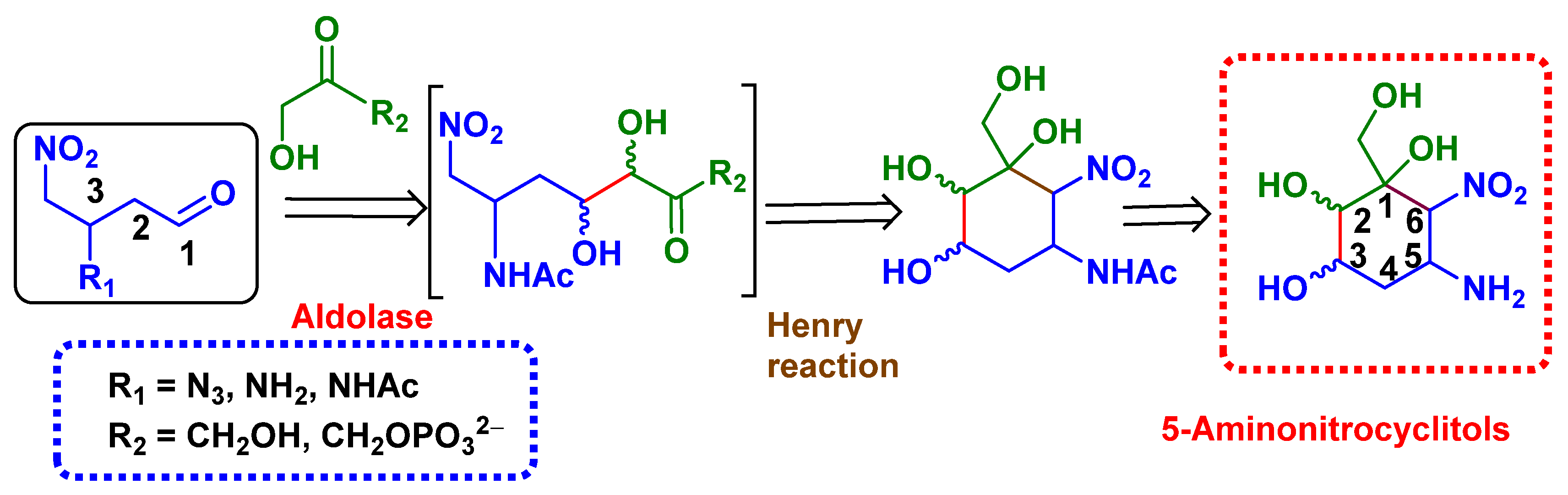

Straightforward Chemo-Multi-Enzymatic Cascade Systems for the Stereo-Controlled Synthesis of 5-Amino-6-nitrocyclitols

Abstract

1. Introduction

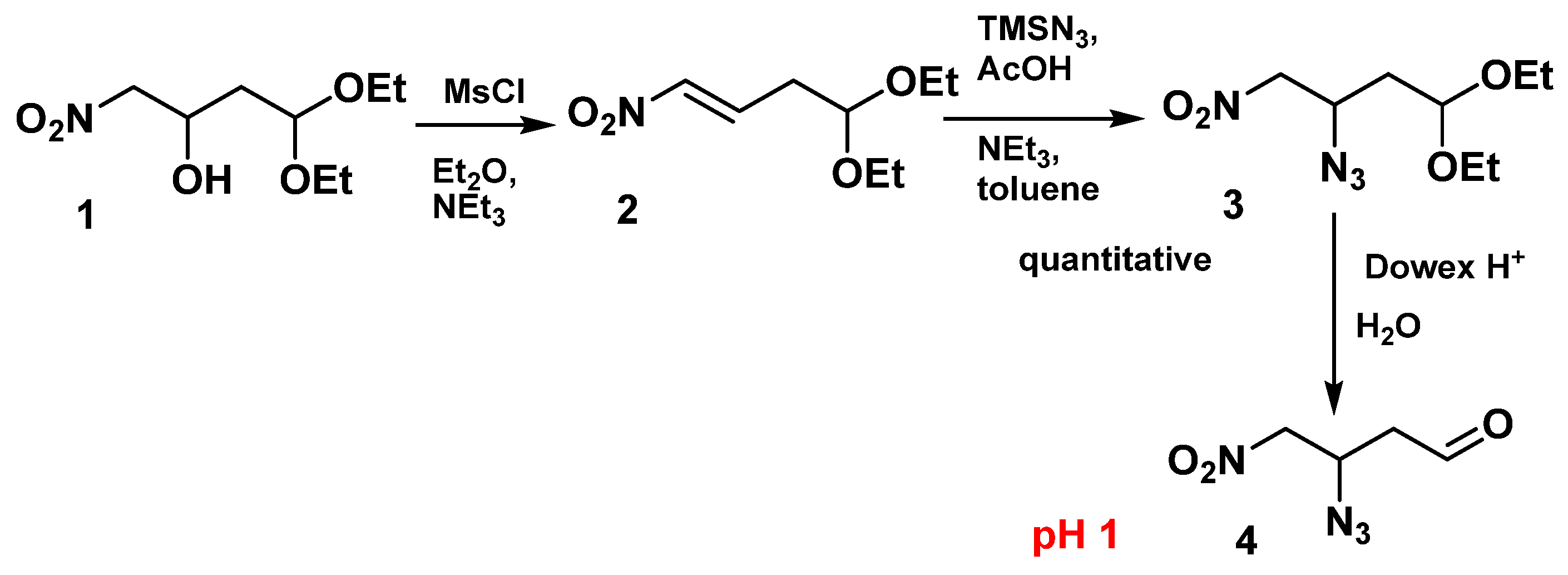

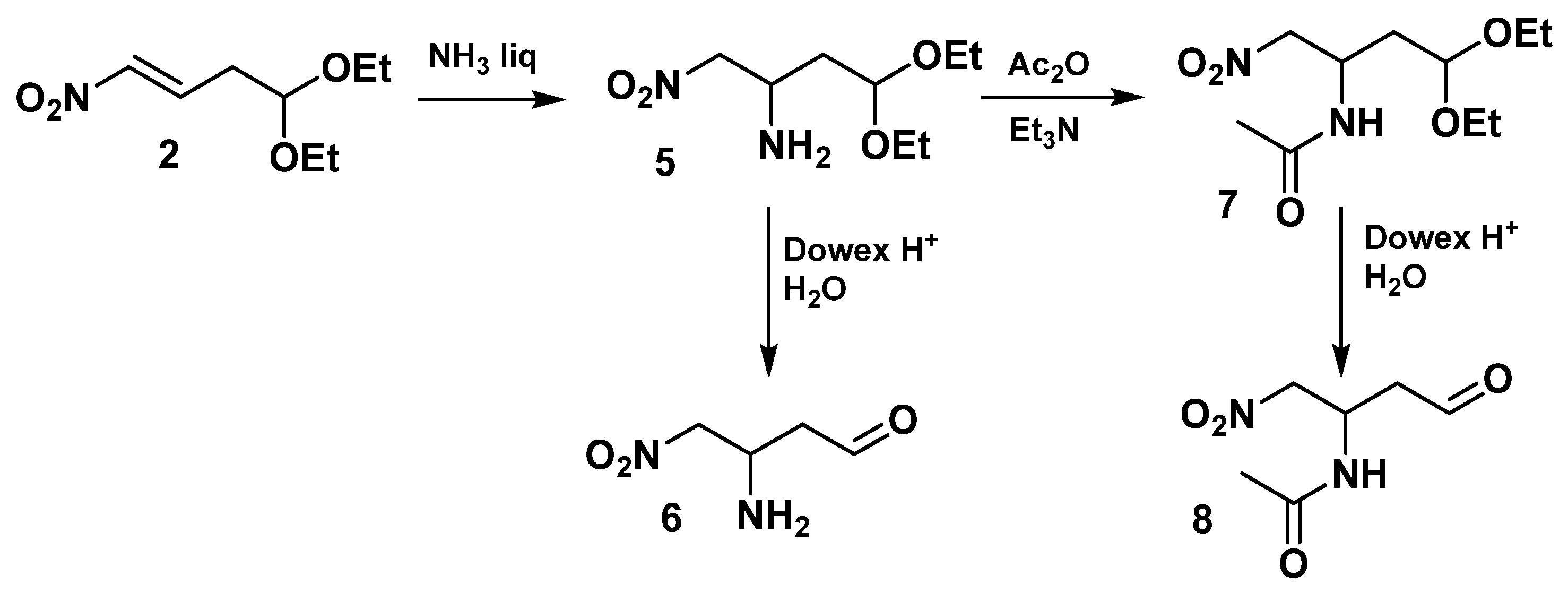

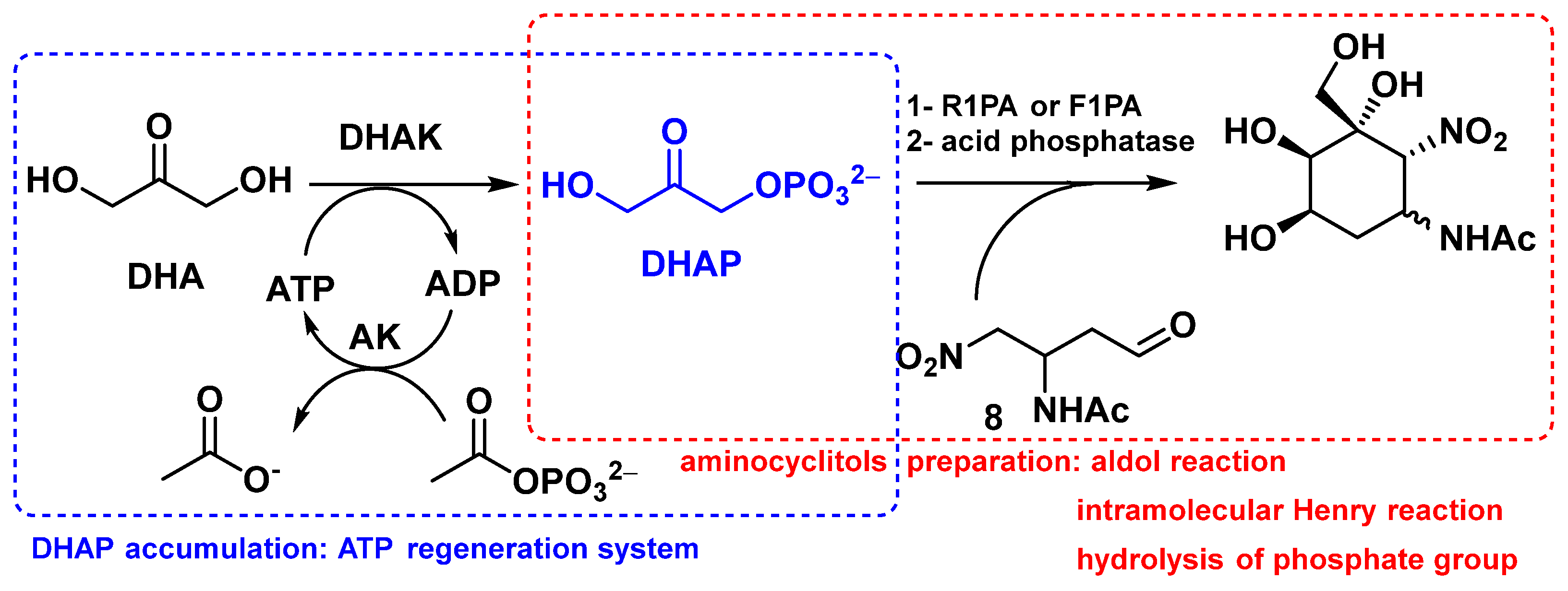

2. Results

2.1. Synthesis of Aldehydes

2.2. Enzymatic Couplings

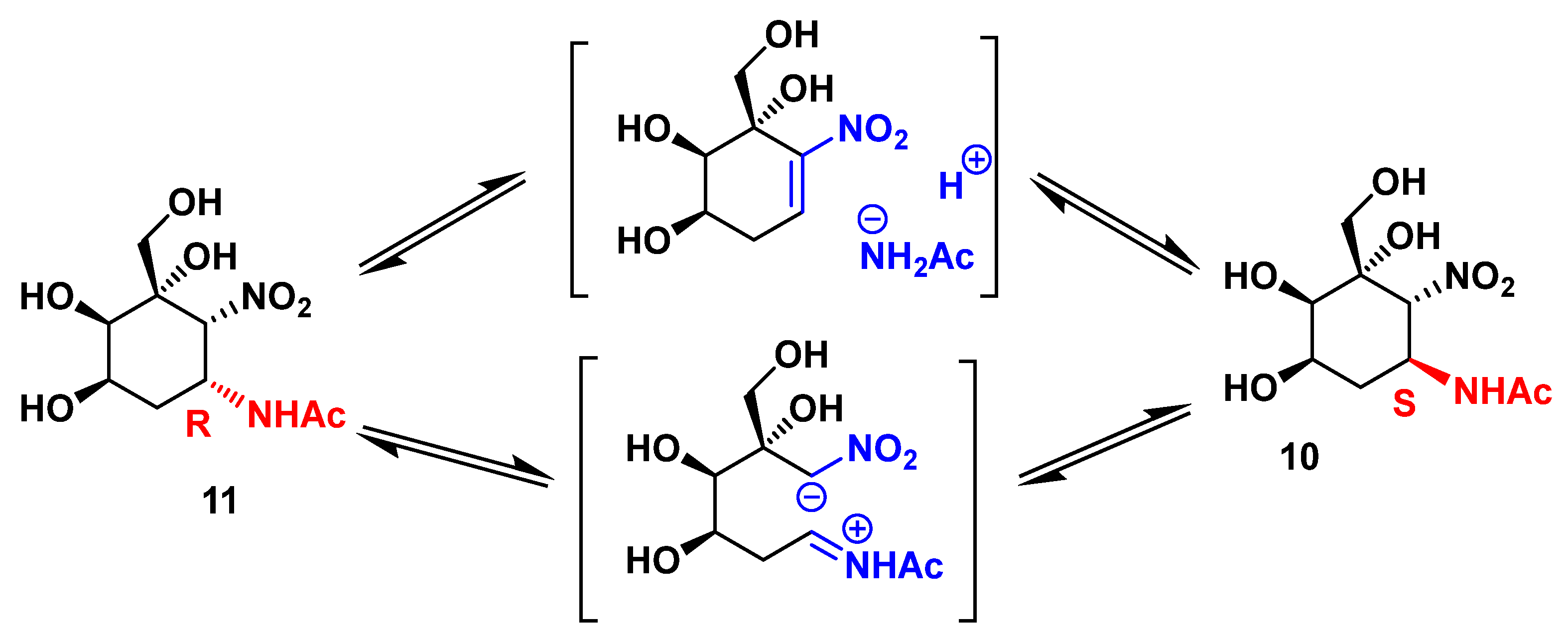

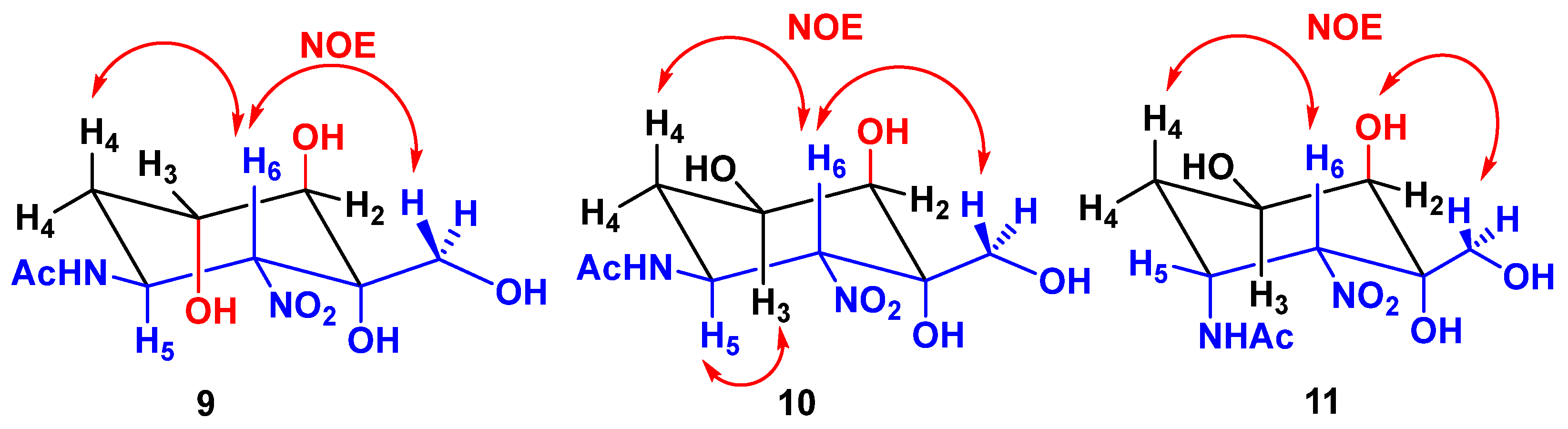

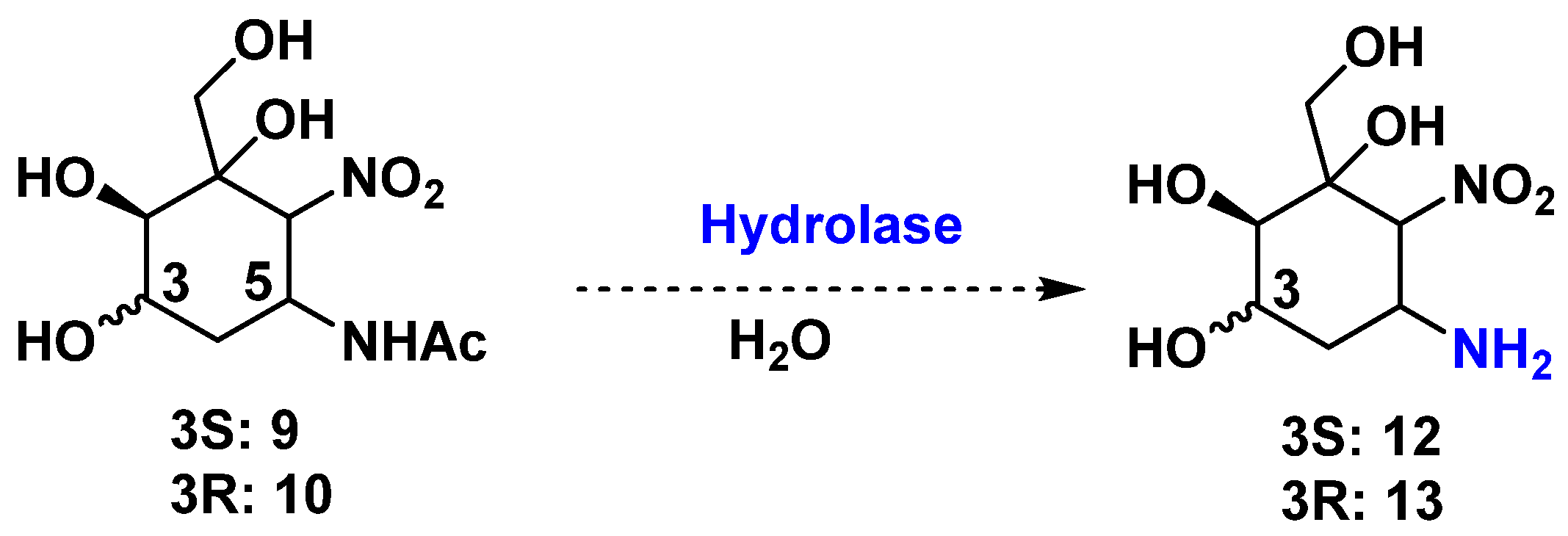

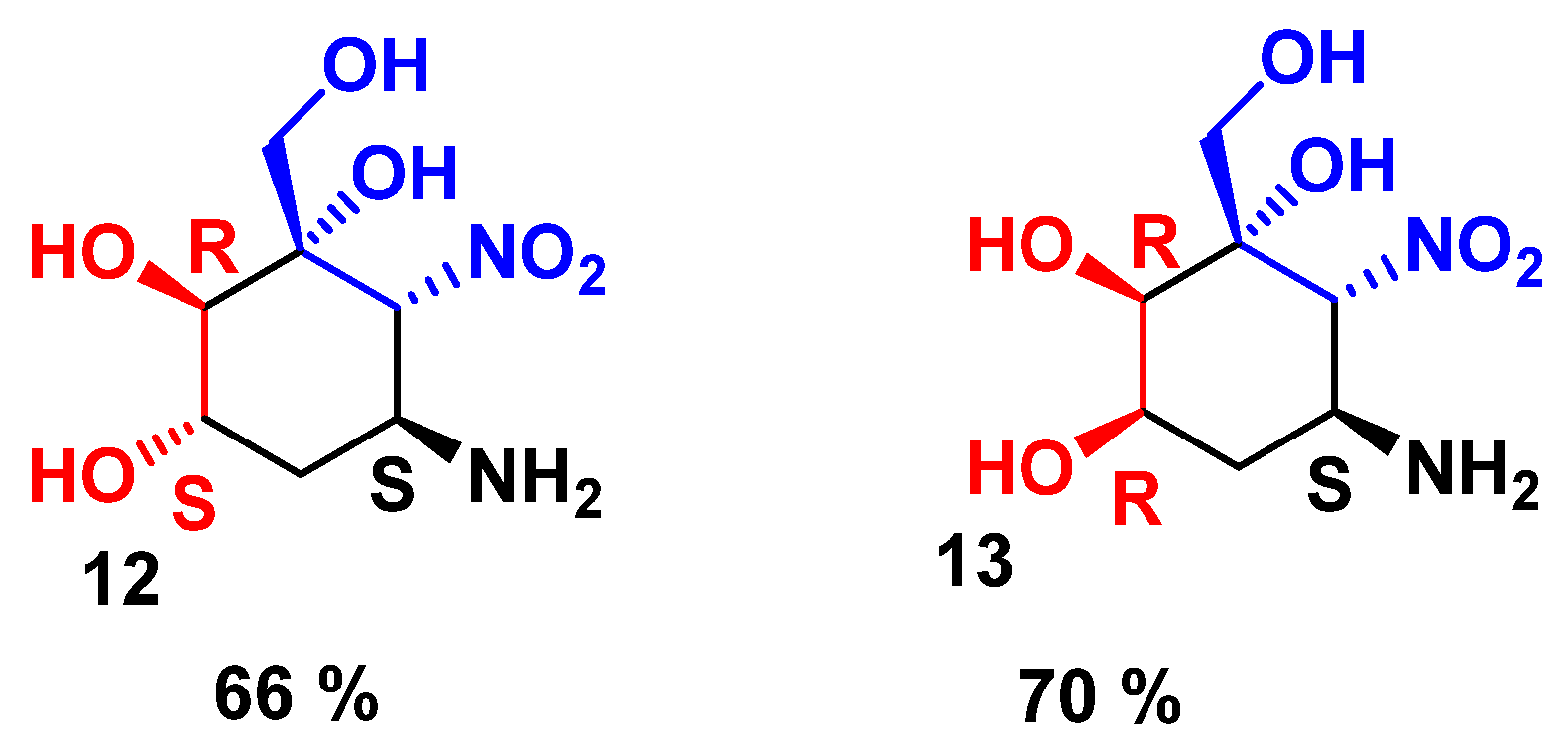

2.3. Preparation of Aminocyclitols

3. Materials and Methods

- 4,4-Diethoxy-1-nitrobut-1-ene (2)

- 3-Azido-1,1-diethoxy-4-nitrobutane (3)

- 4,4-Diethoxy-1-nitrobutan-2-amine (5)

- N-(4,4-Diethoxy-1-nitrobutan-2-yl)acetamide (7)

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Diaz, L.; Delgado, A. Medicinal chemistry of aminocyclitols. Curr. Med. Chem. 2010, 17, 2393–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchek, J.; Adams, D.R.; Hudlicky, T. Chemoenzymatic synthesis of inositols, conduritols, and cyclitol analogues. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 4223–4258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kılbaş, B.; Balci, M. Recent advances in inositol chemistry: Synthesis and applications. Tetrahedron 2011, 67, 2355–2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutaghane, N.; Voutquenne-Nazabadioko, L.; Simon, A.; Harakat, D.; Benlabed, K.; Kabouche, Z. A new triterpenic diester from the aerial parts of Chrysanthemum macrocarpum. Phytochem. Lett. 2013, 6, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanrao, R.; Asokan, A.; Sureshan, K.M. Bio-inspired synthesis of rare and unnatural carbohydrates and cyclitols through strain driven epimerization. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 6707–6710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamci, E. Recent developments concerned with the synthesis of aminocyclitols. Tetrahedron Lett. 2020, 61, 151728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, W.A. Recent progress in the synthesis of six-membered aminocyclitols (2008–2017). Arkivoc 2018, 2018, 231–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Liu, Q.; Liu, J.; Liu, K.; Tian, L.; Duan, M.; Wang, Y.; Shen, Z.; Xu, Y. Selective synthesis of 3-deoxy-5-hydroxy-1-amino-carbasugars as potential α-glucosidase inhibitors. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2019, 17, 5381–5391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, R.; Jiang, C.; Li, H.; Li, W.; Xu, Y. Facile Synthesis of N-Substituted 4-Amino-6-methyl Resorcinols from Polysubstituted Cyclohexanone. Synlett 2017, 28, 1807–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingham, T.W.; Hernandez, L.W.; Olson, D.G.; Svec, R.L.; Hergenrother, P.J.; Sarlah, D. Enantioselective synthesis of isocarbostyril alkaloids and analogs using catalytic dearomative functionalization of benzene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 141, 657–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapero, A.; Egido-Gabas, M.; Bujons, J.; Llebaria, A. Synthesis and evaluation of hydroxymethylaminocyclitols as glycosidase inhibitors. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 80, 3512–3529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schalli, M.; Wolfsgruber, A.; Santana, A.G.; Tysoe, C.; Fischer, R.; Stütz, A.E.; Thonhofer, M.; Withers, S.G. C-5a-substituted validamine type glycosidase inhibitors. Carbohydr. Res. 2017, 440, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, K.R.; Rangari, V.A. Efficient enantiospecific synthesis of ent-conduramine F-1. Tetrahedron 2018, 74, 6689–6693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, S.; Li, K.; Kino, R.; Takeda, T.; Wu, C.-H.; Hiraoka, S.; Nishida, A. Construction of Optically Active Isotwistanes and Aminocyclitols Using Chiral Cyclohexadiene as a Common Intermediate. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2016, 64, 1474–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieber, S.; Carlier, A.; Neuburger, M.; Grabenweger, G.; Eberl, L.; Gademann, K. Isolation and total synthesis of kirkamide, an aminocyclitol from an obligate leaf nodule symbiont. Angew. Chem. 2015, 127, 8079–8081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, N.G.; Eger, E.; Kroutil, W. Building bridges: Biocatalytic C–C-bond formation toward multifunctional products. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 4286–4311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.-H.; Yeom, S.-J.; Kim, S.-E.; Oh, D.-K. Development of aldolase-based catalysts for the synthesis of organic chemicals. Trends Biotechnol. 2022, 40, 306–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clapés, P. Recent Advances in Enzyme-Catalyzed Aldol Addition Reactions. In Green Biocatalysis; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 267–306. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo, J.A.; Guérard-Hélaine, C.; Gutiérrez, M.; Garrabou, X.; Sancelme, M.; Schürmann, M.; Inoue, T.; Hélaine, V.; Charmantray, F.; Gefflaut, T. A mutant D-fructose-6-phosphate aldolase (Ala129Ser) with improved affinity towards dihydroxyacetone for the synthesis of polyhydroxylated compounds. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2010, 352, 1039–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Blidi, L.; Assaf, Z.; Camps Bres, F.; Veschambre, H.; Théry, V.; Bolte, J.; Lemaire, M. Fructose-1, 6-bisphosphate aldolase-mediated synthesis of aminocyclitols (analogues of valiolamine) and their evaluation as glycosidase inhibitors. ChemCatChem 2009, 1, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Blidi, L.; Crestia, D.; Gallienne, E.; Demuynck, C.; Bolte, J.; Lemaire, M. A straightforward synthesis of an aminocyclitol based on an enzymatic aldol reaction and a highly stereoselective intramolecular Henry reaction. Tetrahedron Asymmetry 2004, 15, 2951–2954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Blidi, L.; Ahbala, M.; Bolte, J.; Lemaire, M. Straightforward chemo-enzymatic synthesis of new aminocyclitols, analogues of valiolamine and their evaluation as glycosidase inhibitors. Tetrahedron Asymmetry 2006, 17, 2684–2688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calveras, J.; Egido-Gabás, M.; Gómez, L.; Casas, J.; Parella, T.; Joglar, J.; Bujons, J.; Clapés, P. Dihydroxyacetone phosphate aldolase catalyzed synthesis of structurally diverse polyhydroxylated pyrrolidine derivatives and evaluation of their glycosidase inhibitory properties. Chem.-Eur. J. 2009, 15, 7310–7328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phung, A.N.; Zannetti, M.T.; Whited, G.; Fessner, W.D. Stereospecific biocatalytic synthesis of pancratistatin analogues. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2003, 42, 4821–4824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bres, F.C.; Guérard-Hélaine, C.; Hélaine, V.; Fernandes, C.; Sánchez-Moreno, I.; Traïkia, M.; García-Junceda, E.; Lemaire, M. L-Rhamnulose-1-phosphate and L-fuculose-1-phosphate aldolase mediated multi-enzyme cascade systems for nitrocyclitol synthesis. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2015, 114, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.; Zhuang, W.; Jørgensen, K.A. Asymmetric conjugate addition of azide to α, β-unsaturated nitro compounds catalyzed by cinchona alkaloids. Tetrahedron 2007, 63, 5849–5854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clapés, P.; Fessner, W.-D.; Sprenger, G.A.; Samland, A.K. Recent progress in stereoselective synthesis with aldolases. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2010, 14, 154–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoevaart, R.; Van Rantwijk, F.; Sheldon, R.A. Facile enzymatic aldol reactions with dihydroxyacetone in the presence of arsenate. J. Org. Chem. 2001, 66, 4559–4562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calveras, J.; Casas, J.; Parella, T.; Joglar, J.; Clapés, P. Chemoenzymatic synthesis and inhibitory activities of hyacinthacines A1 and A2 stereoisomers. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2007, 349, 1661–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gijsen, H.J.; Qiao, L.; Fitz, W.; Wong, C.-H. Recent advances in the chemoenzymatic synthesis of carbohydrates and carbohydrate mimetics. Chem. Rev. 1996, 96, 443–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Moreno, I.; García-García, J.F.; Bastida, A.; García-Junceda, E. Multienzyme system for dihydroxyacetone phosphate-dependent aldolase catalyzed C–C bond formation from dihydroxyacetone. Chem. Commun. 2004, 14, 1634–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Enzyme | Donor | Substrate (Aldehyde) | Results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yield (%) | Aminocyclitols Ratio | ||||

| Muted FSA | DHA | 6 | NR | ||

| 8 | Traces | ||||

| FBA | DHAP | 6 | NR | ||

| 8 | Traces | ||||

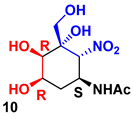

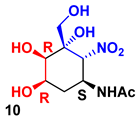

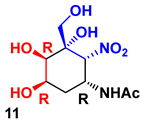

| R1PA | DHAP | 8 | 62% |  45 |  55 |

| F1PA | DHAP | 8 | 59% |  90 |  10 |

| Enzyme | Temperature °C | pH | Substrate | Results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 h | 18 h | 48 h | ||||

| Penicillin amidase | 37 | 7.6 | 9 | NR 1 | LR | LR |

| 10 | ||||||

| Acylase I | 25 | 7.0 | 9 | NR | NR | NR |

| 10 | ||||||

| Hydantoinase | 40 | 9.0 | 9 | NR | LR | LR |

| 10 | ||||||

| Papain | 25 | 6.2 | 9 | LR 2 | SR 3 | TR 4 |

| 10 | ||||||

| Chymopapain | 25 | 6.2 | 9 | NR | LR | LR |

| 10 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

El Blidi, L.; Lemaire, M.; Wazeer, I.; Alrashed, M.M.; El-Harbawi, M. Straightforward Chemo-Multi-Enzymatic Cascade Systems for the Stereo-Controlled Synthesis of 5-Amino-6-nitrocyclitols. Catalysts 2026, 16, 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020144

El Blidi L, Lemaire M, Wazeer I, Alrashed MM, El-Harbawi M. Straightforward Chemo-Multi-Enzymatic Cascade Systems for the Stereo-Controlled Synthesis of 5-Amino-6-nitrocyclitols. Catalysts. 2026; 16(2):144. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020144

Chicago/Turabian StyleEl Blidi, Lahssen, Marielle Lemaire, Irfan Wazeer, Maher M. Alrashed, and Mohanad El-Harbawi. 2026. "Straightforward Chemo-Multi-Enzymatic Cascade Systems for the Stereo-Controlled Synthesis of 5-Amino-6-nitrocyclitols" Catalysts 16, no. 2: 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020144

APA StyleEl Blidi, L., Lemaire, M., Wazeer, I., Alrashed, M. M., & El-Harbawi, M. (2026). Straightforward Chemo-Multi-Enzymatic Cascade Systems for the Stereo-Controlled Synthesis of 5-Amino-6-nitrocyclitols. Catalysts, 16(2), 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020144