Flavin Fixing in Old Yellow Enzyme from Thermus scotoductus: A Comparative Study of the Wild-Type Enzyme and Covalently Flavinylated Mutants

Abstract

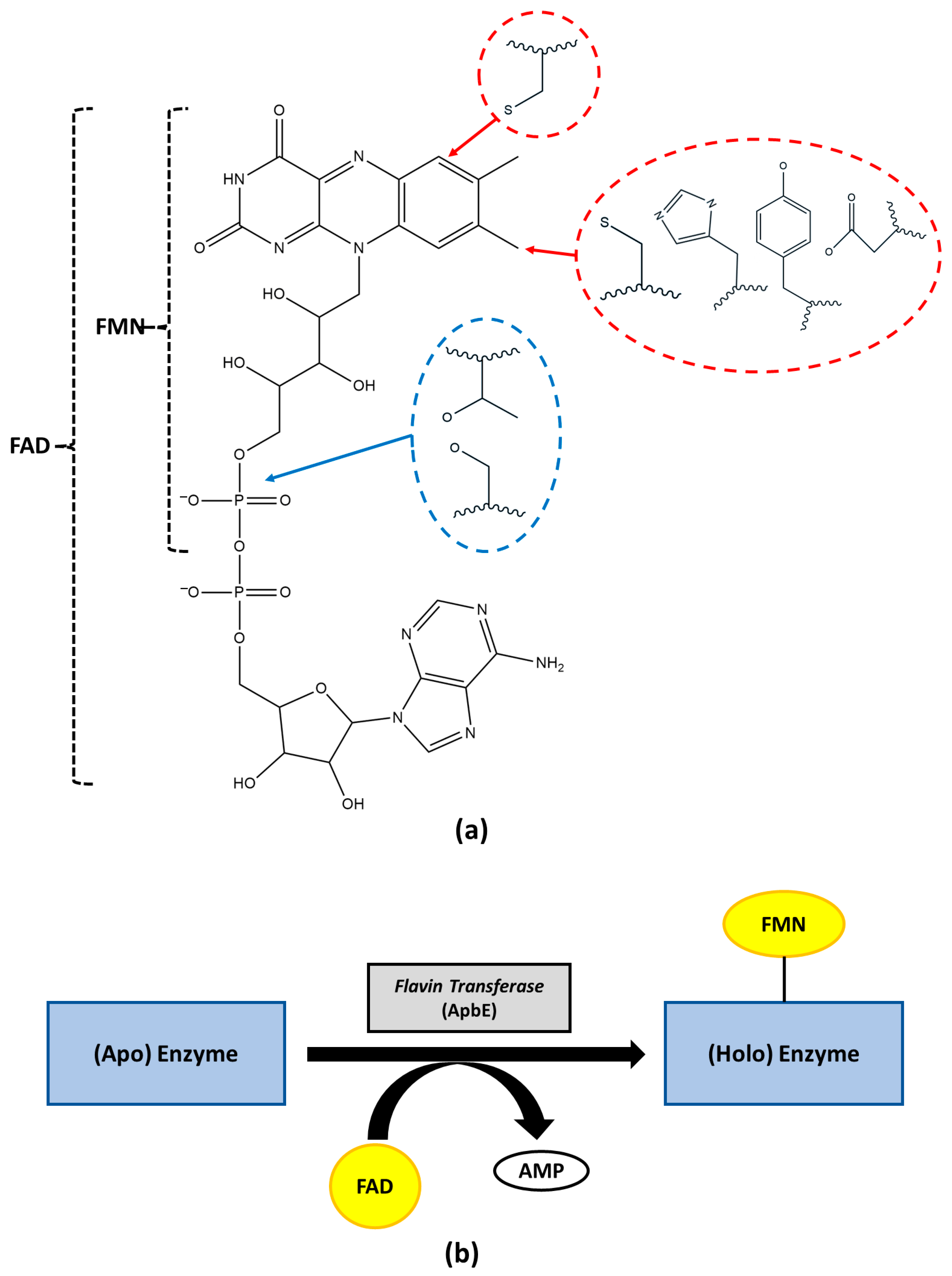

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

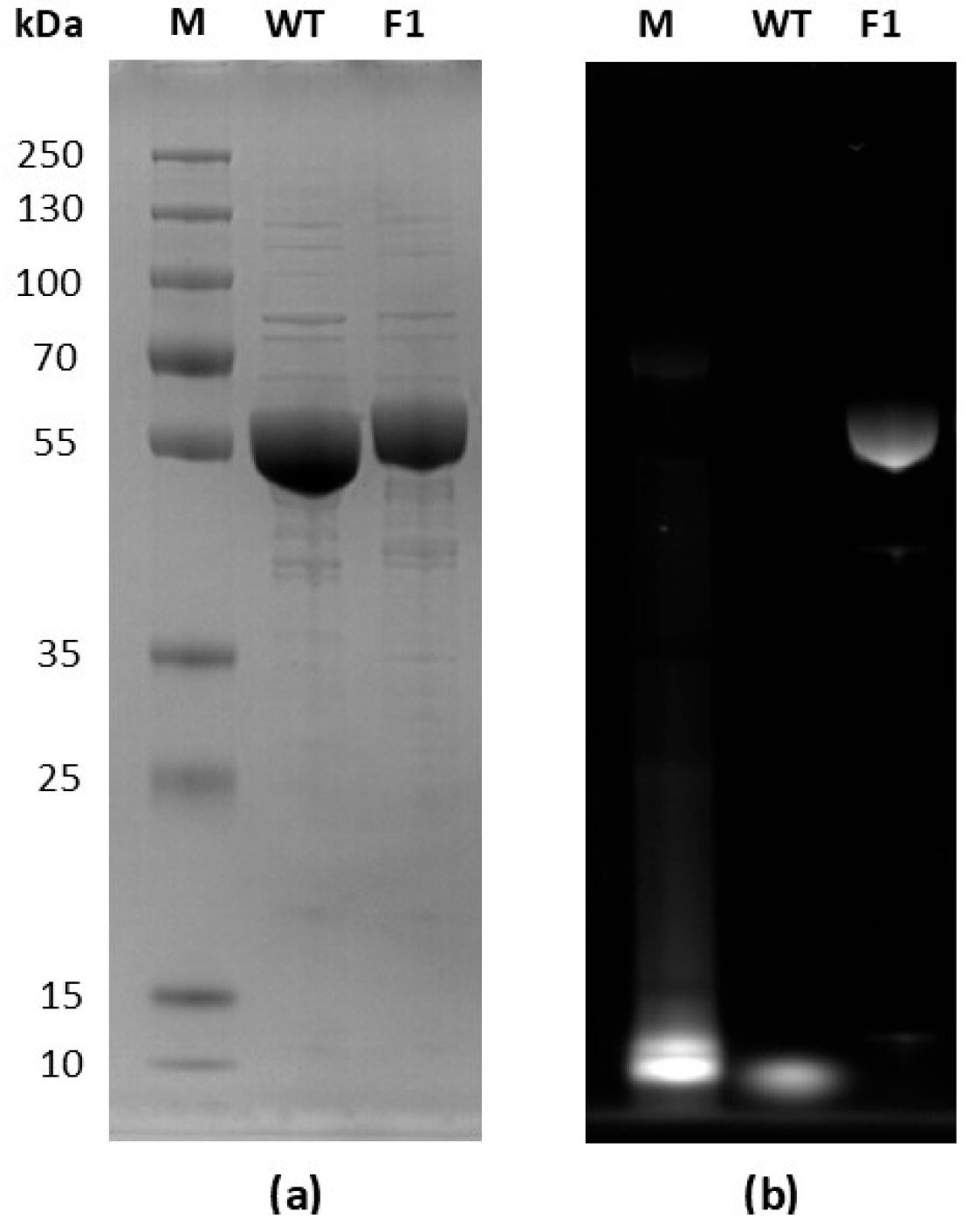

2.1. Expression and Purification of WT and F1 TsOYE

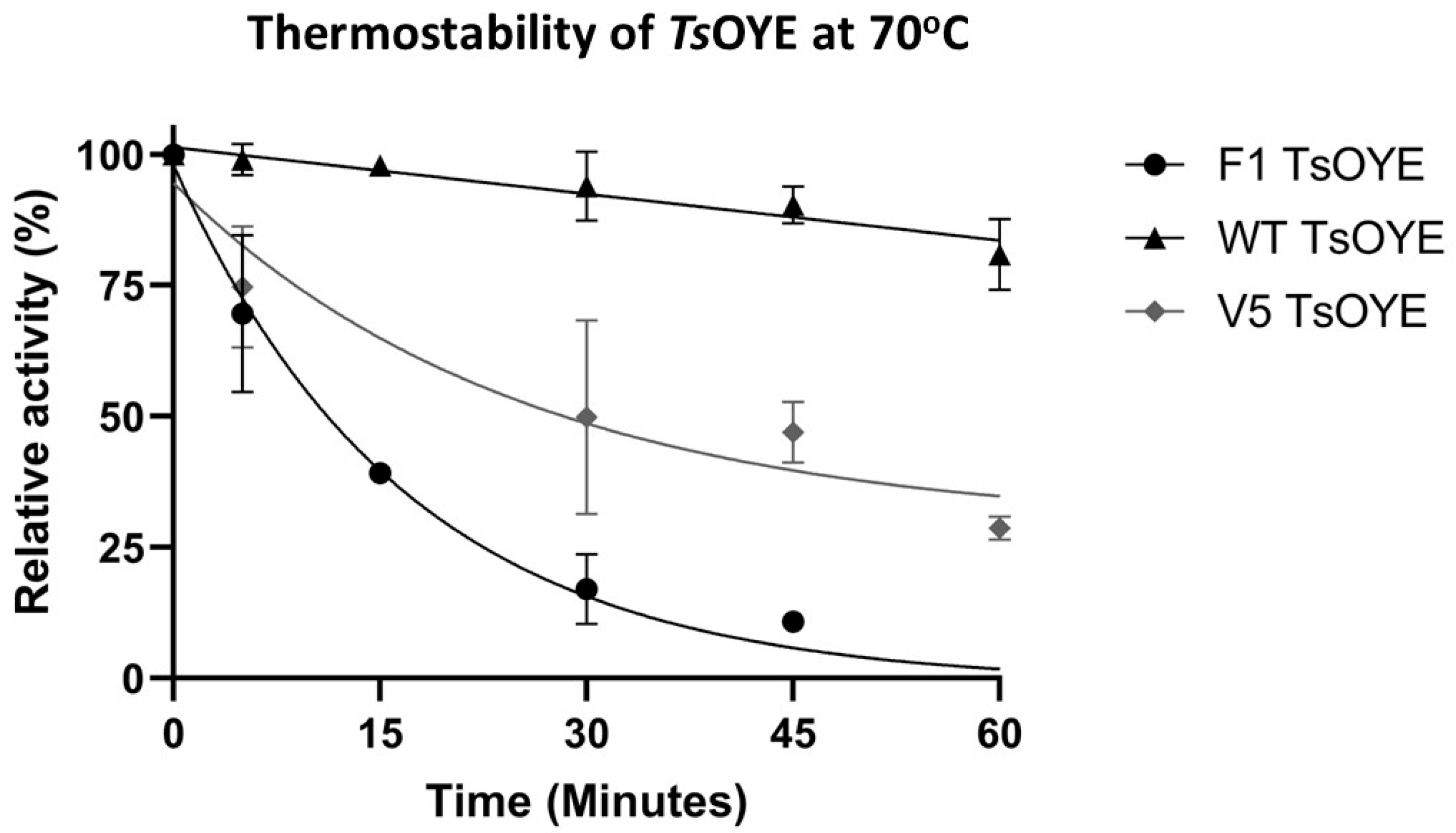

2.2. Spectroscopic and Biochemical Properties

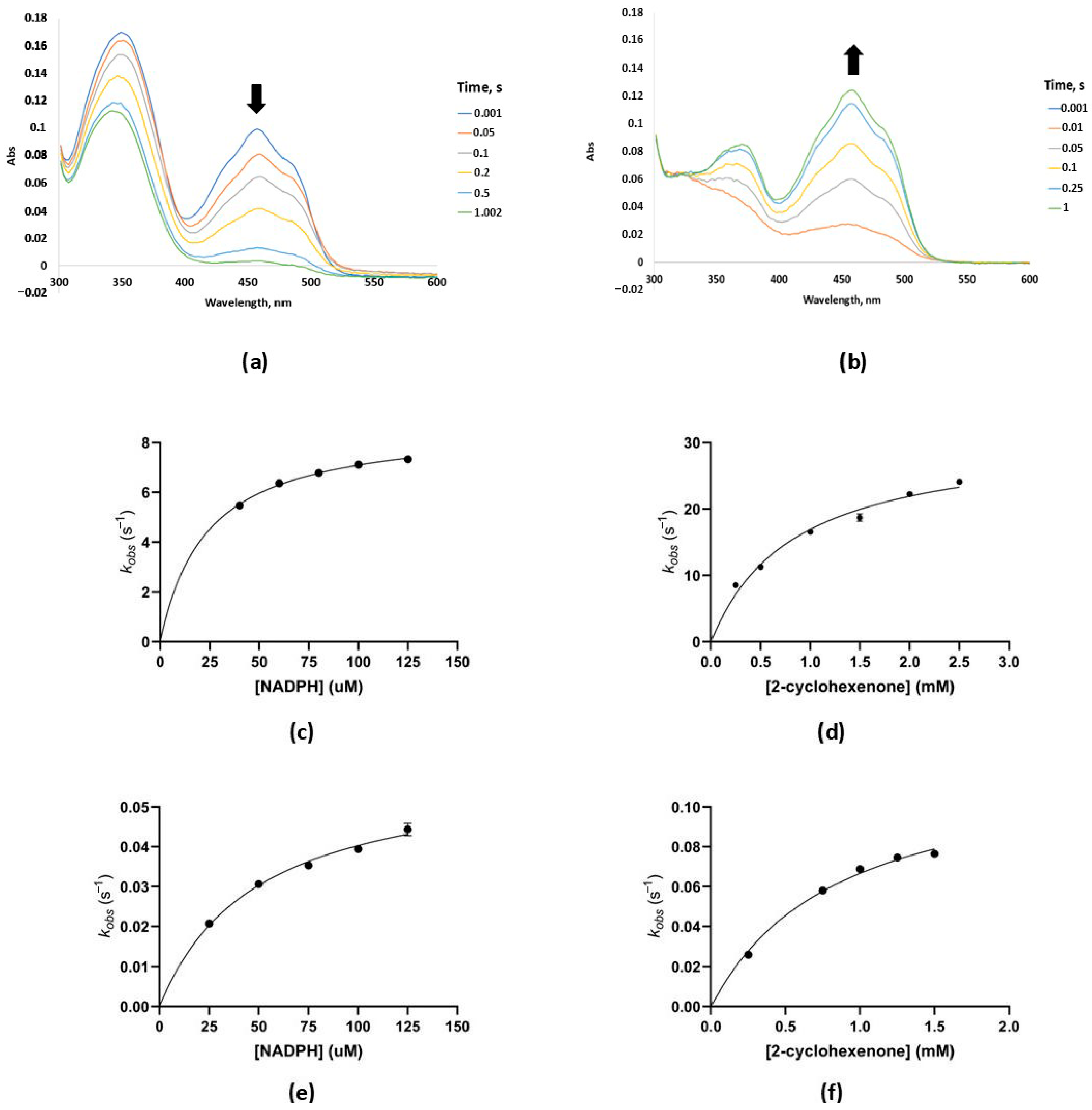

2.3. Steady State and Pre-Steady State Kinetics

2.4. Redox Potential

2.5. Replacing Residues in the Flavinylation Sequence Motif

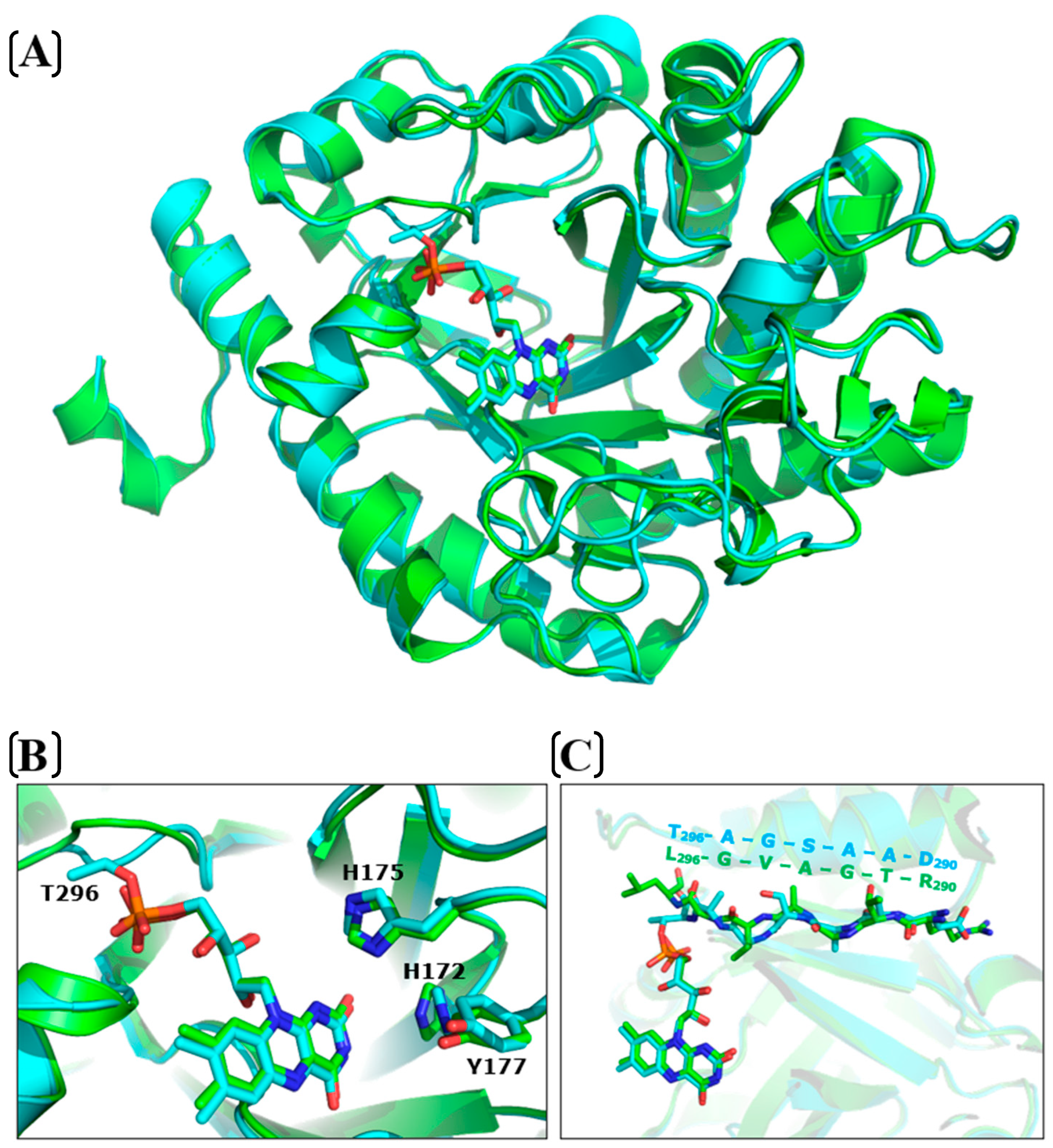

2.6. Structural Analysis

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemicals and Reagents

3.2. Cloning, Expression, and Purification

3.3. Activity Assay and Substrate Screening

3.4. pH Optimum for Activity

3.5. Thermostability Assay

3.6. Steady State Kinetic Analyses

3.7. Pre-Steady State Kinetic Analyses

3.8. Redox Potential Determination

3.9. Preparation of Mutants and Structural Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ApbE | Alternative pyrimidine biosynthesis protein |

| BtNR | Bacillus tequilensis nitroreductase |

| FAD | Flavin adenine dinucleotide |

| FMN | Flavin mononucleotide |

| miniSOG | Mini Singlet Oxygen Generator engineered |

| NADPH | Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate |

| OYE | Old Yellow Enzyme |

| PDA | Photodiode array |

| PMT | Photomultiplier tube |

| PpSB-1-LOV | Pseudomonas putida Light Oxygen Voltage protein |

| SDS-PAGE | Sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis |

| TsOYE | Thermus scotoductus SA-01 Old Yellow Enzyme |

| WT | Wild Type |

References

- Swiderska, M.A.; Stewart, J.D. Stereoselective enone reductions by Saccharomyces carlsbergensis old yellow enzyme. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2006, 42, 52–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M.; Stueckler, C.; Hauer, B.; Stuermer, R.; Friedrich, T.; Breuer, M.; Kroutil, W.; Faber, K. Asymmetric bioreduction of activated C=C bonds using Zymomonas mobilis NCR enoate reductase and old yellow enzymes OYE 1-3 from yeasts. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 2008, 1511–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, C.K.; Tasnádi, G.; Clay, D.; Hall, M.; Faber, K. Asymmetric bioreduction of activated alkenes to industrially relevant optically active compounds. J. Biotechnol. 2012, 162, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nygaard, A.P.; Theorell, H. The linkages between flavine mononucleotide (FMN) and the protein of the old yellow enzyme studied by fluores-cence measurements. Ark. Kemi 1954, 7, 205–209. [Google Scholar]

- Nygaard, A.P.; Theorell, H.; Bonnichsen, R.; Caglieris, A. On the Chemical Nature of the FMN-binding Groups in the Old Yellow Enzyme. Acta Chem. Scand. 1955, 9, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramovitz, A.S.; Massey, V. Interaction of phenols with old yellow enzyme. Physical evidence for charge-transfer complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 1976, 251, 5327–5336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, V.; Schopfer, L.M. Reactivity of old yellow enzyme with alpha-NADPH and other pyridine nucleotide derivatives. J. Biol. Chem. 1986, 261, 1215–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warburg, O.; Christian, W. Ein zweites sauerstoffübertragendes Ferment und sein Absorptionsspektrum. Naturwissenschaften 1932, 20, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karplus, P.A.; Fox, K.M.; Massey, V. Structure-function relations for old yellow enzyme. FASEB J. 1995, 9, 1518–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, K.M.; Karplus, P.A. Old yellow enzyme at 2 Å resolution: Overall structure, ligand binding, and comparison with related flavoproteins. Structure 1994, 2, 1089–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, K.; Thiele, D.J.; Davio, M.; Lockridge, O.; Massey, V. The cloning and expression of a gene encoding old yellow enzyme from Saccharomyces carlsbergensis. J. Biol. Chem. 1991, 266, 20720–20724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niino, Y.S.; Chakraborty, S.; Brown, B.J.; Massey, V. A new old yellow enzyme of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 1983–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohli, R.M.; Massey, V. The Oxidative Half-reaction of Old Yellow Enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 32763–32770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, B.J.; Deng, Z.; Karplus, P.A.; Massey, V. On the active site of old yellow enzyme: Role of histidine 191 and asparagine 194. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 32753–32762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toogood, H.S.; Gardiner, J.M.; Scrutton, N.S. Biocatalytic Reductions and Chemical Versatility of the Old Yellow Enzyme Family of Flavoprotein Oxidoreductases. ChemCatChem 2010, 2, 892–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhmer, S.; Marx, C.; Gómez-Baraibar, Á.; Nowaczyk, M.M.; Tischler, D.; Hemschemeier, A.; Happe, T. Evolutionary diverse Chlamydomonas reinhardtii Old Yellow Enzymes reveal distinctive catalytic properties and potential for whole-cell biotransformations. Algal Res. 2020, 50, 101970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opperman, D.J.; Piater, L.A.; Van Heerden, E. A novel chromate reductase from Thermus scotoductus SA-01 related to old yellow enzyme. J. Bacteriol. 2008, 190, 3076–3082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opperman, D.J.; Sewell, B.T.; Litthauer, D.; Isupov, M.N.; Littlechild, J.A.; van Heerden, E. Crystal structure of a thermostable Old Yellow Enzyme from Thermus scotoductus SA-01. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010, 393, 426–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Qi, S.; Wang, Z.; Hu, L.; Liu, J.; Huang, G.; Peng, Y.; Fang, Z.; Wu, Q.; Hu, Y.; et al. Ene-Reductase-Catalyzed Aromatization of Simple Cyclohexanones to Phenols. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202408359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hengst, J.M.A.; Wolder, A.E.; Sánchez, M.; Huijbers, M.M.E.; Opperman, D.J.; Gilles, P.; Martin, J.; Hilberath, T.; Hollmann, F.; Paul, C.E. Ene-Reductase-Catalyzed Oxidation Reactions. ChemCatChem 2024, 17, e202401447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuts, D.P.H.M.; Scrutton, N.S.; McIntire, W.S.; Fraaije, M.W. What’s in a covalent bond?: On the role and formation of covalently bound flavin cofactors. FEBS J. 2009, 276, 3405–3427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakayama, Y.; Yasui, M.; Sugahara, K.; Hayashi, M.; Unemoto, T. Covalently bound flavin in the NqrB and NqrC subunits of Na+-translocating NADH-quinone reductase from Vibrio alginolyticus. FEBS Lett. 2000, 474, 165–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, M.; Nakayama, Y.; Yasui, M.; Maeda, M.; Furuishi, K.; Unemoto, T. FMN is covalently attached to a threonine residue in the NqrB and NqrC subunits of Na+-translocating NADH-quinone reductase from Vibrio alginolyticus. FEBS Lett. 2001, 488, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertsova, Y.V.; Fadeeva, M.S.; Kostyrko, V.A.; Serebryakova, M.V.; Baykov, A.A.; Bogachev, A.V. Alternative pyrimidine biosynthesis protein ApbE is a flavin transferase catalyzing covalent attachment of FMN to a threonine residue in bacterial flavoproteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 14276–14286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y.; Rozeboom, H.J.; Loonstra, M.R.; Wijma, H.J.; Fraaije, M.W. Characterization of two bacterial multi-flavinylated proteins harboring multiple covalent flavin cofactors. BBA Adv. 2023, 4, 100097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y.; Kaya, S.G.; Russo, S.; Rozeboom, H.J.; Wijma, H.J.; Fraaije, M.W. Fixing Flavins: Hijacking a Flavin Transferase for Equipping Flavoproteins with a Covalent Flavin Cofactor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 27140–27148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaev, A.; Yudenko, A.; Smolentseva, A.; Bogorodskiy, A.; Tsybrov, F.; Borshchevskiy, V.; Bukhalovich, S.; Nazarenko, V.V.; Kuznetsova, E.; Semenov, O.; et al. Fine spectral tuning of a flavin-binding fluorescent protein for multicolor imaging. J. Biol. Chem. 2023, 299, 102977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, M.P.; Ouedraogo, D.; Orozco-Gonzalez, Y.; Gadda, G.; Gozem, S. Alternative Strategy for Spectral Tuning of Flavin-Binding Fluorescent Proteins. J. Phys. Chem. B 2023, 127, 1301–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, D.E.; Newton-Vinson, P. The Covalent FAD of Monoamine Oxidase: Structural and Functional Role and Mechanism of the Flavinylation Reaction. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2001, 3, 789–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, R.C.; Massey, V. Potentiometric studies of native and flavin-substituted old yellow enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 1985, 260, 13639–13647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schittmayer, M.; Glieder, A.; Uhl, M.K.; Winkler, A.; Zach, S.; Schrittwieser, J.H.; Kroutil, W.; MacHeroux, P.; Gruber, K.; Kambourakis, S.; et al. Old yellow enzyme-catalyzed dehydrogenation of saturated ketones. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2011, 353, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, D.W.; Iamurri, S.; Keshavarz-Joud, P.; Blue, T.; Copp, J.; Lutz, S. The Hidden Biocatalytic Potential of the Old Yellow Enzyme Family. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericsson, U.B.; Hallberg, B.M.; DeTitta, G.T.; Dekker, N.; Nordlund, P. Thermofluor-based high-throughput stability optimization of proteins for structural studies. Anal. Biochem. 2006, 357, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niesen, F.H.; Berglund, H.; Vedadi, M. The use of differential scanning fluorimetry to detect ligand interactions that promote protein stability. Nat. Protoc. 2007, 2, 2212–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abramson, J.; Adler, J.; Dunger, J.; Evans, R.; Green, T.; Pritzel, A.; Ronneberger, O.; Willmore, L.; Ballard, A.J.; Bambrick, J.; et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 2024, 630, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger, E.; Joo, K.; Lee, J.; Lee, J.; Raman, S.; Thompson, J.; Tyka, M.; Baker, D.; Karplus, K. Improving physical realism, stereochemistry, and side-chain accuracy in homology modeling: Four approaches that performed well in CASP8. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinform. 2009, 77, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Substrates | kobs (s−1) | |

|---|---|---|

| WT TsOYE | F1 TsOYE | |

2-cyclohexenone  | 3.47 ± 0.02 | 0.18 ± 0.02 |

2-methyl-2-cyclohexenone  | 1.36 ± 0.03 | 0.11 ± 0.01 |

3-methyl-2-cyclohexenone  | 0.23 ± 0.02 | 0.10 ± 0.002 |

ketoisophorone  | 0.53 ± 0.02 | 0.11 ± 0.01 |

isophorone  | 0.25 ± 0.01 | 0.08 ± 0.001 |

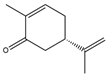

(S)-carvone  | 1.91 ± 0.03 | 0.10 ± 0.001 |

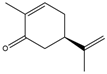

(R)-carvone  | 2.76 ± 0.06 | 0.15 ± 0.001 |

| TsOYE | kcat (s−1) | KM (µM) | kcat/KM (s−1 mM−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 4.31 ± 0.07 | 154 ± 13 | 27.9 ± 0.1 |

| F1 | 0.07 ± 0.002 | 9.7 ± 1.8 | 7.4 ± 0.2 |

| TsOYE | Reductive-Half Reaction | Oxidative-Half Reaction | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| kred (s−1) | KD (µM) | kox (s−1) | KD (µM) | |

| WT | 8.75 ± 0.11 | 23.4 ± 1.2 | 31.0 ± 1.8 | 833 ± 130 |

| F1 | 0.060 ± 0.003 | 49.1 ± 5.7 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 871 ± 91 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Fathurahman, A.T.; Fraaije, M.W. Flavin Fixing in Old Yellow Enzyme from Thermus scotoductus: A Comparative Study of the Wild-Type Enzyme and Covalently Flavinylated Mutants. Catalysts 2026, 16, 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010042

Fathurahman AT, Fraaije MW. Flavin Fixing in Old Yellow Enzyme from Thermus scotoductus: A Comparative Study of the Wild-Type Enzyme and Covalently Flavinylated Mutants. Catalysts. 2026; 16(1):42. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010042

Chicago/Turabian StyleFathurahman, Alfi T., and Marco W. Fraaije. 2026. "Flavin Fixing in Old Yellow Enzyme from Thermus scotoductus: A Comparative Study of the Wild-Type Enzyme and Covalently Flavinylated Mutants" Catalysts 16, no. 1: 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010042

APA StyleFathurahman, A. T., & Fraaije, M. W. (2026). Flavin Fixing in Old Yellow Enzyme from Thermus scotoductus: A Comparative Study of the Wild-Type Enzyme and Covalently Flavinylated Mutants. Catalysts, 16(1), 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal16010042