Wide-Temperature-Range Optical Thermometry Based on Yb3+,Er3+:CaYAlO4 Phosphor

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

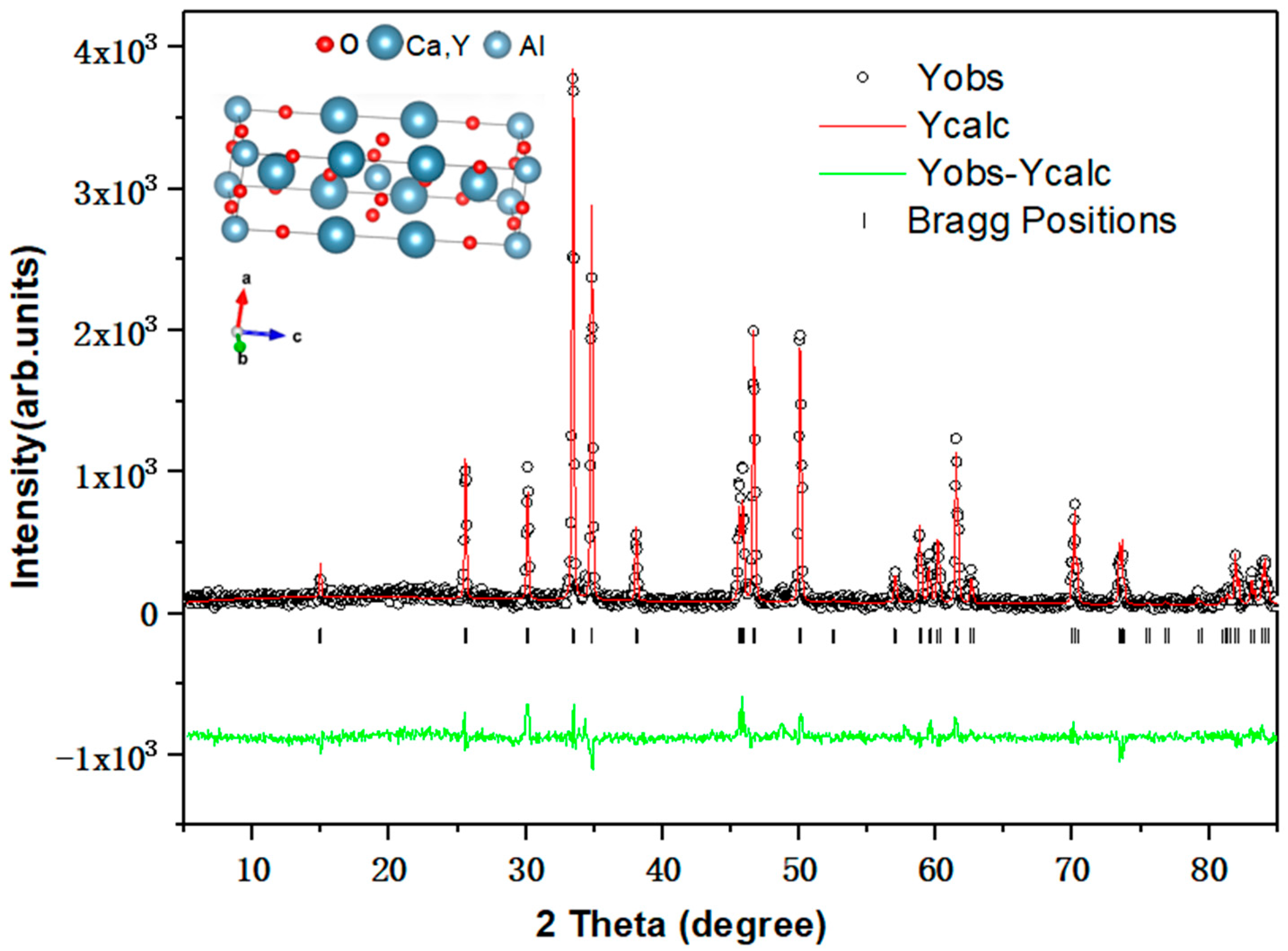

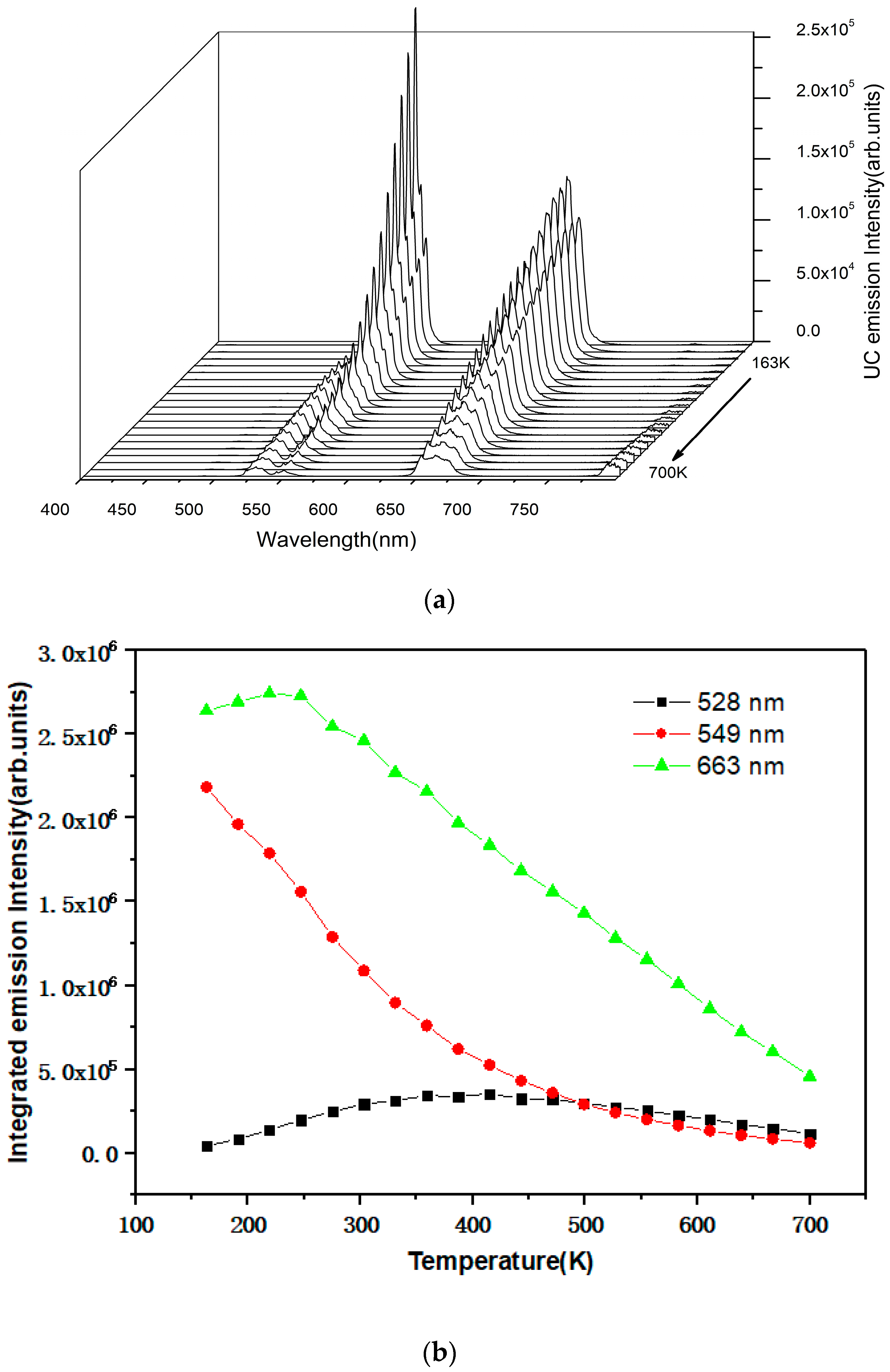

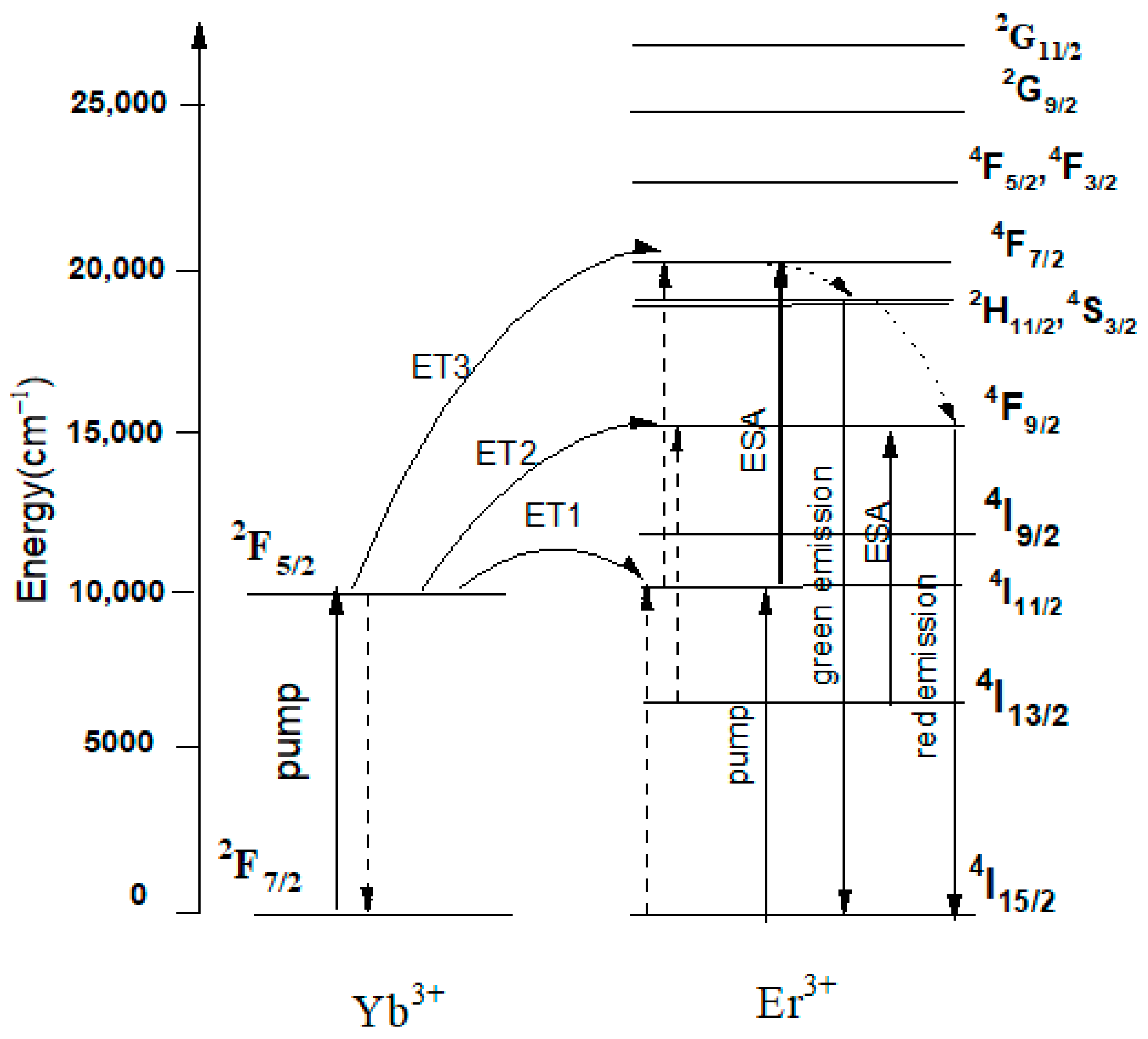

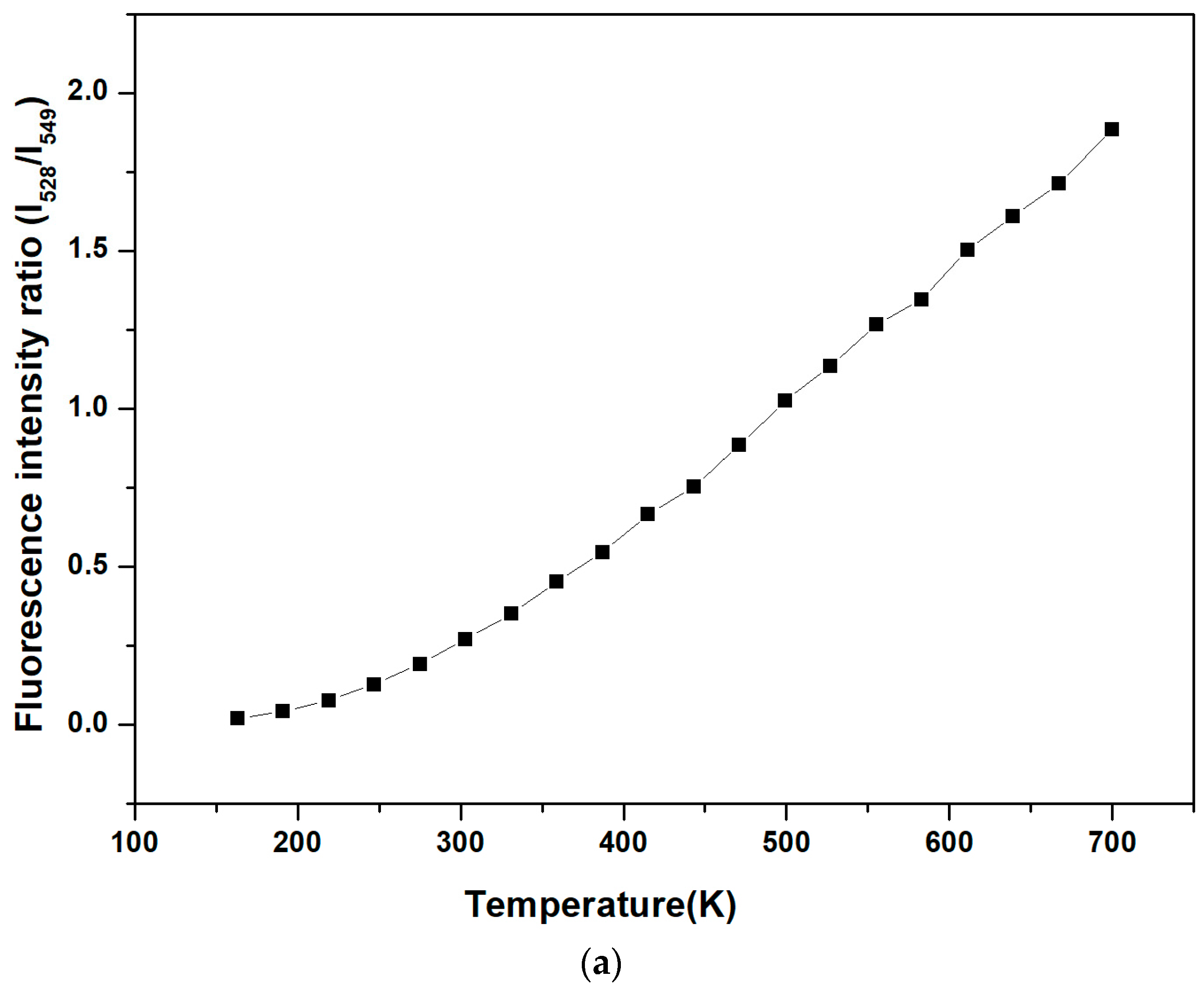

3. Results and Discussions

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Z.; Zhou, D.; Jensen, L.R.; Qiu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yue, Y. Er3+-Yb3+ions doped fluoroaluminosilicate glass-ceramics as a temperature-sensing material. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2021, 104, 4471–4478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.; Cao, B.; He, Y.; Liu, Z.; Feng, Z. Temperature sensing and in vivo imaging by molybdenum sensitized visible upconversion luminescence of rare earth oxides. Adv. Mater. 2012, 24, 1987–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Chen, D.; Peng, Y.; Lu, Y.; Chen, X.; Li, X.; Ji, Z. A review on nanostructured glass ceramics for promising application in optical thermometry. J. Alloys Compd. 2018, 763, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Shen, Y.; Zhou, H.; Wang, J.; Zhu, K.; Ye, L.; Yu, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, L.-G. Upconversion luminescence and thermal sensing properties of LuYO3: Er3+/Yb3+ phosphor. J. Lumin. 2024, 275, 120799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.J.; Chen, J.; Peng, X.; Xu, S.; Wei, R.; Guo, H. Energy transfer and luminescent properties of Lu2WO6:Bi3+,Eu3+ red emission phorphor. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 25806–25814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, J.; Wang, M.; Zhu, Y.; Zhu, H.; Yan, D.; Liu, C.; Xu, C.; Liu, Y. Tm3+/Yb3+ codoped CaGdAlO4 phosphors for wide-range optical temperature sensing. J. Lumin. 2022, 248, 118935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kshetri, Y.K.; Chaudhary, B.; Kim, T.-H.; Kim, H.S.; Lee, S.W. Yb/Er/Ho-α--SiAlON ceramics for high-temperature optical thermometry. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2021, 41, 2400–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedamati, S.; Behera, M.; Kumar, R.A.; Shwetabh, K.; Kumar, K. Sodium yttrium fluoride doped with Er3+ ions for thermally and non-thermally coupled nano-thermometry and IR detection application. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 411, 125685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Ji, B.; Chen, G.; Hua, Z. Upconversion luminescence and discussion of sensitivity improvement for optical temperature sensing application. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 5038–5047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, Y.; Yang, X.; Wang, F.; Li, Z.; Ding, G.; Qiu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Han, S.T. Infrared-sensitive memory based on direct-grown MoS2-Upconversion-Nanoparticle heterostructure. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1803563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, P.; Guo, Q.; Liao, L.; Su, K.; Ding, J.; An, N.; Mei, L.; Woźny, P.; Runowski, M. Preparation and sensing performance study in ultra-wide temperature range of K3LuF6:Er3+,Yb3+ up-converting luminescent materials with cryolite structure. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 30879–30886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabakaran, E.; Pillay, K. Nanomaterials for latent fingerprint detection: A review. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 12, 1856–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Feng, L.; Yu, Y.; Li, R.; Ao, Z. Temperature-dependent upconversion luminescence of YVO4:Yb3+/Er3+/Ho3+phosphors for multimodal optical anti-counterfeiting and temperature sensing applications. Ceram. Int. 2024, 51, 10618–10627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.Z.; Xu, X.D.; Cheng, S.S.; Zhou, D.H.; Wu, F.; Zhao, Z.W.; Xia, C.T.; Xu, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, H.M.; et al. Erratum to: Polarized spectral prperties of Nd3+ ions in CaYAlO4 crystal. Apply Phys. B 2010, 101, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hutchinson, J.A.; Verdun, H.R.; Chai, B.H.T.; Zandi, B.; Merkle, L.D. Spectroscopic evaluation of CaYAlO4 doped with trivalent Er3+,Tm3+,Yb3+ and Ho3+ for eyesafe laser application. Opt. Mater. 1994, 3, 287–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souriau, J.C.; Borel, C.; Wyon, C.; Li, C.; Moncorgé, R. Spectroscopic properties and fluorescence dynamics of Er3+ and Yb3+ in CaYAlO4. J. Lumin. 1994, 59, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Yao, S.; Chen, Q.; Bai, Y. Intense red upconversion emission and energy transfer in Yb3+/Ho3+/Er3+:CaYAlO4. J. Lumin. 2018, 166, 36–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrella, R.V.; Schiavon, M.A.; Pecoraro, E.; Ribeiro, S.; Ferrari, J. Broadened band C-telecom and intense upconversion emission of Er3+/Yb3+ co-doped CaYAlO4 luminecent material obtained by an easy route. J. Lumin. 2016, 178, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Yao, X. Optical temperature sensing of up-conversion luminescent materials: Fundamentals and process. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 817, 152691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinovic, A.; Milicevic, B.; Perisa, J.; Ristić, Z.; Stojadinović, S.; Dramićanin, M.D.; Ćirić, A. Thermometric Judd-Ofelt model for Dy3+ ion tested in CaYAlO4 host and evaluation of its sensing performances for luminescence thermometry. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2024, 666, 415096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, X.; Zhong, H.; Cheng, L.; Xu, S.; Sun, J.; Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Tong, L.; Chen, B. Effects of Er3+concentration on down-/up-conversion luminescence and temperature sensing properties in NaGdTiO4:Er3+/Yb3+phosphors. Ceram. Int. 2016, 42, 14710–14715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisarski, W.A.; Janek, J.; Pisarska, J.; Lisiecki, R.; Ryba-Romanowski, W. Influence of temperature on up-conversion luminescene in Er3+/Yb3+ doubly doped lead-free fluorogermanate glasses for optical sensing. Sens. Actuators B 2017, 253, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Gao, D.; Wang, L.; Song, W.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, S.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Q. Experimental optimization design synthesis for up-conversion luminescence performance in SrBi4Ti4O15:Er3+/Yb3+ red-green phosphors. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 2024, 41, 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, G.B.; Tamboli, S.; Dhoble, S.J.; Swart, H.C. LaOF:Yb3+,Er3+upconversionnanophosphors operating at low laser powers for nanothermometry applications. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2023, 6, 15255–15265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, X.; Hu, R.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Yao, X. Improved temperature sensing performance based on stark sublevels of Er3+/Yb3+ co-doped tungstate-molybdate up-conversion phosphors. Mater. Res. Bull. 2020, 131, 110959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; Lv, S.; Feng, Z. Synthesis and photoluminescent properties of Dy3+: CaYAlO4 phosphors. Appl. Phys. A 2021, 127, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Meng, R.; Hao, H.; Bai, Y.; Gao, Y.; Song, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X. Stark sublevels of Er3+_Yb3+ codoped Gd2(WO4)3 phosphor for enhancing the sensitivity of a luminescent thermometer. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 57667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Fu, L.; Gao, Z.; Yang, X.; Fu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Yang, Y. Investigation into the temperature sensing behavior of Yb3+ sensitized Er3+ doped Y2O3, YAG and LaAlO3 phosphors. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 51820–51827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.; Peng, X.; Ashraf, G.A.; Hu, F.; Wei, R.; Guo, H. Dual-mode optical thermometry based on transparent NaY2F7:Er3+,Yb3+ glass-ceramics. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 4023–4030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.; Liu, D.P.; Wang, X.J.; Yang, T.; Miao, S.M.; Li, C.R. Optical thermometry through infrared excited green upconversion emissions in Er3+-Yb3+ codoped Al2O3. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2007, 90, 181117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Lin, L.; Wang, Z.; Zheng, Z. Low temperature sensing behavior of upconversion luminescence in Er3+/Yb3+ codoped PLZT transparent ceramic. Opt. Commun. 2017, 399, 40–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shwetabh, K.; Mishra, N.K.; Kumar, K. NIR activated Er3+/Yb3+ doped LiYF4 upconverting nanocrystals for photothermal treatment, optical thermometry, latent fingerprint detection and security ink applications. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2023, 167, 107806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Compounds | Transitions Studied for Temperature Sensing | Temperature Range (K) | Sr-Max (% per K) | Sa-Max (% per K) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NaY2F7:Yb3+,Er3+ | Er3+:2H11/2 → 4I15/2, 4S3/2 → 4I15/2 | 323–563 | 1.00 (323 K) | 0.36 (563 K) | [29] |

| Al2O3:Yb3+,Er3+ | Er3+:2H11/2 → 4I15/2, 4S3/2 → 4I15/2 | 295–973 | — | 0.51 (770 K) | [30] |

| PLZT:Yb3+,Er3+ | Er3+:2H11/2 → 4I15/2, 4S3/2 → 4I15/2 | 140–320 | — | 0.059 (320 K) | [31] |

| YAG:Yb3+,Er3+ | Er3+:2H11/2 → 4I15/2, 4S3/2 →4I15/2 | 298–573 | — | 0.17 (404 K) | [32] |

| NaYF4:Er3+ | Er3+:2H11/2 → 4I15/2, 4S3/2 → 4I15/2 | 300–540 | 0.92 (300 K) | 0.348 (420 K) | [8] |

| α-SiAlON ceramic:Yb3+,Er3+,Ho3+ | Er3+:2H11/2 → 4I15/2, 4S3/2 → 4I15/2 | 298–1023 | 1.1 (298 K) | 0.592 (298 K) | [7] |

| CYA:Yb3+,Er3+,Ho3+ | Er3+:2H11/2 → 4I15/2, 4S3/2 → 4I15/2,Ho3+:5S2,5F4 → 5I8 | 163–700 | 4.49 (163 K) | 0.24 (611 K) | [17] |

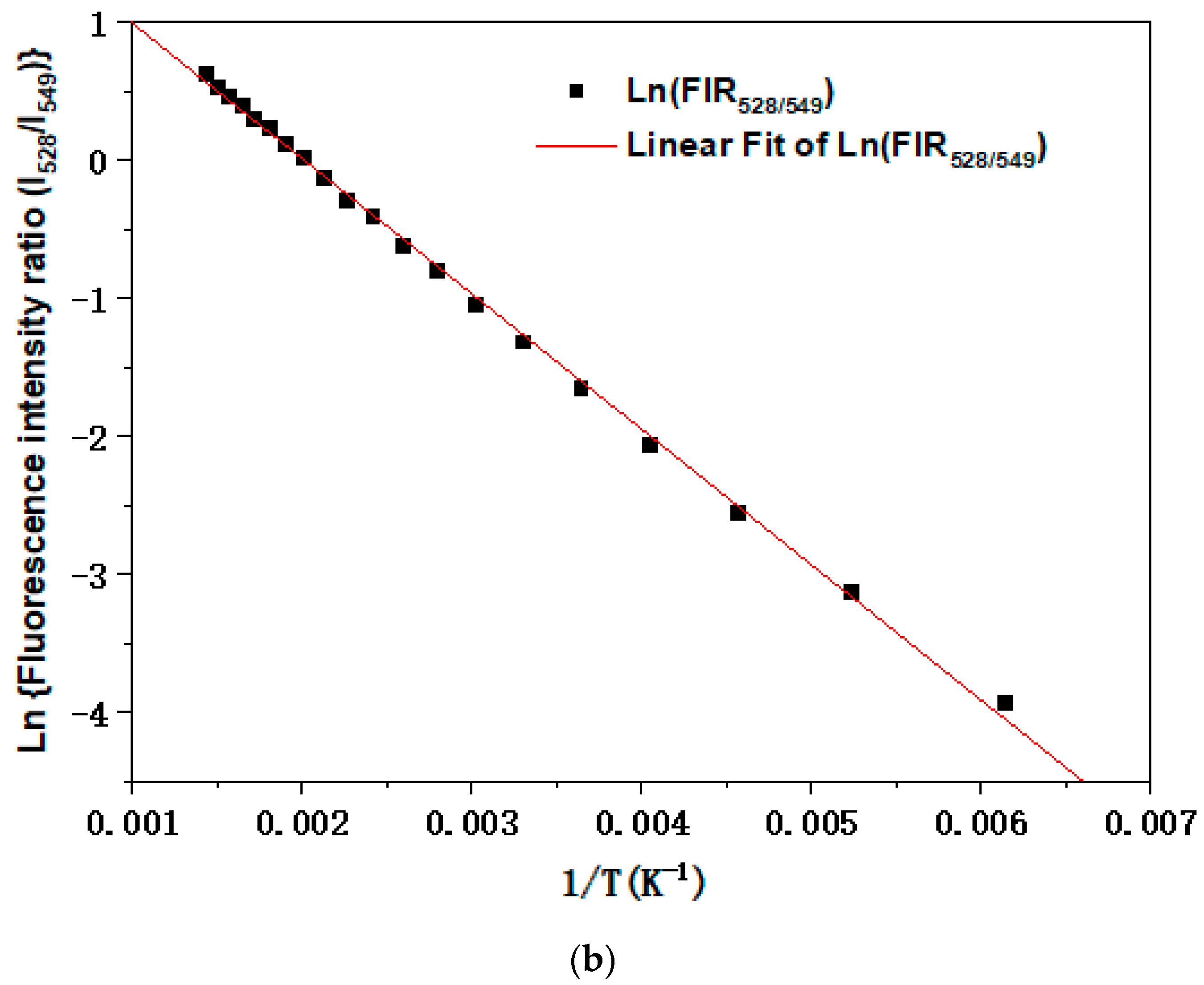

| CYA:Yb3+,Er3+ | Er3+:2H11/2 → 4I15/2, 4S3/2 → 4I15/2 | 163–700 | 3.69 (163 K) | 0.404 (415 K) | this work |

| Compounds | Transitions Studied for Temperature Sensing | Temperature Range (K) | Sr-Max (% per K) | Sa-Max (% per K) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NaYF4:Er3+ | Er3+:2H11/2 → 4I15/2, 4F9/2 → 4I15/2 | 300–540 | 0.584 (440 K) | 0.262 (540 K) | [8] |

| YVO4:Yb3+,Er3+,Ho3+ | Ho3+:5F5 → 5I8, Er3+: 2H11/2 → 4I15/2, 4S3/2 → 4I15/2 | 373–573 | 1.47 (373 K) | 0.50 (373 K) | [13] |

| PLZT:Yb3+,Er3+ | Er3+:2H11/2 → 4I15/2, 4F9/2 → 4I15/2 | 140–320 | — | 0.2184 (320 K) | [31] |

| LiYF4:Yb3+,Er3+ | Er3+:2H11/2 → 4I15/2, 4F9/2 → 4I15/2 | 300–500 | 0.90 | — | [32] |

| α-SiAlON ceramic:Yb3+,Er3+,Ho3+ | Er3+:4F9/2 → 4I15/2, 4S3/2 → 4I15/2 | 298–873 | 0.345 (329 K) | 1.08 (385 K) | [7] |

| CYA:Yb3+,Er3+,Ho3+ | Er3+:4F9/2 → 4I15/2, Ho3+:5F5 → 5I8 Er3+:4S3/2 → 4I15/2 | 163–700 | 2.72 (191 K) | 2.34 (583 K) | [17] |

| CYA:Yb3+,Er3+,Ho3+ | Er3+:2H11/2 → 4I15/2, 4F9/2 → 4I15/2, Ho3+:5F5 → 5I8 | 163–700 | 1.77 (191 K) | 0.031 (331 K) | [17] |

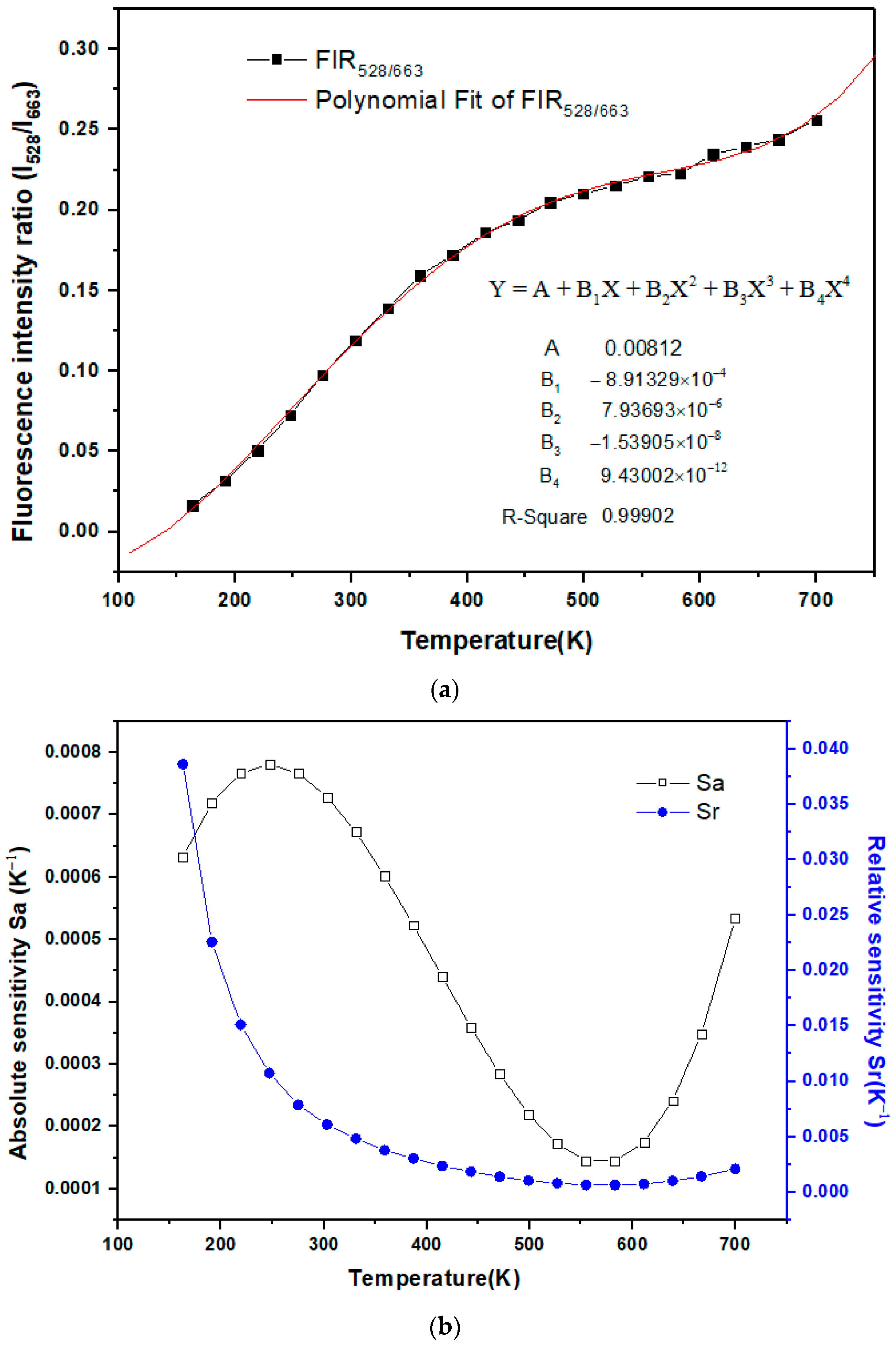

| CYA:Yb3+,Er3+ | Er3+:4F9/2 → 4I15/2, 4S3/2 → 4I15/2 | 163–700 | 0.443 (275 K) | 1.52 (499 K) | this work |

| CYA:Yb3+,Er3+ | Er3+:2H11/2 → 4I15/2, 4F9/2 → 4I15/2 | 163–700 | 3.86 (163 K) | 0.08 (247 K) | this work |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lv, S.; Yao, S.; Feng, Z. Wide-Temperature-Range Optical Thermometry Based on Yb3+,Er3+:CaYAlO4 Phosphor. Crystals 2025, 15, 1055. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121055

Lv S, Yao S, Feng Z. Wide-Temperature-Range Optical Thermometry Based on Yb3+,Er3+:CaYAlO4 Phosphor. Crystals. 2025; 15(12):1055. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121055

Chicago/Turabian StyleLv, Shaozhen, Shaobo Yao, and Zhuohong Feng. 2025. "Wide-Temperature-Range Optical Thermometry Based on Yb3+,Er3+:CaYAlO4 Phosphor" Crystals 15, no. 12: 1055. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121055

APA StyleLv, S., Yao, S., & Feng, Z. (2025). Wide-Temperature-Range Optical Thermometry Based on Yb3+,Er3+:CaYAlO4 Phosphor. Crystals, 15(12), 1055. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121055