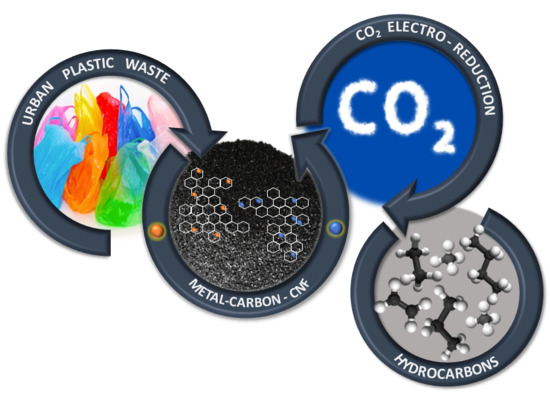

Metal-Carbon-CNF Composites Obtained by Catalytic Pyrolysis of Urban Plastic Residues as Electro-Catalysts for the Reduction of CO2

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

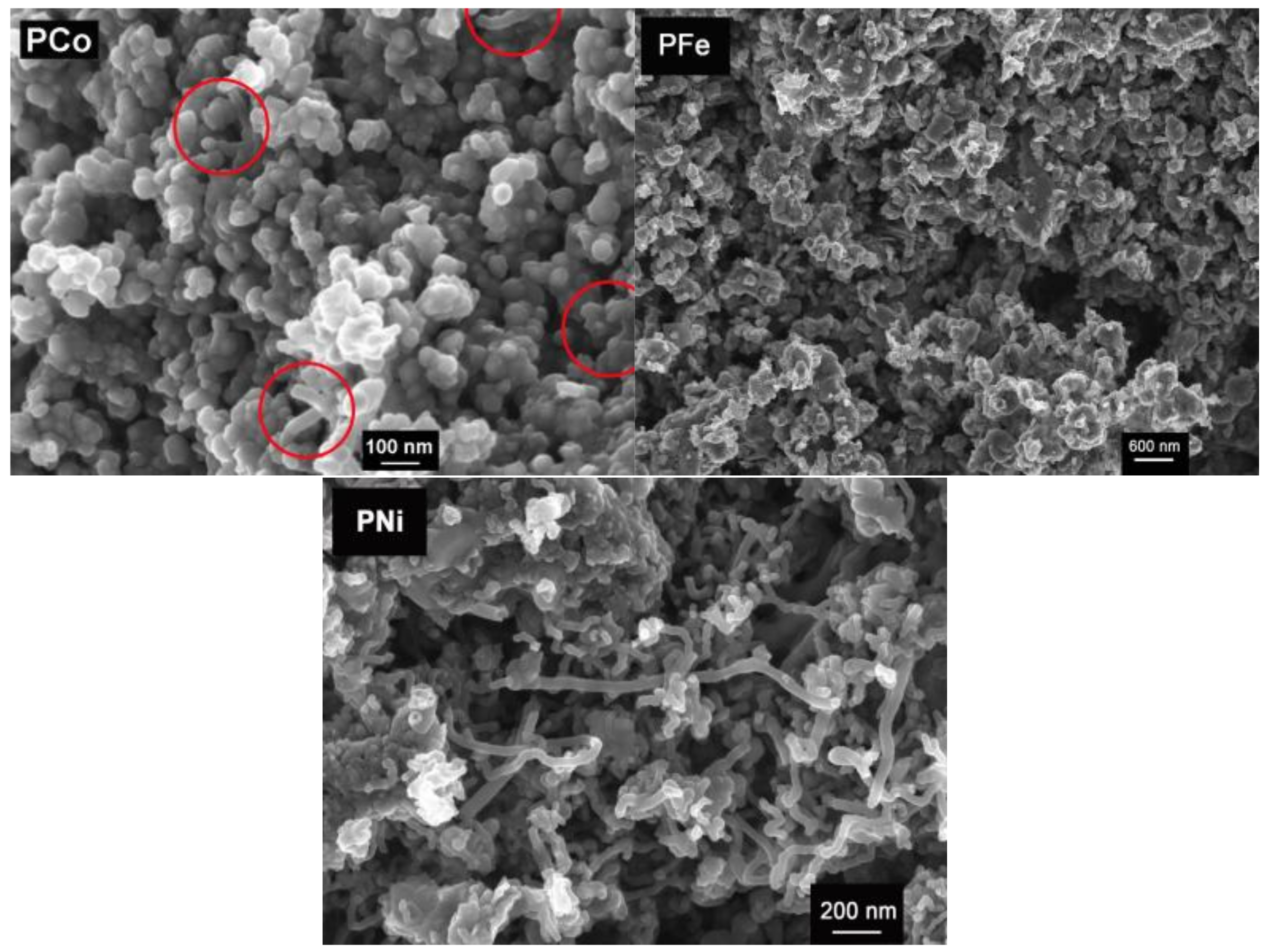

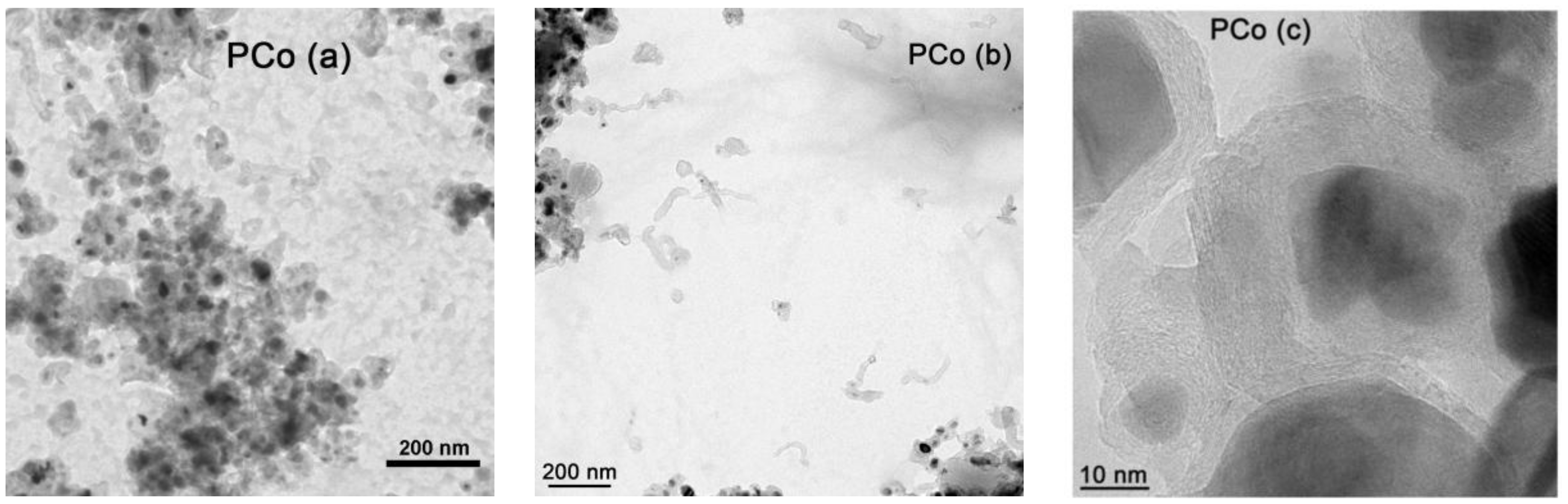

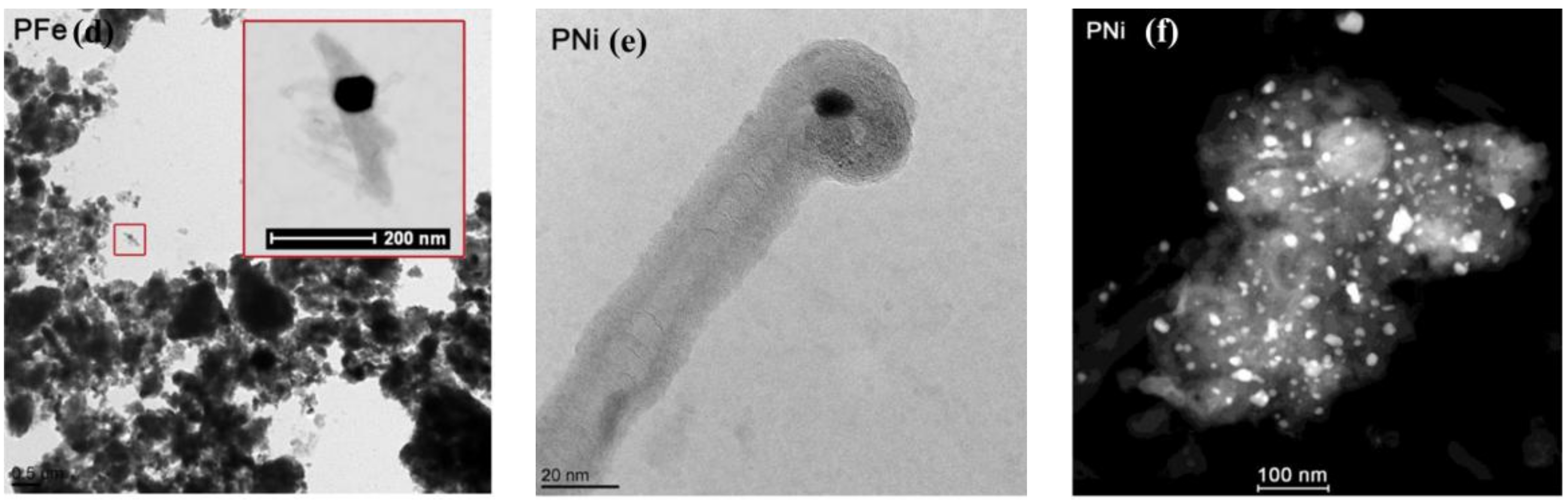

2.1. Textural and Chemical Characterization of the Composites

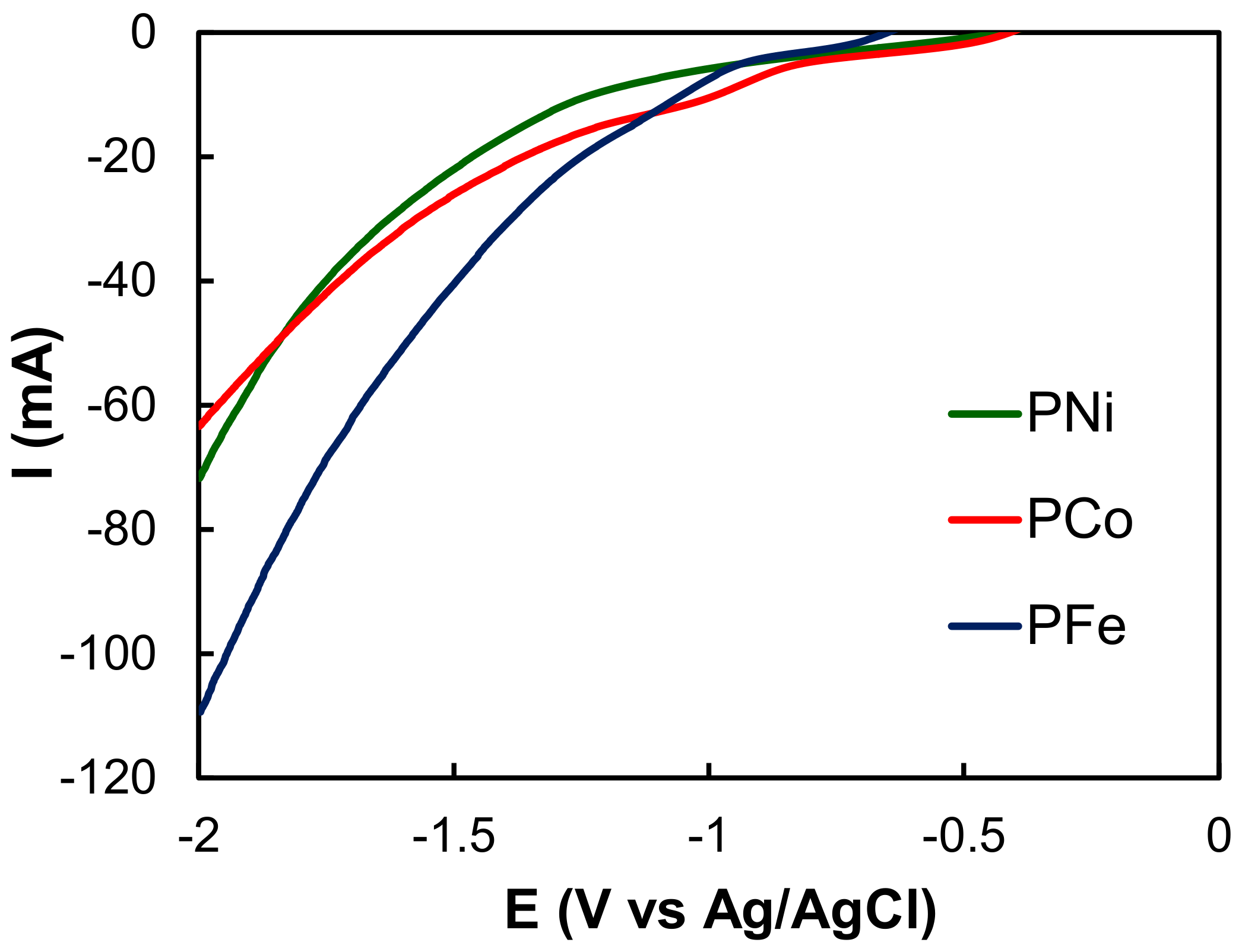

2.2. Electro-Reduction of CO2

3. Materials and Methods

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Meteorological Organization. Available online: http://www.wmo.int/ (accessed on 1 May 2018).

- Centi, G.; Perathoner, S. Opportunities and prospects in the chemical recycling of carbon dioxide to fuels. Catal. Today 2009, 148, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, K. The origin, development, and future of the lithium-ion battery. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2012, 16, 2017–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bevilacqua, M.; Filippi, J.; Miller, H.A.; Vizza, F. Recent technological progress in CO2 electroreduction to fuels and energy carriers in aqueous environments. Energy Technol. 2015, 3, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hori, Y.; Murata, A. Electrochemical evidence of intermediate formation of adsorbed CO in cathodic reduction of CO2 at a nickel electrode. Electrochim. Acta 1990, 35, 1777–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hori, Y.; Murata, A.; Takahashi, R. Formation of hydrocarbons in the electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide at a copper electrode in aqueous solution. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 1989, 85, 2309–2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hori, Y.; Wakebe, H.; Tsukamoto, T.; Koga, O. Electrocatalytic process of CO selectivity in electrochemical reduction of CO2 at metal electrodes in aqueous media. Electrochim. Acta 1994, 39, 1833–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jitaru, M.; Lowy, D.A.; Toma, M.; Toma, B.C.; Oniciu, L. Electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide on flat metallic cathodes. J. Appl. Electrochem. 1997, 27, 875–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gattrell, M.; Gupta, N.; Co, A. A review of the aqueous electrochemical reduction of CO2 to hydrocarbons at copper. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2006, 594, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaplin, R.P.S.; Wragg, A.A. Effects of process conditions and electrode material on reaction pathways for carbon dioxide electroreduction with particular reference to formate formation. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2003, 33, 1107–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Lv, W.; Li, G.; Lei, L. Electrochemical reduction of CO2 on SnO2/nitrogen-doped multiwalled carbon nanotubes composites in KHCO3 aqueous solution. Mater. Lett. 2015, 141, 63–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Chen, L.; Knowles, G.P.; MacFarlane, D.R.; Zhang, J. Hierarchical Mesoporous SnO2 Nanosheets on Carbon Cloth: A Robust and Flexible Electrocatalyst for CO2 Reduction with High Efficiency and Selectivity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 505–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bashir, S.; Hossain, S.; Rahman, S.u.; Ahmed, S.; Amir, A.; Hossain, M.M. Electrocatalytic reduction of carbon dioxide on SnO2/MWCNT in aqueous electrolyte solution. J. CO2 Util. 2016, 16, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.D.; Liu, J.L.; Qiao, S.Z. Recent Advances in Inorganic Heterogeneous Electrocatalysts for Reduction of Carbon Dioxide. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 3423–3452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centi, G.; Perathoner, S.; Wine, G.; Gangeri, M. Electrocatalytic conversion of CO2 to long carbon-chain hydrocarbons. Green Chem. 2007, 9, 671–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centi, G.; Perathoner, S. Problems and perspectives in nanostructured carbon-based electrodes for clean and sustainable energy. Catal. Today 2010, 150, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Seredych, M.; Rodriguez-Castellon, E.; Bandosz, T.J. Metal-free nanoporous carbon as a catalyst for electrochemical reduction of CO2 to CO and CH4. ChemSusChem 2016, 9, 606–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez-Cadenas, A.F. Doped Carbon Material for the Electrocatalytic Conversion of CO2 into Hydrocarbons, Uses of the Material and Conversion Method Using Said Material. Patent WO/2013/004882, 1 October 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Cadenas, A.F.; Ros, C.H.; Morales-Torres, S.; Perez-Cadenas, M.; Kooyman, P.J.; Moreno-Castilla, C.; Kapteijn, F. Metal-doped carbon xerogels for the electro-catalytic conversion of CO2 to hydrocarbons. Carbon 2013, 56, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schouten, K.J.P.; Kwon, Y.; van der Ham, C.J.M.; Qin, Z.; Koper, M.T.M. A new mechanism for the selectivity to C1 and C2 species in the electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide on copper electrodes. Chem. Sci. 2011, 2, 1902–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, J.; Liu, Y.; Hong, F.; Zhang, J. A review of catalysts for the electroreduction of carbon dioxide to produce low-carbon fuels. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 631–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelwahab, A.; Castelo-Quibén, J.; Pérez-Cadenas, M.; Elmouwahidi, A.; Maldonado-Hódar, F.J.; Carrasco-Marín, F.; Pérez-Cadenas, A.F. Cobalt-doped carbon gels as electro-catalysts for the reduction of CO2 to hydrocarbons. Catalysts 2017, 7, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelo-Quiben, J.; Abdelwahab, A.; Perez-Cadenas, M.; Morales-Torres, S.; Maldonado-Hodar, F.J.; Carrasco-Marin, F.; Perez-Cadenas, A.F. Carbon-iron electro-catalysts for CO2 reduction. The role of the iron particle size. J. CO2 Util. 2018, 24, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keane, M.A. Catalytic Transformation of Waste Polymers to Fuel Oil. ChemSusChem 2009, 2, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguado, J.; Serrano, D.P.; San Miguel, G.; Castro, M.C.; Madrid, S. Feedstock recycling of polyethylene in a two-step thermo-catalytic reaction system. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 2007, 79, 415–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quicker, P. Thermal Treatment as a Chance for Material Recovery. In Source Separation and Recycling: Implementation and Benefits for a Circular Economy; Maletz, R., Dornack, C., Ziyang, L., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 119–149. [Google Scholar]

- Bazargan, A.; McKay, G. A review—Synthesis of carbon nanotubes from plastic wastes. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 195, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huerta-Pujol, O.; Soliva, M.; Giró, F.; López, M. Heavy metal content in rubbish bags used for separate collection of biowaste. Waste Manag. 2010, 30, 1450–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, K.; Yang, Q.; Li, G.; Sun, Y.; Feng, D. Morphology and mechanical properties of polypropylene/calcium carbonate nanocomposites. Mater. Lett. 2006, 60, 805–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado-Hodar, F.J.; Moreno-Castilla, C.; Rivera-Utrilla, J.; Hanzawa, Y.; Yamada, Y. Catalytic graphitization of carbon aerogels by transition metals. Langmuir 2000, 16, 4367–4373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado-Hodar, F.J.; Moreno-Castilla, C.; Perez-Cadenas, A.F. Surface morphology, metal dispersion, and pore texture of transition metal-doped monolithic carbon aerogels and steam-activated derivatives. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2004, 69, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncalves, M.R.; Gomes, A.; Condeco, J.; Fernandes, R.; Pardal, T.; Sequeira, C.A.C.; Branco, J.B. Selective electrochemical conversion of CO2 to C2 hydrocarbons. Energy Convers. Manag. 2010, 51, 30–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

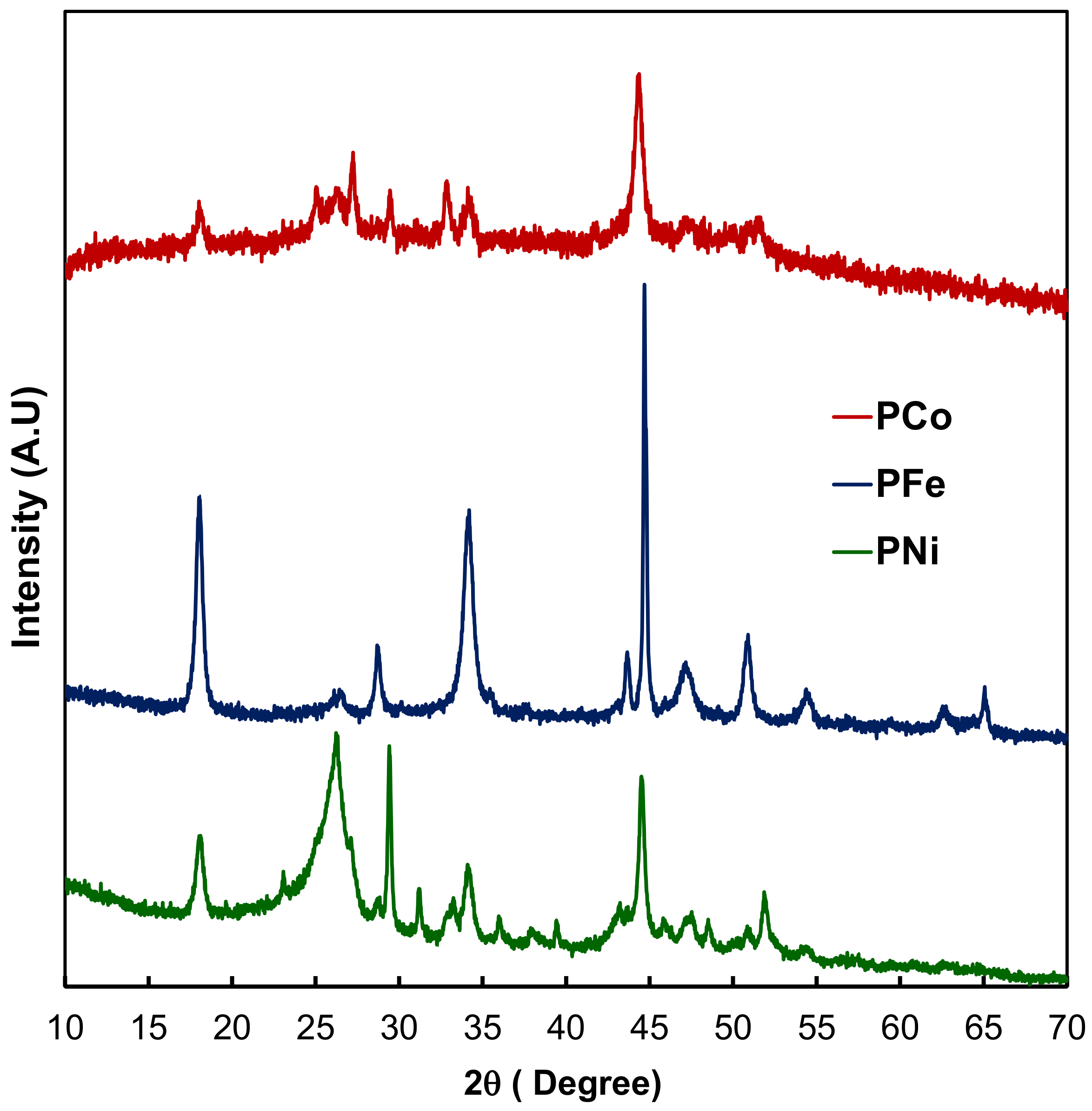

| Sample | SBET (m2 g−1) | W0 (cm3 g−1) | L0 (nm) | V0.95 (cm3 g−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFe | 44 | 0.01 | 2.08 | 0.100 |

| PCo | 80 | 0.02 | 2.16 | 0.189 |

| PNi | 44 | 0.01 | 2.18 | 0.149 |

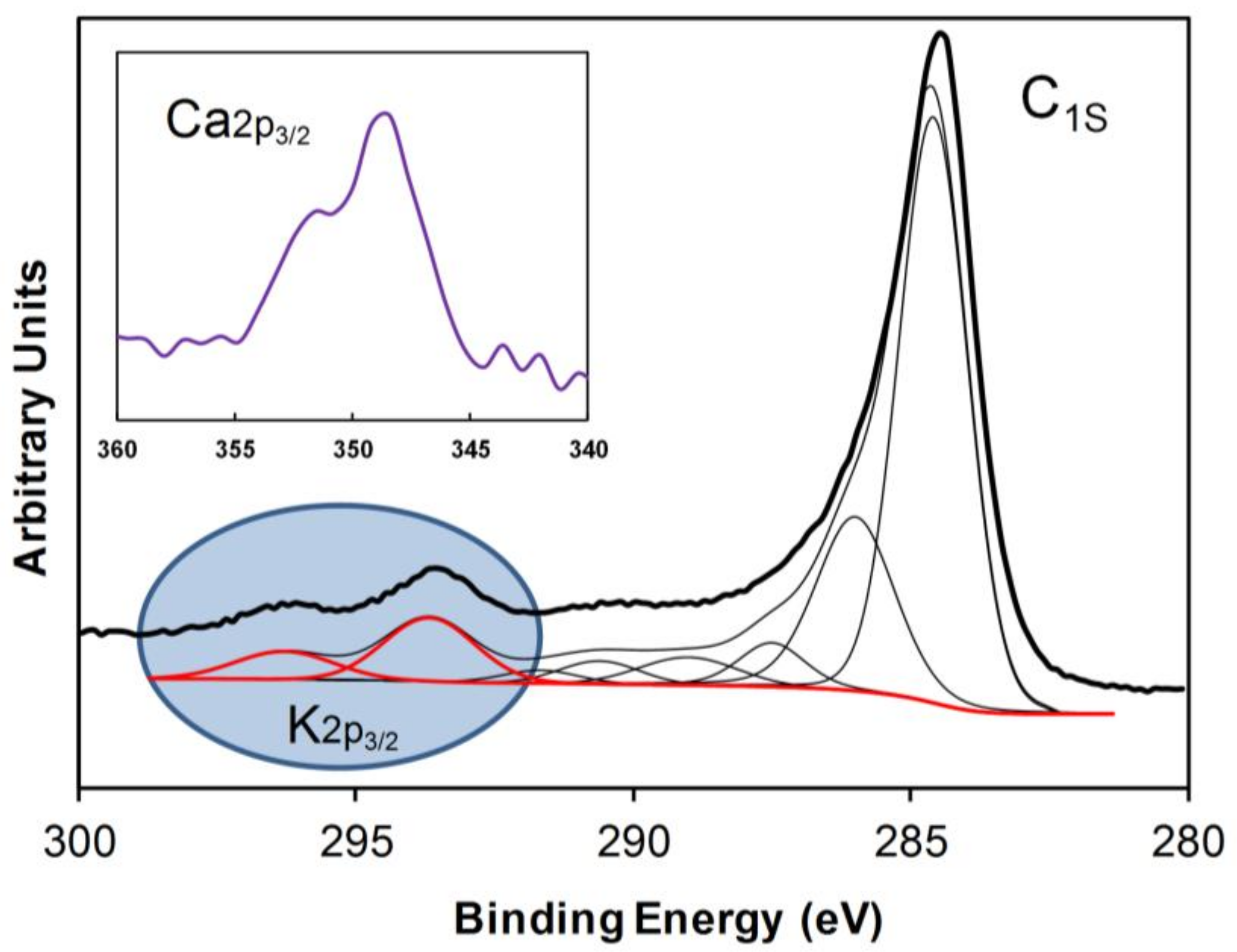

| Sample | CaICP (wt. %) | CoICP (wt. %) | FeICP (wt. %) | KICP(wt. %) | NiICP(wt. %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCo | 2.31 | 9.93 | 0.36 | 2.56 | 0.12 |

| PFe | 3.75 | 0.07 | 15.92 | 4.68 | 0.43 |

| PNi | 1.56 | 0.02 | 0.29 | 2.02 | 6.52 |

| Sample | C (wt. %) | O (wt. %) | K (wt. %) | Ca (wt. %) | Co (wt. %) | Fe (wt. %) | Ni (wt. %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCo | 87.71 | 6.93 | 2.05 | 2.97 | 0.34 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| PFe | 82.21 | 8.53 | 5.35 | 3.81 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.00 |

| PNi | 89.84 | 4.12 | 3.91 | 1.98 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.15 |

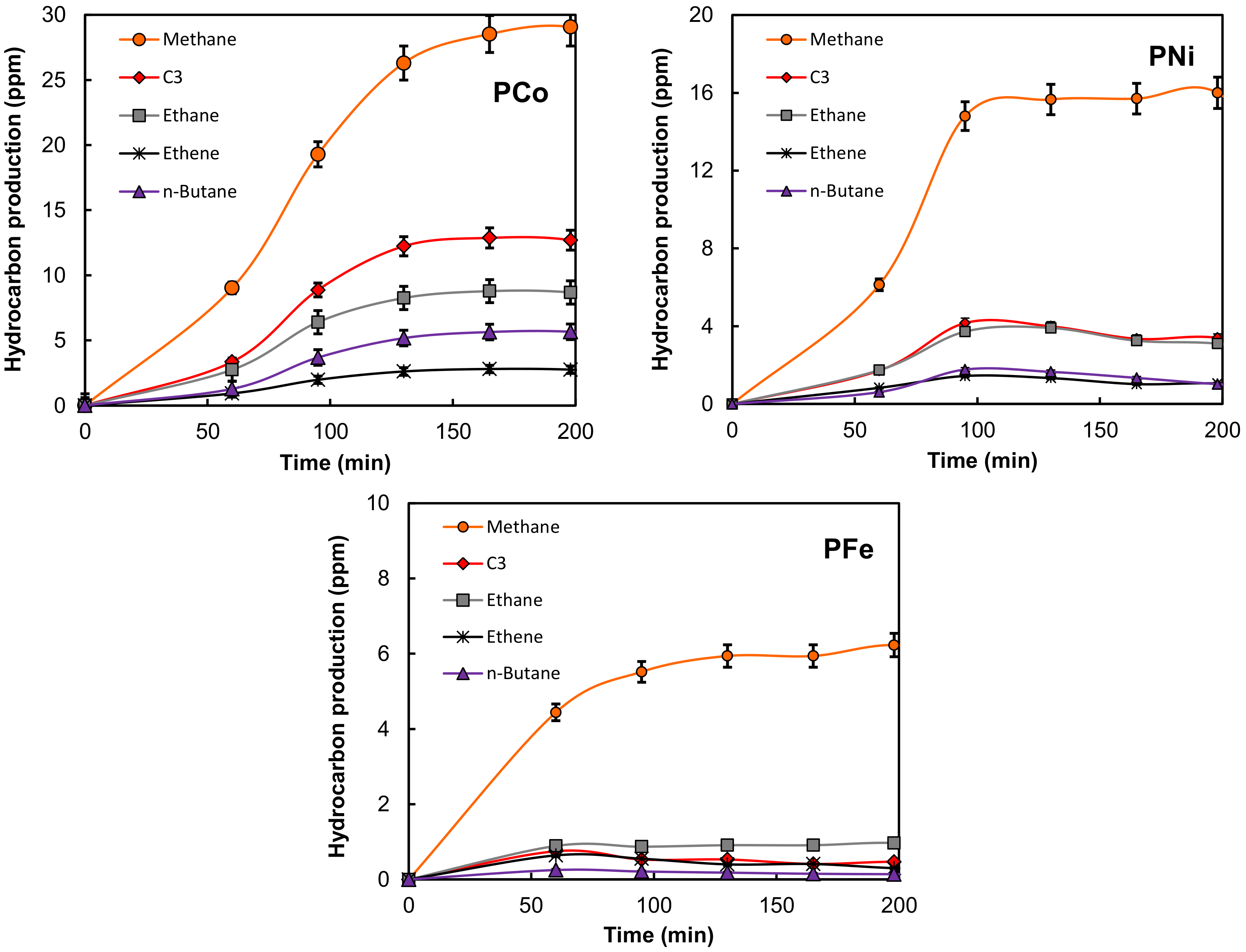

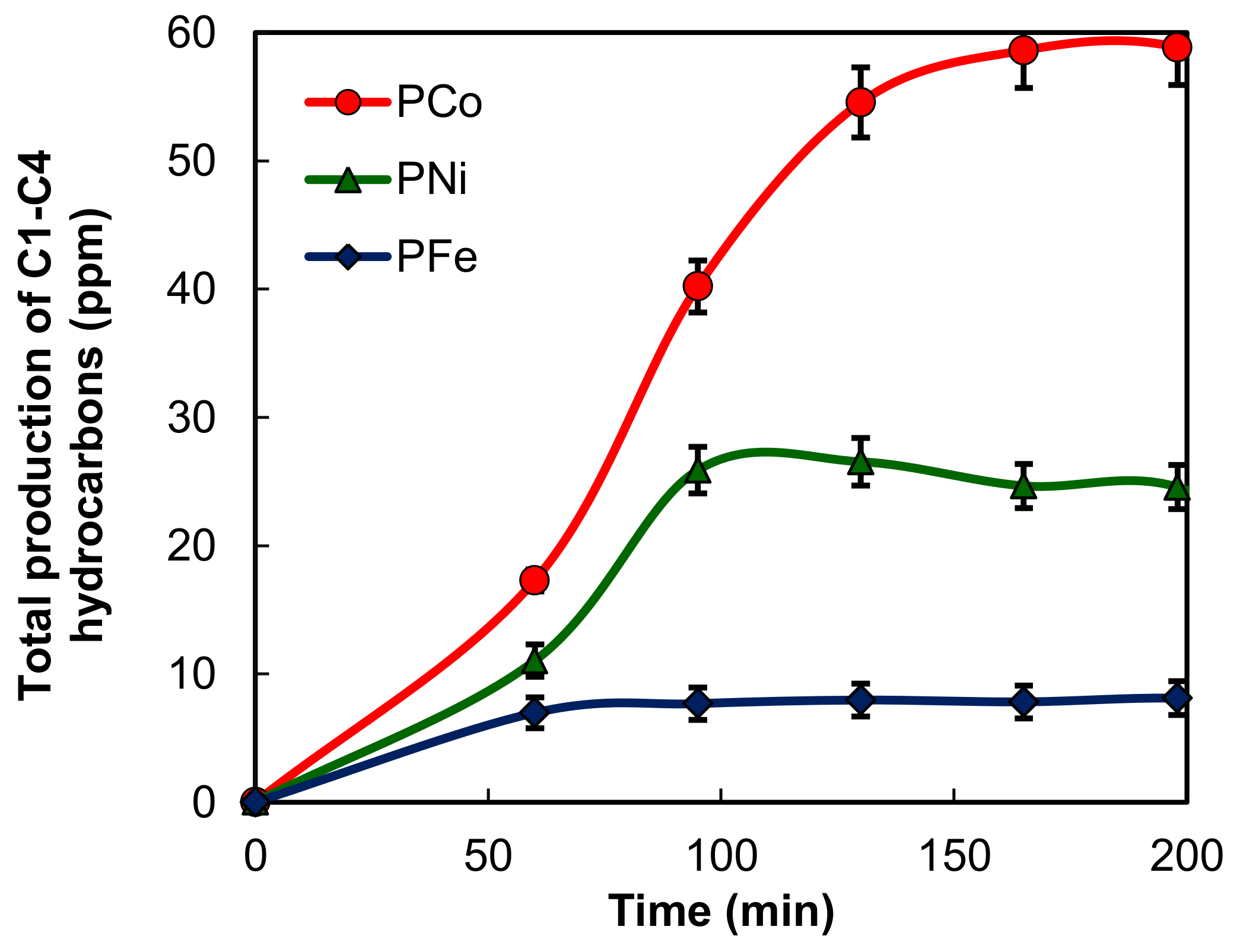

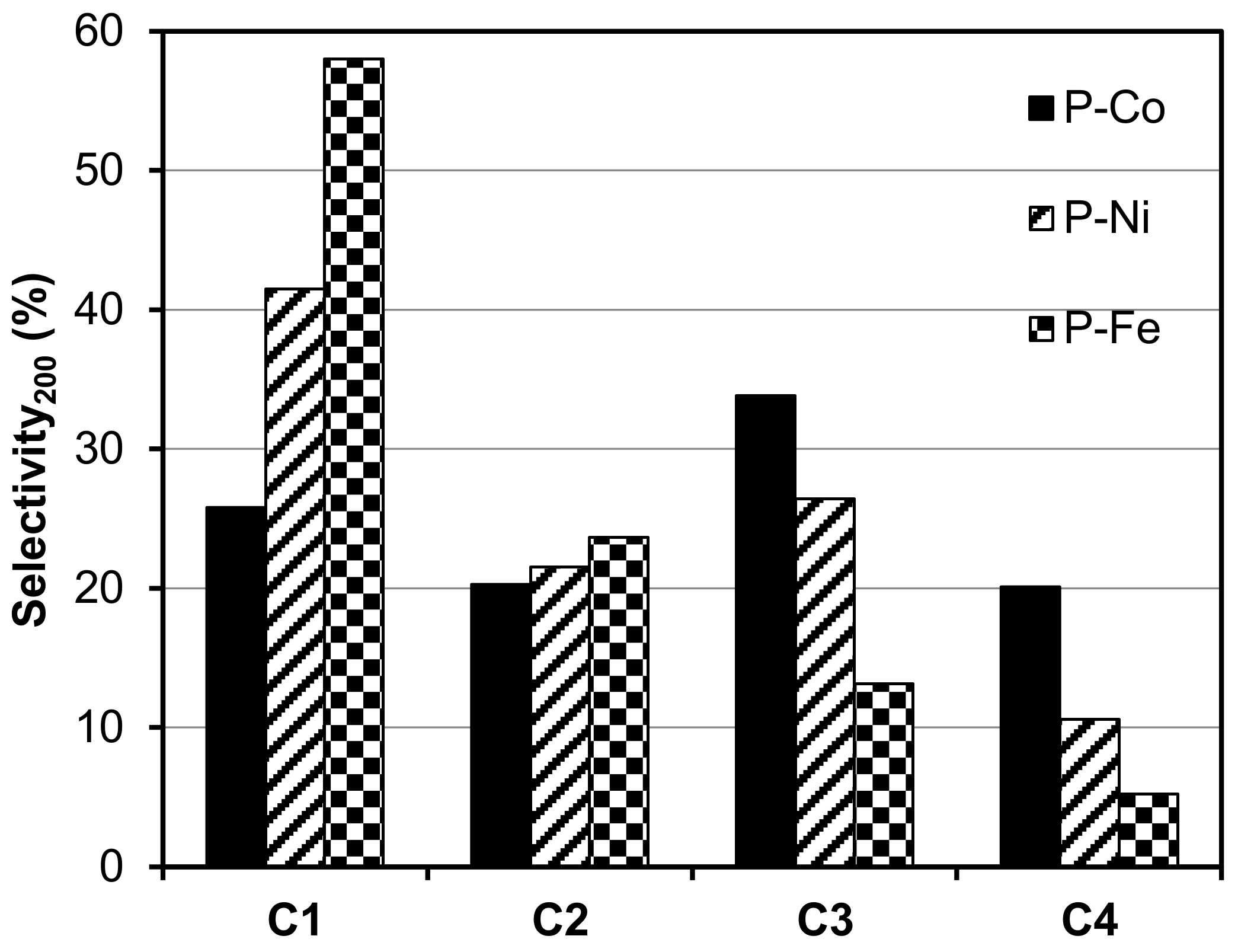

| Composite | dXRD * (nm) | F.E. (%) |

|---|---|---|

| PCo | 13.6 | 0.46 |

| PNi | 20.7 | 0.40 |

| PFe | 39.4 | 0.06 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Castelo-Quibén, J.; Elmouwahidi, A.; Maldonado-Hódar, F.J.; Carrasco-Marín, F.; Pérez-Cadenas, A.F. Metal-Carbon-CNF Composites Obtained by Catalytic Pyrolysis of Urban Plastic Residues as Electro-Catalysts for the Reduction of CO2. Catalysts 2018, 8, 198. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal8050198

Castelo-Quibén J, Elmouwahidi A, Maldonado-Hódar FJ, Carrasco-Marín F, Pérez-Cadenas AF. Metal-Carbon-CNF Composites Obtained by Catalytic Pyrolysis of Urban Plastic Residues as Electro-Catalysts for the Reduction of CO2. Catalysts. 2018; 8(5):198. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal8050198

Chicago/Turabian StyleCastelo-Quibén, Jesica, Abdelhakim Elmouwahidi, Francisco J. Maldonado-Hódar, Francisco Carrasco-Marín, and Agustín F. Pérez-Cadenas. 2018. "Metal-Carbon-CNF Composites Obtained by Catalytic Pyrolysis of Urban Plastic Residues as Electro-Catalysts for the Reduction of CO2" Catalysts 8, no. 5: 198. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal8050198

APA StyleCastelo-Quibén, J., Elmouwahidi, A., Maldonado-Hódar, F. J., Carrasco-Marín, F., & Pérez-Cadenas, A. F. (2018). Metal-Carbon-CNF Composites Obtained by Catalytic Pyrolysis of Urban Plastic Residues as Electro-Catalysts for the Reduction of CO2. Catalysts, 8(5), 198. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal8050198