Isotopic Labeling in IR Spectroscopy of Surface Species: A Powerful Approach to Advanced Surface Investigations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Full Isotopic Substitution

2.1. Theoretical Background

2.1.1. Diatomic Molecule and Isolated Vibrations Between Two Atoms

2.1.2. Polyatomic Molecules

2.2. Tracing Vibrations Involving Specific Atoms

2.3. Differentiating Vibrations in Coexisting Surface Species

2.4. Controlling Fermi Resonance

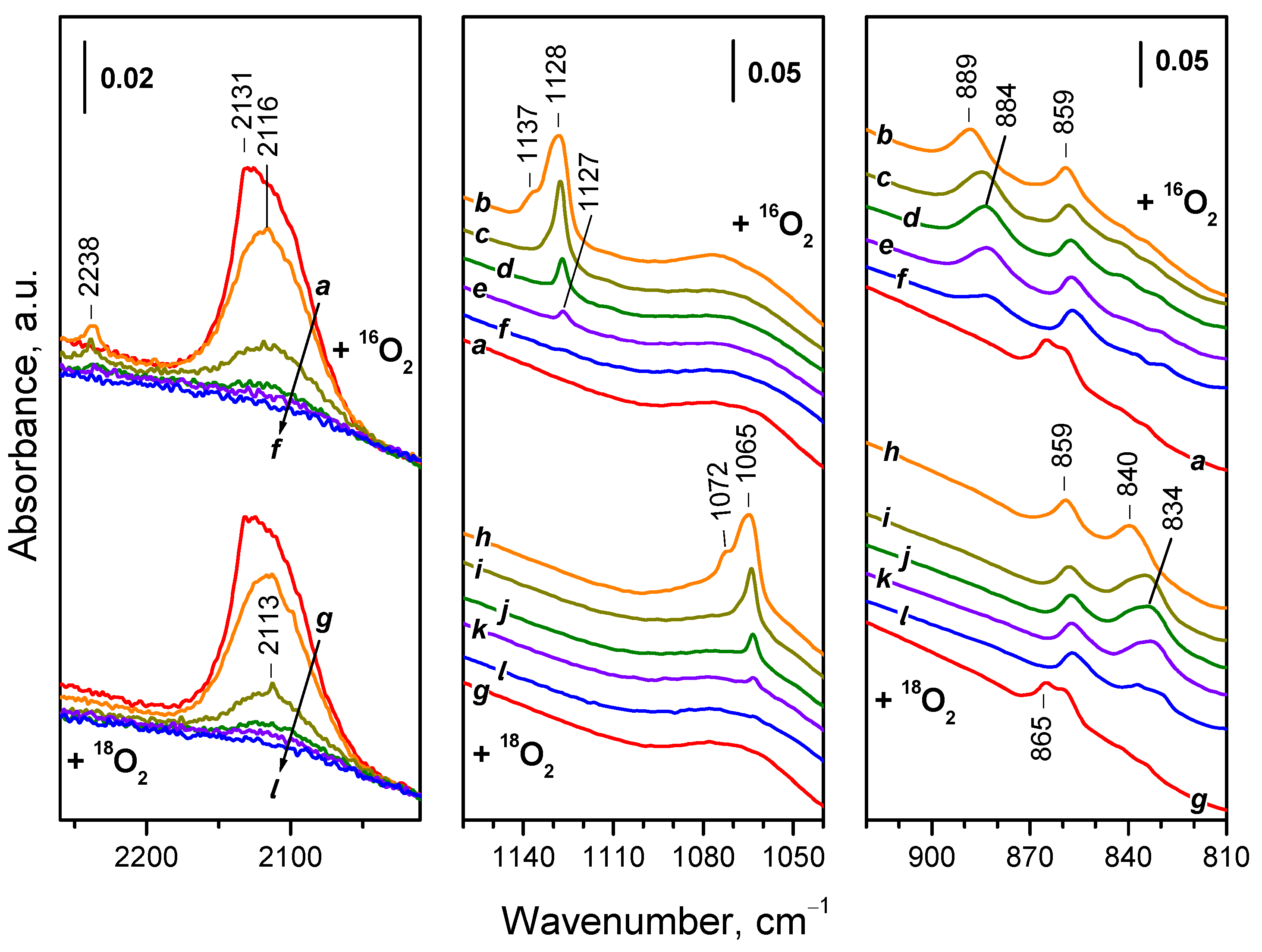

2.5. Identifying Atomic Origins in Surface Species

2.6. Concluding Remarks

3. Trace-Level Isotopic Substitution

3.1. Theoretical Background

3.2. Static and Dynamic Interactions Between Adsorbed Molecules

3.3. Number of Coordination Vacancies

3.4. Concluding Remarks

4. Intermediate-Level Isotopic Substitution

4.1. Theoretical Background

4.2. Structure and Formation Pathways of Diatomic Species

4.3. Polyatomic Species with Identical Atoms

4.4. Surface AB3 Structures

4.5. Surface AB4 Structures

4.6. Linkage Isomerism of Labeled Probes for Adsorption Mode Determination

4.7. Di-Ligand Surface Complexes

4.8. Triligand Surface Complexes

- (i)

- the approximate force-field model predicts two bands (at 2047 and 1926 cm−1) for mixed-ligand dicarbonyls, which should dominate the spectrum—but they do not;

- (ii)

- intense bands such as those at 2065 and 1969 cm−1 cannot be assigned to dicarbonyls;

- (iii)

- for species with identical CO ligands (2069 and 1991 cm−1 for 12CO), the experimental intensities should be about twice lower than those in the synthetic spectrum, which is not observed.

4.9. Concluding Remarks

5. Isotopic Studies in Revealing Catalytic Reaction Mechanisms

5.1. Intermediate and Spectator Species

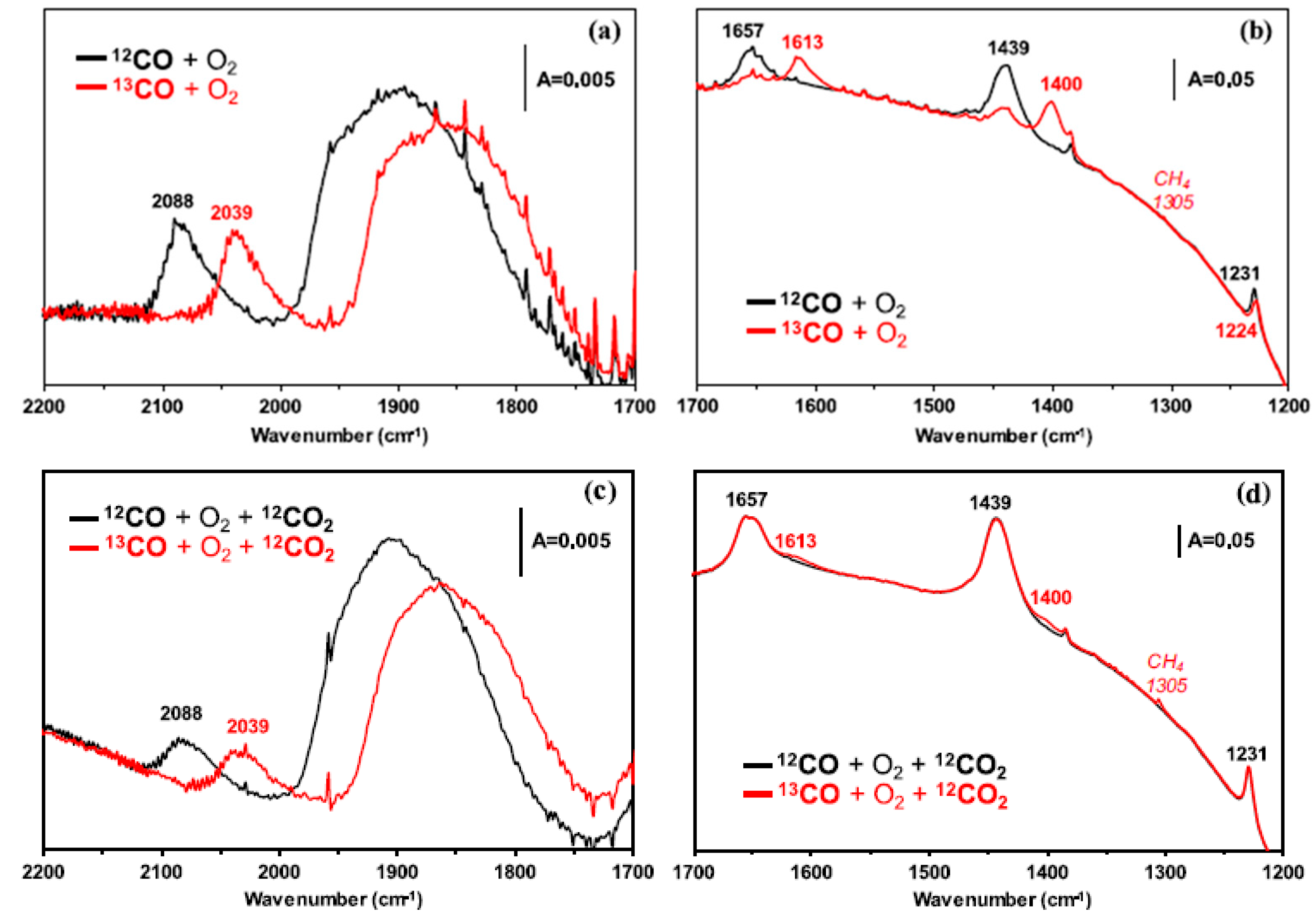

5.2. Trajectory of the Reactants’ Atoms

5.3. Active Sites and Structural Evolution of Catalysts Under Reaction Conditions

5.4. Emerging Approaches

5.4.1. Mixed-Isotope Operando Infrared Spectroscopy (MIOIRS)

5.4.2. Expanding the Scope of Catalytic Systems

5.4.3. Emerging Advanced Operando IR Modalities

6. Conclusions and Perspectives

6.1. Complementary Insights Provided by Isotopic Substitution in IR Spectroscopy

6.2. Synergies with Complementary Techniques

6.3. Future Directions and Emerging Opportunities

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Terenin, A.; Filimonov, V. Hydrogen bonds between adsorbed molecules and the structural hydroxyl groups at the surface of solids. In Hydrogen Bonding; Hadži, D., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1959; pp. 545–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, G.C.; Garland, C.W.; Jura, G. Infrared spectra of heavy water adsorbed on silica gel. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1953, 75, 803–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eischens, R.P.; Pliskin, W.A. The infrared spectra of adsorbed molecules. Adv. Catal. 1958, 10, 1–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peri, J.B. in Infrared spectroscopy in catalytic research. Catal. Sci. Technol. 1984, 5, 171–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, N. 50 years in vibrational spectroscopy at the gas/solid interface. In Surface Chemistry and Catalysis; Carley, A.F., Davies, P.R., Hutchings, G.J., Spencer, M.S., Eds.; Kluwer Acadernic/Plenum Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2002; Chapter 3; pp. 27–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinchas, S.; Laulicht, I. Infrared Spectra of Labelled Compounds; Academic press: London, UK, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Hadjiivanov, K.; Mihaylov, M.; Panayotov, D.; Ivanova, E.; Chakarova, K. Isotopes in the FTIR investigations of solid surfaces. In Spectroscopic Properties of Inorganic and Organometallic Compounds; Douthwaite, R., Duckett, S., Yarwood, J., Eds.; The Royal Society of Chemistry: London, UK, 2014; Volume 45, pp. 43–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://ciaaw.org (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Hadjiivanov, K. Identification and characterization of surface hydroxyl groups by infrared spectroscopy. Adv. Catal. 2014, 57, 99–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakarova, K.; Nikolov, P.; Hadjiivanov, K. Different Brønsted acidity of H−ZSM-5 and D−ZSM-5 zeolites revealed by the FTIR spectra of adsorbed CD3CN. Catal. Commun. 2013, 41, 38–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakarova, K.; Hadjiivanov, K. H-bonding of zeolite hydroxyls with weak bases: FTIR study of CO and N2 adsorption on H–D–ZSM-5. J. Phys. Chem. C 2011, 115, 4806–4817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihaylov, M.Y.; Zdravkova, V.R.; Ivanova, E.Z.; Aleksandrov, H.A.; Petkov, P.S.; Vayssilov, G.N.; Hadjiivanov, K.I. Infrared spectra of surface nitrates: Revision of the current opinions based on the case study of ceria. J. Catal. 2021, 394, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vayssilov, G.N.; Mihaylov, M.; Petkov, P.S.; Hadjiivanov, K.I.; Neyman, K.M. Reassignment of the vibrational spectra of carbonates, formates, and related surface species on ceria: A combined density functional and infrared spectroscopy investigation. J. Phys. Chem. C 2011, 115, 23435–23454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teles, J.H.; Maier, G.; Hess, L.A., Jr.; Schaad, L.J.; Winnewisser, M.; Winnewisser, B.P. The CHNO isomers. Chem. Ber. 1989, 122, 753–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, B.A.; Cody, I.A. Infra-red studies of reactions on oxide surfaces. Part 3.—HCN and C2N2 on silica. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 1 1975, 71, 1021–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bion, N.; Saussey, J.; Hedouin, C.; Seguelong, T.; Daturi, M. Evidence by in situ FTIR spectroscopy and isotopic effect of new assignments for isocyanate species vibrations on Ag/Al2O3. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2001, 3, 4811–4816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakarova, K.K.; Karapenchev, B.S.; Drenchev, N.L.; Ivanova, E.Z.; Aleksandrov, H.A.; Panayotov, D.A.; Mihaylov, M.Y.; Vayssilov, G.N.; Hadjiivanov, K.I. FTIR study of low-temperature CO adsorption on reduced ceria nanoparticles with different morphology: A comparison with oxidized samples. J. Catal. 2025, 443, 115986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binet, C.; Daturi, M.; Lavalley, J.-C. IR study of polycrystalline ceria properties in oxidised and reduced states. Catal. Today 1999, 50, 207–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakarova, K.; Drenchev, N.; Mihaylov, M.; Hadjiivanov, K.I. Interaction of O2 with reduced ceria nanoparticles at 100–400 K: Fast oxidation of Ce3+ ions and dissolved H2. Catalysts 2024, 14, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binet, C.; Badri, A.; Lavalley, J.-C. A spectroscopic characterization of the reduction of ceria from electronic transitions of intrinsic point defects. J. Phys. Chem. 1994, 98, 6392–6398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakabayashi, F.; Kondo, J.N.; Domen, K.; Hirose, C. FT-IR study of H218O adsorption on H-ZSM-5: Direct evidence for the hydrogen-bonded adsorption of water. J. Phys. Chem. 1996, 100, 1442–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelmenschikov, A.G.; van Santen, R.A.; Jänchen, J.J.; Meijer, E.L. CD3CN as a probe of Lewis and Bronsted acidity of zeolites. J. Phys. Chem. 1993, 97, 11071–11074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kustov, L.M.; Kazanskii, V.B.; Beran, S.; Kubelkova, L.; Jiru, P. Adsorption of carbon monoxide on ZSM-5 zeolites: Infrared spectroscopic study and quantum-chemical calculations. J. Phys. Chem. 1987, 91, 5247–5251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamotte, J.; Morávek, V.; Bensitel, M.; Lavalley, J.C. FT-IR study of the structure and reactivity of methoxy species on ThO2 and CeO2. React. Kinet. Catal. Lett. 1988, 36, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagoz, B.; Hu, T.; Stenlid, J.H.; Hu, Z.; Soldemo, M.; Abild-Pedersen, F.; Marks, K.; Öström, H.; Stacchiola, D.; Weissenrieder, J.; et al. Cryogenic carbon monoxide oxidation on cuprous oxide. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, e15673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrotvorskaia, A.N.; Pestsov, O.S.; Tsyganenko, A.A. Lateral interaction between molecules adsorbed on the surfaces of non-metals. Top. Catal. 2017, 60, 1506–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjiivanov, K.; Lamotte, J.; Lavalley, J.-C. FTIR study of low-temperature CO adsorption on pure and ammonia-precovered TiO2 (anatase). Langmuir 1997, 13, 3374–3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.J.; Cesano, F.; Chowdhury, A.R.; Trad, T.; Cravanzola, S.; Martra, G.; Mino, L.; Zecchina, A.; Scarano, D. Surface structure and phase composition of TiO2 P25 particles after thermal treatments and HF etching. Front. Mater. 2020, 7, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drenchev, N.; Lagunov, O.; Hadjiivanov, K.I. Coordination chemistry of Ca2+ sites in CaX zeolite: FTIR evidence of three coordination vacancies per cation. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2023, 362, 112768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drenchev, N.L.; Ivanova, E.Z.; Mihaylov, M.Y.; Aleksandrov, H.A.; Vayssilov, G.N.; Hadjiivanov, K.I. One Ca2+ site in CaNaY zeolite can attach three CO2 molecules. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2023, 14, 1564–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakarova, K.; Mihaylov, M.; Hadjiivanov, K. Can two CO2 molecules be simultaneously bound to one Na+ site in NaY zeolite? A detailed FTIR investigation. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2022, 345, 112270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagunov, O.; Drenchev, N.; Chakarova, K.; Panayotov, D.; Hadjiivanov, K. Isotopic labelling in vibrational spectroscopy: A technique to decipher the structure of surface species. Top. Catal. 2017, 60, 1486–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldt, C.D.; Moreira, R.; Meyer, E.; Clawin, P.; Riedel, W.; Risse, T.; Moskaleva, L.; Dononelli, W.; Klüner, T. CO adsorption on Au(332): Combined infrared spectroscopy and density functional theory study. J. Phys. Chem. C 2019, 123, 8187–8197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollins, P. Effects of dipolar coupling on the intensity of infrared absorption bands from supported metal catalysts. Spectrochim. Acta A 1987, 43, 1539–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakarova, K.; Mihaylov, M.; Ivanova, S.; Centeno, M.A.; Hadjiivanov, K. Well defined negatively charged gold carbonyls on Au/SiO2. J. Phys. Chem. C 2011, 115, 21273–21282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunathunge, C.M.; Li, J.; Li, X.; Waegele, M.M. Surface-adsorbed CO as an infrared probe of electrocatalytic interfaces. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 11700−11711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monai, M. A new look at catalyst surfaces at work: Introducing mixed isotope operando infrared spectroscopy (MIOIRS). ACS Catal. 2025, 15, 1363−1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjiivanov, K. Application of isotopically labelled IR probe molecules for characterization of porous materials. In Ordered Poropus Solids; Valtchev, V., Mintova, S., Tsapatis, M., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 263–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagunov, O.; Chakarova, K.; Hadjiivanov, K. Silver-catalyzed low-temperature CO isotopic scrambling reaction: 12C16O + 13C18O → 12C18O + 13C16O. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2012, 14, 2178–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjiivanov, K. Identification of neutral and charged surface NOx species by IR spectroscopy. Catal. Rev.—Sci. Eng. 2000, 42, 71–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjiivanov, K.; Saussey, J.; Freysz, J.-L.; Lavalley, J.-C. FTIR study of NO + O2 co-adsorption on H-ZSM-5: Re-assignment of the 2133 cm-1 band to NO+ species. Catal. Lett. 1998, 52, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.Y.; Kollar, M.; Wei, Z.; Gao, F.; Wang, Y.; Szanyi, J.; Peden, C.H.F. Formation of NO+ and its possible roles during the selective catalytic reduction of NOX with NH3 on Cu-CHA catalysts. Catal. Today 2019, 320, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khivantsev, K.; Kwak, J.-H.; Jaegers, N.R.; Koleva, I.Z.; Vayssilov, G.N.; Derewinski, M.D.; Wang, Y.; Aleksandrov, H.D.; Szanyi, J. Identification of the mechanism of NO reduction with ammonia (SCR) on zeolite catalysts. Chem. Sci. 2022, 13, 10383–10394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihaylov, M.Y.; Ivanova, E.Z.; Aleksandrov, H.A.; Petkov, P.S.; Vayssilov, G.N.; Hadjiivanov, K.I. FTIR and density functional study of NO interaction with reduced ceria: Identification of N3− and NO2− as new intermediates in NO conversion. Appl. Catal. B 2015, 176–177, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsyganenko, A.; Aminev, T.; Baranov, D.; Pestsov, O. FTIR spectroscopy of adsorbed ozone. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2020, 761, 138071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminev, T.; Krauklis, I.; Pestsov, O.; Tsyganenko, A. Ozone activation on TiO2 studied by IR spectroscopy and quantum chemistry. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butova, V.V.; Burachevskaia, O.A.; Drenchev, N.D.; Tereshchenko, A.A.; Hadjiivanov, K.I. FTIR probing acidic and defective sites in sulfated UiO-66 and ZrO2 via adsorptive FTIR spectroscopy. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacQueen, B.; Ruiz-Yi, B.; Royko, M.; Heyden, A.; Pagan-Torres, Y.J.; Williams, C.; Lauterbach, J. In-situ oxygen isotopic exchange vibrational spectroscopy of rhenium oxide surface structures on cerium oxide. J. Phys. Chem. C 2020, 124, 7174−7181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriopoulou, C.; Kentria, T.; Boghosian, S. Vibrational spectroscopy of dispersed ReVIIOx sites supported on monoclinic zirconia. Dalton Trans. 2024, 53, 4020–4034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drenchev, N.; Aleksandrov, H.A.; Vayssilov, G.N.; Shivachev, B.; Hadjiivanov, K. Why does CaX zeolite have such a high CO2 capture capacity and how is it affected by water? Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 349, 127662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortorelli, M.; Chakarova, K.; Lisi, L.; Hadjiivanov, K. Disproportionation of associated Cu2+ sites in Cu−ZSM-5 to Cu+ and Cu3+ and FTIR detection of Cu3+(NO)x ( x = 1, 2) species. J. Catal. 2014, 309, 376–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felvey, N.; Guo, J.; Rana, R.; Xu, L.; Bare, S.R.; Gates, B.C.; Katz, A.; Kulkarni, A.R.; Runnebaum, R.C.; Kronawitter, C.X. Interconversion of atomically dispersed platinum cations and platinum clusters in zeolite ZSM-5 and formation of platinum gem-dicarbonyls. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 13874−13887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihaylov, M.; Lagunov, O.; Ivanova, E.; Hadjiivanov, K. Nature of the polycarbonyl species on Ru/ZrO2: Re-assignment of some carbonyl bands. J. Phys. Chem. C 2011, 115, 13860–13867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrzyk, P.; Podolska-Serafin, K.; Góra-Marek, K.; Krasowska, A.; Sojka, Z. Redox states of nickel in zeolites and molecular account into binding of N2 to nickel(I) centers—IR, EPR and DFT study. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2020, 291, 109692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miessner, H.; Richter, K. Well-defined carbonyl and dinitrogen complexes of ruthenium supported on dealuminated Y zeolite. Analogies and differences to the homogeneous case. J. Mol. Catal. A 1999, 146, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, E.; Mihaylov, M.; Aleksandrov, H.; Daturi, M.; Thibault-Starzyk, F.; Vayssilov, G.; Rösch, N.; Hadjiivanov, K. Unusual carbonyl-nitrosyl complexes of Rh2+ in Rh-ZSM-5: A combined FTIR spectroscopy and computational study. J. Phys. Chem. C 2007, 111, 10412–10418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velisoju, V.K.; Kulkarni, S.R.; Cui, M.; Rabee, A.I.M.; Paalanen, P.; Rabeah, J.; Maestri, M.; Brückner, A.; Ruiz-Martinez, J.; Castaño, P. Multi-technique operando methods and instruments for simultaneous assessment of thermal catalysis structure, performance, dynamics, and kinetics. Chem. Catal. 2023, 3, 100666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Cheng, W.; Su, H.; Zhao, X.; He, J.; Liu, Q. Operando infrared spectroscopic insights into the dynamic evolution of liquid-solid (photo)electrochemical interfaces. Nano Energy 2020, 77, 105121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portela, R.; Perez-Ferreras, S.; Serrano-Lotina, A.; Bañares, M.A. Engineering operando methodology: Understanding catalysis in time and space. Front. Chem. Sci. Eng. 2018, 12, 509–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmen, A.; Yang, J.; Chen, D. Steady-state isotopic transient kinetic analysis (SSITKA). In Springer Handbook of Advanced Catalyst Characterization; Wachs, I.E., Bañares, M.A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatoum, I.; Richard, M.; Dujardin, C. Insight into the true role of hydrogen-carbonate species in CO oxidation over Pd/Al2O3 catalyst using SSITKA-transmission IR technique. Catal. Commun. 2023, 179, 106684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatoum, I.; Bouchoul, N.; Richard, M.; Dujardin, C. Revealing origin of hydrogen-carbonate species in CO oxidation over Pt/Al2O3: A SSITKA-IR study. Top. Catal. 2022, 66, 915–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Hernández, J.J.; Fernandes de Almeida, V.; Abou-Khalil, Z.; Ferrer, B.; Llabrés i Xamena, F.X.; Daturi, M.; Clet, G.; Vayá, I.; Baldoví, H.G.; Dhakshinamoorthy, A.; et al. Photo-thermal catalytic CO2 methanation by RuOx@MIL-101(Cr) with 9.2% apparent quantum yield under visible light irradiation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 49485–49499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Shi, H.; Szanyi, J. Controlling selectivities in CO2 reduction through mechanistic understanding. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meunier, F.C.; Tibiletti, D.; Goguet, A.; Shekhtman, S.; Hardacre, C.; Burch, R. On the complexity of the water-gas shift reaction mechanism over a Pt/CeO2 catalyst: Effect of the temperature on the reactivity of formate surface species studied by operando DRIFT during isotopic transient at chemical steady-state. Catal. Today 2007, 126, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meunier, F.C. The power of quantitative kinetic studies of adsorbate reactivity by operando FTIR carried out at chemical-potential steady state. Catal. Today 2010, 155, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meunier, F.C. Hydrogenation of CO and CO2: Contributions of IR operando studies. Catal. Today 2023, 423, 113863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, A.R.; Moulijn, J.A.; Mul, G. Photocatalytic oxidation of cyclohexane over TiO2: Evidence for a Mars−van Krevelen mechanism. J. Phys. Chem. C 2011, 115, 1330–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Ding, Q.; Wang, X.; Feng, Z.; Li, C. Mechanistic studies on photocatalytic overall water splitting over Ga2O3-based photocatalysts by operando MS-FTIR spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2021, 12, 6029–6033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubota, H.; Liu, C.; Toyao, T.; Maeno, Z.; Ogura, M.; Nakazawa, N.; Inagaki, S.; Kubota, Y.; Shimizu, K. Formation and reactions of NH4NO3 during transient and steady-state NH3-SCR of NOx over H-AFX zeolites: Spectroscopic and theoretical studies. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 2334−2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Peng, Y.; Li, K.; Liu, S.; Chen, J.; Li, J.; Gao, F.; Peden, C.H.F. Using transient FTIR spectroscopy to probe active sites and reaction intermediates for selective catalytic reduction of NO on Cu/SSZ-13 catalysts. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 6137−6145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, R.; Zhang, C.; Gao, Y.; Wang, Q.; Efstathiou, A.M. Unravelling the multiple effects of H2O on the NH3-SCR over Mn2Cu1Al1Ox-LDO by transient kinetics and in situ DRIFTS. Appl. Catal. B 2025, 361, 124611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groppo, E.; Rojas-Buzo, S.; Bordiga, S. The role of in situ/operando IR spectroscopy in unraveling adsorbate-induced structural changes in heterogeneous catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 12135−12169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morandi, S.; Castoldi, L.; Matarrese, R. In-situ and operando FT-IR investigation of Pd speciation in Pd/SSZ-13: The pivotal role of CO and NO adsorption with and without H2O. Appl. Catal. A 2025, 708, 120592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Wachs, I.E. An operando Raman, IR, and TPSR spectroscopic investigation of the selective oxidation of propylene to acrolein over a model supported vanadium oxide monolayer catalyst. J. Phys. Chem. C 2008, 112, 11363–11372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamoud, H.I.; Damacet, P.; Fan, D.; Assaad, N.; Lebedev, O.I.; Krystianiak, A.; Gouda, A.; Heintz, O.; Daturi, M.; Maurin, G.; et al. Selective photocatalytic dehydrogenation of formic acid by an in situ-restructured copper-postmetalated metal−organic framework under visible light. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 12, 16433–16446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Xu, Y.; Fu, L.; Chang, X.; Xu, B. Experimental evidence of distinct sites for CO2-to-CO and CO conversion on Cu in the electrochemical CO2 reduction reaction. Nat. Catal. 2023, 6, 885–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Li, Y.; Lei, M.; Polo-Garzon, F.; Perez-Aguilar, J.; Bare, S.R.; Formo, E.; Kim, H.; Daemen, L.; Cheng, Y.; et al. Significant roles of surface hydrides in enhancing the performance of a Cu/BaTiO2.8H0.2 catalyst for CO2 hydrogenation to methanol. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202313389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamoud, H.I.; Wolski, L.; Pankin, I.; Bañares, M.A.; Daturi, M.; El-Roz, M. In situ and operando spectroscopies in photocatalysis: Powerful techniques for a better understanding of the performance and the reaction mechanism. Top. Curr. Chem. 2022, 380, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Berkel, D.V.; Urakawa, A. Exploiting the continuity equation for mechanistic understanding through spatially resolved SSITKA-DRIFTS: The role of carbonyls in RWGS over Pt/CeO2. J. Catal. 2024, 433, 115470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Jiang, J.; Cheng, W.; Su, H.; Liu, Q. In-situ synchrotron radiation infrared spectroscopic identification of reactive intermediates over multiphase electrocatalytic interfaces. Chin. J. Struct. Chem. 2022, 41, 221000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.N.; Mei, B.; Xu, Q.; Fu, H.Q.; Zhang, X.Y.; Liu, P.F.; Jiang, Z.; Yang, H.G. In situ/operando synchrotron radiation analytical techniques for CO2/CO reduction reaction: From atomic scales to mesoscales. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202404213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iijima, G.; Naruse, J.; Shingai, H.; Usami, K.; Kajino, T.; Yoto, H.; Morimoto, Y.; Nakajima, R.; Inomata, T.; Masuda, H. Mechanism of CO2 capture and release on redox-active organic electrodes. Energy Fuels 2023, 37, 2164–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Initial Bond | After Substitution | i | Decrease in ν, % | 1/i |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H–H | H–D | 0.8661 | 13.39 | 1.155 |

| D–D | 0.7074 | 29.26 | 1.414 | |

| 12C–H | 12C–D | 0.7342 | 26.58 | 1.362 |

| 13C–H | 0.9970 | 0.30 | 1.003 | |

| 13C–D | 0.7301 | 26.99 | 1.370 | |

| 14N–H | 14N–D | 0.7307 | 26.93 | 1.369 |

| 15N–H | 0.9978 | 0.22 | 1.002 | |

| 15N–D | 0.7276 | 27.24 | 1.374 | |

| 16O–H | 16O–D | 0.7280 | 27.20 | 1.374 |

| 18O–H | 0.9967 | 0.33 | 1.003 | |

| 18O–D | 0.7235 | 27.65 | 1.382 | |

| 12C–12C | 12C–13C | 0.9806 | 1.94 | 1.020 |

| 13C–13C | 0.9606 | 3.94 | 1.041 | |

| 12C–14N | 12C–15N | 0.9845 | 1.55 | 1.016 |

| 13C–14N | 0.9790 | 2.10 | 1.022 | |

| 13C–15N | 0.9632 | 3.68 | 1.038 | |

| 12C–16O | 12C–18O | 0.9758 | 2.42 | 1.025 |

| 13C–16O | 0.9777 | 2.23 | 1.023 | |

| 13C–18O | 0.9530 | 4.70 | 1.049 | |

| 14N–14N | 14N–15N | 0.9832 | 1.68 | 1.017 |

| 15N–15N | 0.9662 | 3.38 | 1.035 | |

| 14N–16O | 14N–18O | 0.9737 | 2.63 | 1.027 |

| 15N–16O | 0.9821 | 1.79 | 1.018 | |

| 15N–18O | 0.9553 | 4.47 | 1.047 | |

| 16O–16O | 16O–18O | 0.9719 | 2.82 | 1.029 |

| 18O–18O | 0.9427 | 5.73 | 1.061 | |

| 32S–16O | 34S–16O | 0.9719 | 2.82 | 1.029 |

| 35Cl–16O | 37Cl–16O | 0.9719 | 2.82 | 1.029 |

| B/B* Ratio | AB2 | ABB* | AB*2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1:1 | 25.0 | 50.0 | 25.0 |

| 3:1 | 56.25 | 37.5 | 6.25 |

| B/B* Ratio | AB3 | AB2B* | ABB*2 | AB*3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1:1 | 12.5 | 37.5 | 37.5 | 12.5 |

| 3:1 | 42.2 | 42.2 | 14.0 | 1.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hadjiivanov, K.; Panayotov, D.; Mihaylov, M. Isotopic Labeling in IR Spectroscopy of Surface Species: A Powerful Approach to Advanced Surface Investigations. Catalysts 2026, 16, 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010057

Hadjiivanov K, Panayotov D, Mihaylov M. Isotopic Labeling in IR Spectroscopy of Surface Species: A Powerful Approach to Advanced Surface Investigations. Catalysts. 2026; 16(1):57. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010057

Chicago/Turabian StyleHadjiivanov, Konstantin, Dimitar Panayotov, and Mihail Mihaylov. 2026. "Isotopic Labeling in IR Spectroscopy of Surface Species: A Powerful Approach to Advanced Surface Investigations" Catalysts 16, no. 1: 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010057

APA StyleHadjiivanov, K., Panayotov, D., & Mihaylov, M. (2026). Isotopic Labeling in IR Spectroscopy of Surface Species: A Powerful Approach to Advanced Surface Investigations. Catalysts, 16(1), 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010057