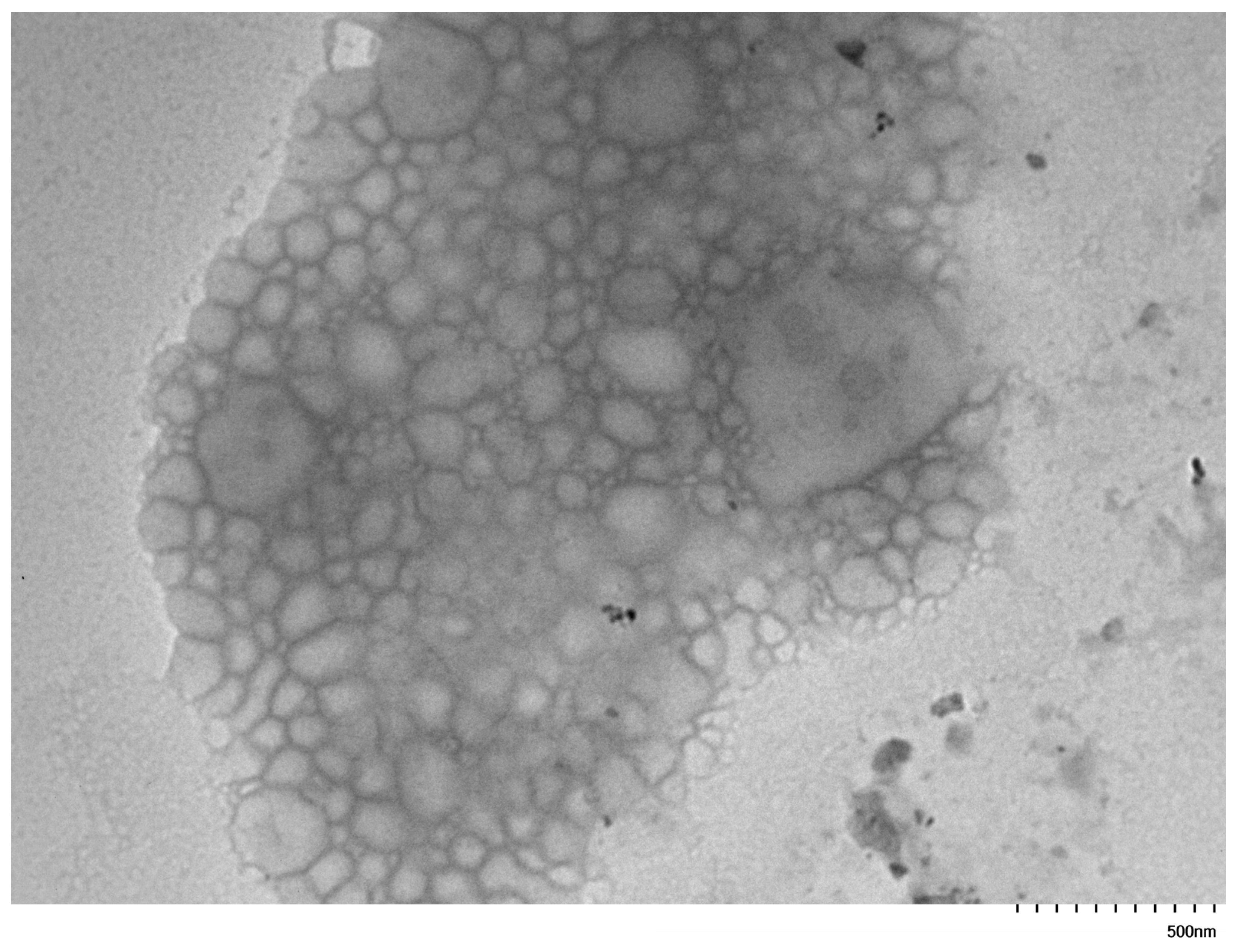

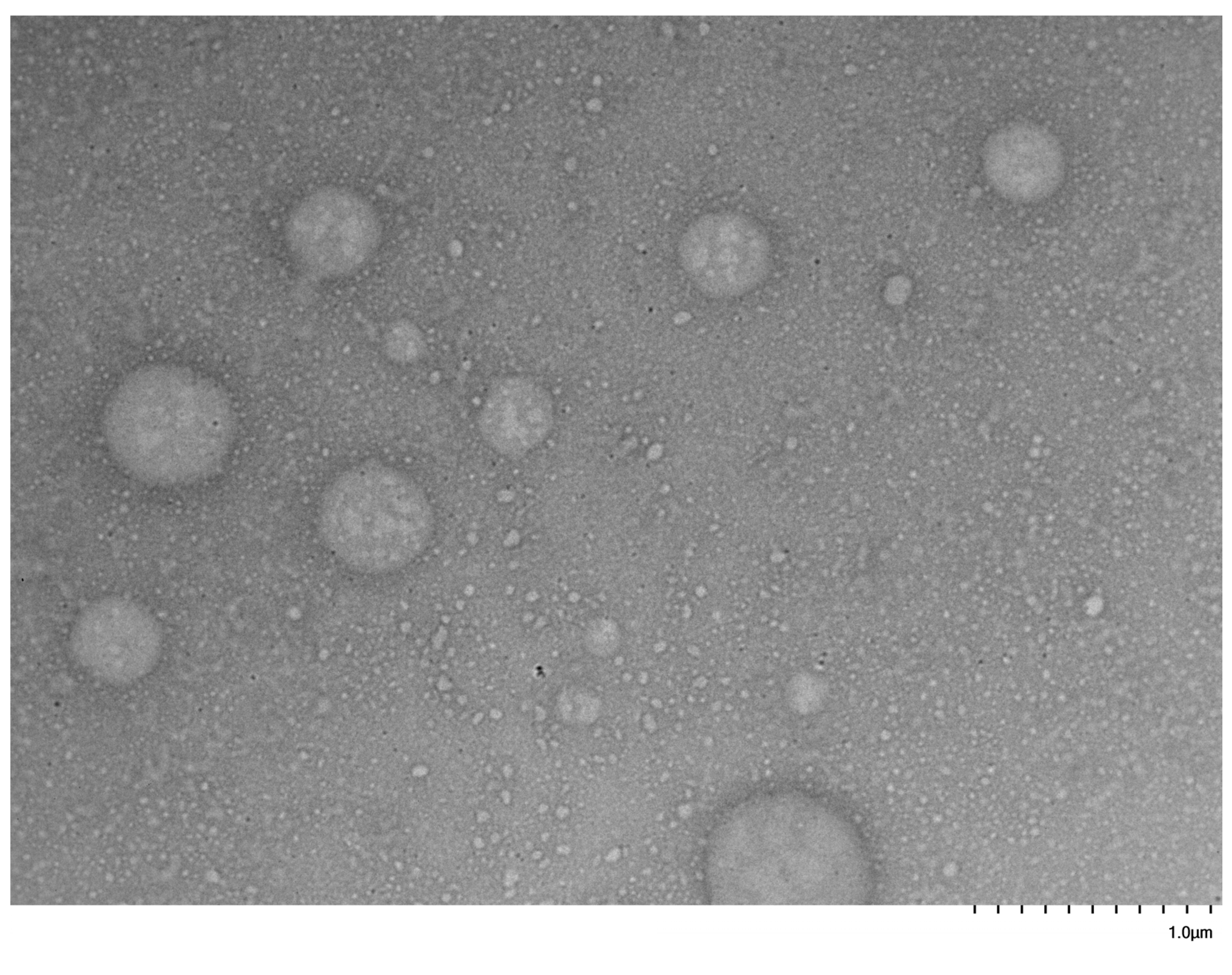

3.2. Self-Assembly Behaviour of the PNVP-b-PVEs Block Copolymers in Aqueous Solutions by TEM Imaging

3.3. Drug Encapsulation Results

3.3.1. Encapsulation of Curcumin

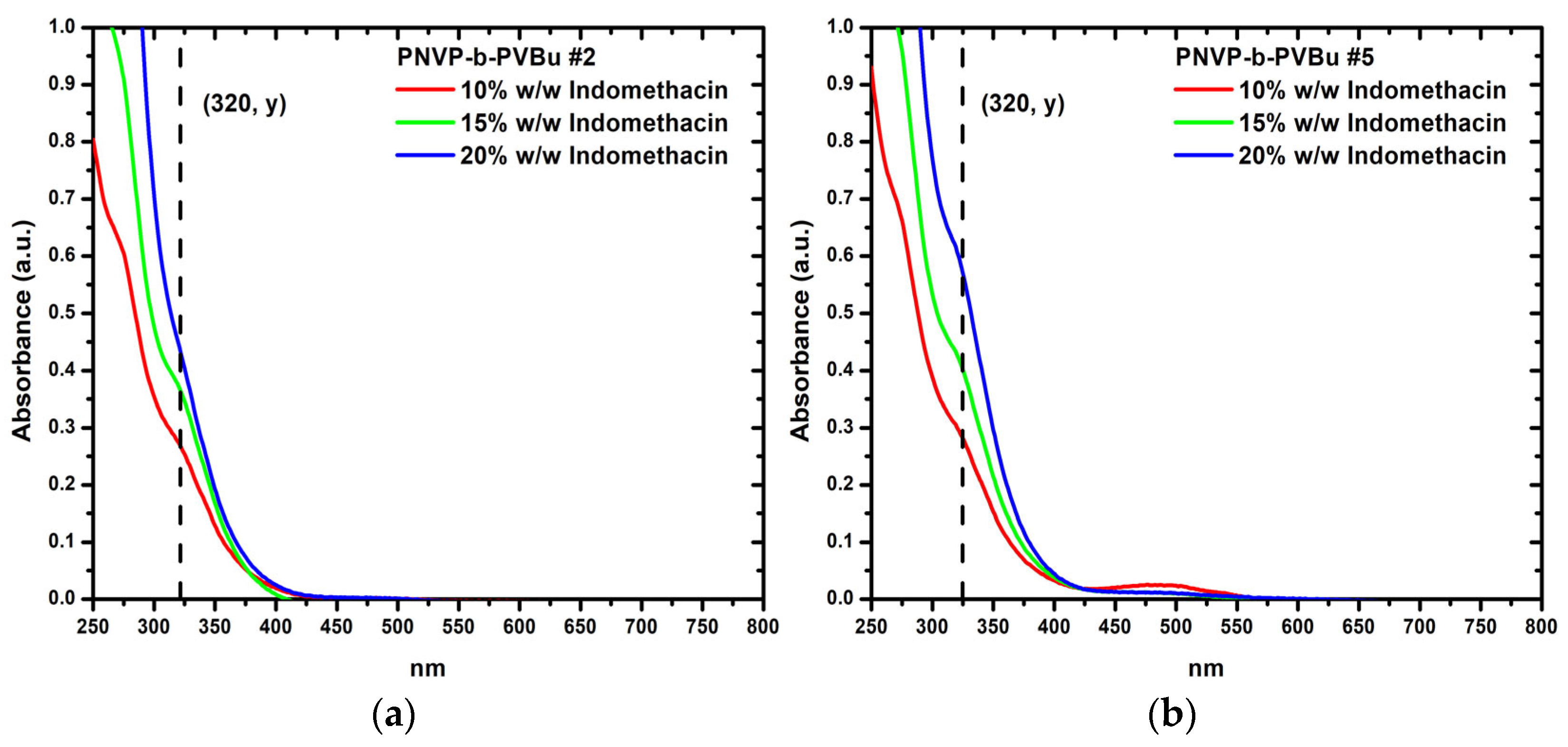

3.3.2. Encapsulation of Indomethacin

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xie, B.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Yang, P.; He, W. Solubilization techniques used for poorly water-soluble drugs. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2024, 14, 4683–4716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, H.D.; Trevaskis, N.L.; Charman, S.A.; Shanker, R.M.; Charman, W.N.; Pouton, C.W.; Porter, C.J.H. Strategies to Address Low Drug Solubility in Discovery and Development. Pharmacol. Rev. 2013, 65, 315–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawabata, Y.; Wada, K.; Nakatani, M.; Yamada, S.; Onoue, S. Formulation Design for Poorly Water-Soluble Drugs Based on Biopharmaceutics Classification System: Basic Approaches and Practical Applications. Int. J. Pharm. 2011, 420, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhalani, D.V.; Nutan, B.; Kumar, A.; Chandel, A.K.S. Bioavailability Enhancement Techniques for Poorly Aqueous Soluble Drugs and Therapeutics. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, B.J.; Bergström, C.A.S.; Vinarov, Z.; Kuentz, M.; Brouwers, J.; Augustijns, P.; Brandl, M.; Bernkop-Schnürch, A.; Shrestha, N.; Préat, V.; et al. Successful Oral Delivery of Poorly Water-Soluble Drugs Both Depends on the Intraluminal Behavior of Drugs and of Appropriate Advanced Drug Delivery Systems. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 137, 104967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stielow, M.; Witczyńska, A.; Kubryń, N.; Fijałkowski, Ł.; Nowaczyk, J.; Nowaczyk, A. The Bioavailability of Drugs—The Current State of Knowledge. Molecules 2023, 28, 8038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalepu, S.; Nekkanti, V. Insoluble Drug Delivery Strategies: Review of Recent Advances and Business Prospects. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2015, 5, 442–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, D.; Ramsey, J.D.; Kabanov, A.V. Polymeric Micelles for the Delivery of Poorly Soluble Drugs: From Nanoformulation to Clinical Approval. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2020, 156, 80–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuperkar, K.; Patel, D.; Atanase, L.I.; Bahadur, P. Amphiphilic Block Copolymers: Their Structures, and Self-Assembly to Polymeric Micelles and Polymersomes as Drug Delivery Vehicles. Polymers 2022, 14, 4702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negut, I.; Bita, B. Polymeric Micellar Systems—A Special Emphasis on “Smart” Drug Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral, H.; Miyata, K.; Osada, K.; Kataoka, K. Block Copolymer Micelles in Nanomedicine Applications. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 6844–6892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, R.S.; Zarei, S.; Haghighat, H.R.; Taromi, A.A.; Khonakdar, H.A. Recent Advances in Smart Polymeric Micelles for Targeted Drug Delivery. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2025, 36, e70180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chroni, A.; Chrysostomou, V.; Skandalis, A.; Pispas, S. Drug Delivery: Hydrophobic Drug Encapsulation into Amphiphilic Block Copolymer Micelles. In Supramolecules in Drug Discovery and Drug Delivery; Mavromoustakos, T., Tzakos, A.G., Durdagi, S., Eds.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana: New York, NY, USA, 2021; Volume 2207, pp. 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; McClements, D.J. Formulation of More Efficacious Curcumin Delivery Systems Using Colloid Science: Enhanced Solubility, Stability, and Bioavailability. Molecules 2020, 25, 2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacifici, G.M. Clinical Pharmacology of Indomethacin in Preterm Infants: Implications in Patent Ductus Arteriosus Closure. Pediatr. Drugs 2013, 15, 363–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunnumakkara, A.B.; Hegde, M.; Parama, D.; Girisa, S.; Kumar, A.; Daimary, U.D.; Garodia, P.; Yenisetti, S.C.; Oommen, O.V.; Aggarwal, B.B. Role of Turmeric and Curcumin in Prevention and Treatment of Chronic Diseases: Lessons Learned from Clinical Trials. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2023, 6, 447–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkis, N.; Sawan, A. Method Development for Simultaneously Determining Indomethacin and Nicotinamide in New Combination in Oral Dosage Formulations and Co-Amorphous Systems Using Three UV Spectrophotometric Techniques. Int. J. Anal. Chem. 2024, 2024, 2035824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roka, N.; Kokkorogianni, O.; Kontoes-Georgoudakis, P.; Choinopoulos, I.; Pitsikalis, M. Recent Advances in the Synthesis of Complex Macromolecular Architectures Based on Poly(N-vinyl pyrrolidone) and the RAFT Polymerization Technique. Polymers 2022, 14, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, M.; Toussaint, F.; Ben Djemaa, S.; Laloy, J.; Pendeville, H.; Evrard, B.; Jerôme, C.; Lechanteur, A.; Mottet, D.; Debuigne, A.; et al. Poly(vinyl pyrrolidone) derivatives as PEG alternatives for stealth, non-toxic and less immunogenic siRNA-containing lipoplex delivery. J. Control. Release 2023, 361, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Luo, X.; Xu, X.; Gao, N.; Liu, X. Preparation, characterization and in vivo pharmacokinetic study of PVP-modified oleanolic acid liposomes. Int. J. Pharm. 2017, 517, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinno, H. Poly(vinyl esters). In Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA: Weinheim, Germany, 2000; Volume 28, pp. 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, K.; Nakano, T.; Okamoto, Y. Synthesis of syndiotactic poly(vinyl alcohol) from fluorine-containing vinyl esters. Polym. J. 1998, 42, 9679–9686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riess, G. Micellization of block copolymers. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2003, 28, 1107–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, Y.; Eisenberg, A. Self-assembly of block copolymers. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 5969–5985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanazs, A.; Armes, S.P.; Ryan, A.J. Self-assembled block copolymer aggregates: From micelles to vesicles and their biological applications. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2009, 30, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perinelli, D.R.; Cespi, M.; Lorusso, N.; Palmieri, G.F.; Bonacucina, G.; Blasi, P. Surfactant Self-Assembling and Critical Micelle Concentration: One Approach Fits All? Langmuir 2020, 36, 5745–5753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Hu, D.; Liang, F.; Huang, X.; Zhu, Q. Influence Factors on the Critical Micelle Concentration Determination Using Pyrene as a Probe and a Simple Method of Preparing Samples. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2020, 7, 192092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeri, Ö.; Schönfeld, D.; Noirez, L.; Grillo, I.; Canetta, E.; Dejeu, J. Structural control in micelles of alkyl acrylate–acrylate copolymers via alkyl chain length and block length. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2020, 298, 829–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Gao, Q.; Ruan, Z. Effects of side-chain lengths on the structure and properties of anhydrides modified starch micelles: Experimental and DPD simulation studies. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 322, 122451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Discher, D.E.; Eisenberg, A. Polymer vesicles. Science 2002, 297, 967–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bates, F.S.; Fredrickson, G.H. Block copolymer thermodynamics: Theory and experiment. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 1990, 41, 525–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Si, J.; Zhu, J.; Nie, Y.; Lu, Y.; Chen, Y. Effect of block ratios on self-assembly morphologies of poly(ε-caprolactone)-block-poly(tert-butyl acrylate) block copolymer. Polymer 2023, 283, 126292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Zhang, E.; Yang, J.; Cao, Z. Strategies to Improve Micelle Stability for Drug Delivery. Nano Res. 2018, 11, 4985–4998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perumal, S.; Atchudan, R.; Lee, W. A Review of Polymeric Micelles and Their Applications. Polymers 2022, 14, 2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval, R.W.; Williams, D.E.; Kim, J.; Roth, C.B.; Torkelson, J.M. Critical micelle concentrations of block and gradient copolymers in homopolymer: Effects of sequence distribution, composition, and molecular weight. J. Polym. Sci. Part B Polym. Phys. 2008, 46, 2673–2687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roka, N.; Pitsikalis, M. Synthesis and Micellization Behavior of Amphiphilic Block Copolymers of Poly(N-Vinyl Pyrrolidone) and Poly(Benzyl Methacrylate): Block versus Statistical Copolymers. Polymers 2023, 15, 2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roka, N.; Pitsikalis, M. Synthesis, Characterization, and Self-Assembly Behavior of Block Copolymers of N-Vinyl Pyrrolidone with n-Alkyl Methacrylates. Polymers 2025, 17, 1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fokaidis-Psyllas, A.; Kokkorogianni, O.; Pitsikalis, M. Statistical Copolymers of N-Vinylpyrrolidone and Phenoxyethyl Methacrylate via RAFT Polymerization: Monomer Reactivity Ratios, Thermal Properties, Kinetics of Thermal Decomposition and Self-Assembly Behavior in Selective Solvents. Polym. Bull. 2025, 82, 9161–9179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roka, N.; Skiadas, V.-C.; Kolovou, A.; Papazoglou, T.-P.; Pitsikalis, M. Micellization Studies of Block Copolymers of Poly(N-Vinyl Pyrrolidone) and Poly(Vinyl Esters) Bearing N-Alkyl Side-Groups in Tetrahydrofuran. Polymers 2025, 17, 2842. [Google Scholar]

- Kontoes-Georgoudakis, P.; Plachouras, N.V.; Kokkorogianni, O.; Pitsikalis, M. Amphiphilic Block Copolymers of Poly(N-Vinyl Pyrrolidone) and Poly(Isobornyl Methacrylate): Synthesis, Characterization and Micellization Behaviour in Selective Solvents. Eur. Polym. J. 2024, 208, 112873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roka, N.; Papazoglou, T.-P.; Pitsikalis, M. Block Copolymers of Poly(N-Vinyl Pyrrolidone) and Poly(Vinyl Esters) Bearing n-alkyl Side Groups via Reversible Addition-Fragmentation Chain-Transfer Polymerization: Synthesis, Characterization, and Thermal Properties. Polymers 2024, 16, 2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provencher, S.W. CONTIN: A general purpose constrained regularization program for inverting noisy linear algebraic and integral equations. Comput. Phys. Commun. 1982, 27, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghezzi, M.; Pescina, S.; Padula, C.; Santi, P.; Del Favero, E.; Cantù, L.; Nicoli, S. Polymeric micelles in drug delivery: An insight of the techniques for their characterization and assessment in biorelevant conditions. J. Control. Release 2021, 332, 312–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Nowell, C.J.; Cipolla, D.; Rades, T.; Boyd, B.J. Direct Comparison of Standard Transmission Electron Microscopy and Cryogenic-TEM in Imaging Nanocrystals Inside Liposomes. Mol. Pharm. 2019, 16, 1775–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calzaferri, G.; Gfeller, N. Thionine in the Cage of Zeolite L. J. Phys. Chem. 1992, 96, 3428–3435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roulia, M.; Vassiliadis, A.A. Clay-Catalyzed Phenomena of Cationic-Dye Aggregation and Hydroxo-Chromium Oligomerization. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2009, 122, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelley, E.E. Spectral Absorption and Fluorescence of Dyes in the Molecular State. Nature 1936, 138, 1009–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, T. Excitons in J-Aggregates with Hierarchical Structure. Supramol. Sci. 1998, 5, 343–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitsikalis, M.; Siakali-Kioulafa, E.; Hadjichristidis, N. Block Copolymers of Styrene and Stearyl Methacrylate. Synthesis and Micellization Properties in Selective Solvents. Macromolecules 2000, 33, 5460–5469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | PNVP 1 | PNVP-b-PVEs 1 | NVP 2 | PVEs 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mn ×103 (Da) | Đ | Mn ×103 (Da) | Đ | Molar Ratio (%) | Molar Ratio (%) | |

| PNVP-b-PVBu #1 | 8.5 | 1.30 | 16.0 | 1.90 | 22 | 78 |

| PNVP-b-PVBu #2 | 28.0 | 1.27 | 32.0 | 1.32 | 84 | 16 |

| PNVP-b-PVBu #3 | 8.9 | 1.35 | 17.5 | 1.40 | 57 | 43 |

| PNVP-b-PVBu #4 | 8.9 | 1.35 | 15.5 | 1.54 | 48 | 52 |

| PNVP-b-PVBu #5 | 8.5 | 1.30 | 13.0 | 1.55 | 56 | 44 |

| PNVP-b-PVDc #1 | 8.5 | 1.30 | 12.5 | 1.31 | 63 | 37 |

| PNVP-b-PVDc #2 | 5.5 | 1.47 | 12.5 | 1.60 | 38 | 62 |

| PNVP-b-PVDc #3 | 8.5 | 1.30 | 11.0 | 1.45 | 56 | 44 |

| PNVP-b-PVDc #4 | 9.5 | 1.36 | 10.5 | 1.36 | 93 | 7 |

| PNVP-b-PVSt #1 | 8.5 | 1.30 | 10.5 | 1.44 | 78 | 22 |

| PNVP-b-PVSt #2 | 7.5 | 1.30 | 10.4 | 1.51 | 61 | 39 |

| PNVP-b-PVSt #3 | 8.1 | 1.30 | 10.9 | 1.37 | 85 | 15 |

| PNVP-b-PVSt #4 | 8.1 | 1.30 | 12.5 | 1.22 | 83 | 17 |

| PNVP-b-PVSt #5 | 5.5 | 1.47 | 9.0 | 1.62 | 40 | 60 |

| Sample | D0 ×108 (cm2/s) | KD | Rh0 (nm) | Rh1,0 (nm) | Rh2,0 (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PNVP-b-PVBu #1 | 2.653 | −86.11 | 92.4 | - | - |

| PNVP-b-PVBu #2 | 4.813 | 177.46 | 50.9 | 30.8 | 127.6 |

| PNVP-b-PVBu #3 | 4.392 | −174.02 | 55.8 | 23.1 | 104.6 |

| PNVP-b-PVBu #4 | 3.645 | −149.42 | 67.3 | 29.5 | 99.2 |

| PNVP-b-PVBu #5 | 6.198 | 362.45 | 39.6 | 20.3 | 115.7 |

| Sample | D0 ×108 (cm2/s) | KD | Rh0 (nm) | Rh1,0 (nm) | Rh2,0 (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PNVP-b-PVDc #1 | 5.84 | −71 | 42.0 | 24.2 | 91.8 |

| PNVP-b-PVDc #2 | 2.88 | −502 | 85.0 | 15.6 | 95.4 |

| PNVP-b-PVDc #3 | 3.93 | −73 | 62.4 | 35.6 | 131.1 |

| PNVP-b-PVDc #4 | 6.62 | 981 | 37.0 | 15.4 | 136.4 |

| Sample | D0 ×108 (cm2/s) | KD | Rh0 (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PNVP-b-PVSt #1 | 4.37 | 65.8 | 56.1 |

| PNVP-b-PVSt #2 | 3.73 | 69.3 | 65.7 |

| PNVP-b-PVSt #3 | 4.52 | 693.0 | 54.2 |

| PNVP-b-PVSt #4 | 4.35 | 187.8 | 56.4 |

| PNVP-b-PVSt #5 | 2.54 | 69.0 | 96.6 |

| Sample | PVSt 1 Molar Ratio (%) | (Mw)micc 2 (Daltons) | (A2)micc 2 (cm3mol/g2) | Nw |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PNVP-b-PVSt #1 | 22 | 4.02 × 107 | 2.15 × 10−5 | 3828 |

| PNVP-b-PVSt #2 | 39 | 1.18 × 108 | 1.65 × 10−5 | 11,346 |

| PNVP-b-PVSt #3 | 15 | 5.98 × 107 | 1.85 × 10−5 | 5486 |

| PNVP-b-PVSt #4 | 17 | 4.77 × 107 | 1.64 × 10−5 | 3816 |

| PNVP-b-PVSt #5 | 60 | 4.35 × 108 | 1.87 × 10−6 | 48,333 |

| Sample | Cur. 1 | A 2 (a.u.) | Pol. 3 (μg/mL) | DIF 4 (μg/mL) | LD 5 (μg/mL) | DLC (%) | DLE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PNVP-b-PVBu #1 | 1% | 1.85 | 481.20 | 12.60 | 9.19 | 1.91 | 73.01 |

| 2% | 1.78 | 670.09 | 14.59 | 8.83 | 1.32 | 60.54 | |

| 3% | 2.85 | 653.62 | 17.93 | 14.33 | 2.19 | 79.90 | |

| 4% | 2.74 | 643.69 | 21.22 | 13.76 | 2.14 | 64.85 | |

| PNVP-b-PVBu #2 | 1% | 0.45 | 543.50 | 6.23 | 2.00 | 0.37 | 32.08 |

| 2% | 1.57 | 604.45 | 14.17 | 7.75 | 1.28 | 54.72 | |

| 3% | 1.85 | 599.34 | 17.42 | 9.19 | 1.53 | 52.75 | |

| 4% | 2.55 | 621.73 | 21.75 | 12.79 | 2.06 | 58.80 | |

| PNVP-b-PVBu #3 | 1% | 0.38 | 583.23 | 6.33 | 1.64 | 0.28 | 25.90 |

| 2% | 1.84 | 650.11 | 14.12 | 9.14 | 1.41 | 64.73 | |

| 3% | 1.97 | 637.42 | 17.22 | 9.81 | 1.54 | 56.94 | |

| 4% | 2.34 | 630.40 | 21.68 | 11.71 | 1.86 | 54.01 | |

| PNVP-b-PVBu #4 | 1% | 0.37 | 537.80 | 5.97 | 1.59 | 0.30 | 26.61 |

| 2% | 1.94 | 632.52 | 14.38 | 9.65 | 1.53 | 67.13 | |

| 3% | 1.93 | 619.94 | 17.38 | 9.60 | 1.55 | 55.23 | |

| 4% | 2.89 | 638.81 | 22.02 | 14.53 | 2.27 | 65.99 |

| Sample | Cur. 1 | A 2 (a.u.) | Pol. 3 (μg/mL) | DIF 4 (μg/mL) | LD 5 (μg/mL) | DLC (%) | DLE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PNVP-b-PVDc #1 | 1% | 0.61 | 684.13 | 6.18 | 4.82 | 0.71 | 78.05 |

| 2% | 2.12 | 746.70 | 13.79 | 2.82 | 0.38 | 20.46 | |

| 3% | 2.64 | 765.59 | 17.73 | 10.58 | 1.38 | 59.64 | |

| 4% | 1.92 | 767.62 | 21.11 | 13.25 | 1.73 | 62.77 | |

| PNVP-b-PVDc #2 | 1% | 0.73 | 601.64 | 6.37 | 9.55 | 1.59 | 49.88 |

| 2% | 2.17 | 668.63 | 13.92 | 3.44 | 0.51 | 24.69 | |

| 3% | 2.68 | 676.55 | 17.69 | 10.83 | 1.60 | 61.25 | |

| 4% | 1.69 | 641.88 | 20.09 | 13.45 | 2.10 | 66.96 | |

| PNVP-b-PVDc #3 | 1% | 0.93 | 615.39 | 6.91 | 8.37 | 1.36 | 21.18 |

| 2% | 2.08 | 619.55 | 14.25 | 4.46 | 0.72 | 31.33 | |

| 3% | 2.52 | 592.96 | 17.34 | 10.37 | 1.75 | 59.81 | |

| 4% | 2.19 | 624.96 | 21.81 | 12.63 | 2.02 | 57.93 | |

| PNVP-b-PVDc #4 | 1% | 0.86 | 560.35 | 66.07 | 10.94 | 1.95 | 65.54 |

| 2% | 1.96 | 552.45 | 13.03 | 4.11 | 0.74 | 31.50 | |

| 3% | 2.21 | 546.12 | 16.24 | 9.76 | 1.79 | 60.06 | |

| 4% | 2.81 | 544.62 | 19.41 | 11.04 | 2.03 | 56.87 |

| Sample | Cur. 1 | A 2 (a.u.) | Pol. 3 (μg/mL) | DIF 4 (μg/mL) | LD 5 (μg/mL) | DLC (%) | DLE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PNVP-b-PVSt #1 | 1% | 0.63 | 553.69 | 6.20 | 2.92 | 0.53 | 47.17 |

| 2% | 1.48 | 570.94 | 13.26 | 7.29 | 1.28 | 54.98 | |

| 3% | 1.61 | 522.77 | 14.91 | 7.96 | 1.52 | 53.36 | |

| 4% | 2.24 | 567.39 | 19.22 | 11.19 | 1.97 | 58.25 | |

| PNVP-b-PVSt #2 | 1% | 0.67 | 567.63 | 6.25 | 3.13 | 0.55 | 50.04 |

| 2% | 1.74 | 571.86 | 12.87 | 8.63 | 1.51 | 67.01 | |

| 3% | 1.95 | 580.85 | 16.02 | 9.70 | 1.67 | 60.59 | |

| 4% | 2.38 | 577.08 | 19.90 | 11.91 | 2.06 | 59.87 | |

| PNVP-b-PVSt #3 | 1% | 0.68 | 554.27 | 6.15 | 3.18 | 0.57 | 51.70 |

| 2% | 1.57 | 574.55 | 12.91 | 7.75 | 1.35 | 60.06 | |

| 3% | 1.86 | 574.47 | 16.01 | 9.24 | 1.61 | 57.74 | |

| 4% | 2.51 | 591.43 | 19.06 | 12.58 | 2.13 | 65.99 | |

| PNVP-b-PVSt #4 | 1% | 0.48 | 554.60 | 5.42 | 2.15 | 0.39 | 39.72 |

| 2% | 1.48 | 560.06 | 11.74 | 7.29 | 1.30 | 62.12 | |

| 3% | 2.04 | 558.56 | 14.81 | 10.17 | 1.82 | 68.64 | |

| 4% | 2.19 | 566.32 | 18.06 | 10.94 | 1.93 | 60.55 |

| Sample | Ind. 1 (w/w) | A 2 (a.u.) | Pol. 3 (μg/mL) | DIF 4 (μg/mL) | LD 5 (μg/mL) | DLC (%) | DLE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PNVP-b-PVBu #1 | 10% | 0.32 | 178.34 | 17.16 | 12.53 | 7.02 | 73.00 |

| 15% | 0.69 | 169.51 | 24.48 | 28.93 | 17.07 | 118.17 | |

| 20% | 0.80 | 168.85 | 34.39 | 33.98 | 20.13 | 98.83 | |

| PNVP-b-PVBu #2 | 10% | 0.27 | 168.70 | 15.97 | 10.56 | 6.26 | 66.16 |

| 15% | 0.37 | 164.15 | 25.65 | 14.93 | 9.09 | 58.21 | |

| 20% | 0.45 | 166.63 | 33.01 | 18.24 | 10.95 | 55.26 | |

| PNVP-b-PVBu #3 | 10% | 0.32 | 180.86 | 16.18 | 12.55 | 6.94 | 77.58 |

| 15% | 0.40 | 182.12 | 25.69 | 16.12 | 8.85 | 62.76 | |

| 20% | 0.61 | 187.77 | 34.82 | 25.70 | 13.69 | 73.82 | |

| PNVP-b-PVBu #4 | 10% | 0.30 | 171.48 | 16.54 | 11.90 | 6.94 | 71.95 |

| 15% | 0.32 | 173.91 | 23.46 | 42.45 | 7.16 | 53.07 | |

| 20% | 0.56 | 173.42 | 32.31 | 23.32 | 13.45 | 72.18 | |

| PNVP-b-PVBu #5 | 10% | 0.30 | 165.14 | 15.93 | 11.75 | 7.11 | 73.73 |

| 15% | 0.43 | 165.03 | 24.82 | 17.41 | 10.55 | 70.13 | |

| 20% | 0.61 | 164.20 | 35.00 | 25.46 | 15.51 | 72.75 |

| Sample | Ind. 1 (w/w) | A 2 (a.u.) | Pol. 3 (μg/mL) | DIF 4 (μg/mL) | LD 5 (μg/mL) | DLC (%) | DLE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PNVP-b-PVDc #1 | 10% | 0.24 | 73.25 | 17.63 | 9.18 | 12.53 | 52.05 |

| 15% | 0.32 | 94.67 | 16.09 | 12.57 | 13.28 | 78.09 | |

| 20% | 0.49 | 98.63 | 19.59 | 20.06 | 20.34 | 102.38 | |

| PNVP-b-PVDc #2 | 10% | 0.39 | 95.43 | 10.15 | 15.66 | 16.41 | 154.22 |

| 15% | 0.55 | 98.59 | 15.65 | 22.65 | 22.98 | 144.74 | |

| 20% | 0.69 | 101.96 | 19.60 | 29.14 | 28.58 | 148.66 | |

| PNVP-b-PVDc #3 | 10% | 0.20 | 107.78 | 10.36 | 7.46 | 6.92 | 72.02 |

| 15% | 0.33 | 109.01 | 17.25 | 12.88 | 11.82 | 74.97 | |

| 20% | 0.48 | 105.61 | 19.48 | 19.90 | 18.84 | 102.16 | |

| PNVP-b-PVDc #4 | 10% | 0.26 | 97.04 | 10.24 | 10.00 | 10.31 | 97.64 |

| 15% | 0.31 | 94.03 | 16.07 | 11.98 | 12.75 | 74.59 | |

| 20% | 0.52 | 92.95 | 19.92 | 21.67 | 23.32 | 108.77 |

| Sample | Ind. 1 (w/w) | A 2 (a.u.) | Pol. 3 (μg/mL) | DIF 4 (μg/mL) | LD 5 (μg/mL) | DLC (%) | DLE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PNVP-b-PVSt #1 | 10% | 0.39 | 165.90 | 15.95 | 15.66 | 9.44 | 98.19 |

| 15% | 0.46 | 164.14 | 23.65 | 18.75 | 11.42 | 79.26 | |

| 20% | 0.55 | 166.71 | 38.53 | 22.68 | 13.60 | 58.87 | |

| PNVP-b-PVSt #2 | 10% | 0.73 | 32.93 | 3.27 | 31.06 | 9.43 | 94.9 |

| 15% | 0.36 | 166.27 | 24.02 | 14.17 | 8.52 | 58.98 | |

| 20% | 0.65 | 166.17 | 33.13 | 27.49 | 16.54 | 82.98 | |

| PNVP-b-PVSt #3 | 10% | 0.45 | 165.82 | 18.98 | 18.22 | 10.99 | 96.01 |

| 15% | 0.55 | 181.78 | 27.56 | 22.82 | 12.55 | 82.80 | |

| 20% | 0.62 | 168.32 | 33.06 | 25.75 | 15.30 | 77.90 | |

| PNVP-b-PVSt #4 | 10% | 0.41 | 172.92 | 16.89 | 16.71 | 9.66 | 98.93 |

| 15% | 0.51 | 167.90 | 24.12 | 21.07 | 12.55 | 87.33 | |

| 20% | 0.55 | 171.99 | 35.92 | 22.74 | 13.22 | 63.30 | |

| PNVP-b-PVSt #5 | 10% | 0.84 | 157.27 | 16.47 | 35.96 | 22.86 | 218.31 |

| 15% | 0.84 | 152.17 | 25.01 | 35.64 | 23.42 | 142.47 | |

| 20% | 0.90 | 150.52 | 33.06 | 38.35 | 25.48 | 116.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Plachouras, N.V.; Gkolemi, A.-M.; Argyropoulos, A.; Bouzoukas, A.; Papazoglou, T.-P.; Roka, N.; Pitsikalis, M. Amphiphilic Diblock Copolymers of Poly(N-vinyl pyrrolidone) and Poly(vinyl esters) Bearing N-Alkyl Side Chains for the Encapsulation of Curcumin and Indomethacin. Polymers 2025, 17, 2852. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17212852

Plachouras NV, Gkolemi A-M, Argyropoulos A, Bouzoukas A, Papazoglou T-P, Roka N, Pitsikalis M. Amphiphilic Diblock Copolymers of Poly(N-vinyl pyrrolidone) and Poly(vinyl esters) Bearing N-Alkyl Side Chains for the Encapsulation of Curcumin and Indomethacin. Polymers. 2025; 17(21):2852. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17212852

Chicago/Turabian StylePlachouras, Nikolaos V., Aikaterini-Maria Gkolemi, Alexandros Argyropoulos, Athanasios Bouzoukas, Theodosia-Panagiota Papazoglou, Nikoletta Roka, and Marinos Pitsikalis. 2025. "Amphiphilic Diblock Copolymers of Poly(N-vinyl pyrrolidone) and Poly(vinyl esters) Bearing N-Alkyl Side Chains for the Encapsulation of Curcumin and Indomethacin" Polymers 17, no. 21: 2852. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17212852

APA StylePlachouras, N. V., Gkolemi, A.-M., Argyropoulos, A., Bouzoukas, A., Papazoglou, T.-P., Roka, N., & Pitsikalis, M. (2025). Amphiphilic Diblock Copolymers of Poly(N-vinyl pyrrolidone) and Poly(vinyl esters) Bearing N-Alkyl Side Chains for the Encapsulation of Curcumin and Indomethacin. Polymers, 17(21), 2852. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17212852