Colorimetry Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Sulfur-Rich Lapis Lazuli

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

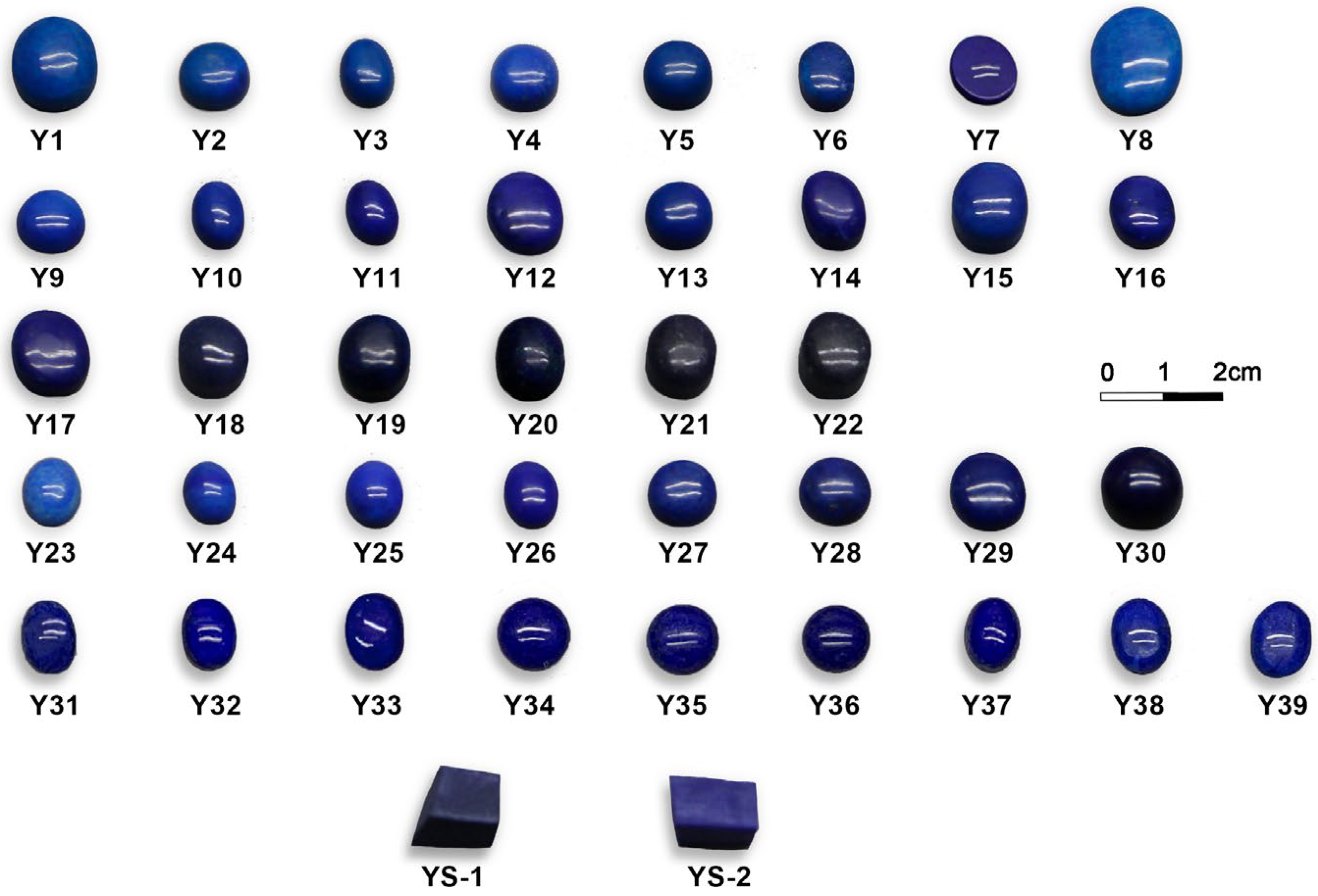

2.1. Samples

2.2. Colorimetric Measurements

2.3. Mineralogical and Compositional Study

2.4. Spectroscopic Study

3. Results

3.1. Colorimetric Quantification and Classification

3.2. Mineral Composition Analysis

3.3. Chemical Elemental Composition Analysis

3.4. Spectroscopic Identification of Chromophores

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Saleh, M.; Bonizzoni, L.; Orsilli, J.; Samela, S.; Gargano, M.; Gallo, S.; Galli, A. Application of statistical analyses for lapis lazuli stone provenance determination by XRL and XRF. Microchem J. 2020, 154, 104655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re, A.; Giudice, A.L.; Angelici, D.; Calusi, S.; Giuntini, L.; Massi, M.; Pratesi, G. Lapis lazuli provenance study by means of micro-PIXE. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. At. 2011, 269, 2373–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Giudice, A.; Re, A.; Calusi, S.; Giuntini, L.; Massi, M.; Olivero, P.; Pratesi, G.; Albonico, M.; Conz, E. Multitechnique characterization of lapis lazuli for provenance study. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2009, 395, 2211–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelici, D.; Borghi, A.; Chiarelli, F.; Cossio, R.; Gariani, G.; Lo, G.A.; Re, A.; Pratesi, G.; Vaggelli, G. μ-XRF Analysis of Trace Elements in Lapis Lazuli-Forming Minerals for a Provenance Study. Microsc. Microanal. 2015, 21, 526–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukanov, N.V.; Sapozhnikov, A.N.; Shendrik, R.Y.; Vigasina, M.F.; Steudel, R. Spectroscopic and Crystal-Chemical Features of Sodalite-Group Minerals from Gem Lazurite Deposits. Minerals 2020, 10, 1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolotina, N.B.; Sapozhnikov, A.N.; Chukanov, N.V.; Vigasina, M.F. Structure Modulations and Symmetry of Lazurite-Related Sodalite-Group Minerals. Crystals 2023, 13, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukanov, N.V.; Vigasina, M.F.; Zubkova, N.V.; Pekov, I.V.; Schäfer, C.; Kasatkin, A.V.; Yapaskurt, V.O.; Pushcharovsky, D.Y. Extra-Framework Content in Sodalite-Group Minerals: Complexity and New Aspects of Its Study Using Infrared and Raman Spectroscopy. Minerals 2020, 10, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapozhnikov, A.N.; Tauson, V.L.; Lipko, S.V.; Shendrik, R.Y.; Levitskii, V.I.; Suvorova, L.F.; Chukanov, N.V.; Vigasina, M.F. On the crystal chemistry of sulfur-rich lazurite, ideally Na7Ca(Al6Si6O24)(SO4)(S3)–·nH2O. Am. Miner. 2021, 106, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapozhnikov, A.N.; Bolotina, N.B.; Chukanov, N.V.; Shendrik, R.Y.; Kaneva, E.V.; Vigasina, M.F.; Ivanova, L.A.; Tauson, V.L.; Lipko, S.V. Slyudyankaite, Na28Ca4(Si24Al24O96)(SO4)6(S6)1/3(CO2)·2H2O, a new sodalite-group mineral from the Malo-Bystrinskoe lazurite deposit, Baikal Lake area, Russia. Am. Miner. 2023, 108, 1805–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukanov, N.V.; Aksenov, S.M.; Rastsvetaeva, R.K. Structural chemistry, IR spectroscopy, properties, and genesis of natural and synthetic microporous cancrinite- and sodalite-related materials: A review. Microporous Mesoporous Mat. 2021, 323, 111098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapozhnikov, A.N.; Kaneva, E.V.; Cherepanov, D.I.; Suvorova, L.F.; Levitsky, V.I.; Ivanova, L.A.; Reznitsky, L.Z. Vladimirivanovite, Na6Ca2[Al6Si6O24](SO4,S3,S2,Cl)2·H2O, a new mineral of sodalite group. Geol. Ore Depos. 2012, 54, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedyaeva, M.; Lepeshkin, S.; Chukanov, N.V.; Oganov, A.R. Mutual Transformations of Polysulfide Chromophore Species in Sodalite-Group Minerals: A DFT Study on S6 Decomposition. ChemPhysChem 2024, 25, e202400532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caggiani, M.C.; Mangone, A.; Acquafredda, P. Blue coloured haüyne from Mt. Vulture (Italy) volcanic rocks: SEM-EDS and Raman investigation of natural and heated crystals. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2022, 53, 956–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapozhnikov, A.N.; Chukanov, N.V.; Shendrik, R.Y.; Vigasina, M.F.; Tauson, V.L.; Lipko, S.V.; Belakovskiy, D.I.; Levitskii, V.I.; Ivanova, L.F.S.L. Lazurite: Validation as a Mineral Species with the Formula Na7Ca(Al6Si6O24)(SO4)(S3-)⋅H2O and New Data. Geol. Ore Depos. 2022, 64, 470–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chivers, T.; Elder, P.J.W. Ubiquitous trisulfur radical anion: Fundamentals and applications in materials science, electrochemistry, analytical chemistry and geochemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 5996–6005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steudel, R.; Chivers, T. The role of polysulfide dianions and radical anions in the chemical, physical and biological sciences, including sulfur-based batteries. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 3279–3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platonov, A.N.; Tarashchan, A.N.; Belichenko, V.P.; Povarennikh, A.S. Spectroscopic study of sulfide sulfur in some framework aluminosilicates. Const. Prop. Miner. 1971, 5, 61–72. [Google Scholar]

- Rejmak, P. Computational refinement of the puzzling red tetrasulfur chromophore in ultramarine pigments. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. PCCP 2020, 22, 22684–22698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romano, R.M.; Pellizzari, J.; Ruvituso, F.L.; Pietrodangelo, G.; Picone, A.L.; Rossi, N.G.; Della Védova, C.O. Tintoretto in the city of La Plata? Several investigations for the reattribution of the Portrait of Melchior Michael to Tintoretto. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1321, 140163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favaro, M.; Guastoni, A.; Marini, F.; Bianchin, S.; Gambirasi, A. Characterization of lapis lazuli and corresponding purified pigments for a provenance study of ultramarine pigments used in works of art. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2012, 402, 2195–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Guo, Y. Genesis and influencing factors of the colour of chrysoprase. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 9939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Tang, J. Spectroscopy and chromaticity characterization of yellow to light-blue iron-containing beryl. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 10765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Mo, T.; Cheng, S. Contribution of lightness difference to color difference of jadeite-jade based on color difference formula. Bull. Chin. Ceram. Soc. 2010, 29, 496–501. [Google Scholar]

- Chukanov, N.V.; Shendrik, R.Y.; Vigasina, M.F.; Pekov, I.V.; Sapozhnikov, A.N.; Shcherbakov, V.D.; Varlamov, D.A. Crystal Chemistry, Isomorphism, and Thermal Conversions of Extra-Framework Components in Sodalite-Group Minerals. Minerals 2022, 12, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farsang, S.; Caracas, R.; Adachi, T.B.M.; Schnyder, C.; Zajacz, Z. S2−and S3− radicals and the S42− polysulfide ion in lazurite, haüyne, and synthetic ultramarine blue revealed by resonance Raman spectroscopy. Am. Miner. 2023, 108, 2234–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climent-Pascual, E.; de Paz, J.R.; Rodríguez-Carvajal, J.; Suard, E.; Sáez-Puche, R. Synthesis and Characterization of the Ultramarine-Type Analog Na8−x [Si6Al6O24]·(S2, S3, CO3)1−2. Inorg. Chem. 2009, 48, 6526–6533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauson, V.L.; Goettlicher, J.; Sapozhnikov, A.N.; Mangold, S.; Lustenberg, E.E. Sulphur speciation in lazurite-type minerals (Na,Ca)8[Al6Si6O24](SO4,S)2 and their annealing products: A comparative XPS and XAS study. Eur. J. Mineral. 2012, 24, 133–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, I.; Peterson, R.C.; Grundy, H.D. The Structure of Lazurite, Ideally Na6Ca2(Al6Si6O24)S2, a Member of the Sodalite Group. Acta Crystallographica. Sect. C 1985, C41, 827–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauson, V.L.; Sapozhnikov, A.N.; Shinkareva, S.N.; Lustenberg, E.E. Indicative properties of lazurite as a member of clathrasil mineral family. Dokl. Earth Sci. 2011, 441, 1732–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faryad, S.W. Metamorphic conditions and fluid compositions of scapolite-bearing rocks from the Lapis Lazuli Deposit at Sare Sang, Afghanistan. J. Petrol. 2002, 43, 725–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faryad, S.W. Metamorphic evolution of the Precambrian South Badakhshan Block, based on mineral reactions in metapelites and metabasites associated with whiteschists from Sare Sang (western Hindu Kush, Afghanistan). Precambrian Res. 1999, 98, 223–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleet, M.E.; Liu, X.; Harmer, S.L. Chemical state of sulfur in natural and synthetic lazurite by S K-edge XANES and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. Can. Mineral. 2007, 43, 1589–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostroumov, M.; Fritsch, E.; Faulques, E.; Chauvet, O. Etude spectrometrique de la lazurite du Pamir, Tajikistan. Can. Mineral. 2002, 40, 885–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mingsheng, P.; Rubo, Z.; Zheng, C.; He, S. A Study on Spectroscopy of Lazurite and Its Significance. J. Cent. South Univ. (Sci. Technol.) 1983, 2, 90–97. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Z.J.; Zheng, Q.R.; Cao, S.Q.; Wang, F. Gemmological and Mineralogical Characteristics of Lapis Lazuli. J. Gems Gemmol. 2023, 25, 54–59. [Google Scholar]

- Steudel, R.; Steudel, Y. Polysulfide Chemistry in Sodium–Sulfur Batteries and Related Systems— A Computational Study by G3X(MP2) and PCM Calculations. Chem.—A Eur. J. 2013, 19, 3162–3176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Control Variable | Color Parameters | L* | h° | |

| C* | L* | Correlation r | 1 | −0.840 |

| Significance p | - | <0.01 | ||

| SE | - | 0.062 | ||

| h° | Correlation r | −0.840 | 1 | |

| Significance p | <0.01 | - | ||

| SE | 0.062 | - | ||

| Control Variable | Color Parameters | L* | C* | |

| h° | L* | Correlation r | 1 | 0.811 |

| Significance p | - | <0.01 | ||

| SE | - | 0.043 | ||

| C* | Correlation r | 0.811 | 1 | |

| Significance p | <0.01 | - | ||

| SE | 0.043 | - |

| Classification | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Cluster Center | L* = 35.93 a* = 7.32 b* = −33.94 | L* = 32.78 a* = 20.88 b* = −44.36 | L* = 28.73 a* = 14.29 b* = −31.25 | L* = 26.78 a* = 3.53 b* = −10.13 |

|  |  |  | |

| Color Grade | Fancy Blue | Fancy Intense Blue | Fancy Deep Blue | Fancy Dark Blue |

| ΔE00 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 1 | - | 7.64 | 7.33 | 13.98 |

| 2 | 7.64 | - | 6.01 | 17.15 |

| 3 | 7.33 | 6.01 | - | 12.24 |

| 4 | 13.98 | 17.15 | 12.24 | - |

| Sample | Color Block | Photo-Electron Peak | Binding Energy (eV) | FWHM (eV) a | MPE b | MF c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ys-1 | L* = 26.77 a* = 13.02 b* = −29.54  | S 2p3/2 | 168.37 | 1.63 | 0.45 | |

| S 2p1/2 | 169.52 | 1.63 | ||||

| S 2p3/2 | 163.45 | 1.75 | [S3]·− | 0.37 | ||

| S 2p1/2 | 164.60 | 1.74 | ||||

| S 2p3/2 | 161.49 | 1.24 | S2− | 0.18 | ||

| S 2p1/2 | 162.64 | 1.24 | ||||

| YS-2 | L* = 32.92 a* = 22.01 b* = −40.32  | S 2p3/2 | 168.37 | 1.61 | 0.43 | |

| S 2p1/2 | 169.52 | 1.61 | ||||

| S 2p3/2 | 163.20 | 1.50 | [S3]·− | 0.32 | ||

| S 2p1/2 | 164.35 | 1.50 | ||||

| S 2p3/2 | 161.67 | 1.39 | S2− | 0.25 | ||

| S 2p1/2 | 162.82 | 1.39 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ma, X.; Huang, X.; Guo, Y.; Jia, Z.; Jia, S. Colorimetry Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Sulfur-Rich Lapis Lazuli. Crystals 2025, 15, 1035. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121035

Ma X, Huang X, Guo Y, Jia Z, Jia S. Colorimetry Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Sulfur-Rich Lapis Lazuli. Crystals. 2025; 15(12):1035. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121035

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Xiaorui, Xu Huang, Ying Guo, Zhili Jia, and Shuo Jia. 2025. "Colorimetry Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Sulfur-Rich Lapis Lazuli" Crystals 15, no. 12: 1035. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121035

APA StyleMa, X., Huang, X., Guo, Y., Jia, Z., & Jia, S. (2025). Colorimetry Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Sulfur-Rich Lapis Lazuli. Crystals, 15(12), 1035. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121035