Color Stability of Single-Shade Resin Composites in Direct Restorations: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.4. Selection Process

2.5. Data Collection Process

2.6. Assessment of Study Risk of Bias

2.7. Effect Measures and Synthesis Methods

2.8. Certainty Assessment

3. Results

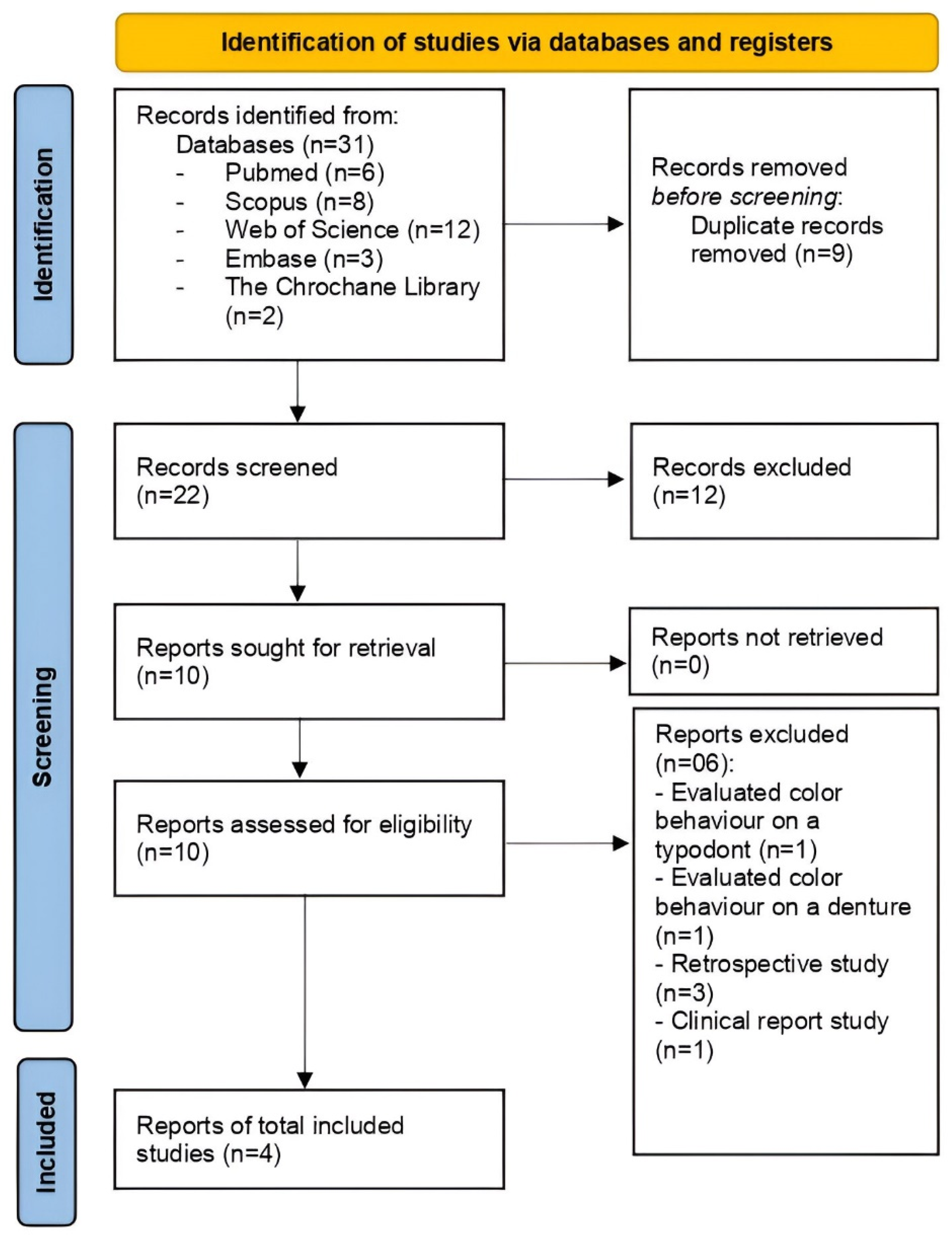

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Risk of Bias in Studies

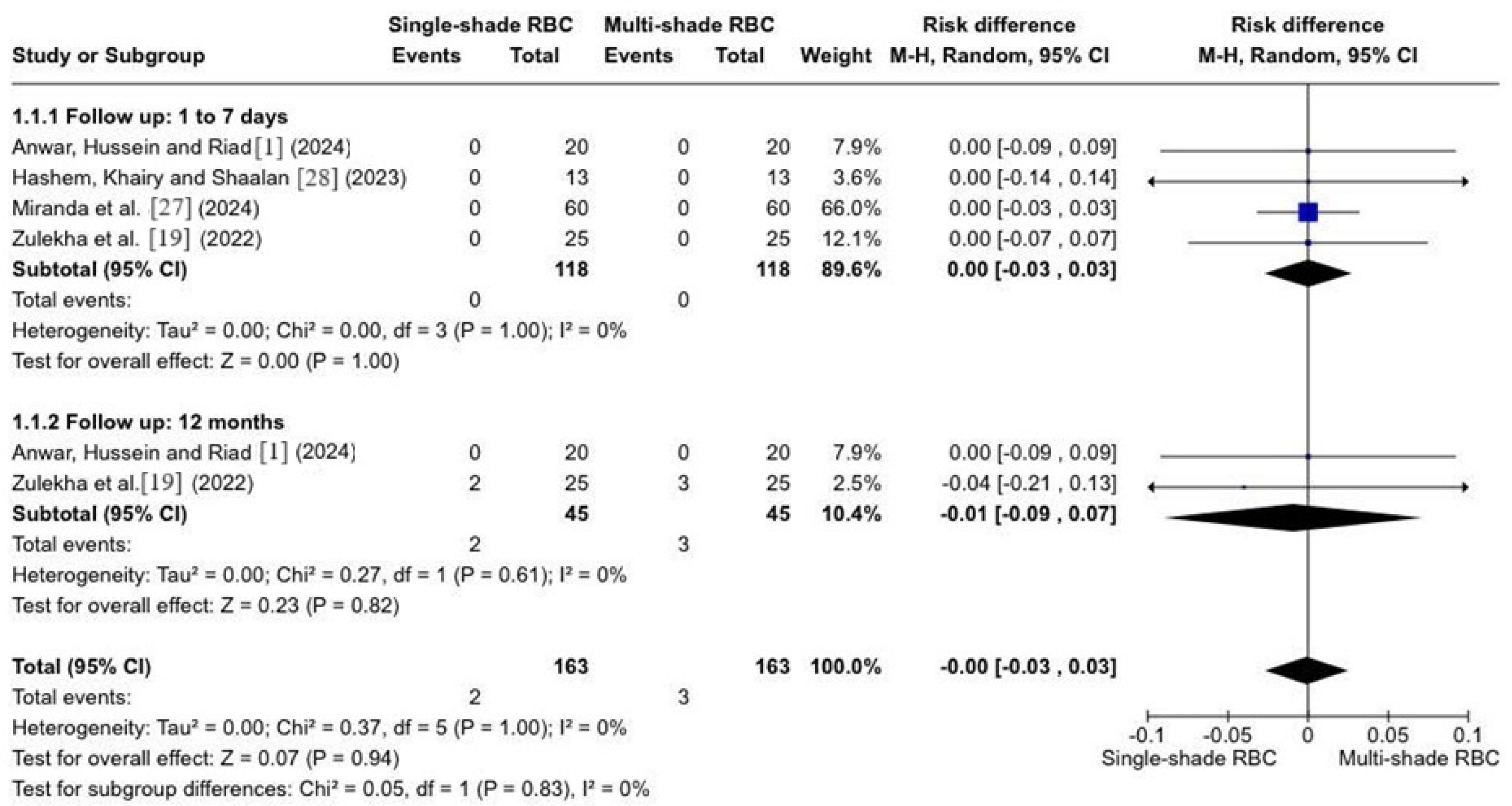

3.4. Results of Syntheses

3.5. Certainty of Evidence

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anwar, R.S.; Hussein, Y.F.; Riad, M. Optical behavior and marginal discoloration of a single shade resin composite with a chameleon effect: A randomized controlled clinical trial. BDJ Open 2024, 10, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barros, M.S.; Silva, P.F.D.; Santana, M.L.C.; Bragança, R.M.F.; Faria-E-Silva, A.L. Background and surrounding colors affect the color blending of a single-shade composite. Braz. Oral Res. 2023, 37, e035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohym, S.; Tawfeek, H.E.M.; Kamh, R. Effect of coffee on color stability and surface roughness of newly introduced single shade resin composite materials. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardan, L.; Bourgi, R.; Cuevas-Suárez, C.E.; Lukomska-Szymanska, M.; Monjarás-Ávila, A.J.; Zarow, M.; Jakubowicz, N.; Jorquera, G.; Ashi, T.; Mancino, D.; et al. Novel Trends in Dental Color Match Using Different Shade Selection Methods: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Materials 2022, 8, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oivanen, M.; Keulemans, F.; Garoushi, S.; Vallittu, P.K.; Lassila, L. The effect of refractive index of fillers and polymer matrix on translucency and color matching of dental resin composite. Biomater. Investig. Dent. 2021, 8, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz da Silva, E.T.; Charamba Leal, C.F.; Miranda, S.B.; Evangelista Santos, M.; Saeger Meireles, S.; Maciel de Andrade, A.K.; Japiassú Resende Montes, M.A. Evaluation of Single-Shade Composite Resin Color Matching on Extracted Human Teeth. Sci. World J. 2023, 2023, 4376545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouhar, R.; Ahmed, N.; Ahmed, M.A.; Faheemuddin, M.; Mosaddad, S.A.; Heboyan, A. Smile aesthetics in Pakistani population: Dentist preferences and perceptions of anterior teeth proportion and harmony. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.A.; Jouhar, R.; Khurshid, Z. Smart Monochromatic Composite: A Literature Review. Int. J. Dent. 2022, 2022, 2445394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paolone, G.; Formiga, S.; De Palma, F.; Abbruzzese, L.; Chirico, L.; Scolavino, S.; Goracci, C.; Cantatore, G.; Vichi, A. Color stability of resin-based composites: Staining procedures with liquids-A narrative review. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2022, 34, 865–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demarco, F.F.; Collares, K.; Correa, M.B.; Cenci, M.S.; Moraes, R.R.; Opdam, N.J. Should my composite restorations last forever? Why are they failing? Braz. Oral Res. 2017, 31, e56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, I.R.; Özcan, M. Reparative Dentistry: Possibilities and Limitations. Curr. Oral Health Rep. 2018, 5, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altınışık, H.; Özyurt, E. Instrumental and visual evaluation of the color adjustment potential of different single-shade resin composites to human teeth of various shades. Clin. Oral Investig. 2023, 27, 889–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cubukcu, I.; Gundogdu, I.; Gul, P. Color match analysis of single-shade and multishade composite resins using spectrophotometric and visual methods after bleaching. Dent. Mater. J. 2023, 42, 826–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korkut, B.; Türkmen, C. Longevity of direct diastema closure and recontouring restorations with resin composites in maxillary anterior teeth: A 4-year clinical evaluation. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2023, 33, 590–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosa, E.D.A.R.; Silva, L.F.V.D.; Silva, P.F.D.; Silva, A.L.F.E. Color matching and color recovery in large composite restorations using single-shade or universal composites. Braz. Dent. J. 2024, 35, e245665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamashita, A.; Kobayashi, S.; Furusawa, K.; Tichy, A.; Oguro, R.; Hosaka, K.; Shimada, Y.; Nakajima, M. Does the thickness of universal-shade composites affect the ability to reflect the color of background dentin? Dent. Mater. J. 2023, 42, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ersöz, B.; Karaoğlanoğlu, S.; Oktay, E.A.; Aydin, N. Resistance of Single-shade Composites to Discoloration. Oper. Dent. 2022, 47, 686–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Zhu, J.; Yu, M.; Jin, C.; Huang, C. Effect of aging and bleaching on the color stability and surface roughness of a recently introduced single-shade composite resin. J. Dent. 2024, 143, 104917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulekha; Vinay, C.; Uloopi, K.S.; RojaRamya, K.S.; Penmatsa, C.; Ramesh, M.V. Clinical performance of one shade universal composite resin and nanohybrid composite resin as full coronal esthetic restorations in primary maxillary incisors: A randomized controlled trial. J. Indian Soc. Pedod. Prev. Dent. 2022, 40, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2019, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolone, G.; Mazzitelli, C.; Josic, U.; Scotti, N.; Gherlone, E.; Cantatore, G.; Breschi, L. Modeling Liquids and Resin-Based Dental Composite Materials—A Scoping Review. Materials 2022, 15, 3759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rauber, G.B.; Bernardon, J.K.; Vieira, L.C.C.; Baratieri, L.N. Evaluation of a technique for color correction in restoring anterior teeth. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2017, 29, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Abreu, J.L.B.; Sampaio, C.S.; Benalcázar Jalkh, E.B.; Hirata, R. Analysis of the color matching of universal resin composites in anterior restorations. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2021, 33, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korkut, B.; Özcan, M. Longevity of Direct Resin Composite Restorations in Maxillary Anterior Crown Fractures: A 4-year Clinical Evaluation. Oper. Dent. 2022, 47, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korkut, B.; Ünal, T.; Can, E. Two-year retrospective evaluation of monoshade universal composites in direct veneer and diastema closure restorations. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2022, 35, 525–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero, M.F. Esthetic anterior composite resin restorations using a single shade: Step-by-step technique. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2015, 114, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miranda, A.O.; Favoreto, M.W.; Matos, T.P.; Castro, A.S.; Kunz, P.V.; Souza, J.L.; Carvalho, P.; Reis, A.; Loguercio, A.D. Color Match of a Universal-shade Composite Resin for Restoration of Noncarious Cervical Lesions: An Equivalence Randomized Clinical Trial. Oper. Dent. 2024, 49, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashem, B.B.; Khairy, M.A.; Shaalanm, O.O. Evaluation of shade matching of monochromatic versus polychromatic layering techniques in restoration of fractured incisal angle of maxillary incisors: A randomized controlled trial. J. Inter. Oral Health 2023, 15, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 3 M. Filtek Universal Restorative: Technical Product Profile. 2019. Available online: https://multimedia.3m.com/mws/media/1651107O/3m-filtek-universal-restorative-technical-product-profile.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- Tokuyama. Omnichroma: Technical Report. 2024. Available online: https://omnichroma.com/us/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2019/01/OMNI-Tech-Report-Color-Final.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- VOCO. Admira Fusion x-tra: Simplicity in One Shade. 2024. Available online: https://www.voco.dental/us/portaldata/1/resources/products/folders/us/AF_x-tra_single_pages-01-2020_US_Product_Lit_FINAL_1-14-20.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- Batista, G.R.; Borges, A.B.; Zanatta, R.F.; Pucci, C.R.; Torres, C.R.G. Esthetical Properties of Single-Shade and Multishade Composites in Posterior Teeth. Int. J. Dent. 2023, 2023, 7783321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucena, C.; Ruiz-López, J.; Pulgar, R.; Della Bona, A.; Pérez, M.M. Optical behavior of one-shaded resin-based composites. Dent. Mater. 2021, 37, 840–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolone, G.; Mandurino, M.; Scotti, N.; Cantatore, G.; Blatz, M.B. Color stability of bulk-fill compared to conventional resin-based composites: A scoping review. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2023, 35, 657–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Rashidy, A.A.; Abdelraouf, R.M.; Habib, N.A. Effect of two artificial aging protocols on color and gloss of single-shade versus multi-shade resin composites. BMC Oral Health 2022, 22, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uctasli, M.B.; Garoushi, S.; Uctasli, M.; Vallittu, P.K.; Lassila, L. A comparative assessment of color stability among various commercial resin composites. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veloso, S.R.M.; Lemos, C.A.A.; de Moraes, S.L.D.; do Egito Vasconcelos, B.C.; Pellizzer, E.P.; de Melo Monteiro, G.Q. Clinical performance of bulk-fill and conventional resin composite restorations in posterior teeth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Oral Investig. 2019, 23, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbildo-Vega, H.I.; Lapinska, B.; Panda, S. Clinical Effectiveness of Bulk-Fill and Conventional Resin Composite Restorations: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Polymers 2020, 12, 1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizi, F.; Ezoji, F.; Khafri, S.; Esmaeili, B. Surface Micro-Hardness and Wear Resistance of a Self-Adhesive Flowable Composite in Comparison to Conventional Flowable Composites. Front. Dent. 2023, 20, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database | Search Strategy |

|---|---|

| Pubmed | (Single-shade [All Fields] AND (composite [All Fields] OR composites [All Fields])) OR (monoshade [All Fields] AND universal [All Fields] AND (composite [All Fields] OR composites [All Fields])) OR ((monochromatic [All Fields]) AND (composite [All Fields] OR composites [All Fields])) AND (dental restoration, permanent [MeSH Terms] OR dental restoration, permanent [MeSH Terms] OR dental restoration, permanent [MeSH Terms] OR dental restoration, permanent [MeSH Terms]) AND (Randomized controlled trials as topic [MeSH Terms] OR randomized controlled trials as topic [All Fields] OR clinical trials randomized [All Fields] OR clinical trials randomized [All Fields] OR trials randomized clinical [All Fields] OR trials randomized clinical [All Fields] OR controlled clinical trials randomized [All Fields] OR controlled clinical trials randomized [All Fields] OR randomized controlled trial [All Fields] OR randomized controlled trial [All Fields] OR clinical trial [All Fields] OR (clinical [All Fields] AND data [All fields]) OR clinical studies as topic [MeSH Terms] OR clinical studies as topic [All Fields] OR (Medical [All Fields] AND trial [All Fields]) OR intervention study [All Fields] OR (intervention [All Fields] AND trial [All Fields]) OR (interventional [All Fields] AND trial [All Fields]) OR (Interventional [All Fields] and Study [All Fields]) OR intervention studies [All Fields]) |

| Embase | (‘Single-shade composite’ OR ‘monoshade universal composite’ OR ‘monochromatic composite’) AND (‘dental restoration’/exp OR ‘dental restoration’ OR ‘Restorations, Permanent Dental’ OR ‘Restoration, Permanent Dental’ OR ‘Dental Permanent Fillings’ OR ‘Dental Permanent Filling’) AND (‘Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic’ OR ‘Clinical Trials, Randomized’ OR ‘Trials, Randomized Clinical’ OR ‘Controlled Clinical Trials, Randomized’ OR ‘Randomized Controlled Trial’ OR ‘clinical trial’ OR ‘clinical data’ OR ‘clinical studies as topic’ OR ‘medical trial’ OR ‘intervention study’ OR ‘intervention studies’ OR ‘intervention trial’ OR ‘interventional studies’ OR ‘interventional study’ OR ‘interventional trial’ |

| Web of Science | TS = (“Single-shade composite” OR “monoshade universal composite” OR “monochromatic composite”) AND TS = (“Restorations, Permanent Dental” OR “Restoration, Permanent Dental” OR “Dental Permanent Fillings” OR “Dental Permanent Filling”) AND TS = (“Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic) OR (Clinical Trials, Randomized” OR (Trials, Randomized Clinical) OR (Controlled Clinical Trials, Randomized) OR (Randomized Controlled Trial) OR (clinical trial) OR (clinical data) OR (clinical studies as topic) OR (medical trial) OR (intervention study) OR (intervention studies) OR (intervention trial) OR (interventional studies) OR (interventional study) OR (interventional trial) |

| The Chrochane Library | (Single-shade composite) OR (monoshade universal composite) OR (monochromatic composite) AND (Restorations, Permanent Dental) OR (Restoration, Permanent Dental) OR (Dental Permanent Fillings) OR (Dental Permanent Filling) AND ((Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic) OR (Clinical Trials, Randomized) OR (Trials, Randomized Clinical) OR (Controlled Clinical Trials, Randomized) OR (Randomized Controlled Trial) OR (clinical trial) OR (clinical data) OR (clinical studies as topic) OR (medical trial) OR (intervention study) OR (intervention studies) OR (intervention trial) OR (interventional studies) OR (interventional study) OR (interventional trial) |

| Scopus | ‘Restorations, AND permanent AND dental’ OR ‘restoration, AND permanent AND dental’ OR ‘dental AND permanent AND fillings’ OR ‘dental AND permanent AND filling’ AND ‘Single-shade and composite’ OR ‘monoshade and universal and composite’ OR ‘monochromatic and composite’ AND ‘Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic’ OR ‘Clinical Trials, Randomized’ OR ‘Trials, Randomized Clinical’ OR ‘Controlled Clinical Trials, Randomized’ OR ‘Randomized Controlled Trial’ OR ‘clinical trial’ OR ‘clinical data’ OR ‘clinical studies as topic’ OR ‘medical trial’ OR ‘intervention study’ OR ‘intervention studies’ OR ‘intervention trial’ OR interventional studies’ OR ‘interventional study’ OR ‘interventional trial’ |

| The USPHS Criteria |

| Color match |

| Alpha (A): The restoration matches the adjacent tooth tissue in color, shade, or translucency. |

| Bravo (B): There is a slight mismatch in color, shade, or translucency, but within the normal range of adjacent tooth structure. |

| Charlie (C): There is a slight mismatch in color, shade, or translucency, but outside of the normal range of adjacent tooth structure. |

| FDI Criteria |

| Color stability or translucency |

| Score 1: Good coloration and translucency compared to neighboring teeth. |

| Score 2: Minimal color and translucency deviation. |

| Score 3: Clear deviation, but without affecting esthetics. |

| Score 4: Localized clinical deviation that can be corrected by repair. |

| Score 5: Unacceptable, replacement necessary. |

| Author, Year | Study Design | RBCs | No. of Subjects (Mean Age) | No. of Rest. | Tooth | Finish and Polish | Light Curing | Type of Rest. | Follow-Up | Analysis Criteria | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hashem, Khairy and Shaalan [28] (2022) | RCT | Filtek universal Filtek Z3250 XT | 26 (13–30) years | 26 | Permanent incisors | Yellow-coded diamond finishing stones, Soflex discs, perio-bur #831, and rubber cup, flame, and wheel polishing tips | Elipar S10—20 s | Class IV | 3 days | USPHS | Single-resin RBC showed satisfactory shade matching potential compared to polychromatic RBCs. |

| Zulekha et al. [19] (2022) | RCT | Omnichroma Tetric N Ceram | 25 (3–5 years) | 50 | Primary anterior teeth | NM | NM | Full coronal esthetic | 12 months | USPHS | Single-shade RBC performed similarly to multi-shade in terms of the color match and color stability for both 6- and 12-month intervals. |

| Miranda et al. [27] (2024) | RCT | Admira Fusion Admira Fusion X-tra | 70 (40–58 years) | 120 | Anterior or posterior | Fine and extrafine #2200 diamond burs along with OptraPol NG | Bluephase meter II—20 s | NCCL | 7 days | FDI | The single-shade RBC used achieves the same color match compared to a multi-shade composite resin after 7. |

| Anwar, Hussein and Riad [1] (2024) | RCT | Omnichroma Tetric N Ceram | 20 (20–45 years) | 40 | Molar or premolar | Low-speed fine-grit diamond finishing stones, EVE DIACOMP Plus Occuflex-impregnated rubber cups and impregnated brushes | Bluephase Style—20 s. | Oclusal cavities | 12 months | USPHS | Single-shade RBC exhibited comparable performance to a multi-shade RBC regarding color match and color stability. |

| Parameter | No. of Studies | Study Design | Risk of Bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other Considerations | Certainty |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Color stability (1 to 7 days) | 4 | RCT | Not serious a | Not serious b | Serious c | Serious d | None | ⊕⊕OO Low |

| Color stability (12 months) | 4 | RCT | Not serious a | Not serious b | Serious c | Serious d | None | ⊕⊕OO Low |

| Single-Shade RBC | Manufacturer | Composition |

|---|---|---|

| Filtek Universal | 3 M ESPE, St. Paul, MN, USA | Fillers are a combination of a non-agglomerated/non-aggregated 20 nm silica filler, a non-agglomerated/non-aggregated 4 to 11 nm zirconia filler, an aggregated zirconia/silica cluster filler (comprised of 20 nm silica and 4 to 11 nm zirconia particles), and a ytterbium trifluoride filler. The inorganic filler loading is about 76.5% by weight (58.4% by volume). Matrix: AUDMA, AFM, diurethane-DMA, and 1,12-dodecane-DMA. |

| Omnichroma | Tokuyama Dental, Tokio, Japan | Matrix: TEGDMA, UDMA, Dibutyl hydroxyl toluene and UV absorber, Mequinol. Filler system: SiO2, ZrO2 (68 vol.—%; 79 wt%; 0.2–0.4 μm) |

| Admira Fusion X-tra | Voco GmbH, Cuxhaven, Germany | Organically modified ceramic ORMOCER. Matrix: aromatic and aliphatic dimethacrylates, methacrylatefunctionalized polysiloxane. Filler: barium aluminum borosilicate glass ceramic filler (median: 1 mm) and silicon dioxide nanoparticles (0.02 to 0.04 μm). Filler 84 wt%. Camphorquinone Pigments: ironoxide and titanium dioxide |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Leal, C.d.F.C.; Miranda, S.B.; Alves Neto, E.L.d.; Freitas, K.; de Sousa, W.V.; Lins, R.B.E.; de Andrade, A.K.M.; Montes, M.A.J.R. Color Stability of Single-Shade Resin Composites in Direct Restorations: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Polymers 2024, 16, 2172. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym16152172

Leal CdFC, Miranda SB, Alves Neto ELd, Freitas K, de Sousa WV, Lins RBE, de Andrade AKM, Montes MAJR. Color Stability of Single-Shade Resin Composites in Direct Restorations: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Polymers. 2024; 16(15):2172. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym16152172

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeal, Caroline de Farias Charamba, Samille Biasi Miranda, Everardo Lucena de Alves Neto, Keitry Freitas, Wesley Viana de Sousa, Rodrigo Barros Esteves Lins, Ana Karina Maciel de Andrade, and Marcos Antônio Japiassú Resende Montes. 2024. "Color Stability of Single-Shade Resin Composites in Direct Restorations: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials" Polymers 16, no. 15: 2172. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym16152172

APA StyleLeal, C. d. F. C., Miranda, S. B., Alves Neto, E. L. d., Freitas, K., de Sousa, W. V., Lins, R. B. E., de Andrade, A. K. M., & Montes, M. A. J. R. (2024). Color Stability of Single-Shade Resin Composites in Direct Restorations: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Polymers, 16(15), 2172. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym16152172