A Fast-Response Vertical-Alignment In-Plane-Switching-Mode Liquid Crystal Display

Abstract

1. Introduction

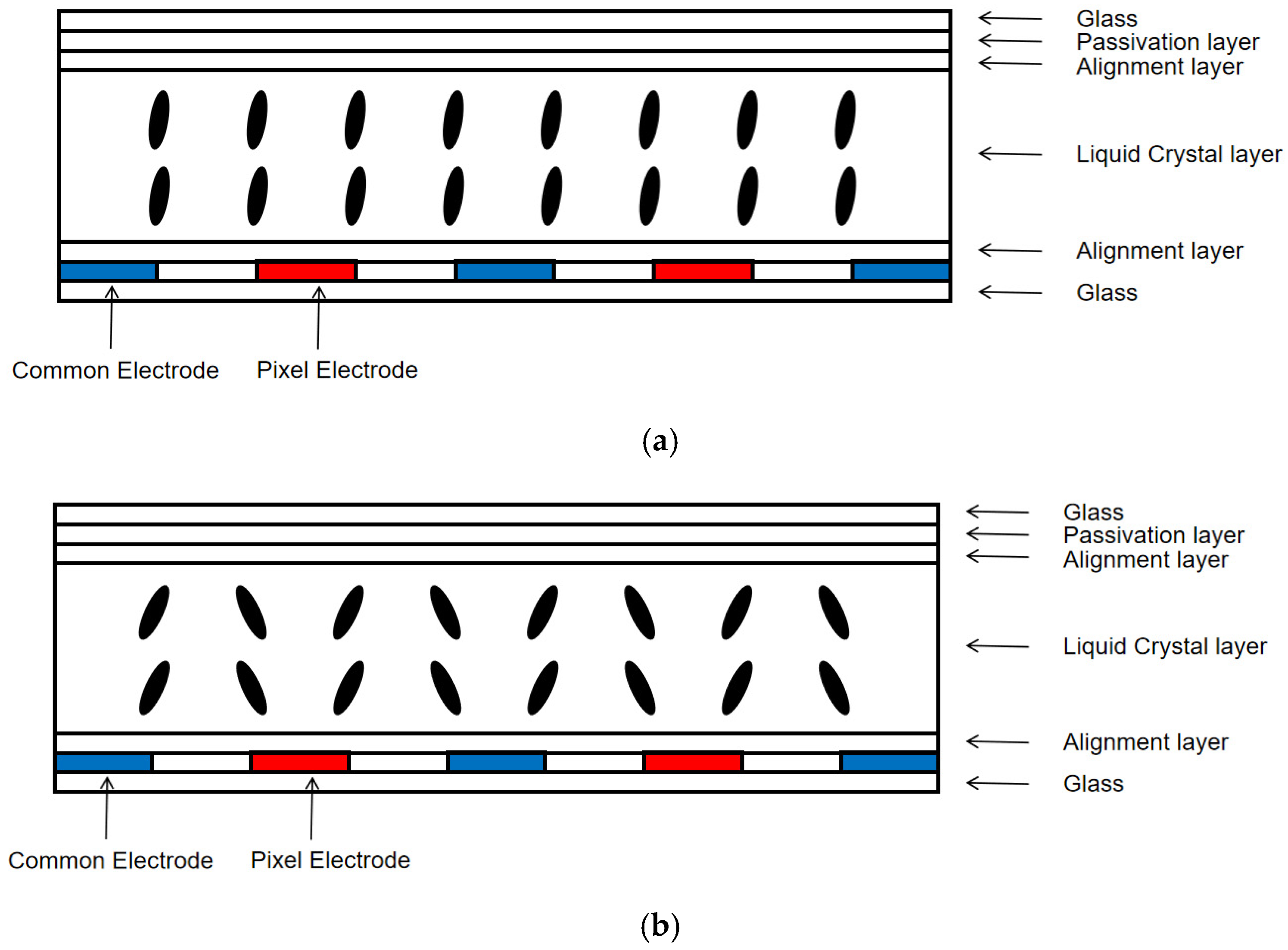

2. Materials and Methods

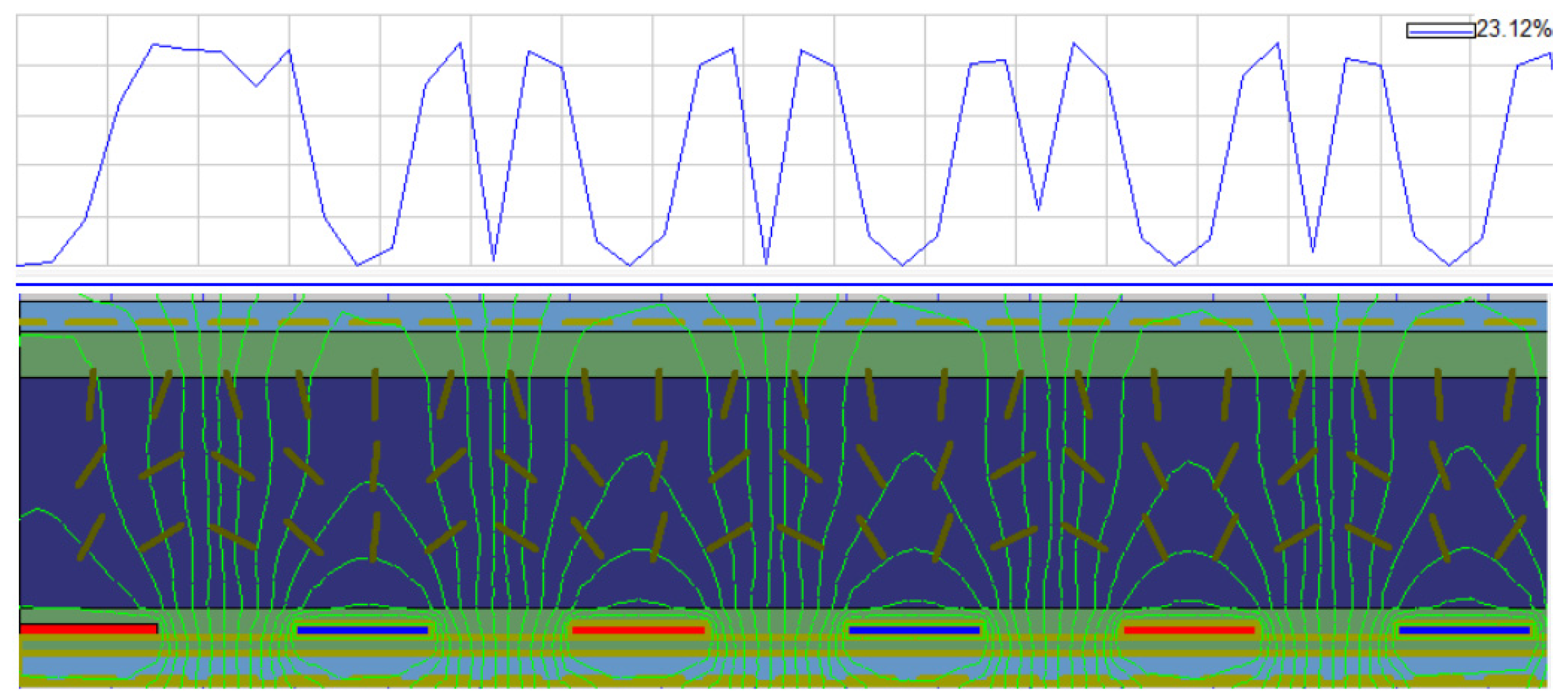

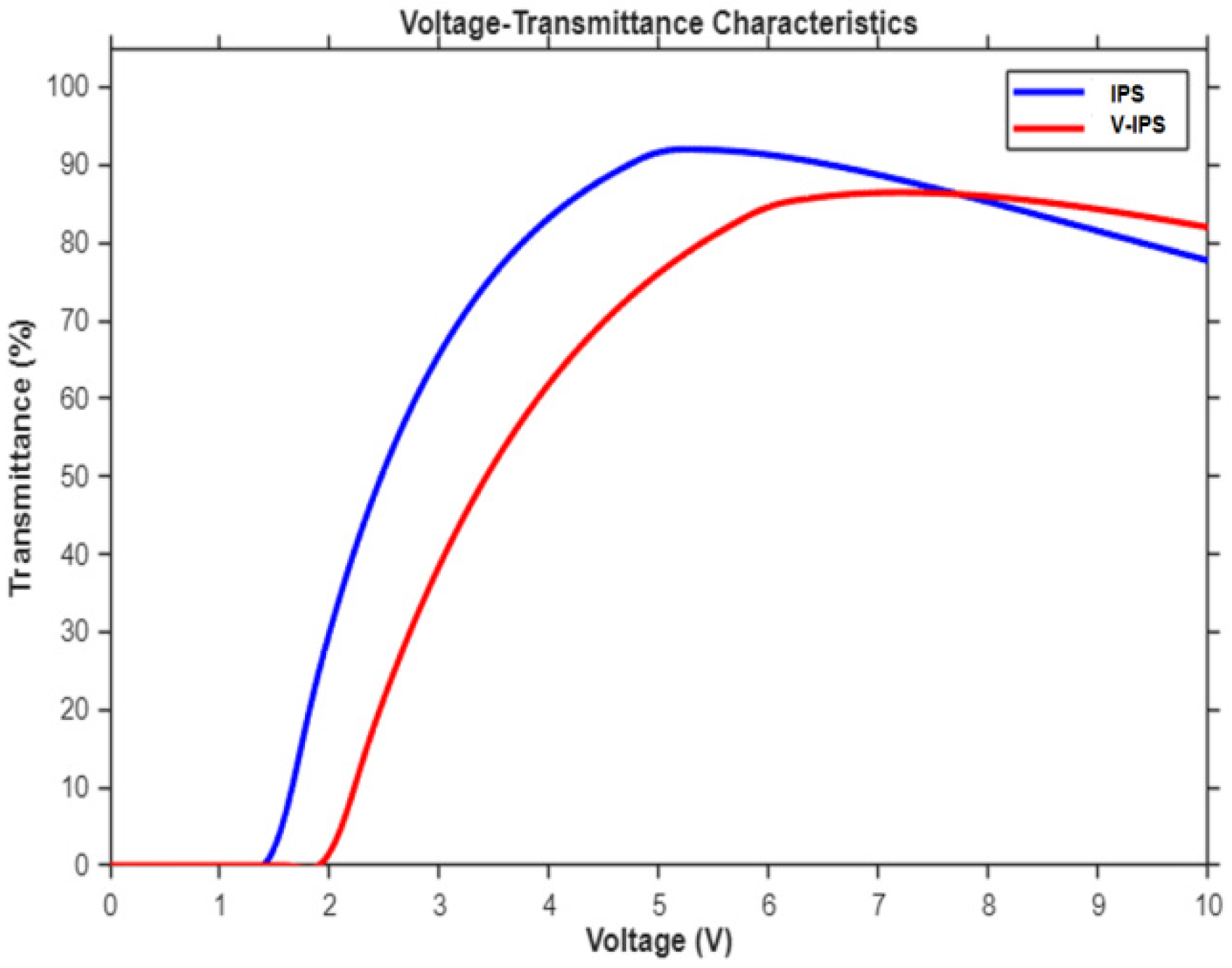

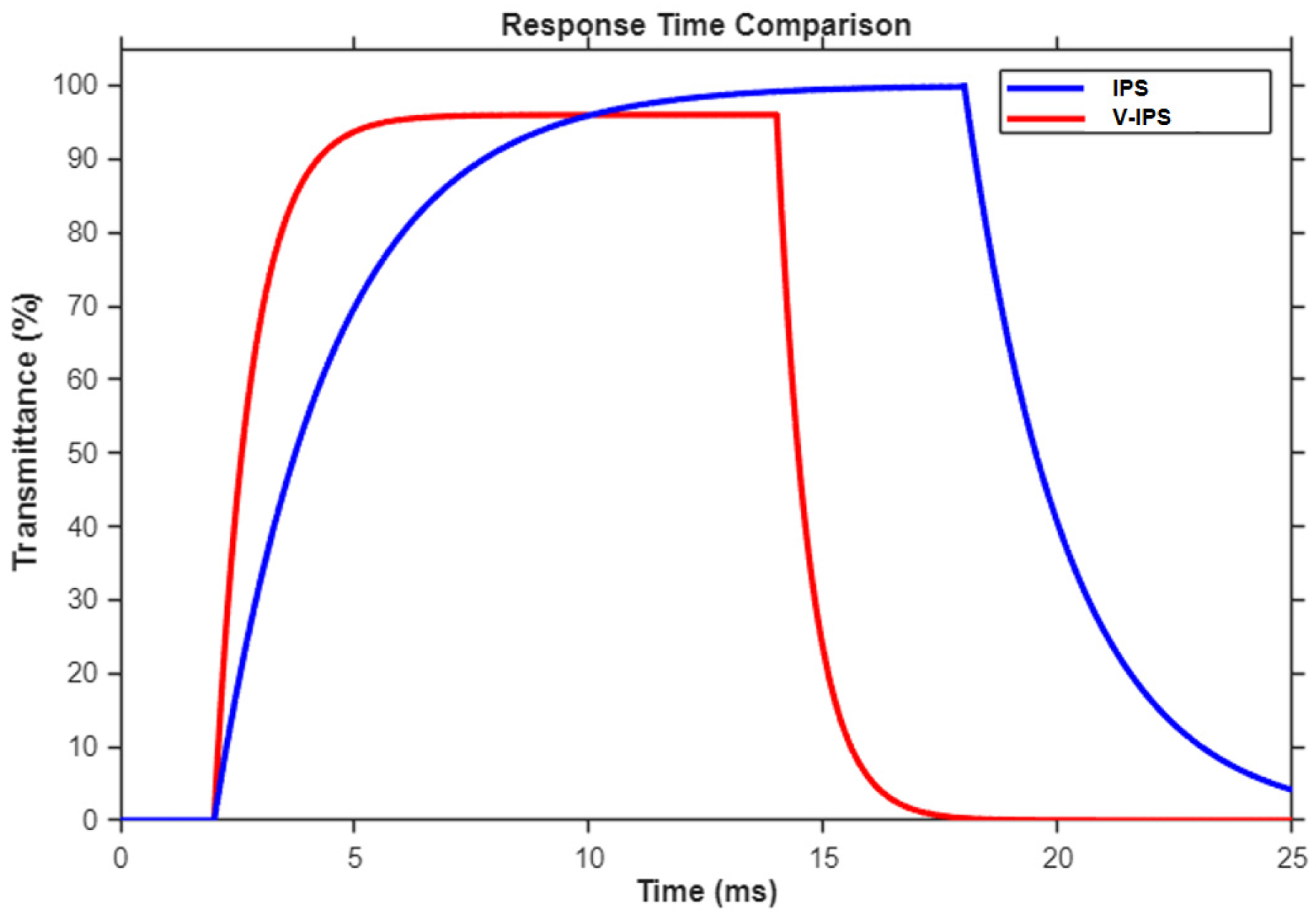

3. Simulation

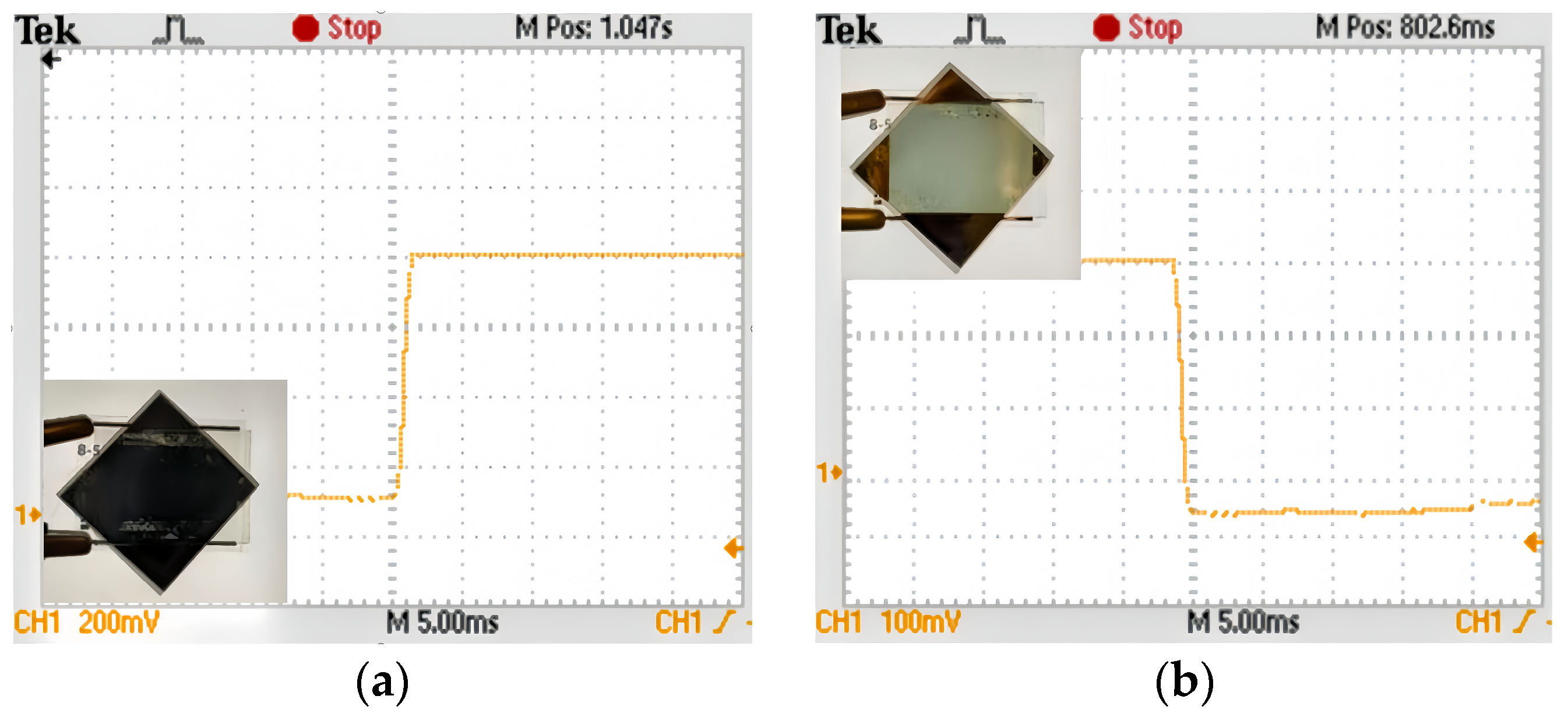

4. Experimental Results and Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LC | Liquid Crystal |

| LCDs | Liquid Crystal Displays |

| NLCs | Nematic Liquid Crystals |

| OCB | Optically Compensated Bend |

| BPLCs | Blue Phase Liquid Crystals |

| FLCs | Ferroelectric Liquid Crystals |

| V-IPS | Vertical-alignment In-Plane Switching |

| IPS | In-Plane Switching |

| VA | Vertical Alignment |

| GTG | Grayscale-To-Grayscale |

References

- Jo, S.I.; Yoon, S.-S.; Park, S.R.; Lee, J.-H.; Jun, M.-C.; Kang, I.-B. 44-2: Invited Paper: Fast Response Time Advanced High Performance In-plane Switching (AH-IPS) Mode for High Resolution Application. SID Symp. Dig. Tech. Pap. 2018, 49, 581–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Z.B.; Rao, L.H.; Gauza, S.; Wu, S.T. High birefringence liquid crystals for fast switching applications. J. Disp. Technol. 2009, 5, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, C.-H.; Cho, T.-Y.; Tsai, S.-C.; Chiu, C.-Y.; Chen, T.-S.; Lin, H.-C.; Su, J.-J.; Lien, A. Performance analysis of in-plane switching mode with low viscosity mixtures. J. Soc. Inf. Disp. 2010, 18, 960–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Z.; Gauza, S.; Jiao, M.; Xianyu, H.; Wu, S.-T. Electro-optics of polymer-stabilized blue phase liquid crystal displays. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2009, 94, 101104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.F.; Wang, H.; He, W.L.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Zhang, L.; Yang, Z.; Cao, H.; Wang, D.; Li, Y.Z. Advances in blue-phase liquid crystal network polymers and their applications. Liq. Cryst. Disp. 2022, 37, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Q.; Yan, K.; Chigrinov, V.; Zhao, H.; Tribelsky, M. Ferroelectric Liquid Crystals: Physics and Applications. Crystals 2019, 9, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudreyko, A.; Lapanik, V.; Chigrinov, V. Investigation of anchoring effects in ferroelectric liquid crystals. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2025, 717, 417761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toshiharu, M.; Shunichi, K. Development of Fast Response IPS mode. In Proceedings of Japanese Liquid Crystal Society Annual Meeting; The Japanese Liquid Crystal Society: Tokyo, Japan, 2021; p. 1CS3. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.H.; Lee, S.L.; Kim, H.Y. A New Liquid-Crystal Display Operated by a Fringe-Field Switching. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1998, 73, 2881. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F.; Chou, R.; Chuang, S.; Huang, L.; Guo, L.; Li, D. 31-1: Invited Paper: C-PS-VA and SA-VA—Technologies for Next Generation TV LCDs. SID Symp. Dig. Tech. Pap. 2024, 55, 394–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.R.; Choi, W.K. Fast-Response FFS LC Device with Multi-rubbing Angle for VR Applications. SID Int. Symp. 2024, 55, 2075–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.K.; Tseng, B.K.; Tung, C.H. P-172: A New Fast-Response VA-FFS LC Device Using Three-Electrode Design with Improved Transmission for VR Applications. SID Symp. Dig. Tech. Pap. 2025, 56, 2111–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakanishi, Y.; Shibasaki, M.; Hanaoka, K.; Inoue, Y.; Tarumi, K.; Bremer, M.; Klasen-Memmer, M.; Greenfield, S.; Harding, R. Liquid Crystal Composition and Display Device. U.S. Patent 7,169,449, 30 January 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Miyashita, T.; Uchida, T. Optically Compensated Bend Mode(OCB Mode) with Wide Viewing Angle and Fast Response. Ieice Trans. Electron. 1996, 79, 1076–1082. [Google Scholar]

- Scheffer, T.J.; Clifton, B. Active addressing method for high contrast video rate STN displays. Sid92 Symp Dig. 1992, 228–231. [Google Scholar]

- Nose, T.; Suzuki, M.; Saski, D.; Imai, M.; Hayama, H. A black stripedriving scheme for displaying motion pictures on LCDs. SID Symp. Dig. Tech Pap. 2001, 32, 994–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, L.; Chen, C.; Huang, Y.; Yeh, S. 57.4: Fast MPRT with High Brightness LCD by 120Hz Local Blinking HDR Systems. SID Symp. Dig. Tech. Pap. 2009, 40, 862–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh, G.; Mishima, N. Novel frame interpolation method for highimage quality LCDs. J. Inf. Disp. 2004, 5, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klompenhouwer, M.A.; Velthoven, L.J. Motion blur reduction for liquidcrystal displays: Motion compensated inverse filtering. In Visual Communications and Image Processing 2004; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2004; Volume 5308. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Wang, J.; Wu, L.; Hu, W. Research Progress and Prospect of Ultrafast Response Liquid Crystal Technology. Liq. Cryst. Disp. 2025, 40, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, F.; Gou, F.; Chen, H.; Huang, Y.; Wu, S. A submillisecond-response liquid crystal for color sequential projection displays. J. Soc. Inf. Disp. 2016, 24, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Kim, H.Y.; Park, I.C.; Rho, B.G.; Park, J.S.; Park, H.S.; Lee, C.H. Rubbing-free, vertically aligned nematic liquid crystal display controlled by in-plane field. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1997, 71, 2851–2853. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, X.; Lu, R.; Xianyu, H.; Wu, T.X.; Wu, S.-T. Anchoring energy and cell gap effects on liquid crystal response time. J. Appl. Phys. 2007, 101, 103110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Δn (589 nm, 25 °C) | 0.142 |

| ne (589 nm, 25 °C) | 1.640 |

| no (589 nm, 25 °C) | 1.498 |

| Δε (1 kHz, 25 °C) | 4.2 |

| ε∥ (1 kHz, 25 °C) | 7.0 |

| ε⊥ (1 kHz, 25 °C) | 2.8 |

| K11 (25 °C) | 13.6 |

| K22 (25 °C) | 8.2 |

| K33 (25 °C) | 14.2 |

| γ1 (25 °C) | 46 |

| V-IPS (G = 5 μm) | V-IPS (G = 4 μm) | V-IPS (G = 3 μm) | IPS (G = 3 μm) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rising time | 5.1 ms | 3.9 ms | 2.9 ms | 4.1 ms |

| Falling time | 2.4 ms | 2.0 ms | 1.7 ms | 7.8 ms |

| Transmittance | 23.3% | 23.1% | 22.9% | 23.9% |

| Pretilt Angles | 90° | 89° | 88° | 87° | 86° | 85° |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rising time | 3.3 ms | 3.0 ms | 2.9 ms | 2.9 ms | 2.9 ms | 2.9 ms |

| Falling time | 1.8 ms | 1.7 ms | 1.7 ms | 1.7 ms | 1.7 ms | 1.7 ms |

| Transmittance | 22.9% | 22.9% | 22.9% | 22.9% | 22.8% | 22.8% |

| Viewing Angle | 0° | +30° | +60° | −30° | −60° |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPS | 100% | ≈75% | ≈30% | ≈75% | ≈30% |

| V-IPS | 100% | ≈40% | ≈10% | ≈40% | ≈10% |

| Viewing Angle | 0° | +30° | +60° | −30° | −60° |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPS | 100% | ≈70% | ≈20% | ≈70% | ≈20% |

| V-IPS | 100% | ≈25% | ≈10% | ≈25% | ≈10% |

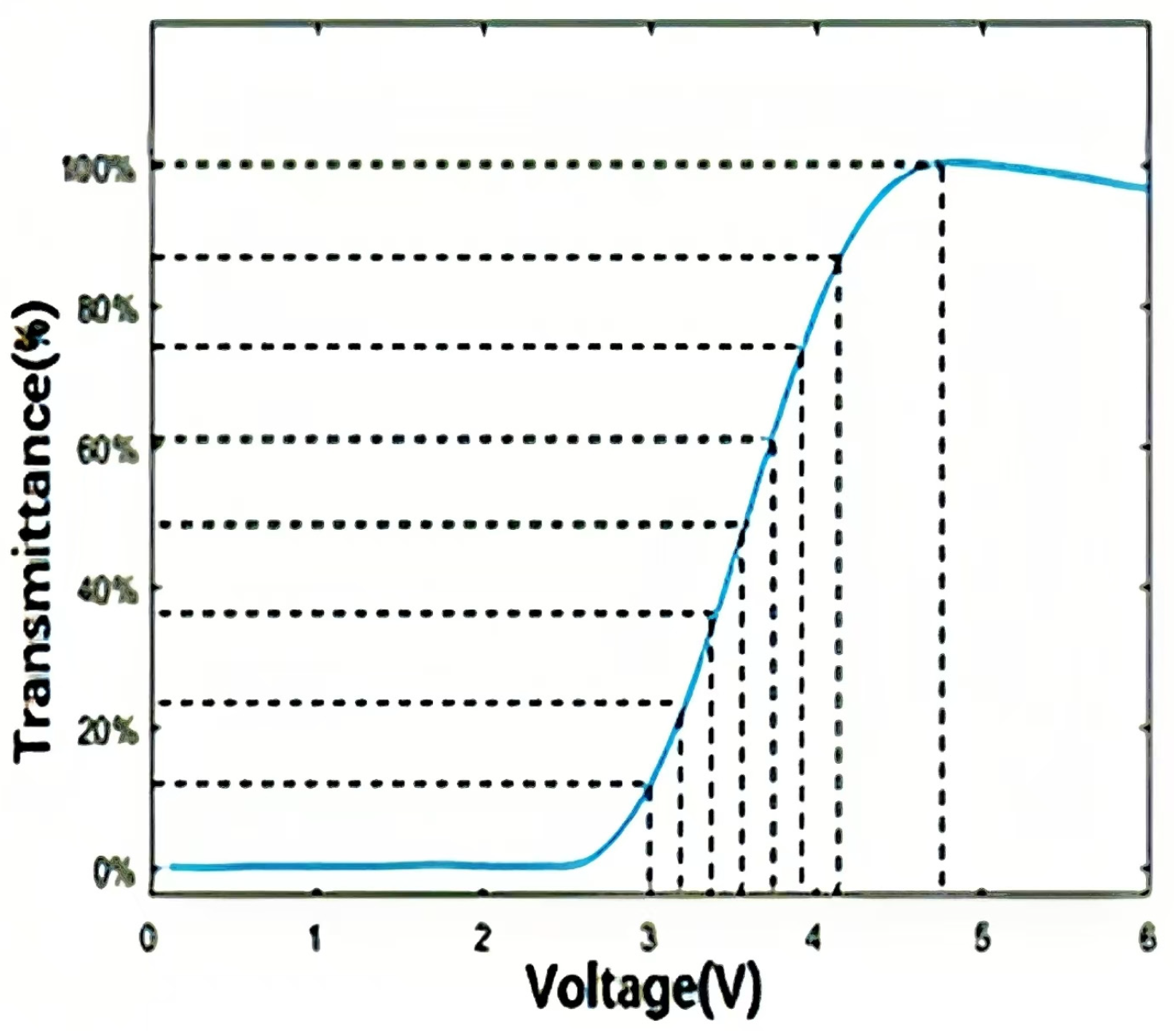

| Grayscale | Voltage (V) |

|---|---|

| 0 | 0 |

| 31 | 1.8 |

| 63 | 2.3 |

| 95 | 2.7 |

| 127 | 3.1 |

| 159 | 3.5 |

| 191 | 4 |

| 223 | 4.6 |

| 255 | 6.2 |

| Start Voltage (V) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| End voltage (V) | 0 | 1.8 | 2.3 | 2.7 | 3.1 | 3.5 | 4 | 4.6 | 6.2 | |

| 0 | N/A | 1.8 ms | 2.8 ms | 1.6 ms | 1.4 ms | 1.7 ms | 1.9 ms | 1.5 ms | 1.8 ms | |

| 1.8 | 3.6 ms | N/A | 2.6 ms | 1.4 ms | 1.5 ms | 1.4 ms | 1.8 ms | 1.7 ms | 1.8 ms | |

| 2.3 | 3.2 ms | 2.7 ms | N/A | 2.3 ms | 1.9 ms | 1.1 ms | 1.4 ms | 1.6 ms | 1.7 ms | |

| 2.7 | 4.5 ms | 4.2 ms | 3.8 ms | N/A | 2.1 ms | 1.9 ms | 1.2 ms | 1.4 ms | 2.0 ms | |

| 3.1 | 4.2 ms | 4 ms | 4.2 ms | 4 ms | N/A | 2.6 ms | 1.8 ms | 1.3 ms | 1.9 ms | |

| 3.5 | 3.3 ms | 3.8 ms | 4.1 ms | 3.3 ms | 2.2 ms | N/A | 1.4 ms | 1.2 ms | 2.3 ms | |

| 4 | 4.1 ms | 4.2 ms | 4.2 ms | 2.5 ms | 2 ms | 2.4 ms | N/A | 1.8 ms | 2 ms | |

| 4.6 | 3.6 ms | 3.1 ms | 3.8 ms | 2.1 ms | 2.1 ms | 2.1 ms | 2.6 ms | N/A | 2.1 ms | |

| 6.2 | 1.7 ms | 1.8 ms | 1.9 ms | 1.6 ms | 1.4 ms | 1.9 ms | 1.6 ms | 1.2 ms | N/A | |

| Grayscale | Voltage (V) | Overdrive Voltage (V) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 31 | 1.8 | 2.5 |

| 63 | 2.3 | 3 |

| 95 | 2.7 | 3.5 |

| 127 | 3.1 | 3.5 |

| 159 | 3.5 | 4 |

| 191 | 4 | 4.5 |

| 223 | 4.6 | 5 |

| 255 | 6.2 | 6.5 |

| Start Voltage (V) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1.8 | 2.3 | 2.7 | 3.1 | 3.5 | 4 | 4.6 | 6.2 | ||

| End voltage (V) | 0 | N/A | 1.8 ms | 2.8 ms | 1.6 ms | 1.4 ms | 1.7 ms | 1.9 ms | 1.5 ms | 1.8 ms |

| 1.8 | 0.9 ms | N/A | 2.6 ms | 1.4 ms | 1.5 ms | 1.4 ms | 1.8 ms | 1.7 ms | 1.8 ms | |

| 2.3 | 0.9 ms | 0.8 ms | N/A | 2.3 ms | 1.9 ms | 1.1 ms | 1.4 ms | 1.6 ms | 1.7 ms | |

| 2.7 | 1 ms | 1 ms | 0.8 ms | N/A | 2.1 ms | 1.9 ms | 1.2 ms | 1.4 ms | 2.0 ms | |

| 3.1 | 1 ms | 1.1 ms | 0.9 ms | 0.6 ms | N/A | 2.6 ms | 1.8 ms | 1.3 ms | 1.9 ms | |

| 3.5 | 1.1 ms | 1.2 ms | 0.9 ms | 0.8 ms | 0.7 ms | N/A | 1.4 ms | 1.2 ms | 2.3 ms | |

| 4 | 1 ms | 0.9 ms | 1 ms | 0.9 ms | 0.8 ms | 0.7 ms | N/A | 1.8 ms | 2 ms | |

| 4.6 | 1.2 ms | 1.1 ms | 1.1 ms | 1.2 ms | 0.9 ms | 0.8 ms | 0.6 ms | N/A | 2.1 ms | |

| 6.2 | 0.9 ms | 1.3 ms | 0.8 ms | 1.2 ms | 1.2 ms | 1.5 ms | 1.6 ms | 1.2 ms | N/A | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jiang, F.; Lu, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, K.; Li, W. A Fast-Response Vertical-Alignment In-Plane-Switching-Mode Liquid Crystal Display. Crystals 2026, 16, 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16010076

Jiang F, Lu J, Li Y, Wang J, Chen K, Li W. A Fast-Response Vertical-Alignment In-Plane-Switching-Mode Liquid Crystal Display. Crystals. 2026; 16(1):76. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16010076

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Feng, Jiangang Lu, Yi Li, Jing Wang, Kefeng Chen, and Wei Li. 2026. "A Fast-Response Vertical-Alignment In-Plane-Switching-Mode Liquid Crystal Display" Crystals 16, no. 1: 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16010076

APA StyleJiang, F., Lu, J., Li, Y., Wang, J., Chen, K., & Li, W. (2026). A Fast-Response Vertical-Alignment In-Plane-Switching-Mode Liquid Crystal Display. Crystals, 16(1), 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16010076