Development of Infrared Transmission Flame-Retardant Polyethylene Melt Blends and Melt-Blown Nonwovens

Abstract

1. Introduction

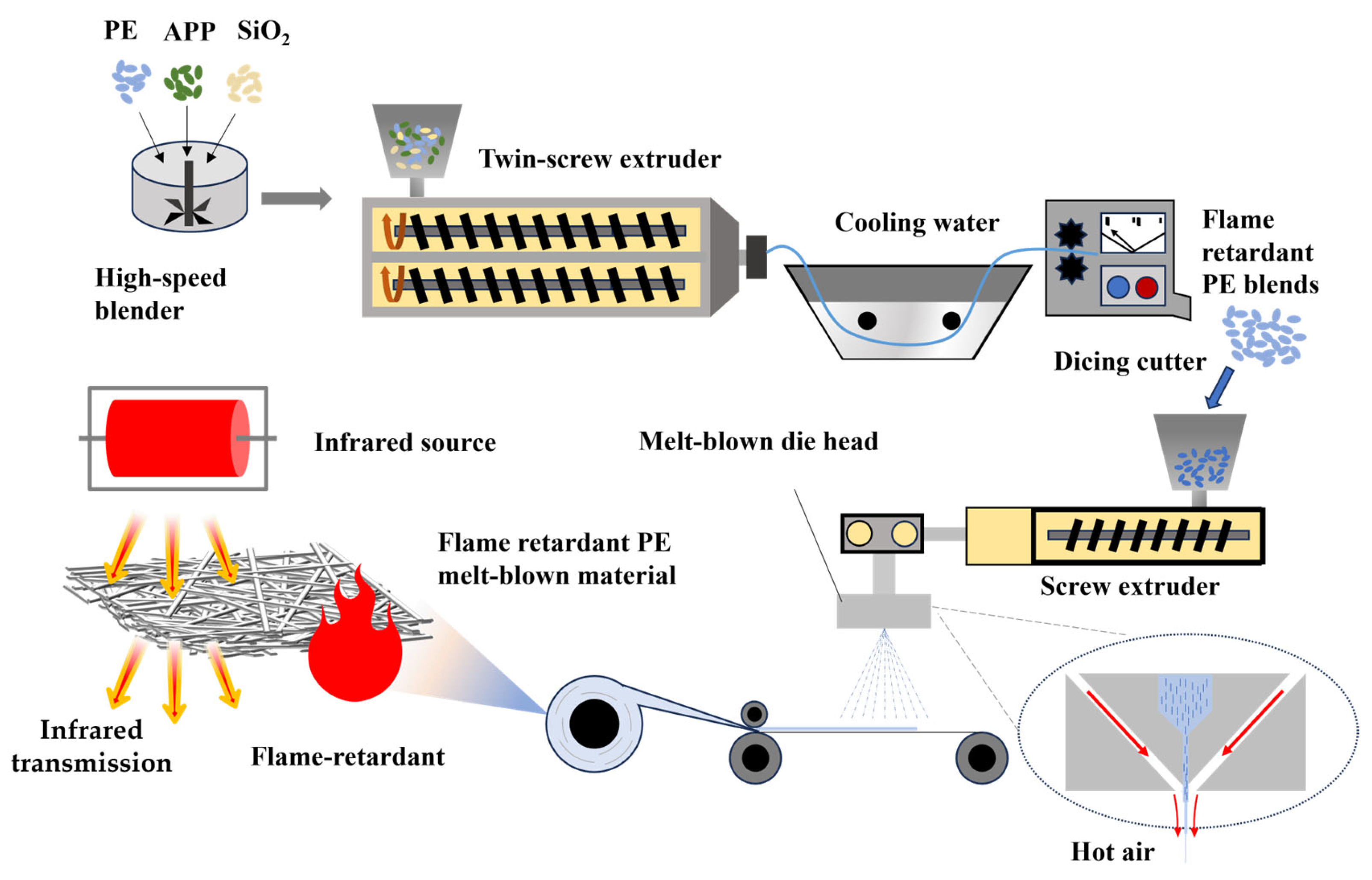

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

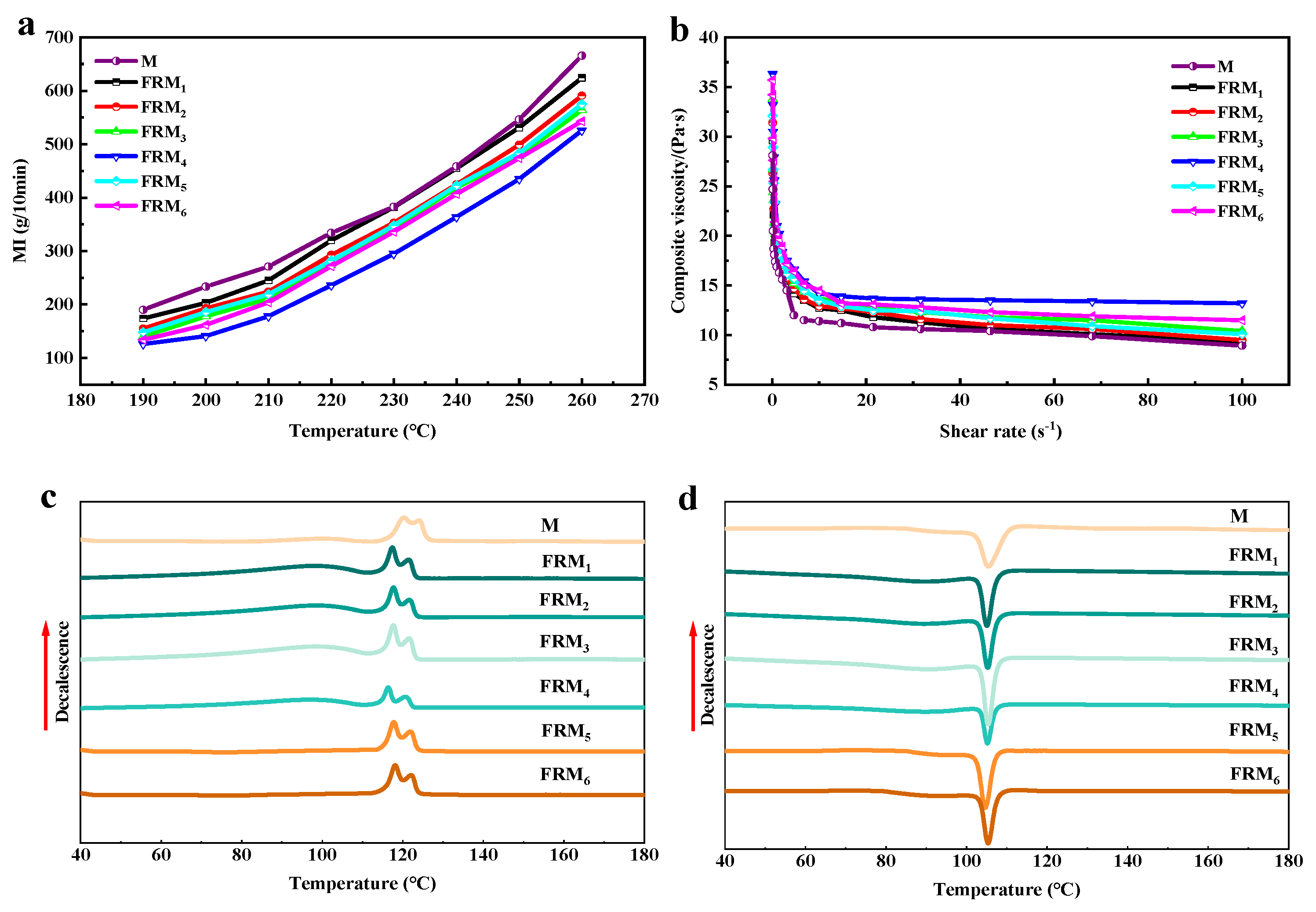

3.1. Analysis of Melt Fluidity and Rheological Properties of Flame-Retardant Blends

3.2. Analysis of Thermal-Crystallization Performance of Flame-Retardant Blends

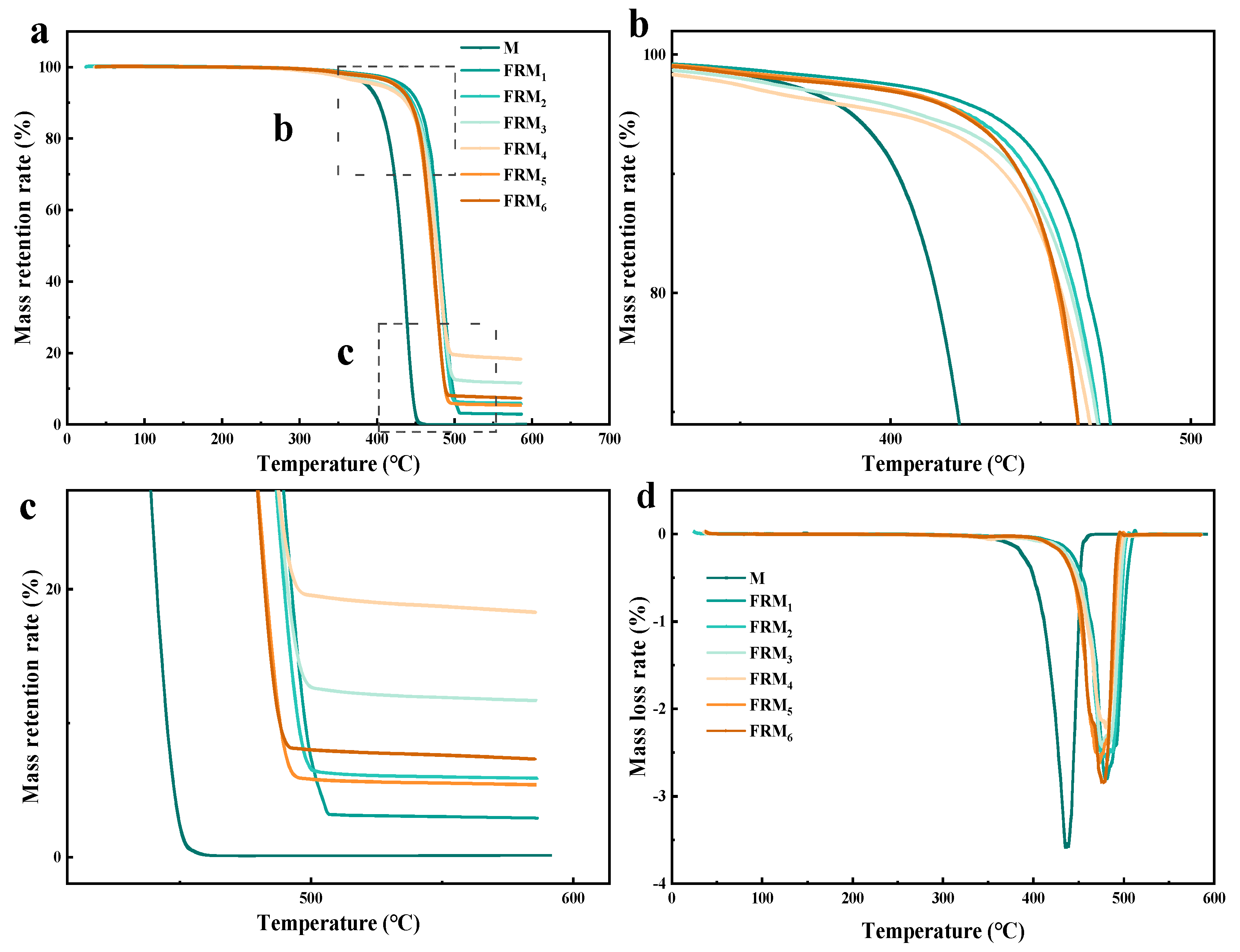

3.3. Analysis of Thermal Stability of Flame-Retardant Blends

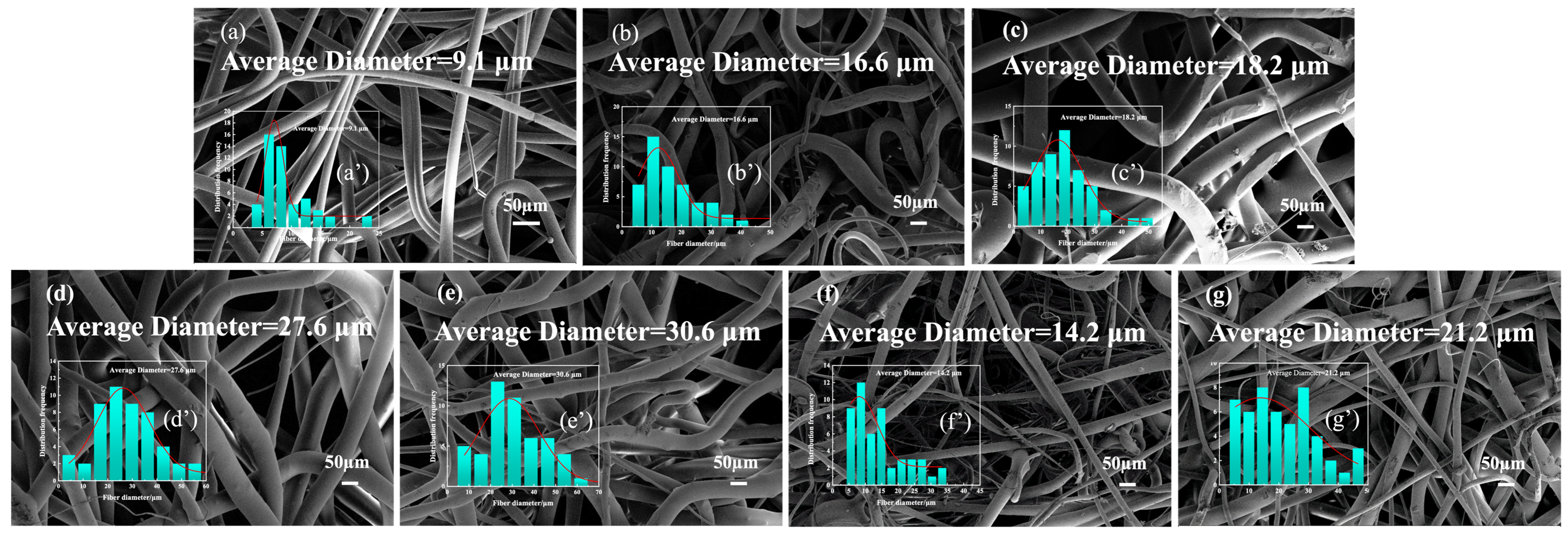

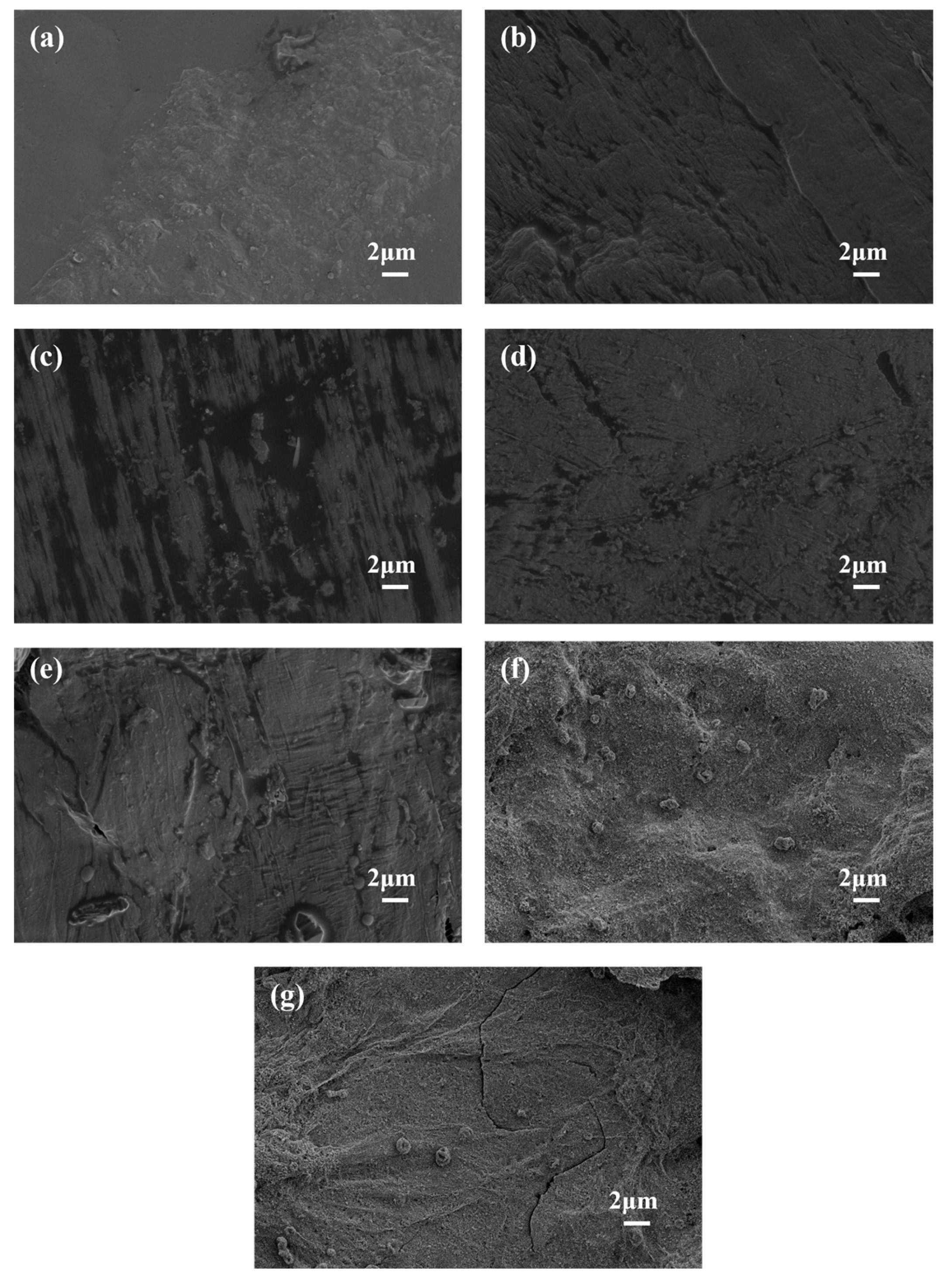

3.4. Analysis of Surface Morphology and Diameter of Flame-Retardant Melt-Blown Materials

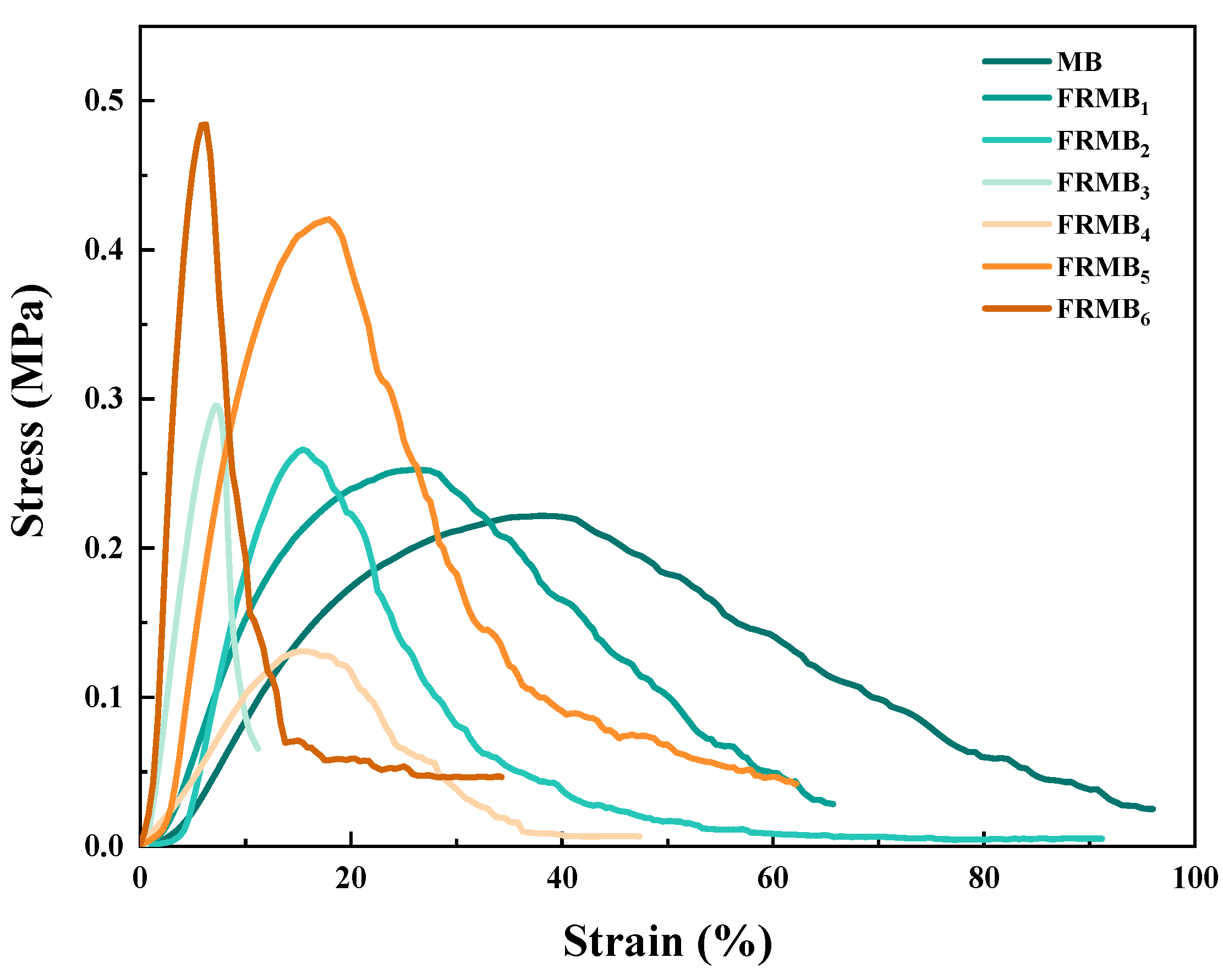

3.5. Analysis of the Mechanical Properties of Flame-Retardant Melt-Blown Materials

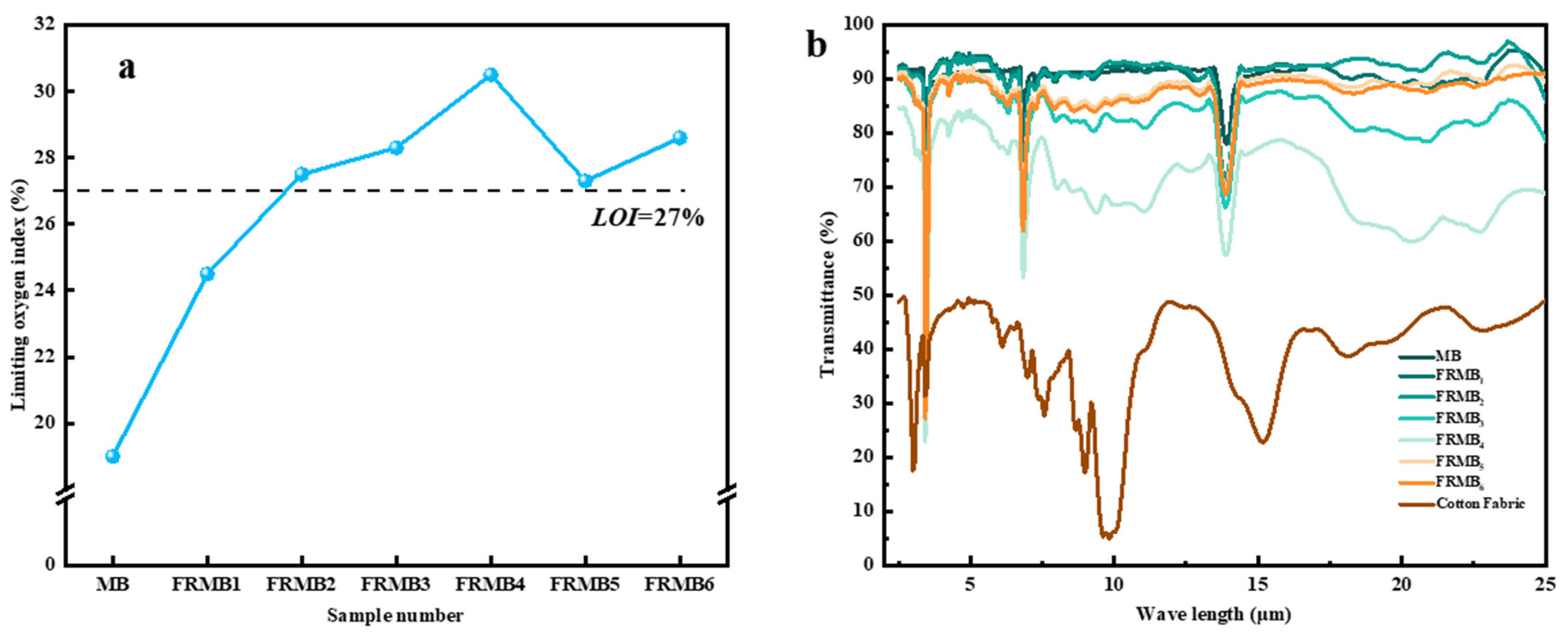

3.6. Analysis of the Flame-Retardant Performance of Flame-Retardant Melt-Blown Materials

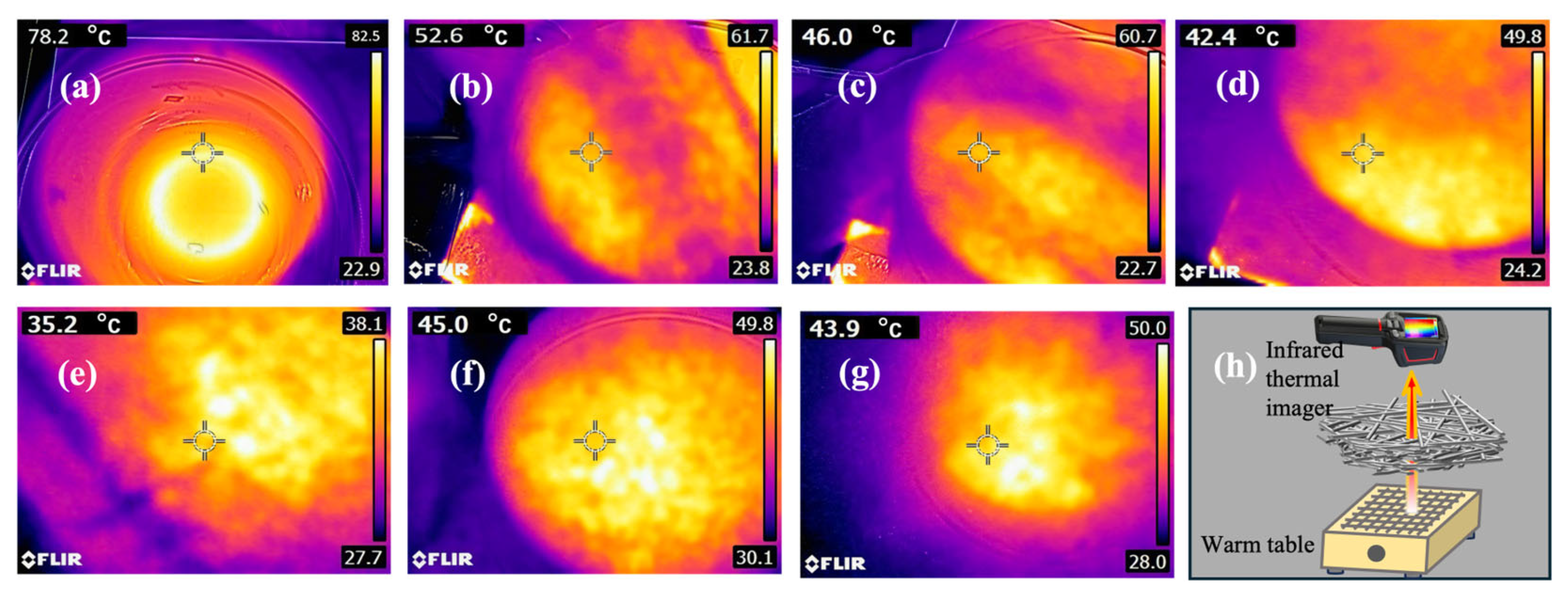

3.7. Infrared Performance Analysis of Flame-Retardant Melt-Blown Materials

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Song, Y.; Wu, G.; Peng, J.; Zhang, C.; Wang, D.; Zheng, Q. Vulcanization kinetics of natural rubber and strain softening behaviors of gum vulcanizates tailored by deep eutectic solvents. Polymer 2022, 263, 125504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yang, S.; Liu, Y.; Wang, W.; Li, Z.; Liu, W.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; et al. Ultra-stable, lightweight and superelastic waste flax-based aerogel for multifunctional applications. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 220, 119220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, J.; Liu, L.; Yu, Z.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, L. Silane coupling agent 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane modified silica/epoxidized solution-polymerized styrene butadiene rubber nanocomposites. Polym. Compos. 2023, 44, 6957–6968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, L.; Feng, W.; Li, Q. Beyond the Visible: Bioinspired Infrared Adaptive Materials. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2004754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, J.K.; Huang, X.; Boriskina, S.V.; Loomis, J.; Xu, Y.; Chen, G. Infrared-Transparent Visible-Opaque Fabrics for Wearable Personal Thermal Management. ACS Photonics 2015, 2, 769–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnihotri, S.; Sheikh, J.N.; Singh, S.P.; Behera, B.K. Flame-retardant textile structural composites for construction application: A review. J. Mater. Sci. 2024, 59, 1788–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Hao, X.; Teng, D.; Zhao, T.; Zeng, Y. Micro/nanofibrous nonwovens with high filtration performance and radiative heat dissipation property for personal protective face mask. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 423, 130175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Deak, N.; Wang, Z.; Yu, H.; Hameleers, L.; Jurak, E.; Deuss, P.J.; Barta, K. Tunable and functional deep eutectic solvents for lignocellulose valorization. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Xia, X.; Hussain, M.; Song, Y.; Zheng, Q. Linear and nonlinear rheological behaviors of silica filled nitrile butadiene rubber. Polymer 2018, 156, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Totolin, V.; Sarmadi, M.; Manolache, S.O.; Denes, F.S. Environmentally friendly flame-retardant materials produced by atmospheric pressure plasma modifications. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2012, 124, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, W.; Wang, S.; Yang, Y.; Li, H.; Sun, J.; Gu, X.; Zhang, S. Self-intumescent polyelectrolyte for flame retardant poly (lactic acid) nonwovens. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 282, 124497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Row, K.H. Purification of antibiotics from the millet extract using hybrid molecularly imprinted polymers based on deep eutectic solvents. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 16997–17004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.; Chen, K.; Ma, D.; Lin, H.; Liu, Z.; Qin, S.; Luo, Y. Synthesis of high specific surface area silica aerogel from rice husk ash via ambient pressure drying. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2018, 539, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Fang, H.; Liu, X.; Xu, B.; Rao, Z. Novel Silica Filled Deep Eutectic Solvent Based Nanofluids for Energy Transportation. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 20159–20169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Liu, M.; Cai, J.; Li, Z.; Teng, Z.; Hao, Y.; Cui, Y.; Yu, J.; Wang, L.; Qin, X. Waste Cotton-Derived Fiber-Based Thermoelectric Aerogel for Wearable and Self-Powered Temperature–Compression Strain Dual-Parameter Sensing. Engineering 2024, 39, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidur, R.M.; Mushtaq, A.; Huang, S.; Zhang, R.; Lu, Y.; Le, Y.; Jing, G.; Ahmad, Z.; Iqbal, M.Z.; Kong, X. Synthesis of ultra-small MXene nanorods for enhanced photothermal therapy of breast cancer in vitro. Mater. Lett. 2023, 353, 135324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogachuk, B.E.; Okolie, J.A. Waste tires based biorefinery for biofuels and value-added materials production. Chem. Eng. J. Adv. 2023, 14, 100476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Y.H.; Lock, S.S.M.; Wong, M.K.; Yiin, C.L.; Loy, A.C.M.; Cheah, K.W.; Chai, S.Y.W.; Li, C.; How, B.S.; Chin, B.L.F.; et al. A state-of-the-art review on capture and separation of hazardous hydrogen sulfide (H2S): Recent advances, challenges and outlook. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 314, 120219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaid, A.; Ashraf, H.T.; Mustaghees, M.; Khalid, A. Fire-retardant carbon/glass fabric-reinforced epoxy sandwich composites for structural applications. Polym. Compos. 2021, 42, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.; Yasin, S.; Uddin, A.; Ashraf, H.T.; Feichao, Z.; Bin, Y.; Zheng, Q.; Song, Y. High-performance volatile organic compounds free silica-filled butadiene rubber green nanocomposites using ionic liquid peroxide vulcanization. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 33, 9752–9761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.; Xiao, K.; Yu, J.; Ding, B. Fabrication of hierarchical structured SiO2/polyetherimide-polyurethane nanofibrous separators with high performance for lithium ion batteries. Electrochim. Acta 2015, 154, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barczewski, M.; Hejna, A.; Sałasińska, K.; Aniśko, J.; Piasecki, A.; Skórczewska, K.; Andrzejewski, J. Thermomechanical and Fire Properties of Polyethylene-Composite-Filled Ammonium Polyphosphate and Inorganic Fillers: An Evaluation of Their Modification Efficiency. Polymers 2022, 14, 2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, L.; Liu, J.; Chen, S.; Xu, Z.; Liu, P. Synthesis of melamine phenyl hypophosphite and its synergistic flame retardance with SiO2 on polypropylene. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2022, 147, 6207–6217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Xia, Y.; Mao, Z.; Wang, L.; Guan, Y.; Zheng, A. Synergistic Effect of SiO2 on Intumescent Flame-retardant Polypropylene. Polym. Polym. Compos. 2013, 21, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Singh, M.K.; Rangappa, S.M.; Siengchin, S.; Dhakal, H.N.; Zafar, S. Recent progress in additive inorganic flame retardants polymer composites: Degradation mechanisms, modeling and applications. Heliyon 2024, 10, e39662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 5455-2014; Textiles-Burning Behaviour-Determination of Damaged Length, Afterglow Time and Afterflame Time of Vertically Oriented Specimens. General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2014.

- GB/T 5454-1997; Textile-Burning Behaviour-Oxygen Index Method. The State Bureau of Quality and Technical Supervision: Beijing, China, 1997.

- Andreev, M.; Nicholson, D.A.; Kotula, A.; Moore, J.D.; den Doelder, J.; Rutledge, G.C. Rheology of crystallizing LLDPE. J. Rheol. 2020, 64, 1379–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coimbra, A.; Sarazin, J.; Bourbigot, S.; Legros, G.; Consalvi, J.-L. A semi-global reaction mechanism for the thermal decomposition of low-density polyethylene blended with ammonium polyphosphate and pentaerythritol. Fire Saf. J. 2022, 133, 103649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Liu, P.; Gao, C.; Wang, F.; Ding, Y.; Zhang, S.; Yang, M. Synergistic effect of cocondensed nanosilica in intumescent flame-retardant polypropylene. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2019, 30, 1116–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhao, J.; Guo, Y.; Meng, Q.; Chen, K.; Pan, B.; Zhou, X. Synthesis and application of silicone modified flame retardant for polyester fabric. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2024, 680, 132679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, R.; Chaudhary, M.L.; Patel, Y.N.; Chaudhari, K.; Gupta, R.K. Fire-Resistant Coatings: Advances in Flame-Retardant Technologies, Sustainable Approaches, and Industrial Implementation. Polymers 2025, 17, 1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielecka, M.; Rabajczyk, A.; Pastuszka, Ł.; Jurecki, L. Flame Resistant Silicone-Containing Coating Materials. Coatings 2020, 10, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, P.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Gu, X.; Zhang, S. Intumescent flame retardant finishing for polypropylene nonwoven fabric. J. Ind. Text. 2020, 51, 5186S–5201S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Samples Label | Mass Ratio of M (%) | Mass Ratio of APP (%) | Mass Ratio of SiO2 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| FRM1 | 95 | 5 | 0 |

| FRM2 | 90 | 10 | 0 |

| FRM3 | 85 | 15 | 0 |

| FRM4 | 80 | 20 | 0 |

| FRM5 | 89.5 | 10 | 0.5 |

| FRM6 | 89 | 10 | 1 |

| Zone | First Zone | Second Zone | Third Zone | Fourth Zone | Fifth Zone | Material |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature/°C | 180 | 190 | 195 | 200 | 200 | 180 |

| First Zone | Second Zone | Third Zone | Fourth Zone | Die | Hot Air | Spinneret Hole | Pick-Up Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | 180 °C | 210 °C | 230 °C | 230 °C | 230 °C | 230 °C | 0.5 mm | 20 cm |

| Sample Labels | Tcc (°C) | ΔHcc (J/g) | Tm (°C) | ΔHm (J/g) | Xc (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | 104.7 ± 0.3 | 38.2 ± 1.2 | 120.2 ± 0.4 | 44.6 ± 1.4 | 21.7 ± 0.5 |

| FRM1 | 105.2 ± 0.3 | 53.5 ± 1.5 | 118.3 ± 0.4 | 45.3 ± 1.5 | 22.3 ± 0.5 |

| FRM2 | 105.3 ± 0.3 | 55.1 ± 1.6 | 118.0 ± 0.3 | 47.2 ± 1.6 | 22.6 ± 0.5 |

| FRM3 | 105.8 ± 0.4 | 73.3 ± 2.1 | 117.7 ± 0.3 | 52.5 ± 1.7 | 23.7 ± 0.6 |

| FRM4 | 105.7 ± 0.3 | 36.4 ± 1.1 | 116.1 ± 0.3 | 38.4 ± 1.3 | 23.4 ± 0.6 |

| FRM5 | 105.8 ± 0.4 | 70.9 ± 2.0 | 117.9 ± 0.4 | 56.7 ± 1.8 | 22.8 ± 0.5 |

| FRM6 | 106.1 ± 0.4 | 72.1 ± 2.2 | 118.8 ± 0.3 | 58.1 ± 1.9 | 23.2 ± 0.6 |

| Sample Labels | T5% (°C) | T50% (°C) | Char Residue (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| M | 392.6 ± 1.2 | 433.1 ± 1.5 | 0.1 ± 0.05 |

| FRM1 | 443.8 ± 1.1 | 481.0 ± 1.3 | 2.9 ± 0.2 |

| FRM2 | 438.3 ± 1.0 | 477.6 ± 1.4 | 5.9 ± 0.3 |

| FRM3 | 409.5 ± 1.2 | 477.6 ± 1.3 | 11.7 ± 0.3 |

| FRM4 | 401.5 ± 1.1 | 476.5 ± 1.2 | 18.3 ± 0.4 |

| FRM5 | 424.0 ± 1.2 | 470.9 ± 1.5 | 5.4 ± 0.3 |

| FRM6 | 423.4 ± 1.1 | 471.1 ± 1.4 | 7.3 ± 0.3 |

| Sample Number | Flame Duration (s) | Afterglow Time (s) | Droplet Generation |

|---|---|---|---|

| MB | 3.73 | 0 | Yes |

| FRMB1 | 1.34 | 0 | Yes |

| FRMB2 | 0 | 0 | Yes |

| FRMB3 | 0 | 0 | no |

| FRMB4 | 0 | 0 | no |

| FRMB5 | 0 | 0 | yes |

| FRMB6 | 0 | 0 | no |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

An, W.; Wei, Y.; Lin, Y.; Wang, S.; Li, C.; Yu, H.; Wu, X.; Zhu, Y.; Zhu, F.; Hussain, M. Development of Infrared Transmission Flame-Retardant Polyethylene Melt Blends and Melt-Blown Nonwovens. Polymers 2025, 17, 2854. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17212854

An W, Wei Y, Lin Y, Wang S, Li C, Yu H, Wu X, Zhu Y, Zhu F, Hussain M. Development of Infrared Transmission Flame-Retardant Polyethylene Melt Blends and Melt-Blown Nonwovens. Polymers. 2025; 17(21):2854. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17212854

Chicago/Turabian StyleAn, Weizhu, Yihui Wei, Youkuai Lin, Shihao Wang, Chengjian Li, Haiqian Yu, Xing Wu, Yinchao Zhu, Feichao Zhu, and Munir Hussain. 2025. "Development of Infrared Transmission Flame-Retardant Polyethylene Melt Blends and Melt-Blown Nonwovens" Polymers 17, no. 21: 2854. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17212854

APA StyleAn, W., Wei, Y., Lin, Y., Wang, S., Li, C., Yu, H., Wu, X., Zhu, Y., Zhu, F., & Hussain, M. (2025). Development of Infrared Transmission Flame-Retardant Polyethylene Melt Blends and Melt-Blown Nonwovens. Polymers, 17(21), 2854. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17212854