Membranes for Electrochemical Carbon Dioxide Conversion to Multi-Carbon Products

Abstract

1. Introduction

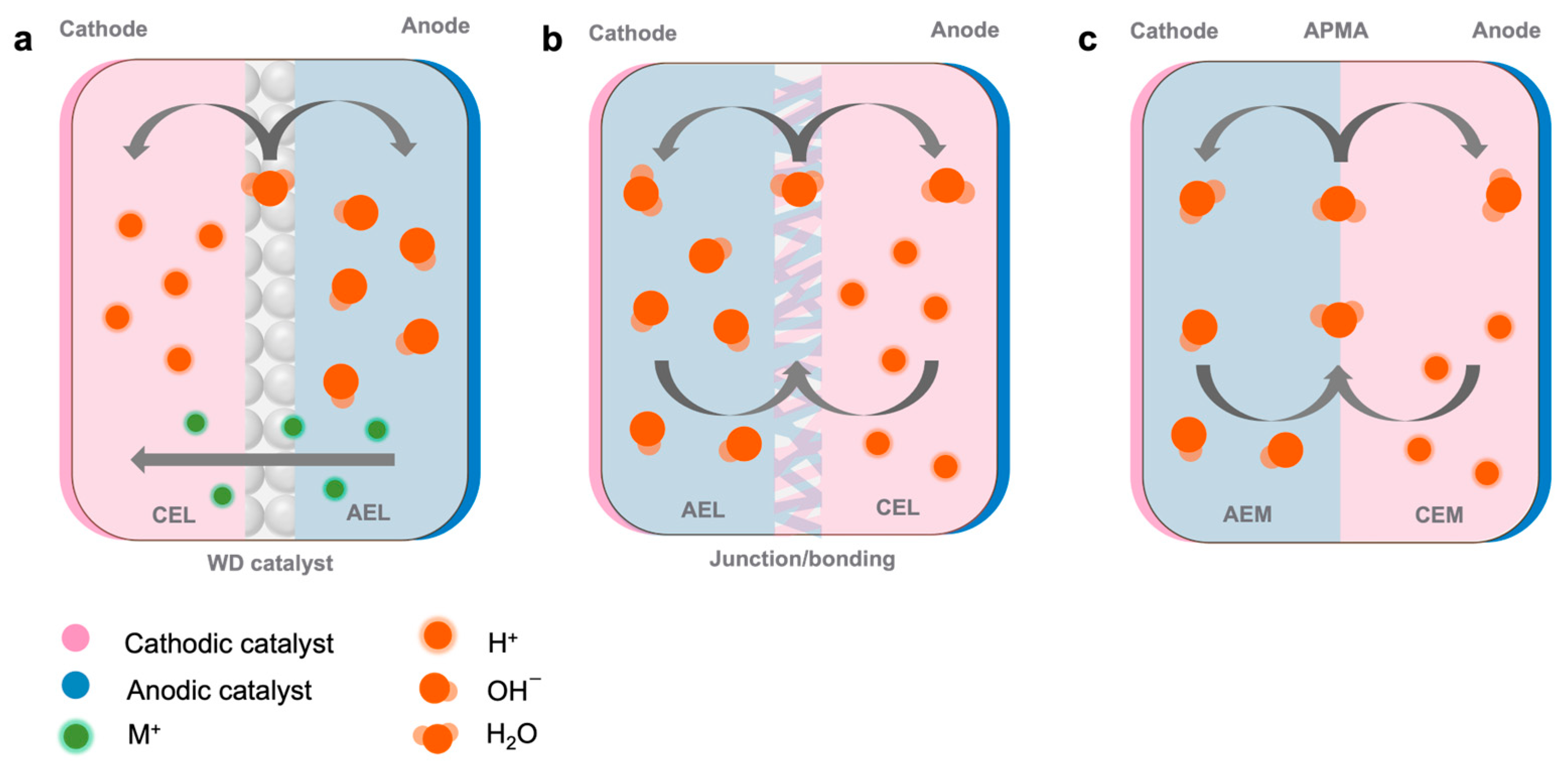

2. CO2 Electrolyzers

3. Membranes for CO2 Electrolyzers

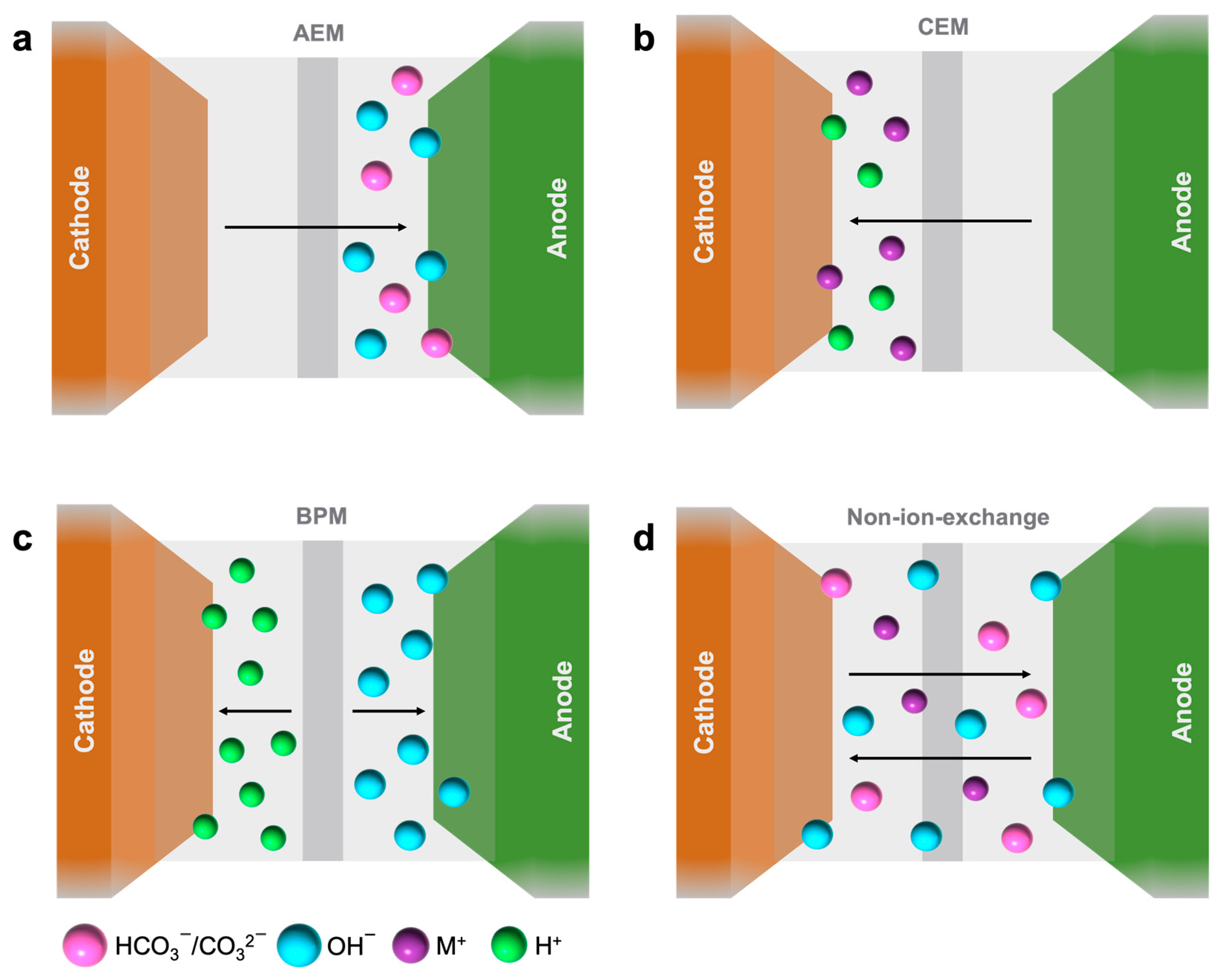

3.1. Anion Exchange Membranes (AEMs)

- Cathode:

- Anode:

3.2. Cation Exchange Membranes (CEMs)

- Cathode:

- Anode:

3.3. Bipolar Membranes (BPMs) or CEM/AEM Hybrid

- BPM interface:

- Anode:

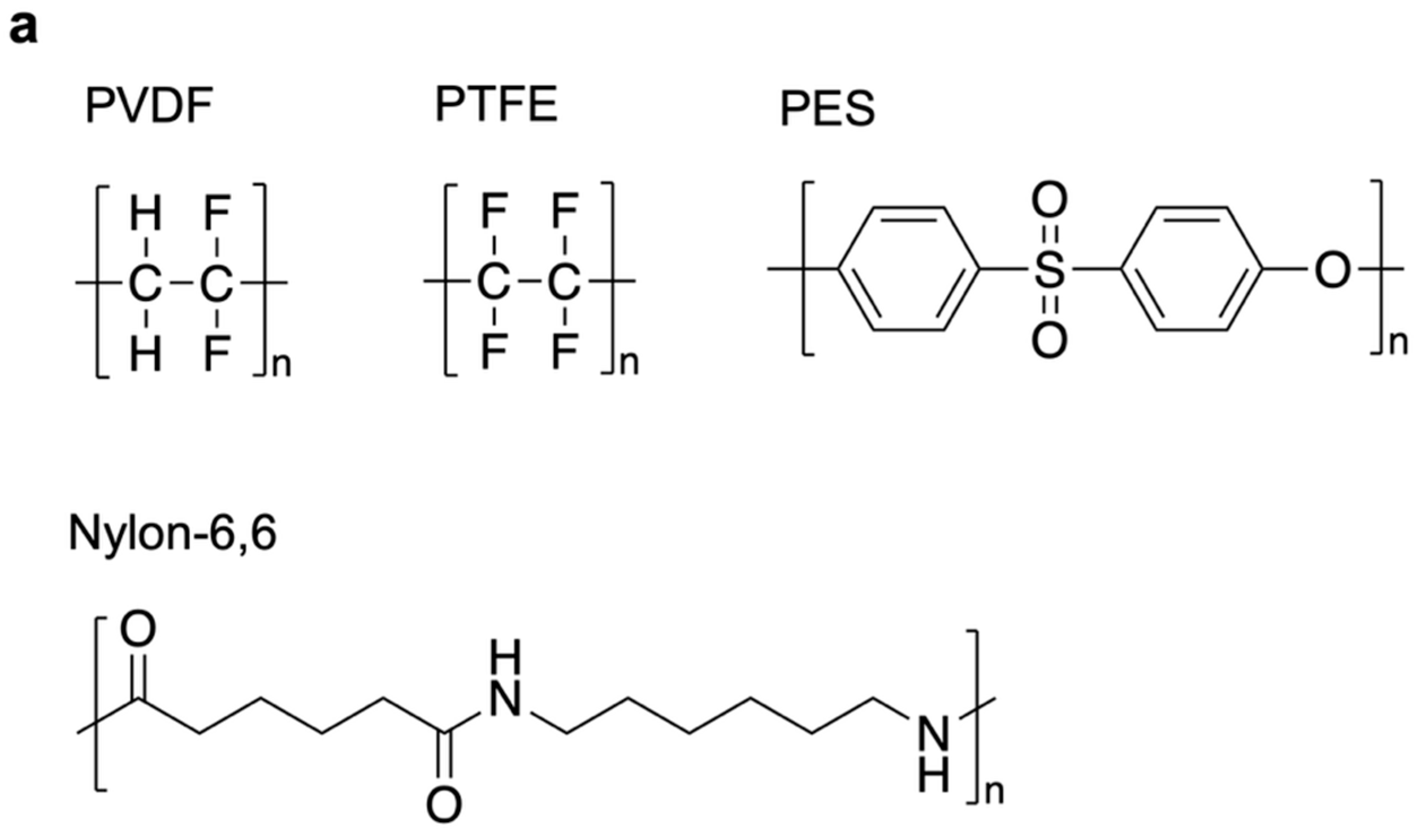

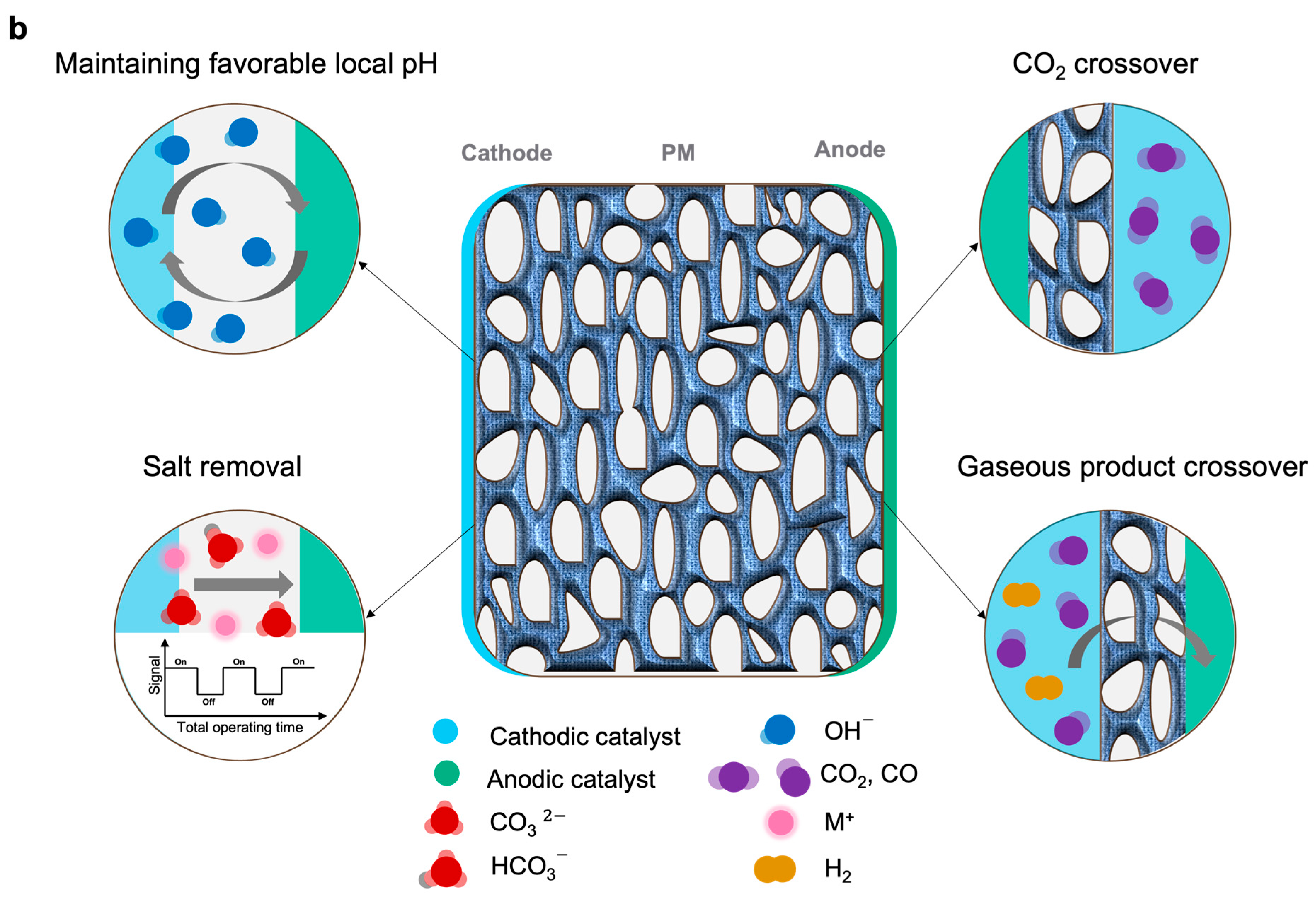

3.4. Non-Ion-Exchange Membranes

4. Conclusions and Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Woodruff, T.J. Health Effects of Fossil Fuel–Derived Endocrine Disruptors. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 390, 922–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.; Murad, S.M.W.; Mohsin, A.K.M.; Wang, X. Does Renewable Energy Proactively Contribute to Mitigating Carbon Emissions in Major Fossil Fuels Consuming Countries? J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 452, 142113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coskuner, C.; Paskeh, M.K.; Olasehinde-Williams, G.; Akadiri, S.S. Economic and Social Determinants of Carbon Emissions: Evidence from Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries. J. Public Aff. 2020, 20, e2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasileff, A.; Zheng, Y.; Qiao, S.Z. Carbon Solving Carbon’s Problems: Recent Progress of Nanostructured Carbon-Based Catalysts for the Electrochemical Reduction of CO2. Adv. Energy Mater. 2017, 7, 1700759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Guo, S.-X.; Gandionco, K.A.; Bond, A.M.; Zhang, J. Electrocatalytic Carbon Dioxide Reduction: From Fundamental Principles to Catalyst Design. Mater. Today Adv. 2020, 7, 100074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alli, Y.A.; Ejeromedoghene, O.; Dembaremba, T.O.; Adawi, A.; Alimi, O.A.; Njei, T.; Bamisaye, A.; Kofi, A.; Anene, U.Q.; Adewale, A.M.; et al. Perspectives on the Status and Future of Sustainable CO2 Conversion Processes and Their Implementation. Carbon Capture Sci. Technol. 2025, 16, 100496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, S.; Chandra Sahoo, P.; Martha, S.; Parida, K. A Review of Harvesting Clean Fuels from Enzymatic CO2 Reduction. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 44170–44194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibria, M.G.; Edwards, J.P.; Gabardo, C.M.; Dinh, C.; Seifitokaldani, A.; Sinton, D.; Sargent, E.H. Electrochemical CO2 Reduction into Chemical Feedstocks: From Mechanistic Electrocatalysis Models to System Design. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1807166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habisreutinger, S.N.; Schmidt-Mende, L.; Stolarczyk, J.K. Photocatalytic Reduction of CO2 on TiO2 and Other Semiconductors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 7372–7408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grodkowski, J.; Neta, P. Copper-Catalyzed Radiolytic Reduction of CO2 to CO in Aqueous Solutions. J. Phys. Chem. B 2001, 105, 4967–4972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, S.; Ma, X.; Gong, J. Recent Advances in Catalytic Hydrogenation of Carbon Dioxide. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 3703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Deng, K.; Du, M.; Wang, W.; Liu, F.; Liang, D. Electrochemical CO2 Reduction: From Catalysts to Reactive Thermodynamics and Kinetics. Carbon Capture Sci. Technol. 2023, 6, 100081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, W.; Wen, C.F.; Fu, H.Q.; Yuan, H.Y.; Liu, P.F.; Yang, H.G. A Focus on the Electrolyte: Realizing CO2 Electroreduction from Aqueous Solution to Pure Water. Chem. Catal. 2023, 3, 100471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesbitt, N.T.; Burdyny, T.; Simonson, H.; Salvatore, D.; Bohra, D.; Kas, R.; Smith, W.A. Liquid–Solid Boundaries Dominate Activity of CO2 Reduction on Gas-Diffusion Electrodes. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 14093–14106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weekes, D.M.; Salvatore, D.A.; Reyes, A.; Huang, A.; Berlinguette, C.P. Electrolytic CO2 Reduction in a Flow Cell. Acc. Chem. Res. 2018, 51, 910–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.N.; Dinh, C.-T. Gas Diffusion Electrode Design for Electrochemical Carbon Dioxide Reduction. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 7488–7504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Shi, K.; Dong, H.; Yang, Y.; Yin, P.; Shen, B.; Wang, J. Electrochemical Reduction of CO2 to Multicarbon Products: A Review on Catalysts and System Optimization toward Industrialization. Energy Fuels 2025, 39, 9316–9344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Xiang, X.; Zhou, L.; Fan, J.; Chen, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, C.; Fan, W.; Han, M.; Pu, Z.; et al. Catalyst Design Strategies for Highly Efficient CO2 Electroreduction. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2025, 536, 216650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Zhu, H.; He, C.; Zhuang, Z.; Sun, K.; Zhang, C.; Chen, C. Customizing Catalyst Surface/Interface Structures for Electrochemical CO2 Reduction. Chem. Sci. 2024, 15, 4292–4312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Liu, C.; Bai, M.; Fu, Z.; Zhao, P.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, M.; He, Y.; Xiao, H.; Jia, J. Recent Advances in Application of Tandem Catalyst for Electrocatalytic CO2 Reduction. Mol. Catal. 2023, 551, 113632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, R.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z. Advances in the Understanding of Selective CO2 Reduction Catalysis. EcoEnergy 2024, 2, 695–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woldu, A.R.; Yohannes, A.G.; Huang, Z.; Kennepohl, P.; Astruc, D.; Hu, L.; Huang, X. Experimental and Theoretical Insights into Single Atoms, Dual Atoms, and Sub-Nanocluster Catalysts for Electrochemical CO2 Reduction (CO2 RR) to High-Value Products. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2414169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, T.-N.; Pham, T.H.; Li, Y.; Esmaeili, H.; Dinh, C.-T. From Lab to Industry: Challenges in Scaling Cu-Based Electrodes for CO2 Electroreduction to Multi-Carbon Products. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 2025, 54, 101769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, W.; Qiao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Huang, H. Stability Issues in Electrochemical CO2 Reduction: Recent Advances in Fundamental Understanding and Design Strategies. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2306288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overa, S.; Ko, B.H.; Zhao, Y.; Jiao, F. Electrochemical Approaches for CO2 Conversion to Chemicals: A Journey toward Practical Applications. Acc. Chem. Res. 2022, 55, 638–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, P.; Chen, L. CO2 Electrolysis: Advances and Challenges in Electrocatalyst Engineering and Reactor Design. Mater. Rep. Energy 2023, 3, 100194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Hu, Q.; Guo, W.; Cao, X.; Dou, Y.; Cheng, L.; Song, Y.; Su, J.; et al. Development of Catalysts and Electrolyzers toward Industrial-Scale CO2 Electroreduction. J. Mater. Chem. A Mater. 2022, 10, 19254–19277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.; Wang, M.; Cai, L.; Xia, B.Y. Fundamental Insights for Practical Electrocatalytic CO2 Reduction. Acc. Chem. Res. 2025, 58, 2365–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Li, K.; Jia, B.; Sun, W.; Zhang, W.; Liu, X.; Ma, T. Electrocatalytic CO2 Reduction towards Industrial Applications. Carbon Energy 2023, 5, e230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabiee, H.; Li, M.; Yan, P.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Dorosti, F.; Zhang, X.; Ma, B.; Hu, S.; Wang, H.; et al. Rational Designing Microenvironment of Gas-Diffusion Electrodes via Microgel-Augmented CO2 Availability for High-Rate and Selective CO2 Electroreduction to Ethylene. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2402964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García de Arquer, F.P.; Dinh, C.-T.; Ozden, A.; Wicks, J.; McCallum, C.; Kirmani, A.R.; Nam, D.-H.; Gabardo, C.; Seifitokaldani, A.; Wang, X.; et al. CO2 Electrolysis to Multicarbon Products at Activities Greater than 1 A cm−2. Science 2020, 367, 661–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Yang, Z.; Lai, W.; Wang, Q.; Qiao, Y.; Tao, H.; Lian, C.; Liu, M.; Ma, C.; Pan, A.; et al. CO2 Electroreduction to Multicarbon Products in Strongly Acidic Electrolyte via Synergistically Modulating the Local Microenvironment. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 7596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.; Kim, Y.E.; Youn, M.H.; Jeong, S.K.; Park, K.T. Catholyte-Free Electrocatalytic CO2 Reduction to Formate. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 6883–6887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, H.; Kaur, G.; Kulkarni, A.P.; Giddey, S. Challenges and Trends in Developing Technology for Electrochemically Reducing CO2 in Solid Polymer Electrolyte Membrane Reactors. J. CO2 Util. 2019, 32, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Peng, H.; Wei, X.; Zhou, H.; Gong, J.; Huai, M.; Xiao, L.; Wang, G.; Lu, J.; Zhuang, L. An Alkaline Polymer Electrolyte CO2 Electrolyzer Operated with Pure Water. Energy Environ. Sci. 2019, 12, 2455–2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Li, F. Reactor Design for Electrochemical CO2 Conversion toward Large-Scale Applications. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2021, 27, 100419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, D.G.; Mowbray, B.A.W.; Reyes, A.; Habibzadeh, F.; He, J.; Berlinguette, C.P. Quantification of Water Transport in a CO2 Electrolyzer. Energy Environ. Sci. 2020, 13, 5126–5134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Bui, J.C.; Li, Z.; Bell, A.T.; Weber, A.Z.; Wu, J. Highly Selective and Productive Reduction of Carbon Dioxide to Multicarbon Products via in Situ CO Management Using Segmented Tandem Electrodes. Nat. Catal. 2022, 5, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Thevenon, A.; Rosas-Hernández, A.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Gabardo, C.M.; Ozden, A.; Dinh, C.T.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; et al. Molecular Tuning of CO2-to-Ethylene Conversion. Nature 2020, 577, 509–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Edwards, J.P.; Liu, S.; Miao, R.K.; Huang, J.E.; Gabardo, C.M.; O’Brien, C.P.; Li, J.; Sargent, E.H.; Sinton, D. Self-Cleaning CO2 Reduction Systems: Unsteady Electrochemical Forcing Enables Stability. ACS Energy Lett. 2021, 6, 809–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, S.; Elgazzar, A.; Zhang, S.-K.; Wi, T.-U.; Chen, F.-Y.; Feng, Y.; Zhu, P.; Wang, H. Acid-Humidified CO2 Gas Input for Stable Electrochemical CO2 Reduction Reaction. Science 2025, 388, eadr3834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, C.P.; Miao, R.K.; Shayesteh Zeraati, A.; Lee, G.; Sargent, E.H.; Sinton, D. CO2 Electrolyzers. Chem. Rev. 2024, 124, 3648–3693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvatore, D.A.; Gabardo, C.M.; Reyes, A.; O’Brien, C.P.; Holdcroft, S.; Pintauro, P.; Bahar, B.; Hickner, M.; Bae, C.; Sinton, D.; et al. Designing Anion Exchange Membranes for CO2 Electrolysers. Nat. Energy 2021, 6, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustain, W.E.; Kohl, P.A. Improving Alkaline Ionomers. Nat. Energy 2020, 5, 359–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauritz, K.A.; Moore, R.B. State of Understanding of Nafion. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 4535–4586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, G.; Fei, L.; Zhou, W.; Shao, Z. Designing Better Electrocatalysts via Ion Exchange for Water Splitting. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2417880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, N.; Roy, C.; Peach, R.; Turnbull, M.; Thiele, S.; Bock, C. Anion-Exchange Membrane Water Electrolyzers. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 11830–11895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adisasmito, S.; Khoiruddin, K.; Sutrisna, P.D.; Wenten, I.G.; Siagian, U.W.R. Bipolar Membrane Seawater Splitting for Hydrogen Production: A Review. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 14704–14727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W.; Kim, B.; Seo, J.Y.; Kim, Y.S.; Yoo, P.J.; Chung, C.-H. Water Electrolysis and Desalination Using an AEM/CEM Hybrid Electrochemical System. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 610, 155524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, M.G.; Lim, C.; Oh, C.; Kim, H.; Choi, J.-Y.; Lee, W.H.; Oh, H.-S. Efficient and Durable Porous Membrane-Based CO2 Electrolysis for Commercial Zero-Gap Electrolyzer Stack Systems. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 496, 154060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibzadeh, F.; Mardle, P.; Zhao, N.; Riley, H.D.; Salvatore, D.A.; Berlinguette, C.P.; Holdcroft, S.; Shi, Z. Ion Exchange Membranes in Electrochemical CO2 Reduction Processes. Electrochem. Energy Rev. 2023, 6, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrazábal, G.O.; Strøm-Hansen, P.; Heli, J.P.; Zeiter, K.; Therkildsen, K.T.; Chorkendorff, I.; Seger, B. Analysis of Mass Flows and Membrane Cross-over in CO2 Reduction at High Current Densities in an MEA-Type Electrolyzer. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 41281–41288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Yu, W.; Wang, Z.; Wu, L.; Wang, Y.; Xu, T. Review on High-performance Polymeric Bipolar Membrane Design and Novel Electrochemical Applications. Aggregate 2024, 5, e527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varcoe, J.R.; Atanassov, P.; Dekel, D.R.; Herring, A.M.; Hickner, M.A.; Kohl, P.A.; Kucernak, A.R.; Mustain, W.E.; Nijmeijer, K.; Scott, K.; et al. Anion-Exchange Membranes in Electrochemical Energy Systems. Energy Environ. Sci. 2014, 7, 3135–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, A.M.; Liu, B.; Buratto, S.K. Humidity-Dependent Surface Structure and Hydroxide Conductance of a Model Quaternary Ammonium Anion Exchange Membrane. Langmuir 2019, 35, 14188–14193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavel, C.C.; Cecconi, F.; Emiliani, C.; Santiccioli, S.; Scaffidi, A.; Catanorchi, S.; Comotti, M. Highly Efficient Platinum Group Metal Free Based Membrane-Electrode Assembly for Anion Exchange Membrane Water Electrolysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 1378–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henkensmeier, D.; Najibah, M.; Harms, C.; Žitka, J.; Hnát, J.; Bouzek, K. Overview: State-of-the Art Commercial Membranes for Anion Exchange Membrane Water Electrolysis. J. Electrochem. Energy Convers. Storage 2021, 18, 024001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutz, R.B.; Chen, Q.; Yang, H.; Sajjad, S.D.; Liu, Z.; Masel, I.R. Sustainion Imidazolium-Functionalized Polymers for Carbon Dioxide Electrolysis. Energy Technol. 2017, 5, 929–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabardo, C.M.; O’Brien, C.P.; Edwards, J.P.; McCallum, C.; Xu, Y.; Dinh, C.-T.; Li, J.; Sargent, E.H.; Sinton, D. Continuous Carbon Dioxide Electroreduction to Concentrated Multi-Carbon Products Using a Membrane Electrode Assembly. Joule 2019, 3, 2777–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh, C.-T.; Burdyny, T.; Kibria, M.G.; Seifitokaldani, A.; Gabardo, C.M.; García de Arquer, F.P.; Kiani, A.; Edwards, J.P.; De Luna, P.; Bushuyev, O.S.; et al. CO2 Electroreduction to Ethylene via Hydroxide-Mediated Copper Catalysis at an Abrupt Interface. Science 2018, 360, 783–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lim, J.; Roh, C.-W.; Whang, H.S.; Lee, H. Electrochemical CO2 Reduction Using Alkaline Membrane Electrode Assembly on Various Metal Electrodes. J. CO2 Util. 2019, 31, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardle, P.; Chen, B.; Holdcroft, S. Opportunities of Ionomer Development for Anion-Exchange Membrane Water Electrolysis. ACS Energy Lett. 2023, 8, 3330–3342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willdorf-Cohen, S.; Zhegur-Khais, A.; Ponce-González, J.; Bsoul-Haj, S.; Varcoe, J.R.; Diesendruck, C.E.; Dekel, D.R. Alkaline Stability of Anion-Exchange Membranes. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2023, 6, 1085–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagesteijn, K.F.L.; Jiang, S.; Ladewig, B.P. A Review of the Synthesis and Characterization of Anion Exchange Membranes. J. Mater. Sci. 2018, 53, 11131–11150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Huang, X.; Chen, Z.; Zhu, J.; Endrődi, B.; Janáky, C.; Deng, D. Membrane Electrode Assembly for Electrocatalytic CO2 Reduction: Principle and Application. Angew. Chem. 2023, 135, e202302789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Hua, H.; Wei, S.; Luo, J. Screening Anion Exchange Membranes for CO2 Electrolysis. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 56164–56174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, L.-C.; Bell, A.T.; Weber, A.Z. Towards Membrane-Electrode Assembly Systems for CO2 Reduction: A Modeling Study. Energy Environ. Sci. 2019, 12, 1950–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Sun, G.; Lewis, N.H.C.; Mandal, M.; Sharma, A.; Kim, M.; Montes de Oca, J.M.; Wang, K.; Taggart, A.; Martinson, A.B.; et al. Water-Mediated Ion Transport in an Anion Exchange Membrane. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krödel, M.; Carter, B.M.; Rall, D.; Lohaus, J.; Wessling, M.; Miller, D.J. Rational Design of Ion Exchange Membrane Material Properties Limits the Crossover of CO2 Reduction Products in Artificial Photosynthesis Devices. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 12030–12042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrov, K.V.; Bui, J.C.; Baumgartner, L.; Weng, L.-C.; Dischinger, S.M.; Larson, D.M.; Miller, D.J.; Weber, A.Z.; Vermaas, D.A. Anion-Exchange Membranes with Internal Microchannels for Water Control in CO2 Electrolysis. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2022, 6, 5077–5088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.E.; Kim, J.H.; Kwon, H.; Lee, H.; Min, H.J.; Bae, B.; Ko, Y.N.; Chun, D.H.; Youn, M.H.; Rhim, G.B.; et al. Efficient and Stable CO2 Reduction Using Quaternary Ammonium-Based High-Durability Polymer Membrane and Ionomer in Zero-Gap Electrolyzers. J. Membr. Sci. 2026, 738, 124724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Qiu, Z.; Yun, Y.; He, M.; Wang, L. Highly Performance Polybenzimidazole/Zirconia Composite Membrane with Loosened Chain Packing for Anion Exchange Membrane Water Electrolysis and Electrochemical CO2 Reduction. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 362, 131675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, J.; Cao, Z.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X.; Liu, T.; Zhang, Y. Enhanced OH− Conductivity and Stability of Polybenzimidazole Membranes for Electrocatalytic CO2 Reduction via Grafting and Crosslinking Strategies. J. Membr. Sci. 2023, 685, 121985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.; Fan, J.; Zhang, J.; Luo, Y.; Shen, C.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y. Close to 90% Single-Pass Conversion Efficiency for CO2 Electroreduction in an Acid-Fed Membrane Electrode Assembly. ACS Energy Lett. 2022, 7, 4224–4231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Li, Y.-Y.; Jung, Y.; Kuang, Y.; Zhu, G.; Liang, Y.; Dai, H. Selective and High Current CO2 Electro-Reduction to Multicarbon Products in Near-Neutral KCl Electrolytes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 3245–3255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.E.; Li, F.; Ozden, A.; Sedighian Rasouli, A.; García de Arquer, F.P.; Liu, S.; Zhang, S.; Luo, M.; Wang, X.; Lum, Y.; et al. CO2 Electrolysis to Multicarbon Products in Strong Acid. Science 2021, 372, 1074–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, C.P.; Miao, R.K.; Liu, S.; Xu, Y.; Lee, G.; Robb, A.; Huang, J.E.; Xie, K.; Bertens, K.; Gabardo, C.M.; et al. Single Pass CO2 Conversion Exceeding 85% in the Electrosynthesis of Multicarbon Products via Local CO2 Regeneration. ACS Energy Lett. 2021, 6, 2952–2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Disch, J.; Bohn, L.; Metzler, L.; Vierrath, S. Strategies for the Mitigation of Salt Precipitation in Zero-Gap CO2 Electrolyzers Producing CO. J. Mater. Chem. A Mater. 2023, 11, 7344–7357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lees, E.W.; Mowbray, B.A.W.; Parlane, F.G.L.; Berlinguette, C.P. Gas Diffusion Electrodes and Membranes for CO2 Reduction Electrolysers. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2021, 7, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nara, M.; Fujii, K.; Matsui, D.; Ogura, A.; Murakami, T.; Ogawa, T.; Ito, S.; Cheng, C.D.; Scholes, C.A.; Wada, S. Evaluating Cation-Exchange Membrane Properties Affecting Polymer Electrolyte Membrane Water Electrolysis. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 10425–10431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-S.; Park, D.-H.; Park, S.-H.; Gu, Y.-H.; Lim, D.-M.; Han, S.-B.; Park, K.-W. Lithium-Ion Exchange Membrane Water Electrolysis Using a Cationic Polymer-Modified Polyethersulfone Membrane. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 10183–10190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, A.; Karnes, J.J.; Clemens, A.L.; Oakdale, J.S.; Molinero, V. Post-Hydration Crosslinking of Ion Exchange Membranes to Control Water Content. J. Phys. Chem. C 2023, 127, 5613–5621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Ko, Y.; Lim, C.; Kim, H.; Min, B.K.; Lee, K.-Y.; Koh, J.H.; Oh, H.-S.; Lee, W.H. Strategies for CO2 Electroreduction in Cation Exchange Membrane Electrode Assembly. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 453, 139826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pärnamäe, R.; Mareev, S.; Nikonenko, V.; Melnikov, S.; Sheldeshov, N.; Zabolotskii, V.; Hamelers, H.V.M.; Tedesco, M. Bipolar Membranes: A Review on Principles, Latest Developments, and Applications. J. Membr. Sci. 2021, 617, 118538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinowitz, J.A.; Kanan, M.W. The Future of Low-Temperature Carbon Dioxide Electrolysis Depends on Solving One Basic Problem. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.C.; Zhou, D.; Yan, Z.; Gonçalves, R.H.; Salvatore, D.A.; Berlinguette, C.P.; Mallouk, T.E. Electrolysis of CO2 to Syngas in Bipolar Membrane-Based Electrochemical Cells. ACS Energy Lett. 2016, 1, 1149–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Hitt, J.L.; Zeng, Z.; Hickner, M.A.; Mallouk, T.E. Improving the Efficiency of CO2 Electrolysis by Using a Bipolar Membrane with a Weak-Acid Cation Exchange Layer. Nat. Chem. 2021, 13, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Sun, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yue, L.; Han, L.; Zhao, L.; Zhu, X.; Zhan, D. In Situ Electropolymerizing Toward EP-CoP/Cu Tandem Catalyst for Enhanced Electrochemical CO2-to-Ethylene Conversion. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2404053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Nabil, S.K.; Al-Attas, T.; Yasri, N.G.; Roy, S.; Rahman, M.M.; Larter, S.; Ajayan, P.M.; Hu, J.; Kibria, M.G. Zero-Crossover Electrochemical CO2 Reduction to Ethylene with Co-Production of Valuable Chemicals. Chem. Catal. 2022, 2, 2077–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blommaert, M.A.; Sharifian, R.; Shah, N.U.; Nesbitt, N.T.; Smith, W.A.; Vermaas, D.A. Orientation of a Bipolar Membrane Determines the Dominant Ion and Carbonic Species Transport in Membrane Electrode Assemblies for CO2 Reduction. J. Mater. Chem. A Mater. 2021, 9, 11179–11186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafaque, H.W.; Lee, C.; Fahy, K.F.; Lee, J.K.; LaManna, J.M.; Baltic, E.; Hussey, D.S.; Jacobson, D.L.; Bazylak, A. Boosting Membrane Hydration for High Current Densities in Membrane Electrode Assembly CO2 Electrolysis. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 54585–54595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, R.; Dessiex, M.A.; Marone, F.; Büchi, F.N. Gas-Induced Structural Damages in Forward-Bias Bipolar Membrane CO2 Electrolysis Studied by Fast X-Ray Tomography. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2024, 7, 3590–3601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Zhang, Z.; Luo, F.; Li, X.; Duan, F.; Xu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Liang, X.; Wang, Y.; Wu, L.; et al. Tailoring High-Performance Bipolar Membrane for Durable Pure Water Electrolysis. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 10220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, C.; Wycisk, R.; Pintauro, P.N. High Performance Electrospun Bipolar Membrane with a 3D Junction. Energy Environ. Sci. 2017, 10, 1435–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Clark, E.L.; Therkildsen, K.T.; Dalsgaard, S.; Chorkendorff, I.; Seger, B. Insights into the Carbon Balance for CO2 Electroreduction on Cu Using Gas Diffusion Electrode Reactor Designs. Energy Environ. Sci. 2020, 13, 977–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvatore, D.A.; Weekes, D.M.; He, J.; Dettelbach, K.E.; Li, Y.C.; Mallouk, T.E.; Berlinguette, C.P. Electrolysis of Gaseous CO2 to CO in a Flow Cell with a Bipolar Membrane. ACS Energy Lett. 2018, 3, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Xu, Q.; Oener, S.Z.; Fabrizio, K.; Boettcher, S.W. Design Principles for Water Dissociation Catalysts in High-Performance Bipolar Membranes. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, K.; Miao, R.K.; Ozden, A.; Liu, S.; Chen, Z.; Dinh, C.-T.; Huang, J.E.; Xu, Q.; Gabardo, C.M.; Lee, G.; et al. Bipolar Membrane Electrolyzers Enable High Single-Pass CO2 Electroreduction to Multicarbon Products. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkayyali, T.; Zeraati, A.S.; Mar, H.; Arabyarmohammadi, F.; Saber, S.; Miao, R.K.; O’Brien, C.P.; Liu, H.; Xie, Z.; Wang, G.; et al. Direct Membrane Deposition for CO2 Electrolysis. ACS Energy Lett. 2023, 8, 4674–4683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, X.; Zhai, L.; Wang, Y.; Xiong, P.; Li, M.M.-J.; Wu, T.-S.; Wong, M.C.; Guo, X.; Xu, Z.; Li, H.; et al. Pure-Water-Fed, Electrocatalytic CO2 Reduction to Ethylene beyond 1000 h Stability at 10 A. Nat. Energy 2024, 9, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Karamoko, B.A.; Wang, W.; Liu, J.; Petit, E.; Li, S.; Salameh, C.; Voiry, D. Engineering the Catalyst Interface Enables High Carbon Efficiency in Both Cation-Exchange and Bipolar Membrane Electrolyzers. Appl. Catal. B Environ. Energy 2025, 361, 124691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henkensmeier, D.; Cho, W.-C.; Jannasch, P.; Stojadinovic, J.; Li, Q.; Aili, D.; Jensen, J.O. Separators and Membranes for Advanced Alkaline Water Electrolysis. Chem. Rev. 2024, 124, 6393–6443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, X.; Shang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, W.; He, G. A Catalyst-Coated Diaphragm Assembly to Improve the Performance and Energy Efficiency of Alkaline Water Electrolysers. Commun. Eng. 2025, 4, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lira Garcia Barros, R.; Kraakman, J.T.; Sebregts, C.; van der Schaaf, J.; de Groot, M.T. Impact of an Electrode-Diaphragm Gap on Diffusive Hydrogen Crossover in Alkaline Water Electrolysis. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 49, 886–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.H.; Kim, K.; Lim, C.; Ko, Y.-J.; Hwang, Y.J.; Min, B.K.; Lee, U.; Oh, H.-S. New Strategies for Economically Feasible CO2 Electroreduction Using a Porous Membrane in Zero-Gap Configuration. J. Mater. Chem. A Mater. 2021, 9, 16169–16177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Xing, S.; Maia, G.W.P.; Wang, Z.; Crandall, B.S.; Jiao, F. Diaphragm-Based Carbon Monoxide Electrolyzers for Multicarbon Production under Alkaline Conditions. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 8444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.H.; Lai, H.D.T.; Dang, N.K.; Nguyen, T.N.; Golovanova, V.; Dias, E.H.; Ho, A.; Xia, L.; Crane, J.; de Arquer, F.P.G.; et al. Ambipolar Ion Transport Membranes Enable Stable Noble-Metal-Free CO2 Electrolysis in Neutral Media. Adv. Energy Mater. 2025, 15, e04286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, R.K.; Fan, M.; Wang, N.; Zhao, Y.; Li, F.; Liu, M.; Arabyarmohammadi, F.; Liang, Y.; Ni, W.; Xie, K.; et al. CO Electrolysers with 51% Energy Efficiency towards C2+ Using Porous Separators. Nat. Energy 2025, 10, 1197–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ho, T.-N.; Phan-Pham, D.-M.; Ho, A.-D.; Bui, T.A.; Gao, G.; Dinh, C.-T. Membranes for Electrochemical Carbon Dioxide Conversion to Multi-Carbon Products. Catalysts 2026, 16, 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020139

Ho T-N, Phan-Pham D-M, Ho A-D, Bui TA, Gao G, Dinh C-T. Membranes for Electrochemical Carbon Dioxide Conversion to Multi-Carbon Products. Catalysts. 2026; 16(2):139. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020139

Chicago/Turabian StyleHo, Thao-Nguyen, Duc-Minh Phan-Pham, Anh-Dao Ho, Tuan Anh Bui, Guorui Gao, and Cao-Thang Dinh. 2026. "Membranes for Electrochemical Carbon Dioxide Conversion to Multi-Carbon Products" Catalysts 16, no. 2: 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020139

APA StyleHo, T.-N., Phan-Pham, D.-M., Ho, A.-D., Bui, T. A., Gao, G., & Dinh, C.-T. (2026). Membranes for Electrochemical Carbon Dioxide Conversion to Multi-Carbon Products. Catalysts, 16(2), 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16020139