Morphology Dependence of Catalytic Properties of CeO2 Nanocatalysts for One-Step CO2 Conversion to Diethyl Carbonate

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Catalysts Characterization

2.2. Catalytic Performance

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Preparation of CeO2 Catalysts

3.3. Characterization

3.4. Catalytic Performance Test

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vega, L.F.; Bahamon, D.; Alkhatib, I.I. Perspectives on advancing sustainable CO2 conversion processes: Trinomial technology, environment, and economy. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 5357–5382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwabueze, Q.A.; Leggett, S. Advancements in the application of CO2 capture and utilization technologies—A comprehensive review. Fuels 2024, 5, 508–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Su, W.; Xing, Y.; Cui, Y.; Liu, X.; Guo, W.; Che, Z. Research progress and future prospects of chemical utilization of CO2. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 510, 161579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wu, M.; Xu, Y.; Ma, C.; Song, M.; Jiang, G. Efficient photoreduction of CO2 to CO with 100% selectivity by slowing down electron transport. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 9163–9171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onishi, N.; Himeda, Y. Toward methanol production by CO2 hydrogenation beyond formic acid formation. Acc. Chem. Res. 2024, 57, 2816–2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salami, R.; Zeng, Y.; Han, X.; Rohani, S.; Zheng, Y. Exploring catalyst developments in heterogeneous CO2 hydrogenation to methanol and ethanol: A journey through reaction pathways. J. Energy Chem. 2025, 101, 345–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, Y.; Liu, L.; Seemakurthi, R.R.; You, F.; Ma, H.; Pérez-Ramírez, J.; López, N.; Yeo, B.S. Controlling hydrocarbon chain growth and degree of branching in CO2 electroreduction on fluorine-doped nickel catalysts. Nat. Catal. 2025, 8, 714–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Chang, X.L.; Yan, T.; Pan, W.G. Research progress in catalytic conversion of CO2 and epoxides based on ionic liquids to cyclic carbonates. Nano Energy 2025, 135, 110596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, A.; Verma, M.; Thakur, A.; Bharti, R.; Sharma, R. Visible Light Mediated CO2 Fixation Reactions to Produce Carbamates and Carbonates: A Comprehensive Review. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2024, 61, 2050–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yabushita, M.; Fujii, R.; Nakagawa, Y.; Tomishige, K. Thermodynamic and Catalytic Insights into Non-Reductive Transformation of CO2 with Amines into Organic Urea Derivatives. ChemCatChem 2024, 16, e202301342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koizumi, H.; Nagae, H.; Takeuchi, K.; Matsumoto, K.; Fukaya, N.; Inoue, Y.; Hamura, S.; Masuda, T.; Choi, J.C. Dialkyl Carbonate Synthesis Using Atmospheric Pressure of CO2. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 25879–25886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeuchi, K.; Koizumi, H.; Nagae, H.; Matsumoto, K.; Fukaya, N.; Sato, K.; Choi, J.C. Direct use of low-concentration CO2 in the synthesis of dialkyl carbonates, carbamate acid esters, and urea derivatives. J. CO2 Util. 2024, 83, 102814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Wang, Q.; Li, L.; Lyu, D.; Lin, H.; Han, D. Exploring dialkyl carbonate as a low-carbon fuel for combustion engines: An overview. Fuel 2025, 386, 134221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Ruan, J.; Chen, L.; Qi, Z. Structure effects of imidazolium ionic liquids on integrated CO2 absorption and transformation to dimethyl carbonate. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 112790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akune, T.; Morita, Y.; Shirakawa, S.; Katagiri, K.; Inumaru, K. ZrO2 nanocrystals as catalyst for synthesis of dimethylcarbonate from methanol and carbon dioxide: Catalytic activity and elucidation of active sites. Langmuir 2018, 34, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomishige, K.; Gu, Y.; Nakagawa, Y.; Tamura, M. Reaction of CO2 with alcohols to linear-, cyclic-, and poly-carbonates using CeO2-based catalysts. Front. Energy Res. 2020, 8, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Jia, D.; Zhang, J.; Sun, Y. Direct synthesis of diethyl carbonate from CO2 and ethanol catalyzed by ZrO2/molecular sieve. Catal. Lett. 2014, 144, 2144–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norouzi, F.; Abdolmaleki, A. CO2 conversion into carbonate using pyridinium-based ionic liquids under mild conditions. Fuel 2023, 334, 126641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Liang, L.; Zhang, X.; Xu, P.; Sun, J. Facile one-pot synthesis of Zn/Mg-MOF-74 with unsaturated coordination metal centers for efficient CO2 adsorption and conversion to cyclic carbonates. ACS Appl. Mater. Interf. 2021, 13, 61334–61345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, N.; Malik, A.; Jain, S.L. Light driven chemical fixation and conversion of CO2 into cyclic carbonates using transition metals: A review on recent advancements. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2024, 502, 215636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Guan, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, C.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, R.; Li, Z.; Fan, C. CeO2 nanorods with bifunctional oxygen vacancies for promoting low-pressure photothermocatalytic CO2 conversion with CH3OH to dimethyl carbonate. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 111374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; Jin, Y.; Yang, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, C.; Guan, G.; Li, Z. Boosting photothermal CO2 conversion to dimethyl carbonate through Ce3+-Ov-Ce3+ active centers on CeO2-(110) nanotube. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 514, 163317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, G.; Wang, Q.; Xu, D.; Fan, H.; Liu, K.; Li, Y.; Gu, X.K.; Ding, M. Dimethyl carbonate synthesis from CO2 over CeO2 with electron-enriched lattice oxygen species. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202402053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.; Gao, Y. Morphology-dependent surface chemistry and catalysis of CeO2 nanocrystals. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2014, 4, 3772–3784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhao, L.; Wang, W.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, G.; Ma, X.; Gong, J. Morphology control of ceria nanocrystals for catalytic conversion of CO2 with methanol. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 5582–5588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Huang, S.; Zhao, Y.; Ma, X.; Wang, S. CeO2 hollow nanosphere for catalytic synthesis of dimethyl carbonate from CO2 and methanol: The effect of cavity effect on catalytic performance. Asia-Pac. J. Chem. Eng. 2021, 16, e2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Jia, A.; Li, J.; Li, F.; Wang, Y. Investigation of synthesis parameters to fabricate CeO2 with a large surface and high oxygen vacancies for dramatically enhanced performance of direct DMC synthesis from CO2 and methanol. Mol. Catal. 2022, 528, 112471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z.L.; Huang, T.T.; Qi, L.X.; Cai, L.Z.; Lin, S.J.; Sun, J.; Xu, Z.N.; Guo, G.C. (311) High-Index Facet of CeO2 Effectively Promotes the Synthesis of Dimethyl Carbonate from CO2 and Methanol. ACS Appl. Mater. Interf. 2025, 17, 36784–36795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arduino, M.; Sartoretti, E.; Calì, E.; Bensaid, S.; Deorsola, F.A. Understanding the Role of Morphology in the Direct Synthesis of Diethyl Carbonate Over Ceria-Based Catalysts: An In Situ Infrared and High-Resolution TEM Study. ChemCatChem 2025, 17, e00140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.H.; Sun, Y.C.; Wei, Y.Y.; Wang, K.; Wang, W.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Z.Y.; Tian, Y.; Liu, Z.T. Synthesis of dimethyl carbonate from CO2 and methanol over CeO2 nanoparticles/Co3O4 nanosheets. Fuel 2022, 325, 124945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraju, G.; Prashanth, S.A.; Shivaraj, M.; Yathish, K.V.; Anupama, C.; Rangappa, D. Electrochemical heavy metal detection, photocatalytic, photoluminescence, biodiesel production and antibacterial activities of Ag–ZnO nanomaterial. Mater. Res Bull. 2017, 94, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.; Zhou, H.; Liu, H.; Liu, B.; Liang, M.; Guo, H. Controlled assemble of oxygen vacant CeO2@Bi2WO6 hollow magnetic microcapsule heterostructures for visiblelight photocatalytic activity. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 330, 1297–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezkrovnyi, O.S.; Lisiecki, R.; Kepinski, L. Relationship between morphology and structure of shape-controlled CeO2 nanocrystals synthesized by microwave assisted hydrothermal method. Cryst. Res. Technol. 2016, 51, 554–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimmel, G.; Sahartov, A.; Sadia, Y.; Porat, Z.; Zabicky, J.; Dvir, E. Non-monotonic lattice parameters variation with crystal size in nanocrystalline CeO2. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 12, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Zhao, X.L.; Li, J.; Bharti, B.; Tan, Y.L.; Long, H.Y.; Zhao, J.H.; Tian, G.; Wang, F. Investigation into the impact of CeO2 morphology regulation on the oxidation process of dichloromethane. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 12265–12277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Gong, B.; Pan, J.; Wang, Y.; Xia, H.; Zhang, H.; Dai, Q.; Wang, L.; Wang, X. Catalytic combustion of CVOCs over CrxTi1−x oxide catalysts. J. Catal. 2020, 391, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Li, C.; Zhang, G.; Yao, X.; Chuang, S.S.C.; Li, Z. Oxygen vacancy promoting dimethyl carbonate synthesis from CO2 and methanol over Zr-doped CeO2 nanorods. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 10446–10456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomishige, K.; Ikeda, Y.; Sakaihori, T.; Fujimoto, K. Catalytic properties and structure of zirconia catalysts for direct synthesis of dimethyl carbonate from methanol and carbon dioxide. J. Catal. 2000, 192, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Yao, W.X.; Yuan, L.Y.; Yang, J.; Gao, L.J.; Wu, G.D.; Hong, X.; Hu, L.H. Catalytic Synthesis of Dimethyl Carbonate from CO2 and Methanol with Rare Earth metals doped CeO2 nano-flowers. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2025, 175, 106293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomishige, K.; Kunimori, K. Catalytic and direct synthesis of dimethyl carbonate starting from carbon dioxide using CeO2-ZrO2 solid solution heterogeneous catalyst: Effect of H2O removal from the reaction system. Appl. Catal. A 2002, 237, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prymak, I.; Kalevaru, V.N.; Wohlrab, S.; Martin, A. Continuous synthesis of diethyl carbonate from ethanol and CO2 over Ce–Zr–O catalysts. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2015, 5, 2322–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Li, C.M.; Zhang, G.Q.; Yan, L.F.; Li, Z. Direct synthesis of dimethyl carbonate from CO2 and methanol over CaO-CeO2 catalysts: The role of acid-base properties and surface oxygen vacancies. New J. Chem. 2017, 41, 12231–12240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.T.; Xu, Y.P.; Bai, Z.L.; Wang, M.S.; Liu, B.W.; Xu, Z.N.; Guo, G.C. Boosting the catalytic activity via an acid–base synergistic effect for direct conversion of CO2 and methanol to dimethyl carbonate. New J. Chem. 2024, 48, 14727–14735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putro, W.S.; Munakata, Y.; Ijima, S.; Shigeyasu, S.; Hamura, S.; Matsumoto, S.; Mishima, T.; Tomishige, K.; Choi, J.C.; Fukaya, N. Synthesis of diethyl carbonate from CO2 and orthoester promoted by a CeO2 catalyst and ethanol. J. CO2 Util. 2022, 55, 101818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giram, G.G.; Bokade, V.V.; Darbha, S. Direct synthesis of diethyl carbonate from ethanol and carbon dioxide over ceria catalysts. New J. Chem. 2018, 42, 17546–17552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchmann, M.; Lucas, M.; Rose, M. Catalytic CO2 esterification with ethanol for the production of diethyl carbonate using optimized CeO2 as catalyst. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2021, 11, 1940–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

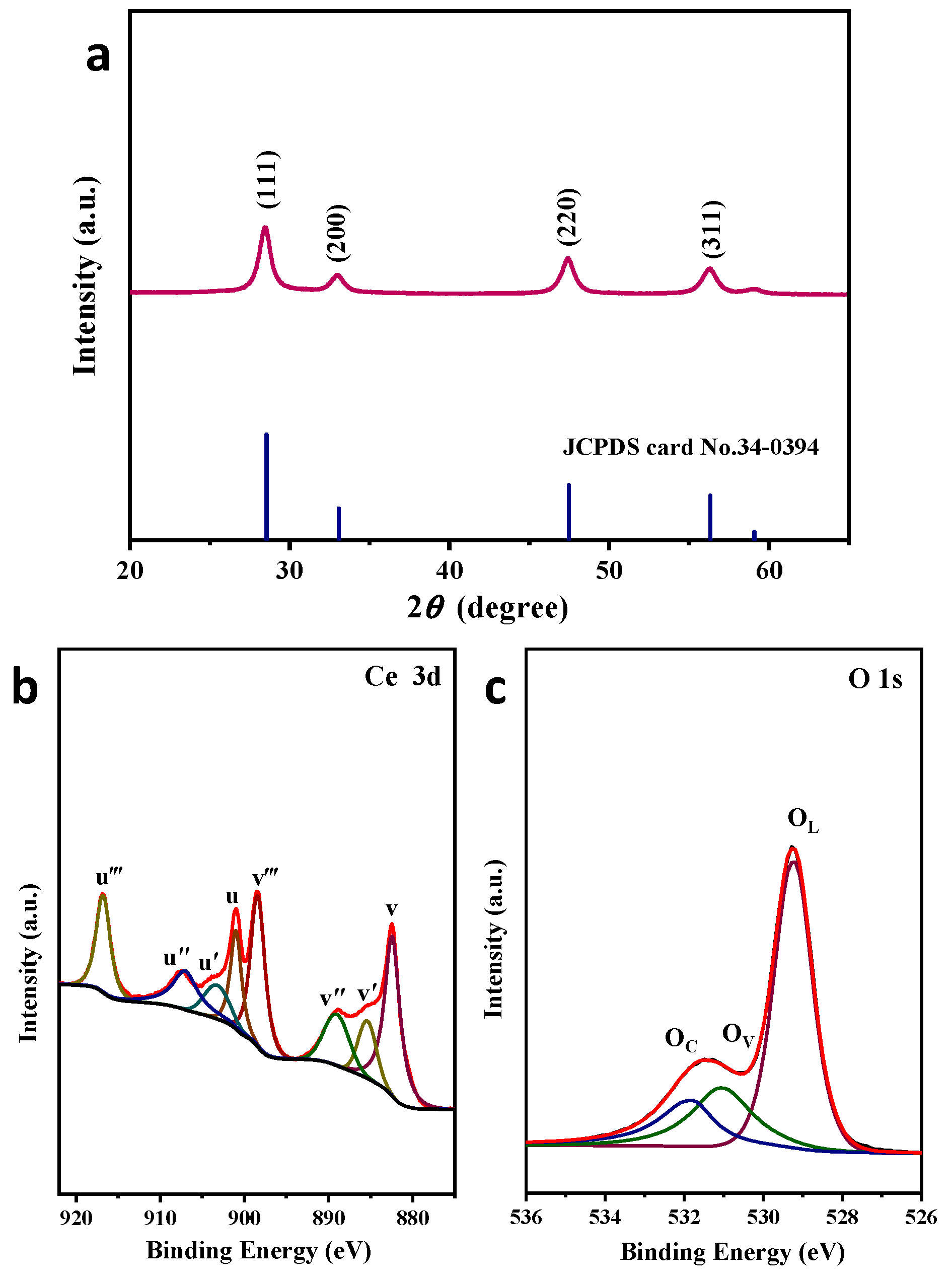

| Catalyst | Peak Position (2 θ) | FWHM | Crystallite Size D (nm) | Lattice Constant (A) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ce-NR | 28.540 | 0.659 | 8.46 | 5.412 |

| Ce-NP | 28.581 | 1.369 | 5.92 | 5.425 |

| Ce-NC | 28.556 | 0.318 | 25.44 | 5.411 |

| Catalyst | Ce3+/(Ce3+ + Ce4+) (%) | OV/(OL + OC + OV) (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Ce-NR | 21.1 ± 0.6 | 24.2 ± 0.2 |

| Ce-NC | 15.9 ± 0.2 | 20.5 ± 0.4 |

| Ce-NP | 14.6 ± 0.3 | 19.8 ± 0.3 |

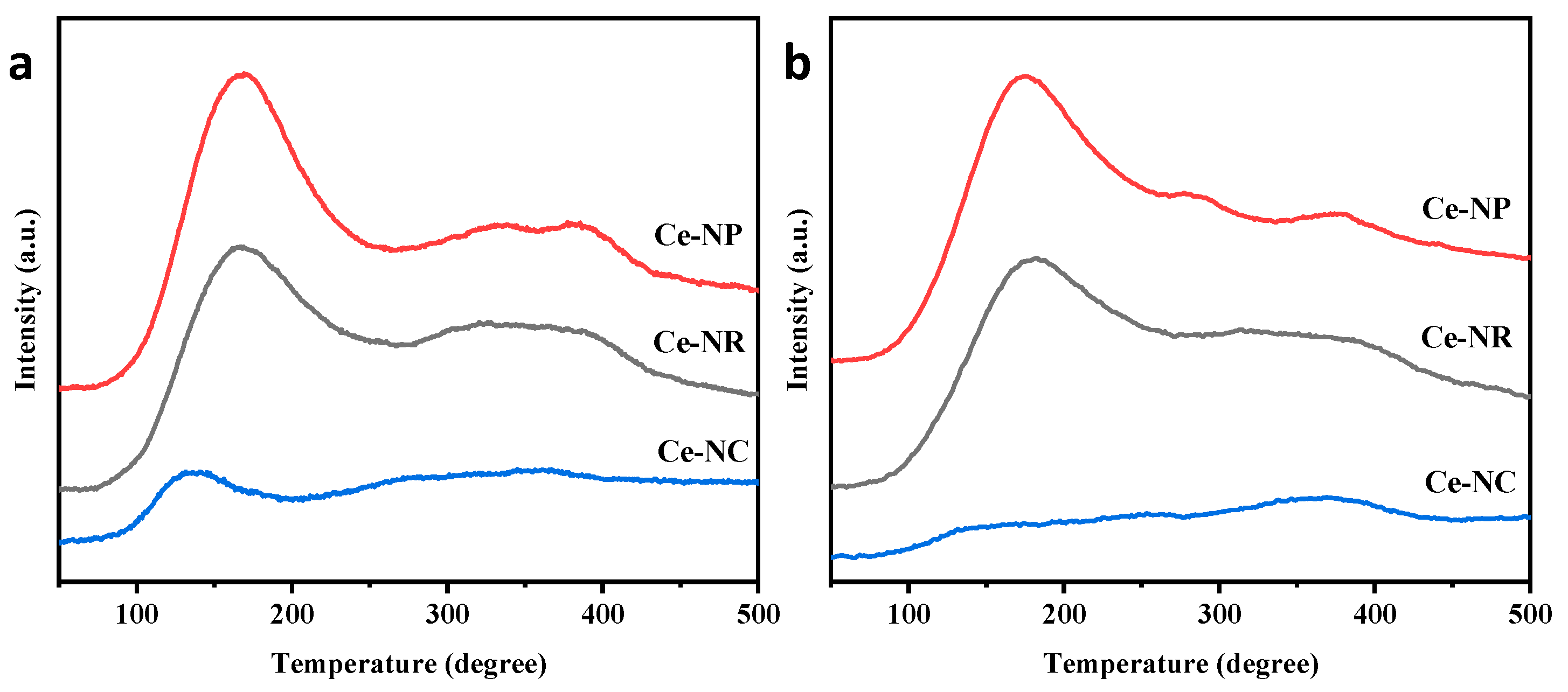

| Catalyst | Acidity (mmol/g) | Basicity (mmol/g) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weak | Moderate | Total | Weak | Moderate | Total | |

| Ce-NR | 0.32 | 0.31 | 0.62 | 0.29 | 0.27 | 0.56 |

| Ce-NP | 0.44 | 0.38 | 0.82 | 0.45 | 0.42 | 0.87 |

| Ce-NC | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.17 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chen, S.; Chen, Y.; Yin, J.; Deng, G.; Xu, J.; Wang, F.; Xue, B. Morphology Dependence of Catalytic Properties of CeO2 Nanocatalysts for One-Step CO2 Conversion to Diethyl Carbonate. Catalysts 2026, 16, 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010058

Chen S, Chen Y, Yin J, Deng G, Xu J, Wang F, Xue B. Morphology Dependence of Catalytic Properties of CeO2 Nanocatalysts for One-Step CO2 Conversion to Diethyl Carbonate. Catalysts. 2026; 16(1):58. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010058

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Siru, Yiwen Chen, Jun Yin, Guocheng Deng, Jie Xu, Fei Wang, and Bing Xue. 2026. "Morphology Dependence of Catalytic Properties of CeO2 Nanocatalysts for One-Step CO2 Conversion to Diethyl Carbonate" Catalysts 16, no. 1: 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010058

APA StyleChen, S., Chen, Y., Yin, J., Deng, G., Xu, J., Wang, F., & Xue, B. (2026). Morphology Dependence of Catalytic Properties of CeO2 Nanocatalysts for One-Step CO2 Conversion to Diethyl Carbonate. Catalysts, 16(1), 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010058