Influence of Scanning Speed on the Electrochemical and Discharge Behavior of a CeO2/Al6061 Anode for an Al–Air Battery Manufactured via Selective Laser Melting

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material and Sample Preparation

2.2. XRD Test

2.3. Porosity and Relative Density Measurement

2.4. Self-Corrosion Rate

2.5. Electrochemical Test

2.6. Discharge Performance

3. Results and Discussion

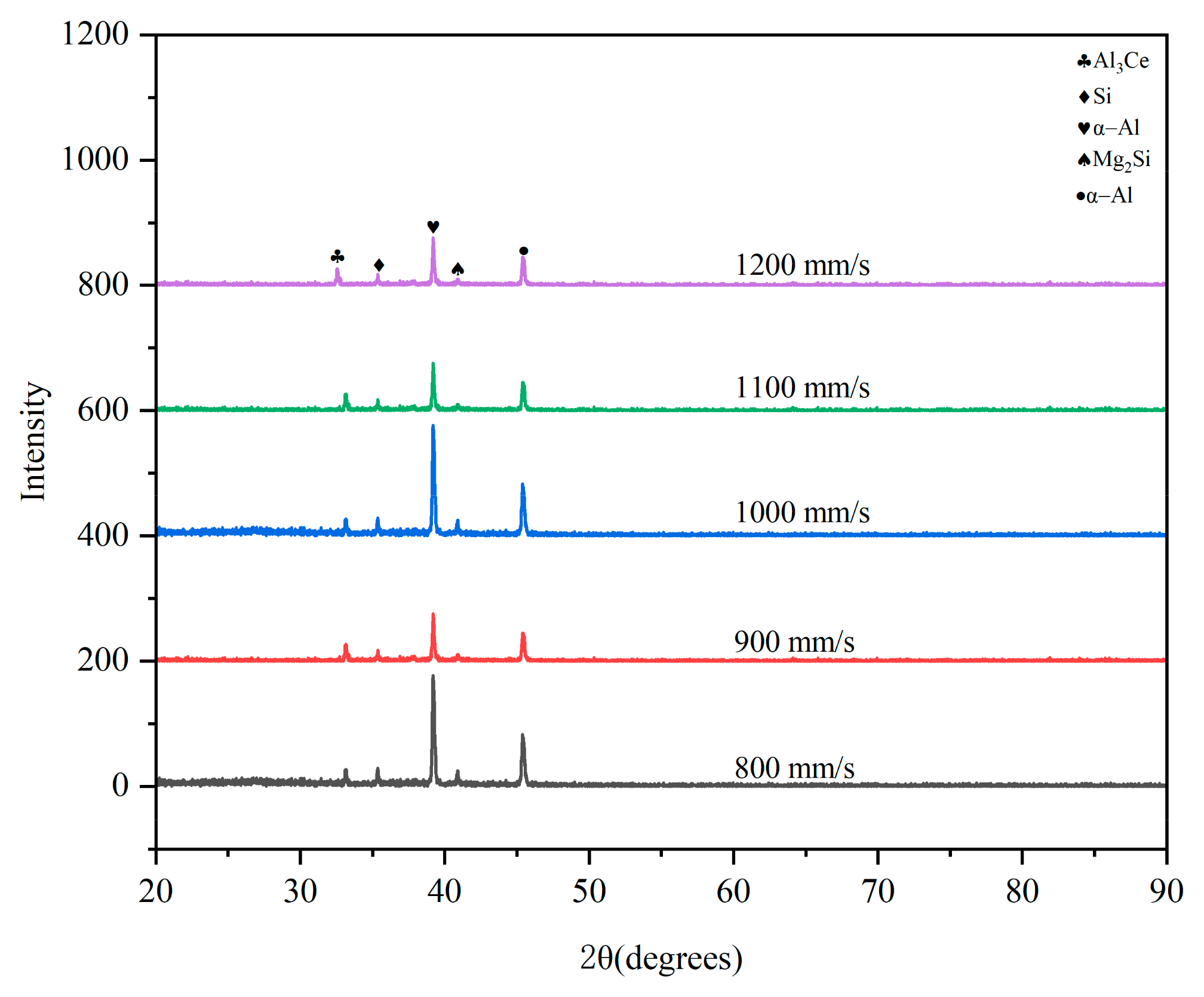

3.1. XRD Characterization

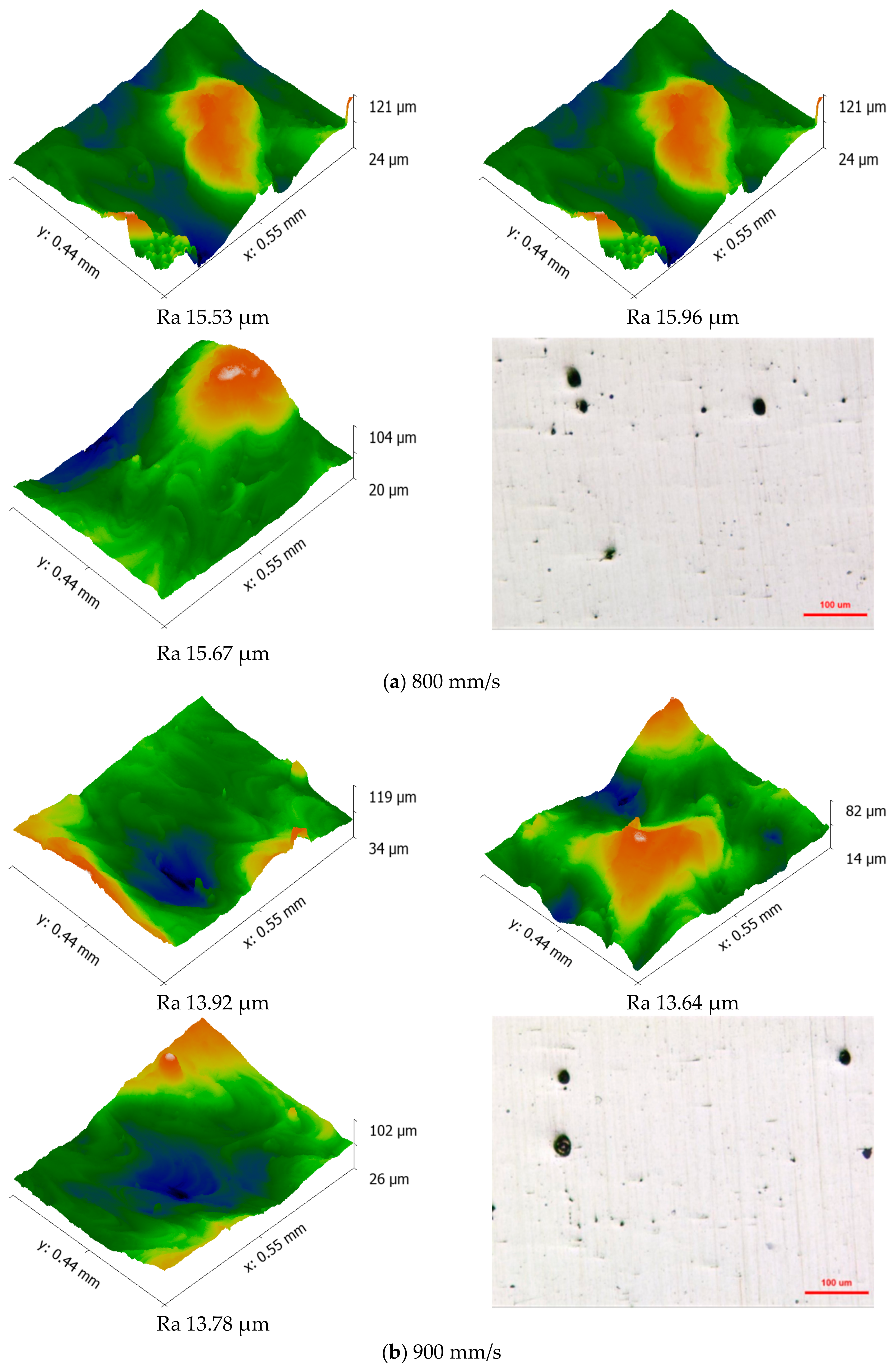

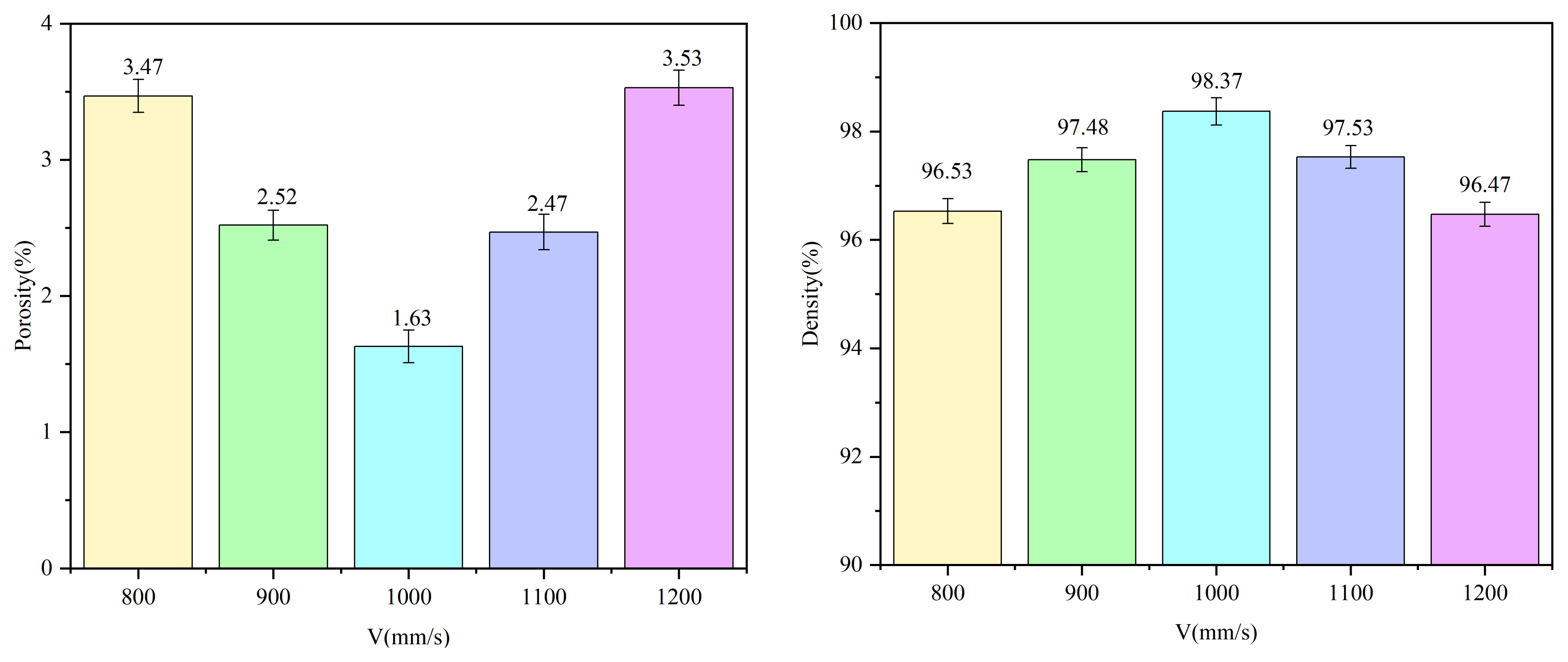

3.2. Porosity and Relative Density

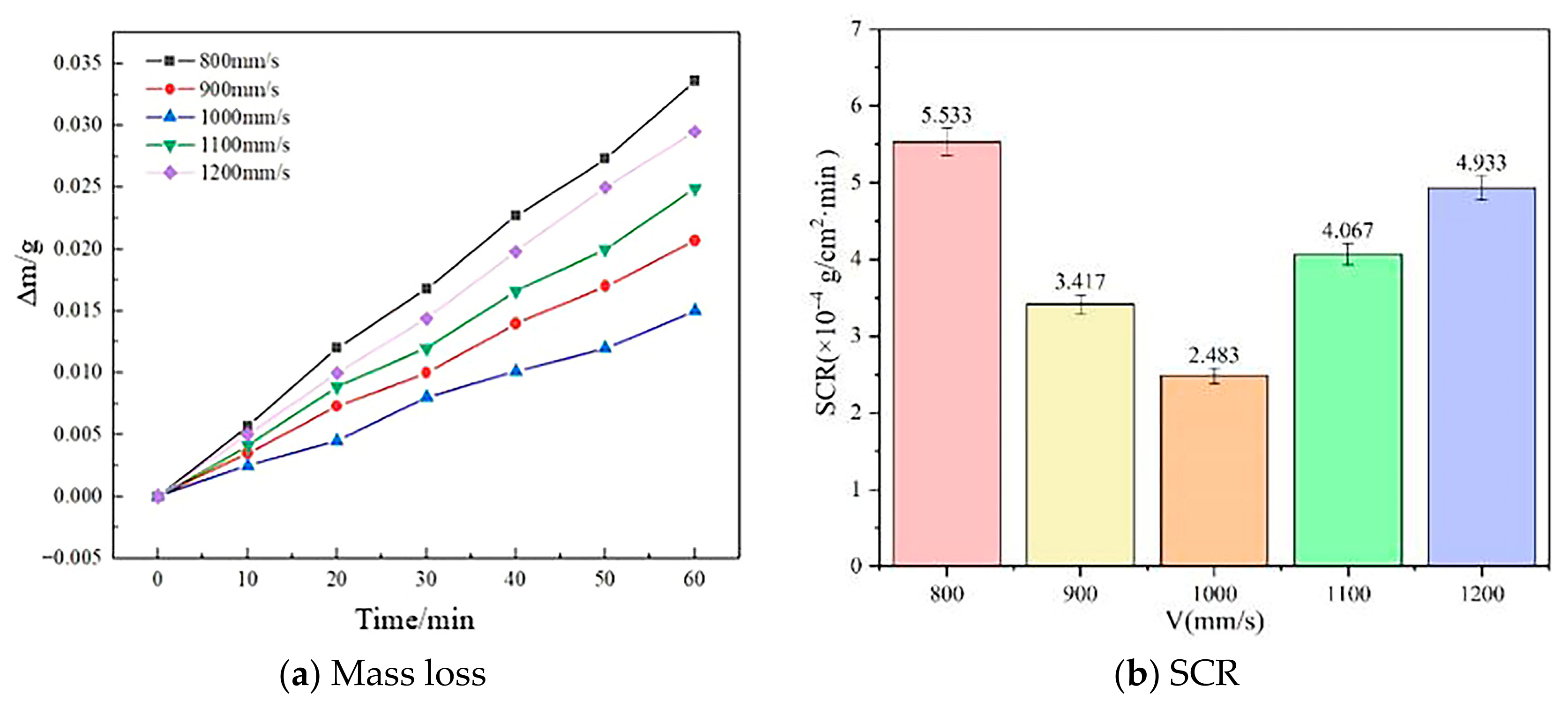

3.3. Self-Corrosion Test

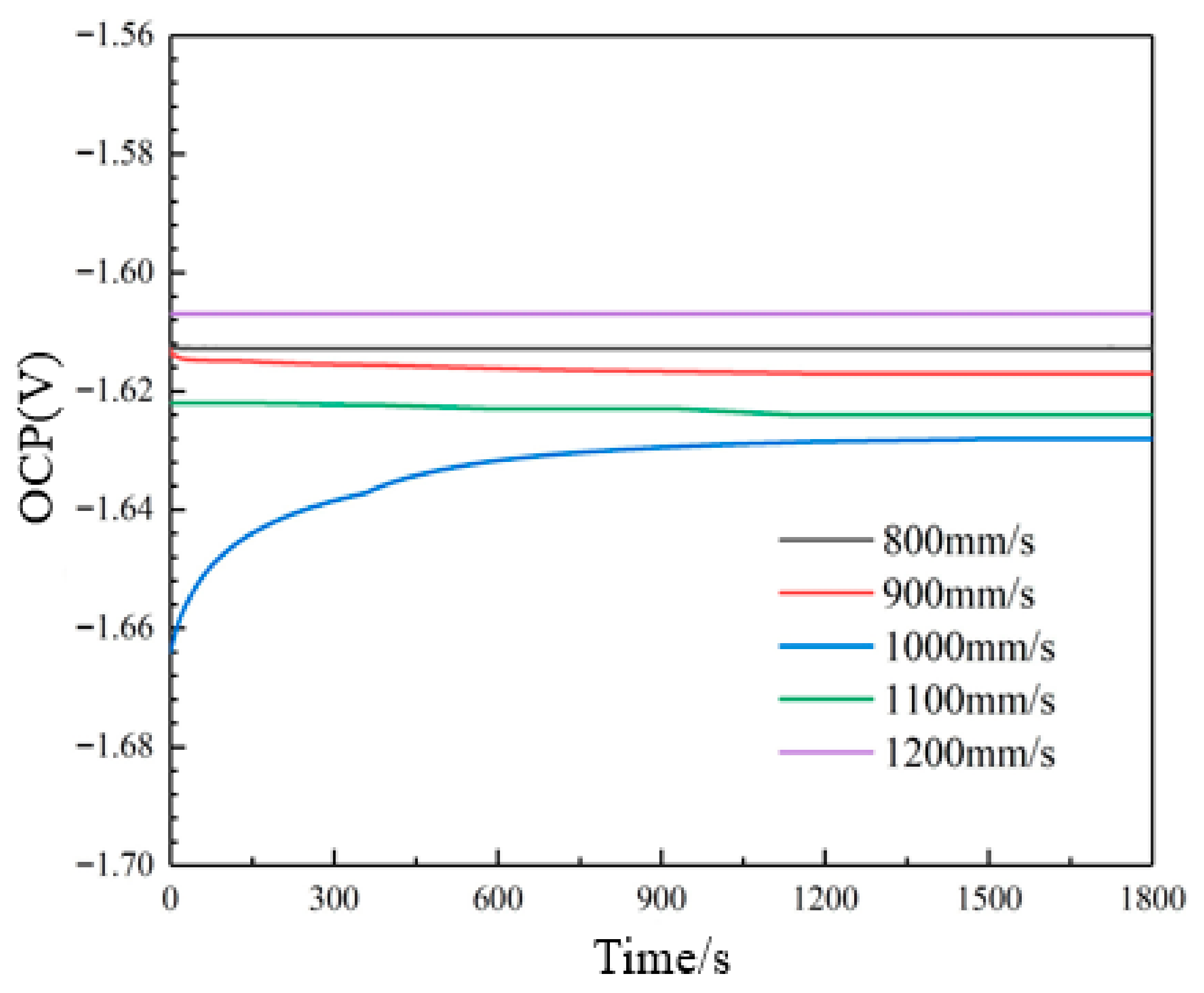

3.4. Electrochemical Performance

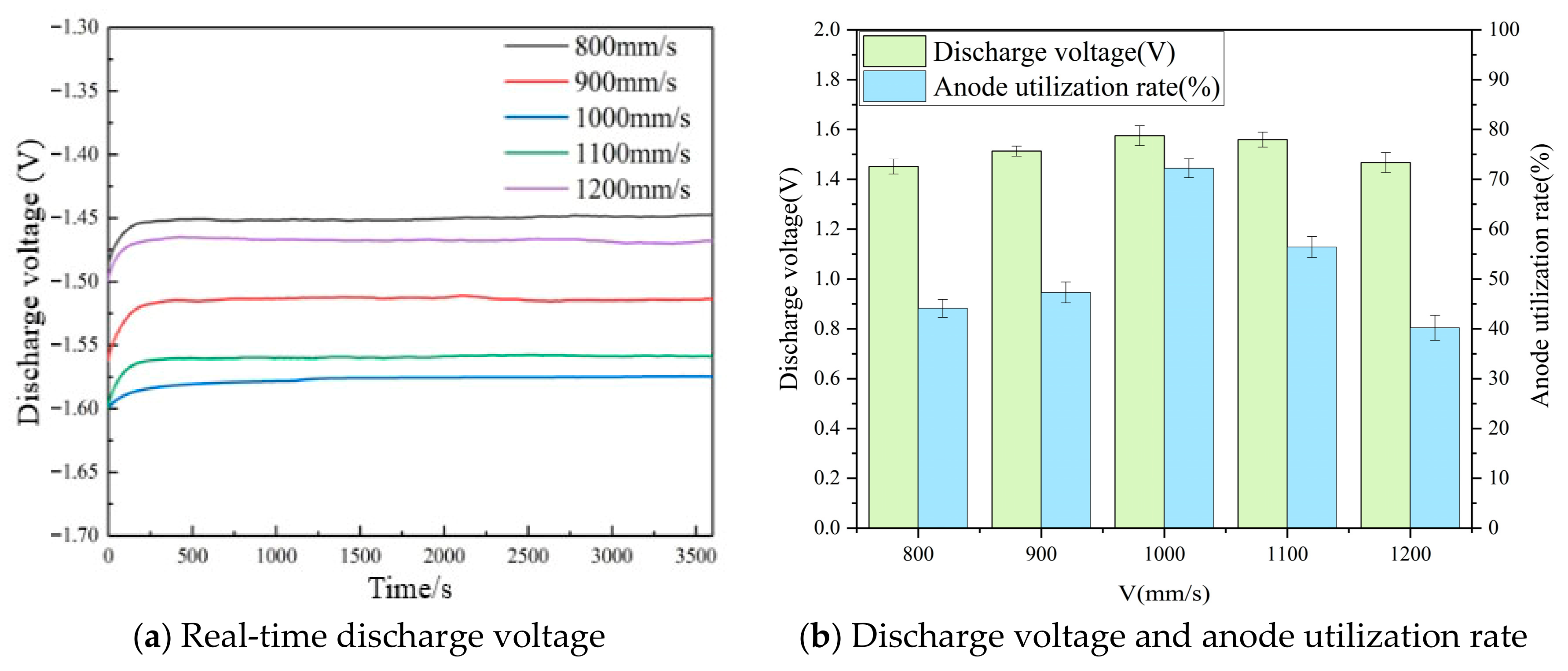

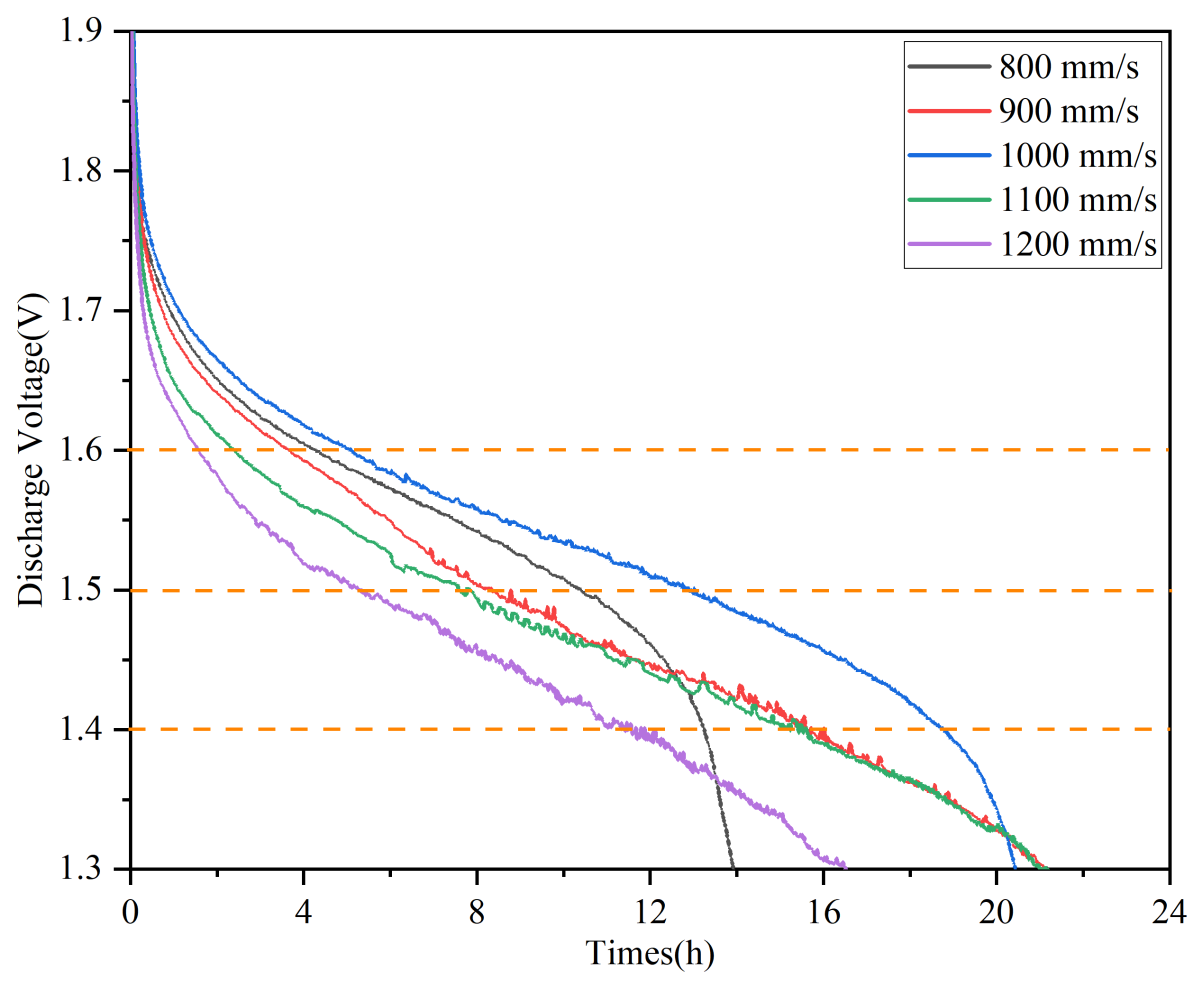

3.5. Discharge Behavior

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- The scanning speed significantly influences the surface morphology and density of the anodes. At a scanning speed of 1000 mm/s, the anodes exhibit the highest density (98.37%) and relatively smooth surface morphology, with minimal pore defects.

- (2)

- The SCR of the anodes is lowest at the scanning speed of 1000 mm/s (2.483 × 10−4 g/cm2·min), indicating improved corrosion resistance due to the complete melting of the powder and uniform microstructure formation.

- (3)

- Electrochemical testing reveals that the anodes fabricated at 1000 mm/s scanning speed exhibit the most negative corrosion potential of −1.632 V and the smallest corrosion current density of 6.861 × 10−3 A/cm2, indicating superior electrochemical activity and reduced self-corrosion reactions.

- (4)

- The discharge performance of the anodes is optimized at a scanning speed of 1000 mm/s, achieving a high discharge voltage of 1.575 V and an anode utilization rate of 72.2%. This is attributed to the moderate laser energy, which ensures full melting of the powder, resulting in better forming quality of the alloy anode.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- El-Alouani, M.; Kharbouch, O.; Dahmani, K.; Errahmany, N.; Saber, I.; Galai, M.; Benzekri, Z.; Boukhris, S.; Touhami, M.E.; Al-Sadoon, M.K.; et al. Enhancing Al–Air Battery Performance with Beta-d-Glucose and Adonite Additives: A Combined Electrochemical and Theoretical Study. Langmuir 2025, 41, 431–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Lai, G.; Gu, J.; Liu, Z.; Wang, J. High specific capacity microfluidic Al-air battery with the double-side reactive anode. J. Power Sources 2024, 5, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; Wang, K.; Pei, P.; Zhong, L.; Züttel, A.; Pham, T.H.M.; Shang, N.; Zuo, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhao, S. Zinc carboxylate optimization strategy for extending Al-air battery system’s lifetime. Appl. Energy 2023, 350, 121804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, W.; Guo, F.; Yin, Y.; Zheng, X.; Wu, J.; Qiang, Y.; Wang, W. A green electrolyte additive based on Toona Sinensis extract for enhanced performance of alkaline Al-air battery. Corros. Sci. 2025, 252, 112952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dovidio, L.; Harakas, G.N. A New Design of the Air-Aluminum Battery, Optimized for STEM Activities. J. Chem. Educ. 2024, 101, 1747–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; Wang, K.; Zuo, Y.; Zhong, L.; Züttel, A.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, P.; Wang, H.; Zhao, S.; Pei, P. A Prussian-Blue Bifunctional Interface Membrane for Enhanced Flexible Al–Air Batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Zhang, Q.; Huang, Y.; Sun, R.; Zhang, R.; Saji, V.S.; Chang, J.; Zheng, X.; Adam, A.M.M. Regulating the Helmholtz plane by trace ionic liquid additive for advanced Al-air battery. J. Power Sources 2025, 625, 235672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, L.; Fu, L.; Su, L.; Shen, H.; Zhang, Z. Method to characterize thermal performances of an aluminum-air battery. Energy 2024, 301, 131757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Xu, S.; Wu, J.; Yin, Y.; Cheng, S.; Zhang, C.; Qiang, Y.; Wang, W. Probing corrosion protective mechanism of an amide derivative additive on anode for enhanced alkaline Al-air battery performance. J. Power Sources 2024, 593, 233957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagh, N.K.; Shinde, S.S.; Lee, J.H. Atomically modulated Cu single-atom catalysts for oxygen reduction reactions towards high-power density Zn- and Al-air batteries. Chem. Commun. 2024, 60, 15015–15018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Yan, H.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, W.; Yin, S.; Du, W.; Wang, Z. Regulation of self-corrosion behaviors of Al in Al-air gel electrolyte batteries. J. Mater. Sci. 2025, 60, 6354–6368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikang, W.; Zhaohui, H.; Yang, X.; Xu, L. Microwave-assisted smelting to improve the corrosion and discharge performance of Al-anodes in Al-air batteries. J. Mater. Sci. 2023, 58, 12433–12449. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, G.-X.; Wei, Z.-S.; Li, S.-Q.; Cui, L.-Y.; Zhang, G.-X.; Zeng, R.-C. Corrosion inhibition of polyelectrolytes to the Al anode in Al-air battery: A comparative study of functional group effect. J. Power Sources 2024, 592, 233907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, K.K.; Maurya, P.K.; Mishra, A.K. Dual electrolyte based aluminium air battery using NiCo2O4–MoSe2 hybrid nanocomposite. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 69, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wei, X.; Feng, J.; Xin, Y.; Wang, X.; Wei, Y. High energy efficiency and high discharge voltage of 2N-purity Al-based anodes for Al-air battery by simultaneous addition of Mn, Zn and Ga. J. Power Sources 2023, 563, 232845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Shi, W.; Guo, L.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, K.; Zheng, X.; Verma, C.; Qiang, Y. Corrosion inhibition of L-tryptophan on Al-5052 anode for Al-air battery with alkaline electrolyte. J. Power Sources 2023, 564, 232866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li-Lai, L.U.; Qing-Shan, L.I.; Sun, Y.N.; Kuang, K.-B.; Li, Z.; Wang, T.; Gao, Y.; Wang, J.-B. Research progress on biomass carbon as the cathode of a metal-air battery. Carbon 2024, 218, 118675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Guo, L.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Ritacca, A.G.; Leng, S.; Zheng, X.; Yang, Y.; Singh, A. Influence of an imidazole-based ionic liquid as electrolyte additive on the performance of alkaline Al-air battery. J. Power Sources 2023, 564, 232901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Xiong, L.; Wang, S.; Xie, Y.; You, W.; Du, X. A review of the Al-gas batteries and perspectives for a “Real” Al-air battery. J. Power Sources 2023, 580, 233375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Yan, L.; Han, Y.; Luo, L.; Guo, J.; Xiang, B.; Zhou, Y.; Zou, X.; Guo, L.; Bai, Y. Synergistic modulation of alkaline aluminum-air battery based on localized water-in-salt electrolyte towards anodic self-corrosion. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 485, 149600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Gao, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhang, J.F.; Wu, Z.; Hu, W. Tailoring Non-Polar Groups of Quaternary Ammonium Salts for Inhibiting Hydrogen Evolution Reaction of Aluminum-Air Battery. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 15747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y.; Liu, Y.; Gao, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhang, J.; Qin, Z.; Tang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wu, Z.; et al. Effect of oxidant additive on enhancing activation property of NaCl-based electrolyte aluminum-air battery. J. Power Sources 2024, 606, 234558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Miao, D.; Liu, Y.; Qu, J.; Yan, W. Constructing composite protective interphase in situ for high-performance aluminum-air batteries. J. Power Sources 2025, 640, 236750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.C.; Saw, L.H.; Yew, M.C.; Sun, D.; Chen, W.-H. High performance aluminum-air battery for sustainable power generation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 11, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Chen, C.; Li, X.; Yu, H.; Peng, K.; Tian, Z. Boosting the Performance of Aluminum-Air Batteries by Interface Modification. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Li, K.; Li, C.; Miao, X.; Araki, T.; Wu, M. Corrosion behavior of selective laser melted 6061 aluminum alloy electrodes for aluminum-air battery. J. Power Sources 2024, 594, 233999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Hu, Z.; Yin, C.; Qin, S.; Li, P.; Guan, J.; Zhu, K.; Li, Y.; Tang, S.; Han, J. Influence of Laser Process Parameters on the Forming Quality and Discharge Performance of 3D-Printed Porous Anodes for Al–Air Batteries. Materials 2024, 17, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Zhu, K.; Duan, W. A comprehensive study on the overall performance of aluminum-air battery caused by anode structure. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2023, 309, 128334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Q.; Li, Y.; Sun, N.; Song, Z.; Zhu, K.; Guan, J.; Li, P.; Tang, S.; Han, J. A Multi-Objective Genetic Algorithm-Based Predictive Model and Parameter Optimization for Forming Quality of SLM Aluminum Anodes. Crystals 2024, 14, 4070608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, G.; Geng, Y.; Niu, C.; Yang, H.; Duan, W.; Cao, S. Corrosion Inhibition of PAAS/ZnO Complex Additive in Alkaline Al-Air Battery with SLM-Manufactured Anode. Crystals 2024, 14, 4111002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Duan, W. The Effect of Hatch Spacing on the Electrochemistry and Discharge Performance of a CeO2/Al6061 Anode for an Al-Air Battery via Selective Laser Melting. Crystals 2024, 14, 4090797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, G.; Niu, C.; Geng, Y.; Duan, W.; Cao, S. Multi-Objective Optimization for the Forming Quality of a CeO2/Al6061 Alloy as an Aluminum–Air Battery Anode Manufactured via Selective Laser Melting. Crystals 2024, 14, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Nagaumi, H. Effect of Microstructure Evolution on the Discharge Characteristics of Al-Mg-Sn-based Anodes for Al-air. J. Power Sources 2022, 521, 230928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; Wang, K.L.; Kang, L. Zn-dominated Interphase Inhibits the Anodic Parasitic Reactions for Al-air Batteries Using Zn2+@Agar Hydrogel Membrane. J. Power Sources 2022, 545, 231974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scanning Speed (mm/s) | Laser Power (W) | Scan Spacing (mm) | Powder Thickness (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 800, 900, 1000, 1100, 1200 | 300 | 0.13 | 0.03 |

| Scanning Speed | Electrochemical Parameters | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| E (v) | Icorr (A/cm2) | Rp (Ω∙cm2) | |

| 800 mm/s | −1.617 | 2.731 × 10−2 | 1.6 |

| 900 mm/s | −1.624 | 9.406 × 10−3 | 4.7 |

| 1000 mm/s | −1.632 | 6.861 × 10−3 | 6.4 |

| 1100 mm/s | −1.627 | 2.200 × 10−2 | 2.1 |

| 1200 mm/s | −1.615 | 2.224 × 10−2 | 2.0 |

| Scanning Speed | 800 mm/s | 900 mm/s | 1000 mm/s | 1100 mm/s | 1200 mm/s |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L/Ω·cm2 | 9.990 × 10−7 | 8.350 × 10−7 | 6.869 × 10−7 | 8.961 × 10−7 | 7.030 × 10−7 |

| Rs/Ω·cm2 | 1.426 × 10−1 | 1.150 × 10−1 | 1.260 × 10−1 | 1.093 × 10−1 | 1.232 × 10−1 |

| CPE1/F·cm−2 | 9.612 × 10−4 | 4.269 × 10−4 | 3.018 × 10−3 | 4.778 × 10−3 | 5.164 × 10−5 |

| R1/Ω·cm2 | 3.364 × 10−1 | 4.631 × 10−1 | 8.171 × 10−1 | 5.569 × 10−1 | 3.991 × 10−1 |

| CPE2/F·cm−2 | 1.515 × 10−1 | 7.172 × 10−1 | 3.940 × 10−2 | 2.518 × 10−1 | 1.654 × 10−1 |

| R2/Ω·cm2 | 1.215 × 10−1 | 1.242 × 10−1 | 2.064 × 10−1 | 1.140 × 10−1 | 1.662 × 10−1 |

| ꭓ2 | 2.974 × 10−4 | 8.862 × 10−4 | 2.464 × 10−4 | 3.846 × 10−4 | 8.945 × 10−4 |

| No. | Anode | Discharge Voltage (V) | Anode Utilization Rate (%) | Process | Literature |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CeO2/Al6061 | 1.57 | 72.2 | SLM | This work |

| 2 | TiB2/Al6061 | / | 62.2 | SLM | 30 |

| 3 | Al6061 | 1.56 | / | SLM | 28 |

| 4 | Al6061 | 1.54 | 70.3 | SLM | 27 |

| 5 | Al6061 | 1.76 | / | Cast + Heat treatment | 34 |

| 6 | Al-Mg-Sn | 1.78 | / | Cast + Corrosion inhibitors | 35 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Diao, S.; Zhou, G.; Cao, X.; Duan, W. Influence of Scanning Speed on the Electrochemical and Discharge Behavior of a CeO2/Al6061 Anode for an Al–Air Battery Manufactured via Selective Laser Melting. Crystals 2025, 15, 947. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15110947

Diao S, Zhou G, Cao X, Duan W. Influence of Scanning Speed on the Electrochemical and Discharge Behavior of a CeO2/Al6061 Anode for an Al–Air Battery Manufactured via Selective Laser Melting. Crystals. 2025; 15(11):947. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15110947

Chicago/Turabian StyleDiao, Shu, Guanghong Zhou, Xiaobing Cao, and Weipeng Duan. 2025. "Influence of Scanning Speed on the Electrochemical and Discharge Behavior of a CeO2/Al6061 Anode for an Al–Air Battery Manufactured via Selective Laser Melting" Crystals 15, no. 11: 947. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15110947

APA StyleDiao, S., Zhou, G., Cao, X., & Duan, W. (2025). Influence of Scanning Speed on the Electrochemical and Discharge Behavior of a CeO2/Al6061 Anode for an Al–Air Battery Manufactured via Selective Laser Melting. Crystals, 15(11), 947. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15110947