Enhanced Photocatalytic Degradation of Ciprofloxacin Under Natural Sunlight Using a Waste-Derived Carbon Dots–TiO2 Nanocomposite

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Description of the Photocatalyst and Prior Characterization

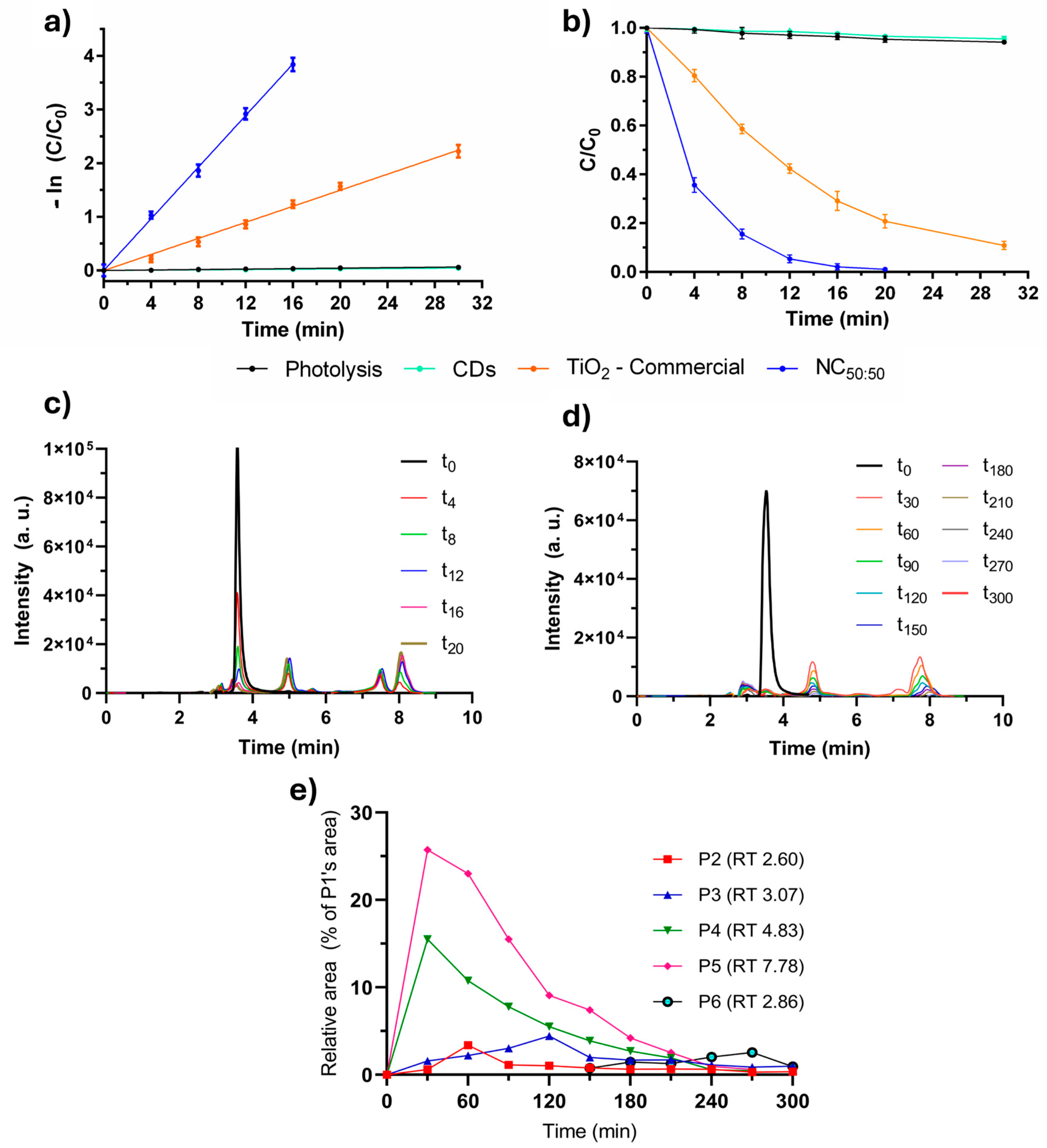

2.2. Photocatalytic Optimization and Assays

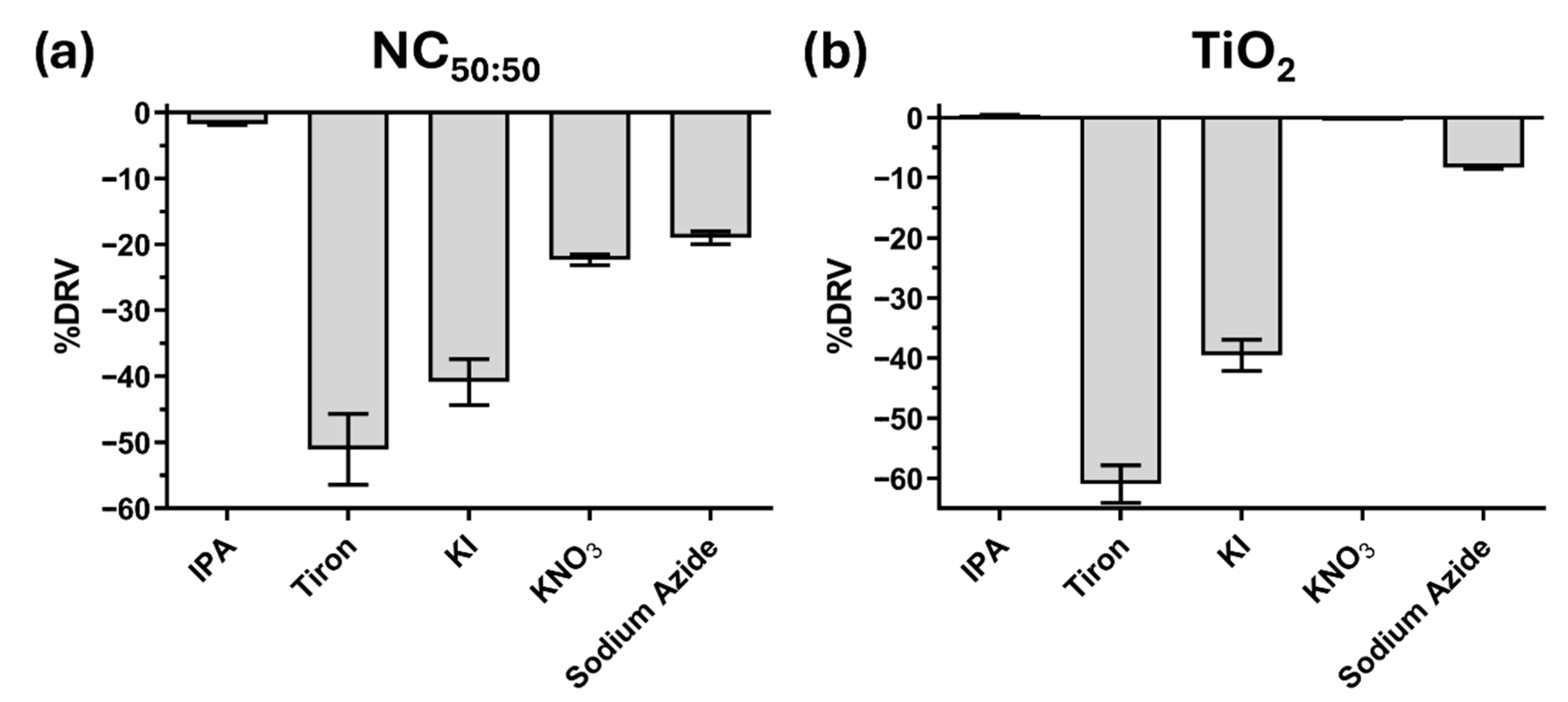

2.3. Scavenger Assays

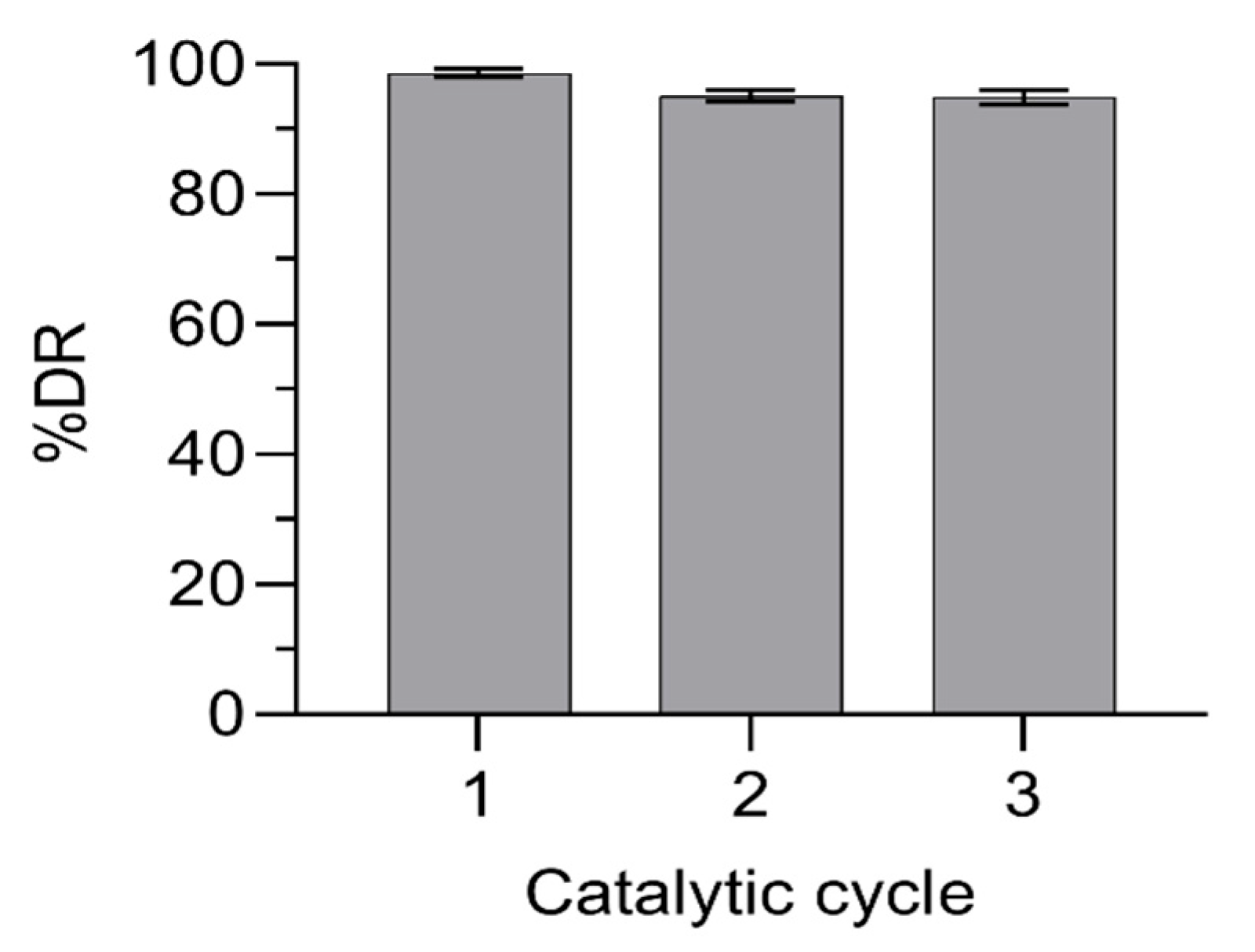

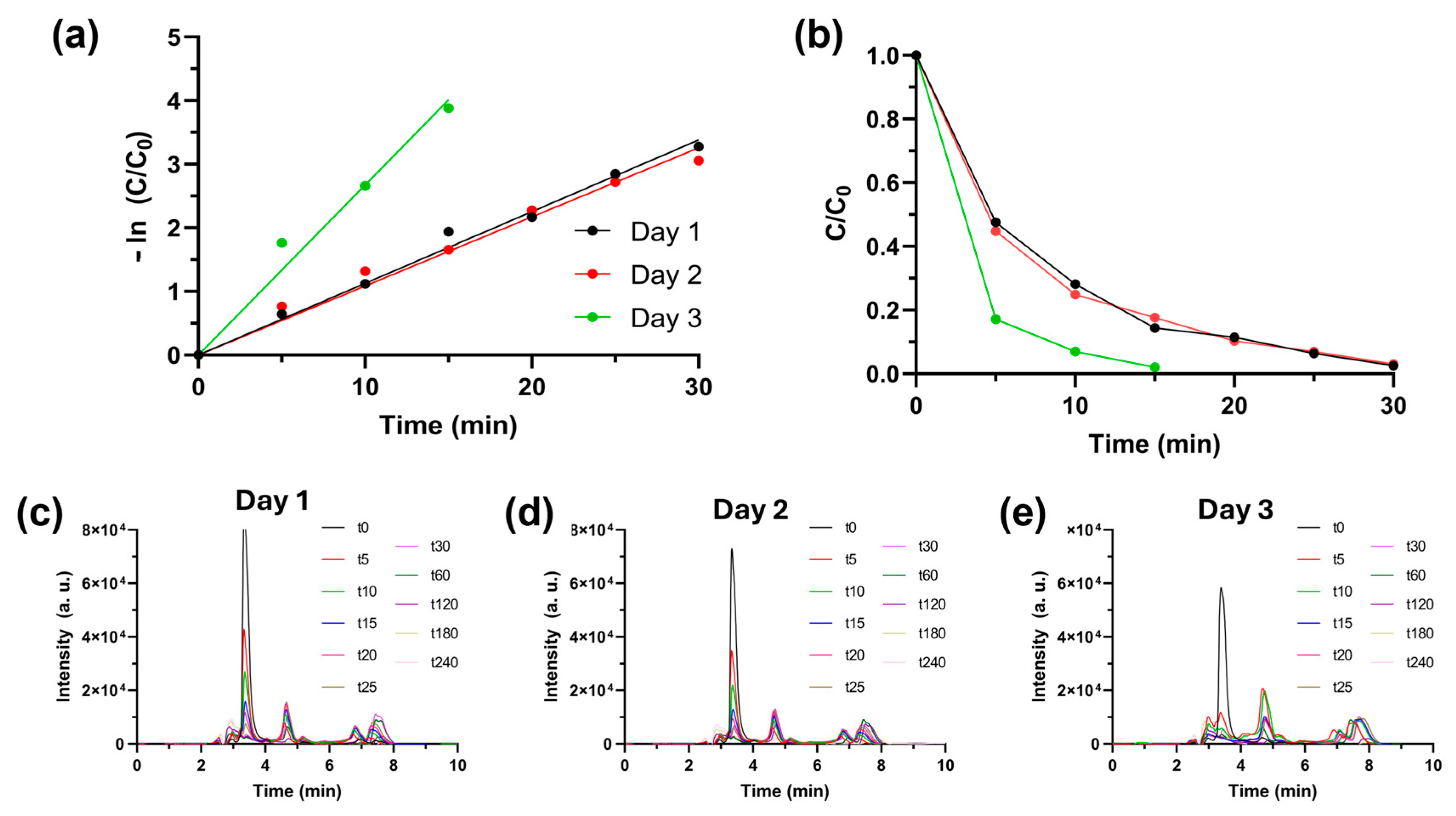

2.4. Recycling Studies

2.5. Comparison to the Literature

| Photocatalyst | Cat. (g L−1) | CIP Conc. (ppm) | Lamp | k (min−1) | % In(C) | DOI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TiO2/CDs NC50:50 | 0.6 | 20 | Solar simulator | 0.2372 | This work | |

| Glass-deposited TiO2 | 0.13 | 20 | 365 nm 10 mW/cm2 | 0.0085 | 2691 | [63] |

| Graphitized carbon-TiO2 | 0.35 | 15 | 254 nm 14 W | 0.102 | 133 | [64] |

| Glass-deposited TiO2 | 1 | 3 | UV | 0.0197 | 1104 | [65] |

| TiO2 NPs | 0.7 | 80 | 3 × 254 nm 8 W | 0.00439 | 5303 | [66] |

| TiO2/SnO2 | 1 | 2.5 | 3 × 253 nm 35 W | 0.0311 | 663 | [67] |

| TiO2/CDs6 wt% | 1 | 10 | Xe Arc 350 W 290 Filter | 0.129 | 84 | [68] |

| TiO2/H2O2 | 0.5 | 9 | Solar 800 W Xe lamp | 0.022 | 978 | [69] |

| TiO2/WO3 | 0.5 | 20 | Sunlight | 0.034 | 598 | [70] |

2.6. Photocatalysis Under Natural Sunlight

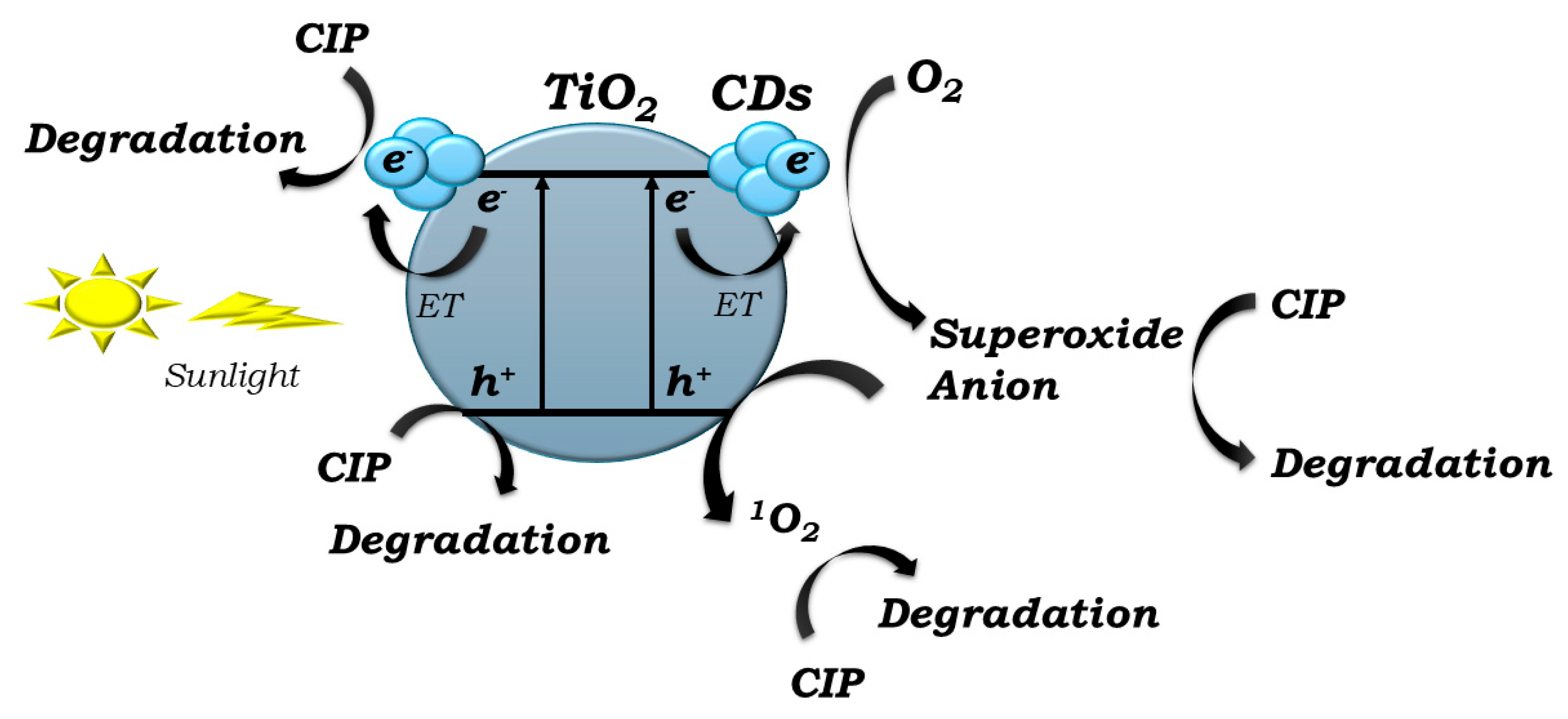

2.7. Photocatalytic Mechanism

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Preparation of CDs

3.2. TiO2/CDs Nanocomposites Preparation

3.3. Photocatalytic Activity Assays

3.4. Scavenger Assays

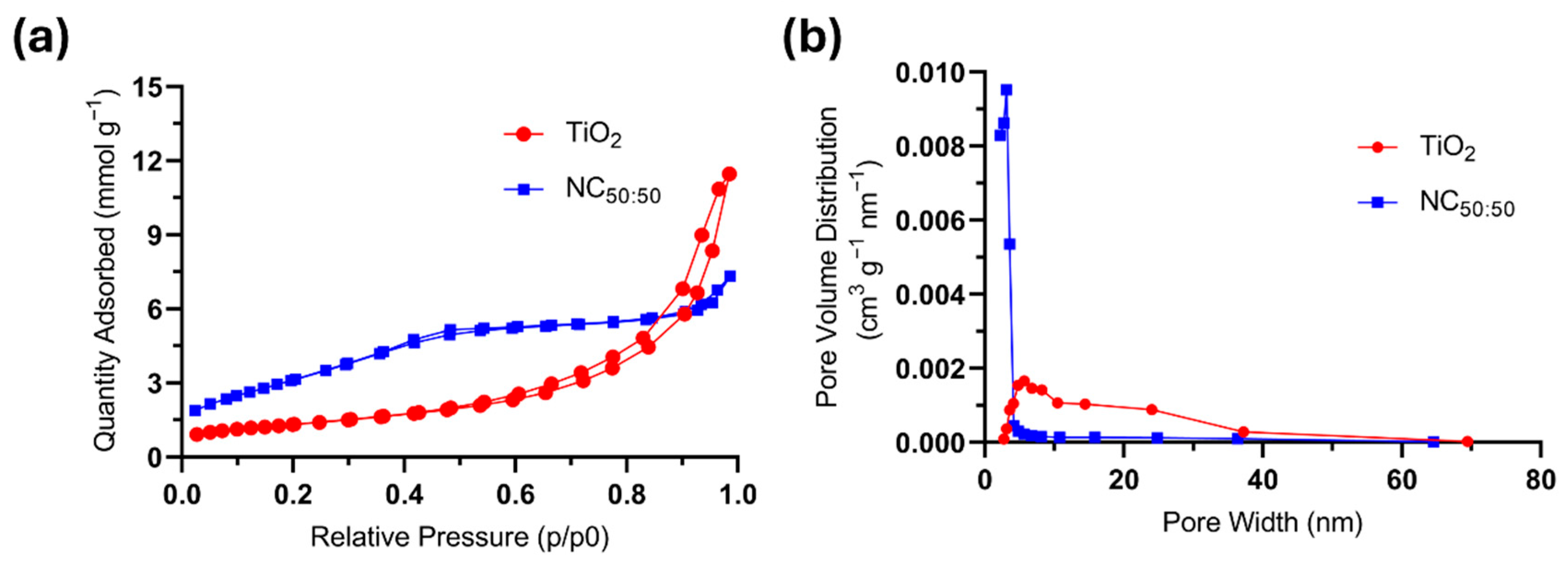

3.5. BET Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Akhil, D.; Lakshmi, D.; Senthil Kumar, P.; Vo, D.-V.N.; Kartik, A. Occurrence and removal of antibiotics from industrial wastewater. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 1477–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayaz, T.; Renuka, N.; Ratha, S.K. Antibiotic occurrence, environmental risks, and their removal from aquatic environments using microalgae: Advances and future perspectives. Chemosphere 2024, 349, 140822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batt, A.L.; Bruce, I.B.; Aga, D.S. Evaluating the vulnerability of surface waters to antibiotic contamination from varying wastewater treatment plant discharges. Environ. Pollut. 2006, 142, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Lu, S.; Guo, W.; Xi, B.; Wang, W. Antibiotics in the aquatic environments: A review of lakes, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 627, 1195–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Mozaz, S.; Vaz-Moreira, I.; Varela Della Giustina, S.; Llorca, M.; Barcelo, D.; Schubert, S.; Berendonk, T.U.; Michael-Kordatou, I.; Fatta-Kassinos, D.; Martinez, J.L.; et al. Antibiotic residues in final effluents of European wastewater treatment plants and their impact on the aquatic environment. Environ. Int. 2020, 140, 105733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wei, Y.; Lan, F.; Wang, R.; Yang, Y.; Chen, J. Research progress and trend of antibiotics degradation by electroactive biofilm: A review. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 58, 104846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Yu, F.; Li, Z.; Zhan, J. Occurrence, distribution, and ecological risk assessment of pharmaceuticals and personal care products in the surface water of the middle and lower reaches of the Yellow River (Henan section). J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 443, 130369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, M.; Chu, L.M. Occurrence of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes in soils from wastewater irrigation areas in the Pearl River Delta region, southern China. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 624, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salam, M.A.; Al-Amin, M.Y.; Salam, M.T.; Pawar, J.S.; Akhter, N.; Rabaan, A.A.; Alqumber, M.A.A. Antimicrobial Resistance: A Growing Serious Threat for Global Public Health. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S.; Bal, M.; Pati, S.; Rana, R.; Dixit, S.; Ranjit, M. Antibiotic resistance in toxigenic E. coli: A severe threat to global health. Discov. Med. 2024, 1, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltzer, P.M.; Lajmanovich, R.C.; Attademo, A.M.; Junges, C.M.; Teglia, C.M.; Martinuzzi, C.; Curi, L.; Culzoni, M.J.; Goicoechea, H.C. Ecotoxicity of veterinary enrofloxacin and ciprofloxacin antibiotics on anuran amphibian larvae. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2017, 51, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.F.; Liu, X.; Zhang, S.; Pan, B.; Liu, M.L. Ciprofloxacin derivatives and their antibacterial activities. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 146, 599–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansón-Casaos, A.; Hernández-Ferrer, J.; Vallan, L.; Xie, H.; Lira-Cantú, M.; Benito, A.M.; Maser, W.K. Functionalized carbon dots on TiO2 for perovskite photovoltaics and stable photoanodes for water splitting. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 12180–12191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, R.; Saini, D.; Sonkar, S.K.; Sonker, A.K.; Westman, G. Sunlight promoted removal of toxic hexavalent chromium by cellulose derived photoactive carbon dots. Chemosphere 2022, 287, 132287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendão, R.M.S.; Algarra, M.; Ribeiro, E.; Pereira, M.; Gil, A.; Vale, N.; Esteves da Silva, J.C.G.; Pinto da Silva, L. Carbon Dots–TiO2 Nanocomposites for the Enhanced Visible-Light Driven Photodegradation of Methylene Blue. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 2023, 8, 2300317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendão, R.M.S.; Algarra, M.; Lázaro-Martínez, J.; Brandão, A.T.S.C.; Gil, A.; Pereira, C.; Esteves da Silva, J.C.G.; Pinto da Silva, L. Visible-light-driven photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes using a TiO2 and waste-based carbon dots nanocomposite. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2025, 713, 136475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Li, M.; Liao, L.; Guo, L.; Liu, H.; Wang, B.; Li, Z. High-Crystallinity BiOCl Nanosheets as Efficient Photocatalysts for Norfloxacin Antibiotic Degradation. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Ahmed, A.; Sharma, A.; Sharma, C.; Paul, S.; Khosla, A.; Gupta, V.; Arya, S. Promising photocatalytic degradation of methyl orange dye via sol-gel synthesized Ag–CdS@Pr-TiO2 core/shell nanoparticles. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2021, 616, 413121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthik, K.V.; Raghu, A.V.; Reddy, K.R.; Ravishankar, R.; Sangeeta, M.; Shetti, N.P.; Reddy, C.V. Green synthesis of Cu-doped ZnO nanoparticles and its application for the photocatalytic degradation of hazardous organic pollutants. Chemosphere 2022, 287, 132081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koedsiri, Y.; Amornpitoksuk, P.; Randorn, C.; Rattana, T.; Tandorn, S.; Suwanboon, S. S-Schematic CuWO4/ZnO nanocomposite boosted photocatalytic degradation of organic dye pollutants. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2024, 177, 108385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khedr, T.M.; El-Sheikh, S.M.; Ismail, A.A.; Bahnemann, D.W. Highly efficient solar light-assisted TiO2 nanocrystalline for photodegradation of ibuprofen drug. Opt. Mater. 2019, 88, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, W.; Ai, Z.; Jia, F.; Zhang, L.; Fan, X.; Zou, Z. Low temperature preparation and visible light photocatalytic activity of mesoporous carbon-doped crystalline TiO2. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2007, 69, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barolet, D.; Christiaens, F.; Hamblin, M.R. Infrared and skin: Friend or foe. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2016, 155, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daghrir, R.; Drogui, P.; Robert, D. Photoelectrocatalytic technologies for environmental applications. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2012, 238, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Zeng, G.; Tang, L.; Fan, C.; Zhang, C.; He, X.; He, Y. An overview on limitations of TiO2-based particles for photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants and the corresponding countermeasures. Water Res. 2015, 79, 128–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Mragui, A.; Zegaoui, O.; Esteves da Silva, J.C.G. Elucidation of the photocatalytic degradation mechanism of an azo dye under visible light in the presence of cobalt doped TiO2 nanomaterials. Chemosphere 2021, 266, 128931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslami, A.; Amini, M.M.; Yazdanbakhsh, A.R.; Mohseni-Bandpei, A.; Safari, A.A.; Asadi, A. N,S co-doped TiO2 nanoparticles and nanosheets in simulated solar light for photocatalytic degradation of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in water: A comparative study. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2016, 91, 2693–2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Wang, W.; Liu, D.; Zhu, Q.; Jia, J.; Tian, J.; Li, Z.; Wang, X.; Xing, Z. Oxygen vacancy-mediated sandwich-structural TiO(2-x)/ultrathin g-C(3)N(4)/TiO(2-x) direct Z-scheme heterojunction visible-light-driven photocatalyst for efficient removal of high toxic tetracycline antibiotics. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 408, 124432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Khare, P.; Verma, S.; Bhati, A.; Sonker, A.K.; Tripathi, K.M.; Sonkar, S.K. Pollutant Soot for Pollutant Dye Degradation: Soluble Graphene Nanosheets for Visible Light Induced Photodegradation of Methylene Blue. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 8860–8869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, D.; Jiao, J.; Li, Z.; Guo, Y.; Feng, C.; Liu, Y.; Wang, L.; Wu, M. Efficient Separation of Electron–Hole Pairs in Graphene Quantum Dots by TiO2 Heterojunctions for Dye Degradation. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2015, 3, 2405–2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wu, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhao, J.; Jin, F.; Na, P. Carbon dots-TiO2 nanosheets composites for photoreduction of Cr(VI) under sunlight illumination: Favorable role of carbon dots. Appl. Catal. B 2018, 224, 508–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Lu, K.-Q.; Tang, Z.-R.; Xu, Y.-J. Recent progress in carbon quantum dots: Synthesis, properties and applications in photocatalysis. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 3717–3734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendao, R.M.S.; Crista, D.M.A.; Afonso, A.C.P.; Martinez de Yuso, M.D.V.; Algarra, M.; Esteves da Silva, J.C.G.; Pinto da Silva, L. Insight into the hybrid luminescence showed by carbon dots and molecular fluorophores in solution. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019, 21, 20919–20926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vale, N.; Silva, S.; Duarte, D.; Crista, D.M.A.; Pinto da Silva, L.; Esteves da Silva, J.C.G. Normal breast epithelial MCF-10A cells to evaluate the safety of carbon dots. RSC Med. Chem. 2021, 12, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Chen, M.; Chen, G.; Zou, W.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, Q. Visible-Ultraviolet Upconversion Carbon Quantum Dots for Enhancement of the Photocatalytic Activity of Titanium Dioxide. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 4247–4254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crista, D.M.A.; Mello, G.P.C.; Shevchuk, O.; Sendao, R.M.S.; Simoes, E.F.C.; Leitao, J.M.M.; da Silva, L.P.; Esteves da Silva, J.C.G. 3-Hydroxyphenylboronic Acid-Based Carbon Dot Sensors for Fructose Sensing. J. Fluoresc. 2019, 29, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.; Liu, C.; Li, Y.; Chen, M.; Zheng, Y.; Tian, H.; Shi, R.; He, X.; Lin, X. Preparation of Multicolour Solid Fluorescent Carbon Dots for Light-Emitting Diodes Using Phenylethylamine as a Co-Carbonization Agent. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, T.; Liu, T.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, M. Carbon dots with intrinsic theranostic properties for photodynamic therapy of oral squamous cell carcinoma. J. Biomater. Appl. 2022, 37, 850–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Li, X.; Luo, M.; Chen, M.; Chen, W.; Yang, P.; Zhou, X. Synthesis of carbon dots with high photocatalytic reactivity by tailoring heteroatom doping. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 605, 330–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendão, R.M.S.; Esteves da Silva, J.C.G.; Pinto da Silva, L. Applications of Fluorescent Carbon Dots as Photocatalysts: A Review. Catalysts 2023, 13, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendao, R.M.S.; Esteves da Silva, J.C.G.; Pinto da Silva, L. Photocatalytic removal of pharmaceutical water pollutants by TiO2—Carbon dots nanocomposites: A review. Chemosphere 2022, 301, 134731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbanna, O.; Zhang, P.; Fujitsuka, M.; Majima, T. Facile preparation of nitrogen and fluorine codoped TiO2 mesocrystal with visible light photocatalytic activity. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2016, 192, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Leng, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Xia, Y.; Sang, Y.; Hao, P.; Zhan, J.; Li, M.; Liu, H. Carbon quantum dots/hydrogenated TiO2 nanobelt heterostructures and their broad spectrum photocatalytic properties under UV, visible, and near-infrared irradiation. Nano Energy 2015, 11, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Zhang, B.; Jiang, Z.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, Y. Room-Temperature Synthesis of Carbon Dot/TiO2 Composites with High Photocatalytic Activity. Langmuir 2023, 39, 7184–7191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saini, D.; Garg, A.K.; Dalal, C.; Anand, S.R.; Sonkar, S.K.; Sonker, A.K.; Westman, G. Visible-Light-Promoted Photocatalytic Applications of Carbon Dots: A Review. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2022, 5, 3087–3109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crista, D.M.A.; Esteves da Silva, J.C.G.; Pinto da Silva, L. Evaluation of Different Bottom-up Routes for the Fabrication of Carbon Dots. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sendão, R.; Yuso, M.d.V.M.d.; Algarra, M.; Esteves da Silva, J.C.G.; Pinto da Silva, L. Comparative life cycle assessment of bottom-up synthesis routes for carbon dots derived from citric acid and urea. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 254, 120080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, S.; Esteves da Silva, J.C.G.; Pinto da Silva, L. Comparative life cycle assessment of high-yield synthesis routes for carbon dots. NanoImpact 2021, 23, 100332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Cui, Y.; Sun, X.; Wang, H.; Teng, X. Corn stover biochar increased edible safety of spinach by reducing the migration of mercury from soil to spinach. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 758, 143883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, I.M.F.; Cardoso, R.M.F.; Pinto da Silva, L.; Esteves da Silva, J.C.G. UV-Based Advanced Oxidation Processes of Remazol Brilliant Blue R Dye Catalyzed by Carbon Dots. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajender, G.; Kumar, J.; Giri, P.K. Interfacial charge transfer in oxygen deficient TiO2-graphene quantum dot hybrid and its influence on the enhanced visible light photocatalysis. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2018, 224, 960–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, E.P.; Joyner, L.G.; Halenda, P.P. The Determination of Pore Volume and Area Distributions in Porous Substances. I. Computations from Nitrogen Isotherms. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2002, 73, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, Q.; He, H.; Shi, F.; Huang, G.; Xing, B.; Jia, J.; Zhang, C. Coal tar pitch as natural carbon quantum dots decorated on TiO2 for visible light photodegradation of rhodamine B. Carbon 2019, 152, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milojković, N.; Simović, B.; Žunić, M.; Radovanović, L.; Prekajski-Đorđević, M.; Dapčević, A. Modified Z-scheme heterojunction of TiO2/polypyrrole recyclable photocatalyst. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2025, 108, e20431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorathiya, K.; Mishra, B.; Kalarikkal, A.; Reddy, K.P.; Gopinath, C.S.; Khushalani, D. Enhancement in Rate of Photocatalysis Upon Catalyst Recycling. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 35075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, I.M.A.; Hossam, G.; Shaker, A.M.; Nassr, L.A.E. Surface functionalization of TiO2 nanoparticles with hydrophobic tridentate Schiff base for a promising photocatalytic reduction of toxic Cr(VI) in aqueous solutions. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 16005–16016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escareno-Torres, G.A.; Pinedo-Escobar, J.A.; De Haro-Del Rio, D.A.; Becerra-Castaneda, P.; Araiza, D.G.; Inchaurregui-Mendez, H.; Carrillo-Martinez, C.J.; Gonzalez-Rodriguez, L.M. Enhanced degradation of ciprofloxacin in water using ternary photocatalysts TiO2/SnO2/g-C3N4 under UV, visible, and solar light. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 40174–40189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Kuate, L.J.N.; Zhang, H.; Hou, J.; Wen, H.; Lu, C.; Li, C.; Shi, W. Photothermally enabled black g-C3N4 hydrogel with integrated solar-driven evaporation and photo-degradation for efficient water purification. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 355, 129751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Sun, L.; Hao, P.; Zhang, S.; Shen, Y.; Hou, J.; Guo, F.; Li, C.; Shi, W. Construction of black g-C3N4/loofah/chitosan hydrogel as an efficient solar evaporator for desalination coupled with antibiotic degradation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 355, 129615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Hao, C.; Shi, Y.; Guo, F.; Tang, Y. Effect of different carbon dots positions on the transfer of photo-induced charges in type I heterojunction for significantly enhanced photocatalytic activity. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 304, 122337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Sun, W.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, K.; Sun, H.; Lin, X.; Hong, Y.; Guo, F. A self-sufficient photo-Fenton system with coupling in-situ production H2O2 of ultrathin porous g-C3N4 nanosheets and amorphous FeOOH quantum dots. J. Hazard Mater. 2022, 436, 129141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Sun, H.; Chen, K.; Zhang, Y.; Shan, P.; Shi, W.; Guo, F. Nanodiamonds decorated yolk-shell ZnFe2O4 sphere as magnetically separable and recyclable composite for boosting antibiotic degradation performance. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2023, 54, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triquet, T.; Tendero, C.; Latapie, L.; Manero, M.-H.; Richard, R.; Andriantsiferana, C. TiO2 MOCVD coating for photocatalytic degradation of ciprofloxacin using 365 nm UV LEDs—Kinetics and mechanisms. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 104544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Xu, S.; Wang, Y.; Sun, X.; Gao, Y.; Gao, B. Enhanced degradation of ciprofloxacin by graphitized mesoporous carbon (GMC)-TiO2 nanocomposite: Strong synergy of adsorption-photocatalysis and antibiotics degradation mechanism. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2018, 527, 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malakootian, M.; Nasiri, A.; Amiri Gharaghani, M. Photocatalytic degradation of ciprofloxacin antibiotic by TiO2 nanoparticles immobilized on a glass plate. Chem. Eng. Commun. 2019, 207, 56–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, S.; Islam, M.S.; Kabir, M.H.; Shaikh, M.A.A.; Gafur, M.A. UV/TiO2 photodegradation of metronidazole, ciprofloxacin and sulfamethoxazole in aqueous solution: An optimization and kinetic study. Arab. J. Chem. 2022, 15, 103900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, L.N.; Nobre, F.X.; Lobo, A.O.; de Matos, J.M.E. Photodegradation of ciprofloxacin using Z-scheme TiO2/SnO2 nanostructures as photocatalyst. Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag. 2021, 16, 100466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Chen, D.; Chen, T.; Cai, M.; Zhang, Q.; Xie, Z.; Li, R.; Xiao, Z.; Liu, G.; Lv, W. Study on heterogeneous photocatalytic ozonation degradation of ciprofloxacin by TiO2/carbon dots: Kinetic, mechanism and pathway investigation. Chemosphere 2019, 227, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Guo, C.; Su, B.; Xu, J. Photodegradation of four fluoroquinolone compounds by titanium dioxide under simulated solar light irradiation. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2012, 87, 643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghni, N.; Boutoumi, H.; Khalaf, H.; Makaoui, N.; Colón, G. Enhanced photocatalytic activity of TiO2/WO3 nanocomposite from sonochemical-microwave assisted synthesis for the photodegradation of ciprofloxacin and oxytetracycline antibiotics under UV and sunlight. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2022, 428, 113848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, A.M.; Gracia-Pinilla, M.A.; Pillai, S.C.; O’Shea, K. UV and Visible Light-Driven Production of Hydroxyl Radicals by Reduced Forms of N, F, and P Codoped Titanium Dioxide. Molecules 2019, 24, 2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parnicka, P.; Mazierski, P.; Grzyb, T.; Lisowski, W.; Kowalska, E.; Ohtani, B.; Zaleska-Medynska, A.; Nadolna, J. Influence of the preparation method on the photocatalytic activity of Nd-modified TiO2. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2018, 9, 447–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Pelaez, M.; Dionysiou, D.D.; Pillai, S.C.; Byrne, J.A.; O’Shea, K.E. UV and visible light activated TiO2 photocatalysis of 6-hydroxymethyl uracil, a model compound for the potent cyanotoxin cylindrospermopsin. Catal. Today 2014, 224, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, M.; Kong, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Wang, B.; Fan, P. Spectroscopic analyses on ROS generation catalyzed by TiO2, CeO2/TiO2 and Fe2O3/TiO2 under ultrasonic and visible-light irradiation. Spectrochim. Acta Part A 2013, 101, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Cheng, C.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Jin, X.; Li, K.; Kang, P.; Gao, J. Detection of reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated by TiO2(R), TiO2(R/A) and TiO2(A) under ultrasonic and solar light irradiation and application in degradation of organic dyes. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 192, 786–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, M.R.; Martin, S.T.; Choi, W.; Bahnemann, D.W. Environmental Applications of Semiconductor Photocatalysis. Chem. Rev. 2002, 95, 69–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, S.; Zhou, J.; Ding, L.; Zhou, C.; Liu, Y.; Li, S.; Meng, J.; Zhu, S.; Chatterjee, S.; Liang, F. Preparation of carbon quantum dots/TiO2 composite and application for enhanced photodegradation of rhodamine B. Colloids Surf. A 2022, 648, 129342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Cao, L.; Lu, F.; Meziani, M.J.; Li, H.; Qi, G.; Zhou, B.; Harruff, B.A.; Kermarrec, F.; Sun, Y.P. Photoinduced electron transfers with carbon dots. Chem. Commun. 2009, 25, 3774–3776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Ahmad, N.; Zeng, G.; Ray, A.; Zhang, Y. N, S co-doped carbon quantum dots/TiO2 composite for visible-light-driven photocatalytic reduction of Cr (VI). J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 108742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Z.; Hu, J.; Li, S.; Wang, Z.; Liu, J.; Wang, X. Semiconductor heterojunction photocatalysts: Design, construction, and photocatalytic performances. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 5234–5244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nosaka, Y.; Daimon, T.; Nosaka, A.Y.; Murakami, Y. Singlet oxygen formation in photocatalytic TiO2 aqueous suspension. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2004, 6, 2917–2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, S.; Algarra, M.; Gil, A.; Esteves da Silva, J.; Pinto da Silva, L. Development of a Facile and Green Synthesis Strategy for Brightly Fluorescent Carbon Dots from Various Waste Materials. ChemSusChem 2025, 18, e202401702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Mragui, A.; Daou, I.; Zegaoui, O. Influence of the preparation method and ZnO/(ZnO + TiO2) weight ratio on the physicochemical and photocatalytic properties of ZnO-TiO2 nanomaterials. Catal. Today 2019, 321–322, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Mragui, A.; Logvina, Y.; Pinto da Silva, L.; Zegaoui, O.; Esteves da Silva, J.C.G. Synthesis of Fe- and Co-Doped TiO2 with Improved Photocatalytic Activity Under Visible Irradiation Toward Carbamazepine Degradation. Materials 2019, 12, 3874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farjadfar, S.; Ghiaci, M.; Kulinch, S.A.; Wunderlich, W. Efficient photocatalyst for the degradation of cationic and anionic dyes prepared via modification of carbonized mesoporous TiO2 by encapsulation of carbon dots. Mater. Res. Bull. 2022, 155, 111963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liubimovskii, S.O.; Ustynyuk, L.Y.; Tikhonov, A.N. Superoxide radical scavenging by sodium 4,5-dihydroxybenzene-1,3-disulfonate dissolved in water: Experimental and quantum chemical studies. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 333, 115810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastina, B.; LaVerne, J.A.; Pimblott, S.M. Dependence of Molecular Hydrogen Formation in Water on Scavengers of the Precursor to the Hydrated Electron. J. Phys. Chem. A 1999, 103, 5841–5846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bancirova, M. Sodium azide as a specific quencher of singlet oxygen during chemiluminescent detection by luminol and Cypridina luciferin analogues. Luminescence 2011, 26, 685–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Test | Parameter Value | k (min−1) | %DR | Time (min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CIP concentration | 10 ppm | 0.0823 | 96.4 | 40 |

| 20 ppm | 0.0537 | 96.2 | 60 | |

| 30 ppm | 0.0200 | 69.7 | 60 | |

| pH level | 5 | 0.0256 | 78.5 | 60 |

| 7 | 0.0828 | 99.1 | 60 | |

| 9 | 0.0765 | 98.8 | 60 | |

| Catalyst dosage | 10 mg | 0.0218 | 73.4 | 60 |

| 20 mg | 0.0763 | 99.1 | 60 | |

| 40 mg | 0.1114 | 98.0 | 40 | |

| 60 mg | 0.2372 | 98.2 | 16 |

| Sample | SBET (m2 g−1) | Vtotal (cm3 g−1) | Dp (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| TiO2 | 105.2 | 0.276 | 13.1 |

| NC50:50 | 269.9 | 0.212 | 4.1 |

| Day | Time Period | Temperature Range | UV Index | Conditions | %DR | Time to ~100%DR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 23 August 2024 | 11.00 to 15.00 | 30–32 °C | 8 | Sunny | ~100% | 30 min |

| 24 August 2024 | 11.00 to 15.00 | 26–29 °C | 8 | Clouded | ~100% | 30 min |

| 25 August 2024 | 11.00 to 15.00 | 23–26 °C | 9 | Clouded | ~100% | 15 min |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sendão, R.M.S.; Brandão, A.T.S.C.; Pereira, C.M.; Esteves da Silva, J.C.G.; Pinto da Silva, L. Enhanced Photocatalytic Degradation of Ciprofloxacin Under Natural Sunlight Using a Waste-Derived Carbon Dots–TiO2 Nanocomposite. Catalysts 2026, 16, 142. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020142

Sendão RMS, Brandão ATSC, Pereira CM, Esteves da Silva JCG, Pinto da Silva L. Enhanced Photocatalytic Degradation of Ciprofloxacin Under Natural Sunlight Using a Waste-Derived Carbon Dots–TiO2 Nanocomposite. Catalysts. 2026; 16(2):142. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020142

Chicago/Turabian StyleSendão, Ricardo M. S., Ana T. S. C. Brandão, Carlos M. Pereira, Joaquim C. G. Esteves da Silva, and Luís Pinto da Silva. 2026. "Enhanced Photocatalytic Degradation of Ciprofloxacin Under Natural Sunlight Using a Waste-Derived Carbon Dots–TiO2 Nanocomposite" Catalysts 16, no. 2: 142. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020142

APA StyleSendão, R. M. S., Brandão, A. T. S. C., Pereira, C. M., Esteves da Silva, J. C. G., & Pinto da Silva, L. (2026). Enhanced Photocatalytic Degradation of Ciprofloxacin Under Natural Sunlight Using a Waste-Derived Carbon Dots–TiO2 Nanocomposite. Catalysts, 16(2), 142. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020142