1. Introduction

Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) are one of the primary sources of air pollution. They are mainly produced by petroleum refineries, fuel combustion, chemical industries, biomass decomposition, pharmaceutical plants, automotive industries, textile manufacturers, cleaning products, printing presses, etc. [

1,

2]. Various technologies can be used to eliminate these harmful compounds, such as adsorption [

3], condensation [

4], membrane separation [

5], biological degradation [

6], non-thermal plasma oxidation [

7], photocatalytic breakdown [

8], and catalytic oxidation [

9]. Catalytic oxidation technology is widely used among these techniques because of its high efficiency rates and low reaction temperatures [

10]. Supported noble metals, supported transition metals, and non-supported transition metal oxides are the three main catalyst types used in this technology [

9,

11,

12].

Due to its unique structure and characteristics, the perovskite-type catalysts (ABO

3) are among the most promising non-noble metal catalysts for the catalytic combustion of volatile organic compounds. Typically, B represents the transition metal ions, and A represents the rare earth or alkaline earth ions [

13]. The source of the catalytic activity of perovskite-type oxide compounds is still up for debate; however, numerous investigations have indicated that oxygen vacancies in these compounds are important in catalytic oxidation reactions [

14,

15]. Oxygen vacancies, created by a variation in the A or B cations’ oxidation states, are favorable locations for oxygen adsorption in perovskite materials [

16]. In the catalytic combustion of volatile organic compounds, a crucial circumstance for perovskite catalyst efficacy is its oxygen mobility [

15]. Oxygen mobility in the perovskite lattice is influenced by the type of cation at position A and rises in direct proportion to the oxygen vacancy concentration [

16,

17]. These materials can be considered efficient catalysts, offering a low-cost and affordable alternative to supported noble metals, while also exhibiting enhanced thermal stability at elevated temperatures [

18]. Beginning around 1970 [

13], perovskite catalysts with lanthanum as the A-site ion were used to convert or reduce aldehydes and ketones, and other gaseous organic substances. Since then, researchers have thoroughly examined their catalytic activity and effectivity in removing VOCs [

19,

20,

21]. Because of their relatively high surface area, higher concentration of oxygen adspecies (formed by gas-phase oxygen molecules and influenced by oxygen nonstoichiometry), and relatively low-temperature reducibility, Liu et al. reported that uniform, hollow, spherical LaCoO

3 demonstrated high catalytic activity in toluene oxidation [

22].

Perovskite-type mixed oxides attract considerable attention due to their potential use as catalysts in high-temperature reactions, as cathode materials in solid oxide fuel cells, and as oxygen-conducting membranes. Among these, one of the most promising groups of oxidation catalysts is based on La

1−xSr

xMO

3±δ (M = Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Cu). Their attractiveness arises from the adaptable electronic characteristics of transition metals in octahedral coordination, the high oxygen and electronic mobility, and their excellent structural as well as thermal stability [

23].

In the pursuit of materials with adjustable and improved oxygen-ion transport within the crystal lattice, layered perovskite-related structures emerge as particularly significant, with the Ruddlesden–Popper (RP) phases standing out among them [

24]. RP phases are generally expressed by the formula A

n+1B

nO

3n+1, where A corresponds to an alkali, alkaline-earth, or rare earth element, and B is a metal cation in octahedral coordination. Their structure consists of perovskite-like blocks separated by rock-salt (NaCl-type) layers. The parameter

n defines the thickness of the perovskite slab and reflects the number of BO

6 octahedra aligned along the c-axis. Within this framework, the ideal perovskite ABO

3 represents the limiting case at

n = ∞, while A

2BO

4 (

n = 1) is equivalent to the K

2NiF

4-type structure. Similar to standard perovskites, the Goldschmidt tolerance factor serves as a useful criterion for evaluating the symmetry and stability of the crystal lattice in A

2BO

4-type (RP,

n = 1) compounds [

25]. A wide variety of compounds containing different A and B cations are known to adopt the K

2NiF

4-type structure when the tolerance factor lies within the interval 0.8 ≤ t ≤ 1. Moreover, the appearance of an ideal K

2NiF

4 framework with tetragonal I4/mmm symmetry is generally linked to a critical tolerance factor of t = 0.9068. When the value of

t falls below this limit, the crystal lattice usually undergoes an orthorhombic distortion. The layered arrangement of these materials permits substantial variation in oxygen content (non-stoichiometry) through the appropriate substitution in the A-cation position, which in turn enhances the mobility of oxygen ions throughout the crystal lattice [

26,

27]. Among these, lanthanum–strontium ferrite (La

2−xSr

xFeO

4) systems provide an effective model for investigating such effects, having in mind that introducing Sr

2+ in place of La

3+ in prototype perovskite oxides, such as LaFeO

3, can improve catalytic performance in VOCs oxidation by generating defects, including Fe

4+ species and oxygen vacancies [

27,

28,

29]. In this substitution, the incorporation of a cation with a lower oxidation state (Sr

2+) at the A-site leads to the partial oxidation of the B-site cation (Fe) to Fe

4+ and/or the creation of oxygen vacancies to preserve charge balance. These structural adjustments (most notably the enhanced presence of Fe

4+ and oxygen vacancies) promote catalytic activity by facilitating the redox processes essential for VOCs oxidation.

This study aims to synthesize a series of lanthanum–strontium ferrite catalysts with the general formula La2−xSrxFeO4 (where x = 0.5, 1.0, and 1.5) and to investigate their physicochemical properties and catalytic performance. The primary objective is to evaluate their activity in the complete oxidation of light hydrocarbons (C1–C4 alkanes), thereby assessing their potential application as efficient oxidation catalysts for environmental and energy-related processes.

2. Results

The catalysts studied are with the nominal composition La2−xSrxFeO4, where x = 0.5, 1, and 1.5, denoted as follows: La1.5Sr0.5FeO4 (as L15S5F), LaSrFeO4 (as LSF), and La0.5Sr1.5FeO4 (as L5S15F).

2.1. Catalytic Tests

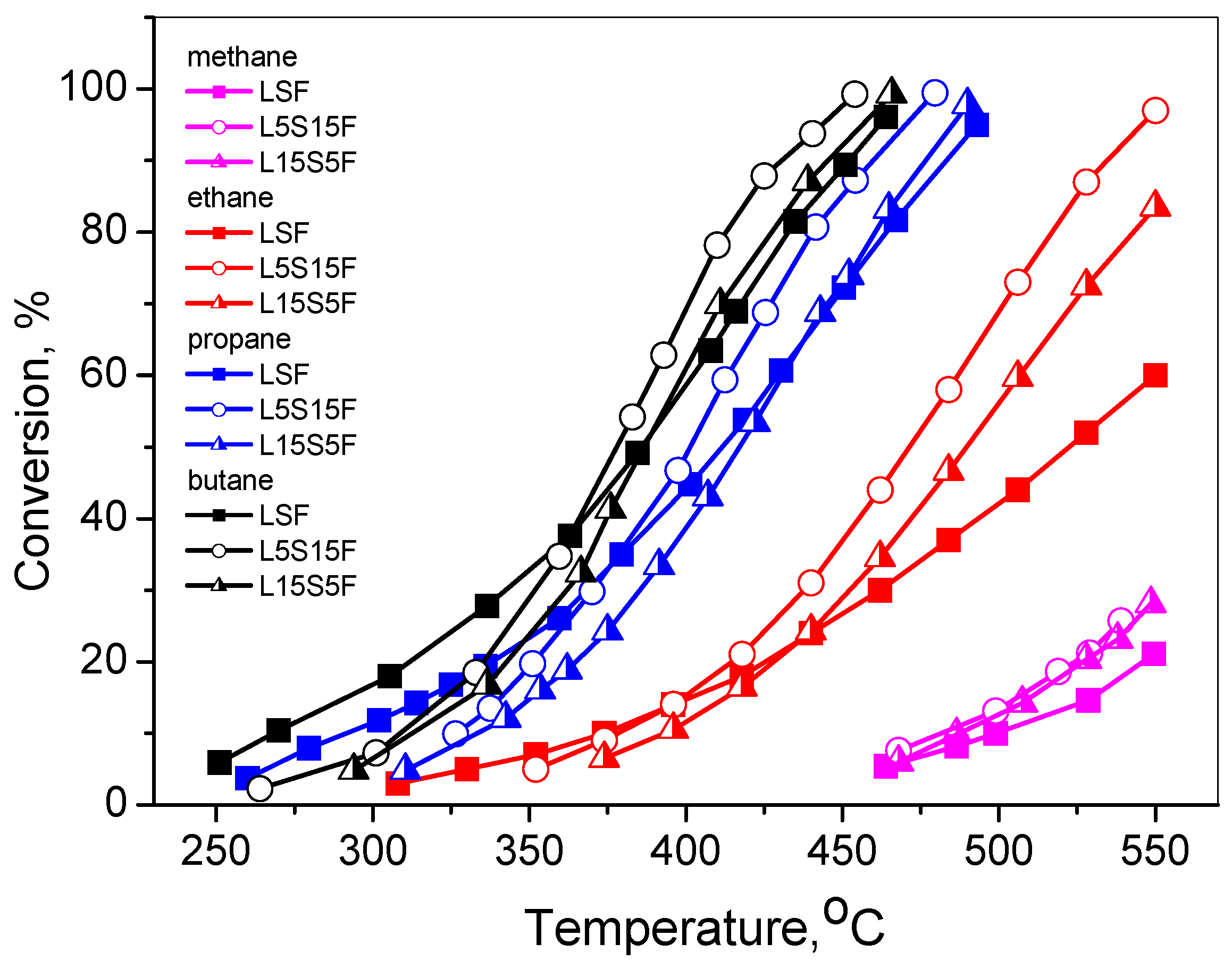

The temperature dependences of the VOC (methane, ethane, propane, and n-butane) conversion degrees are presented in

Figure 1.

The data from the tests of the VOC oxidation showed that their complete oxidation occurred at relatively high temperatures (above 200 °C), with the lowest values for “light-off” T

50 and T

90 indicating a nearly complete oxidation being observed for n-butane (

Figure 1,

Table 1).

It should be pointed out that for all VOCs, complete oxidation to CO

2 and H

2O was detected. Obviously, the most difficult to oxidize among the tested compounds was methane, and the increase in the reaction temperature of propane to methane oxidation correlated with the strength of the C-H bond of the n-alkanes [

30]. The values as reported by Zboray et al. [

31] are the following: methane—439 kJ/mol, ethane—421 kJ/mol, and propane—411 kJ/mol.

It could be seen that generally the highest activity was observed for L5S15F, the lowest being for LSF. However, at low conversion degrees of butane, propane, and ethane, LSF showed slightly higher activity than the other two catalysts.

Taking into account the different test conditions and using first-order kinetics, the data from the literature were recalculated, and the comparative analysis of results showed a similar range of reaction rates for ethane combustion on the activated natural manganese ore and Co

3O

4 [

32] and propane combustion on LaMnO

3, La

0.8Ca

0.2MnO

3, and La

0.8Sr

0.2MnO

3 perovskites [

33].

2.2. Nitrogen Physisorption

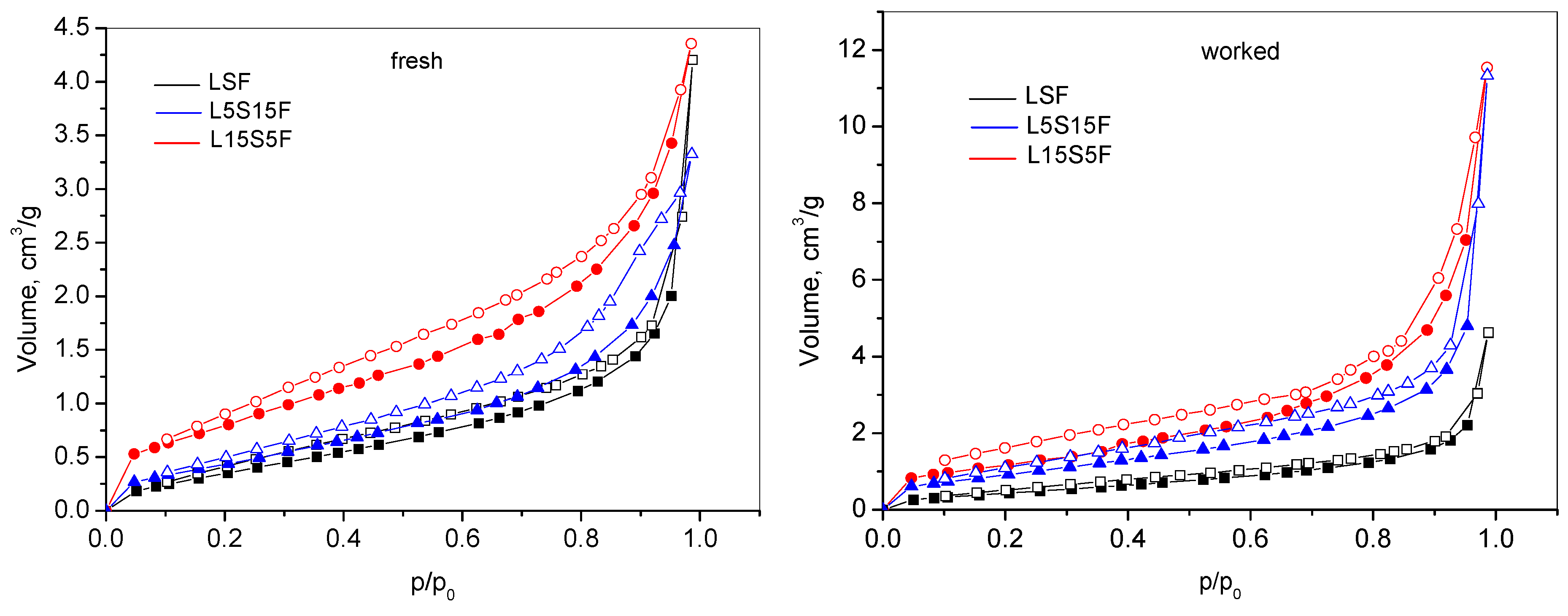

Adsorption–desorption nitrogen isotherms of the studied materials are presented in

Figure 2.

According to the IUPAC classification, the nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms of all studied samples correspond to Type II, accompanied by a characteristic H3 hysteresis loop [

34]. This type of isotherm is typically observed in macroporous or non-porous materials. The occurrence of pronounced hysteresis indicates that the material is not purely non-porous or macroporous. The hysteresis loop suggests the presence of mesopores or pore-network imperfections that induce capillary condensation during desorption. Thus, multilayer adsorption dominates the initial adsorption branch consistent with a Type II isotherm, but delayed evolution of nitrogen within the mesoporous parts results in the appearance of hysteresis loop H3. The measured isotherms reflect the combination of adsorption on a predominantly non-porous surface and capillary condensation effects arising from the mesoporous part. This adsorption profile is commonly found in lamellar or layered materials, including disordered metal oxides, hydroxides, and other plate-like structures.

The textural properties, including specific surface area (S

BET), total pore volume (V

t), and average pore diameter (D

av), are summarized in

Table 2.

Due to the nature of the synthetic method, the as-prepared ferrite samples exhibited relatively low surface areas and pore volumes. Among the various compositions, the strontium-rich sample showed the highest specific surface area, likely due to specific phase composition accompanied by enhanced structural disorder introduced by high Sr content. Following catalytic testing, a noticeable increase in SBET, Vt, and Dav was observed across all samples. This enhancement, seen after VOC oxidation, was attributed to several factors: thermal activation, surface cleaning, and redox-controlled structural modifications.

2.3. X-Ray Diffraction

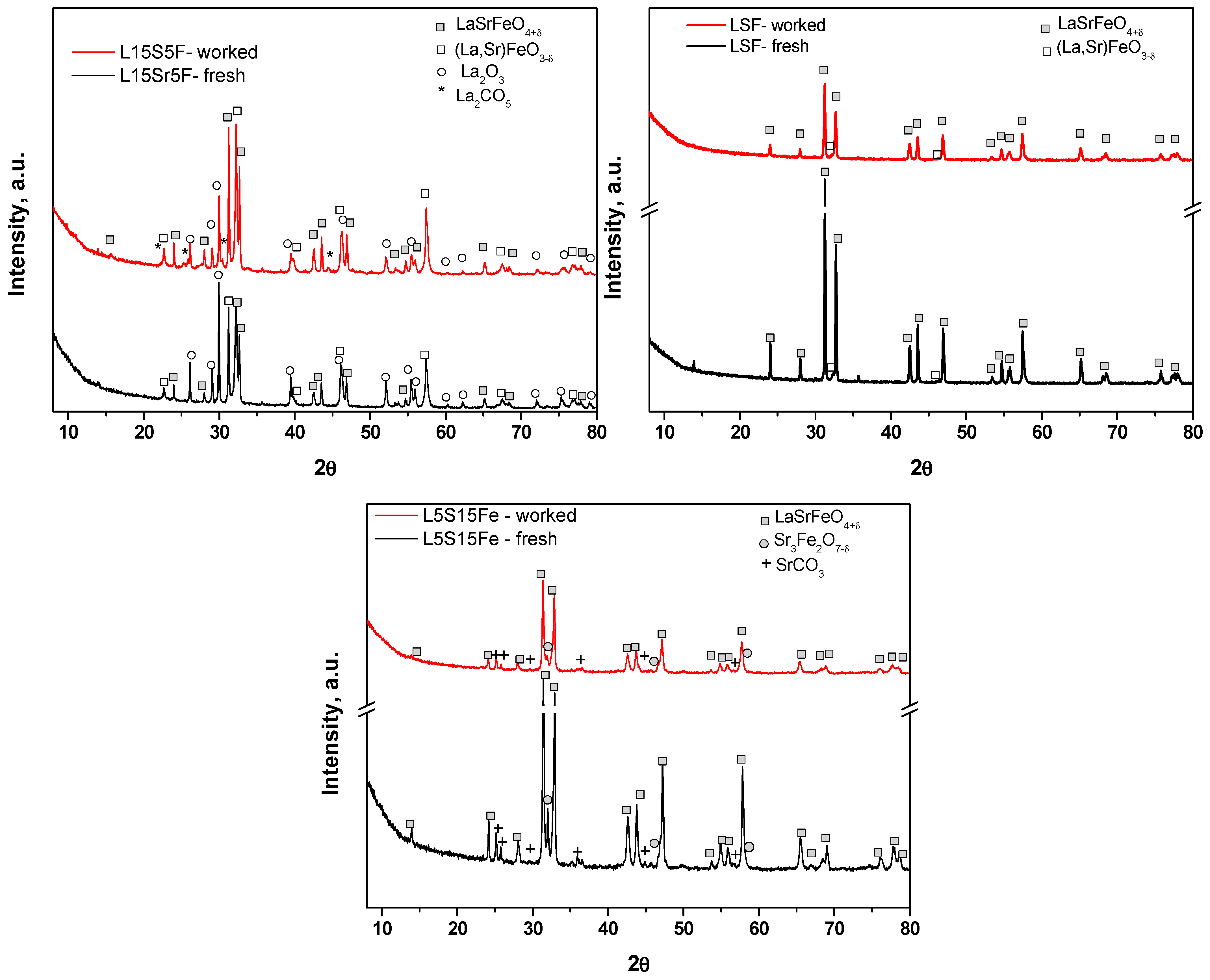

XRD patterns of the La

2−xSr

xFeO

4 fresh and worked catalysts are presented in

Figure 3. The phase composition, unit cell parameters, and mean crystallite sizes derived from XRD patterns are shown in

Table 3.

In the case of the catalyst L15S5F, in addition to the main LaSrFeO4+δ phase, a significant amount of the (La,Sr)FeO3−δ as well as La2O3 phases were detected. The high crystallite size was observed for LaSrFeO4+δ and La2O3 phases, while the crystallites of the (La,Sr)FeO3−δ were two to three times smaller. The effect of the catalytic reaction on the phase composition of the catalyst was more pronounced in this case. The LaSrFeO4+δ phase remained stable with unchanged quantity, unit cell parameters, and the mean crystallite size, while the phase (La,Sr)FeO3−δ was observed to have a reduced quantity after reaction. The latter fact, combined with the decrease in the La2O3 and the detection of a significant quantity of the La2CO5 phase, suggested a phase transformation under reaction conditions.

The fresh catalyst LSF contained as a main phase LaSrFeO

4+δ, the

n = 1 Ruddlesden–Popper (RP) phase with unit cell parameters close to those reported in the literature [

23]. The mean crystallite size of 165 nm revealed the high crystallinity of the obtained material. Traces of the impurity phase (<3%) with perovskite structure and probable composition (La,Sr)FeO

2.7 were seen, pointing to some inhomogeneity on the surface or grain boundaries. After the catalytic reaction, the phase composition and the unit cell parameters remained almost unchanged. The only difference was the significant decrease in the mean crystallite size of the LaSrFeO

4+δ phase, which was also pointed out by the results from nitrogen adsorption. Such a decrease in the crystallite size (mean coherent domain size) could be related to the mobility of lattice oxygen and oxygen vacancy species, leading to the formation of various structural defects and thus to the effective morphology changes [

35].

The as-synthesized sample L5S15F showed the presence of three phases, namely two Ruddlesden–Popper phases with

n = 1 and

n = 2, and SrCO

3, the RP with

n = 1 phase being predominant. It showed a slightly lower c-parameter than the LSF, indicating an increase in the δ value associated with the increase in the Fe

4+ content [

36], which was in accordance with the results from Mössbauer spectroscopy (see below). Assuming the accuracy of the method, the observed phase composition fitted well with the nominal one. After the catalytic reaction, the phase composition and the unit cell parameters remained almost unchanged. The difference, as in the previous case, was in the decrease in the mean crystallite size of all phases of the catalyst, but the decrease was moderate.

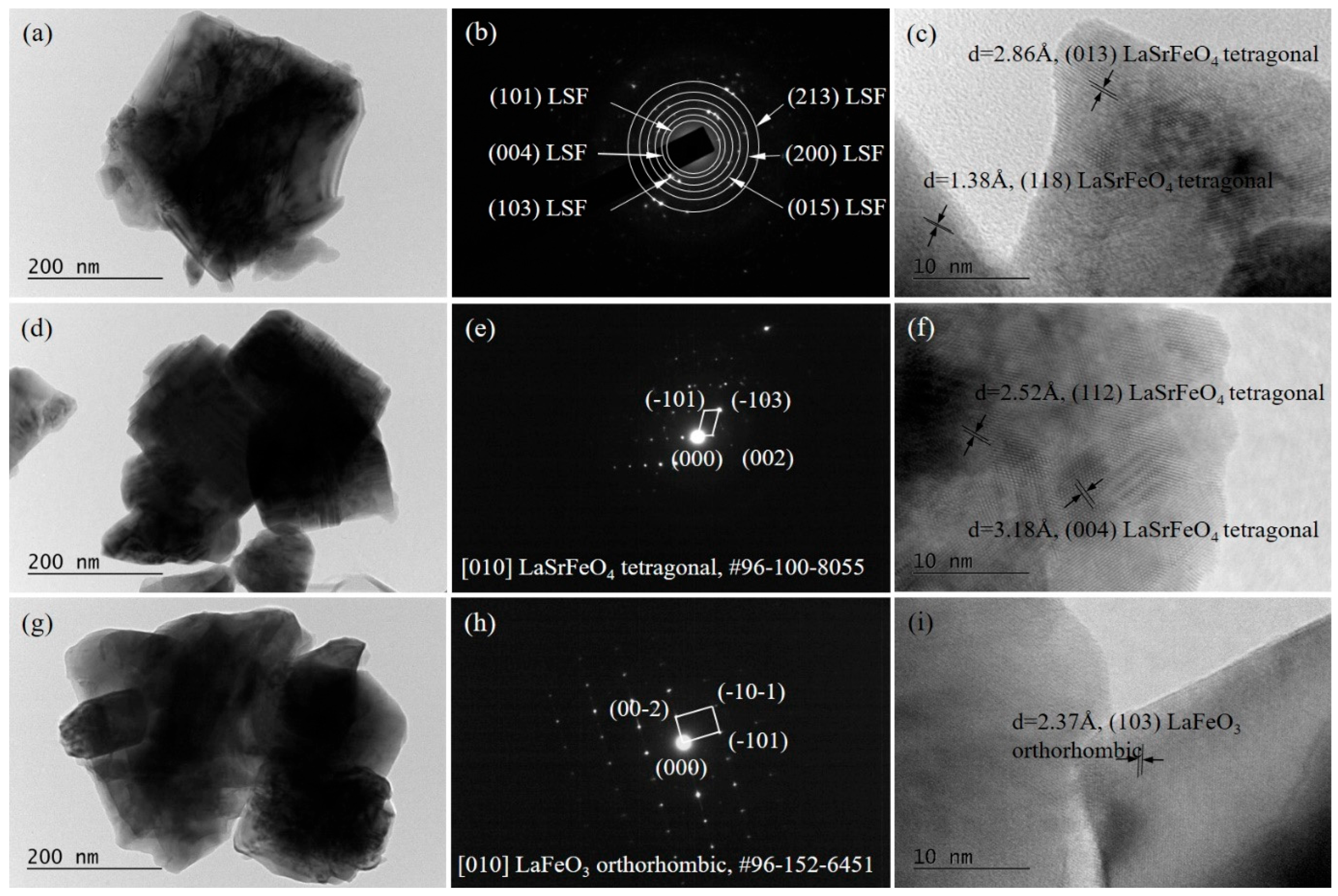

2.4. Transmission Electron Microscopy

The results of the microscopic examination of the freshly prepared LSF, L5S15F, and L15S5F catalytic materials are presented in

Figure 4. For all investigated samples, the recorded micrographs revealed particles with irregular morphologies and distinctly defined edges, features that were typically associated with good crystallinity. The particle dimensions were non-uniform, ranging from several tens to a few hundred nanometers, indicating a heterogeneous microstructure. These observations were consistent with the corresponding electron diffraction patterns, which in most cases exhibited well-defined single-crystalline spots rather than diffuse rings, further confirming the crystalline nature of the samples.

High-resolution TEM (HRTEM) images provided additional structural information. Clearly resolved lattice fringes were observed, enabling the measurement of interplanar spacings and facilitating phase identification. The analysis of these lattice fringes confirmed the presence of the n = 1 Ruddlesden–Popper phase, namely LaSrFeO4 (tetragonal, a = 3.878 Å, c = 12.723 Å; COD Entry #96-100-8055), in both the LSF and L5S15F samples. In contrast, the L15S5F material contained a large amount of the LaFeO3 perovskite phase (orthorhombic, orthorhombic, a = 5.552 Å, b = 5.563 Å, c = 7.843 Å, COD Entry #96-152-6451). These microscopic findings were in excellent agreement with the phase compositions determined independently by X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis, thereby providing mutual confirmation of the bulk phase composition of the synthesized catalytic materials.

2.5. Mössbauer Spectroscopy

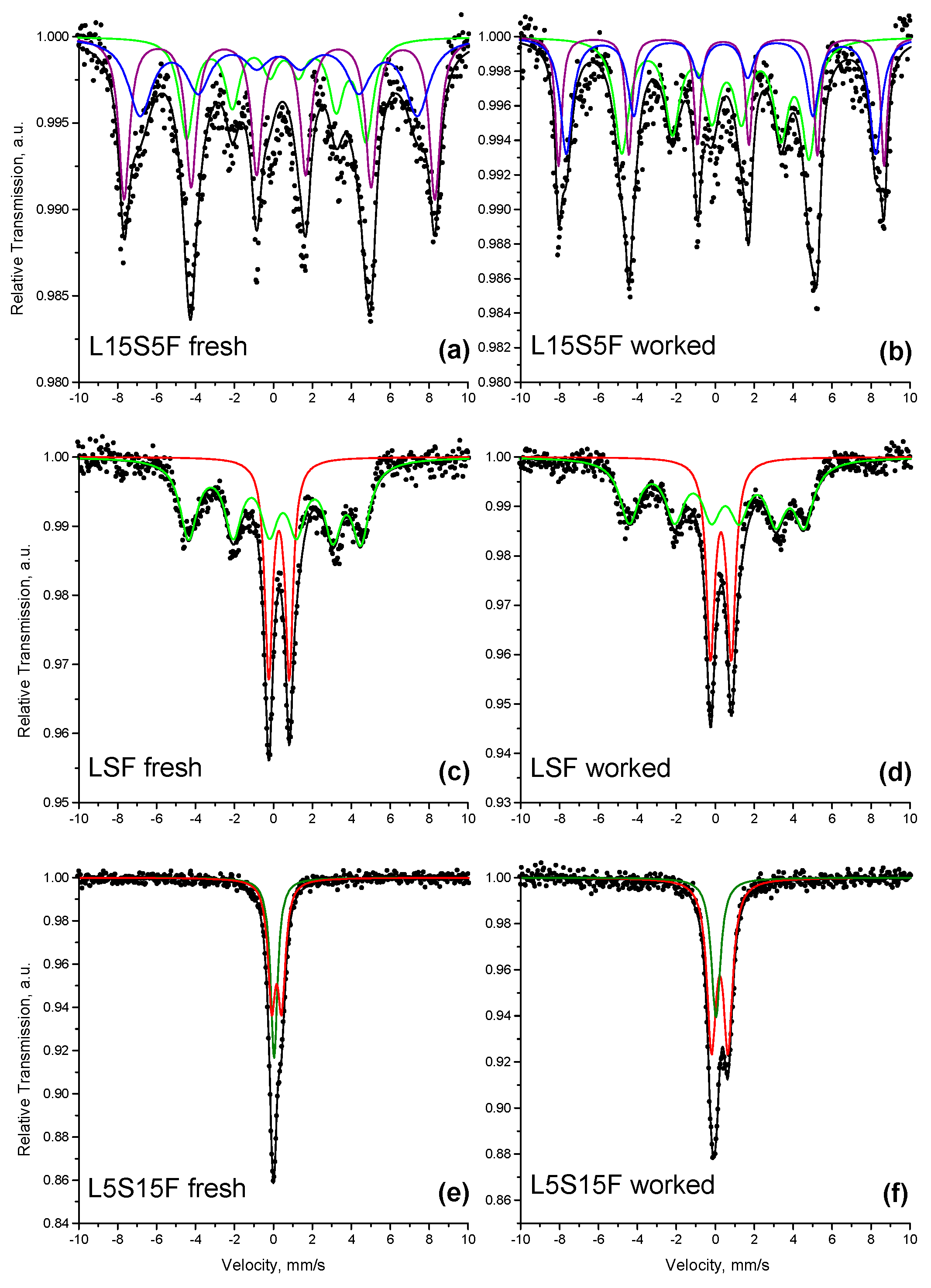

The Mössbauer spectra of the fresh and worked samples L15S5F, LSF, and L5S15F are presented in

Figure 5. The fitting results are summarized in

Table 4.

The Mössbauer spectrum of the L15S5F sample was best fitted using a model consisting of three sextet components. The isomer shifts in all sextets were calculated in the range of 0.26–0.36 mm/s, which is typical for iron in the 3+ oxidation state. Sx3 was evaluated with a significantly higher quadrupole shift and could be attributed to the single-layered RP phase LaSrFeO

4, which is known to exhibit strong elongation of the apical Fe-O bond in FeO

6 octahedra [

37]. On the other hand, sextet Sx1 has a significantly lower quadrupole shift and hyperfine field (

Bhf = 49.5 T) than Sx3 and could be assigned to the orthorhombic perovskite phase, which was also found in XRD and TEM results. Sextet Sx2 has a smaller field than Sx1 and broader line widths, probably due to the manifestation of relaxation phenomena in perovskite particles. The experimental spectrum of the L15S5F sample after the catalytic test (

Figure 4b) did not change in appearance, and the same fitting model was used. As seen in

Table 4, the isomer shifts in all sextets in the spectrum of the worked sample remain within the range typical of the 3+ oxidation state of iron. The hyperfine fields of the sextets increased in the worked sample compared with the fresh sample, which is a sign of increasing particle size and/or a reduction in defects in the crystal structure.

The Mössbauer spectrum of the LSF sample is shown in

Figure 4c, and the fitting results are summarized in

Table 4. The measured spectrum contains both sextet and doublet components. The calculated isomer shifts of 0.28 mm/s and 0.29 mm/s confirm that all iron in the sample is in the Fe

3+ state. The quadrupole splitting of the doublet (Δ = 1.05 mm/s) is characteristic of the paramagnetic LaSrFeO

4 phase, while the calculated parameters of the sextet are consistent with previous reports [

38]. The coexistence of doublet and sextet components in the spectrum, despite the reported Néel temperature of LaSrFeO

4 being 57 °C [

39], can likely be attributed to La/Sr disorder in the vicinity of Fe atoms. No significant change can be observed in the experimental spectrum or in the calculated parameters of the worked sample, as shown in

Figure 5d and

Table 4. The results confirm the findings from XRD analyses.

The Mössbauer spectrum of the L5S15F sample is a superposition of a singlet and a doublet, as shown in

Figure 5e. The fitted parameters of the singlet (δ = 0.04 mm/s,

Table 1) are typical of Fe

4+ in perovskite and perovskite-related structures [

40]. The isomer shift in the doublet falls between the values typical of Fe

4+ and Fe

3+ (

Table 4). Therefore, the iron responsible for this doublet can be assigned an average oxidation state of 3.5+, as reported in previous studies [

40,

41]. The spectral components of the sample after the catalytic test are generally preserved, while the Fe

3.5+/Fe

4+ ratio increases slightly (

Figure 5f and

Table 4).

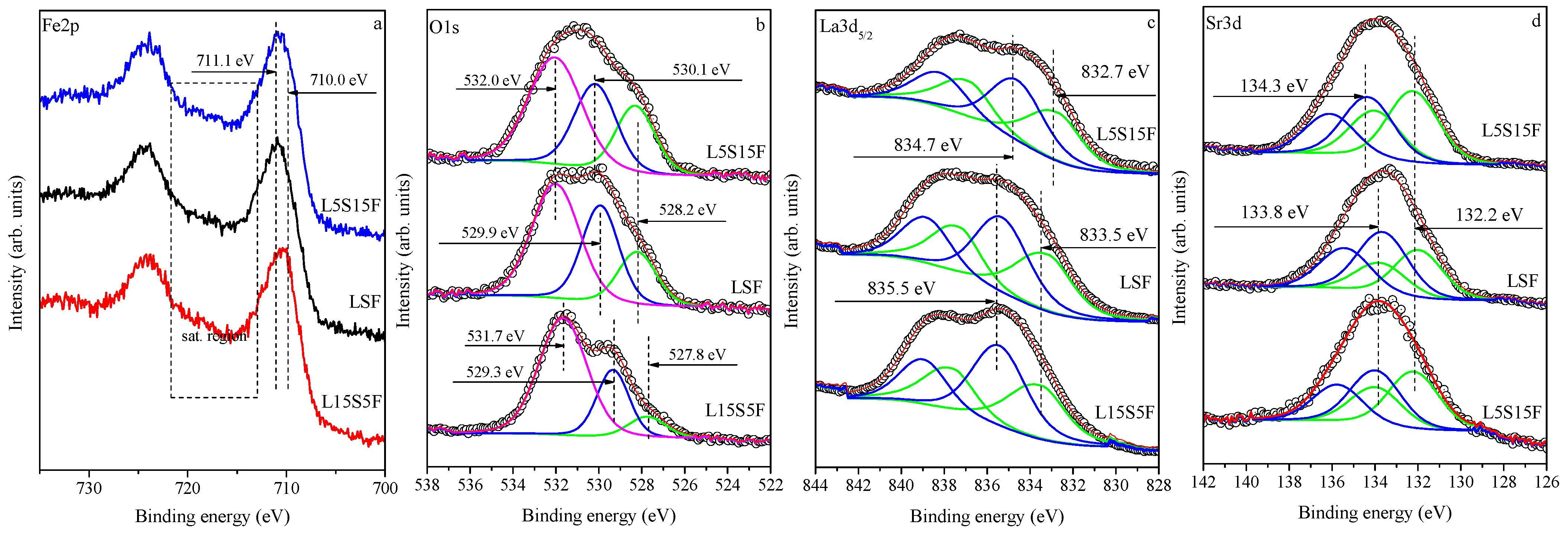

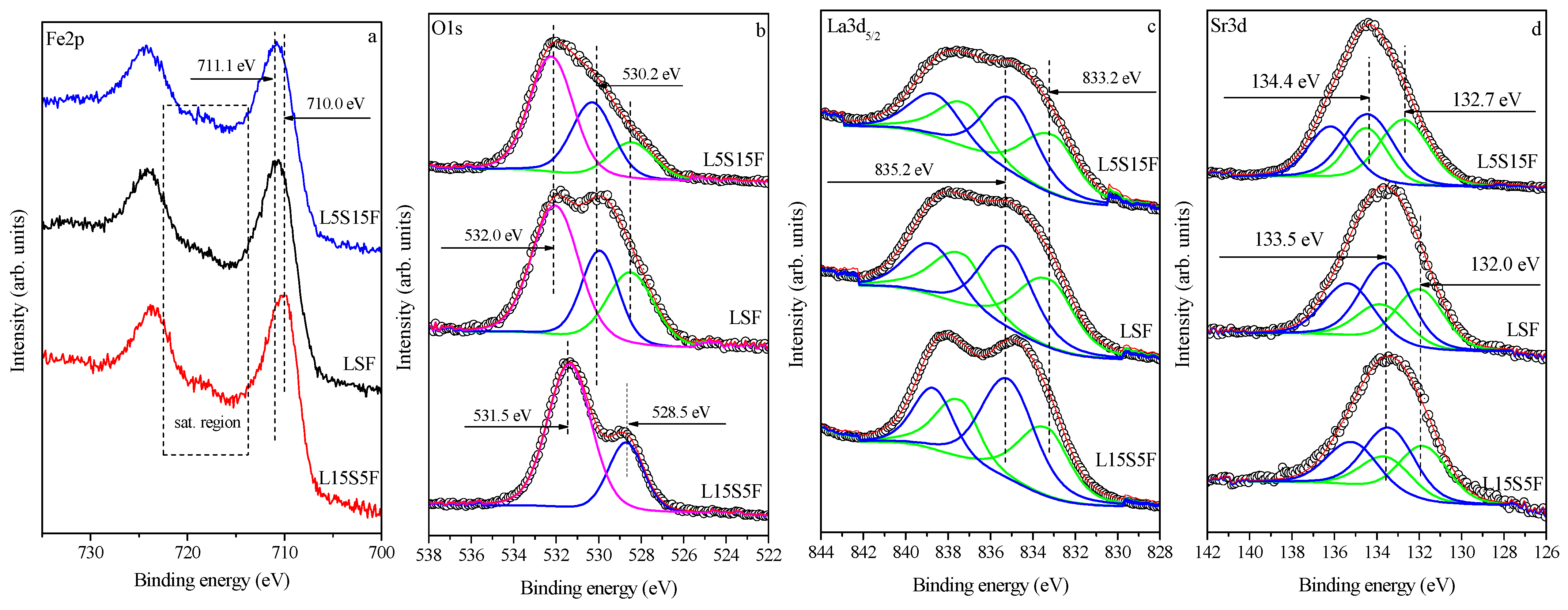

2.6. X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy

As the catalytic process is a surface phenomenon, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy was performed to obtain information regarding the surface properties of the investigated samples. The surface atomic concentrations of the L15S5F, LSF, and L5S15F samples before and after catalysis are summarized in

Table 5. The surface carbon content (12–18 at. %) originates from adventitious hydrocarbons and residual carbonates; approximately half of the detected carbon corresponds to carbonate species. This contamination explains part of the excess oxygen measured, up to 3.5 times higher than nominal stoichiometric expectations; the rest is attributed to the peculiar phase composition of the samples. The expected La:Sr ratios are approximately 3, 1, and 1/3 for L15S5F, LSF, and L5S15F, respectively. The calculated ratios of 2.0, 1.1, and 0.3 (for fresh samples) and of 2.8, 1.4, and 0.3 (for worked samples) are close to the nominal values. In the case of L15S5F, the surface of the fresh catalyst is slightly enriched in lanthanum. After the catalytic reaction, a newly formed La

2CO

5 (observed also in XRD) is obviously situated on the surface, thus increasing the La:Sr ratio. The slight increase in the La:Sr ratio after the catalytic reaction for LSF can be attributed to limited surface segregation. The Fe concentration remains nearly constant (≈6 at.%). The La:Sr ratio for L5S15F after the catalytic reaction remained unchanged, suggesting the catalyst’s surface stability during reaction exposure, which was also observed in XRD.

The key objective was to determine the oxidation state of iron as a function of Sr content.

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 present Fe 2p, O 1s, La3d

5/2, and Sr3d XPS spectra with increasing Sr content (bottom-to-top) for both series of the samples, fresh and worked, respectively. Two indicators of iron oxidation state were assessed: the binding energy (BE) of the Fe 2p

3/2 core level and the satellite structure. High-resolution Fe 2p spectra (

Figure 6a and

Figure 7a) exhibit broad, asymmetric Fe 2p

3/2 peaks (BE 710.0–711.1 eV) with distinct satellites in the 714–722 eV range. The satellite at ~719 eV is characteristic of Fe

3+, while its progressive attenuation and shift toward 720–721 eV with increasing Sr content indicate enrichment of Fe

4+ species at the surface, consistent with earlier studies on SrFeO

3-type perovskites [

42]. These observations confirmed the presence of both Fe

3+ and Fe

4+ at the surface, with increasing Fe

4+ content as Sr increased. After catalysis, the Fe

3+ satellite near 719 eV becomes more pronounced for Sr-rich samples (

Figure 7a), indicating a partial reduction in Fe

4+ to Fe

3+ during VOC oxidation. This reversible redox cycling (Fe

4+ ↔ Fe

3+) reflected oxygen vacancy formation and reoxidation processes typical for perovskite-type catalysts, directly linked to their catalytic activity. The XPS results were in agreement with the Mössbauer analysis.

The O 1s spectra (

Figure 6b and

Figure 7b) were resolved into three components: (i) a low-binding-energy peak (527.7–528.2 eV) attributed to Sr–O bonds [

42]; (ii) a lattice oxygen component (529.3–530.2 eV) corresponding to La–O/Fe–O bonds; and (iii) a high-binding-energy component (531.7–532.0 eV) assigned to hydroxyl and carbonate species [

43]. These were considered contamination from synthesis and handling. Similarly to the iron spectra, changes in the line shapes from the spectra before and after catalysis are observed, which lead to different intensities or ratios of the peak components. Before catalysis, the Sr–O signal (green line in

Figure 6b) increases with Sr substitution, reflecting the formation of Sr-rich surface domains. After catalysis, this component notably diminished for L15S5F, consistent with surface Sr depletion or migration into the bulk and the concurrent formation of carbonate or hydroxide overlayer species. Two main factors can influence the observed binding-energy variations with increasing Sr content: (i) modifications in electronic band structure and charge transfer among Fe, O, La, and Sr ions caused by Sr

2+ → La

3+ substitution; and (ii) local surface charging effects resulting from the coexistence of phases with distinct conductivity and work function, such as La

2−xSr

xFeO

4, SrCO

3, and La(OH)

3. Such Sr segregation and La enrichment at the surface can reduce oxygen mobility and slightly affect catalytic performance under repeated operation.

The formation of carbonates and hydroxides on the surface is also evidenced by the curve fitting of the La 3d

3/2 spectra shown in

Figure 6c and

Figure 7c for the samples before and after catalysis, respectively. The components marked in green, with binding energies in the range of 832.7–833.5 eV, are attributed to La–O bonds [

44,

45], whereas the blue components in the range of 834.7–835.5 eV correspond to La

2(CO

3)

2 and/or La(OH)

3 [

46]. These results confirmed the findings of the XRD analyses showing the presence of carbonate-containing phases. The calculated ratio between these two components is approximately 1:1 for all investigated samples (see

Table 5).

The Sr3d spectra shown in

Figure 6d and

Figure 7d exhibit two components, namely the Sr–O bonding (green line) with a binding energy range of 132.2–132.7 eV [

47] and the SrCO

3 component (blue line) with a range of 133.5–134.4 eV [

47], for both series of samples before and after catalysis, respectively. The calculated ratio between these components varies inconsistently with Sr content, from 0.7 to 1.2 for all investigated samples, depending on the extent of carbonate formation on the surface covering the RP or perovskite species.

A semi-quantitative Fe

4+/Fe

3+ surface oxidation-state ratio for fresh La

2−xSrₓFeO

4 samples can be derived by analyzing the relative intensities of the O 1s low-binding-energy component assigned to Sr-O (green lines in

Figure 6b and

Figure 7b) and the lattice-oxygen component associated with La-O (blue lines), while excluding the contributions from hydroxide and carbonate species. The estimated Fe

4+/Fe

3+ surface ratios increase with Sr content, with values of 0.37 for L15S5F, 0.58 for LSF, and 0.74 for L5S15F, indicating a progressive enrichment of Fe

4+ at the surface as Sr content increases. These values should be viewed as relative indicators rather than exact oxidation states.

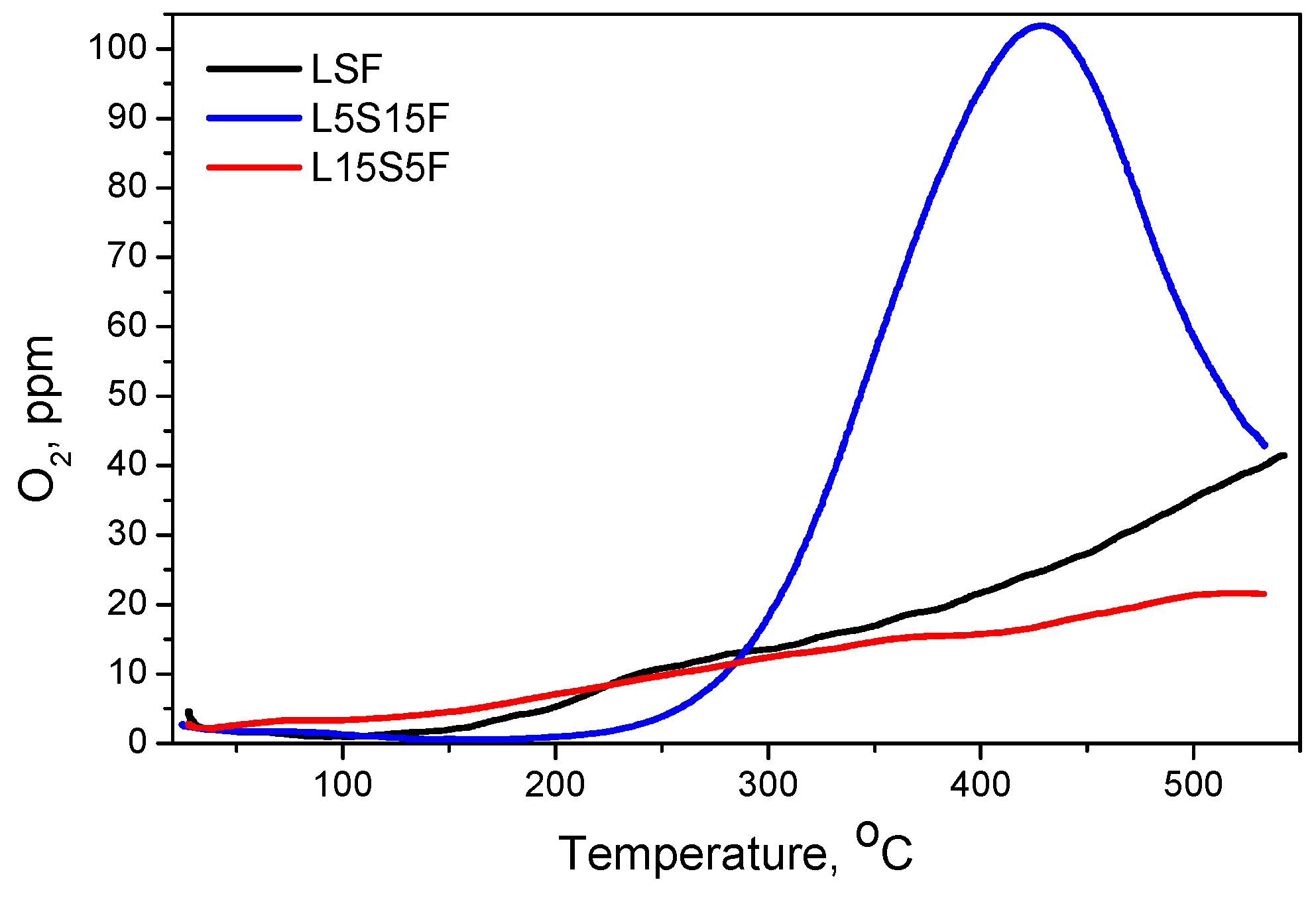

2.7. Oxygen–Temperature Programmed Desorption and Depletive Oxidation

Oxygen-TPD and so-called “depletive” oxidation [

48,

49] were used to shed some light on the catalytic behavior, aiming to supplement the considerations regarding the mechanism of the catalytic reaction.

The O

2-TPD experiments were performed in order to obtain information regarding the oxygen adsorptive properties of the catalysts. The selected temperature range was the same as the one used for the catalytic activity tests; the heating temperature was limited to 550 °C [

50].

The O

2-TPD analysis is shown in

Figure 8. The O

2-TPD of L15S5F shows broad peaks at ~310 °C and ~503 °C. Similar to this is the curve for LSF, showing oxygen desorption above 150 °C with a broad peak at ~283 °C and continuous evolution as the temperature approaches 550 °C. Remarkably different is the case for L5S15F, where a well-defined peak in the range 200–550 °C, centered at 430 °C, is observed. The estimated amounts of desorbed oxygen are calculated as follows: L15S5F—51 μmol/g

cat, LSF—76 μmol/g

cat, L5S15F—172 μmol/g

cat. These amounts correlate well with the activity of the corresponding catalysts—the higher the capacity of adsorbed oxygen, the higher the activity. Boreave et al. [

51] investigated single-layer (RP,

n = 1) phases La

2NiO

4 and La

1.9Sr

0.1NiO

4, and their O

2-TPD experiments revealed that these materials exhibited exceptionally high bulk oxygen mobility, despite having relatively low specific surface areas.

This behavior was attributed to the ability of interstitial oxygen to exchange with the gas phase starting at about 230 °C. Moreover, at temperatures below 300 °C, this interstitial oxygen reacted with propane to form CO

2. Leontiou et al. [

18] found that the progressive substitution of La

3+ by Sr

2+ resulted in a proportional formation of the SrFe

4+O

3 perovskite phase, accompanied by a corresponding reduction in the remaining iron-containing phases. The same phenomenon was observed in the present study, where the increased amount of strontium led to the formation of Sr

3Fe

2O

7−δ (RP,

n = 2) and to a decrease in the quantity of the other iron-containing phase (RP,

n = 1). O

2-TPD analyses demonstrated that this material releases oxygen upon heating, with the extent of desorption proportional to the Fe

4+ content.

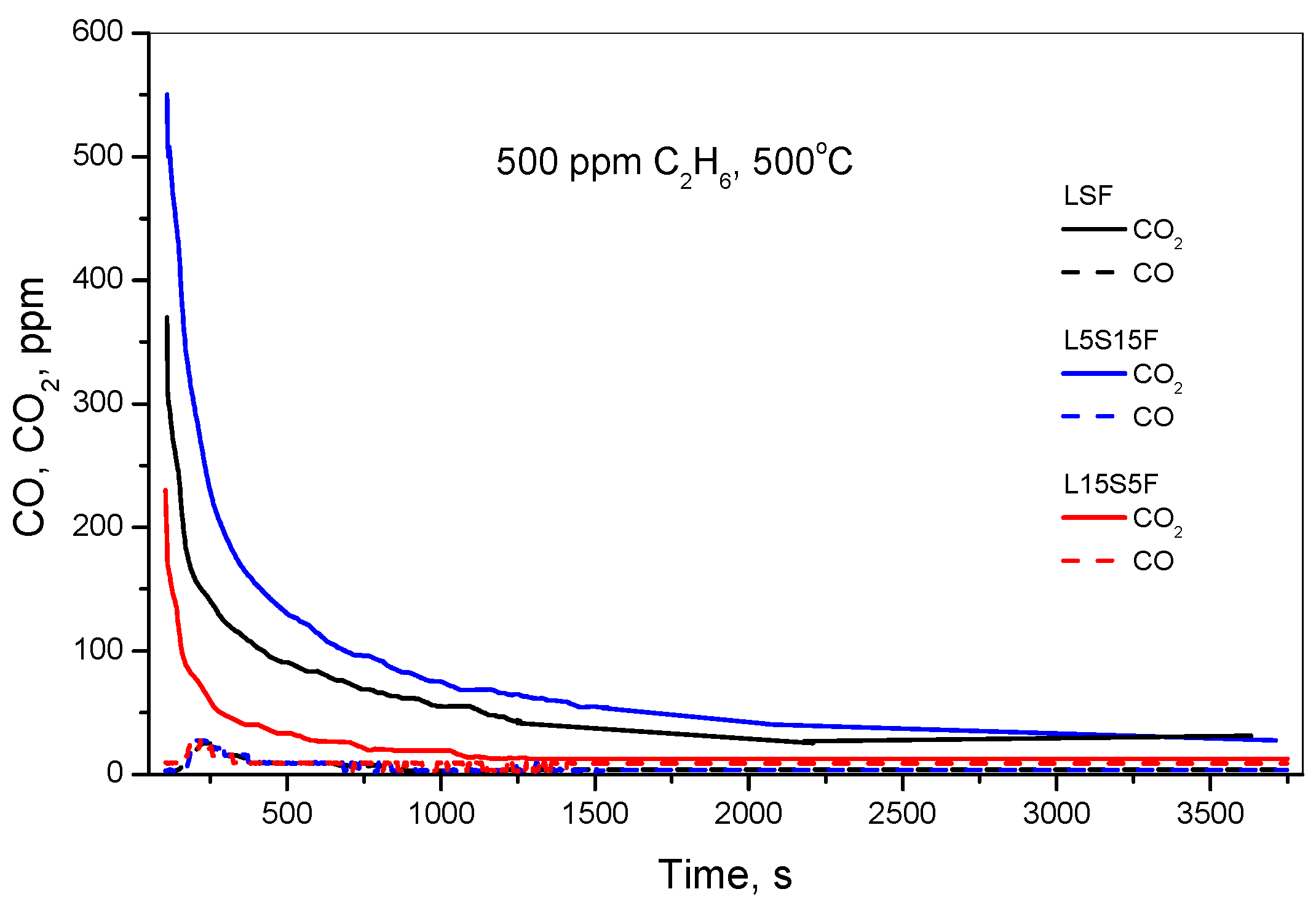

In order to compare the reactivity of oxygen species of the catalysts under investigation, the study was extended with the “depletive” oxidation test. The test involved halting the oxygen supply in the feed gas mixture once steady-state conditions were achieved, and then monitoring the formation of oxidation products. The results from “depletive” oxidation, presented in

Figure 9, give the amount of CO

2 formed from the reaction with C

2H

6. The online gas analysis shows that the “depletive” oxidation of all catalysts leads to the formation of CO

2 and H

2O, which evolved immediately after the termination of oxygen supply. Negligible amounts of CO were also detected in the very initial stage.

The estimated amounts of formed CO2 are calculated as follows: L15S5F—44.3 μmol/gcat, LSF—105.3 μmol/gcat, L5S15F—177 μmol/gcat. Obviously, the outcomes from the “depletive” oxidation experiments were consistent with both the catalytic activity measurements and the O2-TPD data. After the “depletive” oxidation and subsequent re-oxidation tests, all samples successfully recovered their initial activity. Once again, the L5S15F sample demonstrated superior performance compared to LSF and L15S5F.

The higher amount of available oxygen at low temperatures observed for the L5S15F sample can be ascribed to an enhanced oxygen diffusion rate within the bulk structure, promoted by increased Sr substitution, leading to overall greater oxidation activity [

28]. The catalytic performance of perovskite-type oxides was strongly affected by the presence of oxygen vacancies, which served as active sites that facilitated the adsorption and activation of reactant molecules [

52]. Oxygen molecules were trapped at these vacancies and transformed into reactive oxygen species, such as O

2− and O

−. These species reacted with VOC molecules in a manner analogous to lattice oxygen during VOC oxidation, resulting in the temporary reduction in the catalyst. Subsequently, oxygen from the gas phase re-oxidized the reduced catalyst by replenishing the oxygen vacancies, thereby restoring the original structure and completing the catalytic cycle [

53]. This process was consistent with the Mars–van Krevelen reaction mechanism.

Similar to the findings in the present study, a correlation between the activity and selectivity of chemical-looping methane oxidation and the oxygen mobility in La

1−xSr

xFeO

3−δ (x = 0, 0.2, and 0.5) was found by other authors [

28]. They found that oxygen mobility, controlled by how easily oxygen vacancies form, played the main role in determining surface oxygen and vacancy concentrations in perovskites. This mobility depended on bulk oxygen content and the relative rates of lattice oxygen diffusion and surface reactions. Perovskites with higher oxygen mobility were especially effective for complete methane combustion.

2.8. Kinetic Studies

For the kinetic study, ethane was selected as a representative of the used n-alkanes due to its intermediate reactivity, positioned between that of methane on one side and propane and butane on the other. The inlet reagent concentrations were varied, and the corresponding kinetic parameters were determined, following the approach described by Duprat [

54]. Details of the calculation procedure have been reported in [

55]. The kinetic parameters were obtained by solving the material balance equations for an isothermal plug-flow reactor (PFR). A nonlinear numerical optimization based on iterative gradient reduction was employed to minimize the residual sum of squares (RSS) between the experimental and model-predicted conversions. The square of the correlation coefficient (R

2) was also evaluated. The fitting procedure was repeated multiple times under different reaction conditions to ensure consistency.

As a first approximation, a power-law (PWL) kinetic model was applied (

Table 6). The reaction order with respect to oxygen (0.1–0.2) suggests that oxygen participates via dissociative adsorption on the catalyst surface, while the reaction order for ethane indicates the possibility of a direct gas-phase reaction following the Eley–Rideal mechanism [

56].

Based on the PWL model and the results from the instrumental analyses, the following mechanistic kinetic models were selected for fitting to the experimental data:

Mars–van Krevelen (MVK): Oxidation proceeds via the oxygen from the catalyst, and ethane is reducing the catalyst, while the oxygen from the gas phase is dissociated and oxidizing the catalyst;

Langmuir–Hinshelwood (LH-DS-D): Ethane and oxygen react in their adsorbed state, with competitive adsorption of ethane and oxygen on different catalytic sites (DS), featuring dissociative (D) oxygen adsorption;

Eley–Rideal (ER): Ethane reacts directly from the gas phase with adsorbed oxygen species.

The calculated parameters for the mechanistic kinetics models are summarized in

Table 7,

Table 8 and

Table 9.

The lower values of the pre-exponent factor (or the frequency of effective collisions between the reagents and the catalytic surface) indirectly indicate a smaller number of active sites for the LSF sample when compared to the next two samples under investigation. The probable explanation was that the lower activation energies for the LSF sample (PWL-, MVK-, LH- models) were not compensated by the number of active sites available to catalyze the reaction at the working temperatures.

The Eley–Rideal type of mechanism requires a first reaction order for one of the gas phase reagents [

56]. The calculated reaction orders towards the oxygen ranged 0.12–0.17 (

Table 6), which suggested a strong surface adsorption of the oxygen before the reaction with ethane. Thus, the only possibility for the ER mechanism was that the ethane reacted from the gas phase. However, the observed reaction orders towards ethane ranged 0.68–0.84, which was significantly below unity, thus suggesting some extent of reaction with surface ethane (or its derivatives) as a participant. Therefore, despite the better fit between the experimental data and the model predictions (lower values for RSS) for the ER mechanism in comparison with the MVK mechanism, the results from the physicochemical characterization, especially XPS and Mössbauer spectroscopy, showed that the most probable mechanism was the MVK mechanism. The reacting oxygen originated from the catalyst after reaction between the gas-phase oxygen and the catalytic surface; the oxidation step being slower than the reduction in the catalyst (kred > kox, 2–5 times depending on the catalyst).

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Catalyst Preparation

Materials with nominal compositions La2−xSrxFeO4, where x = 0.5, 1, and 1.5, were prepared using a sol–gel auto-combustion technique with the corresponding metal nitrates and citric acid as complexing/fuel agents. The citric acid was used in a molar ratio of 3.3:1 in relation to the sum of the metal ions. In short, the experimental procedure was as follows: La2O3, Sr(NO3)2 and Fe(NO3)3·9H2O in corresponding stoichiometric ratios were dissolved in aqueous solution of nitric acid at room temperature under stirring; citric acid was added to the solution and stirring was continued at 60 °C until the acid was completely dissolved, followed by further stirring and heating at 150 °C. The auto-combustion process was performed by heating the samples in an oven at 200 °C for two hours. The samples were then further thermally treated at 1100 °C for two hours. The samples were denoted as follows: La1.5Sr0.5FeO4 (as L15Sr5F), LaSrFeO4 (as LSF), and La0.5Sr1.5FeO4 (as L5Sr15F).

3.2. Characterization Techniques

The textural characteristics of the catalyst samples were examined by low-temperature nitrogen adsorption in a Quantachrome NOVA 1200e Surface&Pore Analyzer (AntonPaar Quanta Tech Inc., Boynton Beach, FL, USA). The specific surface area was calculated by using the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) equation, the total pore volume and average pore diameter being determined at a relative pressure of 0.99.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurements of the samples were performed at room temperature. Powder diffraction patterns of both fresh and used samples were recorded over the 2θ range of 5–80° using a Bruker D8 Advance diffractometer (Karlsruhe, Germany) equipped with Cu Kα radiation and a LynxEye detector. Phase identification was performed using the Diffracplus EVA (V4) software in combination with the ICDD-PDF2 (2021) database. The unit cell parameters and average crystallite sizes were determined using the Topas 4.2 program, employing the fundamental parameters approach for peak shape modeling and applying the appropriate corrections for instrumental broadening and diffractometer geometry. Phase quantification was performed using the Rietveld quantification method.

The transmission electron microscopy (TEM) study of the catalytic samples was performed with a JEOL JEM 2100 instrument (JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) at an accelerating voltage of 200 kV. The catalysts were firstly dispersed in ethanol, then sonicated for 3 min, and dropped onto Cu grids covered by amorphous carbon films. For the morphology visualization of the samples, a Bright-Field (BF) TEM mode of the microscope was used. The phase composition of the materials was analyzed by means of Digital Micrograph (Version 2.31.734.00) Software (Gatan, Inc., Pleasanton, CA, USA) on the basis of the registered Selected Area Electron Diffraction (SAED) patterns and High Resolution (HR) TEM images. Match Software (Version 3.13, Crystal Impact, Bonn, Germany) was used for comparing with data in the Crystallography Open Database (COD).

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was carried out using an ESCALAB Mk II spectrometer (VG Scientific, now Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at a base pressure of 5 × 10

−10 mbar in the analysis chamber (2 × 10

−9 mbar during measurement), using a non-monochromatic Al K

α source (hν = 1486.6 eV). The pass energy was set to 20 eV for O 1s and C 1s spectra and 50 eV for Fe 2p, Sr 3d, and La 3d in order to balance signal intensity and resolution. The instrumental resolution, determined from the Ag 3d

5/2 line, was approximately 1 eV. Data were processed using

CasaXPS software (version 2.3.25PR1). A Shirley-type background [

57] was subtracted, and the spectra were fitted with mixed Gaussian–Lorentzian functions. Relative atomic concentrations were determined from the peak areas normalized to Scofield photoionization cross-sections [

58].

The Mössbauer spectra were obtained with a WissEl (Wissenschaftliche Elektronik GmbH, Starnberg, Germany) electromechanical spectrometer working in a constant acceleration mode. A 57Co/Rh (activity ≅ 50 mCi) source and α-Fe standard were used. The experimentally obtained spectra were fitted using WinNormos-for-Igor (Version 6.0) software. The parameters of hyperfine interaction, including isomer shift (δ), quadrupole splitting (Δ), quadrupole shift (2ε), effective internal magnetic field (Bhf), line widths (Γexp), and relative weight (G) of the partial components in the spectra, were determined.

Oxygen temperature-programmed desorption (O2-TPD) measurements were obtained utilizing a highly precise SGM4 ZIROX oxygen gas analyzer (ZIROX—Sensoren und Elektronik GmbH, Greifswald, Germany) equipped with a zirconia sensor with a resolution of 0.1 ppm gas phase oxygen. The catalysts were pre-treated using a gas mixture containing 20% O2 and 80% N2, flowing at 500 mL/min for 6 h at 500 °C, followed by cooling to room temperature in the same gas mixture. The heating rate used was 10 °C/min, with a nitrogen carrier gas flow of 500 mL/min.

The tests for “depletive” oxidation were carried out at 500 °C with 500 ppm ethane, and the duration of the experiment was fixed to 60 min, a period within which the emission of oxidation products was almost completed. Gas analysis was conducted using a specialized online gas analyzer for CO/CO2/O2 (Maihak-Sick Mod. 710S, NDIR).

3.3. Catalytic Activity Measurement

Catalytic activity tests were performed in a laboratory-scale continuous-flow glass reactor containing a fixed bed (total volume 0.7 cm3) composed of 0.5 cm3 of catalyst and 0.2 cm3 of quartz glass. The catalyst particles had irregular shapes with an average size of 0.45 ± 0.15 mm. The reactor’s internal diameter was 6 mm, providing a reactor-to-particle diameter ratio (Dreactor/Dparticle) ≥ 10, minimizing axial and radial heat and mass transfer limitations. The gaseous hourly space velocity (GHSV) was maintained at 60,000 h−1 throughout all experiments.

The inlet VOC concentration was fixed at 0.10 vol.% for each gas, with 10.0 vol.% oxygen. The reaction temperature did not exceed 550 °C, which was considered the practical upper limit for VOC abatement applications. For kinetic studies, ethane inlets were 5.0 × 10−4, 1.0 × 10−3, and 2.7 × 10−3 vol.%, and oxygen concentrations were 0.9, 5.0, and 20.0 vol.%. Nitrogen (purity 4.0) was used as the balance gas to maintain a total feed composition of 100 vol.%. Gas flow rates were precisely controlled using Bronkhorst mass flow controllers. Reaction products were analyzed online with a MultiGas FTIR Gas Analyzer (Model 2030G, MKS Instruments Inc., Andover, MA, USA), enabling the quantification of VOCs, CO, CO2, and H2O.