Polyphilicity—An Extension of the Concept of Amphiphilicity in Polymers

Abstract

1. General Introduction to Philicities/Phobicities

2. Quantitative Approaches to Philicities

2.1. Solubility Parameter Concept

2.2. The Concept of Hydrophilic–Lipophilic Balance (HLB)

2.3. Concept of Partition Coefficients

2.4. Polarity Values

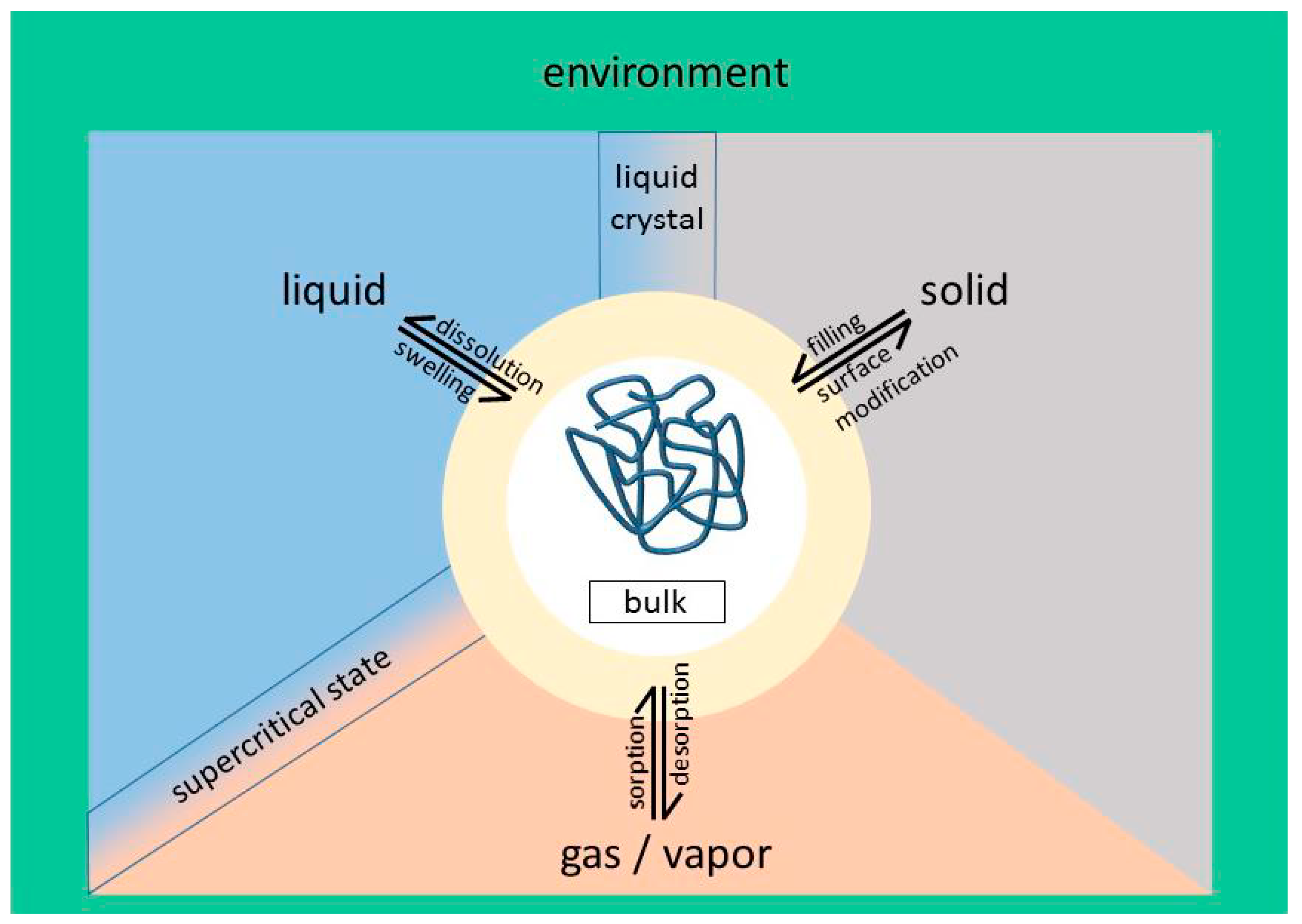

3. Philicities/Phobicities in Polymeric Systems

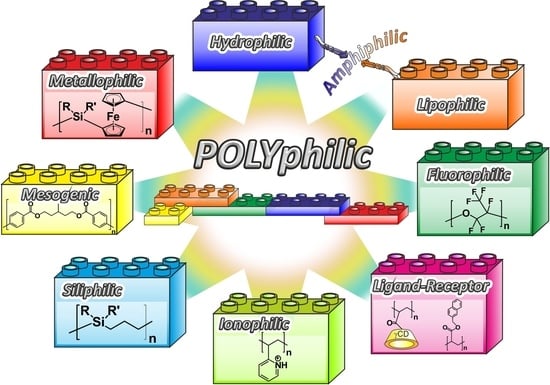

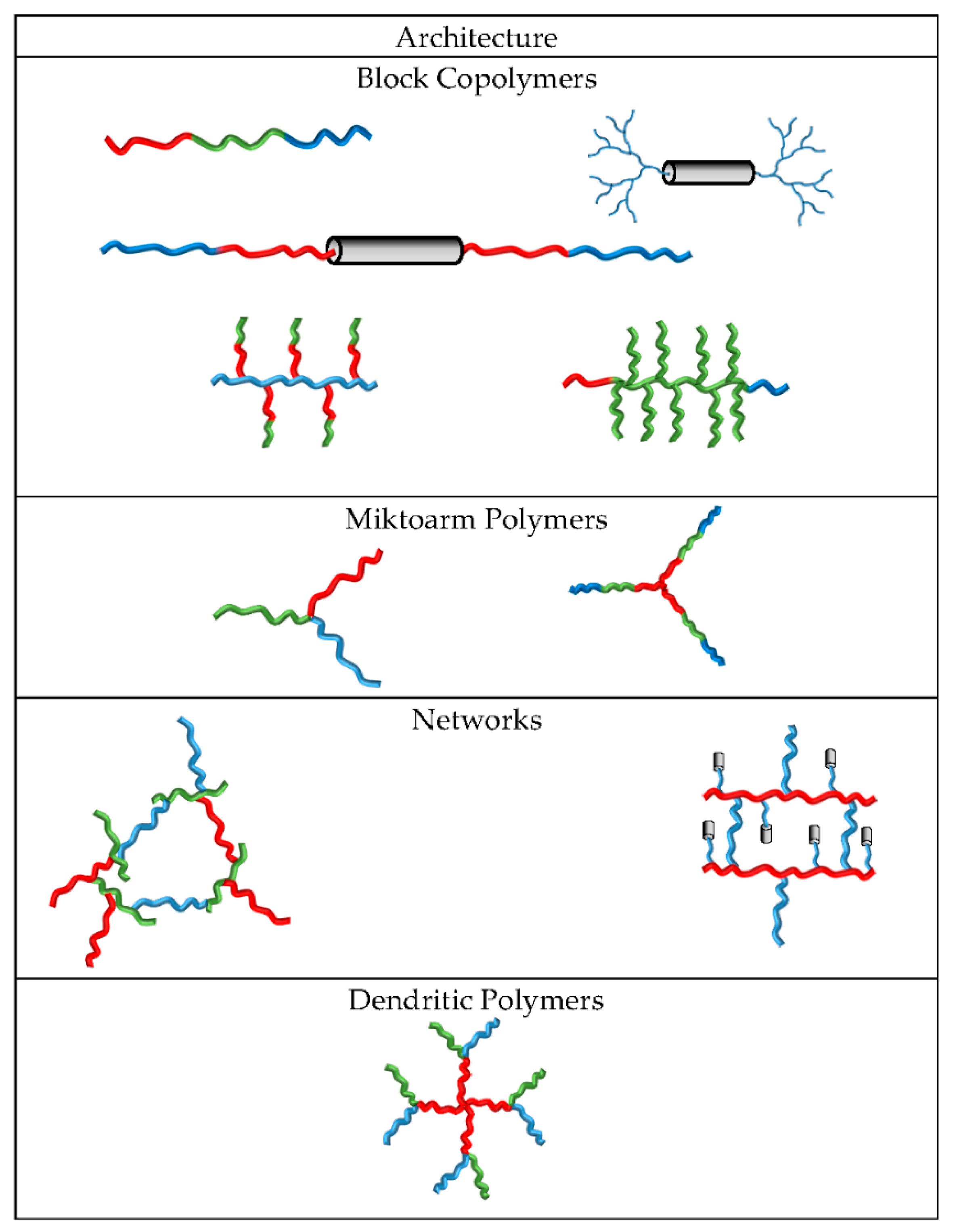

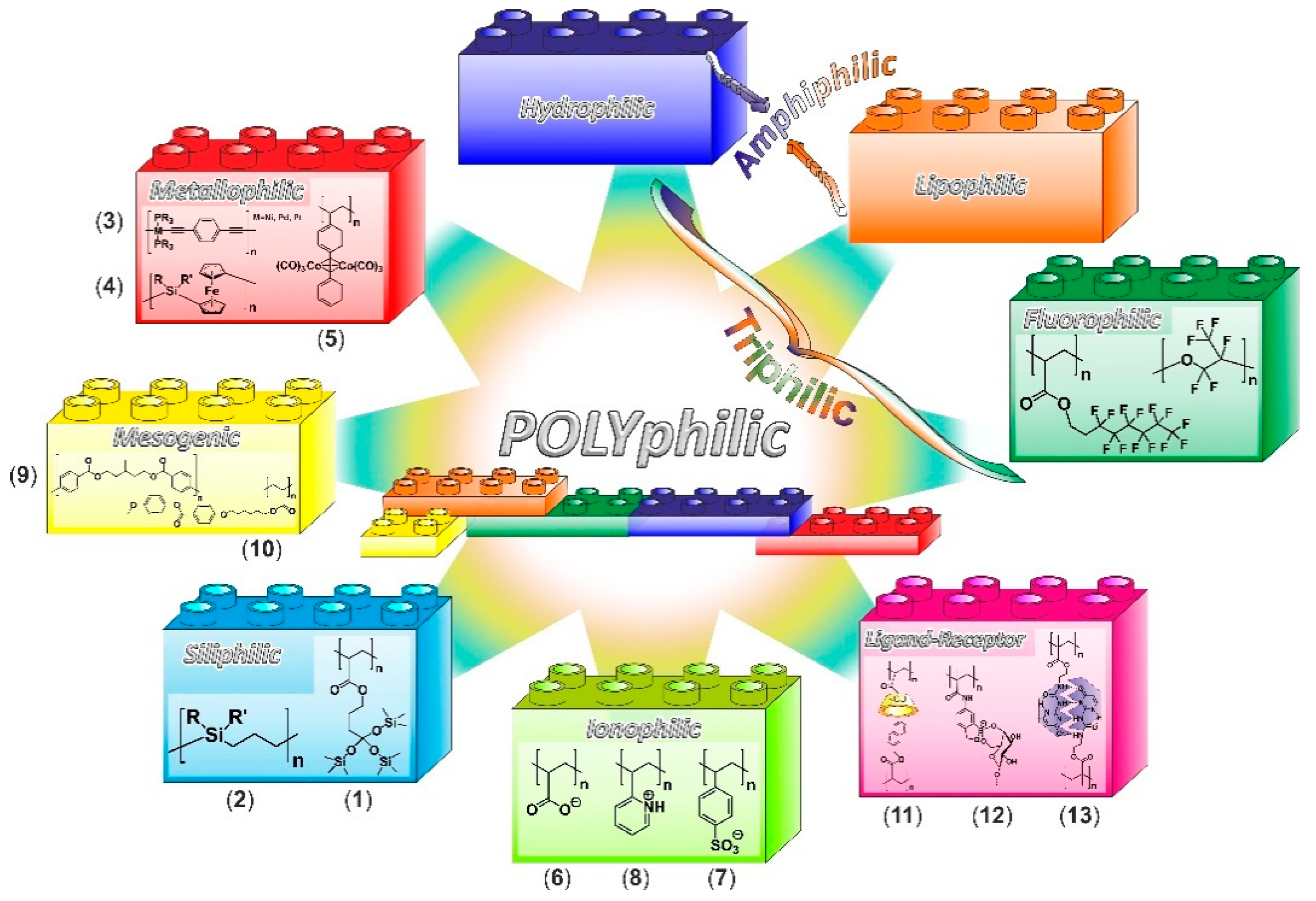

4. From Polymer Amphiphilicity to Polyphilicity

4.1. Hydrophilic, Lipophilic, and Amphiphilic Polymers

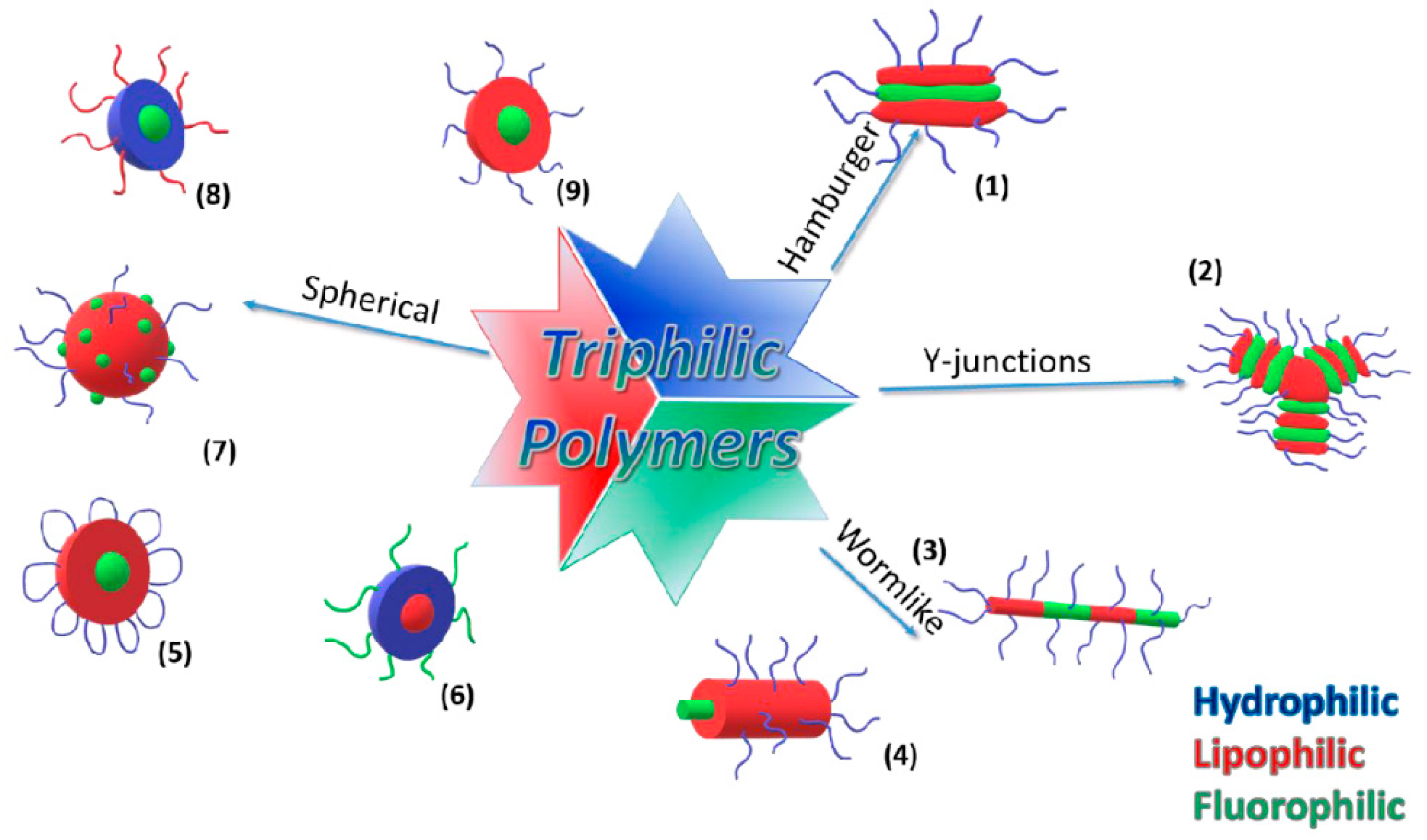

4.2. Triphilic Polymers—Hydrophilic, Lipophilic, and Fluorophilic

4.3. Additional Motives and Polyphilicity

4.3.1. Siliphilic Segments

4.3.2. Metallophilic Segments

4.3.3. Ionophilic Segments

4.3.4. Mesogenic Segments

4.3.5. Segments Containing Complementary Moieties

5. Conclusions and Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ingold, B.C.K. Significance of tautomerism and of the reactions of aromatic compounds in the electronic theory of organic reactions. J. Chem. Soc. 1933, 1120–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellmann, H. Einführung in Die Quantenchemie; Franz Deuticke: Leipzig, Germany, 1937. [Google Scholar]

- Feynman, R.P. Forces in molecules. Phys. Rev. 1939, 56, 340–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israelachvili, J.N. Intermolecular and Surface Forces, 3rd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 68–86. ISBN 978-0123919274. [Google Scholar]

- Sagawa, N.; Shikata, T. Are all polar molecules hydrophilic? Hydration numbers of nitro compounds and nitriles in aqueous solution. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 13262–13270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanford, C. The Hydrophobic Effect: Formation of Micelles and Biological Membranes, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1980; ISBN 978-0471048930. [Google Scholar]

- Böhmer, R.; Gainaru, C.; Richert, R. Structure and dynamics of monohydroxy alcohols—Milestones towards their microscopic understanding, 100 years after Debye. Phys. Rep. 2014, 545, 125–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrand, J.H.; Scott, R.L. Solubility of Non-Electrolytes, 3rd ed.; Reinhold: New York, NY, USA, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand, J.H.; Scott, R.L. Regular Solutions; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand, J.H.; Prausnitz, J.M.; Scott, R.L. Regular and Related Solutions: The Solubility of Gases, Liquids, and Solids; Van Nostrand Reinhold Co.: New York, NY, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, C.M. Three-dimensional solubility parameter-key to paint component affinities. II. Dyes, emulsifiers, mutual solubility and compatibility, and pigments. J. Paint Technol. 1967, 39, 505. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, C.M. Solvents: Theory and Practice; Advances in Chemistry Series, 124; Tess, R.W., Ed.; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, C.M. Organic solvents in high solids and water-reducible coatings. Prog. Org. Coat. 1982, 10, 331–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandrup, J.; Immergut, E.H.; Grulke, E.A. Polymer Handbook; Abe, A., Bloch, D.R., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1999; ISBN 0-471-16628-6. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, W.; Du, Y.; Xue, Y.; Frisch, H.L. Solubility parameters. In Physical Properties of Polymers Handbook; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2007; Volume 75, pp. 289–303. ISBN 0009-2665. [Google Scholar]

- Olabisi, O.; Simha, R. A semiempirical equation of state for polymer melts. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1977, 21, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoy, K.L. New values of the solubility parameters from vapor pressure data. J. Paint Technol. 1970, 42, 76. [Google Scholar]

- Van Krevelen, D.W. Properties of Polymers, Correlations with Chemical Structure; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, A.F.M. Solubility parameters. Chem. Rev. 1975, 75, 731–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flory, P. Principles of Polymer Chemistry; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 1953; ISBN 0801401348. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, W.C. Classification of surface-active agents by “HLB”. J. Cosmet. Sci. 1949, 1, 311–326. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, W.C. Calculation of HLB values of non-ionic surfactants. J. Soc. Cosmet. Chem. 1954, 5, 249–256. [Google Scholar]

- Van De Mark, M.R.; Zore, A.; Geng, P.; Zheng, F. Colloidal Unimolecular Polymer Particles: CUP. In Single-Chain Polymer Nanoparticles; Pomposo, J.A., Ed.; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA: Weinheim, Germany, 2017; pp. 259–312. ISBN 9783527806386. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, J.T.; Rideal, E.K. Interfacial Phenomena; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, Z.; Qiu, T.; Liu, W.; Zhang, L.; Tu, J.; Guo, L.; Li, X. A “green” method for preparing ABCBA penta-block elastomers by using RAFT emulsion polymerization. Polym. Chem. 2017, 8, 3013–3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, J.T. A Quantitative Kinetic Theory of Emulsion Type. I: Physical Chemistry of the Emulsifying Agent. Gas/Liquid and Liquid/Liquid Interface; Butterworths Scientific Publication: London, UK, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Abraham, M.H.; Chadha, H.S.; Whiting, G.S.; Mitchell, R.C. Hydrogen bonding. 32. An analysis of water-octanol and water-alkane partitioning and the Δlog P parameter of Seiler. J. Pharm. Sci. 1994, 83, 1085–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sangster, J. Octanol water partition coefficients of simple organic compounds. J. Phys. Chem. 1989, 18, 1111–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodor, N.; Buchwald, P. Recent advances in the brain targeting of neuropharmaceuticals by chemical delivery systems. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 1999, 36, 229–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansch, C.; Vittoria, A.; Silipo, C.; Jow, P.Y.C. Partition coefficients and the structure-activity relation of the anesthetic gases. J. Med. Chem. 1975, 18, 546–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leo, A.; Hansch, C.; Elkins, D. Partition coefficients and their uses. Chem. Rev. 1971, 71, 525–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jbeily, M.; Kressler, J. Fluorophilicity and lipophilicity of fluorinated rhodamines determined by their partition coefficients in biphasic solvent systems. J. Fluor. Chem. 2017, 193, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jbeily, M.; Schöps, R.; Kressler, J. Synthesis of fluorinated rhodamines and application for confocal laser scanning microscopy. J. Fluor. Chem. 2016, 189, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condo, P.D.; Sumpter, S.R.; Lee, M.L.; Johnston, K.P. Partition coefficients and polymer−solute interaction parameters by inverse supercritical fluid chromatography. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1996, 35, 1115–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mchugh, M.A.; Krukonis, V.J. Supercritical Fluid Extraction, 2nd ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Stoneham, MA, USA, 1994; Volume 53, ISBN 9780080518176. [Google Scholar]

- Shim, J.-J.; Johnston, K.P. Adjustable solute distribution between polymers and supercritical fluids. AIChE J. 1989, 35, 1097–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, J.; Johnston, K.P. Molecular thermodynamics of solute-polymer-supercritical fluid systems. AIChE J. 1991, 37, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Kiran, E. Miscibility, density and viscosity of poly(dimethylsiloxane) in supercritical carbon dioxide. Polymer 1995, 36, 4817–4826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smedes, F.; Geertsma, R.W.; Zande, T.V.D.; Booij, K. Polymer−water partition coefficients of hydrophobic compounds for passive sampling: Application of cosolvent models for validation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 43, 7047–7054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reichardt, C.; Welton, T. Solvents and Solvent Effects in Organic Chemistry, 4th ed.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2011; ISBN 978-3-527-32473-6. [Google Scholar]

- Katritzky, A.R.; Fara, D.C.; Yang, H.; Tämm, K.; Tamm, T.; Karelson, M. Quantitative measures of solvent polarity. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 175–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovats, E.S. Zu Fragen der Polarität—Die Methode der Linearkombination der Wechselwirkungskräfte. Chimia 1968, 22, 459. [Google Scholar]

- Grunwald, E.; Winstein, S. The correlation of solvolysis rates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1948, 70, 846–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooker, L.G.S.; Sprague, R.H. Color and constitution. IV. The absorption of phenol blue. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1941, 63, 3214–3215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooker, L.G.S.; Keyes, G.H.; Sprague, R.H.; VanDyke, R.H.; VanLare, E.; VanZandt, G.; White, F.L.; Cressman, H.W.J.; Dent, S.G. Color and constitution. X.1 Absorption of the merocyanines2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1951, 73, 5332–5350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosower, E.M. The effect of solvent on spectra. I. A new empirical measure of solvent polarity: Z-values. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1958, 80, 3253–3260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, D.; Kosower, E.M.; Wallenfels, K. The effect of solvent on spectra. VII. The “methyl effect” in thes of dihydropyridines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1961, 83, 3314–3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosower, E.M.; Ramsey, B.G. The effect of solvent on spectra. IV. Pyridinium cyclopentadienylide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1959, 81, 856–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimroth, K.; Reichardt, C.; Siepmann, T.; Bohlmann, F. Über pyridinium-N-phenol-betaine und ihre verwendung zur charakterisierung der polarität von lösungsmitteln. Justus Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1963, 661, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freed, B.K.; Biesecker, J.; Middleton, W.J. Spectral polarity index: A new method for determining the relative polarity of solvents [1]. J. Fluor. Chem. 1990, 48, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Q.; Mu, D.; Yu, L.W.; Chen, L. A simplified approach for evaluation of the polarity parameters for polymer using the K coefficient of the Mark-Houwink-Sakurada equation. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2004, 275, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spink, C.H.; Wyckoff, J.C. The apparent hydration numbers of alcohols in aqueous solution. J. Phys. Chem. 1972, 76, 1660–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shikata, T.; Takahashi, R.; Sakamoto, A. Hydration of poly(ethylene oxide)s in aqueous solution as studied by dielectric relaxation measurements. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 8941–8945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bates, C.M.; Bates, F.S. 50th anniversary perspective: Block polymers—Pure potential. Macromolecules 2017, 50, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, Y.; Eisenberg, A. Self-assembly of block copolymers. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 5969–5985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, C.; Li, Y.; Yang, D.; Hu, J.; Zhang, X.; Huang, X. Well-defined graft copolymers: From controlled synthesis to multipurpose applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 1282–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flory, P.J.; Mandelkern, L.; Hall, H.K. Crystallization in high polymers. VII. Heat of fusion of poly(N,N′-sebacoylpiperazine) and its interaction with diluents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1951, 73, 2532–2538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flory, P.J. Thermodynamics of heterogeneous polymers and their solutions. J. Chem. Phys. 1944, 12, 425–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, K.; Wang, X.; Mays, J.W.; Wooley, K.L.; Pochan, D.J. Disk-cylinder and disk-sphere nanoparticles via a block copolymer blend solution construction. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakli, A.; Kim, D.R.; Kuzma, M.R.; Saupe, A. Rotational viscosities of polymer solutions in a low molecular weight nematic liquid crystal. Mol. Cryst. Liq. Cryst. 1991, 198, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.J.; Butler, N.L. Hydrolytic degradation mechanism of Kevlar fibers when dissolved in sulfuric acid. Polym. Bull. 1992, 27, 689–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katashima, T.; Chung, U.I.; Sakai, T. Effect of swelling and deswelling on mechanical properties of polymer gels. Macromol. Symp. 2015, 358, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibayama, M.; Uesaka, M.; Inamoto, S.; Mihara, H.; Nomura, S. Analogy between swelling of gels and intrinsic viscosity of polymer solutions for ion-complexed poly(vinyl alcohol) in aqueous medium. Macromolecules 1996, 29, 885–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, C.M.; Peppas, N.A. Structure and morphology of freeze/thawed PVA hydrogels. Macromolecules 2000, 33, 2472–2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monnerie, S.; Suter, W.; Thomas, E.L.; Young, W.R.J. Biopolymers PVA Hydrogels, Anionic Polymerisation Nanocomposites; Advances in Polymer Science; Springer: Berlin Heidelberg, Germany, 2000; Volume 153, ISBN 978-3-540-67313-2. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Lei, L.; Zhu, S. Gas-responsive polymers. ACS Macro Lett. 2017, 6, 515–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.G.; Zhang, M.; Zhu, X.X. CO2-switchable self-healing host-guest hydrogels. Macromolecules 2017, 50, 9696–9701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.; Zhang, Q.; Shi, S.; Zhu, S. Breathable microgel colloidosome: Gas-switchable microcapsules with O2 and CO2 tunable shell permeability for hierarchical size-selective control release. Langmuir 2017, 33, 6108–6115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.N.; Lei, L.; Luo, Z.H.; Zhu, S. CO2/N2-Switchable thermoresponsive ionic liquid copolymer. Macromolecules 2017, 50, 8378–8389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rindfleisch, F.; DiNoia, T.P.; McHugh, M.A. Solubility of polymers and copolymers in supercritical CO2. J. Phys. Chem. 1996, 100, 15581–15587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Z.; Fan, W.; Wang, Z.; Wang, X. Synthesis of CO2-philic amphiphilic block copolymers by RAFT polymerization and its application on forming drug-loaded micelles using ScCO2 evaporation method. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2018, 44, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarbu, T.; Styranec, T.; Beckman, E.J. Non-fluorous polymers with very high solubility in supercritical CO2 down to low pressures. Nature 2000, 405, 165–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Pack, J.W.; Wang, W.; Thurecht, K.J.; Howdle, S.M. Synthesis and phase behavior of CO2-soluble hydrocarbon copolymer: Poly(vinyl) acetate-alt-dibutyl maleate. Macromolecules 2010, 43, 2276–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, E.; Tassaing, T.; Marty, J.D.; Destarac, M. Structure-property relationships in CO2-philic (co)polymers: Phase behavior, self-assembly, and stabilization of water/CO2 emulsions. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 4125–4169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray, S.S.; Okamoto, M. Polymer/layered silicate nanocomposites: A review from preparation to processing. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2003, 28, 1539–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, D.C. Polymer-filler interactions in rubber reinforcement. J. Mater. Sci. 1990, 25, 4175–4185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaia, R.A.; Maguire, J.F. Polymer nanocomposites with prescribed morphology: Going beyond nanoparticle-filled polymers. Chem. Mater. 2007, 19, 2736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidus, H. Emulsion polymers for paints. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1953, 45, 712–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, F.S.; Hillmyer, M.A.; Lodge, T.P.; Bates, C.M.; Delaney, K.T.; Fredrickson, G.H. Multiblock Polymers. Science 2012, 336, 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamley, I.W. Block Copolymers in Solution: Fundamentals and Applications; John Wiley & Sons: West Sussex, UK, 2005; ISBN 9780470015575. [Google Scholar]

- Shuler, R.L.; Zisman, W.A. A study of the behavior of polyoxyethylene at the air-water interface by wave damping and other methods. J. Phys. Chem. 1970, 74, 1523–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, B.V.K.J. Double hydrophilic block copolymer self-assembly in aqueous solution. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2018, 219, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosnan, S.M.; Schlaad, H.; Antonietti, M. Aqueous self-assembly of purely hydrophilic block copolymers into giant vesicles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 9715–9718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, K. Association behavior of fluorine-containing and non-fluorine-containing methacrylate-based amphiphilic diblock copolymer in aqueous media. Langmuir 2003, 20, 7270–7282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pospiech, D.; Liane, H.; Eckstein, K.; Voigt, D.; Jehnichen, D.; Friedel, P.; Kollig, W.; Kricheldorf, H.R. Synthesis and phase separation behaviour of high performance multiblock copolymers. High Perform. Polym. 2001, 13, 275–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaku, M.; Grimminger, L.C.; Sogah, D.Y.; Haynie, S.I. New fluorinated oxazoline block copolymer lowers the adhesion of platelets on polyurethane surfaces. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 1994, 32, 2187–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, N.M.L.; Jankova, K.; Hvilsted, S. Fluoropolymer materials and architectures prepared by controlled radical polymerizations. Eur. Polym. J. 2007, 43, 255–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koda, Y.; Terashima, T.; Sawamoto, M.; Maynard, H.D. Amphiphilic/fluorous random copolymers as a new class of non-cytotoxic polymeric materials for protein conjugation. Polym. Chem. 2015, 6, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerre, M.; Schmidt, J.; Talmon, Y.; Améduri, B.; Ladmiral, V. An amphiphilic poly(vinylidene fluoride)-b-poly(vinyl alcohol) block copolymer: Synthesis and self-assembly in water. Polym. Chem. 2017, 8, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Amado, E.; Kressler, J. Self-assembly behavior of fluorocarbon-end-capped poly(glycerol methacrylate) in aqueous solution. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2013, 291, 867–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amado, E.; Kressler, J. Synthesis and hydrolysis of α,ω-perfluoroalkyl-functionalized derivatives of poly(ethylene oxide). Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2005, 206, 850–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moughton, A.O.; Hillmyer, M.A.; Lodge, T.P. Multicompartment block polymer micelles. Macromolecules 2012, 45, 2–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tritschler, U.; Pearce, S.; Gwyther, J.; Whittell, G.R.; Manners, I. 50th anniversary perspective: Functional nanoparticles from the solution self-assembly of block copolymers. Macromolecules 2017, 50, 3439–3463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amado, E.; Kressler, J. Triphilic block copolymers with perfluorocarbon moieties in aqueous systems and their biochemical perspectives. Soft Matter 2011, 7, 7144–7149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubowicz, S.; Baussard, J.-F.; Lutz, J.-F.; Thünemann, A.F.; von Berlepsch, H.; Laschewsky, A. Multicompartment micelles formed by self-assembly of linear ABC triblock copolymers in aqueous medium. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 5262–5265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Li, Z.; Ren, Y.; Hillmyer, M.A.; Lodge, T.P. Micellar shape change and internal segregation induced by chemical modification of a tryptych block copolymer surfactant. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 10182–10183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taribagil, R.R.; Hillmyer, M.A.; Lodge, T.P. Hydrogels from ABA and ABC triblock polymers. Macromolecules 2010, 43, 5396–5404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taribagil, R.R.; Hillmyer, M.A.; Lodge, T.P. A compartmentalized hydrogel from a linear ABC terpolymer. Macromolecules 2009, 42, 1796–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Hillmyer, M.A.; Lodge, T.P. Multicompartment micelles from pH-responsive miktoarm star block terpolymers. Langmuir 2009, 25, 13718–13725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lodge, T.P.; Rasdal, A.; Li, Z.; Hillmyer, M.A. Simultaneous, segregated storage of two agents in a multicompartment micelle. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 17608–17609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lodge, T.P.; Hillmyer, M.A.; Zhou, Z.; Talmon, Y. Access to the superstrong segregation regime with nonionic ABC copolymers. Macromolecules 2004, 37, 6680–6682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jee, J.P.; McCoy, A.; Mecozzi, S. Encapsulation and release of amphotericin B from an ABC triblock fluorous copolymer. Pharm. Res. 2012, 29, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barres, A.R.; Wimmer, M.R.; Mecozzi, S. Multicompartment theranostic nanoemulsions stabilized by a triphilic semifluorinated block copolymer. Mol. Pharm. 2017, 14, 3916–3926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirao, A.; Sugiyama, K.; Yokoyama, H. Precise synthesis and surface structures of architectural per- and semifluorinated polymers with well-defined structures. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2007, 32, 1393–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugemana, C.; Chen, B.-T.; Bukhryakov, K.V.; Rodionov, V. Star block-copolymers: Enzyme-inspired catalysts for oxidation of alcohols in water. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 7862–7865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopeć, M.; Rozpedzik, A.; Łapok, Ł.; Geue, T.; Laschewsky, A.; Zapotoczny, S. Stratified micellar multilayers—Toward nanostructured photoreactors. Chem. Mater. 2016, 28, 2219–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.W.H.; Schwieger, C.; Li, Z.; Kressler, J.; Blume, A. Effect of perfluoroalkyl endgroups on the interactions of tri-block copolymers with monofluorinated F-DPPC monolayers. Polymers 2017, 9, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwieger, C.; Blaffert, J.; Li, Z.; Kressler, J.; Blume, A. Perfluorinated moieties increase the interaction of amphiphilic block copolymers with lipid monolayers. Langmuir 2016, 32, 8102–8115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amado, E.; Kressler, J. Interactions of amphiphilic block copolymers with lipid model membranes. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2011, 16, 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amado, E.; Blume, A.; Kressler, J. Novel non-ionic block copolymers tailored for interactions with phospholipids. React. Funct. Polym. 2009, 69, 450–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, W.B.; McCoy, A.M.; Fix, S.M.; Stagg, M.F.; Murphy, M.M.; Mecozzi, S. Synthesis, physicochemical characterization, and self-assembly of linear, dibranched, and miktoarm semifluorinated triphilic polymers. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2014, 52, 3324–3336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laschewsky, A.; Marsat, J.N.; Skrabania, K.; von Berlepsch, H.; Böttcher, C. Bioinspired block copolymers: Translating structural features from proteins to synthetic polymers. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2010, 211, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Hillmyer, M.A.; Lodge, T.P. Synthesis and characterization of triptych μ-ABC star triblock copolymers. Macromolecules 2004, 37, 8933–8940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Dominguez, M.; Benoit, N.; Krafft, M.P. Synthesis of triphilic, Y-shaped molecular surfactants. Tetrahedron 2008, 64, 522–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Kesselman, E.; Talmon, Y.; Hillmyer, M.A.; Lodge, T.P. Multicompartment micelles from ABC miktoarm stars in water. Science 2004, 306, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostwald, W. Zur theorie der flotation. Kolloid-Zeitschrift 1932, 58, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siedler, P.; Moeller, A.; Reddehase, T. Zur theorie der flotation. Kolloid-Zeitschrift 1932, 60, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tournilhac, F.; Bosio, L.; Nicoud, J.F.; Simon, J. Polyphilic molecules: Synthesis and mesomorphic properties of a four-block molecule. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1988, 145, 452–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, P.J.; Jochum, F.D.; Forst, F.R.; Zentel, R.; Theato, P. Influence of end groups on the stimulus-responsive behavior of poly[oligo(ethylene glycol) methacrylate] in water. Macromolecules 2010, 43, 4638–4645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yang, Y.; Li, G.; Lin, S. Synthesis and self-assembly of a novel fluorinated triphilic block copolymer. Polym. Chem. 2014, 5, 4553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrabania, K.; Laschewsky, A.; Berlepsch, H.V.; Böttcher, C. Synthesis and micellar self-assembly of ternary hydrophilic−lipophilic−fluorophilic block copolymers with a linear PEO chain. Langmuir 2009, 25, 7594–7601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koda, Y.; Terashima, T.; Sawamoto, M. Fluorous microgel star polymers: Selective recognition and separation of polyfluorinated surfactants and compounds in water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 15742–15748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Feng, Y. Flower-like multicompartment micelles with Janus-core self-assembled from fluorocarbon-terminated Pluronics. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2018, 219, 1700558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyeremateng, S.O.; Amado, E.; Blume, A.; Kressler, J. Synthesis of ABC and CABAC triphilic block copolymers by ATRP combined with “Click” chemistry. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2008, 29, 1140–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyeremateng, S.O.; Busse, K.; Kohlbrecher, J.; Kressler, J. Synthesis and self-organization of poly(propylene oxide)-based amphiphilic and triphilic block copolymers. Macromolecules 2011, 44, 583–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaberov, L.I.; Verbraeken, B.; Hruby, M.; Riabtseva, A.; Kovacik, L.; Kereïche, S.; Brus, J.; Stepanek, P.; Hoogenboom, R.; Filippov, S.K. Novel triphilic block copolymers based on poly(2-methyl-2-oxazoline)–block–poly(2-octyl-2-oxazoline) with different terminal perfluoroalkyl fragments: Synthesis and self-assembly behaviour. Eur. Polym. J. 2017, 88, 645–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyeremateng, S.O.; Schwieger, C.; Blume, A.; Kressler, J. Triphilic block copolymers: Synthesis, aggregation behavior and interactions with phospholipid membranes. ACS Symp. Ser. 2010, 1061, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thünemann, A.F.; Kubowicz, S.; Von Berlepsch, H.; Möhwald, H. Two-compartment micellar assemblies obtained via aqueous self-organization of synthetic polymer building blocks. Langmuir 2006, 22, 2506–2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.X.; Huo, X.; Han, H.J.; Lin, S.L. Synthesis, self-assembly and pH sensitivity of a novel fluorinated triphilic block copolymer. Chin. J. Polym. Sci. 2017, 35, 1363–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaberov, L.I.; Verbraeken, B.; Riabtseva, A.; Brus, J.; Talmon, Y.; Stepanek, P.; Hoogenboom, R.; Filippov, S.K. Fluorinated 2-alkyl-2-oxazolines of high reactivity: Spacer-length-induced acceleration for cationic ring-opening polymerization as a basis for triphilic block copolymer synthesis. ACS Macro Lett. 2018, 7, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenov, A.N.; Nyrkova, I.A.; Khokhlov, A.R. Polymers with strongly interacting groups: Theory for nonspherical multiplets. Macromolecules 1995, 28, 7491–7500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyrkova, I.A.; Khokhlov, A.R.; Doi, M. Microdomains in block copolymers and multiplets in ionomers: Parallels in behavior. Macromolecules 1993, 26, 3601–3610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsat, J.N.; Heydenreich, M.; Kleinpeter, E.; Berlepsch, H.V.; Böttcher, C.; Laschewsky, A. Self-assembly into multicompartment micelles and selective solubilization by hydrophilic-lipophilic-fluorophilic block copolymers. Macromolecules 2011, 44, 2092–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shunmugam, R.; Smith, C.E.; Tew, G.N. Atrp synthesis of abc lipophilic–hydrophilic–fluorophilic triblock copolymers. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2007, 45, 2601–2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weberskirch, R.; Preuschen, J.; Spiess, H.W.; Nuyken, O. Design and synthesis of a two compartment micellar system based on the self-association behavior of poly(N-acylethyleneimine) end-capped with a fluorocarbon and a hydrocarbon chain. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2000, 201, 995–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyeremateng, S.O.; Henze, T.; Busse, K.; Kressler, J. Effect of hydrophilic block-A length tuning on the aggregation behavior of α,ω-perfluoroalkyl end-capped ABA triblock copolymers in water. Macromolecules 2010, 43, 2502–2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Hillmyer, M.A.; Lodge, T.P. Morphologies of multicompartment micelles formed by ABC miktoarm star terpolymers. Langmuir 2006, 22, 9409–9417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; Peng, H.; Thurecht, K.J.; Puttick, S.; Whittaker, A.K. pH-responsive star polymer nanoparticles: Potential 19F MRI contrast agents for tumour-selective imaging. Polym. Chem. 2013, 4, 4480–4489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moughton, A.O.; Sagawa, T.; Yin, L.; Lodge, T.P.; Hillmyer, M.A. Multicompartment micelles by aqueous self-assembly of μ-A(BC)n miktobrush terpolymers. ACS Omega 2016, 1, 1027–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Shehawy, A.A.; Yokoyama, H.; Sugiyama, K.; Hirao, A. Precise synthesis of novel chain-end-functionalized polystyrenes with a definite number of perfluorooctyl groups and their surface characterization. Macromolecules 2005, 38, 8285–8299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, M.; Nitahara, S.; Aoki, H.; Ito, S.; Narazaki, M.; Matsuda, T. Synthesis and evaluation of water-soluble fluorinated dendritic block-copolymer nanoparticles as a 19F-MRI contrast agent. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2010, 211, 1602–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Liu, L.; Wang, S.; Zhu, H.; Wu, D.; Yu, Z.; Zhou, S. Dendritic mesoporous silica nanospheres synthesized by a novel dual-templating micelle system for the preparation of functional nanomaterials. Langmuir 2017, 33, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durmaz, H.; Dag, A.; Altintas, O.; Erdogan, T.; Hizal, G.; Tunca, U. One-pot synthesis of ABC type triblock copolymers via in situ click [3 + 2] and Diels−Alder [4 + 2] reactions. Macromolecules 2007, 40, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantin, M.; Chmielarz, P.; Wang, Y.; Lorandi, F.; Isse, A.A.; Gennaro, A.; Matyjaszewski, K. Harnessing the interaction between surfactant and hydrophilic catalyst to control eATRP in miniemulsion. Macromolecules 2017, 50, 3726–3732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, B.V.K.J.; Wang, C.X.; Kraemer, S.; Connal, L.A.; Klinger, D. Highly functional ellipsoidal block copolymer nanoparticles: A generalized approach to nanostructured chemical ordering in phase separated colloidal particles. Polym. Chem. 2018, 9, 1638–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.L.; Singha, N.K. A new class of dual responsive self-healable hydrogels based on a core crosslinked ionic block copolymer micelle prepared via RAFT polymerization and Diels–Alder “click” chemistry. Soft Matter 2017, 13, 9024–9035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barner-Kowollik, C.; Buback, M.; Charleux, B.; Coote, M.L.; Drache, M.; Fukuda, T.; Goto, A.; Klumperman, B.; Lowe, A.B.; Mcleary, J.B.; et al. Mechanism and kinetics of dithiobenzoate-mediated RAFT polymerization. I. The current situation. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2006, 44, 5809–5831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzalaco, S.; Fantin, M.; Scialdone, O.; Galia, A.; Isse, A.A.; Gennaro, A.; Matyjaszewski, K. Atom transfer radical polymerization with different halides (F, Cl, Br, and I): Is the process “living” in the presence of fluorinated initiators? Macromolecules 2017, 50, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patten, T.E.; Matyjaszewski, K. Atom transfer radical polymerization and the synthesis of polymeric materials. Adv. Mater. 1998, 10, 901–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-S.; Matyjaszewski, K. Controlled/”living” radical polymerization. Atom transfer radical polymerization in the presence of transition-metal complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117, 5614–5615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matyjaszewski, K. Atom transfer radical polymerization (ATRP): Current status and future perspectives. Macromolecules 2012, 45, 4015–4039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, W.H.; Sachsenhofer, R. “Click” chemistry in polymer and material science: An update. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2008, 29, 952–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Aneja, R.; Chaiken, I. Click chemistry in peptide-based drug design. Molecules 2013, 18, 9797–9817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Ikhlef, D.; Kahlal, S.; Saillard, J.; Astruc, D. Metal-catalyzed azide-alkyne “click” reactions: Mechanistic overview and recent trends. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2016, 316, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, R.; Straub, B.F. Advancements in the mechanistic understanding of the copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2013, 9, 2715–2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astruc, D.; Liang, L.; Rapakousiou, A.; Ruiz, J. Click dendrimers and triazole-related aspects: Catalysts, mechanism, synthesis, and functions. A bridge between dendritic architectures and nanomaterials. Acc. Chem. Res. 2012, 45, 630–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golas, P.L.; Matyjaszewski, K. Marrying click chemistry with polymerization: Expanding the scope of polymeric materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 1338–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golas, P.L.; Matyjaszewski, K. Click chemistry and ATRP: A beneficial union for the preparation of functional materials. QSAR Comb. Sci. 2007, 26, 1116–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsat, J.N.; Stahlhut, F.; Laschewsky, A.; Berlepsch, H.V.; Böttcher, C. Multicompartment micelles from silicone-based triphilic block copolymers. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2013, 291, 2561–2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, K.; Mizuno, U.; Matsuoka, H.; Yamaoka, H. Synthesis of novel silicon-containing amphiphilic diblock copolymers and their self-assembly formation in solution and at air/water interface. Macromolecules 2002, 35, 555–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouri, E.; Wahnes, C.; Matsumoto, K.; Matsuoka, H.; Yamaoka, H. X-ray reflectivity study of anionic amphiphilic carbosilane block copolymer monolayers on a water surface. Langmuir 2002, 18, 3865–3874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.L.; Pang, Z.Q.; Fan, L.; Hu, K.L.; Wu, B.X.; Jiang, X.G. Effect of lactoferrin- and transferrin-conjugated polymersomes in brain targeting: In vitro and in vivo evaluations. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2010, 31, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, R.; Ke, W.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, C.; Pei, Y. The use of lactoferrin as a ligand for targeting the polyamidoamine-based gene delivery system to the brain. Biomaterials 2008, 29, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallei, M.; Rüttiger, C. Recent trends in metallopolymer design: Redox-controlled surfaces, porous membranes, and switchable optical materials using ferrocene-containing polymers. Chem. A Eur. J. 2018, 24, 10006–10021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Whittell, G.R.; Manners, I. Metalloblock copolymers: New functional nanomaterials. Macromolecules 2014, 47, 3529–3543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.-L.; Yu, Z.; Wong, W.-Y. Multifunctional polymetallaynes: Properties, functions and applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 5264–5295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massey, J.A.; Temple, K.; Cao, L.; Rharbi, Y.; Raez, J.; Winnik, M.A.; Manners, I. Self-assembly of organometallic block copolymers: The role of crystallinity of the core-forming polyferrocene block in the micellar morphologies formed by poly(ferrocenylsilane-b-dimethylsiloxane) in n-alkane solvents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 11577–11584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Guerin, G.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Manners, I.; Winnik, M.A. Cylindrical block copolymer micelles and co-micelles of controlled length and architecture. Science 2007, 317, 644–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whittell, G.R.; Manners, I. Metallopolymers: New multifunctional materials. Adv. Mater. 2007, 19, 3439–3468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, F.; Jennings, M.C.; Puddephatt, R.J. Self-assembly in gold (I) chemistry: A double-stranded polymer with interstrand aurophilic interactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 969–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, B.; Hom, W.L.; Chen, X.; Yu, P.; Pavelka, L.C.; Kisslinger, K.; Parise, J.B.; Bhatia, S.R.; Grubbs, R.B. Magnetic Hydrogels from alkyne/cobalt carbonyl-functionalized ABA triblock copolymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 4616–4625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metera, K.L.; Ha-nni, K.D.; Zhou, G.; Nayak, M.K.; Bazzi, H.S.; Juncker, D.; Sleiman, H.F. Luminescent iridium(III)-containing block copolymers: Self-assembly into biotin-labeled micelles for biodetection assays. ACS Macro Lett. 2012, 1, 954–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamming, G.; Kolokotroni, J.; Harrison, T.; Penfold, T.J.; Clegg, W.; Waddell, P.G.; Probert, M.R.; Houlton, A. Structural diversity and argentophilic interactions in one-dimensional silver-based coordination polymers. Cryst. Growth Des. 2017, 17, 5753–5763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisht, K.K.; Kathalikkattil, A.C.; Suresh, E. Structure modulation, argentophilic interactions and photoluminescence properties of silver (I) coordination polymers with isomeric N-donor ligands. RSC Adv. 2012, 2, 8421–8428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, H.; Li, M.; Hao, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, S.X.A. Time-resolved monitoring of dynamic self-assembly of Au (I)-thiolate coordination polymers. Chem. Sci. 2013, 4, 1852–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, A.; Hird, B.; Moore, B. A new multiplet-cluster model for the morphology of random ionomers. Macromolecules 1990, 23, 4098–4107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekar, K.; Baskar, G. Interfacial adsorption characteristics of ionic polymeric amphiphiles with comb-like structures: Effect of dodecyl and poly(ethylene oxide) side chains. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2008, 46, 3257–3271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Chen, Z.; Zhong, S.; Wooley, K.L.; Pochan, D.J. Block copolymer assembly via kinetic control. Science 2007, 317, 647–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiriy, A.; Yu, J.; Stamm, M. Interpolyelectrolyte complexes: A single-molecule insight. Langmuir 2006, 22, 1800–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gohy, J.-F.; Varshney, S.K.; Jerome, R. Water-soluble complexes formed by poly(2-vinylpyridinium)-block-poly(ethylene oxide) and poly(sodium methacrylate)-block-poly(ethylene oxide) copolymers. Macromolecules 2001, 34, 3361–3366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.M.; Song, G.; Hwang, S.K.; Kim, R.H.; Lee, J.; Yu, S.; Huh, J.; Park, H.J.; Park, C. Controlled nanopores in thin films of nonstoichiometrically supramolecularly assembled graft copolymers. Chem. A Eur. J. 2015, 21, 18375–18382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tschierske, C. Development of structural complexity by liquid-crystal self-assembly. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 8828–8878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishige, R.; Ohta, N.; Ogawa, H.; Tokita, M.; Takahara, A. Fully liquid-crystalline ABA triblock copolymer of fluorinated side-chain liquid-crystalline A block and main-chain liquid-crystalline B block: Higher order structure in bulk and thin film states. Macromolecules 2016, 49, 6061–6074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Piñol, R.; Nono-Djamen, M.; Pensec, S.; Keller, P.; Albouy, P.-A.; Lévy, D.; Li, M.-H. Self-assembly of liquid crystal block copolymer PEG-b-smectic polymer in pure state and in dilute aqueous solution. Faraday Discuss. 2009, 143, 235–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.-F.; Shen, Z.; Wan, X.; Fan, X.; Chen, E.; Ma, Y.; Zhou, Q.-F. Mesogen-jacketed liquid crystalline polymers. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 3072–3101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashidzume, A.; Zheng, Y.; Takashima, Y.; Yamaguchi, H.; Harada, A. Macroscopic self-assembly based on molecular recognition: Effect of linkage between aromatics and the polyacrylamide gel scaffold, amide versus ester. Macromolecules 2013, 46, 1939–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambre, J.N.; Sumerlin, B.S. Biomedical applications of boronic acid polymers. Polymer 2011, 52, 4631–4643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amado, E.; Kressler, J. Reversible complexation of iminophenylboronates with mono- and dihydroxy methacrylate monomers and their polymerization at low temperature by photoinduced ATRP in one pot. Macromolecules 2016, 49, 1532–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotsuchibashi, Y.; Ebara, M.; Sato, T.; Wang, Y.; Rajender, R.; Hall, D.G.; Narain, R.; Aoyagi, T. Spatiotemporal control of synergistic gel disintegration consisting of boroxole- and glyco-based polymers via photoinduced proton transfer. J. Phys. Chem. B 2015, 119, 2323–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kajita, T.; Noro, A.; Matsushita, Y. Design and properties of supramolecular elastomers. Polymer 2017, 128, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, K.E.; Kade, M.J.; Meijer, E.W.; Hawker, C.J.; Kramer, E.J. Model transient networks from strongly hydrogen-bonded polymers. Macromolecules 2009, 42, 9072–9081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenfield, J.L.; Rizzuto, F.J.; Goldberga, I.; Nitschke, J. Self-Assembly of conjugated metallopolymers with tuneable length and controlled regiochemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 7649–7653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lye, D.S.; Xia, Y.; Wong, M.Z.; Wang, Y.; Nieh, M.-P.; Weck, M. ABC Supramolecular triblock copolymer by ROMP and ATRP. Macromolecules 2017, 50, 4244–4255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaberov, L.I.; Verbraeken, B.; Riabtseva, A.; Brus, J.; Radulescu, A.; Talmon, Y.; Stepanek, P.; Hoogenboom, R.; Filippov, S.K. Fluorophilic–Lipophilic–Hydrophilic Poly(2-oxazoline) Block Copolymers as MRI Contrast Agents: From Synthesis to Self-Assembly. Macromolecules 2018, 51, 6047–6056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boye, S.; Ennen, F.; Scharfenberg, L.; Appelhans, D.; Nilsson, L.; Lederer, A. From 1D rods to 3D networks: A biohybrid topological diversity investigated by asymmetrical flow field-flow fractionation. Macromolecules 2015, 48, 4607–4619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Liu, Y.; Babu, T.; Wei, Z.; Nie, Z. Self-assembly of inorganic nanoparticle vesicles and tubules driven by tethered linear block copolymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 11342–11345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, J.J.; Kim, B.J.; Kramer, E.J.; Pine, D.J. Control of nanoparticle location in block copolymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 5036–5037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, J.; Cheng, L.; Liu, A.; Yin, J.; Kuang, M.; Duan, H. Plasmonic vesicles of amphiphilic gold nanocrystals: Self-assembly and external-stimuli-triggered destruction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 10760–10763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, Z.; Fava, D.; Kumacheva, E.; Zou, S.; Walker, G.C.; Rubinstein, M. Self-assembly of metal-polymer analogues of amphiphilic triblock copolymers. Nat. Mater. 2007, 6, 609–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, J.; Badelt-Lichtblau, H.; Ebner, A.; Preiner, J.; Kraxberger, B.; Gruber, H.J.; Sleytr, U.B.; Ilk, N.; Hinterdorfer, P. Fabrication of highly ordered gold nanoparticle arrays templated by crystalline lattices of bacterial S-layer protein. ChemPhysChem 2008, 9, 2317–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jo, Y.S.; Kim, D.K.; Muhammed, M. Synchronous delivery systems composed of Au nanoparticles and stimuli-sensitive diblock terpolymer. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2004, 5, 1291–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakhshpour, M.; Bereli, N.; Şenel, S. Preparation and characterization of thiophilic cryogels with 2-mercapto ethanol as the ligand for IgG purification. Colloids Surf. B 2013, 113, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porath, J.; Maisano, F.; Belew, M. Thiophilic adsorption-a new method for protein fractionation. FEBS Lett. 1985, 185, 306–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porath, J.; Belew, M. “Thiophilic” interaction and the selective adsorption of proteins. Trends Biotechnol. 1987, 5, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.; Li, C.; Lin, Z.; Zhang, Y. Using thiophilic magnetic beads in purification of antibodies from human serum. Colloids Surf. B 2010, 75, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Li, C.; Qian, H. Purification antibody by thiophilic magnetic sorbent modified with 2-mercapto-1-methylimidazol. Colloids Surf. B 2013, 108, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, H.; Lin, Z.; Xu, H.; Chen, M. The efficient and specific isolation of the antibodies from human serum by thiophilic paramagnetic polymer nanospheres. Biotechnol. Prog. 2009, 25, 376–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulkoski, D.; Scholz, C. Synthesis and application of aurophilic Poly(cysteine) and Poly(cysteine)-containing copolymers. Polymers 2017, 9, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidbaur, H. Ludwig mond lecture. Chem. Soc. Rev. 1995, 24, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priegert, A.M.; Rawe, B.W.; Serin, S.C.; Gates, D.P. Polymers and the p-block elements. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 922–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jäkle, F. Advances in the synthesis of organoborane polymers for optical, electronic, and sensory applications. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 3985–4022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bull, S.D.; Davidson, M.G.; Van Den Elsen, J.M.H.; Fossey, J.S.; Jenkins, A.T.A.; Jiang, Y.B.; Kubo, Y.; Marken, F.; Sakurai, K.; Zhao, J.; et al. Exploiting the reversible covalent bonding of boronic acids: Recognition, sensing, and assembly. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013, 46, 312–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, W.L.A.; Sumerlin, B.S. Synthesis and Applications of boronic acid-containing polymers: From materials to medicine. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 1375–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dzhemilev, U.M.; Azhgaliev, V.N.; Muslukhov, R.R. Organometallic chemistry. Russ. Chem. Bull. 1995, 44, 17–31. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, C.; Zhou, L.; Lv, J. Effects of expandable graphite and modified ammonium polyphosphate on the flame-retardant and mechanical properties of wood flour-polypropylene composites. Polym. Polym. Compos. 2013, 21, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavelin, P.; Ljungba, R.; Jannasch, P.; Wessle, B. Amphiphilic polymer gel electrolytes. 3. Influence of the ionophobic–ionophilic balance on the ion conductive properties. Electrochim. Acta 2001, 46, 1439–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavelin, P.; Jannasch, P.; Furó, I.; Pettersson, E.; Stilbs, P.; Topgaard, D.; Söderman, O. Amphiphilic polymer gel electrolytes. 4. Ion transport and dynamics as studied by multinuclear pulsed field gradient spin-echo NMR. Macromolecules 2002, 35, 5097–5104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavelin, P. Amphiphilic solid polymer electrolytes. Solid State Ion. 2002, 147, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.P.; Apperley, D.C.; Liu, J.; Zheng, Y.; Wright, P.V. Grain boundaries and the influence of the ionophilic-ionophobic balance on 7Li and 19F NMR and conductivity in low-dimensional polymer electrolytes with lithium tetrafluoroborate. Electrochim. Acta 2007, 53, 1444–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavelin, P.; Jannasch, P.; Wessle, B. Amphiphilic polymer gel electrolytes. I. Preparation of gels based on poly(ethylene oxide) graft copolymers containing different ionophobic groups. Polymer 2001, 39, 2223–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pensec, S.; Tournilhac, F.-G. An ω-functionalized perfluoroalkyl chain: Synthesis and use in liquid crystal design. Chem. Commun. 1997, 441–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Ainsa, S.; Marcos, M.; Barberá, J.; Serrano, J.L. Philic and phobic segregation in liquid-crystal ionic dendrimers: An enthalpy-entropy competition. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 1990–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Date, R.W.; Bruce, D.W. Shape amphiphiles: Mixing rods and disks in liquid crystals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 9012–9013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kouwer, P.H.J.; Mehl, G.H. Hierarchical organisation in shape-amphiphilic liquid crystals. J. Mater. Chem. 2009, 19, 1564–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.F.; Mondal, B.; Lyons, A.M. Fabricating superhydrophobic polymer surfaces with excellent abrasion resistance by a simple lamination templating method. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2011, 3, 3508–3514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuteja, A.; Choi, W.; Mabry, J.M.; McKinley, G.H.; Cohen, R.E. Robust omniphobic surfaces. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 18200–18205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leslie, D.C.; Waterhouse, A.; Berthet, J.B.; Valentin, T.M.; Watters, A.L.; Jain, A.; Kim, P.; Hatton, B.D.; Nedder, A.; Donovan, K.; et al. A bioinspired omniphobic surface coating on medical devices prevents thrombosis and biofouling. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014, 32, 1134–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Affinity | Class | Segment/Block Example | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metallophilic | Main-chain metal centers | Polymetallaynes: Ni, Pd, Pt, and | [166] |

| Poly(ferrocenylsilane)s | [167,168] | ||

| Gold-carboxylate | [170] | ||

| Side-chain metal centers | Cobalt hexacarbonyl and Iridium phenylpyridine | [171,172] | |

| Supramolecular coordination | Supramolecular metal complexes with polymers incorporating nitrogen-containing ligands | [169,192,193] | |

| Ionophilic | Electrolytes/ionomers | Poly(acrylic acid) complexes with diamines, | [178] |

| Poly(methacrylic acid) complexes with aromatic polyamines (poly[2-vinylpyridinium]), | [180] | ||

| Poly(sulfonic acid) clusters, | [177] | ||

| Poly(sulfonic acid)s complexes with polycations (poly[dimethylbenzylammonium]), | [179] | ||

| or aromatic polyamines [poly(2-vinylpyridinium)] | [181] | ||

| Fluorophilic | Fluorinated | Fluoroalkyl segments | [94,183,194] |

| Siliphilic | Carbosilanes | Poly(1,1-dialkylsilacyclobutane)s | [160,161] |

| Siloxanes | Tris(trimethylsiloxy)silyl moieties | [159] | |

| Mesogenic | Liquid crystals | Main-/side-chain liquid crystalline blocks | [182,183,184,185] |

| Specific molecular recognition | Ligand-receptor | Cyclodextrin-aromatics/or -adamantine | [186] |

| Biotin-avidin | [195] | ||

| Boronic acid-saccharides/or -polyols | [187,188,189] | ||

| Thiol–gold nanoparticles | [196,197,198] | ||

| Self-complementary | Ureidopyrimidinone | [190,191] |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Heinz, D.; Amado, E.; Kressler, J. Polyphilicity—An Extension of the Concept of Amphiphilicity in Polymers. Polymers 2018, 10, 960. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym10090960

Heinz D, Amado E, Kressler J. Polyphilicity—An Extension of the Concept of Amphiphilicity in Polymers. Polymers. 2018; 10(9):960. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym10090960

Chicago/Turabian StyleHeinz, Daniel, Elkin Amado, and Jörg Kressler. 2018. "Polyphilicity—An Extension of the Concept of Amphiphilicity in Polymers" Polymers 10, no. 9: 960. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym10090960

APA StyleHeinz, D., Amado, E., & Kressler, J. (2018). Polyphilicity—An Extension of the Concept of Amphiphilicity in Polymers. Polymers, 10(9), 960. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym10090960