Pb-Apatite Framework as a Generator of Novel Flat-Band CuO-Based Physics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

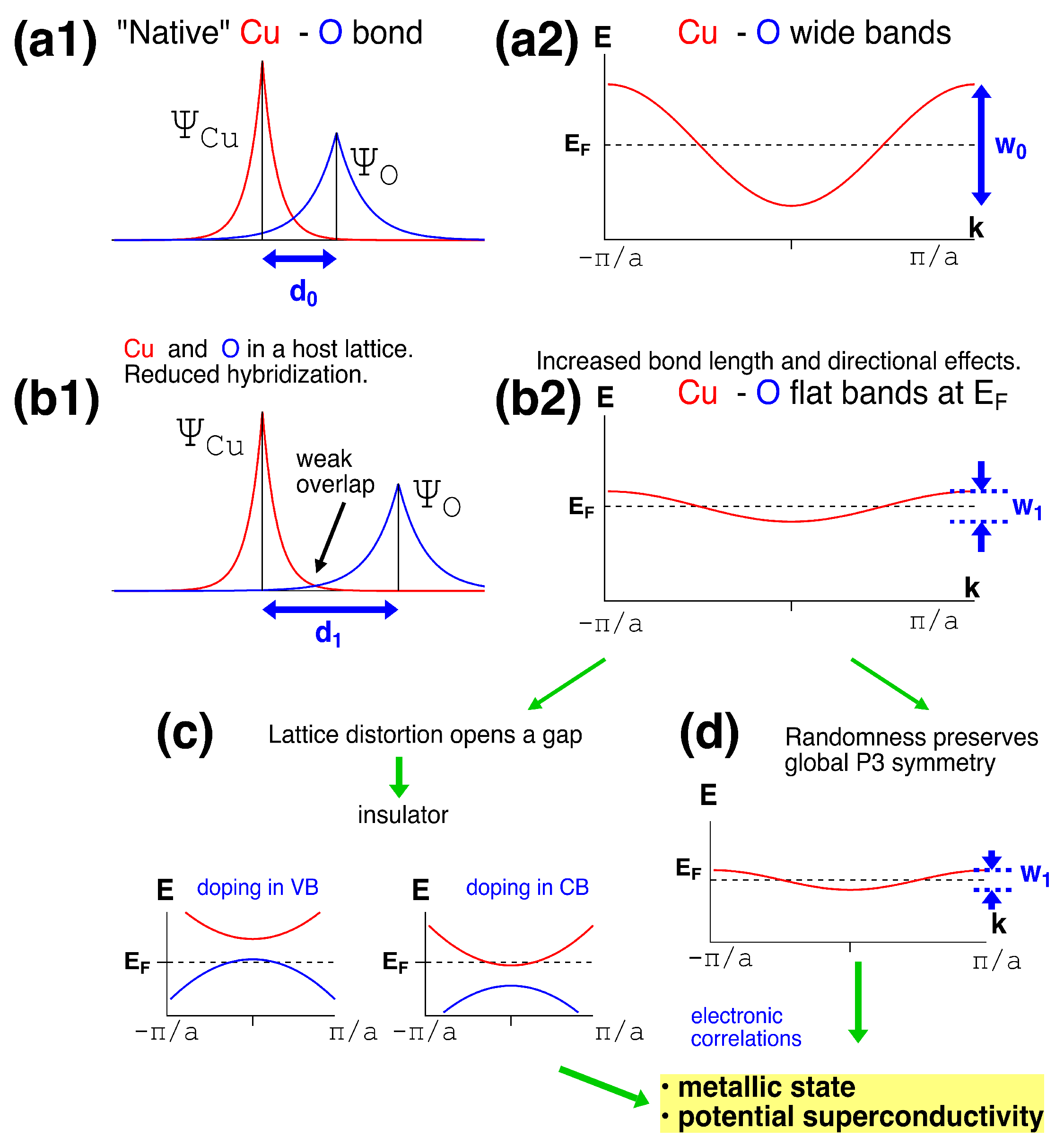

3. Results

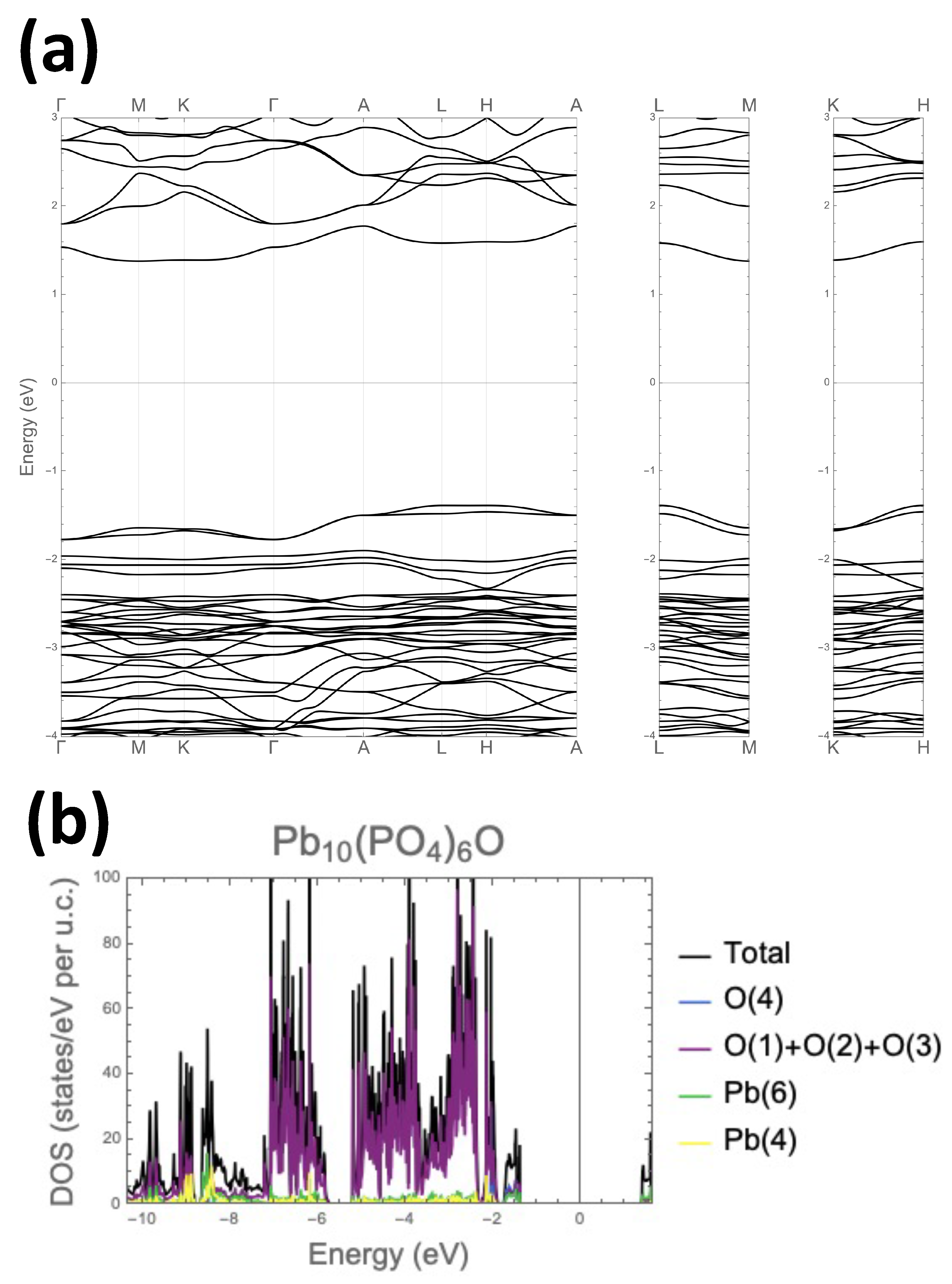

3.1. Crystal and Electronic Structure of the Parent Compound Pb10(PO4)6O

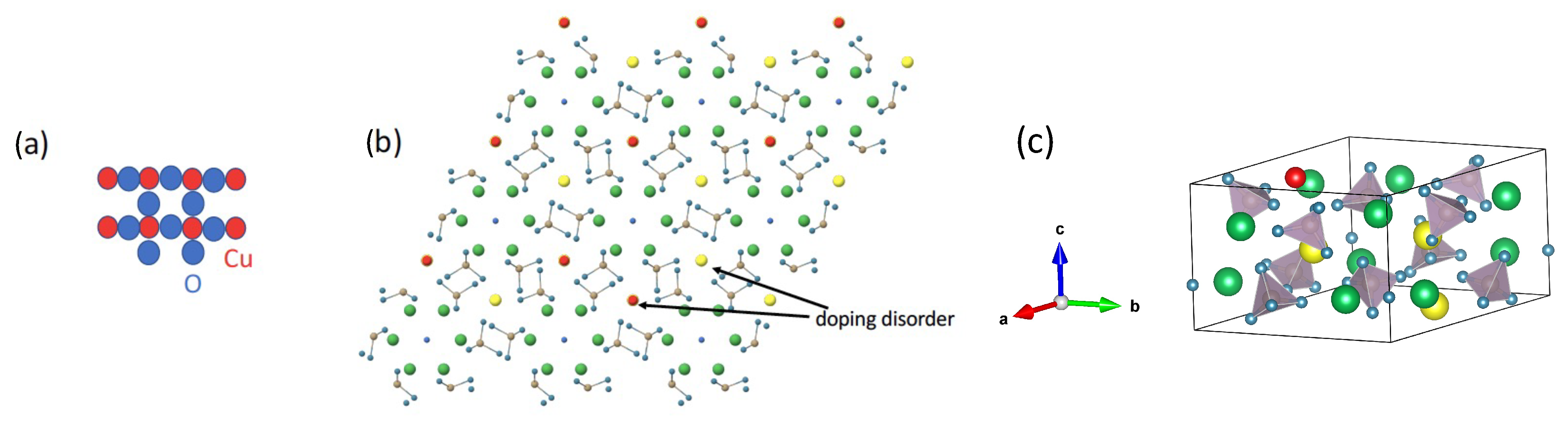

3.2. Crystal Structure of CuPb9(PO4)6O

3.3. Total Energy Calculations

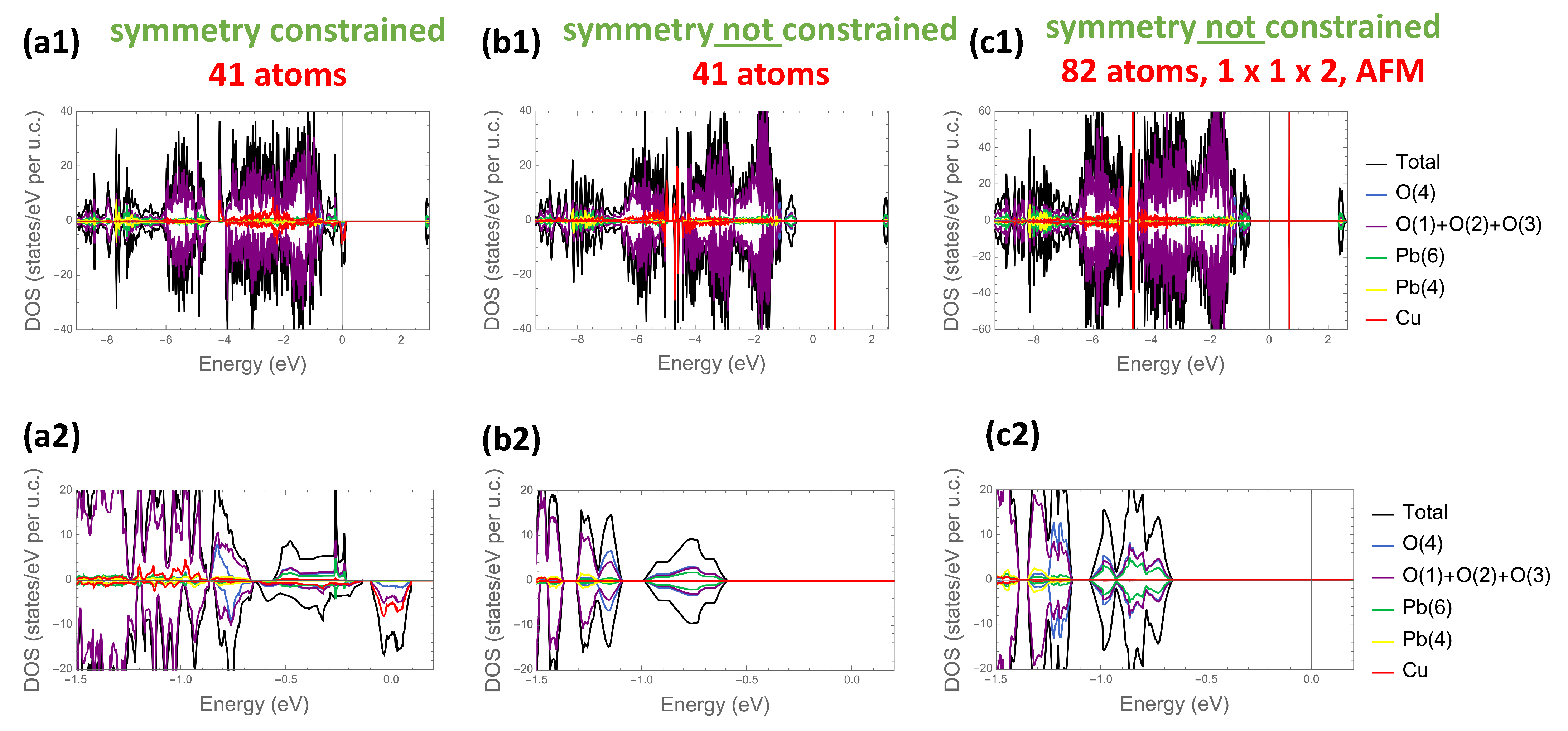

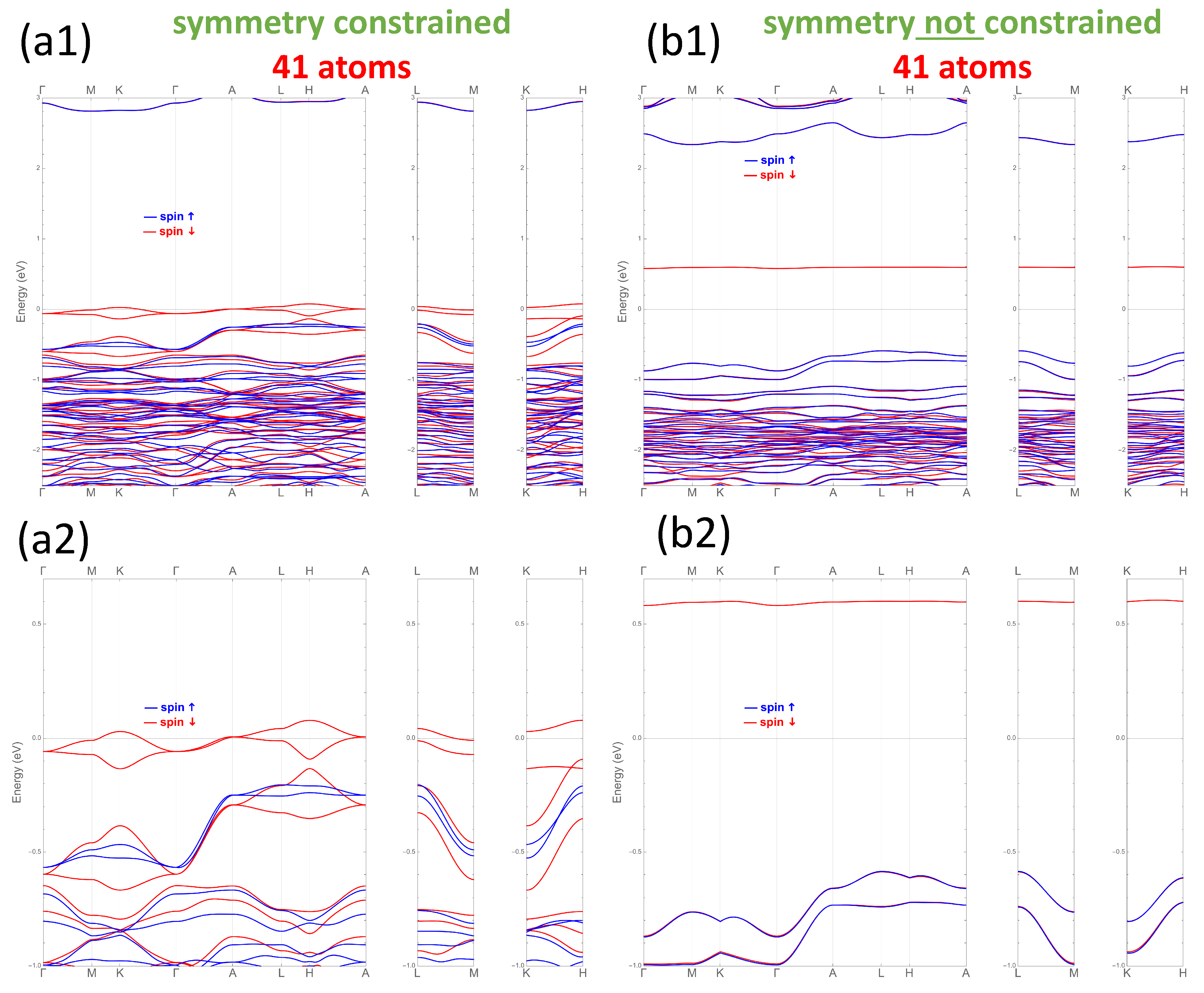

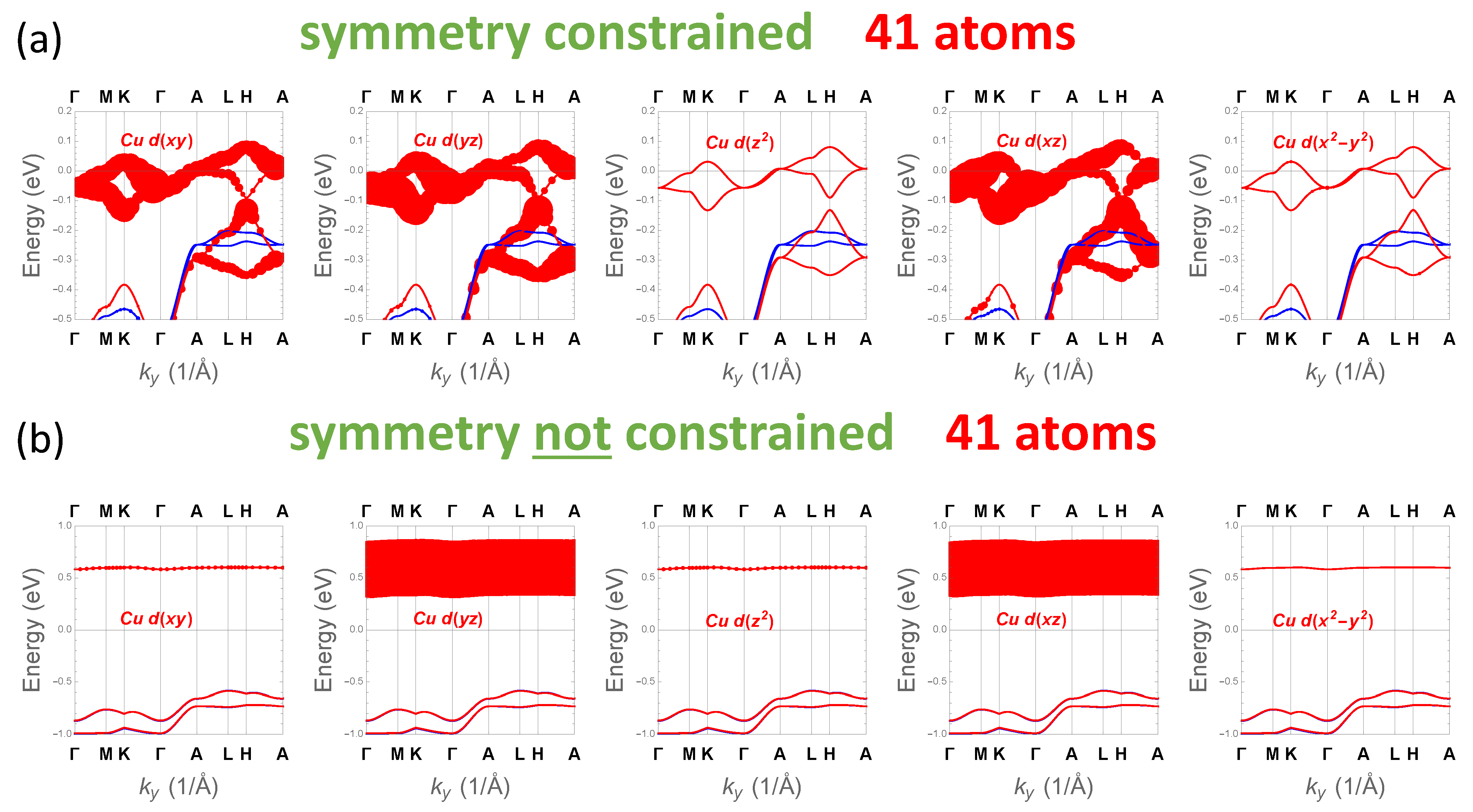

3.4. Electronic Structure Properties

4. Discussion and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LK-99 | CuPb9(PO4)6O, Cu-doped lead apatite |

| DOS | Density of states |

| DFT | Density functional theory |

| MC | Monte-Carlo |

| GGA | Generalized gradient approximation |

| SCAN | Strongly constrained and appropriately normed |

| AF | Anti-ferromagnetic |

| FM | Ferromagnetic |

| PAW | Projector-augmented wave |

| PBE | Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof |

| fu | Formula unit |

| sb | Symmetry-broken |

| sc | Symmetry-constrained |

References

- Griffin, S.M. Origin of correlated isolated flat bands in copper-substituted lead phosphate apatite. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.16892. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lai, J.; Li, J.; Liu, P.; Sun, Y.; Chen, X.Q. First-principles study on the electronic structure of Pb10−xCux(PO4)6O (x = 0, 1). J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2023, 171, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korotin, D.M.; Novoselov, D.Y.; Shorikov, A.O.; Anisimov, V.I.; Oganov, A.R. Electronic correlations in the ultranarrow energy band compound Pb9Cu(PO4)6O: A DFT+DMFT study. Phys. Rev. B 2023, 108, L241111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, L.; Wallerberger, M.; Smolyanyuk, A.; di Cataldo, S.; Tomczak, J.M.; Held, K. Pb10−xCux(PO4)6O: A Mott or charge transfer insulator in need of further doping for (super)conductivity. J. Phys.-Condens. Matter 2024, 36, 065601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, C.; Christiansson, V.; Werner, P. Correlated electronic structure of Pb10−xCux(PO 4)6O. Phys. Rev. B 2023, 108, L201122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, L.; Fu, E. First-principles calculation on the electronic structures, phonon dynamics, and electrical conductivities of Pb10(PO4)6O and Pb9Cu(PO4)6O compounds. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2024, 173, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, L.; Held, K. Electronic structure of the putative room-temperature superconductor Pb9Cu(PO4)6O. Phys. Rev. B 2023, 108, L121110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puphal, P.; Akbar, M.Y.P.; Hepting, M.; Goering, E.; Isobe, M.; Nugroho, A.A.; Keimer, B. Single crystal synthesis, structure, and magnetism of Pb10−xCux(PO4)6O. APL Mater. 2023, 11, 101128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, J.H.; Kwon, Y.W. The First Room-Temperature Ambient-Pressure Superconductor. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.12008. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Kim, J.; Kim, H.T.; Im, S.; An, S.; Auh, K.H. Superconductor Pb10−xCux(PO4)6O showing levitation at room temperature and atmospheric pressure and mechanism. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.12037. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, K.; KARN, N.K.; Awana, V.S. Synthesis of possible room temperature superconductor LK-99: Pb9Cu(PO4)6O. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2023, 36, 10LT02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Wu, W.; Li, Z.; Luo, J. First-order transition in LK-99 containing Cu2S. Matter 2023, 6, 4401–4407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgescu, A.B. Why Charge Added Using Transition Metals to Some Insulators, Including LK-99, Localizes and Does Not Yield a Metal. Chem. Mater. 2025, 37, 1847–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Yang, L.; Yu, J.; Zhang, G.; Xiao, B.; Chang, H. Observation of abnormal resistance-temperature behavior along with diamagnetic transition in Pb10−xCux(PO4)6O-based composite. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.05001. [Google Scholar]

- Bednorz, J.; Muller, K. Possible high-Tc Superconductivity in the Ba-La-Cu-O system. Z. Phys. B-Condens. Matter 1986, 64, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.C.; Rice, T.M. Effective Hamiltonian for the superconducting Cu oxides. Phys. Rev. B 1988, 37, 3759–3761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pashov, D.; Acharya, S.; Lany, S.; Dessau, D.S.; van Schilfgaarde, M. Multiple Slater determinants and strong spin-fluctuations as key ingredients of the electronic structure of electron- and hole-doped Pb10−xCux(PO4)6O. Crystals 2025, 15, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, P. Theory of dirty superconductors. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 1959, 11, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdew, J.P.; Burke, K.; Ernzerhof, M. Generalized Gradient Approximation Made Simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865–3868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudarev, S.L.; Botton, G.A.; Savrasov, S.Y.; Humphreys, C.J.; Sutton, A.P. Electron-energy-loss spectra and the structural stability of nickel oxide: An LSDA+U study. Phys. Rev. B 1998, 57, 1505–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Ruzsinszky, A.; Perdew, J.P. Strongly Constrained and Appropriately Normed Semilocal Density Functional. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2015, 115, 036402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kresse, G.; Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 1999, 59, 1758–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krivovichev, S.V.; Burns, P.C. Crystal chemistry of lead oxide phosphates: Crystal structures of Pb4O(PO4)2, Pb8O5(PO4)2 and Pb10(PO4)6O. Z. Krist. Cryst. Mater. 2003, 218, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravi, C.; Panigrahi, B.K.; Valsakumar, M.C.; van de Walle, A. First-principles calculation of phase equilibrium of V-Nb, V-Ta, and Nb-Ta alloys. Phys. Rev. B 2012, 85, 054202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordell, J.J.; Pan, J.; Tamboli, A.C.; Tucker, G.J.; Lany, S. Probing configurational disorder in ZnGeN2 using cluster-based Monte Carlo. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2021, 5, 024604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavrentiev, M.Y.; Nguyen-Manh, D.; Dudarev, S.L. Magnetic cluster expansion model for bcc-fcc transitions in Fe and Fe-Cr alloys. Phys. Rev. B 2010, 81, 184202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decolvenaere, E.; Levin, E.; Seshadri, R.; Van der Ven, A. Modeling magnetic evolution and exchange hardening in disordered magnets: The example of Mn1−xFexRu2Sn Heusler alloys. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2019, 3, 104411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, M.B.; Majher, J.D.; Holzapfel, N.P.; Woodward, P.M. Exploring the Stability of Mixed-Halide Vacancy-Ordered Quadruple Perovskites. Chem. Mater. 2021, 33, 2165–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rom, C.L.; Smaha, R.W.; Melamed, C.L.; Schnepf, R.R..; Heinselman, K.N.; Mangum, J.S.; Lee, S.J.; Lany, S.; Schelhas, L.T.; Greenaway, A.L.; et al. Combinatorial Synthesis of Cation-Disordered Manganese Tin Nitride MnSnN2 Thin Films with Magnetic and Semiconducting Properties. Chem. Mater. 2023, 35, 2936–2946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehring, G.A.; Gehring, K.A. Co-operative Jahn-Teller effects. Rep. Prog. Phys. 1975, 38, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lany, S.; Zunger, A. Polaronic hole localization and multiple hole binding of acceptors in oxide wide-gap semiconductors. Phys. Rev. B 2009, 80, 085202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pashov, D.; Larsen, R.E.; Watson, M.D.; Acharya, S.; van Schilfgaarde, M. TiSe2 is a band insulator created by lattice fluctuations, not an excitonic insulator. npj Comput. Mater. 2025, 11, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabezas-Escares, J.; Barrera, N.F.; Lavroff, R.H.; Alexandrova, A.N.; Cardenas, C.; Munoz, F. Electronic structure and vibrational stability of copper-substituted lead apatite LK-99. Phys. Rev. B 2024, 109, 144515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, K.; Chen, R.; Yang, L.; Gao, J.; Xue, D.; Jia, C. The 1/4 occupied O atoms induced ultra-flatband and the one-dimensional channels in the Pb10−xCux(PO4)6O4 (x = 0, 0.5) crystal. APL Mater. 2024, 12, 021120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Lee, S.B.; Herzog-Arbeitman, J.; Yu, J.; Feng, X.; Hu, H.; Călugăru, D.; Brodale, P.S.; Gormley, E.L.; Vergniory, M.G.; et al. Pb9Cu(PO 4)6(OH)2: Phonon bands, localized flat-band magnetism, models, and chemical analysis. Phys. Rev. B 2023, 108, 235127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakol, O.; Scaffidi, T. Minimal model for the flat bands in copper-substituted lead phosphate apatite: Strong diamagnetism from multiorbital physics. Phys. Rev. B 2024, 109, L100504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.; Zhang, Y.H. S-wave pairing in a two-orbital t-J model on triangular lattice: Possible application to Pb10−xCux(PO4)6O. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.02469. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, D.; Zhang, Q.; Tao, M. LSDA+U study of cupric oxide: Electronic structure and native point defects. Phys. Rev. B 2006, 73, 235206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, B.; Grüning, M.; Pashov, D.; van Schilfgaarde, M. QSG: Quasiparticle Self Consistent GW with Ladder Diagrams in W. Phys. Rev. B 2023, 108, 165104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaanen, J.; Sawatzky, G.A.; Allen, J.W. Band gaps and electronic structure of transition-metal compounds. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1985, 55, 418–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, S.; Katsnelson, M.I.I.; van Schilfgaarde, M. Vertex dominated superconductivity in intercalated FeSe. npj Quantum Mater. 2023, 8, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, S.; Pashov, D.; Jamet, F.; van Schilfgaarde, M. Controlling Tc through Band Structure and Correlation Engineering in Collapsed and Uncollapsed Phases of Iron Arsenides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2020, 124, 237001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| GGA+U | GGA | SCAN | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu Site | sb | sc | sb | sc | sb | sc |

| 4f-1 | 0 | 0.83 | 0 | 0.41 | 0 | 0.46 |

| 4f-2 | 0.08 | 1.23 | 0.08 | 0.65 | 0.27 | 1.04 |

| 6h-1 | 0.13 | 0.04 | 0.24 | |||

| 6h-2 | 0.11 | 0.50 | ||||

| 6h-2’ | 0.04 | −0.03 | 0.44 |

| Cu Site | GGA+U | GGA | SCAN |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4f-1 | 1.22 | 0.56 | 1.31 |

| 4f-2 | 1.12 | 0.46 | 1.20 |

| 6h-1 | 1.42 | 0.75 | 1.46 |

| 6h-2 | 1.17 | 1.25 | |

| 6h-2’ | 1.19 | 0.64 | 1.29 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kurleto, R.; Lany, S.; Pashov, D.; Acharya, S.; van Schilfgaarde, M.; Dessau, D.S. Pb-Apatite Framework as a Generator of Novel Flat-Band CuO-Based Physics. Crystals 2026, 16, 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16010074

Kurleto R, Lany S, Pashov D, Acharya S, van Schilfgaarde M, Dessau DS. Pb-Apatite Framework as a Generator of Novel Flat-Band CuO-Based Physics. Crystals. 2026; 16(1):74. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16010074

Chicago/Turabian StyleKurleto, Rafał, Stephan Lany, Dimitar Pashov, Swagata Acharya, Mark van Schilfgaarde, and Daniel S. Dessau. 2026. "Pb-Apatite Framework as a Generator of Novel Flat-Band CuO-Based Physics" Crystals 16, no. 1: 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16010074

APA StyleKurleto, R., Lany, S., Pashov, D., Acharya, S., van Schilfgaarde, M., & Dessau, D. S. (2026). Pb-Apatite Framework as a Generator of Novel Flat-Band CuO-Based Physics. Crystals, 16(1), 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16010074