Isomerization Behavior Comparison of Single Hydrocarbon and Mixed Light Hydrocarbons over Super-Solid Acid Catalyst Pt/SO42−/ZrO2/Al2O3

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

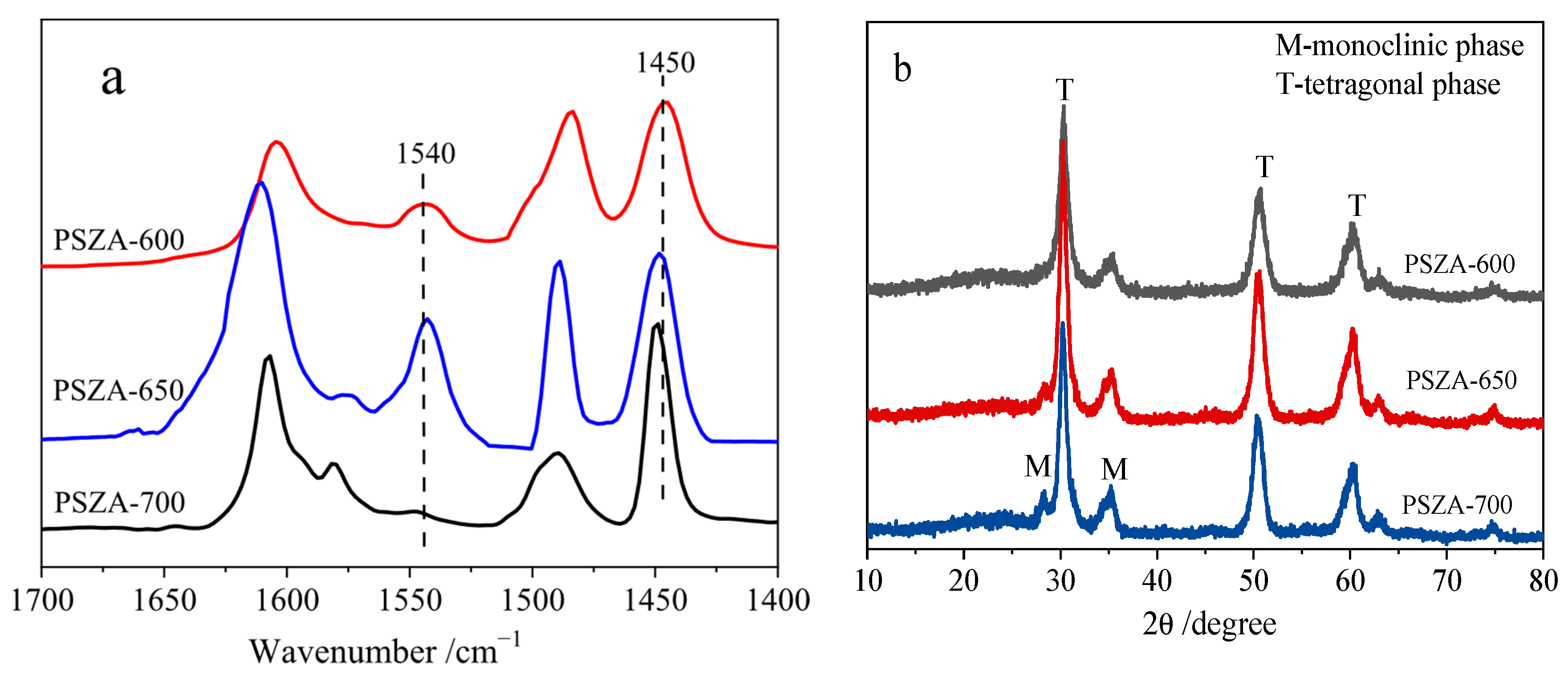

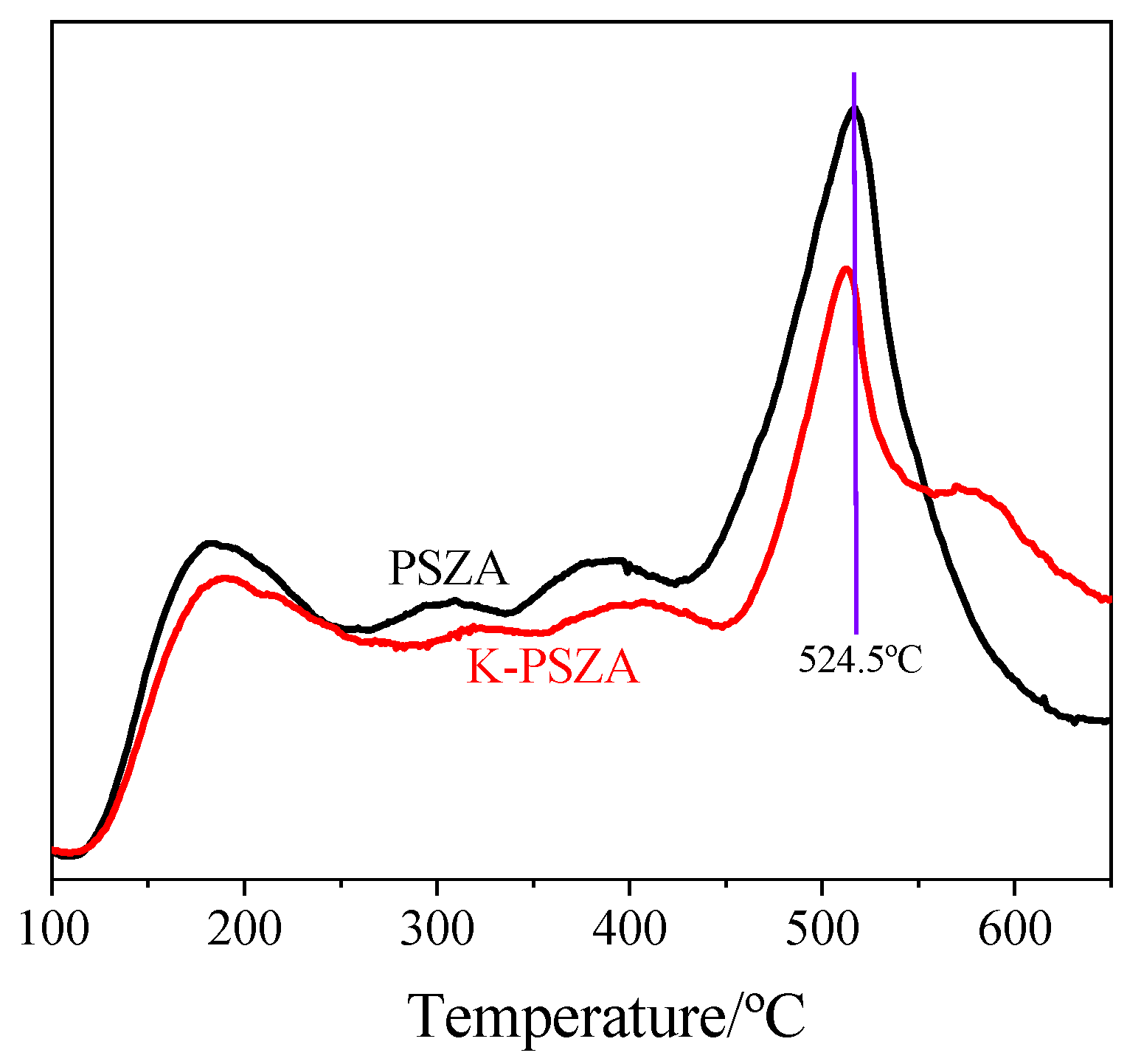

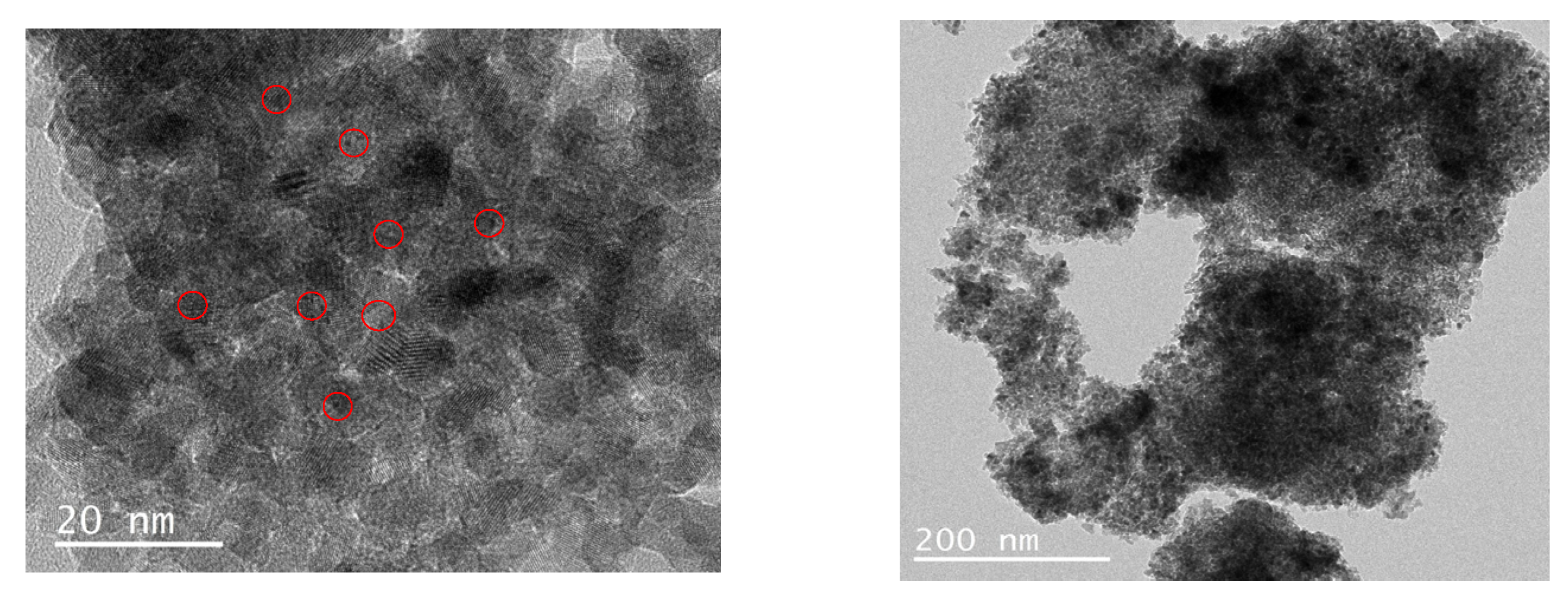

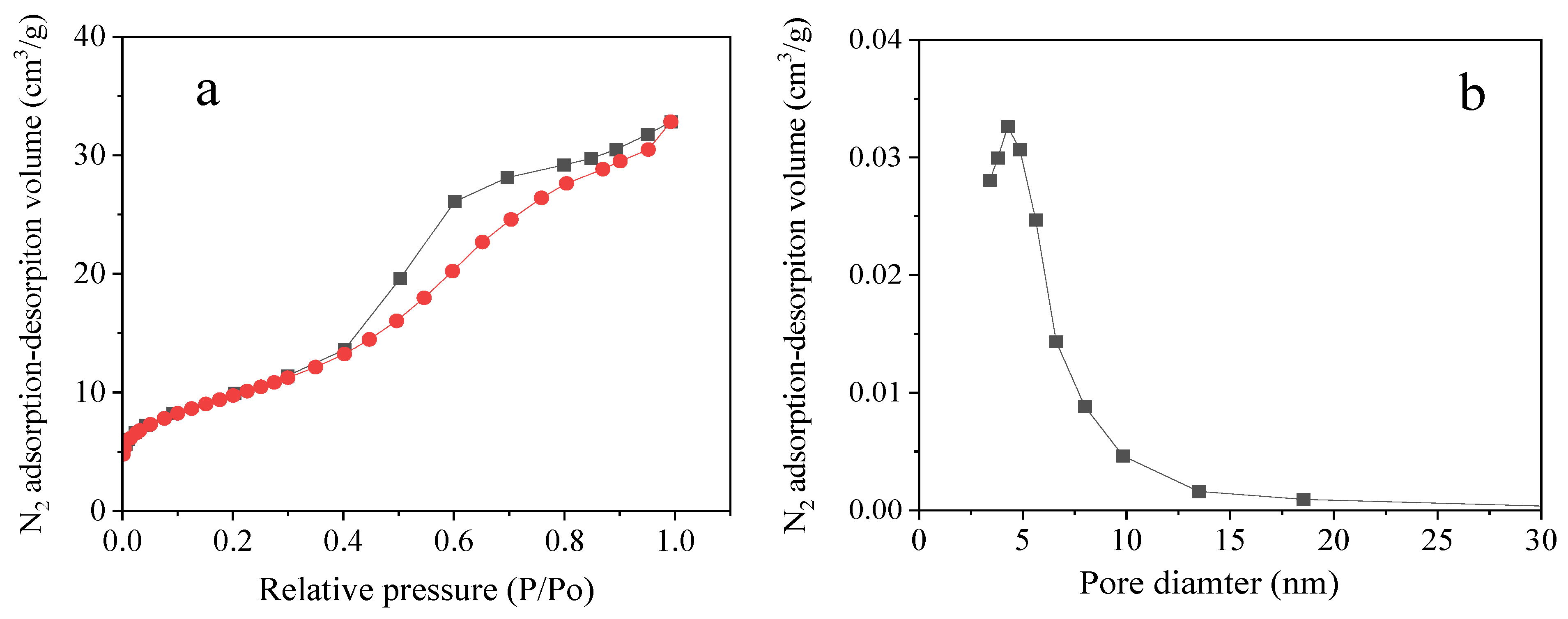

2.1. Catalyst Properties

2.2. Isomerization Behavior of Different Feeds over PSZA in Continuous Reactions

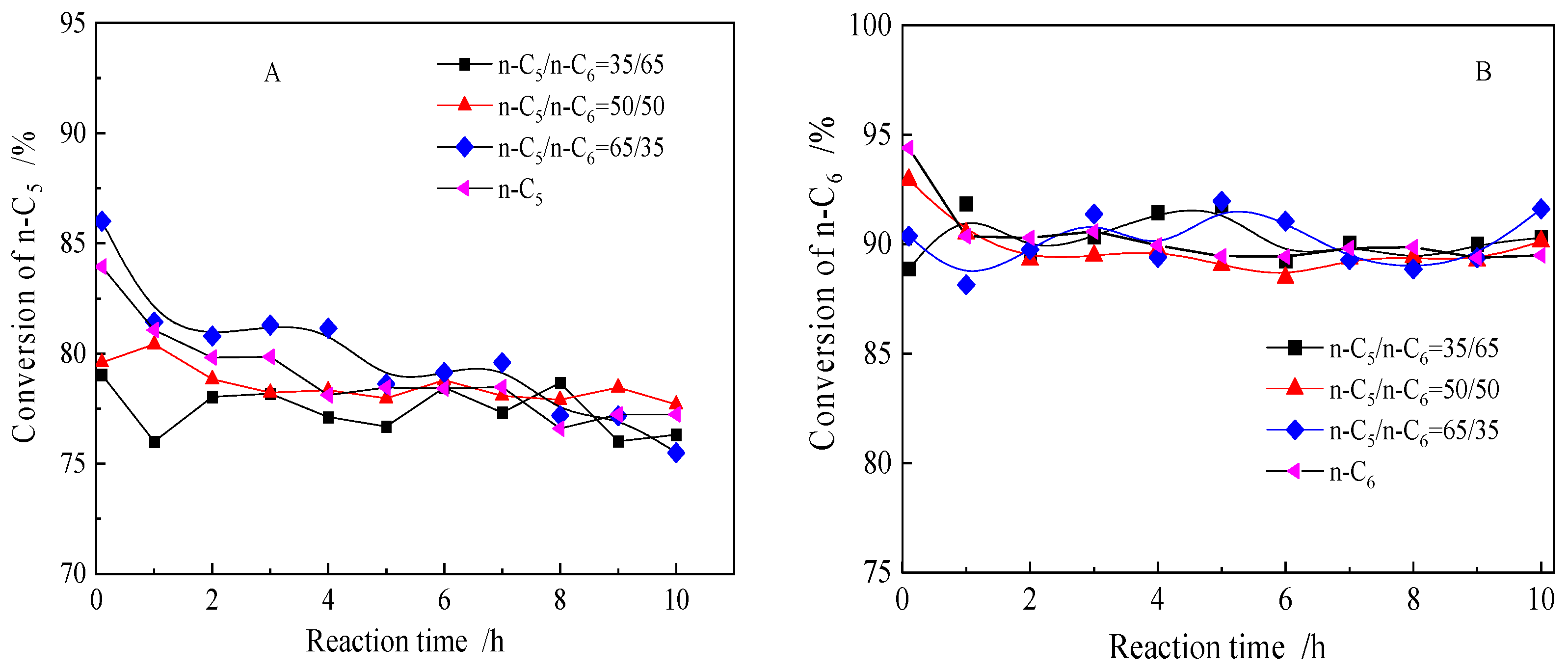

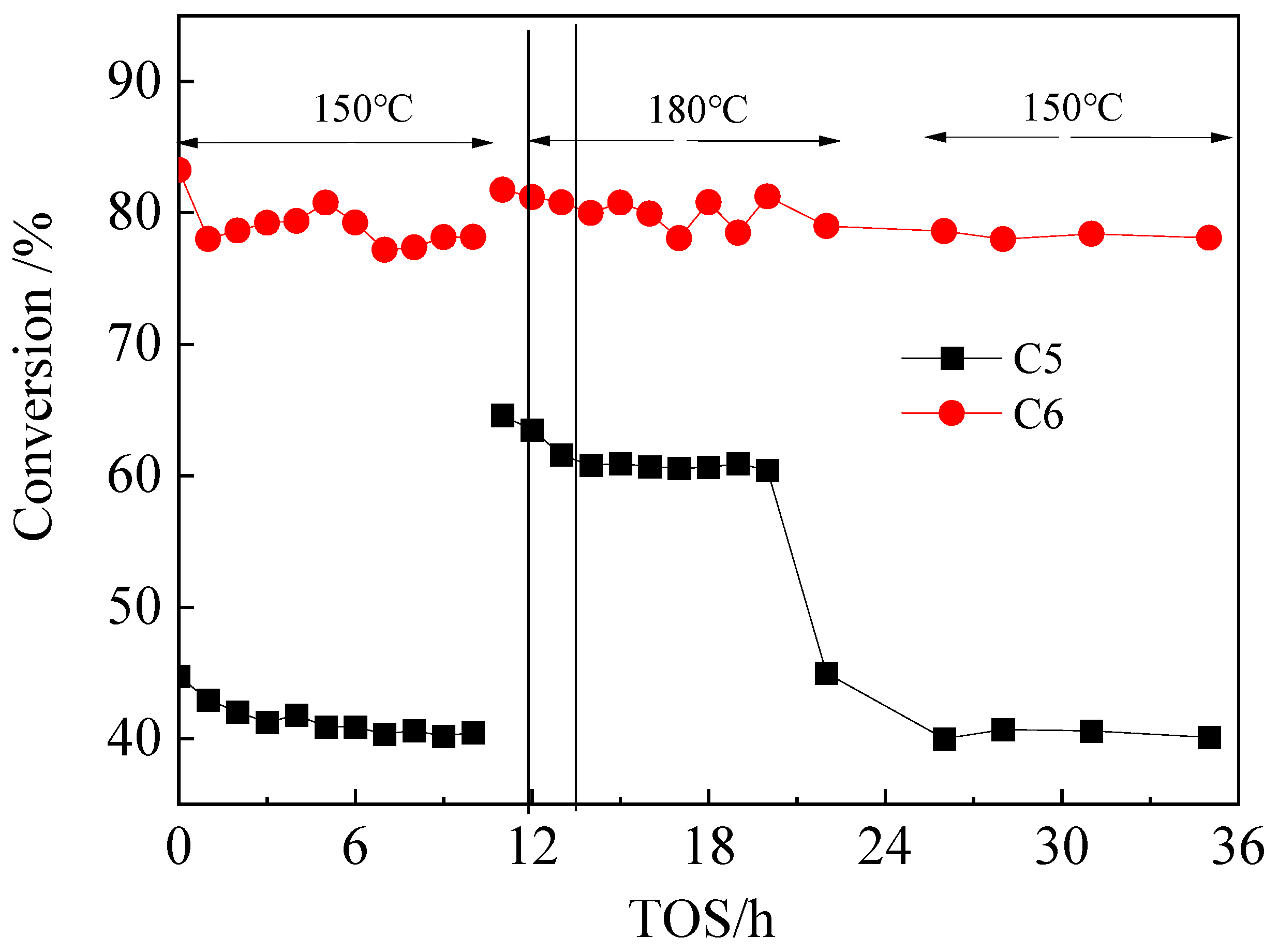

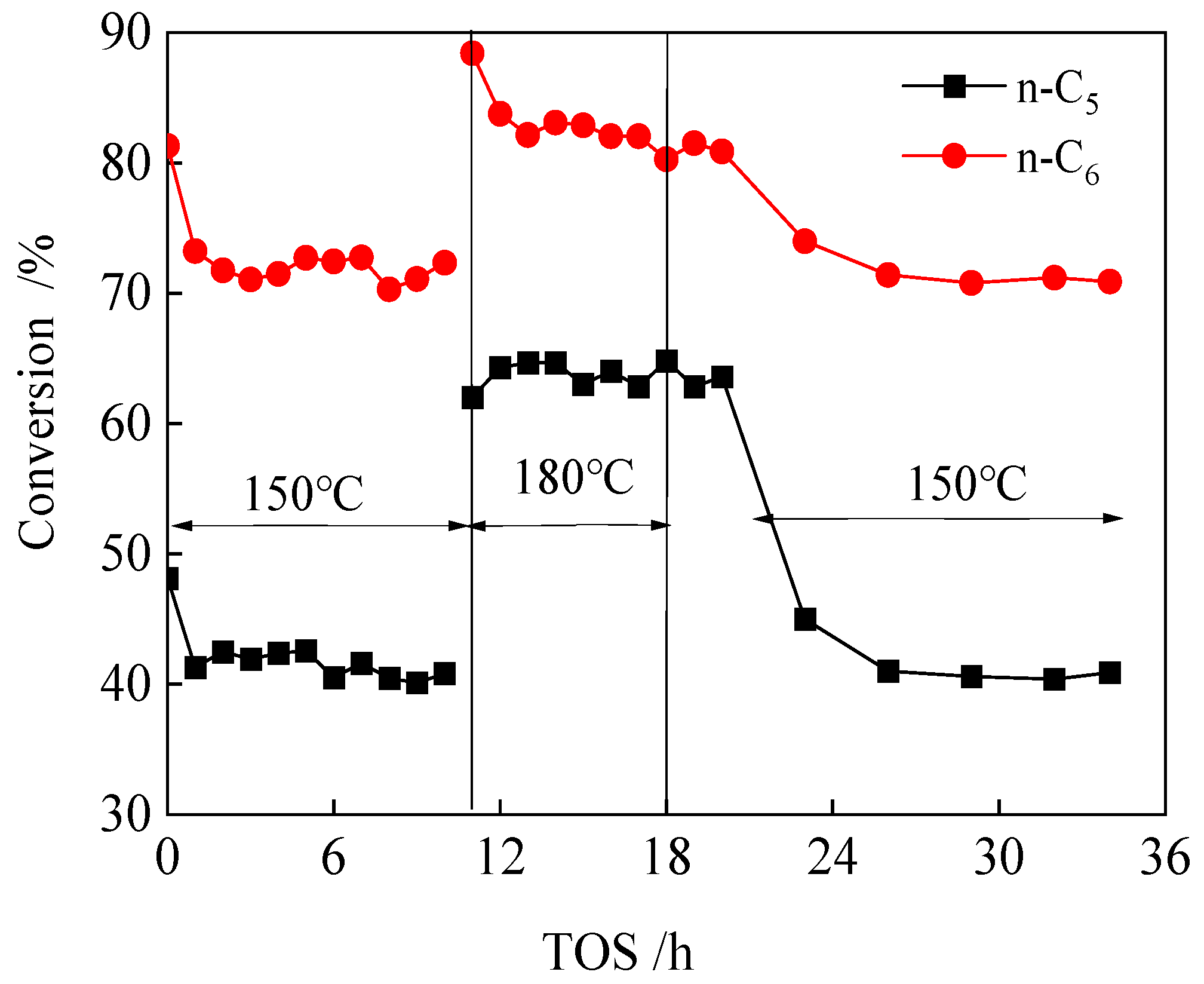

2.2.1. Isomerization Behavior of n-C5 or n-C6 Feed and Mixed n-C5/n-C6

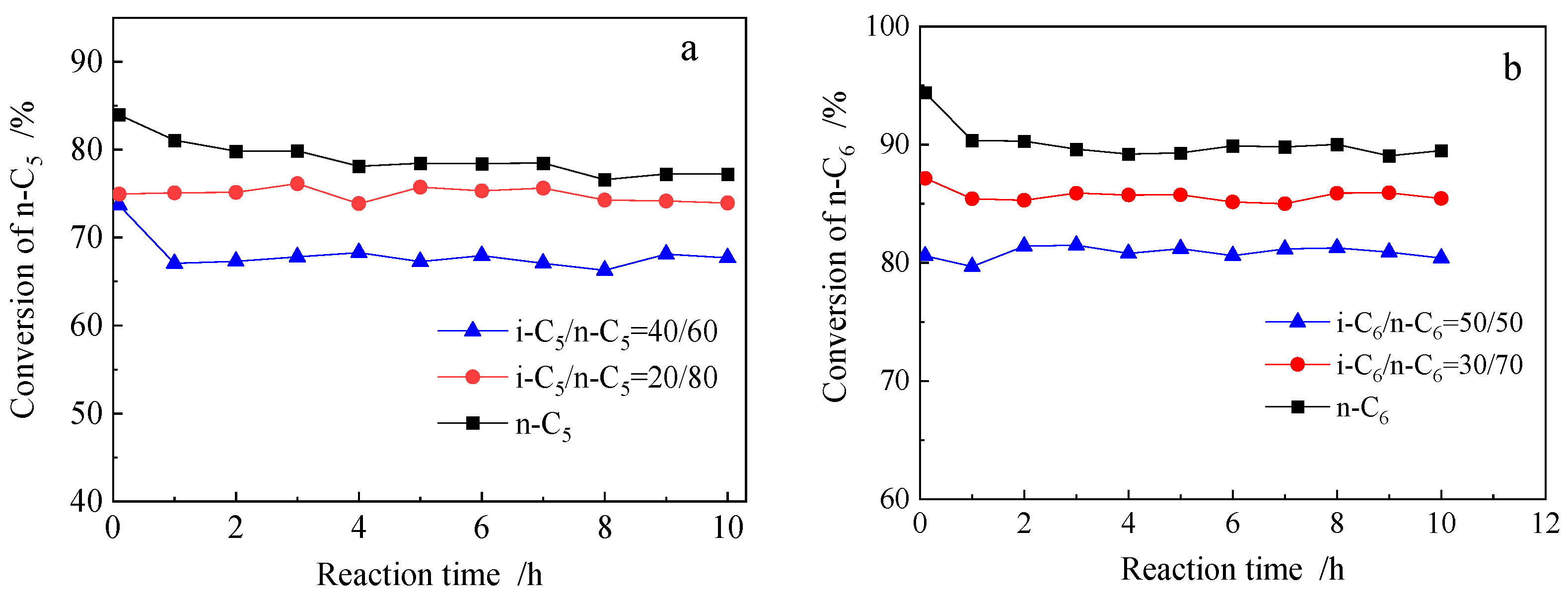

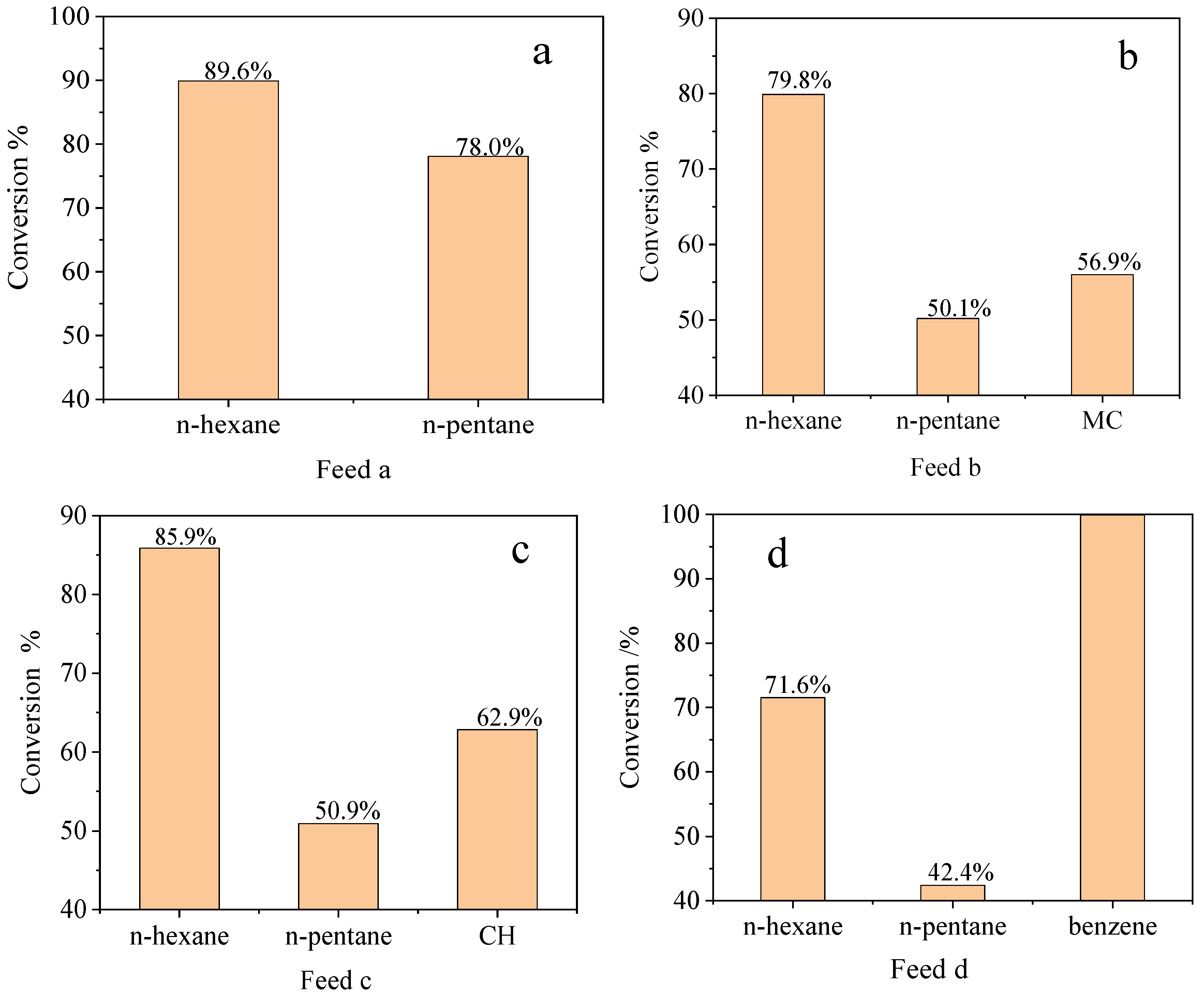

2.2.2. n-Alkane Isomerization Activity Comparison of Different Mixed Feeds

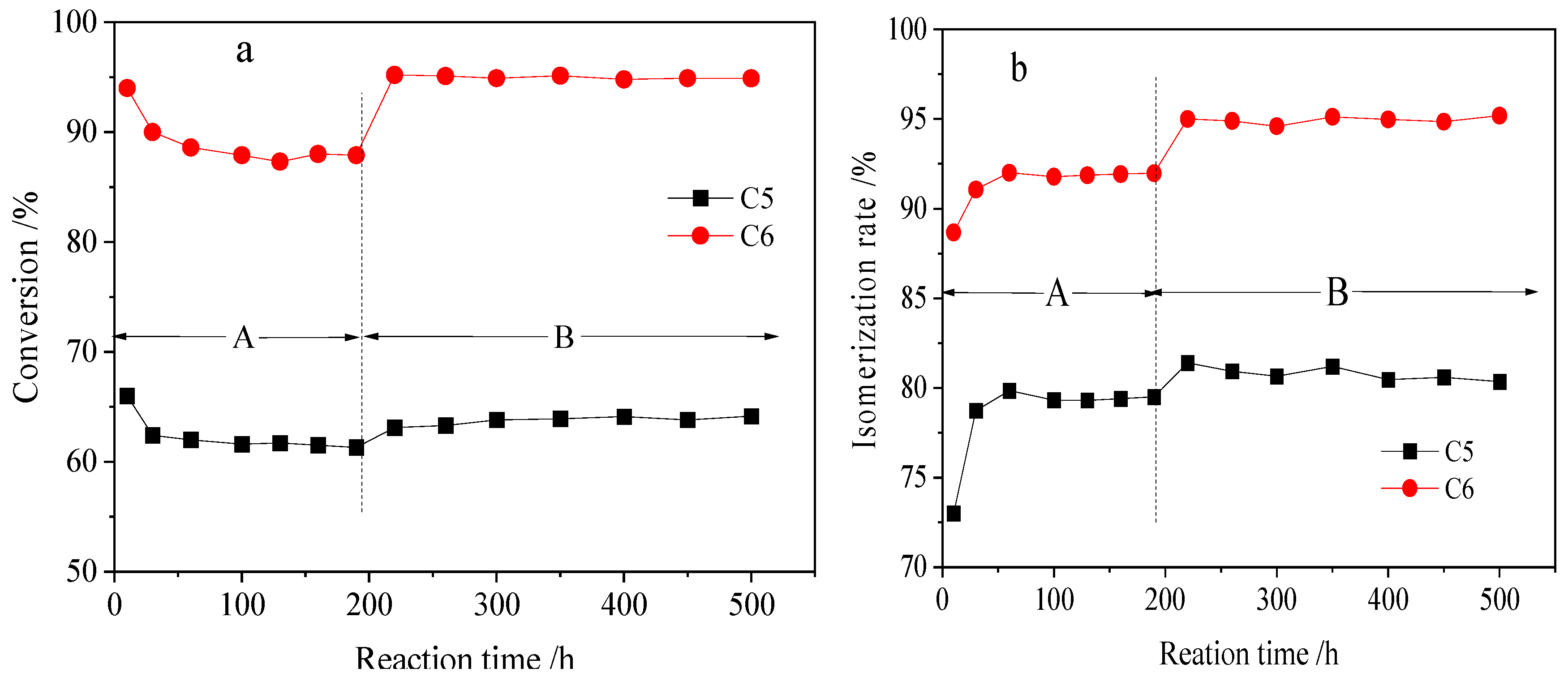

2.2.3. Isomerization Behavior of Industrial Feeds from Different Refineries

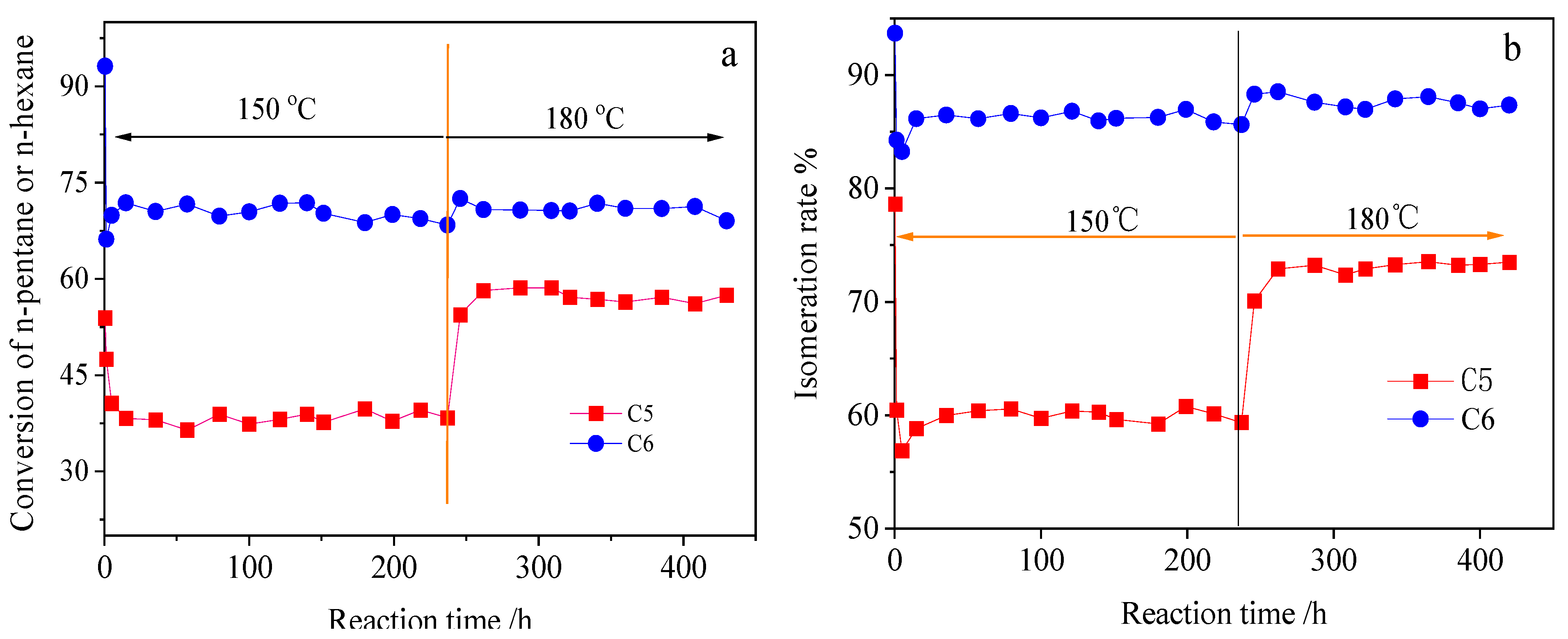

2.2.4. Influence of Hydrocarbon Impurities (Cycloalkanes and Benzene) on Isomerization Performance of PSZA

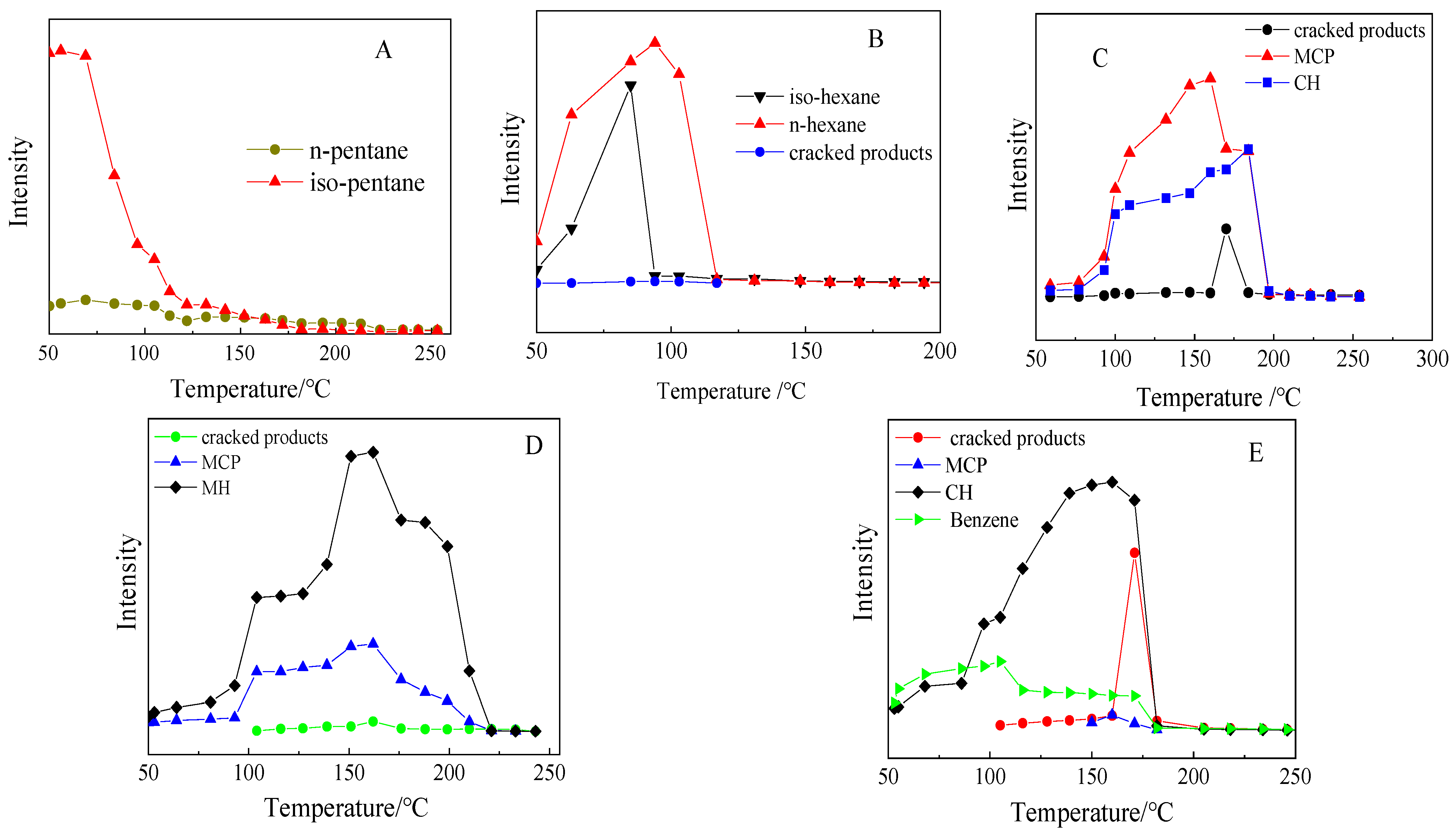

2.3. Programmed Temperature Surface Reaction of Different Feeds on PSZA

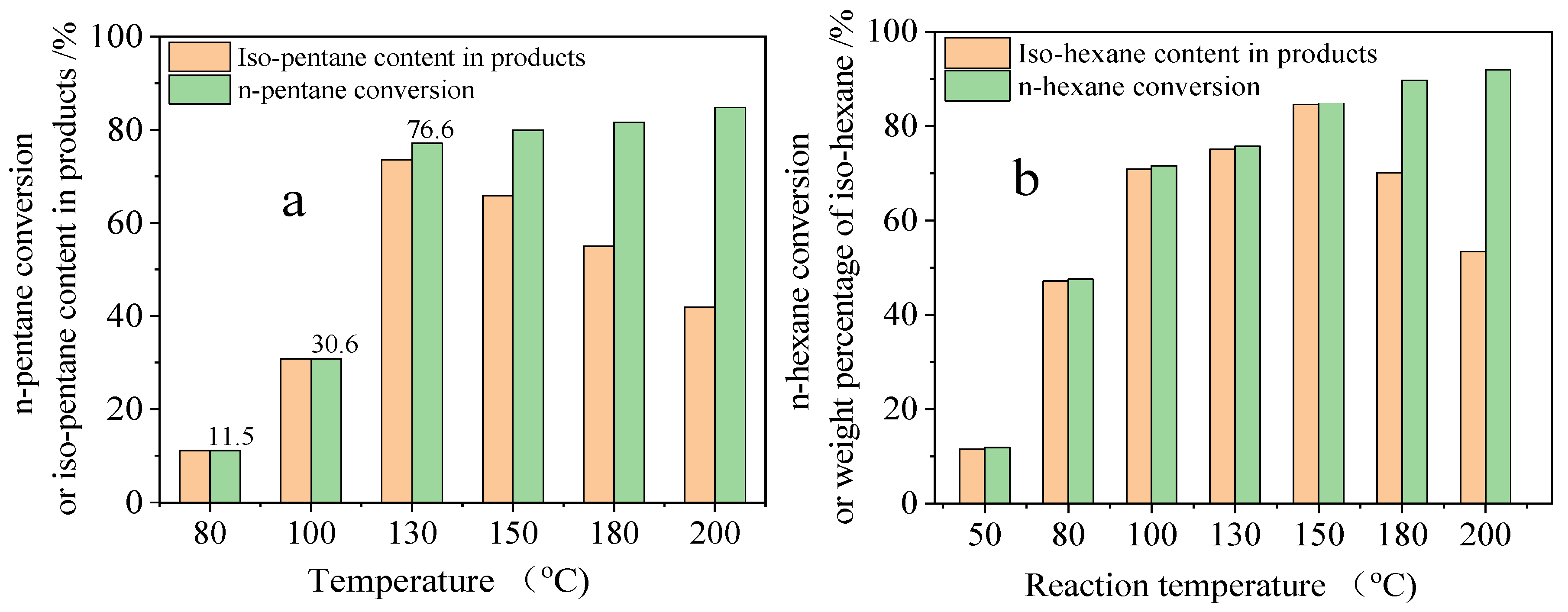

2.4. Intrinsic Activity of n-Pentane and n-Hexane Isomerization on PSZA Through Pulse Reaction

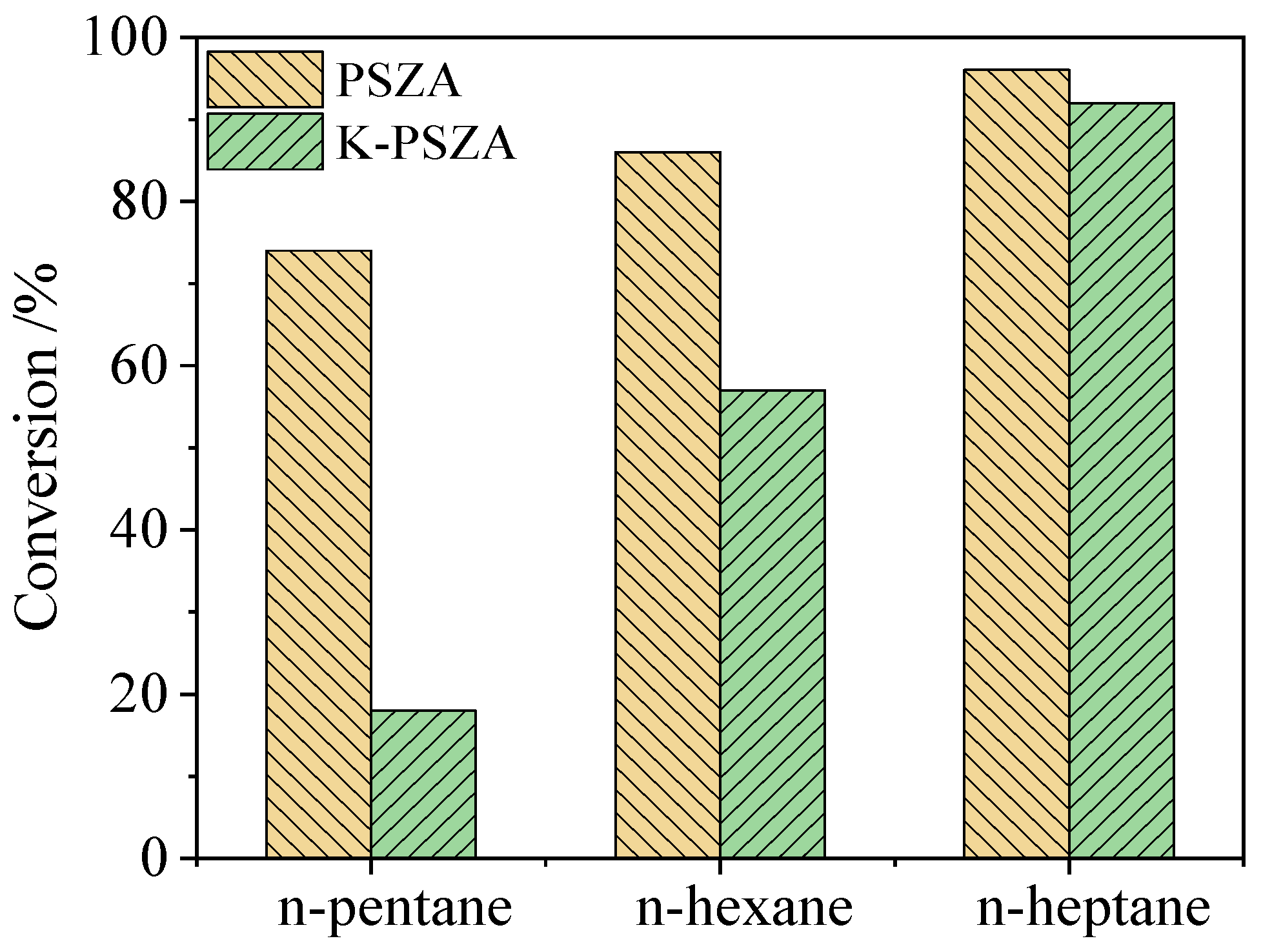

2.5. Effect of Hydrocarbon Impurities in the Prepared Mixed Feed on Isomerization Activity of n-Alkane

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Catalyst Preparation

4.2. Catalyst Characterization

4.3. Catalyst Activity Evaluation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ai, G. Preparation of SO42−/ZrO2 solid superacid catalyst and its effect on the isomerization of n-hexane. China Ceram. 2019, 2, 15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Song, H.; Zhao, L.; Song, H.L.; Wang, N.; Li, F. Effect of La content on structure and isomerization of Ni-S2O82−/ZrO2-Al2O3 solid superacid catalyst. J. China Univ. Pet. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2015, 39, 150–156. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, H.K.; Song, H.; Qin, H. Preparation and catalytic performance of metal-modified solid superacid catalysts. Energy Chem. Ind. 2020, 41, 15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, X.P.; Yu, Z.W.; Liu, H.Q.; Chen, Y.H.; Huang, Y.K.; Xin, M.D. Influences of calcination temperature of Pt-SO42−/ZrO2-Al2O3 catalysts and their catalytic performance for isobutane isomerization. Acta Pet. Sin. (Pet. Process. Sect.) 2024, 40, 75–82. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Z.Y.; Xu, H.Q.; Liu, Q.J.; Jia, L.M. Pt-Ni/SZA catalyst for isomerization of n-hexane. Petrochemicals 2022, 51, 863–869. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, X.M.; Zheng, J.; Fu, J.Y.; Lyu, Y.C.; Cheng, Z.L.; Li, F.R.; Zhang, W.J. Zeolite pore confinement in adsorption and skeletal isomerization of n-hexane. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2025, 317, 122072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K.; Ma, A.Z.; Li, J.Z.; Kong, L.J.; Liu, H.Q.; Yu, Z.W.; Li, D.D. Alkali-acid treated hierarchical Pt/Beta bifunctional catalyst for higher selectivity of multi-branched i-heptane in n-heptane hydroisomerization. React. Kinet. Mech. Catal. 2025, 138, 2277–2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.Z.; Wang, S.Q.; Yang, C.H.; Li, C.Y.; Bao, X.J. Effect of Aluminum Addition and Surface Moisture Content on the Catalytic Activity of Sulfated Zirconia in n-Butane Isomerization. Eng. Chem. Res. 2019, 58, 14638–14645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.S.; Wang, X.P.; Jin, S. Mechanism of isomerization and cracking reaction of n-alkanes catalyzed by solid superacid SO42−/ZrO2. J. Hangzhou Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 1994, 3, 289–305. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S.N.; Song, Y.Q.; Zhao, J.G.; Zhou, X.L.; Chen, L.F. Study on the Mechanism of Water Poisoning Pt-Promoted Sulfated Zirconia Alumina n-Hexane Isomerization. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 14860–14867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.N.; Song, Y.Q.; Zhou, X.L. Study on the Role of Hydrogen in nHexane Isomerization Over Pt Promoted Sulfated Zirconia Catalyst. Catal. Lett. 2023, 153, 2406–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.N.; Song, Y.Q.; Zhao, J.G.; Zhou, X.L. Impacts of Alumina Introduction on a Pt-SO42−/ZrO2 Catalyst in Light Naphtha Isomerization. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2022, 61, 1285–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.Y.; Song, Y.Q.; Ni, H.W.; Xu, J.; Zhou, X.L. Formation and life of solid superacid C5/C6 isomerization catalyst. Pet. Refin. Chem. Ind. 2018, 49, 79–86. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, C.M.; Yang, C.H. Petroleum Refining Engineering, 4th ed.; Petroleum Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Guisnet, M.; Fouche, V. Isomerization of n-hexane on platinum dealuminated mordenite catalysts III. Influence of hydrocarbon impurities. Appl. Catal. 1991, 71, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuta, S. The effect of electric type of platinum complex ion on the isomerization activity of Pt-loaded sulfated zirconia-alumina. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2003, 251, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korica, N.; Hassine, A.B.; Thi, H.D.; Bergaoui, L.; Geem, K.M.V.; Mendes, P.S.F.; Clercq, J.D.; Thybaut, J.W. Mixture effects in alkane/cycloalkane hydroconversion over Pt/HUSY: Carbon number impact. Fuel 2022, 318, 123651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.L.; Liu, H.Q.; Lan, Y.; Zhang, H.B.; Yu, Z.W.; Zhang, X.; Su, Y.F.; Liang, S.K. Transformation of a semi-regenerative reforming unit into a solid superacid C5/C6 isomerization unit Industrial Practice. Pet. Refin. Chem. Ind. 2023, 54, 58–64. [Google Scholar]

- Busto, M.; Grau, J.M.; Canavese, S.; Vera, C.R. Simultaneous Hydroconversion of n-Hexane and Benzene over Pt/WO3-ZrO2 in the Presence of Sulfur Impurities. Energy Fuels 2009, 23, 599–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busto, M.; Grau, J.M.; Sepulveda, J.H.; Tsendra, O.M.; Vera, C.R. Hydrocracking of Long Paraffins over Pt−Pd/WO3-ZrO2 in the Presence of Sulfur and Aromatic Impurities. Energy Fuels 2013, 27, 6962–6977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodegheroa, E.; Chenetb, T.; Martuccia, A.; Ardita, M.; Sartib, E.; Pasti, L. Selective adsorption of toluene and n-hexane binary mixture from aqueous solution on zeolite ZSM-5: Evaluation of competitive behavior between aliphatic and aromatic compounds. Catal. Today 2020, 345, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galinsky, M.; Lutecki, M.; Bohm, J.; Papp, H.; Breitkopf, C. Sorption of alkanes on sulfated zirconias—Modeling of TAP response curves. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2011, 66, 1932–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.G.; Lu, M.Z.; Ying, H.J.; Zhang, H.Y.; Hu, X.Y.; Ji, J.B.; Tian, X.M.; Liu, X.J. Molecular Simulation of adsorption of three cycloalkanes in MCM-41 molecular sieve. Comput. Appl. Chem. 2014, 31, 921–924. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, W.X.; Xu, B.W.; Li, Q.C.; Long, C. Competitive adsorption properties of toluene and cyclohexane on activated carbon. Ion Exch. Adsorpt. 2019, 35, 385–394. [Google Scholar]

- Li, F.C.; Yuan, Q.M.; Wei, X.L. Effect of molecular structure of hydrocarbon on catalytic cracking performance. Acta Pet. Sin. 2020, 36, 661–666. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.S.; Wu, L.Y.; Liu, H.J.; Long, C. Adsorption and penetration characteristics of two-component VOCs on adsorbent resin. China Environ. Sci. 2020, 40, 1982–1990. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y.Q.; Zhu, X.X.; Xie, S.J.; Wang, Q.X.; Xu, L.Y. The effect of acidity on olefin aromatization over Potassium modified ZSM-5 catalyst. Catal. Lett. 2004, 97, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Component | Hexane | Pentane | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2,2-DMB | 2,3-DMB | 2-MP | 3-MP | n-C6 | MB | n-C5 | |

| Equilibrium composition % | 36.4 | 9.1 | 29.0 | 16.0 | 9.5 | 80.0 | 20.0 |

| Composition/wt% | n-C4 | i-C5 | n-C5 | i-C6 | n-C6 | B | MCP | CH | i-C7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feed-A | 7.0 | 34.4 | 36.4 | 13.6 | 6.8 | 1.2 | 0.6 | ||

| Feed-B | 6.5 | 28.5 | 34.5 | 12.9 | 15.6 | 1.3 | 0.7 | ||

| Feed-C | 3.9 | 12.9 | 22.4 | 20.6 | 21.8 | 0 | 9.1 | 5.0 | 4.3 |

| Feed | Feed Composition wt% | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n-C5 | n-C6 | MCP | CH | B | |

| a | 50 | 50 | |||

| b | 48.2 | 45.3 | 6.5 | ||

| c | 46.8 | 45.7 | 7.5 | ||

| d | 47.0 | 46.5 | 6.5 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Song, Y.; Peng, Z.; Huang, L.; Chen, L.; Zhou, X. Isomerization Behavior Comparison of Single Hydrocarbon and Mixed Light Hydrocarbons over Super-Solid Acid Catalyst Pt/SO42−/ZrO2/Al2O3. Catalysts 2026, 16, 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020164

Song Y, Peng Z, Huang L, Chen L, Zhou X. Isomerization Behavior Comparison of Single Hydrocarbon and Mixed Light Hydrocarbons over Super-Solid Acid Catalyst Pt/SO42−/ZrO2/Al2O3. Catalysts. 2026; 16(2):164. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020164

Chicago/Turabian StyleSong, Yueqin, Ziyuan Peng, Lei Huang, Lifang Chen, and Xiaolong Zhou. 2026. "Isomerization Behavior Comparison of Single Hydrocarbon and Mixed Light Hydrocarbons over Super-Solid Acid Catalyst Pt/SO42−/ZrO2/Al2O3" Catalysts 16, no. 2: 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020164

APA StyleSong, Y., Peng, Z., Huang, L., Chen, L., & Zhou, X. (2026). Isomerization Behavior Comparison of Single Hydrocarbon and Mixed Light Hydrocarbons over Super-Solid Acid Catalyst Pt/SO42−/ZrO2/Al2O3. Catalysts, 16(2), 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020164