LDH-Derived Preparation of Ce-Modified MnCoAl Layered Double Oxides for NH3-SCR: Performance and Reaction Process Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

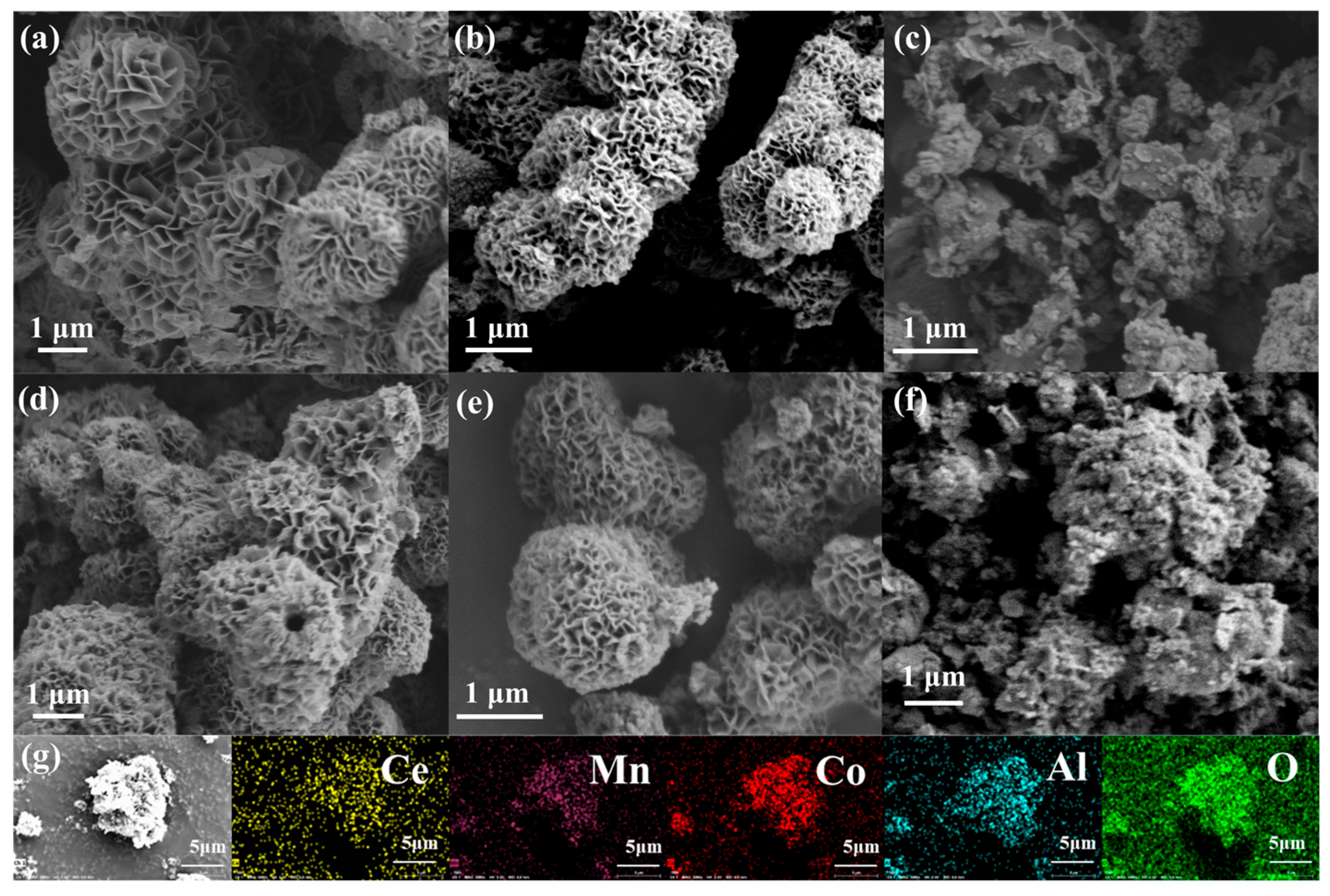

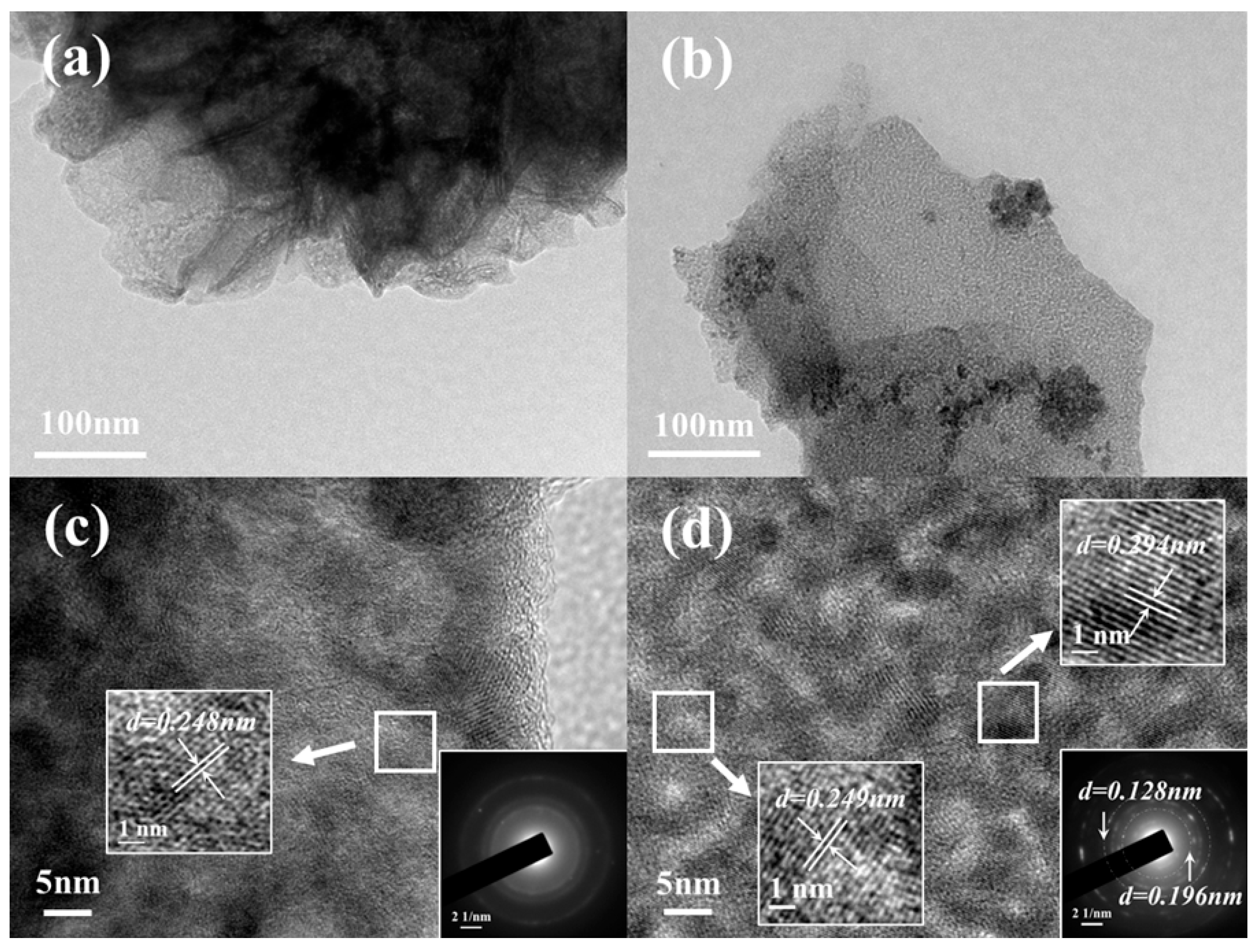

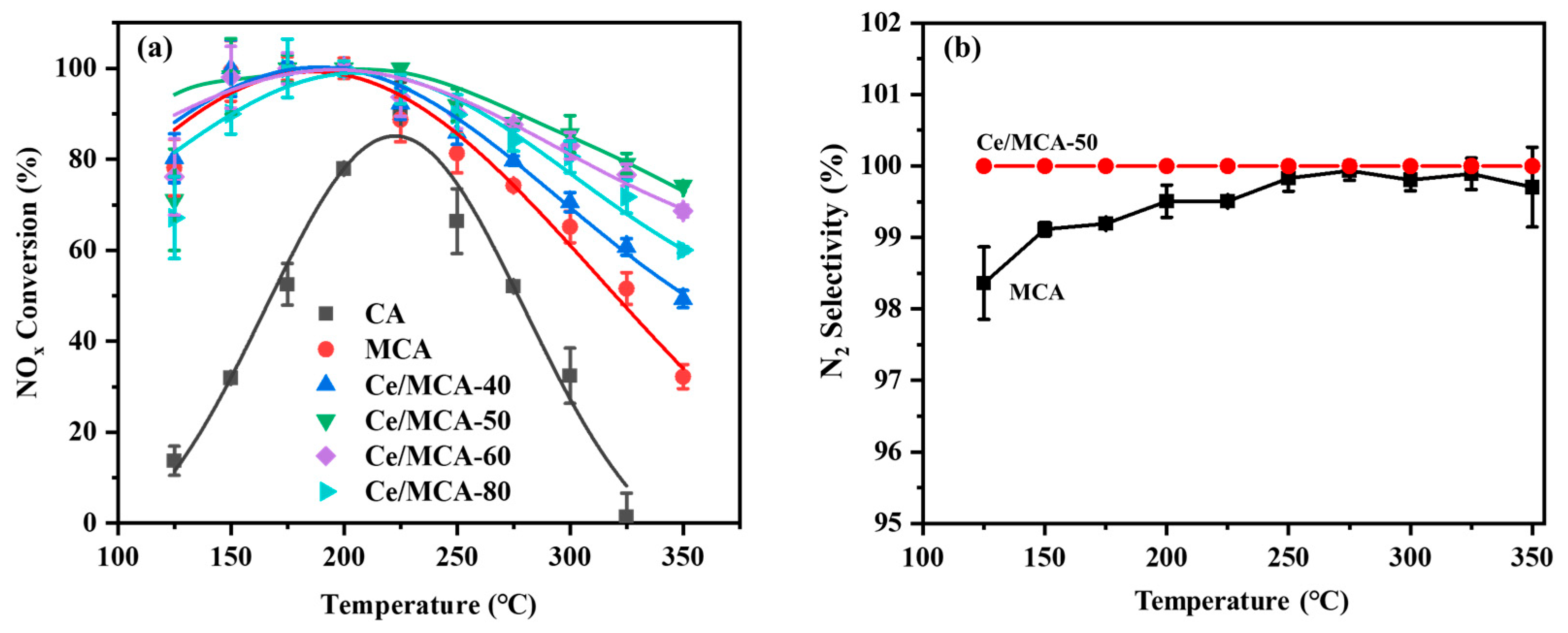

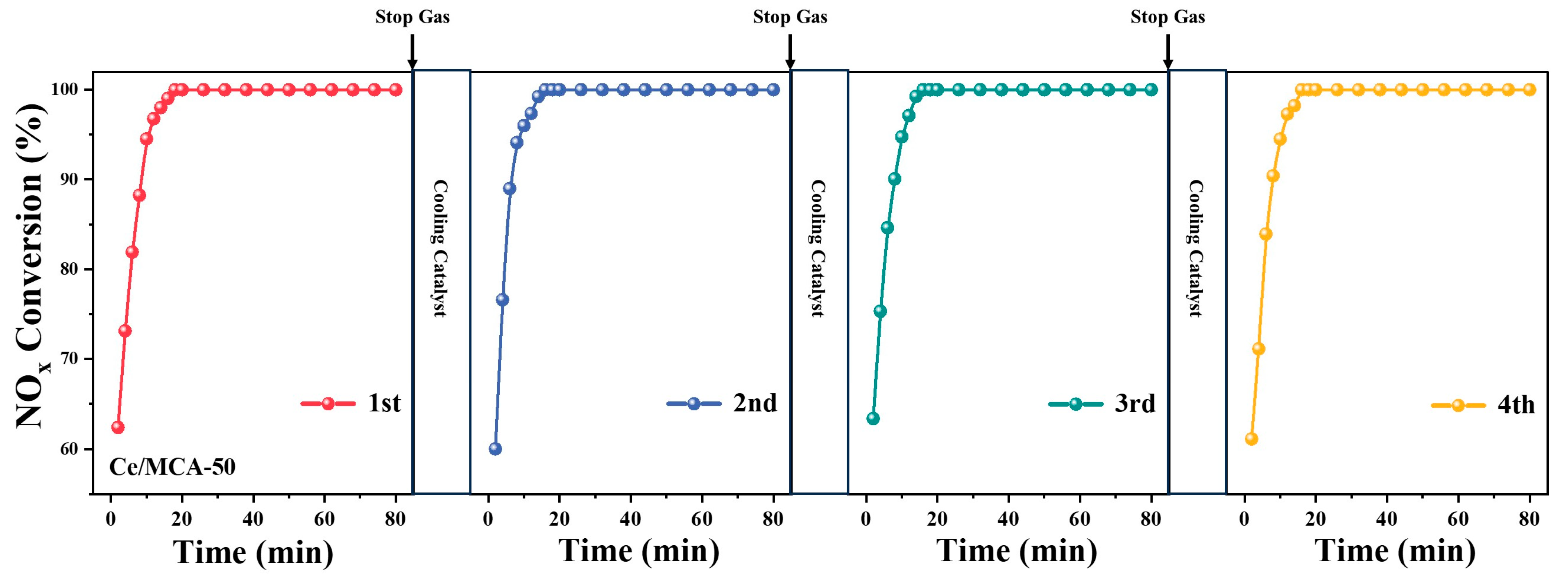

2. Results and Discussion

- (1)

- Reaction of pre-adsorbed NH3 with NO + O2

- (2)

- Reaction of NH3 with pre-adsorbed NO + O2

- (3)

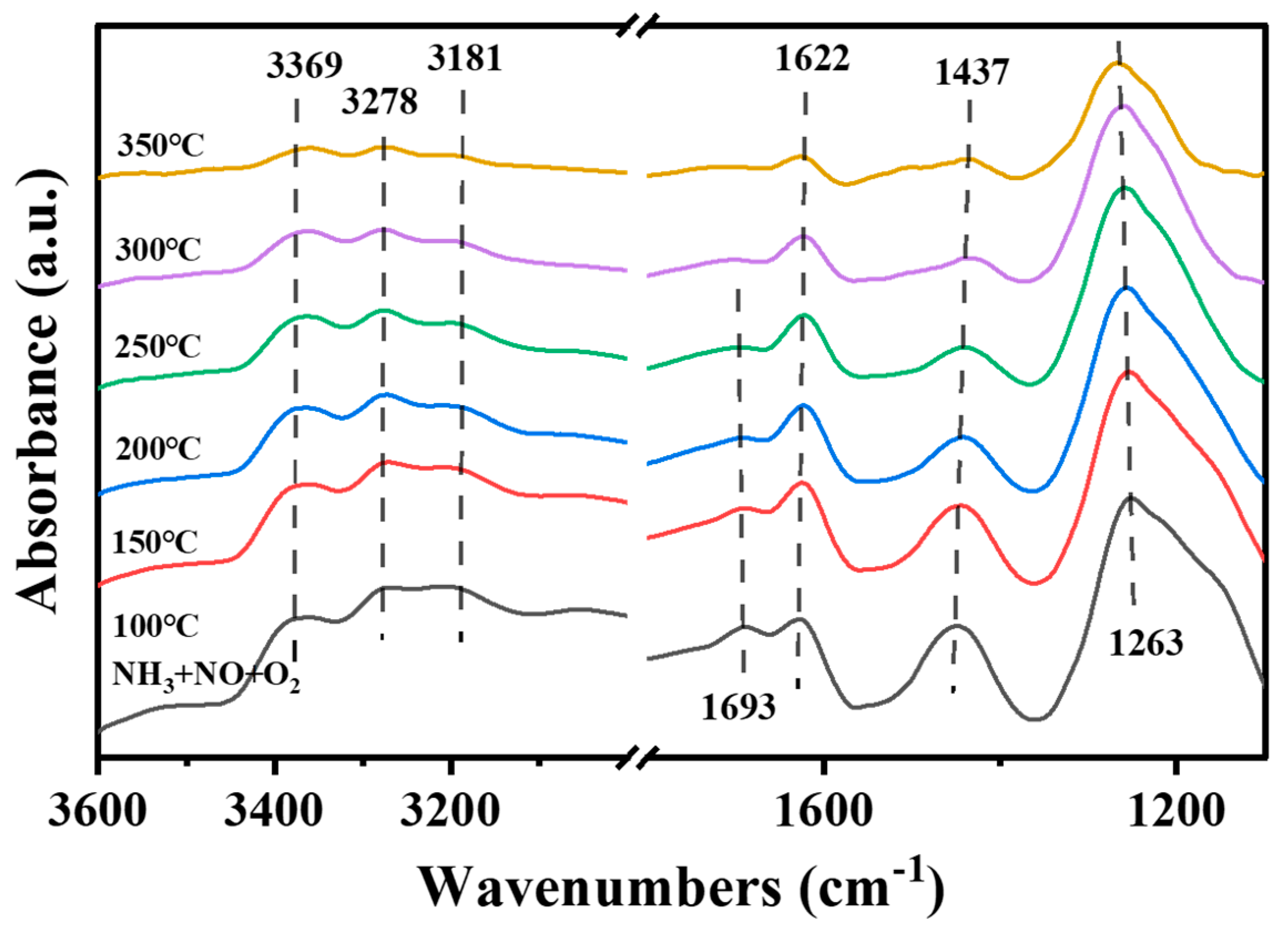

- Reaction of NH3 and NO + O2 at different temperatures

3. Experimental Procedure

3.1. Synthesis

3.2. Characterization

- i.

- NO + O2 react with pre-adsorbed NH3

- ii.

- NH3 reaction with pre-adsorbed NO + O2

- iii.

- The reaction of NH3 and NOx + O2 at different temperatures

3.3. NH3-SCR Performance and the Resistance of SO2/H2O

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jafarsalehi, M.; Mashayekh, M.; Bagher Miranzadeh, M.; Mirzaei, N.; Ebrahimi, M. Primary measures for cleaner biomass combustion to reduce NOx: A narrative review on solid biomass fuels, NOx sources, small-scale boilers, axillary equipment, fuel management and fuel quality improvement. Fuel 2025, 396, 134891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, G.; Liu, B.; Wang, R.; Wang, H.; Miao, Y.; Hou, S.; Lian, D.; Chen, M.; Li, C.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Pretreatment techniques in CO-SCR and NH3-SCR: Status, challenges, and perspectives. J. Catal. 2025, 442, 115925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Peng, Q.; Xie, B.; Wei, J.; Yin, R.; Fu, G. Mechanism, performance and modification methods for NH3-SCR catalysts: A review. Fuel 2023, 331, 125885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, P.; Mansoor, M.; Zhang, J.; Peng, D.; Han, L.; Zhang, D. Challenges and perspectives of environmental catalysis for NOx reduction. JACS Au 2024, 4, 2767–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altalhi, A.A.; Mohamed, E.A.; Negm, N.A. Recent advances in layered double hydroxides (LDH)-based materials: Fabrications, modification strategies, characterization, promising environmental catalytic applications, and prospective aspects. Energy Adv. 2024, 3, 2136–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, U.A.; Sahoo, D.P.; Paramanik, L.; Parida, K. A critical review on layered double hydroxide (LDH)-derived functional nanomaterials as potential and sustainable photocatalysts. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2023, 7, 1145–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.L.; Li, M.H.; Zhao, L.X.; Yan, Z.X.; Xie, M.; Lin, J.M.; Zhao, R.S. A novel oxygen vacancy enriched CoNi LDO catalyst activated peroxymonosulfate for the efficient degradation of tetracycline. J. Water Process Eng. 2023, 52, 103526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, L.; Song, X.; Huo, P.; Liu, X. A Short Review of Layered Double Oxide-Based Catalysts for NH3-SCR: Synthesis and NOx Removal. Catalysts 2024, 14, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Monaem, E.M.; Elshishini, H.M.; Bakr, S.S.; EI-Aqapa, H.G.; Hosny, M.; Andaluri, G.; EI-Subruiti, G.M.; Omer, A.M.; Eltaweil, A.S. A comprehensive review on LDH-based catalysts to activate persulfates for the degradation of organic pollutants. Npj Clean Water 2023, 6, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xing, Y.; Zhang, H.; Su, W.; Tian, J.; Zhang, W.; Jia, H.; Wang, T.; Ma, M. In-situ DRIFTs study for synergistic removal of NOx and o-DCB over hydrotalcite-like structured Cr (x)/LDO catalysts. New J. Chem. 2023, 47, 13260–13268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Fan, Z.; Liu, J.; Liu, X.; Yang, M.; An, X.; Wu, X. Collaborative optimization of de-NOx & NH4HSO4 decomposition over Cu-based LDO catalysts: Perspective from the acidic and redox properties. Surf. Interfaces 2024, 48, 104377. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Q.; Zhao, M.; Fan, H.; Zhu, R.; Zhong, R.; Bai, X. Low-Temperature NH3-SCR Technology for Industrial Application of Waste Incineration: An Overview of Research Progress. Catalysts 2024, 14, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.; Xiao, J.; Gui, R.; Chen, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhu, T.; Wang, Q.; Xin, Y. Mechanistic Insight into the Promotion of the Low-Temperature NH3-SCR Activity over NiMnFeOx LDO Catalysts: A Combined Experimental and DFT Study. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 20708–20717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luan, X.; Zhai, Y.; Guo, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhang, J.; Wang, L.; Wang, Z. Unraveling Excellent Performance in NH3-SCR over Cr-Doped NiMn-LDO Catalysts: A Combined Experimental and Computational Study. Nano Lett. 2025, 25, 8450–8457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chen, W.; Jin, W.; Liu, Y. Mn mixed oxide catalysts supported on Sn-doped CoAl-LDO for low-temperature NH3-SCR. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2023, 13, 3147–3157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Zhu, J.; Song, K.; Zeng, J.; Zhou, X.; Guo, X.; Lin, K.; Zhang, C.; Xie, C.; Shi, J. Insight into the reasons for enhanced NH3-SCR activity and SO2 tolerance of Mn-Co layered oxides. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 336, 126285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Shen, B.; Gao, J.; Ji, Y.; Wu, M.; Wang, F. Constructing multi-active sites of LDH-derived MnCoFe layered mixed oxide catalysts for simultaneous removal of NO and toluene. Appl. Catal. B Environ. Energy 2025, 377, 125496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Luo, N.; Huang, Z.; Zhao, G.; Chu, F.; Yang, R.; Tang, X.; Wang, G.; Gao, F.; Huang, X. Recent advances in low-temperature NH3-SCR of NOx over Ce-based catalysts: Performance optimizations, reaction mechanisms and anti-poisoning countermeasures. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 476, 146889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Jia, Z.; Lan, Y.; Xu, S.; Chen, G.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, C. The Performance and Deactivation of Selective Catalytic Reduction of NOx with NH3 Over Cerium-based Catalysts: A Review. Top. Catal. 2025, 68, 2030–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Lee, K.T.; Lee, K.B. Novel layered double hydroxide-based passive NOx adsorber: Synergistic effects of Co and Mn on low-temperature NOx storage and regeneration. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 324, 124391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanagalakshmi, M.; Kumar, T.R.N.; Janani, R.; Pius, A. Photocatalytic hydrogel impregnated CoMgAl layered double oxide and biochar for visible light driven degradation of agrochemical contaminants in real water matrices. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 523, 168519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Wang, X.; Li, H.; Xing, L.; Liu, M. The Resistance of SO2 and H2O of Mn-Based Catalysts for NOx Selective Catalytic Reduction with Ammonia: Recent Advances and Perspectives. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 7262–7278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Sun, X.; Zhang, G.; Cheng, S.; Xu, Y.; Jiang, Y. Recent advances in improving SO2 resistance of Ce-based catalysts for NH3-SCR: Mechanisms and strategies. Mol. Catal. 2024, 564, 114347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, K.; Bian, M.; Yuan, Z.; Li, Y.; Rao, C.; Yang, X.; Zhang, Y. Photothermal-Enhanced Anti-SO2 Performance of a MoWOx/CeO2 Catalyst in Low-Temperature NH3-SCR. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 12364–12377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Z.; Zhao, H.; Wang, H.; Xu, J.; Fu, Z.; Yu, G.; Wu, H. Synthesis of low-temperature NH3-SCR catalysts for MnOx with high SO2 resistance using redox-precipitation method with mixed manganese sources. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2025, 680, 161465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Niu, Y.; Cui, Y.; Liu, Y.; Luo, N.; Wen, J.; Duan, E.; Wang, C.; Yi, H.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Excellent performance of Ce doped CoMn2O4/TiO2 catalyst in NH3-SCR of NO under H2O&SO2 conditions. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 113849. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, M.; Wang, C.; Jing, W.; Fang, L.; Hu, Y.; Liang, Y.; Wang, X. Synergistic Effect of Iron Doping and Oxide Hybridization Enables Enhanced Low-Temperature NH3-SCR Performance of Manganese Oxide Catalyst. Catal. Lett. 2025, 155, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhang, T.; Ma, G.; Zhang, J.; Li, S.; Song, W.; Liu, J. Revealing the nature of dinuclear active sites on CenTiOx catalysts for the selective catalytic reduction NOx with NH3. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 109685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Leng, X.; Zhang, Z.; Niu, X.; Zhu, Y. Modulating NH3 oxidation and inhibiting sulfate deposition to improve NH3-SCR denitration performance by controlling Mn/Nb ratio over MnaNbTi2Ox (a = 0.6–0.9) catalysts. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 482, 136568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Ren, S.; Jiang, Y.; Su, B.; Chen, Z.; Liu, W.; Yang, J.; Chen, L. Insights into co-doping effect of Sm and Fe on anti-Pb poisoning of Mn-Ce/AC catalyst for low-temperature SCR of NO with NH3. Fuel 2022, 319, 123763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Bian, X.; Xie, F.; Bai, Y.; Wang, J. Research progress in the composition and performance of Mn-based low-temperature selective catalytic reduction catalysts. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Guo, N.; Peng, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Ren, D.; Gui, K. Excellent operating temperature window and H2O/SO2 resistances of Fe-Ce catalyst modified by different sulfation strategies for NH3-SCR reaction. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 50635–50648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojo, H.; Hirota, K.; Ito, S.; Einaga, H. Reduction Mechanism for CeO2 Revealed by Direct Observation of the Oxygen Vacancy Distribution in Shape-Controlled CeO2. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 10, 2201954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.Y.; Jang, W.J.; Shim, J.O.; Jeon, B.H.; Roh, H.S. CeO2-based oxygen storage capacity materials in environmental and energy catalysis for carbon neutrality: Extended application and key catalytic properties. Catal. Rev. 2024, 66, 1316–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuo, F. Experimental study of Fe modified Mn/CeO2 catalyst for simultaneous removal of NO and toluene at low temperature. J. Fuel Chem. Technol. 2023, 51, 1866–1878. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, L.; Sun, X.; Li, J.; Lu, L.; Wang, T.; Wu, W. Denitrification performance and mechanism of NH3-SCR rare earth tailings catalyst modified by Ce combined with Mn. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2025, 51, 721–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Liang, B.; Ren, H.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X.; Zheng, W.; Liu, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, X. An investigation on reaction principles of Mn-Fe-CeOx catalyst system: Guide the synthesis of low-temperature NH3-SCR catalytic filter. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2025, 37, 103926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Li, Z.; Cui, J.; Ma, Y.; Yang, C. Modulating the low-temperature NH3-SCR activity of bimetallic MOF-derived MnCeOx/C catalyst via the molar ratio of manganese and cerium. Adv. Powder Technol. 2025, 36, 105102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Tian, Z.; Huang, W.; Hu, J.; Xing, X. Investigation of long-term anti-sulfur and deactivation mechanism of monolithic Mn-Fe-Ce/Al2O3 catalysts for NH3-SCR: Changes in physicochemical and adsorption properties. Surf. Interfaces 2024, 48, 104295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, S.; Tang, X.; Yi, H.; Gao, F.; Wang, C.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, R.; Zhu, W. Novel Mn–Ce bi-oxides loaded on 3D monolithic nickel foam for low-temperature NH3-SCR de-NOx: Preparation optimization and reaction mechanism. J. Rare Earths 2022, 40, 268–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.Y.; Li, W.J.; Wey, M.Y. Strategies for designing hydrophobic MnCe-montmorillonite catalysts against water vapor for low-temperature NH3-SCR. Fuel 2023, 350, 128857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nellessen, A.; Villamaina, R.; Schaefer, A.; Raj, A.; Newman, A.; Martinelli, A.; Carlsson, P.A. Antimony modification of VOx/TiO2 NH3-SCR catalysts and the effect of thermal aging. J. Catal. 2025, 450, 116303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youn, J.R.; Mnoyan, A.; Kim, M.J.; Ku, B.J.; Lee, S.J.; Kim, M.; Hwang, S.M.; Jeong, S.K.; Lee, K.; Jeon, S.G. Impact of carbon coating on V/TiO2 catalysts for low-temperature NH3-SCR: Improving efficiency and SO2 resistance. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2025, 152, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Hua, M.; Gu, M.; Jia, Y.; Guo, L.; Long, H.; Yu, J.; Zhang, S. Complex nitrogen modified promotion on vanadium phosphorus oxide catalysts with amorphous phases for low-temperature NH3-SCR of NOx. J. Environ. Sci. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Xu, S.; Wang, H.; Nie, R.; Wen, J.; Zhao, M.; Cao, J.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Q.; Ning, P. Unveiling the mechanistic insights into the potassium resistance of 3.5 WV-1% K NH3-SCR catalysts: The dual functionality of VOW structure as acid and redox sites. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 354, 129192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, H.; Lai, J.; Yuan, Q.; Ma, Y.; Qian, Y.; Han, Z.; Lin, X.; Li, X. Unraveling the role of phosphorus on V2O5-WO3-CeO2/TiO2 catalysts: Mechanisms for enhanced NH3-SCR and water resistance. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 520, 165979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Samples | BET Surface Area (m2/g) | Pore Volume (cm3/g) | Pore Diameter (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CA | 163.89 | 0.33 | 8.08 |

| MCA | 121.58 | 0.33 | 10.83 |

| Ce/MCA-40 | 126.05 | 0.37 | 11.74 |

| Ce/MCA-50 | 121.69 | 0.33 | 10.79 |

| Ce/MCA-60 | 95.14 | 0.24 | 10.19 |

| Ce/MCA-80 | 76.50 | 0.16 | 8.31 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; Sun, T.; Einaga, H.; Hojo, H.; Huo, P. LDH-Derived Preparation of Ce-Modified MnCoAl Layered Double Oxides for NH3-SCR: Performance and Reaction Process Study. Catalysts 2026, 16, 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010055

Liu X, Zhang J, Sun T, Einaga H, Hojo H, Huo P. LDH-Derived Preparation of Ce-Modified MnCoAl Layered Double Oxides for NH3-SCR: Performance and Reaction Process Study. Catalysts. 2026; 16(1):55. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010055

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Xin, Jinshan Zhang, Tao Sun, Hisahiro Einaga, Hajime Hojo, and Pengwei Huo. 2026. "LDH-Derived Preparation of Ce-Modified MnCoAl Layered Double Oxides for NH3-SCR: Performance and Reaction Process Study" Catalysts 16, no. 1: 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010055

APA StyleLiu, X., Zhang, J., Sun, T., Einaga, H., Hojo, H., & Huo, P. (2026). LDH-Derived Preparation of Ce-Modified MnCoAl Layered Double Oxides for NH3-SCR: Performance and Reaction Process Study. Catalysts, 16(1), 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010055