1. Introduction

There are many additive manufacturing (AM) processes that use different principles to construct physical objects. In 3D printing, in methods that use the principle of photopolymerization [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10], as a result of the curing process, the initially “liquid” photosensitive composition, due to the initiation and occurrence of a photochemical polymerization reaction of components by a radical or cationic mechanism [

1,

2,

3,

4,

6,

8,

9] under the influence of ultraviolet (UV) or visible (Vis) radiation from a 3D printer, is transformed into a “solid” polymer [

2,

3,

5,

6,

9,

10]. Moreover, the possibility of forming a three-dimensional network of chemical bonds, as well as its density, significantly influences the properties of the resulting material [

8,

9]. In order to form a unified polymer structure characterized by a dense network, necessary to impart good physical and mechanical properties to a 3D printed object, as well as high chemical [

2,

9] and thermal stability, crosslinking agents and/or active diluents [

1,

2,

4,

8,

9] are included in the formulation of the photosensitive composition. The spatial network of chemical bonds in the photopolymer composition implements the so-called “shape memory effect” (SME), which opens up new possibilities for the use of 3D-printed products [

4,

5,

8].

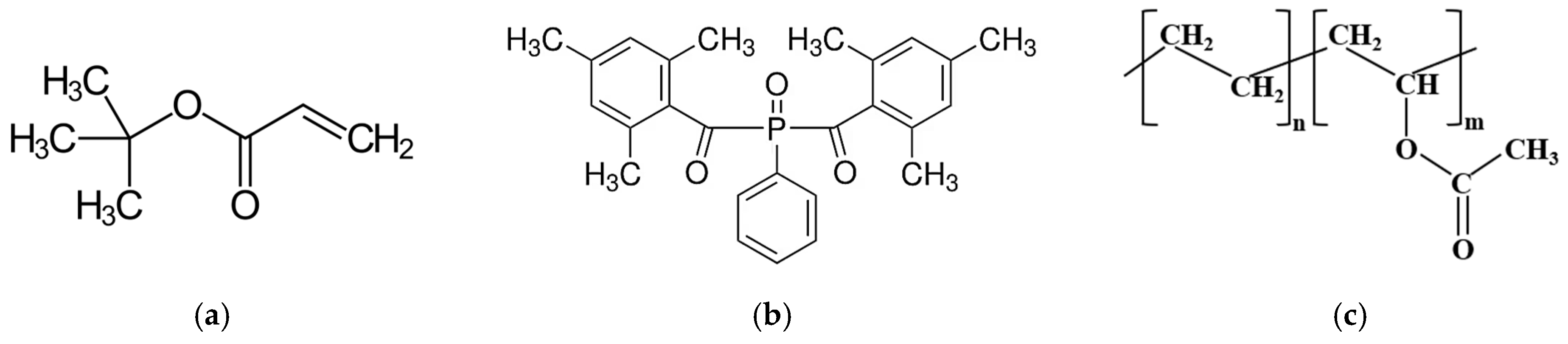

Acrylate and methacrylate monomers/oligomers are mainly used as the basis for photosensitive compositions for 3D printing [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

8,

9]. Due to the limited choice of components for low-viscosity photosensitive compositions (LPSC), typical representatives are methyl methacrylate (MMA) [

2], tert-butyl acrylate (tBA) [

8], 1,6-hexanediol diacrylate (HDDA) [

3,

6,

11], diethylene glycol diacrylate (DEGDA), 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate (HEMA) [

2] and triethylene glycol dimethacrylate (TEGDMA) [

2,

9]. The monomers MMA, tBA, and HEMA have only one acrylic group with an unsaturated bond in their chemical structure, therefore, they are not able to form a spatial network during photocuring and polymerize as a linear polymer with thermoplastic properties, soluble in polar solvents [

4,

9]. To branch the chain and form a network topology, it is necessary to use one or more monomers/oligomers with bi- or higher functionality, or to use crosslinking agents with C=C double bonds [

1,

2,

4]. Thus, the use of tBA together with bifunctional acrylates allows for the production of “smart” 3D products that have “switching segments” and “network nodes” in their structure and, accordingly, exhibit an SME [

8].

Acrylate-based LPSCs have significant drawbacks: high shrinkage during curing, which affects the geometric accuracy of 3D-printed objects [

4,

9]; anisotropy of properties and reduced interlayer adhesion in the resulting material, which leads to low physical and mechanical properties; high volatility and toxicity of components in the uncured state; and the ability to release unreacted substances from the cured material [

2,

3,

4]. Therefore, basic LPSCs require modification by adding special additives (“modifiers”) of various natures in the uncured state [

1,

2,

3,

4].

Ethylene-vinyl acetate copolymer (EVA) can act as a potential modifying additive for acrylate-based LPSCs. This is primarily due to its thermoplastic properties and low glass transition temperature [

12,

13]. Therefore, regardless of the vinyl acetate (VA) content, unlike polymerized acrylates, EVA exhibits plastic deformation upon fracture and does not undergo brittle fracture even at low temperatures. This allows using EVA as a thermoplastic modifier to improve the crack resistance of composite materials and extend the operating temperature range of its products to lower temperatures. Secondly, there are a number of active patent documents [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19] describing the compositions of UV-curable adhesives and coatings based on EVA and acrylate monomers/oligomers. This may indirectly indicate the good solubility of EVA in many acrylates, since, as noted in the cited documents, the developed adhesives and coatings stably cure under irradiation, forming a homogeneous structure. Thirdly, the ability of EVA to form unsaturated double bonds upon heat treatment or exposure to UV radiation was reported in [

13,

20]. It was noted that the longer the treatment, the greater the effect, and the highest results were demonstrated by EVA with a VA content of 40% (EVA40). However, prolonged exposure can lead to the destruction of the copolymer. When acrylate is irradiated in the presence of EVA, the presence of C=C double bonds can lead to their joint crosslinking into a single network, which allows EVA to be used as a crosslinking agent. A number of authors [

13,

21,

22,

23] also point out the reactivity of EVAs, which, under the influence of UV radiation and/or elevated temperatures, exhibit their own polymerization in the presence of peroxide or photoinitiators (PI). Fourth, it has long been known that the viscosity of polymer solutions increases with increasing polymer content. Accordingly, EVA, when dissolved in acrylates, can act as a thickener for photopolymer compositions.

Previously [

24], the influence of several EVAs and low-density polyethylene (LDPE) on diffusion processes occurring in an uncured tBA-based photosensitive mixture was studied across the entire concentration range at different temperatures. Using the example of the diffusion of components in simple binary mixtures of “thermoplastic modifier—photosensitive monomer”, it was found that EVA40 is completely dissolved in tBA at room temperature, and the binary mixture was characterized by the highest interdiffusion coefficient. Therefore, the use of EVA40 as a polyfunctional additive with combined action for tBA-based LPSCs is of interest. The use of this copolymer as a thermoplastic modifier should improve the physicomechanical properties by lowering the glass transition temperature of the composite material. Furthermore, heat-treated EVA40 (m-EVA40) can act as a crosslinking agent due to the presence of C=C double bonds. At the same time, EVA40 is a thickener, which allows for regulating the viscosity of the photosensitive composition.

In [

24], the fundamental basis necessary for the creation of photosensitive compositions modified with a thermoplastic for photopolymerization-based 3D printing methods was laid. The aim of this work is to evaluate the potential of m-EVA40 as both a thermoplastic modifier and a crosslinking additive in tBA-based photosensitive compositions for 3D printing.

3. Results and Discussion

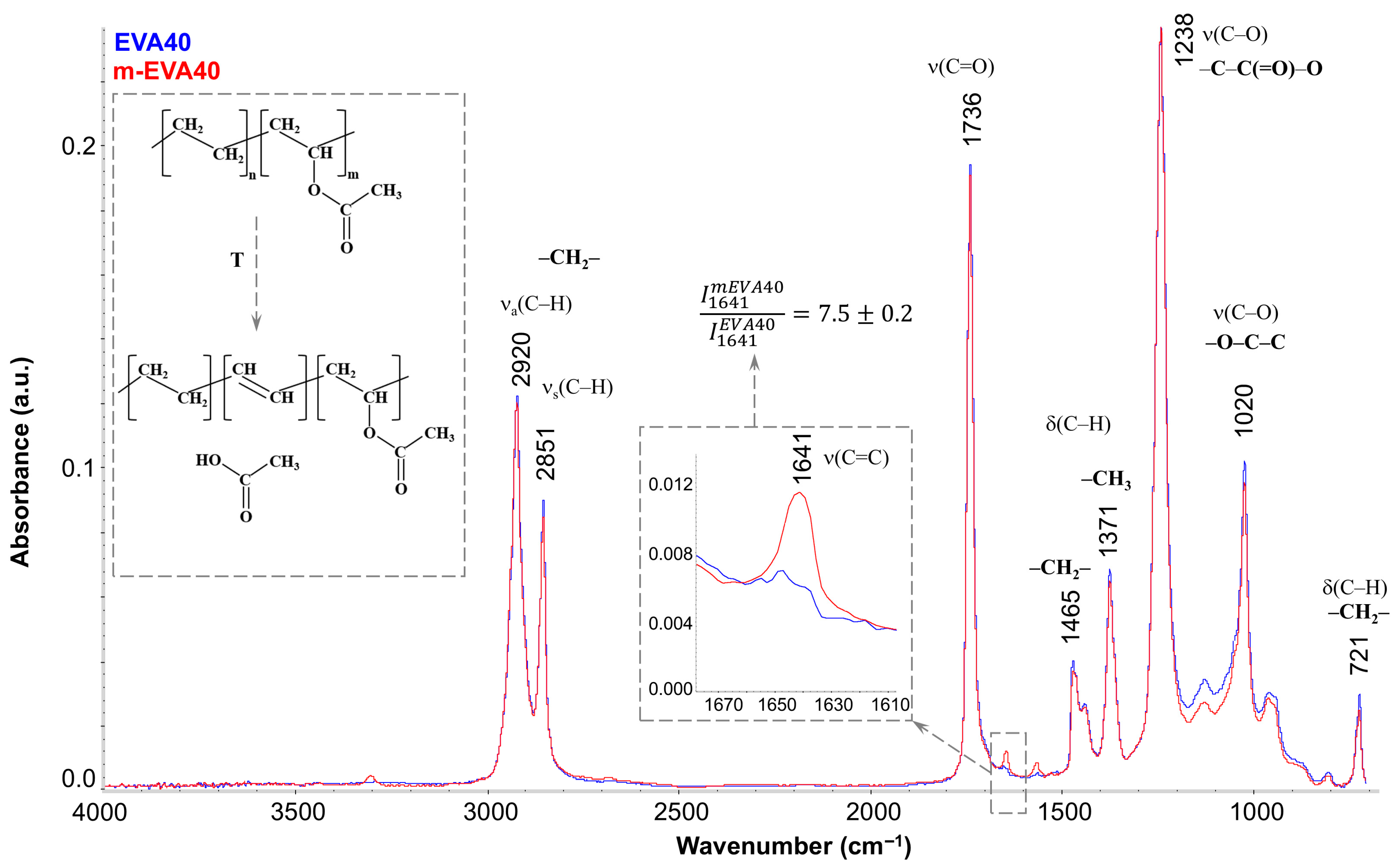

Figure 3 shows the FTIR spectra of EVA40 (blue spectrum) and m-EVA40 (red spectrum). It is seen that they have a standard appearance for the IR spectra of EVAs [

34,

35] and are characterized by the presence of the main absorption bands associated with the C–H stretching vibrations in the region of 3000–2800 cm

−1, stretching vibrations of the carbonyl group C=O at 1736 cm

−1, and the stretching vibrations of C–O in the –C–C(=O)–O and –O–C–C groups (1238 and 1020 cm

−1, respectively), as well as with the deformation vibrations of these groups. The only difference between the spectra of EVA40 and m-EVA40 is the presence of a noticeable low-intensity peak at 1641 cm

−1 in the latter (separately enlarged in the inset of

Figure 3). Quantitative analysis showed that the intensity of this peak increases more than sevenfold for m-EVA40. The presence of absorption peaks in this region has been recorded for EVAs before [

13,

36], and their intensity increases noticeably with increasing VA content in EVA. Opinions are divided regarding the nature of this peak. Some authors [

36] stated that there is a redistribution of the electron cloud in the VA group and the formation of stable hydrogen bonds between the oxygen of the carbonyl group and the hydrogen of the –CH

2– group in the main hydrocarbon chain. Indeed, absorption peaks associated with deformation vibrations of hydroxyl groups and hydrogen bonds may appear in the 1600–1500 cm

−1 region, but this requires the presence of noticeable absorption peaks in the region of stretching vibrations of –OH groups in the 3600–3100 cm

−1 region. Other authors, under a number of conditions (exposure to elevated temperature, UV radiation, etc.) [

13,

37], recorded the splitting off of the entire VA group and the formation of a double bond between the carbons of the main chain. In this case, the absorption band at 1641 cm

−1 coincides well with the absorption region of C=C bonds. The confirmation of the formation of a C=C double bond with the elimination of CH

3COOH (the conventional scheme is shown in the inset in

Figure 3) is supported by the fact that during the heat treatment of EVA a slight smell of acetic acid is felt, and a slight decrease in the intensity of the 1736 cm

−1 band (i.e., a decrease in the content of carbonyl groups) is observed in the IR spectrum, as well as a decrease in the intensity of the 1020 cm

−1 peak and a general decrease in the intensity in the range of 1150–950 cm

−1. It should be noted that this process is not spontaneous in nature, with a complete replacement of the VA monomer units, but only complicates the structure of the copolymer, in which, in addition to ethylene or VA fragments, C=C double bonds are added.

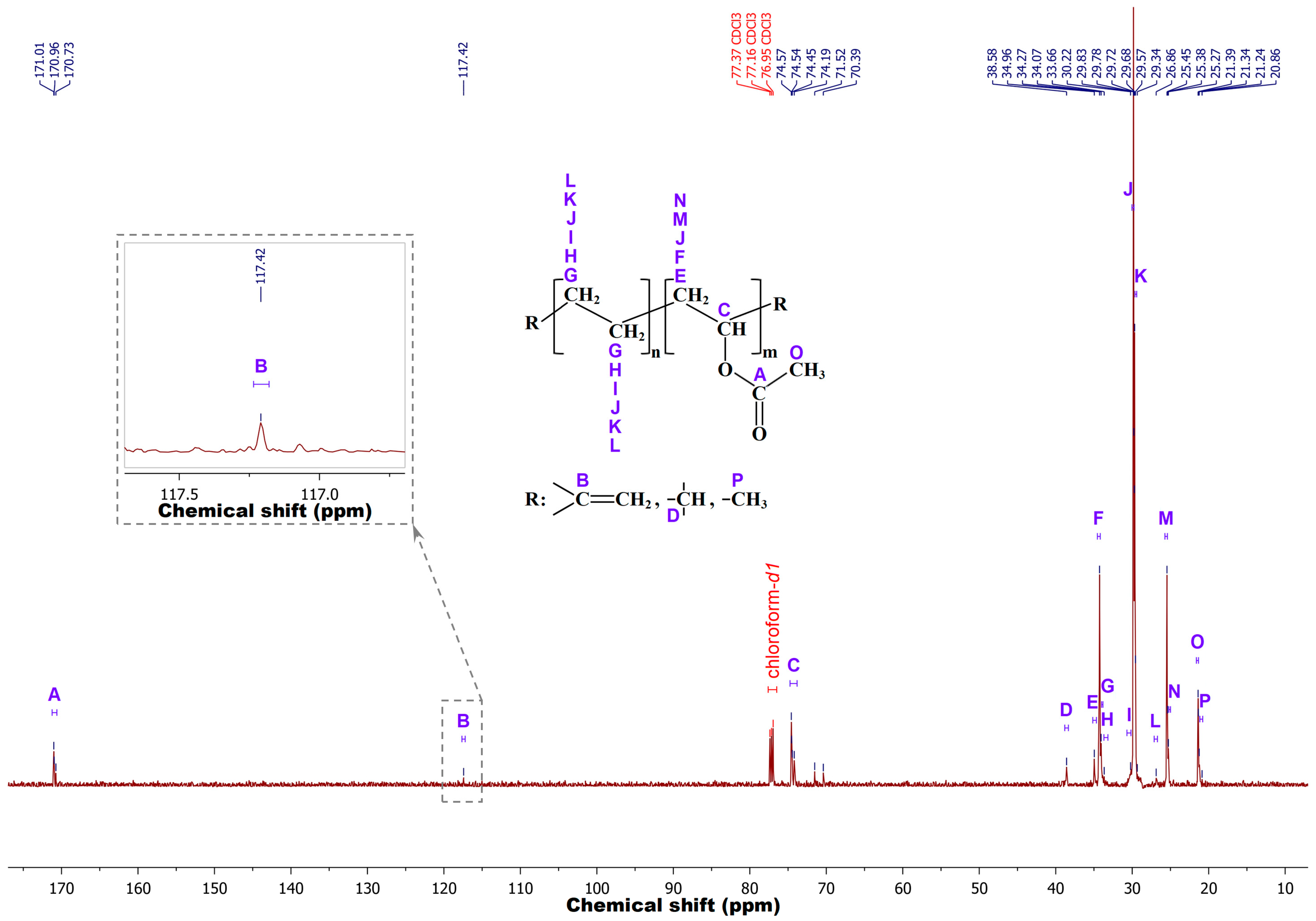

To confirm the results obtained by FTIR spectroscopy, the chemical structure of m-EVA40 was additionally investigated by liquid NMR spectroscopy. Preliminary analysis was performed by proton magnetic resonance to record the

1H-NMR spectrum. However, the data obtained are not indicative, since, due to the high number of –CH

2– groups in the chemical structure of EVA, the dynamic range of the NMR spectrometer is reached very quickly and the low-intensity signal from hydrogen at the double bond either does not have time to be recorded or is blurred against the background of other signals, turning into noise, or merges into a single peak with the CH–O– fragment of the VA unit. In this regard,

13C-NMR is advisable for better resolution.

Figure 4 shows a typical

13C-NMR spectrum recorded for the m-EVA40 sample in chloroform-

d1 at room temperature. The spectral line sequences according to [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29] are as follows (solvent signals are omitted)—

13C-NMR (150.9 MHz, Chloroform-

d1,

δ in ppm): 171.01–170.73 (A), 117.42 (B), 74.57–74.19 (C), 71.52 (false positive), 70.39 (false positive), 38.58 (D), 34.96 (E), 34.27 (F), 34.07 (G), 33.66 (H), 30.22 (I), 29.83–29.78 (J), 29.72–29.57 (K), 29.34 (false positive), 26.86 (L), 25.45–25.38 (M), 25.27 (N), 21.39–21.34 (O), and 21.24–20.86 (P). It is evident that in m-EVA40, in addition to the main ethylene and VA groups, there are branches at the methine point (signal D) and methyl groups –CH

3 (signal P). The methyl group is probably the terminal functional group in this copolymer, as shown in the work [

25]. There are resonance signals related to carbon at the C=C bond (signal B), indicating the presence of C=C bonds in m-EVA40. The experimental data obtained by the liquid NMR spectroscopy method correlate with FTIR spectroscopy results.

Thus, both spectroscopic methods confirm the formation of unsaturated C=C double bonds at the site of the VA monomer unit along the EVA40 chain after a short thermal treatment due to the elimination of acetic acid [

13,

20]. Based on the obtained results, as well as after analyzing a number of works [

13,

21,

22,

23], it can be concluded that m-EVA40 is potentially capable of crosslinking with the tBA monomer to form a three-dimensional spatial network of chemical bonds. This can occur due to the opening of the C=C bond after the attack of active particles of decomposed PI (BAPO in our case) to form the corresponding active center [

7,

13]. Consequently, m-EVA40 in this case should have a certain effect on the kinetics of photopolymerization and rheokinetics of photocuring of modified MPSCs.

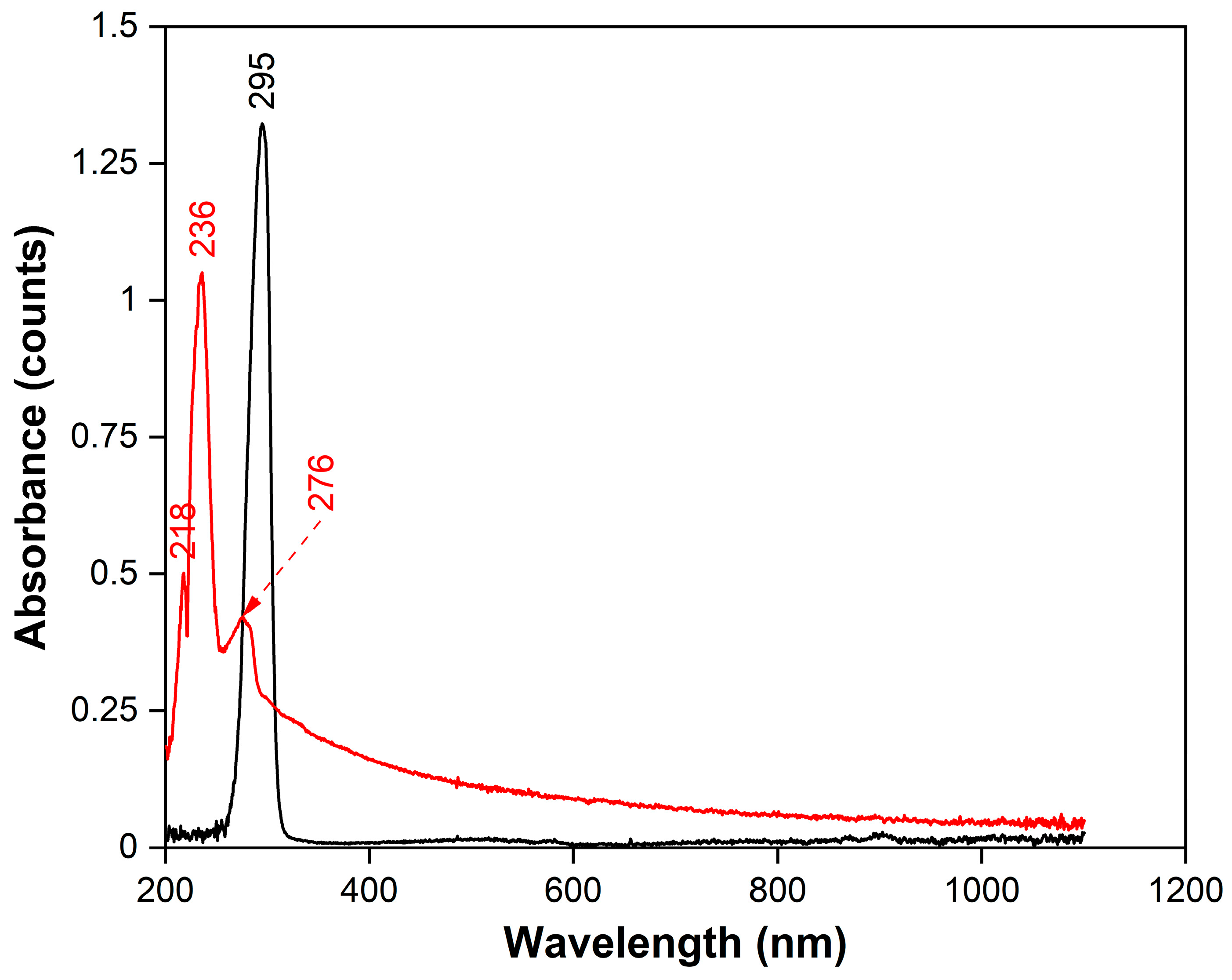

To obtain information on the absorption of radiation in the UV−Vis range, continuous absorption spectra were recorded for tBA and m-EVA40 by spectrophotometry (

Figure 5). It is evident that tBA (black spectrum) has only one absorption peak in the range of 200–400 nm, with a maximum at 295 nm. It is associated with the presence of the H

2C=CH– group in the monomer molecule and its interaction with the spectrophotometer radiation, namely with the process of absorption of photons of the corresponding frequency. In the case of m-EVA40 (red spectrum), due to its complex chemical structure, a fairly wide absorption zone is observed in the spectrum, the largest part of which is within 200–500 nm. At the same time, three peaks are recorded in the UVB range, with maxima at 218, 236, and 276 nm, respectively. These observations also confirm the appearance of a C=C double bond in m-EVA40, since the electronic absorption spectra of substances with C=C bonds usually have absorption maxima in the range of 180−240 nm. It should be noted that the absorption range of tBA does not overlap with the effective absorption region of BAPO, which, according to [

38], is in the region of 325–450 nm. Similarly, m-EVA40, according to [

2] and spectrophotometry data, does not exhibit strong absorption in this region and does not affect the photoinitiation process of BAPO. Therefore, it is rational to use BAPO as a PI for modified MPSCs.

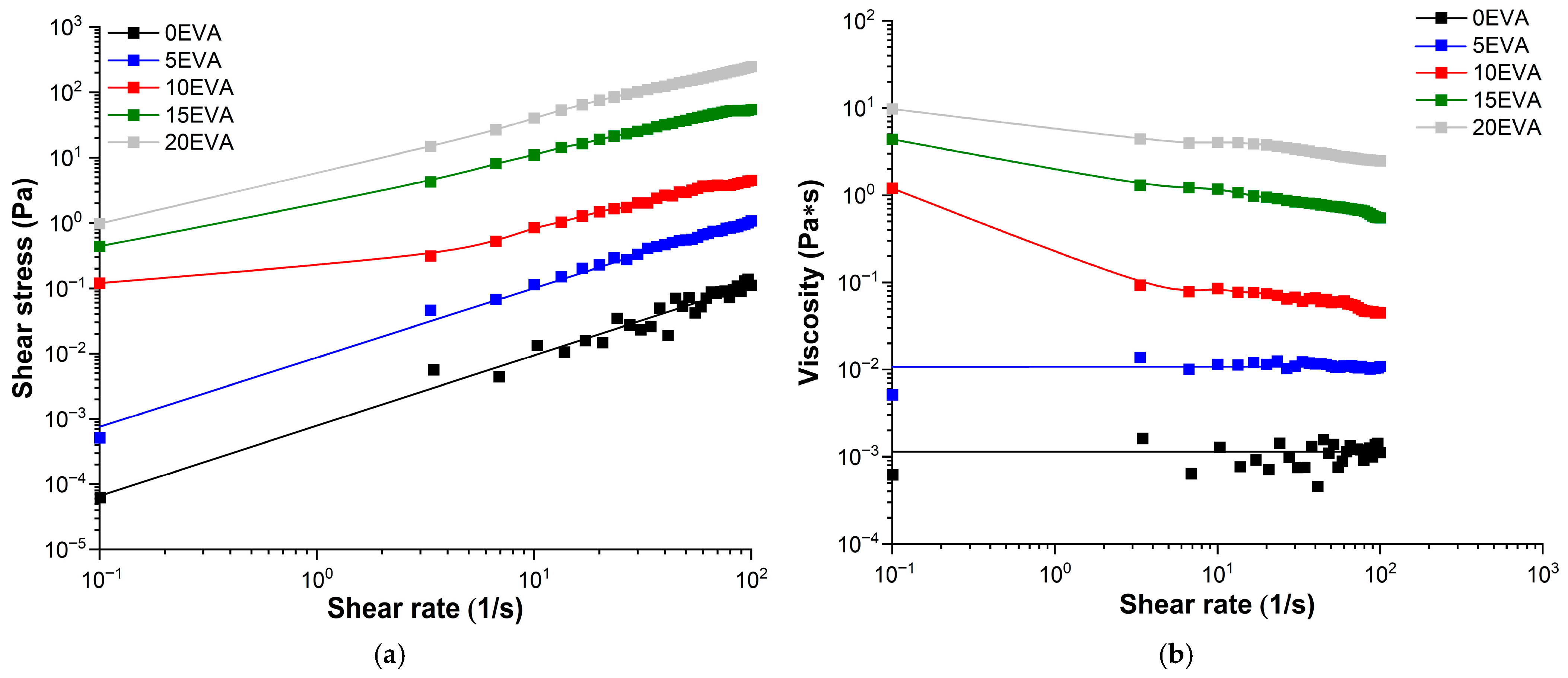

Based on the results of the rheological study, the flow and viscosity curves (rheograms) were obtained for all the prepared MPSCs (

Figure 6a,b, respectively). The introduction of m-EVA40 into MPSCs leads to an increase in the

η value in the range of

= 0.1–100 s

−1. Moreover, the addition of m-EVA40 in an amount of 10 mass. p. or more leads to a sharp increase in the dynamic viscosity and a change in the nature of the system flow from Newtonian to pseudoplastic in the studied range of shear rates [

30]. In the absence of intermolecular interactions between the components in the modified MPSCs in the uncured state in polymer solutions at a certain concentration, the macromolecular chains form loops and chaotically entangle with each other, forming a fluctuation network of entanglements. At low polymer concentrations, individual macromolecules practically do not interact with each other, i.e., at a concentration of m-EVA40 < 10 mass. p. MPSC has a relatively low viscosity and shows Newtonian flow. With an increase in the modifier concentration, the entanglement and interweaving of macromolecular chains dissolved in tBA increase. And at a certain concentration of m-EVA40, a state with an irregular internal order arises, which is characterized by high viscosity at rest or under low shear stress. When the shear rate is increased to a value where the disorienting influence of chaotic Brownian motion is overcome, the macromolecular chains of m-EVA40 in solution unravel, stretch, and orient in the direction of the driving force. As a result of the orientation, an asymptotic decrease in viscosity is observed to a certain constant value—the “lowest Newtonian” viscosity [

30].

Based on the rheometry results, the rheological behavior of MPSC with a content of

Сm-EVA40 < 10 mass. p. in the composition obeys Newton’s law of viscous friction (Equation (7)), and with

Сm-EVA40 ≥ 10 mass. p., as it is described by the Ostwald–de Waele power law (Equation (8)) [

30]:

where

k is the consistency index related to viscosity, [Pa∙s

n];

n is the anomaly index (power index of nonlinearity).

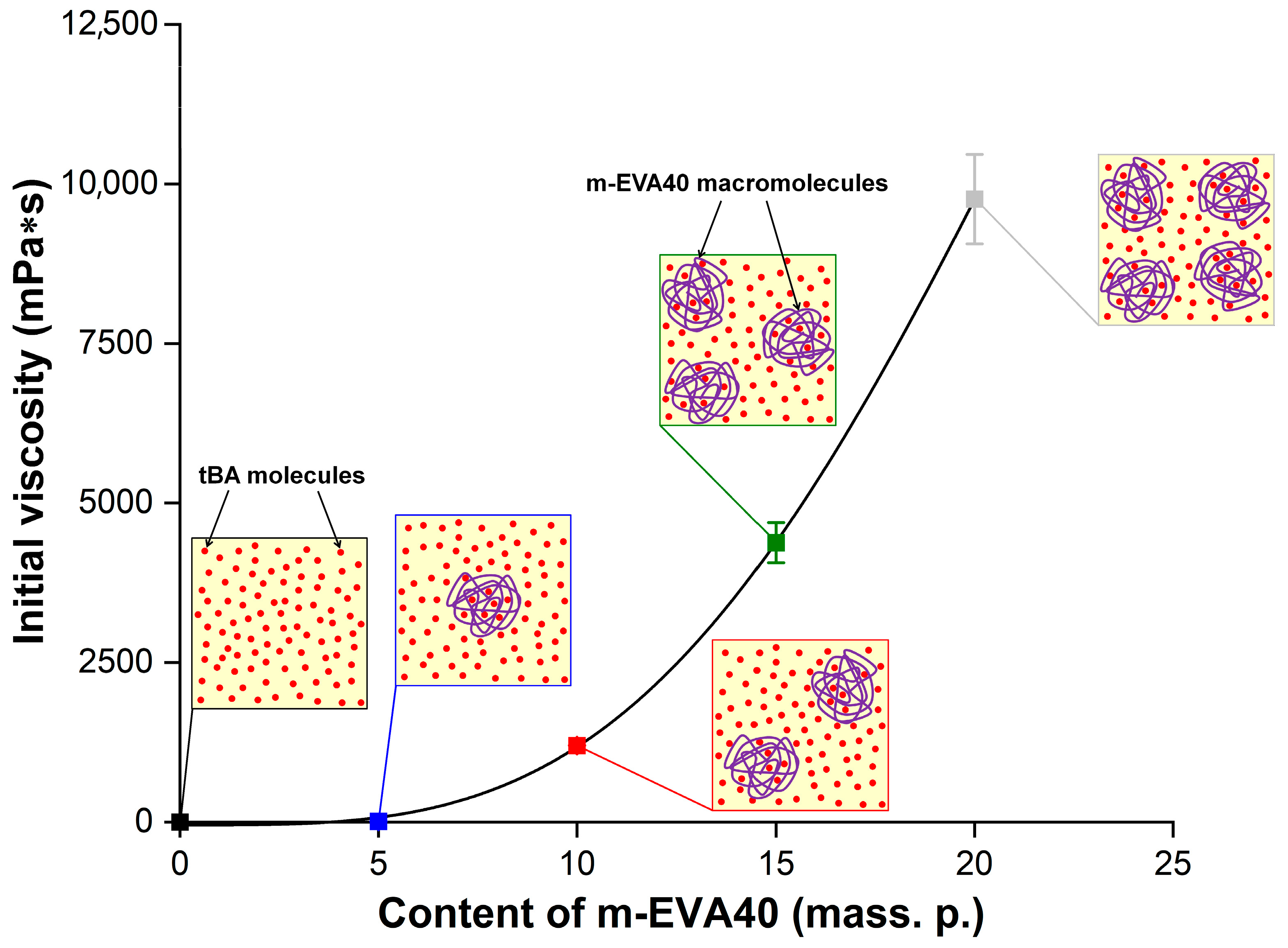

The concentration dependence of the dynamic viscosity for MPSC at

= 0.1 s

−1 (

η0.1) is shown in

Figure 7, with a schematic illustration of the supramolecular structure described above. The obtained dependence of

η0.1 as a function of

Сm-EVA40.

Table 3 contains the experimental values of

η0.1 and the initial shear stress at

= 0.1 s

−1 (

τ0.1) for all MPSCs, as well as the parameters from Equations (7) and (8). It is evident that, compared to the unmodified MPSC, the modified system contains 20 mass. p. m-EVA40 and has a

η0.1 value that is almost four decimal orders of magnitude higher. It should be noted that the dependence on

η0.1(

CEVA-40) is nonlinear. Introduction to MPSC 10 mass. p. and more thermoplastic modifier leads to a sharp rise in the curve.

Based on the conducted rheological study, it can be concluded that the introduction of m-EVA40 into the initial tBA-based LPSC allows an increase in its viscosity to the required level. Several publications [

3,

8,

10] report that the viscosity of photosensitive compositions used in classical photopolymerization-based 3D printing methods should be at a level of 0.1 to 10 Pa·s. Thus, it can be argued that m-EVA40 acts as a thickener for MPSC and the introduction of this copolymer in an amount of 10–20 mass. p. allows an increase in the processability of the original system, as well as using it in photopolymerization-based 3D printing.

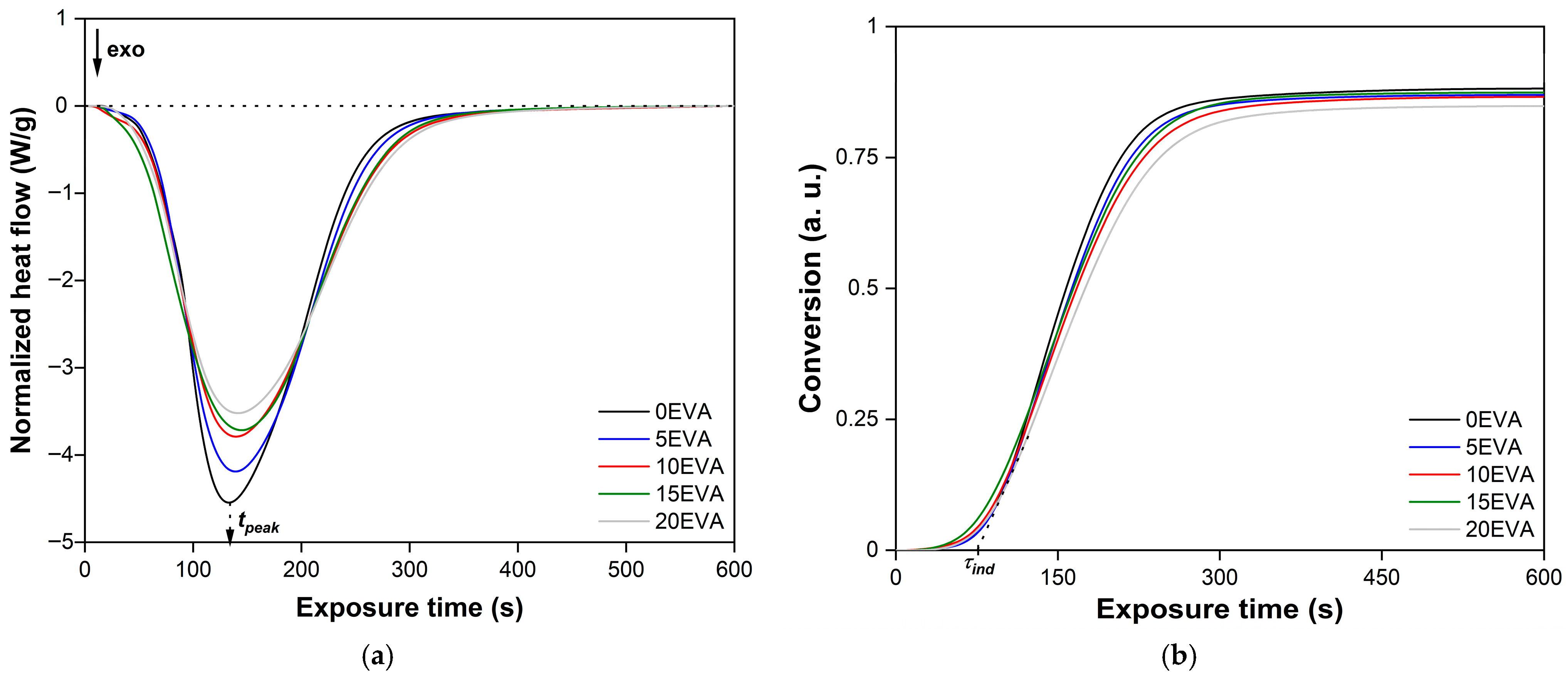

Figure 8 shows typical Photo-DSC isotherms of the photopolymerization process of the initial and modified MPSCs. It is evident that even with an m-EVA40 content of 20 mass. p. the system exhibits a stable photochemical polymerization reaction. The initial stage of photopolymerization of all MPSCs is characterized by an induction period (

τind). After ~85 s, a sharp increase in the rate of the chemical reaction is observed on all isotherms, which was called the Trommsdorff–Norrish effect or the “gel effect” [

31,

32]. During the chemical reaction of photopolymerization, an exponential decrease in the heat flow from the reaction zone occurs, forming an extremum on the obtained curves, which is estimated as the time to reach the exothermic peak (

τpeak). As a result, all curves reach a plateau within ~570 s after the start of irradiation, which is a sign of completion of the photochemical polymerization reaction corresponding to MPSC [

31,

32]. These observations are consistent with the results of studying the curing process of various acrylates and systems based on them [

6,

7,

11,

32,

33]. The slowdown in the photopolymerization rate after reaching the peak value is explained by the fact that in MPSCs, viscosity increases over time during curing, the molecular weight increases, and gelation occurs. All this leads to a decrease in the mobility and a decrease in the diffusion of all components of the system, including reactive ones. Consequently, the rate of the photochemical polymerization reaction also decreases. In addition, the gradual consumption of C=C bonds, a decrease in the efficiency of BAPO as a result of photodegradation, and vitrification of the system at a later stage of the chemical reaction also contribute to a decrease in the photopolymerization rate until it stops. Another factor is associated with an increase in the glass transition temperature (

Tg) of the polymer formed during the reaction, which leads to vitrification of the corresponding MPSC as soon as

Tg exceeds the experimental temperature [

5,

6,

7,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33]. In the case of modified MPSCs, the rate of photochemical polymerization reaction is additionally affected by phenomena that may be related to the absorption and scattering of the lamp radiation from the attachment on the macromolecules of the thermoplastic modifier [

5,

11]. Based on the analysis of isotherms in

α—

texpos coordinates, integral kinetic curves of the photopolymerization process of the studied MPSCs were constructed (

Figure 8b). It is evident that all curves have a classical S-shaped character [

32]. The

α(

texpos) dependences clearly show

τind and the inflection point corresponding to the maximum on the corresponding isotherm. These observations are an indication of the occurrence of an autocatalytic chemical reaction, which correlates with the results of studying the photopolymerization of other acrylate-based systems [

6,

7,

11,

32,

33].

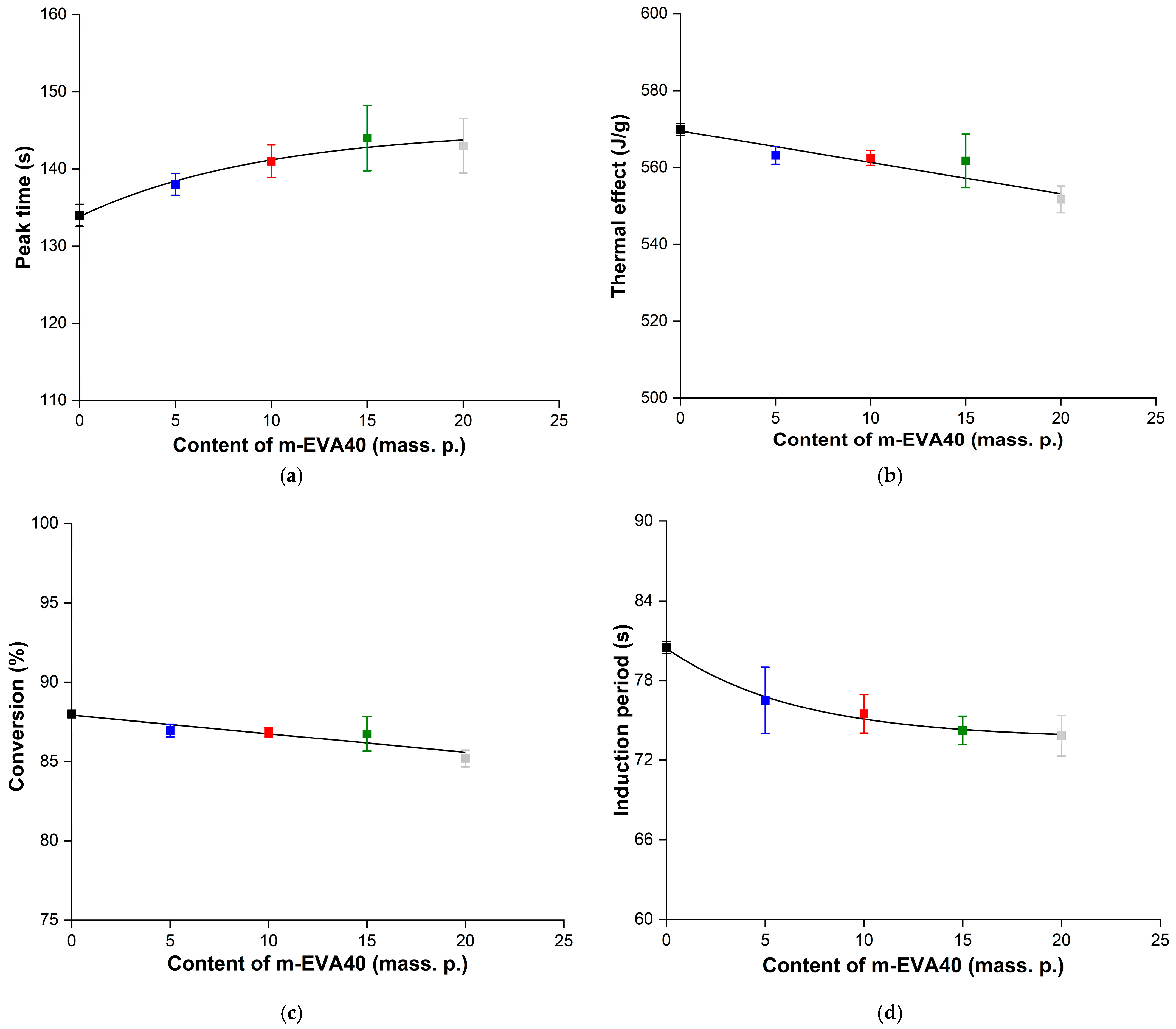

Figure 9a,b shows the dependence of the

τpeak and

Qexp values as functions of

Cm-EVA40, respectively. It is evident that the addition of m-EVA40 to the initial system results in a slight increase in

τpeak, while the dependence of

τpeak(

Cm-EVA40) is nonlinear and is described by a “saturation curve”. With an increase in the content of the thermoplastic modifier, a linear decrease in the experimental value of

Qexp is also observed. Apparently, both facts indicate a slowdown in the autoacceleration of the ongoing photochemical polymerization reaction with an increase in the concentration of m-EVA40 in MPSCs. This can be explained by the fact that m-EVA40 macromolecules dissolved in the tBA monomer have a branched structure and are characterized by fairly large sizes [

26] relative to the radicals and active centers formed from BAPO and then tBA at the stages of initiation and initial chain growth. In addition, as has already been said earlier, at a certain concentration of m-EVA40, a fluctuation network of entanglements arises in the system, leading to a sharp increase in the initial viscosity [

30]. All this can create steric hindrances for the movement and diffusion of reactive particles in the volume of MPSC, reducing their mobility at the chain growth stage. At the same time, the thermoplastic modifier can contribute to the weakening of the intensity of incident radiation as a result of partial light absorption and/or light scattering on dissolved macromolecules [

4,

5,

11,

39]. In addition, in curing systems modified with thermoplastics, during the chemical reaction, it is possible to form heterogeneous structures at the interphase boundaries, where light scattering also occurs [

40]. Therefore, despite the potential reactivity of m-EVA40 due to the presence of C=C double bonds in its chemical structure, in general, there is a decrease in the rate of the photochemical reaction of polymerization of modified MPSCs. The amount of heat released from the reaction zone also decreases, and the degree of conversion of the system drops.

Figure 9c,d shows, respectively, the dependences of the

α and

τind values as the corresponding functions of

Cm-EVA40. It is evident that with the increase in m-EVA40 concentration from 0 to 20 mass. p. in MPSCs, there is a tendency to some decrease in both the degree of conversion and the induction period. The explanation for this was given above.

Table 4 summarizes the results of the analysis of Photo-DSC isotherms and integral kinetic curves of the photopolymerization process of the studied MPSCs, and also provides the calculated values of the key parameters. All presented data were statistically processed, and the coefficient of variation does not exceed 3%.

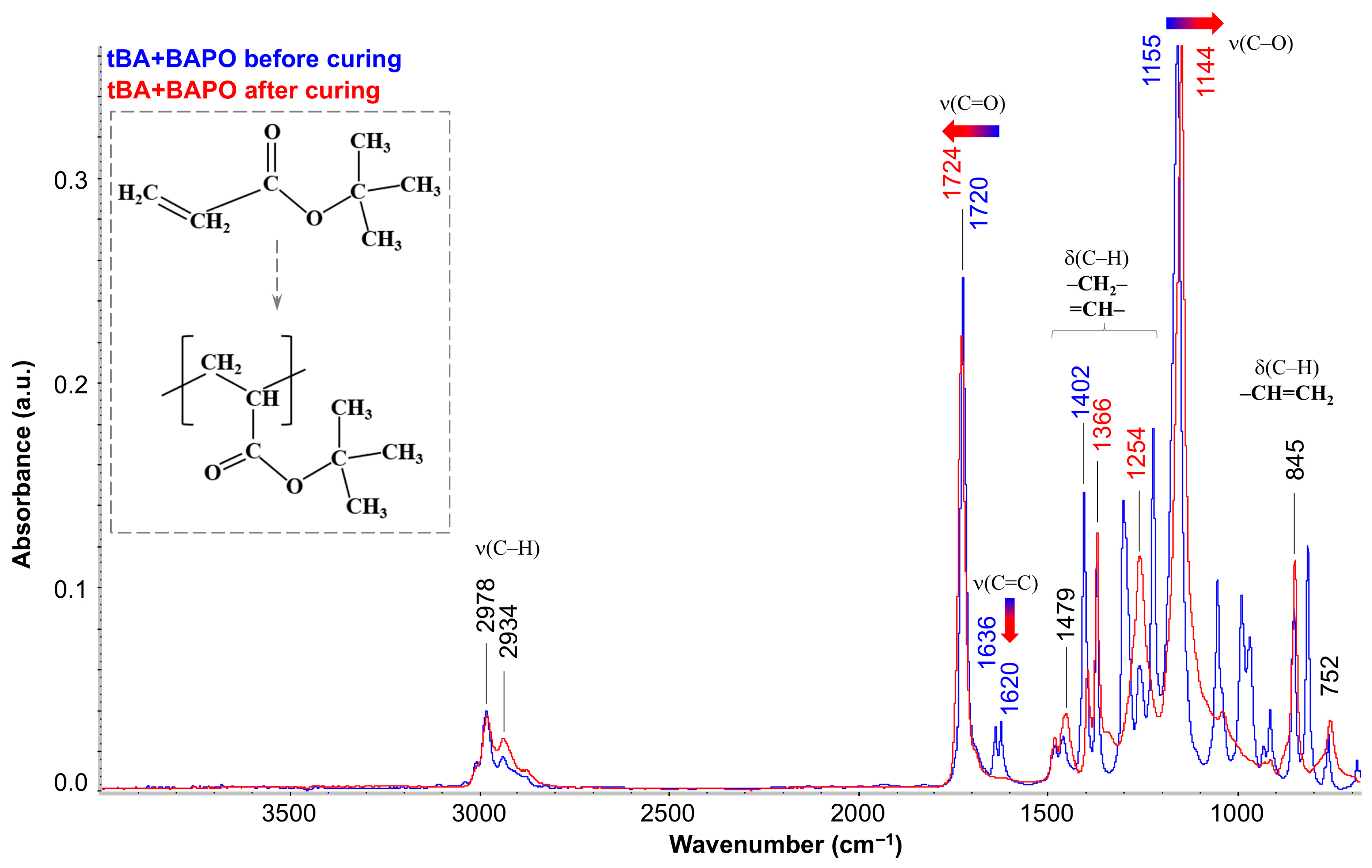

Figure 10 shows the FTIR spectra for tBA with BAPO before and after photopolymerization (blue and red spectra, respectively). It should be noted that in the preliminary experiment, the spectra of tBA were obtained and analyzed both without PI and in its presence. This experiment showed that adding 1 mass. p. BAPO to the monomer does not lead to noticeable changes in the spectrum, and, therefore, the presented spectrum for tBA + BAPO completely corresponds to the spectrum of pure tBA and shows absorption bands characteristic of it. The most intense of them are the peaks at 1720 cm

−1 (stretching vibrations of the carbonyl group C=O) and 1155 cm

−1 (stretching vibrations of the C–O bond). In addition, absorption bands of both the stretching vibrations of C–H bonds (range 3050–2800 cm

−1) and the deformation vibrations of various groups (1450–1200 cm

−1 and 1100–700 cm

−1) can be observed. It is important to emphasize that at 1636 and 1620 cm

−1 there is a characteristic double peak associated with the presence of a C=C double bond at the end of the initial monomer. After curing (transition from blue to red spectrum), the peaks of double bonds in poly-tBA completely degenerate (shown by the blue–red arrow), indicating complete conversion of the tBA monomer. Quantitative calculation according to the absorption band at 1620 cm

−1 showed that the conversion degree reaches 97%. In addition, a shift in the peak of the C–O stretching vibrations at 1155 cm

−1 to a new position at 1144 cm

−1 (also shown by the arrow) can be observed, and the carbonyl peak also changes slightly and shifts to the left (from 1720 to 1724 cm

−1). These changes in the spectrum are due to the fact that the opening of the acrylate double bonds leads to a change in the spatial arrangement of all neighboring groups. In this case, the intensity of the band at 2934 cm

−1 (stretching vibrations of the –CH

2– group) and 1479 cm

−1 (deformation vibrations of the –CH

2– group) increases, indicating the appearance of a carbon skeleton. At the same time, analysis of the band at 1366 cm

−1, associated with deformation vibrations of the C–CH

3 group, showed that no significant changes in the –CH

3 groups were observed. Also, the absorption bands in the region of 1100–900 cm

−1, which were associated with deformation vibrations of C–H at the C=C double bond, disappear. Thus, it can be stated that during the curing process, the acrylate double bonds in tBA are completely opened to form the main macromolecular chain, where the tert-butyl part, which has changed its spatial position (but not structure), becomes the side group of the resulting linear polymer poly-tBA (the schematic diagram is shown in the inset in

Figure 10).

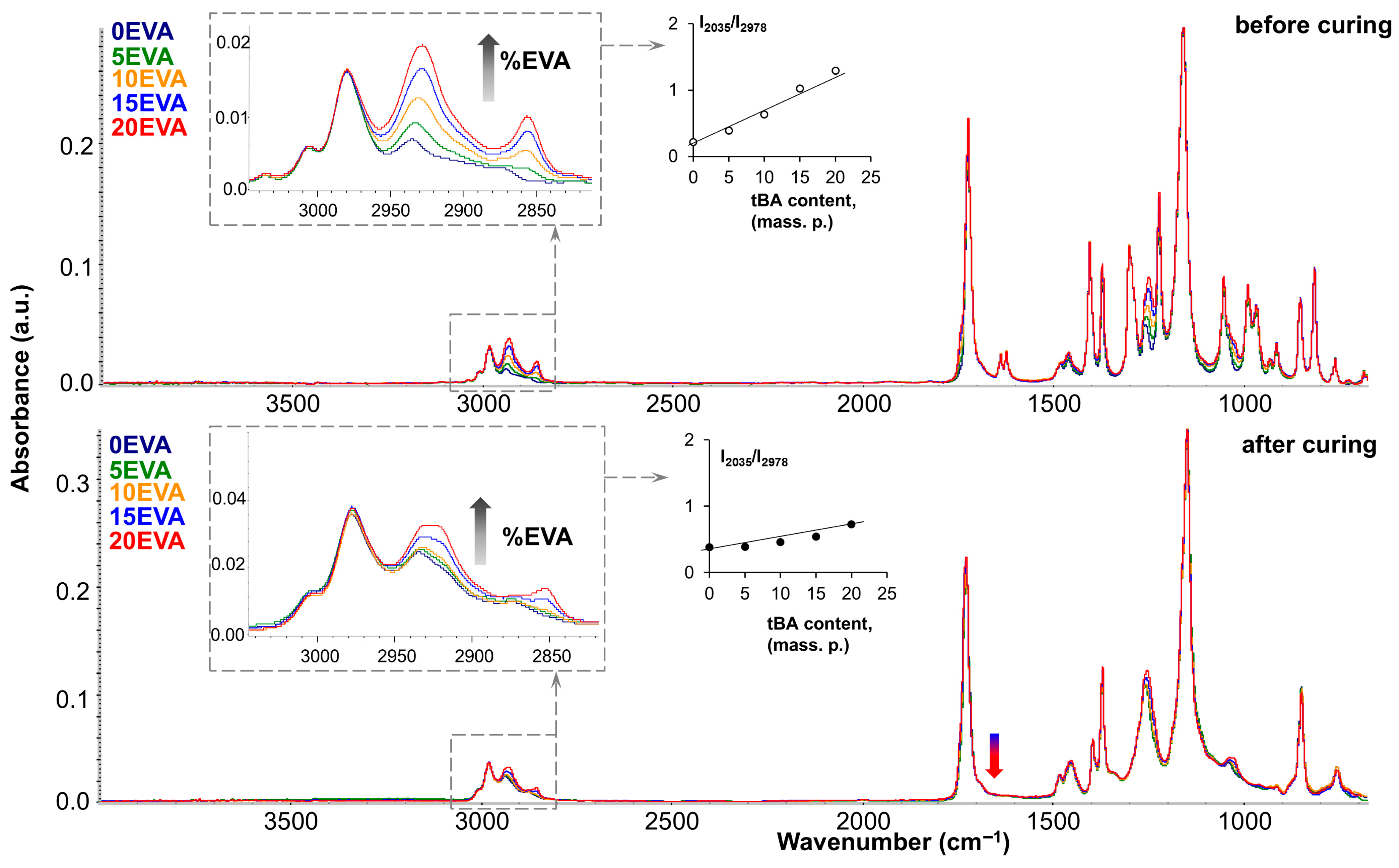

Figure 11 shows the FTIR spectra of the original and modified MPSCs before and after photocuring (top and bottom, respectively). As can be seen, the mixed spectra almost completely correspond to the spectrum of pure tBA monomer (dark blue spectrum). However, the introduction of m-EVA40 can be tracked by the increase in the intensity of such characteristic absorption bands as the stretching vibrations of the –CH

2– group, which appear in the region of 2950–2800 cm

−1. The inset on the left shows that the higher the content of the thermoplastic modifier in the system, the higher the intensity of these absorption peaks in the spectrum. A quantitative analysis of the 2930 cm

−1 band growth was performed, and a plot of its change with increasing m-EVA40 content was plotted (shown in the center of

Figure 11). The linear growth of this absorption band, both before and after curing, indicates that increasing the m-EVA40 content in the mixture does not affect the curing process of tBA. Such an effect can be observed for the absorption band in the region of 1250 cm

−1 (stretching vibrations of C–O in the –C–C(=O)–O group), the intensity of which increases with the increase in the content of m-EVA40 in MPSC, and this peak also tends to shift to the right due to the fact that for pure m-EVA40 its position corresponds to 1238 cm

−1. The carbonyl peak (1730–1720 cm

−1) also increases slightly in intensity and broadens to the left. This is due to the fact that similar absorption bands of the two components (tBA and m-EVA40) in the original spectra have a slightly different position in wavenumber due to the influence of neighboring groups. For example, the carbonyl peak of m-EVA40 is localized at 1736 cm

−1, while for tBA it is at 1720 cm

−1. Accordingly, both peaks appear during mixing, and the corresponding changes in the spectrum can be seen in total. By additionally processing the IR spectra of the initial components tBA and m-EVA40, through their mathematical addition, simulated mixed spectra were obtained, which were completely identical to the experimentally obtained mixed spectra for MPSCs. All this proves that no interactions or transformations occur during the mixing of tBA and m-EVA40. After photocuring, the mixed spectra also differ only in the intensity of the characteristic bands of m-EVA40, as was the case for the mixed spectra before curing. This suggests that m-EVA40 is potentially present before and after curing as an additional component that does not participate in crosslinking. It is important to emphasize that the obtained mixtures were obtained using m-EVA40, which is characterized by the presence of C=C double bonds, and the absorption bands of C=C bonds in the mixed spectra after curing completely disappear (indicated by the blue–red arrow in

Figure 11). This may be the result of the fact that there are too few C=C double bonds in m-EVA40, and its potential participation in copolymerization with tBA does not lead to the formation of a dense network.

The swelling method showed that the cured samples of all MPSCs were completely dissolved in tetrahydrofuran and xylene within 24 h at a room temperature of ~25 °C. This confirmed our assumption based on the FTIR spectroscopy results. Therefore, it is fair to emphasize that the content of formed C=C double bonds after thermal treatment of EVA40 in the specified pressing modes at a concentration of thermoplastic modifier in MPSC up to 20 mass. p. is insufficient to perform crosslinking and form a dense three-dimensional network of chemical bonds.

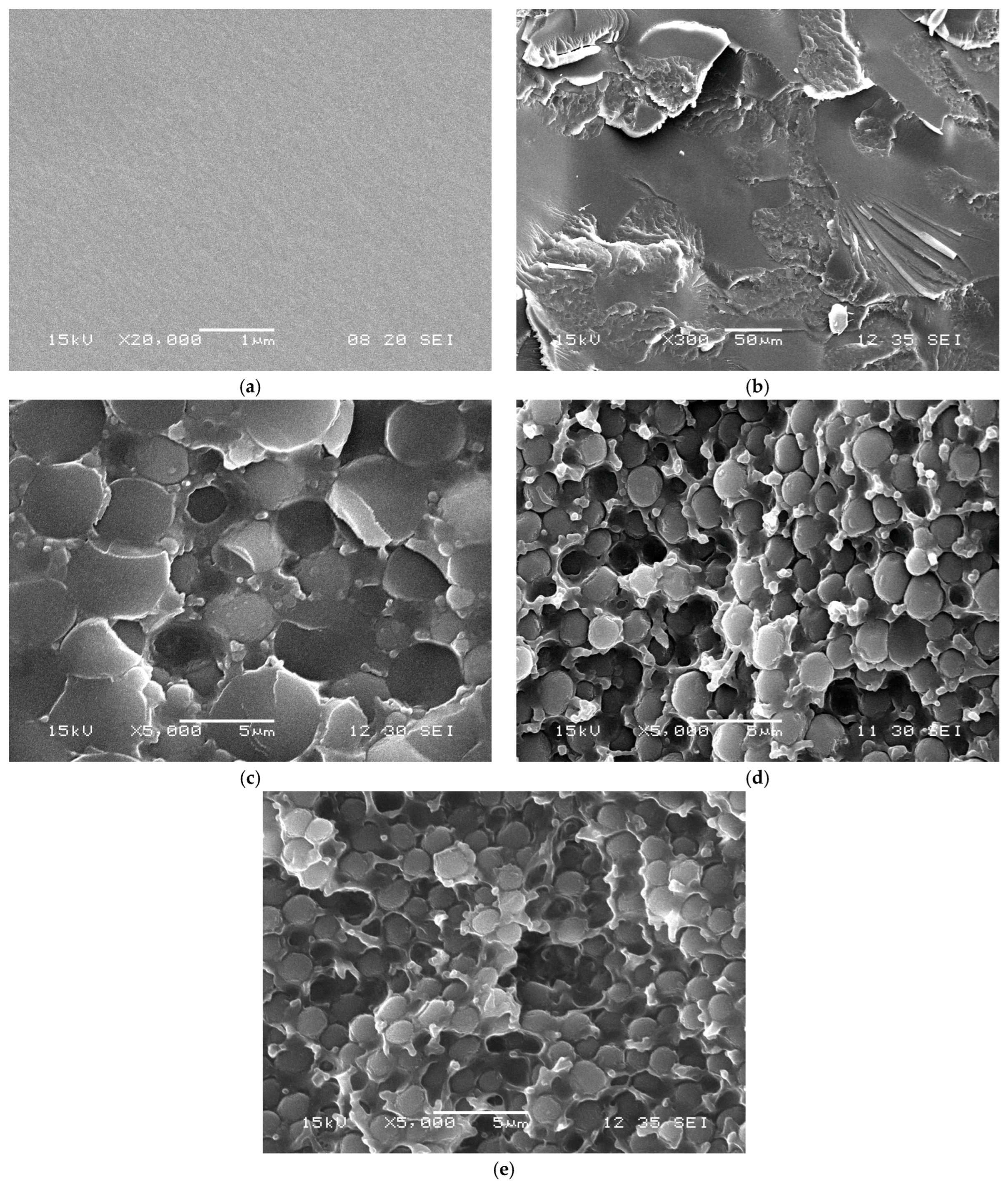

Microscopic studies of the phase structure of the cured compositions are shown in

Figure 12. The SEM images show that the introduction of the modifier leads to the formation of a heterogeneous structure, which confirms the absence of complete incorporation of m-EVA40 into the chemical network with tBA. That is, during photopolymerization, accompanied by an increase in the molecular weight of tBA in a mixture with EVA, there is an increase in viscosity and a decrease in the thermodynamic compatibility of the components, leading to the formation of heterogeneous phase structures in the system. It is evident that the introduction of already 5 mass. p. of the modifier leads to the formation of a structure of the “interpenetrating phases” type, and an increase in the concentration to 10 mass. p. changes the phase organization towards “inverted matrix-dispersion”, where the dispersed phase is enriched with tBA. The conclusion about the phase composition is made on the basis of data on the volume fraction of the dispersed phase and the diffusion mobility of the initial components of the system [

24]. A further increase in the concentration of the components leads to a decrease in the size of the phase particles, which is associated with the onset of phase decomposition at a later stage of the photochemical polymerization reaction [

40].

Thus, studies of the phase structure of the photopolymerized tBA–m-EVA40 system confirm the data presented above. The introduction of m-EVA40 into tBA does not lead to the formation of a spatial network of chemical bonds, i.e., the copolymer does not act as a full-fledged crosslinking agent, but is a thermoplastic modifier and thickener, affecting the operational and technological properties of the material, respectively.

The fundamental focus of the work on studying the possibility of the complex use of the modifying heat-treated additive m-EVA did not include studying the operational properties of photosensitive modified systems, but was determined by the establishment of specific functional interactions between the components during the curing of such systems. Thus, in continuation of this work, a crosslinking agent will be selected, and phase equilibria and structure formation will be investigated during the chemical reaction of photocuring of a tBA-based system modified by EVA, with the study of the influence of the phase structure on the physical and mechanical characteristics of the additive material.