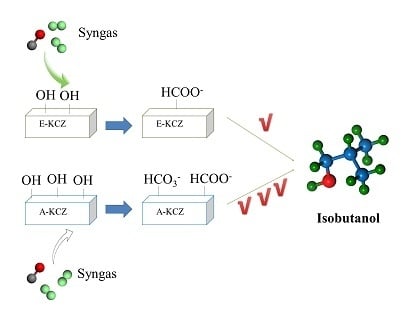

Effect of Preparation Method on ZrO2-Based Catalysts Performance for Isobutanol Synthesis from Syngas

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussions

2.1. Catalytic Performance

2.2. Textural Properties

2.3. Powder XRD Measurements

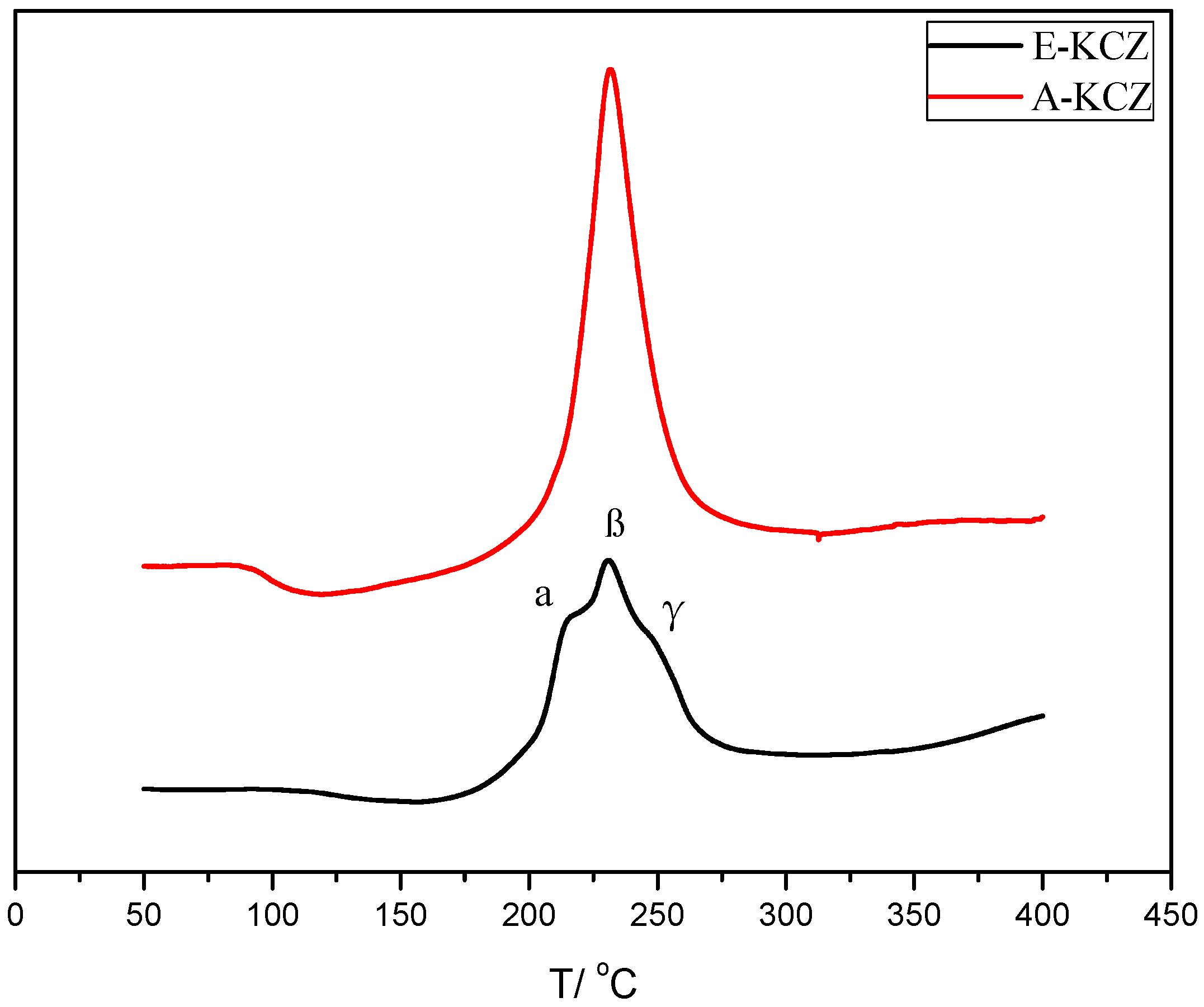

2.4. H2-TPR Analysis

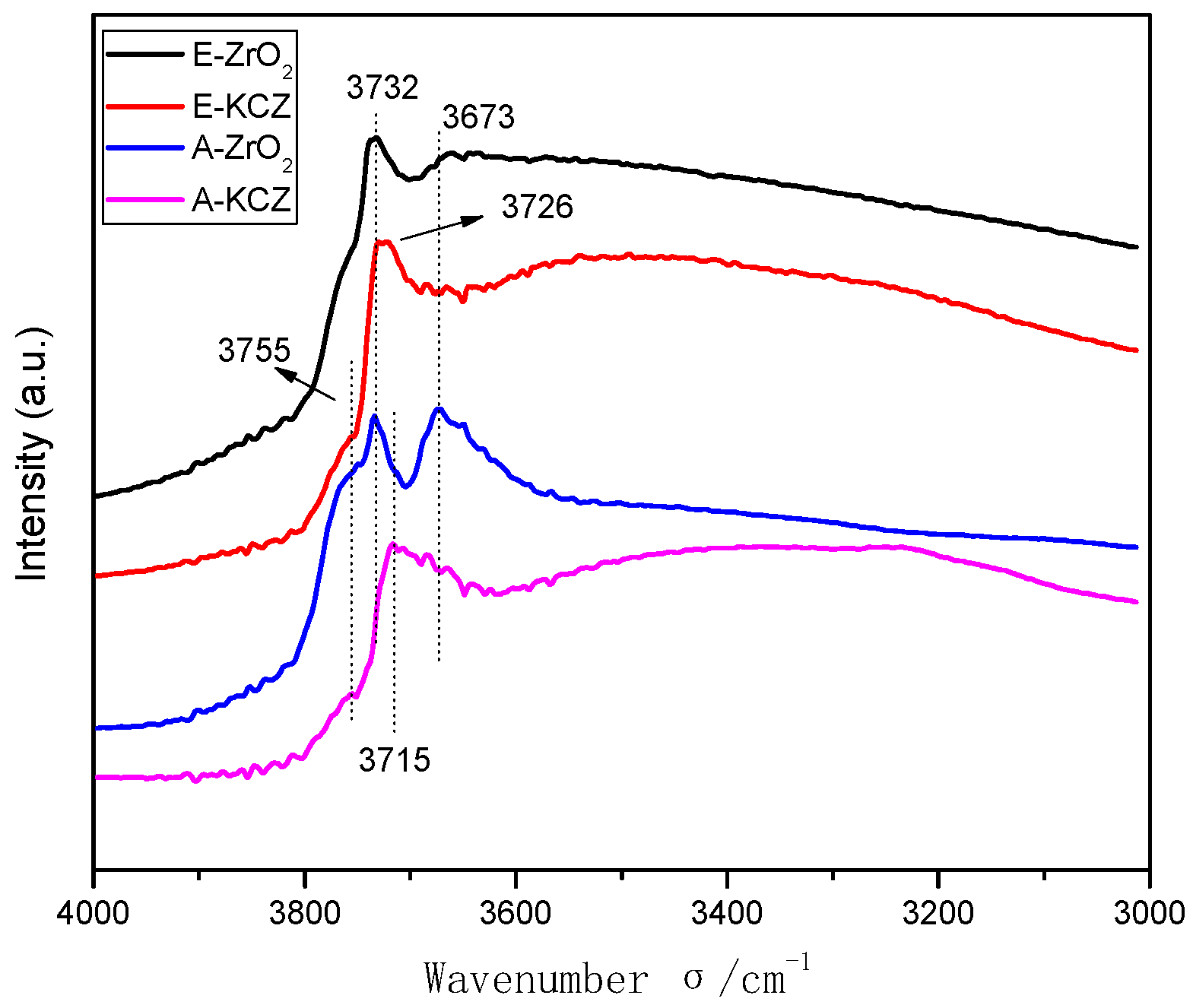

2.5. Hydroxyl Groups on Different Catalysts

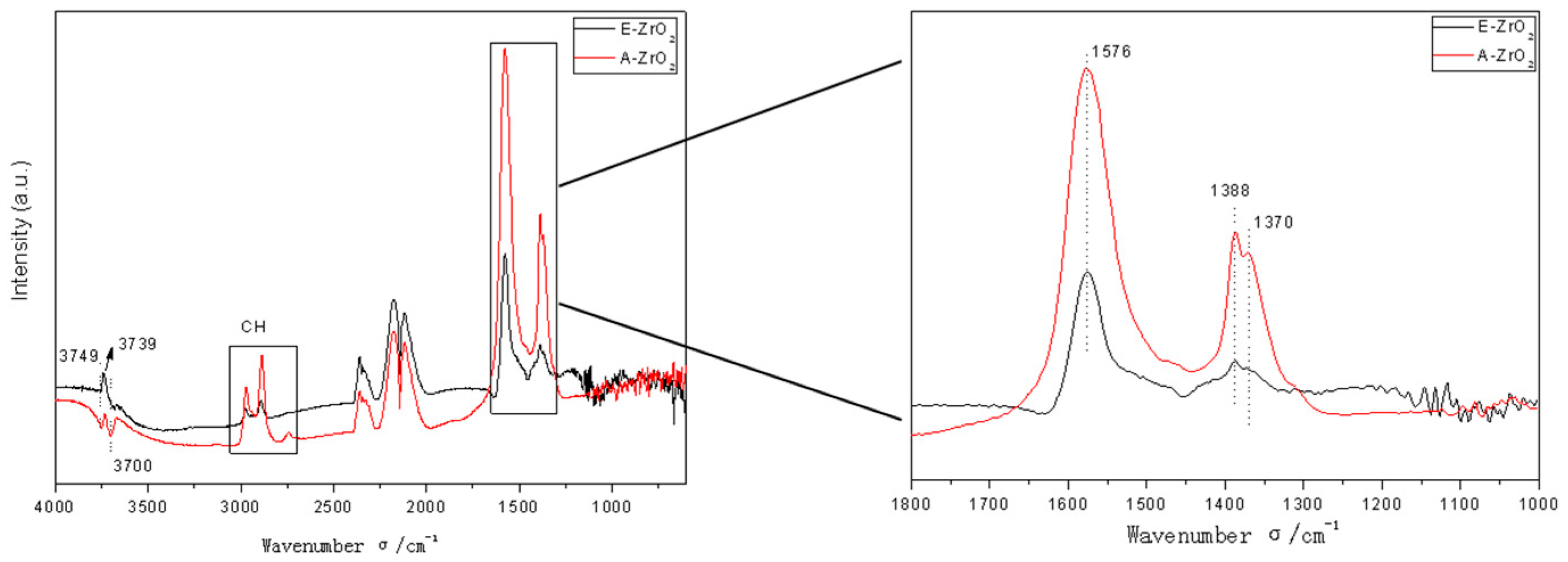

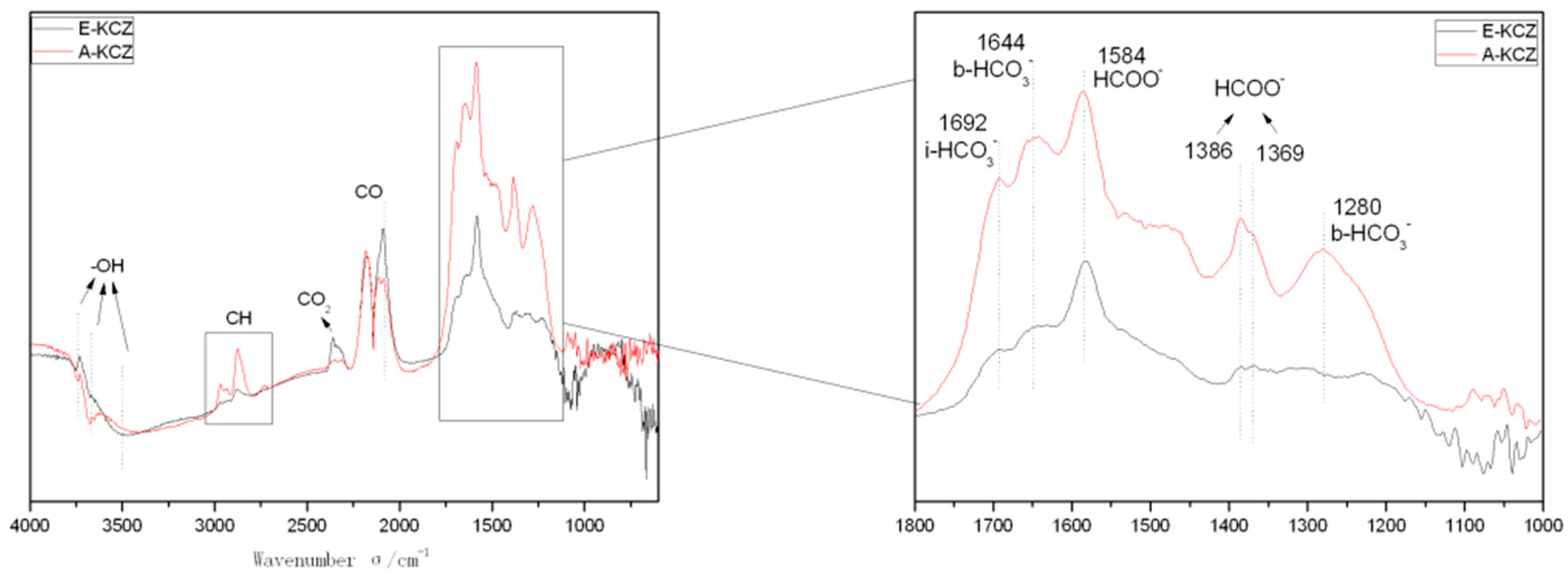

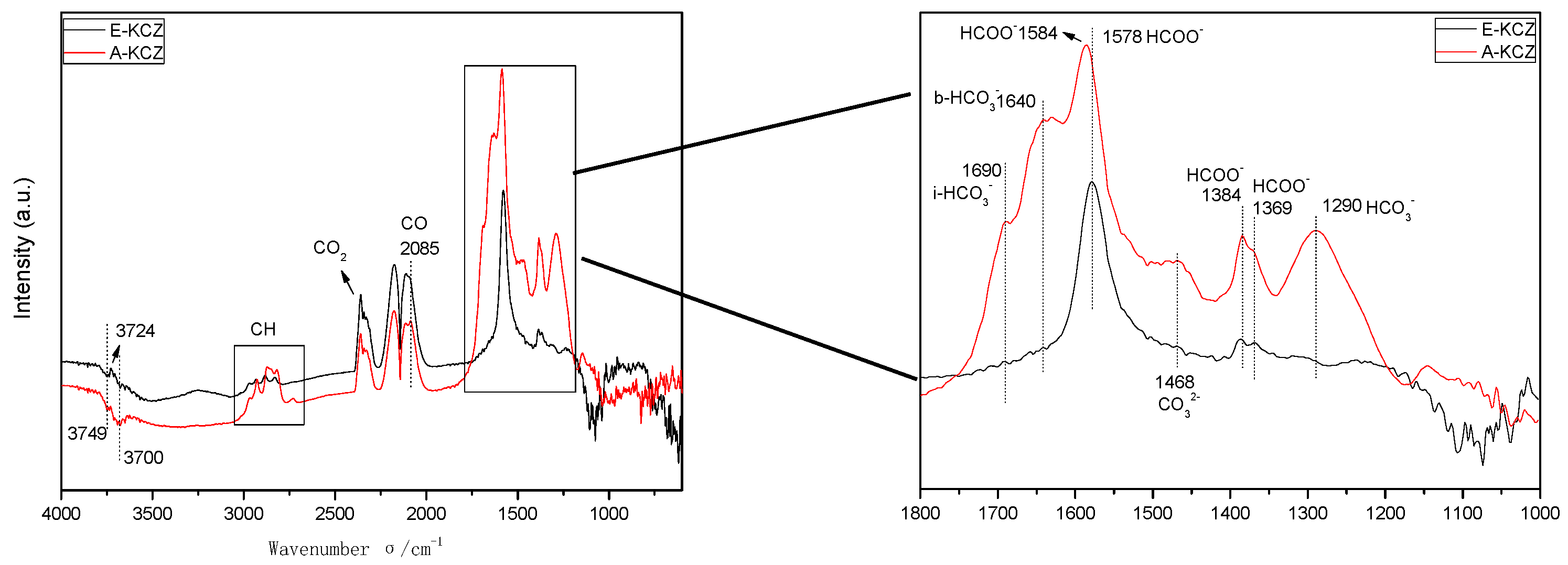

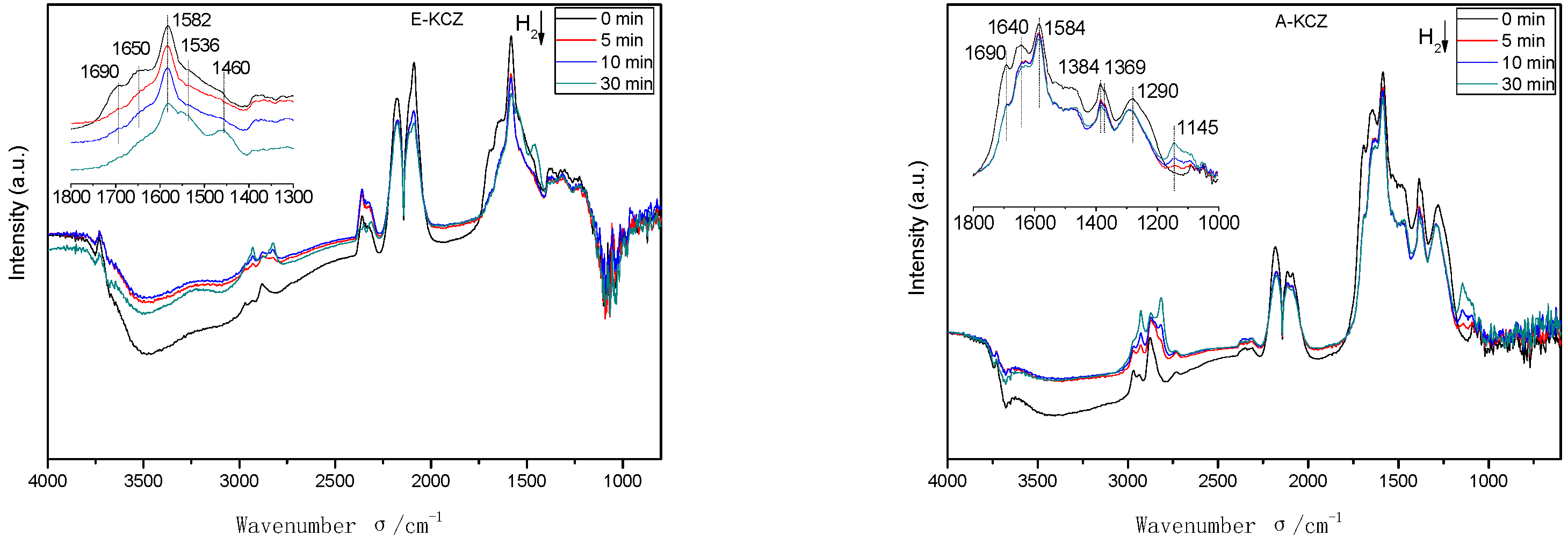

2.6. In Situ DRIFTS Analysis

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Catalyst Preparation

3.2. Catalyst Characterization

3.3. Catalyst Evaluation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, M.; Xie, H.; Wu, Y.; Tan, Y. The Support effects on the direct conversion of syngas to higher alcohol synthesis over copper-based catalysts. Catalysts 2019, 9, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Su, J.; Zhang, Z.; Cao, C.; Wang, X.; Si, R.; Liu, X.; Shi, B.; Xu, J.; Han, Y. Structure Evolution of Co−CoOx Interface for higher alcohol synthesis from syngas over Co/CeO2 catalysts. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 8606–8617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Gao, X.; Bai, Y.; Tan, M.; Yang, G.; Tan, Y. Synergetic catalysis of bimetallic copper–cobalt nanosheets for direct synthesis of ethanol and higher alcohols from syngas. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2018, 8, 3936–3947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luk, H.T.; Mondelli, C.; Mitchell, S.; Siol, S.; Stewart, J.A.; Ferré, D.C.; Pérez-Ramírez, J. Role of carbonaceous supports and potassium promoter on higher alcohols synthesis over copper−iron catalysts. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 9604–9618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao, M.; Pham, G.H.; Sunarso, J.; Tade, M.O.; Liu, S. Active centers of catalysts for higher alcohol synthesis from syngas: A review. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 7025–7050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Wang, S.; Wu, Y.; Gao, J.; Bai, Y.; Wang, P.; Xie, H.; Han, Y.; Tan, Y. Cation distribution in Zn-Cr spinel structure and its effects onsynthesis of isobutanol from syngas: Structure–activity relationship. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2015, 404, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.; Yang, G.; Yoneyama, Y.; Kou, Y.; Tan, Y.; Vitidsant, T.; Tsubaki, N. Iso-butanol direct synthesis from syngas over the alkali metals modified Cr/ZnO catalysts. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2015, 505, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Wu, Y.; Yang, G.; Zhang, T.; Li, X.; Xie, H.; Pan, J.; Tan, Y. Insight into the role of hydroxyl groups on the ZnCr catalyst for isobutanol. Appl. Catal. A 2017, 547, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Gao, Z.; Kou, J.; Liu, Y.; Huang, W. Direct synthesis of isobutanol from syngas over nanosized Cu/ZnO/Al2O3 catalysts derived from hydrotalcite-like materials supported on carbon fibers. Energy Fuels 2017, 31, 8572–8579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xie, H.; Gao, X.; Wu, Y.; Wang, P.; Tian, S.; Zhang, T.; Tan, Y. Effects of calcination temperature on structure-activity of K-ZrO2/Cu/Al2O3 catalysts for ethanol and isobutanol synthesis from CO hydrogenation. Fuel 2018, 227, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, J.; Cheng, S.; Gao, Z.; Cheng, F.; Huang, W. Synergistic effects of potassium promoter and carbon fibers on direct synthesis of isobutanol from syngas over Cu/ZnO/Al2O3 catalysts obtained from hydrotalcite-like compounds. Solid State Sci. 2019, 87, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Niu, Y.; Chen, Z. Synthesis of methanol and isobutanol from syngas over ZrO2-based catalysts. Fuel Process. Technol. 1997, 50, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.; Ding, Y.; Luo, H.; Li, C. Effects of zirconia phase on the synthesis of higher alcohols over zirconia and modified zirconia. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2004, 208, 267–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Xie, H.; Tian, S.; Tsubaki, N.; Han, Y.; Tan, Y. Isobutanol synthesis from syngas over K–Cu/ZrO2–La2O3(x) catalysts: Effect of La-loading. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2015, 396, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Tan, Y.; Niu, Y.; Zhong, B.; Peng, S. Relations between ZrO2 crystal structure and its catalytic activity to methanol and isobutanol. J. Fuel Chem. Technol. 1998, 26, 390–394. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes, M.D.; Bell, A.T. The effects of zirconia morphology on methanol synthesis from CO and H2 over Cu/ZrO2 catalysts Part I. Steady-state studies. J. Catal. 2005, 233, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguila, G.; Guerrero, S.; Araya, P. Influence of the crystalline structure of ZrO2 on the activity of Cu/ZrO2 catalysts on the water gas shift reaction. Catal. Commun. 2008, 9, 2550–2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, N.B.; Ekerdt, J.G. Methanol synthesis mechanism over zirconium dioxide. J. Catal. 1986, 101, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Wang, S.; Wu, Y.; Gao, J.; Wang, P.; Xie, H.; Yang, G.; Han, Y.; Tan, Y. The role of potassium promoter in isobutanol synthesis over Zn–Cr based catalysts. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2016, 6, 4105–4115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, S.; Xie, H.; Wang, J.; Tian, S.; Han, Y.; Tan, Y. Influence of Cu on the K-LaZrO2 Catalyst for isobutanol synthesis. Acta Phys.-Chim. Sin. 2015, 31, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmane, V.G.; Adewuyi, Y.G. Synthesis of thermally stable, high surface area, nanocrystalline mesoporous tetragonal zirconium dioxide (ZrO2): Effects of different process parameters. Micropor. Mesopor. Mater. 2012, 148, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atzori, L.; Rombi, E.; Meloni, D.; Sini, M.F.; Monaci, R.; Cutrufello, M.G. CO and CO2 co-methanation on Ni/CeO2-ZrO2 soft-templated catalysts. Catalysts 2019, 9, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimokawabe, M.; Asakawa, H.; Takezawa, N. Characterization of copper zirconia catalysts prepared by an impregnation method. Appl. Catal. 1990, 59, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Yu, T.; Jiang, X.; Chen, F.; Zheng, X. Temperature-programmed reduction and temperature-programmed desorption studies of CuO/ZrO2 catalysts. Appl. Surf. Sci. 1999, 148, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Ruan, C.; Zhan, Y.; Lin, X.; Zheng, Q.; Wei, K. The significant role of oxygen vacancy in Cu/ZrO2 catalyst for enhancing wateregas-shift performance. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, J.; Sakata, Y.; Domen, K.; Maruya, K.; Onishi, T. Infrared study of hydrogen adsorbed on ZrO2. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 1990, 86, 397–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Shi, H.; Xu, B. Vital roles of hydroxyl groups and gold oxidation states in Au/ZrO2 catalysts for 1,3-butadiene hydrogenation. J. Catal. 2011, 279, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graf, P.O.; de Vlieger, D.J.M.; Mojet, B.L.; Lefferts, L. New insights in reactivity of hydroxyl groups in water gas shift reaction on Pt/ZrO2. J. Catal. 2009, 262, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karwacki, C.J.; Ganesh, P.; Kent, P.R.C.; Gordon, W.O.; Peterson, G.W.; Niu, J.J.; Gogotsi, Y. Structure-activity relationship of Au/ZrO2 catalyst on formation of hydroxyl groups and its influence on CO oxidation. J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 1, 6051–6062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, D.; Gass, J.L.; Khalfallah, M.; Teichner, S.J. Intermediate species on zirconia supported methanol aerogel catalysts. 1. State of the catalyst surface before and after the adsorption of hydrogen. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 1993, 101, 297–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binet, C.; Daturi, M.; Lavalley, J.C. IR study of polycrystalline ceria properties in oxidised and reduced states. Catal. Today 1999, 50, 207–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köck, E.M.; Kogler, M.; Bielz, T.; Klötzer, B.; Penner, S. In situ FT-IR spectroscopic study of CO2 and CO adsorption on Y2O3, ZrO2, and Yttria-stabilized ZrO2. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 17666–17673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Q. Hydroconversion of C18 fatty acids using PtNi/Al2O3: Insight in the role of hydroxyl groups in Al2O3. Catal. Commun. 2017, 97, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namiki, T.; Yamashita, S.; Tominaga, H.; Nagai, M. Dissociation of CO and H2O during water–gas shift reaction on carburized Mo/Al2O3 catalyst. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2011, 398, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Shi, H.; Kwak, J.H.; Szanyi, J. Mechanism of CO2 Hydrogenation on Pd/Al2O3 catalysts: Kinetics and transient DRIFTS-MS studies. ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 6337–6349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiroz, J.; Giraudon, J.M.; Gervasini, A.; Dujardin, C.; Lancelot, C.; Trentesaux, M.; Lamonier, J.F. Total oxidation of formaldehyde over MnOx-CeO2 catalysts: The effect of acid treatment. ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 2260–2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wu, Y.; Gao, X.; Xie, H.; Yang, G.; Tsubaki, N.; Tan, Y. Effects of surface hydroxyl groups induced by the co-precipitation temperature on the catalytic performance of direct synthesis of isobutanol from syngas. Fuel 2019, 237, 1021–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, B.; Tsubaki, N. In-situ DRIFT study of a low-temperature methanol synthesis mechanism on Cu/ZnO catalysts from CO2-containing syngas using ethanol promoter. J. Catal. 2004, 228, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, J.; Frenzel, J.; Meyer, B.; Marx, D. Methanol synthesis on ZnO(0001). II. Structure, energetics, and vibrational signature of reaction intermediates. J. Chem. Phys. 2013, 139, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Escribano, V.; Larrubia Vargas, M.A.; Finocchio, E.; Busca, G. On the mechanisms and the selectivity determining steps in syngas conversion over supported metal catalysts: An IR study. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2007, 316, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Liu, C.W.; Pan, W.; Zhu, Q.M.; Deng, J.F. In situ IR studies on the mechanism of methanol synthesis over an ultrafine Cu/ZnO/Al2O3 catalyst. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 1998, 171, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltier, F.L.; Chaumette, P.; Saussey, J.; Bettaha, M.M.; Lavalley, J.C. In-situ FT-IR spectroscopy and kinetic study of methanol synthesis from CO/H2 over ZnAl2O4 and Cu-ZnAl2O4 catalysts. J. Mol. Catal. A 1997, 122, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Gong, N.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, J.; Wang, L.; Xie, H.; Tan, Y. Insight into the branched alcohols formation mechanism on KZnCr catalysts from syngas. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2019, 9, 2592–2600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, T.; Sun, K.; Wang, L.; Xie, H.; Tan, Y. Effect of potassium on the regulation of C1 intermediates in isobutyl alcohol synthesis from syngas over CuLaZrO2 catalysts. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2019, 58, 9343–9351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Catalyst | T (°C) | P (MPa) | CO/H2 | GHSV (h−1) | Isobutanol (wt%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K-Zn1Cr1 [6] | 400 | 10 | 2.5 | 3000 | 15.99 |

| Cr/ZnO-K [7] | 400 | 10 | 2.3 | 3000 | 15.58 |

| K-Zn1Cr1 (pH = 2) [8] | 400 | 10 | 2.5 | 3000 | 24.2 |

| Cu/ZnO/Al2O3/30% ACFs [9] | 320 | 4 | 2 | 3900 | 19.88 |

| K-CuZrAl [10] | 400 | 10 | 2.7 | 5000 | 17.7 |

| K-ZrO2 [12] | 420 | 10 | 2.1 | 5000 | 15.1 |

| Li-Pd-ZrO2 [13] | 400 | 8 | 2 | 15,000 | 23.1 |

| K-CuLaZrO2 [14] | 360 | 10 | 2.5 | 3000 | 32.8 |

| Catalysts | CO Conv. (%) | Alc. STY (g·L−1·h−1) | Selectivity (C-atom%) | Alc. Distribution (wt%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alc. | CHx | CO2 | DME | C1 | C2 | C3 | i-C4 | C4+ | |||

| E-ZrO2 | 10.9 | 34 | 14.5 | 84.9 | 0 | 0.6 | 94.6 | 4.2 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0 |

| E-KCZ | 37.7 | 144 | 25.5 | 37.9 | 33.5 | 3.1 | 90.0 | 3.6 | 1.5 | 4.7 | 0.2 |

| E-KCZ a | 14.5 | 284 | 40.1 | 29.7 | 28.7 | 1.5 | 92.9 | 2.8 | 1.0 | 3.2 | 0.1 |

| A-ZrO2 | 13.2 | 24 | 19.6 | 79.8 | 0 | 0.6 | 97.2 | 1.6 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 0 |

| A-KCZ | 41.2 | 195 | 42.3 | 31.1 | 25.4 | 1.2 | 78.8 | 2.7 | 2.1 | 15.0 | 1.4 |

| A-KCZ a | 16.8 | 315 | 56.2 | 24.6 | 18.2 | 1.0 | 86.0 | 2.2 | 0.9 | 10.2 | 0.7 |

| Catalysts | Pore Diameter, nm | Pore Volume, cm3g−1 | ABET, m2g−1 | SCu (m2/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E-ZrO2 a | 5.80 | 0.62 | 424.66 | - |

| A-ZrO2 a | 9.10 | 0.71 | 309.87 | - |

| E-KCZ a | 6.91 | 0.55 | 315.69 | 11.6 |

| A-KCZ a | 9.66 | 0.59 | 243.59 | 11.3 |

| E-ZrO2 b | 5.65 | 0.63 | 430.85 | - |

| A-ZrO2 b | 9.01 | 0.77 | 313.54 | - |

| E-KCZ b | 6.88 | 0.55 | 320.80 | - |

| A-KCZ b | 9.89 | 0.68 | 273.24 | - |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, Y.; Tan, L.; Zhang, T.; Xie, H.; Yang, G.; Tsubaki, N.; Chen, J. Effect of Preparation Method on ZrO2-Based Catalysts Performance for Isobutanol Synthesis from Syngas. Catalysts 2019, 9, 752. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal9090752

Wu Y, Tan L, Zhang T, Xie H, Yang G, Tsubaki N, Chen J. Effect of Preparation Method on ZrO2-Based Catalysts Performance for Isobutanol Synthesis from Syngas. Catalysts. 2019; 9(9):752. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal9090752

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Yingquan, Li Tan, Tao Zhang, Hongjuan Xie, Guohui Yang, Noritatsu Tsubaki, and Jiangang Chen. 2019. "Effect of Preparation Method on ZrO2-Based Catalysts Performance for Isobutanol Synthesis from Syngas" Catalysts 9, no. 9: 752. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal9090752