Wide Angle X-Ray Scattering to Study the Atomic Structure of Polymeric Fibers

Abstract

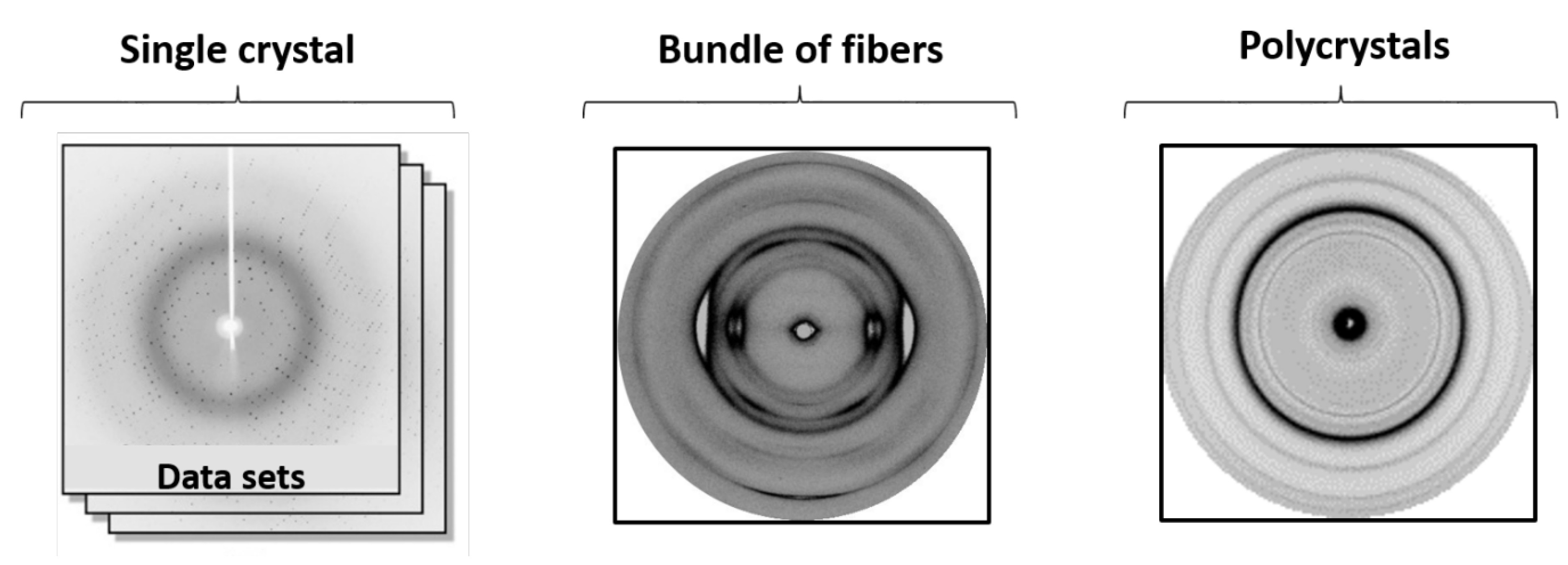

1. Introduction

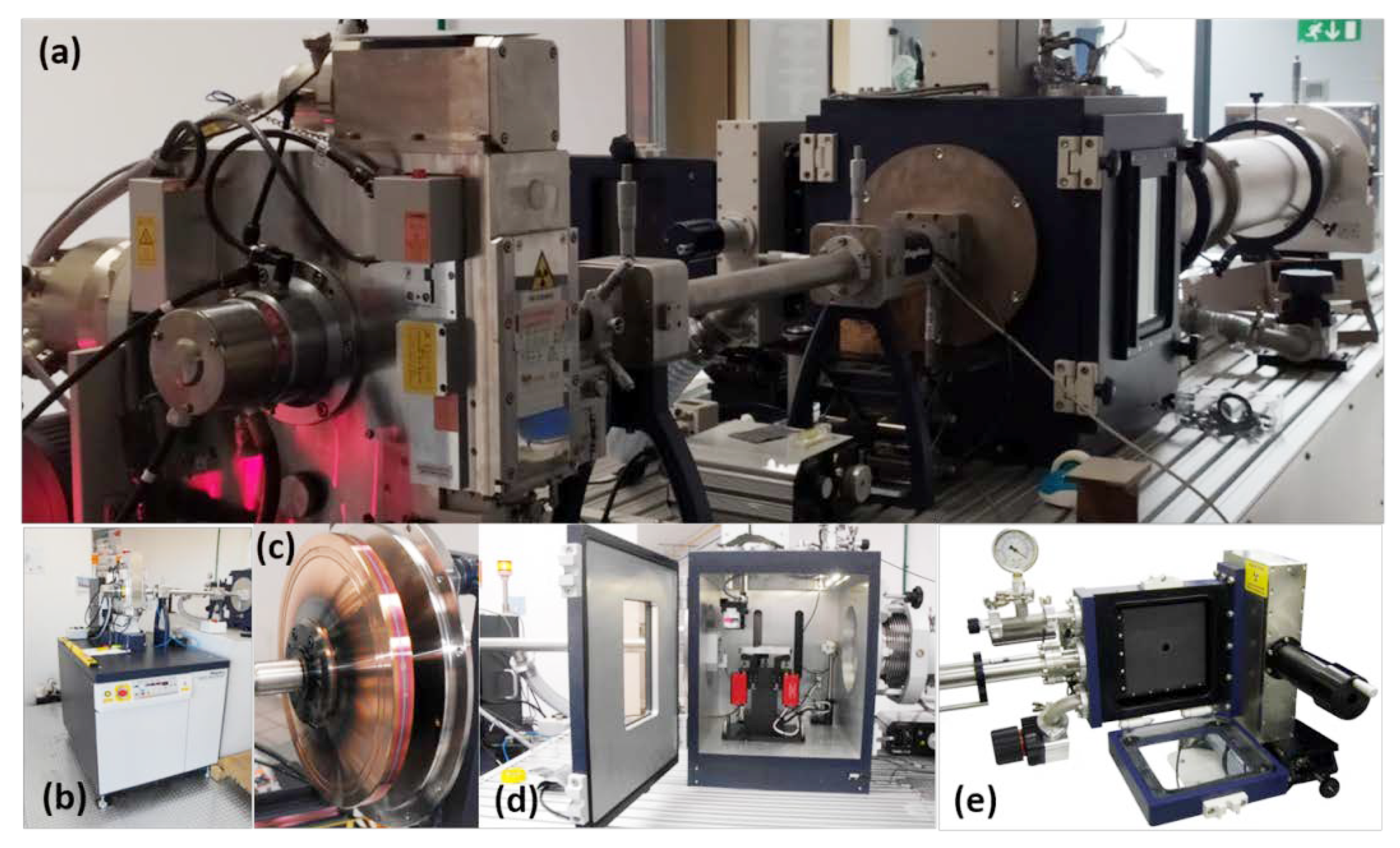

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

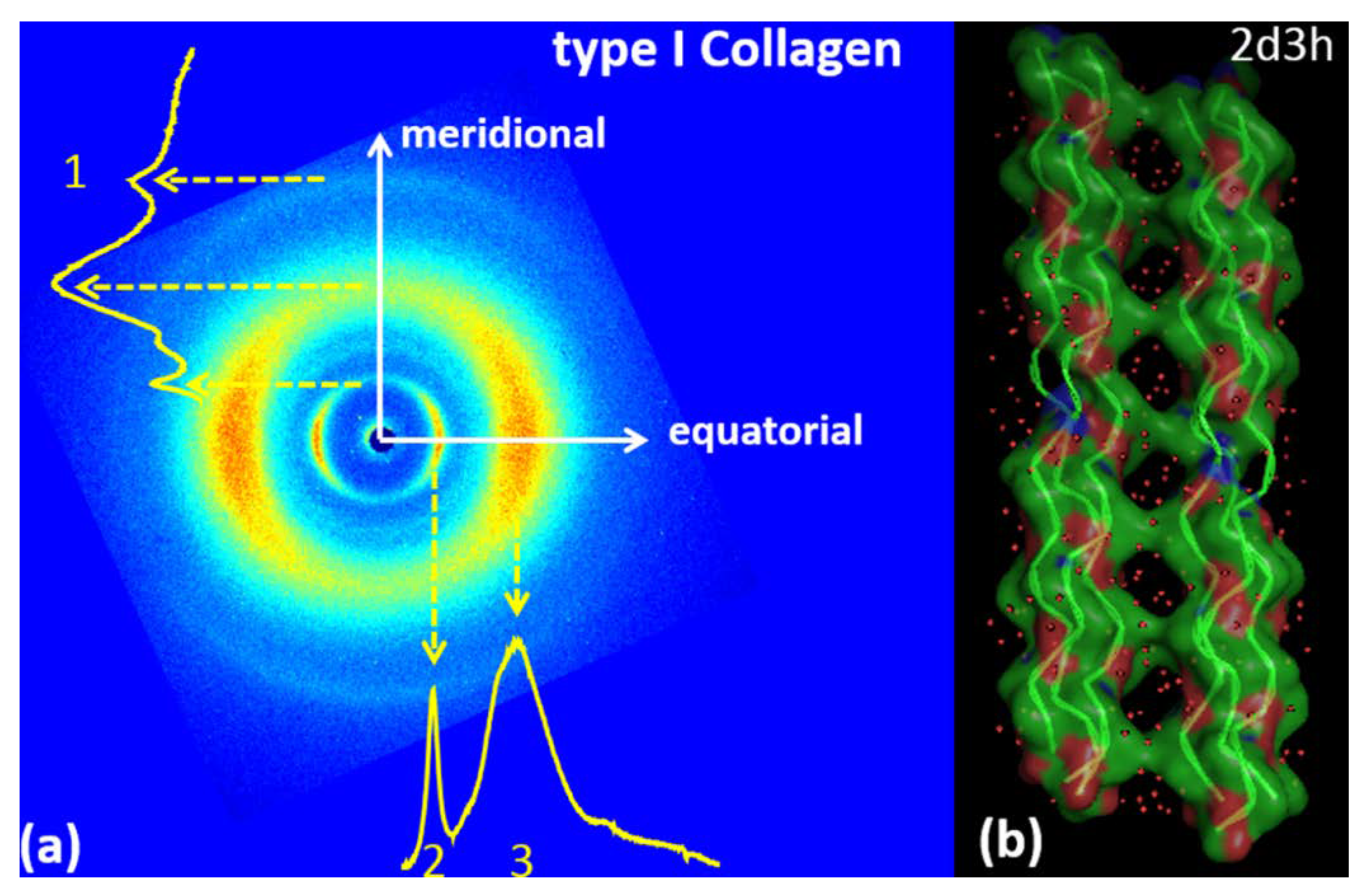

3.1. Type I Collagen

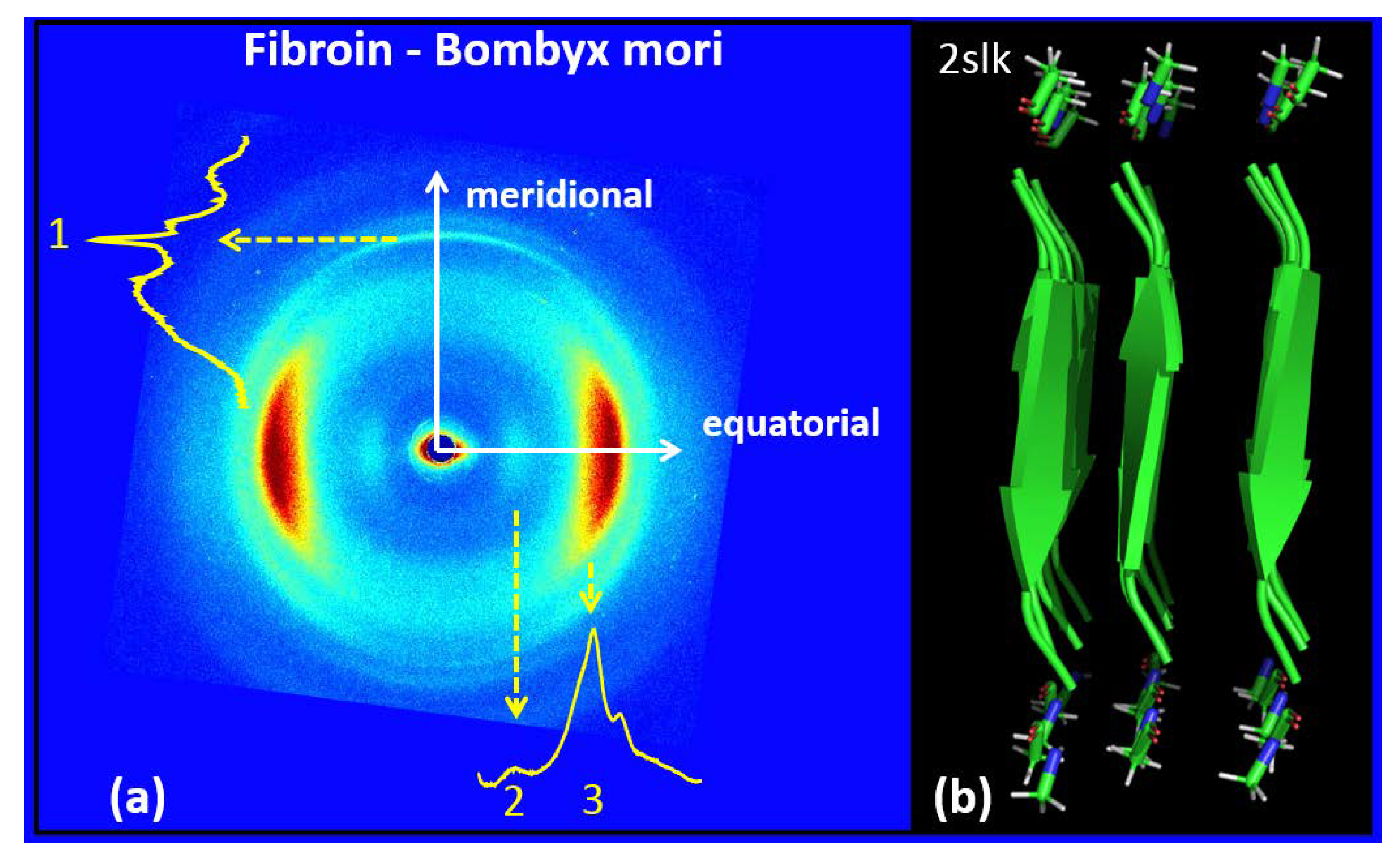

3.2. Silk Fibroin from Bombyx Mori

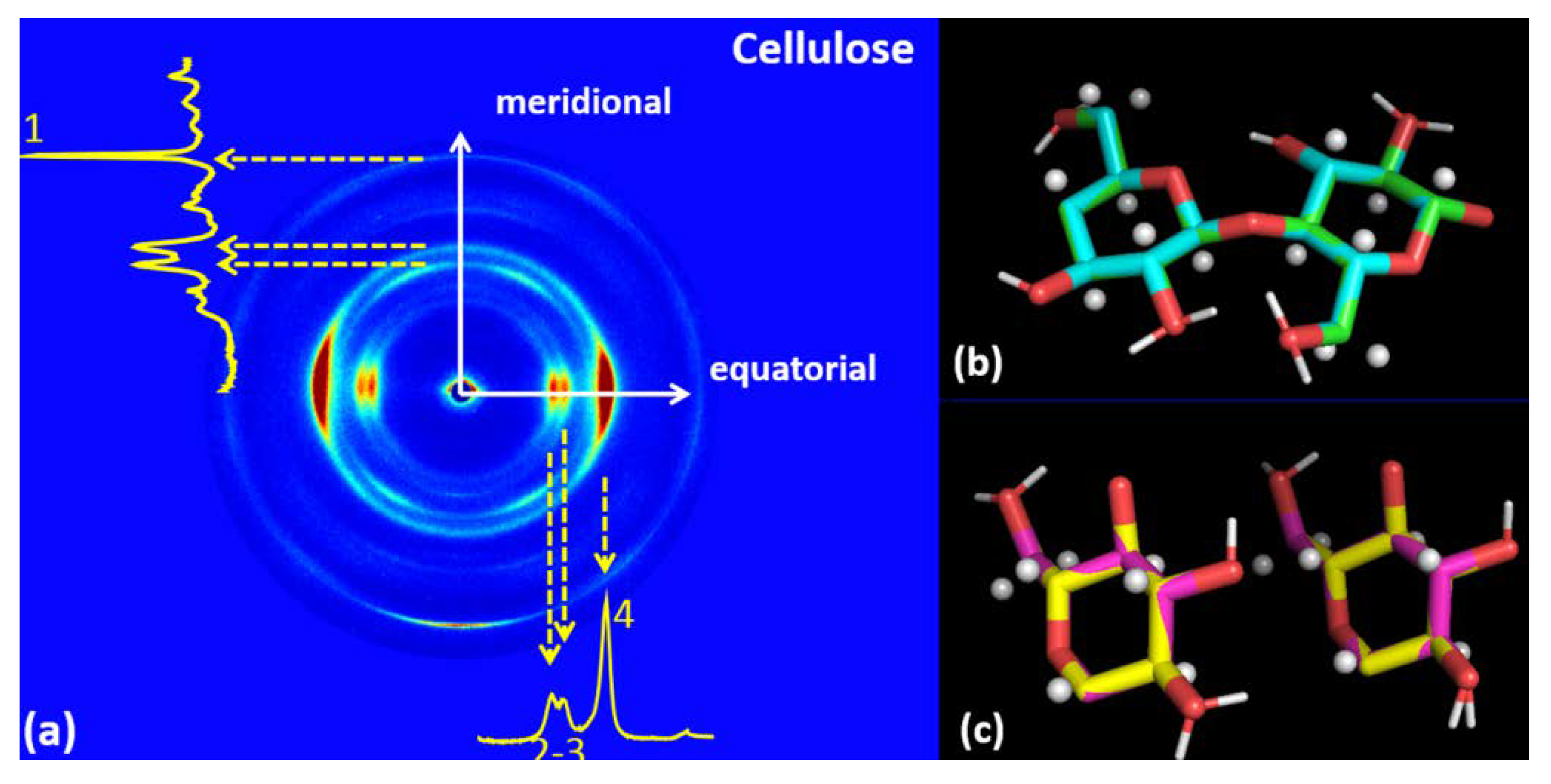

3.3. Cellulose

4. Conclusions and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nguyen, L.T.H.; Chen, S.; Elumalai, N.K.; Prabhakaran, M.P.; Zong, Y.; Vijila, C.; Allakhverdiev, S.I.; Ramakrishna, S. Biological, Chemical, and Electronic Applications of Nanofibers, Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2013, 298, 822–867. [Google Scholar]

- Ko, F.K.; Wan, Y. Introduction to Nanofiber Materials; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Nemati, S.; Kim, S.; Shin, Y.M.; Shin, H. Current progress in application of polymeric nanofibers to tissue engineering. Nano Converg. 2019, 6, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obaid, M.; Barakat, N.A.; Fadali, O.A.; Al-Meer, S.; Elsaid, K.; Khalil, K.A. Stable and effective super-hydrophilic polysulfone nanofiber mats for oil/water separation. Polymer 2015, 72, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Ma, S.Y.; Wang, T.T.; Li, X.B.; Luo, J.; Li, W.Q.; Mao, Y.Z.D.; GZ, J. Synthesis and characterization of SnO2 hollow nanofibers by electrospinning for ethanol sensing properties. Mater. Lett. 2014, 131, 23–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.L.; Huang, H.Z.; Liang, W.H.; Guan, F.Q.; Yu, H.S. Bacterial-cellulose-derived carbon nanofiber MnO2 and nitrogen-doped carbon nanofiber electrode materials: An asymmetric supercapacitor with high energy and power density. Adv. Mater. 2013, 25, 4746–4752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altamura, D.; Pastore, S.G.; Raucci, M.G.; Siliqi, D.; De Pascalis, F.; Nacucchi, M.; Ambrosio, L.; Giannini, C. Scanning small- and wide-angle X-ray scattering microscopy selectively probes ha content in gelatin/hydroxyapatite scaffolds for osteochondral defect repair. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 8728–8736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’brien, F.J. Biomaterials & scaffolds for tissue engineering. Mater. Today 2011, 14, 88. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, A.; Wang, X.Y.; Kaplan, D.L.; Garlick, J.A.; Egles, C. Biofunctionalized electrospun silk mats as a topical bioactive dressing for accelerated wound healing. Acta Biomater. 2009, 5, 2570–2578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.Q.; He, J.H.; Yu, J.Y. Carbon nanotube-reingorced polyacrylonitrile nanofibers by vibration-electrospinning. Polym. Int. 2007, 56, 1367–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranganath, A.S.; Ganesh, V.A.; Sopiha, K.; Sahay, R.; Baji, A. Investigation of wettability and moisture sorption property of electrospun poly (N-isopropylacrylamide) nanofibers. MRS Adv. 2016, 1, 1959–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosi, A.; Sasaki, T.; Pumera, M. Platelet graphite nanofibers for electrochemical sensing and biosensing: The influence of graphene sheet orientation. Chem. Asian. J. 2010, 5, 266–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terzi, A.; Gallo, N.; Bettini, S.; Sibillano, T.; Altamura, D.; Madaghiele, M.; De Caro, L.; Valli, L.; Salvatore, L.; Sannino, A.; et al. Sub and supramolecular X-ray characterization of engineered tissues from equine tendons, bovine dermis and fish skin type-I collagen. Macromol. Biosci. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sibillano, T.; De Caro, L.; Scattarella, F.; Scarcelli, G.; Siliqi, D.; Altamura, D.; Liebi, M.; Ladisa, M.; Bunk, O.; Giannini, C. Interfibrillar packing of bovine cornea by table-top and synchrotron scanning SAXS microscopy. J. Appl. Cryst. 2016, 49, 1231–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannini, C.; DSiliqi, D.; Ladisa, M.; Altamura, D.; Diaz, A.; Beraudi, A.; Sibillano, T.; De Caro, L.; Stea, S.; Baruffaldi, F.; et al. Scanning SAXS–WAXS microscopy on osteoarthritis-affected bone—An age-related study. J. Appl. Cryst. 2014, 47, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannini, C.; Terzi, A.; Fusaro, L.; Sibillano, T.; Diaz, A.; Ramella, M.; Lutz-Bueno, V.; Boccafoschi, F.; Bunk, O. Scanning X-ray microdiffraction of decellularized pericardium tissue at increasing glucose concentration. J. Biophotonics 2019, 12, e201900106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannini, C.; Ladisa, M.; Lutz, V.-B.; Terzi, A.; Ramella, M.; Fusaro, L.; Altamura, D.; Siliqi, D.; Sibillano, T.; Diaz, A.; et al. X-ray scanning microscopies of microcalcifications in abdominal aortic and popliteal artery aneurysms. IUCrJ 2019, 6, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaferia, C.; Mercurio, F.A.; Giannini, C.; Sibillano, T.; Morelli, G.; Leone, M.; Accardo, A. Self-assembly of PEGylated tetra-phenylalanine derivatives: Structural insights from solution and solid state studies. Sci. Rep. 2019, 6, 26638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viell, J.; Inouye, H.; Szekely, N.K.; Frielinghaus, H.; Marks, C.; Wang, Y.; Anders, N.; Spiess, A.C.; Makowski, L. Multi-scale processes of beech wood disintegration and pretreatment with 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate/water mixtures. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2016, 9, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, X.; Dulle, M.; Martins de Souza e Silva, J.; Wehrspohn, R.B.; Agarwal, S.; Förster, S.; Hou, H.; Smith, P.; Greiner, A. High strength in combination with high toughness in robust and sustainable polymeric materials. Science 2019, 366, 1376–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, E.; Hopkinson, I.; Hayashi, T. Basement-Membrane Stromal Relationships: Interactions between Collagen Fibrils and the Lamina Densa. Int. Rev. Cytol. 1997, 173, 73–156. [Google Scholar]

- Sorushanova, A.; Delgado, L.M.; Wu, Z.; Shologu, N.; Kshirsagar, A.; Raghunath, R.; Mullen, A.M.; Bayon, Y.; Pandit, A.; Raghunath, M.; et al. The Collagen Suprafamily: From Biosynthesis to Advanced Biomaterial Development. Adv. Mat. 2019, 31, 1801651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parenteau-Bareil, R.; Gauvin, R.; Berthod, F. Collagen-Based Biomaterials for Tissue Engineering. Appl. Mat. 2010, 3, 1863–1887. [Google Scholar]

- Persikov, A.V.; Pillitteri, R.J.; Amin, P.; Schwarze, U.; Byers, P.H.; Brodsky, B. Stability related bias in residues replacing glycines within the collagen triple helix (Gly-Xaa-Yaa) in inherited connective tissue disorders. Human Mutat. 2004, 24, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramachandran, G.N.; Kartha, G. Structure of Collagen. Nature 1955, 176, 593–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cen, L.; Liu, W.; Cui, L.; Zhang, W.; Cao, Y. Collagen tissue engineering: Development of novel biomaterials and applications. Pediatr Res. 2008, 63, 492–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimni, M.E.; Cheung, D.; Strates, B.; Kodama, M.; Sheikh, K. Chemically modified collagen: A natural biomaterial for tissue replacement. Biomed. Mat. Res. 1987, 21, 741–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knapp, T.R.; Luck, E.; Daniels, J.R. Behavior of solubilized collagen as a bioimplant. J. Surg. Res. 1977, 23, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, S.; Ono, S. Transmission of X-rays through fibrous, lamellar and granular substances. Proc. Tokyo Math Phys. Soc. 1913, 7, 131. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, R.E.; Corey, R.B.; Pauling, L. An investigation of the structure of silk Fibroin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1955, 16, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimura, K. Chemical composition and biosynthesis of silk proteins. Experimentia 1983, 39, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takashi, Y.; Gehoh, M.; Yuzuriha, K. Structure refinement and diffuse streak scattering of silk (Bombyx mori). Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 1999, 24, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asakura, T.; Ohata, T.; Kametani, S.; Okushita, K.; Yazawa, K.; Nishiyama, Y.; Nishimura, K.; Aoki, A.; Suzuki, F.; Kaji, H.; et al. Intermolecular packing in B. mori silk fibroin: Multinuclear NMR Study of the model peptide (Ala-Gly)) defines a heterogeneous antiparallel antipolar mode of assembly in the Silk II form. Macromolecules 2015, 48, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, A.C. Cellulose: The structure slowly unravels. Cellulose 1997, 4, 173–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanderHart, D.L.; Atalla, R.H. Studies of microstructure in native celluloses using solid-state carbon-13 NMR. Macromolecules 1984, 17, 1465–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama, J.; Vuong, R.; Chanzy, H. Electron diffraction study on the two crystalline phases occurring in native cellulose from an algal cell wall. Macromolecules 1991, 24, 4168–4175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, Y.; Lucia, L.A.; Rojas, O.J. Cellulose nanocrystals: Chemistry, self-assembly, and applications. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 3479–3500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, R.N.; Schliesser, J.; Mittal, A.; Decker, S.R.; Santos, A.F.; LO, M.; Freitas, V.L.S.; Urbas, A.; Lang, B.E.; Heiss, C.; et al. A thermodynamic investigation of the cellulose allomorphs: Cellulose(am), cellulose Iβ(cr), cellulose II(cr), and cellulose III(cr). J. Chem. Thermodyn. 2015, 81, 184–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorieul, M.; Dickson, A.; Hill, J.; Pearson, H. Plant Fibre: Molecular Structure and Biomechanical Properties, of a Complex Living Material, Influencing Its Deconstruction towards a Biobased Composite. Materials 2016, 9, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poma, A.B.; Chwastyk, M.; Cieplak, M. Coarse-grained model of the native cellulose Iαand the transformation pathways to the Iβ allomorph. Cellulose 2016, 23, 1573–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brett, C.T. Cellulose microfibrils in plants: Biosynthesis, deposition, and integration into the cell wall. In International Review of Cytology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000; Volume 199, pp. 161–199. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, C.T.; Carroll, A.; Akhmetova, L.; Somerville, C. Real-time imaging of cellulose reorientation during cell wall expansion in Arabidopsis roots. Plant Physiol. 2010, 152, 787–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, R.H.; Hemmingson, J.A. Carbon-13 NMR distinction between categories of molecular order and disorder in cellulose. Cellulose 1994, 2, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terzi, A.; Storelli, E.; Bettini, S.; Sibillano, T.; Altamura, D.; Salvatore, L.; Madaghiele, M.; Romano, A.; Siliqi, D.; Ladisa, M.; et al. Effect of processing on structural, mechanical and biological properties of collagen-based substrates for regenerative medicine. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terzi, A.; Gallo, N.; Bettini, S.; Sibillano, T.; Altamura, D.; Campa, L.; Natali, M.L.; Salvatore, L.; Madaghiele, M.; De Caro, L.; et al. Investigation of processing-induced structural changes in horse type-I collagen at sub and supramolecular levels. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2019, 7, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Caro, L.; Giannini, C.; Lassandro, R.; Scattarella, F.; Sibillano, T.; Matricciani, E.; Fanti, G. X-ray dating of ancient linen fabrics. Heritage 2019, 2, 2763–2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altamura, D.; Lassandro, R.; Vittoria, F.A.; De Caro, L.; Siliqi, D.; Ladisa, M.; Giannini, C. X-ray microimaging laboratory (XMI-LAB). J. Appl. Cryst. 2012, 45, 869–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibillano, T.; De Caro, L.; Altamura, D.; Siliqi, D.; Ramella, M.; Boccafoschi, F.; Ciasca, G.; Campi, G.; Tirinato, L.; Di Fabrizio, E.; et al. An Optimized Table-Top Small-Angle X-ray Scattering Set-up for the Nanoscale Structural Analysis of Soft Matter. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 6985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rich, A.; Crick, F.H.C. The molecular structure of collagen. J. Mol. Biol. 1961, 3, 483–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuyama, K.; Xu, X.; Iguchi, M.; Noguchi, K. Revision of collagen molecular structure. Biopolymers 2006, 84, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuyama, K.; Hongo, C.; Wu, G.; Mizuno, K.; Noguchi, K.; Ebisuzaki, S.; Tanaka, Y.; Nishino, N.; Bachinger, H.P. High-resolution structures of collagen-like peptides [(Pro-Pro-Gly)(4)-Xaa-Yaa-Gly-(Pro-Pro-Gly)(4)]: Implications for triple-helix hydration and Hyp(X) puckering. Biopolymers 2009, 91, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bella, J.; Brodsky, B.; Berman, H.B. Hydration structure of a collagen peptide. Structure 1995, 3, 893–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraud-Guille, M.-M. Liquid crystallinity in condensed type I collagen solutions: A clue to the packing of collagen in extracellular matrices. J. Mol. Biol 1992, 224, 861–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossey, S.A.; Némethy, G.; Gibson, K.D.; Scheraga, H.A. Conformational energy studies of beta-sheets of model silk fibroin peptides. I. Sheets of poly(Ala-Gly) chains. Biopolymers 1991, 31, 1529–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, C.; Zhang, J.; Jordan, J.S.; Wang, X.; Henning, R.W.; Yarger, J.L. Structural Comparison of Various Silkworm Silks: An Insight into the Structure−Property Relationship. Biomacromolecules 2018, 19, 906–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.Z.; Confalonieri, F.; Jacquet, M.; Perasso, R.; Li, Z.G.; Janin, J. Silk Fibroin: Structural Implications of a Remarkable Amino Acid Sequence. Proteins 2001, 44, 119–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leppänen, K.; Andersson, S.; Torkkeli, M.; Knaapila, M.; Kotelnikova, N.; Serimaa, R. Structure of cellulose and microcrystalline cellulose from various wood species, cotton and flax studied by X-ray scattering. Cellulose 2009, 16, 999–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Su, Y.; Hsiao, B.S. Probing structure and orientation in polymers using synchrotron small- and wide-angle X-ray scattering techniques. Eur. Polym. J. 2016, 81, 433–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaferia, C.; Sibillano, T.; Balasco, N.; Giannini, C.; Roviello, V.; Vitagliano, L.; Morelli, G.; Accardo, A. Hierarchical Analysis of Self-Assembled PEGylated Hexaphenylalanine Photoluminescent Nanostructures. Chem. Eur. J. 2016, 22, 16586–16597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaferia, C.; Sibillano, T.; Altamura, D.; Roviello, V.; Vitagliano, L.; Giannini, C.; Morelli, G.; Accardo, A. Structural Characterization of PEGylated Hexaphenylalanine Nanostructures Exhibiting Green Photoluminescence Emission. Chem. Eur. J. 2017, 56, 14039–14048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaferia, C.; Gianolio, E.; Sibillano, T.; Mercurio, F.A.; Leone, M.; Giannini, C.; Balasco, N.; Vitagliano, L.; Morelli, G.; Accardo, A. Cross-beta nanostructures based on dinaphthylalanine Gd-conjugates loaded with doxorubicin. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| TYPE 1 COLLAGEN | |

| Meridional | Equatorial |

| q1 = 2.22 ± 0.075 Å−1; d1 = 2.83 ± 0.1 Å | q2 = 0.59 ± 0.05 Å−1; d2 = 10.65 ± 1Å |

| q3 = 1.39 ± 0.25 Å−1; d3 = 4.52 ± 0.85Å | |

| FIBROIN–BOMBYX MORI | |

| Meridional | Equatorial |

| q1 = 1.78 ± 0.03Å−1; d1 = 3.53 ± 0.06 Å | q2 = 0.66 ± 0.075 Å−1; d2 = 9.52 ± 1 Å |

| q3 = 1.44 ± 0.08 Å−1; d3 = 4.36 ± 0.25 Å | |

| CELLULOSE | |

| Meridional | Equatorial |

| q1 = 2.43 ± 0.015 Å−1; d1 = 2.58 ± 0.01 Å | q2 = 1.05 ± 0.04Å−1; d2 = 6.00 ± 0.25 Å |

| q3 = 1.18 ± 0.025Å−1; d3 = 5.32 ± 0.15 Å | |

| q4 = 1.60 ± 0.04 Å−1; d4= 3.93 ± 0.1Å | |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sibillano, T.; Terzi, A.; De Caro, L.; Ladisa, M.; Altamura, D.; Moliterni, A.; Lassandro, R.; Scattarella, F.; Siliqi, D.; Giannini, C. Wide Angle X-Ray Scattering to Study the Atomic Structure of Polymeric Fibers. Crystals 2020, 10, 274. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst10040274

Sibillano T, Terzi A, De Caro L, Ladisa M, Altamura D, Moliterni A, Lassandro R, Scattarella F, Siliqi D, Giannini C. Wide Angle X-Ray Scattering to Study the Atomic Structure of Polymeric Fibers. Crystals. 2020; 10(4):274. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst10040274

Chicago/Turabian StyleSibillano, Teresa, Alberta Terzi, Liberato De Caro, Massimo Ladisa, Davide Altamura, Anna Moliterni, Rocco Lassandro, Francesco Scattarella, Dritan Siliqi, and Cinzia Giannini. 2020. "Wide Angle X-Ray Scattering to Study the Atomic Structure of Polymeric Fibers" Crystals 10, no. 4: 274. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst10040274

APA StyleSibillano, T., Terzi, A., De Caro, L., Ladisa, M., Altamura, D., Moliterni, A., Lassandro, R., Scattarella, F., Siliqi, D., & Giannini, C. (2020). Wide Angle X-Ray Scattering to Study the Atomic Structure of Polymeric Fibers. Crystals, 10(4), 274. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst10040274