1. Introduction

Liquid crystals (LCs) consist of anisotropic particles whose inherent translational and orientational degrees of freedom give rise to key macroscopic anisotropies, including birefringence, elasticity, and dielectric response [

1,

2]. This molecular architecture supports a range of ordered mesophases including nematic, smectic, and columnar states defined by the coexistence of long-range order and fluidity. As a result, LCs are highly sensitive to external fields and spatial constraints. Under confinement, the intrinsic shape anisotropy of the constituent particles couples strongly with imposed boundaries, leading to a rich variety of distinct phases and structural configurations [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. This pronounced sensitivity to geometrical constraints establishes LCs as an exemplary platform for studying how physical boundaries govern the organization of soft matter, driving sustained research and enabling key applications in displays, biosensors, optical switches, and other electro-optical technologies [

7,

8,

9].

As manifestations of singularities and discontinuities in the order parameter field, topological defects occur across diverse physical systems and provide a natural link between topological concepts and condensed matter physics [

10]. Defects play a fundamental role in liquid crystals governing both their structures and dynamics, with the resulting defect configurations directly influence polarized optical responses. In confined geometries, Ls systems have been extensively studied, revealing that defect pattern formation stems from the interplay between surface anchoring and the material’s inherent orientational symmetry breaking [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. Recent investigations have expanded the scope to include active and driven non-equilibrium systems [

17,

18,

19]. Yeomans et al. model the epithelium as an active nematic liquid crystal and demonstrates that defect-induced isotropic stresses are the primary precursor of mechanotransductive responses in cell death and extrusions [

20]. Yeomans and colleagues further investigate the flow and defect configurations of an active nematic confined to rectangular channels of varying width and highlights the importance of topological defects in controlling the confined flows [

19].

The temporal modulation of activity, demonstrated in active chiral fluids [

21,

22] and magnetic particle suspensions [

23], enables the exploration of dynamic self-organization with enhanced complexity and controllability. In these systems, sustained energy input gives rise to striking flow patterns and structural formations, while defect states can be switched through mechanisms like temporal boundary modulation. In quasi-2D geometries, periodic boundary motion is anticipated to exert a pronounced influence on the spatial organization of ellipsoidal systems. This type of driving renders the system dissipative, analogous to behaviors observed in fluids and granular materials, and promotes collective motion along with steady pattern formation far from equilibrium [

24,

25].

In this work, we employ Langevin dynamics simulations to systematically investigate the effects of five distinct boundary actuation modes on novel phase behaviors and defect structural transitions. In contrast to chemically tailored substrates that typically impose static homeotropic or planar anchoring, temporally oscillating boundaries offer active control directing particles to align either parallel or perpendicular to the oscillation direction. This controlled symmetry breaking facilitates the formation of diverse non-equilibrium conformational states. We demonstrate that periodic boundary vibration effectively regulate molecular alignment and their responses to different energy inputs. This approach not only establishes a versatile pathway for pattern formation and defect transformation, but also opens a promising avenue for the design of novel functional materials.

2. Models and Methods

We focus on a two-dimensional system of ellipsoidal particles, representing liquid crystals, confined within a rectangular cavity with time-oscillating boundaries. Using Langevin dynamics simulations, we examine how this dynamic confinement governs structural formation and phase transitions. The square dynamic boundary is constructed as four independent walls. Each wall comprises 51 spherical beads, resulting in a total of 204 beads, and interactions between these boundary particles are neglected. The Cartesian coordinates system is set as the left and bottom wall in which x and y axes are along the horizontal and vertical directions, respectively. Five different boundary oscillation conditions are investigated: oscillation along a single wall, oscillations on the upper and lower walls, oscillations on the upper and left walls, oscillations on three walls, and oscillations along all four walls. The oscillatory motion of each wall is described by the following equations: (bottom wall), (up wall), (left wall), (right wall), where defines the maximal cavity size, A is the oscillation amplitude, and f is the oscillation frequency. The vibration of the boundaries causes the area of the square confinement to vary periodically. The system is confined in the vertical direction to a thickness of , thereby restricting all particle motion to two dimensions. We consider a system N = 506 ellipsoid particles with semilong axis and semishort axes of the aspect ratio , corresponding to area fractions , where the equilibrium bulk configuration is a diagonal structure.

Molecular simulations have proven to be an established approach for investigating the properties and dynamics of confined liquid crystals LCs. Among various intermolecular potentials, the Gay–Berne (GB) model has been widely adopted for simulating LC systems due to its efficient description of anisotropic interactions [

5,

26,

27,

28,

29]. For a pair of LC molecules, the GB potential is expressed as

Here,

is the separation vector connecting molecules

j and

i, and

is the unit vector aligned with this direction. The orientation of each molecule is given by the unit vectors

and

for molecules

i and

j, respectively. The orientation-dependent range parameter

is given by

and the potential energy well-depth anisotropy is expressed as

with

and

Here,

and

define the energy and length units, respectively. The molecular shape anisotropy is characterized by the parameter

, which depends on the aspect ratio

, where

and

are the lengths of the major and minor axes of the ellipsoidal particles. The energy anisotropy is described by

, which relates to the ratio of the potential well depths

for side-by-side (

) and end-to-end (

) configurations. The explicit forms of

and

are given by

The parameters

and

determine the shape of the anisotropic interaction. Each GB model is defined by a set of four parameters:

,

,

, and

. In this work, we employ the parameter set (4.4, 20, 1, 1), which is commonly adopted to model the rigid molecular architecture of p-terphenyls and related derivatives. With this parameterization, the system can reproduce four distinct mesophases [

27,

30,

31,

32,

33].

For the ellipsoid–sphere potential, particle

i is modeled as a sphere and particle

j as an ellipsoid. Therefore, the shape parameter and the potential energy well-depth anisotropy between the boundary beads and the ellipsoid particles expressed as

and

Langevin dynamics simulations were performed using the LAMMPS 3 Mar 2020 package [

34]. To ensure overdamped particle dynamics, the translational and rotational friction coefficients in the Langevin thermostat are set to

[

24,

35]. All physical quantities are reported in reduced units. The system is nondimensionalized by setting the fundamental units of energy, distance, and particle mass to

,

, and

, respectively. Consequently, the derived units are as follows: time is given by

, number density by

, translational friction coefficient by

, and rotational friction

. A cutoff distance of

was applied to intermolecular interactions. The Velocity-Verlet algorithm was used to integrate particle motion with a time step of

. For simulations with larger amplitude or higher frequency, a smaller time step was adopted to attain steady structures. We initialized five distinct configurations by randomly placing ellipsoidal particles within the simulation box. All runs were propagated for sufficiently long durations to ensure the system reached a steady state. Data were averaged over 5000 steady-state configurations, and particle trajectories and snapshots were visualized and analyzed using the OVITO 3.11.0 package.

The orientational order parameter

S [

13,

33] is employed to identify and distinguish the phase structures formed by Gay–Berne particles under various boundary-oscillation modes. It is defined as the largest positive eigenvalue of the order tensor

, where

(

i) is the

th component of the orientation vector

of the

ith particle. The value of

S varies between 0 and 1:

indicates a completely isotropic (random) phase, while

corresponds to a perfectly aligned phase. The eigenvector associated with

S defines the director field

. To resolve local structural features, a local order parameter

is used to characterize defect regions. In addition, the tilt angle

is introduced to quantify the orientation of individual particles, defined as the angle between the major axis of an ellipsoid and the y-axis. To capture structural transitions at the system level, the global tilt order parameter

is also defined, representing the angle between the ensemble-averaged director field and the y-axis.

3. Results and Discussion

Some common stable defects within the equilibrium rectangular confinement are diagonal, X-shaped, and long-axis states [

36,

37,

38]. In our simulations, we first examine the equilibrium phase behavior of ellipsoids confined within a static square boundary (

Figure S1). Under static confinement, the surfaces induce planar ordering, cause the long axes of the particles to align predominantly parallel to the walls. Particles in the central region mutually align along one of the square’s diagonals. This diagonal pattern represents one of the most fundamental and widely studied defect configurations in confined nematics. Jeff Z. Y. Chen et al. [

36,

37] demonstrated that the diagonal state possesses the lowest free energy across a relevant dimensionless geometric parameter space. Experimentally, analogous nematic arrangements have been reported in centimeter-scale granular rods confined in square cells [

39]. Density plays a crucial role in the isotropic–nematic transition [

40,

41]. In confined systems where finite particle size effects are significant, novel defect structures emerge to mediate the competition between mutual particle alignment and alignment imposed by the walls. Our study focuses on liquid crystal systems under conditions of high density and finite size. Under fixed boundary conditions, the system forms ordered diagonal structures at volume fractions of

,

, and

(

Figure S1). The positional order of the internal particles increases progressively with higher

. When the fraction is further raised to

, the anisotropic shape of the ellipsoids severely restricts their motion (

Figure S1(d1)), leading to an orientational glassy state with multi-defect structures (

Figure S1(d2)). The introduction of oscillating boundaries restores particle mobility, facilitating the emergence of well-ordered steady configurations. Upon the onset of periodic boundary stretching and contraction, the behavior of the system changes entirely. Although the volume of the confined system oscillates synchronously with the boundary motion, the self-organized structure of the confined ellipsoids remains largely invariant. We refer to this persistent configuration as a steady structure. Such ordered, non-equilibrium steady structures have also been widely observed in other driven systems, such as horizontally and vertically oscillated granular materials [

42,

43]. By analyzing how structure formation is directed by the energy input topology across different oscillation modes, we reveal a general principle for controlling the self-assembly pathways in anisotropic soft matter.

3.1. Steady Pattern Under One-Side Oscillation

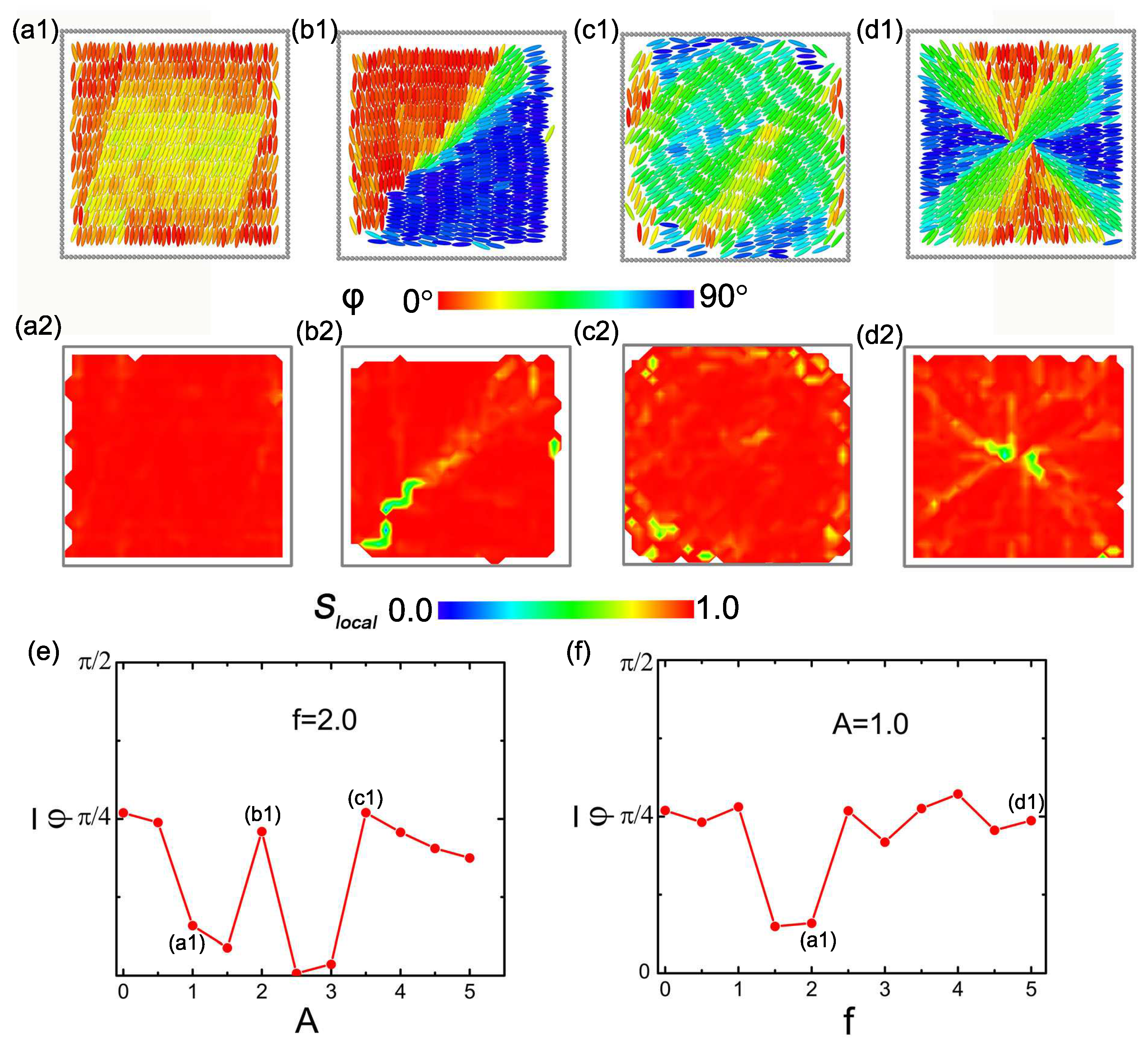

We investigate five distinct actuation modes of the dynamic boundary. The first mode corresponds to a cavity with only one oscillating wall, while the remaining three walls remain stationary. Typical configurations of GB particles under four different driven boundary parameters are presented in the first row of

Figure 1, where particles are colored according to their orientation angle relative to the y-axis. All conformations mentioned hereafter are shown at the maximum scale at

. To better identify the defect structures shown in the second row, particles are also colored based on their local order parameter

, which is calculated within a unit square lattice. The local nematic order parameter

is calculated on a grid with a spacing of

. This choice minimizes noise from single particle positions while retaining sufficient resolution to localize topological defects (singularities). Regions with low

values are shown in green [

33,

44]. At a driving frequency of

f = 2.0 and an amplitude of

A = 1.0, the ellipsoids in

Figure 1(a1) form a nematic-like arrangement similar to the equilibrium phase under static confinement, characterized by a director field aligned along the diagonal (denoted as

or

). When the amplitude increases to 2.0 (

Figure 1(b1)), particles near the oscillating boundary become perpendicular to it, meaning more particles align parallel to the y-axis, while those in the central diagonal region decrease in number, shifting the director angle toward approximately

. At an amplitude of 4.0, the increased compression confines the particles to a smaller volume and higher density, which in turn forces the director angle to approach zero (

Figure 1(c1)). At the higher frequency of 5.0 (

Figure 1(d1)), particles near the boundary become disordered due to the heightened kinetic activity induced by the rapid oscillation. From

Figure 1(a2–d2), defects progressively accumulate and become more pronounced in the bottom corner. The symmetry of the system is strongly broken by the one-sided drive, thereby establishing a steep gradient in the input energy along the driving direction.

Focusing on the steady structures, we examine the fixed frequency (

f = 2.0) and amplitude (

A = 1.0) conditions. The following research is centered on the two parameter sets. The associated structural transition is quantified by the tilt angle, denoted as

, which is defined as the angle between the global director field and the y-axis. This angle is obtained by averaging over one thousand oscillation cycles after the system reaches a steady state. A value of

= 0 indicates alignment parallel to the y-axis, while

corresponds to alignment parallel to the x-axis.

Figure 1e plots

as a function of amplitude at a fixed frequency of

f = 2.0. The curve displays abrupt jumps, signifying a discrete structural transition. Specifically, these jumps mark a stepwise director reorientation: initially from the diagonal (

), then to an intermediate angle (

), and finally to near alignment with the y-axis. Meanwhile, as shown in

Figure 1f for a fixed amplitude of

A = 1.0,

remains stable around

when the frequency is varied, indicating the absence of any structural transitions.

3.2. Steady Pattern Under Opposing-Side Oscillation

Dynamic structural reconstruction is promoted by the intensified perturbations and flows resulting from synergistic energy input between opposing oscillating walls, an effect significantly stronger than in single-side driving. This is illustrated in

Figure 2, where panels (a1–d1) show snapshots of the system under top–bottom oscillation and panels (a2–d2) plot the corresponding local order parameter

. Driven by increasing amplitude at a fixed frequency

f = 2.0, the system experiences a boundary-mediated anchoring transition, evolving from a diagonal to a homeotropic and then to a planar structure. At low amplitude, similar to

Figure S1(a1) a near-equilibrium diagonal structure is maintained. A structure exhibiting both high orientational and positional order develops along the oscillating boundary at

A = 1.0 (

Figure 2(a1)). In this configuration, the ellipsoids form smectic-like layers that are aligned perpendicular to the oscillating wall. A similar perpendicular smectic-like structure is observed at

A = 3.0 (

Figure 2(b1)). Furthermore, the corresponding order parameter maps in

Figure 2(a2,b2) show that this region contains almost no topological defects. At

A = 4.0, the system transitions into an ordered state aligned with the x-axis, featuring both positional and orientational order and a slightly tilted director (

Figure 2(c1)). As the oscillatory strength further increases, the enhanced energy input from the faster boundary motion promotes disorder. Consequently, particles near the wall become disordered while the core retains orientational and translational order, and the region of particle motion expands (

Figure 2(d1)). This two-step anchoring transition is governed by the oscillation amplitude. Under moderate amplitudes, the particles exhibit normal (homeotropic) alignment, as the oscillatory compression confines them into a smaller area, thereby increasing the density and favoring efficient normal packing. In contrast, at larger amplitudes, the significantly enhanced energy input raises the kinetic energy of particles near the boundary. This leads to higher particle velocities, which disrupt the local order adjacent to the oscillating interface. Consequently, as the collective behavior of the particles breaks down, the overall alignment shifts to a parallel configuration.

Defects are clearly observed near the non-oscillating sides in both parallel configurations (

Figure 2(c2,d2)). Increased energy induces stronger disorder near the wall, producing more boundary defects (

Figure 2(d2)). The structural evolution under different driving conditions is quantified by the director angle profiles in

Figure 2e,f. Specifically,

Figure 2e shows the progression of

from

to near 0 and then to approximately

, corresponding to the particle reorientation sequence from diagonal to y-axis to x-axis alignment. Meanwhile,

Figure 2f indicates that varying the frequency at a fixed amplitude

A = 1.0 induces significant structural changes, unlike the stable response under single-side oscillation. In particular, the system evolves from a diagonally aligned state to one aligned with the y-axis, and finally to a state with its director tilted relative to the y-axis (see

Figure S2(a1,a2)).

3.3. Steady Pattern Under Adjacent-Side Oscillation

The oscillation of adjacent walls simultaneously breaks horizontal and vertical symmetry, forcing particle alignment to compete along multiple directions and thereby preventing a uniform phase. Consequently, this competition gives rise to a diverse array of distinct structural phases, illustrated in

Figure 3. For

f = 2.0 and

A = 1.0, the limited energy input creates a hybrid structure. The left region is characterized by a near-equilibrium structure with the presence of small defects. In contrast, the right region is characterized by a dominant x-axis orientation and is virtually free of defects. The overall configuration exhibits a director angle of approximately

, as shown in

Figure 3(a1,a2). Nevertheless, this structure is not stable. Instead, particles form a twisted smectic phase where the layers are oriented perpendicular to the upper boundary, as depicted in

Figure S3a. At

A = 1.5, a hybrid structure characterized by three distinct orientational domains is observed, shown in

Figure S3b. When the amplitude is increased to

A = 2.0, the system transitions to

structure, which is characterized by two interior defects (

Figure 3(b1,b2)): one located at the corner and the other at the center. Regarding the particle alignment, the ellipsoids on one pair of adjacent sides orient perpendicular to the oscillating boundary, whereas those on the other two sides remain parallel to the stationary wall. The state at

A = 3.0 is characterized by two clearly separated orientational domains, shown in

Figure S3c. At an amplitude of

A = 4.5, the system forms a domain wall in coexistence with a parallel smectic phase (

Figure 3(c1)). The prominent feature is a global alignment of particles along the x-axis. However, a localized domain wall emerges adjacent to one wall, within which particles are aligned along the y-axis. Thus, a line defect separates the two regions of differently oriented particles in

Figure 3(c2). At even larger amplitude, a layered smectic phase forms with a director oriented diagonally at

. Meanwhile, particles in the outermost layer along the oscillating boundary exhibit a degree of disorder in both their orientation and position (

Figure 3(d1)). Defects can also be observed among the boundary particles aligned with the oscillation direction in

Figure 3(d2).

The

values reflecting the structural transitions show significant differences in

Figure 3e,f. For very small amplitudes in panel (e), the system retains a near-equilibrium configuration

. When the amplitude reaches

A = 1.0, the system undergoes a structural reorganization. This is accompanied by the reorientation of a group of particles to a direction perpendicular to the right oscillating boundary, yielding a global director angle of about

. Further increasing the amplitude leads to a distinct spatial organization: particles adjacent to two walls align perpendicular to the oscillating boundaries, whereas particles in the interior follow the right-diagonal direction. Notably, the orientational order parameter

remains at

throughout this stage, making the structure indistinguishable from the

phase based on

alone. Notably, configurations within this range are prone to instability. A distinct structural transition takes place at

A = 4.0, where the most particles align parallel to the x-axis, concurrently with the onset of disorder among boundary particles. Larger amplitude enhances disorder locally near the driven walls, while globally driving the system to collectively reorganize into a diagonally ordered state. This reconfiguration drives

to evolve from near

down toward

. The progression of

at

f = 1.0 (

Figure 3f) exhibits only two plateaus (from

to an unstable

), a direct consequence of the limited energy input under asymmetric driving. Consequently, the structural evolution is restricted to a sole transition from the diagonal nematic phase to a partially boundary-perpendicular phase.

3.4. Steady Pattern Under Three-Side Oscillation

The activation of three walls delivers high energy input and dramatically reduces symmetry, pushing the system into a near-fully agitated state. In this regime, cooperative multi-directional forcing promotes the formation of diverse structural configurations. Representative patterns and associated defect landscapes are illustrated in

Figure 4(a1–d1,a2–d2), respectively. At a frequency of 2.0 and amplitude of 1.0, the particles organize into a configuration (

Figure 4(a1)) similar to that shown in

Figure 3(a1), in which a subset of particles align perpendicular to the oscillating boundary. Isolated minor defects are distributed along the boundary, as illustrated in

Figure 4(a2). A further increase in amplitude leads to a structure that develops defect lines along the diagonal direction (

Figure 4(b2)). Particles at the top and right boundaries align perpendicular to their respective walls. In contrast, those on the left (adjacent to the stationary wall) and the majority at the bottom align parallel to the boundaries, as shown in

Figure 4(b1). This configuration exhibits relatively low stability, manifested by occasional inequality between the number of particles aligned along the y-axis and those aligned parallel to the x-axis. At a large amplitude (

A = 4.0), a structure aligned parallel to the x-axis emerges (

Figure 4(c1)). Defects are present on the left boundary due to a few particles aligning with the stationary wall, and also on the right boundary due to localized particle disorder, as shown in the

Figure 4(c2). In comparison to

Figure 3(c1), the enhanced energy input under triple-side oscillation diminishes the fixed boundary wall effect, resulting in fewer particles adopting a parallel alignment along the left wall. Under high-frequency driving (

f = 5.0,

A = 1.0), a central group of particles aligns diagonally, whereas most others orient perpendicular to the oscillating boundaries-with the exception of those along the fixed wall (

Figure 4(d1)). Additionally, two small defects are present in the central region (

Figure 4(d2)).

The evolution of the director angle

under two fixed-parameter driving conditions is presented in

Figure 4e,f. At a fixed frequency of

f = 2.0 (

Figure 4e), a small amplitude results in a diagonal alignment, yielding

. Upon increasing the amplitude to 1.0, particles adjacent to the right oscillating wall undergo a transition to perpendicular alignment, leading to an abrupt jump of

to

. However, this configuration is similarly unstable and is likely to evolve into a y-axis-aligned layered smectic phase, as shown in

Figure S4a. At amplitudes of 1.5 and 2.0, the system forms a tri-domain orientational structure with alignments along the y-axis, x-axis, and diagonal directions. However, the value of

in this configuration is not fixed, as the number of particles aligned parallel and perpendicular fluctuates. With a continued increase in amplitude, the structure transitions to being parallel to the x-axis, leading

to fluctuate near a value of

. With the amplitude fixed at

A = 1.0, the variation in frequency drives significant changes in

, as shown in

Figure 4f. The system evolves through distinct phases: it begins with a near-equilibrium state (

) for

, and then separates into three orientational domains for

, which reduces

. This intermediate state is metastable, and the configuration at

f = 3.0,

A = 1.0 is illustrated in

Figure S4c. Following the stabilization at

f = 4.0, a further increase in driving frequency raises the energy input. This increase reinforces perpendicular alignment at the boundaries and amplifies the proportion of particles along the y-axis, consequently steering

toward zero.

3.5. Steady Pattern Under Four-Side Oscillation

Four-side global oscillation delivers both maximal symmetry and high energy input, leading to strong isotropic disturbances. Thus, the emergence of order is determined by the drive parameters’ ability to elicit coherent collective behavior from the system. This results in a remarkable diversity of configurations. To illustrate,

Figure 5 presents four representative snapshots (a1–d1) alongside their corresponding defect landscapes (a2–d2) under full-wall oscillation. Under the conditions

f = 2.0 and

A = 1.0, a tilted smectic-like phase (

Figure 5(a1)) forms, exhibiting no observable defects in its corresponding landscape (

Figure 5(a2)). At an amplitude of 2.0, the system undergoes a diagonal split, resulting in a symmetric two-domain structure (

Figure 5(b1)): left-side particles align with the y-axis, right-side particles with the x-axis, and only a few central particles retain diagonal orientation. This state, labeled

, exhibits defects along one diagonal, as seen in

Figure 5(b2). At an amplitude of 3.5, the system formed a core-shell structure (

Figure 5(c1)), with internal particles aligned diagonally and a disordered outer shell. This disordered shell corresponds to the numerous defects observed in

Figure 5(c2). When driven at high-frequency

f = 5.0 and

A = 1.0, the system adopts an X-shaped morphology (

Figure 5(d1)). Particles adjacent to each wall orient perpendicular to it, resulting in a combination of alignments along the x, y, and two diagonal axes. This configuration gives rise to two well-defined defects at its center, visible in

Figure 5(d2).

When the frequency is fixed at

f = 2.0, amplitude modulation under global (four-side) oscillation generates four distinct structural phases. The evolution among these phases is captured by the director angle

, whose value oscillates between

and 0 presented in

Figure 5e. At small amplitudes below 1.0, the particles first adopt a near-equilibrium structure with

. When the amplitude is increased to 1.0 and 1.5, a smectic-like structure tilted with respect to the y-axis emerges, accompanied by

. As the amplitude reaches 2.0,

returns to

, while the system transitions into a symmetric defect architecture with defects aligned along the diagonal direction. At amplitudes of 2.5 and 3.0, a layered smectic-like phase aligned along the y-axis develops, resulting in

. Further increasing the amplitude to 3.5 leads to the formation of a diagonal core-shell structure. Beyond this point, continued amplification causes a growing number of disordered particles at the boundaries, corresponding to a gradual decrease in

. At

f = 1.0 (

Figure 5f),

exhibits a step-like variation, shifting from

to 0 and back. This progression characterizes the structural transition from the near-equilibrium

phase, to the

phase, and finally to the X-shaped

structure. However,

alone remains insufficient to clearly distinguish these three phases.

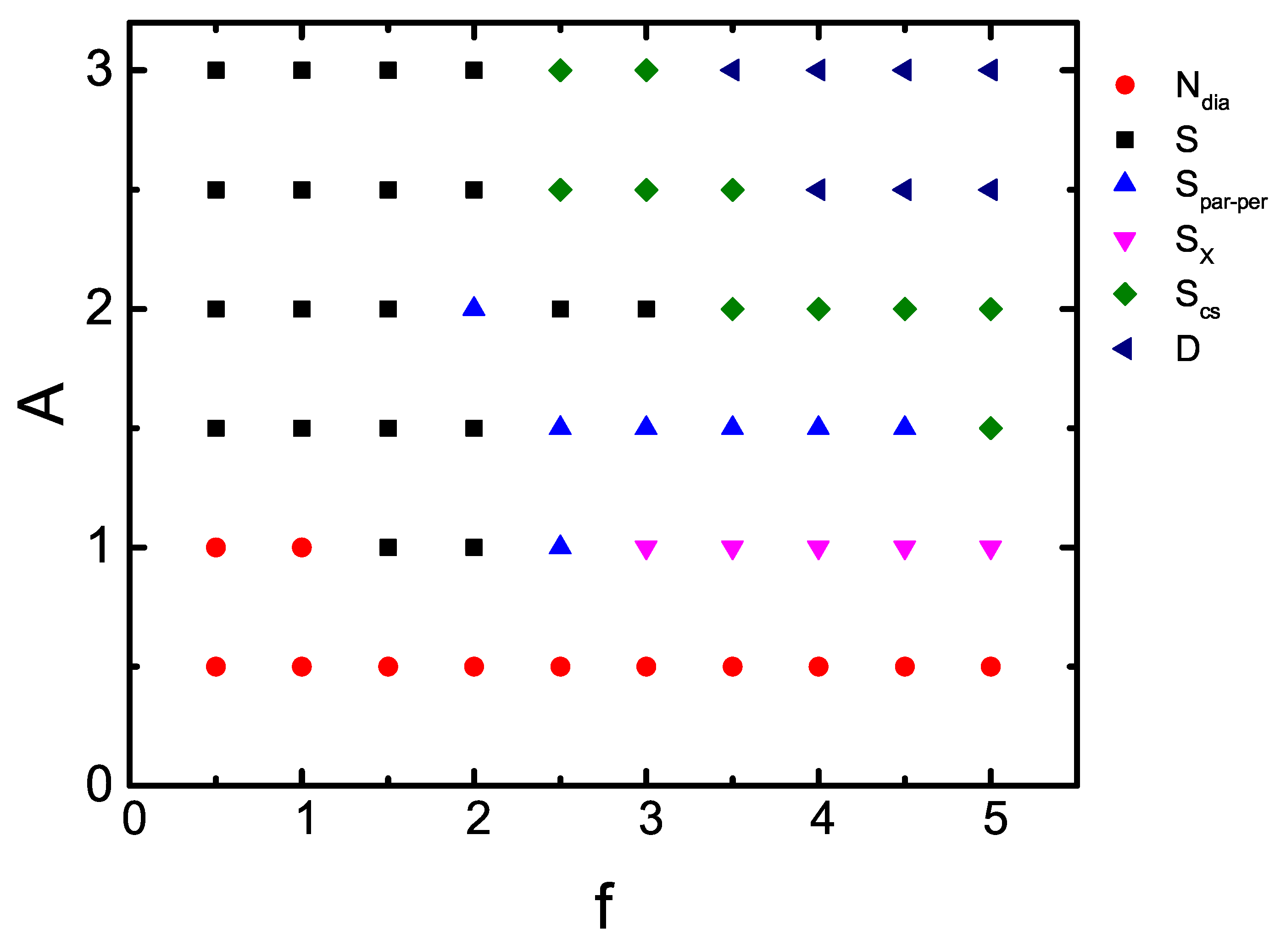

Figure 6 shows the structural phase diagram in frequency–amplitude space, revealing how four-side oscillation governs self-organization under periodic driving. Under weak oscillatory driving (small amplitude and frequency), a near-equilibrium structure emerges, with particles tending to accumulate in the interior due to the boundary motion. Further increase in either amplitude or frequency give rise to out-of-equilibrium steady structures, in which the collective motion of the confined ellipsoids plays a dominant role. Since this study focuses on such steady structures, the amplitude was limited in the range from 0 to 3. Within the investigated parameter space, six distinct phases are identified: a diagonal phase (

), a smectic-like phase with layer normal along the y-axis (

S), a mixed-orientation smectic-like phase (

), an X-shaped configuration oriented perpendicular to the boundaries (

), a core–shell structure with ordered core and disordered shell (

), and an orientationally and translationally disordered phase (D). Due to high energy input under strong driving (large amplitude or high frequency), intensified boundary agitation breaks down collective motion, giving way to a disordered and liquid-like state.