The Role of Rotational Tool Speed in the Joint Performance of AA2024-T4 Friction Stir Spot Welds at a Short 3-Second Dwell Time

Abstract

1. Introduction

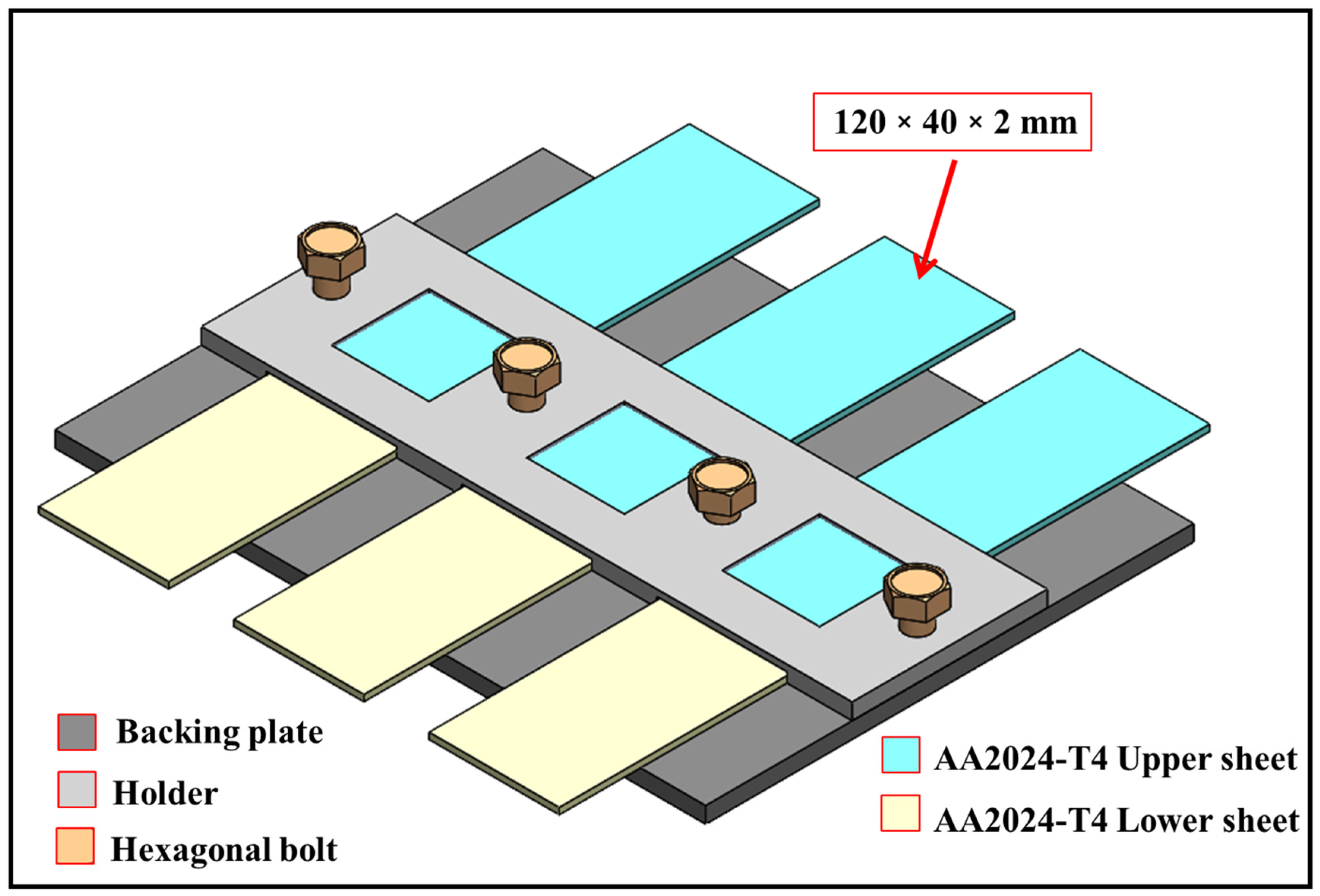

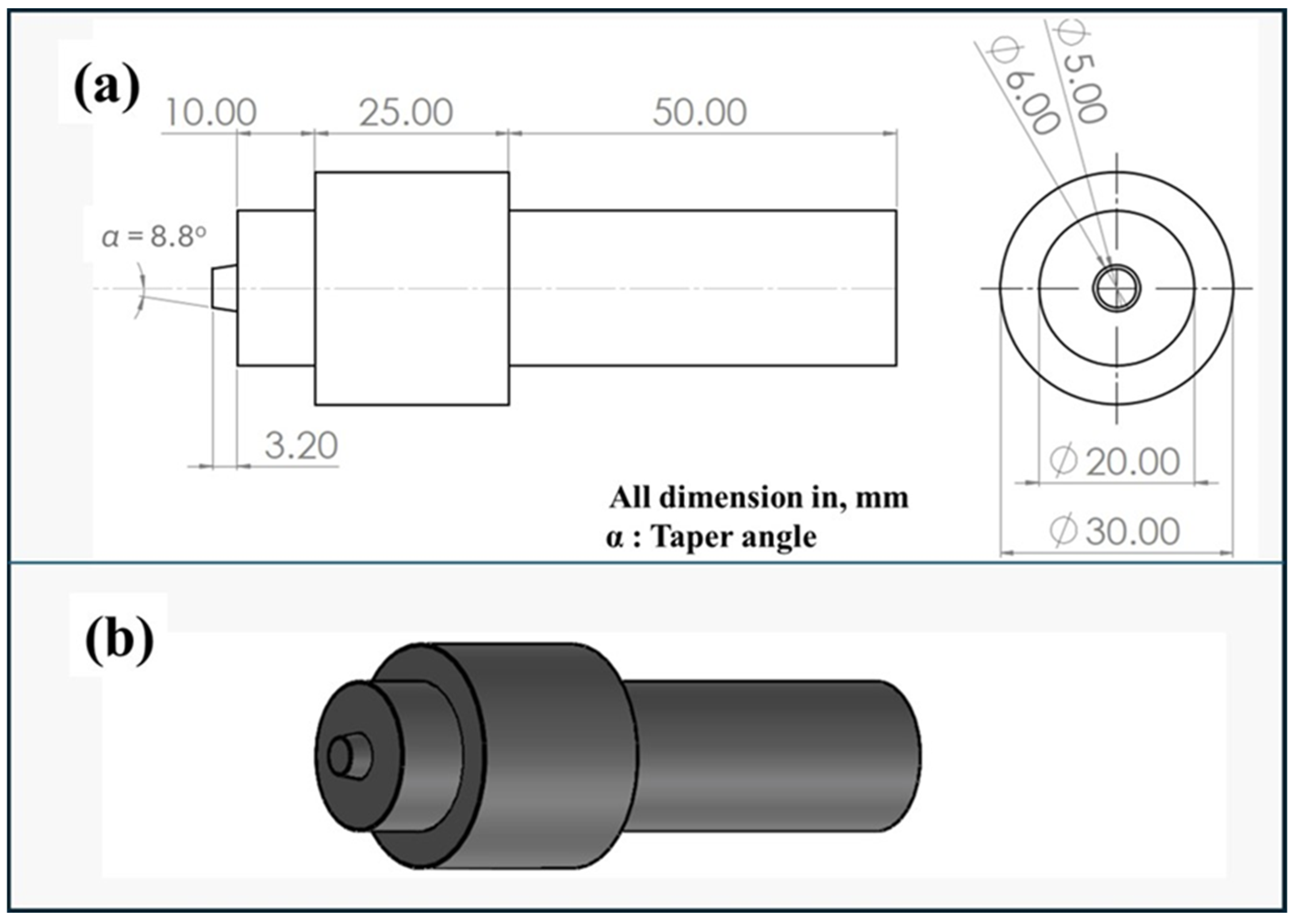

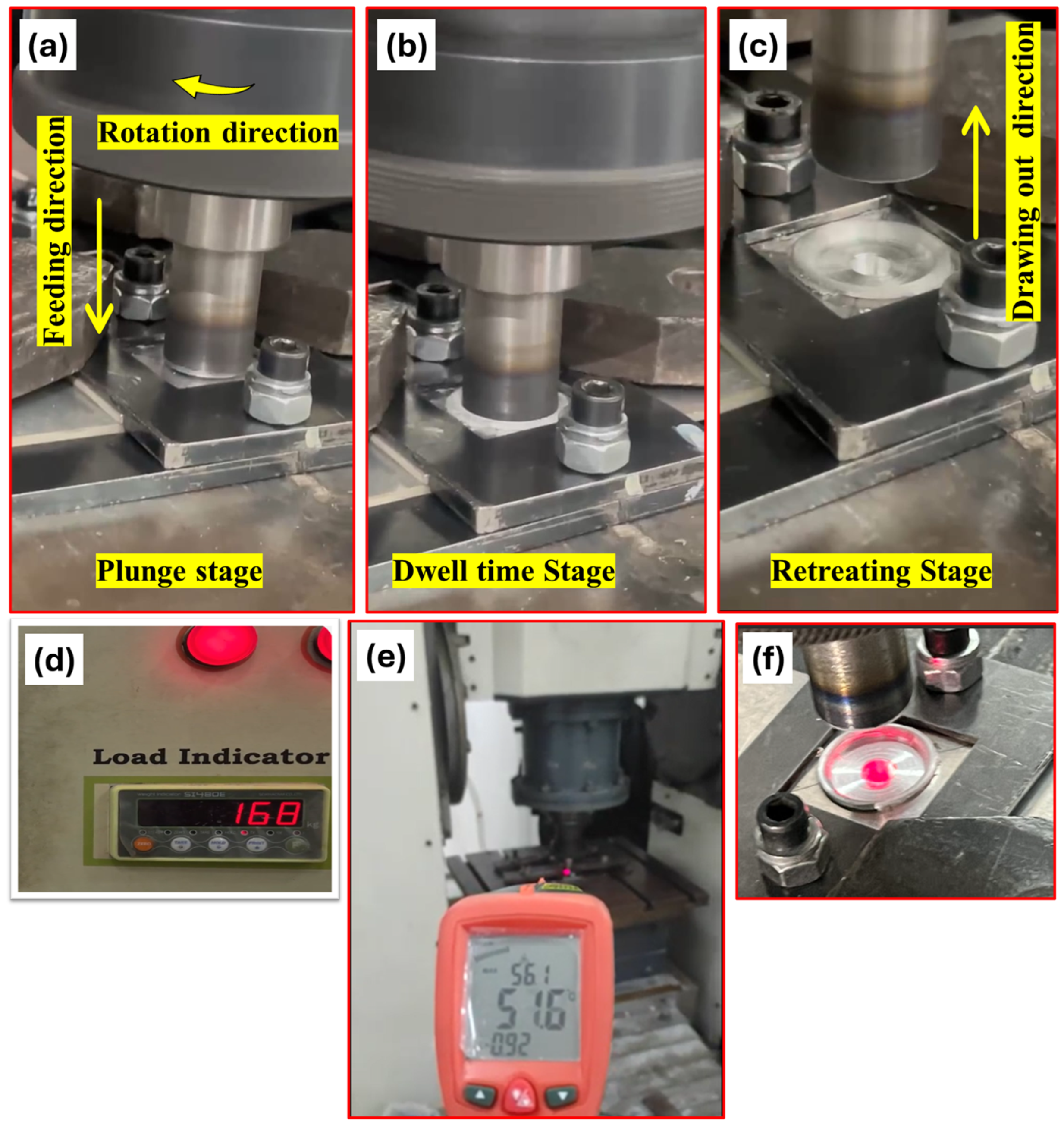

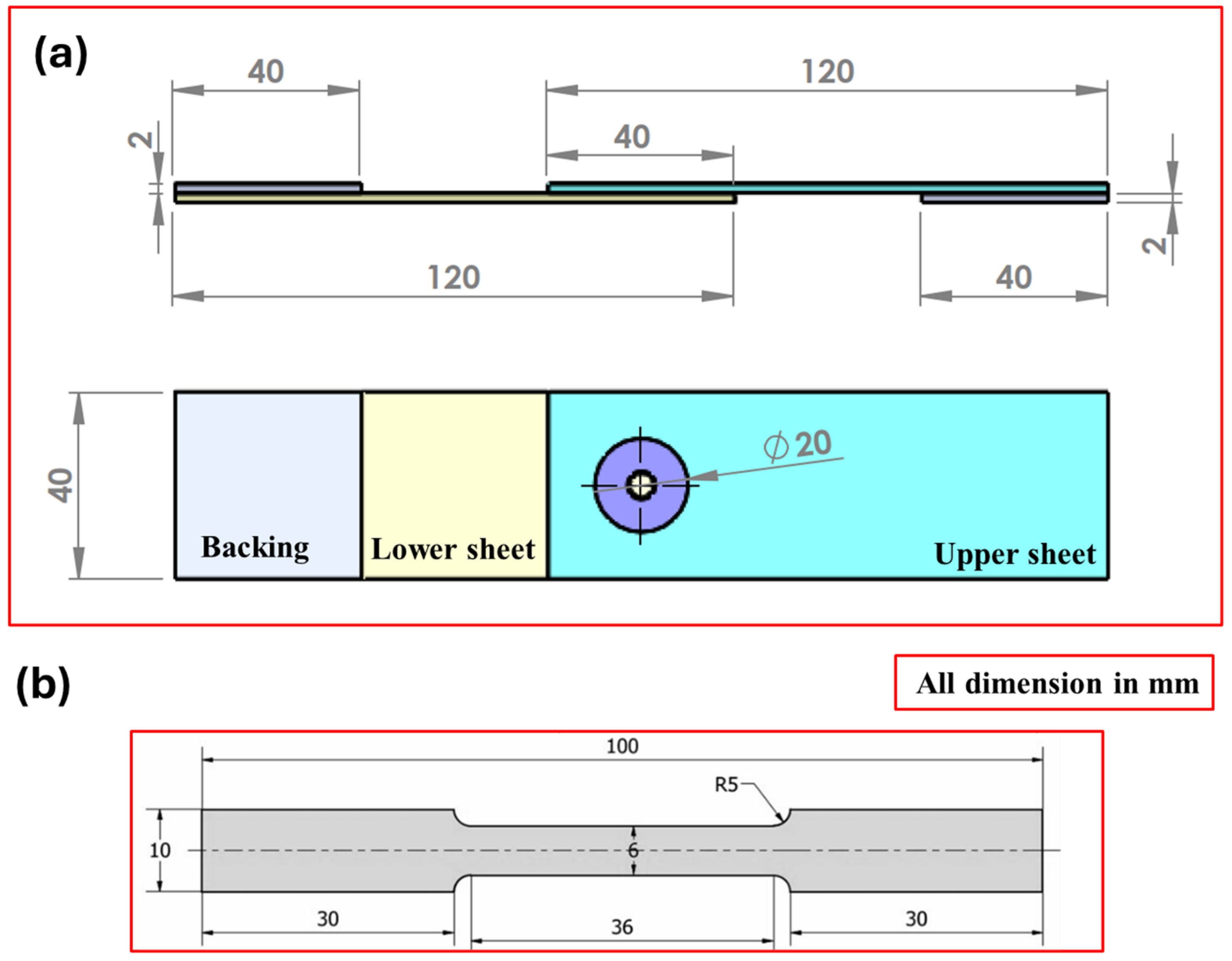

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

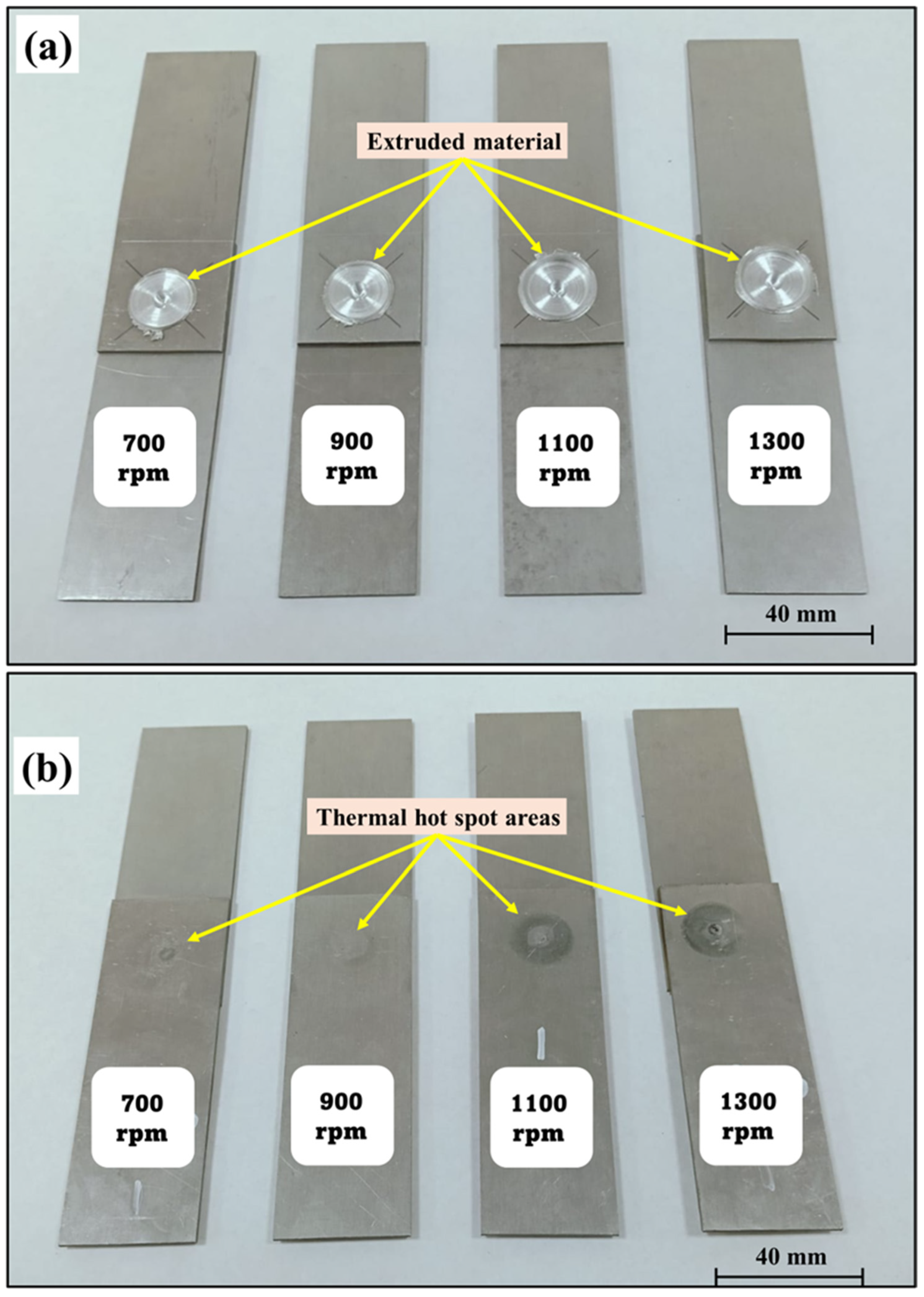

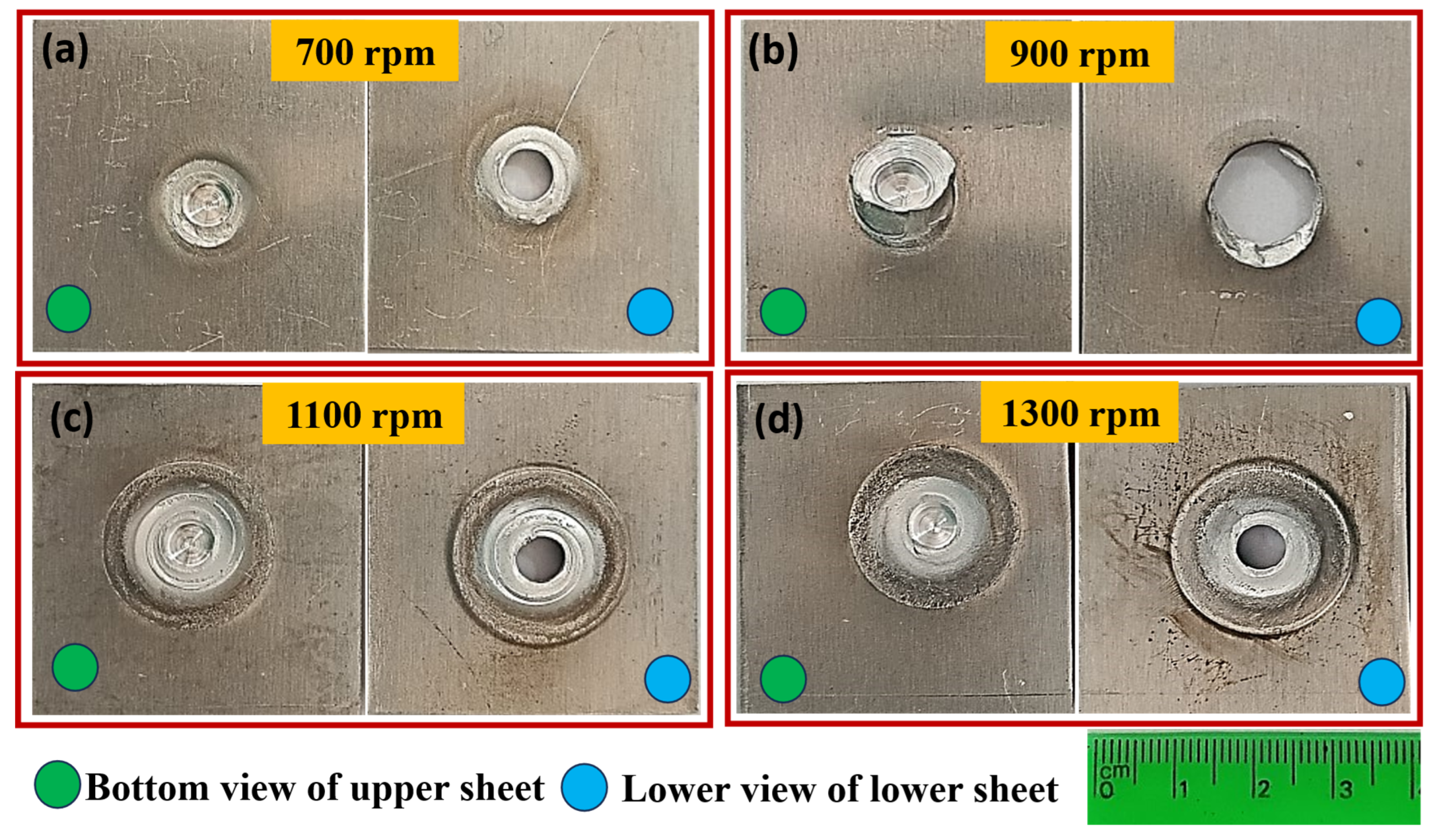

3.1. Macrostructural Appearance of FSSW Joints

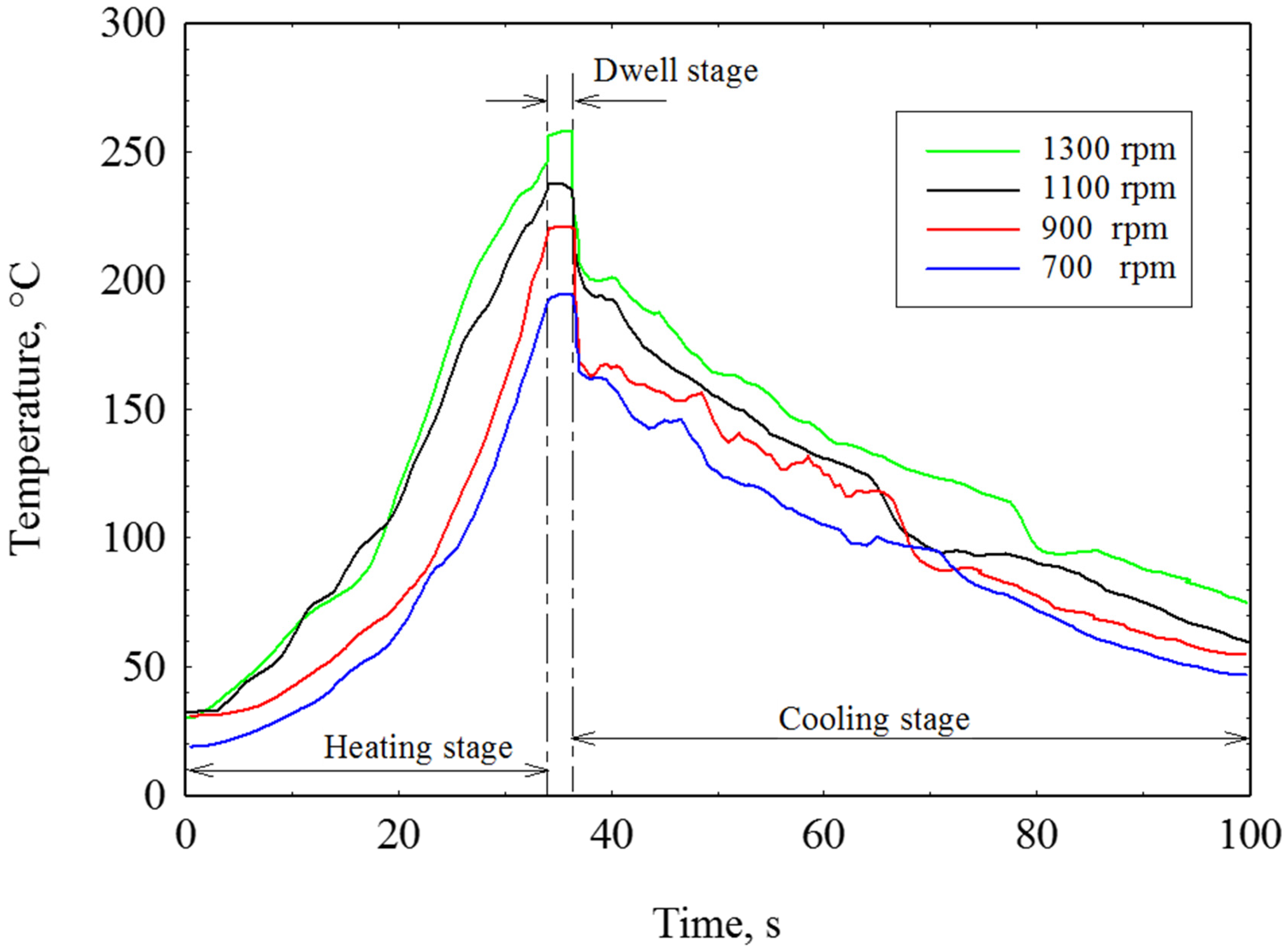

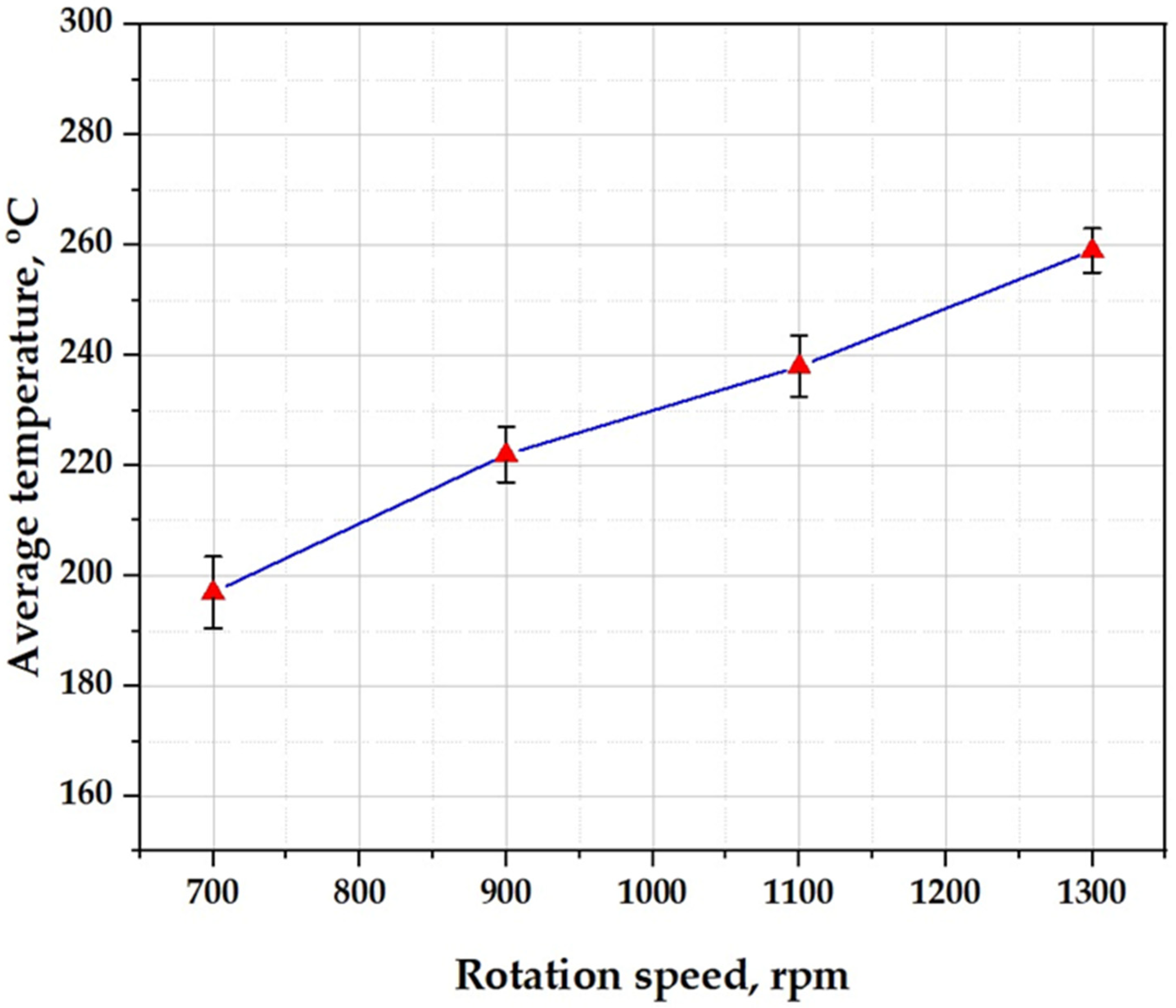

3.2. Temperature Variation with Rotational Speed in FSSW

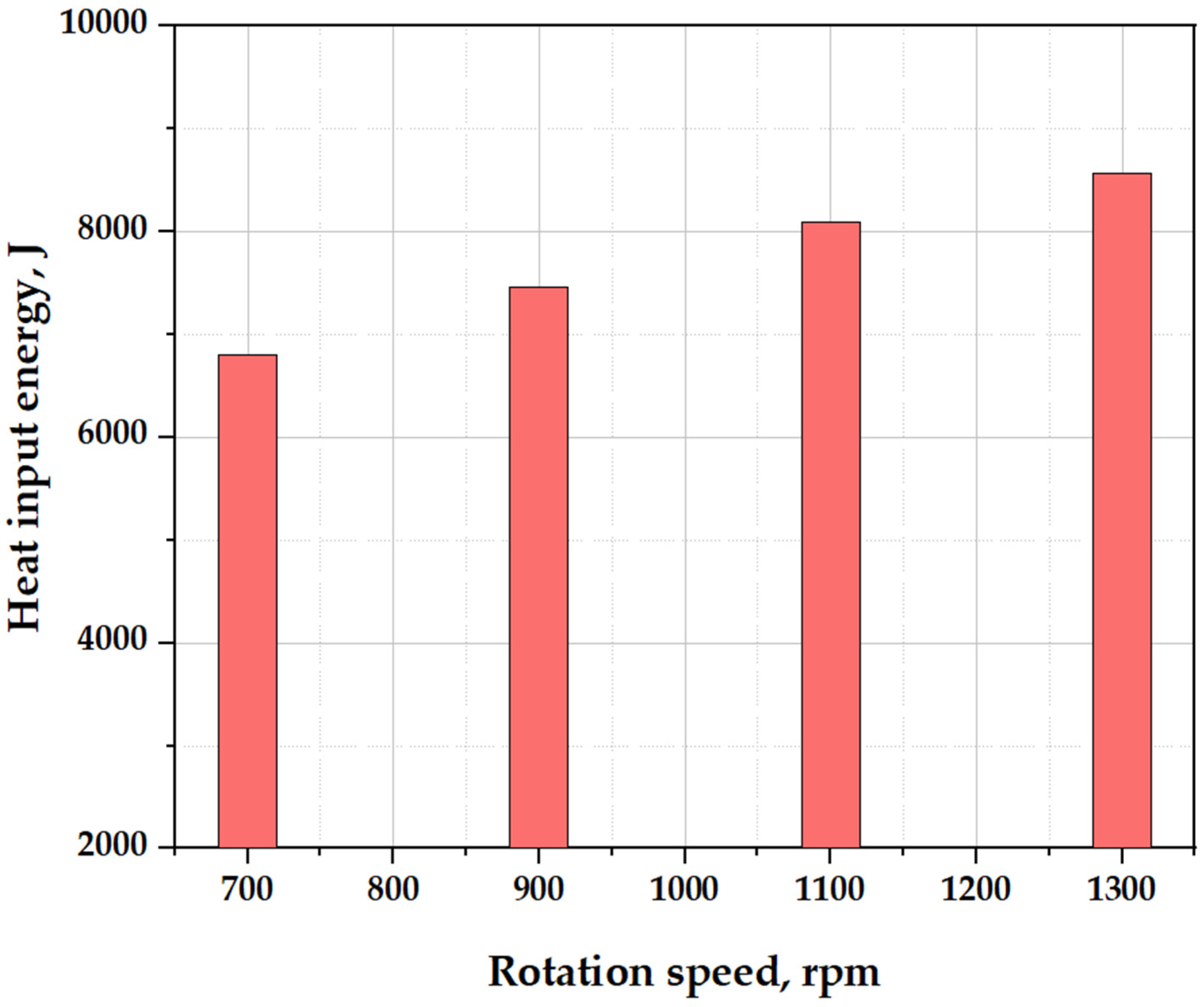

3.3. Thermal Energy Generation in FSSW

3.4. Features and Properties of the Produced Spot Joints

3.4.1. Macrographs of the FSSWed Joints

3.4.2. Microstructures of the FSSWed Joints

3.5. Mechanical Properties

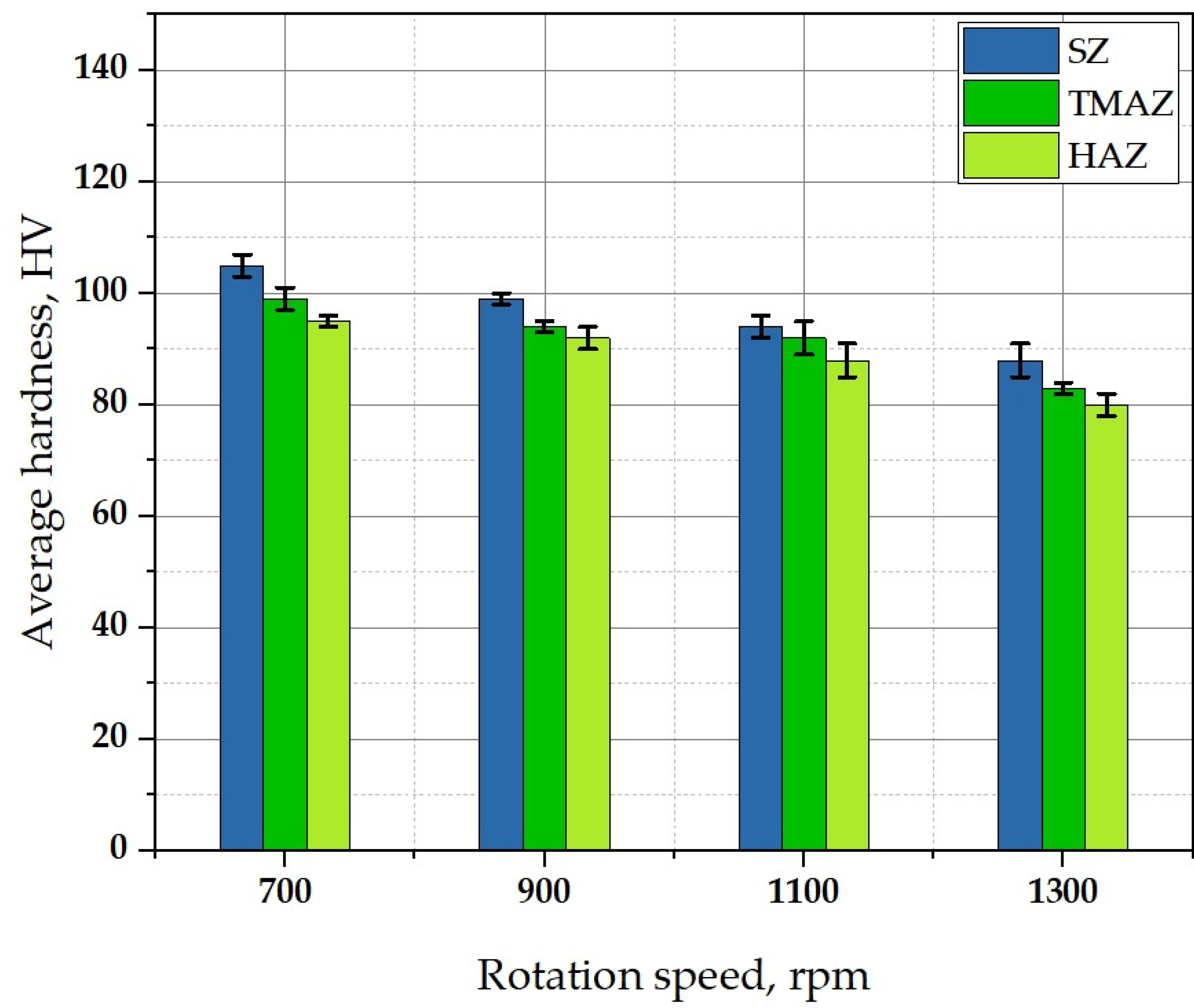

3.5.1. Hardness Test Results

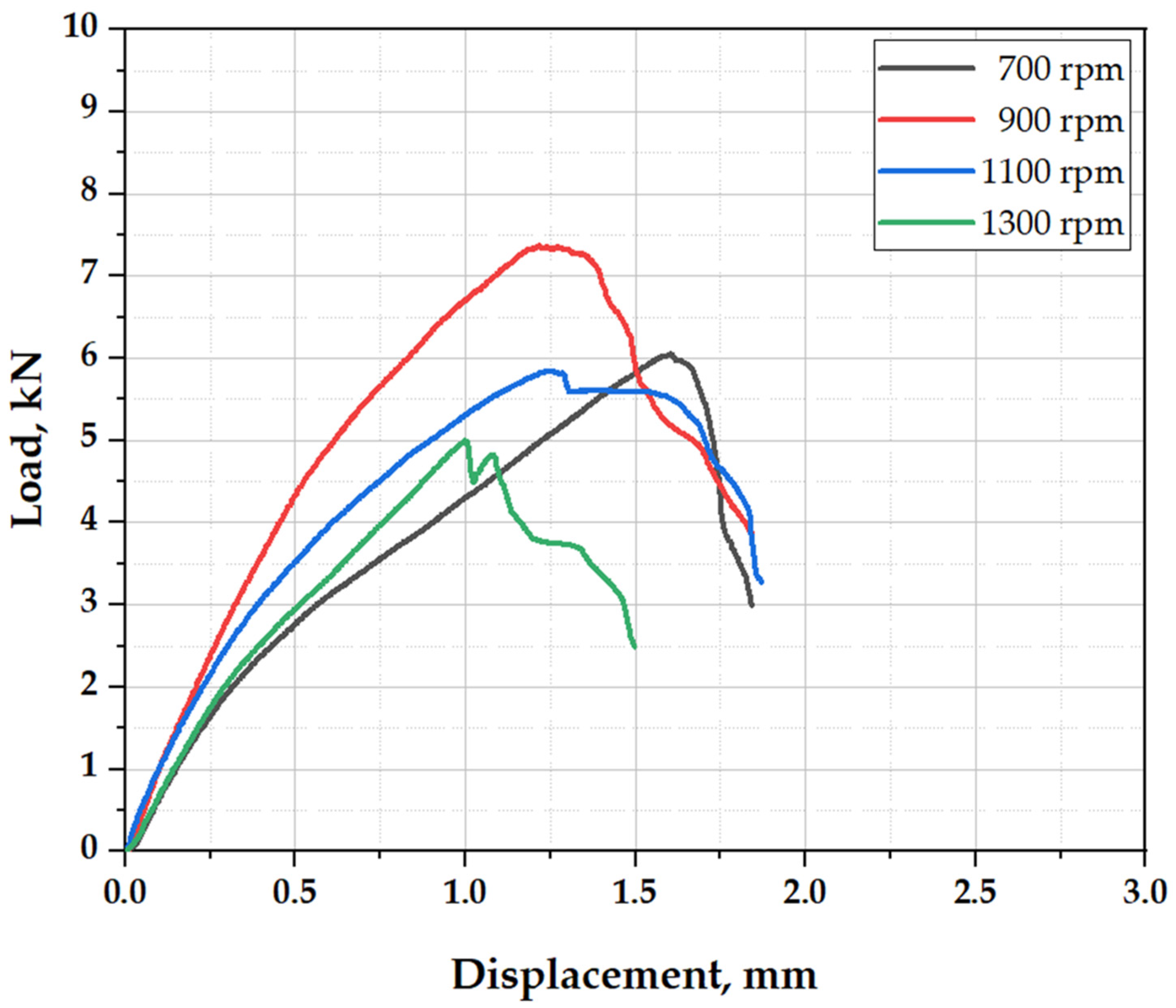

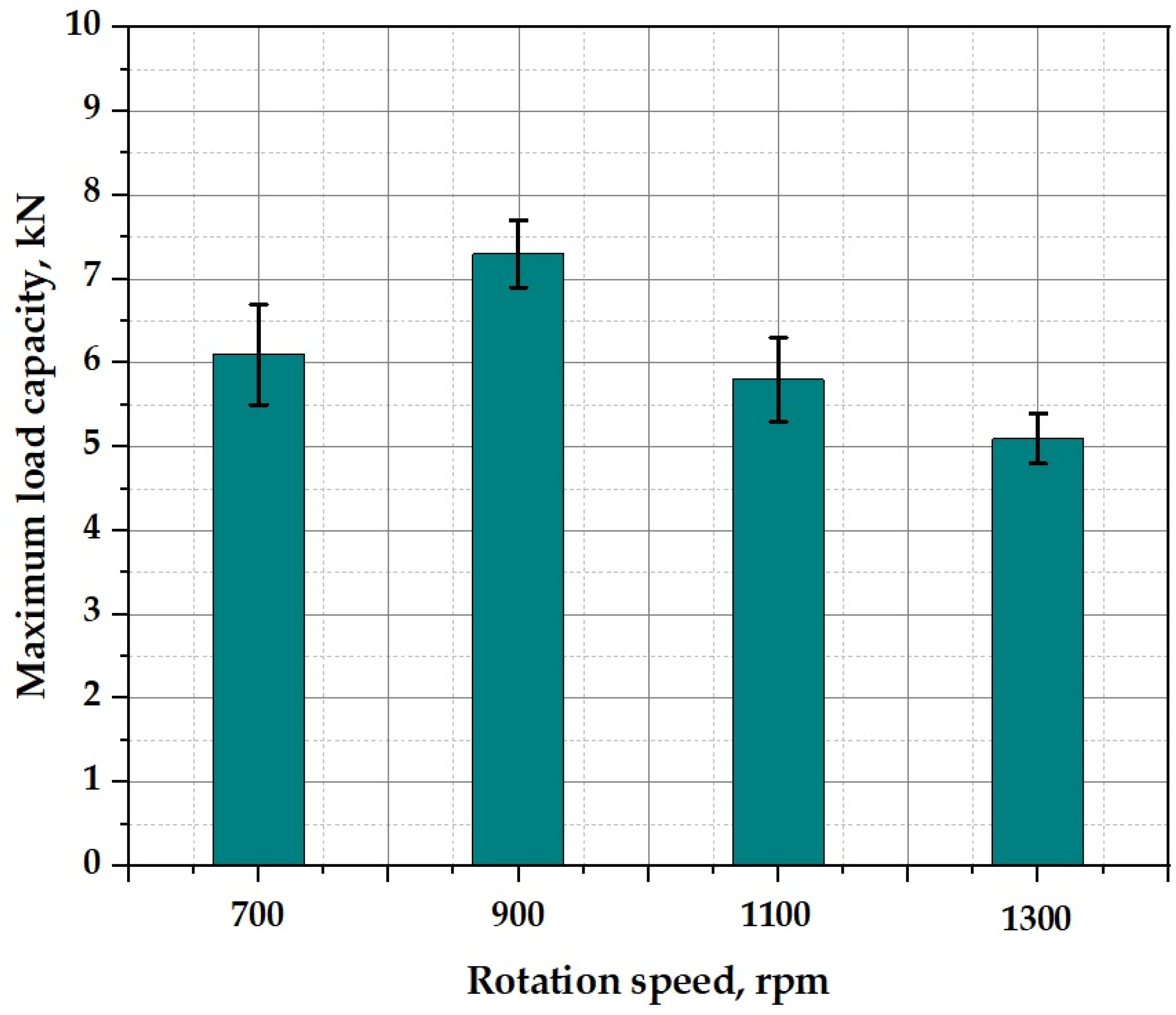

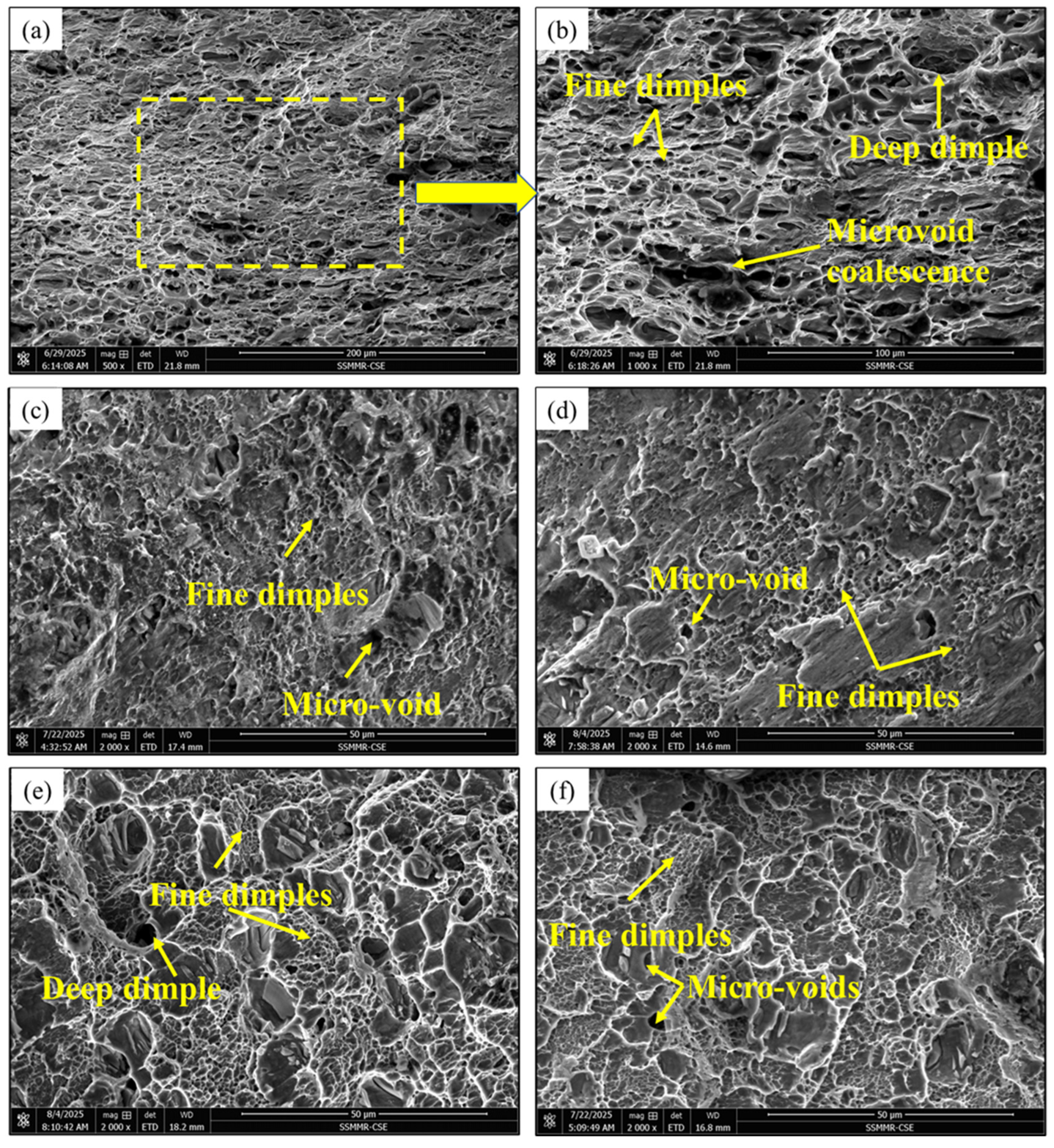

3.5.2. Load-Carrying Capacity and Fracture Behavior

4. Conclusions

- By using a short, fixed dwell time of 3 s and a range of tool rotational speeds (700–1300 rpm), this study shows that FSSW is an effective method for joining 2 mm thick AA2024 sheets in similar lap spot welds. The rapid cycle time achieved with these parameters is a key finding, as it indicates a significant advantage for productivity in industrial settings.

- An optimal tool rotational speed of 900 rpm was identified, producing joints with the highest tensile–shear strength of 7.3 ± 0.4 kN, as it achieved an ideal balance between sufficient material flow and controlled heat input.

- This study concluded that increasing the rotational speed from 700 to 1300 rpm resulted in a corresponding increase in the SZ grain size. The base material’s (BM) mean grain size of 29.7 ± 6.1 μm was significantly refined in all joints, but the refinement was most pronounced at 700 rpm, yielding the smallest grain size of 4.7 ± 1.4 μm. Conversely, the largest SZ grain size of 8.3 ± 1.3 μm was observed at 1300 rpm, directly correlating with the higher heat input at this speed.

- The fracture location and mode are directly governed by the rotational speed: joints at 700 rpm failed via interfacial fracture due to insufficient bonding, while joints at the optimal 900 rpm failed by a plug-type fracture through the nugget, indicating superior bond strength.

- Microstructural analysis confirms that failure in all cases remained ductile, characterized by dimpled fracture surfaces; however, the significantly finer and deeper dimples in the stir zone fracture surfaces are a direct consequence of grain refinement during the FSSW process.

- The findings of this research offer valuable insights for the practical implementation of FSSW, particularly for manufacturing applications in the aerospace and automotive industries where high-strength, lightweight structures are essential.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tiwan; Ilman, M.N.; Kusmono; Sehono. Microstructure and Mechanical Performance of Dissimilar Friction Stir Spot Welded AA2024-O/AA6061-T6 Sheets: Effects of Tool Rotation Speed and Pin Geometry. Int. J. Lightweight Mater. Manuf. 2023, 6, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dourandish, S.; Mousavizade, S.M.; Ezatpour, H.R.; Ebrahimi, G.R. Microstructure, Mechanical Properties and Failure Behaviour of Protrusion Friction Stir Spot Welded 2024 Aluminium Alloy Sheets. Sci. Technol. Weld. Join. 2018, 23, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton Savio Lewise, K.; Edwin Raja Dhas, J. FSSW Process Parameter Optimization for AA2024 and AA7075 Alloy. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2022, 37, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiquee, A.N.; Pandey, S.P.; Khan, N.Z. Friction Stir Welding of Austenitic Stainless Steel: A Study on Microstructure and Effect of Parameters on Tensile Strength. Mater. Today Proc. 2015, 2, 1388–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabry, I. Exploring the Effect of Friction Stir Welding Parameters on the Strength of AA2024 and A356-T6 Aluminum Alloys. J. Alloys Metall. Syst. 2024, 8, 100124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Huang, G.; Zhang, D.; Sun, Z.; Liu, Q. Microstructure and Mechanical Properties in Dissimilar Friction Stir Welded AA2024/7075 Joints at High Heat Input: Effect of Post-Weld Heat Treatment. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 14771–14782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.M.Z.; Abdelazem, K.A.; El-Sayed Seleman, M.M.; Alzahrani, B.; Touileb, K.; Jouini, N.; El-Batanony, I.G.; Abd El-Aziz, H.M. Friction Stir Welding of 2205 Duplex Stainless Steel: Feasibility of Butt Joint Groove Filling in Comparison to Gas Tungsten Arc Welding. Materials 2021, 14, 4597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Huang, G.; Cao, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Li, W.; Wang, X.; Liu, Q. Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Dissimilar Friction Stir Welded AA2024-7075 Joints: Influence of Joining Material Direction. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2019, 766, 138368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Q.; Zhang, J.H.; Huq, M.J.; Hu, Z.L. Characterization of Microstructure, Mechanical Properties and Formability for Thermomechanical Treatment of Friction Stir Welded 2024-O Alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2019, 765, 138303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashaev, N.; Ventzke, V.; Çam, G. Prospects of Laser Beam Welding and Friction Stir Welding Processes for Aluminum Airframe Structural Applications. J. Manuf. Process. 2018, 36, 571–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albaijan, I.; Ahmed, M.M.Z.; El-Sayed Seleman, M.M.; Touileb, K.; Habba, M.I.A.; Fouad, R.A. Optimization of Bobbin Tool Friction Stir Processing Parameters of AA1050 Using Response Surface Methodology. Materials 2022, 15, 6886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gain, S.; Acharyya, S.K.; Sanyal, D.; Das, S.K. Influence of Welding Parameters on Austenitic Stainless Steel Pipe Weldments Produced by Friction Stir Welding. Trans. Indian Inst. Met. 2024, 77, 3927–3939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Li, S.; Ke, L.; Liu, J.; Kang, J. Microstructure and Fracture Behavior of Refill Friction Stir Spot Welded Joints of AA2024 Using a Novel Refill Technique. Metals 2019, 9, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.K.; Yusufzai, M.Z.K.; Mishra, S.; Singh, D.K. Influence of Multiple Friction Stir Welding Passes on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of AA2024 Age-Hardened Aluminum Alloy. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part L J. Mater. Des. Appl. 2024, 239, 1292–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, M.M.; Jamshidi Aval, H.; Jamaati, R.; Amirkhanlou, S.; Ji, S. Microstructure and Texture Evolution of Friction Stir Welded Dissimilar Aluminum Alloys: AA2024 and AA6061. J. Manuf. Process. 2018, 32, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Shen, Y. Numerical Simulation and Experimental Investigation of Friction Stir Lap Welding between Aluminum Alloys AA2024 and AA7075. J. Alloys Compd. 2016, 666, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeesh, P.; Venkatesh, K.M.; Rajkumar, V.; Avinash, P.; Arivazhagan, N.; Devendranath, R.K.; Narayanan, S. Studies on Friction Stir Welding of Aa 2024 and Aa 6061 Dissimilar Metals. Procedia Eng. 2014, 75, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.M.Z.; Jouini, N.; Alzahrani, B.; Seleman, M.M.E.S.; Jhaheen, M. Dissimilar Friction Stir Welding of AA2024 and AISI 1018: Microstructure and Mechanical Properties. Metals 2021, 11, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazaei Najafabadi, M.A.; Abdollah-Zadeh, A.; Mofid, M.A. Post-Weld Heat Treatment Effects on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Underwater Friction Stir-Welded AA 2024/6061 Lap Joints. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2025, 339, 130789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabraeili, R.; Jafarian, H.R.; Khajeh, R.; Park, N.; Kim, Y.; Heidarzadeh, A.; Eivani, A.R. Effect of FSW Process Parameters on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of the Dissimilar AA2024 Al Alloy and 304 Stainless Steel Joints. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2021, 814, 140981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathinasuriyan, C.; Puviyarasan, M.; Sankar, R.; Selvakumar, V. Effect of Process Parameters on Weld Geometry and Mechanical Properties in Friction Stir Welding of AA2024 and AA7075 Alloys. J. Alloys Metall. Syst. 2024, 7, 100091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashkovets, M.; Dell’Avvocato, G.; Contuzzi, N.; Palumbo, D.; Galietti, U.; Casalino, G. On the Role of Rotational Speed in P-FSSW Dissimilar Aluminum Alloys Lap Weld. Weld. World 2025, 69, 2095–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; Mishra, R.S.; Webb, S.; Chen, Y.L.; Carlson, B.; Herling, D.R.; Grant, G.J. Effect of Tool Design and Process Parameters on Properties of Al Alloy 6016 Friction Stir Spot Welds. J. Mater. Process Technol. 2011, 211, 972–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlich, A.; Avramovic-Cingara, G.; North, T.H. Stir Zone Microstructure and Strain Rate during Al 7075-T6 Friction Stir Spot Welding. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2006, 37, 2773–2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tozaki, Y.; Uematsu, Y.; Tokaji, K. Effect of Tool Geometry on Microstructure and Static Strength in Friction Stir Spot Welded Aluminium Alloys. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2007, 47, 2230–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palanivel, R.; Koshy Mathews, P.; Murugan, N.; Dinaharan, I. Effect of Tool Rotational Speed and Pin Profile on Microstructure and Tensile Strength of Dissimilar Friction Stir Welded AA5083-H111 and AA6351-T6 Aluminum Alloys. Mater. Des. 2012, 40, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ataya, S.; Ahmed, M.M.Z.; El-Sayed Seleman, M.M.; Hajlaoui, K.; Latief, F.H.; Soliman, A.M.; Elshaghoul, Y.G.Y.; Habba, M.I.A. Effective Range of FSSW Parameters for High Load-Carrying Capacity of Dissimilar Steel A283M-C/Brass CuZn40 Joints. Materials 2022, 15, 1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccini, J.M.; Svoboda, H.G. Effect of Pin Length on Friction Stir Spot Welding (FSSW) of Dissimilar Aluminum-Steel Joints. Procedia Mater. Sci. 2015, 9, 504–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awang, M.; Mucino, V.H. Energy Generation during Friction Stir Spot Welding (FSSW) of Al 6061-T6 Plates. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2010, 25, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, D.S.; Kahhal, P.; Kim, J.H. Optimization of Friction Stir Spot Welding Process Using Bonding Criterion and Artificial Neural Network. Materials 2023, 16, 3757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sehono, S.; Putra, I.R. Microstructure and Mechanical Performance of Friction Stir Spot Welding to Riveting Process Aluminum AA2024-T3 Plate: Effect of Tool Rotation Speed. AIP Conf. Proc. 2025, 3250, 070003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimoto, M.; Koga, S.; Abe, N.; Sato, S.Y.; Kokawa, H. Analysis of Plastic Flow of the Al Alloy Joint Produced by Friction Stir Spot Welding. Weld. Int. 2009, 23, 589–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton Savio Lewise, K.; Edwin Raja Dhas, J.; Pandiyarajan, R.; Sabarish, S. Metallurgical and Mechanical Investigation on FSSWed Dissimilar Aluminum Alloy. J. Alloys Metall. Syst. 2023, 2, 100010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Xiao, C.; Ojo, O.O. Dissimilar Friction Stir Spot Welding of AA2024-T3/AA7075-T6 Aluminum Alloys under Different Welding Parameters and Media. Def. Technol. 2021, 17, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadoun, A.M.; Wagih, A.; Fathy, A.; Essa, A.R.S. Effect of Tool Pin Side Area Ratio on Temperature Distribution in Friction Stir Welding. Results Phys. 2019, 15, 102814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratković, N.; Jovanović Pešić, Ž.; Arsić, D.; Pešić, M.; Džunić, D. Tool Geometry Effect on Material Flow and Mixture in FSW. Adv. Technol. Mater. 2022, 47, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seleman, M.M.E.S.; Ahmed, M.M.Z.; Ramadan, R.M.; Zaki, B.A. Effect of FSW Parameters on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of T-Joints between Dissimilar Al-Alloys. Int. J. Integr. Eng. 2022, 14, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfishawy, E.; Ahmed, M.M.Z.; El-Sayed Seleman, M.M. Additive Manufacturing of Aluminum Using Friction Stir Deposition. In TMS 2020 149th Annual Meeting & Exhibition Supplemental Proceedings; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 227–238. [Google Scholar]

- Mubiayi, M.P.; Akinlabi, E.T. An Overview on Friction Stir Spot Welding of Dissimilar Materials. In Transactions on Engineering Technologies: World Congress on Engineering and Computer Science 2014; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 537–549. ISBN 9789401772365. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, X.; Luan, Y.; Meng, X.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, N.; Liang, S.Y. Temperature Distribution and Mechanical Properties of FSW Medium Thickness Aluminum Alloy 2219. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 119, 7229–7241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, Y.J.; Qi, X.; Tang, W. Heat Transfer in Friction Stir Welding–Experimental and Numerical Studies. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. 2003, 125, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, H.; Hattel, J.; Wert, J. An Analytical Model for the Heat Generation in Friction Stir Welding. Model Simul. Mat. Sci. Eng 2004, 12, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan Kumar, R.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, A. Study on Effect of Tool Geometry on Energy and Temperature of Friction Stir Welding. Int. J. Civ. Eng. Technol. 2017, 8, 742–754. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, C.; Dymek, S.; Sommers, A. A Thermal Model of Friction Stir Welding in Aluminum Alloys. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2008, 48, 1120–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javadi, M.; Tajdari, M. Experimental Investigation of the Friction Coefficient between Aluminium and Steel. Mater. Sci.-Pol. 2006, 24, 305–310. [Google Scholar]

- Correia, A.N.; Santos, P.A.M.; Braga, D.F.O.; Baptista, R.; Infante, V. Effects of Friction Stir Welding Process Control and Tool Penetration on Mechanical Strength and Morphology of Dissimilar Aluminum-to-Polymer Joints. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2023, 7, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Bella, G.; Borsellino, C.; Chairi, M.; Campanella, D.; Buffa, G. Effect of Rotational Speed on Mechanical Properties of AA5083/AA6082 Friction Stir Welded T-Joints for Naval Applications. Metals 2024, 14, 1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, B.; Mahdian Rizi, A.A.; Abbasi, M.; Givi, M. Friction Stir Spot Vibration Welding: Improving the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Al5083 Joint. Metallogr. Microstruct. Anal. 2019, 8, 713–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Q.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, Z. The Effect of High-Temperature Deformation on the Mechanical Properties and Corrosion Resistance of the 2024 Aluminum Alloy Joint after Friction Stir Welding. Materials 2024, 17, 2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staszczyk, A.; Sawicki, J. Comparison of Mechanical Behaviour of Microstructures of 2024 Aluminium Alloy Containing Precipitates of Different Morphologies. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 743, 012052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrich, J.; Staron, P.; Karkar, A.; Roos, A.; Hanke, S. Precipitation Evolution in the Heat-Affected Zone and Coating Material of AA2024 Processed by Friction Surfacing. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2022, 24, 2201019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irmer, D.; Yildirim, C.; Sennour, M.; Esin, V.A.; Moussa, C. Effect of Second-Phase Precipitates on Deformation Microstructure in AA2024 (Al–Cu–Mg): Dislocation Substructures and Stored Energy. J. Mater. Sci. 2024, 59, 18978–19002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morozova, I.; Królicka, A.; Obrosov, A.; Yang, Y.; Doynov, N.; Weiß, S.; Michailov, V. Precipitation Phenomena in Impulse Friction Stir Welded 2024 Aluminium Alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 852, 143617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadtaheri, M.; Haddad-Sabzevar, M.; Mazinani, M. The Effects of Heat Treatment and Cold Working on the Microstructure of Aluminum Alloys Welded by Friction Stir Welding (FSW) Technique. Adv. Mater. Res. 2012, 409, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staszczyk, A.; Sawicki, J.; Adamczyk-Cieslak, B. A Study of Second-Phase Precipitates and Dispersoid Particles in 2024 Aluminum Alloy after Different Aging Treatments. Materials 2019, 12, 4168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habba, M.I.A.; Alsaleh, N.A.; Badran, T.E.; El-Sayed Seleman, M.M.; Ataya, S.; El-Nikhaily, A.E.; Abdul-Latif, A.; Ahmed, M.M.Z. Comparative Study of FSW, MIG, and TIG Welding of AA5083-H111 Based on the Evaluation of Welded Joints and Economic Aspect. Materials 2023, 16, 5124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Rayes, M.M.; Soliman, M.S.; Abbas, A.T.; Pimenov, D.Y.; Erdakov, I.N.; Abdel-Mawla, M.M. Effect of Feed Rate in FSW on the Mechanical and Microstructural Properties of AA5754 Joints. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 2019, 156176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudin, T.; Bozzi, S.; Brisset, F.; Azzeddine, H. Local Microstructure and Texture Development during Friction Stir Spot of 5182 Aluminum Alloy. Crystals 2023, 13, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalafe, W.H.; Sheng, E.L.; Bin Isa, M.R.; Omran, A.B.; Shamsudin, S.B. The Effect of Friction Stir Welding Parameters on the Weldability of Aluminum Alloys with Similar and Dissimilar Metals: Review. Metals 2022, 12, 2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padhy, G.K.; Wu, C.S.; Gao, S. Friction Stir Based Welding and Processing Technologies–Processes, Parameters, Microstructures and Applications: A Review. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2018, 34, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosturek, R.; Torzewski, J.; Wachowski, M.; Śnieżek, L. Effect of Welding Parameters on Mechanical Properties and Microstructure of Friction Stir Welded AA7075-T651 Aluminum Alloy Butt Joints. Materials 2022, 15, 5950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urrego, L.F.; García-Beltrán, O.; Arzola, N.; Araque, O. Mechanical Fracture of Aluminium Alloy (AA 2024-T4), Used in the Manufacture of a Bioproducts Plant. Metals 2023, 13, 1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Elements (%) | Cu | Mg | Mn | Fe | Si | Zn | Cr | Ti | Al |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wt.% | 3.8 | 1.2 | 0.30 | 0.5 | 0.50 | 0.25 | 0.10 | 0.15 | Bal. |

| Yield Stress (MPa) | Ultimate Tensile Strength (MPa) | Hardness (HV) |

|---|---|---|

| 279 ± 4.5 | 420 ± 6.4 | 111 ± 6.0279 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Elshaghoul, Y.G.Y.; Shalaby, M.F.Y.; El-Sayed Seleman, M.M.; Elkelity, A.; Reyad, H.A.; Ataya, S. The Role of Rotational Tool Speed in the Joint Performance of AA2024-T4 Friction Stir Spot Welds at a Short 3-Second Dwell Time. Crystals 2025, 15, 1054. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121054

Elshaghoul YGY, Shalaby MFY, El-Sayed Seleman MM, Elkelity A, Reyad HA, Ataya S. The Role of Rotational Tool Speed in the Joint Performance of AA2024-T4 Friction Stir Spot Welds at a Short 3-Second Dwell Time. Crystals. 2025; 15(12):1054. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121054

Chicago/Turabian StyleElshaghoul, Yousef G. Y., Mahmoud F. Y. Shalaby, Mohamed M. El-Sayed Seleman, Ahmed Elkelity, Hagar A. Reyad, and Sabbah Ataya. 2025. "The Role of Rotational Tool Speed in the Joint Performance of AA2024-T4 Friction Stir Spot Welds at a Short 3-Second Dwell Time" Crystals 15, no. 12: 1054. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121054

APA StyleElshaghoul, Y. G. Y., Shalaby, M. F. Y., El-Sayed Seleman, M. M., Elkelity, A., Reyad, H. A., & Ataya, S. (2025). The Role of Rotational Tool Speed in the Joint Performance of AA2024-T4 Friction Stir Spot Welds at a Short 3-Second Dwell Time. Crystals, 15(12), 1054. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121054