Experimental Study on the Influence of Waste Stone Powder on the Properties of Alkali-Activated Slag/Metakaolin Cementitious Materials

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Scheme

2.1. Raw Materials

2.1.1. Powder Raw Materials

2.1.2. Alkali Activator Materials

2.2. Experimental Design

2.2.1. Material Mix Proportion

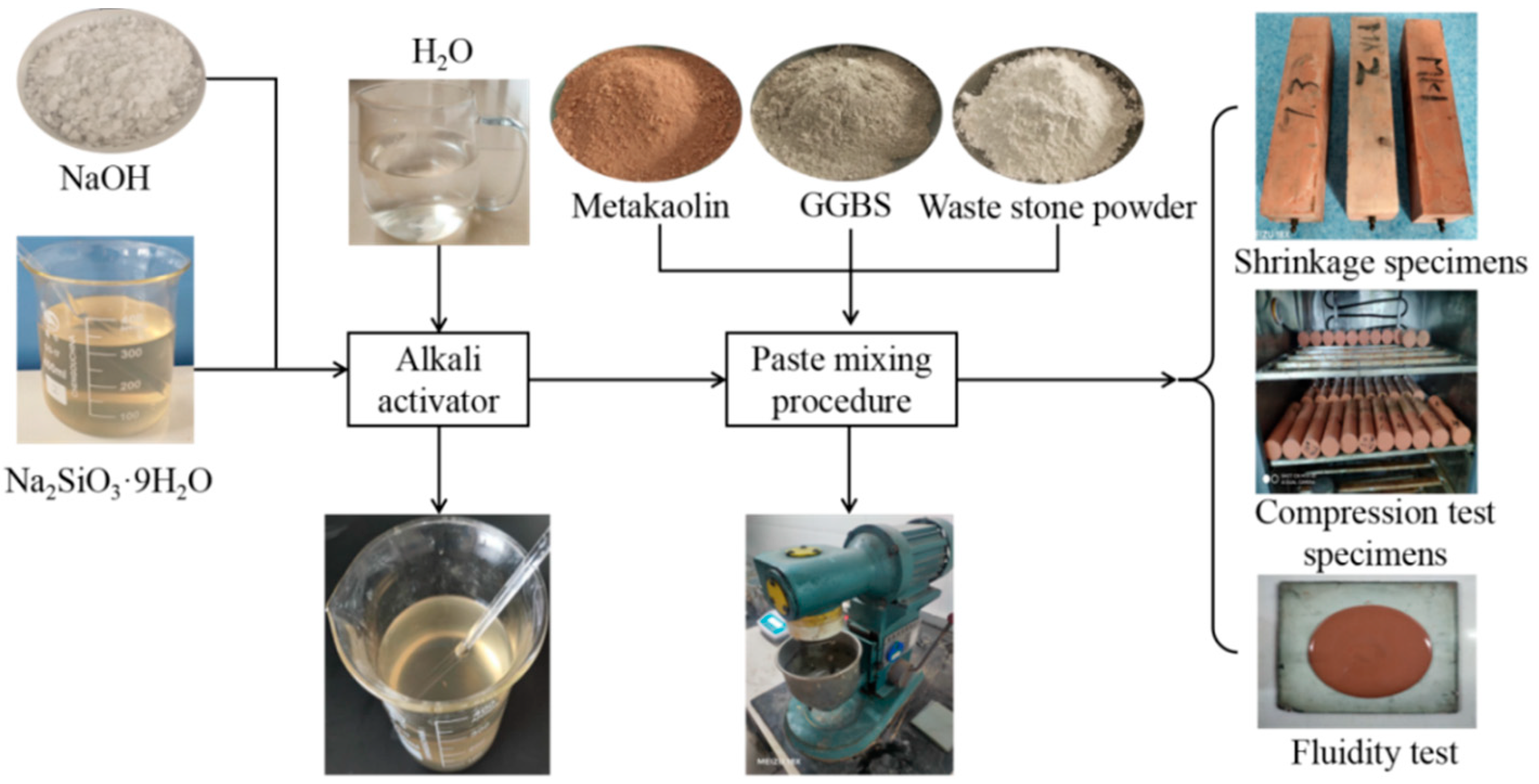

2.2.2. Specimen Preparation Process

2.3. Test Instruments and Methods

3. Experimental Results and Analysis

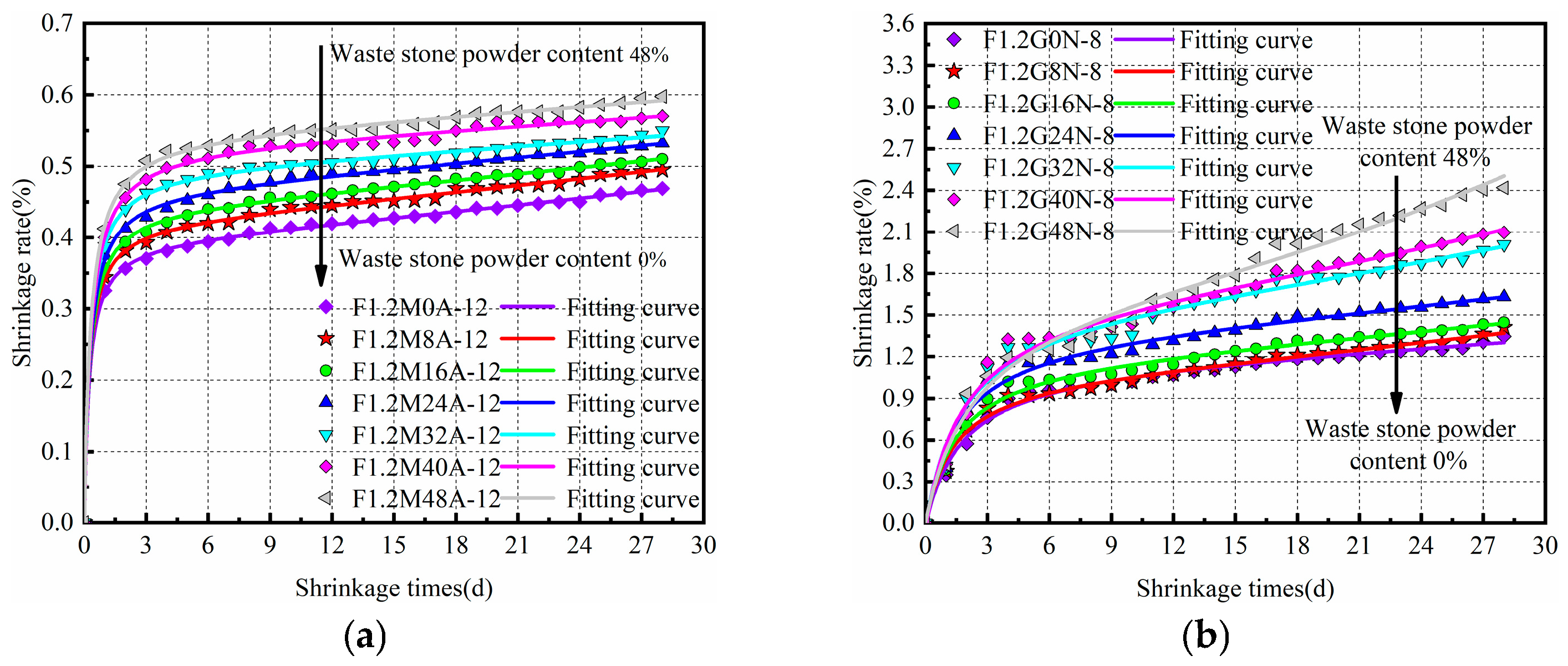

3.1. Drying Shrinkage Properties of Hardened Paste

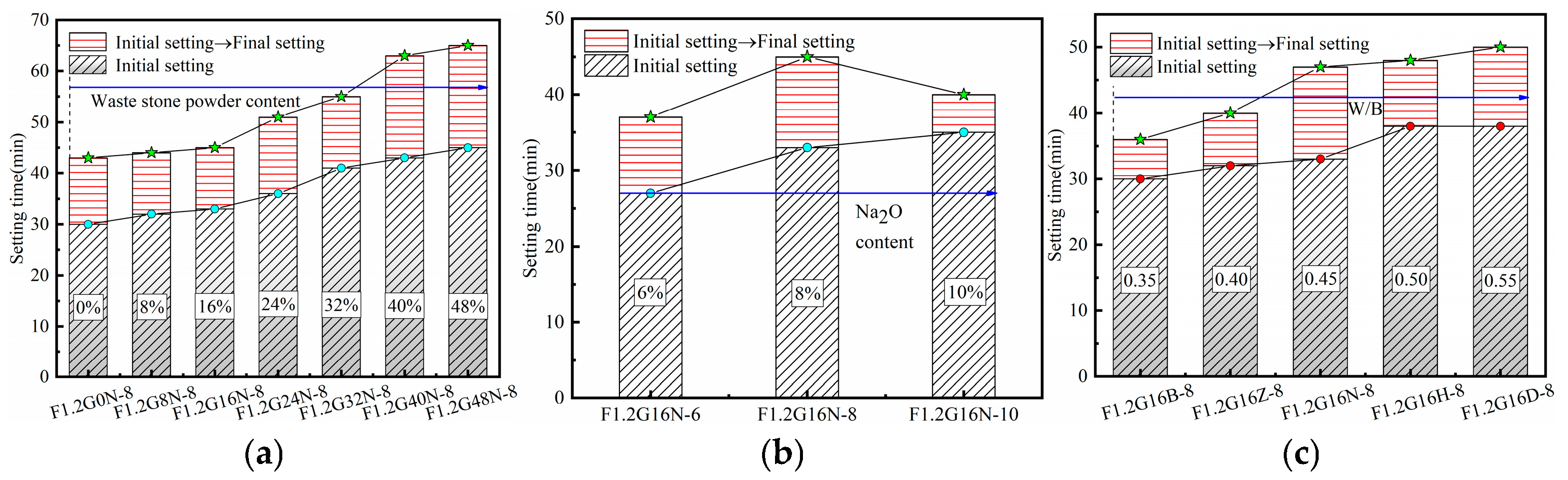

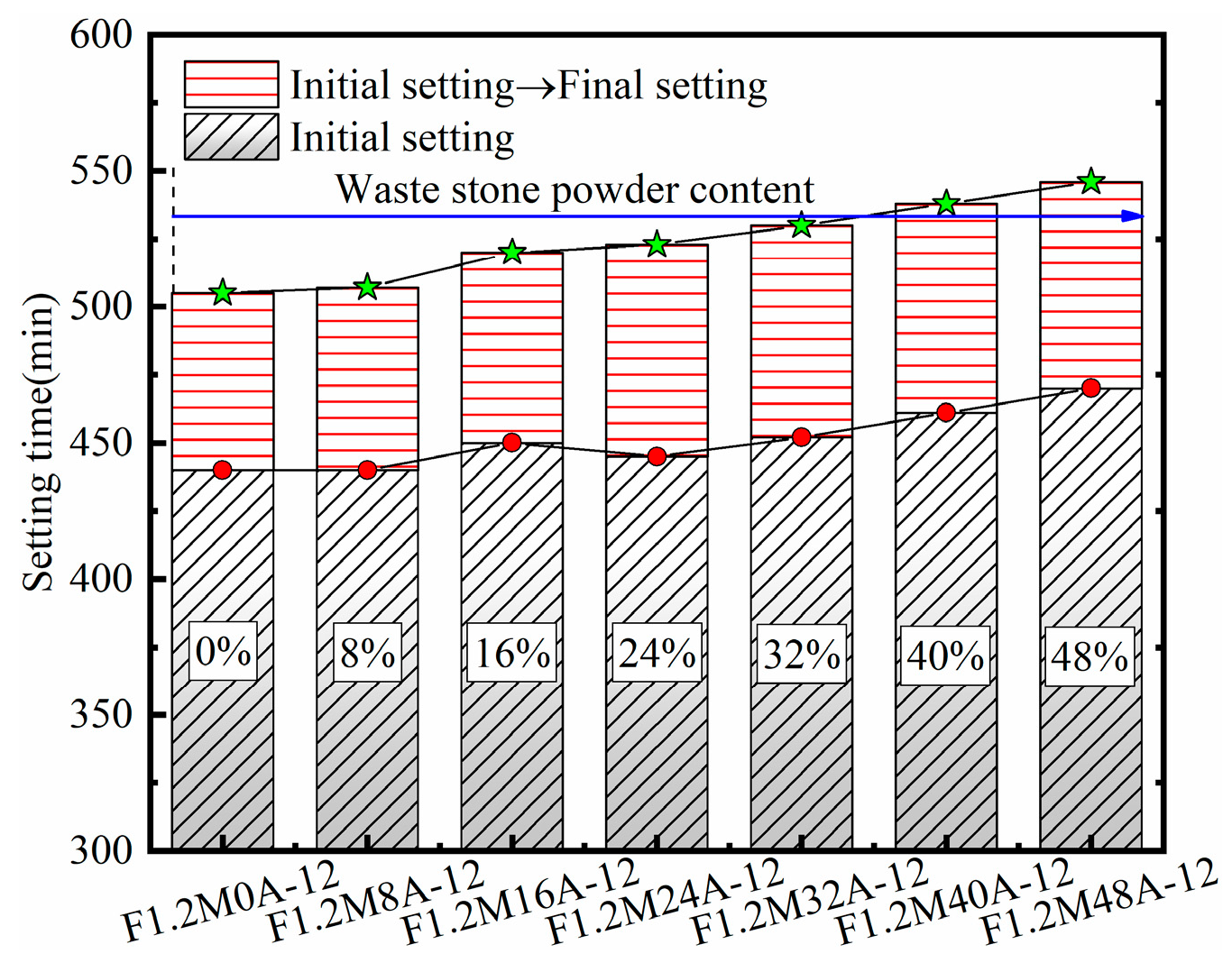

3.2. Setting Time

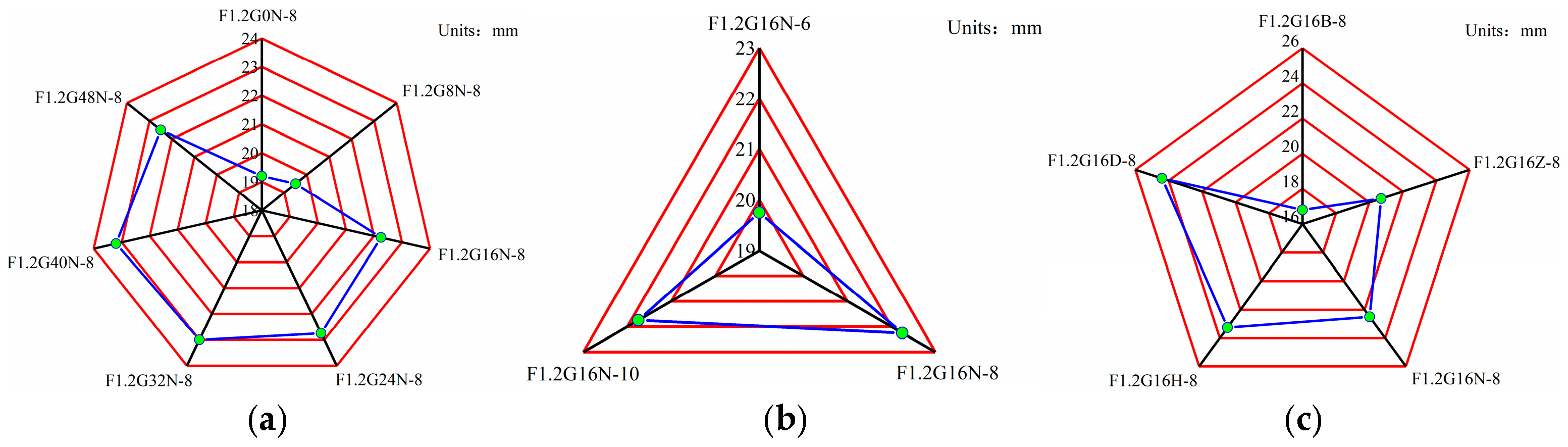

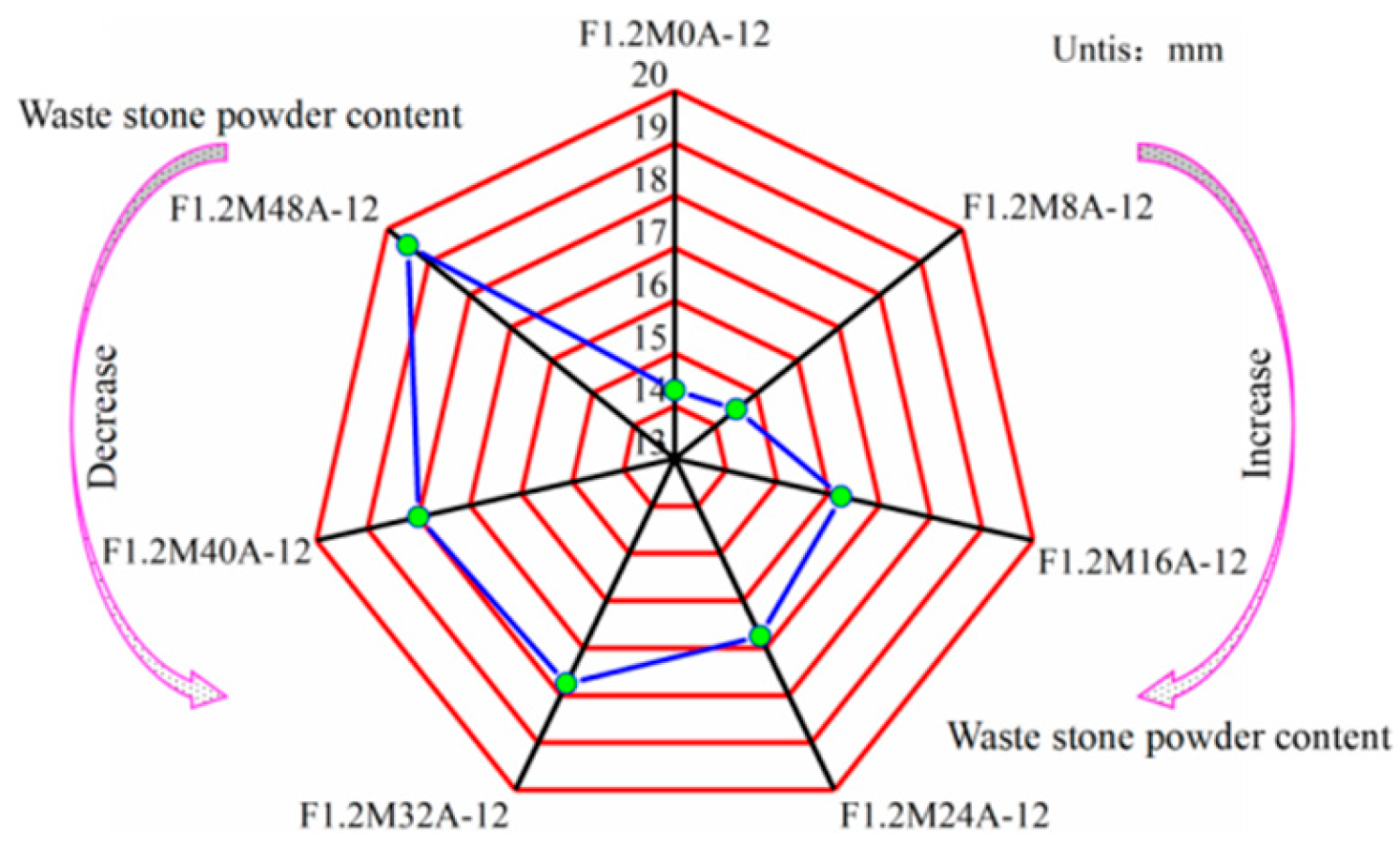

3.3. Fluidity Results of Paste

3.4. Uniaxial Compression Performance of Cementitious Materials

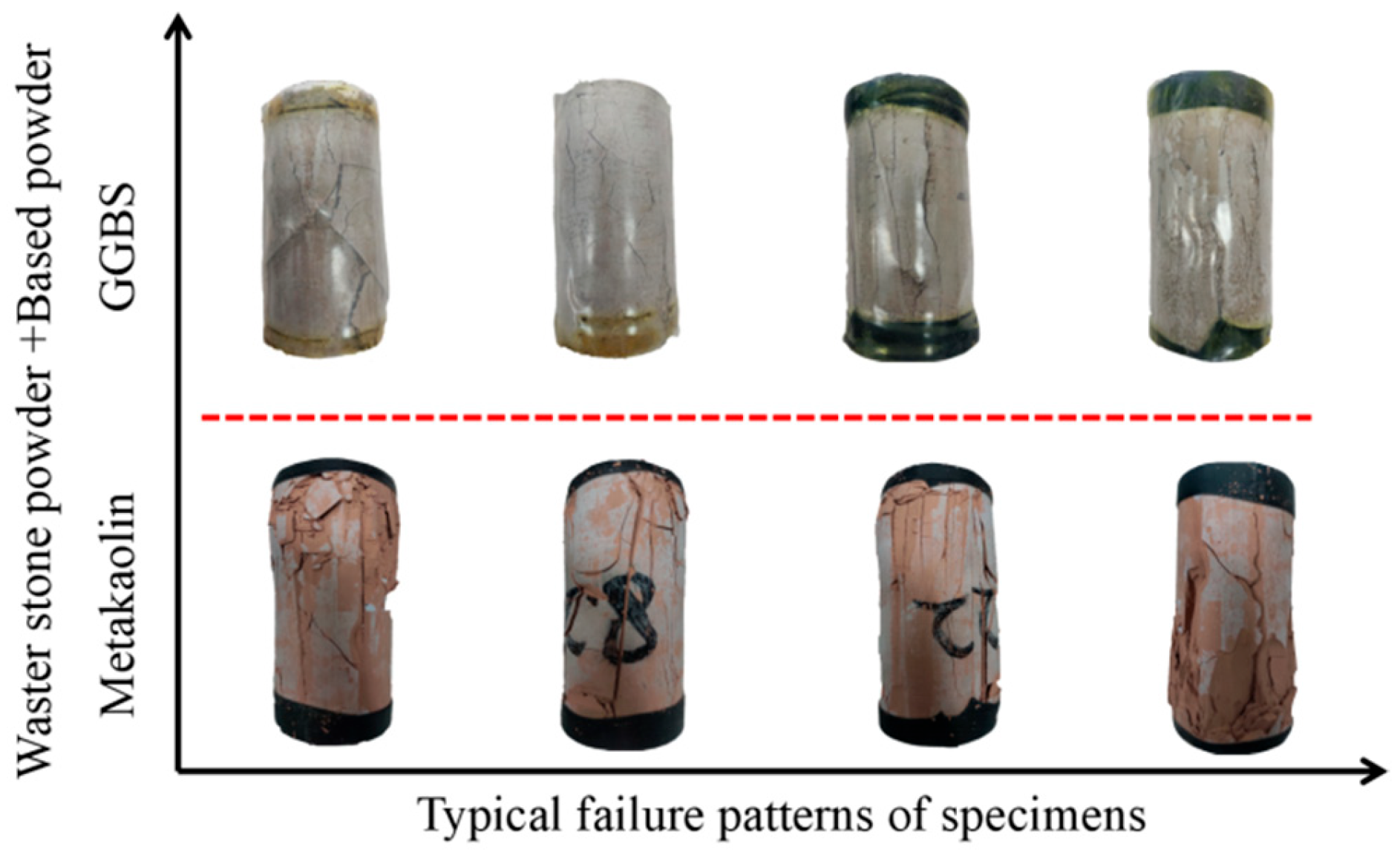

3.4.1. Specimen Loading Process and Failure Characteristics

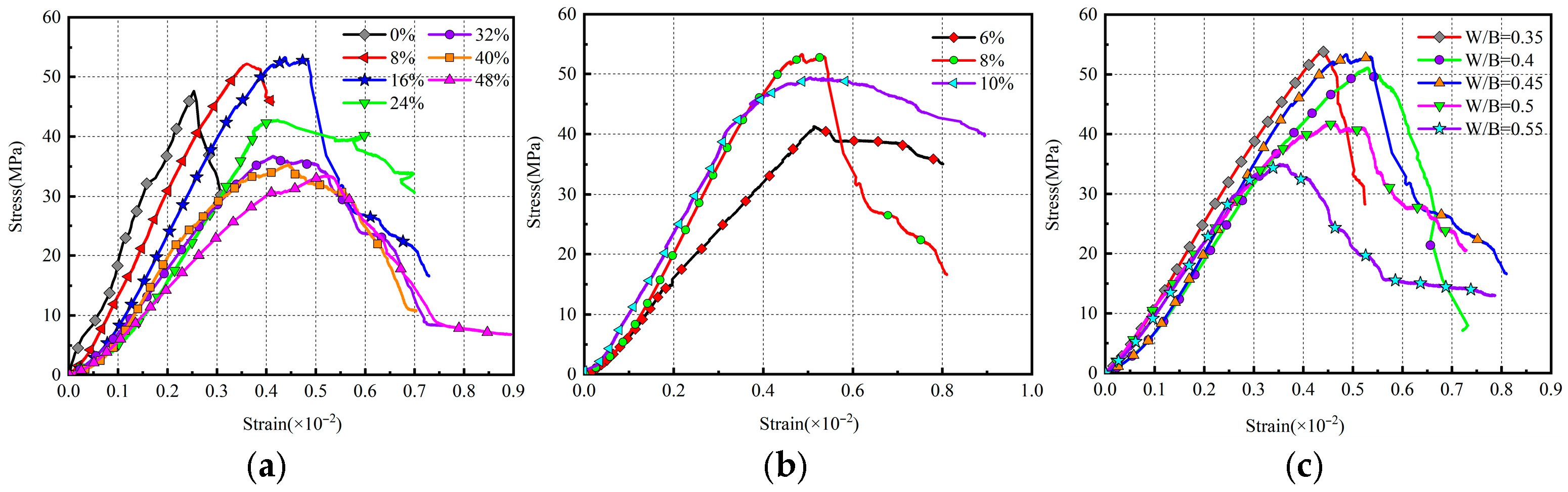

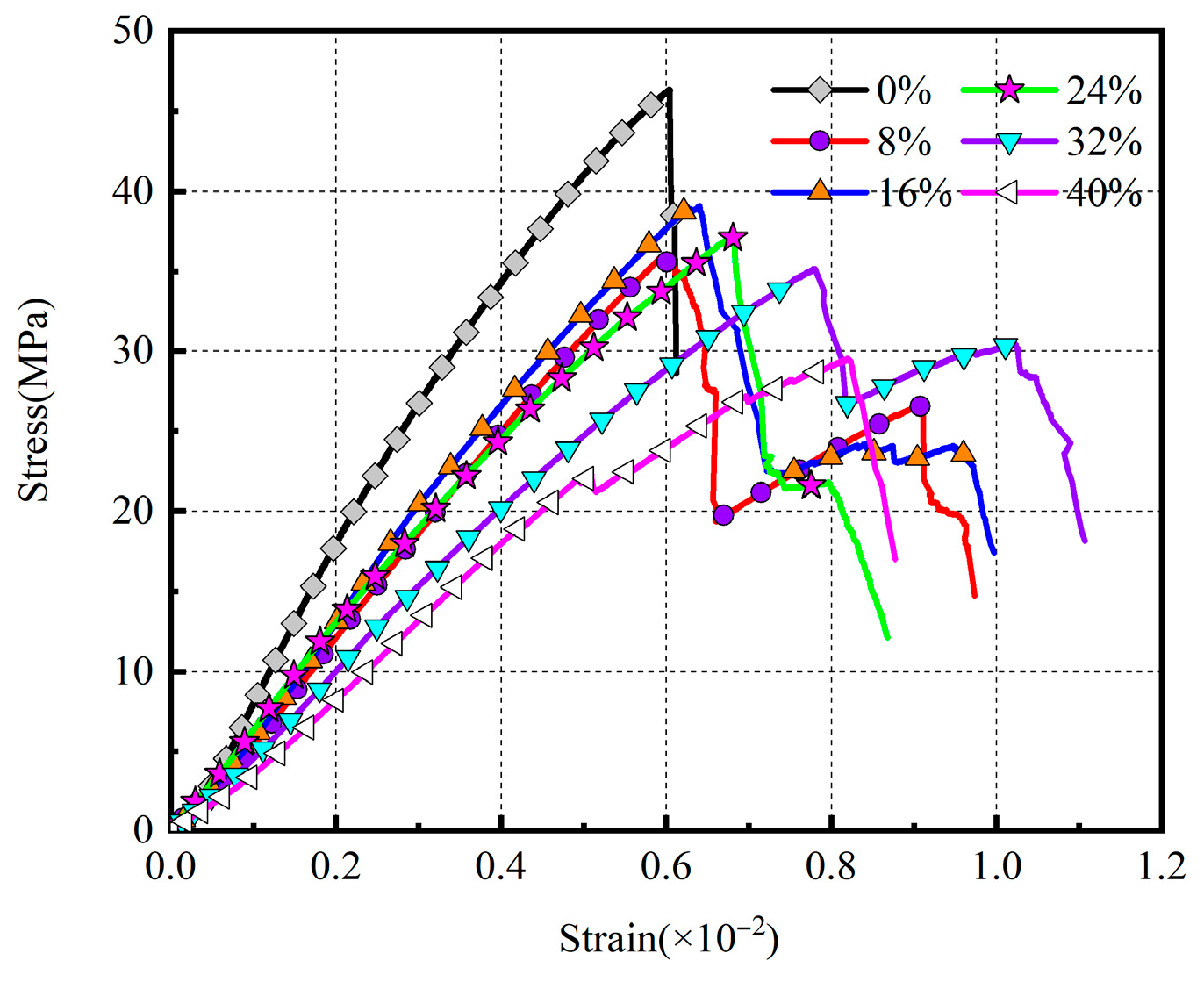

3.4.2. The Stress–Strain Curve of the Specimen

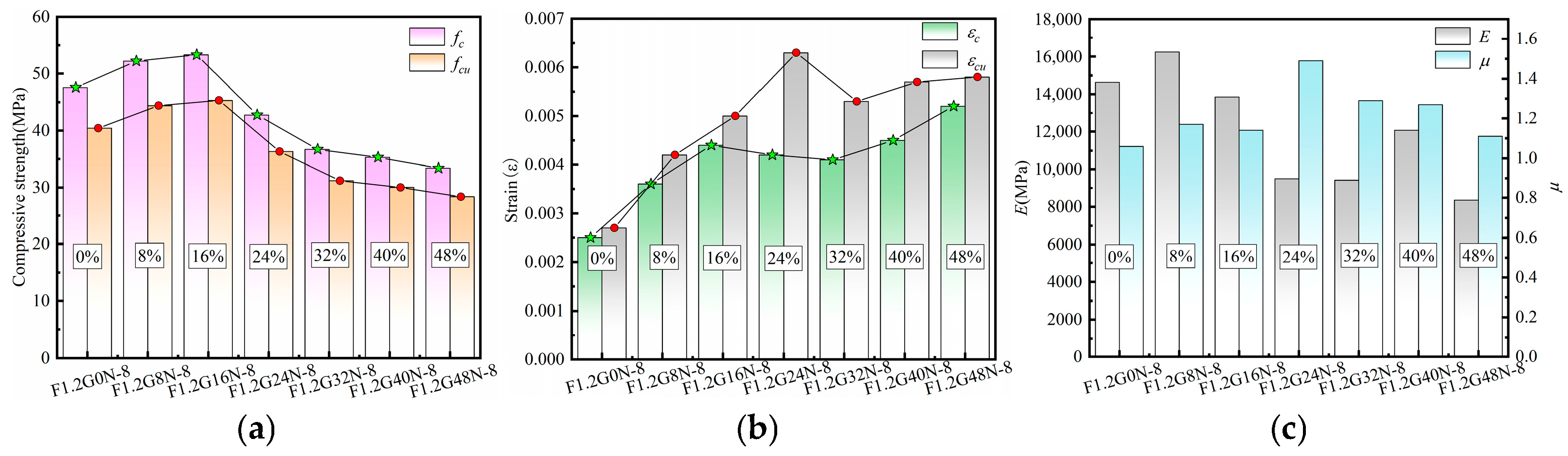

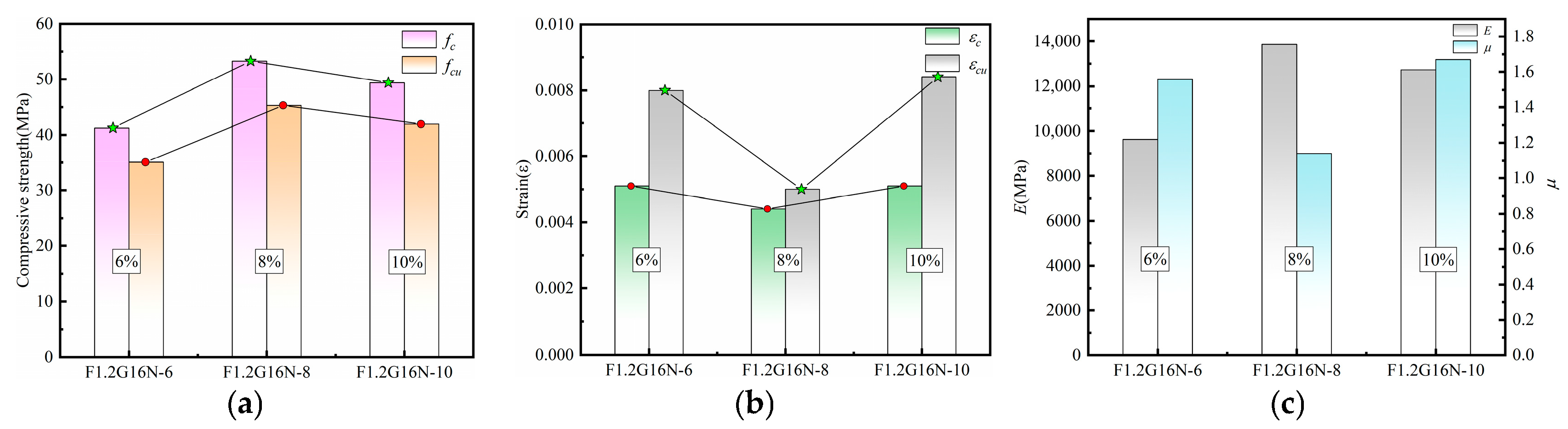

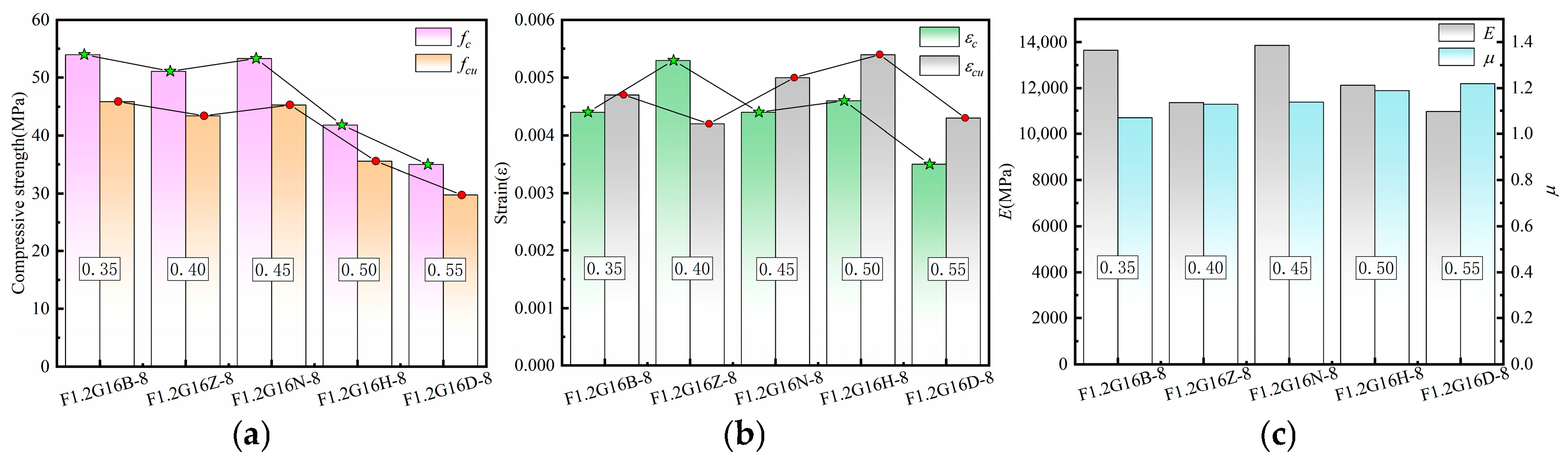

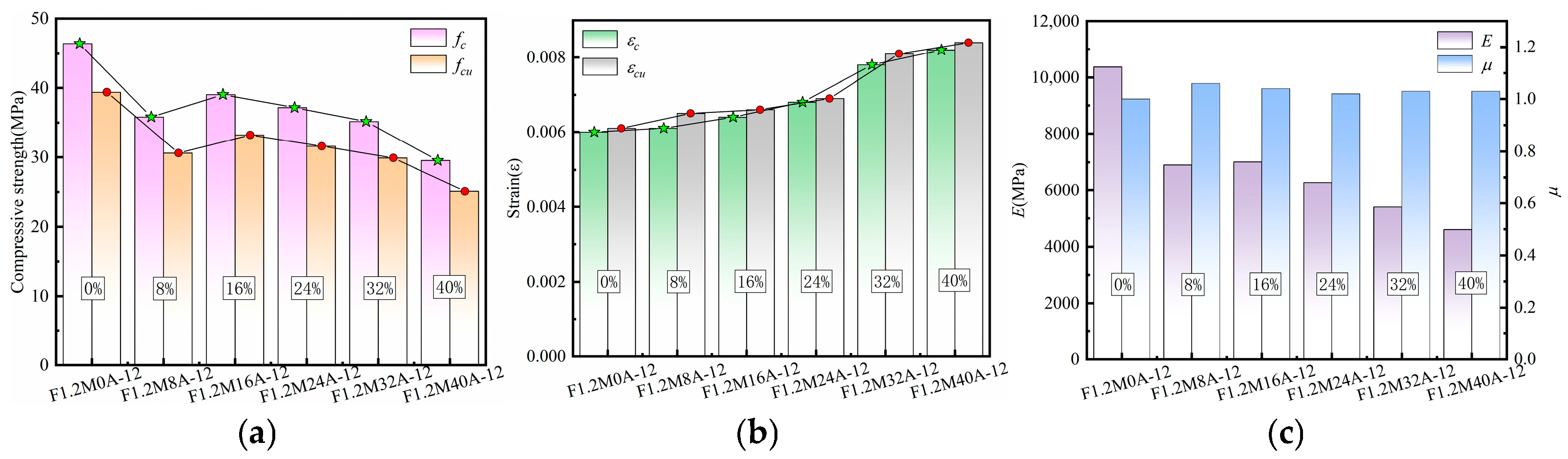

3.4.3. Characteristic Parameters Analysis of Stress–Strain Curves

3.4.4. Analysis of Parameter Effects on Specimen Characteristics

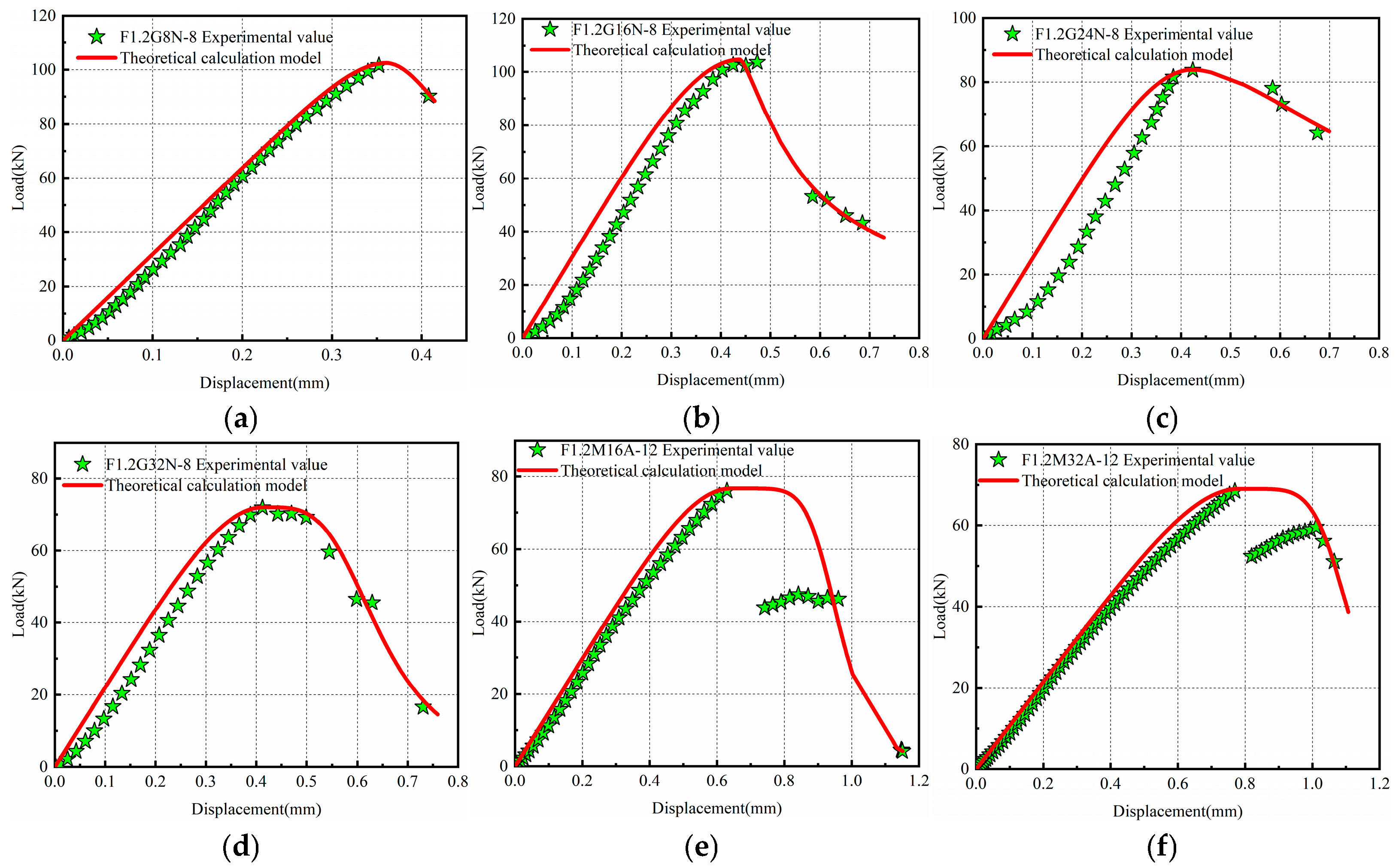

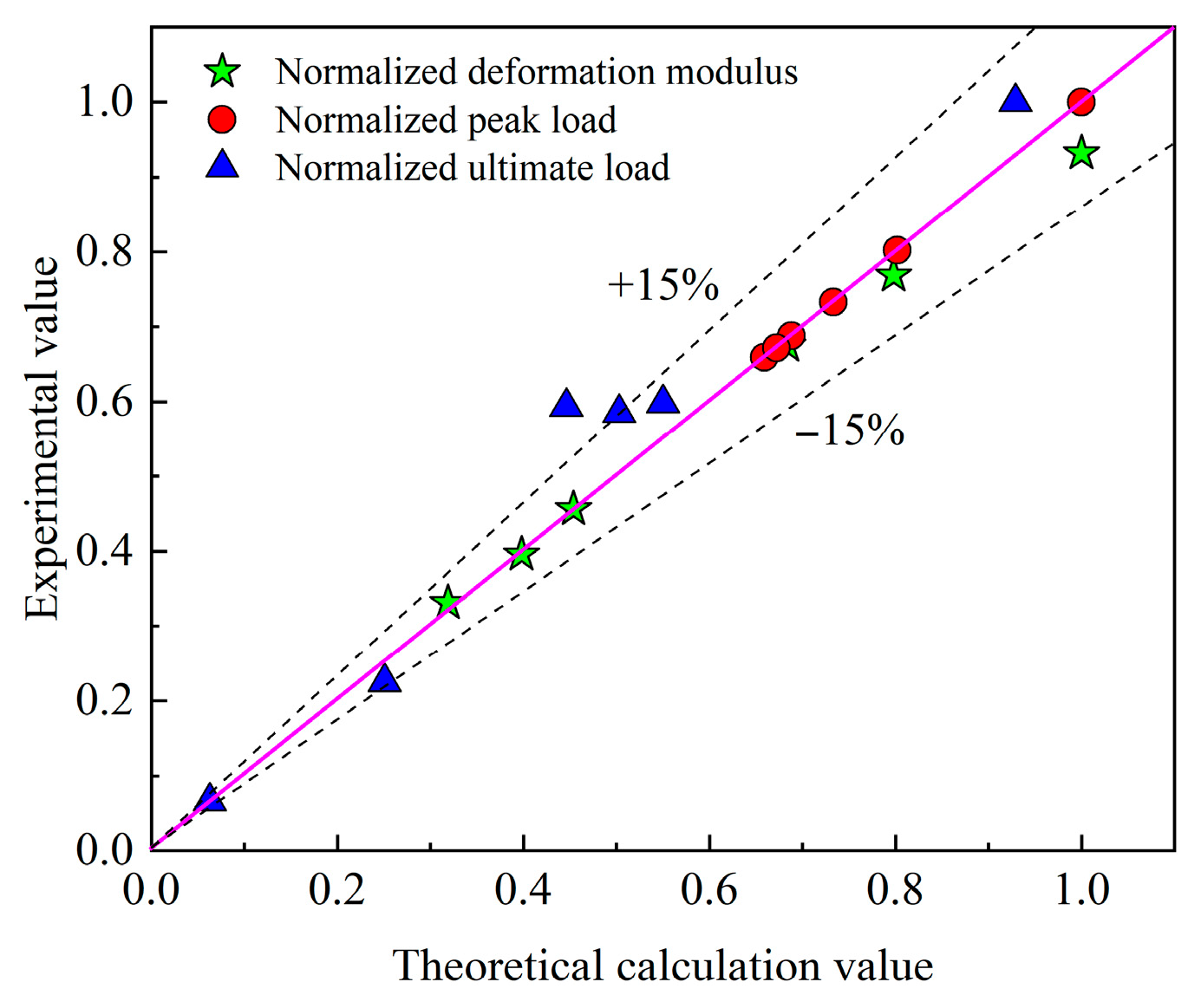

3.5. Computational Model for Complete Load–Displacement Curves of Specimens

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, L.G.; Huang, Z.H.; Tan, Y.P.; Kwan, A.K.H.; Liu, F. Use of marble dust as paste replacement for recycling waste and improving durability and dimensional stability of mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 166, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, A.; Kalla, P.; Csetenyi, L.J. Sustainable use of marble slurry in concrete. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 94, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyamac, K.E.; Ghafari, E.; Ince, R. Development of eco-efficient self-compacting concrete with waste marble powder using the response surface method. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 144, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musaddiq Laskar, S.; Talukdar, S. Development of ultrafine slag-based geopolymer mortar for use as repairing mortar. J. Mater. Civil. Eng. 2017, 29, 04016292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simão, L.; Hotza, D.; Ribeiro, M.J.; Novais, R.M.; Montedo, O.R.K.; Raupp-Pereira, F. Development of new geopolymers based on stone cutting waste. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 257, 119525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyamaç, K.E.; Aydin, A.B. Concrete properties containing fine aggregate marble powder. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2015, 19, 2208–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Fu, C.; Yang, G. Influence of dolomite on the properties and microstructure of alkali-activated slag with and without pulverized fly ash, Cement. Concrete. Comp. 2019, 103, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Kang, X.; Deng, J.; Yang, K.; Jiang, S.; Yang, C. Chemical and physical effects of high-volume limestone powder on sodium silicate-activated slag cement (AASC). Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 292, 123257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayiha, B.N.; Billong, N.; Yamb, E.; Kaze, R.C.; Nzengwa, R. Effect of limestone dosages on some properties of geopolymer from thermally activated halloysite. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 217, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, Z.; Sun, R.; Huang, F.; Yi, Z.; Yuan, Z.; Wen, J.; Lu, L.; Yang, Z. Effect of different lithological stone powders on properties of cementitious materials. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 289, 125820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Qiu, X.; Yang, W.; Ma, C. Study on properties and mechanism of alkali-activated geopolymer cementitious materials of marble waste powder. Dev. Built. Environ. 2023, 16, 100249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.A. Enhancement of engineering properties of slag-cement based self-compacting mortar with dolomite powder. J. Build. Eng. 2019, 24, 100738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perná, I.; Novotná, M.; Řimnáčová, D.; Šupová, M. New metakaolin-based geopolymers with the addition of different types of waste stone powder. Crystals 2021, 11, 983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wang, C.; Wu, J.; Gao, M. Calcined coal gangue fines as the substitute for slag in the production of alkali-activated cements and its mechanism. Processes 2022, 10, 1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakmak, T.; Gürbüz, A.; Kurt, Z.; Ustabaş, İ. Mechanical and microstructural properties of mortars: Obsidian powder effect. J. Sustain. Const. Mater. Technol. 2024, 9, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barış, K.E. One-part alkali-activated mortars based on clay brick waste, natural pozzolan waste, and marble powder waste. J. Sustain. Const. Mater. Technol. 2024, 9, 391–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biel, O.; Rożek, P.; Florek, P.; Mozgawa, W.; Król, M. Alkaline activation of kaolin group minerals. Crystals 2020, 10, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 50081-2019; Standard for Test Methods of Concrete Physical and Mechanical Properties. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2019. (In Chinese)

- JGJ/T70-2009; Standard for Test Method of Basic Properties of Construction Mortar. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2009. (In Chinese)

- GB/T1346-2011; Test Methods for Water Requirement of Normal Consistency, Setting Time and Soundness of the Portland Cement. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2011. (In Chinese)

- GB/T 8077-2012; Test Methods for Uniformity of Concrete Admixtures. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2012. (In Chinese)

- Zhang, B.; Chen, Y.; Ma, Y.; Ji, T. Effect of hydration assemblage on the autogenous shrinkage of alkali-activated slag mortars. Mag. Concr. Res. 2023, 75, 447–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, W.; Huang, W. Effect of dosage of sodium carbonate on the strength and drying shrinkage of sodium hydroxide based alkali-activated slag paste. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 179, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Zhu, Z.; Pu, S.; Wan, Y.; Huo, W.; Song, S.; Zhang, J.; Yao, K.; Hu, L. Efficient use of steel slag in alkali-activated fly ash-steel slag-ground granulated blast furnace slag ternary blends. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 259, 119814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Radlińska, A. Shrinkage mitigation strategies in alkali-activated slag. Cem. Concr. Res. 2017, 101, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, H.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, H. Drying shrinkage behavior of hybrid alkali activated cement (HAAC) mortars. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 316, 126068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z.Y.; Yu, Q.; Ji, Y.D.; Gauvin, F.; Voets, I.K. Mitigating shrinkage of alkali activated slag with biofilm. Cem. Concr. Res. 2020, 138, 106234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheah, C.B.; Tan, L.E.; Ramli, M. Recent advances in slag-based binder and chemical activators derived from industrial by-products-A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 272, 121657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, S.A. Effect of the activator dose on the compressive strength and accelerated carbonation resistance of alkali silicate-activated slag/metakaolin blended materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 98, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.F.; Chen, J.P.; Yang, L.; Qi, Y.H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, C. Influence mechanism of limestone powder on red mud-based grouting material. Chin. J. Eng. 2021, 40, 768–777. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, W.; Huang, W. Effect of dosage of alkaline activator on the properties of alkali-activated slag pastes. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 2018, 8407380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neville, A.M. Properties of Concrete; Pearson: Harlow, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Tan, K.; Xu, J.; Li, W. Mechanical performance experiment and bearing capacity calculation of middle long columns made of angle steel restrained concrete and subjected to axial compression. J. Exp. Mech. 2016, 31, 57–66. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Komnitsas, K.; Soultana, A.; Bartzas, G. Marble waste valorization through alkali activation. Minerals 2021, 11, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voyiadjis, G.Z.; Kattan, P.I. Damage Mechanics; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Y.; Peng, G.; Huang, C.; Luo, X.; Peng, Z. Damage evolution study of concrete under joint action of compression and shear. Hydro-Sci. Eng. 2018, 2, 112–119. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

| Sample | SiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | CaO | MgO | K2O |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GGBS | 27.88 | 15.11 | 0.35 | 41.20 | 9.78 | 0.48 |

| Waste stone powder | 0.23 | 0.17 | 0.09 | 97.62 | 1.77 | 0.03 |

| Metakaolin | 47.56 | 45.96 | 2.89 | 0.44 | 0.16 | 0.35 |

| Material Name | SiO2 Content | Na2O Content | Water Content | Be | Modulus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water glass | 26.8% | 9.18% | 57.04% | 39.5° | 3.22 |

| Experiment Number | Waste Stone Powder Content | Na2O Content | Modulus | W/B | Waste Stone Powder | GGBS | Metakaolin | Water Glass | NaOH | Water |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | - | - | g | g | g | g | g | g | |

| F1.2G0N-8 | 0 | 8 | 1.2 | 0.45 | - | 500 | - | 167.04 | 33.29 | 117.28 |

| F1.2G8N-8 | 8 | 8 | 1.2 | 0.45 | 40 | 460 | - | 167.04 | 33.29 | 117.28 |

| F1.2G16N-8 | 16 | 8 | 1.2 | 0.45 | 80 | 420 | - | 167.04 | 33.29 | 117.28 |

| F1.2G24N-8 | 24 | 8 | 1.2 | 0.45 | 120 | 380 | - | 167.04 | 33.29 | 117.28 |

| F1.2G32N-8 | 32 | 8 | 1.2 | 0.45 | 160 | 340 | - | 167.04 | 33.29 | 117.28 |

| F1.2G40N-8 | 40 | 8 | 1.2 | 0.45 | 200 | 300 | - | 167.04 | 33.29 | 117.28 |

| F1.2G48N-8 | 48 | 8 | 1.2 | 0.45 | 240 | 260 | - | 167.04 | 33.29 | 117.28 |

| F1.2M0A-12 | 8 | 12 | 1.2 | 0.55 | 0 | - | 500 | 250.57 | 49.94 | 113.42 |

| F1.2M8A-12 | 8 | 12 | 1.2 | 0.55 | 40 | - | 460 | 250.57 | 49.94 | 113.42 |

| F1.2M16A-12 | 16 | 12 | 1.2 | 0.55 | 80 | - | 420 | 250.57 | 49.94 | 113.42 |

| F1.2M24A-12 | 24 | 12 | 1.2 | 0.55 | 120 | - | 380 | 250.57 | 49.94 | 113.42 |

| F1.2M32A-12 | 32 | 12 | 1.2 | 0.55 | 160 | - | 340 | 250.57 | 49.94 | 113.42 |

| F1.2M40A-12 | 40 | 12 | 1.2 | 0.55 | 200 | - | 300 | 250.57 | 49.94 | 113.42 |

| F1.2M48A-12 | 48 | 12 | 1.2 | 0.55 | 240 | - | 260 | 250.57 | 49.94 | 113.42 |

| F1.2G16N-6 | 16 | 6 | 1.2 | 0.45 | 80 | 420 | - | 125.28 | 24.97 | 144.21 |

| F1.2G16N-10 | 16 | 10 | 1.2 | 0.45 | 80 | 420 | - | 208.81 | 41.61 | 90.36 |

| F1.2G16B-8 | 16 | 8 | 1.2 | 0.35 | 80 | 420 | - | 167.04 | 33.29 | 67.27 |

| F1.2G16Z-8 | 16 | 8 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 80 | 420 | - | 167.04 | 33.29 | 92.28 |

| F1.2G16H-8 | 16 | 8 | 1.2 | 0.5 | 80 | 420 | - | 167.04 | 33.29 | 142.28 |

| F1.2G16D-8 | 16 | 8 | 1.2 | 0.55 | 80 | 420 | - | 167.04 | 33.29 | 167.27 |

| Sample | χ | α | β | γ | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1.2G0N-8 | −0.03185 | −0.0047 | 0.846 | 1.535 | 0.990 |

| F1.2G8N-8 | −0.02057 | −0.0080 | 0.909 | 1.237 | 0.989 |

| F1.2G16N-8 | −0.02609 | −0.0058 | 0.815 | 1.203 | 0.986 |

| F1.2G24N-8 | −0.03310 | −0.0050 | 0.715 | 1.080 | 0.983 |

| F1.2G32N-8 | −0.03529 | −0.0059 | 0.628 | 1.094 | 0.983 |

| F1.2G40N-8 | −0.04351 | −0.0064 | 0.612 | 1.107 | 0.984 |

| F1.2G48N-8 | 0.00102 | −0.0086 | 0.592 | 1.364 | 0.988 |

| F1.2M0A-12 | 0.00004 | −0.0142 | 2.513 | 0.610 | 0.999 |

| F1.2M8A-12 | 0.00003 | −0.0127 | 2.354 | 0.586 | 0.999 |

| F1.2M16A-12 | 0.00006 | −0.0111 | 2.249 | 0.601 | 0.999 |

| F1.2M24A-12 | 0.00011 | −0.0094 | 2.120 | 0.602 | 0.999 |

| F1.2M32A-12 | −0.00006 | −0.0065 | 2.005 | 0.562 | 0.999 |

| F1.2M40A-12 | −0.00003 | −0.0055 | 1.887 | 0.613 | 0.998 |

| F1.2M48A-12 | −0.00012 | −0.0057 | 1.829 | 0.569 | 0.999 |

| Specimen Number | fc | fcu | εc | εcu | E | μ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MPa | MPa | ε | ε | MPa | - | |

| F1.2G0N-8 | 47.57 | 40.44 | 0.0025 | 0.0027 | 14,637.53 | 1.06 |

| F1.2G8N-8 | 52.22 | 44.39 | 0.0036 | 0.0042 | 16,244.40 | 1.17 |

| F1.2G16N-8 | 53.31 | 45.31 | 0.0044 | 0.005 | 13,854.36 | 1.14 |

| F1.2G24N-8 | 42.74 | 36.33 | 0.0042 | 0.0063 | 9502.54 | 1.49 |

| F1.2G32N-8 | 36.70 | 31.19 | 0.0041 | 0.0053 | 9425.37 | 1.29 |

| F1.2G40N-8 | 35.31 | 30.02 | 0.0045 | 0.0057 | 12,073.04 | 1.27 |

| F1.2G48N-8 | 33.40 | 28.38 | 0.0052 | 0.0058 | 8342.17 | 1.11 |

| F1.2M0A-12 | 46.37 | 39.41 | 0.006 | 0.0061 | 10,372.96 | 1 |

| F1.2M8A-12 | 35.82 | 30.60 | 0.0061 | 0.0065 | 6899.39 | 1.06 |

| F1.2M16A-12 | 39.07 | 33.21 | 0.0064 | 0.0066 | 7008.23 | 1.04 |

| F1.2M24A-12 | 37.19 | 31.61 | 0.0068 | 0.0069 | 6280.57 | 1.02 |

| F1.2M32A-12 | 35.16 | 29.89 | 0.0078 | 0.0081 | 5403.76 | 1.03 |

| F1.2M40A-12 | 29.52 | 25.10 | 0.0082 | 0.0084 | 4601.63 | 1.03 |

| F1.2G16N-6 | 41.27 | 35.08 | 0.0051 | 0.008 | 9631.47 | 1.56 |

| F1.2G16N-10 | 49.37 | 41.96 | 0.0051 | 0.0084 | 12,723.09 | 1.67 |

| F1.2G16B-8 | 53.98 | 45.89 | 0.0044 | 0.0047 | 13,640.99 | 1.07 |

| F1.2G16Z-8 | 51.09 | 43.43 | 0.0053 | 0.0042 | 11,377.91 | 1.13 |

| F1.2G16H-8 | 41.83 | 35.56 | 0.0046 | 0.0054 | 12,133.09 | 1.19 |

| F1.2G16D-8 | 34.99 | 29.74 | 0.0035 | 0.0043 | 10,969.11 | 1.22 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, T.; Wang, H.; Li, C. Experimental Study on the Influence of Waste Stone Powder on the Properties of Alkali-Activated Slag/Metakaolin Cementitious Materials. Crystals 2025, 15, 1039. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121039

Wang T, Wang H, Li C. Experimental Study on the Influence of Waste Stone Powder on the Properties of Alkali-Activated Slag/Metakaolin Cementitious Materials. Crystals. 2025; 15(12):1039. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121039

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Tongkuai, Haibo Wang, and Chunmei Li. 2025. "Experimental Study on the Influence of Waste Stone Powder on the Properties of Alkali-Activated Slag/Metakaolin Cementitious Materials" Crystals 15, no. 12: 1039. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121039

APA StyleWang, T., Wang, H., & Li, C. (2025). Experimental Study on the Influence of Waste Stone Powder on the Properties of Alkali-Activated Slag/Metakaolin Cementitious Materials. Crystals, 15(12), 1039. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121039