Nb-MOG as a High-Performance Photocatalyst for Cr(VI) Remediation: Optimization and Reuse Cycles

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Catalysts Characterization

2.1.1. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

2.1.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy–Energy Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy (SEM–EDS)

2.1.3. Photoacoustic Spectroscopy (PAS) and Ponto De Carga Zero (PCZ)

2.1.4. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

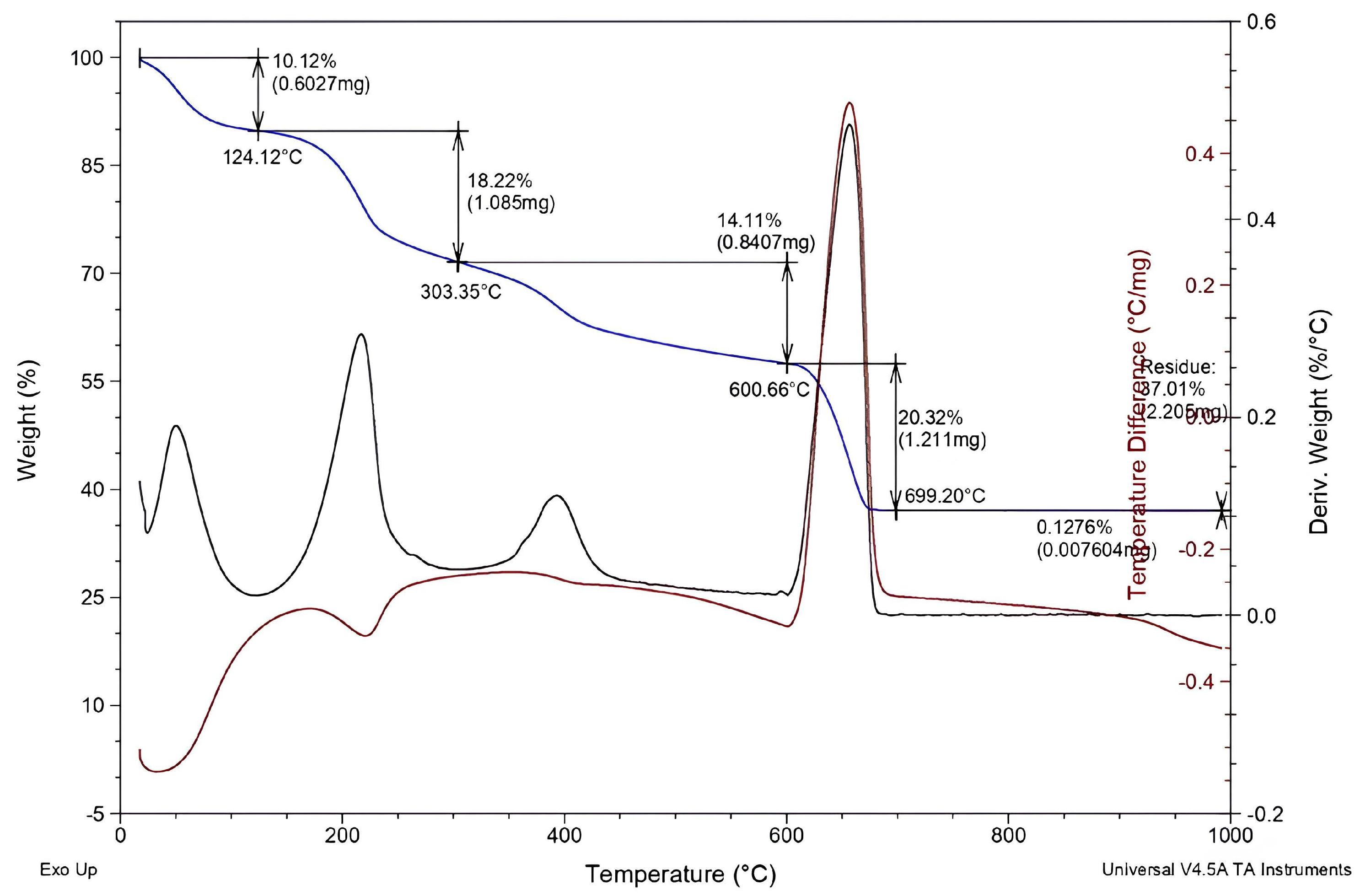

2.1.5. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TG)

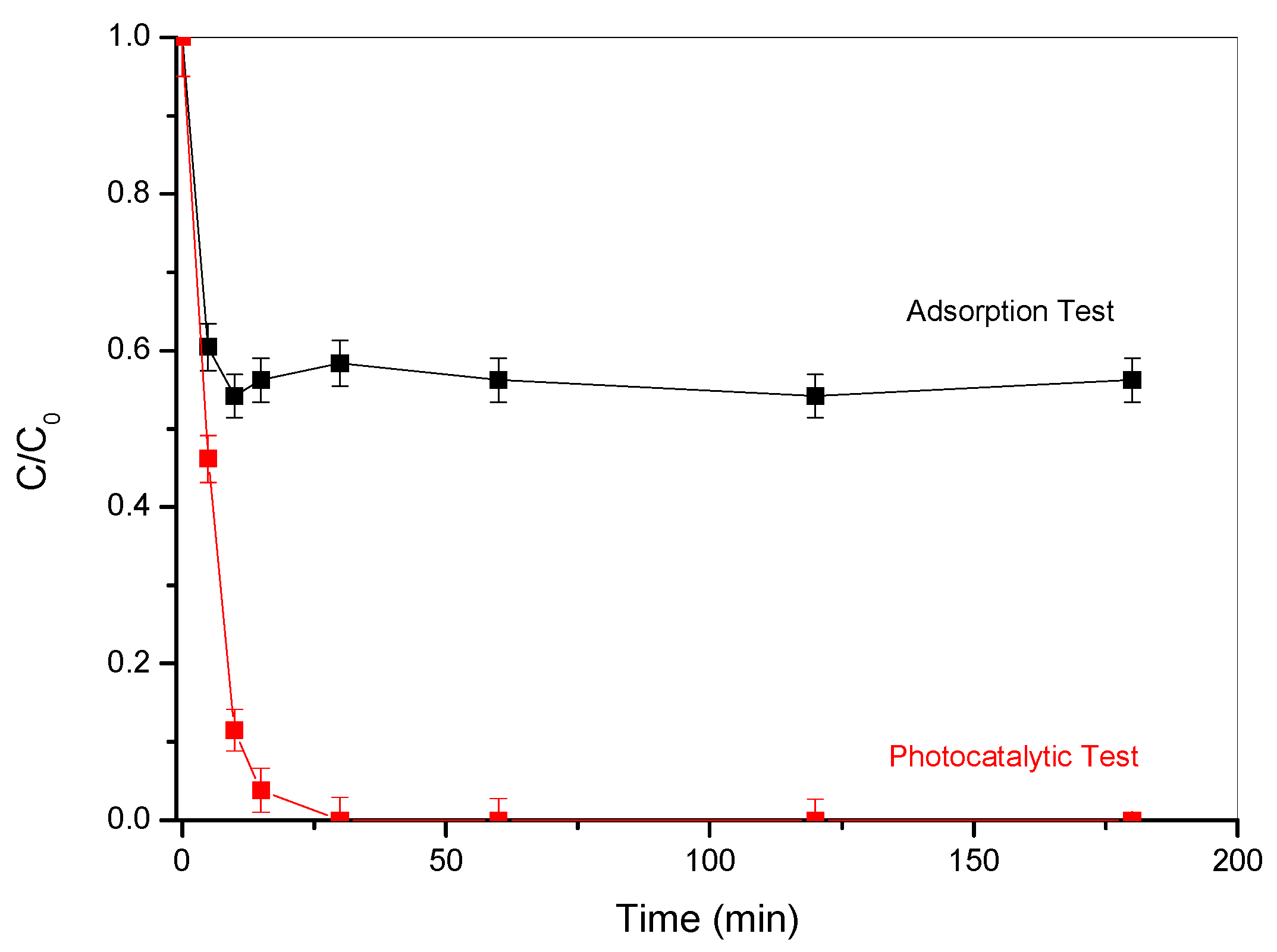

2.2. Catalytic and Adsorption Tests

2.3. Experimental Design Results

2.4. Reuse Test

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemicals

3.2. Catalyst Synthesis

3.3. Catalyst Characterization

3.4. Cr(VI) Removal Tests

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hossini, H.; Shafie, B.; Niri, A.D.; Nazari, M.; Esfahlan, A.J.; Ahmadpour, M.; Nazmara, Z.; Ahmadimanesh, M.; Makhdoumi, P.; Mirzaei, N.; et al. A comprehensive review on human health effects of chromium: Insights on induced toxicity. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 70686–70705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layek, M.; Khatun, N.; Karmakar, P.; Kundu, S.; Mitra, M.; Karmakar, K.; Mondal, S.; Bhattarai, A.; Saha, B. Toxicity of Hexavalent Chromium: Review. In Chromium in Plants and Environment; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 191–215. [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi, M.; Pathak, S.; Singh, R.; Singh, P.; Singh, P.K.; Shukla, A.K.; Maurya, S.; Kaur, S.; Thakur, B. A Comprehensive Review of Lab-Scale Studies on Removing Hexavalent Chromium from Aqueous Solutions by Using Unmodified and Modified Waste Biomass as Adsorbents. Toxics 2024, 12, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sazakli, E. Human Health Effects of Oral Exposure to Chromium: A Systematic Review of the Epidemiological Evidence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, V.; Singh, N.; Verma, M.; Kamal, R.; Tiwari, R.; Sanjay Chivate, M.; Rai, S.N.; Kumar, A.; Singh, A.; Singh, M.P.; et al. Hexavalent-Chromium-Induced Oxidative Stress and the Protective Role of Antioxidants against Cellular Toxicity. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assefa, H.; Singh, S.; Olu, F.E.; Dhanjal, D.S.; Mani, D.; Khan, N.A.; Singh, J.; Ramamurthy, P.C. Advances in adsorption technologies for hexavalent chromium removal: Mechanisms, materials, and optimization strategies. Desalination Water Treat. 2024, 319, 100576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain, A.; Ayub, S.; Khan, A.H.; Alam, S.S.; Hasan, M.A. Pilot scale recovery, and removal of chromium from tannery wastewater by chemical precipitation: Life cycle assessment and cost analysis. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 391, 126502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, J.; Yu, M.; Bi, W.; Sun, Y.; Wang, W.; Hou, Y.; Xie, S.; Li, T.; Fan, Y. Research on chromium removal mechanism by electrochemical method from wastewater. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 68, 106447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Wang, Y. A Comparative Review of Removing Chromium (VI) from Electroplating Industry Wastewater Using Electrocoagulation and Membrane Filtration. Sci. Technol. Eng. Chem. Environ. Prot. 2025, 3, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Thiripelu, P.; Manjunathan, J.; Revathi, M.; Ramasamy, P. Removal of hexavalent chromium from electroplating wastewater by ion-exchange in presence of Ni(II) and Zn(II) ions. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 58, 104815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuziki, M.E.K.; Tusset, A.M.; Ribas, L.S.; de Paula, E.T.; Brackmann, R.; Alves, O.C.; dos Santos, O.A.A.; Lenzi, G.G. CoFe2O4/TiO2-Nb2O5 magnetic catalysts synthesized by chemical and physical mixture applied in the reduction of Cr(VI). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2025, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samajdar, S.; Golda, A.S.; Lakhera, S.K.; Ghosh, S. Recent progress in chromium removal from wastewater using covalent organic frameworks—A review. Chemosphere 2024, 350, 141028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fidelis, M.Z.; Abreu, E.; Josué, T.G.; de Almeida, L.N.B.; Lenzi, G.G.; Santos, O.A.A.D. Continuous process applied to degradation of triclosan and 2.8-dichlorodibenzene-p-dioxin. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 23675–23683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, L.E.N.; Meira, A.H.; Almeida, L.N.B.; Gonçalves Lenzi, G.; Colpini, L.M.S. Experimental design and optimization of textile dye photodiscoloration using Zn/TiO2 catalysts. Desalination Water Treat. 2022, 266, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurino, V.; Minella, M.; Sordello, F.; Minero, C. A proof of the direct hole transfer in photocatalysis: The case of melamine. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2016, 521, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Gao, Q.; Al-Enizi, A.M.; Nafady, A.; Ma, S. Recent advances in MOF-based photocatalysis: Environmental remediation under visible light. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2020, 7, 300–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.L.; Feng, X.Q.; Han, R.P.; Zang, S.Q.; Yang, G. Cr(VI) removal via anion exchange on a silver-triazolate MOF. J. Hazard. Mater. 2017, 321, 622–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Shen, J.; Wu, Y.; Li, X.; Ma, Y.; Xie, Y.; Yu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J. Bi2O2CO3 co-catalyst modification BiOBr driving efficient photoreduction CO2. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2025, 725, 137731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öhrström, L. Let’s Talk about MOFs—Topology and Terminology of Metal-Organic Frameworks and Why We Need Them. Crystals 2015, 5, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xavier, J.R. Novel multifunctional epoxy based graphitic carbon nitride/silanized TiO2 nanocomposite as protective coatings for steel surface against corrosion and flame in the shipping industry. J. Cent. South. Univ. 2024, 31, 3394–3422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulaeto, S.B.; Ravi, R.P.; Udoh, I.I.; Mathew, G.M.; Rajan, T.P.D. Polymer-Based Coating for Steel Protection, Highlighting Metal–Organic Framework as Functional Actives: A Review. Corros. Mater. Degrad. 2023, 4, 284–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, V.F.; Malek, N.I.; Kailasa, S.K. Review on Metal–Organic Framework Classification, Synthetic Approaches, and Influencing Factors: Applications in Energy, Drug Delivery, and Wastewater Treatment. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 44507–44531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oroujzadeh, A.R.; Nematollahzadeh, A.; Dabaleh, A.; Seifzadeh, D.; Shojaei, A. Fabrication of metal-organic gel (MOG) nanoparticles-enhanced epoxy coating as a pH-sensitive corrosion inhibitor under diverse environmental conditions. Prog. Org. Coat. 2025, 209, 109621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Lin, Z.; Zheng, D.; Zhang, J.; Heng, W.; Wei, Y.; Gao, Y.; Qian, S. Metal–organic gels: Recent advances in their classification, characterization, and application in the pharmaceutical field. J. Mater. Chem. B 2023, 11, 10566–10594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, D.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, H.; Hao, J. Cobalt-doped iron-based metal–organic gels as efficient visible-light-driven peroxymonosulfate activators for the efficient degradation of norfloxacin with simultaneous antibacterial activity. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 486, 149892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Deng, T.; Yin, K.; Tian, J.; Chen, H.; Peng, H.; Du, J. Iron-doped titanium dioxide metal-organic gel for degradation of tetracycline hydrochloride with persulfate: Synergistic visible light photocatalysis and sulphate radical oxidation process. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1341, 142455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidelis, M.Z.; Abreu, E.; Dos Santos, O.A.A.; Chaves, E.S.; Brackmann, R.; Dias, D.T.; Lenzi, G.G. Experimental Design and Optimization of Triclosan and 2.8-Diclorodibenzeno-p-dioxina Degradation by the Fe/Nb2O5/UV System. Catalysts 2019, 9, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josué, T.G.; Almeida, L.N.B.; Lopes, M.F.; Santos, O.A.A.; Lenzi, G.G. Cr(VI) reduction by photocatalyic process: Nb2O5 an alternative catalyst. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 268, 110711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, H.; Xu, X.; Yu, X.; Yu, S.; Wang, S.; Qu, X. Bimetallic Organic Gel for Effective Methyl Orange Dye Adsorption. Gels 2024, 10, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhao, H.; Li, C.; Li, S.; Liu, K.; Wang, L. Facile coordination driven synthesis of metal-organic gels toward efficiently electrocatalytic overall water splitting. Appl. Catal. B 2021, 299, 120641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenzi, G.G.; Fávero, C.V.B.; Colpini, L.M.S.; Bernabe, H.; Baesso, M.L.; Specchia, S.; Santos, O. Photocatalytic reduction of Hg(II) on TiO2 and Ag/TiO2 prepared by the sol–gel and impregnation methods. Desalination 2011, 270, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weibin, Z.; Weidong, W.; Xueming, W.; Xinlu, C.; Dawei, Y.; Changle, S.; Liping, P.; Yuying, W.; Li, B. The investigation of NbO2 and Nb2O5 electronic structure by XPS, UPS and first principles methods. Surf. Interface Anal. 2013, 45, 1206–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, E.; Fidelis, M.Z.; Fuziki, M.E.; Malikoski, R.M.; Mastsubara, M.C.; Imada, R.E.; de Tuesta, J.L.D.; Gomes, H.T.; Anziliero, M.D.; Baldykowski, B.; et al. Degradation of emerging contaminants: Effect of thermal treatment on Nb2O5 as photocatalyst. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2021, 419, 113484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakatula, E.N.; Richard, D.; Neculita, C.M.; Zagury, G.J. Determination of point of zero charge of natural organic materials. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 7823–7833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantão, F.d.O.; Melo, W.d.C.; Oliveira, L.C.A.; Passos, A.R.; Silva, A.C.d. Utilization of Sn/Nb2O5 composite for the removal of methylene blue. Quim. Nova 2010, 33, 528–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabacak, M.; Cinar, M.; Unal, Z.; Kurt, M. FT-IR, UV spectroscopic and DFT quantum chemical study on the molecular conformation, vibrational and electronic transitions of 2-aminoterephthalic acid. J. Mol. Struct. 2010, 982, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, R.S.; Chaudhary, R.; Singh, C. Influence of pH on photocatalytic reduction, adsorption, and deposition of metal ions: Speciation modeling. Desalination Water Treat. 2015, 56, 1335–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendon, C.H.; Tiana, D.; Fontecave, M.; Sanchez, C.; D’arras, L.; Sassoye, C.; Rozes, L.; Mellot-Draznieks, C.; Walsh, A. Engineering the Optical Response of the Titanium-MIL-125 Metal–Organic Framework through Ligand Functionalization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 10942–10945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, D.C.; Cavalcante, R.P.; Jorge, J.; Martines, M.A.U.; Oliveira, L.C.S.; Casagrande, G.A.; Machulek, A., Jr. Synthesis and Characterization of Mesoporous Nb2O5 and Its Application for Photocatalytic Degradation of the Herbicide Methylviologen. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2015, 27, 303–313. [Google Scholar]

| Run | pH | Catalyst Conc. (g·L−1) | Total Chromium Removal (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2.50 | 0.250 | 53.06 |

| 2 | 2.50 | 0.750 | 74.47 |

| 3 | 7.50 | 0.250 | 18.75 |

| 4 | 7.50 | 0.750 | 97.92 |

| 5 | 1.46 | 0.500 | 48.89 |

| 6 | 8.54 | 0.500 | 47.92 |

| 7 | 5.00 | 0.146 | 61.70 |

| 8 | 5.00 | 0.854 | 100.00 |

| 9 | 5.00 | 0.500 | 91.84 |

| 10 | 5.00 | 0.500 | 95.83 |

| 11 | 5.00 | 0.500 | 93.88 |

| SS | df | MS | F | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 7304.433 | 5 | 1460.887 | 23.25416 | 0.001793 |

| (1) pH (L) | 18.702 | 1 | 18.702 | 0.29770 | 0.608779 |

| pH (Q) | 3149.685 | 1 | 3149.685 | 50.13620 | 0.000870 |

| (2) catalyst concentration (g·L−1) (L) | 2993.228 | 1 | 2993.228 | 47.64573 | 0.000978 |

| catalyst concentration (g·L−1) (Q) | 308.763 | 1 | 308.763 | 4.91484 | 0.077425 |

| 1 L by 2L | 834.054 | 1 | 834.054 | 13.27635 | 0.014846 |

| Residual | 314.113 | 5 | 62.823 | ||

| Total SS | 7311.025 | 10 |

| Effect | Std. Err. | t(5) | p | −95% Cnf. Limt | +95% Cnf. Limt | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean/Interaction | 93.8500 | 4.576119 | 20.50865 | 0.000005 | 82.0867 | 105.6133 |

| (1) pH (L) | −3.0579 | 5.604578 | −0.54562 | 0.608779 | −17.4650 | 11.3491 |

| pH (Q) | −47.2338 | 6.670782 | −7.08069 | 0.000870 | −64.3815 | −30.0860 |

| (2) Catalyst concentration (L) | 38.6861 | 5.604578 | 6.90259 | 0.000978 | 24.2791 | 53.0931 |

| Catalyst concentration (Q) | −14.7888 | 6.670782 | −2.21694 | 0.077425 | −31.9365 | 2.3590 |

| (1L) by (2L) | 28.8800 | 7.926070 | 3.64367 | 0.014846 | 8.5054 | 49.2546 |

| SS | df | MS | F | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 2420.635 | 5 | 484.1271 | 13.16064 | 0.006662 |

| (1) pH (L) | 1081.024 | 1 | 1081.024 | 29.38684 | 0.002893 |

| pH (Q) | 24.346 | 1 | 24.346 | 0.66182 | 0.452901 |

| (2) Catalyst concentration (L) | 905.133 | 1 | 905.133 | 24.60537 | 0.004247 |

| Catalyst concentration (Q) | 21.069 | 1 | 21.069 | 0.57273 | 0.483290 |

| 1L by 2L | 389.065 | 1 | 389.065 | 10.57644 | 0.022642 |

| Residuals | 183.930 | 5 | 36.786 | ||

| Total SS | 2594.282 | 10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Abreu, E.; Santos, O.A.A.d.; Fuziki, M.E.K.; Tusset, A.M.; Fidelis, M.Z.; Motheo, A.J.; Lenzi, G.G. Nb-MOG as a High-Performance Photocatalyst for Cr(VI) Remediation: Optimization and Reuse Cycles. Catalysts 2026, 16, 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010060

Abreu E, Santos OAAd, Fuziki MEK, Tusset AM, Fidelis MZ, Motheo AJ, Lenzi GG. Nb-MOG as a High-Performance Photocatalyst for Cr(VI) Remediation: Optimization and Reuse Cycles. Catalysts. 2026; 16(1):60. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010060

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbreu, Eduardo, Onelia A. A. dos Santos, Maria E. K. Fuziki, Angelo M. Tusset, Michel Z. Fidelis, Artur J. Motheo, and Giane G. Lenzi. 2026. "Nb-MOG as a High-Performance Photocatalyst for Cr(VI) Remediation: Optimization and Reuse Cycles" Catalysts 16, no. 1: 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010060

APA StyleAbreu, E., Santos, O. A. A. d., Fuziki, M. E. K., Tusset, A. M., Fidelis, M. Z., Motheo, A. J., & Lenzi, G. G. (2026). Nb-MOG as a High-Performance Photocatalyst for Cr(VI) Remediation: Optimization and Reuse Cycles. Catalysts, 16(1), 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010060