1. Introduction

Alkanes represent model systems for studying phase transitions in molecular crystals due to their relative structural simplicity and well-established thermodynamic properties [

1,

2,

3]. Short-chain alkanes, such as n-hexane (C

6H

14) and decane (C

10H

22), are of particular interest for investigating glass formation, as their chain lengths lie near the critical threshold that determines the propensity for vitrification or crystallization [

4,

5].

The vitrification of alkanes requires the suppression of crystallization at extremely high cooling rates. Angell [

6] and Mosquera-Vargas et al. [

7] demonstrated that short alkanes have the potential to form glasses, albeit under specific preparation conditions. Recent time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry (TOF-SIMS) studies by Souda [

8] on vapor-deposited n-hexane revealed a multistage nature of the glass transition, involving the sequential formation of an ultraviscous liquid at 110 K and a fluidized liquid at 130 K.

Studying the glass-forming ability of short-chain alkanes like n-hexane and decane is of significant interest from both fundamental and applied perspectives. Fundamentally, alkanes serve as model systems for exploring the kinetics of liquid-to-crystal and liquid-to-glass transitions [

9]. Determining critical parameters, such as the requisite cooling rate and film thickness for suppressing crystallization, addresses a key challenge in condensed matter physics [

10,

11]. Despite predictions from Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations, systematic experimental studies establishing these threshold values remain scarce [

12,

13]. From an applied standpoint, controlling the phase state of alkanes is relevant in materials science (e.g., for creating hydrocarbon-based films with tailored morphology) [

14,

15], cryogenics and fuel technology (e.g., for preventing unwanted crystallization of components) [

16], and even astrophysics (modeling hydrocarbon behavior in low-temperature cosmic environments) [

17]. Thus, this work aims to develop clear experimental criteria for the vitrification of alkanes, bridging the gap between theoretical predictions and practical feasibility.

An important aspect is understanding the influence of cooling rate on the formation of different phases. Molecular dynamics calculations indicate that extremely high cooling rates are required to suppress the crystallization of alkanes [

12,

13]. Recent coarse-grained MD simulations have revealed continuous premelting dynamics in long-chain alkanes and a transition from discrete phase transitions to a gradual premelting process [

18]. Studies on the aggregation behavior of paraffin molecules with different branching distributions have shown that isoalkanes with closely spaced branches form the weakest gel-like structures [

19]. These predictions find experimental support in high-pressure research: Snyder et al. [

20] demonstrated that even at pressures up to 9.3 GPa, C

6-C

11 alkanes supercool to 147 K but ultimately crystallize. The complexity of alkyl chain relaxation is further corroborated by rheological studies of ionic liquids [

21], which highlight the significant contribution of alkyl groups to viscosity and the glass transition temperature. Furthermore, sample thickness plays a critical role—in thin films, relaxation processes occur faster due to the reduced cooperativity of molecular motions [

22].

Raman spectroscopy is an effective method for investigating structural changes in alkanes, as it enables the analysis of conformational transitions, intermolecular interactions, and the degree of molecular ordering [

23,

24]. Characteristic bands include C-H stretching vibrations (2850–3000 cm

−1), CH

2 deformation vibrations (1300–1500 cm

−1), and C-C stretching vibrations (800–1200 cm

−1) [

25,

26].

The phase diagrams of alkanes exhibit complex behavior with the formation of various crystalline polymorphs [

1,

2]. Short alkanes typically undergo direct liquid-crystal transitions, whereas long alkanes can form intermediate rotator phases [

1,

2]. The kinetics of alkane crystallization has been extensively studied, revealing the critical role of cooling rate and size effects [

9,

12].

Investigations into alkane polymorphism have identified several crystalline modifications, whose stability depends on the preparation conditions. The influence of the substrate on crystallization processes is also a significant factor, particularly in studies of thin films [

22].

Spectroscopic studies of alkanes at low temperatures have shown characteristic changes in vibrational spectra associated with conformational transitions and variations in intermolecular interactions. The temperature dependence of spectral parameters allows for the identification of different phase states.

Objectives are to experimentally investigate the influence of cooling rate on the structure formation of n-hexane and decane using a contact freezing approach, analyzed by Raman spectroscopy; to establish spectroscopic criteria for distinguishing between defective and well-ordered crystalline structures, and to quantitatively assess the limitations of the contact freezing method for obtaining amorphous states of alkanes.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Materials and Equipment

The study used n-hexane (C6H14, purity ≥ 99%, Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA)) and decane (C10H22, purity ≥ 99%, Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA)) without further purification.

The experimental setup (

Figure 1) consisted of the following main components:

Miniature Raman Spectrometer ATR2500 (B&W Tek (Metrohm), Newark, DE, USA): A portable spectrometer with a 785 nm laser excitation source, providing a spectral resolution of ~8 cm−1 in the range of 200–3200 cm−1. The spectrometer was positioned above the sample in a 180° backscattering geometry.

Cryogenic Sample Cell: A custom-made cell (d = 6 mm, h = 7 mm, V = 198 mm3) featuring a copper substrate for mounting the frozen alkane samples. The cell was equipped with an optical window for laser transmission and scattered light collection.

Temperature Sensor: A Pt102 platinum thermistor (nominal resistance 1000 Ω at 0 °C), housed within the copper body of the cell. Measurement accuracy: ±0.3 K in the 77–300 K range. The sensor was placed in immediate proximity to the sample for high-precision temperature monitoring.

Heating Element: A thermoelectric module enabling controlled temperature variation in the sample from 77 K to room temperature.

LakeShore 325 Temperature Controller (Lake Shore Cryotronics, Westerville, OH, USA): A precision temperature controller capable of programming temperature profiles, providing automatic stabilization, and maintaining temperature with an accuracy of ±0.1 K.

Operating Principle: The alkane sample was placed onto the copper substrate within the cryogenic cell (2), which was pre-cooled with liquid nitrogen to 77 K. The temperature sensor (3) continuously monitored the sample temperature, relaying data to the LakeShore 325 controller (5). The heating element (4) provided programmable heating of the sample at specified rates. The miniature ATR2500 Raman spectrometer (1) recorded Raman spectra through the cell’s optical window at various temperatures.

Technical Specifications: Laser power at the sample: ~50 mW. Spectrum acquisition time: 30 s. Temperature range: 77–340 K. Temperature ramp rates: 2.8–27 K/min (programmable). The system was stabilized for 3–5 min to achieve thermal equilibrium at each heating step.

2.2. Experimental Methodology

The experimental procedure consisted of the following stages:

Cryosystem Preparation: The copper substrate was mounted inside the cryogenic cell (2) and connected to the temperature control system via the temperature sensor (3) and heating element (4).

Sample Preparation via Two Distinct Protocols:

FAST COOLING (fastcooling): The copper substrate was cooled with liquid nitrogen to 77.2 K, and the temperature was stabilized. The liquid alkane sample was then deposited onto the pre-frozen substrate.

Result: The sample froze instantaneously upon contact with the cold surface.

CONVENTIONAL COOLING (usualcooling): The liquid alkane sample was deposited onto the substrate at room temperature. The entire system was then cooled with liquid nitrogen to 77.2 K.

Result: The sample cooled slowly and crystallized during the temperature decrease.

A sample volume of 198 ± 5 µL was used in the cell to ensure reproducible optical conditions for spectral acquisition. Raman analysis probed the surface layers of the sample (probing depth ~0.3–1 mm).

Controlled Heating: After reaching 77.2 K for both protocols, an identical programmable heating regimen was implemented using the LakeShore 325 controller (5):

77–200 K: ~27 K/min

200–250 K: ~12 K/min

250–340 K: ~2.8 K/min

Spectral Acquisition: At each temperature point (77, 80, 100, 115, 130, 150, 170, 200, 240, 270, 300, 340 K), the system was stabilized for 3–5 min. Subsequently, the ATR2500 spectrometer (1) recorded a Raman spectrum in a 180° backscattering geometry with a 30 s acquisition time and a laser power of ~50 mW.

2.3. Estimation of Cooling Rate

For the “fast cooling” protocol, the cooling rate was estimated experimentally based on the observed sample freezing time: initial sample temperature T_initial = 298 K, copper substrate temperature T_substrate = 77.2 K, observed freezing time: τ_freeze = 1–3 s (visually). The estimated cooling rate for the surface layers was: v_cool ≈ ΔT/τ ≈ (298–77)/2 ≈ 110 K/s. Considering the probing depth of the Raman analysis (~0.3–1 mm), where heat transfer is slower, the actual cooling rate in the analysis zone is estimated as v_cool ≈ 50–100 K/s. Monitoring of the substrate temperature with the Pt102 thermistor confirmed rapid attainment of thermal equilibrium (τ ~ 5–10 s), consistent with an estimated cooling rate on the order of 102 K/s. For the “conventional cooling” protocol, the rate was v_cool ≈ 1–5 K/s (controlled immersion of the system in liquid nitrogen).

2.4. Reproducibility and Data Processing

All experiments for each alkane and each cooling protocol were performed in triplicate. The presented spectra and temperature-dependent plots correspond to typical, representative results. For quantitative analysis of peak intensities and half-widths, a baseline correction procedure was performed using an adaptive iterative polynomial (4th order) subtraction algorithm in the OriginPro 2024 software package. Peaks were fitted with a Lorentzian function. On the plots of temperature-dependent intensities mean values from three measurements are presented, with the standard deviation (10%) displayed as the error. For clarity in the spectra (Figures 2–5), spectra at different temperatures are vertically offset for easier comparison, and key temperature points (e.g., 77 K, 150 K, 200 K) are explicitly indicated on the plots or in the legend.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Spectral Changes in n-Hexane

Analysis of the n-hexane spectra (

Figure 2) revealed significant differences between the fast and conventional cooling protocols. However, in all cases, crystallization was observed without the formation of an amorphous phase:

Fast Cooling of n-Hexane:

Skeletal Deformation Region (250–450 cm−1): A dominant peak is observed at ~380 cm−1 with a relatively broad profile. At temperatures below 120 K, the spectral bands exhibit broadening, which may be associated with relaxation processes within the already formed crystal lattice, but they retain the primary structure characteristic of a crystalline state with enhanced structural disorder.

C-C Stretching Vibration Region (800–1500 cm−1): Key bands were identified at 820, 898, 1011, 1065, 1142, 1302, and 1453 cm−1. The most intense band at 1453 cm−1 (CH2 scissoring mode) shows a maximum intensity of ~10,000 arbitrary units at low temperatures, indicating the formation of a defective crystalline structure that retains the fundamental vibrational modes.

C-H Stretching Vibration Region (2650–3000 cm−1): Primary peaks at 2724, 2857, 2887, and 2968 cm−1 correspond to various C-H stretching modes. The dominant peak at 2887 cm−1 exhibits gradual broadening upon cooling but maintains its well-defined structure.

Conventional Cooling of n-Hexane:

The spectra obtained under conventional cooling (

Figure 3) reveal a fundamentally different picture:

250–450 cm−1 Region: A more structured spectrum forms, with well-defined peaks at ~300, ~350, and ~380 cm−1, indicating the formation of a more ordered crystalline structure.

800–1500 cm−1 Region: A significant increase in the number of distinct peaks and peak narrowing is observed. The band at 1453 cm−1 becomes sharper and more intense, demonstrating better crystalline ordering.

2650–3000 cm−1 Region: The C-H stretching vibrations become more clearly resolved with reduced band widths, evidencing the formation of a thermodynamically more stable crystalline modification.

Key Differences Between Cooling Protocols:

Spectral Resolution: Conventional cooling results in significantly better spectral resolution, with the appearance of additional, well-defined peaks.

Band Width: Under fast cooling, the bands remain relatively broad (FWHM ~40–45 cm−1), whereas under conventional cooling, they narrow noticeably (FWHM ~25–30 cm−1).

Intensities: Conventional cooling yields higher intensities for the principal peaks, indicating superior crystalline order.

Despite the differences in the degree of crystalline perfection, both cooling protocols lead to the formation of crystalline structures of n-hexane. Fast cooling produces a defective crystalline structure, while conventional cooling yields a more perfected one; however, a true amorphous state is not achieved in either case.

3.2. Spectral Changes in Decane

Analysis of the decane spectra (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5) demonstrates a fundamentally different behavior compared to n-hexane, with well-defined crystallization observed in both cooling protocols.

Fast Cooling of Decane:

Skeletal Deformation Region (200–500 cm−1): An intense, narrow peak is observed at ~240 cm−1 with a maximum intensity of up to 18,000 arbitrary units, indicating the formation of a highly ordered crystalline structure even under fast cooling. Additional bands at ~280 and ~320 cm−1 suggest a complex crystal lattice with multiple vibrational modes.

C-C Stretching Vibration Region (800–1600 cm−1): The spectrum is characterized by multiple, well-resolved peaks of high intensity at ~850, ~920, ~980, ~1060, ~1130, ~1220, ~1290, ~1380, ~1420, and ~1460 cm−1. The most intense peak at ~1460 cm−1 reaches 14,000 intensity units. The narrowness and clarity of all peaks indicate a high degree of crystalline order.

C-H Stretching Vibration Region (2650–3000 cm−1): The spectrum is dominated by an intense band at ~2880 cm−1 with a maximum intensity of ~7500 units. Additional peaks at ~2720, ~2850, ~2930, and ~2960 cm−1 show clear resolution, characteristic of a crystalline state with an ordered molecular conformation.

Conventional Cooling of Decane:

200–500 cm−1 Region: An even more structured spectrum forms, with the main peak at ~240 cm−1 reaching an intensity of 11,000–12,000 arbitrary units. Additional, well-resolved bands appear, indicating the formation of a thermodynamically more stable crystalline modification.

800–1600 cm−1 Region: A further increase in the number of resolved peaks and an improvement in their sharpness is observed. The intensities of the principal bands are somewhat lower compared to the fast-cooled sample (main peak ~8000 units), but the spectral resolution is significantly improved.

2650–3000 cm−1 Region: The C-H stretching vibrations become even more clearly structured, with the main peak at 2880 cm−1 having a maximum intensity of ~5000 units. Fine structure appears, evidencing a high degree of molecular ordering.

Critical Differences Between the Decane Cooling Protocols:

Crystallization Temperature: In both cases, clear signs of crystallization appear already at temperatures above 150 K, which is significantly higher than the phase transition temperature of n-hexane.

Spectral Clarity: Even under fast cooling, decane exhibits high spectral resolution with narrow peaks characteristic of a well-ordered crystalline structure.

Number of Resolved Peaks: In the 800–1600 cm−1 region, 10–12 clearly resolved peaks are observed, compared to only 3–4 for n-hexane.

Relative Intensities: Fast cooling yields higher intensities, which may indicate the formation of a metastable crystalline modification with conditions particularly favorable for Raman scattering.

Conclusion on Decane: The obtained results convincingly demonstrate that decane has a high propensity for crystallization, which is not suppressed even at the employed fast cooling rates. Highly ordered crystalline structures with clearly defined vibrational spectra are formed, fundamentally different from the defective crystalline structure of n-hexane.

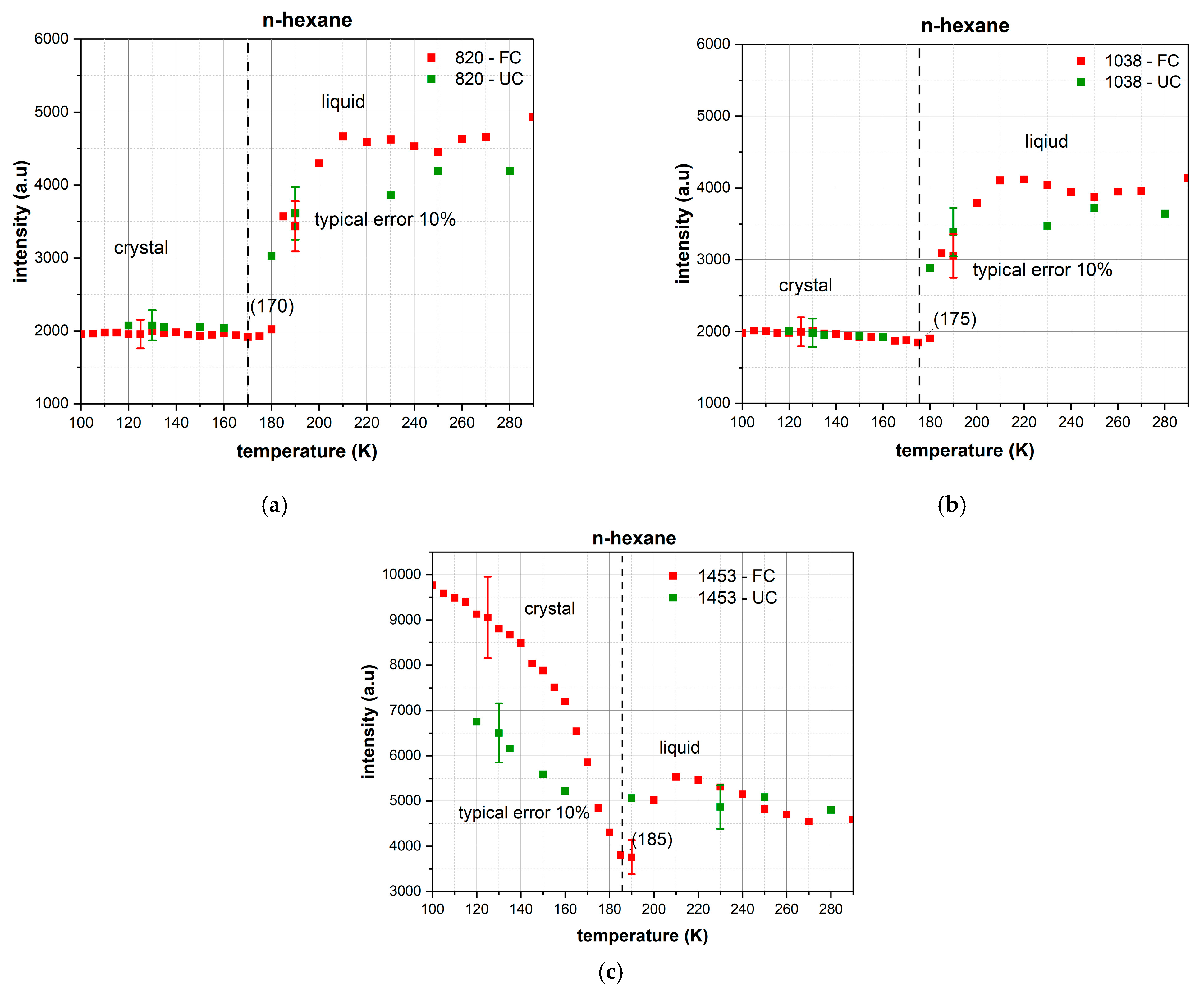

3.3. Quantitative Analysis of Phase Transitions

Temperature-dependent changes in the intensity of characteristic bands (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7) allow for a quantitative characterization of the differences in the behavior of n-hexane and decane under different cooling protocols.

n-Hexane—Analysis of Key Transitions:

820 cm−1 Band (Skeletal Deformations): Under fast cooling, stable behavior is observed with an intensity of ~2000 arbitrary units in the 100–180 K range, followed by a gradual increase to 4500–4700 units by 240 K. Under conventional cooling, the transition is more gradual, reaching 4200 units by 270 K. The critical temperature range for changes is 180–200 K.

1038 cm−1 Band (C-C Stretching Vibrations): Demonstrates complex temperature dependence with relatively stable values of ~2000 units at 100–180 K. Upon heating above 180 K, the intensity gradually increases, reaching 4100 units at 210 K for fast cooling and 3500 units for conventional cooling.

1453 cm−1 Band (CH2 Deformation): This is the band most sensitive to the cooling protocol. Under fast cooling, it shows a maximum intensity of 9800 units at 100 K, gradually decreasing to a minimum of 3800 units at 180 K. Under conventional cooling, the maximum is 6700 units at 100 K with a similar decrease to 5100 units at 180 K.

Analysis of Phase Transitions via Temperature-Dependent Intensity:

Transition 1 (100–170 K)—Stable Crystalline Structure: The 1453 cm−1 band exhibits maximum intensity at 100 K, followed by a gradual decrease until 170 K. Spectral data show clear, narrow peaks characteristic of a well-ordered crystal lattice.

Transition 2 (175–180 K)—Melting of n-Hexane: A critical transition for n-hexane occurs at a temperature close to its literature melting point (177.8 K), characterized by:

A minimum in the intensity of the 1453 cm−1 band at 180 K.

Significant broadening and reduction in intensity of the principal Raman peaks.

Destruction of the long-range order of the crystal structure.

Sample Evaporation (above 250 K): The observed increase in band intensities at temperatures above 250 K is associated with the evaporation of the liquid sample from the substrate, not with phase transitions. The slow heating rate (2.8 K/min) and high volatility of n-hexane lead to changes in film thickness and the optical conditions for spectral acquisition.

Decane—Analysis of Crystallization Transitions:

885 cm−1 Band (C-C vibrations): Under fast cooling, it shows high intensities (7500–7900 arbitrary units) at 80–100 K, gradually decreasing to 6200 units at 220 K, followed by a sharp drop to 3100 units at 240 K.

1009 cm−1 Band (C-C stretching vibrations): Exhibits a smooth decrease in intensity from 3300 units (80 K) to 2650 units (240 K) under fast cooling.

2881 cm−1 Band: Corresponds to C-H stretching vibrations (symmetric CH2 stretching modes).

Analysis of Phase Transitions via Temperature-Dependent Intensity:

Transition 1 (80–140 K)—Crystalline Stabilization: In this range, the maximum intensity of the characteristic bands is observed, indicating the formation of a well-ordered crystalline structure.

Transition 2 (220–240 K)—Polymorphic Transition in Decane: The observed changes characterize a transition between different crystalline modifications of decane, preceding melting.

Sample Evaporation (above 260 K): The gradual decrease in intensity of all characteristic bands at temperatures above 260 K is associated with the evaporation of the liquid sample from the substrate, not with premelting processes, given that the melting point of decane is 243.5 K.

Critical Temperatures of Phase Transitions:

n-Hexane: Major structural changes occur in the 180–200 K range for all studied bands, corresponding to the melting of the crystalline structure.

Decane: A well-defined transition at 220–240 K, particularly noticeable for the 885 cm−1 band, indicates a polymorphic transformation in the decane crystal lattice.

Key Differences Between the Alkanes:

Transition Intensities: Decane exhibits significantly higher Raman band intensities.

Temperature Ranges: Critical changes in decane occur at higher temperatures.

Nature of Transitions: Decane shows sharper, more abrupt changes in intensity.

All intensity changes at temperatures significantly exceeding the melting points of the samples (above 250 K for hexane and above 260 K for decane) (

Table 1) are associated with sample evaporation and changes in optical measurement conditions, not with phase transitions.

Interpretation of Temperature Dependencies:

Analysis of the quantitative data confirms fundamental differences in the crystallization mechanisms of the studied alkanes. n-Hexane demonstrates broad, gradual transitions with relatively low intensities, characteristic of the formation of defective crystalline structures. Decane shows sharp, high-intensity transitions at specific temperatures, indicating the formation of well-ordered crystalline phases.

The behavior of the 1453 cm−1 band in n-hexane is particularly indicative, showing maximum sensitivity to the cooling protocol—the intensity difference between fast and conventional cooling reaches 3300 arbitrary units at low temperatures. This confirms the formation of different crystalline modifications depending on the kinetic conditions.

The absence of vitrification in this study is explained by:

Insufficient Cooling Rate: Contact freezing on a copper substrate in the “fast cooling” regime provides cooling rates on the order of 102–103 K/s, which is significantly lower than the critical rates required to suppress alkane crystallization (>104 K/s).

Excessive Sample Thickness: Contact deposition via syringe forms films with thicknesses > 10 µm, whereas ultra-thin films < 1 µm are necessary for effective vitrification. In thick films, bulk crystallization processes dominate, and molecules have sufficient time to order.

Thermodynamic Factors: The studied alkanes (n-hexane and decane) possess relatively simple molecular structures and efficient van der Waals interactions, which promote rapid crystallization even at moderate cooling rates.

Thus, the employed contact freezing method, while suitable for studying structural changes during phase transitions, is fundamentally incapable of providing the conditions necessary for obtaining amorphous states of alkanes.

3.4. Analysis of Contact Freezing Method Limitations

The observed differences between n-hexane and decane reflect the influence of molecular chain length on crystallization processes.

n-Hexane (C6H14): The short molecular chain hinders the formation of perfect crystalline packing, leading to a defective crystalline structure with enhanced disorder. This manifests as broadening of spectral bands and a diffuse phase transition character, but does not signify true vitrification.

Decane (C10H22): The optimal chain length for efficient crystalline packing and stronger intermolecular interactions ensures the formation of a well-ordered crystalline structure even under fast cooling, which melts in the 220–240 K range.