Nitrogen-Doped MgO as an Efficient Photocatalyst Under Visible Light for the Degradation of Methylene Blue in Wastewater Treatment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Characterization of Samples

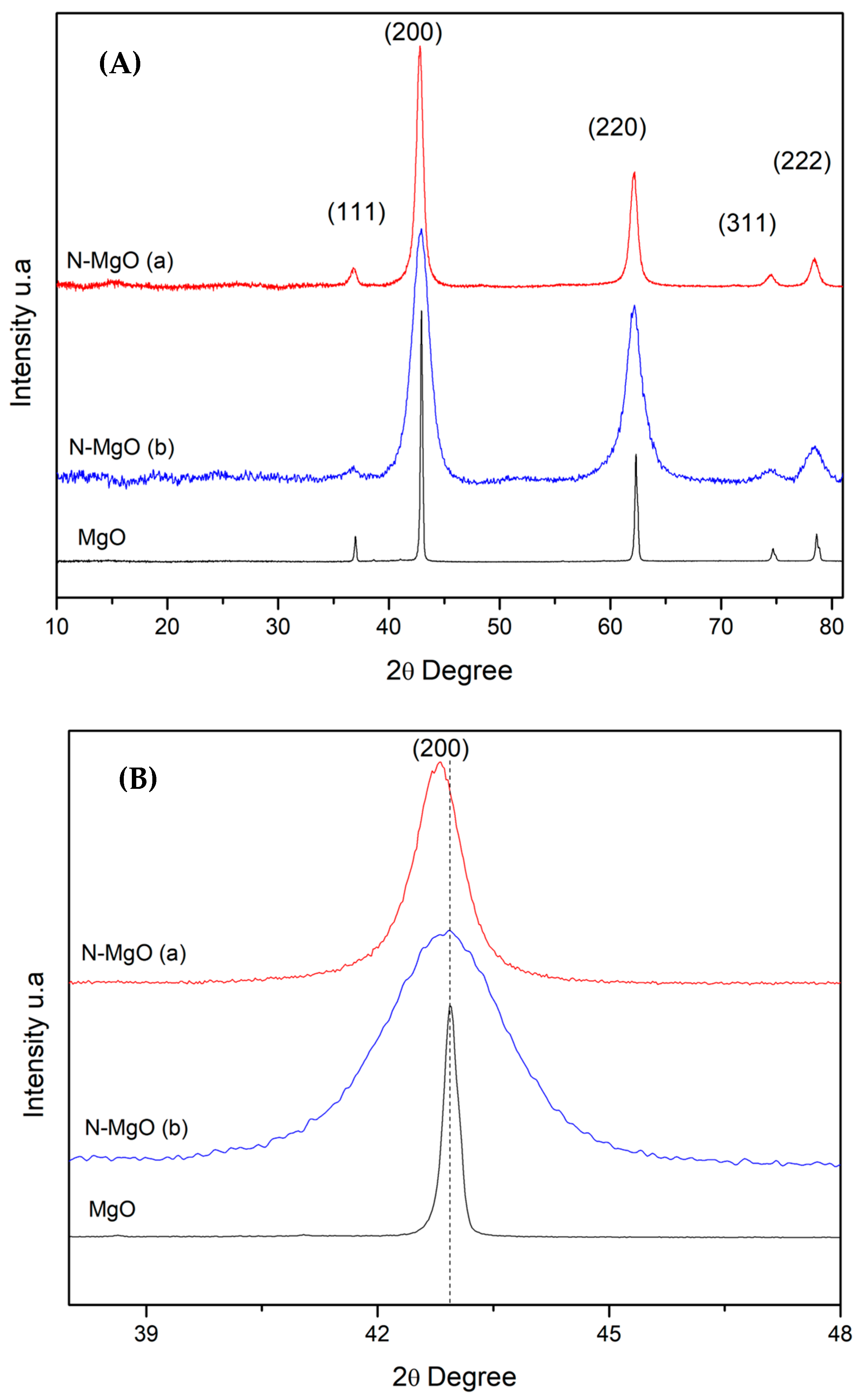

2.1.1. Wide-Angle X-Ray Diffraction

2.1.2. Raman Analysis

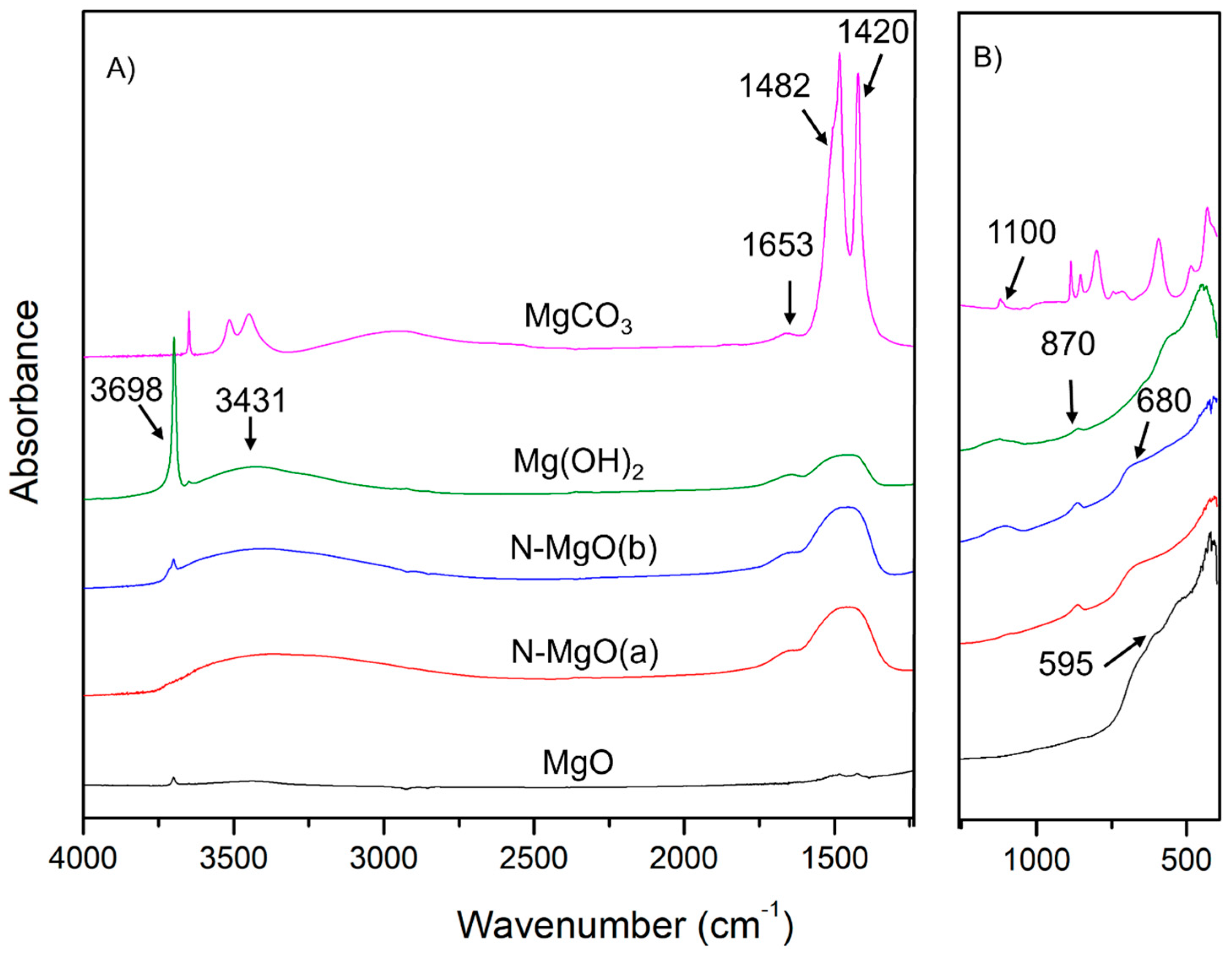

2.1.3. Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) Spectroscopy

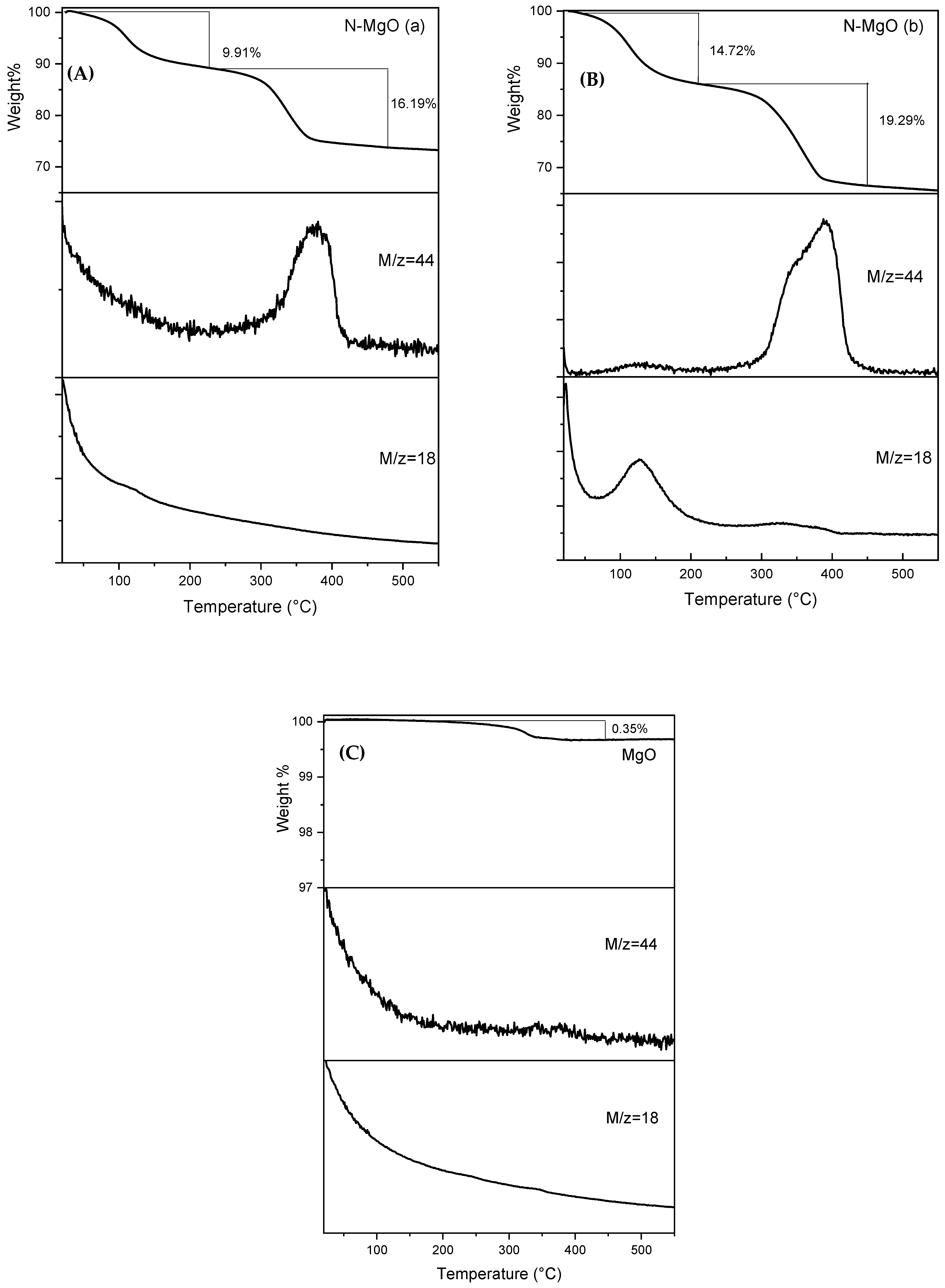

2.1.4. TGA-MS Analysis

2.1.5. SEM-EDX Analysis

2.1.6. BET (Brunauer–Emmett–Teller) Analysis

2.1.7. PZC Evaluation

2.1.8. UV–Vis Diffuse Reflectance Spectroscopy (DRS) and Photoluminescence Spectroscopy (PL)

2.2. Photocatalytic Activity Results

2.2.1. Mechanism for MB Photodegradation

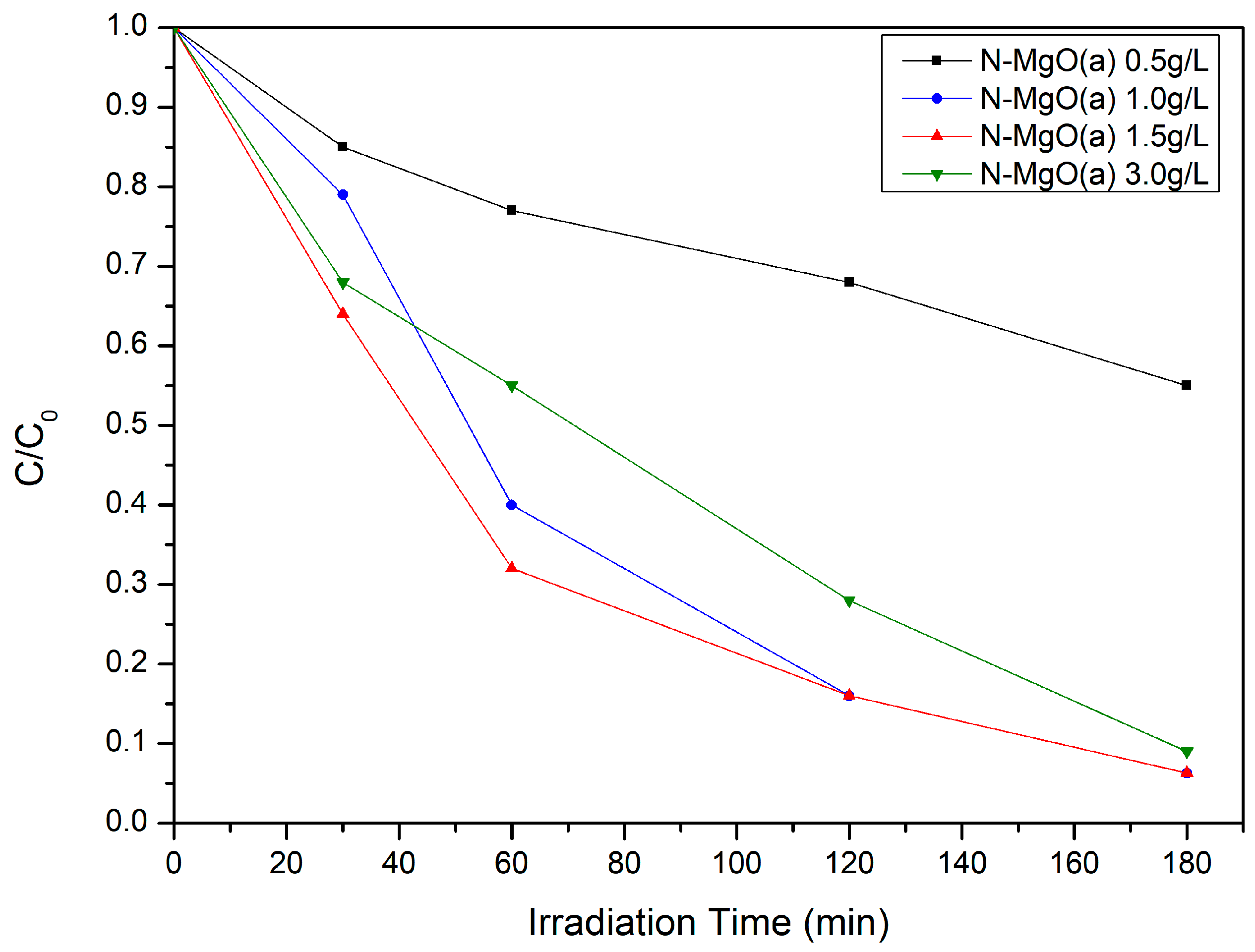

2.2.2. Effect of N-MgO(a) Dosage in MB Photodegradation

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Synthesis and Characterization of N-MgO

3.2.1. In Situ Doping of N-MgO(a)

3.2.2. Post-Synthesis Doping of N-MgO(b)

3.3. Characterization of N-MgO

3.4. Photocatalytic Activity Tests

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abou Zeid, S.; Leprince-Wang, Y. Advancements in ZnO-based photocatalysts for water treatment: A comprehensive review. Crystals 2024, 14, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.K.B.; Kumar, P.; Kebaili, I.; Boukhris, I.; Joo, Y.H.; Sung, T.H. Optimization and modelling of magnesium oxide (MgO) photocatalytic degradation of binary dyes using response surface methodology. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 9412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yagub, M.T.; Sen, T.K.; Afroze, S.; Ang, H.M. Dye and its removal from aqueous solution by adsorption: A Review. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2014, 209, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Z.; Williams, C.J.; Edyvean, R.G.J. Treatment of tannery wastewater by chemical coagulation. Desalination 2004, 164, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opoku, F.; Govender, K.K.; van Sittert, C.G.C.E.; Govender, P.P. Recent progress in the development of semiconductor-based photocatalyst materials for applications in photocatalytic water splitting and degradation of pollutants. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 2017, 1, 1700006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, F.; Kambala, V.S.R.; Srinivasan, M.; Rajarathnam, D.; Naidu, R. Tailored titanium dioxide photocatalysts for the degradation of organic dyes in wastewater treatment: A review. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2009, 359, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.M.; Lai, C.W.; Ngai, K.S.; Juan, J.C. Recent developments of zinc oxide based photocatalyst in water treatment technology: A review. Water Res. 2016, 88, 428–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitam, C.N.C.; Jalil, A.A. A review on exploration of Fe2O3 photocatalyst towards degradation of dyes and organic contaminants. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 258, 110050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babyszko, A.; Wanag, A.; Sadłowski, M.; Kusiak-Nejman, E.; Morawski, A.W. Synthesis and characterization of SiO2/TiO2 as photocatalyst on methylene blue degradation. Catalysts 2022, 12, 1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, Y.H.; Iwase, A.; Kudo, A.; Amal, R. Reducing graphene oxide on a visible-light BiVO4 photocatalyst for an enhanced photoelectrochemical water splitting. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2010, 1, 2607–2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.M.; Syed, F.A.; Al-Mayouf, A. Metal oxides as photocatalysts. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2015, 19, 462–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariharan, C. Photocatalytic degradation of organic contaminants in water by ZnO nanoparticles: Revisited. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2006, 304, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, G.; Velavan, R.; Batoo, K.M.; Raslan, E.H. Microstructure, optical and photocatalytic properties of MgO nanoparticles. Results Phys. 2020, 16, 103013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornak, J. Synthesis, Properties, and selected technical applications of magnesium oxide nanoparticles: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, Y.H.; Ng, A.M.C.; Xu, X.; Shen, Z.; Gethings, L.A.; Wong, M.T.; Chan, C.M.N.; Guo, M.Y.; Ng, Y.H.; Djurišić, A.B.; et al. Mechanisms of antibacterial activity of MgO: Non-ROS mediated toxicity of MgO nanoparticles towards Escherichia coli. Small 2014, 10, 1171–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Cao, L.; Xing, G.; Bai, Z.; Huang, J.; Zhang, Z. Flower-like magnesium oxide microparticles for highly efficient photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes in aqueous solution. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 7338–7348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Silva, R.T.; Ratnayake, S.P.; Amaratunga, G. Photocatalytic activity of electrospun MgO nanofibres: Synthesis, characterization and applications. Mater. Res. Bull. 2018, 99, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, H.; Anwer, M.; Khan, S.; Saad, M. Enhancement of adsorption and photocatalytic activity of MgO nanoparticles for the treatment of textile dye using ultrasound assisted process by response surface methodology. Desalination Water Treat. 2024, 319, 100429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiogai, J.; Ito, Y.; Mitsuhashi, T.; Nojima, T.; Tsukazaki, A. Electric-field-induced superconductivity in electrochemically etched ultrathin FeSe films on SrTiO3 and MgO. Nat. Phys. 2016, 12, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthik, K.; Dhanuskodi, S.; Gobinath, C.; Prabukumar, S.; Sivaramakrishnan, S. Fabrication of MgO nanostructures and its efficient photocatalytic, antibacterial and anticancer performance. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2019, 190, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruk, A. Fabrication of MgO high transparent ceramics by arc plasma synthesis. Opt. Mater. 2018, 84, 360–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raveesha, H.R.; Kumar, P.; Raghavendra, G.M.; Yathisha, R.O.; Kumara, K.; Raghu, G.K.; Rangappa, D. The electrochemical behavior, antifungal and cytotoxic activities of phytofabricated MgO nanoparticles using Withania somnifera leaf extract. J. Sci. Adv. Mater. Devices 2019, 4, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wang, X.; Khan, M.R.; Hammouda, G.A.; Alam, P.; Meng, L.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, W. New opportunities and advances in magnesium oxide (MgO) nanoparticles in biopolymeric food packaging films. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2024, 40, e00976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittag, A.; Schneider, T.; Westermann, M.; Glei, M. Toxicological assessment of magnesium oxide nanoparticles in HT29 intestinal cells. Arch. Toxicol. 2019, 93, 1491–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinthala, M.; Balakrishnan, A.; Venkataraman, P.; Manaswini Gowtham, V.; Polagani, R.K. Synthesis and applications of nano-MgO and composites for medicine, energy, and environmental remediation: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 4415–4454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, H.T.; Gençaslan, M.; Merdan, M. Synthesis of MgO nanoparticles via the sol-gel method for antibacterial applications, investigation of optical properties and comparison with commercial MgO. Discover Appl. Sci. 2024, 6, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, Y.J.; Park, S.J. Facile synthesis of MgO-modified carbon adsorbents with microwave-assisted methods: Effect of MgO particles and porosities on CO2 capture. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 5653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Dai, H.; Du, Y.; Deng, J.; Zhang, L.; Shi, F. Solvo- or hydrothermal fabrication and excellent carbon dioxide adsorption behaviors of magnesium oxides with multiple morphologies and porous structures. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2011, 128, 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tharani, K.; Jegatha Christy, A.; Sagadevan, S.; Nehru, L.C. Fabrication of magnesium oxide nanoparticles using combustion method for a biological and environmental cause. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2021, 763, 138216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreekanth, R.; Pattar, J.; Anupama, A.V.; Mallikarjunaswamy, A.M.M. Synthesis of high surface area and plate-like Magnesium Oxide nanoparticles by pH-controlled precipitation method. Appl. Phys. A 2021, 127, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhaymin, A.; Mohamed, H.E.A.; Hkiri, K.; Safdar, A.; Azizi, S.; Maaza, M. Green synthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles using Hyphaene thebaica extract and their photocatalytic activities. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 20135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirota, V.; Selemenev, V.F.; Kovaleva, M.G.; Pavlenko, I.A.; Mamunin, K.N.; Dokalov, V.; Prozorova, M.S. Synthesis of magnesium oxide nanopowder by thermal plasma using magnesium nitrate hexahydrate. Phys. Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 6853405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baidukova, O.; Skorb, E.V. Ultrasound-assisted synthesis of magnesium hydroxide nanoparticles from magnesium. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2016, 31, 423–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartley, J.K.; Xu, C.; Lloyd, R.; Enache, D.I.; Knight, D.W.; Hutchings, G.J. Simple method to synthesize high surface area magnesium oxide and its use as a heterogeneous base catalyst. Appl. Catal. B 2012, 128, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatou, M.-A.; Bovali, N.; Lagopati, N.; Pavlatou, E.A. MgO Nanoparticles as a Promising Photocatalyst towards Rhodamine B and Rhodamine 6G Degradation. Molecules 2024, 29, 4299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algethami, F.K.; Katouah, H.A.; Al-Omar, M.A.; Almehizia, A.A.; Amr, A.E.-G.E.; Naglah, A.M.; Al-Shakliah, N.S.; Fetoh, M.E.; Youssef, H.M. Facile synthesis of magnesium oxide nanoparticles for studying their photocatalytic activities against Orange G dye and biological activities against some bacterial and fungal strains. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. 2021, 31, 2150–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pammi, V.N.; Matangi, R.; Ummey, S.; Gurugubelli, T.R.; Datta, D.; Pallela, P.N.V.K.; Ruddaraju, L.K. Photocatalytic, antioxidant, and antibacterial activities of biocompatible MgO flake-like nanostructures created using Piper betle leaf extract. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 43248–43254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, S.; Moussavi, G.; Decker, J.; Marin, M.; Bosca, F.; Giannakis, S. Superior visible light-mediated catalytic activity of a novel N-doped, Fe3O4-incorporating MgO nanosheet in presence of PMS: Imidacloprid degradation and implications on simultaneous bacterial inactivation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2022, 317, 121732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marschall, R.; Wang, L. Non-metal doping of transition metal oxides for visible-light photocatalysis. Catal. Today 2014, 225, 111–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanaei, F.; Moussavi, G.; Srivastava, V.; Sillanpää, M. The enhanced catalytic potential of sulfur-doped MgO (S-MgO) nanoparticles in activation of peroxysulfates for advanced oxidation of Acetaminophen. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 371, 404–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senevirathna, H.L.; Lee, W.C.; Wu, S.; Bai, K.; Wu, P. Facile synthesis of bandgap-engineered N-doped MgO/g-C3N4 nanocomposites for enhanced sunlight-driven photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2024, 332, 130234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Tadé, M.O.; Shao, Z. Nitrogen-doped simple and complex oxides for photocatalysis: A review. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2018, 92, 33–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattab, M.; Oprea, O.C.; Cernea, M. Experimental study on thermal evolution from precursor gel to crystallized MgO for biomedical applications. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2025, 150, 3225–3236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, R. Raman spectroscopic study of the magnesium carbonate mineral hydromagnesite (Mg5[(CO3)4(OH)2]·4H2O). J. Raman Spectrosc. 2011, 42, 1690–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallick, L.; Samanta, K.; Chakraborty, B. Post-synthetic Metalation on the Ionic TiO2 Surface to Enhance Metal-CO2 Interaction During Photochemical CO2 Reduction. Chemistry 2024, 30, e202400428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, P.; Saini, R.; Bhaduri, A. Facile synthesis of MgO nanoparticles for effective degradation of organic dyes. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 71439–71453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahab, R.; Ansari, S.G.; Dar, M.A.; Kim, Y.S.; Shin, H.-S. Synthesis of Magnesium Oxide Nanoparticles by Sol-Gel Process. Mater. Sci. Forum 2007, 558–559, 983–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijaya Shanthi, R.; Kayalvizhi, R.; John Abel, M.; Neyvasagam, K. MgO nanoparticles with altered structural and optical properties by doping (Er3+) rare earth element for improved photocatalytic activity. Appl. Phys. A 2022, 128, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subash, M.; Chandrasekar, M.; Panimalar, S.; Inmozhi, C.; Parasuraman, K.; Uthrakumar, R.; Kaviyarasu, K. Pseudo-first kinetics model of copper doping on the structural, magnetic, and photocatalytic activity of magnesium oxide nanoparticles for energy application. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2023, 13, 3427–3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeevanandam, J.; Chan, Y.S.; Danquah, M.K. Calcination-Dependent Morphology Transformation of Sol-Gel- Synthesized MgO Nanoparticles. ChemistrySelect 2017, 2, 10393–10404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Yang, Z.; Wang, S. Influence of calcination temperature on the structure and hydration of MgO. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 262, 120776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gliński, M.; Czajka, A.; Ulkowska, U.; Iwanek, E.M.; Łomot, D.; Kaszkur, Z. A Hands-on Guide to the Synthesis of High-Purity and High-Surface-Area Magnesium Oxide. Catalysts 2022, 12, 1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.; Ramli, A. The determination of point zero charge (PZC) of Al2O3-MgO mixed oxides. In Proceedings of the 2011 National Postgraduate Conference, Perak, Malaysia, 19–20 September 2011; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Mancuso, A.; Navarra, W.; Sacco, O.; Pragliola, S.; Vaiano, V.; Venditto, V. Photocatalytic degradation of thiacloprid using tri-doped TiO2 photocatalysts: A preliminary comparative study. Catalysts 2021, 11, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Arya, S.; Singh, B.; Prerna; Tomar, A.; Singh, S.; Sharma, R. Sol-Gel Synthesis of Zn Doped MgO Nanoparticles and Their Applications. Integr. Ferroelectr. 2020, 205, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, N.; Ghosh, P.S.; Gupta, S.K.; Kadam, R.M.; Arya, A. Defects induced changes in the electronic structures of MgO and their correlation with the optical properties: A special case of electron–hole recombination from the conduction band. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 96398–96415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishnoi, P.; Brajpuriya, R.; Sharma, A.; Chae, K.H.; Won, S.O.; Vij, A. Defect modulation and color tuning of MgO: Probing the influence of Sm and Li dopants through X-ray absorption, photoluminescence, and thermoluminescence spectroscopy. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 1002, 175270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, B.K.; Karim, M.A.H. Efficient catalytic photodegradation of methylene blue from medical lab wastewater using MgO nanoparticles synthesized by direct precipitation method. React. Kinet. Mech. Catal. 2019, 128, 1127–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesci, M.; Gallino, F.; Di Valentin, C.; Pacchioni, G. Nature of defect states in nitrogen-doped MgO. J. Phys. Chem. C 2009, 114, 1350–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, G.; Tian, F.; Tang, H.; Chen, R. Rhodamine B-sensitized BiOCl hierarchical nanostructure for methyl orange photodegradation. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 7772–7779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roushani, M.; Mavaei, M.; Rajabi, H.R. Graphene quantum dots as novel and green nano-materials for the visible-light-driven photocatalytic degradation of cationic dye. J. Mol. Catal. A-Chem. 2015, 409, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Liao, X.; Lee, M.-H.; Hyett, G.; Huang, C.-C.; Hewak, D.W.; Mailis, S.; Zhou, W.; Jiang, Z. Experimental and DFT insights of the Zn-doping effects on the visible-light photocatalytic water splitting and dye decomposition over Zn-doped BiOBr photocatalysts. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2019, 243, 502–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trandafilović, L.V.; Jovanović, D.J.; Zhang, X.; Ptasińska, S.; Dramićanin, M.D. Enhanced photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue and methyl orange by ZnO:Eu nanoparticles. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2017, 203, 740–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, H.; Huang, G.; Zhang, Z.; Han, L.; Song, W.; Li, M.; Zhang, Y. Facile synthesis of urchin-like hierarchical Nb2O5 nanospheres with enhanced visible light photocatalytic activity. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 728, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; Zhang, X.J.; Zhou, W.F.; Wu, J.; Liu, Q.J. First-principles study on anatase TiO2 codoped with nitrogen and ytterbium. J. Semicond. 2010, 31, 032001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarra, W.; Ritacco, I.; Sacco, O.; Caporaso, L.; Farnesi Camellone, M.; Venditto, V.; Vaiano, V. Density functional theory study and photocatalytic activity of ZnO/N-doped TiO2 heterojunctions. J. Phys. Chem. C 2022, 126, 7000–7011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saint, U.K.; Baral, S.C.; Sasmal, D.; Maneesha, P.; Datta, S.; Naushin, F.; Sen, S. Effect of pH on photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue in water by facile hydrothermally grown TiO2 nanoparticles under natural sunlight. JCIS Open 2025, 19, 100150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Chang, Y.-Y.; Koduru, J.R.; Yang, J.-K. Potential degradation of methylene blue (MB) by nano-metallic particles: A kinetic study and possible mechanism of MB degradation. Environ. Eng. Res. 2017, 22, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamiji, T.; Nezamzadeh-Ejhieh, A. A comprehensive kinetic study on the electrocatalytic oxidation of propanols in aqueous solution. Solid State Sci. 2019, 98, 106033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Samples | Crystallite Size D (nm) | Lattice Parameters | Dislocation Density * δ = 1/D2 (1/nm2) | Microstrain ** ε (by W-H Plot) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Debye–Scherrer Sherrer | W-H Plot | ||||||

| a | b | c | |||||

| MgO | 42.72 | 42.02 | 4.21 | 4.21 | 4.21 | 0.000567 | 1.25 × 10−4 |

| N-MgO(a) | 12.37 | 12.84 | 4.22 | 4.22 | 4.87 | 0.00610 | 7.50 × 10−6 |

| N-MgO(b) | 4.720 | 4.27 | 4.22 | 4.23 | 4.24 | 0.0551 | 1.025 × 10−3 |

| Samples | Calcination Temperature (°C) | N/Mg | SBET (m2/g) | Ebg (eV) | PZC (pH) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MgO | - | - | 6 | - | 10.9 |

| N-MgO(a) | 350 | 0.047 | 35.6 | 3.8 | 10.5 |

| N-MgO(b) | 500 | 0.031 | 47.7 | 4 | 10.2 |

| Sample | D * (%) | Catalyst Dosage (g/L) | k (1/min) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MgO | 15 | 1.0 | 0.0008 | 0.9763 |

| N-MgO(b) | 48 | 1.0 | 0.0035 | 0.9976 |

| N-MgO(a) | 94 | 1.0 | 0.0156 | 0.9964 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pace, A.; Venditto, V.; Lettieri, M.; Vaiano, V.; Sacco, O. Nitrogen-Doped MgO as an Efficient Photocatalyst Under Visible Light for the Degradation of Methylene Blue in Wastewater Treatment. Catalysts 2026, 16, 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020162

Pace A, Venditto V, Lettieri M, Vaiano V, Sacco O. Nitrogen-Doped MgO as an Efficient Photocatalyst Under Visible Light for the Degradation of Methylene Blue in Wastewater Treatment. Catalysts. 2026; 16(2):162. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020162

Chicago/Turabian StylePace, Annalisa, Vincenzo Venditto, Mariateresa Lettieri, Vincenzo Vaiano, and Olga Sacco. 2026. "Nitrogen-Doped MgO as an Efficient Photocatalyst Under Visible Light for the Degradation of Methylene Blue in Wastewater Treatment" Catalysts 16, no. 2: 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020162

APA StylePace, A., Venditto, V., Lettieri, M., Vaiano, V., & Sacco, O. (2026). Nitrogen-Doped MgO as an Efficient Photocatalyst Under Visible Light for the Degradation of Methylene Blue in Wastewater Treatment. Catalysts, 16(2), 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020162