Catalytic Combustion of Low-Concentration Methane: From Mechanistic Insights to Industrial Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research on the Reaction Mechanism of Catalytic Combustion of Low-Concentration Methane

3. Research on Catalysts for Methane Catalytic Combustion

3.1. Noble Metal Catalysts

3.1.1. Pd-Based Catalysts

| Catalyst System | Support Type | Typical CH4 Concentration Range (vol%) | T50/T90 (°C) | Notable Features (Activity, Stability, Poisoning Resistance) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pd/PdO | γ-Al2O3, CeO2, zeolites | 0.1–1.0; up to a few vol% | 320–380/380–450 | Very high low—T activity; sensitive to H2O/SO2; sintering—prone |

| Pt-based | Al2O3, CeO2 | 0.1–1.0; few vol% | 380–450/450–550 | Lower activity than Pd; excellent sulfur and thermal stability |

| Rh-based | Zeolites, CeO2 | 0.1–1.0; few vol% | 360–430/430–520 | High tolerance to H2O/SO2; good NOx removal |

| Perovskites (LaBO3) | Self-supported/monolith | 0.1–1.0; few vol% | 450–520/520–600 | Good thermal stability; moderate low—T activity |

| Spinels (AB2O4) | Self-supported/monolith | 0.1–1.0; few vol% | 360–430/430–520 | Good low—T activity; sintering at high T |

| Hexaaluminates | Self-supported/monolith | 0.1–1.0 | 500–580/580–700 | Excellent high—T stability; limited low—T activity |

| Carbon-supported metal | Activated carbon, CNTs | 0.1–1.0 | 360–430/430–520 | Hydrophobic; resistant to H2O/SO2 at moderate T |

3.1.2. Pt-Based Catalysts

3.1.3. Rh and Au Catalysts

3.1.4. Supports

- (1)

- Zeolite Supports

- (2)

- Metal Oxide Supports

3.2. Non-Precious Metal Catalysts

4. Advancements and Numerical Insights in Combustion Utilization of Low-Concentration Methane

4.1. Research on Combustion Utilization Methods for Low-Concentration Methane

4.2. Numerical Simulation of Low-Concentration Methane Combustion

5. Limitations and Challenges

5.1. Mismatch Between Catalyst Performance and Operational Conditions

5.2. Insufficient Stability and Adaptability of Combustion Systems

5.3. Discrepancies Between Numerical Simulation and Actual Conditions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yuan, L. Theoretical and technological considerations for the safe and high-quality development of coal as China’s main energy source. Bull. Chin. Acad. Sci. 2023, 38, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Q.S.; Si, R.J.; Li, R.Z.; Wang, L. Experimental study on the influence of initial gas concentration on explosion temperature. J. Saf. Sci. Technol. 2021, 17, 37–42. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.Z.; Liu, J.F.; Zhang, G.Y. Distribution law of combustion temperature of low-concentration gas in porous media. J. Heilongjiang Univ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 28, 581–586. [Google Scholar]

- Rocky Mountain Institute. Prospects for Gas Recovery and Utilization Technology Development. October 2024. Available online: https://rmi.org.cn/insights/coal-mine-methane-recovery-and-utilization-technologies-development-trends-and-outlook/ (accessed on 21 November 2024).

- Zhang, Z.G.; Huo, C.X. Research progress on coal mine methane utilization technologies. Min. Saf. Environ. Prot. 2022, 49, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, Y.; Tang, S.; Chen, S.; Tang, D.; Li, Z. Deep coalbed methane production potential based on isothermal adsorption curves in the Ordos Basin of China. Energy Fuels 2025, 39, 7254–7267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Li, R.; Zhang, L.; Liu, J.; Wang, W.; Zhang, G. Catalyst-free partial oxidation of methane under ambient conditions boosted by mechanical stirring-enhanced ultrasonic cavitation. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 7506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, H.; Dai, Z.; Fu, C.; Ji, X.; Dong, Y.; Ge, M.; Long, R.; Bi, Y.; Xiong, Y. Constructing dynamic Rhδ+–Ov–Ti interfacial sites for highly efficient and stable photothermal catalytic methane dry reforming. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 38204–38214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amez, I.; Paredes, R.; León, D.; Bolonio, D.; Pantelakis, D.; Castells, B. New Experimental Approaches for the Determination of Flammability Limits in Methane–Hydrogen Mixtures with CO2 Inertization Using the Spark Test Apparatus. Fire 2024, 7, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krikunova, A.I.; Cheshko, A.D. Effect of Hydrogen Addition on the Methane-Air Combustion under Normal and Reversed Gravity. Acta Astronaut. 2025, 228, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Gao, J.; Wang, H.; Xie, M.; Du, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, D.; Dong, H.; Zhao, Z. Investigation of instability characteristics and lean-burn limit of methane/air laminar premixed flames at sub-atmospheric pressure. Fuel 2025, 384, 133788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liang, H.; Zhang, Q.; Ren, S. Propagation characteristics of methane/air explosions in pipelines under high temperature and pressure. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2025, 196, 106914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.Z. Design of High-Efficiency Catalysts for Catalytic Combustion of Methane and Study of Their Catalytic Performance. Master’s Thesis, Beijing University of Chemical Technology, Beijing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y. Study on Catalytic Combustion of Methane and Kinetic Characteristics over Mn-Ce-Cu Catalyst Under Pressure Conditions. Master’s Thesis, Chongqing University, Chongqing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Pi, D. Experimental Study on Catalytic Combustion of Low-Concentration Methane over Pd-Based Catalysts. Master’s Thesis, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, P.Q.; Wang, S.F.; Zhao, S.G.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, J.G.; Liu, Y.X.; Guo, M.; Duan, R.H. Research progress on reaction mechanism and catalysts for catalytic combustion of methane. J. Fuel Chem. Technol. 2022, 50, 180–194. [Google Scholar]

- Zasada, F.; Gryboś, J.; Hudy, C.; Janas, J.; Sojka, Z. Total oxidation of lean methane over cobalt spinel nanocubes—Mechanistic vistas gained from DFT modeling and catalytic isotopic investigations. Catal. Today 2020, 354, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.E.; Ok, Y.S.; Tsang, D.C.; Song, J.H.; Jung, S.C.; Park, Y.K. Recent advances in volatile organic compounds abatement by catalysis and catalytic hybrid processes: A critical review. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 719, 137405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Specchia, S.; Conti, F.; Specchia, V. Kinetic studies on Pd/CexZr1−xO2 catalyst for methane combustion. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2010, 49, 11101–11111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Xu, Y.; Feng, Q.; Leung, D. Low temperature catalytic oxidation of volatile organic compounds: A review. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2015, 5, 2649–2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Ye, N.; Situ, D.; Zuo, S.; Wang, X. Study of catalytic combustion of chlorobenzene and temperature programmed reactions over CrCeOx/AlFe pillared clay catalysts. Materials 2019, 12, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zhang, C.; Wang, J.; Li, H.; Duan, Y.; Liu, Z.; Lee, J.; Hu, X.; Xi, S.; Du, Y.; et al. The interplay between the suprafacial and intrafacial mechanisms for methane complete oxidation on substituted LaCoO3 perovskite oxides. J. Catal. 2020, 390, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Z.Y.; Tian, Q.L.; Wang, L.R.; Fu, Z.J.; Zhao, N.; Wang, X.B.; Huang, X. Study on performance of Pd-Pt/CeO2 catalysts prepared by flame spray pyrolysis for methane combustion. J. Fuel Chem. Technol. 2024, 52, 725–734. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.; Jiao, X.; Huang, G.B.; Wu, Y.L.; Song, Y.W.; Wang, X.B.; Wang, J.C. Research progress on Pd-based catalysts for catalytic combustion of methane. Low-Carbon Chem. Chem. Eng. 2023, 48, 147–154. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Q.; Wang, Z.; Yuan, M.; Zhao, S.; Chen, H.; Li, L.; Cui, M.; Qiao, X.; Fei, Z. Plasma-induced construction of defect-enriched perovskite oxides for catalytic methane combustion. Environ. Sci. Nano 2021, 8, 2386–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zasada, F.; Janas, J.; Piskorz, W.; Gorczynska, M.; Sojka, Z. Total Oxidation of Lean Methane over Cobalt Spinel Nanocubes Controlled by the Self-Adjusted Redox State of the Catalyst: Experimental and Theoretical Account for Interplay between the Langmuir–Hinshelwood and Mars–Van Krevelen Mechanisms. ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 2853–2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Sun, X.; Tong, X.; Zhang, J.; Li, J.; Li, S.; Liu, Y.; Tsubaki, N.; Abe, T.; Sun, J. Ultra-high thermal stability of sputtering reconstructed Cu-based catalysts. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 7209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y. Study on the Reaction Performance of Pd-Based CH4 Combustion Catalysts in High Concentration CO2 Atmosphere. Master’s Thesis, Taiyuan University of Technology, Taiyuan, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, R.; Wang, W.; Wang, Z.; Wang, H. Advancement of modification engineering in lean methane combustion catalysts based on defect chemistry. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2023, 13, 2556–2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.W. Study on Catalytic Oxidation of Low-Concentration Methane over Ce-Based Catalysts. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Yang, W.H.; Zhang, H.L.; Xu, H.D.; Jiao, Y.; Zhong, L.; Wang, J.L.; Chen, Y.Q. Boosting methane combustion over Pd/Y2O3–ZrO2 catalyst by inert silicate patches tuning both palladium chemistry and support hydrophobicity. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 44887–44898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Wang, F.; Zhu, T.; He, H. Effects of Ce on catalytic combustion of methane over Pd-Pt/Al2O3 catalyst. J. Environ. Sci. 2012, 24, 507–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.S.; Qin, X.N.; Pang, P.; Xiang, J.; Hu, S.; Wang, Y.; Qiu, J.R.; Xu, M.H. Effect of La/Mn modification on Pd/γ-Al2O3 catalyst for methane catalytic combustion. Proc. CSEE 2009, 29, 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.S.; McKeever, P.; Arechavala, M.A.; Wang, Y.C.; Slater, T.J.A.; Haigh, S.J.; Beale, A.M.; Thompsom, J.M. Correlation of the ratio of metallic to oxide species with activity of PdPt catalysts for methane oxidation. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2020, 10, 1408–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, M.A.; Lee, S.B.; Park, N.K.; Kim, K. Pd–Pt bimetallic catalysts for combustion of SOFC stack flue gas. Catal. Today 2012, 185, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strobela, R.; Grunwaldtb, J.D.; Camenzinda, A.; Pratsinisa, S.E.; Baikerb, A. Flame-made alumina supported Pd–Pt nanoparticles: Structural properties and catalytic behavior in methane combustion. Catal. Today 2008, 137, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Qiao, L.-Y.; Zhou, Z.-F.; Cui, G.-J.; Zong, S.-S.; Xu, D.-J.; Ye, R.-P.; Chen, R.-P.; Si, R.; Yao, Y.-G. Revealing the Synergistic Effects of Rh and Substituted La2B2O7 (B = Zr or Ti) for Preserving the Reactivity of Catalyst in Dry Reforming of Methane. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 932–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, M.P.; Mattos, L.V.; Walker, S.; Ayala, M.; Watson, C.D.; Jacobs, G.; Rabelo-Neto, R.C.; Akri, M.; Paul, S.; Noronha, F.B. Unveiling the effect of support on the mechanism of CO2 hydrogenation over supported Ru catalysts. Appl. Catal. B Environ. Energy 2025, 365, 124986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H.; Lee, G.; Kim, B.S.; Bae, J.; Han, J.W.; Lee, H. Fully Dispersed Rh Ensemble Catalyst to Enhance Low-Temperature Activity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 9558–9565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Glarborg, P.; Andersson, M.P.; Johansen, K.; Torp, T.K.; Jensen, A.D.; Christensen, J.M. Influence of the Support on Rhodium Speciation and Catalytic Activity of Rhodium-Based Catalysts for Total Oxidation of Methane. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2020, 10, 6035–6044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Glarborg, P.; Johansen, K.; Andersson, M.P.; Torp, T.K.; Jensen, A.D.; Christensen, J.M. A rhodium-based methane oxidation catalyst with high tolerance to H2O and SO2. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 1821–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, T.; Ding, J.; Tang, X.; Yang, K.; Wang, K.; Huang, B.; Dai, S.; He, Y.; Shi, Y.; Xie, P. Rational design of precious-metal single-atom catalysts for methane combustion. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 43141–43150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neuberg, S.; Pennemann, H.; Shanmugam, V.; Zapf, R.; Kolb, G. Promoting effect of Rh on the activity and stability of Pt-based methane combustion catalyst in microreactors. Catal. Commun. 2021, 149, 106202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

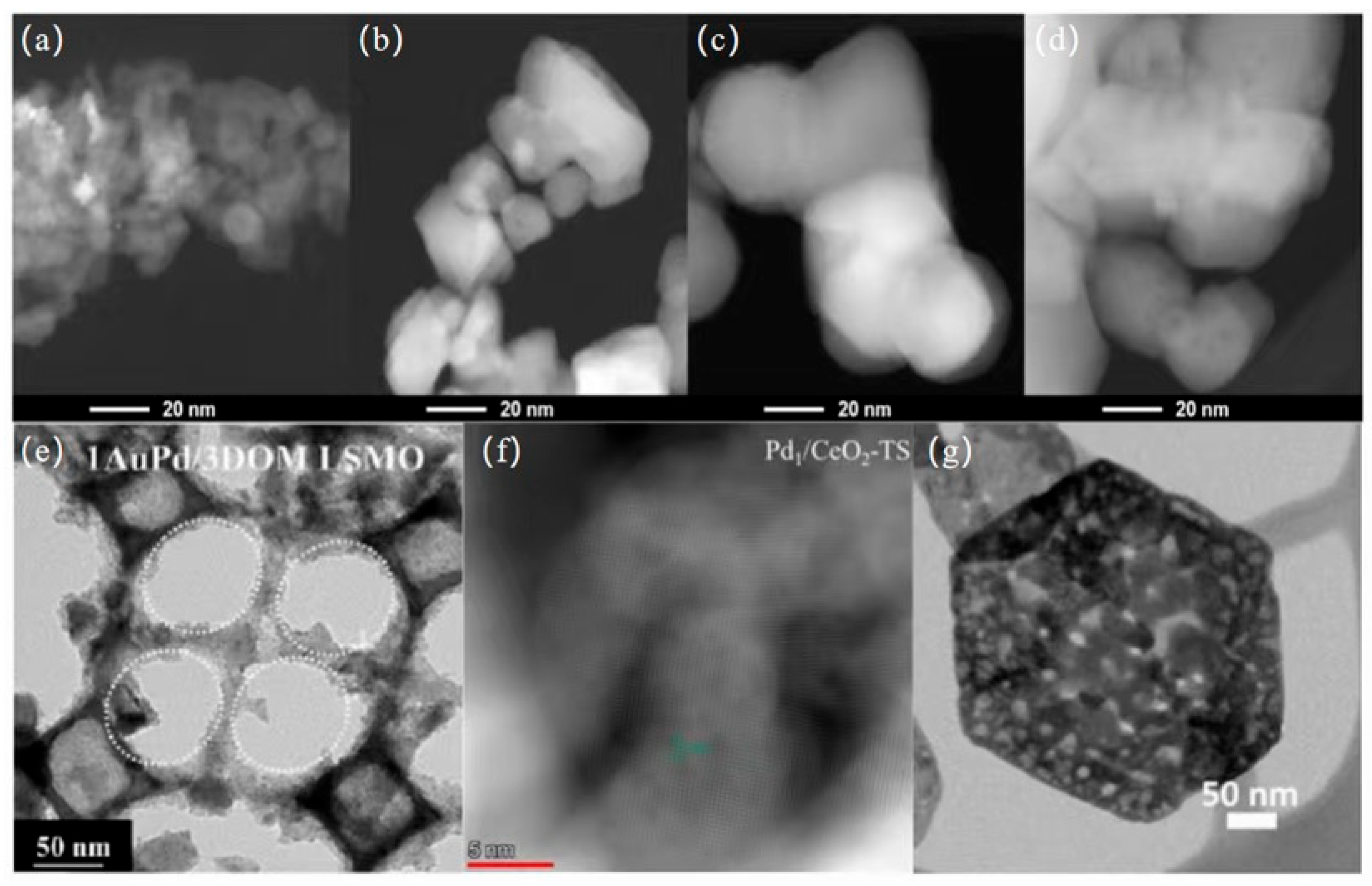

- Wang, Y.; Arandiyan, H.; Scott, J.; Akia, M.; Dai, H.; Deng, J.; Aguey-Zinsuo, K.F.; Amal, R. High performance Au–Pd supported on 3D hybrid strontium-substituted lanthanum manganite perovskite catalyst for methane combustion. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 6935–6947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.; Lott, P.; Tischer, S.; Casapu, M.; Grunwaldt, J.-D.; Deutschmann, O. Methane Oxidation over PdO: Towards a Better Understanding of the Influence of the Support Material. ChemCatChem 2023, 15, e202300366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zhang, X.; Deng, C.; Wang, X.; Guo, X. Boosting methane catalytic combustion by confining PdO-Pd interfaces in zeolite nanosheets. Fuel 2023, 344, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cargnello, M.; Delgado Jaen, J.J.; Hernandez Garrido, J.C.; Bakhmutsky, K.; Montini, T.; Calvino Gamea, J.J.; Gorte, R.J.; Fornasiero, P. Exceptional Activity for Methane Combustion over Modular Pd@CeO2 Subunits on Functionalized Al2O3. Science 2012, 337, 713–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Kong, R.; Wang, Z.; Fang, L.; He, T.; Jiang, D.; Peng, H.; Sun, T.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Y. Enhancing Methane Combustion Activity by Modulating the Local Environment of Pd Single Atoms in Pd1/CeO2 Catalysts. ACS Catal. 2024, 14, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Zhang, R.; Liu, Y.; Deng, J.; Xu, P.; Yang, J.; Han, Z.; Huo, Z.; Dai, H.; Au, C.-T. In-situ reduction-derived Pd/3DOM La0.6Sr0.4MnO3: Good catalytic stability in methane combustion. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2018, 568, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Guo, Y. Nanostructured perovskite oxides as promising substitutes of noble metals catalysts for catalytic combustion of methane. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2018, 29, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashan, V.; Ust, Y. Perovskite catalysts for methane combustion: Applications, design, effects for reactivity and partial oxidation. Int. J. Energy Res. 2019, 43, 7755–7789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharczyk, B.; Tylus, W. Metallic monolith supported LaMnO3 perovskite-based catalysts in methane combustion. Catal. Lett. 2007, 115, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Lan, J.; Guo, Y.; Cao, X.-M.; Hu, P. Origin of Efficient Catalytic Combustion of Methane over Co3O4(110): Active Low-Coordination Lattice Oxygen and Cooperation of Multiple Active Sites. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 5508–5519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyjoo, Y.; Jin, Y.; Mao, X.; Zhao, G.; Gengenbach, T.; Du, A.; Guo, H.; Liu, J. Crystal Facet Engineering of Spinel NiCo2O4 with Enhanced Activity and Water Resistance for Tuneable Catalytic Methane Oxidation. EES Catal. 2024, 2, 638–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.F.; Shan, J.J.; Nguyen, L.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, L.; Wu, Z.; Huang, W.; Zeng, S.; Hu, P. Understanding complete oxidation of methane on spinel oxides at a molecular level. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losch, P.; Huang, W.; Vozniuk, O.; Goodman, E.D.; Schmidt, W.; Cargnello, M. Modular Pd/zeolite composites demonstrating the key role of support hydrophobic/hydrophilic character in methane catalytic combustion. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 4742–4753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Gong, Z.; Weng, X.; Shang, W.; Chai, Y.; Dai, W.; Wu, G.; Guan, N.; Li, L. Methane combustion over palladium catalyst within the confined space of MFI zeolite. Chin. J. Catal. 2021, 42, 1689–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.B.; Jo, D.; Hong, S.B. Palladium-exchanged small-pore zeolites with different cage systems as methane combustion catalysts. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2017, 219, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhou, W.; Li, W.; Xiong, X.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, K.; Kang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y. In-situ confinement of ultrasmall palladium nanoparticles in silicalite-1 for methane combustion with excellent activity and hydrothermal stability. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2020, 276, 119142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friberg, N.O.L. The effect of Si/Al ratio of zeolite supported Pd for complete CH4 oxidation in the presence of water vapor and SO2. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2019, 250, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortensen, R.L.; Noack, H.D.; Pedersen, K.; Mossin, S.; Mielby, J. The effect of zeolite counter ion on a Pd/H-CHA methane oxidation catalyst with remarkable tolerance towards SO2. Top. Catal. 2025, 68, 2408–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.; McGuire, J.; Lawnick, O.; Bozack, M. Low-temperature activity and PdO-PdOx transition in methane combustion by a PdO-PdOx/γ-Al2O3 catalyst. Catalysts 2018, 8, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, E.D.; Ye, A.A.; Aitbekova, A.; Mueller, O.; Riscoe, A.R.; Taylor, T.N.; Hoffman, A.S.; Boubnov, A.; Bustillo, K.C.; Nachtegaal, M.; et al. Palladium oxidation leads to methane combustion activity: Effects of particle size and alloying with platinum. J. Chem. Phys. 2019, 151, 154703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Polo-Garzon, F.; Zhou, H.; Chi, M.; Meyer, H.; Yu, X.; Li, Y.; Wu, Z. Boosting the activity of Pd single atoms by tuning their local environment on ceria for methane combustion. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202217323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, R.K.; Chong, M.Y.; Osazuwa, O.U.; Nam, W.L.; Phang, X.Y.; Su, M.H.; Cheng, C.K.; Chong, C.T.; Lam, S.S. Production of activated carbon as catalyst support by microwave pyrolysis of palm kernel shell: A comparative study of chemical versus physical activation. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2018, 44, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.B.; Deng, C.B.; Deng, H.Z.; Wang, X. Combustion performance of ventilation air methane over defect perovskite LaMnO3 catalyst. J. China Coal Soc. 2022, 47, 1588–1595. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Xu, X.L.; Zhu, J.J.; Tang, D.H.; Zhao, Z. Effect of preparation method on physicochemical properties and catalytic performances of LaCoO3 perovskite for CO oxidation. J. Rare Earths 2019, 37, 970–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safdar, M.; Shezad, N.; Akhtar, F.; Arellano-Garcia, H. Development of Ni-doped A-site lanthanides-based perovskite-type oxide catalysts for CO2 methanation by auto-combustion method. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 20240–20253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, M.; Zhao, C.C.; Wang, Y.Q.; Chen, S.Q. A review of recent advances in catalytic combustion of VOCs on perovskite-type catalysts. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2019, 23, 645–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, F.F.; Mao, D.S.; Guo, X.M.; Yu, M.; Huang, H.J. Research progress on catalysts for catalytic combustion of methane. J. Technol. 2019, 19, 242–248. [Google Scholar]

- Pu, Z.Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, H.; Zheng, Y.; Li, X. Catalytic combustion of lean methane at low temperature over ZrO2-modified Co3O4 catalysts. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 422, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.Y.; Ma, K.D.; Wang, J.; Pan, L.W. Research progress on non-noble metal catalysts for catalytic combustion of methane. China Biogas 2019, 37, 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Mihai, M.A.; Culita, D.C.; Atkinson, I.; Papa, F.; Popescu, L.; Marcu, L.-C. Unraveling mechanistic aspects of the total oxidation of methane over Mn, Ni and Cu spinel cobaltites via in situ electrical conductivity measurements. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2021, 611, 117901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Luo, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, G.; Xiang, H.; Yan, Y.; Ke, X.; Lu, Y.; Yao, C.; et al. Strong oxide-support interaction induced thermal stabilization of Pt single atoms for durable catalytic CO oxidation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202504551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, B.; Yang, M.; Dai, H.; Ke, Z.; He, D.; Feng, X.; et al. Unraveling the modulation essence of p bands in Co-based oxide stability on acidic oxygen evolution reaction. Nano Res. 2024, 17, 5922–5929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.Y.; Du, S.L.; Wang, X.F. Research progress on non-noble metal oxide catalysts for catalytic combustion of methane. Nat. Gas Chem. Ind. (C1 Chem. Chem. Eng.) 2021, 46, 10–14. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, X.B.; Qu, Z.G. Methane combustion with cobalt-substituted barium-lanthanum hexaaluminate catalysts supported on porous monolithic honeycombs. J. Energy Eng. 2018, 144, 04018015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, G.; Zhou, Y. A detailed numerical analysis of NOx formation and destruction during MILD combustion of CH4/H2 blends using a skeletal mechanism. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 103, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, J.G.; Yang, Z.Q.; Tang, Q. Combustion characteristics of ultra-low concentration methane in a fluidized bed with Cu/γ-Al2O3 catalytic particles. J. Fuel Chem. Technol. 2012, 40, 886–891. [Google Scholar]

- Farrauto, R.J. Low-Temperature Oxidation of Methane. Science 2012, 337, 659–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, J.J.; Goodman, E.D.; Wu, L.H.; Riscoe, A.R.; Martins, P.; Tassone, C.J.; Cargnello, M. Systematic Identification of Promoters for Methane Oxidation Catalysts Using Size- and Composition-Controlled Pd-Based Bimetallic Nanocrystals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 11989–11997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Chen, C.; Cargnello, M.; Fornasiero, P.; Gorte, R.J.; Graham, G.W.; Pan, X.Q. Dynamic structural evolution of supported palladium–ceria core–shell catalysts revealed by in situ electron microscopy. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Cho, J.H.; Kim, Y.J.; Kim, E.S.; Han, H.S.; Shin, C.-H. Hydrothermal stability of Pd/ZrO2 catalysts for high temperature methane combustion. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2014, 160–161, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benbellil, M.A.; Lounici, M.S.; Loubar, K.; Tazerout, M. Investigation of natural gas enrichment with high hydrogen participation in dual fuel diesel engine. Energy 2022, 243, 123056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Li, R.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Q.; Cao, M.; Liu, F. Chemical kinetics properties and the influences of different hydrogen blending ratios on reactions of natural gas. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2023, 41, 102641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Bai, H.; Fan, J.; Yu, J.; Bi, D.; Zhu, Z.; Gao, P. Research status and development of low-nitrogen burner for low calorific value gas fuel. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 252, 042048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Li, J.; Wei, J.; Li, C. Application of catalytic oxidation technology adopting the reverse flow reactor. J. Beijing Univ. Chem. Technol. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2018, 45, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Zhu, J.; Li, P.; Wei, J.; Li, C. Investigation of catalytic combustion of low concentration methane in reverse flow reactor. J. Fuel Chem. Technol. 2005, 33, 723–728. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, H.S.F.; Mmbaga, J.P.; Hayes, R.E. Catalyst optimization in a catalytic flow reversal reactor for lean methane combustion. Catal. Today 2023, 407, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.F.; Gou, X.L. Experimental Research on the Thermal Oxidation of Ventilation Air Methane in a Thermal Reverse Flow Reactor. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 14886–14894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haynes, T.N.; Georgakis, C.; Caram, H.S. The Design of Reverse Flow Reactors for Catalytic Combustion Systems. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1995, 50, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matros, Y.S.; Bunimovich, G.A. Reverse-Flow Operation in Fixed Bed Catalytic Reactors. Catal. Rev. 1996, 38, 1–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matros, Y.S.; Bunimovich, G.A.; Noskov, A.S. The decontamination of gases by unsteady-state catalytic method: Theory and practice. Catal. Today 1993, 17, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlaczyk-Kurek, A.; Suwak, M. Will It Be Possible to Put into Practice the Mitigation of Ventilation Air Methane Emissions? Review on the State-of-the-Art and Emerging Materials and Technologies. Catalysts 2021, 11, 1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosiewski, K.; Pawlaczyk, A. Catalytic or thermal reversed flow combustion of coal mine ventilation air methane: What is better choice and when? Chem. Eng. J. 2014, 238, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Liu, L.; Shen, W.; Lyu, Y.; Qui, P. Experimental and computational study of combustion characteristic of dual-stage lean premixed flame. Energy Fuels 2019, 33, 2394–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahsavari, M.; Farshchi, M.; Arabnejad, M.H.; Wang, B. The role of flame–flow interactions on lean premixed lifted flame stabilization in a low swirl flow. Combust. Sci. Technol. 2023, 195, 897–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, N.; Zhao, D.Q.; Wang, X.H.; Yang, H.L.; Zhang, L.Z.; Yang, W.B. Numerical research of premixed combustion of diluted methane in a tubular flame burner. In Proceedings of the 2013 International Conference on Materials for Renewable Energy and Environment, Chengdu, China, 19–21 August 2013; pp. 770–773. [Google Scholar]

- Verma, H.K.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, K.; Mohammed, R. Flashback and lean blow out study of a lean premixed pre-vaporized can combustor. In Proceedings of the ASME GTIndia, Bangalore, India, 7–8 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.H. Improved chemical reactor network application for predicting the emission of nitrogen oxides in a lean premixed gas turbine combustor. Combust. Explos. Shock Waves 2019, 55, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Shuai, L.; Chen, B.; Wang, N. Catalytic Combustion of Low-Concentration Methane: From Mechanistic Insights to Industrial Applications. Catalysts 2026, 16, 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010056

Shuai L, Chen B, Wang N. Catalytic Combustion of Low-Concentration Methane: From Mechanistic Insights to Industrial Applications. Catalysts. 2026; 16(1):56. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010056

Chicago/Turabian StyleShuai, Liang, Biaohua Chen, and Ning Wang. 2026. "Catalytic Combustion of Low-Concentration Methane: From Mechanistic Insights to Industrial Applications" Catalysts 16, no. 1: 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010056

APA StyleShuai, L., Chen, B., & Wang, N. (2026). Catalytic Combustion of Low-Concentration Methane: From Mechanistic Insights to Industrial Applications. Catalysts, 16(1), 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010056